Numerous initiatives gave rise to an artisanal and industrial sector.

Introduction

The survival of an overseas colony depended on the promotion of local businesses, the harvesting of natural resources and the production or supply of basic necessities such as food.

This article deals with the beginnings of commerce during the era of French colonization in North America. Whaling and cod fishing, both seasonal activities, prompted the settlement of the first French colonists on the continent. Of course, only a small proportion of the population were directly involved, but fishing and whaling nevertheless continued to be a significant component of the economy throughout the course of the French regime and even much later.

But the fur trade was the real economic driver of New France. The harvesting of furs created wealth, stimulated the exploration of the continent and created alliances with many Aboriginal peoples.

Lastly, although France’s mercantilist policy prohibited the establishment of companies likely to compete with those of the mother country, numerous initiatives gave rise to an artisanal and industrial sector.

Basque Whalers

Overview

The Basques, from the Pyrennes region between modern France and Spain, had been hunting whales in their own waters since at least the 11th century. By the early 16th century they were venturing out across the Atlantic to visit the Gulf of St Lawrence and adjacent areas, at least 20 years before the “official” voyages of discovery financed by Francois I. Every year they set out in pursuit of their precious prey, at the time considered fish (called “Lenten bacon, fast fish, blubber fish” or “crapois”). Whale meat and fat were indeed highly prized and the blubber was used to make oil for lamps. In 1534, Jacques Cartier encountered many Basque whalers on his first expedition to North America, mainly in the Strait of Belle-Isle, which separates the island of Newfoundland from Quebec and Labrador.

The following article recounts the history of whale hunting as practised by the Basques. After providing a detailed description of the evolution of this practice and the resources found in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, it presents the sites where the whalers settled, among others, at Red Bay in Labrador. The author explains the techniques and methods used by Basque whalers to catch and derive profit from these mammals. Lastly, it describes the everyday life of these courageous men who landed on the coasts as soon as the ice melted, and left when winter returned.

Basque Country

The sixteenth-century Basque whale hunt in the Strait of Belle Isle is one of the most engaging chapters in early Canadian history. The subject blends elements that have broad popular appeal: whales, large intelligent mammals hunted close to extinction; a period that is forgotten or, at least, ill-remembered; and the Basques themselves, a people often considered mysterious, given their non-Indo-European language and a suggested cultural affiliation with the original post-glacial peoples of Europe. For this reason, the Basque whale hunt has often been romanticized.

We need to be cautious about claiming that the Terra Nova hunt is long forgotten. In 1613, Champlain identified the Strait of Belle Isle as the location of the Basque whale hunt. Like many historical industries, it may well have slipped from popular memory, but, throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, it was an enduring part of the historical record. As for the supposed mystery of the Basques, in a way, the Basques became mysterious only with the rise of modern Spain and France, which left them ethnic others straddling two nation states. Even if they are, in this sense, mysterious, we cannot assume that they must have discovered the Americas long before Columbus. There is, in fact, no contemporary evidence for a pre-Columbus or pre-Cabot European presence, although claims were made in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries of Basque precedence in the New World. Experts in the documents of the period, however, insist that there is no convincing evidence that the Basques exploited the waters of Atlantic Canada before the early decades of the sixteenth century. One could also point to other early modern claims that Azorean sailors, Bristol fishermen or Breton navigators beat Columbus and Cabot to the New World. Finally, given the visibility of whaling stations, both literally and culturally, Basque whalers have earned a place in the popular imagination as the primary European presence in Atlantic Canada in the early sixteenth century, even though the early modern migratory cod fishery preceded it and was significantly larger.

On the other hand, the Basques were, from the outset, among the most effective, and certainly among the most persistent, cod fishers along the coasts of what is now Canada. They were pre-eminent early whalers and the only European whalers operating in our waters in the sixteenth century. The Basques also established close contact with Aboriginal Peoples early on.

The Basque Country straddles France and Spain, but only the three smallest provinces fell under French administration: Labourd, Basse-Navarre and Soule. The coastal provinces — Vizcaya and Guipúzcoa (in Spain), and Labourd (in France) — were the most active in both fishing and whaling. The key port of Bayonne, on the frontier between Labourd and Gascony to the north, played an important role in both industries, at least in certain periods, as did the smaller port of Saint-Jean-de-Luz.

The Late Medieval Basque Whale Hunt

The origins of the European whale hunt lie in the Mesolithic period, many millennia ago. By medieval times, whaling was important for Basque coastal towns, culturally as much as economically. This significance is suggested by the prominent place given whales and whaling in the town seals of the period. The sixteenth-century Basques recognized about eight species of whales. Their primary prey was the North Atlantic right whale, which they hunted in the Bay of Biscay. They called it sarda (schooling whale) because the whales could be found together in pods. The English name echoes whalers’ early preference for this species: it was the “right” whale to hunt because it was a slow swimmer and easily caught. In addition, unlike the humpback, minke and blue whale, the right whale floated when it was killed — a huge advantage in the centuries before the invention of winches and lines strong enough to haul the body of a dead whale from the depths. The Basques also hunted the grey whale, which they called otta sotta and which is now extinct in the Atlantic.

By early medieval times, the people of Labourd had developed their own whale-hunting custom. They spotted their quarry from stone lookout towers along the coast, called atalayas. The hunters then launched boats and pursued the whales. This early hunt seems to have been a corporate municipal effort, rather then a commercial one, and obtaining meat was probably as much of a goal as obtaining oil or baleen. The annual catch was probably 100 whales at most. So the sixteenth-century whale hunt in Atlantic Canada was a new kind of venture, even for the Basques, for it was the first commercial whale hunt. Although the French Basques of Labourd had been involved in whaling since medieval times, they had little part in the sixteenth-century transatlantic hunt, which was dominated by ships from San Sebastián and Pasaia in Guipúzcoa, and Spanish Basque merchants from further inland.

The Early Modern Market for Whale Oil

The Basques could not have developed a commercial whale hunt without markets. At the time, whale meat was still salted for consumption during Lent. (Conveniently enough, the whale was considered a fish for religious purposes.) Whale meat was not, however, exported in commercial quantities from Atlantic Canada to Europe. The main product shipped was oil, rendered from whale blubber. As a secondary product of the hunt, the Basques also collected the baleen from the mouths of the whales, which filter krill and other small marine creatures. Baleen consists of hard but flexible, and somewhat curved, plates (up to a metre or two in length) and could be used the way we might use fibreglass-reinforced plastic: for archer’s bows, buckles, helmets and so on. Whale oil was used primarily for lighting and lubrication, but sixteenth-century industries also used the oil in tanning, for finishing broadcloth and as an ingredient in soap. The Basque province of Navarre in Spain was an important producer of leather, so part of the market for whale oil was regional. Most of this product was shipped northwards, however, usually from San Sebastián, but sometimes from Bordeaux, or directly from Labrador to Nantes, Bristol, Amsterdam and so on.

Whaling as a Fall-Back Strategy

Although there is little documentation on early voyages to Atlantic Canada and the Gulf of St. Lawrence, historians have uncovered enough to be able to establish that the Basque transatlantic whale hunt emerged from the migratory cod fishery. Growth in the Basque cod fishery in la gran baya (the Grand Bay, the Gulf of St. Lawrence) is documented from the 1520s to the 1530s. In the 1530s, crews seem to have occasionally engaged in whaling as a kind of fall-back activity when the fishery was poor. Basque activities in Atlantic Canada expanded considerably after merchants began to mount separate specialized whaling and cod-fishing voyages in the late 1540s. Crews from the French Basque territory of Labourd were just beginning to participate in the migratory cod fishery in the 1540s and were not really involved in the Strait of Belle Isle whale hunt in the sixteenth century, although they did take up whaling further up the St. Lawrence, particularly in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Species of the Gulf of St. Lawrence and the Strait of Belle Isle

In the Strait of Belle Isle, the Basques hunted both the right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) and its close relative, the bowhead whale (Balaena mysticetus). They called the bowhead barba (bearded one) because it carries more baleen than the right whale. The bowhead is also larger. Zooarchaeological remains from the major whaling station at Red Bay, Labrador, indicate that bowheads and right whales each accounted for about half of the whales taken by the Basques there. The bowhead would be the major species exploited by the Basques and the Dutch at Spitzbergen in the seventeenth century. In 1622, when Thomas Edge described the northern whales frequenting Spitzbergen waters, he called the bowhead “the Grand Bay whale”, a name also used by the Basques: granbaiako balea. The bowhead is now an Arctic species, rarely reported in the western Atlantic, south of Hudson Bay. Right whales are rare as well, although they are reappearing today off the coast of Canada’s Atlantic provinces.

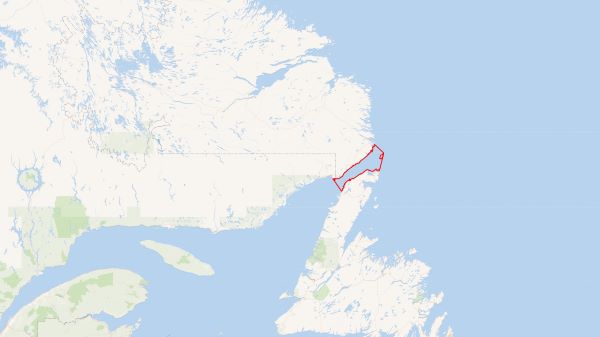

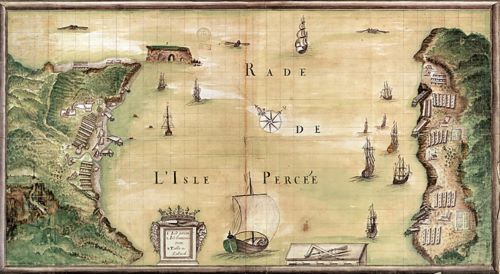

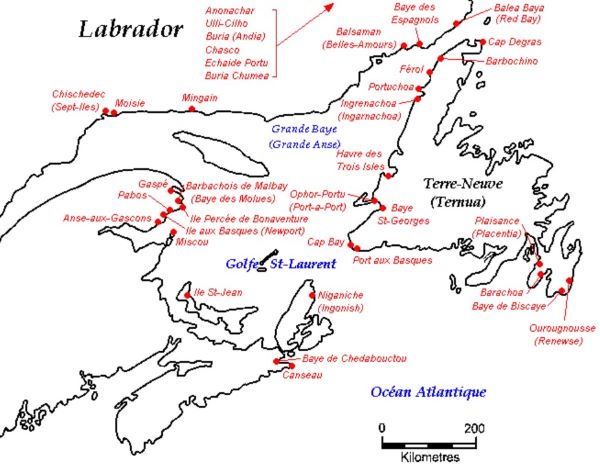

Shore Stations in the Strait and the Gulf: The Geography of Resource Exploitation

Like the dry salt-cod fishery, the early modern whale hunt was shore-based. The Basques set up rendering stations along the coast from which they launched whaling boats (chalupas) to chase their quarry. A commercial hunt in the Strait of Belle Isle is documented from about 1545. The Terra Nova industry peaked in the 1560s and 70s, when as many as twenty ships and 2,000 men crossed the Atlantic to the Grand Bay every summer. Whaling in the Strait had declined sharply by 1600 and had ended by 1620. Several factors may have contributed to this: a fall in the price of whale oil, naval conflict between Spain and England from around 1585 to 1605, impressment (forced recruitment) of mariners into Spain’s great Armada of 1588, inflation, taxation by the Spanish Crown, climate change, or a combination of these factors and a decline in regional whale populations.

Historians seem to resist the idea that the Terra Nova whale hunt had a serious impact on populations. This is perhaps a hasty conclusion. If about twenty ships a year were whaling at Labrador between 1560 and 1580 (based on the nineteen documented in 1572), and if each ship took fifteen to twenty whales, then the Basques were capturing about 300 to 400 whales a year, for twenty years. This suggests the elimination of 6,000 to 8,000 individuals. When the whales taken before 1560 and after 1580 are taken into account, as well as those that died of harpoon injuries without being captured and processed, there must have been a serious impact on the populations of slowly-reproducing right and bowhead whales, which grazed off Labrador before the arrival of the Basques. The zooarchaeological perspective suggests an alternative interpretation. According to recent estimates, there were about 11,000 bowhead whales and about 12,000 to 15,000 right whales in the western North Atlantic in pre-contact times (before 1540). The same study suggests a total catch of 25,000 to 40,000 whales between 1530 and 1610 — a considerably bleaker picture. There is even evidence of reduced populations as early as the 1570s.

After the decline of the whaling industry in the Strait of Belle Isle, around 1600, the Basques continued to hunt whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where they pursued other species as well, in particular the smaller beluga whale. The French Basques of Labourd set up an important whaling station on the St. Lawrence, at Île aux Basques, near Trois-Pistoles, Quebec, across from Tadoussac. Archaeological evidence suggests that the station was operational for half a century, between about 1585 and 1635. By the 1660s, it had been abandoned. From 1540 to 1640, the Basques also set up shore stations at many other locations on the north shore of the St. Lawrence: Chauffaud-aux-Basques, Les Escoumins, Sept-Îles and the Mingan Islands, near Anticosti Island, where a whaling station was in operation in the second half of the seventeenth century.

There seems to have been a second wave of Basque whaling activity in the Gulf between about 1735 and 1755, at Bon-Désir, near the mouth of the Saguenay, in the Mingan Islands and at Sept-Îles. A site has recently been identified at Little Mecatina, near Harrington Harbour, Quebec. A multi-component site, it was also used in the shore-based fishery, and possibly by other ethnic groups as well. Many of the processing sites in the Gulf of St. Lawrence interpreted as whaling stations may in fact be later sealing stations. The Basques were also involved in sealing, in the Madeleine Islands in the 1660s, for example. Their exploitation of the islands’ resources dates back to the sixteenth century, when they and the Bretons hunted walruses there — so effectively that the species no longer exists in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

The Red Bay Site

The Basques chose their whaling stations carefully. They preferred deepwater harbours protected by an island — key features of the important station on Saddle Island, in Red Bay, Labrador. That lonely outport was identified as the place the Basques called Buytres or Butus, by far their most important Labrador shore station in the second half of the sixteenth century. Every summer and fall, thirty to fifty whaling boats, associated with eight to ten ships, would operate from that large station. These figures imply a seasonal population of 500 to 1,000 Basques, plus an unknown number of Innu (Montagnais) attracted by opportunities for trade.

Red Bay became, by far, the best-researched Basque whaling station in Canada. The archaeology of the site is the main basis for the material culture interpretation presented here, although there are also excellent documentary sources and archaeological findings from excavations at Chateau Bay, Labrador; and at Île aux Basques and the Mingan Islands, Quebec. At Red Bay, crews from Memorial University have excavated rendering ovens, a cooper’s shop, several small dwellings and even an extensive Basque cemetery. Just off Saddle Island and, strangely enough, close to the still-visible wreck of the Bernier, a modern coastal freighter, lies the wreck of a sixteenth-century cargo ship. It is more likely than not the wreck of the San Juan of Pasaia, Spain, reportedly blown aground in Red Bay with a cargo of oil in 1565. This cannot be confirmed because there are at least three other early wrecks of about the same size in Red Bay harbour, not to mention some important small-boat finds, including several whalers’ chalupas. However, the evidence assembled points to the San Juan. Documents retrieved from Spanish and French archives, together with the archaeological excavation of the site on Saddle Island, the wreck of the San Juan and a chalupa, make it possible to reconstruct much of the early Basque whaling industry.

The Annual Round

Each spring, the merchants of the Basque Country organized expeditions. They hired a captain to assemble a crew and provisioned a vessel, often in Bordeaux. Some ships engaged in the whale hunt and others in the salt-cod fishery. The Strait of Belle Isle was often blocked with sea ice into late spring, so there was not much point in setting sail for the Grand Bay until May or even June. It is not known how crews claimed shore stations in the migratory whale hunt. The first-come, first-served admiral system, prevalent in the cod fishery, may not have applied to the whale hunt. Whaling infrastructure was more expensive and more durable than that of the shore-based fishery, so it is possible that well-armed whaling crews would insist on their right to re-occupy the slipways and ovens they had constructed in previous years.

The whaling season often extended well into the fall, much longer than the cod fishery, which normally wrapped up in late August. This extended season, dictated by the migration of the bowhead and right whales, which were found in the waters off southern Labrador from early summer through late fall, sometimes left whalers with no choice but to overwinter in Canada. When whale stocks declined later in the sixteenth century, crews were sometimes forced to overwinter because they stayed too long on the coast and found themselves trapped by ice while trying to produce a decent cargo of oil. In 1574–1575 and 1576–1577, several ships were forced to overwinter, with disastrous results for the crews. On the other hand, overwintering could also follow a particularly productive season, when the ship was full of oil and the captain offered a bonus to the men who stayed behind, to free up cargo space. As a general rule, though, ships and crews returned together in late fall to San Sebastián or Bordeaux, where they offloaded their casks of oil and parted ways. The men spent a few months at home with their families before the whole annual cycle recommenced. This was the traditional seasonal pattern in the Basque Country, as in some other pastoral regions in Europe.

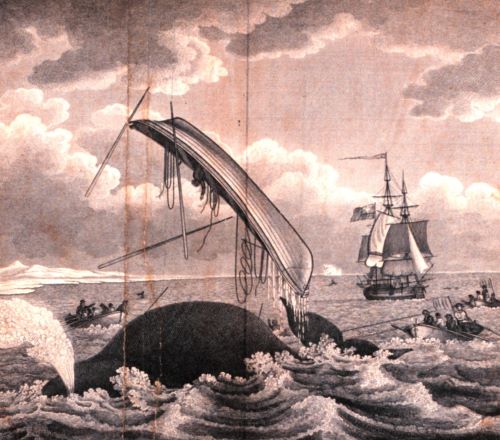

The Hunt and the Chalupa

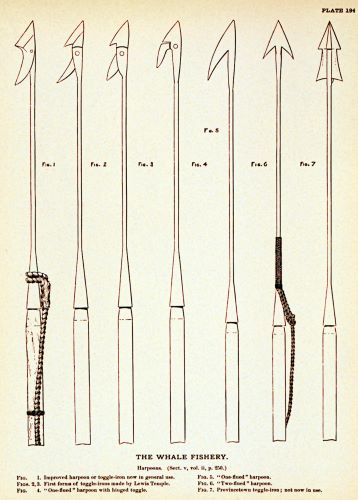

No atalaya towers have survived in Labrador, but archaeologists have found evidence of a small tile-roofed lookout structure on a high ridge on Saddle Island, at the Red Bay whaling station. Once a whale was spotted, the whalers launched their chalupas and pursued their quarry until a harpooner in one of the boats could strike it. In the traditional Bay of Biscay hunt, the crew then pursued the injured whale. Later whalers attached the harpoon to the boat with a line, so that the whale towed the boat and crew on a “Nantucket sleigh ride”. Champlain’s (1613) account of the Basque hunt mentions this technique, which was also employed at Labrador in the sixteenth century. However, there is no evidence of bollards on the chalupas excavated at Red Bay. Such posts, fixed to the keel, were needed to pay out the line safely as the animal tried to escape. Therefore, in the sixteenth-century Terra Nova hunt, the Basques may have used the older system of attaching a wooden buoy to the harpoon with a short line, so that the injured whale would drag the marker behind it as it fled.

No matter what system was used in the sixteenth-century Terra Nova hunt, the harpoon was only the first strike; the crew had to pursue the whale and kill it with lances when it surfaced to breathe. The harpoon was a heavy V-shaped iron point, much like the barbless points still in use in the eighteenth century. Harpoon heads and harpoon shafts, or irons, were procured separately, and a crew might have five heads per shaft. Crews also needed long and short lances, as well as gaffs and lines to manoeuvre the carcass once the whale was dead. This equipment did not evolve significantly for several centuries.

Chalupas (shallops, chaloupes) were oar-powered whaling skiffs that carried a lugsail. Each one was manned by a harpooner, a steersman and four to six oarsmen. The Basque chalupa was the prototype for later whaling skiffs, from New England to the Azores, and the well-preserved example excavated at Red Bay suggests that the modern form essentially already existed in the sixteenth century. It is about 8 m long and 2 m wide, which was typical. These skiffs were strongly built, primarily of oak with wrought-iron fastenings. They had a deeply rockered (curved) keel for manoeuvrability, carvel (smooth) construction below the waterline for speed, and lapstrake (overlapping) construction above to maximize flexibility and resist tipping. The Red Bay example is, by far, the best-preserved chalupa used by early modern Europeans in Atlantic Canada. The inshore boats used in the French dry salt-cod fishery were very similar, but their lines might not have been so fine. In the fishery, carrying capacity was more important than speed.

Flensing the Whale

The boat crew towed the dead whale back to the shore station for processing, under sail if possible, hence the importance of capturing a whale that floated. Whales may have been flensed afloat or ashore, or perhaps alongside a ship, close to the shore. It would seem most efficient to use the tides and a winch or capstan to bring the whole carcass onto a slipway and flense it there. This was the system used later at Spitzbergen, where the remains of winches have survived. The Grand Bay whalers sometimes flensed whales at sea, but faunal debris recovered just offshore at Red Bay suggests that they often brought the whale inshore for cutting-in, as described by Champlain.

A Basque wharf was discovered at Red Bay. Framed with mortised logs, it was used at some stage of the flensing operation, either for landing and stripping the whole carcass or for slicing up large chunks of blubber. One of the main frame timbers has a mortise for a missing vertical timber, which might have been part of a crane. Excavations also uncovered a paved stone walkway connecting the wharf and the tryworks area, where the chunks of blubber were actually rendered into oil.

Rendering Blubber: The Tryworks

No accurate descriptions of Terra Nova tryworks have survived, but William Burroughs (1576) suggested that four “furnaces” (cauldrons) were needed, “to melt the whale in” for a crew of 55 men with five boats on a 200-ton ship. He added that the men would need “6 ladles of copper”. The trying process consisted of heating minced blubber in open copper cauldrons over a slow fire. The workers used the copper ladles to skim fritters (fenks) from the oil and recycle them as fuel for the tryworks. Each hornos (oven) consisted of roughly rectangular stone walls, about 50 cm thick, surrounding a circular firebox about 1.2 to 1.5 m in diameter. The ovens were often arranged in rows of four or more, like row houses sharing walls between adjacent units. Such ovens have been recorded at several sites, in particular Île aux Basques and the Mingan Islands, Quebec; and Chateau Bay and Cape St. Charles, Labrador. In each oven sat an open copper cauldron. These were likely shallow and not quite hemispheric, also about 1.2 to 1.5 m across with a concave rim. Cauldrons sometimes burst, judging by the remains at Red Bay. Damage to the stone oven walls, from such accidents or from regular use, led to deterioration, and crews often had to rebuild their ovens. A wooden working platform surrounded the stone ovens, and a timber structure roofed with distinctive red clay tiles possibly imported from the Basque Country protected the whole tryworks.

Storage of Whale Oil: The Barrica

After hunting, flensing and trying, the storage and shipment of whale oil was the fourth, and final, step in the sixteenth-century Grand Bay production process. The Basques used a standard shipping container called a barrica, a wooden staved barrel with a capacity of about 200 to 230 litres, about the same as a modern oil drum. The whalers usually shipped barricas to Terra Nova in pieces. Provisioning lists call for about 150 barrels for each boat crew. Since the barrels had to be assembled, and repaired when handled roughly, each shore station needed several coopers. Coopers were recognized as important specialists on whaling voyages and got bonuses for their work. Excavations at Red Bay suggest that these skilled artisans actually lived in the cooperage and enjoyed certain amenities, such as decorated ceramics, not expected by most of the crew. The barrel staves were marked to facilitate reassembly, and the barrels themselves were sometimes identified by the owner’s monogram. The oak used for the staves was imported to the Basque Country from Brittany, which gives an indication of the integration already achieved in the early modern transport zone centred on the Bay of Biscay.

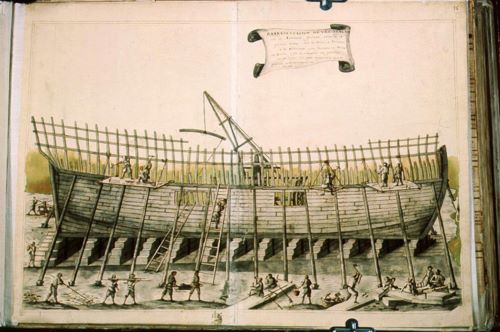

Transatlantic Commerce: The Ships

Whether or not the sixteenth-century wreck excavated in Red Bay is the San Juan, lost in 1565, or a similar ship lost around the same time under similar circumstances, the find represents an excellent example of a transatlantic workhorse of the period. Ships were not specialized by trade; a ship might be sent to the salt-cod fishery one year and on a whaling expedition the next. So the vessel found at Red Bay tells us about transatlantic technology at the time and not just about the whaling industry.

The labels put on the types of ships are notoriously flexible, evolving over time, as did the ships themselves. The San Juan was a nao of 250 tons or so. The Spanish word nao meant ship. The nao evolved from northern European designs, as opposed to the galéon, which was closer to the early-sixteenth-century caravel, a Portuguese design. The sixteenth-century Basque galéon was actually smaller than a nao, which, at 200 or 300 tons, was just the right size to send to the dry salt-cod fishery or for a cargo of whale oil. Ships were built in England, northern France and the Basque Country using somewhat different layout and measurement systems. At the same time, technical and stylistic details evolved. The San Juan is of a transitional design, harking back to earlier traditions (for example, with its complex one-piece keel) and prefiguring later developments (for example, in standardization of design). In the sixteenth century, the nao typically had a beam / keel / overall length ratio of 1:2:3. It was replaced in the seventeenth century by similar ships with sleeker lines, the ratio being more like 2:5:7.

Taking a broader view of the early modern period, the three-masted ship, the typical vessel of transatlantic commerce from its inception around 1500, can be considered one of the great technical inventions of European history. As the analysis of the San Juan has shown, the design of three-masted ships evolved from the sixteenth century to the end of the eighteenth century, when this type of ship was replaced by schooners and similar vessels equipped with fore and aft rigging, rather than square sails. A few wrecks of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century three-masted ships have survived in Atlantic Canada and along the shores of the St. Lawrence, but, unlike the San Juan, none has preserved the details of construction and use. The Red Bay wreck is, of course, a ship of its own particular time and place, but it can also help us imagine maritime life in the Atlantic world over the course of several centuries.

Did the Basque Have Technical or Cultural Advantages?

Basque activity in the Grand Bay raises questions that go beyond the discussion of everyday life. Some observers, including Nicolas Denys, thought the Basques had earned a certain pre-eminence in the maritime world, in part because of their technical expertise. What follows, therefore, is as much a discussion on certain aspects of the daily life of Basque mariners in the Gulf of St. Lawrence as a discussion on Basque whalers.

Nicolas Denys, a contemporary observer of the Basques, was unambiguous about them. They were the most productive fishers, he thought, because of their economic culture and certain technical advantages. He contrasted them with crews from other regions, who were all too prone to goof off (courir le marigot):

courir le marigot is when the fishermen go and hide in some little cove of the shore, or under the lee of rocks, instead of going upon the fishing grounds; something which happens only too often. There they make a fire for roasting Mackerel, and make good cheer. Then they sleep until one or two hours after noon, when they awake and go upon the grounds. There they take what they can, a hundred or a hundred and fifty Cod, and return to the staging like the others, fearful of being scolded. They are the first to grumble, alleging their bad luck …

Denys 1908: 323

On the other hand:

It is in this respect the Basques have an advantage. Possessing good garments of skins, they go rarely to the marigot and are little slothful. At evening they come to the stagings and have their boats loaded, while the other fishermen have not half as much. Also the latter call the former all sorcerers, and say that they play the cap [joüer la Barrette]; the latter is a cap which they wear upon the head, and which they turn repeatedly when they are angry. All these reproaches are founded only upon the hate which all the fishermen bear towards them, because they are more skilled at the fishery than all the other nations.

Denys 1908: 323–324

One would give little credence to this kind of generalization if it came from someone who looked good in comparison, but Nicolas Denys was not Basque. He was from La Rochelle, so he had no particular reason to flatter the Basques, other than his long experience in the fishery.

The idea that the Basques worked within a distinctive economic culture and with some technical advantages is not implausible. They may have deferred to the Bretons in navigational knowledge of Terra Nova in the 1520s and 30s, but by the time Martin Hoyarsabal published the first rutter (handbook of navigational information) for the waters of Atlantic Canada, in 1579, they had clearly developed great expertise. The navigational aids found on the San Juan, including a binnacle, a compass, a sandglass and one of the earliest log lines known (for estimating speed through the water) attest to this sophistication. The Basques had clearly developed a vernacular whaling technology that other ethnic groups could not even imitate in the sixteenth century. When others began to catch up, in the early seventeenth century, they were very much dependent on Basque whaling expertise.

The chalupa was not the only element of Basque whaling technology passed on to later whalers. Sixteenth-century Basque Terra Nova whaling technology was, in fact, the direct ancestor of subsequent European whaling technologies. The next major whaling industry developed on the Arctic island of Spitzbergen, in northern Scandinavia. The Basques began to send expeditions to the area in the 1580s, when the Grand Bay whale hunt declined. The English vied with the Dutch in developing shore-based whaling stations there as well, the Dutch prevailing in the 1620s, although the Basques continued to send whaling expeditions to the north until 1688. Both northern nations sought and employed Basque expertise in developing their industry. The Dutch in turn developed whaling technology and passed their knowledge on to American colonists in New Amsterdam and southern New England. The Americans passed their adaptation of the technology on to the Azoreans they employed as crews, and so on. Whaling and sealing techniques used in Canada in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries may likewise have been learned from Basque mariners. Denis Riverin, seigneur of Matane, actually hired harpooners in Bayonne in 1690 to teach the basics of whaling to Canadian fishermen. Whether or not this effort was successful, it is clear that the contribution of the Basques to the settlement of New France lay in the maritime world.

The Socio-Economic Structure of Basque Whaling Crews

Each Basque whaling crew consisted of oficiales (officers and tradesmen), ordinary seamen, and boys apprenticed either as seamen or oficiales. The captain made verbal agreements with his crew, hiring about 25 men per 100 tons of vessel, so perhaps 60 men for a 250-ton ship. The captain normally invested in the whaling tools himself, but coopers and carpenters had to supply their own tools. Even a small crew included a boatswain, a boatswain’s mate, a steward (purser), a cooper, a caulker, a gunner, harpooners, flensers and boys. Chaplains and pilots might serve several ships on a single expedition. Larger ships might carry their own, as well as a surgeon, and even a diver to make hull repairs. At sea, the division of labour differed slightly from that on land, since coopers and harpooners served only as sailors at sea.

Whaling expeditions could produce very large returns; the cost of the ship might be recovered in a single voyage. As a result, arrangements for sharing the profits had to be explicit. On Spanish Basque whaling voyages, one-third of the profits from the cargo usually went to the crew, one-quarter to the ship’s owners and the remainder to the outfitter, with various bonuses paid in oil or baleen to particular oficiales. Individual crewmen’s shares varied widely. Harpooners had very large shares, inferior only to those of the captain or pilot. A chief harpooner or pilot might get four times as much as an experienced ordinary seaman; a gunner, surgeon, cooper or flenser, twice as much; while ship’s boys had to be content with a quarter of a seaman’s share. Crews were paid exclusively on the basis of the success of the voyage, which may be why the issue of courir le marigot was not a problem in the Terra Nova whale hunt. Another factor keeping whalers at work when they needed to be may have been that the pace of the hunt offered more time off than the cod fishery. The object of the hunt was larger, creating a lot of work when a whale was captured, but also implying periods of waiting watchfully. Cod, on the other hand, were normally taken hand-over-fist, and crews were expected to work long days throughout a short season.

A well-organized apprenticeship system made inegalitarian share distribution acceptable to ordinary mariners and apprentices, as well as ensuring that the various complex traditional whaling skills were passed on from generation to generation. Apprentices and ship’s boys were often sons or nephews of sailors and tradesmen. They might be as young as eleven or twelve years old. Attrition among boat crews, who took great risks, would have made advancement within this specialty relatively rapid, but all Basque whalers could advance through the ranks, with experience.

Contact with Aboriginal Peoples

European crews interacted with Aboriginal peoples from the earliest days of the transatlantic industries in Atlantic Canada. Significant Basque participation in the cod fishery, in the 1540s, followed Breton and Norman commitment to the industry by a decade or two, so it is not surprising that the Normans preceded the Basques in the beginnings of a fur trade with Aboriginal peoples in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Yet, in the second half of the sixteenth century, the Basques became the pre-eminent European traders in the region. Basque crews are known to have traded with the Beothuk of Newfoundland, the Innu (Montagnais) of Labrador and the St. Lawrence North Shore, and the Mi’kmaq of Gaspé, Chaleur Bay and Cape Breton. Sometimes, they also employed Innu workers at their whaling stations in the Strait of Belle Isle. The Basque fur trade peaked in the late 1580s and culminated in the establishment of a Basque trading post at Tadoussac at the end of the century. Unfortunately for Basque merchants, they were forced out of the Canada trade after 1600. Their exclusion became official in 1645, when migratory fishers lost the right to trade for furs with Aboriginal peoples in New France. Only companies to which the king of France had granted a monopoly could engage in such trade.

Between 1560 and 1600, or even a bit later, the Basques dominated trade with the Aboriginal peoples of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. This dominance is reflected in the widespread archaeological survival of distinctive Basque trade goods, including axes and copper kettles, which found their way inland, far into the Iroquoian and Huron territories in what is now Ontario. Another indication of close Basque interaction with Aboriginal peoples was the development, in the sixteenth century, of a pidgin trade language that left traces of Basque in the vocabulary of some Aboriginal languages in the region. Did the Basques have some special interest or ability in dealing with Aboriginal peoples? This is not far-fetched, keeping in mind that they are themselves an ethnic isolate, surrounded by peoples of another language family. The Basques were already used to dealing with people who spoke another tongue, incomprehensible at first, and with the complex arrangements that might permit strangers to engage in mutually profitable trade. This experience cannot have hurt them when they met Canada’s First Nations. Perhaps this cultural skill can be added to the technical and economic skills that so impressed Nicolas Denys.

Risk and Mortality: “There is much to be gained, and great peril”

Whaling was physically risky. The great danger was the overturning of boats as the whale thrashed its tail after the harpoon struck. When lines were employed, crews also risked being ensnared and pulled overboard, or even going down with a boat pulled under by a sounding whale. Regular accidents are suggested by Thomas Edge’s (1622: 22) insistence that “swimming [was] also requisite for a Whale-killer to be expert in” and by the fact that the Basques always pursued whales with at least two chalupas. Disasters were vividly imagined in an early-seventeenth-century prayer written in Basque by Joanes Etcheberri in 1627 and offered after the whale was struck but before it died:

Lord, it is by your grace, more so than because of our skill, that we harpooned the whale and wounded it. Therefore, All-Powerful Lord, help us immobilize the great fish of the sea quickly. Without injuring any of us when it is caught with a rope around its tail or its chest, because it is strong, without the boat keeling over, without it being dragged with the whale to the bottom of the sea. Spare us all these ills, so that we may give you thanks once we are back upon the shore. There is much to be gained, and great peril: watch over us and preserve us from harm … (Etcheberri 1627, translation).

There were other risks. One was associated with the trying ovens. The numerous copper cauldron fragments recovered from fireboxes indicate that these vessels sometimes burst, spilling hot fat into an even hotter fire. The flames from such a spill would have been a grave risk to renderers and mincers working nearby. The major disease risk for whalers, as for fishers, was probably scurvy, caused by a deficiency of vitamin C. Later on, mariners began taking scurvy remedies with them on their voyages. By 1600, visitors to the New World had learned, perhaps from Aboriginal peoples, that a decoction of the needles of eastern white cedar or fir had such properties. Another general risk was being stranded in Labrador if ice blocked the coast.

In Terra Nova, death was, as the saying goes, part of life. With several hundred men engaged in a dangerous industry, the Basque whalers at each station would expect a few of their companions to die each season. Excavations in the cemetery at Red Bay uncovered roughly 150 skeletons, which suggests a minimum average mortality of three men a year. Those facing death conceptualize it in various ways. The whalers’ prayer noted above was not the only one recited; there were others. The dying could also give legal expression to their wishes. The earliest surviving will written in what is now Canada was penned on Christmas Eve 1584 in Carrolls Cove, Labrador, by the barber-surgeon of a Basque whaling crew. Joanes de Echaniz, who was from the town of Orio, in Guipúzcoa, left small donations to various churches and asked for masses to be said for his soul and for the dead. He left most of his estate to his daughter and asked to be buried in the family’s tomb, as well as for the “offices and obsequies” and “other usual offerings for people of [his] rank”. These rituals, he begged, should be performed even if he died in a place from which his body could not be transported.

The men who died in Labrador were usually buried there. Most of the burials at Red Bay are within one contiguous cemetery area. Most people were laid on their backs, in an extended position with their heads to the east, facing Jerusalem, although there were exceptions. Excavators uncovered both single and multiple burials. Some burials were marked with rows of two or three boulders. Since priests accompanied crews to Terra Nova, we can be sure that traditional funeral ceremonies would have been performed. One burial might even be that of a priest; the body bore a large wooden-cross pendant. Priests may have participated in the Labrador voyage not only to guide the souls, and perform last rites and burial ceremonies, but also for the observance of religious rituals considered good luck for a safe and successful hunt. As was the case among early modern fishing crews, deep religious customs permeated both life and death.

Fisheries

Long before the fur trade, there was seasonal fishing. From the very early 16th century, men from Normandy, Brittany and even from the Basque country sailed the shores of Newfoundland to fish cod and hunt whale. Around 1550, some 500 ships set sail from France to seek these waters teeming with fish.

Peter Pope recalls the different phases in the history of fishing in New France. Beginning with the first expeditions, he describes the establishment of Basque and Breton fishing communities along the western and northern coast of Newfoundland, and on the Saint Pierre and Miquelon archipelago. Together these communities formed the royal colony of Plaisance.

After presenting the plentiful fisheries resources in North America, the author describes various fishing sites, the strategies used to catch cod and the methods of preserving it. Fishing was a very active sector of the economy in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries because of the liturgical calendar of the Catholic Church, which required numerous fast days on which the eating of meat, but not fish, was forbidden. On signing the Treaty of Paris in 1763, France retained fishing zones in the region.

Fur Trade

Overview

It is difficult to overstate the importance of fur in the historical development of New France. Indeed, it was the lure of this resource that prompted the French to establish a permanent presence in the St. Lawrence River Valley in the early seventeenth century, and subsequently to expand into the Great Lakes region, the Mississippi, Ohio, and Illinois River Valleys, and the Hudson Bay watershed. Over this vast tract of the North American continent, the French engaged in an ambitious commercial enterprise designed to meet European demand for fur. This enterprise – known by the deceptively simple term “the fur trade” – had complex economic, social, and political dimensions and shaped the French colonial experience in diverse ways. Although its annual value paled in comparison to that of the North Atlantic cod fisheries, the fur trade was nevertheless the economic engine of New France: it underwrote exploration, evangelization, and settlement initiatives while providing income for habitant households and generating private fortunes for officials, merchants, and investors. Additionally, the fur trade shaped patterns of mobility and settlement in New France through its requirements of an itinerant labour force and inland trading posts. Some of these posts – like those at Quebec, Detroit, and Green Bay – became the nuclei of permanent population centres.

Most critically, the fur trade drew the French into close and constant proximity to Aboriginal peoples. Lacking sufficient manpower and resources to conduct the trade alone, the French depended on Aboriginal peoples for the harvesting, processing, and transportation of furs, and also for their services as guides and intermediaries. Securing these services required the French to forge alliances with several First Nations, including the Montagnais, the Algonquins, and the Hurons in the first half of the seventeenth century, and the Saulteaux, the Potawatomis, and the Choctaws in the second. These alliances ensured that the French became deeply enmeshed in Aboriginal economies, societies, and politics, while simultaneously drawing Aboriginal peoples into a European sphere of influence. Thus, the fur trade entailed far more than a simple exchange of commodities: it fostered the interchange of knowledge, technology, and material culture; it underpinned powerful military coalitions; and it gave rise to new cultural forms and identities. In the interest of maintaining these complex and often lucrative interactions, the French developed attitudes and policies toward Aboriginal peoples that differed markedly from those of English-speaking settlers on the Atlantic seaboard.

Aboriginal Trade

By the early seventeenth century, Aboriginal peoples had developed a sophisticated and dynamic system of trade. They conducted this trade through networks that criss-crossed North America from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic. Composed of waterways, portages, and overland trails, these networks conveyed such diverse trade goods as seashells from the east coast, copper from the shores of Lake Superior and the Coppermine River, obsidian glass from various locations in the west, and tobacco from south of the Great Lakes, as well as dried foods, fishing nets, and pelts from across the continent. The extensiveness and efficiency of these networks ensured that European-made goods filtered into the interior long before European traders ventured inland from the Atlantic shore. For instance, archaeologists have unearthed European silverware, brass ornaments, and Delft pottery dating from the mid-sixteenth century in the homeland of the Seneca people – south of Lake Ontario and hundreds of kilometres west of the Atlantic Ocean.

In 1636, Jesuit missionary Jean de Brébeuf described some of the rules governing the operation of trade networks among the Hurons:

Besides having some kind of Laws maintained among themselves, there is also a certain order established as regards foreign Nations. And first, concerning commerce; several families have their own private trades, and he is considered Master of one line of trade who was the first to discover it. The children share the rights of their parents in this respect, as do those who bear the same name; no one goes into it without permission, which is given only in consideration of presents; he associates with him as many or as few as he wishes. If he has a good supply of merchandise, it is to his advantage to divide it with few companions, for thus he secures all that he desires, in the Country; it is in this that most of their riches consist. But if any one should be bold enough to engage in a trade without permission from him who is Master, he may do a good business in secret and concealment; but, if he is surprised by the way, he will not be better treated than a thief,—he will only carry back his body to his house, or else he must be well accompanied. If he returns with his baggage safe, there will be some complaint about it, but no further prosecution.

Jean de Brébeuf, “On the Polity of the Hurons, and their Government,” in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791, ed. Reuben Gold Thwaites (Cleveland: Burrows Bros. Co., 1896-1901), 10: pp. 223-225.

While possessing the infrastructural capacity to engage in large-scale trade with Europeans, Aboriginal peoples did not necessarily share European attitudes or approaches to trade. In contrast to the European proclivity toward the accumulation of personal wealth, Aboriginal peoples tended to acquire goods for the purpose of redistribution. Among the Hurons, for example, an individual collected goods in preparation for institutionalized gift-giving ceremonies – such as those accompanying marriages, burials, and name-giving ceremonies. These occasions enabled him to enhance his social status through displays of generosity and selflessness. Whatever gifts he received on these occasions, he shared with his immediate and extended kin. Beyond the local level, gifts served a critical diplomatic function as they cemented and reaffirmed alliances between the Hurons and their Algonquian-speaking neighbours – including the Algonquins, the Ottawas, and the Nipissing. Gifts were presented whenever members of these groups encountered, whether in crossing each other’s territories or in coming together to negotiate, to celebrate, or to wage war against a common enemy. Thus, gift-giving was a social and diplomatic obligation, and trade provided a means of acquiring the goods needed to fulfill this obligation.

The European Market

The late sixteenth century witnessed the beginning of a dramatic growth in European demand for furs. Driving this demand were the vagaries of fashion: fur and fur-trimmed clothing were increasingly sought after as expressions of status, wealth, and style. By the early 1600s, one item in particular had emerged as a staple of the fashionable man’s wardrobe – the broad-brimmed felt hat. Various kinds of animal pelts were used in the production of this headwear, but the highest quality and most expensive hats were made entirely of beaver fur. Through a specialized felting process, beaver fur yielded a fabric that was unrivalled for its softness, malleability, and water resistance, and that was therefore perfectly suited to hatmaking. Unfortunately, surging demand for this fabric contributed to the over-hunting and over-trapping of the European beaver (Castor fiber), such that the species was reduced to near extinction during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

The depletion of European beaver stocks spurred the development of a European market for the fur of the North American beaver (Castor canadensis). Like its imperilled European cousin, the North American beaver had evolved in a harsh winter climate and consequently bore a thick coat that was ideal for feltmaking and hatmaking. This coat had two layers – an outer layer consisting of long, smooth, and stiff guard hairs, and an inner layer consisting of short, soft, and fluffy underfur. It was the underfur that captured the interest of European traders, as each of its strands was barbed and could therefore be linked with other strands to form a solid piece of felt. This could only be done, however, after the underfur had been separated from the guard hairs through one of two methods, both of which involved processing by Aboriginal peoples. The first method produced the so-called greasy beaver pelt, or castor gras – a pelt that had been sewn into a garment and worn in direct contact with an Aboriginal person’s skin. After several months of continuous abrasion and exposure to human sweat, oils, and body heat, the guard hairs had loosened and fallen out of the pelt leaving only the underfur. The second method produced the so-called parchment beaver pelt, or castor sec – a pelt that had been sun-dried immediately after having been harvested. Removing the guard hairs from this type of pelt required specialized treatment from feltmakers in Europe.

After shipment across the Atlantic Ocean, castors gras and castors secs underwent a complex process that had developed over centuries of experimentation and refinement. Feltmaking took place in a number of workshops in Europe, but by the early eighteenth century, the finest and most fashionable felts were being produced by a handful of large establishments in Paris, Lyons, and Marseilles. The process occurred in two stages: first, the underfur was separated from the guard hairs and the skin; then, the barb on each strand of underfur was raised and linked to other strands through a variety of techniques – including exposure to water, heat, and friction. Castors gras were comparatively easy to process, as the guard hairs had already been removed from these pelts by the time they reached European feltmakers. In contrast, castors secs required an intensive combing treatment in order to separate the underfur from the guard hairs. This treatment was refined in the 1720s by the development of a technique known as “carroting” – “secrétage” in French – in which castors secs were brushed with mercury salts diluted in nitric acid. Although this technique increased the speed and efficiency of the separation process, it took a terrible toll on the health of feltmakers and hatmakers. Many developed serious neurological damage as a consequence of prolonged exposure to mercury – a fate that may have given rise to the English expression “mad as a hatter”.

In the interests of securing a regular supply of these pelts and those of other animals, France laid the foundations of a permanent colonial presence in North America in the early seventeenth century. By then, the French had whet their appetite for New World furs thanks to the seasonal trading activities of Basque whalers and French fishermen in the Gulf of St. Lawrence throughout the 1500s. This seasonal trade had become increasingly profitable and competitive over the course of the century, such that French merchants had begun sending ships to the region for the sole purpose of procuring furs by the 1580s. In an effort to control the burgeoning trade, the French Crown granted monopoly rights to a succession of merchant companies. Tenure of a monopoly required that a company commit itself to promoting French settlement in North America and also to sponsoring Roman Catholic missionary activity among Aboriginal peoples. It was under these terms that merchant companies established the first permanent French settlements along the St. Lawrence River – Tadoussac in 1600, Quebec in 1608, and Trois-Rivières in 1634. Yet the French were not the only Europeans to be drawn permanently to North America by the lure of furs: Dutch merchant companies were establishing year-round settlements along the Hudson River during the same period – first at present-day Albany in 1614 and then downstream on Manhattan Island in 1625-26. The locations of these settlements reflected the commercial interests of their French and Dutch founders. Each settlement was situated at the outlet of a pre-existing trade network that stretched deep into the fur-rich interior of the continent.

Plugging into Trade Networks, 1600-1660

By establishing settlements along the St. Lawrence River, the French inserted themselves into networks that conveyed trade goods – including pelts – over vast distances. At Tadoussac, they plugged into a network that stretched northwestward along the Saguenay River and through hundreds of kilometres of boreal forest to James Bay. At Quebec and Trois-Rivières, they plugged into networks that stretched westward to the Great Lakes and northwestward along the St. Maurice and Ottawa Rivers. Each of these outlets was situated in the territory of a particular Aboriginal group that controlled the flow of goods into and out of the St. Lawrence River – the Montagnais at Tadoussac, the Algonquins at Quebec, and the Atikamekw north of Trois-Rivières. As a rule, these groups traded only with close political and military allies. Thus, in order to gain access to the pelts that moved through the networks, the French were compelled to negotiate a series of strategic alliances with the Aboriginal peoples of the St. Lawrence River Valley. Much of the diplomatic groundwork was laid by Samuel de Champlain, who forged and consummated alliances with the Montagnais and the Algonquins by joining war parties against their longstanding enemy – the Five Nations of the Iroquois League – in 1609 and 1610.

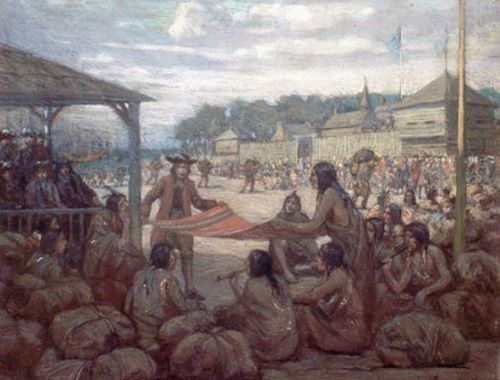

From their toeholds at the outlets of these networks, the French conducted trade through Aboriginal intermediaries – or middlemen – who gathered pelts from inland hunters, trappers, and processors, and then carried them by water and land routes to nascent French settlements on the St. Lawrence River. Foremost among these intermediaries were the Hurons – an Iroquoian-speaking people practising agriculture on the southern shore of Georgian Bay. After establishing an alliance with Champlain in 1615-16, the Hurons developed a vast carrying trade between the French and a host of Aboriginal peoples along the north shore of the St. Lawrence River and in the Great Lakes region. Between 1615 and 1649, the Hurons hauled French trade goods into the western interior and sent flotillas laden with furs downriver to Quebec and later to Trois-Rivières. These two settlements were subsequently eclipsed by Montreal as the destination for Aboriginal trade flotillas. Although founded as a religious enterprise in 1642, Montreal quickly emerged as the centre of New France’s fur trade because of its strategic location at the confluence of the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers. Every summer in the 1650s and 60s, the settlement held a trade fair that drew large convoys of Aboriginal intermediaries bearing pelts to exchange for knives, kettles, blankets, and other French goods.

“C’est l’aviron qui nous mène en haut”: Exchange Moves into the Interior, 1660-1696

While retaining its centrality in the fur trade during the latter half of the seventeenth century, Montreal ceased to function as the main point of exchange between the French and Aboriginal peoples. Rather, it became the principal staging ground and entrepôt for a trade that was moving steadily west into the pays d’en haut – the vast inland territory subsuming the Great Lakes and the Upper Mississippi River Valley. Frenchmen began moving into this region and establishing direct contact with Aboriginal hunters, trappers, and processors of furs. Three interrelated factors underlay this development. First, the Hurons could no longer function as commercial intermediaries after 1649-50, when they were decimated and dispersed by concerted attacks from the Iroquois League. The Hurons’ inability to resist these attacks had resulted, in part, from their military disadvantage: the Iroquois had been supplied with more and better quality muskets from their Dutch trading partners on the Hudson River. Second, the destruction of the Hurons’ carrying trade had resulted in the diversion of furs to the Dutch and – after 1664 – the English on the Hudson River. Third, decades of intensive exploitation had resulted in the depletion of fur-bearing animals in the St. Lawrence River Valley, pushing the trade further into the North American interior.

Less than four years after the dispersal of the Huron intermediaries, Jesuit Superior-General François-Joseph Le Mercier reported on a popular scheme among French settlers in the St. Lawrence River Valley:

[A]ll our young Frenchmen are planning to go on a trading expedition, to find the Nations that are scattered here and there; and they hope to come back laden with the Beaver-skins of several years’ accumulation. In a word, the country is not stripped of Beavers; they form its gold-mines and its wealth, which have only to be drawn upon in the lakes and streams, — where the supply is great in proportion to the smallness of the draught upon it during these latter years, due to the fear of being dispersed or captured by the Iroquois. These animals, moreover, are extremely prolific.

François-Joseph Le Mercier, “The Poverty and the Riches of the Country,” in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791, ed. Reuben Gold Thwaites (Cleveland: Burrows Bros. Co., 1896-1901), 40: p. 215.

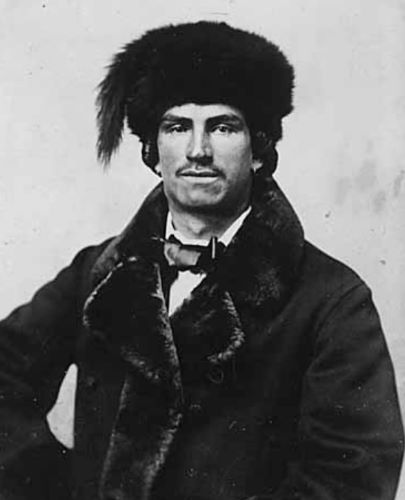

The work of carrying the French trade into the pays d’en haut was undertaken by independent pedlars known as coureurs de bois – literally “runners of the woods”. Outfitted for the most part by Montreal merchants, the coureurs de bois transported French goods into the interior by birchbark canoe and traded directly with Aboriginal fur suppliers in villages, camps, and hunting grounds. Their range of travel expanded rapidly, taking in Lakes Ontario, Michigan, and Huron as well as the Upper Mississippi, Ohio, and Illinois River Valleys by the mid 1670s and thus drawing far-flung Aboriginal groups into the French commercial orbit. Concurrently, increasing numbers of Frenchmen left the St. Lawrence River Valley to swell the ranks of the coureurs de bois. Some embarked on trading excursions that lasted only a season or two, whereas others spent years – even decades – in the pays d’en haut. In 1679, Intendant Jacques Duchesneau de la Doussinière et d’Ambault estimated that between five and six hundred coureurs de bois were plying the rivers of the western interior. The following year, he revised his estimation to eight hundred coureurs de bois out of a total population of 9,700 in the St. Lawrence River Valley settlements. According to Duchesneau, every family in New France could count at least one coureur de bois.

As more and more Frenchmen departed for the interior, colonial and metropolitan officials grew ever warier. These officials began to perceive the coureurs de bois and their activities as inimical to the development of a strong and sustainable colony. Under the far-reaching reform programme of Minister of Marine Jean-Baptiste Colbert, New France was intended to become a “compact colony” – economically diversified, demographically self-sustaining, and geographically confined to a defensible corridor along the St. Lawrence River. The exodus of coureurs de bois undermined this programme by draining the colony of its labour pool and scattering French resources over a vast territory. Ironically, Colbert himself had contributed to this overexpansion when, in the early 1660s, he had required the holders of the fur-trade monopoly to purchase beaver and moose hides at fixed prices. Coureurs de bois were therefore guaranteed a market for their pelts, and they responded to this opportunity by redoubling their trading activities in the western interior. In so doing, however, they saturated the European market and prompted Colbert to impose legal restrictions on the trade. In 1681, for instance, New France inaugurated the congé system under which a limited number of fur-trading licences – or congés – were issued annually. The system quickly proved ineffective: young men continued to abandon the St. Lawrence River Valley for the pays d’en haut – often illegally – and furs continued to flow into Montreal warehouses. By the mid 1690s, the supply of furs had so exceeded European demand that New France faced economic collapse. Hence, on May 21, 1696, Louis XIV revoked all congés and ordered the immediate closure of all but a handful of trading posts. Despite the prospect of severe punishment for trading in contravention of the royal ordinance, many coureurs de bois remained active in the interior and simply opted to sell their furs illicitly in Albany.

From Chaos to Structure: The Expansion and Reorganization of the Fur Trade, 1715-1760

The fate of the coureurs de bois was determined less by royal decree than by the dictates of economics. Already by the 1690s, traders had felt the need for additional capital as they expanded their operations over greater distances. Some had even begun working as wage-earning canoemen – or engagés – for merchants based in the St. Lawrence River Valley settlements. This type of salaried employment became increasingly common after 1715, when the European fur market began to revive and the trade ban was lifted. Every year, habitant men accepted contracts to transport goods, supplies, and pelts between Montreal and the far-flung posts of the pays d’en haut. Most of these engagés were recruited from Montreal and its immediate vicinity, though some hailed from the Trois-Rivières region. Each had his own reasons for accepting a fur-trade contract: some sought to supplement their families’ farm incomes, others to settle debts, others to escape the social and religious constraints of life in the St. Lawrence River Valley. Whatever their disparate motives, engagés joined together in an activity that was acquiring coordination, structure, and rhythm over the first half of the eighteenth century. After the spring thaw, they assembled in brigades at Lachine – above the treacherous rapids between the island of Montreal and the south shore – and boarded canoes laden with hundreds of kilograms of merchandise. Those aboard the spacious canots de maître transported goods and supplies to the posts of Detroit (at the narrows between Lakes Erie and St. Clair) and Michilimackinac (at the junction of Lakes Huron and Michigan), and carried furs from these posts back to Lachine in the late summer or autumn. These engagés were known, somewhat contemptuously, as “mangeurs de lard” – pork eaters – by the “hommes du nord” – men of the north – who paddled smaller canots du nord beyond Detroit and Michilimackinac into the Mississippi River Valley, Lakes Winnipeg and Manitoba, and the Saskatchewan River basin. Priding themselves on their hardiness and grit, the “hommes du nord” wintered in the interior and cultivated close relationships with Aboriginal groups there.

On the other side of the contractual relationship were merchants based in Quebec, Trois-Rivières, and especially Montreal – the organizational and administrative hub of the fur trade. By the 1730s, Montreal merchants had become specialized in recruiting engagés, outfitting fur-trade expeditions, and overseeing the shipment of pelts to Quebec and thence across the Atlantic to France. The most prosperous merchants were French-born and benefited from personal and professional connections to insurers, creditors, and shipping merchants in Rouen, Bordeaux, and La Rochelle. From his Montreal shop, for instance, the Parisian Pierre Guy conducted a steady business importing merchandise and exporting furs through the agency of the Rouen-based Robert Dugard et Cie and its Quebec-based factors, François Havy and Jean Lefebvre. Canadian-born merchants tended to have more modest capital bases and smaller business networks, and were therefore inclined to form partnerships to participate in the fur trade. These partnerships usually comprised three or four members who pooled their investment capital to purchase the lease on the trade at a particular inland post. One such partnership was Baby Frères, whose members – Canadian-born brothers François, Jacques, and Antoine Baby – were deploying themselves strategically between Montreal and the posts of the pays d’en haut by 1757. This arrangement afforded the brothers different vantage points from which to oversee their trading, transportation, and marketing operations.

Thus, by the mid eighteenth century, the fur trade of New France was becoming rationalized and structured along capitalist lines. The trade was coming under the control of urban merchants, who coordinated the movement of labour, goods, and supplies through an integrated transportation network connecting the far-flung posts of the pays d’en haut into the broader French Atlantic world. Yet although this network existed primarily for commercial purposes, it had also acquired political, social, and cultural dimensions that were critical to the French presence in North America.

Political Aspects of the Fur Trade

When French fur traders established a permanent presence in the St. Lawrence River Valley in the early seventeenth century, they were obliged to comply with the norms, values, and protocols that governed trade among local Aboriginal groups. These groups traded exclusively with close political and military allies, so the French were compelled to negotiate a place for themselves in an intertribal alliance that had taken shape before their arrival – an alliance comprising the Montagnais, the Hurons, the Algonquins, the Ottawas, the Nipissing, and others. Membership in this alliance required regular reaffirmation through gift-giving, speech-making, and – most critically – participation in war against the Iroquois League. It was in fulfillment of this military obligation that Champlain joined Montagnais and Algonquin raiding parties against the Iroquois in 1609 and again in 1610, both times employing firearms to devastating effect. Champlain’s actions confirmed to the Iroquois that the French were the latest tribe to join the enemy alliance and were therefore legitimate targets for aggression. Over the following century, the Iroquois mounted a violent campaign against the French and their Aboriginal allies – a campaign that escalated from the harassment of trade flotillas on the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Rivers in the early 1640s, to the dispersal the Hurons in 1649-50, to the capture or killing of nearly six hundred French colonists in the St. Lawrence River Valley in the late 1680s and 90s. For their part, the French and their allies launched multiple invasions into the Iroquois country where they razed villages, destroyed crop harvests, and looted graves. It was not until 1701 that the French and their allies reached a lasting truce with the Iroquois – the Great Peace of Montreal.

Having been drawn into an alliance system through the exigencies of the fur trade, the French began to use the trade for their own political and military ends in the early eighteenth century. Indeed, the trade became a central component of France’s North American strategy, which was largely a reaction to English – and, after 1707, British – territorial and commercial expansion. In the eyes of colonial and metropolitan officials, New France was coming under threat on two fronts. The first front was the chain of English-speaking colonies along the Atlantic seaboard, whose farmers and planters desired to push the agricultural frontier further inland. The second front was the southern shore of Hudson Bay, where the London-based Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) had been operating fur-trading posts since the early 1670s – thanks in large part to the assistance of renegade French traders, Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard Chouart des Groseilliers. Despite their efforts to dislodge the HBC by naval force, the French were compelled to acknowledge British claims to Hudson Bay under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. Thereafter, French policy aimed at restricting the British to these two coastal strips so as to block their future encroachment into the interior. This policy necessitated the abandonment of Colbert’s vision of a “compact colony” and its replacement with a vision of a vast cordon sanitaire hemming in the British east of the Appalachian Mountains and along the coastline of Hudson Bay. Lacking the manpower and resources needed to occupy this tract themselves and to impose formal governance structures, the French turned to their Aboriginal trading partners to implement their policy. They resolved to tie these partners more firmly into the alliance system, and to prepare them for the eventuality of war.

Under this new geopolitical policy, the fur-trading posts of the interior acquired tremendous strategic importance. They doubled as military command centres, provisioning depots, and meeting places where the French forged and reaffirmed alliances with Aboriginal groups. Over the first half of the eighteenth century, these posts became the principal nodes of a military-cum-commercial network that stretched from the mouth of the St. Lawrence River to the Great Lakes, and thence branched off in two directions: south, down the Mississippi River system to the Gulf of Mexico; and west, to the forks of the Saskatchewan River. Posts located along these two branches played a particularly important role in blocking English/British colonial and commercial expansion. On the Gulf of Mexico, for instance, Canadian-born brothers Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville established posts at Biloxi in 1699-1700 and Mobile in 1701. These posts became centres of exchange with the up-country Choctaw people, who provided deerskins to the French in return for arms, ammunition, and military accoutrements. Thus equipped, the Choctaws assumed an active military role as a bulwark against the English-speaking settlers of the Carolinas and their Aboriginal allies, the Chickasaws. Similarly, the Canadian-born Pierre Gaultier de Varennes et de La Vérendrye and his sons established a chain of fur-trading posts in the hinterlands of Hudson Bay between 1731 and 1743 – including Fort St. Charles on Lake of the Woods, Fort Maurepas near Lake Winnipeg, and Fort Paskoya on the Saskatchewan River. These posts enabled La Vérendrye and his sons to forge alliances with the Cree and the Assiniboine, and consequently to draw their pelts away from British traders on the bayside.

Until the fall of New France in 1760, the fur trade served as an effective means of winning and holding the allegiance of Aboriginal peoples against the English/British. It enabled the sparsely populated colony to extend its political and military influence over a vast swathe of the North American interior, thereby thwarting the expansionist designs of English-speaking farmers, planters, and traders. The fur trade also enabled New France to mobilize thousands of well armed and strategically located Aboriginal groups at the start of the Seven Years’ War – known, tellingly, as the “French and Indian War” in the Thirteen Colonies and later the United States. To many Aboriginal groups, the French represented a more palatable – or at least subtler and less immediately destructive – version of colonialism than did the British. Unlike the British, the French did not pursue the large-scale appropriation of Aboriginal lands for settlement and agriculture. What the French wanted was fur, and this pursuit required the preservation of existing ecosystems and the exploitation of Aboriginal knowledge and skills. “Brethren, are you ignorant of the difference between our Father [the French] and the English?”, asked a Catholic Iroquois in 1754. “Go see the forts our Father has erected, and you will see that the land beneath his walls is still hunting ground, having fixed himself in those places we frequent, only to supply our wants; whilst the English, on the contrary, no sooner get possession of a country than the game is forced to leave it; the trees fall down before them, the earth becomes bare, and we find among them hardly wherewithal to shelter us when night falls.”

Social and Cultural Aspects of the Fur Trade

As a conduit for European influence, the fur trade was an agent of change in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Aboriginal societies and cultures. One component of this change was the influx of tools, utensils, and weapons that were more efficient and more durable than their prehistoric equivalents. Indeed, French traders and missionaries noted that Aboriginal peoples were especially eager to acquire copper kettles, iron utensils, and steel axes, knives, awls, and needles. As early as the 1660s, some of these traders and missionaries believed that the Hurons and their Algonquian-speaking neighbours were growing dependent on French metal goods and were ceasing to manufacture similar objects of stone, wood, or bone. Archaeological evidence suggests, however, that these Aboriginal groups persisted in making and using traditional tools long after obtaining access to metal ones. Moreover, these groups appear to have assimilated French goods into traditional cultural patterns and practices. For instance, the Hurons accumulated French goods in order to share them with immediate and extended kin, or to redistribute them at institutionalized gift-giving ceremonies – a practice that served to honour the dead, to seal agreements and alliances, and to enhance an individual’s social status. In other words, French goods did not necessarily – or at least, did not immediately – transform underlying values, attitudes, or beliefs. These goods often brought surface changes without fundamentally remaking Aboriginal societies and cultures.

Writing from Quebec in summer 1626, Jesuit Superior Charles L’Allement described the wares carried by newly arrived merchant ships on the St. Lawrence River:

These two ships bring all the merchandise which these Gentlemen use in trading with the Savages; that is to say, the cloaks, blankets, nightcaps, hats, shirts, sheets, hatchets, iron arrowheads, bodkins, swords, picks to break the ice in Winter, knives, kettles, prunes, raisins, Indian corn, peas, crackers or sea biscuits, and tobacco; and what is necessary for the sustenance of the French in this country besides. In exchange for these they carry back hides of the moose, lynx, fox, otter, black ones being encountered occasionally, martens, badgers, and muskrats; but they deal principally in Beavers, in which they find their greatest profit. I was told that during one year they carried back as many as 22,000. The usual number for one year is 15,000 or 12,000, at one pistole each, which is not doing badly.

Charles L’Allemant, “Letter from Charles L’Allement, Superior of the Mission of Canadas, of the Society of Jesus. To Father Jerome l’Allement [sic], his brother,” in The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents: Travels and Explorations of the Jesuit Missionaries in New France, 1610-1791, ed. Reuben Gold Thwaites (Cleveland: Burrows Bros. Co., 1896-1901), 4: p. 207.