The deity that is depicted on the clay disc from Pella is not easy to identify.

By Dr. Nikos Akamatis

Research Centre for Antiquity

Academy of Athens

By Nadhira Hill

IPCAA Graduate Student

University of Michigan

Introduction

In 1979, excavations in the eastern cemetery of Pella brought to light, among other finds, a small clay disc that depicts a three-headed deity. This rare object was found with several vases and figurines that allow its dating in the early Hellenistic period. In this article, after a short description of the find, and an examination of its context, special emphasis is given to the identification of the depicted deity and her most probable relation with the goddess Hekate. The clay disc possibly had a magic-protective character related with the passage of the dead to the underworld.

Excavation Context

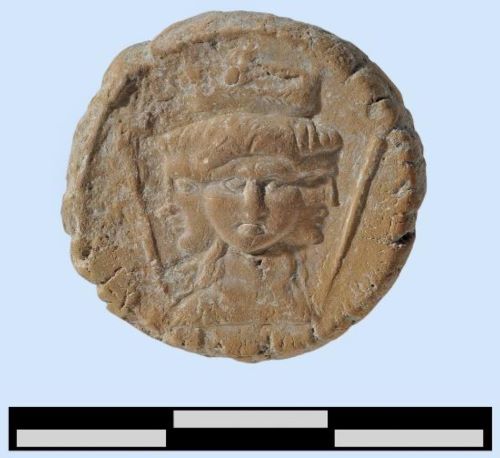

In this article is examined a small clay disc decorated with the figure of a three-headed deity1 (Fig. 1). This rare find came to light in the excavations of the eastern cemetery of Pella, Macedonia. After a short presentation of the object itself and its context, we are going to examine the presence of similar finds in the ancient Greek world, and approach various issues, such as the artefact’s symbolic meaning and its dating, along with some remarks on the cult of Hekate and other three-headed deities in northern Greece.2

The clay disc is rather small, having a diameter of 0.023m. The clay is fine,hard, and contains flecks of golden mica and few admixtures. The color of the clay is light brown according to the Munsell soil chart3. On one side of the disc a mold made bust of a three-headed goddess is depicted (Fig. 1). The central head is shown frontally, while the other two are shown in profile. Locks from her long hair cover part of the neck and the shoulder. The goddess wears a polos decorated with chevrons. Two torches are shown diagonally in front of the side faces of the goddess.

On the flat reverse side of the disc, two small ovoid stamps are visible4 (Figs. 2-3). One of the stamps is possibly decorated with a star, while the other motif is unidentifiable, because the second stamp is very worn. On the side view of the disc there is a small hole that can possibly be related with the tool that its maker used to extract the object from its mold.5

The disc we are examining was found in the excavation of the eastern cemetery of Pella in 1979.6 So far, excavations in various plots of this area have brought to light approximately 300 graves that are dated mainly from the second half of the 4th until the early 1st centuries BC.7 Numerous types of graves have been found, especially cist, pit, roof-tile covered graves and rock-cut chamber tombs.8 Rather few are the cist graves with painted decoration9 and the Macedonian tombs.10 Most of the burials are inhumations, and only some cremations are attested. There are also few multiple burials within a single grave. Several of these graves had numerous offerings, mainly vases, figurines, jewelry, coins, and other finds that are characteristic of the late Classical and Hellenistic periods in Pella.11 Finally, in the cemetery several grave stelae have also come to light.12

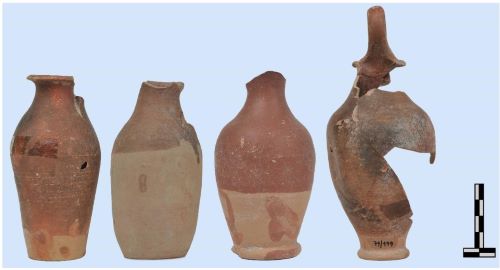

The small disc we are examining came to light in the fill of the cemetery, specifically in trench Θ/65, 0.54m. below ground level. It is not associated with a specific burial since no grave was found close by. However, in the same trench (Θ/62-65), numerous black-glazed vases came to light in close distance; these include 4 olpai,13 3 bowls,14 a one-handler,15 and a bolsal,16 all of local manufacture17 (Figs. 4-6). The vases mentioned above belong to common shapes found all over northern Greece, and especially in Pella and Olynthus.18 Also, alongside the vases numerous fragmentary figurines came to light, most of which depict a standing youth wearing a chlamys and a pilos.19 The finds mentioned above are possibly associated with the same context, and can either be related with a destroyed grave, or with a purification ritual in honor of the dead.

Although the clay disc is not easy to date by itself, the other finds, especially the vases, can all be dated in the last quarter of the 4th century BC.20 It is also important to note that most of the graves and the finds that came to light outside the burials from this part of the cemetery are placed in approximately the same chronological period, from the second half of the 4th until the beginning of the 3rd centuries BC.21 In conclusion, the clay disc depicting the three-headed deity should most probably be dated in the early Hellenistic period, and more precisely in the last quarter of the 4th century BC.

Remarks on the Iconography of Hekate and Other Three-Headed Deities

The three-headed goddess that is depicted on the clay disc from Pella at first leads us to a connection with Hekate, a goddess that was related with several aspects of human life in antiquity: she offered prosperity, victory in battles and games, eloquence, and was considered protector of herds and fishing, and of childbirth and children. She was also a chthonic deity related with magic and the passage of the dead to the underworld. Finally, Hekate protected the believers from dark forces and spirits and was considered a guardian of three-way crossroads.22

In a passage from his Description of Greece, Pausanias recalls two sculptures of the goddess Hekate on the island of Aegina: one of wood made by Myron, depicting Hekate with “one face and one body” (ὁμοίως ἓν πρόσωπόν τε καὶτὸλοιπὸν σῶμα); and one of stone made by Alkamenes, depicting “three images of Hekate attached to one another” (ἀγάλματα Ἑκάτης τρία ἐποίησε προσεχόμενα ἀλλήλοις).23 While an apparently straightforward picture of the development of the image of Hekate in the Greek world, one must consider whether this shift occurred throughout the Greek world at the same time. We are unable to know this for certain, but what we can determine is that, from the description in Hesiod’s Theogony,24 Hekate was worshipped in Greece as early as the 8th century BC as a goddess with a single body. This may have been the case down to the mid-5thcentury BC, when, according to Pausanias, Myron’s wooden statue of Hekate was created. However, between the 8th and 5th centuries BC little archaeological, iconographic, or additional literary evidence exists to further support the idea that Hekate was imagined only as a goddess with a single body and face during that time.25

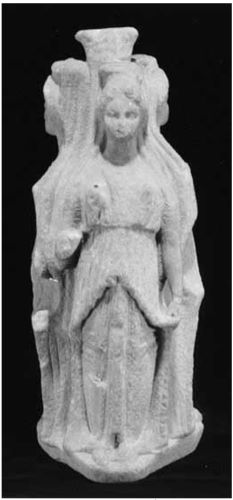

A similar discrepancy exists between the depictions of Hekate in ancient art and literature. As mentioned above, in one of our earliest references to Hekate in ancient Greek literature–Hesiod’s Theogony–Hekate is described as a goddess with a single body who rules over three worldly realms –the earth, the sea, and the sky.26 However, Hekate is often depicted as three female deities, oftentimes encircling a pillar, particularly during the Hellenistic and Roman periods (Fig. 7). It is likely that this depiction was made popular by Alkamenes when he “first made three images of Hecate attached to one another” in the second half of the 5thcentury BC.27 Indeed, even in the3rdcentury BC Hekate is recognized as being “trimorphos” or triple-bodied in the ancient literature: in particular, Lycophron describes her as being ΒριμώΤρίμορφος, a very different image than the one offered by Hesiod five centuries earlier.28

In addition to being portrayed as three goddesses surrounding a pillar, Hekate is also often depicted as a single female deity with three faces and one or three bodies in both relief and free-standing sculpture.29 In literary sources Hekate is described as τριπρόσωπος,30, τρισσοκέφαλος,31 τριοδίτις,32 and τρίμορφος.33 Depictions of Hekate with three faces and a single body or three bodies are much more ambiguous. It has been suggested that Hekate was depicted with three heads, as in the depictions of Hekate with three bodies, to reconcile the triple responsibility she is described as having in Hesiod’s Theogony.34 This triple responsibility may further be manifested in her role as guardian of three-way crossroads. Exactly when this idea –Hekate depicted with three heads –may have taken hold in the minds of ancient Greek artisans is unclear, but we do have evidence from images and texts that suggests that the idea of a triple-headed being was not one that only became popular in the second half of the 5th century BC.35 On the clay disc from Pella, since only the neck and shoulders of the deity are shown, it is not clear if the goddess had a single body or three bodies or if her body had the form of a herm.36

Similarly, Hekate’s depiction in vase painting between the 5th and 4th centuries BC is puzzling, when it was observed by Pausanias that, at least in statuary, Hekate was depicted as being triple-bodied. In vase-painting, when she rarely appears, she is almost always shown as a goddess with a single body and face, which has contributed to some apprehension in identifying her with any certainty as she resembles many other humans and deities.37

The pair of torches that are shown on the clay disc from Pella can also be related with the iconography of Hekate. In the work of several authors, the goddess is called φωσφόρος,38 δαϊδοφόρος,39 δαδοῦχος,40 and, also, it was said thatσέλαςἐν χείρεσσινἔχουσα (“she held bright flame in her hands”).41 Oftentimes in various works of art the goddess is depicted holding two torches, as was most probably the case with the clay disc of Pella42 (Fig. 8). Torches are related with the chthonic character of Hekate, who is referred to as χθονίαor καταχθονία, the deity that helped Demeter descend to the underworld to find her missing daughter.43 Hekate was also responsible for assisting the souls of the dead in the underworld.44

In ancient Greek iconography torches are associated with wedding processions, cult activities and rituals in honor of the dead. The use of the torch, attested in both the images and texts depicting wedding processions already from the time of Homer,45 is manifold, but perhaps the most important associations of the torch with weddings are the liminal and public nature of the procession.46 In funeral processions, torches were necessary for lighting the way to the burial site as well as offering some amount of protection to the deceased and their family. Moreover, considering the other contexts in which the torch is used, the inclusion of Hekate in scenes of Persephone’s abduction and anodos in Greek art appears to be two-fold. On the one hand, it confirms Hekate’s role in guiding others –Persephone, Demeter, Hades –to and from the Underworld. On the other hand, her presence in these scenes further serves to “announce” either Persephone’s return to Earth or her descent into the Underworld, just as the torches in a wedding procession publicly “announce” the union of a couple to their community.47

The polos is another iconographic element related to the iconography of Hekate since this head cover is often worn by this specific deity. However, in most of the depictions of three-headed Hekate, the goddess is wearing a different polos on each head; only on rare occasions (Fig. 8) does she appear with a single polos covering all three heads as on the clay disc from Pella.48

The star symbol depicted on one of the stamps of the back side of the clay disc can also be related to the iconography of Hekate, since she was considered a goddess of the night.49 According to ancient authors, Hekate was the daughter of Asteria50 or Nyx (the night).51 Symbols of the night, such as the crescent and the star, often appear in depictions of Hekate, especially in the Roman period.52

Although the iconography of the three-headed deity we are dealing with is primarily associated with Hekate, other deities share similar characteristics as well. The deity with which Hekate was mostly connected in antiquity was Artemis.53 In Hesiod’s Theogony, Hekate appears to be a cousin of Artemis, since her mother, Asteria, is a sister of Leto.54 Hekate and Artemis also share several common attributes and epithets, such as πότνια, κουροτρόφοςand ταυροπόλος.55 In addition, Euripides mentions that Hekatewas a daughter of Leto,56 while Hekate also appears as an epithet of Artemis herself (ἊρτεμιςἙκάτη).57 Moreover, Artemis was a goddess venerated in three-way crossroads just like Hekate, with the epithets τριοδίτιςor ἐνοδεία,58 and was seldom depicted as a three-headed goddess.59 The torches and the polos are also characteristic attributes of Artemis directly related with her iconography.60 Finally, Artemis also had a chthonic character, although not as strong as Hekate.61

Another goddess that was closely connected with Hekate and Artemis was En(n)odia, or the Great Pheraian Goddess. En(n)odiawas the Thessalian parallel of Hekate, and shared similar attributes, since she was also a goddess of magic and the night, a protector of childbirth, children and the dead, and a goddess of crossroads, among others. The cult of En(n)odia is attested not only in Thessaly, but also in Macedonia.62 In literary sources, Ἐνοδίαor Εἰνοδίαappears as an epithet of Hekate, while En(n)odia is also mentioned as Hekate ἑτέρα.63 Regarding her iconography, En(n)odia is depicted holding torches, oftentimes accompanied by a dog, just like Hekate. A major difference from the iconography of Hekate is that En(n)odia is usually shown on horseback or accompanied by a horse.64 She usually appears as a deity with a single body and head. However, according to Chrysostomou, three-bodied representations of this deity in the form of marble or stone statuettes (hekataia) are also a possibility, especially in the regions of Thessaly and Macedonia.65

Depictions of Hekate trimorphos are also often interpreted as reflecting Hekate’s close association with Demeter and Persephone.66 While it is true that Hekate plays a significant role in the abduction and anodos (“return”) of Persephone in both the Homeric Hymn to Demeter and in later depictions on red-figure vases, it is not correct to see Hekate as a transformed version of Persephone (in the guise of Hades’wife) or even as a daughter to Demeter in her own right.67 Such interpretations would certainly place Hekate within the Greek tradition rather than lend further support to scholars who believe that she was imported from Asia Minor.68 However, as can be seen in both the images and texts, Hekate’s role in the episodes surrounding Persephone and Demeter in myth is clearly a guide, as she carries torches to light the path for both characters and facilitates their transition between the worlds of life and of death.

Finally, it should be noted that other deities that have been related with Hekate may also appear on some occasions as three-headed in Greek mythology, such as Persephone,69 Selene,70 and the Roman goddess Trivia.71 Most of these conceptions, however, are dated to the Imperial period, mainly in literary sources, and rarely appear in various forms of art. Therefore, it is unlikely that Selene, Persephone or Trivia may be depicted on the disc that is examined in this paper.

Conclusions

The deity that is depicted on the clay disc from Pella is not easy to identify because of the religious syncretism that oftentimes characterizes Greek cult. Although the identification with Hekate is most probable, it should not be accepted as self-evident,

due to the lack of an inscription, and because of the similar iconographic elements that are shared by other deities as well, mainly Artemis and En(n)odia. In Macedonia traces of the cult of Hekate are rather scarce. Besides the possible identification of a rural sanctuary of Hekate or En(n)odia in the region of Liknades Voion of Upper Macedoniam,72 the cult of Hekate is basically testified from the three-bodied statuettes, the hekataia, which are traditionally related with this specific deity. Several such statues have come to light in Macedonia, and almost all of them are dated to the 2nd and 1st centuries BC.73 In Pella two such hekataia have been found, one of which came to light in the fill of a road of a town block south of the Agora and was most likely originally placed at a crossroads of the ancient city.74 According to P. Chrysostomou, statuettes depicting three-bodied or three-headed deities found in the regions of Macedonia and Thessaly should not necessarily be related with the cult of Hekate, since equally possible is their identification with Artemis Hekate, Artemis Enodia, Artemis Pherraia, Artemis Trioditis, En(n)odia or the Perraian goddess.75 In fact, the only inscribed hekataion from Macedonia that came to light in Kastania Pieria bears a dedication to Artemis Hekate.76 Finally, there are also rather few theophoric names of Hekate in Lower Macedonia.77

In contrast to the rather limited presence of Hekate in Macedonia, the cult of En(n)odia was quite widespread already from the Classical period. It is attested in cities, such as Pella, Veroia, possibly Lete, and in several sitesin Upper Macedonia, a region connected with land routes with Thessaly where En(n)odia was mostly venerated. The cult of En(n)odia in Macedonia is attested from several reliefs, inscriptions and possibly statuettes.78 Furthermore, a sanctuary dedicated to En(n)odia has been identified in Exohi Eordaia, in Upper Macedonia.79 Besides En(n)odia, the cult of Artemis Hekate is also attested in north Greece, especially in Thasos and in the region of Pieria.80

Despite the common characteristics with Artemis and En(n)odia, it is evident that all the major iconographic elements of the deity that is depicted on our clay disc, such as the three heads, the polos, and the torches, are all related with Hekate. With this specific deity can also be connected the findspot of the disc within the boundaries of a cemetery. While En(n)odia and Artemis Hekate share several similar characteristics and should not be excluded from the identification of the deity on our disc, they were mostly depicted as deities with one head. Also, En(n)odia was usually accompanied by a horse, which does not appear on the disc from Pella. However, the case of religious syncretism of the three deities cannot be excluded; hence, we cannot overrule that the deity of our disc, who has the characteristics of Hekate, could be conceived by its owner as a representation of En(n)odia or Artemis Hekate.

The clay disc from Pella can be compared with few works of minor arts, such as clay sealings and magic stones that are, however, mostly dated in the Roman times. Especially on clay sealings from Delos, Hekate appears as a whole figure with one head,81 or more rarely with three heads.82 She is also depicted on magical stones and pendants of magic character that were especially common in the Roman Imperial period, and, also, on several marble or clay reliefs. On these items the goddess’ body is shown, and she appears either with one83 or with three heads (Fig. 8).84

Understanding the symbolic meaning of the clay disc is also challenging. Similar relief circular plaques on stone, bone, glass, lead, bronze, and clay have been interpreted as seals, tokens, theater tickets or magical items.85 Although the disc from Pella could have had any of the uses mentioned above, primarily it must have had an apotropaic significance emphasized not only due to its location in the eastern cemetery of the ancient city, but also because of the depiction of a chthonic deity, possibly Hekate, a goddess whose role was to guide and protect souls in their journey to the Underworld. It is also likely that the item also had a magical-protective character, since Hekate and En(n)odia were both goddesses of magic.86

(See endnotes and bibliography at source).

Originally published by Karanos: Bulleting of Ancient Macedonian Studies 4 (2021, 59-77) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.