Joining and sealing documents from the 17th to 19th centuries.

By Rachel Bartgis

Conservator Technician

U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

A Seal – or Not?

A small, raised dot of red on a document—is it sealing wax? Not always. In some cases what looks like sealing wax is actually a wafer seal, sealing wax’s cheaper cousin. Wafers are thin, flat, baked adhesive discs made from starch, binders, and pigment that were used for joining and sealing documents during the 17th through 19th centuries in Great Britain and other European countries and their colonies. Although they were usually red in color, they were produced in a variety of colors and sizes according to their intended purpose.

Wafers were applied by soaking the wafer in water, transferring it to the document, and pressing the two surfaces together and allowing them to dry. As anyone who has ever had to scrape dried dough off something can attest, flour and water make a strong adhesive.

Wafers were made by combining flour, gum arabic, water, and a pigment; cooking the thin cakes; and stamping out the individual seals. Sealing wax required more expensive materials such as shellac (a resin secreted by an insect found in India and Thailand) and beeswax, and an expensive metal mold to make the long batons of wax. Hence the difference in price: in Philadelphia in 1775, several hundred “common wafers” cost one shilling, less than half the cost of the equivalent of sealing wax.

Wafers had an enormous number of uses and served roles filled in modern times by paper clips, Scotch tape, and even blue sticky tack.

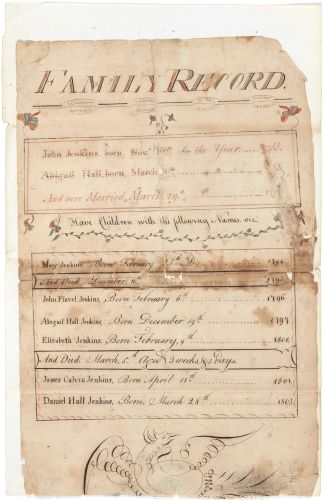

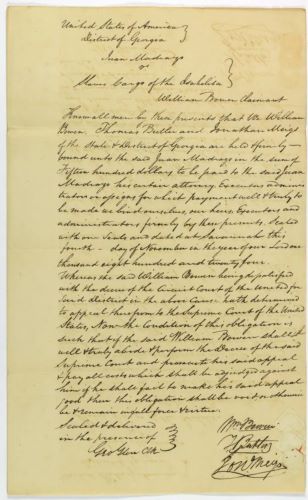

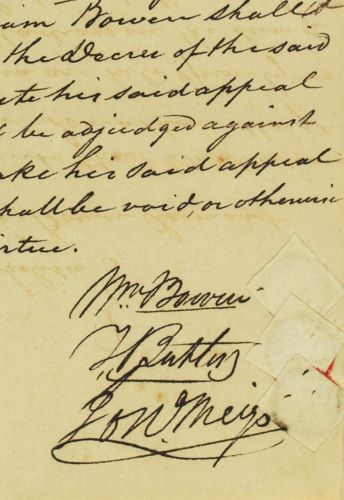

The invention of seals and stamps made from embossed paper allowed for a more affordable option than a traditional official seal made by pressing a metal seal into melted wax. An example of this use can be seen in the papers of a court case from 1822, where the signatures are accompanied by embossed paper seals attached by wafers:

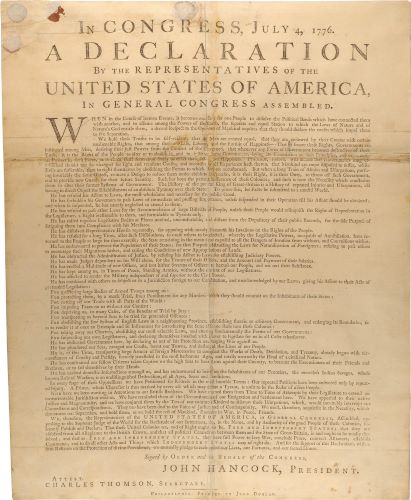

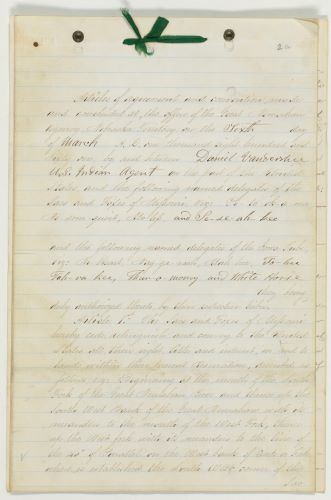

A prominent example of wafer seals can be found on the Dunlap Broadside, the copy of the Declaration of Independence printed on the night of July 4, 1776. The wafer seals on the upper left corner of the document are a legacy of how the Dunlap Broadside was stored for the first part of its life. After the Continental Congress orally ratified the Declaration of Independence, the clerk responsible for keeping the minutes of the Continental Congress left blank space on a page of the minutes book known as a Rough Journal. Once the Declaration was printed and delivered to the clerk, the broadside was attached to the blank space using several wafer seals and stored folded within the volume.

The invention of pre-gummed coated papers meant that embossed official seals came with their own adhesive instead of needing a separate wafer for attachment, and the invention of the gummed envelope in the 1850s meant that wafers were no longer needed to seal letters

However, wafers were still used in the Civil War, with Confederate Army requisition forms even having a place for clerks to request wafers alongside paper, envelopes, sealing wax, and tape.

Ribbons and Bows

Even in the decades when the oldest records in the National Archives were being created, government clerks and officials had access to many different ways to hold documents together, including ribbon, pins, thread, sealing wax, and wafers.

Government clerks usually kept a small, sharp knife at hand for trimming their quill pens. With a store of silk ribbon or cotton tape nearby, they could easily attach documents to each other by cutting two slits in the paper and feeding a ribbon through them. This would let them quickly bind several sheets together into a pamphlet, or sew sheets together to create a longer piece of paper if that format was desired. Some of the most visually striking examples of this survive in treaties, where silk ribbons that have barely faded with age survive.

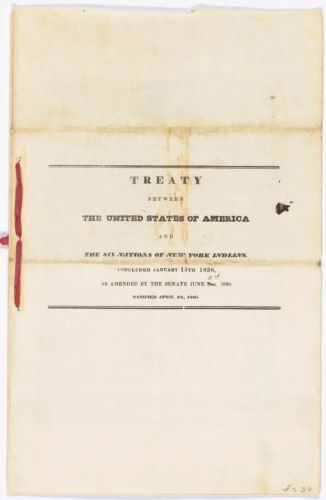

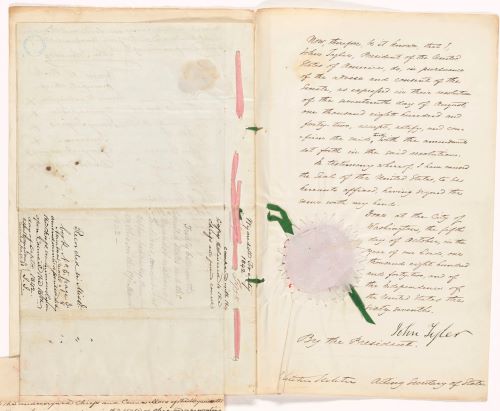

Before the invention of stapled bindings, the “pamphlet stitch” was common to sew short texts together—though most used plain thread, not silk ribbon. After this treaty was printed, the sheets were folded into pages, and the pages were sewn together to form a pamphlet:

This treaty shows a blue silk ribbon used to attach a smaller piece of paper to the treaty:

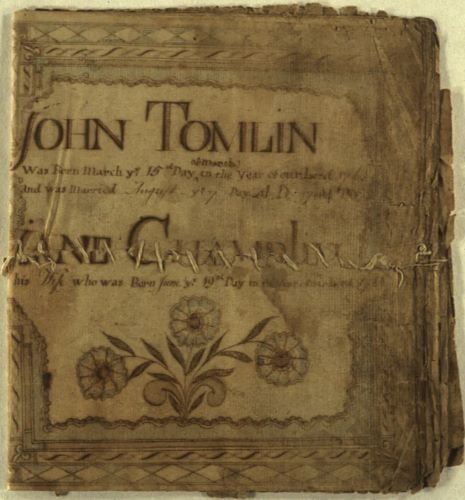

While it can be hard to find the examples, some documents were attached or repaired by even simpler methods: threading a needle with a piece of linen thread, and sewing a torn document back together, or attaching papers with a loop of thread, as shown in this heavily-worn fraktur:

Before Passwords—Ribbons and Seals for Document Security

In the centuries before the self-inking notary public’s stamp, U.S. government clerks and secretaries used brightly-colored silk ribbons, wax seals, and embossed paper seals attached with wafers to verify the security of important documents.

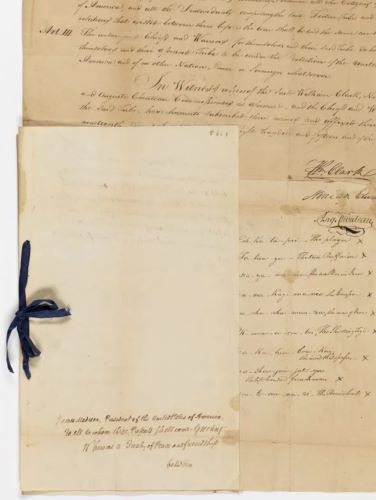

Ribbons were used to attach important documents together, but they also served a security function as proof against tampering. The clerk would cut slits in the paper or parchment, weave the ribbon through it, and then the signatories or government official would attach their wax seal, attach an embossed paper seal to the paper with sealing wax or a wafer, or emboss the paper itself.

Sealing wax was used for a number of reasons: to verify a document hadn’t been opened, to verify someone’s identity, and for decorative purposes. As the name suggests, sealing wax is primarily composed of beeswax. To help the wax harden, manufacturers in the 16th century began adding shellac, a resin secreted by an insect found in India and Thailand. To this mixture was added rosin, chalk, and a pigment, often vermillion (made from mercury) or lead. The mixture was heated and poured into a metal mold, where it hardened into batons similar to the plastic sticks sold today.

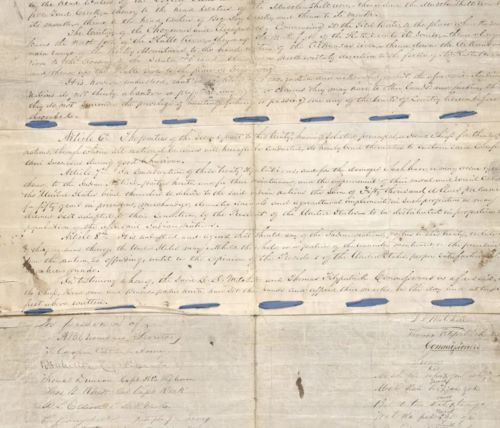

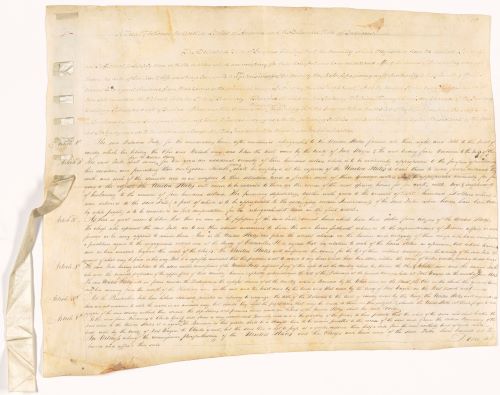

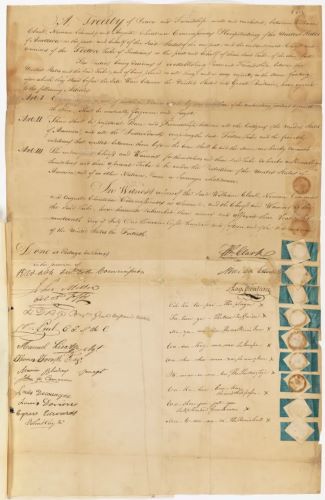

Seals were hard to duplicate, and trying to remove the adhered sandwich of ribbon, adhesive, and paper from the document for nefarious purposes would damage it, creating a certain amount of proof against tampering. This 1804 Treaty with the Delawares used both ribbon and wax seals to keep it secure.

Parchment has a slicker, tougher surface than paper, and it’s difficult to keep sealing wax adhered to its surface or emboss it clearly. In the case of Delaware Treaty, which was on parchment, the broad ribbon woven through the paper help keep the seals affixed to the document.

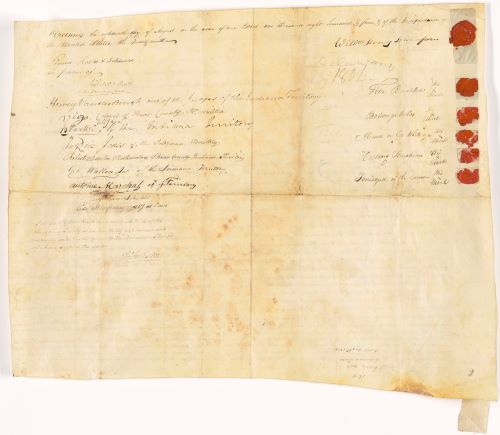

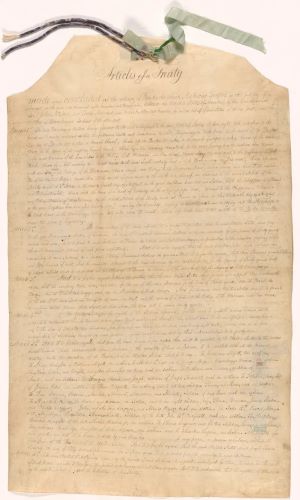

This 1842 Treaty with the Wyandots, which is on paper, used two different types of ribbon. The pink is a linen tape that is holding a sheet of the document together, while the green is a silk ribbon under an embossed paper seal, attached to the paper with a big red sealing wafer.

The seals on the 1815 Treaty with the Tetons, which is on paper as well, show the sandwich created by the ribbon, wafer, and paper next to the X made by each Native American signatory.

Treaties made between the U.S. Government and Indian tribes also show a blend of both cultural traditions by including strings of wampum with the ribbons attached to the documents.

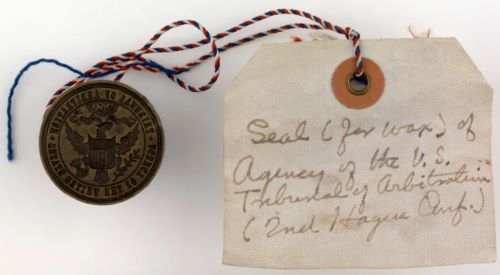

While 18th- and early 19th-century treaties made heavy use of traditional materials like parchment and large wax seals, these materials began to be phased out in the mid 19th century for reasons of convenience and cost. This wax seal used at the Second Hague Conference in 1907 is a later surviving example.

Sealing wax was also used for closing letters. Before the early 19th century, postal rates were calculated in part by the number of sheets of paper a letter contained, and paper itself was costly, making envelopes or cover sheets an expensive commitment for a sender. Writers folded the letter up and sealed it, either with wax or a wafer seal.

After postal rates changed and machine-made paper was invented, the envelope became widespread in the 1840s. Gummed envelopes were invented by the 1850s. People could close the envelope with adhesive, glue, or a wafer, but just as today, some people continued to use wax, particularly those in official positions.

This 1860 envelope from the Episcopal Bishop of California to Rose Greenhow (who became a Confederate spy during the American Civil War) shows a beautiful wax seal securing the letter.

By the mid-to-late 19th century, with the proliferation of pre-gummed envelopes, wax seals fell out of common use. Today, seals and ribbons are not often used for document security, but they are used for decorative purposes for special occasions such as wedding invitations.

From Red Tape to Grommets

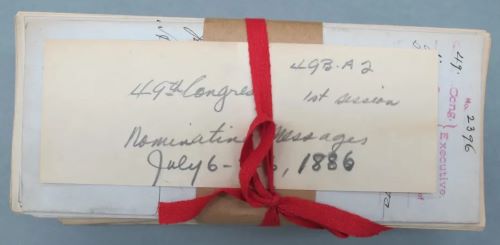

Early 19th-century government clerks relied on ribbon, pins, thread, sealing wax, and wafers to hold their papers together, but over the course of the century, these materials were joined by a host of other fasteners, including staples, grommets, and red tape.

While red tape is used in the metaphorical sense these days, it used to refer to literal red tape: a narrow ribbon made from cotton or linen, dyed red. This was used by government clerks for all sorts of purposes, from tying bundles of related papers together, to sealing official documents, to tying shut envelopes.

As laid out in the “Instructions for Keeping the Records and Transacting the Clerical Business of the War Department” of 1876, “Whenever a case requiring action extends through several papers, the papers should, with the air of an elastic band or office tape [red tape], be always so arranged by the clerks into whose hands they come for action as to present to view the briefs of writers and contents of the principal communications in the order of their dates.”

The amount of tape used by the Union Army was by no means small in quantity. According to the “Expenditures from the Contingent Fund of the War Department” report submitted to the 28th Congress in 1865, in the fiscal year ending June 30, 1864, the offices of the headquarters of the War Department alone bought a total of 154 miles of red tape. As one Civil War historian wryly noted, this was enough to stretch from the War Department’s Winder Building in Washington, DC, to the Confederate fortifications in Petersburg, Virginia.

Conditions in the field were a little dearer. According to Army regulations during the war, each company was entitled to a quarterly issue of the following stationery supplies: five quires (120 sheets) of writing paper, ½ quire of envelope paper, 20 quills, ½ ounce of wafers, three ounces of sealing wax, one paper of ink powder, and one piece [3¾ yards] of “office tape.”

At the same time, grommets (small metal rings) were becoming a particularly popular as a permanent method of securing papers together, and they appear in many NARA documents.

The downside of a grommet was that it required purchasing a machine to install them, and machines could have their own proprietary designs.

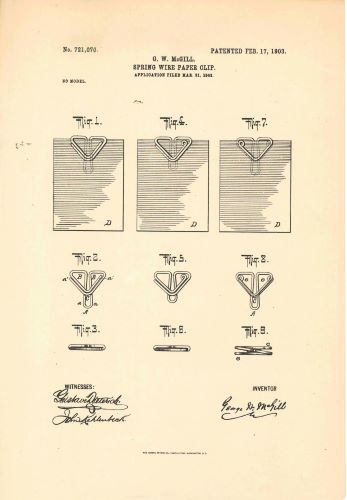

George W. McGill, who invented the brass fastener in 1866, also received an early patent in 1867 for a machine to insert those fasteners into paper, one of the first iterations of the stapler. Various patents for refinements filed over the course of the 1870s included staple machines that inserted and crimped a staple in a single step, the magazine of preformed wire staples, and the spring-loaded stapler. The McGill Single-Stroke Staple Press of 1878 was one of the first commercially successful staplers, although the word “stapler” didn’t come into published use until the early 20th century, and small, sleek desktop models took a little more time to evolve.

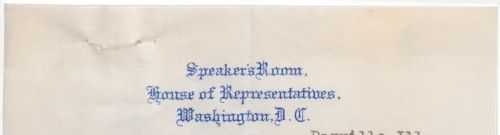

While the fasteners and other office supplies mentioned in this series feel ubiquitous in the 21st century, there was a time when conserving their use was a part of the U.S. war effort in World War II. The diversion of metal and factories for the war effort limited the availability of staplers and paper clips, just as long ago the British blockade limited the availability of paper, sealing wax, silk ribbon, and other imported stationery goods in cities held by the Continental Army during the American Revolution.

From Pins to Paper Clips

A century after the silk ribbon and sealing wax of the Continental Congress, clerks of the antebellum years had access to a host of new technologies and fasteners, including glue, rubber bands, paper clips, eyelets, staples, grommets, and red tape. But for temporarily holding together papers, one of the simplest and earliest technologies was the pin.

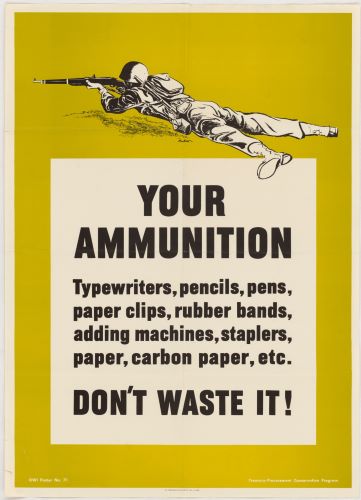

A ubiquitous little item used for fastening clothing from the 17th to 19th centuries as well as for assisting with sewing, pins also made handy fasteners for sticking one piece of paper to another. Later in the 19th century, specialized pins for clerks were sold as “bank pins,” with a later variant being a piece of wire bent into a “T” shape, instead of a straight pin. While few remain on digitized documents, keep a sharp eye out for two holes about ½” inch apart, generally in a corner of the paper. To see some pins in situ, check out this post from the Folger Shakespeare Library’s blog, The Collation.

The obvious disadvantage of the pin is that it puts a physical hole in a paper, which can weaken the paper and even tear it, especially if papers need to be pinned and re-pinned again over the years. It’s also difficult to stick a pin through more than a few pieces of paper—a problem ripe for a solution.

Enter the paper clip.

The roughly trombone-shaped paper clip that we’re all used to in the 21st century is in fact the product of a good deal of experimentation with removeable, non-perforating fasteners in the last quarter of the 19th century. One of many challenges to overcome was finding the correct tension of wire that will return to its original shape after being bent—too soft a metal and it won’t hold the papers, but too hard and it won’t be able to be successfully bent. Steel wire proved the solution.

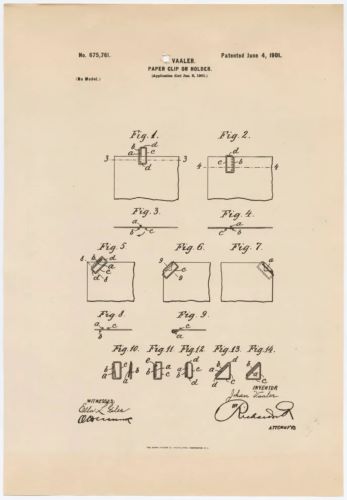

Then there was the shape. According to The Evolution of Useful Things, some of the first patents issued in the United States for a bent wire paper clip were filed by Matthew Schooley in 1898 and Cornelius Brosnan in 1900, while one of the earliest patents in NARA’s collection is Johan Vaaler’s 1901 patent, first filed in Germany in 1899.

The familiar, trombone-esque spiral that ultimately became ubiquitous was the “Gem,” introduced in Great Britain around 1907. While other versions stayed around for many decades, the Gem’s lack of exposed points that could tear paper and simple design helped ensure its survival into the 21st century, and its presence in NARA research rooms, to this day.

Originally published by Pieces of History, United States National Archives and Records Administration, 10.05.2021, to the public domain.