The relationship between imperial governments and surgeons in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

By Dr. Kieran Fitzpatrick

Post-Doctoral Fellowship in Humanities

National University of Ireland

Introduction

The following chapter is concerned with the ways in which political, social and cultural contexts shape the performance and perceptions of surgery, espe-cially under nineteenth-century colonial empires. This central focus is intro-duced by an examination of the following case.

The twenty-year-old labourer was admitted to hospital at approximately 1.30pm on 18 August 1887, suffering from a compound fracture of the upper right fibula, and a dislocation of the right knee. His injuries had been caused a few minutes before by a confluence of his knee having been caught in the railings of a bridge across the city’s river and subsequently being struck by a heavily laden vehicle passing in the opposite direction.

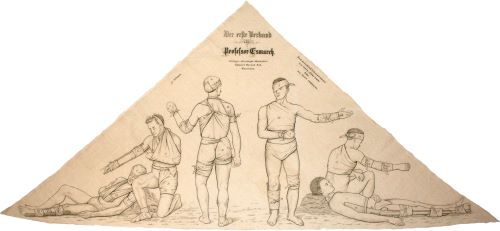

The surgeons charged with treating him acted, it seemed, immediately. They stemmed the haemorrhage from a wound caused by the protrusion of his fibula using an ‘Esmarch’s bandage’. Then, after supplying him with a quarter gram of morphia through hypodermic injection to ease his pain, they placed him under the influence of chloroform ahead of surgery. The wound created by his fibula was enlarged with the intention of sawing off the sharp-ened end of the broken bone using a ‘Butcher’s Saw’. The records of the case then state that the surgeons removed ‘the condyles, the upper portion of the heads of the tibia and the patella.’ They concluded the operation by bringing the edges of the wound together using ‘goose sutures’ and dressing it with ‘oilsilk, oakum and bandages.’ Their final act was to place the leg in bracketed back and side splints, before placing it in a ‘Salter’s Swing’.1

The description of the case could be an element of a particular sort of his-tory of surgery, namely the history of surgery as a history of surgical tech-nologies; all of the implements documented within the case have fascinating histories in and of themselves. For example, the use of a ‘Butcher’s saw’ was not, as might be expected, a colloquial name for the implement used in con-temporary surgery. It was, instead, a specific type of saw, named after the sur-geon who invented it: the Irishman Richard G. H. Butcher (1819–1891). Butcher specialized in the excision of the patella and its surrounding physio-logical structures. He became so specialized in this particular surgical practice that he devised a saw that would aid in his work to a greater degree than any other then in use.2

Similarly, we could highlight the reference to ‘Esmarch’s bandage’, an invention made by Johannes Friedrich August von Esmarch (1823–1908) in 1877, which was designed to decrease the risk of haemorrhage in operations on the extremities by forcing all of the blood out of a limb through an elastic bandage.3 Finally, our technical history of the surgeons’ practice would have to contextualize the use of ‘Salter’s Swing’, named after Sir James A. Salter, who devised it over the course of 1849–1850, because he believed that ‘the plan of swinging broken legs in their treatment is attended with great benefit and immense comfort to the patient.’4

However, the history of surgery is not just about the material aspects of technology, their invention and their implementation; it is, too, about the social, cultural and institutional contexts that shape them, the people who use them and the people they are used on. In short, we must also understand sur-gery in terms of the historical specifics of time and space.

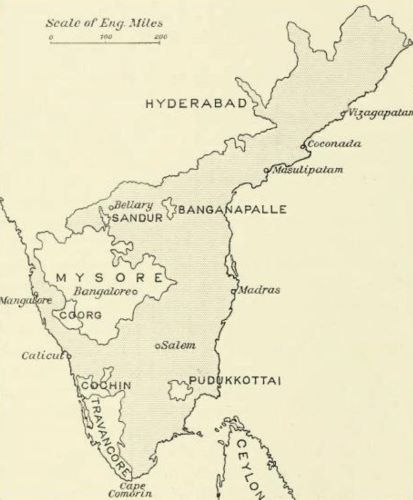

How does knowing that the young man in our case study was named Venkatachellum, a Hindu resident of Madras, India (present-day Chennai) change our understanding of the case’s history? Madras was at the time the capital of the Presidency of the same name, which was in turn a key constitu-ent division, along with Bengal and Bombay Presidencies, of Britain’s Indian Empire. How did Venkatachellum’s ethnicity shape his treatment? What ver-bal or written exchanges took place between himself and the surgeons who treated him, and how well did he understand these interactions? Then, about the surgeons themselves: how did they come to be in Madras, practicing at the city’s General Hospital (MGH)? Many of the surgeons who practiced in the MGH at that time had been educated across the UK and grown into medicine surrounded by ideals and institutional reforms that promoted a coherent set of professional ideals. How congruent with or divergent from these new ideals were the imperatives of imperial rule?

These are the sorts of questions I want to pursue in this chapter. In order to answer them appropriately, the work presented must draw on varimedicine, imperial and colonial history) that all make relevant contributions to the topic. In the field of imperial and colonial history, for example, Frederick Cooper, Ann Laura Stoler and Antoinette Burton have argued convincingly for viewing modern empires and their colonies as sites of complex interaction, rather than hosting simple, binary relationships between ‘colonizer’ and ‘colonized’.5 Similarly, contributions to the history of global health and its institutions have questioned discrete divisions between ‘Western’ and ‘non-Western’ categories of medicine. Hormoz Ebrahimnejad and others have shown that the creation of these categories was a function of anti- and post-colonial politics dating from the mid-twentieth century, rather than pro-viding an accurate framework for representing historical realities in the fore-going century-and-a-half.6 Indeed, Biswamoy Pati and Mark Harrison have questioned whether or not phrases such as ‘colonial medicine’, that is a medi-cine that is distinctly western, European and different from its surroundings, have any real meaning.7 Finally, if we wish to know more about the actions of colonial surgeons such as those who treated Venkatachellum, what do we need to know about the institutions that produced and managed them? John MacKenzie and a host of contributors to Blackwell-Wiley’s gargantuan Encyclopedia of Empire defined an empire as ‘an expansionist polity which seeks to establish various forms of sovereignty over people or peoples of an ethnicity different from … its own.’ However, the expansionism of these polities is also accompanied by their creation of ‘over-extended structures which can be readily weakened by failures of central rule … cracks in its administrative and bureaucratic systems, or through the resistance of provinces, of the incorpo-rated peoples or of adjacent empires.’8 How did these sorts of institutional dynamics inflect upon the potential for and nature of practice conducted by colonial surgeons?

In order to knit these various literatures together coherently, my analysis is arranged in terms of a ‘funneled’ history of surgery and empire, beginning with broad insights into the relationship between imperial governments and surgeons in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I then move into the more intimate, practical spaces of surgical wards and patients’ houses to examine what surgical practice represented culturally, socially and economically, and the effects that colonial societies had upon it. Although the chapter’s content is informed to mostly by my own research on Irish surgeons practicing in the Indian Medical Service (IMS) between 1850 and 1930, it also points to the possibilities of related research on other periods and locations, whether imperial-colonial or otherwise.

Surgeons, Empire, and Professional Institutions

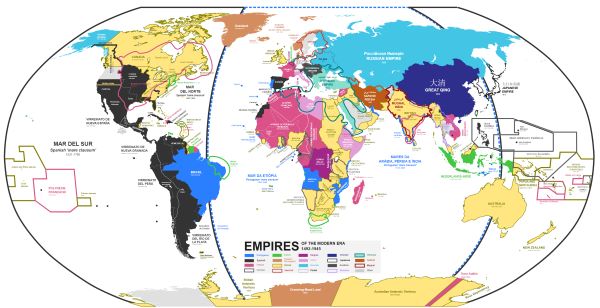

Nagihuin, Wikimedia CommonsMacKenzie’s definition of empire, provided above‚ is a sensible place to start this section. What if we think about the contents of this definition in specific relation to surgeons who plied their profession through imperial employment? The period between 1800 and the end of World War I was marked by the geographic expansion and consolidation of European empires abroad, and of modern professions at home. The expansion of empires, which occurred across the world in a multitude of ways, has been the subject of numerous volumes of scholarly literature. Britain consolidated the administration of its Indian Empire; fought a succession of frontier wars on the northwestern and northeastern frontiers of the subcontinent against various tribal groups and (by proxy) the Russian Empire; a range of European powers scrambled for Africa; and archaeologists, farmers, land prospectors and commercial companies instituted invasive changes in Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the African continent, imposing new communities and epistemologies in the process.9

The expansion of modern professions has been described as a process of evolving ideas from within certain occupations that induced changes in the nature of bureaucratic and educational institutions, both in metropolitan nation-states, but also across European colonies.10 As Christopher Lawrence once noted for central ideas about surgical professionalism in Britain, ‘in accord with the “spirit of the times”, surgeons were heroes, models of the Victorian cult of manliness’.11 Lawrence’s emphasis on the muscularity of surgeons in the popular imagination harmonizes with a recurrent theme in the history of the professions more broadly. In his 1989 book on ‘professional society’ in England from c. 1880 to 1980, Harold Perkin defined the ‘professional ideal’ in terms of a masculine Christianity, but, in tandem, illustrated how it was ‘based on the primacy of expert selection by merit, measured no longer by aristocratic opinion, the competition of the market or popular vote but by the judgment of the qualified expert.’12 Professionalism was a function, then, of deeply held, aspirational ideals and consequent changes in administrative and educational processes.

There have been few works that examine where the expansion of empire and professions met one another, which is surprising given the amount of primary sources indicative of these interactions. The calendars of contemporary universities in the UK were often replete with the entrance requirements for rapidly professionalizing services, such as the various public services in India, although their prevalence varied depending on changing political and social attitudes towards empire at a local level.13 Elsewhere, the pages of school magazines and popular pamphlets that were aimed at adolescents hosted insights from purportedly successful professionals already in situ in the colonies.14 These are examples of ways in which social processes, institutional change and cultural values across the boundaries of nation-states supported professionalization within the particular context of surgery. Although Thomas Bonner’s work has touched on variations in educational culture across the Anglo-European world, further research in the same transnational vein could turn up novel insights into how cultures and ideals of professionalization occurred and interacted with one another in different ways.

The most notable volume to date that focused specifically on the British empire and its exporting institutions, methods and values of medical profes-sionalization is Lawrence Brockliss, Michael Moss, Kate Retford and John Stevenson’s detailed study, Advancing with the Army Medicine, the Professions, and Social Mobility in the British Isles, 1790–1850. The authors focused on the Army Medical Department (AMD), and showed how the administrators of military medicine were ‘early adopters’ in terms of instituting selection by merit rather than aristocratic patronage.

Brockliss etal. showed that, although not uniformly successful, at the start of our period the AMD instituted new regulations that defined a minimum set of professional competencies for entrance to the service, and appointed James MacGrigor to the position of Surgeon-General. MacGrigor imple-mented ‘the practice of keeping detailed individual career records by demand-ing that existing medical officers and new recruits completed a pro-forma curriculum vitae which could then be periodically updated.15 In comparison, the IMS did not begin to systematically implement expected professional standards for the surgeons it employed until the mid-1860s. Interestingly, its Bengal branch provided an institutional blueprint for the establishment, in 1820, of a civil medical service in Java, Indonesia under the governorship of Thomas Stanford Raffles, an early example of how models of professionalization spread across colonial locations.16

According to MacKenzie, empires are not polities that inexorably expand, exporting ideas, goods and people in an uninterrupted deluge. Rather, imperial history is also a history of internal contradiction and conflicting priorities. So, how does the history of the surgical profession relate to this second aspect of MacKenzie’s definition? In the case of the IMS, by mid-century imperial administrators and their colonial counterparts were well aware of the need for imperial and colonial medical services to attract highly trained, broadly educated medical professionals. This broad awareness was focused more specifically during Sir Charles Wood’s tenure as Under-Secretary of State for India between 1859 and 1864. During this time, the IMS moved towards expected standards of professional competency akin to those first implemented at the start of the century in the AMD.17

But the State’s recognition of a need for more professional surgeons and physicians to populate their medical services was not accompanied by a rationalization of attitudes or policies towards medical work. For example, throughout the 1860s, 1870s, and 1880s, recurrent debates took place concerning whether two separate medical administrations treating European and native troops, as had been the case up until that point, were necessary. The fact that these debates endured reflected the unwillingness of the IMS’s governing institutions to recognize the professional credentials of the surgeons employed by the Service, an uneasy state of affairs that would linger through to the 1940s.18

Medicine and surgery under the Government of India was arranged in such a way that the AMD supported ethnically British troops, whilst the IMS was expected to provide medical support to the native soldiers of the Indian Army, as well as performing civilian duties as civil surgeons, dispensary officers and public health officials. Some voices in India, such as the administra-tor Sir William Muir (1819–1905),19 believed that ‘the first and most flagrant … waste of power and money … is that of European Medical Officers now attached to Native Regiments’. These officers were deemed to have ‘little or nothing to do’ because of the ‘trifling sickness occurring in native corps’.20 If allowed to continue, Muir thought, ‘without adequate professional employment’, these surgeons would inevitably rust and deteriorate in ‘their value as Government servants’.21

The racial stereotyping of native soldiers as ‘of ’ the climate, and therefore not in need of as much medical attention as their European counterparts, was part of the racial politics of military policy in India.22 In a more pragmatic vein, Muir’s report also related to the divisiveness of racial segregation in determining the nature of the practice that medical officers and surgeons could carry out as well as the value that was placed on their professional practice by their employers. One Irish surgeon, Winthropp Benjamin (W. B.) Browning was temporarily deployed as the surgeon in charge of a regiment of the British, rather than the Indian, Army in Madras Presidency from December 1882 to March 1883. As a result, he found himself locked into a battle with representatives of the local government over the amount of pay he was entitled to, because an IMS surgeon treating white rather than Indian troops would receive less pay than under his usual professional remit.

The regulations cited by local administrators still shaped policy making, but they were antiquated and conflicted with recent changes to the service conditions of IMS surgeons on duty. Browning’s plea for financial recognition of time spent with the British Army was made on the grounds of a sense of professional ‘justice’, in order to circumvent these antiquated regulations, but was rejected by the local government. Eventually, his case was brought before Earl Kimberley, the Secretary of State at the India Office, in October 1883. While Kimberley and others were sympathetic to Browning’s claim, there is no extant evidence left to ascertain whether his pleas for professional recognition were ever met.23

Browning’s case was notable for a number of reasons. First, it highlights the manner in which the racial ideologies of the British state could prevent a surgeon from being paid for professional services rendered. Browning’s practice was not being determined by his intellectual abilities or practical skill, but by the assumption that treating native troops automatically reduced the quality of a surgeons’ work. Second, the fact that what was a relatively simple matter concerning pay and conditions could not be resolved at a local level reflects an instance of administrative incompetence. That the India Office’s Secretary of State in London, thousands of miles away, heard Browning’s plea was quite remarkable.

In another case from later in the century, one of Browning’s compatriots, George Hewitt (G. H.) Frost, could not claim his full amount of pay because he had not sat the compulsory ‘Lower Standard Examination in Hindustani’, which would provide a formal reflection of his ability to communicate with native soldiers. Given the lack of definition provided in archival material on the subject, ‘Hindustani’ should be assumed to have a literal meaning as one of a trio of languages, the others being Urdu and Hindi, that had overlapping jurisdictions and political significances at the time.24 Frost was one of a number of surgeons who aired grievances to the Government of India about the docking of their pay on these grounds. The reason they had not passed the exam, they stated, was a result of ‘the many changes of station and duties required’ which made it ‘almost impossible … to carry on that steady and consecutive study which is necessary to pass’.25

Frost’s case was particularly interesting because it drew on a further aspect of imperial rule in India relating to surgeons and their practice: geographic space. The expectations placed on a surgeon in the employ of the Government of India to be geographically flexible were acute. This often meant being stationed, either in military or civilian duty, for very short periods of time, and then travelling large distances around the sub-continent for redeployment. In his first nine months of service in India, Frost changed roles nine times and consequently travelled 3100 kilometers around the then unruly North-Western Frontier Provinces (present-day Pakistan, north-western India and Afghanistan).26

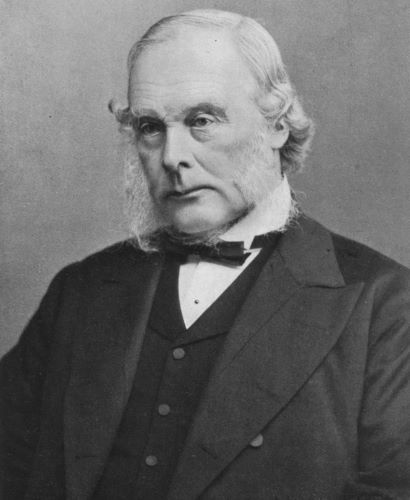

Constructing a spatial history of surgical careers can be an important part of future research on the history of surgery, although it is not entirely novel. In their prosopographical study of Joseph Lister’s students, Anne Crowther and Marguerite Dupree followed individual biographies of a whole generation of surgical practitioners and noted the significance of colonial careers for the group of surgeons they focused upon.27 This prosopographical approach should be utilized in tandem with quantitative methods, rooted in computer science, which would then allow for the recreation of career paths through various institutions, both colonial and otherwise.

Colonial India is a good case study for such work, as there are a number of sources that allow for the recreation of career trajectories, not least the Indian Army lists. The lists were annual, published records of every public servant under the employment of the Government of India, and a relatively full set of the volumes currently reside at the British Library.28 Therefore, the documents provide information about where those employees were based geographically, what duties they performed in that year, and what rank they possessed. The collection thus represents a stable time-series, which can be used to track the career progression and geographic stability of a surgeon’s career, as well as the professional activities they carried out. Over the past three years, a project has been underway, piloted by the author and members of the support staff at IT Services, Oxford. While the focus of that project has been wide-ranging, career trajectories have formed an important part.

Such data reveal a number of characteristics of life as a surgeon in the employment of the Raj. In particular, is it possible to establish whether or not an ability to resist early and frequent relocation, such as in Frost’s case, had an impact on building a stable professional practice and success later? Similar sources for later periods, c. 1900–1950, would allow for comparisons of the careers of IMS surgeons as the racial composition of the Service changed radically.29 Tracing these institutional changes through collective career paths across European empires would allow for a broader perspective in the historical study of professional career making in a global context.

In summary, these insights into medical institutions, their inter-relationship with the dynamics of imperial and colonial governance, as well as the effects of those inter-relationships on the careers of surgeons, invite us to think more generally about the historical relationships between change in political institutions and the modern professionalization of surgery. Future work should apply similar methods and work with similar sources across modern empires. The resulting work would be able to establish whether tensions between a modernizing profession and the imperatives of imperial or colonial governance presented themselves in other contexts, too. This approach is also applicable to non-colonial contexts, such as the nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries’ other dominant forms of political organization. Did burgeoning democracies influence the medical and surgical professions in the same way as described above?30 Were similar relationships evident under fascism in Italy, or Nazism in Germany, or under Soviet Communism?

Such institutional perspectives on surgeons and their practice should, in addition, induce a reflection on the way in which racial politics functioned in imperial regimes. The prevalence of race as a determining factor of the pragmatic nature of military and medical institutions in India certainly speaks to an acute awareness of difference, broadly defined. In one sense, race operated in an ‘outward-facing’ manner, ensuring that imperial administrators and military personnel, even when the Government of India and the British Government in London employed them, knew whom the ‘others’ were. However, racial politics also operated internally, making the day-to-day functioning of imperial institutions more difficult. These internal products of racial politics also relay much to us about the ways in which governance was acted out, and professional practice curtailed.

A Social History of Surgery and Colonialism

Thus far, our survey of surgery, empire and colonialism has remained at a wide aperture, focused on institutional dynamics generated across British imperial and colonial regimes, and on the changing meaning and transmission of ideas about professionalization and its uses. From this point onwards, that aperture will narrow and focus more closely on historical records that allow us to conceptualize how surgical practice was socially constituted under colonialism, that is: by interactions between different types of people and their competing interests.

Recently there has been a body of work produced in the general history of surgery that investigates the social dynamics surrounding surgical practice, both between practitioners while operating and practitioners and their patients before and after procedures.31 In related sub-fields of the history of medicine, such as the history of medical ethics, the social history of obstetrics and abortion, and the history of psychiatry, these themes have been referenced too.32 A comprehensive social history of surgery under colonialism has yet to be written but, for our purposes here, Sokhieng Au’s work on the relationship between medicine, French colonialism and indigenous Cambodian communities is a useful starting point. Clarifying her book’s position on relations between these interests, Au wrote that, ‘[t]he comparison being made is not between French and Cambodian medicine; it is between concepts of the body, of politics, and of social relations along the fault line of French medical interventions’.33 Au’s multi-faceted approach is useful. She conceptualizes Western medicine as a constituent part of a broader historical social setting and, as a result, she takes into account a number of histories (French, colonial, culture among Cambodia’s indigenous peoples) that played a role in forming how surgery was practiced at that place and time. We can use her work as a model to analyse how, in her own words, the ‘fault line’ of British medical interventions in India played out socially, especially in reference to previously unknown archival material.

Let’s start by looking at the competing epistemologies of health in colonial Madras. The material for this investigation consists of a record of the work of fifty medical practitioners based almost exclusively at the Madras General Hospital (MGH) between 1873 and 1887. Their work was recorded in six casebooks that were later deposited at the Royal College of Physicians Ireland (RCPI), by the sisters of one of their number: Charles Sibthorpe, who was born in Dublin in 1847. After training at the city’s College of Surgeons and College of Physicians, he embarked on a career in India, which saw him rise to the position of Director-General of the IMS in Madras. The six volumes of casebooks within the collection document the treatment of 312 patients from the Presidency’s capital, but also its rural hinterland (mofussil). Venkatachellum, the patient referenced in the introduction, was one of these patients.

Although case records, as other sources too, need to be used critically,34 this collection of sources provides an opportunity to analyse the way in which colonial surgeons negotiated their relations with patients, who could be offered treatment options derived from a number of epistemic origins. In the only case that took place outside the MGH, a number of colonial surgeons travelled to one of the city’s palatial properties, Doveton House, in the Summer of 1882. They were travelling to treat an infamous figure in the recent history of Anglo-Maratha relations: Malhar Rao (1835–1882), the former Gaekwar of Baroda.35 The circumstances of Rao’s deposition came to define his historical significance, but his appearance in the Sibthorpe collection provides new insight into the cultural battlefield that the body, its ailments and possible solutions to those ailments could be.

Sibthorpe, Cockerill, Branfoot and Wylie’s treatment of the ex-Gaekwar was carried out from 30 June to 23 July, when he died ‘of physical exhaustion brought on by his inability to take food due to monomania’.36 They initially found Rao suffering from a case of acute dysentery, and the way in which the surgeons described their competition with Islamic hakims to treat the ex-Gaekwar is of most interest to us here. The case notes recorded that:

great difficulty was found by them in getting him to carry out the treatment. He threw them up for a time and resorted to the treatment of a Mahomedan Hakim who amongst other things gave him powdered peanuts and a powder of a species of marble … Before they left they met in consultation and recorded that the disease had become chronic on the 29th June.37

Further down the same folio, the surgeons detailed that they later prescribed thirty grams of Soda Bicarbonatis, along with ninety grams of an illegible sub-stance, to be divided into ‘six powders’ and ingested twice a day. Whether or not this was the prescription that was competing with the hakim’s recommendation remained unclear.

The passage above is interesting for a number of reasons. For example, it shows how different cultures were layered over one another during these health encounters: we have the former ruler of a Maratha-Hindu dynasty negotiation interactions in a cultural battle between Anglo-European, allo-pathic practitioners, and practitioners of Islamic Unani-Tibb. Second, it exhibits how the professional remit of a surgeon could be stretched and changed depending on the specific demands of a particular case. Although Sibthorpe, for example, trained in surgery, he was asked to act in this instance more as an apothecary and physician.

Furthermore, the surgeons were not only frustrated by the presence of the hakim but, in addition, by the arbitrary and truculent behavior of their patient, and their inability to convincingly show that their pharmacopeia was any more effective than the alternatives being offered. Whether or not being able to give the ex-Gaekwar a succinct appraisal of the pathological origins of his illness would have made any difference in influencing his eventual decision is impossible to say. However, it would appear that Rao’s perception of his various options were relativistic; for him‚ there was nothing to distinguish between the efficacy of powdered peanut or bicarbonate of soda in the treatment of acute dysentery. Interestingly, we must also take into account the importance of individual personalities in mediating the shape of these encounters. Further on in the case notes, the surgeons noted that Rao only believed in the skill and knowledge of one particular IMS surgeon, Mr Simpson. Sibthorpe noted, ‘he did not wish to place himself under my care and expressed a wish that Mr Simpson[,] in whom he had great confidence[,] might be allowed to treat him. Mr Simpson has done so under my orders[,] the ExG[aekwar] believed that the treatment was that of Mr. Simpson’.38 So, although these encounters were battles between medical cultures that represented very different conceptions of healing solutions, they were also mediated by arbitrary factors such as which practitioner a patient was more likely to place their trust in. If similar sources could be found for other colonial locations, one wonders if the same sort of dynamics would present themselves in the practice of colonial surgeons there, too.

Within the collection as a whole, the treatment of the ex-Gaekwar was atypical, in a number of senses. He was a member of the social elite to a greater extent than the vast majority of patients treated; 21% of patients recorded elsewhere in the casebooks were described as various types of ‘coolie’, who worked in cotton mills, or on landed estates (zamindari) or farms. Furthermore, as mentioned above, he was the only patient treated out-side the confines of the hospital, which was a regression to an earlier set of professional circumstances where surgeons would travel outside the institutions they were attached to in order to pursue lucrative work treating wealthy clients.39 However, Rao’s case was similar to the other cases within the col-lection in that the relationship he had with the surgeons who treated him was conditioned by a number of cultural, ethical and epistemological factors.

The surgeons’ framing of Rao’s case was representative of the theoretical and philosophical reflections about the nature of practitioner-patient relations that became more common over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Across our period, there was a growing consensus among practitioners trained and practicing in the Anglo-European world and its colonies that the contours of these relationships were important enough to be explicitly conceptualized. For example, the period represented the birth of a formalized conception of medical ethics; Thomas Percival explicated on the concept in his eponymous volume of 1803. Historians Robert Baker and Laurence McCullough think that Percival’s invocation of the term was the formal beginning of its historical usage, and go as far to claim that ‘anyone who wishes to extend the concept of medical ethics to eras earlier than 1803 needs to demonstrate that this extension makes sense’.40

Over the course of the nineteenth century, and into the twentieth, an ethical sensibility grew among practitioners in line with the currents of professionalization previously described, as well as a proliferation of increasingly specialized technologies that changed the nature of medical practice from ‘individual practice in a competitive private market to [the] integrated general and specialist provision of healthcare’.41 These broad changes induced a proliferation of public discourses, both in terms of print media and political institutions, around the ethical circumstances of medical practice.42

Where do colonial surgeons, and the patients they practiced upon, sit within this broad, evolving context over the course of our period? Bridie Andrews and Andrew Cunningham stated in 1997 that practitioner–patient relationships in imperial and colonial regimes were defined by patients’ submissiveness and their exclusion from ‘the diagnostic or curative processes.’43 However, this static framework leaves no room for discussing archival mate-rial which documents practitioner–patient relationships as being mediated by ethical constructs such as ‘consent’, which in turn were rooted in kinship networks and economic obligations beyond the confines of the hospital.

Let’s look at another example. Between 23 November 1886 and 1 February 1887, the surgeons of the MGH treated Veeraswamy, a Hindu coachman aged 50 who was suffering from a fracture of the leg. After an initial opera-tion, he was offered another operation, although the reasons for this offer remain unclear. Veeraswamy declined, stating that ‘his master had given him a pension and he was satisfied with the result of the operation’.44 The surgeons were content to act in accordance with his wishes, yet again did not note why. They provided him with crutches and a leather kneecap, before discharging him on 1 February.

We can also return to Venkatachellum’s case in this regard. The first operation described above failed and, two months afterwards, the staff of the MGH expressed surprise that ‘no fusion’ had occurred between the bones in his right leg. Therefore, the surgeons believed the best course of action was to amputate the limb, as they believed it would be of no practical use to him, and would be liable to further injury. In much the same manner as Veeraswamy’s case, the surgeons recorded entering into a process of negotiation with Venkatachellum that determined the nature and outcome of his treatment. They wrote, ‘taking all these things into consideration, an operation was decided on, and he was quite willing to consent to it if his relatives had no objection. He therefore went on leave to consult his relatives and returned on the 24th November to have the right limb taken off.’45

Both of these cases show how complex the relationships between surgeons and patients in colonial locations could be at the end of the nineteenth century, and that these complexities operated in a number of ways. We cannot, for example, reduce the practitioner–patient relationship to the practitioner and the patient. Certainly, in the immediate setting of a hospital’s ward those two agents were important in determining the nature of the practice carried out, but socio-economic relations beyond the hospital’s boundaries also determined the nature of that practice across space and time. Sally Wilde has also noted the significance of family and contractual obligations in mediating practitioner–patient relationships for other contexts.46

Furthermore, the invocation of ‘consent’ in these exchanges is interesting, if amorphous. The way in which it was deployed in the case books denoted that some form of verbal exchange had taken place between the surgeons and their patient concerning the best course of action to take. However, it is not clear what consenting to an operation actually meant. Did patients under-stand what was being proposed? Although IMS surgeons were required to be basically proficient in Hindustani, we already know that obtaining such proficiency was not a straightforward task. In addition, how did the surgeons phrase these conversations? Did they use technical language, colloquial English, or search for phrases from native languages to convey the meaning of the procedure? Was there an equivalent formal or informal socio-linguistic con-cept for regulating the administration of healing processes within the com-munities of which they were a part?47 These challenges might have been more pertinent in a colonial location, defined by cultural and ethnic difference, than in a context that shared a viable lingua franca, as in Wilde’s examples. These are all factors contingent on the idea of consent in medicine, but they are very hard to recapture from clinical sources such as the Sibthorpe collection, as there is little context provided for what the word meant. Consent is now a central mediating concept within medical ethics and practice, but we know virtually nothing about its historical origins.48

Summary: Cooperations, Collaborations, and Methodological Lenses

The history of surgery, imperial rule and colonial life is rife for investigation, but must be examined through a number of different lenses. Research needs to be conducted comparatively across colonies and empires, as well as other types of polity, in order to be fully convincing. First, we must take into account the institutional contexts that formed surgeons and their practices. The currency of professionalization in the nineteenth century, for example, was not worth the same in colonial locations as it was in metropolitan locations, and often had to be modified in order to sit congruently with the military, political and economic demands of imperial and colonial governance. These large institutional forces had direct consequences for the ways in which surgeons could practice, and where they practiced. Therefore, the historical linkages between institutional dynamics and the potential they created for practice should be high on any future research agenda.

Furthermore, scholars of different colonial locations and different empires must collaborate in thinking, writing and speaking about these issues. How common, for example, was the invocation of consent as a determinant of the ethics of surgery across empires and colonies at the end of the nineteenth century? If it was common, how did that commonality come about and, if it was not, why did ‘consent’ have more application in some locations rather than others? Furthermore, how did surgeons negotiate the linguistic difficulties in explaining the procedure that was about to take place, and what did the concept of ‘consent’ mean to their patients? Answering these sorts of questions would throw into relief another type of relationship between representatives of imperial governance and those forcibly incorporated into the purview of their power.

Finally, a ‘colonial’ lens, predicated on a history of power mediated through race, is not the only way of analyzing colonial societies and the history of surgery within them. Although race was fundamentally important in determining how colonial governance and its institutions were structured and how they operated, it should not define our research agendas entirely. Might we compare, for instance, the experience of Sibthorpe in treating an Indian elite with a surgeon in Harley Street treating Britain’s provincial elites? Further down the social order, how did practice at the MGH com-pare to equivalent hospitals and their patients in the UK and the USA at the same time? Was consent invoked there and what did it mean? Answering these sorts of questions would necessitate an analysis not only in terms of race, but also in terms of class, which would be an equally fruitful avenue of inquiry. Only when we adopt these wide-ranging and ambitious research agendas will we be able to see the full institutional and social tapestries of imperial and colonial rule and analyse the specific conflicts and tensions that surgery and surgeons had to negotiate.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Royal College of Physicians (RCPI), Case books and other documents of Surgeon-General Charles Sibthorpe from his time in the Indian Medical Service, CS/6, ‘Case book—Madras’, Anon, Venkatachellum (August 1887), no folio numbers. The casebooks are referenced in line with the Chicago Style Manual’s conventions on citing manuscript sources.

- ‘Richard G. H. Butcher, Obituary’, British Medical Journal (BMJ) 1 (28 March 1891): 731.

- Johannes Friedrich August von Esmarch, The Surgeon’s Handbook on the Treatment of Wounded in War, trans. H.H. Clutton (London, 1878), 127–128.

- James A. Salter, ‘On a New Swinging Apparatus for the Treatment of Fracture of the Leg’, Provincial Medical & Surgical Journal 14, no. 22 (October, 1850): 564.

- Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler, ‘Between Metropole and Colony: Rethinking a Research Agenda’ in Tensions of Empire Colonial Cultures in a Bourgeois World, ed. Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler (West Sussex: University of California Press, 1997), 1–59; Antoinette Burton, At the Heart of the Empire (West Sussex: University of California Press, 1998).

- Hormoz Ebrahimnejad (ed.), The Development of Modern Medicine in Non-Western Countries (London: Routledge 2009), especially his introduction, 1–23. Joseph S. Alter (ed.), Asian Medicine and Globalization (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005) and David Westerlund, ‘Pluralism and Change. A Comparative and Historical Approach to African Disease Etiologies’, ed. Anita Jacobson-Widding and David Westerlund, Culture, experience and pluralism: essays on African ideas of illness and healing (University of Uppsala: Uppsala, 1989).

- Biswamoy Pati and Mark Harrison, ‘Introduction’, Medicine and Empire Perspectives on Colonial India, ed. Biswamoy Pati and Mark Harrison (London: Sangam Press, 2001): 1–37.

- John MacKenzie, ‘The British Empire: Ramshackle or Rampaging? A Historiographical Reflection’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 43, no. 1 (2015): 99–124, see 101.

- C.A. Bayly, The Birth of the Modern World, 1780–1914: Global Connections and Comparisons (Oxford: Blackwell, 2004); John Darwin, After Tamerlane: the global history of empire since 1405 (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2008); Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa, 4th edition (London: Abacus, 2011). For the history of Anglophone expansion through the establishment of settler colonies in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, see James Belich, Replenishing the Earth: The Settler Revolution and the Rise of the Angloworld (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009).

- See Thomas Neville Bonner, Becoming a Physician: Medical Education in Great Britain, France, Germany, and the United States, 1750–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Christopher Lawrence, ‘Democratic, Divine and Heroic: The History and Historiography of Surgery’, Medical Theory, Surgical Practice: Studies in the History of Surgery, ed. Christopher Lawrence (London: Routledge, 1997): 1–47, see 27.

- Harold Perkin, The Rise of Professional Society England since 1880 (London: Routledge, 2002), 380.

- See, for example, Trinity College Dublin Manuscripts Department (TCD MD), TCD MSS G3, Dublin University Calendars (1865), 27–28.

- Wilfred Harvey, ‘The Indian Medical Service as a Career’, The Dollar Magazine (n.d.): 1–7 and various editions of The Clongownian, the school journal of Clongowes Wood College, County Kildare. Bodleian Library Oxford (BLO), Per. G.A. Kildare 4E3 (2(1898/1)), The Clongownian (1898), 14.

- Marcus Ackroyd, Laurence Brockliss, Michael Moss, Kate Retford and John Stevenson, Advancing with the Army Medicine, the Professions, and Social Mobility in the British Isles, 1790–1850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 38. For a discussion of similar themes and historical processes see Colin Newbury, ‘Patronage and Professionalism: Manning a Transitional Empire, 1760–1870’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 42 (2014): 193–214.

- For equivalent processes in the IMS see correspondence between Sir Charles Wood, Secretary of State for India between 1859 and 1864, and various influential correspondents. BL APAC, L/MIL/7/154, Indian Medical Service Reorganisation—miscellaneous papers, fos 1–20. For Raffles’ use of Bengal as a blueprint for the civil medical service in Indonesia see Deepak Kumar, ‘Health and Medicine in British India and Dutch Indies: A Comparative Study’ in Alter, Asian Medicine and Globalization, 81.

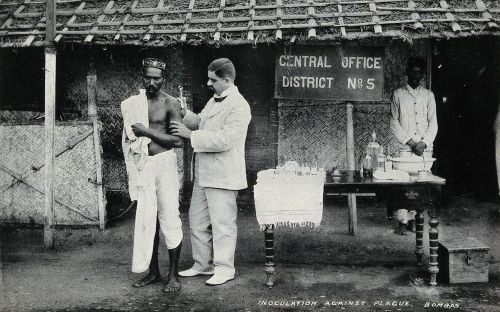

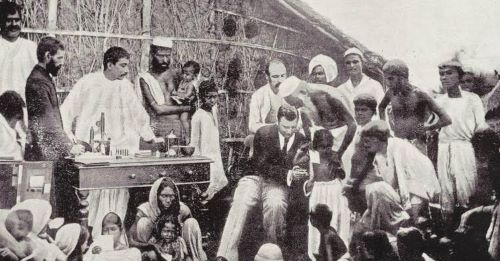

- The most indicative of this was Wood’s correspondence with Spencer Comp-ton Cavendish, the Marquis of Hartington and Viceroy of India. See Charles Wood to Spencer Compton Cavendish, 3 August 1864, BL APAC, IOR/L/MIL/7/14091, no fos. For context see Sanjoy Bhattacharya, Mark Harrison and Michael Worboys, Fractured States: Smallpox, Public Health and Vaccination Policy in British India, 1800–1947 (London, 2005).

- See BLO, RHO 100.42 r.43, Medical Policy in the Colonial Empire Memorandum submitted to the Secretary of State for the Colonies by the Colonial Advisory Medical Committee (London: Colonial Office, 1943).

- Avril A. Powell, ‘Muir, Sir William(1819–1905)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/35144, accessed 8 Feb 2016].

- Report by Sir William Muir concerning the reorganization of the medical staff in India, 3 February 1879, BL APAC L/MIL/7/156, fo 21.

- Ibid.

- See Heather Streets, Martial Races: The military, race and masculinity in British imperial culture, 1857–1914 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2004).

- See BL APAC, L/MIL/7/160, Indian Medical Service Reorganisation Griev-ances of Junior Officers. Application of British rates of pay sanctioned, fos 4–7.

- See Yamuna Kachru, Hindi (Amsterdam: John Benjamins, 2006), 2.

- Principal Medical Officer, Her Majesty’s Forces in India to Secretary to the Government of India, Military Department Calcutta, 5 March 1894, BL APAC IOR/L/MIL/7/189, Indian Medical Service Reorganisation. Passing lower standard Hindustani to entitle officer to receive staff pay, fo 210.

- For the problem of space, see British Medical Journal, 1879, vol. 2, 521, andibid., 1880, vol. 2, 234. For the latter see William Wilfrid Webb, The Indian Medical Service a guide for intending candidates for commissions and for the junior officers of the service (London, 1890), 26.

- M. Anne Crowther and Marguerite W. Dupree, Medical Lives in the Age of Surgical Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

- BL APAC, OIR355.33, Indian Army Lists (1889–1947).

- For the changing composition of the Service, see Syed Hussain Bilgrami’s telegram to the Viceroy of India, Lord Minto, on 24 March 1908. BL APAC, IOR/L/MIL/7/249, Indian Medical Service Reorganization Restriction on Civil Cadre of Indian Medical Service and Revision of Civil Medical Administration (1907–1914), fos 85–90.

- See Kim Price, Medical Negligence in Victorian Britain: the Crisis of Care under the English Poor Law c.1834–1900 (London: Bloomsbury, 2014) and idem ‘Where is the Fault?’: The Starvation of Edward Cooper at the Isle of Wight Workhouse in 1877’, Social History of Medicine 26 (2013): 21–37.

- See Roger Kneebone and Abigail Woods, ‘Recapturing the History of Surgical Practice Through Simulation-based Re-enactment’, Medical History, 58 (2014): 106–121; Sally Wilde, ‘Truth, Trust, and Confidence in Surgery, 1890–1910: Patient Autonomy, Communication, and Consent’, Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 83 (2009): 302–330; Angus H Ferguson, Should a Doctor Tell? The Evolution of Medical Confidentiality in Britain (Surrey: Routledge, 2013).

- On ethics see Robert B. Baker and Laurence B. McCullough, The Cambridge World History of Medical Ethics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008). On obstetrics and abortion see Leslie J. Reagan, ‘About to Meet Her Maker’: Women, Doctors, Dying Declarations, and the State’s Investigation of Abortion, Chicago, 1867–1940’, The Journal of American History 77 (1991): 1240–1264; Simone M. Caron, ‘“I have done it and I have got to die”: Coroner’s inquests of abortion deaths in Rhode Island, 1876–1938’, The History of the Family 14 (2009): 1–18; Judith Walzer Leavitt, ‘The Growth of Medical Authority: Technology and Morals in Turn-of-the-Century Obstetrics’, Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1 (1987): 230–255.

- Sokhieng Au, Mixed Medicines: health and culture in French colonial Cambodia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011) 4. On similar themes, see: Elisabeth Longuenesse, Sylvia Chiffoleau, Nabil M. Kronfol, and Omar Dewachi, ‘Public Health, the Medical Profession, and State Building: A Historical Perspective’, Public Health in the Arab World, ed. Samer Jabbour, Rita Giacaman, Marwan Khawaja and Iman Nuwayhid (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012): 7–21; Poonam Bala, Imperialism and Medicine in Bengal A socio-historical perspective (London: Sage, 1991), especially chapter two; Guy Attewell, Refiguring Unani Tibb Plural Healing in Late Colonial India (Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 2007); Seema Alavi, Islam and Healing Loss and Recovery of an Indo-Muslim Medical Tradition, 1600–1900 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008); Waltraud Ernst, Mad Tales from the Raj the European Insane in British India 1800–1858 (London: Routledge, 1991), 1–17.

- Ortrun Riha, ‘Documents and Sources Surgical Case Records as an Historical Source: Limits and Perspective’, Social History of Medicine 8 (1992); 184–203; Guenter B. Risse and John Harley Warner, ‘Reconstructing Clinical Activities: Patient Records in Medical History’, Social History of Medicine 5 (1992): 184–203; Barbara L. Craig, ‘The Role of Records and Record-Keeping in the Development of the Modern Hospital in London, England, and Ontario, Canada, c. 1890–c.1940’, Bulletin for the History of Medicine 65 (1991): 376–397.

- The term ‘Gaekwar’ was the title used to describe the ruler of Baroda. Its ety-mology derives from the Marathi language, where the word Gaekvād literally means ‘Guardian of the Cows’. For context on why the Gaekwar no longer ruled, see IFS Copland, ‘The Baroda Crisis of 1873–1877: A Study in Governmental Rivalry’, Modern Asian Studies 2 (1968), 97–123.

- RCPI, CS/5, ‘Case Book—Madras’, Surgeons Sibthorpe, Branfoot, Wylie, Simpson and Cockerill, Malhar Rao (June–July, 1887), fo 28(a).

- RCPI, CS/5, Malhar Rao, f. 22.

- RCPI, CS/5, Malhar Rao, f. 23.

- See Ackroyd etal., Advancing with the Army, chapter four on patronage net-works in late Georgian and early Victorian Britain.

- Baker and McCullough, The Cambridge World History, 3.

- Ferguson, Should a Doctor Tell?, 4.

- See reporting on ‘medico-legal notes and queries’ in the British Medical Journal, which became a recurrent section in February 1883, although the phrase ‘medico-legal’ had been deployed in the journal since 1842.

- Andrew Cunningham and Bridie Andrews, ‘Introduction: Western Medicine as Contested Knowledge’, Western Medicine as Contested Knowledge, ed. Andrew Cunningham and Bridie Andrews (Manchester: Manchester University Press 1997), 1–23, see 6.

- .RCPI, CS/6, Anon, Veeraswamy (Nov. 1886–Feb. 1887), fo. 32.

- RCPI, CS/6, Anon, Venkatachellum, no fos.

- Wilde, ‘Truth, Trust and Confidence in Surgery’, 302–330.

- Among the Xhosa people in Britain’s south African colonies, the equiva-lent verb for ‘consent’ was vuma. See David Gordon, ‘A Sword of Empire? Medicine and Colonialism at King William’s Town, Xhosaland, 1856–1891’, Medicine and Colonial Medicine, ed. Mary P. Sutphen and Bridie Andrews (London: Routledge, 2003): 43.

- Martin S. Pernick wrote one article on the social history of ‘informed con-sent’ in 1982. See Martin S. Pernick, ‘The Patient’s Role in Medical Decision-Making: A Social History of Informed Consent in Medical Therapy’, Making Health Care Decision: The Ethical and Legal Implications of Informed Con-sent in the Patient-Practitioner Relationship, 3 vols, vol. 3 (New York, 1982): 1–36. A good general introduction to the concept of ‘informed consent’ is Peter B. Terry, ‘Informed Consent in Clinical Medicine’, Chest 131 (2007): 563–568. In historical scholarship see Paul Weindling, Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials: From Medical War Crimes to Informed Consent (Basing-stoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

Further Reading

- Ackroyd, Marcus, Laurence Brockliss, Michael Moss, Kate Retford and John Stevenson. Advancing with the Army Medicine, the Professions, and Social Mobility in the British Isles, 1790–1850. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

- Au, Sokhieng. Mixed Medicines: Health and Culture in French Colonial Cambodia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2011.

- Belich, James. Replenishing the Earth: The Settler Revolution and the Rise of the Angloworld. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Bonner, Thomas Neville. Becoming a Physician Medical Education in Great Britain, France, Germany, and the United States, 1750–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Cooper, Frederick and Ann Laura Stoler. ‘Between Metropole and Colony: Rethinking a Research Agenda’. In Tensions of Empire Colonial Cultures in a Bourgeois World, edited by Frederick Cooper and Ann Laura Stoler, 1–59. West Sussex: University of California Press, 1997.

- Crozier, Anna. Practising Colonial Medicine: The Colonial Medical Service in British East Africa. London: IB Tauris, 2003.

- Darwin, John. After Tamerlane: The Global History of Empire Since 1405. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2008.

- Ebrahimnejad, Hormoz. ‘Introduction’. In The Development of Modern Medicine in Non-Western Countries, edited by Hormoz Ebrahimnejad, 1–23. London: Rout-ledge, 2009.

- Pati, Biswamoy and Harrison, Mark, Eds. Medicine and Empire Perspectives on Colonial India. London: Sangam Press, 2001.

- Perkin, Harold. The Rise of Professional Society England since 1880. London: Routledge, 2002.

Chapter 18 (369-386) from The Palgrave Handbook of the History of Surgery, 12.17.2017, published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.