How these Oriental Mysteries constructed their initiatory rituals in the first centuries of the Roman Empire.

By Dr. Jan N. Bremmer

Visiting Research Scholar

Institute for the Study of the Ancient World

New York University

Introduction

A lack of data is one of the great problems of studying ancient Mysteries. We have also concentrated on the Mysteries of divinities who were already part of the Greek pantheon in the classical period, if not before. In the Roman period there were also Mysteries of gods or goddesses who clearly did not originate within the area of Greek culture. Before we look at the impact of the Mysteries on emerging Christianity (Ch. VI), I have selected those Oriental Mysteries about which we have a reasonable amount of information, namely those of Isis and Mithras. Of these Mysteries, those of Isis (§1) have long fascinated the Western world thanks to their description in Apuleius ’Metamorphoses,1 whereas Mithras (§2) was popularised by Cumont (above, Preface) as the great competitor of nascent Christianity. Together they will allow us to form a better idea of how these Oriental Mysteries constructed their initiatory rituals in the first centuries of the Roman Empire.

Isis

The first mention of Egyptian Mysteries is in Herodotus. In the second book of his Histories, which is devoted to Egypt, he notes that in the sanctuary of Athena, i.e. the Egyptian goddess Neith, in Saïs there is a tomb of a god whose name he cannot reveal for religious reasons. This is not unusual for Herodotus, who is very reticent about cults that require secrecy, especially those connected with or analogous to the Mysteries.2 These words, then, prepare the reader for a possible connection with Mysteries. Herodotus proceeds to relate that there is also a sacred pond in the sanctuary and, ‘it is on this pond that they put on, by night (as inEleusis: Ch. I.2), performances of his sufferings, which the Egyptians call Mysteries’ (2.171.1). Here too Herodotus does not report the name of the relevant god, who is evidently Osiris, as the performance on the pond belongs to the so-called ‘Navigation of Osiris’, which took place during the Khoiak Festival in the autumn/early winter.3 Yet we can be certain that the Egyptians did not call these performances Mysteries, which is clearly Herodotus ’interpretation, as they did not have a general term or exact equivalent for what the Greeks called Mysteries.4

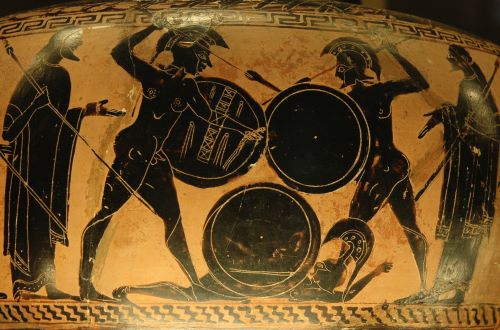

But which Mysteries did he have in mind? Elsewhere in Book II Herodotus interprets Osiris as Dionysos and Isis as Demeter.5 The identification of Osiris with Dionysos is not strange, as Osiris, too, was torn to pieces like Dionysos (Ch. III.3).He was therefore the prime suspect, so to speak, to become Dionysos’ equivalent. This suggests that Herodotus associated the Khoiak Festival not with the Eleusinian Mysteries but with the Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries, the only ones in which the tragic fate of Dionysos played a role.6 In the–admittedly much later–treatise On Isis and Osiris, Plutarch notes that the dismemberment of Dionysos was one of the reasons to identify him with Osiris.7 Herodotus’ passage, therefore, is a valuable testimony for the early occurrence of the murder of Dionysos in those Mysteries(Ch. III.3).

Herodotus is the only early author to connect Egypt with Mysteries, but he does not mention Isis in this connection. It is not until the Hellenistic period that we hear of her association with Mysteries.8 The oldest testimony occurs in a so-called aretalogy, a kind of self-revelation by the goddess, in which Isis enumerates her cultural and cosmological inventions. A total of six of these texts have been found inscribed on stone, dating from about 100 BC to the third century AD; they are all related to one another and probably go back to a specific archetype in the earliest Ptolemaic period.9 The most elaborate one, found in Kyme on the west coast of Turkey and dating to the first or second century AD,10 even thought it wise to confirm the Egyptian credentials of its praises by telling us at the start, ‘The following was copied from the stele which is in Memphis, where it stands before the temple of Hephaestus’(= Egyptian Ptah). Such an ‘authentication’ is a well-known literary topos and goes back a long way in history: the prologue of the Gilgamesh epic already invites us ‘[Find] the tablet box of cedar, [release] its clasps of bronze! [Open] the lid of its secret, [lift] up the tablet of lapis lazuli and read out all the misfortunes, all that Gilgamesh went through’.11 Such fictitious stelae were a common form of religious propaganda in the Hellenistic and Roman period. Usually they occur in contexts that show Alexandrian or Egyptian influ-ence,12 as is hardly surprising: the topos was already current in ancient Egypt.13

That does not mean that these praises can be reduced to a strictly Egyptian background. The stress on Isis’ status as a cultural heroine and former queen of Egypt would hardly be thinkable without the influence of the Sophist Prodicus.14 Yet Egyptian influence is not in doubt, as the beginning of the aretalogy already states: ‘I am Isis, the mistress of every land, and I was taught by Hermes (=Egyptian Thoth), and with Hermes I devised writing, both the hieroglyphic and the demotic, that all might not be written with the same letters’.15 Early students of this aretalogy stressed the Greek content, but increasing interest in contemporary demotic literature has brought to light a number of hymns that put beyond doubt the great Egyptian influence on these praises.16 At the same time, they also demonstrate that the author of this aretalogy was not a slavish copier but an independent author who made his own choices from the available Greek and Egyptian literature.

It is striking that the earliest, still Hellenistic, aretalogies, those of Maroneia and Andros, do not contain the claim, ‘I revealed Mysteries unto men’, which we do find in the first or second-century AD ones of Kyme (24–25) and Ios (23); a nearly second-century AD aretalogy on papyrus also calls Isis‘ mystis at the Hellespont’ (P.Oxy. 11.1380.110–11). Admittedly, the aretalogy of Maroneia (ca.100 BC) states, ‘She (Isis) has invented writings with Hermes, and from these the holy ones for the initiates, but the public ones for everyone’ (22–24); a long digression credits Isis with first revealing the fruits of the earth in Athens and closely associates her with Triptolemos, so the author (and surely also the readers) wants to go hastily to Athens, where Eleusis is the jewel of the city (36–41). Although these lines connect Isis with Mysteries, they claim no more for her than the invention of books in the Mysteries and a close association with the most famous Mysteries of the day, those of Eleusis–not with her own Mysteries.17

All this seems an important indication that Mysteries were a relatively late arrival among the achievements of Isis as perceived by her propagandists. There are surprisingly few data for her Mysteries, despite the attention that initiation receives in Apuleius.18 This is not the communis opinio of the scholarly world, however. The famous Egyptologist Erik Hornung states: ‘Mit der Ausbreitung der Isiskulte über das gesamte römische Reich fanden auch die Isismysterien immer weitere Verbreitung. Von ihrer Bedeutung berichten viele antike Schriftsteller, dazu auch bildliche Darstellungen’.19 Miguel John Versluyseven argues: ‘This aspect (i.e. Isis as a Mystery goddess) is, probably, the defining characteristic of the Hellenistic and Roman Isis in religious terms’.20 Nothing could be further from the truth. There was indeed a Mystery cult of Isis in Rome, as several inscriptions show, and perhaps in some other Italian towns, such as Brindisi;21 we also have an altar dedicated to Isis Orgia in Thessalonica in the second century AD, an epithet that suggests Mysteries,22 and which may well explain a broken column in Cenchreae with ‘Orgia’ inscribed on it;23 we also have references to Mysteries of Isis in Anatolian Prusa and Tralles, probably Samos and perhaps Bithynia and Sagalassos;24 but that is all. Outside Italy, the epicentre is clearly the eastern Mediterranean. None of these Mysteries can be securely dated earlier than the second century AD and none of them provides us with any detail whatsoever of the actual initiation. In consequence, Apuleius’ novel Metamorphoses, which is plausibly dated to the last decades of the second century,25 is of exceptional value for its account of the initiation of its protagonist. It is a literary account and not an anthropological ‘thick’ description, but there is general agreement that Apuleius was very well in-formed about the cult of Isis.26 We will therefore proceed to his account, even if with some trepidation, as there are no other reports to act as a check on Apuleius’ imagination.

We have arrived at the eleventh and last book of the novel.27 In the previous book, the man-turned-donkey Lucius had heard that he had to copulate in public with a woman condemned to death for several murders. We might think that the simple fact of copulation with a human might have been somewhat off-putting, but not for this donkey. On the contrary, a wealthy Corinthian lady had already paid his trainer to have a night of love with him, and Lucius only too happily obliged in what must be the most outrageous love scene in ancient literature.28 But even randy donkeys have their standards, and when he sees an opportunity Lucius flees the theatre and runs the six miles to the seaside of the neighbouring city of Cenchreae.29

At the beach Isis appears to him in a dream and promises to change him back into a human being. The next day there will be a great religious festival and if he plucks the roses out of the hand of her priest he will become normal again. Lucius approaches the priest, devours the roses and, as he tells us, ‘at once my ugly animal form slipped from me’(13).30 The problem of his nakedness is immediately solved by the priest, who nods to a participant in the procession, who gives him his outer, white garment (14, 15).31 Subsequently, Lucius rents a house in Isis ’sanctuary, where the goddess continuously appears in his dreams, urging him to become initiated.32 Yet Lucius delays that final step, considering the many requirements of her cult, not least that of chastity (19).

Apuleius of course raises the suspense with Lucius’ deliberations, but there is perhaps also a more general reason behind this delay: important transitions in life cannot be made light-heartedly.33 Such transitions have to be dramatised, and that is what Apuleius is doing here. At the same time, Lucius promotes his own importance, as not a night passes without the goddess appearing to him and trying to persuade him to let himself be initiated (19: censebat initiari).

After he has had another dream in which the chief priest offers him gifts that clearly have a symbolic meaning (20), Lucius is ready for his initiation, but now the chief priest holds off (21).34 He tells him that the day of the initiation is determined by a nod from the goddess, as is the selection of the administering priest and even the amount of money that has to be paid to be initiated. This is a recurring theme in Lucius’ initiations and the frequency with which he mentions that theme suggests a certain ambivalence, if not outright criticism.35 But, as the priest adds, Lucius is already starting to abstain from certain foods in order that he ‘might more properly penetrate to the hidden mysteries of the purest ritual practice’ (21). As this fasting is the beginning of the process of initiation, now is the right moment to touch briefly on a methodological question, to which previous analyses have not given enough thought. If the Isis Mysteries are indeed relatively recent–as they must be, as they are hardly attested before the second century AD–we must ask: where did the priests get their ideas as they constructed this new ritual of the Isis Mysteries?

The most plausible answer seems to be: from their own rituals and other Mysteries. The obvious candidates in the latter respect are of course the Eleusinian Mysteries and the Mysteries of Samothrace, the most prestigious Mysteries of the period, but the priests may also have considered Dionysiac Mysteries. At the same time, they had their own Isiac rituals in their own Isiac temples–rituals and architecture that must have contributed to the bricolage of the initiation. The existing rituals derived from the priests’ own Egyptian tradition, but they had also been adapted to the Greek and Roman world. We must always be prepared to look both to Egypt and to the contemporary world of the Roman empire when we analyse our material.

So let us return to Lucius. Dreams are clearly an important part of the cult of Isis. The somewhat younger traveller Pausanias (10.32.9) tells us that in Tithorea in Phocis only those who had been summoned by Isis in a dream were admitted to her temple.36 Incubation was practised in some sanctuaries of Egyptian gods, for example in Athens and Delos, and we even hear of dream exegetes there.37 Moreover, many inscriptions to Isis mention that they were erected ‘on the order of the goddess’.38 Apuleius is thus referring to a well-known characteristic of the Isis cult when he mentions these dreams.

The same must be true of the reference to fasting and abstention from certain types of food. The Egyptian priest and Stoic philosopher Chaeremon, who was also a tutor of Nero, wrote a book, whose title is unknown but from which the third-century pagan philosopher Porphyry quotes in his own book On Abstinence. From this we know that the Egyptian priests did not eat bread, fish, carnivorous birds or, sometimes, even eggs. When preparing for an important function in some kind of ritual they had to abstain for a number of days from all animal food, vegetables and sex. From this tradition of ascetic abstention, the Isis priests had clearly made a selection for the initiates in Roman times, perhaps depending on the local ecology.39

Lucius’ patience is rewarded. One night the goddess appears and tells him that the day, so desired by him, has come. Of course she does not forget to tell him the cost of the ritual but, perhaps as a comfort, she also informs him that it is the high priest himself, Mithras, who will initiate him, being joined to him by a ‘divine conjunction of stars’. This astrological detail points to the great interest in astrology at the time as well as to the attested astronomical activities of the Egyptian priests.40 The name Mithras has often set off a discussion of syncretism in the first centuries of the Christian era.41 At the time of Cumont and long afterwards, the term ‘syncretism’ carried a pejorative sense and suggested a mixing of ‘pure’ Christianity or Roman religion with Oriental religious elements. Most scholars today are rather hesitant about using the term, as they have become increasingly aware that all religions constantly borrow elements from other religions or ideologies: there are no‘pure’religions.42 Nonetheless a reference to the competing god Mithras would be rather surprising here. Joachim Quack proposes to interpret ‘Mithras’ as a form of the Egyptian name Month-Re, traces of which can still be found in the magical papyri.43 The proposed identification is hardly plausible from a phonetic point of view, but Apuleius also mentions the Egyptian Zatchlas, a first prophet, whose name has caused equal headaches for Egyptologists, who have not been able to give it a plausible explanation.44 In fact, Mithras as a personal name was not unknown in antiquity, although usually written as Mithres,45 and the name may well point the reader to the cosmological speculations of the Mithras cult, the more so as the description of Mithras as meum iam parentem is redolent of Pater, the highest position in the Mithraic grade system (§2).46

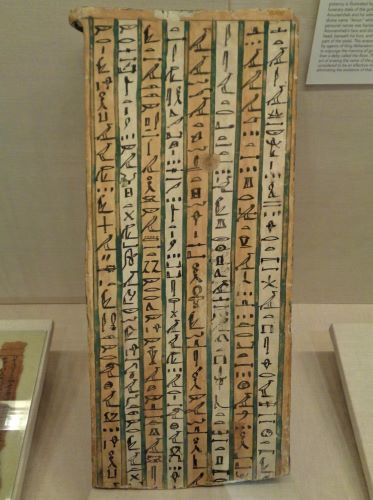

After the usual ritual of the opening of the temple,47 Mithras brings out some books ‘from the secret part of the sanctuary’, to which only the priests hadaccess.48 The books, as Lucius notes, were ‘inscribed with unknown characters. Some used the shapes of all sorts of animals to represent abridged expressions of liturgical language; in others ends of the letters were knotted and curved like wheels or interwoven like vine-tendrils to protect their meaning from the curiosity of the uninitiated’(22.8). The last words look like a contemporary interpretation, but the description is fairly accurate and suggests that part of the books were written in hieroglyphs or, perhaps, the hieratic script.49 It cannot be stressed strongly enough that such a use of books was very uncommon in Greek and Roman religion, although we have seen that books also occurred in the Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries (Ch. III.2). The books of the Egyptian scholarly priests, whom the Greeks called hierogrammateis, ‘temple scribes’,50 were called ‘books of the gods’ or ‘divine books’ in Egyptian, which the Greeks in turn translated as hierai bibloi, ‘holy books’.51 These books were composed, copied and preserved ‘in the temple libraries and the House-of-Life, the cultic library that housed those texts that were seen as the emanations of the sun god Re’52 and which was the place where these writings were discussed.53 In our case we do not know where exactly the priests preserved their books, but the Egyptian script must certainly have helped to raise the solemnity of the occasion, even if Lucius did not understand Egyptian, which the priest perhaps translated or paraphrased.

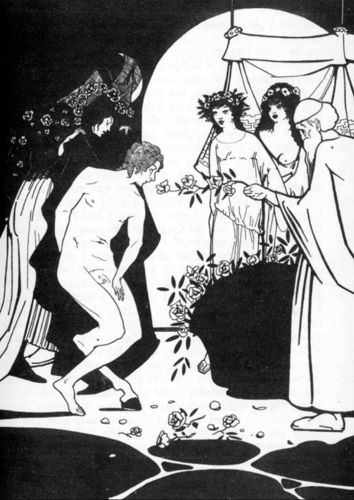

From the books the priest reads out what Lucius had to buy for his initiation. Unfortunately, he gives no details, but one thing is certain: there was no such thing as a free lunch in this ritual! Naturally, he has to take a bath, as such purificatory baths were very common in all kinds of rituals, including several Mysteries, as we have seen (Ch. I.1 and passim);54 the fact that he even receives an additional sprinkling stresses its importance.55 Water was very important in the sanctuaries of Isis and various dedications of fountains to the goddess have survived.56 The priest then asked for forgiveness, another traditional theme in Egyptian priests’initiations.57 Together with the bathing, it meant that the future initiate was now sufficiently pure of body and soul to approach the goddess. The priest next uttered some holy words and ordered Lucius to abstain from meat and wine for a period of ten days. That particular period occurs already in the Bacchanalian Mysteries of the early second century BC, but it is also the normal period of abstention in the cult of Isis in the Late Republic and Early Empire, as we know from the complaints of Roman love poets who missed their girlfriends for that period.58 There were even associations of worshippers of Egyptian gods that met every ten days.59 Evidently, in the construction of the Mysteries the priests once again made use of the traditional rituals of the cult of Isis.

All these preliminary rituals happened during the day, but the actual initiation had to take place at night, the normal time of initiation in ancient Mysteries (Ch. I.2 and passim). Suddenly a crowd of worshippers turned up and honoured Lucius with presents, a custom which seems to have developed in Hellenistic times.60 After all the uninitiated have been dismissed–Apuleius here alludes to the Vergilian procul, o procul este, profani (Aen. 6.258: Appendix 2.1),61 but this banishing of the uninitiated was traditional in the early Orphic-Bacchic Mysteries (Ch. III.2)–Lucius receives a linen robe, as was normal in the cult of Isis.62 The priest takes his hand and leads him into the innermost part of the temple; unfortunately, it is not completely clear how we should imagine this temple, as there was no standardised form.63 At this moment suprême, however, Apuleius fails us. ‘Dear reader’, he tells us, ‘you may awfully wish to know what was said and done afterwards. I’d tell if it were allowed…But I shall not keep you in suspense with perhaps religious desire nor shall I torture you with prolonged anguish’(23.5–6). He proceeds: ‘I approached the frontier of death, I set foot on the threshold of Persephone, I journeyed through all the elements and came back, I saw at midnight the sun, sparkling in white light, I came close to the gods of the upper and nether world and adored them from near at hand’ (23.7, tr. Burkert).

As has often been observed,64 Apuleius has put the description in the form of the symbolon (Ch. VI.3), ‘password’, of the Eleusinian initiates: ‘I fasted, I drank the kykeon (like Demeter in the Homeric Hymn to Demeter), I took from the hamper, after working I deposited in the basket and from the basket in the hamper’(Ch. I.1). Like these phrases, Apuleius’ solemn words are tantalising but ultimately not informative. Yet we should note that they in part refer back to the qualities of Isis we have already mentioned. First, we have the association with the universe, including the underworld, though there are no archaeological indications that this visit to the underworld was symbolised by visits to subterranean corridors or halls, as has sometimes been suggested.65 This theme had been announced by the goddess in the dream to Lucius on the beach of Cenchreae, in which she pronounced a kind of aretalogy of herself. In her Selbstoffenbarung she mentions that she is the regina manium, ‘queen of the dead’ (5.1)–in fact, Lucius himself had already identified the goddess with Proserpina and Hecate, amongst many other goddesses (2)–and at the end of her revelation she mentions that after death Lucius will find her holding court in the underworld and the Elysian fields (6.6). The chief priest had mentioned that the gates of death were in Isis’ hands and that the initiation itself was ‘performed in the manner of voluntary death’ (21.7). In other words, when Lucius mentions that he approached the underworld but also returned, he is alluding to the power of Isis over life but also over death. We know this also from an inscription from Bithynia, in which an initiate tells us that because of his initiation into the Mysteries of Isis he did not ‘walk the dark road of the Acheron’ but ‘ran to the havens of the blessed’.66

Before Lucius returned to the upper world, he also, as he tells us, journeyed through all the elements. Burkert suggests that the elements had to do with purifications, but that is unpersuasive, as Lucius had already been extensively purified.67 His passing through the elements seems rather to be a stage in his journey before returning to this world. These elements are also under the rule of Isis, for in the dream of Lucius we have just mentioned she refers to herself as the elementorum omnium domina, ‘mistress of all the elements’ (5.1), and Lucius later states that ‘the elements are the slaves’ of Isis (25). In Apuleius, elements always refer to the elements of nature, that is, earth, water, air and fire, which make up the sublunary world.68 Lucius seems to have travelled to the boundaries of both the upper and the nether world, which enabled him to actually see the gods of both these worlds.

In his Sacred Tales, Apuleius’ contemporary Aelius Aristides refers to an initiation into the cult of Sarapis,69 the Egyptian god often closely associated with Isis: ‘But that which appeared later contained something much more frightening than these things, in which there were ladders, which delimited the region above and below the earth, and the power of the gods on each side, and there were other things, which caused a wonderful feeling of terror, and cannot perhaps be told to all, with the result that I gladly beheld the tokens. The summary point was about the power of the god, that both without conveyance and without bodies Sarapis is able to carry men wherever he wishes. Such was the initiation, and not easily recognised, I rose’.70 It seems hardly a coincidence that in this Egyptian context we also find an experience of the gods on either side of the earth, even though we are left very much in the dark about how exactly we should imagine this experience.71

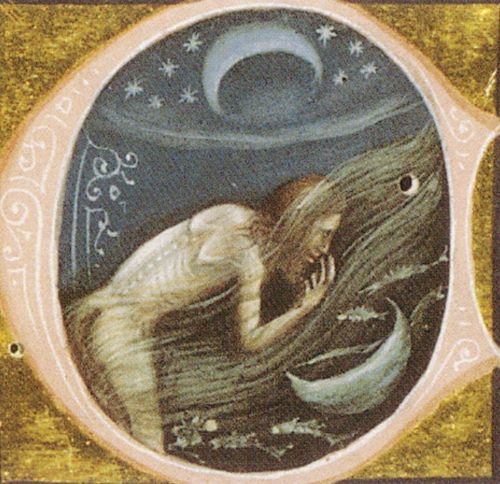

In the middle of Lucius’ description, and thus clearly the highlight of the ritual, we find the mention of the sun at midnight. Egyptologists relate this to passages from the Book of the Dead.72 Although the Book itself had ceased to be copied when the Isis priests started to construct their Mysteries,73 its ideas were still current and would remain so into the third century AD. We may therefore presume that at midnight a torch was lit, as torches were heavily imbued with solar symbolism.74 The priests of Isis may well have looked to the prestigious contemporary Mysteries with which they would have to compete, and they could confidently compare their own fire with that of the great fire at the moment suprême of Eleusis (Ch. I.3). A recently published inscription has shown that the famous Mysteries of Samothrace had taken over not only the Eleusinian light but also the Eleusinian promises of a better position in the afterlife (Ch. II.1). The Mysteries of Isis would hardly have been less spectacular or promised less than the best known Mysteries of Greece.

At the end of his description, and perhaps its climax, Lucius mentions that he had adored the gods from close at hand. It is important to realise how different this is from classical Greek religion. Mythology tells us how Semele was burned to ashes when she saw Zeus in his full glory.75 Here Lucius’ proximity to the gods is stressed, just as he will be displayed on a platform opposite the statue of Isis after his initiation (below). It does not seem impossible that Lucius was confronted with images of the gods or perhaps with frescoes depicting them, though the latter is less likely, given the nocturnal setting of his initiation. The proximity fits the trend towards a closer connection between worshipper and the gods, as can be witnessed in the first centuries of the Christian era.76 That is all we can say about what happened to Lucius in that fateful night: there is no mention of a sacred drama, no mention of Osiris’ suffering. I stress this, as several scholars try to import into Apuleius all kinds of details that we are simply not told.77

The next morning Lucius appeared, ‘wearing a robe with twelve layers (?) as a sign of initiation’, perhaps symbolising his passing through the zodiac.78 He ascended a wooden platform in front of the goddess’s statue in the very centre of the sanctuary. Once again he wore a linen garment. The text does not make clear if he had changed clothes in the meantime, but this time it is described as wonderfully embroidered and what ‘the initiates call the Olympian stole’ (24.3),which suggests that the initiation was seen as a kind of triumph in an Olympiccontest.79 He received a torch in his hand and a crown of palm leaves in order to make him look like a statue of the Sun. Here, too, one is inclined to see a certain resemblance to the Eleusinian Mysteries, as one of its most important officials, the daidouchos, ‘the torch-bearer’, had been made to resemble Helios, in line with the growing importance of Sol/Helios in Late Antiquity.80 This all musthave happened early in the morning, as now the curtains of the temple were opened and the people present were amazed by the view. The new status of the initiate was thus publicly dramatised and advertised. Afterwards, there were meals to celebrate his new ‘birth in regard to the Mysteries’. And that was ‘the perfection of the initiation’, as Lucius remarks (24). He remains in the sanctuary for a few days to enjoy ‘the ineffable pleasure of the holy image’–another indication of the desire for a close relationship between goddess and worship-per, as for the Egyptians, like the Greeks, image and divinity were closelyassociated.81 The novel continues with initiations into the Mysteries of Osiris, but we shall leave it here and move on to a completely different type of Mysteries, those of Mithras.

Mithras

While the Egyptian origin of Isis is perfectly clear and the development of the goddess can be followed over many centuries, the case of Mithras is morecomplicated.82 It is difficult to get a grip on the god’s advance from the ancient Near East to the Roman Empire and, whereas with Isis we at least have Apuleius, we lack any such narrative about the Mysteries of Mithras.83 Our main sources for these Mysteries are archaeological,84 whereas in the case of Isis they are textual.85 Even when we have textual sources for Mithras, they are in the main no more than the mention of his name: in fact, it is probably correct to say that the onomastic evidence, that is, names containing the element ‘Mithras’, is the most important access we have to the early worship of Mithras.

The god must have originated in the first half of the second millennium BC after the Indo-Iranians had left the Indo-European Urheimat. This early date is guaranteed by his occurrence in the Rig Veda (3.59) and in a treaty between the Hittite king Suppiluliuma I and Shattiwaza, king of the Mitanni, ca. 1380 BC.86 The etymology of the god’s name is uncertain, but there is some consensus that it must originally have meant something like ‘contract’,87 though this does not necessarily explain his function either in the ancient Iranian period or during the Roman Empire.

In the Persian tradition the god turns up much later. Theophoric names with the element Mithras start to appear only in the eighth century BC, the oldest in an Assyrian inscription of King Tiglath-Pileser III (745–726) of 737 BC.88 These names–more than 45 different ones for over 300 persons in not only Persian but also Akkadian, Aramaic, Babylonian, Demotic Egyptian, Elamite, Greek andHebrew89–show the great popularity of the god at the time of the Persian Empire. However, in classical times we find the god himself mentioned only in Persian inscriptions of Artaxerxes II (404–359) and Artaxerxes III (358–38),90 while later Greek and Roman historians refer to the god also in connection with Darius III (336–330).91 The spelling of the name as Mithres in Strabo suggests that the god was mentioned already by an Ionian source, as perhaps could be expected.92 From these brief notices we see that the god was closely associated with the kings, whose protector he was, and that he was identified with the Sun.93 It is thus not surprising that many kings were called Mithradates, the most famous being Mithradates VI, the great enemy of Rome. As satraps and other Persian grandees owned large estates in Asia Minor,94 names with Mithras even occur in Lycian andLydian.95

The widespread worship of the god apparently survived the collapse of the Persian Empire at the hands of Alexander the Great, perhaps helped by surviving pockets of Magi,96 the Median priests of the Persians, for in his Life of Pompey Plutarch mentions that in Lycian Olympos local pirates ‘performed certain secret rites (i.e., mystery cults), of which that of Mithras continues to the present day, having been first instituted by them’(24.5). There is a very large chronological gap between these Cilician pirates and Plutarch and, given that the rites were secret, that the pirates were wiped out by Pompey and that Mithraic Mysteries are not attested before the late first century AD, we must conclude that it was Plutarch himself who made the connection between the late Republican pirate rites and contemporary Mithraic cult, and not that he had reliable information about the contemporary cult’s origin.

Like early Christianity, the cult of Mithras burst suddenly onto the Romans scene, albeit somewhat later, in the last decades of the first century AD. In the year 92 the Roman poet Statius ‘published’ his epic Thebaid, in which he compared Apollo to ‘Mithras twisting the horns wroth to follow in the rocks of Perses’ cavern’ (1.719–20, tr. Shackleton Bailey). He had begun his poem around AD 80 (Theb. 12.811), which gives us the timespan within which he will have made the acquaintance of Mithras’ cult.97 Yet the oldest dedications to Mithras, which are from around the same time, were not found in Rome but in Germanic Nida, modern Heddernheim near Frankfurt, from about AD 90 (V 1098), in Steklen in Bulgaria from about AD 100 (V 2269)98 and, perhaps a decade later, in Carnuntum in Austria (V 1718).99

These data have given rise to a fierce debate about the geographical origin of the Mysteries. Against most current experts, Richard Gordon has argued for an origin in Anatolia rather than Italy,100 but this seems unlikely. Anatolia was not far from the two most famous Mysteries, those of Eleusis (Ch. I) and Samothrace (Ch. II.1), and it would have been hard to compete with them, as is indeed illustrated by the rarity of Mithraea in mainland Greece and the eastern Mediterranean.101 It is more plausible to assume that the cult was invented in Rome, where Statius had already seen a statue of the bull-killing god before AD 92 (above).102 An origin in Rome is also supported by the architecture typical of Mithraea, in which the image of the god occupies the central position in the seating arrangements for the banquet, the best parallel for which is the seating installations for funeral banquets in Ostia and Pompeii, in which the grave occupies the central position amid the triclinia. A Roman origin is the more likely in that the cult rooms were clearly designed to contrast with normal Roman sanctuaries–something which is harder to imagine happening in Anatolia.103

Nonetheless there are several Persian details in the cult, such as (1) the association of Mithras with the Persian Mithrakana festival which takes place on the fall equinox, (2) the presence of two attendants for Mithras in the Miθra-Yašt, just as the Roman Mithras has the accompanying twins Cautes and Cautopates,(3) the presence of the raven at a sacrificial scene on a Mithraic altar in Poetovio/Ptuj, which recalls the vulture in the Bundahišn who likewise flies off with a piece of the sacrificial meat,104 and (4) the Iranian garments of the god and his companions.105 Consequently, we should be looking for someone of Persian origin or with Persian connections, perhaps from Commagene,106 but who also spoke Greek, because the initiatory grades seem to have been invented by a native Greekspeaker.107 The most likely explanation of all these data is that the founder came from Anatolia where, as we saw (above), the worship of the god had survived the collapse of the Persian Empire, but who designed the cult in Rome itself. The god must have been exported almost immediately to Germania, given the early dates of the finds there.

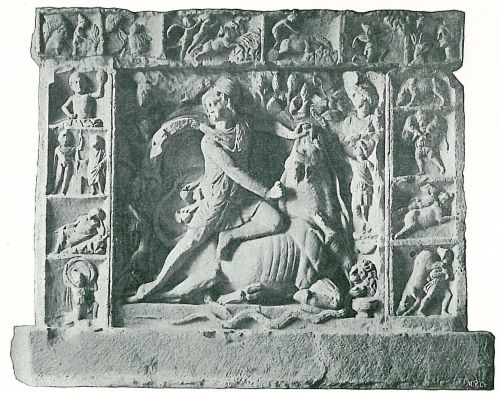

The worshippers met in dark artificial caves or, at least, grotto-like buildings, in the West called spelaea, ‘caves’, which were carefully constructed as a reflection of the Mithraic world but also shaped that world in turn.108 These caves were lieux de mémoire, places where the worshippers remembered and were reminded of the cave in which Mithras had killed the bull that had made him the ‘maker and father of all’.109 In the centre of the rear wall they would see a relief of the god, representing him at the moment he kills the bull, the killing of which was the foundation of the present social and cosmological order. This representation of a god in action in relief form was highly unusual for ancient religion, as they now had to approach the relief to look at Mithras’ action rather than worshipping hisstatue.110 By adorning the caves with stars, the Sun and symbols of the planets, the worshippers expressed their belief in Mithras as the creator of an ordered cosmos who would guarantee the worshipper an ordered life.111 Modern scholars have paid much attention to the astrological and cosmological speculations of ancient Mithraists112 but, just as most modern Protestants have not ploughed through the 13 volumes of Karl Barth’s Kirchliche Dogmatik and most Catholics were not terribly interested in the latest dogmatic insights of Pope Benedict XVI, we need not suppose that most Mithras worshippers followed or were interested in these highly complicated speculations.

As the killing of the bull would normally have been followed by a sacrificial banquet, it is not surprising that on several reliefs we have a representation of such a banquet enjoyed by Mithras and Sol.113 It is clear from the many bones found in and near Mithraea that Mithras’ worshippers followed this example by dining and, especially, drinking together,114 but their sacrifices consisted mainly of suckling pigs and chickens, not bulls.115 In other words, the bull banquet represents the ideal sacrifice, not the real practice: representation of ritual and its actual practice should not be confused.116 In Greek and Roman sanctuaries, it was customary for worshippers to dine in rooms adjacent to the temple after sacrificing on the altar in front of the temple. Mithras’ worshippers, in contrast, dined inside the Mithraeum in the company of their god,117 reclining on two raised podia at either side of and close to the altar,118 although in many Ostian Mithraea there were also ancillary rooms, and outside Italy, where Mithraea were often situated at the edge of town, the food was prepared in dining rooms outside the cave. As the caves were relatively small, the ‘congregation’ had to be small too, about 20 to 50 people.119 This must have made the regular meetings into places of friendship and intimacy where close connections between the worshippers could be formed.

A final aspect deserves attention before we come to the initiation proper. The cult of Mithras was a real man’s world, as women could not be initiated; we might even speak in this respect of a kind of ‘immaculate conception’, as the god was represented as being born from a rock, not from a woman.120 This must have been a conscious choice in the design of the cult, which was later rationalised. ‘Mithras hated the race of women’, we are told by a Pseudo-Plutarchan text (De Fluviis 223.4),121 and a little known but relatively early author on Mithraism, the post-Hadrianic but pre-Porphyrian Pallas,122 says that the Mithraists called women ‘hyenas’, clearly not a compliment.123 We simply don’t know why.124 It may be that this exclusion of women is part of Mithras’ Persian legacy, as the latter’s Ossetic counterpart Wastyrǯi is also specifically agod of men.125 Prosopographical and epigraphical studies have also increasingly elucidated the social composition of these males. It is now clear that they did not consist mainly of soldiers, as Cumont thought. Everything seems to indicate that, on the whole, they were neither very high nor very low on the social scale. There were few senators or very lowly slaves amongst them,126 but rather the middle ranks of the army, imperial staff, and slaves and freedmen of the imperial household, as well as some ordinary citizens.127

How did one get initiated into the Mysteries of this group of males? The precise nature of the initiation is highly debated because we have no narrative about it,128 but we should try to combine the sparse literary and iconographical evidence with the epigraphical material, though the latter is in this respect hardly more informative. Three literary texts are of prime importance. The early (?) Pallas tells us: ‘Thus they call the initiates (mystas) that participate in their rites (metechontas)“Lions”, women “hyenas” and the attendants (hypêretountas) “Ravens”. And with respect to the Fathers…(some words are missing here), they arein effect called “Eagles” and “Hawks”.’129 The Christian author Ambrosiaster, a well-informed Roman clergyman working in Rome in the early 380s,130 writes about the initiation: ‘their eyes are blindfolded that they may not refuse to be foully abused; some moreover beat their wings together like a bird, and croak like ravens, and others roar like lions; and yet others are pushed across ditches filled with water: their hands have previously been tied with the intestines of a chicken, and then someone comes up and cuts these intestines (he calls himself their “liberator”)’.131 It is striking that both passages, although more than a century apart, mention only the grades of ‘Raven’ and ‘Lion’, precisely the ones that, after the rank of Father, are mentioned most in the epigraphical evidence (Lion 41 times, Raven 5 times).132 As these two grades are the most important ones, the inventor of the Mithras Mysteries may well have been influenced by the fact that the Eleusinian and Samothracian Mysteries had only two grades.

Yet around the time of Ambrosiaster, Jerome mentions seven grades in a letter to the Christian Laeta: ‘To pass over incidents in remote antiquity, which to the sceptical may appear too fabulous for belief, did not your kinsman Gracchus, whose name recalls his patrician rank, destroy the cave of Mithras a few years ago when he was Prefect of Rome? Did he not destroy, break and burn all the monstrous images there by which worshippers were initiated as Raven, Bridegroom, Soldier, Lion, Perses, Sun-runner and Father? Did he not send them before him as hostages, and gain for himself baptism in Christ?’133 It may well be significant that Jerome was living in Rome, as was Ambrosiaster and, perhaps, Pallas, because this grade system had clearly taken root most firmly in Rome and the surrounding areas. This is attested also by the seven grades in the floor-mosaic of the mid-third-century Mithraeum of Felicissimus in Ostia and the reference to the grades in the more-or-less contemporaneous Mithraeum of Santa Prisca in Rome.134 The further away we move from Rome, for example in Dacia and Moesia, the less we hear of the individual grades.135 Recent discussions therefore rightly assume that the grade system was fairly flexible and depended on local circumstances.136 The smaller the ‘congregation’, the fewer the number of grades there must have been, one would think.

The seven grades were correlated with the seven planets, as we can see in the Mithraea of Felicissimus and Santa Prisca.137 This has traditionally caused scholars of the Mithraic initiation to take the seven-grade system at face value and so to analyse one grade after the other. Yet this is an insider’s, emic presentation138 and it is more helpful for us to look at the initiation from the outside, to take a so-called etic view. We then see that the grades fall clearly into two groups. The first group consists of Raven, Bridegroom and Soldier, and the second comprises Lion, Persian and Sun-runner, with the Father occupying a place all of his own.139 It is important that Pallas (mentioned above) tells us that the Ravens had to serve. In other words, the lowest grade had to perform menial tasks, just as in Greek symposia the youths had to do the wine-pouring and the washing up.140 And indeed, a raven-headed person offers a spit with pieces of meat to the reclining Mithras and Sol on the fresco of the Mithraeum of Dura Europus.141 Serving will also have been the duty of the Bridegroom, who is associated with an oil lamp on the mosaic in the Mithraeum of Felicissimus.142 Given the darkness of the caves, care of the lighting must have been an indispensable task and was presumably assigned to one of the lower grades. We do not know the duties of the Soldier,143 but Tertullian tells us that when he was presented with a crown on his head, he had to remove it and say ‘Mithras is my crown!’144 The acclamation suggests that the third grade was more closely identified with Mithras himself than the previous two and so constituted the transitional grade between the two groups.

Ascent up the Mithraic ladder did not come without a price. Two frescoes from the Mithraeum in Capua, dating from AD 220–240, and several late literary texts, such as the already quoted Ambrosiaster, depict and recount trials of humiliation and harassment for the initiates.145 The precise details, such as ‘fifty days of fasting, two days of flogging, twenty days in the snow’, may be either Christian exaggeration or attempts to impress Mithraic outsiders, but the fact itself is hardly in doubt and is now supported by the discovery of a so-called Schlangengefäss in a Mithraeum of Mainz, dating to AD 120–140. This earthenware krater depicts what is generally agreed to be an initiatory test in which a seated, bearded man, obviously the Father, aims an arrow at a much smaller man whose hands are tied and genitals are showing, surely as a sign of humiliation.146 It seems reasonable to suppose that the roughest treatment of an initiate would take place at the beginning when he was still fairly unknown to the others. I would therefore assign these tests to the first grades, who at the banquet also, surely, had to recline, if at all, furthest from the relief with Mithras.147

We move into a new group with the Lion, Persian and Sun-runner. The division is warranted because of the importance of the Lion, which is, after the Father, the grade that is mentioned most in epigraphy and seems to have held a normative status.148 As we saw above, Pallas called the Lions ‘those who have been initiated in the rites’. In other words, the previous grades were preparatory in character. Expressions such as pater leonum, and leonteum as a designation for a Mithraic sanctuary, point in the same direction.149 The Lions were especially associated with fire and they seem to have concerned themselves with the burning of incense, as we read on the walls of the Santa Prisca Mithraeum in Rome:

Receive the incense-burners, Father, receive the Lions, Holy One, through whom we offer incense, through whom we are ourselves consumed!150

Porphyry tells us that the Lions were initiates of fire, and that honey rather than water, which is an enemy of fire, was therefore poured on their hands to purify them and their tongues were purified of guilt by honey too.151 These purifications also show that this grade was the real start of becoming an initiate of Mithras. We should not forget that Isis initiates had to confess their sins too (§1) and that in later antiquity the Eleusinian initiates not only had to be free of bloodshed but also had to be ‘pure of soul’ (Ch. I.1). At the end of the purification, in order to confirm the initiation, the Father solemnly shook the hand of the new initiate, the mythical reflection of which can be seen on those Mithraic reliefs where Mithras shakes hands with Sol.152 The symbolic character of the handshake was so important that the initiates could also be called syndexi, ‘the united handsha-kers’.153 Given the importance of the Lion grade, it is not surprising that we hear very little about the next grades, Persian (Perses) and Sun-runner (Heliodromus).

The top grade was the Father (Pater), which is also the grade mentioned most often epigraphically; we even hear of a Father of the Fathers (p(ater) patrum: V 403,799;AE1978: 641), presumably to mark his authority over other Fathers. We are reasonably well informed about his role.154 He was clearly the head of the Mithraic ‘congregation’ and supervised both the meal and the setting up of votive altars, as his permission to do so is sometimes mentioned.155 The fact that he is occasionally called Father and Priest (pater et sacerdos: V 511) confirms what we would have supposed anyway, viz. that he supervised the sacrifices.156 Given that he solemnly shook the hand of the new initiates, he will also have supervised the initiations in his sanctuary.157 Finally, as one Father mentions that he was a stu[d(iosus) astro-logia[e] (V 708), we may safely assume that most other initiates were not. It is the Father who will have been the intellectual ‘archive’ and inspiration of the Mithraic worshippers.

The frequent occurrence of the Father in the epigraphic record might give the impression that anyone could become a Father. Yet this cannot have been true, and the reason should be obvious. In the hierarchical structure of the Roman Empire it would be impossible to imagine that an ordinary private soldier could give commands to an officer, or that an ordinary citizen could be superior to someone high up in the imperial household.158 This must have been clear to those Lions who belonged to the lower social strata of the Mithraic ‘congregation’, and they probably did not bother to become initiated into the higher grades. The mention of the Father’s role by Jerome and his representation at the top of the grades of the Mithraeum of Felicissimus, then, must have been an ideal representation, rather than a realistic one, of the initiatory grade system.159

Conclusions

What have we learned from this survey? There are five points I would like to stress:

First, when we now look back at Burkert’s definition of Mysteries as discussed in the Preface (‘initiation rituals of a voluntary, personal, and secret character that aimed at a change of mind through experience of the sacred’), we can see that the examples of Isis and Mithras conform much better to Burkert’s definition than the prototypical Eleusinian Mysteries.

Second, over time, a striking shift took place from collective to individual initiation and from territorially fixed Mystery cults to mobile ones. In classical Athens there was still a large group of people who went annually in official procession to Eleusis (Ch. I.2); similarly, in Samothrace there was a large hall where the initiations took place (Ch. II.1). Later we hear nothing of the initiatory experience or of special groups of Eleusinian initiates in Attica. The earliest Orphic-Bacchic worshippers may still have met communally, but the Gold Leaves are already the product of individual initiations without a detectable geographical centre. In the cases of Isis and Mithras, the initiations seem to have been individual from the very beginning, and their Mysteries were characterised by a never-expanding mobility. We can see how ancient religion had developed in the late Hellenistic and earlier Roman period into a religious market that no longer identified itself with the civic community of the city. It had made space for smaller groups that were no longer under the immediate control of the civic elites but were instead the products of religious entrepreneurs.160

Third, initiation required investments of money and time. This was already the case with the Eleusinian Mysteries but seems to have become a fixed element of all subsequent Mysteries. Consequently, these were not something for the poor and needy. More interesting, though, are the ‘symbolic’ costs. It is well known from modern research into processes of conversion that, in order to minimise the costs of conversion, people prefer to convert to religions or denominations that are fairly close to their current faith.161 The situation is of course different in a polytheistic system, for which we can hardly speak of conversion in our sense of the word. Yet allegiance to a cult can have its ‘symbolic’ costs too, as we learn from Apuleius, who tells us that the initiates of Isis had to wear a linen garment (above) and have a fully shaven head (10).162 This must have meant that many upper-class males will have refrained from this initiation, and it is noteworthy that Apuleius does not mention the shaving of Lucius’ own head in his initiation into the Mysteries of Isis.

Was this different in the cult of Mithras? According to the Church Father Tertullian, the initiates of Mithras were marked (signat) on their foreheads. This information has been contested, but not persuasively.163 The fact that Gregory of Nazianzus mentions burnings in the Mithraic initiations suggests that the worshippers of Mithras were only symbolically tattooed or that a term was used that could be interpreted in that way, because the term for tattooing was reinterpreted as ‘branding’ in Late Antiquity. The respectable worshippers of Mithras would certainly not have accepted real tattoos, as that would have characterised them asslaves.164

Fourth, the worshippers of Mithras must have formed a relatively tight-knit group, even though their social identity will not have depended on the cult, which was not exclusive, for some Mithraists worshipped other gods as well. We usually do not know which ones,165 but in the dominant polytheistic system total exclusivity was highly unusual. On the other hand, the worship of Mithras must have been very important for the worshippers, given the investments they had made. Mithras certainly fits the tendency towards the dominance of one god in the earlier Roman Empire166 and his main epithet Invictus, ‘Unconquered’, may well have been a comfort to his worshippers.167 Isis too was a powerful divinity of this kind168 who was worshipped by various associations called Isiastai or Isiakoi, and even some of her initiates had formed a special association,169 but numerically these remain well behind the ever increasing number of newly discovered Mithraea. Clearly, not every Mystery exerted the same fascination on the inhabitants of the Roman Empire.

Fifth, how traditional were these cults? Readers will have noticed that they have heard surprisingly little about authentically Egyptian and Persian motifs. That is indeed true. Yet there is a great difference between the two Mysteries. In the sanctuaries of Egyptian gods in the Roman Empire there were many artifacts to remind the visitor of Egypt, such as obelisks, hieroglyphs, statues, sphinxes and sistra, to mention only the most striking objects.170 In the Mithraea, on the other hand, there were far fewer visible or audible Persian elements. There was the Persian appearance of the god himself, the occasional use of a Persian word such as nama, ‘Hail!’, or the image of the Persian dagger, akinakes, which was correlated with the grade of the Persian, and that is more or less it.

So how are we to understand this difference? The reason may become clearer if we compare these cults with modern Buddhism. It has been observed that the forms of Asian Buddhism that have proved most congenial to Westerners are those that come closest to their own Enlightenment values, such as reason, tolerance, freedom and rejection of religious orthodoxy.171 In other words, if an Asian religion wants to be successful in the West, then it has to shed most of its Oriental features. Or, if we apply this to antiquity, the cults with an Oriental background that wanted to be successful had to be as un-Oriental as possible. An exotic tinge interested outsiders, but the cult had to remain acceptable in general–so nottooexotic.172 This difference between the Mysteries of Isis and Mithras partly explains their varying degrees of success.

Finally, Franz Cumont imagined these Oriental cults as important rivals of early Christianity. We will see in our next and final chapter whether that was really true.173

See source for endnotes

Chapter V from Initiation into the Mysteries of the Ancient World, by Jan N. Bremmer (De Gruyter, 06.26.2014), published under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.