Constantine’s grants to the Church of Rome constitute a reasonable starting point for a history of ecclesiastical landholding.

By Dr. Ian N. Wood

Professor Emeritus of Early Medieval History

University of Leeds

The Church’s acquisition of landed property is sometimes presented as a relatively straightforward development.1 However, religious institutions in the Roman period relied less on land than on gifts of treasure. This posed little problem for most pagan priests, whose position was not onerous and was largely ritualized and honorary, and who, moreover, had their own property to support them. It was more of a problem for a Church, several of whose leading apologists were advocating personal poverty for its priesthood, and which at the same time was undertaking major charitable work as well as carrying out its religious and ritual obligations. A landed Church was a solution to this dilemma, but this meant a change in attitudes towards the financial support of religion. This raises the question of the chronology of the acquisition of land.

A.H.M. Jones, while noting that there is evidence for some churches holding property before the reign of Constantine, stated that ecclesiastical landholding grew rapidly and steadily after the emperor’s conversion. He illustrated this statement with a comment on Constantine’s legalization of bequests to the Church in 321, the emperor’s own donations, the gifts of members of the senatorial aristocracy, exemplified by Melania, as well as the evidence of papyri from Ravenna and from Egypt.2 Although this may seem to be a reasonable body of evidence, it relates to two and a half centuries, and for the West the papyrus evidence for Church endowment, apart from one fragmentary charter of 491,3 almost all dates from the later sixth or seventh century.4 Moreover, for the most part the evidence of the papyri concerns relatively small donations. In other words, Jones claimed that there was a rapid growth of ecclesiastical landholding after the conversion of Constantine, and he illustrated his claim with the gifts supposedly presented by the emperor to the Church of Rome, and by one block of substantial senatorial donations just under a century later, and little more. This can scarcely be said to support the statement “that the property of the churches grew rapidly and steadily after 312,” and we have, to my mind, good reason to think that the statement is misleading. Certainly for the fourth century the evidence is less strong than one might deduce from Jones’s statement. As Kate Cooper has noted, “[o]ur understanding of the property arrangements underlying Christian congregations even in the fourth century is surprisingly weak.”5

Lellia Cracco Ruggini, who was much more sensitive than Jones to the chronology of the Ravenna documents, saw the expansion of Church property in Italy as taking place in the course of the fifth and sixth centuries:

“Above all thanks to the large number of donations, and the tendency of large properties to absorb the smaller ones, ecclesiastical land patrimony had in fact expanded enormously during the fifth and sixth centuries.”6

Writing of Gaul, Émile Lesne placed the expansion of Church property after 500. In a couple of florid sentences, he remarked:

“Born in the Roman period, ecclesiastical property in France reached adulthood in the Merovingian period. The roots that had sunk into the land of the Gauls in the fifth century allowed the growth of the tree that already had a superb crown in the sixth and seventh centuries.”7

It is a view echoed by Jean Gaudemet: “In Gaul the institution of ecclesiastical inheritance did not appear before the end of the fifth century.”8 These views would seem to be rather more accurate than those of Jones.

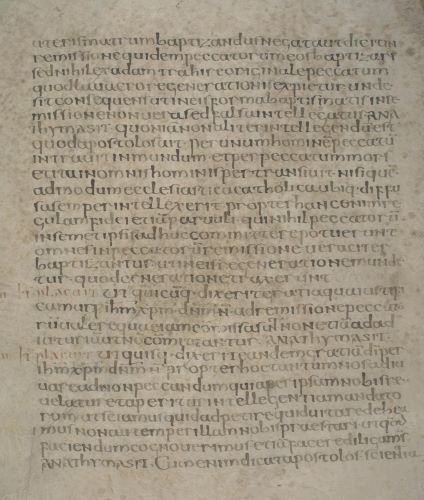

Most scholars would accept that Constantine’s grants to the Church of Rome constitute a reasonable starting point for a history of ecclesiastical landholding, and they may be right to do so, but we need to exercise caution when considering the evidence.9 If we restrict ourselves to the Constantinian donations to the Lateran, St. Peter’s, St. Paul’s, Santa Croce, Sta. Agnese, San Lorenzo, and SS. Marcellino e Pietro, the Liber Pontificalis lists over 69 properties that it claims were given by Constantine to Roman churches in the pontificate of Silvester, and a further four in that of Mark, Silvester’s successor as bishop of Rome.10 Together they provided a revenue of 27,269 solidi, allocated to specific foundations.11 In addition, there are the problematic tituli of Equitius and Silvester, two adjacent foundations, whose endowment as described in the Liber Pontificalis is not entirely cle ar.12 The first was endowed with 5 farms, 2 houses, and a garden, with a revenue of 428 solidi and 1 tremissis, and the second with 9 farms and 1 property, yielding 476 solidi and 1 tremissis.13 Outside the city itself, SS. Pietro, Paolo e Giovanni in Ostia was given an island and 4 properties, with a revenue of 463 solidi,14 while a church in Monte Albano received 11 properties worth 1,400 solidi,15 one in Capua 6 properties worth 710 solidi,16 and finally a church in Naples 6 properties worth 673 solidi.17 The estates varied widely in value: the highest providing a yield of 2,300 solidi, the lowest 10. The list has, of course, been carefully examined, not least by Federico Marazzi.18 Charles Pietri essentially accepted the authenticity of the evidence of the Liber Pontificalis,19 and Paolo Liverani has argued compellingly that the information (especially that dealing with gifts of treasure) was drawn from archival records.20 Raymond Davis suggested that the evidence was gathered together in the time of Constantius II, noting that some of the original information may have referred to the younger emperor, whose name even occurs in some manuscripts alongside that of his father.21 Federico Montinaro, however, has pointed out that the system of accounting used in the donation lists of the Liber Pontificalis is not appropriate for the days of Constantine, and has also noted that at least one property donated to the Lateran baptistery is likely to have been given after the Justinianic reconquest of North Africa. In addition, by comparing the lists in the Liber Pontificalis itself and those in the Felician and Cononian epitomes of the text, he has concluded that the donation lists were modified up until the end of the sixth century.22 Richard Westall has also noted anachronisms in the list of donations to St. Peter’s, and has concluded that they contain material from the 350s.23 According to both Marco Maiuro24 and Paolo Tedesco,25 the vocabulary of the lists suggests that some of them cannot be earlier than the 380s.

With these doubts over the veracity of the lists in mind, it is worth revisiting the “Constantinian” gifts. The scale of the land donations is substantial, but not massive — although I have only listed the landed property, not the gifts of gold and silver (which are genuinely breathtaking).26 It is not, therefore, immediately suspect in terms of its size. As a point of comparison, one might note Olympiodorus’s statement that the annual income of a Roman aristocratic family might amount to 3,000 pounds of gold — equivalent to around 375,000 solidi:27 in other words, well over ten times the value of the estates supposedly granted to all the Roman churches by Constantine. David Hunt noted that the supposed Constantinian donations listed in the Liber Pontificalis were the equivalent of c. 400 pounds of gold, which was only a quarter of Melania’s annual income.28 And he compared the situation in Antioch, where the wealth of the Church “matched one of the city’s wealthier — but not the wealthiest — residents” in the days of John Chrysostom, at the end of the century.29

But while the supposed Constantinian donations may not be stratospherically large, they do mark a departure in terms of the funding of religion, given what we have seen of the endowment of Roman temples, although it looks less exceptional if one turns to the Pharaonic or Hellenistic evidence.30 Constantine was perhaps endowing churches much as a pagan emperor might endow any individual temple. If so, that would raise the question of the type of donation that was involved, since it would seem from the later reversion of temple land to the res privata that emperors had retained an interest in estates on which they had allowed the erection of religious monuments.31 Because we do not have the texts of the deeds of donation, we do not know exactly what was conceded, but Montinaro has noted that the evidence that we have for imperial donations to churches in the sixth and seventh centuries suggests that emperors tended to grant income from estates rather than the estates themselves.32 And it is the annual rental value of estates that is listed in the Liber Pontificalis. The sixth-century compiler (or compilers) of the Constantinian section of the papal biographies33 was (or were) not interested in any legal niceties. By then there was a growing canonical tradition that ecclesiastical property was inalienable without the general consent of the clergy.34 There were, however, those who thought that the Church received its land from the ruler. Avitus of Vienne remarked to Gundobad: “Whatever my small Church has, nay all of our Churches, is yours in its substance, since up to now you have either guarded it or given it.”35 Justinian was of the view that Church land ultimately came from the emperor: “all the wealth and subsistence of the most holy churches is forever bestowed on them by acts of sovereign munificence.”36 This was an idea that would receive more attention in the ninth century.37

We should not only note the novelty of Constantine’s supposed donations. We should also remember that one of the authors of the Liber Pontificalis peddled a complete falsehood in stating that Silvester baptized Constantine, an assertion made in the opening paragraph of the Life of the pope,38 and thus clearly intended to influence one’s interpretation of the imperial gifts. Whether the confusion was deliberate or not, the author subsequently states that Eusebius, the homoean bishop of Nicomedia, rebaptized Constantius, and places the information in its account of the pontificate of Felix II39 — it was, of course, Eusebius, and not Silvester, who baptized Constantine (not Constantius). Moreover, although sickness led to Constantine being baptized in Nicomedia, his intention had not been to return to Rome for the ceremony, but rather to go to the river Jordan, in imitation of Christ.40 Bearing in mind the false statement about the emperor’s baptism, we may want to question whether the very considerable donations to the Lateran Baptistery, which are implicitly linked with the baptism, were actually Constantinian. Its 21 estates, with an annual yield of 10,736 solidi, dwarfs the property of every other church, including the Lateran itself, at 7 estates, worth 4,390 solidi, and St. Peter’s at 16 estates, worth 3,708 solidi and 1 tremissis. Constantine was surely responsible for the building of the Lateran basilica, but so lavish an endowment for the baptistery in his day seems questionable.41 And, indeed, as we have noted, Montinaro has argued that one of the donations was probably made after Justinian’s reconquest of Africa.42

By the late sixth century, the Church of Rome obviously did lay claim to all the properties listed as gifts of Constantine. One of the authors of the Liber Pontificalis is honest enough to state that an estate supposedly acquired by Innocent I was under dispute,43 which implies that other estates were not in question. But it would seem that some gifts ascribed to Constantine came from later emperors,44 some from emperors who were subsequently regarded as Arian. Constantius II is particularly likely to have been involved in the initial endowment of San Paolo fuori le Mura, and indeed he is associated with the foundation in some manuscripts of the Liber Pontificalis.45 In addition, Richard Westall has provided a conclusive case for seeing Constantius as being involved in the construction of St. Peter’s, the building of which he has dated firmly to 357–359.46 And he has noted that the landed endowment listed in the Liber Pontificalis, all of which was to be found in the East, dates to that period. Ammianus commented on Constantius’s erection of an obelisk in the Circus Maximus47 — but the emperor also made a significant contribution to the Christian skyline.

With this in mind, it is perhaps worth asking whether Constantius rather than Constantine was responsible for the building, or at least the main endowment of the Lateran baptistery. As noted above, the Liber Pontificalis places its account of the rebaptism of Constantius by Eusebius of Nicomedia under the pontificate of Felix II. This we can certainly reject. Felix was pope between 355 and 358 (although he lived on until 365),48 while Eusebius died in 341.49 Moreover, in all probability Constantius was baptized in Antioch, shortly before his death in 361, by bishop Euzoius.50 Even so, it is worth asking why the Liber Pontificalis placed a reference to the baptism of Constantius during the pontificate of Felix.

The Liber Pontificalis claims that when pope Liberius was driven out of Rome by Constantius in 355, the exiled pope appointed Felix in his place. Subsequently, Liberius came to terms with the emperor, and was reinstated, initially holding the bishopric of Rome jointly with Felix, before the latter was forced into retirement, and subsequently executed on the emperor’s orders.51 There is a rather different take on events in the account provided by Athanasius of Alexandria, in his Historia Arianorum, where we find that Felix was an imperial appointee and was installed in the Lateran by Constantius.52 Athanasius provides no mention of the fate of Felix, who is simply portrayed as a heretic — and surely if he had been executed Athanasius would have used the fact as further illustration of the emperor’s wickedness. Almost as damning of the account in the Liber Pontificalis is the first document in the collection of papal documents known as the Collectio Avellana, where Felix is portrayed as a perjurer who accepted papal office despite having sworn that there should be no pope other than Liberius. When Constantius visited Rome in 357, two years after the consecration of Felix as pope, the emperor was induced to allow Liberius back to the city, and a year later than that Felix was driven out by the senate and people of Rome.53 In the De viris illustribus Jerome provides the additional information that Felix was appointed by Constantius at the instigation of the leading Arian apologist Acacius of Caesarea.54 In other words, despite the Liber Pontificalis, Felix would seem to have been Constantius’s man, and Socrates is explicit that the emperor was unwilling to see him removed from office.55 Moreover, although the ecclesiastical historians of the later fourth and fifth centuries largely accepted him as being orthodox, he was consistently regarded as having consorted with the Arians.56

The connections between Felix and Constantius surely provide the context for the emperor’s building work at St. Peter’s, and his endowment of the basilica. And one may wonder whether this was also the context for the foundation and endowment of the Lateran baptistery, which was perhaps intended to be the site of the emperor’s own baptism. The silence of the Liber Pontificalis would simply be part of the abolitio memoriae of Constantius, noted by Westall in his discussion of the building of St. Peter’s.57

The sheer oddity of the account of Constantine’s gifts to be found in the Liber Pontificalis becomes yet more apparent when one considers how little attention is paid to the donation of land (as opposed to liturgical vessels and other gifts of treasure) elsewhere in the text. We hear of Felix II buying an estate,58 and of Damasus (366–384) giving 3 properties, which provided a revenue of 405 solidi and 1 tremissis.59 We learn that pope Innocent I (401/2–417) established the titulus Vestinae, dedicated to SS. Gervasius and Protasius, which had an endowment of units of property, including 2 baths, a bakery, and 3 unciae, that provided an income of 1,033 solidi, 1 tremissis, and 3 siliquae. It is unclear from the text how much of this was provided by the senatorial lady Vestina, whose will certainly instructed that the church of SS. Gervasius and Protasius (now dedicated to San Vitale) was to be built from the proceeds of the sale of her jewelry.60 Xystus (432–440) gave 5 properties, including 2 houses, which yielded 773 solidi and 3 siliquae.61 And that is all that we hear of land grants in the recension of the Liber Pontificalis that extends to 715. There is not even a mention of the funding of the great second basilica of San Paolo fuori le Mura, which we know from a mosaic inscription on the chancel arch was consecrated by pope Siricius in 390, following the rebuilding of the church initiated by Valentinian II, Theodosius, and Arcadius62 — which makes one wonder whether some of the 7 estates yielding 4,070 solidi supposedly donated by Constantine to the first church on the site came from these later emperors. In the light of excavation, the original “Constantinian” memoria has been “described as a simple hall rather than a three-aisled church.”63 This near-absence in the papal biographies of comments on land acquisition comes despite the growing evergetical activities of the popes, which have been stressed by Bronwen Neil in her examination of the fifth-century section of the papal biographies,64 and which required considerable funds. It would appear that the donations of property ascribed to Constantine in the Liber Pontificalis are more concerned with portraying the Church of Rome as being a creation of the first Christian emperor than they are with providing an accurate statement of who actually transferred the estates to the Church. The Liber Pontificalis surely drew on genuine archival records: the Life of pope Julius states that “bonds, deeds, donations, exchanges, transfers, wills, declarations or manumissions” should be drawn up under the supervision of the primicerius notariorum.65 Moreover, the inventories of gold and silver objects can be compared with similar lists on pagan inscriptions, recording donations to temples such as that of Isis at Nemi.66 But this is no guarantee that the gifts are associated with their true donor: some of the gifts of treasure associated with Constantine, like those of land, must belong to the post-Constantinian period, simply because the churches to which they were given had not been built before 337.

Of course, the estates listed in the Liber Pontificalis were not the sum total of properties acquired by the popes. For the fourth and fifth centuries, there are a handful of cases which we can compare with the foundation of Vestina’s SS. Gervasius and Protasius.67 The Liber Pontificalis does mention the foundation of a church of St. Stephen by Demetrias in the pontificate of Leo I (440–461), and the pope’s own construction of the basilica of St. Cornelius.68 In addition, there is the evidence of inscriptions, for example those that allude to a church of SS. John and Paul founded by Pammachius,69 and to the endowment of the church of Sant’Andrea in Catabarbara by the Goth Valila in the days of pope Simplicius (468–483).70 But as Julia Hillner has remarked, “none of these rare texts speaks of any measures of endowment of the new foundations taken by the founder or indeed of any further conditions how to use the property endowed.”71 For better evidence of the endowment of the Church of Rome we have to wait until the sixth century, and the correspondence of popes Pelagius I (556–561) and Gregory I (590–604), which has been meticulously studied by Marazzi, especially for the region of Lazio.72 Clearly the acquisition of landed property was not something that generally interested the authors of the Liber Pontificalis, despite their desire to attribute as much of the endowment of the Roman Church as possible to Constantine.

Although we may be sure that some of the gifts supposedly donated to the Church of Rome were given by his successors, there is nothing to suggest that Constantine established a vogue for ecclesiastical donations. Just as there is no continuous tale of endowment to be found in the Liber Pontificalis, so too there is little to be found in other sources. Jones’s point of departure for the history of the landed endowment of the Church is less clear-cut than might have been expected. We do, however, start to hear of sizeable property donations to non-Roman Churches in the late fourth and fifth centuries. It has been inferred from the De obitu Satyri that Ambrose’s brother left substantial estates to the Church, although the text is not explicit about what was given.73 But Paulinus, in the Life of Ambrose, does tell us that the bishop himself gave his property to the Church of Milan, while reserving the usufruct for his sister.74

At the end of the fourth and beginning of the fifth centuries we have a major, and well-known, block of evidence relating to the pious donations of two generations of aristocrats. We hear of Paulinus of Nola and Sulpicius Severus disposing of their wealth,75 and also of the aristocratic women, Melania the Elder, Paula, and Melania the Younger.76 What is striking about the three women in particular is their preference for following the words of the New Testament to the letter, and for giving treasure (realized by the sale of estates) rather than landed property to the Church. This circle of ascetics provided considerable gifts for the Church, but it would not seem that they played a major part in providing it with land. Although Vestina seems to have left property that was used to endow the titulus of SS. Gervasius and Protasius, following instructions in her will, the church itself was built out of the funds raised from the sale of her jewelry after her death.77 Despite the development of strategies to encourage the donation of estates, not least involving the cult of the saints in the fifth century,78 the major period of Church endowment involving numerous very sizeable gifts would seem, rather, to have begun, as Cracco Ruggini and Lesne argued, in the fifth century, continuing into the sixth and seventh.79 This is also in keeping with Hunt’s cautious comparison of the wealth of the late-fourth- and early-fifth-century Church with that of the senatorial aristocracy.80 Moreover, just as the wealth of the Church increased, so too that of the aristocracy declined, not least because of the political crises of the fifth and, in Italy especially, the sixth century.81

The majority of the evidence we have for the accumulation of land by the Church in the late fourth and early fifth centuries points to small-scale gifts by relatively ordinary people. Montinaro, while saying little about the size of donations, has insisted that “private charity was the essential source of ecclesiastical wealth up to the sixth century.”82 Rita Lizzi Testa has commented on Chromatius of Aquileia’s appreciation of “il cumulo di modeste donazione,”83 and Peter Brown has noted that the wealth of the Church was made up of “innumerable private benefactions.”84 Many of these, of course, were gifts of coin or treasure, such as we see recorded on the floors of the churches of northern Italy. Thus we find that Maximian and Leonianus financed 100 feet of the mosaic floor of San Pietro in Brescia.85 There are further examples from Aquileia, where Januarius financed 880 feet, and Grado, where Paulinus and Marcellina funded a colossal 1,500 feet of mosaic floor.86 Additional examples are known from Isonzo and Fondo Tullio alla Beligna.87 Brown has also noted the comparable evidence from the Holy Land.88 Discussing the evidence from the patriarchates of Jerusalem and Antioch, Rudolf Haensch has pointed out that some donors are named, but that others are simply members of a pool of contributors: οἱ καρποφορήσαντες.89 Although some of the western inscriptions do point to sizeable donations, most notably the 1,500 feet of mosaic funded by Paulinus and Marcellina, many of the donors were clearly mediocres, Brown’s “middling sort.” While Chromatius of Aquileia welcomed sizeable donations, as Lizzi Testa noted, he also appreciated more modest gifts.90 Others have also stressed the importance of small donations.91

For grants of land by mediocres we can turn to two remarkable sermons (355 and 356) preached by Augustine on either side of the feast of Epiphany in 426, when he directly addressed the question of the property of his clergy.92 These sermons would have a significant afterlife, circulating as a freestanding work of Augustine under the titles De vita et moribus clericorum suorum and (less appropriately) De gradibus ecclesiasticis. Following the model laid out in the description of the Jerusalem community in Acts, Augustine was insistent that the clergy attached to his episcopal community at Hippo should not have any personal possessions. He had, however, discovered that one member of the community, Januarius, had held onto property which ought to have been passed on to his children (though, just to complicate matters, the children themselves had entered the Church).93 This troubled the bishop so much that he asked all his clergy about their possessions, and set out his findings in a blow-by-blow account. It is a case that has attracted the attention of several scholars.94

In addition to Januarius, one other member of the Hippo community, Leporius, has attracted the attention of Peter Brown.95 The two men fully deserve the attention that has been paid to them, but it is worth considering the other clergy described by Augustine.96 There is Valerius, Augustine’s predecessor, who had donated a plot (hortus) on which Augustine established his own monastery.97 The deacon Valens still held some small fields (agellos) in common with his brother, and could not dispose of them until the two had come to an arrangement.98 His brother, we are told, was a deacon of the Church of Milevis, and was keen to divide up the property, as well as to manumit the slaves they possessed and to provide the Church with an alimentum. Augustine’s own nephew Patricius owned some small fields, agelluli, which he had not been able to dispose of while his mother was alive, since she needed the usufruct.99 The deacon Faustinus, an ex-soldier, had a little property, exiguum, which he had divided with his brothers, giving his portion to the Church.100 Another deacon, Severus, had bought a house (unam domum) with money given by a religious layman, to provide accommodation for his mother and sister, but the property itself he had placed under Augustine’s control. He also had some small fields, agellos, in his native place, which he intended to give to the Church.101 An unnamed deacon had only a few servuli, who he was about to emancipate.102 The deacon Heraclius is more complicated. He had endowed a chapel of the martyr Stephen. In addition, he had bought a possessio that was still under his control, and he had purchased a plot (spatia) on which he had built a house (domum) that his mother might live in. He also had some slaves (servuli) whom he would soon emancipate.103 But as Augustine insists, “No one says that he is rich.” The priests, however, had nothing, although Barnabas had received a villa from Eleusinus, which he had turned into a monastery. He had also run into financial difficulties, so Augustine had entrusted him with a fundus belonging to the Church to pay off the debt.104 It is an extraordinary picture of priests and deacons, most of whom had little before entering Augustine’s community, but they had still given away what they had.105

The donations we see in these two sermons of Augustine chime exactly with what we find in Chromatius of Aquileia. These are most certainly Brown’s “middling sort,”106 and are absolutely comparable to the deacon, lector, and notarius who appear together in a mosaic donation panel on the floor of San Canzian d’Isonzo.107 They also make abundantly clear the extraordinary nature of the ecclesiastical donations of Melania,108 which were totally out of line with what any Christian congregation might expect. The norm seems to have been a field or a house here or there — and not the vast quantities of treasure of-fered by a rich member of a senatorial family, although Augustine pointed out that it would be better if she offered land rather than treasure. And if the gifts of the “middling sort” scarcely compare with what Melania had to offer, it is also likely that they would have failed to measure up to the donations we find recorded on the walls of the twelfth-century temples of Andhra Pradesh, where some 390 inscriptions refer to 336 donors, including 26 kings, 76 feudal lords, 109 officials, 47 royal ladies, as well as 21 merchants.109 Early fifth-century Hippo was not a temple society, even if the small community surrounding Augustine was living the life of the early Christian community in Jerusalem. For the financing of churches in the late fourth and early fifth centuries we might find a better parallel in the funding of madrasas in modern Pakistan, for which we can turn to Francis Robinson:

“According to one account Pakistan had just 189 at independence, but 10,000 by 2002. This growth is a reflection of popular will; they are almost entirely dependent on public subscription. Among the reasons for this are the faith of the common people.”110

Augustine’s sermons provide us with a marvelous snapshot of the endowment of a diocese in the early fifth century. But we are still far from the landed Church of the late sixth and early seventh centuries. Augustine tells us himself that his father’s property was the equivalent of about a twentieth of that of the bishopric of Hippo,111 and he certainly did not come from a wealthy family.112 On the other hand, there had been some accumulation of Church land already by the time of Chalcedon in 451, when we find the recommendation that a bishop appoint an oeconomus to deal with the financial administration of the diocese.113 This was a point specifically cited by the Visigothic bishops at the Fourth Council of Toledo (633).114 The increasing references to the need for property managers that we find in the late fifth and sixth centuries are an indication of the accumulation of property.115 Thus we have what Brown has called the “rise of the managerial bishop.”116

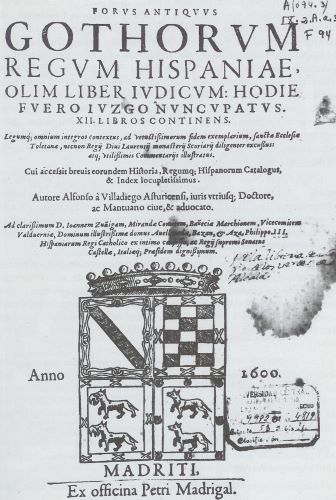

In addition, Chalcedon also put checks on the alienation of land in the possession of the Church.117 Already as early as 314 the Council of Ancyra had annulled the alienation of goods during an episcopal vacancy.118 The Apostolic Canons, from fourth-century Syria, which were accepted by the Council in Trullo in 692, but rejected at the same time by pope Sergius, forbade a bishop from selling what he was administering.119 In 419 the Council of Carthage deposed a bishop who had alienated res ecclesiasticae.120 Chalcedon insisted that synodal approval was needed if a bishop wanted to sell property.121 A Roman synod in 502 stated that rural and urban estates, gems, gold, silver, and cloth donated to the Church for the poor should not be transferred to anyone else,122 and the canons of the synod concluded with a letter of pope Symmachus forbidding the alienation of Church property, the usufruct of which was only to provide for priests, the poor, and peregrini.123 This was, in fact, a reaffirmation of a ruling of the senate, issued by Odoacer, in 483.124 It was reiterated by Theodoric the Ostrogoth in a law of 508.125 On numerous occasions Gregory the Great stated that the possessions of the Church could not be alienated.126 The point is also enshrined in the Liber Diurnus.127 In addition, in several letters the pope insisted on the need for an inventory of the property of a particular church.128 The Merovingian Church councils repeatedly stressed the inalienability of Church property.129 In Spain, the Council of Lérida in 546 legislated to protect the possessions of a church on the death of a bishop (sacerdos),130 and further legislation was added by the Councils of Valencia (549) and IX Toledo (655).131 Among the Antiquae of the Lex Visigothorum is a requirement that inventories of land committed to priests should be drawn up, to ensure that no loss was suffered.132 The question of appropriation of Church property by bishops is also the subject of a law of Wamba from 675.133 In the East, Justinian legislated in 537 to prevent the alienation of Church land.134

On the other hand, a number of leading clergy, including Ambrose and Gregory the Great, did allow for the alienation of property to support the poor, ransom captives, and construct cemeteries.135 The alienation of wealth (usually of treasure) to fund the ransom of captives is a recurrent theme in episcopal hagiography:136 it could be a mark of sanctity, although it could also, clearly, be contentious — in the context of the discussion of whether a bishop should melt down liturgical vessels to redeem those held captive.137 The 502 Rome synod stated explicitly that it was wrong, even sacrilegious to give away what had been offered pro salute vel requie animarum suarum.138

In the conciliar evidence Church property and its protection becomes a constant from the sixth century onwards. It is raised in the canons of the first Council of Orléans, which states that:

concerning the gifts (oblationibus) and lands (agris) which our lord the king has deigned to give as a personal gift to churches, or those that, inspired by God, he will give to those that do not yet have them, together with a concession of immunity to those lands and priests, we declare that it is entirely right that all that God will deign to give as revenue should be used for the repair of churches, the support of bishops, and of the poor, and of the ransom of captives, and that the clergy should be committed to support the work of the Church.139

Here we effectively have a statement of the Quadraticum, but associated with royal land donation. It is certainly the earliest reference to the concession of land to the Church by a Merovingian king — and although several churches and monasteries claimed foundation by Clovis, none of the documentation is genuine.140 Our authentic charters do not start until the seventh century.141 But in this canon we have a reference to what appears to be a number of grants.

We have no genuine charters for early sixth century Francia (although we now have a charter from 522 for Spain),142 but we do have other reasons for thinking that it was in the sixth century that large-scale donations to the Church started to become more common. Above all, we have the evidence of diocesan histories that were set down in the Carolingian period. For instance, like other Carolingian histories, the Actus Pontificum Cenomannis includes the texts of the testaments of bishops. Certainly, we have to be careful when using these documents: there is every reason to think that some of the testamenta preserved in the histories are forgeries, or contain forged elements, which the Carolingian episcopate intended to use in its claims to property.143 At the same time, the chronology of land-giving that we find in these histories is reasonably consistent, and tallies with the impression to be gained from other types of document. The diocesan histories tend to record episcopal wills from the sixth century and later: thus, in the History of the Bishops of Le Mans, although there is reference to improbable gifts of land from the time of “Decius, Nerva and Trajan,”144 as well as extraordinary lists of gifts of wax for the pre-Constantinian period,145 the main evidence relating to property donation dates from the episcopates of bishop Innocent (who died in 559) and his successors.146 The History of the Bishops of Auxerre lists the supposed gifts of Germanus in the fifth century (surely an attempt to associate donations with the most famous saint of the diocese), but there-after information on land grants begins with bishop Aunarius in the last quarter of the sixth century.147 The earliest will referred to in Flodoard’s History of the Church of Rheims is that of Bennadius (d. 459), but this first testament mentions no land, only a liturgical vessel and coin.148 The version of the will of his successor, Remigius, who died in 533, which is preserved by Flodoard, is regarded as heavily tampered with, but a shorter version preserved by Hincmar is thought to be authentic.149 It does include land-grants, but the scale of donation is not vast. Further wills are listed for the late sixth and seventh centuries in Flodoard’s account. These Histories, thus, give the impression that the major transfer of land to the Church took place in the sixth century and later.

The Spanish testamentary evidence is a good deal slighter than that from Merovingian Gaul. The very substantial donation of property given to Mérida by the mid-sixth-century bishop Paul in his will is noted in the Vitas Patrum Emeretensium, but unfortunately the account provides no detail.150 At the end of the Tenth Council of Toledo (656), there was a discussion of the testament of bishop Riccimir of Dumio, which was declared invalid on account of its conflict with the earlier will of Martin of Braga (d. 579), and was condemned as being injurious to Church property,151 but again no detail is supplied. More informative is the will of bishop Vincent of Huesca (557–576?), much of which confirms a grant he had made to the monastery of San Martín de Asán in 551 when he was still a deacon, but the text is unfortunately incomplete, and in any case the amount of prop-erty listed is not considerable.152 Although the Visigothic material is informative about testamentary law, it tells us little about the scale of donation to churches.

Like the Liber Pontificalis, Agnellus’s History of the Bishops of Ravenna does not have much to say about land, although it does note that bishop Maximian secured the woods of Vistrum in Istria for the diocese,153 and that bishop Agnellus acquired the estate of Argentea.154 Above all, it records Justinian’s grant of the property of the Goths in cities, suburban villas, and hamlets.155 This, in all probability, was the most important of the donations to Ravenna. The Codex Bavarus of the tenth century gives us an indication of the scale of landholding in the century before it was compiled. There are records of 168 transactions, most of which are leases, which show us the extent of the Church’s holdings in nine territoria of central Italy (mainly in the region of the Marche). Only rarely do they provide evidence of the date the property was acquired, but donations are listed for the reign of Heraclius,156 and for the episcopate of Damian (689–705),157 while 24 of the leases are clearly dated to the seventh and eighth centuries.158 Moreover, in the case of every lease we can assume that the property had already passed into the hands of the Church of Ravenna before the grant was made. Taken together with the evidence that we have already noted for the Sicilian landholdings of the Church of Ravenna,159 it would seem that the major period of Church endowment involving numerous very sizeable gifts was, as Lesne argued, the sixth and seventh centuries, although Cracco Ruggini is also compelling in emphasizing the acquisition of smaller properties in the fifth century, which were absorbed into larger ones.

This coincides neatly with the chronology of references to the Quadripartum. The earliest allusion to the fourfold division comes from pope Simplicius (468–483),160 and the first full definition is to be found in the Decreta sent by pope Gelasius (492–495) to the bishops of Lucania161 — and we might note that John the Deacon in his Life of Gregory the Great regarded the Quadripartum as coming from a book of Gelasius.162 There is a further reference in a letter of pope Felix IV (526–530) to Ecclesius of Ravenna, preserved by Agnellus, although it is specific only about the fourth part of the church’s revenue due to the clergy.163 It does, however, reveal that the sum amounted to 3,000 solidi, which as we have seen is far less than what would have been due later in the century. The best-known statement comes from Gregory the Great in c. 600 in the Responsiones to Augustine of Canterbury,164 and there are additional letters in the pope’s Register that shed light on the working of the Quadripartum.165 In addition, a conciliar statement which alludes to the Quadripartum is to be found in the canons of the Council of Orléans of 511.166 The notion of the Quadripartum was, therefore, being promulgated just as the scale of ecclesiastical land-owning was escalating, and thus at the time when the Church had more revenue to distribute.

We need to ask what lies behind the formulation of the Quadripartum and its chronology. Of course, there may have been specific reasons that only applied to certain regions — and which are reflected in the differing formulations of the Quadripartum, and indeed in the Spanish preference for the tertia. For instance, one possible reason for Clovis’s largesse, which provides the context for the statement on the division of ecclesiastical revenue in the Council of Orléans, may be the king’s deliberate imitation of what he understood to be the actions of Constantine. In Gregory of Tours he appears as a novus Constantinus.167 As we have seen, in the Life of Silvester contained in the Liber Pontificalis, which was composed a generation after Clovis’s death, the first Christian emperor was remembered as being notable for his donation of property to the Church of Rome.168 That Clovis had an interest in Rome is suggested by the Liber Pontificalis, which states that he sent a votive crown to St. Peter’s during the pontificate of Hormisdas (514–523).169 The date must be wrong, but there is no reason to doubt the gift. There is also a possibility that the Frankish king had an interest in the church of St. Martin in Rome.170

The formulation of the Quadripartum given in the Council of Orléans is also unusual in its allocation of one quarta to the ransoming of captives. Following close on Clovis’s victories against the Visigoths, the concern presumably reflects a very specific situation, although as we have seen, the fate of captives attracted particular attention on either side of 500, and also in the pontificate of Gregory the Great.171 Care for those in prison is, of course, advocated by Christ in Matthew 25:36: “when I was ill you came to my help, when in prison you visited me.” Pauline Allen and Bronwen Neil have noted references to episcopal involvement in the ransoming of captives, and also to support for refugees, throughout the late antique period. Augustine, for instance, writes about redeeming men from Galatian people-traffickers.172 Allen and Neil also note those displaced by the barbarians, including aristocratic refugees from Africa following Gaiseric’s takeover, who appear in papal letters and in the writings of Theodoret of Cyrrhus.173 And they point to the presence of religious refugees fleeing from pro- or anti-Chalcedonian persecution.174

It may seem tempting when considering the expansion of ecclesiastical landholding of the late fifth and sixth centuries to turn to Dodds’s notion of an “Age of Anxiety,”175 and to apply it to the period of the Völkerwanderung and the collapse of the Empire. There is even a convenient Ravenna charter of donation to the Church, where land is given in exchange for protection adversus violentus impetos.176 But the charter dates to 556–561, the last stages of the Gothic Wars. It does not allow us to ascribe the increase in the donation of land to the Church to the period of the arrival of the barbarians, or of their settlement. And this negative conclusion gels suggestively with the arguments of Pauline Allen and Bronwen Neil in their study of episcopal crisis management. Their analysis of the epistolary evidence relating to papal and episcopal charitable activity draws attention to the lack of reference to the barbarians — two papal letters, one from Innocent I and one from Pelagius I, and one letter of Augustine.177 There are, of course, more references to barbarians in the letters of Sidonius and his successors, who lived in regions controlled by the incomers.

Although, as Allen and Neil have vividly demonstrated, crisis management was a major issue for the Church, it may only be a secondary factor in the growth in ecclesiastical landholding in the course of the fifth, sixth, and seventh centuries. Not surprisingly, it would seem that the increase in Church property went hand in hand with the growth in the number of ecclesiastics and indeed of monks and nuns. Admittedly, we have very little evidence to allow us to calculate the expansion of the clergy, but there is ecclesiastical legislation, from the councils of IV Orlé-ans (541),178 II Braga (571),179 and the 597 Council of Toledo,180 requiring that provision was made for priests when churches were founded. The tomus for XVI Toledo (693) actually reverses the equation: king Egica directed that every church with ten slaves or more, however poor, must have a priest, although those with fewer than ten slaves were to be attached to another parish.181 For some dioceses we have good evidence for church foundation throughout the sixth century. Above all, the information supplied by Gregory of Tours allows us to see the increase in churches in his diocese, episcopate by episcopate, until there were at least 58 in his own day.182

To the evidence of vicus churches, we can add that of monasteries. In parts of the East, the number of monastic communities would seem to have been very substantial already by the early fifth century, even if Ewa Wipszycka has seriously challenged the picture presented by Palladius, Jerome, and the Historia Monachorum, following her detailed investigation of the papyrus evidence.183 The West certainly lagged behind Egypt and Palestine in the development of monasticism. But there seem to have been some 220 monasteries in Francia by 600 and 550 by the early eighth century.184 And some of these monasteries had very considerable numbers. There may well have been between 300 and 400 monks at Corbie,185 300 monks and 100 pueri at St. Riquier,186 and perhaps 220 at Luxeuil.187

Large numbers of monks needed massive donations in order to provide them with the basic necessities of life. For St. Martin de Tours we do not have a list of monks, but the so-called documents comptables, edited by Gasnault, supply 1,000 per-sonal names (essentially of tenants) and 137 place-names, providing an insight into the dues owed to the abbey during the abbacy of Agyricus in the second half of the seventh century.188 The community of St. Martin was close to Tours itself, but in many cases monasteries with large communities were not based in urban centers, but rather in the countryside, thus requiring a redistribution of resources to areas that had not been places of significance in the late Roman World — including, for instance, both Luxeuil and Bobbio. Historians of early medieval Ireland have been more sensitive to the impact on the landscape of the foundation of sizeable communities189 than have specialists of the monastic church on the continent.

Support for the clergy is a constant in the allocation of the Quadripartum: the bishop and the clergy are each allocated a quarter by both Gelasius and Gregory the Great,190 and it is clear from a letter of Felix IV that the clergy of Ravenna expected their fourth.191 In the version to be found in the Council of Or-léans there is the provision of alms for clerics (sacerdotes).192 Clergy also feature consistently in the reference to the threefold division of ecclesiastical revenue in Spain. They are listed as recipients of a tertia in the First Council of Braga.193 In Visigothic Spain, as we have seen, no allowance is made for the poor or for captives, but the clergy were supported,194 while in the tomus for XVI Toledo (693) the upkeep of the church building was to fall to the bishop, who could draw on the tertiae parrochialium baselicarum.195 The question of the state of the buildings in Spain was clearly a serious one, for it also appears in the canons of IX Toledo (655).196

Provision for the clergy was a constant issue, and concern for the poor attracted almost as much attention,197 although Allen and Neil have noted that there were moments when they attracted particular concern, as for instance during the pontificate of pope Pelagius, because of the hardship caused by the Gothic Wars.198 Care for the poor was understood to be a central feature of Christian charity from very early on, as has been shown in a number of major studies.199 Brown in particular has stressed the importance of the phrase amator pauperum as an epithet for a bishop,200 and, along with Toneatto,201 has drawn attention to the phrase necator pauperum (or a variant thereof ), used in the canons of the Councils of Vaison (442), Agde (506), Orléans (549), Arles (554), Paris (556–573), Tours (567), Mâcon I (581–583), Valence (583–585), and Paris (614), as well as the Statuta Ecclesiae Antiqua, to describe those who tried to despoil the Church of property.202 Concern for the poor is even stated as being one of the two reasons for Guntram summoning the first Council of Mâcon, the other being causae publicae.203 The second Council of Tours (567) states firmly that each civitas had to look after its poor and needy as best it could.204 In Francia, in return for the Church’s support, the poor, and particularly the matricularii registered on the poor-lists of the diocese, were a force that might turn out in support of a bishop, as indeed might those who had been ransomed by the Church.205 It is not surprising to find that provision for the poor occurs in almost all the versions of the Quadripartum. Moreover, despite the fact that the Spanish tripartite division of Church wealth makes no equivalent allowance, concern for the poor, although not the phrase necator pauperum, appears in IV Toledo (633),206 VI Toledo (638),207 and X Toledo (656).208

The Church needed funds to carry out its charitable duties in caring for the poor, widows, and orphans, ensuring the upkeep of churches, and providing for the sustenance of the clergy. And on occasion it was also faced with the ransoming of captives. Claudia Rapp has stressed the emergence of the bishop as “a new urban functionary.”209 For all charitable and religious actions the Church needed regular revenue, and that could not come from the donation of treasure. Moreover, the alienation of liturgical objects was distinctly questionable — although a charismatic bishop might turn the action into a virtue.210

Essentially, the Church needed revenue from land. The creation of a propertied Church was a straightforward matter of necessity. The growth in the number of clergy and in the number of churches and monasteries, as well as the growing expense of the liturgy (as can be seen in the need for lights), together with the burden of charity, especially in times of crisis, effectively led to the creation of a new ecclesiastical economy — of what I would call a temple society. And this largely occurred in the course of the late fifth and sixth centuries, coming to fruition only at the end of the period. This chronology is important, because it implies that the economic development of the Church comes after the great spiritual and theological achievements of the period before Chalcedon.

What we therefore have is a perfect storm of a political crisis, which had major social implications, at precisely the moment that the institution of the Church was expanding — a development that went hand in hand with a growing recognition that churches needed landed endowment. The result, by the beginning of the eighth century, was a massively wealthy Church, with enormous estates, amounting perhaps to a third of western Europe, which supported a body of clergy and other religious, which was numerically a relatively small but significant segment of the population, while caring for the marginal of society. This is as much a matter of economic as of religious history. As we will see, the economic importance of the Church also challenges the notion of the centrality of the royal court in the seventh century, in Francia and perhaps in Visigothic Spain, although scarcely in the Exarchate, and probably not in the Lombard kingdom. The Church was arguably the key socio-economic institution of the period. Throughout the Latin West, the accumulation of property by the Church, and the revenue that it had at its disposal, which was distributed in line with a particular set of socio-religious ideals, means that we cannot merely see churchmen as members of an aristocratic elite. They were involved in the distribution and redistribution of wealth along totally novel lines — lines that are not dissimilar from those laid down by Appadurai and Appadurai Breckenridge in their definition of a temple society.211 The Church of the late- and post-Roman West effected a more fundamental socio-economic revolution than most economic historians have acknowledged.

Endnotes

- E.g., A.H.M. Jones, The Later Roman Empire 284–602 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1964), 895.

- Ibid., 1371, n. 55.

- Jan-Olof Tjäder, Die nichtliterarischen lateinischen Papyri Italiens aus der Zeit 445–700, 2 vols. (Lund: Gleerup, 1955–1982), vol. 1, doc. 12, 294–99.

- Merle Eisenberg and Paolo Tedesco, “Seeing the Churches Like the State: Taxes and Wealth Redistribution in Late Antique Italy,” Early Medieval Europe 29, no. 4 (2021): 505–34, at 525–28. Earlier documents relate to estates that were subsequently acquired by the Church.

- Kate Cooper, “Property, Power, and Conflict: Rethinking the Constantinian Revolution,” in Making Early Medieval Societies: Conflict and Belonging in the Latin West, 300–1200, ed. Kate Cooper and Conrad Leyser (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 16–32, at 27.

- Lellia Cracco Ruggini, Economia e socièta nell’ “Italia annonaria”: Rapporti fra agricoltura e commercio dal IV al VI secolo d.C. (Milan: A. Giuffre, 1961), 458: “Sopratutto in grazia al grande numero di donazioni, e per la tendenza della grande proprietà a riassorbire quella più piccola, il patrimonio fondi-ario ecclesiastico si era andato di fatto estendendo in maniera ingentissima nel corso del V e VI secolo.”

- Émile Lesne, Histoire de la propriété ecclésiastique en France, vol. 1: Époques romaine et mérovingienne (Lille: R. Giard, 1910), vol. 1, 143: “Née à l’époque romaine, la propriété ecclésiastique attent en France l’âge adulte au temps des Mérovingiens. Les radicelles qui s’enfoncèrent, dès le Ve siècle, en la terre des Gaules, preparaient la croissance de l’arbre qui, aux VIe et VIIe siècles, dresse une cime déjà superbe.”

- Jean Gaudemet, L’Église dans l’empire romain (IVe–Ve siècles) (Paris: Sirey, 1958), 296: “En Gaule, l’institution d’héritier au profit d’une église n’apparaît pas avant la fin du Ve siècle.”

- Federico Montinaro, “Les fausses donations de Constantin dans le Liber Pontificalis,” Millennium 12 (2015): 203–30.

- Liber Pontificalis, 35.3–4, ed. Louis Duchesne, “Liber Pontificalis”: Texte, Introduction et Commentaire, 2 vols. (Paris, 1886–1892), vol. 1, 202. See Montinaro, “Les fausses donations de Constantin dans le Liber Pontificalis,” 206–7, 225–28; Rosamond McKitterick, Rome and the Invention of the Papacy: The “Liber Pontificalis” (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020), 101–16.

- Liber Pontificalis, 34.9, 12, 13–16, 19–23, 25–27, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 173–87. My figures differ slightly from those provided by Montinaro, “Les fausses donations de Constantin dans le Liber Pontificalis,” 206–7, 225–28; perhaps we have included or excluded certain estates. The ballpark figures, however, are similar. See now Eisenberg and Tedesco, “Seeing the Churches Like the State,” 519–25.

- Michael Mulryan, “A Few Thoughts on the tituli of Equitius and Sylvester in the Late Antique and Early Medieval Subura in Rome,” in Religious Practices and the Christianisation of the Late Antique City (4th–7th century), ed. Aude Busine (Boston and Leiden: Brill, 2015), 166–78; Julia Hillner, “Families, Patronage, and the Titular Churches of Rome, c. 300–c. 600,” in Religion, Dynasty and Patronage in Early Christian Rome, ed. Kate Cooper and Julia Hillner (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 225–61, at 230.

- Liber Pontificalis, 34.3, 33, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 170–71, 187.

- Liber Pontificalis, 34.28–29, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 183–84.

- Liber Pontificalis, 34.30, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 184–85.

- Liber Pontificalis, 34.31, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 185–86.

- Liber Pontificalis, 34.32, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 186–87.

- Federico Marazzi, I “patrimonia sanctae Romanae ecclesiae” nel Lazio (secoli IV–X): struttura amministrativa e prassi gestionali, Nuovi studi storici 37 (Rome: Nella Sede Dell’Istituto Palazzo Borromini, 1998), 25–47.

- Charles Pietri, Roma Christiana: recherches sur l’Église de Rome, son organisation, sa politique, son idéologie de Miltiade à Sixte III (311–440), 2 vols. (Paris and Rome: École française de Rome, 1976), 79. Also, Charles Pietri, “Évergétisme et richesses ecclésiastiques dans l’Italie du IVe à la fin du Ve siècle: l’exemple romain,” Ktèma: civilisations de l’Orient, de la Grèce et de Rome antiques 3 (1978): 317–37, reprinted in Charles Pietri, Christiana respublica: Éléments d’une enquête sur le christianisme antique (Paris and Rome: École française de Rome, 1997), 813–33.

- Paolo Liverani, “Osservazioni sul Libellus delle donazioni Costantiniane nel Liber Pontificalis,” Athenaeum 107 (2019): 169–217.

- Raymond Davis, The Book of the Pontiffs (Liber Pontificalis): The Ancient Biographies of the First Ninety Roman Bishops to A.D. 715 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1989), xxix–xxxvi; McKitterick, Rome and the Invention of the Papacy, 111.

- Montinaro, “Les fausses donations de Constantin dans le Liber Pontificalis.”

- Richard Westall, “Constantius II and the Basilica of St. Peter in the Vatican,” Historia 64, no. 2 (2015): 205–42, at 207, 230–31.

- Marco Maiuro, “Archivi, amministrazione del patrimonio e proprietà imperiali nel Liber Pontificalis. La redazione del Libellus imperiale copiato nell Vita Silvestri,” in La proprietà imperiali nell’Italia romana: Economia, produzione, amministrazione, ed. Daniela Pupillo (Florence: Le lettere, 2007), 235–58.

- Paolo Tedesco, “Economia monetaria e fiscalità tardoantica: una sintesi,” Annali dell’Istituto Italiano di Numismatica 62 (2016): 107–49, at 122–24.

- Davis, The Book of the Pontiffs (to A.D. 715), xix–xxvi; Dominic Janes, God and Gold in Late Antiquity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 57–58. For the likelihood that the lists of donations of treasure do relate to gifts made by Constantine, Liverani, “Osservazioni sul Libellus delle don-azioni Costantiniane nel Liber Pontificalis,” esp. 181–86.

- Olympiodorus, frag., 41.2, ed. Roger C. Blockley, The Fragmentary Classicising Historians of the Later Roman Empire, vol. 2 (Liverpool: Cairns, 1983), 204–6; Chris Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages: Europe and the Mediterranean 400–800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), 162. Of course Olympiodorus may exaggerate.

- David Hunt, “The Church as a Public Institution,” in The Late Empire A.D. 337–425, ed. Averil Cameron and Peter Garnsey, The Cambridge Ancient History 13 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 238–76, at 261. See also Jacob A. Latham, “From Literal to Spiritual Soldiers of Christ: Disputed Episcopal Elections and the Advent of Christian Processions in Late Antique Rome,” Church History 81 (2012): 298–327, at 302–3.

- Hunt, “The Church as a Public Institution,” 261.

- See above.

- Codex Theodosianus, 10.1.8; also, 5.13.3, https://droitromain.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/.

- Montinaro, “Les fausses donations de Constantin dans le Liber Pontificalis,” 2 1 7.

- For the chronology of composition, see McKitterick, Rome and the Invention of the Papacy, 25–35, with the modifications required by Montinaro, “Les fausses donations de Constantin dans le Liber Pontificalis,” 221–29.

- Council of Ancyra (314), c. 15, ed. Giovanni Domenico Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum nova et amplissima collectio (Florence, 1759), vol. 2, cols. 513–39; Council of Carthage (419), c. 26, ed. Charles Munier, Concilia Africae 345–525, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina 144 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1974), 109; Council of Chalcedon, cc. 3, 24, 26, https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3811.htm; Statuta Ecclesiae Antiqua, c. 50, ed. Charles Munier, Concilia Galliae, c. 314–c. 506, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latinorum 148 (Turnhout: Brepols, 1968), 174; Apostolic Canons, c. 39, https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf07/anf07.ix.ix.vi.html. For legislation on the inalienable nature of Church land, see also Stefan Esders, “‘Because their Patron Never Dies’: Ecclesiastical Freedmen under the Aegis of ‘Church Property’ in the Early Medieval West (6th–11th centuries),” Early Medieval Europe 29, no. 4 (2021): 565–68.

- Avitus, ep. 44, ed. Rudolf Peiper, Alcimi Ecdicii Aviti Viennensis episcopi Opera quae supersunt, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Auctores Antiquis-simi 6.2 (Berlin: Weidmann, 1883), 73–74: “Quicquid habet ecclesiola mea, immo omnes ecclesiae nostrae, vestrum est de substantia, quam vel servas-tis hactenus vel donastis”; Danuta Shanzer and Ian Wood, trans., Avitus of Vienne: Letters and Selected Prose (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2002), 218.

- Justinian, Nov 7.2.1, ed. Rudolf Schöll and Wilhem Kroll, Corpus Iuris Civilis, Novellae, 6th edn. (Berlin: Weidemann, 1928), 52, https://droitromain.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/; David J.D. Miller and Peter Sarris, trans., The Novels of Justinian: A Complete Annotated English Translation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 781, 117: “et et sacrae res a communibus et publicis, quando omnis sanctissimis ecclesiis abundantia et status ex im-perialibus munificentiis perpetuo praebetur.” See Esders, “‘Because Their Patron Never Dies’,” 565–68.

- Gaëlle Calvet-Marcadé, Assassin des pauvres: l’église et l’inaliénabilité des terres à l’époque carolingienne (Turnhout: Brepols, 2019), 195–96.

- Liber Pontificalis, 34.1, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 170.

- Liber Pontificalis, 38.1, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 211.

- Eusebius, Life of Constantine, 4.61–62, trans. Averil Cameron and Stuart Hall (Oxford: Clarendon, 1999), 177–78, with commentary on 340–41.

- For the building, Hugo Brandenburg, Ancient Churches of Rome from the Fourth to the Seventh Century (Turnhout: Brepols, 2004), 37–54.

- Montinaro, “Les fausses donations de Constantin dans le Liber Pontificalis,” 218–21.

- Liber Pontificalis, 42.6, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 221–22: the property on the Clivus Patricius.

- Montinaro, “Les fausses donations de Constantin dans le Liber Pontificalis.”

- Davis, The Book of the Pontiffs (to A.D. 715), xxix–xxx; McKitterick, Rome and the Invention of the Papacy, 111.

- Westall, “Constantius II and the Basilica of St. Peter in the Vatican.” See also John Curran, Pagan City and Christian Capital: Rome in the Fourth Century (Oxford: Clarendon, 2000), 113–14.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res gestae, 16.10, 17; 17.4. http://thelatinlibrary.com/ammianus.html. On Constantius in Rome, Mark Humphries, “Emperors, Usurpers, and the City of Rome: Performing Power from Diocletian to Theodosius,” in Contested Monarchy: Integrating the Roman Empire in the Fourth Century AD, ed. Johannes Wienand (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 151–68, at 158–60; Mark Humphries, “Narrative and Subversion: Exemplary Rome and Imperial Misrule in Ammianus Marcellinus,” in Some Organic Readings in Narrative: Ancient and Modern, ed. Ian Redpath and Fritz-Gregor Hermann (Groningen: Eelde & Barkhuis, 2019), 233–54.

- For Felix II, see Curran, Pagan City and Christian Capital, 129–37, which notes the importance of the period of the schism between Felix and Liberius for church building.

- Liber Pontificalis, 38, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 211.

- Socrates Scholasticus, Historia Ecclesiastica, 2.47, ed. Günther C. Hansen, Die griechischen christlichen Schriftsteller (Berlin: Akademie, 1995), 186; Philostorgius, Historia Ecclesiastica, 6.5, Patrologia Graeca 65, cols. 459–638, at col. 535.

- Liber Pontificalis, 37–38, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 207–11.

- Athanasius, Historia Arianorum, 75.3–7, ed. Hans-George Opitz, Athanasius Werke 2.1 (Berlin: De Gruyter, 1935), 225; Richard Flower, trans., Imperial Invectives against Constantius II, Athanasius of Alexandria, Hilary of Poitiers and Lucifer of Cagliari (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2016). Timothy Barnes, Athanasius and Constantius: Theology and Politics in the Constantinian Empire (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1993), 118. Also, Mark Humphries, “In nomine Patris: Constantine the Great and Constantius II in Christological Polemic,” Historia 46 (1997): 448–64, at 454–57.

- Collectio Avellana, 1.1–3, ed. Otto Günther, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum 35.1 (Vienna: F. Tempsky, 1895), 1–2.

- Jerome, De viris illustribus, 98, Patrologia Latina 23, cols. 181–206.

- Socrates Scholasticus, Historia Ecclesiastica, 2.37, ed. Hansen, Die griechischen christlichen Schriftsteller, 152–63.

- Rufinus, Historia Ecclesiastica, 10.23, Patrologia Latina 21; Theodoret, Historia Ecclesiastica, 2.17.3, Patrologia Graeca 82, cols. 883–84; Sozomen, Historia Ecclesiastica, 4.11, Patrologia Graeca 67, cols. 143–45. Barnes, Athanasius and Constantius, 276, n. 60, prefers to emphasize his orthodoxy.

- Westall, “Constantius II and the Basilica of St. Peter in the Vatican,” 242.

- Liber Pontificalis, 38, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 211.

- Liber Pontificalis, 39.1, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 212.

- Liber Pontificalis, 42.3, 6, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 220–22.

- Liber Pontificalis, 46.3, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 232–33.

- Tyler Lansford, The Latin Inscriptions of Rome: A Walking Guide (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009), 176–77; McKitterick, Rome and the Invention of the Papacy, 112.

- Brandenburg, Ancient Churches of Rome, 103.

- Bronwen Neil, “Imperial Benefactions to the Fifth-Century Roman Church,” in Basileia: Essays on Imperium and Culture in Honour of E.M. and M.J. Jeffreys, ed. Geoffrey Nathan and Lynda Garland (Sydney: University of New South Wales, 2011), 55–66.

- Liber Pontificalis, 36.3, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 205; Raymond Davis, trans., The Book of Pontiffs: The Ancient Biographies of the First Ninety Roman Bishops to AD 715, revised edn. (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2000), 27.

- Liverani, “Osservazioni sul Libellus delle donazioni Costantiniane nel Liber Pontificalis,” 182–84.

- Curran, Pagan City and Christian Capital, 116–57, provides a detailed survey of the evidence for the period 337–84.

- Liber Pontificalis, 47.1, 6, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 238–39.

- Hillner, “Families, Patronage, and the Titular Churches,” 241.

- Mariano Armelini, Le chiese di Roma dal secolo IV al XIX (Rome: Tipografia Vaticana, 1891), 815–17. Liber Pontificalis, 49.1, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 249. On Valila’s donation to the church of Tivoli, see Montinaro, “Les fausses donations de Constantin dans le Liber Pontificalis,” 209. On Valila see, now, Umberto Roberto, “La corte di Antemio e i rapporti con l’Oriente,” in Procopio Antemio imperatore di Roma, ed. Fabrizio Oppedisano (Bari: Edipuglia, 2020), 141–76, at 148, 168–70; Silvia Orlandi, “L’epigrafia sotto il regno di Antemio,” in Procopio Antemio imperatore di Roma, ed. Fabrizio Oppedisano (Bari: Edipuglia, 2020), 177–97, at 188–91. It is worth noting the funding of Sta. Agata dei Goti by Valila’s rival, the Arian Ricimer: Ralph Mathisen, “Ricimer’s Church in Rome: How an Arian Barbarian Prospered in a Nicene World,” in The Power of Religion in Late Antiquity, ed. Noel Lenski and Andrew Cain (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009), 307–25.

- Hillner, “Families, Patronage, and the Titular Churches,” 241.

- Marazzi, I “Patrimonia sanctae Romanae ecclesiae” nel Lazio, 85–107.

- Satyrus had left his property to his siblings, who were to act as stewards, distributing the proceeds to the poor: Ambrose, De excessu fratris Satyri, 1.59–60, 62, ed. Otto Faller, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum 73 (Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences Press, 1955), 209–325. See also On the Death of Satyrus (Book I), trans. H. de Romestin, E. de Romestin, and H.T.F. Duckworth, in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, Second Series, vol. 10, ed. Philip Schaff and Henry Wace (Buffalo: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1896), revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight; https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/34031.htm.

- Paulinus of Milan, Vita Ambrosii, 37, ed. Michele Pellegrino, Paolino di Milano, Vita di S. Ambrogio (Rome: Editrice Studium, 1961), 103–4; Frederick R. Hoare, trans., The Western Fathers (London: Sheed and Ward, 1954).

- Paulinus of Nola, ep. 5.6, ed. Guilelmi de Hartel, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum 29 (Vienna: Vindobonae, 1894), 28–29; Sulpicius Severus, Vita Martini, 10, ed. Jacques Fontaine, Sulpice Sévère, Vie de saint Martin, Sources Chrétienne, 133–134 (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1967), 273–75; Pomerius, De vita contemplativa, 2.9, Patrologia Latina 59, cols. 453–54; Sister Mary Josephine Suelzer, trans., Julianus Pomerius, the Contemplative Life (Westminster: Newman Press, 1947).

- Palladius, Historia Lausiaca, 16, 64, ed. Adelheid Hübner, “Historia Lausiaca”: Geschichten aus dem frühen Mönchtum (Freiburg: Herder, 2016), 136–39, 315; Jerome, ep. 108, ed. Isidore Hilberg, Sancti Eusebii Hieronymi Epistolae, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum 55 (Leipzig: Freytag, 1912), 306–51; Gerontius, Vita Melaniae, 20–21, ed. Denys Gorce, Vie de sainte Melanie (Βίος τῆς Ὁσίας Μελάνης), Sources Chrétiennes 90 (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1962), 169–73; Richard Goodrich, Contextualizing Cassian: Aristocrats, Asceticism, and Reformation in Fifth-Century Gaul (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 162–64.

- Liber Pontificalis, 41.3, ed. Duchesne, vol. 1, 218.

- Conrad Leyser, “Through the Eyes of a Deacon: Lesser Clergy, Major Donors, and Institutional Property in Fifth-Century Rome,” Early Medieval Europe 29, no. 4 (2021): 487–504.

- Cracco Ruggini, Economia e società, 458; Lesne, Histoire de la propriété ec-clésiastique en France, vol. 1, 143.

- Hunt, “The Church as a Public Institution,” 261–62.

- Samuel J.B. Barnish, “Transformation and Survival in the Western Senatorial Aristocracy, c. A.D. 400–700,” Papers of the British School at Rome 56 (1988): 120–55; Wickham, Framing the Early Middle Ages, 163–64, 203–19; Latham, “From Literal to Spiritual Soldiers of Christ,” 318.

- Montinaro, “Les fausses donations de Constantin dans le Liber Pontificalis,” 216.

- Rita Lizzi Testa, Vescovi e strutture ecclesiastiche nella città tardoantica: l’Italia Annonaria nel IV–V secolo d.C. (Como: Edizioni New Press, 1989), 166.

- Peter Brown, Power and Persuasion in Late Antiquity: Towards a Christian Empire (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1992), 95.

- Lizzi Testa, Vescovi e strutture ecclesiastiche nella città tardoantica, 118.

- Ibid., 142, n. 10, 157.

- Ibid., 156, 159–60. On the mosaic floors see also Bryan Ward-Perkins, From Classical Antiquity to the Middle Ages: Urban Public Building in Northern and Central Italy AD 300–850 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1984), 53, with n. 5.

- Brown, Power and Persuasion, 95, with n. 131.

- Rudolf Haensch, “Le financement de la construction des églises pendant l’Antiquité tardive et l’évergétisme antique,” Antiquité tardive 14 (2006): 47–58, at 53.

- Lizzi Testa, Vescovi e strutture ecclesiastiche nella città tardoantica, 166.

- Claire Sotinel, “La recrutement des évêques en Italie aux IVe et Ve siècles. Essai denquête prosopographique,” in Vescovi e pastori in epoca teodosiana, vol. 1 (Rome: Institutum Patristicum Augustinianum, 1997), 193–204; Thomas S. Brown, Gentlemen and Officers: Imperial Administration and Aristocratic Power in Byzantine Italy, A.D. 554–800 (Rome: British School at Rome, 1984), 182.

- Augustine, serm. 355 and 356, Patrologia Latina 39, cols. 1568–81.

- Augustine, serm. 355 and 356, Patrologia Latina 39, cols. 1568–81. On Januarius, Peter Brown, Through the Eye of a Needle: Wealth, the Fall of Rome, and the Making of Christianity in the West, 350–550 AD (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012), 483–84.

- Conrad Leyser, “Augustine in the Latin West, 430–c.900,” in A Companion to Augustine, ed. Mark Vessey (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 456–60; Conrad Leyser, Authority and Asceticism from Augustine to Gregory the Great (Oxford; Clarendon, 2000), 23–24; Conrad Leyser, “Homo pauper, de pauperibus natum: Augustine, Church Property, and the Cult of Stephen,” Augustinian Studies 36, no. 1 (2005): 229–37; Neil B. McLynn, “Administrator: Augustine in His Diocese,” in A Companion to Augustine, ed. Mark Vessey (Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 310–22. See also Brown, Through the Eye of a Needle, 483–85.

- Augustine, serm. 356.10, Patrologia Latina 39, col. 1577; Brown, Through the Eye of a Needle, 483–84; Peter Brown, Poverty and Leadership in the Late Roman Empire, The Menahem Stern Jerusalem Lectures (Lebanon: University Press of New England, 2002), 65.

- Valerio Neri, I marginali nell’Occidente tardoantico: “infames” e criminali nella nascente società cristiana (Bari: Edipuglia, 1996), 120–22; Claudia Rapp, Holy Bishops in Late Antiquity: the Nature of Christian Leadership in an Age of Transition, The Transformation of the Classical Heritage 37 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 214.

- Augustine, serm. 355.1, Patrologia Latina 39, cols. 1569–70.

- Augustine, serm. 356.4, Patrologia Latina 39, col. 1576.

- Augustine, serm. 356.3, Patrologia Latina 39, cols. 1575–76.

- Augustine, serm. 356.4, Patrologia Latina 39, col. 1576.

- Augustine, serm. 356.5, Patrologia Latina 39, col. 1576.

- Augustine, serm. 356.6, Patrologia Latina 39, col. 1576.

- Augustine, serm. 356.7, Patrologia Latina 39, col. 1577.

- Augustine, serm. 356.15, Patrologia Latina 39, cols. 1580–81.

- For another more complicated issue of property, see the discussion of the property of Antoninus of Fussala by Neil B. McLynn, “Augustine’s Black Sheep: The Case of Antoninus of Fussala,” in Istituzioni, Carismi ed Esercizio del Potere (IV–VI secolo d.C.), ed. Giorgio Bonamente and Rita Lizzi Testa (Bari: Edipulgia, 2010), 305–21, at 316–17.

- Brown, Through the Eye of a Needle, 36–39, 124, 212. The “middling sort” is defined by Serena Connolly, Lives Behind the Laws: The World of the “Codex Hermogenianus” (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 139, as “everyone from people just above peasant status […] to the lower reaches of the curial class.”

- Lizzi Testa, Vescovi e strutture ecclesiastiche nella città tardoantica, 156.

- Gerontius, Vita Melaniae, 21, ed. Gorce, Vie de sainte Melanie (Βίος τῆς Ὁσίας Μελάνης), 170–72; Palladius, Historia Lausiaca, 16, ed. Adelheid Hübner, 136–39; Andrea Giardina, “Carità eversiva. Le donazioni di Melania la Giovane et gli equilibri della società tardoromana,” Studi storici 29 (1988): 127–42; Andrea Giardina, “Carità eversiva. Le donazioni di Melania la Giovane e gli equilibri della società tardoantica,” in Hestiasis. Studi di tarda antichità offerti a Salvatore Calderone (Messina: Sicania, 1986), 77–102; Brown, Through the Eye of a Needle, 366.

- P.S. Kanaka Durga and Y.A. Sudhakar Reddy, “Kings, Temples and Legiti-mation of Autochthonous Communities: A Case Study of a South Indian Temple,” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 35 (1992): 145–66, at 155.

- Francis Robinson, “Laboratory Nation: What Happened to Islamic Modernism?” review of Muhammad Qasim Zaman, Islam in Pakistan, Times Literary Supplement 6066 (July 5, 2019): 28–29.

- Augustine, ep. 126.7, ed. Alois Goldbacher, Augustini Epistolae 3, Corpus Scriptorum Ecclesiasticorum Latinorum 44 (Vienna, 1904), http://www.presbytersproject.ihuw.pl/index.php?id=6&SourceID=473.

- Peter Brown, Augustine of Hippo: A Biography (London: Faber & Faber, 1967), 21.

- Council of Chalcedon, c. 26, https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3811.htm.

- Council of Toledo IV (633), c. 48, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 208. Also, Council of Seville II (619), c. 9, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 169. See Edward A. Thompson, The Goths in Spain (Oxford: Clarendon, 2000), 299, citing Council of Mérida (666), cc. 10, 14, ed. Vives, Concilios visigóticos e hispano-romanos, 332–33, 335.

- See above.

- Brown, Through the Eye of a Needle, 496–97.

- Council of Chalcedon, cc. 3, 24, https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3811.htm.

- Council of Ancyra (314), c. 15, ed. Mansi, Sacrorum Conciliorum, vol. 2, cols. 513–39. On alienation, see Esders, “‘Because Their Patron Never Dies’,” 565–68.

- Apostolic Canons, c. 39. https://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf07/anf07.ix.ix.vi.html.

- Council of Carthage (419), ed. Munier, Concilia Africae 345–525, 88–155.

- Council of Chalcedon, c. 26, https://www.newadvent.org/fathers/3811.htm.

- Acta synhodi Romani, a. 502, 7(3), 16, ed. Theodor Mommsen, Cassiodorus Variae, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Auctores Antiquissimi 12 (Berlin: Weidmann, 1894), 446–47, 450.

- Acta synhodi Romani, a. 502, 13–18, ed. Mommsen, Cassiodorus Variae, 448–51. Calvet-Marcadé, Assassin des pauvres, 84–88.

- Hillner, “Families, Patronage, and the Titular Churches,” 248–52.

- Theoderici regis edictum Symmacho papae directum contra sacerdotes substantiae ecclesiarum alienatores A. 508, ed. Georg Heinrich Pertz, Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Leges 5 (Hanover: Hahn, 1875–1889), 169–70.

- Gregory I, Register, 4.36; 5.23; 6.1; 9.75, 142; 12.12, ed. Dag Norberg, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina 140–140A (Turnhout: Brepols, 1982), 256–67, 290, 369–70, 630, 693–94, 985–86.

- Liber Diurnus, romanorum pontificum, 71, 74, 89, 95, 97, ed. Theodor von Sickel (Vienna: Vindobonae, 1889), 67–68, 74–78, 117–19, 123–25, 127–29.

- Gregory I, Register, 3.22, 41, ed. Norberg, Registrum Epistularum, 167–68, 186.

- Councils of Épaon (517), cc. 7, 12; III Orléans (538), c. 13; V Orléans (549), c. 13; Clichy (626/627), cc. 15, 25, ed. Brigitte Basdevant, Les canons des conciles mérovingiens (VIe–VIIe siècles), 2 vols., Sources Chrétiennes 353–354 (Paris: Éditions du Cerf, 1989), vol. 1, 104, 106; vol. 1, 222; vol. 1, 308; vol. 2, 538, 542.