Examining the mostly forgotten rebellions against plantation owners by enslaved people.

By Dr. Deion Scott Hawkins

Assistant Professor of Argumentation & Advocacy

Emerson College

Introduction

From Nat Turner’s insurrection in 1831, the story of which was developed into a movie, to the squelched insurrection in 1687 of a Black man named Sam who was owned by Richard Metcalfe, insurrections and rebellions have always been used by Black people who were enslaved in the U.S.

According to federal law, an insurrectionist is “whoever incites, sets on foot, assists, or engages in any rebellion or insurrection against the authority of the United States or the laws thereof, or gives aid or comfort thereto.”

If found guilty, an insurrectionist could be fined or imprisoned for no more than 10 years and “shall be incapable of holding any office under the United States.”

In my view, rebellions of the enslaved can aptly be classified as insurrections.

From the early 1600s, historians estimate that there were around 250 insurrections in America that involved 10 or more enslaved people using violence to fight for equal rights.

In his work published in 1937, historian Herbert Aptheker writes, “Nothing has been more neglected, nor, more distorted than the story of slave revolts.”

A few of them are summarized below.

September 1739: 13 Original Colonies

The Stono Rebellion was the largest and deadliest insurrection by enslaved people in the 18th century.

In a bloody fight for freedom, dozens of enslaved men raided a firearms store and attempted to journey to freedom. The group grew to about 60 people and continued to fight, but white people quickly stopped the progress.

By dusk, the insurrection had ended. Half the men were killed and the other half captured, left to an uncertain fate.

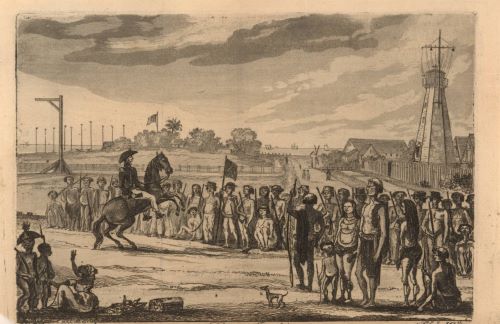

January 1811: New Orleans

Inspired by the Haitian Revolution, when people of color overthrew their French colonizers at the turn of the 19th century, Charles Deslondes led one of the largest insurrections in American history.

Armed with muskets and ammunition stolen from the plantation’s basement, formerly enslaved people mobilized and killed their owner Manuel Andry and his son, Gilbert.

Donning the military uniforms once proudly worn by their oppressors, the group continued throughout New Orleans, wreaking havoc on plantations along the way. It is estimated that between 200-500 people participated in the insurrection before a white militia defeated them.

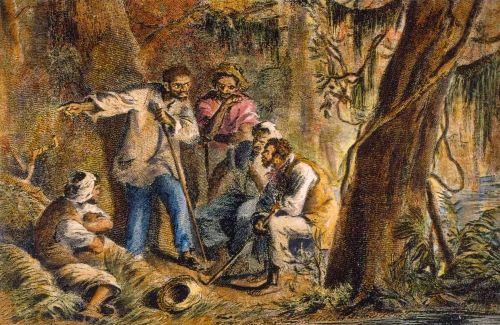

August 1831: Southampton County, Virginia

One of the most well-documented and well-known slave insurrections in history was led by Nat Turner. As a preacher, Turner used his belief in God to unite the enslaved and lead the largest insurrection in American history.

Known as the Southampton Insurrection, Turner’s rebellion started where he was enslaved, the Travis plantation near Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in what’s now the United States. After he and around 70 rebels killed the plantation’s owner, they marched throughout the county, resulting in the death of nearly 60.

Thirty years later, in 1861, The Atlantic published a recounting of the insurrection by white abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson.

“The black men passed from house to house, not pausing, not hesitating, as their terrible work went on,” Higginson wrote. “From every house they took arms and ammunition, and from a few, money; on every plantation they found recruits.”

Unequal Insurrections?

In their article “From Protest to Riot to Insurrection,” National Public Radio journalists detailed the importance of using specific language to cover Jan. 6.

Merriam-Webster observed a 34,000% increase in individuals looking up the definition of “insurrection” in the days following Jan. 6, 2021.

The word was also listed as runner-up for 2021 word of the year, losing to “vaccine.”

Despite the interest in the word and the ongoing debate over the events of Jan. 6, 2021, in my view some insurrections are more equal than others as the legitimate plight of enslaved people continues to be be ignored, overlooked and all but forgotten.

Originally published by The Conversation, 01.05.2023, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.