Churches depended to a large extent on the distribution of funds raised from ecclesiastical property.

By Dr. Ian N. Wood

Professor Emeritus of Early Medieval History

University of Leeds

Like the soldiers of the Roman army, the clergy and the monks of the late-antique and early medieval world had to be provided for. Unlike the late-Roman army, they were not the recipients of the money raised by imperial or royal taxation, although they often benefitted from exemptions and privileges granted by kings. Above all they were the beneficiaries of gifts, which were regarded as inalienable possessions of the Church, except in certain exceptional circumstances.1 Monks were supported by the endowments of their monasteries, although, as the letters of Gregory the Great make clear, these were not always adequate. On a number of occasions, the pope provided additional funds for monastic communities, not least for the nuns of Rome.2 Of course, many of the lower clergy must have earned a living, but we should note the references to provision for priests in the canons of the councils of Epaon (517)3 and IV Orléans (541),4 while II Braga (572) stated that no bishop was to dedicate a church unless he had received a charter providing for the lighting of the church and sustenance for the cleric serving there.5

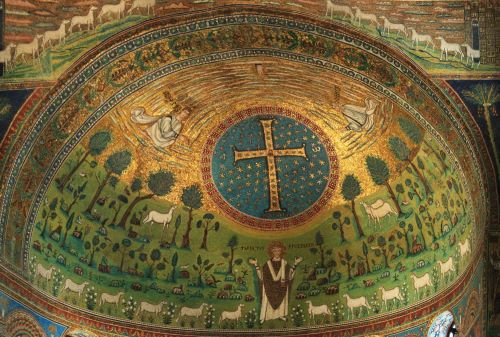

Churches and churchmen depended to a large extent on the distribution of funds raised from ecclesiastical property. In addition to the endowments of individual churches, there was the income from the land held by the diocese, as well as various other dues. There is, however, little to indicate that an ecclesiastical tithe was required in this period,6 although a decima is mentioned in the Vita Severini by Eugippius,7 and by Caesarius.8 The second Council of Mâcon (585) seems to be the first attempt to enforce it.9 But bishops might claim the cathedraticum, a levy of 2 solidi from each parish, which is attested in Spain as well as Italy.10 The bishops of Ravenna are known to have received 888 hens, 266 chickens, 8,880 eggs, 3,760 pounds (librae) of pork (1236.28 kilos) and 3,450 pounds of honey (1124.36 kilos), as well as geese and milk to cover their obligations of hospitality.11 This may sound considerable, but for his Lenten retreat to the monastery of Île-Barbe the ascetic bishop Eucherius of Lyon ordered 300 modii of corn (2,610 liters), 200 of wine (1,740 liters), 200 pounds of cheese (65.76 kilos), and 100 pounds of oil (32.88 kilos).12 In addition to such renders, churches could also rely on the alms and oblations of the faithful.

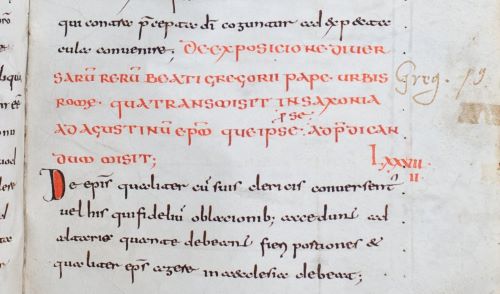

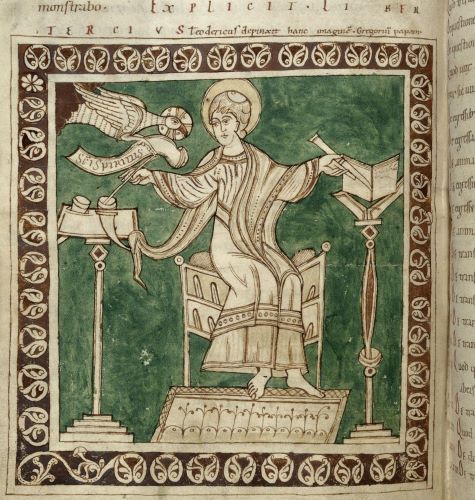

For the most part, however, churches must have depended on the income drawn from their own estates. In large areas of western Europe, the majority of ecclesiastical income was redistributed according to the Quadripartum, a fourfold division of revenue laid down by a number of authorities, popes, and councils, in the fifth and sixth centuries. The Quadripartum is first referred to by Pope Simplicius (468–483),13 and full statements come in three letters and two fragments of letters from Gelasius (492–496), which talk of the quartae as portiones consuetae,14 and in the so-called Responsiones of Gregory the Great (590–604) to Augustine of Canterbury.15 Other letters of Gregory provide important details on the allocation of Church revenue,16 and his implementation of the Quadripartum is de-scribed by John the Deacon in his Life of the pope.17 It is also referred to in a letter of pope Felix IV (526–530), addressed to bishop Ecclesius of Ravenna18 — a ruling which was to have significant repercussions for the city’s clergy towards the end of the following century, when they claimed that archbishop Theodore (c. 677–c. 691) had stolen their quarter from them.19 In addition to the papal rulings, we find a similar division of income in the canons of the first Council of Orléans (511).20

In all these cases the income of the Church is divided into four, although there is some variation over the recipients of the individual quarters. A classic definition is that given by Gregory the Great, which is essentially the same as the one to be found in the letters of Gelasius: “all money received should be divided into four portions: that is, one for the bishop and his household for the purposes of hospitality and entertainment, a second for the clergy, a third for the poor, and a fourth for the repair of churches.”21 In the canons of the first Council of Orléans, which might only deal with the proceeds from land recently received from Clovis, the quarters were allocated “to the restoration of churches, the alms of clerics (sacerdotes), the poor, and the redemption of captives.”22

The arrangements in Spain were slightly different. The canons from Suevic Gallicia imply that the proper division of Church income was into three. This, oddly enough, was what Theodorus lector, writing in Constantinople in the early sixth century, thought was also the tradition in Rome.23 Already in the First Council of Braga (561) one finds: “it is agreed that the goods of the Church should be divided into three equal portions: that is, one for the bishop, a second for the clergy, a third for repairs and the lighting of the church, for which part either the archpriest or the archdeacon administering it should render account to the bishop.”24 In an epitome of the council’s canons from c. 600 we find a clear reassertion of a tripartite division: “Three portions should be made of the goods of a Church: for the bishop, the church and the clergy.”25 Ten years later, the second Council of Braga prohibited a bishop from claiming the tertia of oblations allocated to the lighting of the churches.26

In the Visigothic kingdom, Church income was also subject to a three-fold division. Even prior to the conversion of the Gothic leadership, the Catholic Council of Tarragona (516) forbade a bishop from taking more than a third of the income of a parrocia, on account of the poverty of some churches and the ruinous state of their basilicas. And it refers to the arrangement as an ancient tradition.27 The seventh-century canons specify a division between the bishop, the priests and deacons, and the primicerius, who was to distribute the final third among the lower clergy, as appropriate.28

In contrast to the pattern of financial distribution laid down by the Quadraticum, there is no mention here of any portion allocated to the poor. The fourth Council of Toledo (633) did, however, instruct bishops to protect the poor.29 But the first canon of V Toledo (636) merely instituted litanies “pro abundante iniquitate et deficiente caritate” (“on account of abundant iniquity and deficient charity”).30 Attached to the canons of the tenth Council of Toledo (656), there is a document condemning the will of bishop Riccimir of Dumio, who had given land to the Church, on condition that the proceeds were distributed to the poor, who he had also supported out of ecclesiastical in-come. In addition, alongside his own slaves, he had manumitted some which had belonged to the Church, without providing compensation.31 The bishops in Council were clearly more concerned with the protection of ecclesiastical property than with providing support for the poor. It would seem that good works were not as institutionalized in Spain as they were elsewhere, although bishop Massona of Mérida did build a xenodochium for peregrini and the sick.32 Isidore thought (with the words of Christ in mind) that bishops should care for the poor, feed the hungry, clothe the naked, receive strangers, ransom captives, and care for widows and orphans.33 And bishops were specifically tasked by Reccared to protect the poor against the unjust exactions of judges,34 while Recceswinth charged them with opposing inequitable judgements.35 Isidore also thought that kings had an obligation to look after the poor, and praised Swinthila for so doing,36 although the king was denigrated by IV Toledo for his oppression.37 This, however, does not add up to the same pattern of redistribution that we find in papal Italy or Merovingian Francia.

The tertia may also have been the norm in the Byzantine East, although it differed from what we can reconstruct of the Spanish system: a threefold division between the poor, the household of the bishop, and the clergy can be deduced from the Apostolic Canons from fourth-century Syria.38 Some indication of the groups and causes that were to be supported by the Church are also listed in Justinian’s Novels.39 The true complexity of the division of ecclesiastical income, however, is best attested in the rich documentation from Egypt.40

The ideal model for the distribution of the Quadripartum is set out by John the Deacon in his Life of Gregory of Great: the pope translated all the revenues of the papal patrimony into coin, he then summoned the officials of the Church, the palace, the monasteries, the churches, cemeteries, deaconries, and xenodochia, and made payments in line with the polypticum of Gelasius. And he made the distribution four times a year, at Easter, the Feast of the Apostles, St. Andrew’s Day, and the anniversary of his own consecration.41 The deaconries, or diaconiae, were the centers of charitable distribution:42 in late-antique Rome there were seven of them.43

The precise system by which the clerical portion of the Quadripartum was distributed in Rome in the time of Gregory can hardly have been the norm for the rest of the Christian West, although Carthage, like Rome, was divided into seven ecclesiastical regions.44 But, in cities other than Rome, the diaconiae did play a crucial role in the distribution of poor relief.45 Again Gregory provides important information. A letter to a religiosus, John, puts him in charge of feeding the poor, which involved the appointment and supervision of deacons, although unfortunately the pope does not specify whether the appointment relates to Rome or to another city.46 Other letters in the Register reveal the existence of a diaconia in Pesaro47 and in Naples.48 Later sources, including a letter of pope Hadrian (772–795),49 also note the existence of a diaconia in Naples,50 and there are further references to such institutions in Cremona and Lucca.51 The institution seems to have been widespread in Italy.

Although it is not explicitly stated that the quartae of the Quadripartum should be equal, this is surely implied by the Ravenna evidence, and also by Gregory’s letter to John of Palermo, which talks of the distribution of the entirety of the clerical quarta of the Church’s revenues according to the desires and activities of the individual cleric: “that from the Church revenue, you should provide without any delay a whole quarter share for your church’s clergy, according to each one’s merit, rank and work […]”; this was according to established custom: “iuxta pristinam consuetudinem” (“according to the old custom”).52

There is plenty of evidence that not all bishops actually divided Church revenue as they were supposed to.53 The best single example of a failure by a bishop to distribute their quarta to the clergy is the dispute between bishop Ecclesius of Ravenna and a large section of the clerics of the city, which had to be settled by pope Felix IV.54 And the issue blew up again in the time of archbishop Theodore, in the late seventh century.55 Equally illuminating is a set of letters in the Register of Gregory the Great. He wrote to bishop Gaudentius of Nola, instructing him to ensure that the clergy of Capua who were living in Naples should receive their quarta.56 He told John of Palermo to distribute the entire quarta of the clergy according to their desires.57 He also wrote to Paschasius of Naples to point out that the bishop’s predecessor had made no provision for the clergy or for the poor.58 So he now instructed Paschasius to set aside 400 solidi for the clergy and the poor: 100 solidi were to be divided between the clergy as appropriate, 63 solidi were to be divided between the 126 prebendaries, a further 50 were to go to priests, deacons and visiting clergy, 150 were to go to the honorable but hard-up (who were to get a triens each — in other words, there were 450 of them), and 36 solidi were to go to the ordinary poor. In fact, it appears that Paschasius went on to squander the Church’s revenues in building boats — the pope fumed that he had enjoyed going down to the sea every day.59

There is evidence from elsewhere of a failure to divide ecclesiastical income in accordance with the norms. The Council of Mérida (666) condemned bishops for taking the tertia of the parochial churches.60 And the sixteenth Council of Toledo (693) reaffirmed the legislation.61 In the canons of the Council of Carpentras in 527, we find a statement that in some dioceses the bishop had kept all the offerings made by the faithful of the parrochiae, passing nothing on to the churches, either for their clergy or for the upkeep of the basilicas.62 The Fourth Council of Toledo inveighed against bishops taking more than the tertia oblationum — their avarice had left parishes impoverished, with their basilicas falling into ruin.63

We should be aware of a distinction between the distribution of the Church’s income from its property, and that of the alms and oblations of the faithful — and the Councils of Carpentras and IV Toledo refer to oblations, not to the revenue derived from property. According to Gregory the Great, such donations ought also to be allocated according to a division into quarters.64 But, although the first Council of Orléans (511) suggests a fourfold division of the revenue from lands given to the Church by Clovis, it allocates half of the offerings placed on the altar (perhaps of the cathedral church) to the bishop and the other half to the remainder of the clergy, while only a third of the offerings in rural parishes (parrochiae) went to the bishop.65 The third Council of Orléans (538), on the other hand, gives the bishop discretion over the division of oblations offered in the urban basilicas, while leaving the allocation of offerings made in parishes (parrochiae) and rural basilicas to established tradition.66 There are several references to the distribution of offerings in the works of Gregory of Tours.67 In Spain, the second Council of Braga refers to the tertia of oblations allocated to the lighting of the churches.68

Despite the clear variation, it would seem that the income of a considerable proportion of western Europe, together with other dues and bequests, was divided between the bishop, the clergy, the upkeep of ecclesiastical buildings, and the poor — alongside whom, at various moments, there were captives, whose ransom could also be a matter of ecclesiastical concern.69 We have already noted the numbers of clergy who were supported by the revenues of the Church, and of the numbers of churches. It is worth pausing on the allocation of funds to the poor, the captives, and, first, to the provisions made for the performance of the liturgy, which went beyond the mere upkeep of church buildings.

The performance of cult depended on the provision of liturgical vessels, many of which were costly, as can be seen most obviously in the lists of donations to be found in the Liber Pontificalis.70 In addition, there was a need for gospel and liturgical books (potentially a huge expense — think of the 1525 animal skins needed for the three Pandects of the Bible produced for Ceolfrith at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow, although these codices were exceptional).71 And, of course, there were festal days to be catered for. Gregory the Great allocated 10 solidi for the poor, 30 amphorae of wine, 200 sacks of corn, 2 large jars of olive oil, 12 rams, and 100 chickens for the dedication feast of a simple oratory of the Virgin, because abbot Marinianus and his community were too poor to pay for the celebration.72

Liturgical vessels, manuscripts, and dedication feasts, how-ever, did not require regular expenditure, unlike the lighting of a church, which was often the object of specifically allocated funding. The oil or wax needed for lighting churches was a very considerable expense, as has been shown in recent work by Stefan Esders and Paul Fouracre.73 The allocation of funds for lights (luminaria) could be remarkably precise. In a grant to the monastery of Corbie issued in 716, Chilperic II confirmed the concession issued by his uncle Chlothar II and his grandmother Balthild of toll income (telloneum) at the southern port of Fos. The monastery was to receive the toll taken on 10,000 pounds of oil, 30 modii of garum, 30 pounds of pepper, 150 pounds of cumin, 2 pounds of cloves, 1 pound of cinnamon, 2 pounds of nard, 30 pounds of bitter root, 50 pounds of dates, 100 pounds of figs, 100 pounds of almonds, 30 pounds of pistachios, 100 pounds of olives, 50 pounds of water pots(?), 150 pounds of chickpeas, 20 pounds of rice, 10 pounds of gold pigment, 10 jeweled skins, 10 Cordoban skins, and 50 quires of papyrus.74

As Paul Fouracre has noted, the monastery of St. Denis had an annual grant of 300 solidi for lights in 695.75 The first Council of Braga allocated one tertia for the upkeep and lighting of churches.76 This pales into insignificance when one remembers the 7 estates, yielding 4,390 solidi a year, supposedly given by Constantine to the Lateran for its lighting77 — I do not doubt the number of estates in papal hands by the sixth century, but I will come back to the problem of the chronology of some of the emperor’s supposed donations. The provision of lights, one might add, is a significant issue in the temple societies of India.78

As for Church provision for the poor, one needs to begin by stressing the point that has been made frequently by modern scholars, that it differed from the official corn dole of the Roman Empire, the annona civica, which was not intended for paupers. Jean-Michel Carrié has shown that those eligible for the frumentatio in Rome were native male citizens who had achieved age of majority.79 It was a privilege that was available to registered adult men not only in Rome, but also in other centers such as Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch. It was also available in smaller centers, as is apparent from the Oxyrhynchus papyri. John Rea, in his study of the Oxyrhynchus evidence, stated: “It is very clearly confirmed […] that the doles were not a provision for the very poor, but the perquisite for the already privileged middle class of the cities, as in Rome.”80 Whether the Oxyrhynchus evidence can be taken as illustrating arrangements in smaller cities throughout the Empire is, however, unclear. But while the Roman State was concerned with providing for citizens, including citizens who had fallen on hard times, it had little time for beggars.81

As Michele Salzman, following Peter Brown, has argued, Christian concern for the poor marked a new departure in a number of respects82 — although both of them, like Bronwen Neil,83 have stressed the extent to which civic societal relations survived well into the fifth century. This was in part because the emperors themselves began to legislate in terms that reflected Christian values. Thus, Valentinian I authorized the distribution of the annona civica according to the needs of citizens, and not automatically to those who claimed citizenship.84 Salzman, following Jean-Michel Carrié, has noted that the annona civica continued into the sixth century, although Justinian charged the pope, Vigilius, not the City Prefect, with its distribution.85

But Christian charity was directed much more towards the economic poor than towards the citizens who could claim the right to the dole — although Gregory the Great certainly did show concern for “distressed gentlefolk,” to use Peter Brown’s favored expression for those who had fallen on hard times.86 Already in the fourth century the pagan emperor Julian the Apostate seems to have noted and approved of the attention paid to the poor by Jews and Christians. In a letter to Arsacius, high priest of Galatia, he stated:

I have given directions that 30,000 modii of corn shall be assigned every year for the whole of Galatia, and 60,000 pints of wine. I order that one-fifth of this be used for the poor who serve the priests, and the remainder be distributed by us to strangers and beggars. For it is disgraceful that, when no Jew ever has to beg, and the impious Galilaeans support not only their own poor but ours as well, all men see that our people lack aid from us. Teach those of the Hellenic faith to contribute to public service of this sort, and the Hellenic villages to offer their first fruits to the gods; and accustom those who love the Hellenic religion to these good works by teaching them that this was our practice of old.87

Significantly, when he illustrates what he regards as the traditional practices of the pagans, he does so with a citation from Homer and not with an illustration from any more recent history. Julian, of course, was writing a full century before the first reference to the Quadripartum, but institutionalized concern for the “distressed” on the part of the Christians is already attested in 251, when pope Cornelius claimed that there were “more than 1500 widows and distressed persons” on the books of the Church of Rome.88

We have a good deal of evidence on distribution to the poor in Gregory the Great’s letters. Some of the poor are very definitely distressed gentlefolk; Gregory’s own aunt Pateria is given 20 solidi a year, and her children 40, as “shoe-money” (“ad calcarium suorum”) and 300 modii of wheat, while two other noble ladies, Palatina and Viviana, were allocated 20 solidi and an equal amount of grain.89 Shortly after, Palatina’s allowance was raised to 30 solidi.90 The one-time governor of Samnium, Sisinnius, who had fallen on hard times, was given 20 modii of wheat and 4 solidi annually, because he was now poor.91 Among others facing financial hardship, the palace officials of Rome were to be provided with corn,92 and the religiosus Anastasius and the mother of Urbicus with 6 solidi each.93 Other beneficiaries were Theodore,94 the children of Urbicus,95 the blind Pastor, who received a regular supply of beans and corn,96 Albinus, also with impaired vision (who was to receive 2 tremisses a year),97 and the scholar Mateus (12 solidi).98

In some of these cases, we may not be dealing with the funds of the Quadripartum. In a letter to John of Palermo, Gregory makes it quite clear that there was a distinction between the distribution of the revenue from Church property and the distribution of money that had been offered as alms and oblations by the pious. The donations were to be put on one side, and then added to the income of the Church, the whole of which was to be supervised by a manager.99

Perhaps better known than the information provided by Gregory the Great is that to be found in the Histories and Miracula of Gregory of Tours, not least because those on the poor lists of Francia, the matricularii, attracted the attention of Arnold Pöschl,100 and more recently of Valerio Neri101 and Peter Brown.102 We find references to those involved in the distribution of the matricula in Candes and Brioude. A woman with a withered arm, who helped in the distribution of the matricula at Candes, was cured as a result of her good works,103 while the blind girl, whose father supported the matricula at Brioude, gained her sight.104 There is a reference to the matricula of Rheims in the will of Remigius, preserved by Hincmar, where we hear that the bishop left 2 solidi to each of those on the list.105 And the statement in the Second Council of Tours (567) that each civitas, as well as presbyteri and cives should provide for its pauperes and egenos as best they could, which implies a reference to the matricula.106 But in some instances, it seems that we are dealing with the distribution of alms rather than the Quadripartum. Gregory provides numerous references to those hanging around the shrines of the saints, expecting support and hoping for a cure, not least the lame and the deformed.107 These could form a significant force in support of their local church, as did the matricularii and pauperes of St. Martin’s following the sacrilege perpetrated in the course of the murder of Eberulf in the holy precinct.108 As Valerio Neri has noted, we seem to have two categories of people in this story: the official matricularii, registered on the poor list, and other pauperes, who were waiting for the distribution of alms.109 These other pauperes seem to be the subject of a further anecdote in Gregory: in the atrium at Tours a custos was given a gold coin to donate to the poor, but he pocketed it, substituting a silver piece, and promptly died.110 In Spain, there may also be a distinction between the revenue that came from property and the oblations of the people.111

Alongside care for the poor one can note that for the sick. The notion of the hospital seems to emerge in fourth-century Anatolia.112 There are examples in Rome around 400, and in Gaul from the days of Caesarius of Arles.113 There may have been 34 hospitals in Merovingian Francia, while 282 have been identified for the late- and post-Roman World.114 They clearly catered primarily to the poor as well as the diseased. Gregory of Tours talks of hospitiola pauperum in Tours,115 as well as a leper house in Chalon-sur-Saône.116 How well-endowed they were is unclear, but in the case of the xenodochium founded in Lyon by king Childebert and his queen Ostrogotha we may guess that the endowment was substantial. And the foundation, like the others of which we hear, was a religious one — in the case of the Lyon xenodochium, its establishment was the key point in the canons of the fifth Council of Orléans (549).117

“You have the poor among you always” (Matthew 26:11) — and they are a pretty constant feature of references to the Quadripartum. Captives, by contrast, are not. Only one version of the Quadripartum, that to be found in the first Council of Orléans (511), allocates a quarta for the ransom of those taken prisoner.118 But ecclesiastical involvement in the ransoming of captives is documented not just in the Quadripartum. A law of Honorius and Theodosius II from 408 charges clergy with ensuring the return of freed captives to their homes.119 It is also a regular is-sue in ecclesiastical literature. Ambrose had to defend himself for having melted down liturgical vessels to ransom captives.120 Bill Klingshirn has traced the influence of Ambrose’s actions in ransoming captives on Augustine, Hilary of Arles, Deogratias of Carthage, Caesarius of Arles, and Maroveus of Poitiers, and has noted that Patrick regarded the transfer of thousands of solidi to the Franks for the redemption of captives as a custom (consuetudo) of Roman and Gallic Christians.121 For both Justinian122 and the Merovingian bishops at the Council of Clichy (626–627),123 the ransom of captives was the one circumstance in which the melting down of liturgical plate was justified. And Gregory the Great was firmly of the same opinion.124 It was, nevertheless, a questionable action: the Council of Agde noted the significance of the initial donation.125 Clearly, from the Church’s point of view, it was better to draw on funds that were set aside as a matter of course, than to melt down liturgical vessels.

To judge by the distribution of our evidence, there were periods when the fate of captives was more pressing than at others. Klingshirn has stressed the significance in ransoming captives in the activities of Caesarius of Arles.126 There is an impressive cluster of evidence on either side of 500 for similar activity. Avitus of Vienne played a key role in ransoming captives taken by Gundobad in the course of the Burgundian raid on Liguria in c. 490.127 In the Liber Pontificalis, pope Symmachus (498–514) is remembered for his ransoming prisoners “throughout the Ligurias, Milan and various provinces.”128 As we have already noted, the ransom of captives is specifically provided for in the version of the Quadripartum to be found in Orléans I in 511.

In addition to the evidence for the ransoming of captives in the decades on either side of 500, we have a substantial body of evidence for the activity in the late sixth and early seventh centuries in the letters of Gregory the Great. We hear, for instance, of the priest Tribunus, who was ransomed for 12 solidi, but was unable to repay the sum.129 The pope thanked Theoctista and Andrew for their gift of 30 solidi, half of which was spent on ransoming people from Cotrone who had been seized by the Lombards.130 This, one might note, was something of a bargain, given that a priest had to raise 12 solidi, while Faustinus was faced with a demand for 130 solidi to secure the freedom of his daughters.131 The value of a captive varied according the status of the individual, and those who took prisoners clearly understood as much. The cost of the Lombard threat was something that Gregory emphasized in his correspondence with the empress Constantina, wife of Maurice.132 And references to ransom are to be found in other letters preserved in the pope’s Register.133

Prisoners, it would seem, were more of a feature of the period after the establishment of the Successor States, when rival kingdoms were plundering their neighbors, than they were of the period of the barbarian settlements — no doubt slaves were more useful to settled barbarians than they were to migratory peoples. At such moments they placed huge demands on the resources of the Church, alongside the other demands to be found in the Quadripartum.

As has been noted by numerous scholars, the act of almsgiving came to be envisaged as something which might help secure the salvation of the donor. Salzman has pointed to the centrality of the contribution of pope Leo the Great, noting that forty out of his surviving 96 sermons are concerned with charity — in sermon 78, for instance, he insisted on the need to provide food for the poor, help for the lame, and ransom for captives, all actions that would increase a donor’s piety, and aid his or her salvation.134 Christian charity, as Leo’s sermons make plain, occupied a central place in what Brown and others have called the spiritual economy. Acts of charity were part of a set of negotiations in which a man or woman might store up treasure in heaven for the future. The economic metaphor has been most fully ex-plored by Valentina Toneatto in Les banquiers du Seigneur, in which the bankers of the Lord are the bishops and monks of the fourth to ninth centuries.135

But it is important to note the financial realities that lay behind the metaphors of a Christian economy. The acquisition of land and treasure by the Church, and the allocation of diocesan revenues according to the formula of the Quadripartum, amounts to a very considerable “redistributive process,” to recall the definition of temple societies given by Appadurai and Appadurai Breckenridge; not only did the Church amass vast amounts of land, but dioceses also distributed the revenues from that land (as well as the income from other payments and from the oblations of the pious) according to predetermined formulae, while monasteries employed their revenues to provide for monks and nuns, and for the performance of religious cult. And it is worth bearing in mind how much it cost to perform the liturgy.

This Christian economy was not a substitute for an earlier pagan one. Anyone familiar with the archaeological sites of the Classical World might instinctively assume that the model of a temple society could more reasonably be applied to the Roman Empire of the pagan period than to the Christian Empire that followed. For the present we should note that Roman religion did not, apparently, depend on large-scale property endowments — although the temples of the Pharaohs and of the cities of the Hellenistic Levant seem to have done so before the Roman conquest of the eastern Mediterranean. Thereafter temples clearly did own some land, but apparently not a great deal; the majority of donations to temples seems to have taken the form of treasure, for which we have the evidence of inscriptions, like that from the temple of Isis at Nemi.136 Most priesthoods, however, seem to have been honorific; pagan priests continued to live in their own properties, and draw on their own income, and their cultic duties were rarely such as to occupy large periods of time, unlike those of monks, nuns, or some members of the Christian clergy. In other words, the funding of the latter and of church buildings differed substantially from the funding of religion in the period before Constantine. Julian clearly understood that the structure of the Church was different from that of paganism, and he wished to introduce what he saw as the merits of Christian organization into revivified pagan cult.137

Christian churches, as is clear from the Quadripartum and from the Visigothic Tertia, were usually expected to support their congregations economically as well as spiritually — there was provision for cult, for the poor, and for captives. Pagan temples in some cases, to judge from the evidence of inscriptions in Lydia and Phrygia, provided some care for their communities, especially with the occasional provision of feasts.138 However, there are better precedents for the distribution of Church revenue to support the poor and to ransom captives in imperial legislation than in our evidence for pagan religious behavior. The late-Roman State did show some concern for captives, although increasingly there was a recognition that bishops might be involved in their ransom, even allowing for the sale of Church property and goods to raise funds.139

An impressive array of scholarship has explored the spiritual economy of Late Antiquity as a metaphor within the quest for salvation. The spiritual economy was, however, a matter of real economics, which involved a major process of redistribution, hence my emphasis not only on the scale of the transfer of property to the Church, but also on the ensuing redistribution of wealth, which is most sharply characterized by the injunctions of the Quadripartum and the Tertia.

Heinz L.Boerder, Wikimedia CommonsCertainly, economic historians have noted the existence of Church property. For instance, Jairus Banaji has commented on the transfer of land to the Church, especially in Egypt140 and Asia Minor,141 but he portrays the Church as simply an extension of the aristocracy: “the increased weight of institutional landholders such as the Church and the monasteries (the only other groups of any significance) also suggests that the countryside of late Byzantine Egypt was now firmly under the control of the most powerful landholders (above all the aristocracy).”142 There is nothing here to suggest that the Church was involved in a redistributive process that differed from that of the secular aristocracy. So too, Tom Brown, while noting that churchmen and soldiers ended up as the major landowners in Italy, concentrates his attention on gentlemen and officers, and not on clergy.143

Of course, the socio-economic structure of the seventh-century West, especially in the area of the Exarchate, where the demands of the Empire and the army were unlike anything to be found in Francia and Spain, involved very much more than the redistribution of wealth to and by the Church. Indeed, the survival of the tax system in Byzantine Italy had significant implications for church finances in the peninsula.144 But I would argue that this redistributive process was a, if not the, dominant mode of distribution in the late-sixth- and seventh-century West, and not only in Francia.145

In other words, I would argue that what Peter Brown and other students of spirituality, including Valentina Toneatto, have presented in terms of spiritual ideology — “Treasure in Heaven” — can actually be envisaged as an economic model, and one that differs fundamentally from that of the Empire in the early fourth century. It involved the transfer of very large quantities of wealth, both treasure and, more significantly, land, which was conveyed to the Church, the proceeds of which were then redistributed to churchmen, the poor, the captives, and to the provision of cult. In the terms set out by Appadurai and Appadurai Breckenridge, this is a redistributive process.

Endnotes

- I deliberately use the phrase coined by Annette Weiner, Inalienable Possessions: The Paradox of Keeping-While-Giving (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992). For its application to the Carolingian world, see Gaëlle Calvet-Marcadé, Assassin des pauvres: l’église et l’inaliénabilité des terres à l’époque carolingienne (Turnhout: Brepols, 2019), 105–8. For differing practices with regard to alienation in Gaul and Italy, Merle Eisenberg and Paolo Tedesco, “Seeing the Churches Like the State: Taxes and Wealth Redistribution in Late Antique Italy,” Early Medieval Europe 29, no. 4 (2021): 505–34, at 515–19.

- Gregory I, Register, 1.23, 2.1, 3.3, 7.23, ed. Dag Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina 140–140A (Turnhout: Brepols, 1982), 21, 90, 148–49, 474–78.

- Council of Epaon (517), c. 5, ed. Brigitte Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens (VIe–VIIe siècles), 2 vols., Sources Chrétiennes 353–354 (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1989), vol. 1, 104.

- Council of Orléans IV (541), cc. 7, 18, 26, ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 1, 270, 276, 280.

- Council of Braga II (572), c. 5, ed. José Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos (Madrid: C.S.I.C., 1963), 83. Paul Fouracre, “Lights, Power and the Moral Economy of Early Medieval Europe,” Early Medieval Europe 28, no. 3 (2020): 367–87, esp. 370–71.

- Valerio Neri, I marginali nell’Occidente tardoantico: poveri, “infames” e criminali nella nascente società cristiana, Munera 12 (Bari: Edipuglia, 1996), 114–15; Robert Godding, Prêtres en Gaule mérovingienne (Brussels: Sociétè des Bollandistes, 2001), 346–49.

- Eugippius, Vita Severini, 17–18, ed. Philippe Régerat, Eugippe, Vie de saint Séverin, Sources Chrétiennes 374 (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1991), 226–31.

- Caesarius, Sermons, 13, 3; 33, 1; 71, 2; 229, 4, ed. Germain Morin, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina 103–104 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1953); Neri, I marginali, 115–16.

- Council of Mâcon II (585), c. 6, ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 2, 464. A.H.M. Jones, “Church Finance in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries,” Journal of Theological Studies 11 (1960): 84–94, at 85. Also, Neri, I marginali, 113–16.

- Pelagius I, ep. 25, 32, ed. Pius M. Gasso and Columba M. Batlle, Pelagii Pa-pae epistolae quae supersunt (556–61) (Montserrat: In Abbatia Montisserati, 1956), 79–80, 88–89; Jones, “Church Finances in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries,” 91; Council of Braga II (572), c. 2 and Council of Toledo VII (646), 4, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 81–82 and 254–55.

- Jan-Olof Tjäder, Die nichtliterarischen Lateinischen Papyri italiens aus der Zeit 445–700, 2 vols. (Lund: Gleerup, 1955–1982), vol. 1, 186–88, n. 31; Jones, “Church Finance in the Fifth and Sixth Centuries,” 92.

- Eucherius of Lyon, letter to Philo, ed. Alain Dubreucq, “Les sources textuelles relatives aux monastère de l’Île-Barbe au Haut Moyen Âge” (forthcoming).

- Simplicius, ep. 1 (475), ed. Andreas Thiel, Epistolae Romanorum Pontifi-cum Genuinae (Braunschweig: Brunsbergae, 1868), vol. 1, 176: “de reditibus ecclesiae et oblatione fidelium quod deceat nescienti, nihil licere permittat, sed sola ei ex his quarta portio remittantur. Duas ecclesiasticis fabricis et erogationi peregrinorum et pauperum profuturae […].”

- Gelasius, ep. 14.27, ed. Thiel, Epistolae Romanorum Pontificum Genuinae, vol. 1, 378: “Quatuor autem tam de reditu quam de oblatione fidelium, prout cujuslibet ecclesiae facultas admittit, sicut dudum rationabiliter est decretum convenit fieri portiones; quarum sit una pontificis, altera clericorum, pauperum tertia, quarta fabricis applicanda.”

- Gregory I, Register, 9.36, 39, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 925–29, 934–36; Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, 1.27, http://www.the-latinlibrary.com/bede.html; Bertram Colgrave and Roger Mynors, trans., Bede’s Ecclesiastical History of the English Nation (Oxford: Clarendon, 1969), 41–54. The most recent edition of the Responsiones is that by Valeria Mattaloni, Rescriptum beati Gregorii papae ad Augustinum episcopum seu Libellus responsionum (Florence: Sismel, 2017).

- Gregory, Register, 5.27, 39; 8.7; 9.144; 11.22; 13.45, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 294, 314–18, 695, 892–93, 1051–52.

- John the Deacon, Vita Gregorii, 2.24, Patrologia Latina 75, cols. 96–97. Jeffrey Richards, Consul of God: the Life and Times of Gregory the Great (Lon-don: Routledge, 1980), 95.

- Agnellus, Liber Pontificalis ecclesiae Ravennatis, 60, ed. Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis, Corpus Christianorum, Continuatio Medievalis 199 (Turnhout: Brepols, 2006), 226–31.

- Agnellus, Liber Pontificalis ecclesiae Ravennatis, 117–18, 121, ed. Mauskopf Deliyannis, 288–89, 292–95.

- Council of Orléans I (511), c. 5, ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 1, 76.

- Bede, Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum, 1.27.

- Council of Orléans I (511), c. 5, ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 1, 76.

- Theodorus lector, Excerpta ex Historia Ecclesiastica, 2.55, Patrologia Graeca 86 (1865), cols. 211–12: “Romanae ecclesiae hunc esse morem, ut res immobiles non possideat, sed si forte possessiones obvenerint, confestim eas vendat, et pretium in tres partes distribuat, quarum una tradatur ecclesiae, altera episcopo, tertia clero; idem etiam fit in reliquis rebus, quae non sunt soli.”

- Council of Braga I (561), c. 7, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 68: “item placuit ut rebus ecclesiasticis tres aeque fiant portiones, id est una episcopi, alia clericorum, tertia in recuperationem vel in luminariis ecclesiae; de qua parte sive archipresbyter sive archidiaconus illam admin-istrans episcopo faciens rationem.”

- Ex concilio bracarense, 7, ed. Gonzalo Martínez Díez, El Epítome Hispánico. Una colección canónica española del siglo VII. Estudio y texto crítico (Santander: Universidad Pontificia de Comillas, 1961), 174: “De rebus ecclesiae tres fiant partes: episcopi, ecclesiae et clericorum.” My thanks to Dave Addison for supplying me with this reference.

- Council of Braga II (572), c. 2, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 81–82.

- Council of Tarragona (516), c. 8, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 36–37.

- Council of Mérida (666), cc. 10, 14, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 332–33 and 335. E.A. Thompson, The Goths in Spain (Oxford: Clarendon, 1969), 298–99. See also Council of Toledo IV (633), c. 33, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 204 and Council of Toledo IX (655), c. 6., ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 301.

- Council of Toledo IV (633), c. 32, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 204.

- Council of Toledo V (636), c. 1, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 226–27.

- Council of Toledo X (656), item aliud decretum, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 322–24. I am indebted to Dave Addison, for drawing my attention to the importance of this document.

- Vitas sanctorum Patrum Emeretensium, 5.3, ed. Antonio Maya Sánchez, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latinorum 116 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1992), 50.

- Isidore, De officiis ecclesiasticis, 2.5, 18–19, ed. Christopher M. Lawson, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latinorum 113 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1989); 56–64, 83–89; Isidore, Sententiae 3.48.7–8; 3.49.3; 3.50.4, 6; 3.52.12; 57, ed. Pierre Cazier, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina 111 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1998), 298, 300–301, 302, 307; Jamie Wood, Politics of Identity Visigothic Spain: Religion and Power in the Histories of Isidore of Seville, Brill’s Series on the Early Middle Ages (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2012), 140, 146. On the poor in the Sententiae, see also Dolores Castro and Michael J. Kelly, “Isidore’s Sententiae, the Liber Iudiciorum, and Paris BnF Lat. 4667,” Visigothic Symposium 4 (2020–2021): 144–68, at 155.

- Leges Visigothorum, 1.2., ed. Karl Zeumer, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Leges Nationum Germanicarum 1 (Hanover: Hahn, 1902), 40–42.

- Leges Visigothorum, 2.1.30, ed. Zeumer, 77–78.

- Isidore, Historia Gothorum, 64, ed. and trans. Cristobal Rodríguez Alonso, Las Historias de los Godos, los Vandalos y los suevos de Isidoro de Sevilla (León: Centro de Estudios e Investigación “San Isidoro,” 1975), 278–89; Kenneth Baxter Wolf, trans., Conquerors and Chroniclers of Early Medieval Spain (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1999), 108.

- Council of Toledo IV (633), c. 75, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 217–22.

- Apostolic Canons, 8.47, 41. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf07/anf07.ix.ix.vi.html. I am indebted to Robert Wiśniewski for the reference.

- Justinian, Novellae, 3.3; 65; 123; 131.9, 11, 13, ed. Rudolf Schöll and Wilhem Kroll, Corpus Iuris Civilis, Novellae, 6th edn. (Berlin: Weidemann, 1928), 23–24, 339, 658, 659, 661–62; David J.D. Miller and Peter Sarris, trans., The Novels of Justinian: A Complete Annotated English Translation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

- Ewa Wipszycka, Les ressources et les activités économiques des églises en Égypte du IVe au VIIIe siècle (Brussels: Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, 1972), 121–53.

- John the Deacon, Vita Gregorii, 2.24; Richards, Consul of God, 95.

- Peter Llewellyn, Rome in the Dark Ages (London: Constable, 1971), 137–38.

- Rosamond McKitterick, Rome and the Invention of the Papacy: The “Liber Pontificalis” (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 56–57, 135–36. For the importance of the deacons in Rome see now Conrad Leyser, “Through the Eyes of a Deacon: Lesser Clergy, Major Donors, and Institutional Property in Fifth-Century Rome,” Early Medieval Europe 29, no. 4 (2021): 487–504.

- Anna Leone, Changing Townscapes in North Africa from Late Antiquity to the Arab Conquest (Bari: Edipuglia, 2007), 98–99.

- On the diaconiae see Neri, I marginali, 102–5.

- Gregory I, Register, 11.17, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 886.

- Gregory I, Register, 5.25, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 292–93.

- Gregory I, Register, 10.8, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 834.

- Codex Carolinus, 84, ed. Wilhelm Gundlach, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Epistolae 3, Merowingici et Karolini Aevi (Berlin: Weidmann, 1892), 619–20. Rosamond McKitterick, Dorine van Espelo, Richard Pollard, and Richard Price, trans., Codex Epistilaris Carolinus: Letters from the Popes to the Frankish Rulers, 739–891 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2021), 378–80.

- Neri, I marginali, 104–5.

- Ibid.,62.

- Gregory I, Register, 13.45, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 1051–52: “de reditibus ecclesiae quartam in integro portionem ecclesiae tuae clericis secundum meritum vel officium sive laborem suum”; John R.C. Martyn, trans., The Letters of Gregory the Great, 3 vols. (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 2004), vol. 3, 859.

- Gregory I, Register, 8.7, 9.144, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 524, 695.

- Agnellus, Liber Pontificalis ecclesiae Ravennatis, 60, ed. Mauskopf Deliyannis, 226–31.

- Agnellus, Liber Pontificalis ecclesiae Ravennatis, 117–18, 121, ed. Mauskopf Deliyannis, 288–89, 292–95.

- Gregory I, Register, 5.27, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 294.

- Gregory I, Register, 13.45, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 1051–52.

- Gregory I, Register, 11.22, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 892–93.

- Gregory I, Register, 13.27, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 1028–29.

- Council of Mérida (666), c. 16, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 336–37.

- Council of Toledo XVI (693), c. 5, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 501–2.

- Council of Carpentras (527), c. 1, ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 1, 146.

- Council of Toledo IV (633), c. 33, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 204.

- Gregory I, Register, 13.45, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 1051–52. See also Neri, I marginali, 9 7.

- Council of Orléans I (511), c. 14, 15, ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 1, 80.

- Council of Orléans III (538), c. 5, ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 1, 234.

- Gregory of Tours, Decem Libri Historiarum, 4.32, 7.29, ed. Bruno Krusch and Wilhelm Levison, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum 1.1 (Hanover: Hahn, 1951), 166, 346–49; Liber de virtutibus sancti Martini, 1.31; 2.22, 46, ed. Bruno Krusch, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum 1.2 (Hanover: Hahn, 1885), 153, 166, 175; Liber de virtutibus sancti Juliani, 9, 12, 38, ed. Bruno Krusch, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum 1.2 (Hanover: Hahn, 1885), 118–19, 119, 130; Neri, I marginali, 98–102.

- Council of Braga II (572), c. 2, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 81–82.

- William Klingshirn, “Charity and Power: Caesarius of Arles and the Ransoming of Captives in Sub-Roman Gaul,” Journal of Roman Studies 75 (1983): 183–203; Pauline Allen and Bronwen Neil, Crisis Management in Late Antiquity (410–590 CE): A Survey of the Evidence from Episcopal Letters, Vigiliae Christianae Supplement 121 (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2013), 39–43; Bronwen Neil, “Crisis and Wealth in Byzantine Italy: The Libri Pontificales of Rome and Ravenna,” Byzantion 82 (2012): 279–303.

- Ruth Leader-Newby, Silver and Society in Late Antiquity: Functions and Meanings of Silver Plate in the Fourth to Seventh Centuries (Aldershot: Ash-gate, 2004), 61–66.

- Rupert Bruce-Mitford, “The Art of the Codex Amiatinus,” Journal of the British Archaeological Association, 3rd ser., 32 (1969): 1–25 and plates, and Jarrow Lecture (1967).

- Gregory I, Register, 1.54, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 6 7.

- Paul Fouracre, “Eternal Light and Earthly Needs: Practical Aspects of the Development of Frankish Immunities,” in Property and Power in the Early Middle Ages, ed. Wendy Davies and Paul Fouracre (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 53–81; Paul Fouracre, “Framing and Lighting: Another Angle on Transition,” in Italy and Early Medieval Europe, ed. Ross Balzaretti, Julia Barrow, and Patricia Skinner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 305–14; Paul Fouracre, “Lights, Power and the Moral Economy”; Jo-anna Story, “Lands and Lights in Early Medieval Rome,” in Italy and Early Medieval Europe, ed. Balzaretti, Barrow, and Skinner, 315–38: Stefan Esders, Die Formierung der Zensualität (Ostfildern: Thorbecke, 2010); Paul Fouracre, Eternal Light and Earthly Concerns: Belief and the Shaping of Medieval Society (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2021), 57, 60, 62, 68.

- Diplomata Merowingica, 171, ed. Theo Kölzer, Die Urkunden der Merowinger, 2 vols., Monumenta Germaniae Historica (Hanover, 2001), vol. 1, 424–26. The value of the charter has been questioned by Simon Loseby, “Marseille and the Pirenne Thesis II: Ville Morte,” in The Long Eighth Century: Production, Distribution and Demand, ed. Inge Lise Hansen and Chris Wickham (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2000), 167–93, at 187. Certainly, it does not provide evidence for goods reaching Corbie, but it surely does provide evidence for goods being taxed in Marseille.

- Fouracre, “Eternal Light and Earthly Needs,” 70.

- Council of Braga I (561), c. 7, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 68.

- Liber Pontificalis, 34.14–15, ed. Louis Duchesne, “Liber Pontificalis”: Texte, Introduction et Commentaire, 2 vols. (Paris, 1886–1892), vol. 1, 174–75; Raymond Davis, trans., The Book of Pontiffs: The Ancient Biographies of the First Ninety Roman Bishops to AD 715, rev. edn. (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000), 17–18.

- P.S. Kanaka Durga and Y.A. Sudhakar Reddy, “Kings, Temples and Legitimation of Autochthonous Communities: A Case Study of a South Indian Temple,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 35 (1992): 145–66, at 155–57.

- Jean-Michel Carrié, “Les distributions alimentaires dans les cités de l’empire romain tardif,” Mélanges de l’École française de Rome 87 (1975): 995–1101, at 1012, 1030–32.

- John Rowland Rea, ed., The Oxyrhynchus Papyri, XL (London: The Egypt Exploration Society, 1972), 8.

- Codex Theodosianus, 14.18, https://droitromain.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/.

- Michèle Renée Salzman, “From a Classical to a Christian City: Civic Evergetism and Charity in Late Antique Rome,” Studies in Late Antiquity 1 (2017): 65–85.

- Bronwen Neil, “Imperial Benefactions to the Fifth-century Roman Church,” in Basileia: Essays on Imperium and Culture in Honour of E.M. and M.J. Jeffreys, ed. Geoffrey Nathan and Lynda Garland (Sydney: University of New South Wales, 2011), 55–66.

- Codex Theodosianus, 14.17.5, https://droitromain.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/. Salzman, “From a Classical to a Christian City,” 72.

- Justinian, Pragmatic Sanction, Novellae Appendix constitutionum dispersarum, 7, ed. Schöll and Kroll, 799–802; Salzman, “From a Classical to a Christian City,” 77.

- Gregory I, Register, 1.37, 57 (on members of the senatorial class); 1.65; 2.18, 21; 4.28; 8.35; 9.110, 137, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 44, 69, 74–75, 104–5, 108, 400–401, 662, 688. Peter Brown, Poverty and Leadership in the Late Roman Empire (Lebanon: University Press of New England, 2002), 59; Gary B. Ferngren, Medicine and Health Care in Early Christianity (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 132.

- Julian, ep. 22, trans. Wilmer Cave Wright, The Works of the Emperor Julian, 3 vols. (New York: Putnam, 1923), 69–71.

- Eusebius, Historia Ecclesiastica, 6.43.11, ed. T.E. Page et al., trans. J.E.L. Oulton, Loeb Classics, 2 vols. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1942), 119.

- Gregory I, Register, 1.37, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 44. For Gregory’s information on poor relief, Neri, I marginali, 94–109.

- Gregory I, Register, 1.57, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 69.

- Gregory I, Register, 1.50, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 63–64.

- Gregory I, Register, 9.110, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 662.

- Gregory I, Register, 2.50, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 141–45.

- Gregory I, Register, 3.18, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 164–65.

- Gregory I, Register, 3.21, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 166–67.

- Gregory I, Register, 1.65, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 74–75.

- Gregory I, Register, 4.28, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 2 4 7.

- Gregory I, Register, 9.137, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 668.

- Gregory I, Register, 13.45, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 1051–52.

- Arnold Pöschl, Bischofsgut und mensa episcopalis: Ein Beitrag zur Geschich-te des kirchlichen Vermögensrechtes 1: Die Grundlagen (Bonn: P. Hanstein, 1908), 105–10.

- Neri, I marginali, 97–101.

- Peter Brown, Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350–550 AD (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 510, 513, 516.

- Gregory of Tours, Liber de virtutibus sancti Martini, 2.22, ed. Krusch, 166.

- Gregory of Tours, Liber de virtutibus sancti Juliani, 38, ed. Krusch, 130.

- Hincmar, Vita Remigii, 32, ed. Bruno Krusch, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum 3 (Hanover: Hahn, 1896), 336–40; Neri, I marginali, 100.

- Council of Tours (567), c. 5, ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 2, 354.

- Gregory of Tours, Decem Libri Historiarum, 4.32, 7.29, ed. Krusch and Levison, 166, 346–49; Liber de virtutibus sancti Martini, 2.46, ed. Krusch, 175; Liber de virtutibus sancti Juliani, 9, 12, ed. Krusch, 118–19, 119.

- Gregory of Tours, Decem Libri Historiarum, 7.29, ed. Krusch and Levison, 346–49.

- Neri, I marginali, 97–102.

- Gregory of Tours, Liber de virtutibus sancti Martini, 1.31, ed. Krusch, 153.

- Oblations are mentioned in the Council of Braga II (572), c. 2 and the Council of Toledo IV (633), c. 33, but not in Council of Mérida (666), c. 16, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 81–82, 204, 336–37.

- See Peregrine Horden, “Public Health, Hospitals, and Charity” (forthcoming).

- Cyprian of Toulon, et al., Vita Caesarii, 1.20, ed. Bruno Krusch, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores Rerum Merovingicarum 3 (Hanover: Hahn, 1896), 464; William Klingshirn, trans., Caesarius of Arles, Life, Testament, Letters (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1994).

- Mark Alan Anderson, “Hospitals, Hospices, and Shelters for the Poor in Late Antiquity,” PhD diss., Yale University, 2012.

- Gregory of Tours, Liber de virtutibus sancti Martini, 2.27, ed. Krusch, 169.

- Gregory of Tours, Decem Libri Historiarum, 5.45, ed. Krusch and Levison, 254–46.

- Council of Orléans V (549), ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 1, 300–27.

- Council of Orléans I (511), c. 5, ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 1, 76.

- Codex Theodosianus, 6.2, https://droitromain.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/.

- Ambrose, De Officiis, 2.15, 28, ed. Ivor J. Davidson, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), vol. 2, 276, 284. See also Allen and Neil, Crisis Management in Late Antiquity, 40–41; Neil, “Crisis and Wealth in Byzantine Italy”; Michèle Renée Salzman, “The Religious Economics of Crisis: The Papal Use of Liturgical Vessels as Symbolic Capital in Late Antiquity,” Religion in the Roman Empire 5, no. 1: Transformations of Value: Lived Religion and the Economy (2019): 125–41, at 132; Neri, I marginali, 112, n. 115, for a fuller list. See also Robert Wiśniewski, “Clerical Hagiography in Late Antiquity,” in The Hagiographical Experiment: Developing Discourses of Sainthood, ed. Christa Gray and James Corke-Webster (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2020), 93–118, at 108–9.

- Klingshirn, “Caesarius of Arles and the Ransoming of Captives,” 186.

- Codex Iustinianus, 1.2.21 (529), https://droitromain.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/; Justinian, Novellae, 65; 108; 115; 120.10 (544); 123.37; 131.11, 13, ed. Schöll and Kroll, 339, 513–14, 589–91, 620–21, 659–60, 661–62.

- Council of Clichy (626–627), c. 25, ed. Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens, vol. 2, 542.

- Gregory I, Register, 7.13, 35, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 462–63, 499–98.

- Council of Agde (506), c. 7, ed. Charles Munier, Concilia Galliae, c. 314–c. 506, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina 148 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1963), 195–96. Salzman, “The Religious Economics of Crisis,” 132, cites the Council of Arles (314), c. 14, ed. Munier, but this surely relates to the traditio of sacred objects in the course of the previous period of persecution.

- Klingshirn, “Caesarius of Arles and the Ransoming of Captives,” 186.

- Ennodius, Vita Epifani, 171–81, ed. Frideric Vogel, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Auctores Antiquissimi 7 (Berlin: Weidmann, 1885), 105–7.

- Liber Pontificalis, 53.11, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 263; Neil, “Crisis and Wealth in Byzantine Italy,” 289–90.

- Gregory I, Register, 4.17, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 235–36.

- Gregory I, Register, 7.23, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 477–78.

- Gregory I, Register, 7.35, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 498–99.

- Gregory I, Register, 5.39, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 314–18.

- Gregory I, Register, 3.40, 55; 4.32, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 185–86, 204, 251–52.

- Leo, sermon 78, ed. Antonius Chavasse, Leo Magnus Tractatus, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latinorum 138 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1978); Salzman, “From a Classical to a Christian City,” 67–68, 74–75.

- Valentina Toneatto, Les banquiers du Seigneur: Évêques et moines face à la richesse (IVe–début IXe siècle) (Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2012).

- Paolo Liverani, “Osservazioni sul Libellus delle donazioni Costantiniane nel Liber Pontificalis,” Athenaeum 107 (2019): 169–217, at 183–84. See the general comments of Dominic Janes, God and Gold in Late Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 44.

- Julian, ep. 20, trans. Cave Wright, 55–61.

- Marijana Ricl, “Society and Economy of Sanctuaries in Roman Lydia and Phrygia,” Epigraphica Anatolica 35 (2003): 77–101.

- Codex Justinianus, 1.2.21, https://droitromain.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/; Justinian, Novellae, 65; 120, 10, ed. Schöll and G. Kroll, 339, 589. See in general, Klingshirn, “Charity and Power,” 184–87; Claudia Rapp, Holy Bishops in Late Antiquity: The Nature of Christian Leadership in an Age of Transition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 224–31; Salzman, “The Religious Economics of Crisis,” 138–39.

- Jairus Banaji, Agrarian Change in Late Antiquity: Gold, Labour, and Aristocratic Dominance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), 118, 128.

- Ibid., 173, 182.

- Ibid., 128.

- Thomas S. Brown, Gentlemen and Officers: Imperial Administration and Aristocratic Power in Byzantine Italy, A.D. 554–800 (Rome: British School at Rome, 1984), 195.

- The differences are well brought out in Eisenberg and Tedesco, “Seeing the Churches Like the State,” 509–19.

- For other patterns of distribution, see, for example, Banaji, Agrarian Change in Late Antiquity; Jairus Banaji, Exploring the Economy of Late Antiquity: Selected Essays (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016); Jean-Pierre Devroey, Économie rurale et société dans l’Europe franque (VIe–IXe siècles), 1: Fondements matériels, échanges et lien social (Paris: Belin, 2003); Jean Durliat, De l’Antiquité au Moyen Âge: L’Occident de 313–800 (Lyon: Ellipses, 2002); Elisabeth Magnou-Nortier, Aux origines de la fiscalité moderne: le système fiscal et sa gestion dans le royaume des Francs à l’épreuve des sources (Ve–XIe siècles) (Geneve: Droz, 2012); Michael McCormick, Origins of the European Economy: Communications and Commerce AD 300–900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001); Chris Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean 400–800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

Chapter 3 (51-77) from The Christian Economy in the Early Medieval West: Towards a Temple Society, by Ian N. Wood (Punctum Books, 02.14.2022), published by Punctum Books under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.