The symbolic transformations of objects of stone and bone with probable ritual and religious significance.

By Dr. Marc Verhoeven

Consultant

RAAP Archaeological Consultancy

Introduction

The concept of ritual failure is mainly based on the idea of collapse and termination of the social and symbolic functions and meanings of ceremonial practices. At first sight, the shift from the general use of evocative and dominant ritual symbolism in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic in the Near East to the employment of rather inconspicuous objects in the subsequent Pottery Neolithic would be an example of such a ritual collapse (Simmons 2007; Verhoeven 2002a1; 2002b).2 However, notwithstanding major changes, in the Pottery Neolithic some of the earlier practices were continued.3 In this case, and I suspect in many others too, it is more appropriate to speak of a transformation instead of a termination of ritual. With this idea in mind, this paper deals with the life cycle of (ritual) objects, particularly with the way in which materials and meanings were transformed. Briefly discussing formation processes, fragmentation and the ‘objectification’ of memory, this contribution focuses on symbolic transformations of objects of stone and bone with probable ritual and religious significance after their ‘first life’ in the Neolithic (c. 8500 and 6000 cal BC) of the Near East (Syria, Turkey and Israel).

Formation Process

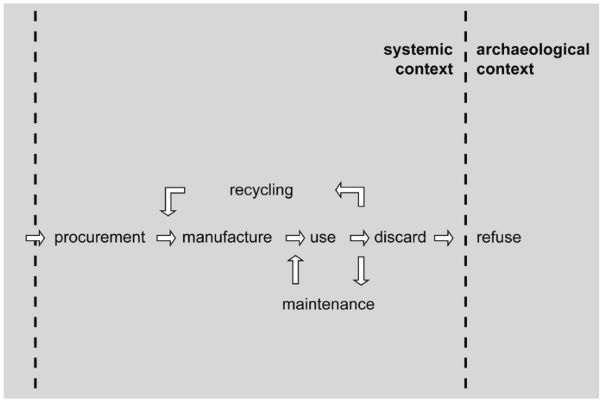

Broken and abandoned objects (discard and refuse) have received much attention in processual archaeology (see e.g. Binford 1983; Goldberg et al. 1993; Rathje and Murphy 1992; Schiffer 1987), mainly in the context of the study of the formation of the archaeological record, i.e. of formation processes. A wealth of valuable data about the life cycles of objects has been generated by these studies. However, an over-enthusiastic systematization, based on a natural science approach, has in many instances led to a too rigid formulation of predictable laws of human and artefactual behaviour. As a consequence, and despite their importance, formation processes are not regularly dealt with anymore. Nevertheless, many archaeologists still think in terms of traditional formation processes theory, as indicated in figure 1. Here we see a flow model of the life cycle of artefacts as formulated in the 1970s by Michael Schiffer (Schiffer 1972). A basic distinction has been made between the so-called systemic and archaeological contexts, i.e. between living and ‘dead’ cultural systems. Within the systemic context objects are procured, manufactured, used, recycled and eventually discarded. In the archaeological context the discarded objects become refuse, which designates the end of their ‘life’.

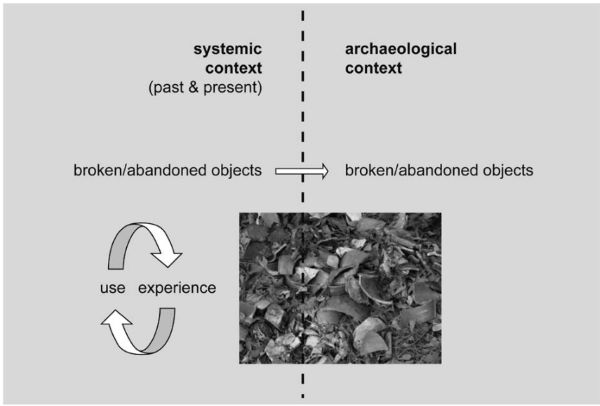

In figure 2 the former scheme has been adapted, focusing on discard and refuse. Three important adjustments have been made. First, in order to avoid the – often negative – modern/Western connotations, the terms discard and refuse have been changed into the more neutral terms broken and abandoned. Second, as will be shown in this paper, such objects often continue to have value in society; therefore abandoned/broken objects have been included in the systemic context. Third, it is indicated that – like all things – such objects are not only functional implements; they have symbolic dimensions as well. In other words, they are not only used; they are also interpreted and experienced, by people both in the past and in the present. In fact, precisely due to their ‘death’ and (deliberate) destruction, abandoned structures and broken artefacts may be transformed into important meaningful and symbolic elements. Moreover, according to animistic beliefs, in many cultures all over the world material objects, whether complete or broken, are regarded as being very much alive and active, especially in the contexts of cosmology, religion and ritual (see e.g. Willerslev 2007). The following sections present some approaches that explicitly pay attention to such transformations as well as to the symbolic and cognitive dimensions of material culture.

Fragmentation and Enchainment

In his book Fragmentation in Archaeology, Chapman (2000) has analysed the meanings of broken objects in prehistoric societies in southeastern Europe. In general, fragmentation or breakage is due to accidents, may occur after deposition or is deliberate, often resulting in structured depositions. It is important to distinguish between broken but complete objects (such as in burials) and broken and incomplete objects. The latter are the subject of Chapman’s study. There are four traditional explanations for the presence of such objects in the archaeological record. First, such items may be the remains of accidental breakage, or are broken as a result of use. Second, objects may have been deliberately buried because they were broken. Especially Garfinkel (1994) has advocated such a view, arguing that broken special and ritual objects in the Neolithic and Chalcolithic of the Near East were too sacred to just dispose of, and were therefore deliberately deposited. Third, objects may have been ritually ‘killed’ and then deposited. The reasons for this practice include fear of pollution, reluctance of reuse, and avoidance of association with objects of the deceased (Grinsell 1960). Fourth, it has been argued by some that objects were broken in order to disperse fertility in the settlement and its surroundings (e.g. Japanese Jomon figurines).

Alternatively, Chapman (2000) proposes that deliberately broken objects were primarily used in so-called enchainment. Enchainment denotes the succeeding chain of personal relations through the exchange of objects (Chapman 2000,5).4 More generally, the notion is based on the belief that in many societies – past and present – people and objects are not strictly separated (as in modern Western society), but are closely related instead. People adopt qualities of objects and vice versa. Thus people are objectified and objects are personified. As long as the object remains inalienable these links continue, even when objects are exchanged. In this respect, anthropologist Weiner (1992) writes about the paradox of ‘keeping-while-giving’ in a study on exchange in Oceanic societies. Meant is the transfer of social and supernatural values, which can benefit exchange partners.

A Matter of Memory

The problem with enchainment is that in many cases (e.g. pottery fragmentation) it is virtually impossible to distinguish between deliberate and non-deliberate fragmentation. The idea, however, does make us aware of the crucial role of material culture in the construction of memory.

Clearly, memory and remembrance, which can be personal or collective, are things of the human mind. It is also clear from recent studies, however, that memories are embedded and supported within a material framework.5 Whether in theoretical terms it is called habitus (Bourdieu 1977), structuration (Giddens 1979), objectification (Miller 1987), dwelling (Ingold 2000) or engagement and materiality (Boivin 2008; DeMarrais et al. 2004; Meskell ed. 2005; Miller ed. 2005), it is clear that there is an active and dialectical relationship between objects and people. Objects shape people as much as people shape objects. By means of interacting with objects, i.e. by social practice and by dwelling among them, humans learn about their specific traditions and culture. Given its immediate presence and protective nature, the house is a principal location for engendering such knowledge (habitus), but in fact we pick up clues about expected behaviour in many other contexts. Ultimately the transmission of information by material culture and our lives are based on experience and remembrance; if we would forget all we encounter and perceive, we would not live very long or well (see e.g. Butler ed. 1989; Casey 1987; Coleman 1992; Connerton 1989; Le Goff 1992; Van Dyke and Alcock eds. 2003 and Williams ed. 2003).

Especially in non-literate prehistoric societies, in which writing as a basic information system was lacking, material culture must have been of the utmost importance for the constitution of persons and society. Monuments, for instance, as a material presence of the past, recall histories and evoke memories. As Alcock notes, monuments are a form of inscribed memorial practice, favouring a conservative transmission of cultural information (Alcock 2002, see also Bradley 1998). Incorporated memorial practice, on the other hand, denotes performative ceremonies, which generate sensory and emotional experiences that result in habitual memory. Especially the use of spectacular or dramatic sensory and emotional media results in the creation and transmission of memories. According to Whitehouse (2004) this is the result of the imagistic mode of ritual, characterized by a low frequency and high arousal. Doctrinal rituals, on the other hand, are marked by a high frequency and low arousal.

The apparently deliberate conflagration of a Pottery Neolithic settlement (c. 5970 cal BC) at Tell Sabi Abyad I in northern Syria as part of an extended funerary and abandonment ritual is a good example of the imagistic mode. The probably most important effect of the ritual was the impression of a very dramatic act in memory, as the heat, colours and smell produced by a large fire provided an intensive stimulation of the senses. This plurality and intensity of experience probably also played a role on a cognitive level, as there was a sense of order, with things that were intentionally brought to an end, but also a sense of disorder, with all the chaos that the fire engendered (Verhoeven 2010, 39). An example of doctrinal ritual practice would be the production and use of small figurines, including the deliberate breakage of these which has been attested at many Neolithic sites (e.g. Verhoeven 2007). The relatively high frequency and low arousal of such practices does not mean that they were insignificant with regard to the transmission of memories. Rather, they were probably triggers for emotions and experiences at the level of the individual and the small group.

Deliberately broken and destroyed objects thus have the capacity to act as ‘vehicles for evoking remembrance’, to paraphrase Jones (2004, 167, see also Jones 2007). It is important to realize that it is not necessarily the object itself, but the action in which the object is involved that is most significant. For example, many ceramic anthropomorphic figurines from the Upper Palaeolithic Pavlovian (29,000-25,000 years ago) of Central Europe were left broken in fireplaces. It has been argued that it was their destruction, i.e. their explosion in the fire, that made them meaningful, instead of their physical presence, and that they were not meant to be viewed (Verpoorte 2001). In a similar vein, with regard to human figurines with apparently removable heads at Neolithic Çatalhöyük (c. 7400-6000 cal BC)6in central Turkey, Meskell (2008, 381) has suggested that the potential of figurines to change identity by means of manipulation of their heads indicates that they were part of processes and not just static forms. Such figurines, and indeed many other objects, probably acted as vehicles for story-telling and remembrance, i.e. history-making (Meskell 2008, 379). As Jones points out, it is important to realize that material culture does not simply ‘freeze’ or ‘fix’ memory to be recalled later. Rather, remembrance is a dialogue between object and person, which can differ according to circumstances and contexts. Finally, I would like to point out that, apart from remembrance, we should pay attention to forgetting. We shall see that, just like the creation and maintenance of memory, activities focused on forgetting and the act of forgetting itself have important cultural implications.

Stones and Bones

Overview

The above discussion has indicated that broken, abandoned and destroyed artefacts can continue to have a role after their initial ‘life’. In fact, in many instances it is precisely due to their ‘death’, breaking, destruction, and so on, that they become meaningful. In the following, this will be exemplified with a number of examples of the changing symbolic and probably ritual and religious significance of objects of stone and of bones.

Stones

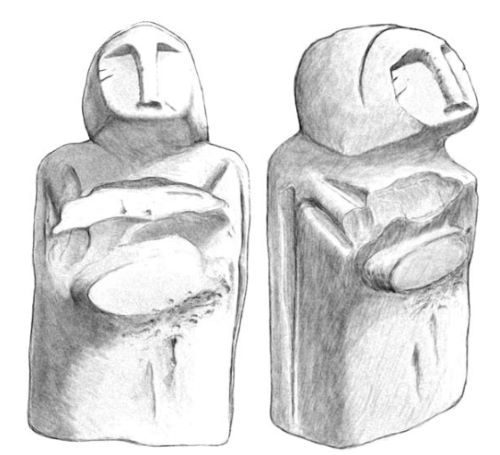

Nevali Çori is a site located in the Taurus foothills in southeastern Turkey and dating from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB, c. 8500-7900 cal BC). Excavations at the site have revealed large stone buildings that were marked by terrazzo floors, interior benches, niches, large anthropomorphic T-shaped pillars and large stone sculpture depicting both humans and animals. Undoubtedly, we here have the remains of ritual buildings (Hauptmann 1993; 1999; 2007; Hauptmann and Özdoğan 2007). There were three such buildings, which were fitted together like a Russian matryoshka doll. The final building 3 was set within the walls of the former building 2, which seems to have been built on building 1 (Hauptmann 1999, figs. 7-9). Interestingly, most of the large stone sculpture was broken and from secondary contexts, as it was found embedded within the walls and buried in the benches of buildings 2 and 3 (see Lichter 2007, catalogue figure nrs. 96-99, pages 289-290). For instance, the famous ‘snake head’ (part of a larger statue), depicting a stylized human head with a snake at the back, was found in a niche in the east wall of building 3. Likewise, two so-called birdmen, representing creatures both human and bird-like, had been incorporated into a wall of building 3 (Figure 3). An approximately one-metre high so-called totem pole, again consisting of a combination of a human and a bird, was found embedded in a bench of building 2.

It is very likely that this broken and secondarily-used stone sculpture stems from earlier phases of the building (Hauptmann 1999, 74-76). The fact that buildings 2 and 3 were built within the confines of predecessors, and not next to it or in another place, strongly suggests that they tapped into the power of former structures. Thus, preceding buildings and their sculpture were probably remembered for the performances and rituals carried out within their confines. Old and often broken sculpture was hidden in plastered walls and in benches of new buildings. As Garfinkel has argued (see above), this might have been done because these objects were too significant to be merely disposed. It is as if the new structures needed to be ‘injected’ with the ritual power of former structures. Some of the sculpture was present but invisible. However, if something is invisible it does not follow that it is forgotten. Rather it means that only people who experienced the original sculpture and those who incorporated it into new buildings knew about it and remembered it. Thus, hiding things and acts of secrecy may have added to the mythic power of objects and buildings. Some of the sculpture apparently needed to be both remembered and forgotten. Perhaps to be forgotten by the public and to be remembered by religious specialists?

As this example shows, memory and forgetting can apply to the same context. In other words: different memorial practices may be at work at any one time. Moreover, the same objects may have invoked different experiences and memories. In this respect, the ritual buildings at Nevali Çori had several ambiguous aspects. First, there was the merging of the old and the new in architecture as well as in sculpture. Then there was some sculpture that was of an ambiguous nature, both human and animal. Finally, some of the sculpture was present but invisible. These contradictory aspects, so typical of ritual practice, and especially their remembered history would have made the buildings special and powerful.

Bones

Apart from objects of stone, human and animal bones7 were used in many different ways for symbolic and, very likely, ritual purposes. First of all, burials of humans and/or animals should be mentioned as occasions for all kinds of ceremonies which were probably primarily related to ancestors. This need not be elaborated upon here.

Another, quite dramatic, example of the ritual use of bones is the wide-spread evidence for the manipulation of human skulls in the Pre-Pottery and occasionally the Pottery Neolithic, as a short-hand often termed the skull cult. The evidence consists of skull removal, skull caching, skull decoration and skull deformation. Perhaps most intriguing are the decorated skulls: by means of e.g. plaster, collagen, paint and cowrie shells as eyes these skulls were probably meant to portray and commemorate the deceased (Bienert 1991; Bonogofsky 2001). Skulls were probably especially honoured because of their vital powers or life force, something which has been documented in a host of ethnographic studies (Verhoeven 2002a). See for example what Smidt (1993, 21) writes on traditional initiation rituals of the Asmat, who live in the coastal swamp forests of southwest New Guinea:

‘It was impossible for boys to become men without taking a head. A man’s vital strength is said to be particularly present in the skull, and the life force of another provided the energy necessary for a boy to make the jump to manhood. Initiation traditionally took place not long after the boys head-hunting raid. At one stage in the group ceremony, each of the boys held a recently severed skull in front of his crotch, and meditated on it. At this stage, the young man was given the head-hunted enemy’s name, and his vital strength assimilated into the group. To ensure the identification between initiate and victim was as close as possible, the boy mediated on the head for two or three days, and was also rubbed with the victim’s blood and his burned hair. These acts were a tribute to the power of the enemy’.

There is actually no evidence for head-hunting in the Neolithic Near East; the example serves to illustrate the special significance which is often attached to human heads. In fact, in this period there was a preoccupation with heads, head removal and circulation (‘headedness’, cf. Meskell 2008, see also Hodder and Meskell 2011) of both humans and animals.

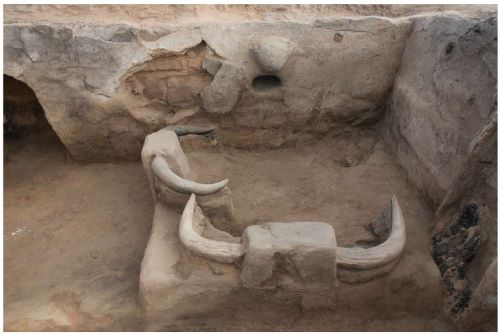

As to the heads of animals, the skulls and/or horns of cattle (bucrania) were often kept in Neolithic buildings. Especially Çatalhöyük is famous for this practice. Most of the cattle horns at the site come from large male wild animals, of which the postcranial remains were characteristic of special feasting deposits. This suggests that cattle horns were kept and displayed in commemoration of the hunting, slaughter and consumption of large and dangerous animals, which would have endowed hunters and feasters with considerable status (Twiss and Russell 2009, 30). Especially bull horns were displayed on platforms and walls: see figure 4. However, it appears that many installed horns were invisibly integrated into the architecture as well. At other Neolithic sites8 cattle horns were also concealed in or under walls, floors and benches (Russell 2009, 20). Thus, both display and concealment played a role. Perhaps display (commemoration) primarily focused on directly affecting people (promotion of status), while hiding (forgetting) and ‘interiorization’ aimed at the transmission of the power of heads and horns to the buildings and the production of secret knowledge of ritual specialists?9 Cattle horns were particularly favoured for symbolic purposes, but horns of other animals were occasionally used as well. At Tell Sabi Abyad, for instance, the horns of wild sheep were included in a series of large oval objects of clay that surrounded two dead bodies on the roof of a building. These ‘monsters’ played a role in the already mentioned ritual conflagration of a settlement, apparently as part of a death and abandonment ritual.

Finally, I would like to mention the various associations between human and animal bones at the PPNB site of Kfar Hahoresh (8500-6750 cal BC) located in northern Israel. The site was probably a mortuary centre, given the fact that in all the areas of excavation quite unusual and spectacular remains of funeral ceremonies have been encountered. In the so-called Bos pit the bones of eight aurochs were deposited after their meat had been consumed, probably as part of a funerary feast. The pit was then covered by a human burial which was plastered over. After a while, the skull was removed. The aurochs skulls were also absent (Goring-Morris and Horwitz 2007). Apparently there was a special concern with establishing relations between humans and animals, as also indicated by a well-preserved human plastered skull, which was found just above a complete but headless gazelle carcass. Another such therianthropic context is represented by a pit in which mostly human long bones had been intentionally arranged in such a manner that when viewed from above they depicted an animal in profile, possibly a wild boar, an aurochs, or a lion (Goring-Morris 2000; 2008). These special associations of human and animal bones may appear very strange at first sight, and the precise meanings elude us, but in a general sense such use of both animal and human bones was one of the best ways to symbolize the links between the related domains of feasting, death, humans and animals. One category, bone, both typified and related these different processes and beings.

Heads and Horns

Notwithstanding the multitude of symbolic expressions and meanings, I believe that there is a general reason for the symbolic, ritual and religious importance of bones. Bones are the material remains of once living beings. This is a very basic observation, but it makes us aware of the peculiar status of bones: they are part of both the living and the dead. The bones of animals, specifically mammals, refer to species that are both close to and different from humans. Bones are the durable and surviving remains of mortal bodies. Moreover, they refer to humans and animals that are no longer there, but with whom people might have had close and personal experiences. In other words, they play a major role in the construction of personal and collective memory.

As we have seen, some skeletal remains were especially favoured, viz. skulls and horns. While the objectives for and meanings of this preferential treatment may have been varied, the widespread use in different regions and at different times strongly suggests some underlying motive. I would argue that it had much to do with the fact that the head is the main means of perceiving the world and of communicating with the environment. It is also the location of the enigmatic brain. In fact, as we have seen, in many cultures the head is taken to be the locus of the vital power or life force of beings. The head is also the most personal aspect of a body and the main locus of identity. It is the first and most immediate element of encounter and recognition, in which especially the eyes play a pivotal role. Skulls, therefore, are powerful and dominant symbols; the face of death with large hollow ‘eyes’ and grinning teeth has inspired people all over the world, from prehistory to the present day. Likewise, animal horns are particularly compelling symbols (e.g. Rice 1998). Well-developed horns signify the power of animals and to capture these horns, e.g. by hunting, is a sign of success and courage in many cultures. Moreover, as opposed to most other mammal bones, horns are very iconical and immediately signify particular animals (e.g. bulls, sheep, goats). For instance, the killing and communal consumption of large bulls in feasts and particularly the prestige of the feast giver(s) is most effectively symbolized by displaying the horns of the animals.

We have seen that the symbolic power of bones was actively used and manipulated in the Neolithic Near East. The transformations from (1) living beings to (2) dead bodies to (3) bones to (4) incorporation in the world of the living meant that bones could be parts of both life and death. Like the re-used stone objects, bones linked the past to the present. They were among the most direct and powerful materializations of history and of remembrance of relatives and other beings that shaped the world.

Conclusion

I hope to have shown that ‘endings’ like death, discard, abandonment, and so on, should in many cases not be perceived as terminations or failures, but as transformations, or beginnings of something new. Notions of enchainment, inscribed memorial practice, incorporated material practice, imagistic modes of ritual and the various examples of the ‘cultural biographies’ (Kopytoff 1986) of – ritual – objects of stone and bone have made it clear that things can have many life cycles and that they in fact can become extra meaningful after their ‘first lives’. Their material presence, their history and the images and memories they evoke are all part of the complex web of past, present and future relations of beings and things. Rituals are among the most important mechanisms for getting a grip on this complexity, as they provide means for explaining, understanding and regulating society and cosmos (e.g. Guthrie 1993). In other words, they accompany the passage of time and the transformation of matter and thought. In a way, through ritual the past never ends.

Appendix

Endnotes

- RAAP Archaeological Consultancy, the Netherlands, marc.verhoeven@yahoo.com.

- Examples of ritual objects in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic are decorated human skulls, statues and large stone pillars decorated with animals, while in the Pottery Neolithic small human and animal figurines made of clay are typical.

- E.g. the use of figurines and the manipulation of (human) skulls.

- According to Chapman (2000, 6), enchainment works as follows: First, two people involved in establishing a social relationship and/or an economic transaction agree on an object appropriate to the interaction and break it in parts, each keeping one or more parts as a token of the relationship. The fragments are then kept until reconstitution of the relationship is required. Finally, parts may be deposited in a structured manner. Pars pro toto, then, each part of a broken objects stands for both the artefact and the persons related in the exchange. In other words, fragments of objects not only refer to their complete form, but also to past makers and owners.

- As denoted by materiality, a term nowadays in vogue for the well-established post-processual notion that material culture is active, see e.g. Hodder 1982.

- Çatalhöyük dates from the Late Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) and Early Pottery Neolithic.

- ‘Bones’ designate all skeletal parts, including skulls and horns.

- E.g. Mureybet, Halula, ‘Abr 3, Dja’de in Syria and Ginnig in Iraq.

- Cattle horns at Çatalhöyük and other sites were found in different contexts and deposits, probably indicating that they played symbolic key roles in a variety of rituals (Twiss and Russell 2009, 28; Hodder, ed. 2011).

Bibliography

- Alcock, S. 2002. Archaeologies of the Greek past: landscape, monuments, and memories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bienert, H.D. 1991. Skull cult in the prehistoric Near East. Journal of Prehistoric Religion 5, 9-13.

- Binford, L.R. 1983. In pursuit of the past: decoding the archaeological record. London: Thames and Hudson.

- Bonogofsky, M. 2001. An osteo-archaeological examination of the ancestor cult during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period in the Levant. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International.

- Bradley, R. 1998. The significance of monuments: on the shaping of human experience in Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe. London: Routlege.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Butler, T. 1989 (ed). Memory: history, culture and the mind. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Casey, E.S. 1987. Remembering: a phenomenological study. Bloomington: Indiana: University Press.

- Chapman, J. 2000. Fragmentation in archaeology: people, places and broken objects in the prehistory of South Eastern Europe. London and New York: Routledge.

- Coleman, J. 1992. Ancient and medieval memories: studies in the reconstruction of the past. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Connerton, P. 1989. How societies remember. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- DeMarrais, E., C. Gosden, C. and Renfrew, C. 2004 (eds.). Rethinking materiality: the engagement of mind with the material world. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research.

- Garfinkel, Y. 1994. Ritual burial of cultic objects: the earliest evidence. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 4/2, 159-188.

- Giddens, A. 1979. Central problems in social theory: action, structure and contradiction in social analysis. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Goldberg, P., Nash, D.T. and Petraglia, M.D. 1993 (eds.). Formation processes in archaeological context. Madison: Prehistory Press.

- Goring-Morris, A.N. 2000. The quick and the dead: the social context of aceramic Neolithic mortuary practices as seen from Kfar Hahoresh, in: Kuijt, I. (ed.). Life in Neolithic farming communities: social organization, identity, and differentiation. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 103-135.

- Goring-Morris, A.N. 2008. Kefar Ha-Horesh, in: Stern, E. (ed.). The new encyclopedia of archaeological excavations in the Holy Land. Vol. 5. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society and Biblical Archaeology Society, 1907-1909.

- Goring-Morris, A.N. and Horwitz, L.K. 2007. Funerals and feasts during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B of the Near East. Antiquity 81, 902-919.

- Grinsell, L.V. 1960. The breaking of objects as a funeral rite. Folklore 71, 475-491.

- Guthrie, S. 1993. Faces in the clouds: a new theory of religion. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hauptmann, H. 1993. Ein Kultgebäude in Nevali Çori, in: Frangipane, M., Hauptmann, H., Liverani, M., Matthiae, P. and Mellink, M. (eds.). Between the rivers and over the mountains. Rome: University of Rome, 37-69.

- Hauptmann, H. 1999. The Urfa region, in: Özdoğan, M. and Başgelen, N. (eds.). Neolithic in Turkey: the cradle of civilization: new discoveries. Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayinlari, 65-86.

- Hauptmann, H. 2007. Nevali Çori, in: Lichter, C. (ed.). Vor 12.000 Jahren in Anatolien: die ältesten Monumente der Menschheit. Karlsruhe: Badisches Landesmuseum, 86-87.

- Hauptmann, H. and Özdoğan, M. 2007. Die Neolitische Revolution in Anatolien, in Lichter, C. (ed.). Vor 12.000 Jahren in Anatolien: Die ältesten Monumente der Menschheit. Karlsruhe: Badisches Landesmuseum, 26-36.

- Hodder, I. 1982. Symbols in action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hodder, I. and Meskell, L. 2011. A “curious and sometimes a trifle macabre artistry”: some aspects of symbolism in Neolithic Turkey. Current Anthropology 52/2, 235-263.

- Hodder, I. 2011 (ed.). Religion in the emergence of civilization: Çatalhöyük as a case study. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ingold, T. 2000. The perception of the environment: essays in livelihood, dwelling and skill. London and New York: Routledge.

- Jones, A. 2004. Matter and memory: colour, remembrance and the Neolithic/Bronze Age transition, in: DeMarrais, E., Gosden, C. and Renfrew, C. (eds.). Rethinking materiality: the engagement of mind with the material world. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, 167-179.

- Jones, A. 2007. Memory and material culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kopytoff, I. 1986. The cultural biography of things: commoditization as process, in: Appadurai, A. (ed.). The social life of things: commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 64-91.

- Le Goff, J. 1992. History and memory. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lichter, C. 2007 (ed.). Vor 12.000 Jahren in Anatolien: die ältesten Monumente der Menschheit. Karlsruhe: Badisches Landesmuseum.

- Meskell, L. 2008. The nature of the beast: curating animals and ancestors at Çatalhöyük. World Archaeology 40/3, 373-389.

- Meskell, L. 2005 (ed.). Archaeologies of materiality. Malden: Blackwell.

- Miller, D. 1987. Material culture and mass consumption. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Miller, D. 2005 (ed.). Materiality. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Rathje, W. and Murphy, C. 1992. Rubbish!: the archaeology of garbage. New York: Harper Collins.

- Rice, M. 1998. The power of the bull. London and New York: Routledge.

- Schiffer, M.B. 1972. Archaeological context and systemic context. American Antiquity 37/2, 156-165.

- Schiffer, M.B. 1987. Formation processes of the archaeological record. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Simmons, A. 2007. The Neolithic Revolution in the Near East: transforming the human landscape. Tucson: The University of Arizona Press.

- Smidt, D. 1993. The Asmat: life, death and the ancestors, in: Smidt, D. (ed.). Asmat art: woodcarvings of southwest New Guinea. Leiden: Periplus Editions.

- Twiss, K.C. and Russell, N. 2009. Taking the bull by the horns: ideology, masculinity, and cattle horns at Çatalhöyük (Turkey). Paléorient 35/2, 19-32.

- Van Dyke, R. and Alcock, S. 2003 (eds.). Archaeologies of memory. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Verhoeven, M. 2002a. Ritual and ideology in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B of the Levant and south-east Anatolia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 12/2, 233-258.

- Verhoeven, M. 2002b. Transformations of society: the changing role of ritual and symbolism in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B and Pottery Neolithic periods in the Levant and south-east Anatolia. Paléorient 28/1, 5-14.

- Verhoeven, M. 2007. Loosing one’s head in the Neolithic: on the interpretation of headless figurines. Levant 39, 175-183.

- Verhoeven, M. 2010. Igniting transformations: on the social impact of fire, with special reference to the Neolithic of the Near East, in: Hansen, S. (ed.). Leben auf dem Tell als soziale Praxis. Beiträge des Internationalen Symposiums in Berlin vom 26.- 27. February 2007. Kolloquien zur Vor- und Frühgeschichte 14, 25-43.

- Verpoorte, A. 2001. Places of art, traces of fire: a contextual approach to anthropomorphic figurines in the Pavlovian (Central Europe, 29-24 kyr BP). Leiden: Archaeological Studies, Leiden University, No. 8.

- Weiner, A. 1992. Inalienable possessions: the paradox of keeping-while-giving. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Whitehouse, H. 2004. Modes of religiosity: a cognitive theory of religious transmission. Walnut Creek: AltaMira press.

- Willerslev, E. 2007. Soul hunters: hunting, animism and personhood among the Siberian Yukaghirs. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Williams, H. 2003 (ed.). Archaeologies of remembrance: death and memory in past societies. New York: Kluwer Academic.

Chapter 1 (23-36) from Ritual Failure: Archaeological Perspectives, edited by Vasiliki G. Koutrafouri and Jeff Sanders (Sidestone Press, 01.03.2018), published by OAPEN under the terms of an Open Access license.