Exploring the origin, development and social location of the Orphic-Bacchic mysteries.

By Dr. Jan N. Bremmer

Visiting Research Scholar

Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

New York University

Introduction

While the Eleusinian Mysteries and those of Samothrace were tied to specific sanctuaries, there was also a much more mysterious type of Mysteries, not unlike those of the Korybantes, that was associated with Orpheus, one of the most popular figures of Greek mythology.1 Who does not know his failed attempt to recover Eurydice, whom some modern female poets consider even more important than Orpheus himself?2 The early Greeks thought of Orpheus primarily as a musician and a poet, but that was not the only side of him that attracted people in antiquity. There was a religious movement associated with him, which we nowadays call Orphism. In the last four decades there have been astonishing new discoveries relating to this movement. We have had the publication of a commentary on what may be the oldest Orphic theogony (the famous Derveni Papyrus),3 the discovery of Orphic bone tablets in Olbia,4 the appearance on the market of new Apulian vases with representations of Orpheus and the afterlife,5 and a steady stream of Orphic ‘Gold Leaves’(small inscribed gold lamellae found in graves) from all over the Greek world.6 These striking new discoveries enable usto study Orphism in a more detailed way than was possible in studies produced before the 1970s,7 which are now all, to a greater or lesser extent, out of date. The new finds have also enriched our understanding of a particular type of Mysteries, which are increasingly being called the Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries. This article will explore the origin, development and social location of these Mysteries (§3),but will first take a brief look at Orpheus himself (§1) and at the Orphic movement(§2). I will conclude with some considerations about the historical development of Orphism and its Mysteries (§4).

Orpheus

So let us start with Orpheus himself: I shall emphasise four of his aspects.8 First, in the mythological tradition he was a Thracian, even though in the historical period his place of origin, Leibethra on the foothills of Mt Olympus, was part of Macedonia. In ancient Greece, Thrace was the country of the Other. The wine god Dionysos was reputed to come from Thrace, as did the god of war, Ares, even though we know from Mycenaean texts that both these gods were already fully part of the Greek pantheon in the later second millennium BC.9 So ‘otherness’ is an important aspect of Orpheus’ mythological persona.

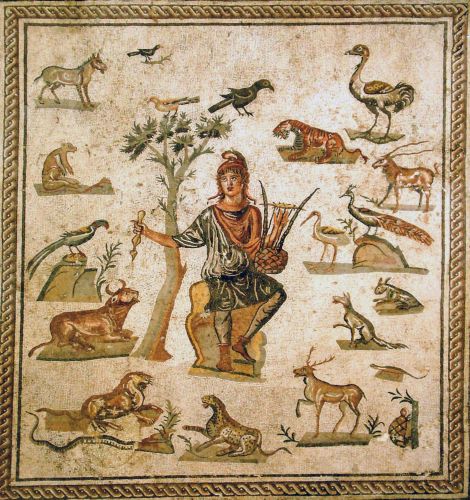

Secondly, Orpheus is the musician and singer par excellence. It is with his music that he persuaded Hades to release Eurydice, and it is with his music that he charmed animals, trees and stones, though that theme became popular only in Late Antiquity. It was for his musicianship that he was selected as the keleustês, the man who beat the rhythm to the oarsmen of the Argo, the famous ship of Jason and his Argonauts, as Euripides tells us: ‘by the mast amidships the Thracian lyre cried out a mournful Asian plaint singing commands to the rowers for their long-sweeping strokes’. Already in the mid-sixth century a metope from the Sicyonian treasury at Delphi shows him on the Argo.10 Music, song and poetry all went together for the Greeks, and they belonged to a sphere of life that was separate from the hustle and bustle of everyday existence. Poets and singers were thus people outside the normal social order. They had a special connection with the Muses–Orpheus was even the son of the Muse Calliope, which must have contributed to his authority (OF902–11)–and were often represented as blind, like Homer himself, which again singled them out from most people.11

Thirdly, the Argonautic expedition, in which Orpheus participated, has clear initiatory characteristics, abundantly demonstrated by Jason’s single sandal, the group of 50, the young age of the crew, the presence of maternal uncles, the test and the return to become king.12 Although he is still bearded on the Delphi metope, at an early stage Orpheus appears as a beardless adolescent on Attic and Apulianvases.13 The Augustan mythographer Conon (FGrH 26 F1.45) adds a most interesting detail regarding Orpheus in this respect: as king of Macedonia and Thrace, Orpheus assembled his warriors around him and performed secret rites (orgiazein) in a large building that was specially suited to initiations (teletai), but into which they could not bring weapons; this seclusion aroused the wrath of the Thracian women, who therefore stormed the building and tore Orpheus to pieces.14 Fritz Graf, perhaps our best expert on Orpheus and the Orphic movement, has persuasively connected this tradition with the Spartan and Cretan societies where the male citizens customarily dined together and initiated their youth. For our purpose we simply note that a tradition existed that connected Orpheus with secret societies. In Greek literature Orpheus is the inventor par excellence of the Mysteries.15

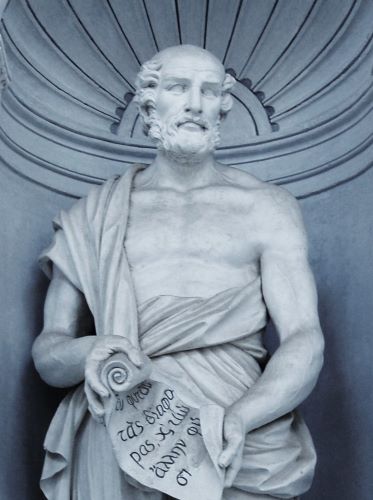

Fourth and finally, Orpheus’ song–Pindar (P. 4.176) calls him ‘father of songs’–must have been rated very highly in the classical era. The fifth-century mythographers Hellanicus, Pherecydes and Damastes all state that both Homer and Hesiod were descended from Orpheus16 and when the learned Sophist Hippias of Elis listed the most famous Greek poets he gave them in the order Orpheus, Musaeus, Hesiod and Homer, as did Aristophanes, Plato and others after him.17 Although Herodotus does not mention Orpheus by name, he clearly felt obliged to state that Homer and Hesiod lived before ‘the so-called earlier poets’(2.53: Orpheus and Musaeus).18 In other words, in the fifth century BC the prestige of Orpheus as poet was paramount, even though no archaic epics were credited to him. It was this vacuum, as we will see shortly, which would invite people to ascribe to him poems of a sometimes rather peculiar nature.

Orphism

From Orpheus I now turn to Orphism. In the summer of 1931 the aged Wilamowitz (1848–1931) worked feverishly on his last book, Der Glaube der Hellenen, knowing that he would have little time left to complete this work that was clearly close tohis heart.19 On Orpheus and Orphism he was pretty sceptical. He even called Orphismus ‘das neue Wort’,20 although in fact the German term Orphik was already current around 183021 and Orphismus was probably coined at the end of the 1850s by the German Orientalist and statesman Christian Carl Josias von Bunsen (1791–1860).22 Bunsen was not only the patron of Friedrich Max Müller(1823–1900), one of the founders of Religionswissenschaft,23 but also the man who influenced Florence Nightingale to dedicate her life to nursing;24 he had been the Prussian ambassador in London, where he will have picked up the English term ‘Orphism’, coined around 1800.25 Orphismus, then, was hardly a new word at the time of Wilamowitz’s death.

There had never been unanimity among scholars about the nature of Orphism and its adherents, and Burkert has spoken well of a ‘battlefield between rationalists and mystics since the beginning of the nineteenth century’.26 The discovery of the Derveni Papyrus and the important allusions to Orphism in Athenian literature show that Athens has a special place in the history of Orphism. So let us turn to this intellectual centre of the Greek world in the fifth century BC. Which Orphic poems were available in Athens at that time and what can we tell about the people connected to these poems?27

In recent decades it has become increasingly clear that a number of Orphic poems were circulating in Athens in the later fifth century. One of the oldest ones available may well have been an Orphic katabasis, ‘descent into the underworld’, of which Eduard Norden already reconstructed elements on the basis of Aeneid VI. The Bologna papyrus (OF717), first published in 1947, with its picture of the underworld, has only strengthened his position.28 In Greek and Latin poetry, Orpheus’ descent into the underworld is always connected to his love for Eury-dice,29 but the latter’s name does not appear in our sources before Hermesianax in the early third century BC; in fact, the name Eurydice became popular only after the rise to prominence of Macedonian queens and princesses of that name.30 As references to the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice begin with Euripides’ Alcestis (357–62 =OF980) of 438 BC, a red-figure loutrophoros of 440–430 BC31 and the decorated reliefs of, probably, the altar of the Twelve Gods in the Athenian Agora, dating from about 410 BC,32 so the poem about Orpheus’ katabasis must have certainly arrived in Athens around the middle of the fifth century BC, and its use by Aristophanes in the Frogs shows that it was well known in Athens later that century. Perhaps it had arrived even earlier: Martin West, another great expert on Orphism, may be right to think that Orpheus’ katabasis was already mentioned in Aeschylus’ Lycurgan trilogy.33 This earlier date would match the eschatological theme found in Pindar (see below), but our sources for this question are so late that it is prudent to be cautious.

Where did the poem originate? Epigenes, a writer of probably the late fifth- or early fourth-century, tells us that the Orphic Descent to Hades was actually written by Cercops the Pythagorean, which points to southern Italy, as does the mention of an Orpheus of Croton and a Descent to Hades ascribed to Orpheus from Sicilian Camarina.34 Both these authors called Orpheus will have been fictitious persons, as Martin West already noted regarding the latter,35 but Epigenes’ report is still remarkable. The poems surely acquired these author-names from the fact that they told Orpheus’ descent in the first person singular, just as Orpheus himself does at the beginning of the Orphic Argonautica: ‘I told you what I saw and perceived when I went down the dark road of Taenarum into Hades, trusting in our lyre,36 out of love for my wife’(40–42). Norden had already noted the close correspondence with the line that opens the katabasis of Orpheus in Virgil’s Georgics, Taenarias etiam fauces, alta ostia Ditis,/…ingressus (4.467–9), and persuasively concluded that both lines go back to a Descent to Hades ascribed to Orpheus.37 Pythagoras was also reputed to have made a journey to the underworld and Plato, in the Gorgias (493ac), ascribes an eschatological myth to ‘some clever mythologist, presumably from Italy or Sicily’.38 It thus seems reasonable to guess that the Orphic katabasis with the story of Eurydice originated in that area. Orphic eschatological material is used by Pindar in his Second Olympic Ode for Theron of Acragas, written in 476 BC, so the Orphic poem will probably have been composed somewhat earlier. Unfortunately no direct quotation survives from it, but it will have given a depiction of the underworld that concentrated on rewards and penalties of nameless people in the afterlife, in contrast to the older katabaseis, which focused on the heroic and famous dead.39 We cannot be sure if the poem mentioned reincarnation, but the presence of that theme in Pindar’s Second Olympian Ode and in Empedocles makes this plausible.40

A second old Orphic work available in Athens was a Theogony. As with the Orphic katabasis, there was probably more than one work circulating under thisname,41 as Orphic literature was very prolific. The oldest example to give us some idea of the Orphic theogony(ies?) is the Derveni Papyrus, which contains a number of quotations from Orpheus’ poem together with an allegorising commentary. The surviving quotations are incomplete, not only due to the burning of the papyrus, but also because the author of the commentary may have left out whole passages in his discussion of the poem; any reconstruction of the original content of the Theogony therefore needs to proceed carefully.42 Although its date and place of composition are unknown, the Theogony is close to Parmenides, which once again seems to point to southern Italy in the early fifth century.43

The Orphic Theogony was clearly written in opposition to Hesiod’s Theogony and stressed the pre-eminent position of Zeus in a kind of magnificat which glorified him as ‘Zeus is the head, Zeus is the middle and from Zeus everything is fashioned’(XVII.12);44 Zeus even ‘devised’ Oceanus (XXIII.4; XXV.14?) in a kind of, so to speak, intelligent design. The papyrus breaks off at the moment when Zeus was raping his mother Rhea-Demeter. In later Orphism this rape is followed by Zeus’ incestuous union in snake form with their daughter Persephone, which produced Dionysos. After the Titans had slaughtered and eaten him, Zeus killed them with his thunderbolt, but from their soot emerged mankind, which was therefore partially divine in origin.45

The latter part, from the rapes onwards, is attested only in later Orphic literature, but details of this story, although not to the anthropogony, are found already in Callimachus and Euphorion, which takes it back to the early Hellenistic period.46 Here we may add another, neglected allusion that implies an early date for the story. In Athens Persephone’s name was written as P(h)ersephassain tragedy and as Pherephatta and its variations in inscriptions, comedy and other non-tragic literature.47 Tatian and Clement of Alexandria use these old Attic forms Phersephassa and Pherephatta, respectively, in a list of divine metamorphoses when they mention Zeus’s rape of Persephone in snake form,48 the rape which was part of the Orphic myth about man’s descent from the Titans (above). Both have clearly used the same source, which, as we know that Clement derived the passage from an Attic antiquarian,49 takes us back to Hellenistic times. This evidence for the story’s early date strengthens the position of those scholars who think that this part of the Orphic myth was part of the early Orphic Theogony.50

But how do we know if this poem was read in Athens, and in what context was it performed? To start with the latter problem, there is an interesting, if neglected, aspect of the first verse of the Orphic Theogony, ‘I will sing to those who understand, close the doors ye profane’ (OF 1a: see also §3), namely that it was soon considered to be out of date or difficult to understand.51 The reference to ‘doors’ must originally have presupposed a performance inside a building, in contrast to the outdoor performance of epic poetry during festivals or dramatic poetry in theatres. When it was removed from the context of the original performance, the reference to doors no longer made sense and was reinterpreted or simply left out. That is why both the Derveni Papyrus and Plato allegorise the line ‘close the doors’ by interpreting it as putting doors on the ears of the audience. Their explanation remained popular in later times and can be found in many Greek authors.52 In Roman allusions the doors were dropped wholesale: Horace simply states in his First Roman Ode (C. 3.1.1) of circa 23 BC, Odi profanum vulgus et arceo,53 and Vergil (Aen. 6.258) has the Sibyl call out procul, o procul este, profani.54 No doors here either!

We do not know if the Theogony was performed in Athens but we can be fairly sure that it was read there. In a recent discussion of the rise of Attic rather than Ionic as the medium of prose writing, Andreas Willi has noted: ‘Some writers who had been brought up with Ionic prose were not yet sufficiently used to the novel way of writing in Attic to do so consistently. This, not the geographical origin ofthe author, best explains the curious Attic-Ionic dialect mixture we find in the Orphic Derveni commentary’.55 In other words, the author of the Derveni Papyrus will have read the Orphic Theogony in Athens, where he will also have written his commentary in, very probably, the late fifth century.

A much less well-known text is the Orphic Physica (OF 800–02) or Peri Physeôs (OF 803). As Renaud Gagné has persuasively argued,56 this hexametric poem, in which the Tritopatores play a prominent role, combined theogonic and anthropogonic narratives with a theory of the soul and Presocratic physical doctrine. In other words, it seems to have been an alternative version of the ancient Orphic Theogony, but with more attention to the immortality of the soul and, perhaps, reincarnation. It seems to have lacked any reference to the Titans and was thus perhaps less scandalous and more acceptable to mainstream Athenian thought. A reference to Physika by Epigenes, the prominence of Aer in the poem and the presence in it of the One/Many problem all point to the later fifth century,57 but Gagné thinks it impossible to locate the poem geographically. However, the mention of the Tritopatores and their connection with the winds strongly suggests Athens, because the centre of their cult was Attica and itsenvirons58 and it was perhaps only in Athens that they were connected with procreation. It is also only in Athens that we hear from local historians about their connection with the winds. If the book was not written in Athens, it was certainly read there.

Our penultimate texts are the Orphic Hymns, which are mentioned in the Derveni Papyrus, where in column XXII we are told: ‘And it is also said in the Hymns: Demeter, Rhea, Ge, Meter, Hestia, Deioi’59 (11–12). Quotation in the Derveni Papyrus dates the Hymns at least as early as the later fifth century.60 Dirk Obbink has noted that the line was written in Attic;61 the many divine identifications are a feature that also links it to Attic poetry of the latter half of the fifthcentury.62

Our last text is an Orphic hymn on Demeter’s entry into Eleusis, which has been reconstructed in outline by Fritz Graf. This hymn celebrated the cultural achievements of Athens within the framework of the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, but made some important alterations: it stressed Athens’ role as the Urheimat of agriculture and made references to the Thesmophoria, the most important female festival of Demeter and the source from which originally non-Eleusinian figures, such as Eubouleus and Baubo, were adopted in Eleusis in the late fifth century.63 The influence of the Sophist Prodicus indicates a date for the hymn around the third quarter of the fifth century and its Eleusinian focus suggests Athens as the place of composition, or even Eleusis itself.64

When we review this material we can see that Orphic texts began to be read in Athens after the mid-fifth century. The oldest texts, the Descent to Hades and the Theogony, were Italian imports, but the later ones seem to have been Attic compositions. This demonstrates the great impact Orphism had on Athens for a time, something that is also manifest in the Orphic influence on the Eleusinian Mysteries and the many allusions to Orphism in Plato.65

Aspects of this evidence–literacy, the association with Eleusis, a connection with the Athenian clans of the Lykomids and the Euneids (§3)–demonstrate that the attraction to Orphism was primarily among the higher, if not highest, social classes of Athens. Did members of these classes also lead an Orphic life? It is perhaps not surprising that indications of an Orphic lifestyle begin to appear only shortly later than, or more or less contemporaneously with, the appearance of Orphic writings in Athens. The oldest reference to an Orphic lifestyle is found in Euripides’ Cretans, produced sometime after the mid-fifth century, perhaps about 438 BC,66 i.e. around the same time that Orpheus is mentioned in the Alcestis. In this fragmentary play there is a passage that, unmistakably, must have evoked Orphic ideas for the Athenian spectators:

We lead a pure life since I became an initiate (mystês) of Idaean Zeus and a herdsman (boutês) of night-wandering Zagreus, having performed feasts of raw meat; and raising torches high to the Mountain Mother with the Kouretes I was consecrated and named a bakchos. Wearing all white clothing I avoid the birth of mortals, and the resting places of the dead I do not approach. I have guarded myself against the eating of food with souls (fr.472.9–19 =OF 567).

The passage has often been discussed,67 but it seems clear that Euripides is here combining several ecstatic cults that can be connected with initiation. First the speaker has become an initiate of Idaean Zeus, though we never hear of these Mysteries of Zeus anywhere else.68 He then became a boutês (presumably the same as a boukolos) and finally a bakchos.69 Later sources show that the boukolos was a kind of mid-range Bacchic initiate (Ch. IV.2)70 and the well known, probably Orphic, dictum ‘many are narthêkophoroi, but the bakchoi are few’, which was already known to Plato (Phd. 69c =OF576), suggests that the bakchoi were the highest stage in the Bacchic Mysteries.71 We find the combination ‘mystai and bakchoi’ also in the Gold Leaf from Hipponion (OF474.16), dating to about 400 BC, where it presumably means all the initiates, whatever their stage of initiation; the combination may well have been inspired by the two Eleusinian degrees of mystai and epoptai (Ch. I.2 and 3). Subsequent Leaves have only the terms mystês or mystai, present in both late fourth-century BC Leaves from Pherae and also in a series of later, small Gold Leaves, often accompanied by no more than the name of the deceased.72 The rank of bakchos seems to have been dropped in individual Bacchic initiations in the course of the fourth century BC.

The passage informs us of a number of characteristics of the cults. Of great importance is purity, which is stressed twice with the Greek terms hagnos (9) and hosios (15). This vocabulary points to rituals of purification before the initiation but also to purity of life thereafter. This purity is expressed through vegetarianism, wearing white clothing and avoiding contact with births and deaths (both well-known natural pollutions in ancient Greece).73 Vegetarianism is expressed by the Greek term empsychos, ‘with a soul in it’, which seems to indicate reincarnation. As regards the white clothing, the excavator of the main tomb of Timpone Grande in Thurii, the source of two Orphic Gold Leaves, found un bianchissimo lenzuolo over the cremated remains of the deceased woman, but the ‘snow-whitesheet’ immediately ‘disintegrated when touched by the excavators’.74 Already Herodotus (2.81.2) mentions that participants in Orphic and Bacchic customs wished to be buried in linen. It is probably safe to presume that the white shroud was what the deceased had worn during her rituals.75 We know that the Pythagoreans also wore white clothes and Pythagoras himself, according to Aelian (VH 12.32), dressed in white clothes, trousers and a golden wreath.76 It seems likely that the Orphics followed the Pythagoreans in this respect, as in several others.77

In the Euripidean fragment the lifestyle is connected with Dionysiac rituals, but Orpheus is nowhere mentioned. Yet the combination of vegetarianism (despite the mention of eating raw meat), purity of lifestyle and white linen all point to Orphism. The first two characteristics are also explicitly mentioned in a passage of Euripides’ Hippolytus, where Theseus accuses his son of being a hypocritical Orphic, as he pretends purity but lusts after his stepmother:

Continue then your confident boasting, make a display with your soul-free food, and with Orpheus as your master engage in Bacchic revelling as you honour the smoke of many books(952–54 = OF 627).

Once again we hear of vegetarianism78 but now Orpheus and Bacchic revelling are explicitly combined, together with books which Euripides himself may well have had in his own library,79 for he became increasingly interested in Orphism in the course of his career.80 In the oral society that Athens largely still was in the later fifth century, books in religious activities could raise suspicion. Demosthenes, slandering Aeschines, twice mentions that he had read books for his mother during initiations.81 Greek religion was by nature oral and the invasion of books, which were also used by the Sophists, in the mid-fifth century must have initially raised many an eyebrow and was of course satirised in comedy.82

A neglected aspect of the Hippolytus passage is Hippolytus’ age. He is obviously a very young man, not yet married. A little later in the play he states: ‘I am clumsy at giving an explanation to a crowd, but more intelligent for a small group of my age-mates’ (986–87). We may wonder if in Athens Orphism was at first especially successful with the elite young; we may recall the success of the Sophists with the jeunesse dorée of Athens.

How do we explain the more or less contemporaneous appearance of Orphic books and an Orphic lifestyle? The easiest answer is that both writings and lifestyle were probably imported into Athens by wandering Orphic initiators, the so-called Orpheotelests. The presence in Athens of these initiators in the late fifth century is already attested by the Derveni Papyrus, which tells us:

But all those (who hope to acquire knowledge) from someone who makes a craft of holy rites deserve to be wondered at and pitied–wondered at, because, thinking that they will know before they perform the rites, they go away after having performed them before they have known, without even asking further questions, as if they knew something of what they saw or heard or were taught; and pitied because it is not enough for them to have spent their money in advance, but they also go off deprived of understanding as well (XX).

Like the Sophists, the Orphic initiators evidently asked money for their services, and this is confirmed by Plato in an important passage from the Republic:

… and begging priests and seers go to rich men’s doors and make them believe that they by means of sacrifices and incantations have accumulated a treasure of power from the gods that can expiate and cure with pleasurable festivals any misdeed of a man or his ancestors, and that if a man wishes to harm an enemy, at little cost he will be enabled to injure just and unjust alike, since they are masters of spells and incantations that constrain the gods to serve their end…And they produce a hubbub of books of Musaeus and Orpheus, the offspring of the Moon and the Muses, as they affirm, and these books they use in their rites(364b-e = OF 573 I, translation adapted from P. Shorey).

Interestingly, in the Meno (81a = OF 424, 666) Plato also mentions ‘priestesses’, presumably Orphic ones. Given that upper-class Greek women were not free to wander the streets, other women could probably better cater to their religious interest. The fact that the majority of the Gold Leaves have been found in graves of women demonstrates that women were interested in these new ideas.83 Wemay compare early Christianity, where women also dominated: a Syrian Church Order stipulates that a bishop sometimes did better to choose a deaconess as his assistant, because she had better access to houses in which both Christians and non-Christians lived.84 In his Characters (16 = OF 654), Theophrastus mentions such an Orphic initiator, an Orpheotelest, who had set up shop in Athens and was consulted regarding purity, but the fact that he is associated with the ‘Superstitious Man’ shows that his reputation was not high in the eyes of Theophrastus.

From our discussion it will have become clear that Orphic ideas and practices rejected central values of Greek society of their day. Their asceticism and vegetarianism isolated their followers from occasions associated with sacrifice, the central act of Greek religion, and their eschatological ideas featuring reincarnation and their sense of election as being gods, as we will see shortly, set them far apart from traditional Greek eschatological ideas. This Orphic complex was peddled by initiators as, say, modern Scientology does, through initiations aimed at rich people. During these initiations they offered knowledge, presumably above all eschatological, but also sold spells and incantations. However, we will not focus on Orphic magic here, but turn to the Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries.

The Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries

The earliest mention of Bacchic Mysteries, still without any Orphic influence, occurs in a fragment of Heraclitus of Ephesus, who is commonly dated to about 500 BC, in which he threatens specific groups of people, the ‘night wanderers, magoi, bakchoi, lênai (maenads), mystai’ (B 14), with a fiery punishment afterdeath.85 The mention of bakchoi and lênai, in other words male and female followers of Dionysos, as well as of mystai clearly suggests Mysteries; indeed, in the same fragment we find the word mystêria for the very first time in surviving Greek literature. The occurrence in Ephesus of bakchoi, that is, ecstatic worshippers of Dionysos Bakchos, is not really surprising, as the centre of the cult of Dionysos Bakchos/Bakcheus/Bakch(e)ios was in the Dodecanese and its neighbouring cities on the coast of Asia Minor.86 As Ephesus did not have public Mysteries comparable to those of Eleusis or Samothrace, Heraclitus must have been targeting private Mysteries. This means that around 500 BC there were already private Mysteries of followers of Dionysos Bakchos. Wherever we have more detailed information, this epithet is linked to ecstatic rituals.87 Heraclitus would probably not have worried about these categories had they belonged to the lowest classes of the city.

More or less at the same time, a well-to-do woman in the Milesian colony of Olbia was buried with a bronze mirror with the inscription: ‘Demonassa daughter of Lenaeus, euai! And Lenaeus son of Damoclus, euai!’.88 The shout euai was typical of the maenads and recurs in the form euhoi in Sophocles (Tr. 219; note also Ant. 1134–35) and Aristophanes (Th. 995). The cry, then, was well established before Euripides used it in his Cyclops (25) and Bacchae (141). This is also demonstrated by Dionysos’ epithet Euios, already attested from the mid-fifth century.89 Interestingly, the maenadic cry is here also associated with a male, who even has a Dionysiac name: apparently, in Olbia as in Ephesus, there were male and female Bacchic groups. The shout euai points to ecstatic rites with dancing and chanting.90

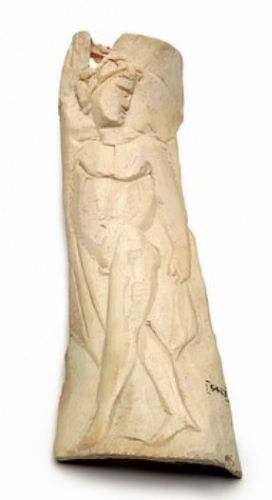

In 1978 a small set of bone plaques from Olbia were published, dating to the fifth century and containing the sequence of words ‘life-death-life’, followed by ‘truth’ underneath; at the bottom of the plaque it read, ‘Dio(nysos) Orphiko(i)’.91 A second plaque reads,‘Dio(nysos), truth, body soul’.92 These plaques evidently refer to a group of followers of Orpheus, that is, of Orphic ideas and, possibly, an Orphic lifestyle, though the expression ‘Orphikoi’ is unique in this meaning, as all later attestations of the term mean ‘producers of Orphic literature’.93 The sequence ‘life-death-life’ and the opposition ‘body soul’ suggest that these plaques are concerned with reincarnation, in which the soul played an important role. In Greece reincarnation was ‘invented’ by Pythagoras, and it seems reasonable to accept that the Orphics had taken it over from him,94 though not everyone agrees with this.95 Yet there is also a tie between these Orphics and Dionysos. The plaques do not specify which Dionysos this was, but around 460 BC the Scythian king Scyles, whose mother was Greek, wanted to become initiated (telesthênai)into the cult of Dionysos Bakcheios in Olbia. Herodotus leaves no doubt about its ecstatic character, stressing it repeatedly (4.79.3–4). The king even joined a Bacchic thiasos before he was deposed and, eventually, beheaded.96Given the later connections between Orphism and Dionysos Bakchios, which we will men-tion shortly, it seems plausible that the Dionysos of the bone plaques also had an ecstatic character. Finally, bone plaques in themselves are not very valuable, but the use of writing surely points to a higher social status, just as the thiasos joined by King Scyles will not have consisted of the riffraff of Olbia.

Around the same time but at the other end of the Mediterranean, an inhabitant of Campanian Cumae was buried in a tomb of large dimensions, the roof slab of which bore the inscription: ‘It is illicit to lie buried in this place unless one has become a bakchos’ (bebakcheumenon).97 The inscription seems to presuppose a group of followers of Dionysos Bakchos/Bakcheus/Bakche(i)os who, again, belonged to the higher strata of Cumaean society. Whether the inscription also presupposes a meeting with other bakchoi in the afterlife remains impossible to say, but does not seem unlikely.

No more than two decades later Herodotus, speaking about the linen garments of the Egyptians, noted: ‘This agrees with the customs known as Orphic and Bacchic, which are in reality Egyptian and Pythagorean, for anyone initiated into these rites (orgia) is similarly forbidden to be buried in wool. A hieros logos is told about these things’(2.81 = OF 650).98 Unfortunately, as is his custom, Herodotus does not tell us the content of this hieros logos,99 but his comments clearly show that he, like Ion of Chios,100 ascribed the Orphic ideas to Pythagoras, which shows how close their ideas were in the eyes of fifth-century intellectuals.

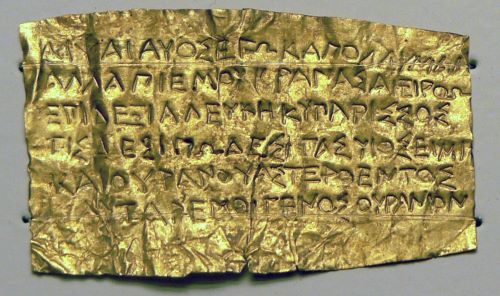

From the evidence collected so far, we can conclude that around the mid-fifth century BC Dionysiac ecstatic rituals had converged with Orphic ideas and practices in some Greek cities. This development is also very much apparent in the Gold Leaves that we have already mentioned repeatedly. These Leaves have been known for well over a century, but the steady publication of new ones in the last four de-cades has greatly increased our understanding of them. The oldest examples were found in southern Italy, and the ‘Doricisms’ in their language support this geographical origin.101 It is now clear that these Leaves served as a kind of passport and guide to the underworld. The passport function is directly mentioned by the first Leaf from Thessalian Pherae to be published, from the fourth century: ‘Passwords (symbola): man-and-child-thyrsos. Man-and-child-thyrsos. Brimo. Brimo’.102 In contrast, the fourth-century Gold Leaf from Petelia in southern Italy starts with, ‘You will find in the house of Hades a spring on the left, and standing by it a white cypress. Do not even approach this spring!’,103 and several others contain even more elaborate instructions. Some hexametrical Gold Leaves also contain snippets of prose, such as ‘Bull you jumped into the milk. Quickly, you jumped into the milk. Ram you fell into the milk’.104 These have led Fritz Graf to the persuasive conclusion that the Gold Leaves were meant for oral performance. Originally, they must have been recited during the bearers’ initiation, to prepare them for what they should say when they died and arrived in the underworld.105

In the Leaf from Hipponion, mentioned above, we read: ‘And you, too, having drunk, will go along the sacred road on which other glorious mystai and bakchoi travel’.106 In 1985 Fritz Graf noted that neither the Cumaean inscription nor the Hipponion Leaf ‘setzen natürlich Dionysos Bakcheus voraus’,107 but only 2 years later two new, late fourth-century Leaves from Thessalian Pelinna were published, which read, ‘Now you have died and now you have come into being, O thrice happy one, on this day. Tell Persephone that Bakchios himself released you’, and a late fourth-century Leaf from Macedonian Amphipolis published in2003 reads, ‘Pure and sacred to Dionysos Bakchios am I, Archeboule (daughter of) Antidoros’.108 As we might have suspected, it is precisely the ecstatic Dionysos who is the focus of these rituals.

We have hardly any information about the rituals underlying these Gold Leaves. A chance remark tells us that Bacchic initiates were crowned with the twigs of a white poplar as it is a chthonic tree. Heracles had also crowned himself with white poplar after his victory over Cerberus, so the symbolism seems clear: the initiates had nothing to fear at their entry to the underworld.109 Philodemus associates an Orpheotelest with a tambourine, which shows that ecstatic dancing was part of their activities110 and is also a valuable confirmation that Orphic initiators were associated with Dionysos Bakchios, as the tambourine was a standard instrument in Dionysiac rituals.111

Finally, the texts seem to suggest communal activities. With the Hipponion Gold Leaf we cannot be certain whether the mystai and bakchoi mentioned were members of a thiasos. However, three fourth-century Gold Leaves from a single burial mound in Thurii start with, ‘I come pure from the pure, Queen of the Chthonian ones’, as does a second- or third-century AD Leaf from Rome (although it begins ‘She comes pure from the pure’).112 In other words, the initiate clearly presented herself as a member of a group of pure initiates.113 And the initiates imagine themselves still as a group also in the afterlife, as the most recently published Gold Leaf from Thessalian Pherae (around 300 BC) states: ‘Send me to the thiasoi of the mystai: I have the ritual objects (orgia) of [Bakchios] and the rites (telê) of Demeter Chthonia and of the Mountain Mother’.114 The new Leaf reveals that the Bacchic initiation also involved ritual objects. Later testimonies from Dionysiac Mysteries mention, for example, the cista mystica with a snake and the winnowing fan with a phallus in it (Ch. IV.2) but it seems risky to retroject these back to the earlier period without further evidence. We also do not know enough about the cult of Demeter Chthonia to infer why she is mentioned, although Demeter became closely associated with Dionysos in the late fifth century. On the other hand, the Mountain Mother, whom we have just met in the fragment from Euripides’ Cretans, was already combined with Dionysos by Pindar (Dith. II.6–9)and was, like him, a patron of ecstatic dancing.115

Were there distinctively Orphic ideas in these elusive Bacchic Mysteries? The Olbian bone plaques pointed to reincarnation and a special position for the soul in the afterlife, as we noted above. The same idea recurs in the Gold Leaves. In one of the Thurii Gold Leaves discussed above, the initiate tells Persephone: ‘I have flown out of the painful cycle (kyklos) of deep sorrow and I have approached the longed-for crown with swift feet. I plunged beneath the lap of the Lady, the chthonian Queen’.116 The ‘cycle’, which also appears in Vergil’s Aeneid Book VI (748: rotam),117 seems to contain the successive stages through which the soul has to pass during its Orphic reincarnation.118 Why was the soul obliged to passthrough this cycle? Here the Leaves also give new answers. The Pelinna Gold Leaf states that the initiate has to tell Persephone that ‘Bakchios himself has released you’, and this forgiving action of Dionysos is probably illustrated on a fourth-century Apulian volute crater by the Darius Painter: Dionysos clasps hands with Hades, who is sitting opposite a standing Persephone, while the image of the deceased at the other side of the vase strongly suggests an intervention by Dionysos on his behalf.119 The reason for Bakchios’ forgiveness probably appears in the Gold Leaf from Pherae that we have just discussed, which states after the mention of the passwords: ‘Enter the holy meadow. For the mystês has paid the penalty (apoinos)’.120 Evidently guilt had to be atoned–and was atoned, presumably by initiation–before the deceased could enter the abode of the blessed. The same guilt is cited in one of the fourth-century Thurii Leaves, in which the initiate declares,‘I have paid the penalty (poinan) for unrighteous deeds’.121

It is almost certain that this guilt is the fact that the Titans had murdered Dionysos: because mankind emerged from the soot of the burned Titans, it shared responsibility for the murder. However, in what is probably the earliest allusion to this murder, in Pindar, there is not yet any mention of Dionysos Bakchios. All that is said is that the best roles in future incarnations will be for those ‘from whom Persephone accepts compensation for ancient grief’ (fr.133), words that seem to refer to the murder of Dionysos.122 It is, I suggest, a reasonable supposition that Dionysos Bakchios’ forgiving role was inserted into the story when his rituals acquired their Orphic colouring.

The last point I wish to make regarding Orphic ideas in the Bacchic Mysteries is to highlight an important difference from the older, Eleusinian Mysteries. In the earlier quotation from the Derveni commentator on the Orpheotelests (§2), he says that the initiates will go away, ‘as if they knew something of what they saw or heard or were taught’. The references to the myth of the Titans’ murder of Dionysos in the Gold Leaves suggest that this myth was also told during the initiations, probably in one of the versions of the oldest Orphic Theogony. The reference to hearing and being taught highlights an important difference between the Eleusinian and Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries. In the former, the importance of ‘seeing’ and ‘showing’ is continuously stressed by our sources as a fundamental part of the highest degree (Ch. I.3), but in the latter the focus is on ‘hearing’. That is surely why hearing, not seeing, suddenly becomes so important in connection with the Mysteries. We can see this already in a line that soon became an alternative opening of the Orphic Theogony, ‘I will speak to those for whom it is right (viz. to hear)’, whereas the oldest version still had, ‘I will sing to those whounderstand’.123 This didactic aspect of the Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries soon caughton.124 In the Clouds (135) Aristophanes calls Strepsiades knocking on Socrates’ door an ‘ignoramus’, amathês, which the Suda later explains as ‘uninitiated’, amuêtos.125 In the fifth century, the more sophisticated initiates were evidently no longer satisfied by the display of an ear of corn as in Eleusis (Ch. I.3).

Until now we have spoken of Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries, which were connected with Dionysos Bakchios.126 Were there also Mysteries with Orphic influence but without Bacchic rituals? In Attic Phlya, Themistocles had rebuilt a shrine of mystery rites (telestêrion) for the Lykomids, his clan, after it was burnt by the Persians127 and in the later second century AD the traveller Pausanias reported that the Lykomids chanted songs of Orpheus and a hymn to Demeter at the rituals in their ‘clubhouse’ (kleision). A klision was a great hall (Ael. Dion.κ30) and Plutarch’s Eleusinian term telestêrion (Ch. I.2) suggests the performance of Mysteries, which were limited to the initiated, in a secluded space. The Lykomids had introduced Orphic poetry into their rituals, as Pausanias noted.128 The resemblance of this ‘clubhouse’ to other Greek ‘men’s houses’ and the ‘wolf’ (lykos) in the clan’s name suggest a background in tribal initiation.129 It seems that some Attic initiatory cults were reconstructed and reinterpreted as Mysteries after the disintegration of male puberty rites in the course of the archaic period.

Another connection between Orpheus and a respectable Athenian family becomes visible in Euripides’ Hypsipyle (ca. 411–8 BC), where Euneus, the ancestor of the clan of the Euneids, is instructed on the lyre by Orpheus (fr.759a.1619–22 = OF 972). The play even seems to contain traces of an Orphic theogony (fr.758a.1103–8 with Kannicht ad loc.= OF 65),130 which we can recognise from the mention of darkness in its fragmentary remains: pha]os askopon (1103)131 and perhaps Aith]er (1104–05) with Night and Eros (1106).132 None of these is exclusively Orphic, but their combination must have evoked the picture of a kind of Orphic Theogony. Such references to Orphic ideas are very rare in tragedy and it therefore seems likely that Euripides knew of some special tie between the Euneids and Orphism. Like the Lykomids, the genos may well have had a club-house where Mysteries and Orphic hymns were performed.133

Similarly there can be little doubt that there were Dionysiac Mysteries without any hint of Orphism. In Euripides’ Bacchae there are many allusions to Mysterylanguage134 yet there is nothing Orphic amongst them, and many later Dionysiac Mysteries clearly have nothing to do with Orphic ideas; indeed, recent research stresses the great variety of Bacchic Mysteries.135 This variety is also reflected in geography, as no Bacchic Mystery is attested for Athens, nor has any Gold Leaf been found in Attica. The prominence of the Eleusinian Mysteries, which also promised a better afterlife, must have hindered any local competition from the(Orphic-)Bacchic Mysteries.136

Conclusions

It is now more than fifty years since the Derveni Papyrus was discovered, and more than forty years since the first new Gold Leaf of the later twentieth century was published. What can we say about the Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries at this moment? When we try to reconstruct the historical development, we seem to see a convergence of East and West, each making a different contribution. Around 500 BC we first hear of Mysteries in Ephesus in which bakchoi play a role, which fits the geographical origin of Dionysos Bakchos/Bakcheus/Bakch(e)ios, as we have seen. It looks as if some people had claimed that the same euphoria that was produced in Bacchic rites in this life was also available to them in the hereafter. Heraclitus’ threat to the initiates of fire after death may be a reaction to the claims of these initiates regarding a blissful afterlife. Around the mid-fifth century, this ecstatic Dionysos has ecstatic Mysteries in Olbia and at the same time he has already been accepted in southern Italy, as witnessed by the Cumaean grave with its term bebakcheumenon.

Around 500 BC, give or take a decade or so, there also arose in southern Italy a movement of people who were dissatisfied with traditional religion. Assuming the name of Orpheus, the most famous poet of the day, they started to produce poems that were close to Pythagoreanism in content but also went into areas to which Pythagoras had contributed little, such as eschatology.137 Unlike Pythagoras, they gave a much more detailed picture of the afterlife, which they disseminated through poems about Orpheus’ descent into Hades to bring back his wife Eurydice. Their eschatological and anthropological ideas must have gradually become better known through books and/or wandering initiators (the Orpheotelests), and their detailed knowledge of the afterlife will have promoted the convergence of Orphic ideas with the ecstatic rites of Dionysos Bakchios.

Shortly after the mid-fifth century, these ideas also reached Athens, as we saw from Euripides. He is the first to mention an Orphic lifestyle, which consisted of a focus on purity and vegetarianism. This lifestyle isolated people from normal social relations and practices. It is therefore not surprising that we find this lifestyle associated with wandering initiators, young people such as Hippolytus and, perhaps, the women of the Orphic Gold Leaves. One need not be a fully convinced follower of rational choice theory to see that such a life had its social costs, such as isolation from public life, which could hardly have been borne by poorer people. Since women, especially, played no significant role in public life, these costs must have been minimal for them. In the modern world, too, New Age cults and ideas have attracted a more than average number of followers from the young and women.

Nonetheless, there must have been an additional factor that made Orphism attractive. We have seen that the Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries were especially at home among the upper classes. In the fifth century, the traditional position of aristocracy in society had increasingly come under pressure, on the one hand through the rise of tyrants, especially in southern Italy, and on the other through the rise of democracy elsewhere. It now became more and more difficult to gain fame–the Homeric kleos aphthiton–in this life, and aristocrats will have looked to the next life for compensation. We may compare Max Weber’s thesis that the rise of religions of salvation, such as Christianity, was the consequence of a depoliticisation of the Bildungsschichten.138 These political developments must have made the idea of reincarnation particularly appealing. Reincarnation is expressed in the Gold Leaves in differing but hardly modest ways: the Leaf from Petelia that we have already discussed tells the deceased that he ‘will reign with the other heroes’, and two fourth-century Leaves from Thurii even assure the deceased that they have or will become ‘a god instead of a mortal’.139 The wandering initiators of the fourth century evidently sold their clients the best possible positions in the life hereafter, no doubt for a good sum of money in this one.

The world of early Orphism has been much elucidated in recent decades thanks to the new discoveries, yet the Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries remain rather inscrutable. Not every ancient Mystery is wholly mysterious, but the light in their darkness remains a dim and flickering flame.140

(See Source for Endnotes)

Chapter III from Initiation into the Mysteries of the Ancient World, by Jan N. Bremmer (De Gruyter, 06.26.2014), published under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.