The battle of Marathon was a success for the Athenians, which stimulated their growing confidence.

By Dr. P. J. Rhodes

Late Professor of Ancient History

Durham University

So much has been written about the battle of Marathon,1 from so wide a range of viewpoints, that I was probably not the only contributor here to have thought despairingly that it would be difficult to say anything worthwhile about Marathon which has not been said already by somebody somewhere. In the end that provided me with the subject for my paper, and I should like to look at the wide range of scholarly investigations which has been prompted by the battle of Marathon.

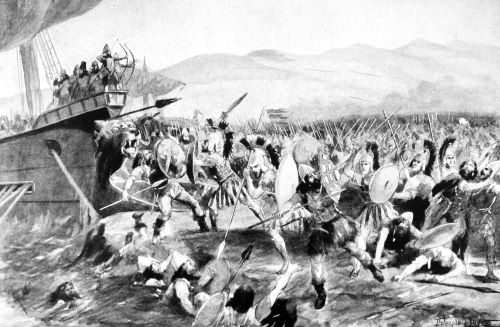

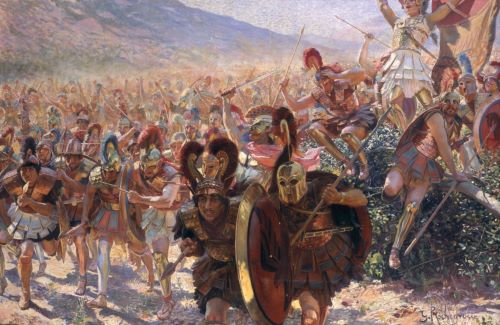

Marathon has inevitably attracted military historians, interested in how the Athenians succeeded in defeating the Persians and what the consequences of their success were. It is worth mentioning one unusual publication, a paper by N. Whatley which was written for a meeting in Oxford in 1920 but not published until 1964, which took Marathon as a test case for asking more generally how, and how far, we can reconstruct what happened in ancient battles, and criticizing some over-confident reconstructions which were prevalent in the early twentieth century.2 J. F. Lazenby in a fairly recent book on the Persian Wars has doubted the attribution to the Athenians of clever strategy and tactics, better discipline than the Persians or even the effect of belonging to a free state fighting for its freedom, and prefers to think of a victory won by ‘militiamen through sheer guts and chance’.3 The 2,500th anniversary has already prompted two new books, and there may be more on the way: R. A. Billows, Marathon: How One Battle Changed Western Civilization,4 and P. Krentz (one of the other contributors to this volume), The Battle of Marathon,5 each of them considering both the campaign of 490 and the battle of Marathon and also the wider context. Billows has a new interpretation of the generals’ disagreement, and Krentz puts forward new suggestions as to why, where, and how the actual battle began, which I shall mention below.

Beyond that, I begin with the written sources: overwhelmingly Herodotus, some tantalizing passages in later texts, some intriguing inscriptions. A. W. Gomme notoriously began his article on ‘Herodotos and Marathon’6 with the sentence, ‘Everyone knows that Herodotos’ narrative of Marathon will not do’ – because Herodotus did not know about warfare; he was not always careful to scrutinize what his informants told him; and there are inconsistencies, over the Persian cavalry, the Athenian generals and polemarch, and the delay before the battle and the ending of that delay, which mean that his narrative cannot be accepted as it stands. Herodotus is more sympathetically regarded now than he was half a century ago, but I think it is undeniable that there are some difficulties in Herodotus’ account of Marathon. At two particular points Gomme invoked later sources to solve a problem; and, while agreement is as far away as ever, I think he was right on both those points. (a) An Athenian decree proposed by Miltiades, to march out from Athens and face the Persians,7 is one of a whole series of fifth-century Athenian documents for which we have no fifth-century evidence but which are attested from the fourth century onwards. I am on the side of those who believe them to be not original documents rediscovered in the fourth century but fourth-century reconstructions8 – that does not mean baseless inventions, but we cannot tell how much genuine information lies behind them. But I agree with Gomme that the disagreement over whether to fight immediately or to wait, which Herodotus locates at Marathon, makes much better sense as a disagreement in Athens over whether to go and confront the Persians at Marathon or to stay and defend the city.9 (b) Herodotus’ account of why after some days the armies’ delay at Marathon ended and the battle was fought, though we should have expected the Athenians to continue waiting until the Spartans arrived to support them, is that the generals were taking it in turn to preside, a day at a time, but although Miltiades’ supporters were willing to yield to him on their days he waited until his own day had come and fought then.10 An entry in the Suda, χωρὶςἱππεῖς, and a passage in Nepos’ Miltiades point to a more credible explanation – that the Persians had re-embarked their cavalry as a first step towards sailing to Phalerum and attacking the city before the Spartans arrived, and the Athenians got to know of that.11

Another question to which Herodotus does not give a sufficient answer is why the Persian forces landed at Marathon, rather than sail to Phalerum, from which they could attack the city of Athens directly. His overt explanation is that that was the most suitable area in Attica for cavalry, and that it was close to Eretria.12 In fact the plain between Phalerum and the city was equally suitable for cavalry. Nearness to Eretria probably counts for something, and we can add that the Persians would have been able to sail quickly from Eretria to Marathon and disembark before the Athenians could send a substantial force to oppose them there; but it is normal to see significance in the statement which Herodotus adds to his overt explanation, that the ex-tyrant Hippias, who was with the Persians, led them to Marathon. Eastern Attica was the Pisistratids’ home territory, where Hippias would have the best chance of finding supporters, and Pisistratus had sailed from Eretria to Marathon and advanced on Athens from there when he seized power for the last time c. 546.13

I remarked above that Herodotus is more sympathetically regarded now than he was half a century ago. Modern approaches to literature, through such studies as narratology, have made us more aware than our predecessors that an ancient writer can be trying to do various other things in addition to, or indeed instead of, straightforwardly giving the facts. I think this has made us more willing than scholars of earlier generations to accept what the transmitted text says and try to make sense of it, rather than to say dismissively that the text must be corrupt, or else the writer thought he was telling the truth but got it wrong. Sometimes, writers have not been allowed to get it wrong. Just as the great philologists of the past knew what was good Greek, and when the manuscripts gave them something which they could not accept as good Greek they emended the text to produce something more satisfactory, so the great historians of the past knew what the truth must have been, and when the manuscripts gave them something which they could not accept as true they likewise emended the text to produce something more satisfactory. H. B. Rosén in the new Teubner edition of Herodotus has tried to free the text from linguistic ‘improvements’, D. Asheri was equally anxious to free the text from historical ‘improvements’, and D. Gilula has given examples from books 8-9 of irresponsible emendations which have remained accepted for too long.14

I do not think Herodotus’ account of Marathon has been distorted by wild emendations, but there have certainly been scholars who went much further than Gomme in thinking that they knew better than Herodotus what had been planned and what had happened. One of the most drastic was J. A. R. Munro, first in a series of articles and later in his treatment of the Persian Wars in the first edition of the Cambridge Ancient History.15 In his 1899 article on Marathon he supposed that the Persians’ reason for landing at Marathon rather than Phalerum was to lure the Athenian army away from the city; half of the Persian force was to stay there and keep the Athenians pinned down, while the other half with Hippias, in collusion with the Alcmaeonids in the city, was to sail round to Phalerum and the city would then be betrayed to it. This relies on Nepos’ statement that half of the Persian infantry took part in the battle.16 Miltiades got to know of the Persian plans and (thanks to χωρὶςἱππεῖς) he also got to know when the Persians were embarking the half which was to sail round to Phalerum, and he attacked then. Later, in the Cambridge Ancient History, Munro went far beyond that in departing from what Herodotus says: the Persians divided their forces from the beginning, with Datis landing at Marathon while Artaphernes attacked Eretria; the Athenian army was on its way to support Eretria but turned aside to Marathon when it learned that Datis had landed there; the fall of Eretria left Artaphernes free to sail to Attica, so the Athenians at Marathon then had to attack without waiting for the promised help to arrive from Sparta. In this version Munro did not even accept the standard date for the battle, late summer 490/89,17 but moved it from the archonship of Phaenippus to late summer 491/90, on the basis of intervals given in some texts between Marathon and other events.18 As Burn pointed out, not only is that theory suggested by no source, but it is unthinkable that the Athenians would have considered sending their full army outside Attica to support Eretria, thus leaving Athens itself vulnerable to attack.19

More recently a Norwegian scholar, J. H. Schreiner, has included Marathon among the fifth-century topics on which he has written revisionist studies relying particularly on the later sources.20 He conjures up two battles at Marathon, the first near the Greek camp, in which the Greeks defeated a Persian attack, and the second some days later, when most of the Persians had re-embarked and the Greeks at night attacked and defeated the Persians left on land, after which it was the Athenian navy which prevented the Persians from landing at Phalerum. But it is not satisfactory to put together odd passages from different places and to suppose that they are surviving fragments from a single true account which proves the account of our main fifth-century source to be untrue.

Munro apart, 490/89 has been accepted as the year of the battle, but there has been a problem over the exact date. According to Herodotus, the Athenian runner arrived in Sparta on the ninth day of the month, to be told that the Spartans could not march out until the full moon (which if the calendar was not out of step with the moon would have been on the fifteenth).21 Plutarch in his essay On the Malice of Herodotus complains that the Spartans frequently did not wait until the full moon (failing to realize that this might be a taboo applying specifically to the celebration of the Carnea, in the second quarter of the month Carneius), and that the battle was fought on 6 Boedromion (the third month of the Athenian year), so that waiting for the full moon ought not to have held the Spartans back.22 The solution commonly adopted is that 6 Boedromion was the date not of the battle but of the subsequent commemoration, chosen because the sixth of the month was sacred to Artemis, and that the battle was actually fought about the middle of the previous month, Metageitnion; Metageitnion is equated with Carneius elsewhere by Plutarch.23 If the Athenian and Spartan calendars were both in step with the moon – and we have to admit that that may not have been the case – there is a further problem, because in 490 there was a new moon immediately before the summer solstice, which might have been correctly detected and assigned to 491/90 or might have been incorrectly considered to be the first new moon of 490/89. If it was correctly detected, then the full moon of Carneius/Metageitnion should have been in the middle of September, and it is hard to think that so much of the year had already been used up that the battle of Marathon was not fought until then. If that new moon was wrongly considered to have occurred after the solstice, then the full moon of Carneius/Metageitnion, and the battle of Marathon, would have fallen in the middle of August, and that solution is often preferred.24

There is a wider chronological problem concerning the events leading up to the campaign of 490. Herodotus in book 6 continues beyond the Ionian Revolt to Mardonius’ campaign of 492 and Darius’ ultimatum to Thasos in 491; he then mentions Darius’ sending heralds to demand the submission of the Greeks; and that leads to a complex story involving Athens, Sparta, and Aegina; after which he turns to the campaign of 490.25 Most scholars have thought that there are too many events in the story of Athens, Sparta, and Aegina to be accommodated between the summer of 491 and the summer of 490, and often it has been suggested that many of those events occurred in the early 480s, after the battle of Marathon.26 That is not what the reader of Herodotus would expect, and N. G. L. Hammond defended Herodotus’ placing of the story in 491/90, reckoning that all the events could be accommodated with some months to spare.27 I agree with Hammond that what Herodotus narrates before Marathon should have happened before Marathon, but I find it hard to accept that everything happened within a year. A better solution was suggested by Forrest, as a brief aside in an article about another matter, and I have championed it more recently – that when Herodotus mentions Darius’ heralds to Greece he is backtracking but fails to make that clear, that Darius’ heralds were sent not in 491/90, just before the campaign of 490, but in 493/92, just before Mardonius’ campaign of 492.28 This will allow time for the whole sequence of events to be completed before the Marathon campaign.

It will also mean that, whether or not it was hoped that Mardonius would reach central and southern Greece, Darius already had central and southern Greece in his sights – and that I am happy to believe. As Herodotus says in connection with Mardonius’ campaign, Eretria and Athens, which had supported the Ionian Revolt, were the proschēma for the campaign (as they were clearly the principal targets of the campaign of 490), but Darius wanted to overcome as many as possible of the Greek cities (and his heralds were sent to various cities in the islands and in mainland Greece).29

Modern scholars like numbers, but they often dislike the numbers which they find in ancient texts. For the forces engaged at Marathon Herodotus does not give totals apart from the Persian fleet of 600 triremes, which seems to be his standard figure for a Persian fleet.30 Later sources give the number of soldiers on the Athenian side as 10,000, including or excluding 1,000 from Plataea,31 and whatever its basis a total of that order seems credible. On the Persian side the lowest figures are those of Nepos – 500 ships, 200,000 infantry (100,000 engaged in the battle: cf. above) and 10,000 cavalry – but that is far too many, and modern scholars tend to assume c. 20,000.32 Herodotus does give the number of dead: 192 Athenians and 6,400 Persians.33 The disproportion is credible for a battle in which hoplites were fighting at close quarters against light-armed troops, and 192 is likely to be the actual number of Athenian bodies collected and buried at Marathon, but how was the Persian figure of 6,400 arrived at? Is it significant that 6,400 is exactly 33⅓ times 192?34 As for the suggestion that the Athenian dead hoplites reappear as the horsemen on the Parthenon frieze,35 I fear that if it had not been made by so eminent a scholar that would never have been taken seriously.

The run to Sparta by Philippides or Phidippides of 140 miles/225 km in two days seems not to have been an exceptional achievement.36 Plato’s claim that Sparta’s reason for not responding immediately was that it was fighting against the Messenians had some supporters half a century ago, and has still not been entirely abandoned, but the evidence adduced in its support is not compelling, and I think it is much more likely that this was an explanation invented in the fourth century when the religious explanation of the early fifth no longer seemed so credible.37 A second run, from Marathon to Athens after the battle to announce the victory, on which the modern Marathon race has been modelled, appears to have entered the tradition by the fourth century, but it is only Lucian who attributes that also to Philippides.38

The inscriptions, as I have said, are intriguing. One is what is restored as the dedication of Callimachus the polemarch,39 beginning [Καλίμαχοςμ ̓ἀν]έθεκεν(‘Callimachus dedicated me’) – but Callimachus was killed in the battle, so he cannot have set up a dedication after it. If the restoration is right, the least difficult explanation is that before the battle he vowed a dedication and after the battle his family set it up in his name; another suggestion is that ll. 1-3 are a Panathenaic dedication by Callimachus, to which ll. 4-5 were added after his death at Marathon. In any case, this dedication reminds us that the story of the battle which we have is Miltiades’ story, and if Miltiades had been killed and Callimachus had not we might have had a different story. For Miltiades himself we have to go to Olympia, where the Miltiades who dedicated a helmet to Zeus is generally accepted as the Miltiades of Marathon, though that dedication perhaps belongs to an earlier stage in his career.40

Then there is a series of epigrams which commemorate some achievement in the Persian Wars,41 but which battle or battles – Marathon, or Salamis, or what? This problem was transformed by the discovery of another block of stone from the same monument, in 1987: most recently A. P. Matthaiou has argued that the monument was a cenotaph for the dead of Marathon, set up in Athens as the counterpart of the monument at Marathon, but A. Petrovic ́ has claimed that it commemorated the Athenian dead from all the battles of 490 and 480-79.42 A new Marathon epigram with part of the casualty list of the tribe Erechtheis has recently been found in the Peloponnese and published, and Petrovic ́discusses that here.43 One other text certainly concerns Marathon but there has been a problem concerning the building with which it is associated: a base adjoining the Athenian treasury at Delphi held Athenian dedications from the battle of Marathon.44 Pausanias states that the treasury was built from the spoils of that victory;45 several archaeologists have thought that the treasury is older than the base, while others think that Pausanias is right after all.

An interesting contribution to the background of the Marathon campaign has been made by one of the clay tablets from Persepolis, the Persians’ equivalent of the Linear B tablets from Mycenaean Greece. Darius notoriously gave high appointments only to Persians, whenever possible men related to himself or to one of the six men who had supported him when he seized power in 522, but there is a notable exception in one of the two commanders of the campaign of 490: Datis the Mede.46 We still do not know how Datis managed to rise so high under Darius, but we do now know that this was not his first encounter with the Greek edge of the Persian Empire. The tablet shows him returning to the King after a visit to Sardis, in January/February 494, shortly before the fall of Miletus and the final suppression of the Ionian Revolt. It is possible that he then returned to Asia Minor, and that his attack on Rhodes mentioned in the Lindian Temple Chronicle belongs to 494 and not to 490.47

Can we also invoke numismatics? Some time in the early fifth century the designs of Athens’ ‘owl’ coinage were modified by the addition of an olive crown to Athena’s helmet and a lunar crescent to the reverse. Some have seen this as a commemoration of Marathon; others have thought of Salamis, but detecting connections between changes in coinage and known historical events is a risky business. The sober Kraay was prepared to envisage only some connection between the modernized coinage and the revived Athens after the Persian Wars.48

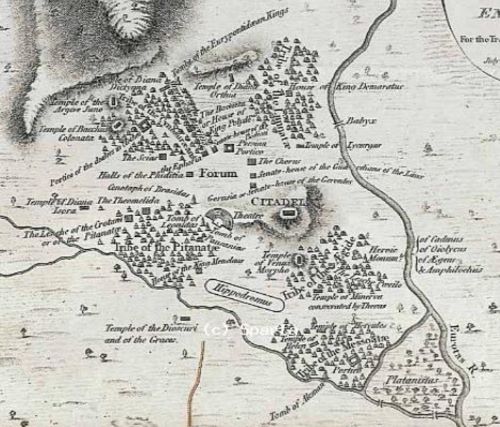

Marathon has provided ample opportunity for topographical investigation and argument.49 It is generally accepted that the Persian camp was at the north-east end of the plain and the Athenian camp at the south-west end,50 but where exactly was the Athenian camp and where exactly was the battle fought? Presumably neither the camp nor the battle should be located inside the village, but the position of that has been disputed too. The camp was at a sanctuary of Heracles: for that, scholars were divided for a long time between a site near the coast and a site some distance inland, but it has come to seem increasingly certain that the coastal site is right for the Heracleum.51 An inland site towards Vrana which was thought to be the most likely site for the village is now identified with Probalinthus, and the best site for the village of Marathon now seems to be Plasi, near the coast northeast of the soros.52 The soros where the Athenians were buried is itself near the coast north-east of the Heracleum,53 and it has usually been thought that the battle was fought near there. Pausanias mentions a separate tomb of the Plataeans and slaves, and for a time it was thought that a tomb 1½ miles/2.5 km to the west of the soros was this tomb, and that the soros and this tomb gave the positions of the Athenians’ right and left wings. However, further work has not made that identification certain, though it is still accepted at the Marathon museum, and more probably Pausanias’ second tomb was a mound seen in the nineteenth century but no longer extant.54 A painting in the Stoa Poikile showed fleeing Persians falling into a marsh,55 and this will be the ‘great marsh’ which was in the north-eastern half of the plain until it was drained in the twentieth century; the ‘little marsh’ at the south-western exit from the plain, also drained in the twentieth century, probably did not exist at the time;56 and the charadra, the stream from the hills which now crosses the plain, is not mentioned in any account, and presumably then it either did not exist or followed a very different course, or else in late summer it was so dry that it was not a significant obstacle.57 E. Vanderpool rediscovered the remains of a monument seen by W. M. Leake and others in the nineteenth century near the Mesosporitissa chapel at the west end of the marsh, about 2 miles/3 km north-east of the soros, and reaffirmed Leake’s identification of this with the ‘trophy of white stone’ mentioned by Pausanias.58 Sekunda and Krentz both think this rather than the soros is the best indication of where the battle was fought.59

One other topographical issue needs to be mentioned, the route between Athens and Marathon. Almost everybody has assumed that the natural route then was the route of the main road now, passing between Hymettus and Pentelicon at Pallene and then following the coast northwards to Marathon, a distance of about 25 miles/40 km. Hammond, notorious for his physical prowess, preferred a shorter route through the hills via Cephisia, about 22 miles/35 km;60 but for a large body of men the easier route was surely preferable. If the coastal location of the Heracleum is correct, the Athenian camp will have directly covered the exit from the plain to the coastal route, and to reach the beginning of Hammond’s route the Persians would have had to pass in front of the Athenian camp.

I turn now to Sachkritik, questions about practicalities and what we can believe might actually have happened. I remarked above that I agree with Gomme, that disagreement among the Athenians is more likely to have occurred in Athens, over whether to go to Marathon or stay in the city, than at Marathon, over whether to fight or not. At Marathon the Athenians were waiting for support from Sparta, the Persians were waiting for Hippias to bring about the betrayal of Athens:61 what needs to be explained (and Herodotus explains only by Miltiades’ waiting for his own day) is why the battle was fought when neither of those things had happened, and χωρὶςἱππεῖς gives us a way to achieve that explanation.

If, as most people believe, the battle was fought towards the Athenians’ end of the plain, then although the Athenians attacked the Persians, the Persians must in some sense have made the first move, advancing towards the Athenian camp,62 perhaps to challenge the Athenians to battle as perhaps they had done on previous days also; perhaps to cover the beginning of their re-embarcation. The Athenians decided to fight. According to Herodotus, they weakened their centre in order to make their line as long as the Persians’ line, they advanced δρόμῳ (‘at a run’) for 8 stades (rather less than 1 mile/1.5 km), and then, as Miltiades had hoped, while the Persians drove back the weakened centre the wings closed in on them.63 It is often, but not always, thought that the weakened centre was a deliberate trap into which the Persians fell.64 The Athenian advance prompts questions about what is physically possible. It has long been suspected that heavily-laden Greek hoplites could not advance at a run for 8 stades:65 Grundy wrote of ‘the quick step’;66 and I have once in Britain seen a light infantry fast march, but that was by light infantry, and I do not know over what distance even they could sustain it. Elsewhere δρόμῳ does not always mean ‘at a run’: Thucydides uses it of Brasidas’ ‘forced march’ through Thessaly to the north.67 More recent investigations were thought to have confirmed that 8 stades at a run would be impossible for hoplites:68 either the ‘run’ was Grundy’s ‘quick step’ or – the other possibility which Grundy considered and which the recent investigations favoured – the men did not break into a run until they came within range of the Persians’ arrows.

However, Krentz in his new book argues the battle was fought further to the north-east, near the trophy and the marsh, so that it was the Athenians who made the first move. He argues that Miltiades did wait for the day when he held the chief command, that his plan was to attack the Persians’ infantry before their cavalry could deploy into the plain (Krentz does not accept χωρὶςἱππεῖς), and that the hoplites at Marathon were not as heavily armed as has regularly been believed, and could have run 8 stades after all (though he thinks ‘jog’ a better term than ‘run’).69

According to Herodotus the battle lasted a long time,70 yet scholars have sometimes tried to crowd a great deal of further activity into the same day:71 the Persians collected their Eretrian prisoners from the island of Aegilia where they had deposited them, and sailed round to Phalerum, hoping to reach the city before the Athenian army could return to defend it, but the Athenian army hurried back by land and had already reached Cynosarges, to the south-east of the city, when the Persians arrived. The notorious signal given by means of a shield is said to have been given when the Persians were already on board their ships.72 Hammond reckoned that such a signal could not have been given later than about 9 a.m.; so the long battle must have started soon after sunrise about 5.30 a.m., and the Athenian army could have begun its journey between 9 and 10 a.m. and have reached Cynosarges before sunset about 6.30 p.m. (he himself had walked from Athens to Marathon by a particularly arduous route in six hours and then, suitably tired, back in seven hours). He thought the Athenians’ march would have taken about eight hours, and the Persians’ voyage about nine hours.73 He was splendidly dismissive of early twentieth-century scholars who thought that neither the Persians’ voyage nor the Athenians’ march could have been accomplished on the day of the battle.74 However, it seems that the earlier caution was justified. (a) We do not know where the signaller was positioned (or, of course, what message the signaller was conveying), and in any case even some kind of flashing signal could have been given at any time during the hours of daylight.75 (b) Conditions are not likely to have been ideal both for the first half of the Persians’ voyage, southwards to Sunium, and for the second half, north-westwards to Phalerum; the voyage could well have taken as long as 30-45 hours.76 The battle need not have been begun and ended early in the morning, and, however well informed the Persians may or may not have been, the Athenians ought to have known that the Persians could not reach Phalerum on the day of the battle.

There are also political questions of various kinds which arise in connection with the battle of Marathon. Among recent writers R. Osborne is not much interested in military history, but he had to include the Persian Wars (albeit very briefly) in his book on archaic Greece, Greece in the Making.77 He does say that ‘Marathon was crucial militarily for the whole of Greece’, but he continues, ‘but this should not overshadow its massive political importance at Athens and at Sparta’. Of the Persian Wars in general he says, ‘We can have little confidence that we can satisfactorily answer any of the questions which the Greeks themselves answered. Too much was invested in antiquity in answering the question of how the Greeks beat the Persians for us to be able to disembed truth from partial tradition. What we can do is to exploit the tensions between competing traditions, and by doing so throw light on the nature of city-state politics in these years, and hence on the classical legacy left by the war’.

The traditional commander of the Athenian army was the polemarch, one of the nine archons, though stratēgoi (‘generals’) may have been appointed ad hoc for some particular campaigns.78 Ten annual generals, one from each tribe, were instituted by Cleisthenes in 508/07 and first appointed in 501/00.79 The battle of Marathon was an exceptional occasion, with a large enemy force invading Attica and the whole Athenian army going out to confront the enemy. All ten generals and the polemarch went with the army: what was their standing relative to one another?

Even later, when the principle of one general per tribe was modified, the ten generals were theoretically equal, with the unique exception of 407/06, when all our sources agree that Alcibiades was made supreme commander.80 Ath. Pol. in reporting the institution of the ten generals adds ‘the polemarch was the hēgemōn of the whole army’ (22.2: τῆςδὲἁπάσηςστρατιᾶςἡγεμὼνἦνὁπολέμαρχος). In Herodotus’ account of Marathon the generals are clearly the effective commanders of the army: they sent the runner to Sparta, they led the army out to Marathon, they disagreed about what to do after arriving at Marathon.81 To resolve that disagreement Miltiades brought in Callimachus the polemarch, who had an eleventh vote (ἦνγὰρἑνδέκατοςψηφιδοφόρος), for in the past (τὸπαλαιὸν) the Athenians made the polemarch an equal voter (ὁμόψηφος) with the generals, and with his support Miltiades obtained the decision to fight.82 I have mentioned above Herodotus’ claim that the generals presided in turn, a day at a time, and those who agreed with Miltiades offered to yield to him but he awaited his own day to attack.83 I do not think that is the right explanation of why the battle was fought when it was, but I can believe that on this occasion the generals did agree to preside in turn in that way.84 In the battle Callimachus the polemarch was in the commander’s position on the right wing, ‘for that was then the nomos for the Athenians’.85

I noted above that the story of Marathon which we have is Miltiades’ story, and that Callimachus’ story might well have been different. But Herodotus gives a detailed, consistent, and credible account, which I think is correctly expounded by Hammond as modified by Badian.86 The ten generals were from their institution not commanders of their tribal regiments subordinate to the polemarch but the effective commanders of the army. At the time of Marathon the polemarch remained titular commander-in-chief, he had an equal vote with the generals (Herodotus’ τὸπαλαιὸν refers to that time, not to some earlier time), and in the battle he occupied the traditional commander’s position on the right wing (and this will be what Ath. Pol. means by ἡγεμὼν); but after Marathon the polemarch is never found with the army again. Herodotus has Callimachus appointed by lot, whereas in Ath. Pol. the archons were elected until κλήρωσιςἐκπροκρίτων was reintroduced in 487/86, and Pausanias has Callimachus elected.87 Either Herodotus has carelessly misapplied later practice or at the time of Marathon the nine archons as a body were elected but which of them was to take which post was decided by lot.

Another political question which arises in connection with Marathon concerns the shield signal. Herodotus reports that the Alcmaeonids were considered to be responsible for it, and later he returns to the subject, arguing that the Alcmaeonids cannot have been responsible, because they were conspicuously hostile to the tyranny and so could not have wanted a Persian victory and the reinstatement of Hippias. A shield signal certainly was given, but Herodotus cannot say who was responsible.88 However, Herodotus’ argument is not enough to absolve the Alcmaeonids. His own narrative shows that in Pisistratus’ rise to power there was one stage in which Megacles the Alcmaeonid cooperated with him, until Pisistratus refused to father a child by Megacles’ daughter.89 Although Herodotus seems to have thought that the Alcmaeonids were in exile continuously from Pisistratus’ final seizure of power to the expulsion of Hippias,90 a fragment of the inscribed archon list has shown that Cleisthenes was archon in 525/24.91 The Alcmaeonids were not opposed to the Pisistratid tyranny throughout its existence. When the institution of ostracism began to be used in the 480s, the first three victims were Hipparchus son of Charmus, probably a grandson of Hippias; Megacles the Alcmaeonid; and what Ath. Pol. calls another ‘friend of the tyrants’.92 Other men voted against in the 480s include two further Alcmaeonids, Hippocrates and Callixenus, and one of the ostraka against Callixenus calls him [πρ]οδότες (‘traitor’).93 It seems that, whatever Cleisthenes’ intentions may have been when instituting ostracism, the first use of it was to attack men with Pisistratid and Alcmaeonid connections after Marathon. The Alcmaeonids may not have been collaborating with the Persians, but the suspicion that they were collaborating was not something produced later but contemporary, and that shows that they were at any rate not so conspicuously anti-Persian in 490 as to make the suspicion untenable. A. Ruberto in a recent article has placed this in context as one of a number of indications that in the late sixth and early fifth centuries some Athenians on some occasions were willing to come to terms with the Persians.94

Yet another political question concerns the rival claims of Marathon and Salamis as Athens’ two great achievements against the Persians. In the 470s the two most prominent Athenians were Cimon, the son of Miltiades, and Themistocles, the man responsible for Athens’ enlarged navy and for the victory at Salamis in 480. Cimon and Themistocles were rivals in various respects, and the rivalry ended with Themistocles first ostracized and then fleeing as an exile to the Persians, and Cimon remaining predominant until the end of the 460s. It seems likely that one aspect of their rivalry was pressing the claims of Marathon, Miltiades, and the hoplites, and Salamis, Themistocles, and the navy. Aeschylus’ Persians was produced in 473/72, when Themistocles was under attack, and its choregos was Pericles, who became Cimon’s principal opponent later. The play can be read on various levels, and I do not think one reading should be adopted to the exclusion of the others; but this play focuses on Salamis and the message to Xerxes which brought the battle about, though without mentioning Themistocles by name. One possible reading of it which has been championed is to see it as a contribution to that debate, advancing the claims of Salamis and Themistocles against those of Marathon and Miltiades.95

In the comedies of Aristophanes warlike old men are veterans of Marathon;96 and legends were soon attached to the Marathon campaign. Already in Herodotus we read that the Athenian runner had an encounter with Pan in the mountains of Arcadia, and that in the battle an Athenian called Epizelus was blinded by an apparition of a mighty warrior, who killed the man positioned beside him.97 An epiphany of Theseus during the battle was included in the painting in the Stoa Poikile; and, centuries later, Pausanias recorded that, and also wrote of the sound of horses whinnying and men fighting which could still be heard at night, of the troughs from which Artaphernes’ horses had drunk, and the marks of his tent on the rocks, and of the hero Echetlus who had appeared and had killed many of the barbarians with a ploughshare.98

As for the Persians, we know that after this setback at the north-western corner of their empire in 490 they returned with much larger forces in 480-79, and that after a further setback then they never invaded Europe again, though the Greeks surely expected them to do so. Apart from that, we have a Persian response to Salamis conjured up by Aeschylus in his Persae in 472, but it was left to writers of the Second Sophistic to imagine the Persians’ response to Marathon. Dio Chrysostom suggested that they represented Marathon as an accidental sequel, involving not more than twenty ships, to their successful campaign against Naxos and Eretria, and Aelius Theon of Alexandria gave as an example of prosopopoiïa what Datis would say to the King after Marathon (but did not suggest what that might be).99 The twentieth-century British poet Robert Graves also imagined a Persian response to Marathon:

Truth-loving Persians do not dwell upon

The trivial skirmish fought near Marathon.

As for the Greek theatrical tradition

Which represents that summer’s expedition

Not as a mere reconnaissance in force

By three brigades of foot and one of horse

(Their left flank covered by some obsolete

Light craft detached from the main Persian fleet)

But as a grandiose, ill-starred attempt

To conquer Greece – they treat it with contempt;

And only incidentally refute

Major Greek claims, by stressing what repute

The Persian Monarch and the Persian nation

Won by this salutary demonstration:

Despite a strong defence and adverse weather

All arms combined magnificently together.100

That look at the subsequent reception in antiquity of the Athenian victory at Marathon leads me to my last topic, reception, which has become a fashionable area within classical scholarship in recent decades. And, of course, the reception of Marathon, in antiquity and subsequently, is the overall theme of this volume. A recent book on Cultural Responses to the Persian Wars, of which I was one of the editors, includes a chapter by T. Rood, with the title (taken from E. S. Creasy’s book, cited below) ‘From Marathon to Waterloo’.101 In it he points out that ‘If … the eighteenth century was the age of Thermopylae, then the nineteenth century was, if not quite the age of Marathon, at least the era in which Marathon overtook its main competitor in the battle of the battles’.102 Elizabeth Barrett <Browning>, when about thirteen years old, wrote an epic poem of 1,462 lines on The Battle of Marathon (whose embellishments include the killing of Hippias by Aristides in the battle).103 Byron was inspired by Marathon – for instance:

The mountains look on Marathon –

And Marathon looks on the Sea;

And musing there an hour alone,

I dream’d that Greece might still be free.

B. R. Haydon in 1829 painted ‘The death of Eucles’ (one of the names given to the man who ran back to Athens with the news of the victory), and Robert Browning in 1879 wrote a poem on ‘Pheidippides’, following Lucian in attributing both runs to him. J. S. Mill, reviewing the first volumes of Grote’s History of Greece, began by proclaiming that ‘the Battle of Marathon, even as an event in English history, is more important than the Battle of Hastings [the defeat of the English by the Normans under William the Conqueror in 1066]’. E. S. Creasy took Marathon as the first of his Fifteen Decisive Battles of the World, from Marathon to Waterloo.104 And I am sure there is scope for much more study of the understanding and use of Marathon in the modern world.

At the time, most immediately, the battle of Marathon was a success for the Athenians, which stimulated their growing confidence. That success prompted a further and greater Persian invasion of Greece ten years later, when, although the Greeks’ first attempts to halt the Persians’ advance were unsuccessful, in the end the Greeks were successful again, with consequences for the next hundred and fifty years with which we are familiar. Billows and Krentz both end their books by asking ‘What if’ things had turned out differently.105 Marathon, as it did turn out, became an important element in the stories which the Greeks in general, and the Athenians in particular, told about themselves, and several of the papers in this volume discuss aspects of that. We should note that the Athenians’ story about Marathon was regarded by Theopompus as one instance of how the Athenians cheated the Greeks.106

So, while of course it was important as a battle in which the Athenians and the Plataeans defeated the Persians, Marathon has not been limited to military historians in its appeal. It has prompted questions about the written sources, both literary and epigraphic, about chronology, about archaeology and topography, about practicalities, about Athenian politics, and recently about the reception of Marathon in Greece subsequently and in modern times. It is thus an episode of major importance for people with various kinds of interests in Greece. Marathon prompted a very fruitful conference and volume.

Endnotes

- My thanks to the organizers of the Marathon conference for inviting me to participate, to those who heard this paper and discussed Marathon with me, and to those who were able to point me to the article cited in n. 84 below; also to Prof. Krentz, for giving me his book on Marathon and telling me of other recent books on the battle.

- N. Whatley, ‘On the possibility of reconstructing Marathon and other ancient battles’, JHS 84 (1964) 119-39.

- J. F. Lazenby, The defence of Greece, 490-479 BC (Warminster 1993) 75–80.

- R. A. Billows, Marathon: how one battle changed western civilization (New York & London 2010).

- P. Krentz, The battle of Marathon (New Haven 2010); cf. his chapter in this volume.

- A. W. Gomme, ‘Herodotos and Marathon’, Phoenix 6 (1952) 77-83 = More essays in Greek history and literature (Oxford 1962) 29-37.

- Arist. Rhet. 3.1411a9-11; Dem. 19, Embassy 303; Plut. Quaest. Conv. 628E; Paus. 7.15.7.

- The classic exposition of this view is C. Habicht, ‘Falsche Urkunden zur Geschichte Athens im Zeitalter der Perserkriege’, Hermes 89 (1961) 1-35.

- Hdt. 6.109. Nep. 1, Milt. 4.4-5.2 has Miltiades prevailing in a debate in Athens.

- Hdt. 6.110. Billows, Marathon (n. 4 above) 211-13, accepts χωρὶςἱππεῖς (below), and suggests that the disagreement occurred when it was known that the Persians were embarking their cavalry, and concerned whether to return and defend the city or to stay at Marathon and seize the opportunity to fight.

- Suda (χ 444) χωρὶςἱππεῖς (‘the cavalry separate’); Nep. 1, Milt. 5.3. Opponents of this solution infer from the surprise at the Athenians’ lack of cavalry which Herodotus attributes to the Persians (6.112.2) that the Persians’ cavalry did take part in the battle; and their cavalry did take part in Nep. 1, Milt. 5.3.

- Hdt. 6.102.

- Pisistratus leader of the hyperakrioi, Hdt. 1.59.3, from Brauron, the later Philaidae, [Plat.] Hipparch. 228b; Plut. Sol. 10.3; c. 546, Hdt. 1.62.1. Significance of Hippias already in G. Grote, History of Greece (London, ‘new edition’ in 12 volumes 1869/84) IV 260 = (‘new edition’ in 10 volumes 1888) IV 22-23.

- H. B. Rosén, Herodoti historiae, 2 vols. (Leipzig 1987-97); D. Asheri, Erodoto: le storie, libro I (Milan 1988) cxv (not included in D. Asheri et al., A commentary on Herodotus, books I–IV[Oxford 2007]); D. Gilula, ‘Who was actually buried in the first of the three Spartan graves (Hdt. 9.85.1)? Textual and historical problems’, in Herodotus and his world. Essays from a conference in memory of George Forrest, ed., P. Derow and R. Parker (Oxford 2003) 73-87.

- J. A. R. Munro, ‘Some observations on the Persian Wars, 1. The campaign of Marathon’, JHS 19 (1899) 185-97 (followed by articles on 480 and on 479 in vols. 22 (1902) and 24 (1904)); Cambridge ancient history IV (Cambridge 1926) 229-52.

- Nep. 1, Milt. 4.1, 5.4.

- Where relevant I use underlining to indicate the first or second half of an Athenian year.

- CAH IV (n. 15 above) 232-33, 245, answered by T. J. Cadoux, ‘The Athenian archons from Kreon to Hypsichides’, JHS 68 (1949) 70-123, at 117 n. 253. Phaenippus, e.g., Ath. Pol. 22.3.

- A. R. Burn, Persia and the Greeks: the defence of the west, c. 546-478 BC (London 1962) 238 n. 5. However, this theory is revived by G. Steinhauer, ὁΜαραθὼνκαὶτὸἀρχαιολογικὸμουσείο / Marathon and the archaeological museum (Athens 2009, in Greek and English editions) 96-97, 100-01, 111.

- J. H. Schreiner, ‘The battles of 490 BC’, PCPS 196 = 216 (1970) 97-112; Two battles and two bills: Marathon and the Athenian fleet (Oslo 2004); ‘The battle of Phaleron in 490 BC’, SO 82 (2007) 30-34.

- Hdt. 6.106.3.

- Plut. De Her. Mal. 861E-862A; also Cam. 19.5, De Glor. Ath. 349F.

- Metageitnion = Carneius, Plut. Nic. 28.2.

- See, e.g., G. Busolt, Griechische Geschichte II 2 (Gotha 1895) 580 n. 3, 596 n. 4; Burn, Persia and the Greeks (n. 19 above) 240-41 n. 10, 257, both thinking August more likely; D. W. Olson et al., ‘The moon and the Marathon’, Sky and Telescope 108.3 (September 2004) 34-41, reckon that the full moon of Carneius ought to have been that of August. N. G. L. Hammond, ‘The campaign and the battle of Marathon’, JHS 88 (1968) 13-57, at 40-41 = Studies in Greek history (Oxford 1973) 170-250 at 216-17, considered 6 Boedromion to be not the date of the celebration after the battle but the date of the vow to Artemis made before the battle (Xen. An. 3.2.11-12). Calendars out of step with the moon, and 6 Boedromion the actual date of the battle, e.g. W. K. Pritchett, ‘Julian dates and Greek calendars’, CP 42 (1947) 235-43, at 238, ‘Calendars of Athens again’, BCH 81 (1957) 269-301, at 278-79; and Pritchett also doubted the normal assumption that the full moon must be that of Carneius: in his Ancient Greek military practices I (University of California Publications in Classical Studies 7 [1971]) = The Greek state at war I (Berkeley & Los Angeles 1974) 116-26. See also Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 180-82, 224.

- Mardonius in 492, Hdt. 6.43-45; Thasos in 491, 46-48.1; heralds to Greece, 48.1-49.1; Athens, Sparta and Aegina, 49-93; campaign of 490, 94-124.

- E.g. A. Andrewes, ‘Athens and Aegina, 510-480’, ABSA 37 (1936/37) 1-7, placing part of the story after 490, and noting that most previous scholars had placed all of it after 490; T. J. Figueira, ‘The chronology of the conflict between Athens and Aegina in Herodotus Bk. 6’, QUCC 57 = 228 (1988) 49-89. A. J. Podlecki, ‘Athens and Aegina’, Historia 25 (1976) 396-413, at 396-403, eased the chronological problem in the other direction by suggesting that some of the events which Herodotus mentions here belong to the earlier phase in the conflict.

- N. G. L. Hammond, ‘Studies in Greek chronology of the sixth and fifth centuries BC’, Historia 4 (1955) 371-411, at 387-88, 406-11 = Collected studies I (Amsterdam 1993) 355-95 at 371-72, 390-95; cf. L. H. Jeffery, ‘The campaign between Athens and Aegina in the years before Salamis (Herodotus, 6.87-93)’, AJP 83 (1962) 44-54.

- W. G. Forrest, ‘The tradition of Hippias’ expulsion from Athens’, GRBS 10 (1969) 277-86, at 285, where this is a parallel to the suggestion that at 5.62.2 Herodotus backtracked when mentioning the Alcmaeonids’ taking the contract to rebuild the temple of Apollo at Delphi; P. J. Rhodes, ‘Herodotean chronology revisited’, in Herodotus and his world, ed. Derow and Parker(n. 14 above) 58-72, at 61-62.

- Purpose of Mardonius’ campaign, Hdt. 6.44.1; heralds, 6.48.1-49.1.

- Hdt. 6.95.2; cf. Scythian expedition, 4.87.1, battle of Lade, 6.9.1, and the 1,207 of 480 is just over double that, 7.89-95, 184.1.

- Including the Plataeans, Nep. 1, Milt. 5.1; excluding, Just. 2.9.9. Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 105-06, thinks that the Athenians could have numbered c. 20,000 and that numbers on the two sides were about even.

- Nep. 1, Milt. 4.1, 5.4. 20,000 maximum, C. Hignett, Xerxes’ invasion of Greece (Oxford 1963) 59; 24,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry, Lazenby, The defence of Greece (n. 3 above) 46-47. A survey of modern views: Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 209 (Persian), 211-12 (Athenian).

- Hdt. 6.117.1.

- H. C. Avery, ‘The number of Persian dead at Marathon’, Historia 22 (1973) 757; W. F. Wyatt, Jr., ‘Persian dead at Marathon’, Historia 25 (1976) 483-84. J. Labarbe, La loi navale de Thémistocle (Paris 1957) 165-66, suggested that since 6,400 : 300,000 = 192 : 9,000, the 6,400 was based on assumptions of a Persian army of 300,000 and the same proportion killed on each side. But Billows, Marathon (n. 4 above) 227, thinks the 6,400 was based on a careful count.

- J. Boardman, ‘The Parthenon frieze – another view’, in Festschrift für Frank Brommer, ed. U. Höckmann and A. Krug (Mainz 1977) 39-49.

- Hdt. 6.105-06. See most recently Lazenby, The defence of Greece (n. 3 above) 52-53; D. L. Christensen et al., ‘Herodotos and hemerodromoi: Pheidippides’ run from Athens to Sparta in 490 BC from historical and physiological perspectives’, Hermes 137 (2009) 148-69.

- Plat. Leg. 3.692d,698d-e: championed by G. Dickins, ‘The growth of Spartan policy’, JHS 32 (1912) 1-42, at 31-32; made fashionable by L. H. Jeffery, ‘Comments on some archaic Greek inscriptions’, JHS 69 (1949) 25-38, at 26-30 no. 4, suggesting an early fifth-century date for M&L 22 (later in her life she favoured later dates for other Spartan inscriptions but did not return to this one); against, e.g., H. T. Wade-Gery, ‘The “Rhianos-hypothesis”’, in Ancient society and institutions: studies presented to Victor Ehrenberg on his 75th birthday, ed. E. Badian (Oxford 1966) 289-302. P. Cartledge, Sparta and Lakonia (London 22002) 132-33, professes an open mind; Krentz, The battle of Marathon(n. 5 above) 109-10, inclines to believe both the religious reason and the alternative.

- Plut. De Glor. Ath. 347C, contrasting the identifications of the runner by Heraclides Ponticus and ‘most’; Lucian, Laps. 3. See F. J. Frost, ‘The dubious origins of the Marathon’, AJAH 4 (1976) 159-63. See also, on this dedication in particular and on Persian War monuments in general, C. M. Keesling, ‘The Callimachus monument on the Athenian acropolis (CEG 256) and Athenian commemoration of the Persian wars’, in Archaic and classical Greek epigram, ed. M. Baumbach et al. (Cambridge 2010) 100-30.

- M&L 18 = CEG 256 = IG I3 784 (see IG I3 for bibliography on this and the other Athenian inscriptions cited). Panathenaic dedication with ll. 4–5 added later, E. B. Harrison, ‘The victory of Kallimachos’, GRBS 12 (1971) 5-24. Restoration as a dedication of Callimachus for the victory at Marathon was doubted altogether by P. Amandry, ‘Collection Paul Canellopoulos (I)’, BCH 95 (1971) 585-626, at 625-26 n. 106. See also, on this dedication in particular and on Persian War monuments in general, C. M. Keesling, ‘The Callimachus monument on the Athenian acropolis (CEG 256) and Athenian commemoration of the Persian wars’, in Archaic and classical Greek epigram, ed. M. Baumbach et al. (Cambridge 2010) 100-30.

- Olympia Museum B 2600: E. Kunze, V Bericht über die Ausgrabungen in Olympia (Berlin 1956) 69-74, cf., e.g., A. and N. Yalouris, Olympia: the museum and sanctuary (Athens 1991) 93; the inscription (= IG I3 1472) reads Μιλτιάδεςἀ̣νέ[θ]εκεν [: τ]ι∆ί (‘Miltiades’ dedicated [it] to Zeus’). The Persian helmet – B 5100; Kunze, VII Bericht über die Ausgrabungen in Olympia (Berlin 1961) 129-37; with the inscription (= IG I3 1467) ∆ιὶ ̓ΑθεναῖοιΜέδονλαβόντες (‘the Athenians [dedicated it] to Zeus, having taken it from the Medes’) – probably reflects a later occasion.

- M&L 26 = CEG 2-3 (without the additional block) = IG I3 503-04.

- A. P. Matthaiou, ‘ ̓Αθηναίοισιτεταγμένοισιἐντεμένεϊ ̔Ηρακλέος’, Herodotus and his world, ed. Derow and Parker (n. 14 above) 190-202, at 194-200; A. Petrovic ́, Kommentar zu den simonideischen Versinschriften, Mnemosyne Supp. 282 (Leiden and Boston 2007) 158-77, esp. 165-67.

- G. Spyropoulos, οἱστήλεςτῶνπεσόντωνστὴνμάχητοῦΜαραθῶναἀπὸτὴνἔπαυλητοῦ ̔Ηρώδη ̓ΑττικοῦστὴνΕὔαΚυνουρίας (Athens 2009); G. Steinhauer, ‘στήληπεσόντωντῆς ̓Ερεχθηίδος’, hόρος 17-21 (2004-09) 679-92, cf. his Marathon (n. 19 above) 122-23. See Petrovic ́ in this volume, pp. 53-56.

- M&L 19 = IG I3 1463.

- Paus. 10.11.5. K. W. Arafat stresses that being built from the spoils of a victory need not imply being built in order to celebrate the victory: cf. Arafat in this volume, p. 81.

- Hdt. 6.94.2, etc.

- The tablet, PF-NN 1809, published and discussed by D. M. Lewis, ‘Datis the Mede’, JHS 100 (1980) 194-95 = Selected papers in Greek and near eastern history (Cambridge 1997) 342-44; the tablet is no. 56 in M. Brosius, The Persian empire from Cyrus II to Artaxerxes I, LACTOR 16 (London 2000) and ch. 6 no. 41 in A. Kuhrt, The Persian empire (London 2007). The Lindian Temple Chronicle, FGrH 532 §D: already in favour of 494 before Lewis published the tablet, e.g. K. J. Beloch, Griechische Geschichte 2 II.2 (Strassburg 1916) 81-83; Burn, Persia and the Greeks (n. 19 above) 210-11, 218; in favour of 490, e.g. Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 94-95, 209.

- Marathon, J. P. Six, ‘Monnaies grecques, inédites et incertaines, xxix’, NC 3 15 (1895) 172-79, at 176, cf., e.g., C. T. Seltman, Greek coins (London 21955) 91-92; Burn, Persia and the Greeks (n. 19 above) 255-56; N. Sekunda, Marathon, 490 BC: the first Persian invasion of Greece (Oxford 2002) 45; Salamis: implied by H. H. Howorth, ‘The initial coinage of Athens, &c.’, NC 3 13 (1893) 241-46, at 245, cf., e.g., C. G. Starr, Athenian coinage, 480-449 BC (Oxford 1970) 3, 12-19; perhaps a general celebration, C. M. Kraay, Archaic and classical Greek coins (London 1976) 61-62.

- In addition to the works cited for individual points below, see particularly W. K. Pritchett, Marathon, University of California Publications in Classical Archaeology 4.2 (Berkeley 1960); J. A. G. van der Veer, ‘The battle of Marathon: a topographical survey’, Mnemosyne 4 35 (1982) 290-321. The coastline of the bay of Marathon has undoubtedly moved over the centuries, but it is not clear where the line was in 490: for an up-to-date discussion see Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 114-17, 214-15.

- More specifically, E. Vanderpool, ‘A monument to the battle of Marathon’, Hesperia 35 (1966) 93-106, at 103, suggests that the main camp was on the inland side of the great marsh; cf. Hammond, ‘The campaign and the battle’ (n. 24 above) 33 with 20 plan 3 = 203-04 with 181 fig. 11; Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 105, puts the cavalry’s camp there but the infantry on the coastal side of the marsh. On the other hand, Steinhauer, Marathon (n. 19 above) 95, thinks that is inappropriate to an attacking force and places the camp near Pausanias’ trophy at the west end of the marsh (see below with n. 58).

- Hdt. 6.108.1 cf. 116; the coastal site is the find-spot of IG I3 3 and 1015 bis. See most recently Matthaiou, in Herodotus and his world, ed. Derow and Parker(n. 14 above), suggesting that the exit from the plain which the camp guarded formed the ‘gates’ in front of which the battle was fought according to IG I3 503/4, lapis A, ii; Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 118-21, 215. Billows, Marathon (n. 4 above) map 5 and 208, still prefers the inland site.

- Inland site: E. Vanderpool, ‘The deme of Marathon and the Herakleion’, AJA 2 70 (1966) 319-23; Plasi: W. K. Pritchett, Studies in ancient Greek topography II, University of California Publications in Classical Studies 4 (Berkeley 1969) 1-11; S. Marinatos, ‘Further discoveries at Marathon’, AAA 3 (1970) 153-66, at 153-54; cf. J. S. Traill, Demos and trittys (Toronto 1986) 147-48; Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 121-22.

- See Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 122-29, 216-17. But even that identification has been doubted, though I think unjustifiably: most recently, by S. N. Koumanoudis, ‘Μαραθῶνι’, AAA 11 (1978) 232-44, at 235-36, cf. AR 27 (1980/81) 5-6.

- Suggested by Marinatos, ‘Further discoveries’ (n. 52 above) 164-66: Paus. 1.32.3; see W. K. Pritchett, The Greek state at war IV (Berkeley & Los Angeles 1985) 126-29; Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 129-30, 217, does not definitively reject the identification but thinks it irrelevant to the location of the battle.

- Paus. 1.15.3 cf. 32.7.

- But Lazenby, The defence of Greece (n. 3 above) 65-66, cf. 55, is not certain of that; and Sekunda, Marathon (n. 48 above) 48, thinks it did exist but would be almost dry by late summer.

- For references see Lazenby, The defence of Greece (n. 3 above) 55 with n. 23.

- Vanderpool, ‘A monument’ (n. 50 above) 93-106; Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 130-32; cf. Paus. 1.32.5. Hauptmann Eschenburg found what were probably the bones of Persians near here: Topographische, archaeologische und militärische Betrachtungen auf dem Schlachtfelde von Marathon (Berlin 1886: non vidi) 10, cf. Wochenschr. Kl. Phil. 4 (1887) 152-56 + 182-87, AA 1 (1889) 33-39.

- Sekunda, Marathon (n. 48 above) 59-64; Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 129-33.

- Hammond, ‘The campaign and the battle’ (n. 24 above) 26, 34, 36-37 = 190, 205, 210; cf. earlier G. B. Grundy, The great Persian war and its preliminaries (London 1901) 164-65, 173-74, 186; but in CAH IV2 (Cambridge 1988) 507, 512, Hammond takes the Athenians to Marathon by both routes and back by the Pallene route. Billows, Marathon (n. 4 above) 229-30, thinks that after the battle the Athenians will have used both routes. Pisistratus c. 546 had taken the obvious route: Hdt. 1.59.

- Hdt. 6.107-09, 121.1.

- Cf. Lazenby, The defence of Greece (n. 3 above) 62.

- Hdt. 6.111-13.

- Most recently Billows, Marathon (n. 4 above) 214-15, 225. Against that assumption, Lazenby, The defence of Greece (n. 3 above) 64, 69-70, 79, with references to scholars who make the assumption; also Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 154, 158.

- But the redoubtable Hammond included the run among the elements in Herodotus’ narrative which he considered ‘completely unimpeachable’: ‘The campaign and the battle’ (n. 24 above) 28-29 = 194-95.

- Grundy, The great Persian war (n. 60 above) 188 with n. *.

- Thuc. 4.78.5: A. W. Gomme, A historical commentary on Thucydides III (Oxford 1956) 544-45 ad loc., noted the relevance of this to Marathon.

- W. Donlan and J. Thompson, ‘The charge at Marathon: Herodotus, 6.112’, CJ 71 (1975/76) 339-43; ‘The charge at Marathon again’, CW 72 (1978/79) 419-20.

- Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above): location of battle, 129-33 (cf. above with n. 59); Miltiades’ day, 153 (cf. below with n. 84); plan to attack Persian infantry before cavalry could be deployed, 142-43; hoplites’ armour and run, 45-50, 143-52.

- Hdt. 6.113.1. In Ar. Vesp. 1077-90 the veterans claim to have driven back the barbarians πρὸςἑσπέραν (‘until evening’), but that is perhaps not to be taken seriously as evidence. Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 156-57, reckons that from the Athenians’ advance to their return to camp the battle must have lasted at least six hours.

- No text states that the Persians reached Phalerum on the day of the battle; Plut. Arist. 5.5 states that the Athenians reached Athens on the day of the battle, but the ambiguous De Glor. Ath. 350E may mean that they returned on the day after the battle, ΜιλτιάδηςμὲνγὰρἄραςἐςΜαραθῶνατῇὑστεραίᾳτὴνμάχηνσυνάψαςἧκενἐςἄστυμετὰτῆςστρατιᾶςνινικηκώς (‘Miltiades set off for Marathon and after doing battle next day arrived in the city victorious’). In addition to the other studies cited here, J. P. Holoka, ‘Marathon and the myth of the same day march’, GRBS 38 (1997) 329-53, reckons that neither the Athenians nor the Persians could have made their journey on the day of the battle.

- Hdt. 6.115-16. That the shield was used to flash a heliographic signal is not stated by Herodotus but has been widely assumed. Plut. De Her. Mal. 862C-863A doubted the authenticity of the signal.

- Hammond, ‘The campaign and the battle’ (n. 24 above) 36-37 = 209-11, cf. 43 = 220-21; cf. the timings of Billows, Marathon (n. 4 above) 227-30, who assumes that the first Persian ships set sail at daybreak, before the battle.

- Hammond, ‘The campaign and the battle’ (n. 24 above) 43 n. 126 = 221 n. 1.

- A. T. Hodge and L. A. Losada, ‘The time of the shield signal at Marathon’, AJA 2 74 (1970) 31-36. Lazenby, The defence of Greece (n. 3 above) 72-73, and Billows, Marathon (n. 4 above) 228, doubt whether there was a signal at all; Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 161-63, 222-23, accepts that there was some signal and discusses reinterpretations.

- A. T. Hodge, ‘Marathon to Phaleron’, JHS 95 (1975) 169-71, ‘Marathon: the Persians’ voyage’, TAPA 105 (1975) 155-73.

- R. Osborne, Greece in the making, 1200–479 BC (London 2 2009): on Marathon and its aftermath, 311-16; quotations from 313, 312.

- Generals: e.g. Pisistratus against Megara: Hdt. 1.59.4.

- Ath. Pol. 22.2 (with ἔτειπέμπτῳ emended to ἔτειὀγδόῳ).

- Equality of generals, K. J. Dover, ‘δέκατοςαὐτός’, JHS 80 (1960) 61-77 = The Greeks and their legacy, Collected papers 2 (Oxford 1988), 159-80. Alcibiades in 407/06, Xen. Hell. 1.4.20; Diod. Sic. 13.69.1-3; Plut. Alc. 33.2-3.

- Hdt. 6.105.1, 106.1; 103.1; 109.1.

- Hdt. 6.109-10.

- Hdt. 6.110.

- Daily rotation is implied by the accounts of Arginusae and Aegospotami in Diod. Sic. 13.97.6, 106.1. W. G. Forrest was willing to accept that explanation: ‘Motivation in Herodotos: the case of the Ionian Revolt’, International History Review 1 (1979) 311-22, at 321; cf. Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 153.

- Hdt. 6.111.1.

- Hammond, ‘The campaign and the battle’ (n. 24 above) 48-50 cf. 45 = 229-33 cf. 223-24, ‘Strategia and hegemonia in fifth-century Athens’, CQ 2 19 (1969) 111-44 at 119-23, revised as ‘Problems of command in fifth-century Athens’, in Studies (n. 24 above) 346-94 at 358-64; E. Badian, ‘Archons and strategoi’, Antichthon 5 (1971) 1-34, at 21-27.

- Hdt. 6.109.2; Ath. Pol. 22.5; Paus. 1.15.3.

- Hdt. 6.115, 121-24.

- Hdt. 1.60.2-61.2, cf. Ath. Pol. 14.4-15.1.

- Hdt. 1.64.4, 5.62.2.

- M&L 6. c. 3 = IG I3 1031.18.

- Ath. Pol. 22.4–6.

- Hippocrates, Agora 25, 50-61, S. Brenne, Ostrakismos und Prominenz in Athen,Tyche Supp. 3 (Vienna 2001) 166-67 no. 105; Callixenus, Agora 25, 66-88, [πρ]οδότες, 88 no. 589, Brenne, Ostrakismos und Prominenz 186-88 no. 124.

- A. Ruberto, ‘Il demos, gli aristocratici e i Persiani: il rapporto con la Persia nella politica ateniese dal 507 al 479 a.C.’, Historia 59 (2010) 1-25.

- See, for instance, W. G. Forrest, ‘Themistokles and Argos’, CQ 2 10 (1960) 221-41, at 236; A. J. Podlecki, Aeschylus and Athenian politics (Ann Arbor 1966) 9-17; J. A. Davison, ‘Aeschylus and Athenian politics, 472-456 BC’, in Ancient society and institutions, ed. Badian (n. 37 above) 93-107, at 101-03; E. M. Hall, Aeschylus, Persians (Warminster 1996) 11-12; A. H. Sommerstein, ‘The theatre audience, the demos and the Suppliants of Aeschylus’, in Greek tragedy and the historian, ed. C. B. R. Pelling (Oxford 1997) 63-79, at 73. For doubts see Pelling, ‘Aeschylus’ Persae and history’, in Greek tragedy and the historian 1-19, at 9-12.

- Ar. Ach. 181, etc. For Marathon in comedy see Carey and Papadodima in this volume.

- Pan, Hdt. 6.105-06.1; Epizelus, 117.2-3. For the legends cf. Lazenby, The defence of Greece (n. 3 above) 80.

- Paus. 1.15.3, 32.4, 7, 5.

- Dio Chrys. Or. 11. Trojan 148 (with an account of 480 in §149); Theon, Progymnasmata 8 (115.19-20 Spengel). I was alerted to these texts by the paper of E. L. Bowie in this volume.

- R. Graves, ‘The Persian version’, in his Collected poems 1975 (London 1975) 146 (apparently written in the mid-1940s). The remainder of the poem seems to deal with the events of 480 but to misdate them to 490.

- T. Rood, ‘From Marathon to Waterloo’, in Cultural responses to the Persian wars, ed. E. E. Bridges, E. M. Hall, and P. J. Rhodes (Oxford 2007) 267-97.

- Rood, ‘From Marathon to Waterloo’ (n. 101 above) 268.

- E. Barrett <Browning> (b. 1806), The battle of Marathon (dedication dated 1819; London 1820; reprinted with an Introduction by H. B. Forman, London 1891; included, e.g., in E. B. Browning, The poetical works, ed. F. G. Kenyon (London 1904) 1–24). Hippias killed by Aristides: ll. 1411-23.

- Byron, Don Juan 3.86.3.1-4; Haydon, see Rood, ‘From Marathon to Waterloo’ (n. 101 above) 268-71; R. Browning, ‘Pheidippides’, e.g., in The works (London 1912) IX.221-28; J. S. Mill, Edinburgh Review 84 (1846) 343-77, at 343 (unsigned) = Essays on philosophy and the classics, Collected works 11 (Toronto and London 1978) 273-305, at 273; E. S. Creasy, The fifteen decisive battles of the world, from Marathon to Waterloo (London 1851) (‘From Marathon to Waterloo’ became so familiar an expression that it was used by Major-General Stanley in W. S. Gilbert, The pirates of Penzance).

- Billows, Marathon (n. 4 above) 255-61; Krentz, The battle of Marathon (n. 5 above) 172-75.

- Theopomp. FGrH 115 F 153.

Contribution (3-21) from Marathon – 2,500 Years, edited by Christopher Carey and Michael Edwards (University of London Press, 12.02.2013), Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.