How has the West been imagined as both America’s manifest destiny and a wild frontier?

By Dr. Hana Layson

Manager of School and Educator Programs

Portland Art Museum

By Dr. Scott Manning Stevens

Associate Professor of Native American and Indigenous Studies

Syracuse University

Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, 11.28.2012, Newberry Library, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Introduction

In Chicago, in 1893, the historian Frederick Jackson Turner delivered a lecture entitled “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” Turner argued that “the existence of an area of free land, its continuous recession, and the advance of American settlement westward” had defined American society. The frontier had set the conditions for a unique national identity by freeing Americans from the influence of Europe and creating inexhaustible economic opportunities. These opportunities fueled American understandings of equality and liberty. Turner concluded his talk by noting that the frontier was now closed. Americans had settled the continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific and would never again enjoy “such gifts of free land.”

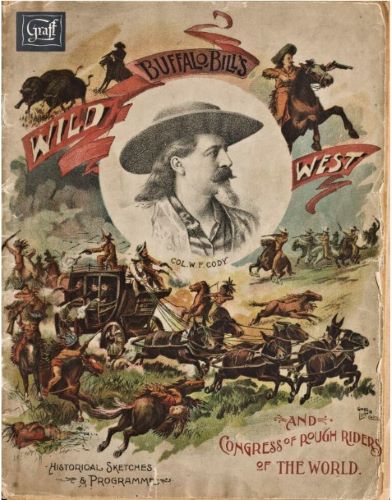

Turner and his audience were not the only ones thinking about the American West on that day in Chicago. On 63rd Street, “opposite the World’s Fair,” Buffalo Bill’s Wild West performed twice a day “before a covered grandstand that could hold eighteen thousand people.” The show claimed accurately to portray life on the frontier. It featured enactments of historic battles between whites and Indians, whose parts were played, not by actors, but by people who had actually fought in some of those battles. Their participation in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West seemed to attest to the authenticity, or historical accuracy, of the performance.

Historian Richard White describes Turner and Buffalo Bill (William F. Cody) as “the two master narrators” of the American West. Each articulated powerful, if conflicting, stories: “Turner’s history was one of free land, the essentially peaceful occupation of a largely empty continent, and the creation of a unique American identity. Cody’s Wild West told of violent conquest, of wresting the continent from the American Indian peoples who occupied the land.” The hero of Turner’s story is the farmer who “overcame the wilderness” with “the axe and the plow.” The hero of Buffalo Bill’s story is the scout who “overcame Indians” with “the rifle and the bullet.” Both stories continue to operate powerfully within the national imagination.

But these are not the only narratives that we have of the West. American Indian art and literature from the late nineteenth century suggests profoundly different ways of understanding both Indian cultures and the significance of the frontier. The following collection of documents invites readers to explore, compare, and critique these narratives and counter-narratives of the American West.

Manifest Destiny

When Frederick Jackson Turner presented his “frontier thesis” in 1893, he synthesized and elaborated ideas that had been in circulation for decades. The writer John L. O’Sullivan had introduced the phrase manifest destiny in 1845 to express the idea that God had given North America to the United States to promote the principles of republican democracy. He argued that the United States did not share Europe’s history of tyranny and warfare and, therefore, was destined to be the great nation of futurity… Yes, we are the nation of progress, of individual freedom, of universal enfranchisement.” O’Sullivan didn’t address the existence of slavery, the disenfranchisement of “free” women, the historic and ongoing violence against American Indians in the East, or the presence of American Indians in precisely the Western lands that he now urged the United States to occupy.

Almost 50 years later, Turner offered a more nuanced and elaborate account of the meaning of the West in his lecture “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” But he reiterated O’Sullivan’s premise that the frontier had been essential to “the promotion of democracy” and the national commitment to individual liberty. The frontier, he argued, broke “the bond of custom, offering new experiences, calling out new institutions and activities.” It forced Americans repeatedly to move through the three stages of civilization, personified as the pioneer, the farmer, and, finally, the “man of capital” who brings urban development. Thanks to the frontier, Turner wrote, “America has been another name for opportunity… [With its closing,] never again will such gifts of free land offer themselves.”

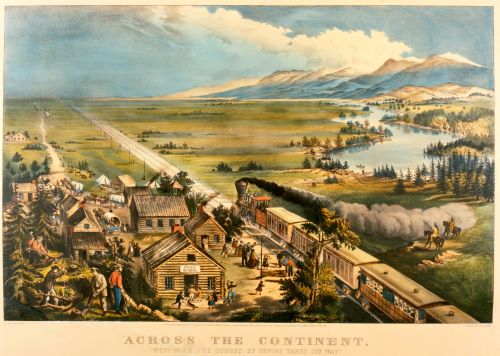

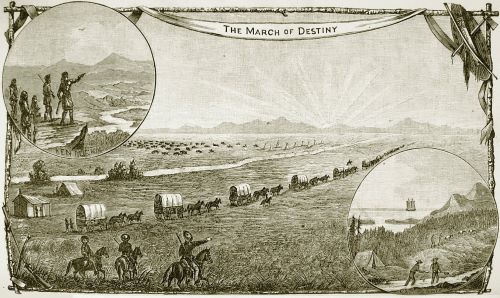

The popular illustrations in this section offer visual representations of O’Sullivan’s and Turner’s arguments. Across the Continent is a hand-colored lithograph by a woman artist, Frances F. Palmer. It was published during the construction of the nation’s first transcontinental railroad, which created a route from the Atlantic to the Pacific in 1869. “The March of Destiny” is the frontispiece of Frank Triplett’s illustrated history of the United States, featuring “the romantic deeds, lofty achievements, and marvelous adventures” of figures such as Daniel Boone and Davy Crockett.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West

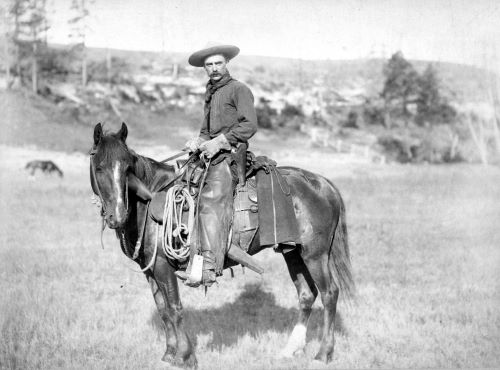

William F. Cody (or, Buffalo Bill) designed his Wild West to be much more than a show. His goal was to re-enact history before the eyes of his audience members. As historian Richard Slotkin describes it, citing language from the program, the Wild West presented the history of the frontier as a series of “Epochs,” beginning with “the Primeval Forest, peopled by the Indian and Wild Beasts only,” continuing through the arrival of the Pilgrims in 1620, then jumping to the mid-nineteenth-century settlement of the Great Plains. Performers would enact a mock buffalo hunt and portray battles between whites and Indians. Between acts, performers demonstrated “Cowboy Fun,” riding horses, roping cattle, and shooting pistols. The show was rife with gross historical inaccuracies (closer to mythology than history, in Slotkin’s account), but, at the time, Cody’s portrayal of the frontier was widely accepted as true. It would influence popular representations of the American West for decades to come.

The show’s credibility derived in large part from the identities of its performers. Cody himself was a scout for the cavalry before he became an actor and, during the time he ran the show, returned several times to the battlefield. Furthermore, in the Wild West, he employed not only actual U.S. Cavalry troops, but many of the Plains Indians who had recently fought against them. Even a great leader, such as Sitting Bull, the Lakota chief credited with defeating General George Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn, spent four months with the show after his tribe’s surrender.

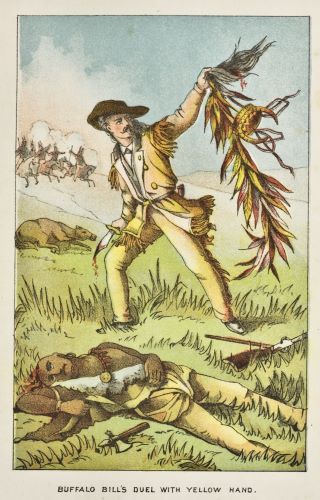

Historian Richard White recounts one of the most complicated examples of Buffalo Bill’s conflation of history and spectacle in his killing of a Cheyenne named Hay-o-wei (translated as Yellow Hand). Cody had temporarily left the show to participate in the Plains wars in the summer of 1876, the time of Custer’s Last Stand. Cody prepared for the battle by dressing in his Wild West costume. After killing and scalping Yellow Hand on the battlefield, Cody returned to the show to re-enact the encounter nightly on stage as “The Red Right Hand; or the First Scalp for Custer.” “Meanwhile,” according to White, “Yellow Hand’s actual scalp went on display in theaters where Buffalo Bill performed.”

Cody’s staging of this battle and his display of Yellow Hand’s scalp suggests the complexity of the representation of violence in these frontier narratives. White finds that, in stories of the Wild West, “everything is inverted.” Buffalo Bill’s show “presented an account of Indian aggression and white defense; of Indian killers and white victims.” The most celebrated battles are not victories, but defeats, such as the Battle of Little Bighorn and the Alamo. White argues that these inversions provided Americans with moral justification for conquering the West. American violence appeared as legitimate retaliation against Indian savagery.

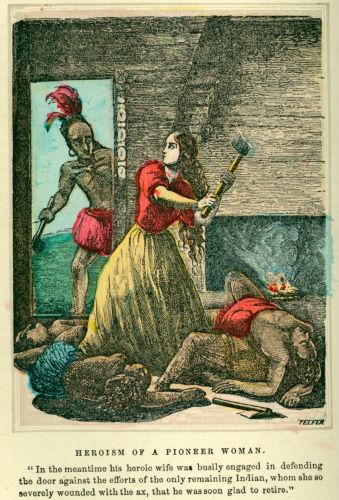

Imagining the Frontier Woman

White women feature prominently in popular stories of the frontier from the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries. Many of these are captivity narratives, stories of white women’s capture by—and rescue from—American Indians. “Heroism of a Pioneer Woman,” reproduced below, pursues the somewhat different formula of the hardy and skillful frontierswoman, capable of performing the same kind of violence as her husband. This image accompanied the tale of a 1791 attack on the John Merrill home in Kentucky in which Mrs. Merrill killed five attackers with her ax.

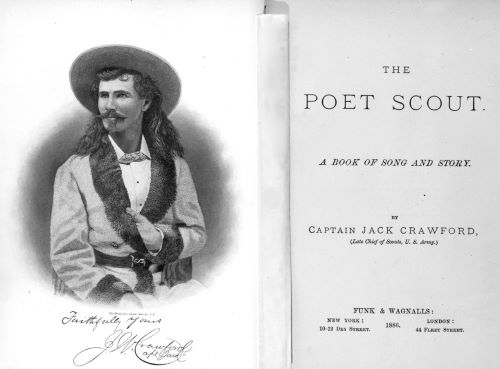

The second document, an illustrated poem by Jack Crawford, unites the captive and the skilled frontierswoman in the figure of Maggie, “the girl trapper.” As historian Richard White explains, Crawford, like Buffalo Bill, combined service as a scout in the cavalry with cultivating his own celebrity as a frontier icon. In Crawford’s case, this celebrity primarily took the form of writing, though he also performed with Buffalo Bill in 1877. He identified himself as the Poet Scout and published his work in New York and Western newspapers as well as in the book excerpted here. Crawford presents this poem as a campfire story told by his companion in Indian fighting, California Joe.

Counter-Narratives: American Indian Cultures of the West

The group of documents in this section offers three distinct perspectives on American Indian cultures of the West. The first is a painting by Seth Eastman, a soldier in the U.S. Army who created hundreds of illustrations of American Indian life in the mid-nineteenth century. Many of these works were published in Henry Rowe Schoolcraft’s six-volume, government-funded work, Information Regarding the History, Conditions, and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States. While many of Eastman’s works portray the Dakota people in what is now Minnesota, this painting represents a Zuni community in New Mexico. The Zuni are one of the Pueblo peoples, who established agricultural societies in the Southwest thousands of years before the arrival of Europeans. The term pueblo also refers to their towns and, specifically, to their adjacent, multi-story, stone and adobe houses.

The second document is a drawing by Frederick Gokliz, a Chiricahua Apache artist from the San Carlos Indian Reservation in southeastern Arizona.

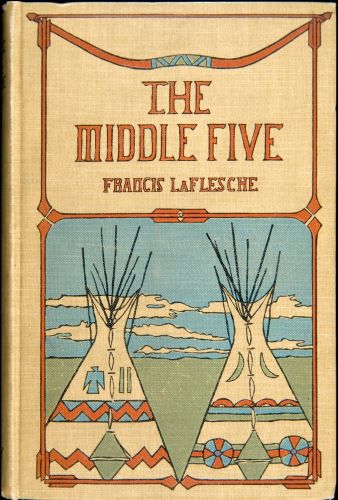

The final document is an excerpt from Francis La Flesche’s memoir, The Middle Five, which describes his experiences in a Presbyterian mission school on the Omaha reservation. During the 1870s and 1880s, the federal government created an Indian school system with the explicit purpose of weakening Indian resistance to U.S. power. Indeed, Indians who attended these boarding schools, which were often aligned with Christian missions, often came away deeply ambivalent about their experience. On the one hand, it was clear that learning to read and write in English and becoming versed in U.S. culture had enormous practical advantages. On the other hand, as historian Frederick E. Hoxie writes, “the education most commonly available to Indians was offered by arrogant government officials who expected Indian communities to conform to Victorian social standards and, ultimately, to vanish.” La Flesche, a writer of mixed Omaha Indian and French ancestry, was one of the first to publish an account of his experiences in boarding school. The frontispiece illustrates La Flesche’s description of his own arrival at the school, when he was comforted by another Indian boy wearing an American school uniform. The title refers to his group of friends. La Flesche dedicated the book to “the universal boy.”

Two Portraits of Silver Horn

In 1897 the painter Elbridge Ayer Burbank was commissioned by his uncle Edward E. Ayer to produce a series of portraits of prominent Indian chiefs. Ayer was a business magnate and dedicated collector of books, art, and manuscripts related to American Indian cultures. (He eventually donated this collection to the Newberry Library and the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.) Burbank traveled throughout the West, creating portraits of celebrated leaders, such as Geronimo, Sitting Bull, and, here, Silver Horn (also known as Hawgone).

Silver Horn was born in 1860 to a prominent Kiowa family that resisted confinement to the reservation and participated in the Red River War of 1874–1875. In the first decade of the twentieth century, he worked with the ethnologist James Mooney, creating drawings of the designs on Kiowa shields and tipis. He died in 1940.