Various performances that took place in and around churches served the basic tenet of Christianity.

By Dr. Kathryn M. Rudy

Bishop Wardlaw Professor of Art History

University of St. Andrews

Introduction

In addition to Gospels and missals, other types of manuscripts were written for use by church officials to conduct ceremonies. Masses required music, some of which a priest himself intoned. The grander the Mass, the more actors it required, and each of those actors needed a particular book type that contained the script for his part. Masses with a choral component required the largest manuscripts in Christendom, their format scaled up to enable numerous choristers to read simultaneously from the page. These actors may have considered their chanting unexceptional, merely their quotidian routines. The books they used in order to effect their performances were anything but.

Various performances that took place in and around churches served the basic tenet of Christianity: that it was a religion that promised bodily resurrection and everlasting life. Because of this, Christians and their ceremonies were preoccupied by death. The living prayed for the dead and paid professionals—priests, nuns, and monks—to pray for lay people after they died. To have large choral Masses sung for the dead would mitigate the chances of their souls spending eternity in Purgatory. This essay considers books used and gestures practiced in the service of liturgical singing and memorializing the dead. Normal liturgical actions, together with exceptional props, combined to commemorate death and formed an everyday part of worshippers’ lives. Signs of wear in the books record how clerics used them for these practices.

Choral Manuscripts

The choir psalter OBL, Ms. Canon. Liturg. 395, used in the Cathedral of St Lawrence in Trogir (Trau, Dalmatia), ca. 1450–1475, is in terrible condition. Alongside two other saints, the Blessed John Orsini, patron of the town, whose feast days are 26 June and 14 November, appears on the first text folio (Fig. 83). The dedication of St Lawrence Cathedral has been added to the calendar on 12 August. This book may be in its original binding, for the paste-down on the front cover comes from a fourteenth-century Italian missal. Dalmatia belonged to the Venetian domain after 1420, so books would certainly have been exchanged across the Adriatic in this period. Measuring 385 x 270 millimeters, this large manuscript could be used for liturgical performances by the choir, who would chant from it daily during the office. Its notes are large enough to be legible from some distance. I estimate that a group of six to eight people could sing from it simultaneously. Degradation of the parchment reveals the heavy use it has incurred. The noted text implies that it was designed to be sung. As with all service books which were read or sung over, this one has been attacked by damp breath. Cascading exhalations, expelling invisible droplets, have resulted in the oft-turned pages suffering from moisture and exposure, so that the lower corners of most folios have been damaged and repaired later with paper.

As part of his ritual of using this book, the choirmaster in charge of turning the folios must have touched the initials before singing the corresponding sections. With this large manuscript at arm’s length, he reached down in a dramatic gesture with his hand and touched the book so that his gesture would be visible to the whole choir. Imagining this is easier with my amateur photograph than the professional one provided by the library; I took the photo so that my hand is hovering above (not touching!) the initial, to provide a sense of scale and enactment (Fig. 84). When the choirmaster reached his hand in, he touched the area vigorously. This has left the first historiated initial P illegible and dislodged much of the tempera paint so that the subject is no longer discernible. Some of the sections of this psalter are more heavily used than others.

A begrimed section begins on folio 190v, with a historiated initial C (Cantate domino canticum novum), where the initial has also been rubbed to oblivion (Fig. 85).

The professional photograph, which captures the book as a three-dimensional object and not just a flat surface, as well as an amateur photograph that captures the entire opening show the context of use more effectively (Fig. 86). Perhaps the choirmaster habitually touched the initials in order to signal that reading or singing should begin. These gestures formed part of a performance that was as public as the Mass, but for an audience of choristers. His actions validated touching initials as an honorable way to add gravitas to the sacred words of the text. All of the members of the choir would by necessity have watched this action and normalized it. Did this literate group of spectators, as well as anyone witnessing the Mass with a view of the choir, adopt and absorb this lesson in book handling and subsequently apply it to their own books?

A significant number of large music manuscripts used across Europe have apparently been touched in a similar way. For example, in an antiphonary—a book of plainsong for the Divine Office—made for the use of the Benedictine Abbey of Marchiennes in northern France, a user has repeatedly touched the large opening initial (Fig. 87 and Fig. 88).

The manuscript opens with music for the feast of St Nicholas, and the accompanying initial depicts the enthroned Virgin and Child presented by the feted saint. On either side of the throne are two Fig.res in religious garb, who may be the founders of the abbey. On the left, Adalbert I of Ostrevent (d. ca. 652), a Frankish nobleman who was recognized as a saint and whose relics are in Douai. The woman on the other side of the throne may be his wife, Rictrude of Marchiennes (ca. 614–688), who converted the all-male house into a double abbey and became its first abbess. (In the thirteenth century, it reverted to a male-only house.) The figures in the image have been carefully targeted, especially the Virgin and Child, and the two local founders. It is as if the monk leading the plainchant touched the image with each recital, partly to ensure that all eyes were on the starting point of the numed text, and also to touch, literally, the operative characters in the founding narrative of their abbey. I will leave it to music historians to discuss how this touching gesture might relate to hand signals used by liturgical singers to coordinate the voices.

Choirmasters across Southern Europe adopted a similar practice in handling antiphonaries. As with the Dalmatian manuscript discussed earlier, a brightly illuminated Venetian antiphonary has large colorful images that mark the beginnings of sung passages (OBL, Ms. Douce A 1).1 A later collector cut out about a dozen of these initials; some have been taped back into their original positions, and some are mounted at the end of the manuscript into a small “album” of fragments. Signs of wear attest to their having been handled as a matter of practice. For example, an initial B with the Trinity has been wet-touched, where the user has targeted specific areas of the image: the thighs of Christ crucified, and the area of the blue sky on either side of God’s face (Fig. 89). It is almost as if the user were consciously trying to touch in the vicinity of the important elements, without marring the paint on those important details.

In the same manuscript, an image of St Augustine initiates a Mass to be sung in his honor (Fig. 90 and Fig. 91). One can imagine the choirmaster touching the image of the saint, both to venerate him and also to move all eyes to the beginning of the song, “Invenit se Augustinus longe esse a deo in regione dissimilitudinis tamquam audiret vocem…”2

This time, however, the user has had no qualms about touching the face of the saint. Is it possible that a different choirmaster wrought these two habits of practice?

A third fragment preserved in the manuscript (which may in fact have been cut from a different antiphonary) testifies to another type of precision-targeted touching (Fig. 92). The image shows St Gregory as a pope in a tripartite tiara performing his miraculous Mass. This time, the user (the choirmaster?) has touched the figure’s hands. That area of the image is now heavily abraded, but with difficulty one can see that Gregory is holding aloft the host. The user has repeatedly touched this miracle-inducing wafer.

There are no instructions telling singers or choirmasters to touch initials. They could have learned to do so by putting their hands where others’ hands had obviously been, or from following the lived models that their own choirmasters had set for them. An antiphonary is one of the few book types that is presented open and facing its primary audience, a group of singers gathered round it. Those who commissioned and painted them may have illuminated them in order to glorify God, while those who used them put the decoration to use. They instrumentalized the painted and gilt initials to foster group cohesion. Regarding the numed text together was something they did with their fingers.

Books and Holy Water

Whereas antiphonaries contain no instructions for handling the physical book, pontificals are full of such instructions. Pontificals prescribed rituals such as blessing holy water, blessing the baptismal font, performing baptisms and marriages, purifying a woman, sending off pilgrims, performing extreme unction, and burying the dead. These books contain the instructions for a clergyman—most often a bishop—to perform these tasks. Some are noted. Most are rubricated, with the instructions for the priest or bishop in red and the words he had to utter in black. As such, pontificals mandate several ceremonies that involve the pontifical itself, or other books exuding religious authority as actors in those ceremonies.

One pontifical, made for the Chapter of St Mary in Utrecht around 1450, which includes extraordinary illuminations attributed to the Master of Catherine of Cleves, depicts many of the ceremonies for which it also provides instruction, and as such reveals the central role books play in these ceremonies (Utrecht, Universiteitsbibliotheek, Ms. 400).3

On one folio, the painter has shown a disembodied hand that extends from the text block holding aloft a book, thereby putting on display the object featured in the ceremony (Fig. 93). The accompanying text tells the celebrant to kiss the Gospel book while saying “Pax tibi” (Peace be with you).

Likewise, on another folio, in the ceremony for blessing liturgical garments, the image depicts a bishop clutching a book—again, probably a Gospel book—which gives him the authority from God, channeled through the Evangelists, to make the sign of blessing over the chasubles (Fig. 94 and Fig. 95).

An acolyte further ceremonializes this process by sprinkling holy water. Depictions of such rituals show that the power of the book functions as an attribute of authority even when the book is closed. Evidence from the pages of other manuscripts reveals that books might remain open during rituals such as baptisms and last rites.

Pontificals were not the only books used for performing rituals. There is a type of book simply called a ritual. Some service books contain instructions for the use of holy water, and during some enactments, holy water splashed the service books themselves. A rubricated noted ritual, made in England in the third quarter of the fifteenth century for Sarum Use, has been splashed (OBL, Ms. Laud Misc. 267).4 In the short space of its 92 folios it has been repeatedly wetted with an aspergillum, a brush designed for sprinkling holy water. This manuscript even begins with a blessing of holy water (fol. 2) and contains instructions for blessing and performing baptism (fol. 4v). The pages near the end of the baptism section are awash with smeared ink (rather, red pigment with binder) from water damage from a dripping wet baby that has liquefied some of the rubrics, which were far more soluble than the black ink texts to be pronounced aloud.

This opening—used in conjunction with a ritual performed on infants—is the only one in the book bearing such a colorful array of stains (fols 13v–14r; Fig. 96). A laboratory sample might well indicate that the substance on these pages contains regurgitated milk and baby feces. Further aspergillum use, and therefore water damage, occurred at the folios for performing a marriage (fol. 15v), for the purification of a woman (fol. 26v), and for the blessing of a pilgrim (fol. 26v). An officiant has also used the aspergillum extensively during rituals relating to death—extreme unction (fol. 34r) and a burial service, which includes the office (fol. 49r) and Mass for the Dead (fol. 75r). There has been so much holy water sprinkled from fols 84 to 92 (the end of the book) that these pages are wrinkled and only faintly legible.

It is as if the officiant had used the book in the manner depicted in a panel depicting the Death of the Virgin, made for Clarissan nuns in Bohemia around 1400 (Fig. 97 and Fig. 98).

This painting once joined a pendant representing the Death of St Clare.5 Together they may have formed the backdrop for funerary rites in the convent. A dejected apostle holds the open book, and the priest looks into the pallid Virgin’s lifeless eyes while flicking holy water over book and body.

In the noted ritual, a rubric on folio 85v telling the official to use an aspergillum has been so effective that the user has nearly washed those very instructions away (Fig. 99).

Holy water can also be transported outdoors in an appropriately ceremonious vessel. Outdoor spaces marked by wayside crosses, city gates, churches, chapels, gallows, and structures that prompted Christian memory and signified justice were also sites where books and aspergilla were used. A miniature in a book of hours shows a priest leading a burial procession, his acolyte with holy water behind, followed by black-cloaked mourners, while a workman lowers the slim coffin into the ground (Fig. 100). In the image, and according to official procedure, only the cleric would carry a book to the grave. Signs of wear in their books suggest that laypeople copied clerics and subjected their private prayerbooks to rituals that mirrored those they witnessed clerics conducting.

A similar transmission occurred around rituals of other processions: priests (including bishops) holding manuscripts would lead people from the church to perform an outdoor ritual, and it appears that their books became damaged in the process. Analogous signs of use appear in the fifteenth-century processional cart of Gertrude of Nijvel (Nivelles), which has recesses for 21 panel paintings chronicling the life of the saint; these have been severely damaged by water, since the paintings were actually taken out on the cart once a year to circumambulate the town (Fig. 101).6 Her relics rode at the top of the cart, where they would be scintillatingly visible from a great distance, heralded by trumpet-blaring angels at the corners of the cart. (St Gertrude’s reliquary was lost and then reconstructed in the nineteenth century.) The panel paintings fit into the lower part of the cart, thus at eye level. Sometimes it rained during these outings, and as a result, the subjects of some of the paintings have become muddled and inscrutable. Damage from rain and from holy water provides clues as to how people used books out of doors, and how clerics might have used books in spaces other than at the altar.

Grand Obituary of Notre-Dame in Paris

Priests kissed and touched other service books related to the activities that they performed. For example, they commemorated deceased members of their congregation who had left money specifically for Masses to be said. These were to be performed daily, weekly, or annually on the anniversary of the donor’s death, for a certain number of years after their donors’ deaths. Churches maintained perpetual calendars to record members’ deaths and the Masses they had sponsored. Remembering the dead was the central obligation for the managers of a religion that promised to overcome death.

Most obituary manuscripts are not illuminated but take the form of a perpetual calendar ruled with large blank spaces for each day of the year to receive the names of future donors, together with a short list of their deeds. (Their form resembles that of the dismeesters of Bruges with obligations to be recorded in a perpetual calendar.) Such entries typically situate the deceased person socially, and then list the donations he or she made to the church. These could be monetary or in the form of books, building works, metalwork (such as chalices), vestments, or other goods that had to be upgraded or replaced from time to time. That way, each day a priest could read elegies of those who had died on that day, recognize their gifts, and pray annually for their souls. More elaborate configurations existed, such as an illuminated example made to commemorate the dead in the cathedral of Paris—the Grand Obituary of Notre-Dame (BnF, Ms. lat. 5185 CC). As Charlotte Stanford argues, the unique images in this manuscript provide a glimpse of late-medieval death culture, which also involved laying out the body in state, performing Masses, soliciting prayers for the dead, and visiting tombs.7 What neither she nor other commentators have discussed are the elaborate marks of wear in the book, which provide clues as to how the volume was handled in—I argue—a social context.

First inscribed around 1240–1270, the Grand Obituary records earlier deaths copied from other sources. Thus, its scribe recopied an older obituary manuscript (or possibly collated obituaries from loose sheets) to make a neat, new book. Scribes wrote subsequent obituaries onto the blank spaces expressly left for that purpose, and they created other, more elaborate obituaries (including illuminated ones) on separate leaves, bifolios, or more substantial quires, and then inserted them into the binding. These additions date from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, with the most recent ones added in the 1490s. They must have been inserted into the manuscript periodically and the book rebound. Its current nineteenth-century binding is so tight that the book opens only with difficulty, and the collation structure has been impossible to determine. Because of the tight binding, the library denied requests for professional photography.

The first part of the Grand Obituarycontains a perpetual calendar (fols 1r-6v), a guide for calculating the date in terms of kalens and ides (fols 7v-43v), short readings for each day of the year (fols 44r-72r), a martyrology arranged according to the calendar (fols 72v-129v), and a noted requiem Mass (fols 130r-137v). The bulk of the manuscript contains the obituaries, which are also arranged according to the calendar (fols 138r–358v). The final section of the obituaries, fols 328–58, comprises sundry added folios, many of which contain testimonies by the living promising donations to the church in the future. In other words, the function of the various parts of the manuscript are to figure out the date, to laud the appropriate saints and appreciate the benefactors on their annual date, to perform sung requiems for the benefactors, and to recognize and appreciate past and future donations. This manuscript of 358 leaves therefore comprehends original material copied in the thirteenth century, partly from older sources, with deliberate spaces left to fill in later; texts added to those spaces over the next several centuries; added folios and quires, made in the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, which have been bound into the book as close to the relevant date as possible; and later folios and quires added to the end of the manuscript in the fifteenth century, when it became impractical to insert them close to the date where they belonged. The manuscript marks a particular kind of time—commemorative time—a layered, circular time that demands certain actions.

These temporal layers make sense of the differential wear that the folios have incurred, which correspond to various actions. Specifically, different levels of wear reflect the age of the folio, the frequency with which it was read, and the way it was touched ritualistically. The most worn are the original, thirteenth-century parts of the manuscript, which were used daily, presumably until around 1500 (when the addenda cease). The sung part of the Mass for the Dead, copied in the original campaign of work, has been thoroughly degraded (Fig. 102). Filth emanates from the pores of the parchment in the lower third of the page, where generations of priests must have grasped the book when turning the folios. The corners fell into such tatters that medieval conservators repaired them, onto which the missing text and notes were copied. This was a common form of medieval conservation.8 Those repaired corners continued to be used and read, as evidenced by the thick fingerprints on the corners of the newer material. In fact, these replacements have become so worn that their parchment has become floppy.

That this once-crisp material has changed texture marks a haptic and sonorous change that is difficult to document. Normal photography of this manuscript fails to capture some of the information about the manuscript’s history of use that is immediately apparent to someone handling the manuscript now; however, backlighted photography reveals the dirt ground into the crevices, the shoreline between the original and replaced material, and the degree to which the fibers have been damaged through use (Fig. 103). Daily handling gave the pages a real beating.

The next most used parts are the original obituaries, those copied in 1240–1270, which were read once annually until approximately 1500—thus, for about 250 years. Someone who had been dead for 250 years would have had 250 annual Requiem Masses said for them, with priests turning to that folio in the book at least 250 times before the volume was retired. For example, fol. 311 forms part of the original material copied in the mid-thirteenth century, with an obituary for the first of December. Backlighting shows that the lower third, especially the corner, is replete with broken parchment fibers that transmit scant light and reveal heavy wear (Fig. 104). Hundreds of creases show up as dark lines that correspond to events of handling those folios. Some of the parchment has been worn so thin that it is nearly transparent. The wear on this and other folios from the original parts of the manuscript suggest that later priests took their duties to read perpetual Masses seriously.

More recent deaths would not have had time to accumulate so many commemorations, and consequently, obituaries added on extra leaves in the fifteenth century received significantly less wear. For example, fols 233–35 form part of an obituary for Lodovicus de Bellomonte, who died in 1492. Assuming this section was added shortly after his death, then it could have been in use for only about a decade, which is why the fibers of the parchment, photographed with backlighting, only reveal minimal damage (Fig. 105). The difference in the parchment creasing between this and the earlier leaves, in use for 200 years longer than this one, is literally palpable.9

Whereas the original parts of the manuscript appear in calendric order, as do the early additions (inscribed into spaces left for them), the later additions, which tend to be written on separate sheets or quires of parchment, were inserted only approximately where they belonged. A defined order for these pieces eroded in the fifteenth century, so that the final additions were simply slipped in at the end of the manuscript, without respect to the date of death. In other words, the last 31 folios (328–58) contain bits and bobs, written in dozens of hands over the course of the fifteenth century. Within this cumulative arrangement of folios and deaths, what is striking is the degree of physicality with which the priest—rather, series of priests spanning 250 years—interacted with the pages. They considered the book a site of continuous evolution.

The opening at fols 242v–243r provides a sense of the interactive nature of the Grand Obituary, which in turn reveals one aspect of how the book was used (Fig. 106). On the left side of the opening is part of the original material, containing segments organized around the calendar. In this case, the heading reads “xvii kalens Augusti,” which someone in a nineteenth-century hand has helpfully translated as “16 July.” That date marks the death of “Petrus de Kala vicarius sancti victoris in ecclesia parisiensi.” Notice of another death was added to the empty margin. The facing page (243r) contains the obituary of the former chancellor of the University of Paris Simon de Guiberville (d. 1320), inscribed on parchment added to the book shortly after his death. Thus, this opening alone contains original material inscribed around 1240–1270; texts inscribed later on original material; and added parchment in the form of single leaves, bifolios, and quires.

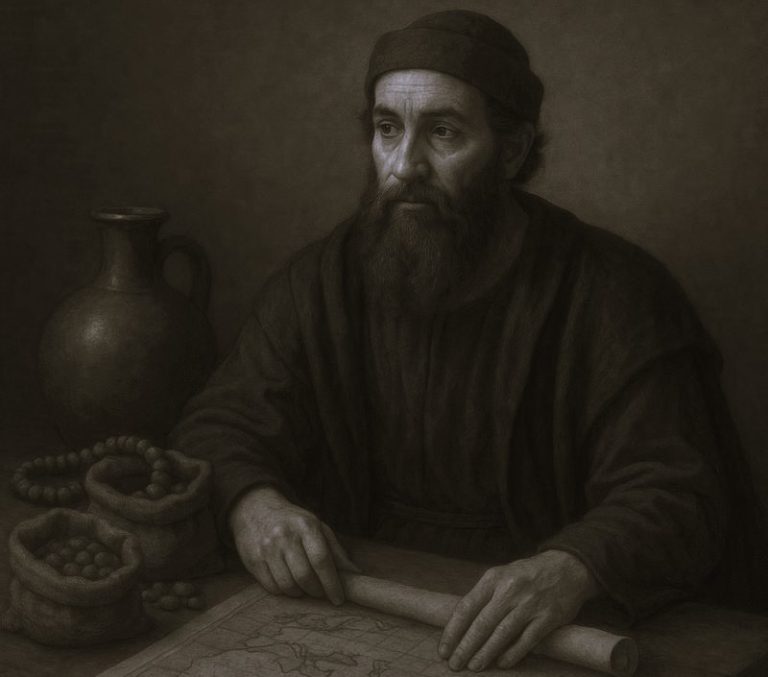

Eight of the parchment supplements, added in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, contain illuminations of, for the most part, portraits of the deceased, such as the one for Simon de Guiberville (Fig. 107). These make the absent one present, as does any portrait or icon; furthermore, the added images in this manuscript became targets for the physical attention of priests performing ceremonies involving the remembrance of the dead. These eight added illuminated obituaries span two centuries and show an evolution of imagery associated with Requiem Masses to honor the deceased. All of the images have been deliberately touched, as if their purpose were to supply another set of activities to the Requiem Mass, a multi-sensory component involving touching. Perhaps making physical contact with the remembered one was not dissimilar from touching relics, which not only honored the saint, but also reciprocally brought a tangible form of sanctity to the living person doing the touching. And perhaps the bookmakers even designed these portraits to be touched.

Simon Matifas de Bucy, bishop of Paris (d. 1304), appears in the earliest of these portraits (Fig. 108).10 In the image, Simon de Bucy lies in state, wearing the regalia of his episcopal office. At the head of the bier, a bishop conducts a Mass with the aid of a book—either a missal or a representation of this very obituary manuscript. A group of altar boys who carry the incense and holy water integral to the ritual accompany him. On one side the bier candles burn, while on the other mourners seated in melancholic poses read from their books, which are the size of portable psalters or personal prayer books. In other words, books direct the activity depicted in two areas of the image. While the represented official stands at a lectern and only touches the bottom margins of the book (which is, in fact, how the sung components of the Mass in this manuscript were held, as my earlier analysis demonstrates), the marks on the miniature reveal another way in which mourners touched it. These marks show that someone deliberately touched the image in three places: on the depicted processional cross and on the decoration immediately above it; and at the image of the mourner wearing blue in the corner. In the case of the first, the image of the cross often attracted book users, especially, one can imagine, priests who were trained to take an action at the sign of the cross in their books, or to kiss them, as prompted by this shape.

The wrinkles and wear at the bottom of the folio suggests that on many occasions a priest gripped the book open to this folio (Fig. 109). One can imagine that he turned the book to show the image to participants so that they might touch an image of a mourner, or that he might proffer the book so that the mourners in the audience could self-identify by touching the represented mourner. These are two plausible explanations for the heavy wear on this blue figure. Some of the paint has migrated to the facing folio, which suggests that a mourner wet-touched the melancholy figure.

While the image of Simon de Bucy may be the earliest example of this portrait type, the depiction of Cardinal Michel du Bec (d. 1318), copies it loosely (Fig. 110).11 Again, the body laid out in state fills the middle of the image. This time, the mourners in the foreground have been reduced to three. The candle-bearers have been relegated to the lower corner, and the officiating bishops have now multiplied to two and occupy the upper right corner. However, the most spectacular difference lies in how the image has been used. Rather extraordinarily, the large miniature has been touched repeatedly, smearing the pigment throughout the frame and beyond. In particular, vertical smears emanate into the upper margin, suggesting that the reader proffered the book to someone who then reached into it from the top edge to make contact with the image of the dead cardinal. Others have pulled the paint downward, as if someone oriented toward the book’s script had also reached in to touch it and then drew his hand back toward himself. The timid have touched the frame and the golden leaves in the margins. Within the frame, the image has been touched in multiple places over a series of ceremonial events. Celebrants have repeatedly touched the dead bishop’s face and scrubbed away the red pigment from the cloth of gold on which he lies. Pigment does not stick well to gold, so only moderate handling would send it to its fugitive state. More striking still is the level of grime on the bishop’s face itself. Others have touched both the miter on his head and what appears to be a red cardinal’s hat near his pillow, both kinds of headgear symbolizing his ecclesiastical office. Officials—possibly several of them layered over time—have also touched the image of the two bishops conducting, at the upper right. Did the officials identify with these figures and therefore touch them? Most surprisingly, the mourners in the foreground, especially the one in blue, have also been touched, and in fact, the entire checkered background has been touched, so that all of the gold is finger-burnished in the center of the image, and the linear pattern of the checkerboard has become blobby and misshapen.

In sum, there are several areas of targeted touching, plus large areas of diffuse touching. This may represent the handling of many priests over dozens or hundreds of years, but, given the diffusion of the smears, these marks indicate that multiple handlers touched it from different angles. Perhaps for the anniversary of Michel du Bec’s death, those gathered to hear his obituary were invited to participate in touching the represented body of the bishop. Maybe touching the book formed part of the requiem Mass, as a way to touch the deceased on the anniversary of his death date for years after his physical flesh had melted from his bones. Why they would touch Michel du Bec’s image but not Simon Matifas de Bucy’s is not clear. Perhaps Michel du Bec was thought to have healing powers, or he had a larger, more active group of bereaved, who continued to attend his anniversary Mass for years after his death. What is clear is that a specific set of rituals was carried out for these two men’s anniversaries, that those rituals differed, and that the signs of wear on the manuscript itself both recorded and then prescribed habits of touching that extended across a long time.

What of the other images added to the manuscript? A painted obituary was added for Lord Henry de Sucy, or Henricus de Suciaco, dated 8 December 1310 (fol. 315r; Fig. 111). Unlike the miniatures for Simon de Bucy and Michel du Bec, this shows not the deceased lying in state, but Mass being said in his memory.12 Perhaps the purpose of the miniature is to shape future behavior. The obituary states that Henry has left six denarios in perpetuity for Mass to be said in his honor, three for the deacon and three for the subdeacon. Like the other miniatures, this illumination has also been touched, and wet-touched at that. In particular, the user targeted the top of the frame with a wet finger and smeared the black ink on the chest of the officiating priest, the garments of the two assistants, and several places on the geometric background. Perhaps the officiating priest read Henry de Sucy’s obituary, with his long list of donations to the church, and wet-touched the image of the Mass, which mirrored the very one he was celebrating. The image did not lend itself to being touched by the gathered mourners, since it probably did not represent the deceased.

Similar in composition to the miniature for Henry de Sucy is the one heading the added obit for Hugues de Besançon, cantor, who died in 1320. A column-wide miniature depicts him celebrating (or possibly assisting at) Mass (Fig. 112).13 This image has not been touched in the same way as the other ones. There are some small areas of abrasion on the curtain and the altar cloth, and perhaps one wet fingerprint on the red chasuble, but it was not touched extensively and systematically, nor was the diaper background touched, nor the gold border decoration. In other words, the ritual enacted around some of the previous images was not enacted here.

An obituary for Girardus (Gérard) de Courlandon (d. 1319) made on an added bifolium was furnished with a column-wide miniature that was touched many times (Fig. 113). To emphasize his gifts, the miniature shows the deceased presented by a bishop-saint gifting a golden model of a church (or a chapel) to the Virgin and Child. Christ extends his arm as if eagerly accepting this munificence. This time, a constellation of wet fingermarks appears around and on the body of the Virgin, with a few additional wet marks on the body of the saint, and the area between Gérard and his gift.

Additionally, one or more people has vigorously wet-touched the gold decoration emanating from the top of the frame, which has liquefied the black outlines of the gold and caused the paint to transfer to the facing folio (Fig. 114).

Despite these enthusiastic wet-touchings, the fibers of the parchment do not bear heavy traces of use (Fig. 115), which suggests that the attention Gérard received came shortly after his death, after which his obituary fell into desuetude.

The added obituary of Simon de Guiberville, mentioned earlier, depicts the deceased, and provided several opportunities for touching. In the page-wide miniature (see Figs 107 and 108), he appears twice, first kneeling before the Virgin and Child, and then at a pulpit lecturing to a group of enraptured students.14 Simon was a secular canon of Notre-Dame of Paris (1303–1309), and also chancellor of the University of Paris from c. 1301 until 10 December 1309. A public intellectual, as it were, Simon de Guiberville participated in the debate on the trial of the Templars.15 Signs of wear reveal that his image, like that of Michel du Bec, was touched heavily with a diffuse pattern, indicating many people touching various parts of the page once. Perhaps on the anniversary of Simon’s death, an officiating priest located the decorated folio with his obituary and read it aloud. This may have happened every year from the first anniversary of Simon’s death until the early sixteenth century, when the book ceased to be used ceremonially; however, I suspect that most of the touching took place during living memory of the deceased. When reading the obituary, the priest may have turned the book toward the assembled audience to show them the illumination and to interact with it. They were apparently invited to touch the image and did so.

Whereas a single individual is likely to touch an image in the same place with each iteration of the ritual (as with a book owner touching a cult image in her book), and multiple people are likely to touch, say, an oath-swearing image in haphazard ways, here we find a third pattern: a few places on the miniature have been touched and have therefore attracted further touching. Previous priests (or mourners) set the finger tracks for future ones. Consequently, constellations of finger marks appear on the Virgin’s hem, in the diaper background above where Simon’s praying hands nearly touch Jesus’s, on Simon’s blue mantle, and on the bodies of the six students (especially the one clad in orange closest to the picture plane), on the diaper background in the very middle of the image, and on the gold border decoration, especially the boss and tri-petals near the lower right corner, and especially on the black-clad figure of Simon as a teacher. It seems, then, that various people who interacted with the image chose different areas to touch. Some of these people were priests, who touched the image in the course of animating the image before an audience, but some may have comprised Simon’s students, who were invited to touch the image. And what part of the image did they touch? The area showing their master preaching, in order to remember him as a teacher, and images of his students, in effect self-identifying with that element of the image.

This would explain why there are different patterns of wear for each of the figures: that a micro-culture of touching was present but subtly different for each obituary. In the case of Simon de Guiberville, perhaps the high degree of wear on his death-portrait was incurred by his many adoring students, who attended their teacher’s anniversary funeral Mass for a decade or more. This would also explain why many of them touched the image of Simon as a teacher, rather than Simon as a worshipper of Mary, and why some elected to touch the representation of his students.

More than 100 years passed before the final two images were added to the Grand Obituary. A quire inscribed around 1472 contains obituaries for two people: Lady Margaret of Roche-Guyon (Margareta de Rupe Guidonis) and Guillaume Chartier, the Bishop of Paris (1386–1 May 1472).16 These texts were written in one campaign of work on added parchment that now comprises fols 189–93. Margaret’s date of death is not recorded in the manuscript, because it is likely that she commissioned the quire herself some time after 1472, when Guillaume Chartier died.17 One of the few women commemorated in the Grand Obituary, she had her coat of arms painted into the otherwise empty space at 190r.

The section commences with her undated obituary, headed by a column miniature, which shows the Christ Child sitting on his mother’s lap and holding a set of scales (Fig. 116). With his other hand Jesus grasps his mother’s breast, reminding the viewer that he has received the greatest gift of all from her body. This extraordinary image emphasizes two things that Lady Margaret deemed essential for her obituary—motherhood and gift-giving. Lady Margaret places a sack full of offerings on one side of the balance, while two men—a bishop and a monk—place sacks on the other. The obituary text explains the story: the bishop and monk represent the chapter of Notre-Dame, and their gift bags represent the spiritual rewards and physical privileges that balance out Lady Margaret’s concessions. She sold “the weight of the wax of Paris” to the chapter. This may refer to actual wax, which the church continually burned as candles (in fact, Chartier left money for a candle to burn in perpetuity at the altar of the Trinity in Notre-Dame), or it may refer to an item weighed on one of the two official scales of Paris. In Paris from the twelfth century onwards, there were two royal scales, with one weighing wax (in poids de la cire), and the other weighing everything else (called poids de la roy).18 Of Lady Margaret’s sale, worth 2175 Tours pounds, the chapter only paid her a portion of the agreed sum; however, Lady Margaret relinquished the remainder of this sum to the chapter. In other words, she sold them a large amount of something, possibly wax, at a steep discount. In exchange, the chapter celebrated Masses for her soul, and those of her father, mother, and daughter. In the image Margaret, in ceremonial garb patterned with the fleur-de-lis, appears with her daughter, who is wearing a tall pointed hennin fashionable in the early 1470s and may be proffering a sack. This highly unusual iconography thematizes the church weighing its gifts, and patrons calculating their rewards.19 She was alive in 1472 to commission the quire and may have outlived the fashion for conical hats.

Patterns of wear in this image differ considerably from those witnessed elsewhere in the manuscript. Here, one or more people have lavished attention on all of the figures. Lady Margaret’s face has been so heavily rubbed that it has been obliterated; all that remains is her body, draped with an armorial robe, and her daughter beside her, who has also been heavily fingerprinted along her face and torso. Those performing the ritual also touched the image of the Virgin, whose blue dress has been rubbed down to the underdrawing in two areas. Some of this involved wet-touching, for the liquefied blue paint has migrated to the opposite folio. Christ’s face, the gifts, and the faces of the two men have also been touched. The bishop’s robes have also been wet-touched, resulting in paint transfer. Someone has even wet-touched Margaret’s coat of arms, so that the red paint has adhered to the facing page. Mourners clearly interacted with her obituary on several occasions.

A few folios later, on 190v, the pattern of wear is completely different (Fig. 117). Guillaume’s obituary commences with a column-wide miniature, made in the same campaign of work as Margaret’s (Fig. 118). The image shows the bishop at a Mass at which an image of the Virgin—either as a sculpture or as an apparition—adorns the altar.

Guillaume kneels in prayer while a choir sings behind him. His illumination has barely been touched, with perhaps only the Christ Child’s face and the hem of the priest at the altar wet-touched (a glob of the blue hem has stuck to the facing folio), but the image of Guillaume himself is utterly unscathed. If an officiating priest touched this image, he limited himself to the portions with which he self-identified. Why, then, was such an elaborate illuminated obituary deemed necessary?

As women in this obituary book form a minority,20 a mechanism for the commission might be that sons ordered obituaries for their fathers and wives for their deceased husbands, but there were fewer sons, daughters, and widowers who commissioned them for their dead wives and mothers. Here, the mechanism seems to have been that Margaret used the occasion of Guillaume’s death to commission a double obituary; however, hers, not his, was the quire’s raison d’être. An explanation for the difference in treatment between Guillaume’s and Margaret’s portraits might be this: the priest or church official who was performing the Mass for the Dead, therefore the one operating the book, was only one of the people doing the touching. The others were the gathered mourners. Margaret died some time after 1482, and the quire with two obituaries may have been added shortly thereafter, at a time when Margaret’s memory was still fresh. Mourners may have avidly touched the book during the annual Masses in the few years after she died; however, there were fewer people who remembered Guillaume in the 1480s, as he had died in 1472. If my hypothesis is correct, then lay mourners, rather than priests, were responsible for much of the image-touching. Again, if this scenario is correct, then mourners at events such as commemorative Masses may have learned to use their bodies in performances involving manuscripts and thereby developed a “performance literacy” that they could have applied in other devotional settings. For example, they could have applied similar gestures to their private prayer books.

Continual use of the Grand Obituary from the 1240s until the early sixteenth century degraded the parchment, with the oldest material the most worn. The added obituaries with portraits may have been designed to play a physical role in commemoration ceremonies. Those who attended Masses in Notre-Dame would have seen how priests interacted with the book, and if my hypothesis is correct, they would have had the opportunity to touch the image of the deceased. Such interactions would have played a role in how additional obituaries were conceived: as loci for touch. It is also likely that the way in which the book was touched changed over time.

Perhaps in the thirteenth century, officiants had touched only words and letters. For example, on fol. 311, which is written on original, thirteenth-century parchment, someone has repeatedly wet-touched the KL (for kalens, meaning calendar) at the top of the page (Fig. 119). Although it is not possible to determine whether this wet-touching took place in the thirteenth, fourteenth, or fifteenth centuries, one possibility is that the marks were in fact made shortly after the manuscript’s genesis, and that this wet-touching gesture was expanded for use on the imaged obituaries. As with the story of the missal told earlier, what had first been a ritual involving the word turned into one involving the image. The commemorated ones wanted to be remembered—and touched—far into the future. If we think about the layers in chronological order, we may be witnessing the beginnings of a ritual, which automatically inscribes itself on the page and develops over the course of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Whereas the mourners for Simon de Bucy (who died in 1304) barely touched the manuscript, the practice gained momentum shortly thereafter, in the next decade. Given the extent of her gifts, Lady Margaret may have had access to this manuscript and decided to resurrect the elaborate ceremonies around it in the late fifteenth century. She saw this as a viable route to self-commemoration.

As this essay has shown, manuscripts participated in ceremonies. Those who handled them used the books to choreograph rituals in which the books themselves played a physical role. They were touched by audience members, including singers and funeral attendees, in such a way that people wanted to register their presence in the book and at the event. The ways in which books participated in the theatrics will be taken up in the next volume.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Part II, Chapter 6 (167-212) from Touching Parchment: How Medieval Users Rubbed, Handled, and Kissed Their Manuscripts, by Kathryn M. Rudy (Open Book Publishers, 04.18.2023), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.