Athens installed a variety of regulations on the Delian League and on individual members.

By Dr. Joshua P. Nudell

Assistant Professor of History

Truman State University

Introduction

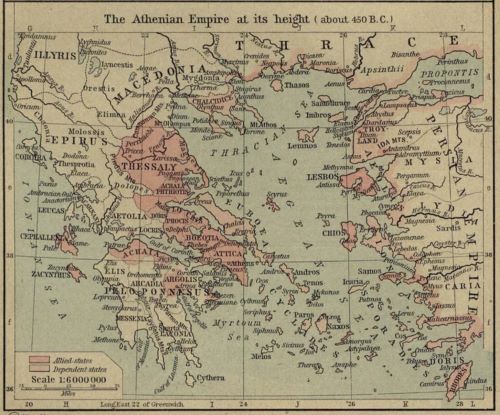

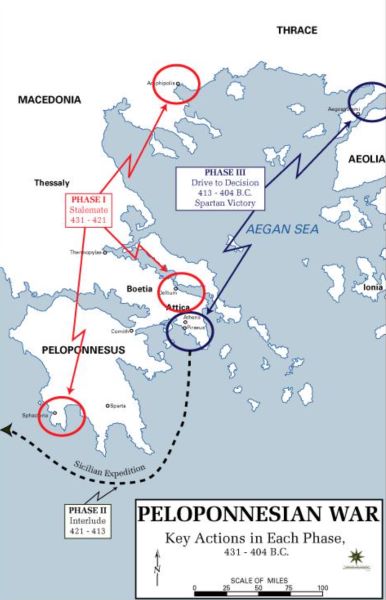

The Delian League drew the Ionian poleis into an Aegean system in the aftermath of the Persian wars, but Athens exerted progressively more control over league institutions and members as open conflict with Persia ground to a halt (Plut. Cim. 19.1–2).1 What had begun ostensibly as a defensive alliance guided by Athenian hegemony became frozen under Athenian imperial control (Thuc. 1.96). The relationship between Ionia and Athens changed in the 450s, in step with the evolution of the Delian League.2 Any history of Ionia in the second half of the fifth century must therefore begin with development of an Athenian empire. The metastasis took place over the course of the years 454–449, which inaugurated a period of conspicuous building projects and the apogee of Athenian power.3 Nevertheless, it was not primarily the renaissance in Athens, but the intersection of imperial systems with local and regional tensions that predated the Delian League, that shaped the direction of Ionia in the fifth century.

The Development of the Athenian Empire

One of the first outward signs of a change in the Delian League’s operating procedure was the transfer of the league treasury. The coffers had been in the sanctuary of Apollo on Delos from the league’s inception, but in 454 they were moved to Athens (Diod. 12.38.2; Plut. Arist. 25.2). Apologists and defenders of the decision pointed to the strategic vulnerability of Delos after the naval disaster in Egypt (Thuc. 1.104, 109–10; Ctesias 32–37), and there were plausible rumors that Artaxerxes ordered a raid on the Aegean in retaliation for Athenian attacks.4 Others, including the Athenian Aristides, cautioned that while the move would be expedient, it was unjust (ὡς οὐ δίκαιον μέν, συμφέρον δὲ τοῦτ ̓ ἐστί, Plut. Arist. 25.2).5 Moreover, the Periclean building program began in earnest after the transfer of the treasury, and Plutarch records twin complaints, from the allies that Athens was misappropriating the funds and from political enemies that Pericles was ornamenting Athens “like a shameless woman” (ὥσπερ ἀλαζόνα γυναῖκα, Plut. Per. 12.1–2).6 It is important to note, however, that Plutarch also describes these claims as slander (διαβάλλειν), which suggests that the accusations were politically motivated hyperbole.7

The symbolism of moving the league treasury to Athens could not have been lost on the allies, but neither was it necessarily a unilateral decision. Ancient tradition, in fact, has the proposal coming from the Samian delegates (Plut. Arist. 25.2). Samos did not pay the phoros, and it is certainly possible that the Athenians used the delegates as a proxy to soften opposition to the move, but the surrounding circumstances provided sufficient cause that one need not posit ulterior motives or cloak-and-dagger political maneuvering. Nor is there anything in the contemporary record to suggest a particular significance to the transfer of the treasury even though it represents a clear, identifiable change to the league structure. The pattern connecting the transfer with other signs of imperial control emerges only in hindsight.

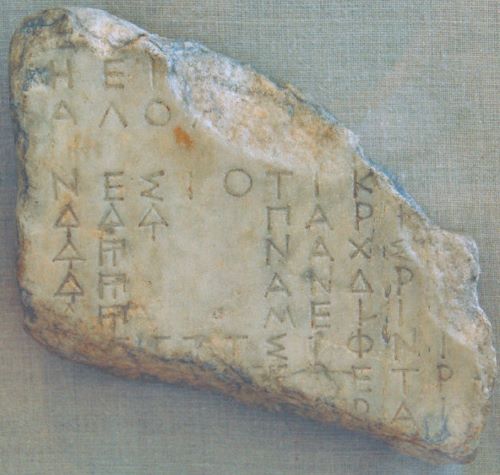

Athens installed a variety of regulations on the league and on individual members in the two subsequent decades, but none of these immediately followed the transfer of the treasury. The only contemporary development that warrants mention was the creation of the so-called Athenian Tribute Lists, marble stelae on the Acropolis that record aparchai (first-fruit offerings) from the annual phoros (tribute) payments made by league members.8 The dedication of aparchai was probably regular part of league ceremony, with the offerings originally dedicated to Apollo. While there is no evidence for comparable inscriptions on Delos, the Delian lists might have been inscribed on wood that has since decayed. On the Athenian Acropolis, the marble tribute lists stood as a monument to Athenian hegemony and undoubtedly could have provided fuel for outrage throughout the Delian League, but this does not explain the conditions in Ionia, where the thesis of local anti-Athenianism is poorly supported in isolation.9

Accustomed to a prominent role in the league, the Ionians are generally thought to have chaffed at the new regulations, with the discontent resulting in a series of revolts between 454 and 449.10 This interpretation, however, rests on shaky foundations. The regulatory decrees that were long seen as a metastasizing of Athenian hegemony have been down-dated away from this period,11 and the remaining evidence for local resistance to Athens emerges from a simple reading of the tribute stelae, which are lacunate and inconsistent. Only Colophon and Clazomenae appear on each of the first three lists, but every Ionian community is recorded making phoros payments on at least one. Scholars nevertheless often isolate Miletus and Erythrae for special scrutiny.12

Milesians from Leros and Teichoussa both appear apart from Miletus proper in 454/3, inscribed among the very last entries on the inaugural list. Similarly, Boutheia on the Mimas peninsula made a payment independent of Erythrae in 453/2 but was grouped with the rest of the Erythraean syntely in the 440s.13 What should be made of these contradictions?

Miletus and Erythrae were both subject to Athenian regulatory decrees, so the orthodox interpretation links these inconsistencies in the 450s to the Athenian impositions. I follow a later chronology for these regulatory decrees, but it is nevertheless appropriate to review them here in brief. Although the two decrees conform to the unique contexts of the poleis in which they appear, they share a common structure. Both were meant to resolve social conflict in the respective citizen bodies, with one group having appealed to Athens for support and the other to Persia. From the Athenian perspective, much as John Hyland has recently argued for Persian policy,14 local stability was a means to an end because it ensured a steady flow of tribute. Losers in Ionian political conflicts appealed to Persia, and the resolving of these conflicts not only protected Athenian interests, but also supported the Athenian claim to leadership because the very existence of the Delian League in this early period was predicated on resisting Persia. Persian satraps regularly offered refuge to political exiles, but only in rare instances did they extend substantial military or financial support.

The problems regarding these decrees stem from the twin pillars that support the traditional chronology for Athenian intervention in Ionia. The first pillar is composed of letterforms. Both inscriptions contain the so-called three-barred sigma that was thought to have fallen out of use in Athenian inscriptions by c.450. The second is formed of lacunae and inconsistencies on the early tribute lists. Both arguments are porous. Scholarly opinion about letterforms has begun to shift, confirming Harold Mattingly’s old thesis that the three-barred sigma remained in use while, simultaneously, the lacunae in the early tribute lists have begun to be filled in.15 Thus, at the same time that the possibility of a later context for both decrees became fashionable, the validity of dating regulations based on the lacunae on the tribute lists was called into question. Most likely, decrees of this sort only became common after the Samian crisis of 440.16

If the regulations were not put in place in the 450s and the resistance to the phoros is not necessarily supported by the tribute lists, then it is necessary to reconsider the Ionian responses to the development of the Athenian empire. As discussed in the previous chapter, the Ionian poleis were unstable even without the Athenian decrees. Earlier inscriptions from the region record imprecations against individuals and families that threatened domestic harmony (e.g., RO 123 = Milet I.6, no. 187),17 but these were local inscriptions addressing local problems. Further, the records of Athenian phoros collection in Ionia changed shape, and while Erythrae and Miletus are unique in that the lists continue link the satellites in connection to the polis, they are not the only instances where communities that had previously paid along with a larger neighbor began to do so on their own.18 By 443/2, for instance, the Ephesian aparche fell from 750 drachmae to 600, while Pygela and Isinda, both former dependents of Ephesus, appear on the Athenian Tribute Lists for the first time, with a combined phoros slightly less than the difference in the Ephesian levels.19 This change inaugurated a period of nearly two centuries during which Ephesus tried to regain control over Pygela and the Pygelans appealed to Miletus and local dynasts in order to remain independent. There were undoubtedly Ionians who approached Persia for support, but probably because they were on the losing side of local power struggles rather than out of anti-Athenianism.

The consequences of the development of the Athenian empire were not immediately evident in Ionia and probably remained hidden though much of the 440s even as resistance to Athenian hegemony cropped up in places like Euboea (Thuc. 1.114). In short, an Athenian alliance still served the purposes the ruling classes in Ionia. This situation would not last. A storm loomed on the horizon: the resumption of a regional conflict between Samos and Miletus that threatened to shatter the precarious balance in Ionia.

Domestic Factionalism and the Specter of Persia

Persian power continued to cast a long shadow over the eastern marches of the developing Athenian empire, and so it is necessary to examine the relationship between Ionia and the neighbors to the east before turning to the domestic conflicts. Despite the tradition that Athenian arms and diplomacy made it impossible for Persian forces to approach the Aegean littoral, satraps remained firmly installed at Sardis and Dascylium and in a position to meddle in Greek affairs. Xerxes never relinquished his claim to Ionia, leading Pierre Briant to argue that Artaxerxes I encouraged the satraps of western Asia Minor to test Athenian weakness and, if possible, to recover these revenues. Thus, scholars frequently interpret domestic friction in Ionia as the result of a pro-Persian fifth column.20 Anecdotal evidence such as Pissouthnes’ intervention on Samos supports this argument, but it is usually based on a structuralist interpretation of Ionian politics most fully articulated by Jack Balcer whereby each community consisted of two groups: the demos, or citizen body that both gravitated toward and was supported by Athens, and a landed aristocracy with an affinity for Persia.

These categories rely on intellectual pirouettes. First, there is an assumption that these categories were unified and determined geographically or ideologically, rather than both riven by their own rivalries and feuds and capable of finding common ground with their “natural” opponents. Here there is a tendency to interpret domestic politics primarily in terms of factionalism exploited by imperial politics. Regional competition over land and in matters of prestige plays a subordinate role in these interpretations even though it continued to play a critical role in the history of Ionia. Second, this paradigm implies that Athens supported democratic governments, while Persia sought to install oligarchies.21 Like the model of American foreign policy during the Cold War that inspired this interpretation, Athenian actions were more complex in practice. Despite the ancient testimony of Diodorus Siculus (12.27), there is no contemporary evidence for a formal Athenian policy of promoting democracy within its fifth-century empire.22 In Ionia, for instance, Chios in the fifth century never had a democratic constitution, and the anonymous “Old Oligarch” explicitly says that Athens threw its lot in with oligarchs at Miletus ([Xen.] Ath. Pol. 3.11). The primary case where a formal conflict between democrats and oligarchs is attested in the ancient evidence is on Samos in 411, when the demos enacted a bloody coup primarily because the leadership proposed to break with Athens (Thuc. 8.14), but years of increased inequality lay behind this democratic revolution.

While the structuralist paradigm of Ionian politics needs to be abandoned, the specter of Persia remains central to understanding the political situation in Ionia. In every instance for which evidence exists, the intervening Persian satrap did so at the behest of a group in, or recently exiled from, an Ionian polis. The significance of Persia therefore lay in its potential to widen preexisting regional and domestic conflicts rather than in creating factions by suborn-ing otherwise loyal citizens. Put another way, if regional conflict and the growth of Athenian power provided the kindling and fuel for a fire in Ionia, Persia could provide a spark.

The War between Samos and Miletus

One of the most brutal episodes in fifth-century Ionia began one night in the spring of 440. Under the cover of darkness, Thucydides says, exiles from Samos crossed back to the island with seven hundred mercenaries and staged an uprising with some popular support. With the backing of the Samian demos and aid from the Persian satrap Pissouthnes, the erstwhile exiles rescued their hostages then held on Lemnos (Thuc. 1.115.4–5; Diod. 12.27.3; Plut. 25.3). Both moves flouted Athenian hegemony; in short order, Athens and Samos were embroiled in a war that lasted for more than nine months.

The seeds of this war were planted more than a year earlier. In 441, war broke out between Samos and Miletus, probably the resumption of a long-standing conflict over farmland near Priene on the Mycale peninsula.23 No details about this conflict survive, but it went poorly for the Milesians, who appealed to Athens for arbitration as hegemon of the Delian League. According to Thucydides, they were joined by private Samian citizens who wanted regime change (1.115.2). There was nothing untoward about the Milesian appeal or the Athenian decision to intervene according to Greek interstate norms, but there was, no doubt, gossip.

Pericles, the first man at Athens, had a notorious relationship with a Milesian woman, Aspasia. Poets referred to the relationship as developing out of love or lust such that Pericles was supposed to have kissed her affectionately when both leaving and arriving home (Plut. Per. 24.5–6), and Aspasia is adorned with slanders frequently given to women in the ancient world, including that she perverted men she was involved with, supplied Pericles with free women as prostitutes, and, eventually, became a new Helen.24 There was a practical explanation for the relationship, though. Aspasia’s sister was married to Alcibiades (the grandfather of the Peloponnesian War’s scandalous general and turncoat of the same name), so becoming involved with Aspasia was a way for Pericles to shore up political alliances.25 In 451/0, Pericles had enacted a citizenship law that granted full rights only to children with two citizen parents, meaning that although he could marry Aspasia, his own actions limited the options of their children.26 The Samians were probably not interested in the nuances of Athenian citizenship laws, but, if Pericles were smitten with this Milesian woman, as people were no doubt saying (e.g., the jokes in Aristoph. Acharn. 525–34), then, surely, the arbitration would be biased against them (Diod. 12.27.1; Plut. Per. 25.1).

Blaming Aspasia is malicious libel. Not only was Plutarch’s source, the early third-century historian Duris of Samos, hardly a neutral commentator, but apparent partiality was just one of the underlying causes of the conflict. There had been a gradual change within the hierarchy of the Delian League that gave Athens ever more power. This evolution had not yet resulted in revolts in Ionia, but tensions were growing. Samos still had a fleet of at least fifty warships in 440 (Plut. Per. 25.3), which gave it both an advantage during its conflict with Miletus and a privileged place within the league. The Samians therefore rejected the Athenian offer to arbitrate the conflict; in so doing, they asserted their independence and challenged Athenian hegemony. There was just one problem: under Greek interstate norms, arbitration did not require the consent of the disputants.27 When the Samians spurned Athens, the conflict ceased to be between Samos and Miletus and became one that would shape the future direction of the Delian League.

In June or July 441, an Athenian fleet sailed to Samos and toppled the government that had rejected the arbitration, installing in its place a faction that had been looking for an opening to take power (Thuc. 1.115.2).28 The leading Samians surrendered hostages, whom the Athenians deposited on Lemnos. Lastly, among the measures to smother the inchoate resistance, the Athenians installed a garrison on the island (Thuc. 1.115.3–4; Diod. 12.27.1–3). As was common for political exiles in ancient Ionia, the deposed Samians fled to Persian territory, where they appealed to the satrap Pissouthnes for aid. There they plotted their return, which they accomplished about eight months later with the seven hundred mercenaries paid for by the satrap.

The Athenian policies designed to pacify Samos, including meddling in local politics and installing a garrison, probably did not have their intended effect. Thucydides notes that the exiles schemed with the most powerful people remaining in the polis and undermined any potential popular opposition to their plans. His terminology is vague, using a markedly oppositional word meaning “to raise an insurrection against” (ἐπανίστημι) for how they behaved toward the demos. It is clear from this word choice that Thucydides regarded the conspirators’ return as a revolution, but there is no evidence for the mechanism they used to enact the coup. The revolutionaries had some popular support and quickly overcame the Athenian garrison, turning them over to the care of Pissouthnes (Thuc. 1.115.5). Moreover, the rebels must have been confident in their position because they immediately prepared an expedition against Miletus, thus resuming the original conflict.

When news of the coup reached Athens, the Athenians immediately dispatched a fleet of sixty ships and the entire board of strategoi to the eastern Aegean.29 Most of the ships in the first wave sailed directly to Samos, but some carried orders to other league states to muster for war, and others sailed south as a precaution against the possible arrival of a fleet from Phoenicia (Thuc. 1.116.1).30 After defeating the Samians returning from Miletus off the island of Tragia, the Athenians disembarked on Samos and lay siege to the city. However, before reinforcements arrived, Pericles took most of the fleet south toward Caria, supposedly because of a rumor that the Phoenician fleet was approaching (Thuc. 1.116.3), but also to make a show of force that offered reassurances to the Milesians and other league members. With the bulk of the Athenian fleet gone, the Samian commander Melissus attacked the Athenian camp, destroying the guard ships and seizing control of the sea around the island for the two weeks until Pericles returned to close the siege and reinforcements from Athens, Chios, and Mytilene swelled the besieging fleet to as many as 239 ships (Diod. 12.28).31

The siege of Samos lasted for more than eight months and, despite a notable silence in Thucydides’ narrative, was bitterly fought. Both sides allegedly branded captured enemy soldiers, the Samians marking Athenians with an owl, and the Athenians using the Samaena, which perhaps caused Aristophanes to joke in Babylonians of 426 that they were a “lettered” people (Plut. Per. 26.3–4). However, as Vincent Azoulay has recently pointed out, the real significance lay in transforming captives into monetary symbols.32 Pericles is also reputed to have brought more siege engines to bear against Samos than had ever been used in Greek warfare (Diod. 12.28.3; Plut. Per. 27.3), and the Athenian supremacy on both land and sea made the surrender of Samos inevitable.

According to Duris of Samos, Pericles ordered the Samian trierarchs and epibatoi (marines) chained to planks in the Milesian agora after they surrendered. There, he says, they were exposed to the elements for ten days before Pericles ordered their heads destroyed with clubs and their bodies disposed of without burial rites (BNJ 76 F 67).33 Plutarch, whose biography of Pericles preserves the story, accuses Duris of embellishing the horrors suffered by the Samians and therefore dismisses its veracity (Plut. Per. 28.1–2), but he is being overly exculpatory to Pericles. Modern scholars tend to attribute this episode to an extension of the siege’s brutality,34 but the Milesian agora was an odd choice of venue if the display was meant as a warning for the Samians or as punishment for the atrocities during the war (Duris calls it a warning to the rest of the allies). More likely, this punishment was the conclusion of the regional conflict between Samos and Miletus. Almost nothing is known about the raid on Miletus, but the trierarchs were likely among its leaders and the epibatoi some of the mercenaries employed in the coup. It is therefore reasonable to assume that Pericles ordered the crucifixion, execution, and disposal of the bodies of these individuals for crimes committed in Miletus.

Samos retained its independence in the aftermath of the war, free of both phoros and garrison, but its challenge to Athenian hegemony was not without consequences. First, the Samian ringleaders were once more forced into exile and hostages were surrendered. The Samians were also forced to tear down their walls and give up their fleet (Thuc. 1.117.3; Diod. 12.28.3; Plut. Per. 28), as well as repay the Athenian war expenses, which totaled more than fourteen hundred talents, in annual installments of fifty talents (ML 55 = IG I3 363).35 Finally, the Samian boule swore a loyalty oath to defend both its own demos and Athens (ML 56 = IG I3 48, l. 22), which set the precedent for the resolution of future conflicts in the Delian League.36

Samos had been one of the staunchest supporters of the league before 454, and it had held pride of place as one of three members outside Athens to retain its fleet when the rest of the league transitioned to providing phoros payments. In the absence of evidence for increasing discontent with Athenian hegemony, it is necessary to ask what changed. Samos had traditionally been one of the dominant poleis in the Aegean, and the tipping point was simply that the Samians called the Athenian bluff concerning its willingness to intervene in disputes between Delian League members. Thucydides’ brief narrative elides that Samos’ challenge posed a real threat that nearly broke Athenian hegemony. The war was not only a demonstration of Athenian will, but also of its ability to exert power over the league members.37 After 439, Samos fell into an anomalous position, no longer a naval power, but also explicitly paying reparations to Athens rather than a phoros to the Delian League. Despite the lingering resentment toward Athens that some Samians must have harbored on account of the financial demands, time heals most wounds, and Samos would become Athens’ staunchest ally again before the end of the Peloponnesian War. Those Samians who refused to surrender took refuge at Anaia in the Samian peraea.

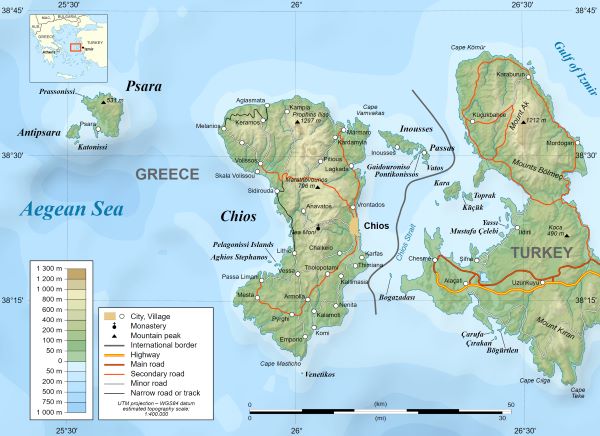

A Horse Not in Need of a Whip: Chios and Athens

Chios had also held a special position within the Delian League after 454. Like Samos, it was wealthy because of its strategic position astride maritime trade routes and was therefore able to maintain a fleet of warships. Once Samos surrendered in 439, Chios alone among the Ionian poleis continued to provide ships to the Delian League. But did the Chians watch the resolution of the war around Samos with trepidation? Looking back from the twenty-first century, it is hard to imagine that they did not recognize the metastasis of Athenian imperialism as it was happening, but money is a powerful drug. Pottery shards from amphorae demonstrate the extent of the Chian commercial reach, including in the Athenian Agora and the Black Sea, and Chian merchants were deeply involved in the slave trade, particularly from the Caucasus.38 Chios profited from Athenian campaigns, not only through its share of the booty, but also by victualing the forces on league expeditions.

Chian ships joined the Athenian blockade, and its merchants likely provided supplies to the besiegers (Diod. 12.27.4). Anecdotes from the siege, such as the Athenian proxenos at Chios, Hermisilaus, hosting a dinner party attended by Sophocles and Ion of Chios (Ion, BNJ 392 T 5b, F 6), suggest that personal, as well as economic, relationships caused the Chians to turn a blind eye to Athens crushing resistance to its hegemony. Certainly, the power of personal relationships should not be dismissed, but Thucydides suggests an alternate explanation. In an encomium of Chios in 411, he says that it was the only community other than Sparta that grew more stable as it grew larger and attributes this situation to its reluctance to act rashly (8.24.4). This combination of internal stability and caution was probably equally important in the lack of resistance to the expansion of Athenian hegemony since Athens never had cause to inter-vene in its domestic affairs the way that it did on Samos.

It is possible that the progression of Athenian imperialism was evident to people on Chios after the war on Samos made clear the limits of allied autonomy, but this does not necessarily mean that they would have launched their own challenge. In fact, there is no evidence of growing concern on Chios. Commerce continued between the two poleis and intellectuals such as the playwright Ion and the mathematician Hippocrates frequented Athens, attending and giving lectures and, in the case of Ion, winning dramatic competitions (Ion, BNJ 392 T 1, 2).39 Chian forces also continued to accompany Athenian military expeditions (e.g., Thuc. 2.56.2, 4.129.2, 5.85, 7.57.3). From an Athenian perspective Chios was the perfect subject, such that in 422 the Athenian comic poet Eupolis quipped that Chios was like a horse that did not require a whip because it obediently provided ships and men whenever needed (Poleis, F. 232).40

Chaffing at the Athenian Bit

Signs of stasis began to appear with increasing regularity throughout Ionia starting in the 430s. The first incident was at Erythrae. An Athenian regulatory decree c.434 installed an Athenian-style democracy with a council approved by the Athenian phrourarchos (garrison commander, RO 121 = IG I3 14, l.13–14).41 Another decree addressed the issue of exiles, specifying a group that had taken refuge with Persia and requiring Erythrae to seek Athenian approval before any new expulsions or restorations (RO 122 = I.Ery. 2, l. 27). These decrees conjure the specter of Persia along with the mention of exiles, so the conflict that Athens intervened in is often interpreted as being between Athenian loyalists and a faction that intended to turn Erythrae over to the Persians. Thus, the standard line goes, the Athenian garrison was intended to “protect Erythrai from medizers,” even while acknowledging that it was part of a broader policy of protecting Athenian imperial interests.42

Before examining the local conditions at Erythrae in more detail, it is necessary to question the usual characterization of conflicts of this type as a direct outgrowth of a cold war between Athens and Persia.43 The inscription erected at Erythrae invites a reading of a conflict stirred up by meddlesome Persians and a handful of malcontents, but there is reason to be skeptical. It was in the Athenian interest to exonerate most of the population, blaming the people who had already gone into exile, and implying that the current impositions were protection against barbarians and tyrants. The display was itself a piece of rhetoric. The exiles had taken refuge with Persia, and it is an easy leap to paint them as patsies working to undermine Greek freedom by inviting in the Persians, which thereby justified the Athenian intervention. And yet, Persia was a common destination for Greek (including Athenian!) political refugees banned from the Delian League, and Persian territory was just a few kilometers from Erythrae. It is therefore natural to have expected the Erythraean exiles to decamp for Persia in 434 without their actions necessarily having been motivated by either gold or Persian sympathies.

What, then, do these decrees indicate about the local political situation in Erythrae? First, the provisions concerning government were designed to circumvent several local problems at once. The Athenian-style democracy would in theory make it more difficult for a few individuals to seize power, while the phrourarchos’ power to vet the incoming council provided Athens a measure of control over prospective legislation. This new arrangement, combined with the provision concerning exiles, also gave the phrourarchos authority to mediate local disputes. Despite the benevolent veneer of the decree, the combination of restrictions and garrison indicates that the crisis at Erythrae went beyond just a group of malignant medizers and extended into the population at large.

Panning back from Erythrae reveals a similar pattern throughout Ionia. In 430, a faction in Colophon called for and received aid from Persia, forcing their rivals to flee to the port of Notium (Thuc. 3.34.1). There, the refugees again split into factions, with the Persian satrap Pissouthnes sending mercenaries to support one side. Once the conflict broke out in Colophon, Pissouthnes took advantage of the schism, but Thucydides gives no indication that he had actively been working to cause the conflict. With their backs to the wall, the other faction appealed to the Athenian admiral Paches, who detained the mercenary commander during a parley and immediately attacked and defeated the Persian force (Thuc. 3.34.2–3). Paches restored the exiled Colophonians and established them in a new settlement at Notium with other refugees from around the Aegean (ML 47 = IG I3 37; Thuc. 3.34.4).44 In 427, there were thus two Colophons, one in Notium and one in the original astu, because this was the most expedient solution for Athens to resolve a deep rift in the Colophonian citizen body.

Another regulatory decree appears on an inscription from Miletus, probably from 426/5 (IG I3 22).45 As at Erythrae, the Athenians installed a garrison and restrictions on the Milesian political and legal systems (ll. 28–51), as well as installing five archons (officers), one for each of the five natural divisions of the Milesian territory.46 Other than the number of archons, which was probably no more significant than a practical consideration in terms of the Milesian civic structure, the most notable difference was that the Milesian officials swore to uphold the decree, rather than swearing an oath of loyalty to Athens. This is a significant change, but one that even more strongly reflects the need to resolve a bitter internal conflict, rather than to quell a nascent revolt.

Domestic conflicts in Ionia did not exist in isolation, and imperial competition over Ionia exacerbated the conflicts because factions could exploit the imperial actors for local ends. These conflicts became deep-seated in time, but they should not be taken to reflect a political preference on the part of the community. Looking at the Athenian regulations in Ionia as an outgrowth of local conflict moreover avoids the trap where every local development is a reaction to specific imperial actions in Athens. The signs of unrest extended even to Chios, but before turning to these, it is necessary examine the only incident where fighting from the Archidamian War spilled across the Aegean into Ionia.

In 427, a Peloponnesian fleet under the command of the Spartan Alcidas crossed the Aegean to support Mytilene, which had revolted from Athenian leadership. According to Thucydides, the Peloponnesians did not sail with enough urgency and arrived in Asia Minor unaware that Mytilene had fallen about a week earlier. The fleet thus put in at Embata in Erythrae to debate a course of action. An Elean named Teutiaplus proposed an attack, anyway, claiming the Athenians could be taken unawares (Thuc. 3.30). Alcidas was unimpressed, and Ionian exiles and Lesbians who had joined the expedition urged him instead to capture a city in Ionia or Cyme just into Aeolis to use as a base to incite revolution throughout the region. The exiles reassured Alcidas that the Ionians would welcome Spartan intervention and that their plan was prudent because they could induce Pissouthnes to support them and it would deprive Athens of a significant part of its revenue (πρόσοδον ταύτην μεγίστην, Thuc. 3.31.1).47

Alcidas was ultimately not persuaded, but the proposal is revealing about the circumstances in Ionia in 427. First, this war council took place at a town in Ionian territory, which is clear indication that the capture of outlying settlements was well within the capacity of the fleet. Second, the proposal was made by unnamed and unprovenanced Ionian exiles. Thucydides does not indicate when they joined Alcidas, but the fact that among them were Lesbians and the ostensible aim of the expedition was to relieve the siege of Mytilene, it is reasonable to assume that they had accompanied it from the Peloponnesus and thus had a voice in the deliberations. Third, the basic structure of the plan, from using an Ionian polis as a Spartan base to appealing to the Persian satrap to envisioning widespread popular support for revolution is identical to the outcome fifteen years later during the Ionian War. While it cannot be ruled out that Thucydides meant this debate to foreshadow the later revolt, it still invites the question whether it is an accurate assessment of Ionian popular opinion.

The exiles were overly optimistic in more than one respect. There is no indication that, when news spread that a Peloponnesian fleet was in the Erythraeid, any other Ionians approached Alcidas. On the contrary, Thucydides says that the Ionians reacted with fear and immediately sent messengers to Paches and the Athenian fleet (3.33.2). It was ultimately continuous intervention on the parts of Tissaphernes and Cyrus the Younger during the Ionian War that pried Ionia away from Athens. The exiles also misjudged Pissouthnes, who received support from Athenian mercenaries when he went into revolt soon after Artaxerxes’ death in 424 (Ctesias, F 52).48

But if Pissouthnes was no Cyrus, neither was Alcidas Lysander. With Mytilene fallen, Alcidas decided to return to the Peloponnese. Thucydides pre-serves a compressed sketch of Alcidas’ voyage, but it began with a tour of Ionia. Setting out from Embata, the Spartan fleet sailed south along the shore to the Teian town of Myonnesus. During the expedition, Alcidas’ fleet had been conducting piratical raids on Chios and other Ionian communities. Mistaking the Peloponnesian vessels for Athenians, the Ionians had come up to the ships and been captured (Thuc. 3.32.3). At Myonnesus, Alcidas ordered most of these prisoners executed. Continuing southward, Alcidas put in at Ephesus, where he received envoys from the Samian exiles at Anaea who rebuked him for executing the prisoners, saying that they were Athenian allies under coercion and that his current actions were turning potential friends into enemies (Thuc. 3.32.2).49 After releasing the remaining prisoners, probably in return for ransoms, Alcidas’ fleet beat a hasty retreat from Ephesus.

So ended the only Spartan expedition to Ionia during the Archidamian War, but local conflict continued. According to Thucydides, one of the factors working in Alcidas’ favor in 427 was that Ionia was unfortified (3.33.2). The lack of defensive walls is clearly explained in some instances, such as on Samos, where they were destroyed as part of the resolution to the war in 440/39. In others, the information is sketchier. It is possible that the Ionian communities were without walls because of because of imperial mandate, either by Persia or Athens.50 Indeed, a fragment from the lost comic poet Telecleides chides the Athenians for giving Pericles power over the walls of their subjects (Plut. Per. 16.2), and other evidence indicates that Athens intervened when local conditions threatened its interests, including at Chios in 427 (Thuc. 4.51). Little is known about this local conflict, but a fragmentary inscription from Athens dated to 425/4 honors Philippos and Ach[illes], two Chians plausibly from the poet Ion’s family who preserved the pisteis between Chios and Athens.51 However, other Ionian poleis may have been unfortified because they were decentralized and walls were expensive to build, rather than by imperial fiat.

Alcidas’ meeting with Ionian emissaries at Ephesus in 427 also poses a riddle. There is no direct evidence for the political leanings of fifth-century Ephesus before 411, but indirect evidence leads to several divergent interpretations. On the one hand, the tribute lists indicate a stable record of phoros payments, and no evidence suggests that Ephesus was subject to special regulations or a garrison. On the other hand, Ephesus stood apart from the Ionian revolt, even slaughtering Chian survivors after the battle of Lade (Hdt. 6.16). There was no such thing as a “purely” Greek culture anywhere in the eastern Aegean, least of all in Ionia, but acculturation was particularly pronounced at Ephesus. These processes are epitomized by the Persianization of the cult of Artemis, where the priest took on the title “Megabyxos” (Xen. Anab. 5.3.6), Persian items appeared among the dedicatory offerings, and friezes show figures in Persian garb participating in the rituals.52 What should be made of this disparate evidence? Was Ephesus a quiescent subject or a hotbed of anti-Athenian medism?

The answer is, of course, both—and neither. Ephesus was a natural port for Sardis and therefore had deep, long-standing ties the Lydian capital.53 Moreover, after Cyrus II annexed Lydia in the mid-sixth century, Ephesus became integrated into the Persian royal road system (Hdt. 5.54; Strabo 1.6).54 The fame of the sanctuary of Artemis, which had prominent Anatolian features despite its Greek name, made it a natural magnet for dedications from prominent Persians. Processes of acculturation and religious propaganda, however visible at Ephesus, are not synonymous with political sympathies. Where local conflicts drove factions in most other Ionian poleis to appeal to Persia for support, there is no indication that the same happened at Ephesus. The significance given to the acculturation of the Ionian poleis emerged from the later historiographical record that created an east-west cultural binary that defined Greeks in opposition to the barbarian Persians.55 Only after years of war and increasing financial demands when all of Ionia was ripe for revolt did Ephesus reject Athenian hegemony.

Ionians and the Peloponnesian War

Excepting only Alcidas’ expedition in 427, Ionia was spared the direct effects of the Archidamian War. Nevertheless, the years of conflict between Athens and Sparta affected the region in two ways.

The first was economic. War likely led to an uptick in piracy in the Aegean, at least with expeditions like that of Alcidas, which, in turn, had an immeasurable, but certainly deleterious effect on Ionian commerce.56 The same can be said about the relationship between Ionian trade and the Greek states in European Greece. The war would have restricted commercial opportunities with, for instance, Corinth, but there is no balance sheet recording the actual change. Further, the effects of the war on Ionian commerce were not constant. Not only did Ionian merchants continue to ply the sealanes, fulfilling both military and civilian demands for goods irrespective of the war, but also the Peloponnesian War was in fact a series of interconnected conflicts punctuated by truces, so the interruption of trade was neither constant nor complete.

Somewhat more detail is known about the evolution of the Athenian imperial structures. Every four years since 454 Athenian officials had conducted a new assessment that revised the levels of phoros due for the next period. During the Archidamian War, however, the new assessments came more frequently and at irregular intervals. The most infamous of these assessments was the ninth (A9), conducted in 425/4. The changes in the ninth assessment have traditionally been attributed to the malice of Cleon, who used it as an opportunity to double or even treble the imperial revenue because the war fund had been depleted (ML 69 = IG I3 71).57

Benjamin Meritt and Allen West, two of the original editors of the Athenian Tribute Lists, believed that the sum of tribute payments on A9 could be reconstructed as either 960[—] or 1460[—] talents based on a lost first digit, which is either five hundred or one thousand.58 (The reconstructed inscription is also missing the final three digits of the total.) The inscription recording this assessment is lacunate, and many of the figures, including all of those from Ionia, are lost, but the surviving amounts regularly reveal a substantial uptick in phoros obligations. The AT L editors took the increased obligations in places such as Thrace as confirmation of the larger sum and inferred exorbitant increases in the assessed phoros in Ionia, some as high as fifty talents.59 They nevertheless conceded that the Athenian income from tribute payments never exceeded about one thousand talents, so either the system was wildly inefficient or, more likely, support for the larger figure is misplaced. The ninth assessment did constitute a substantial overhaul of tribute levels, but, as Lisa Kallet has recently demonstrated,60 this did not mean an across-the-board increase. Moreover, there is no evidence, either in surviving phoros payments in the years after 425 or in the form of new unrest, for particularly onerous obligations in Ionia. This is not to say that this assessment did not increase the Ionian phoros obligations. Most likely, the overall assessment was close to 960 talents, and Ionian obligations remained at or near their historical maximum levels.61

It is tempting to see the assessment of 425 as the cause of the Milesian revolt against Athens described above. The problem with this interpretation is the chronology. The regulatory decree is dated 426/5 based on the archon in whose term it was enacted, while the assessment was in 425/4. The two periods overlap, but face in different directions. Where the assessment took place in 425/4, the regulatory decree in 426/5 records the resolution of a conflict that had been going on before that year. The two decrees therefore took place consecutively and were not connected. With this explanation eliminated, it opens the door again for the regulatory decree to be considered in light of chronic factional conflict that plagued fifth-century Miletus. The Ionians almost certainly availed themselves of the special appeals court created in the decree since, as still holds true when it comes to taxes, there were great financial rewards to crying poverty in the fifth century BCE, but there is no reason to interpret local stasis as anti-Athenianism in the wake of a cruel assessment.

Although the assessment of 425 did not lead to substantial changes in Ionia, two other wartime measures did. The first, the so-called Standards Decree (ML 45 = IG I3 1453), is traditionally dated to the mid-440s as part of the tightening imperial regulations, but recent scholarship has revised this date to either the mid-420s or, more likely, c.415/4.62 While the revisionist argument began on the basis of the character of Athenian leaders, namely to exonerate Pericles and pin the blame on the “bloody-minded” Cleon,63 there is nevertheless good reason to read the decree as wartime financial expediency. The Standards Decree itself is a misnomer in that it was a body of regulatory decrees concerning economic activity and erected on stelae in markets throughout the Delian League.64 These decrees had two primary effects. First, they mandated that all economic activity in Delian League markets had to use Attic weights and measures and, second, they required that allied coins used in tribute payments be reminted into Athenian Owls, the famous silver tetradrachmae. The decrees likewise installed procedures for carrying out the new regulations and penalties for infractions.

The fundamental question is how much of an imposition these policies were on the Athenian allies. The Ionian poleis had produced some of the earliest Greek coinage, but they had an inconsistent record of minting coins in silver, electrum, and perhaps smaller denominations in the fifth century. The comparatively rich evidence from Chios reveals an unexpected pattern.65 Starting in the mid-fifth century, Chian mints abandoned the production of staters in favor of tetradrachmae marked with a Chian amphora, but on their own standard. Then there was a transition in the 430s in the amphorae type produced on Chios that brought the amphora into closer alignment with Attic measures, and the iconographic representation on coins follows suit.66 The pattern, then, is that Chios made a spasmodic and irregular transition toward Attic measures and denominations over the course of the second half of the fifth century, but never completed the process.

The Athenian regulations therefore likely formalized the de facto situation in Ionia where the weights and measures had come into alignment with the Attic standard over the course of the fifth century and Athenian Owls had largely supplanted local issues. Coins of many denominations continued to circulate in the Aegean, and the economic standards had changed already before the enactment of these decrees, but the regulations were nonetheless regarded as ham-handed imperialism. It was in this context that Aristophanes in Birds of 414 lampoons the Standards Decree by having a decree-peddler demand that the citizens of Cloudcuckooland use the same measures, weights, and decrees as the Olophyxians (1040–41). The economic effect of the Standards Decree on Ionia is difficult to measure, particularly if, as I have suggested, it was not as onerous as is frequently assumed, but it nevertheless needs to be interpreted as a factor contributing to Ionian frustration with Athenian hegemony by the time of the Sicilian Expedition in 415.

The second wartime change was the replacement of the phoros with a 5 percent harbor tax in 413 (Thuc. 7.28.4). The change replaced an indirect levy on the communities with direct taxation on merchants, but, more importantly, was designed to raise revenue for the war. In short, the symbolic capital in which the allies acknowledged Athenian hegemony through tribute became less important than the money direct taxation could bring in.67 Arable land and natural resources had probably constituted the largest part of the previous assessment, so the transition to taxation based on commercial activity that affected all harbors in the league, including Chios and Samos, significantly increased the imperial burden on Ionia and was likely a contributing factor in the outbreak of the Ionian War in 411.

The Peloponnesian War also affected Ionia more directly: while Thucydides focuses on the triumphs and tragedies of Athens, Ionians fought. Milesians went on the Athenian expeditions to Corinth and Cythera in 425 (Thuc. 4.42, 4.54); Chians accompanied the invasion of the Argolid in 429 (Thuc. 2.56.2), helped Nicias subdue Mende and Scione in 423 (Thuc. 4.129.2), and aided in the capture of Melos in 416 (Thuc. 5.84.1); and Chians, Samians, and Milesians contributed to the invasion of Sicily in 415 (Thuc. 6.31.2; 7.20.2; 7.57.3).68 Athenian soldiers and sailors made up the bulk of the fighting forces, and Athenian commanders may not have trusted Ionian soldiers since, at least in the battle at Cythera, they played no role in the fighting,69 but their repeated appearance as well as the size of the contingents (two thousand Milesian hoplites at Cythera) indicates a substantial contribution to the Athenian war effort. Moreover, the Ionian casualties, particularly in the expedition to Sicily, likely contributed to growing anti-Athenian sentiment. Too, Athenian honorific decrees testify to the presence of Ionians who collaborated with the Athenian imperial state, such as Apollonophanes of Colophon, who was rewarded for his aid of Athenian troops in 427 (IG I3 65), and Heracleides of Clazomenae, who received honors for his cooperation with an embassy to the king of Persia in perhaps 423 (RO 157 = IG I3 227).70 However, even before the disaster in Sicily, Pisthetairus in Aristophanes’ Birds (414) quips that he likes the custom of always adding Chios to things (Χίοισιν ἥσθην πανταχοῦ προσκειμένοις, 879–80). It is possible that these lines were a polite echo of Eupolis’ commentary about the nature of the alliance, but that is not the way of Attic comedy. More likely, they were a dark joke referring to the scarcity of Athenian allies and therefore to actions that marked Chios as unique.71 Aristophanes was not celebrating Chios’ special relationship but poking at a grim situation. The Athenians in 414 were concerned that the Chians, and by extension the other Ionians, were not so well trained.

The relationship between the Ionian poleis and the Athenian empire in the second half of the fifth century swung between extremes. It was here that the greatest threats to Athenian hegemony emerged, but also where Athens often found collaborators for its imperial project who saw opportunities for profit and power. The Sicilian Expedition marked the end of Athenian hegemony over Ionia, but these were also the last years of the fifth century when Ionia itself was largely untouched by war. What is more, the long-simmering stasis in Ionia only grew more pronounced as the Athenian grip weakened.

Endnotes

- The change is often attributed to the Peace of Callias, which has inspired an extensive bibliography debating its existence and its date, with Klaus Meister, Die Ungeschichtlichkeit des Kallias friedens und deren historische Folgen (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1982), 124–30, tallying a since-superseded list of 162 contributions. The general, albeit not unanimous, consensus is that some sort of treaty did take place. Ernst Badian, “The Peace of Callias,” JHS 107 (1987): 38, declared, “It is time scholars stopped disputing the authenticity of the peace at excessive length and started discussing its cardinal importance both in the history of relations between the King and the Greeks and in the history of Athens.” John Hyland, Persian Interventions: The Achaemenid Empire, Athens, and Sparta, 450–386 BCE (Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), 15–35, has recently argued the cessation of hostilities only makes sense from the Persian point of view if the king presented it as his delegating authority over the Aegean to a client state, which would have required a formal treaty. I am sympathetic to Hyland’s argument and accept a possible diplomatic resolution even though the positive evidence for the treaty stems from fourth-century anachronisms. On the Peace of Callias in the fourth century, see C. L. Murison, “The Peace of Callias: Its Historical Context,” Phoenix 25, no. 1 (1971): 12–31, and Wesley E. Thompson, “The Peace of Callias in the Fourth Century,” Historia 30, no. 2 (1981): 164–77.

- Noel Robertson, “The True Nature of the ‘Delian League’ II,” AJAH 5, no. 2 (1980): 110–33, argues convincingly that the key changes happened quickly and in the 460s. I follow a conventional chronology here because it is after 454 that evidence of the evolution appears in Ionia.

- There is a voluminous bibliography on the development of the Athenian empire; for recent discussion see Vincent Azoulay, Pericles of Athens, trans. Janet Lloyd (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014), 51–66; Lisa Kallet, “Democracy, Empire and Epigraphy in the Twentieth Century,” John Ma, “Empires, Statuses and Realities,” and John Ma, “Afterword: Whither the Athenian Empire?,” all in Interpreting the Athenian Empire, ed. John Ma, Nikolaos Papazarkadas, and Robert Parker (London: Duckworth, 2009), 43–66, 125–48, and 223–30, respectively. Notable among the older bibliography are Harold B. Mattingly, “The Growth of Athenian Imperialism,” in The Athenian Empire Restored (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 87–106 (= Historia 12, no. 3 [1963]: 257–73); Malcolm F. McGregor, The Athenians and Their Empire (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1987), 75–83; and Russell Meiggs, The Athenian Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973), 205–72.

- H. D. Westlake, “Thucydides and the Athenian Disaster in Egypt,” CPh 45, no. 4 (1950): 209–16; W. Kendrick Pritchett, “The Transfer of the Delian Treasury,” Historia 18, no. 1 (1969): 17–21. John P. Barron, “Milesian Politics and Athenian Propaganda, c.460–440 B.C.,” JHS 82 (1962): 5, implausibly argues that revolts in Ionia forced Athens to transfer the treasury.

- Aristides had died in 467, but the statement could have been delivered in the original deliberations about where to establish the treasury, since he is said to have made the first assessment ([Arist.] Ath. Pol. 23.3–5; Plut. Arist. 24).

- The popularity of the Athenian hegemony is disputed. Arguing for unpopularity: T. J. Quinn, “Thucydides and the Unpopularity of the Athenian Empire,” Historia 13, no. 3 (1964): 257–66; Donald W. Bradeen, “The Popularity of the Athenian Empire,” Historia 9, no. 3 (1960): 257–69; for popularity: G. E. M. de Ste. Croix, “The Character of the Athenian Empire,” Historia 3, no. 1 (1954): 1–41; H. K. Pleket, “Thasos and the Popularity of the Athenian Empire,” Historia 12, no. 1 (1963): 70–77. Charles W. Fornara, “IG I2, 39.52–57 and the ‘Popularity’ of the Athenian Empire,” CSCA 10 (1977): 39–55, argues that, before 431, when the alternative to Athens was autonomy, Athenian hegemony was unpopular, but that changed once it was a choice between masters. For most Ionian poleis, complete autonomy was never an alternative.

- Modern opinions on whether the Athenians used league funds to pay for the domestic building program vary widely. Lisa Kallet, “Did Tribute Fund the Parthenon?,” CA 8, no. 2 (1989): 252–66, argues that the passage should not be dismissed, as do A. Andrewes, “The Opposition to Perikles,” JHS 98 (1978): 1–8, and Walter Ameling, “Plutarch, Perikles 12–14,” Historia 34, no. 1 (1985): 47–63, but also that the tribute did not fund the Parthenon, while Loren J. Samons II, “Athenian Finance and the Treasury of Athena,” Historia 42, no. 2 (1993): 129–38, argues that the treasury of Athena became the war chest of the league. Adalberto Giovannini, “Le Parthenon, le tresor d’Athena et le tribut des allies,” Historia 39, no. 2 (1990): 129–48, emphasizes the Parthenon as a Hellenic monument to victory over the barbarians, and, as Azoulay, Pericles, 65–66, points out, the building was a treasury and monument rather than a temple. Jeffrey M. Hurwit, The Acropolis in the Age of Pericles (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004) 94–102, identifies at least one public work, a well-house in Athens, built solely from tribute. Recently, T. Leslie Shear, Trophies of Victory: Public Building in Periklean Athens (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2016), 21–26, connected the transfer of the treasury with the building program, but he also suggests that Plutarch did not understand the economics of Greek temple building. See Kallet, “Did Tribute Fund the Parthenon?,” n. 1 for a list of works that accept as fact that the Parthenon was funded with allied tribute payments.

- The Athenian Tribute Lists (IG I3 259–91) were compiled from fragments found on the Athenian Acropolis and Agora and first published in three volumes edited by Benjamin D. Meritt, H. T. Wade-Gery, and Malcolm F. McGregor. On the offerings, see Catherine M. Keesling, The Votive Statues on the Athenian Acropolis (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 7; Bjørn Paarmann, “Aparchai and Phoroi: A New Commented Edition of the Athenian Tribute Lists and Assessment Decrees” (PhD diss., University of Fribourg, 2007), 40–52; Theodora Suk Fong Jim, Sharing with the Gods: Aparchai and Dekatai in Ancient Greece (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014), 36. The inscriptions for the assessment decrees only began to stand alongside the dedications in 425.

- On opposition to Athenian hegemony beyond Athens and Athenian responses, see Jack Martin Balcer, “Separatism and Anti-separatism in the Athenian Empire (478–433 B.C.),” Historia 23, no. 1 (1974): 21–39; Martin Ostwald, “Athens and Chalkis: A Study in Imperial Control,” JHS 122 (2002): 134–43; Cristophe Pébarthe, “Thasos, l’empire d’Athènes et les emporia de Thrace,” ZPE 126 (1999): 131–54; Pleket, “Thasos,” 70–77; Brian Rutishauser, Athens and the Cyclades: Economic Strategies, 510–314 BC (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 85–91; R. Zelnick-Abramovitz, “Settlers and Dispossessed in the Athenian Empire,” Mnemosyne 4 57, no. 3 (2004): 325–45.

- On this connection, see, for instance, Jack Martin Balcer, Sparda by the Bitter Sea: Imperial Interaction in Western Anatolia (Providence, RI: Brown University Press, 1984), 380–81; Bar-ron, “Milesian Politics and Athenian Propaganda,” 5; Vanessa B. Gorman, Miletos, the Ornament of Ionia (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2001), 235–36; David M. Lewis, “The Athenian Tribute-Quota Lists, 453–450,” ABSA 89 (1994): 294; Meiggs, Athenian Empire, 152–64; James Henry Oliver, “The Athenian Decree concerning Miletus in 450/49 B.C.,” TAPhA 66 (1935): 177–98; Noel Robertson, “Government and Society at Miletus, 525–442 B.C.,” Phoenix 41, no. 4 (1987): 384–90. Charles W. Fornara, “The Date of the ‘Regulations for Miletus,’” AJPh 92, no. 3 (1971): 473–75, argues for a date of 442.

- Down-dating the regulations for Miletus was first proposed by Harold B. Mattingly in three articles, “The Athenian Coinage Decree” (= Historia 10, no. 2 [1961]: 148–88), “‘Epigraphically the Twenties Are Too Late . . .’” (= ABSA 65 [1970]: 129–49], and “The Athenian Decree for Miletos (IG I2, 22+ = AT L II, D 11): A Postscript” (= Historia 30, no. 1 [1981]: 113–17), all in The Athenian Empire Restored (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 35–44, 308–11, and 453–60 and is followed by Paarman, “Aparchai and Phoroi,” 121–40; Nikolaos Papazarkadas, “Epigraphy and the Athenian Empire: Reshuffling the Chronological Cards,” in Interpreting the Athenian Empire, ed. John Ma, Nikolaos Papazarkadas, and Rorbert Parker (London: Duckworth, 2009), 67–77; P. J. Rhodes, “After the Three-Bar ‘Sigma’ Controversy: The History of Athenian Imperialism Reassessed,” CQ 2 58, no. 2 (2008): 503–4; and P. J. Rhodes, “Milesian ‘Stephanephoroi’: Applying Cavaignac Correctly,” ZPE 157 (2006): 116. The provenance of the decree at Erythrae is more problematic. It was found on the Athenian Acropolis by Fauvel in the early nineteenth century, but both the stone and the original transcription are lost. See Russell Meiggs and David M. Lewis, A Selection of Greek Historical Inscriptions (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1969), 91, with bibliography; cf. Georgia E. Malachou, “A Second Facsimile of the Erythrai Decree (IG I3 14),” and Akiko Moroo, “The Erythrai Decrees Reconsidered: IG I3 14, 15 & 16,” both in ΑΘΗΝΑΙΩΝ ΕΠΙΣΚΟΠΟΣ: Studies in Honour of Harold B. Mattingly, ed. Angelos P. Matthaiou and Robert K. Pitt (Athens: Greek Epigraphical Society, 2014), 73–96 and 97–120, respectively.

- Colophon is a third polis subject to Athenian regulations, which probably date to a later period; see below “Chaffing at the Athenian Bit.”

- Meiggs and Lewis, Selection of Greek Historical Inscriptions, 93; Meiggs, Athenian Empire, 112; P. J. Rhodes, “The Delian League to 449 B.C.,” in Cambridge Ancient History 2, vol. 5, ed. David M. Lewis, John Boardman, J. K. Davies, and Martin Ostwald (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 54–59. In an examination of local settlements on the Mimas Peninsula, Ismail Gezgin, “The Localization Problems of Erythrae’s Hinterland,” trans. A. Aykurt, Arkeoloji Dergisi 14, no. 2 (2009): 95–108, argues that there is no archaeological evidence for a settlement named Boutheia. On the cycles of formation of dissolution (apotaxis) of the Erythraean syntely, which he attributes to local elites negotiating the Delian League system to minimize their obligations, see Sean R. Jen-sen, “Tribute and Syntely at Erythrai,” CW 105, no. 4 (2012): 479–96.

- Hyland, Persian Interventions, 28–33.

- On the three-barred sigma debate see Rhodes, “Three-Bar Sigma Controversy,” 503–4; Mattingly, “Epigraphically,” 284–85; Papazarkadas, “Epigraphy and the Athenian Empire,” 77. Reevaluating the dates does not require inscriptions with the three-barred sigma to be down-dated but opens a wider range of possible contexts. For the lacunae, see, e.g., Paarman, “Aparchai and Phoroi,” 125–37.

- There are still strong grounds to date two comparable inscriptions relating to Euboea (IG I339 and SIG 3 64) to the mid-440s; see Ostwald, “Athens and Chalkis,” 134–43.

- As described above, Chapter 2, Miletus had a long history of domestic conflict. Cf. [Plut.] Mor. 298c–d; Hdt. 5.28–30. On the imprecations in this inscription, see Gorman, Miletos, 229–34; Robertson, “Government and Society at Miletus,” 358–59; Barron, “Milesian Politics and Athenian Propaganda,” 1–2.

- Sean R. Jensen, “Rethinking Athenian Imperialism” (PhD diss., Rutgers University, 2010), along with “Tribute and Syntely at Erythrai,” and “Synteleia and Apotaxis on the Athenian Tribute Lists,” in Hegemonic Finances: Funding Athenian Domination in the 5th and 4th Centuries BC, ed. Thomas J. Figueira and Sean R. Jensen (London: Bloomsbury 2019), 55–77, has made a compelling case that “sub-hegemonies” persisted under the Athenian empire.

- Pygela’s aparche was one hundred drachmae and Isinda fourteen and four obols. Creating a larger number of payers in time resulted in higher tribute levels, but, since it did not make a significant financial impact in the short term, this was more likely an administrative response to local discontent.

- Balcer, “Separatism and Anti-separatism,” 27; Pierre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, trans. Peter T. Daniels (Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns, 2002), 580–81; Matt Waters, “Applied Royal Directive: Pissouthnes and Samos,” in The Achaemenid Court, ed. Bruno Jacobs and Robert Rollinger (Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2010), 817–28, but cf. Hyland, Persian Interventions, 15–36, who argues that Athens was a de facto Persian client. Recently Eyal Meyer, “The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks” (PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2017) has shown that the Persian system gave satraps in western Anatolia broad latitude to act so long as it did not directly contravene the king’s interests.

- Matthew Simonton, Classical Greek Oligarchy: A Political History (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017) articulates the significance of “oligarchs” as a political category in classical Greece, but the idea that Persia universally supported them in Ionia is based on a flawed hypothesis of oligarchy’s “natural” opposition to Athens.

- Sarah Bolmarcich, “The Athenian Regulations for Samos (IG I3 48) Again,” Chiron 39 (2009): 59–62, offers a compelling rebuttal to the scholarly orthodoxy about Athenian support for democracies.

- The traditional reading of this conflict is that Samos and Miletus fought over control of Priene, but see Joshua P. Nudell, “The War between Miletus and Samos περὶ Πριήνης (Thuc. 1.115.2; Diod. 12.27.2; and Plut. ‘Per.’ 25.1),” CQ 2 66, no. 2 (2016): 772–74.

- Cratinus Dionysalexandros 115K–A; Aristoph. Ach. 516–39; Duris of Samos, BNJ 76 F 65; Walter Ameling, “Komoedie und Politik zwischen Kratinos und Aristophanes: Das Beispiel Perikles,” QC 3, no. 6 (1981): 411. These slanders are baseless.

- The relationship to the family of Alcibiades is nowhere attested by the written sources but is reconstructed through an onomastic analysis. Plutarch names Aspasia’s father Axiochos (Per. 24.2), which begins to appear in Athens in the second half of the fifth century with Axiochos Alkibiadou (Axiochus, son of Alcibiades), who was either a cousin or uncle of the scandalous politician; see Phillip V. Stanley, “The Family Connection of Alcibiades and Axiochus,” GRBS 27, no. 2 (1986): 173–81. The simplest explanation is that the elder Alcibiades married Aspasia’s sister after his ostracism in c.460; see Peter J. Bicknell, “Axiochos Alkibiadou, Aspasia and Aspasios,” L’antiquité classique 51 (1982): 240–47. Cf. Madeleine M. Henry, Prisoner of History: Aspasia of Miletus and Her Biographical Tradition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 9–10; Rebecca Futo Kennedy, Immigrant Women in Athens: Gender, Ethnicity, and Citizenship in the Classical City (New York: Routledge, 2014), 21; A. J. Podlecki, Perikles and His Circle (New York: Routledge, 1998), 109–10; Kathleen Wider, “Women Philosophers in the Ancient Greek World: Donning the Mantle,” Hypatia 1, no. 1 (1986): 40–42. Alcibiades’ ostracism is attested by a scholion on Aristophanes’ Knights (855), and the name appears on ostraka found in the Athenian agora; see Eugene Vanderpool, “The Ostracism of the Elder Alkibiades,” Hesperia 21, no. 1 (1952): 1–8. A political relationship does not necessarily invalidate the evidence that Pericles genuinely cared for Aspasia.

- Diodorus the Periegete, BNJ 372 F 40, refers to her Pericles’ γυνὴ (wife). On Aspasia’s position in Athens, see Henry, Aspasia, 14; Kennedy, Immigrant Women, 76–78; Cynthia B. Patterson, “Those Athenian Bastards,” CA 9, no. 1 (1990): 41–42; Podlecki, Perikles, 109–10; Raphael Sealey, “On Lawful Concubinage in Athens,” CA 3, no. 1 (1984): 111–33.

- Sheila L. Ager, “Interstate Governance: Arbitration and Peacekeeping,” in A Companion to Ancient Greek Government, ed. Hans Beck (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013), 499.

- Marathesium appears on the ATL for the first time in 442/1 (List 13, col. 1 l. 6), when the brewing conflict might have offered an opportunity for the Marathesioi to break away from Samos; see Jensen, “Rethinking Athenian Imperialism,” 205–7; Meiggs, Athenian Empire, 428.

- There were probably sixteen Athenian strategoi who operated around Samos during the war; see Bolmarcich, “Athenian Regulations for Samos,” 52; Robert Develin, Athenian Officials, 684–321 B.C. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 89–90; Charles W. Fornara and David M. Lewis, “On the Chronology of the Samian War,” JHS 99 (1979): 7–19; Charles W. Fornara, The Athenian Board of Generals from 501 to 404 (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 1971), 48–50; Androtion, BNJ 324 F 38; Strabo 14.1.14; Plut. Per. 24.1; Diod. 12.27.4–5.

- Hyland, Persian Interventions, 23, questions the tradition that this fleet was meant to confront a Persian fleet, calling it a “token” force. The show of force was certainly directed at Athenian tributaries in southwest Anatolia.

- For this calculation, see Bolmarcich, “Athenian Regulations for Samos,” 52.

- Azoulay, Pericles, 58.

- Armand D’Angour, Socrates in Love: The Making of a Philosopher (London: Bloomsbury, 2019), 127, speculates that Melissus would have been among the executed Samians, but there is no evidence either way.

- Graham Shipley, A History of Samos, 800–188 BC (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 117; cf. Philip S. Stadter, A Commentary on Plutarch’s Pericles (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 258–59; Meiggs, Athenian Empire, 192; Frances Pownall, “Duris of Samos (76),” BNJ F 67 commentary. Peter Karavites, “Enduring Problems of the Samian Revolt,” RhM 128, no. 1 (1985): 47–51, argues that the punishment ought to be associated with a second revolt in 412, but see Azoulay, Pericles, 57–61, for Pericles’ violence.

- There are three sums recording cost of the war, which Fornara in Fornara and Lewis, “Chronology of the Samian War,” 12–14, argues corresponds to the three consecutive boards of treasurers responsible for the expedition, while Benjamin D. Meritt, “The Samian Revolt from Athens in 440–439 B.C.,” PAPhS 128, no. 2 (1984): 128–29, holds that the largest refers to the war with Samos, while the other two were for related expeditions. Cf. Alec Blamire, “Athenian Finance, 454–404 B.C.,” Hesperia 70, no. 1 (2001): 101–3; G. Marginesu and A. A. Themos, “Ἀνέλοσαν ἐς τὸν πρὸς Σαμίος πόλεμον: A New Fragment of the Samian War Expenses (IG I3 363 + 454),” in ΑΘΗΝΑΙΩΝ ΕΠΙΣΚΟΠΟΣ: Studies in Honour of Harold B. Mattingly, ed. Angelos P. Matthaiou and Robert K. Pitt (Athens: Greek Epigraphical Society, 2014), 171–84; Shipley, Samos, 117–18, with n. 32. Ancient authors give various sums for the cost: Diodorus Siculus 12.28.3 (200 talents), Isocrates 15.111 (1000 talents), and Cornelius Nepos Timotheus (1,200 talents).

- Meiggs and Lewis, Greek Historical Inscriptions, 153, saw this line as a reciprocity clause sworn by the Athenian representatives, but see Fornara and Lewis, “Chronology of the Samian War,” 17–18. For the most recent reconstruction, see Angelos P. Matthaiou, “The Treaty of Athens with Samos (IG I3 48),” in ΑΘΗΝΑΙΩΝ ΕΠΙΣΚΟΠΟΣ: Studies in Honour of Harold B. Mattingly, ed. Angelos P. Matthaiou and Robert K. Pitt (Athens: Greek Epigraphical Society, 2014), 141–70.

- This is one of the strongest points of evidence in favor of Hyland’s revisionist argument that Persian satraps were under orders not to interfere in the Aegean. Pissouthnes supported the Samian exiles in their domestic conflict but stopped short of giving them aid against Athens.

- Theopompus claims that the Chians were the first Greek people to have purchased enslaved people (BNJ 115 F 122a). On slaves being imported from the Black Sea region, see D. C. Braund and G. R. Tsetzkhladze, “The Export of Slaves from Colchis,” CQ 2 39, no. 1 (1989): 114–25, though David M. Lewis, Greek Slave Systems in Their Eastern Mediterranean Context, c. 800–146 BC (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018) and “Near Eastern Slaves in Classical Attica and the Slave Trade with Persian Territories,” CQ 2 61, no. 1 (2011): 91–113, has recently explored the problems with identifying the Black Sea as the primary vector of this trade. For the spread of Chian pottery finds, see R. M. Cook, “The Distribution of Chiot Pottery,” ABSA 44 (1949): 154–61; Michail J. Treister and Yuri G. Vinogradov, “Archaeology on the Northern Coast of the Black Sea,” AJA 97, no. 3 (1993): 532; Miron I. Zolotarev, “A Hellenistic Ceramic Deposit from the North-eastern Sector of the Chersonesos,” in Chronologies of the Black Sea Area, C. 400–100 BC, ed. Lise Hannestad and Vladimir F. Stolba (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2006), 194–95; Valeria P. Bylkova, “The Chronology of Settlements in the Lower Dnieper Region (400–100 BC),” in Chronologies of the Black Sea Area, c. 400–100 BC, ed. Lise Hannestad and Vladimir F. Stolba (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2006), 218–20; T. C. Sarikakis, “Commercial Relations between Chios and Other Greek Cities in Antiquity,” in Chios: A Conference at the Homereion in Chios, ed. John Boardman and C. E. Vaphopoulou-Richardson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 121–32.

- Ion allegedly procured a jar of wine for every Athenian citizen after his victory (BNJ 392 T 1, 2). On his participation in the tragedy category, see Kenneth J. Dover, “Ion of Chios: His Place in the History of Greek Literature,” in Chios: A Conference at the Homereion in Chios, ed. John. Boardman and C. E. Vaphopoulou-Richardson (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1986), 27–37, and T. B. L. Webster, “Sophocles and Ion of Chios,” Hermes 71, no. 3 (1936): 263–74. Ion also warranted mention in Aristophanes’ Peace (832–37). Hippocrates was a Pythagorean mathematician who allegedly came to Athens to lodge a court case after being swindled out of his cargo; Arist. Eudemian Ethics, 8.2.5.

- αὕτη Χίος, καλὸν καλῶν πόλις<μα>|πέμπει γὰρ ὑμῖν ναῦς μακρὰς ἄνδρας θ ̓ ὅταν δεήσμῃ | καὶ τ ̓ άλλα πειθαρχεῖ καλῶς, ἄπληκτος ὥσπερ ἵππος. Text after John M. Edmonds, Fragments of Attic Comedy, vol. 1 (Leiden: Brill, 1957).

- The dating of this decree is complicated by the absence of a named archon. On a late date, see Moroo, “The Erythrai Decrees Reconsidered,” 97–120; Papazarkadas, “Epigraphy and the Athenian Empire,” 78. For an earlier date c.450, see Meiggs and Lewis, Greek Historical Inscriptions, 453/2; Jensen, Rethinking Athenian Imperialism, 52–54; P. J. Rhodes and Robin Osborne, Greek Historical Inscriptions, 478–404 BC (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), 119–23; Matthew Simonton, “The Local History of Hippias of Erythrai: Politics, Place, Memory, and Monumental-i t y,” Hesperia 87, no. 3 (2018): 497–543. Harold B. Mattingly, “What Are the Right Dating Criteria for Fifth-Century Attic Texts?,” ZPE 126 (1999): 117–22, renounced his late dating.

- Meiggs and Lewis, Greek Historical Inscriptions, 92; cf. Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, 579, 581; Rhodes, “Delian League,” 56–57. Curiously, the medizing faction is typically described as “small.”

- Samuel K. Eddy, “The Cold War between Athens and Persia, ca. 448–412 B.C.,” CPh 68, no. 4 (1973): 241–58, draws the parallel between his modern setting and the ancient world, but the basic relationship is implicitly accepted elsewhere. Hyland, Persian Interventions, 24, rightly critiques Eddy as mistaking “sporadic episodes for an overarching strategy.” I agree with Hyland that the decree does not record active Persian involvement.

- As with the other regulatory decrees for Ionia, the date of this inscription is debated. It is frequently dated as part of a series in the 440s, but see Papazarkadas, “Epigraphy and the Athenian Empire,” for the connection to Thucydides.

- On this inscription, see Mattingly, “Athenian Decree for Miletos,” 453–60; Paarman, “Aparchai and Phoroi,” 121–40; Robertson, “Government and Society at Miletus,” 356–98.

- For the importance of these Milesian districts, see Robertson, “Government and Society at Miletus,” 356–98.

- Examination of the Athenian Tribute Lists does not support their boast. The Ionian-Carian district was one of the poorest.

- On Pissouthnes’ revolt, see Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, 591; D. M. Lewis, Sparta and Persia (Leiden: Brill, 1977), 80–81; Meiggs, Athenian Empire, 349; Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones and James Robson, Ctesias’ History of Persia: Tales of the Orient (Routledge: New York, 2009), 194–95.

- There is a lack of evidence for Ephesus in the second half of the fifth century even though it remained an important waypoint for people making their way to Persia (Thuc. 1.137; 4.50). Simon Hornblower, A Commentary on Thucydides, 3 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991–2008), 2.414–15, attributes its apparent willingness to treat with Alcidas to its being unwalled (Thuc. 3.33.2). A. W. Gomme, A Historical Commentary on Thucydides, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1956), 2.294–95, believes that Alcidas only stayed long enough to take on water.

- It is a commonly held position that the destruction of walls was a stipulation of the Peace of Callias that both Athens and Persia desired; see Badian, “Peace of Callias,” 35; George L. Cawkwell, The Greek Wars: The Failure of Persia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 141; Hornblower, A Commentary on Thucydides, vol. 1, 415; cf. Lewis, Sparta and Persia, 153 and n. 118; H. T. Wade-Gery, Essays in Greek History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1958), 219; Meiggs, Athenian Empire, 149–50; Gomme, Historical Commentary on Thucydides, vol. 1, 295; J. M. Cook, “The Problem of Classical Ionia,” PCPhS 187, no. 7 (1961): 9–11. Gorman, Miletos, 237, rejects this explanation for Miletus.

- See Benjamin D. Meritt, “Attic Inscriptions of the Fifth Century,” Hesperia 14, no. 2 (1945): 115–17; John P. Barron, “Chios in the Athenian Empire,” in Chios: A Conference at the Homereion in Chios, ed. John Boardman and C. E. Vaphopoulou-Richardson (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 1986), 101–2.

- Margaret C. Miller, “Clothes and Identity: The Case of Greeks in Ionia c.400 BC,” in Culture, Identity and Politics in the Ancient Mediterranean World, ed. Paul J. Burton (Canberra: Aus-tralasian Society for Classical Studies, 2013), 25–33. On the cultural identity of Ephesus, see also Appendix 2.

- Other ports in the region, including Cyme and Smyrna, also had close ties to Sardis, but Ephesus may have served as the harbor for Croesus’ fleet (Hdt. 1.27; Diod. 9.25.1–2; Friederike Stock et al., “The Palaeogeographies of Ephesos [Turkey], Its Harbours, and the Artemision: A Geoarchaeological Reconstruction for the Timespan 1500–300 BC,” Zeitschrift für Geomorphologie 98, no. 2 [2014]: 33–66). Croesus lavished dedications on the Artemisium (see Chapter 9), and the sanctuary shows numerous votives of Lydian make; see Michael Kerschner, “Die Lyder und das Artemision von Ephesos,” in Die Archäologie der ephischen Artemis: Gestalt und Ritual eines Heiligtums, ed. Ulrike Muss (Vienna: Phoibos, 2008), 223–33; Sabine Ladstätter, “Ephesus,” in Spear Won Land: Sardis from the King’s Peace to the Peace of Apamea, ed. Andrea M. Berlin and Paul J. Kosmin (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2019), 191–92. For the identification of the Ephesian harbors and the evolution of the coastline, see Stock et al., “Palaeogeographies of Ephesos.”

- David French, “Pre- and Early-Roman Roads of Asia Minor: The Persian Royal Road,” Iran 36 (1998): 20–21; Alan M. Greaves, The Land of Ionia: Society and Economy in the Archaic Period (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 101. On the Persian road system, see Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander, 357–87, and Pierre Briant, “From the Indus to the Mediterranean: The Administrative Organization and Logistics of the Great Roads of the Achaemenid Empire,” in Highways, Byways, and Road Systems in the Pre-modern World, ed. Susan E. Alcock, John Bodel, and Richard J. A. Talbert (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 185–201. When the Athenians returned Artaphernes to Persia in 425/4, they made first for Ephesus (4.50), and Alexander’s route in 334 took him from Sardis to Ephesus; see Chapter 7.

- Lynette G. Mitchell, Panhellenism and the Barbarian in Archaic and Classical Greece (Swansea: Classical Press of Wales, 2007), 10–19; Kostas Vlassopoulos, Unthinking the Greek Polis: Ancient Greek History beyond Eurocentrism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007) 46–53; cf. Appendix 2.