A reconstruction of separate, conservative, universal elements of the ancient world view is feasible.

By Dr. Nataliia Mykhailova

Scientific Researcher

Institute of Archaeology

National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine

Abstract

Numerous burials of individuals with associated zoomorphic characteristics are known from cemeteries in Europe, dating to the Upper Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic. This paper focuses on burials exhibiting attributes associated with cervids (including red or roe deer antlers, skulls, or bones, and/or elk-headed staffs) from Saint-Germain-la-Rivière, in south-western France; Téviec and Hoëdic, in Brittany; Vedbæk and Skateholm, in Scandinavia; Bad Dürrenberg, in central Europe; Lepenski Vir, Vlasac, Padina, and Haiducka Vodenica, in the lower Danube region; Olenii Ostrov, in northern Russia; Zveinieki, in the Baltic; and Bazaikha, in Siberia. Ethnographic materials relating to the study of Siberian shamanism are employed in the article to help understand the semantic metaphors implied by these attributes. These persons may have been classified as ritual adepts, also known as shamans. ‘Shaman’ activity is connected with transformations: transformation of consciousness, male-female transformation, human-animal transformation. A virtual connection with animals is the basic feature of shamanism, and it can be studied with the help of archaeology.

Introduction

Numerous burial complexes with animal remains have been found in different Stone Age cemeteries in Europe. Some of them were supplemented with red deer or roe deer antlers, skulls, or bones; others were accompanied by elk-headed staffs. I will argue below that these burials are connected with a deer/elk cult.

The deer/elk cult is a myth-ritual complex. The object of worship is a sacred deer, incarnated as a female deity known as Deer-Mother, who is a zoomorphic and, later, zooanthropomorphic ancestor (Anisimov 1958, 104; Simchenko 1976, 270; Popov 1936, 88-89; Potapov 1935, 139; Okladnikov 1950; Jacobson 1993; 2001; Mykhailova 2017a, 57-58). The most important evidence supporting the existence of a deer cult in traditional societies is the totemic mysteries connected with the reproduction of deer and with hunting magic rituals (Bogoraz 1939; Anisimov 1958; Mykhailova 2009; 2016; 2017, 27-44). During those ceremonies, participants dressed as a deer, imitated deer coupling, and then killed and ate the sacral animal and buried its bones and antlers in sacred places for future regenerations of deer (Charnolussky, 1966, 310-311; Kharusin, 1890, 340-383, Mykhailova, 2015). The main participant in these rituals was the shaman (Vasilevich 1957; Anisimov 1958; Mazin 1984; Mykhailova 2017a, 52-57).

The cult of the deer/elk apparently formed during the Upper Palaeolithic and was at its height in the northern Eurasia Mesolithic. It appears most clearly in art. In the Franco-Cantabrian Upper Palaeolithic caves in particular, deer depictions mark semantically important places of ‘The Border of the Worlds’, meaning a liminal zone (Mykhailova 2017b). In the Iberian Peninsula Mesolithic and Neolithic, depictions of deer occupy prominent places in scenes that, I believe, mostly reflect totemic and shamanic myths and/or rituals (Bahn 1989, 558; Varela Gomes 2007; Mykhailova 2017a, 101-115). Some sites have yielded anthropozoomorphic (animal-human conflation) figures with antlers (Dams 1981, 475-494). In the northern Eurasia Neolithic, the deer/elk is one of the predominant depictions in both portable art (Carpelan 1975; Studzitskaya 2004, 251) and rock art (Lahelma 2008, 23; Helskog 1987, 19; 24; Okladnikov 1966, 129; Mykhailova 2017a, 115-156). There are numerous depictions of humans with elk-shaped sticks in northern Eurasia. Some investigators interpret these humans as shamans (Gurina 1956, 202; 206; Ribakov 1981, 62-66; Studzitskaya 2004, 250-251).

Overview of Research about Shamanism

Applied to prehistoric societies, the term shamanism is rather restricted in its meaning. Shamanism is a practice that involves a practitioner reaching ʻaltered states of consciousness’ (see Hoffmann 1998) in order to perceive and interact with a spirit world and channel these transcendental energies into this world (Hoppál 1987). In contemporary traditional societies, shamanism is a developed and complicated institute of consciousness. According to contemporary investigators, the roots of shamanism lie in the Upper Palaeolithic.

The notion of shamanism as an ‘ecstatic technique’ or ‘obsession’ is very popular among investigators of both prehistoric and contemporary societies alike. The creators of the ʻneuropsychological model’, David Lewis-Williams, Jean Clottes, and Thomas Dowson, compare the motifs and stylistic aspects of the Franco-Cantabrian and Levantine rock art with those of San rock art. They suggest that Palaeolithic and Mesolithic paintings reflect a shaman’s visions (Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988, 171-178; Clottes and Lewis-Williams 1996). Some research on Levantine rock art interprets the anthropomorphic depictions with unusual headdresses as shamanistic (Hameau and Painaud 2004; Utrilla and Martinez-Bea 2005). David Whitley (2000) compared the archaeological and rock art evidence for shamanism in western Northern America and the rock art of Southern Africa with the European Upper Palaeolithic rock art. Carolyn Boyd and Kim Cox (2003) studied shamanistic items in North American rock art, especially Lower Pecos ‘shamanic’ rock art in Texas (USA). These authors compared these ancient drawings with the Huicholi mythology. Antti Lahelma (2005; 2008) studied northern European Neolithic rock art depictions in comparison with Saami mythological and ethnographic materials. This author investigated manifestations of the shamanic trance and shamanic metamorphosis in Finnish rock paintings. Knut Helskog (1987) compared the subjects of Scandinavian rock depictions with the images depicted on Saami drums. Ekaterina Devlet (2001) elucidated the X-ray anthropomorphic depictions of northern Asia as images of shamans dismembered during the shamanic initiation. Andrzei Rozwadovski (2012) investigated rock art depictions of the Bronze Age and Iron Age of northern Asia in the context of Siberian shamanism. Esther Jacobson (1993; 2015) interprets the ancient rock depictions of Northern Asia as pre-shamanic. According to Jacobson, ‘shamanism was in some sense a late-comer, the last layer of belief within the deep sedimentation of time’ (Jacobson 2015, 351).

Investigators of the material evidence of ancient shamanism compare archaeological and ethnographic data. Gernot Tromnau has compared evidence of Siberian shamanic practice within the archaeological materials and rock art of Europe. He supposes that the similarity in climatic conditions of the polar and subpolar regions today and Stone Age Europe resulted in the similarity in material and spiritual culture (Tromnau 1991). Joëlle Robert-Lamblin draws parallels between the modern population of north-eastern Siberia and the hunters-gatherers of Upper Palaeolithic Europe; this researcher considers that such a comparison is legitimate because cultural models, despite their diversity, are due to economic patterns and natural factors (Robert-Lamblin 2005, 199-211). Thomas Dowson and Martin Porr interpret the Upper Palaeolithic mobile animal statuettes as evidence of prehistoric shamanism (Dowson and Porr 2004). The British archaeologists Shantal Conneller and Tim Schadla-Hall, and others, studied the deer frontlets from the Mesolithic site of Star Carr (County North Yorkshire, Great Britain) and interpreted these frontlets as shamanic headdress (Conneller and Schadla-Hall 2003). A.M. Serikov (2003) has investigated shaman cemeteries in the Ural (northern Russia) and distinguished some characteristics of the shaman’s grave, among them a deep pit, a sitting position, and weapons.

Although a complete reconstruction of the holistic ancient ideological system seems impossible, a reconstruction of separate, conservative, universal elements of the ancient world view is feasible. According to the famous anthropologist and investigator of the northern Asian spiritual culture A.M. Sagalaev, ʻOnce formulated ideas and images satisfied society during all the period. […] Fundamental ideas of the worldview remained relevant during all cultural genesis’ (Sagalaev 1991, 15).

I propose to consider cemeteries with cervid antlers and zoomorphic artefacts (the signs [знак] of the deer) as relating to ‘shamans’ in a semiotic way. I am aware of the complexity of doing so, since the archaeological record cannot indicate one of the most important shamanistic features, namely, obsession. So, I propose to accent a different shamanistic property, that of the virtual connection with zoomorphic spirits, for which I collected ethnographic evidence from northern Europe to northern Asia. Shamans played the role of the main executors of the most significant and complicated rituals connected with the natural cycles of the deer. Shamans were mediators between the world of the people/living and the world of the spirits/animals/dead. The shaman’s spirit-patrons were zoomorphic beings, and the shaman had ‘consanguineous’ relations with them (Gracheva 1981; Anisimov 1958). In my investigation, I consider only shamans whose major spirit-patron was Deer or Elk. Mostly this spirit-patron was Mother-Animal or Deer-Mother (Jacobson 1993; 2001). Evenkian shamans had virtual contact with Deer-Mother during their shamanic initiation. Deer-Mother virtually ʻswallowed’ the soul of the young shaman and then created a zoomorphic spirit-double of the shaman, her or his spirit-patron (Anisimov 1958, 144). The new status of the shaman was marked by zoomorphic attributes (Anisimov 1958, 144). The shaman’s burial was marked by the antlers of offered deer (Bogoraz 1939, 192; Khomich 1981, 37). In my opinion, the semantically important parts of the deer (the antlers or skull) and the artefacts with deer/elk depictions excavated from Stone Age burials can be considered as the signs of these animal-patrons.

Archaeological Examples from the Upper Palaeolithic and the Mesolithic between the Atlantic and the Pacific

Burials in the Atlantic Region

One of the most ancient ‘shaman’ burials is the Upper Palaeolithic burial known as the Lady of Saint-Germain-la-Rivière (Dép. Gironde, France; 15780 ± 200 BP [GifA 95456]; Vanhaeren and D’Errico 2005, 121). It was attributed to a young adult woman. The stone structure, comprising four blocks, was disturbed, and therefore a reliable reconstruction of the burial structure is not possible. A bison skull and reindeer antlers painted with ochre were found near this stone structure. There was rich grave inventory, including lithic tools, shells, weapons, and animal bones, including a fox mandible. Two ‘antler daggers’ were found near the skeleton. The skeleton was covered with red ochre. A hearth and a certain number of bones were found close to the burial. The most fascinating feature is the 71 red deer canines, perforated and decorated with parallel notches. They must have been obtained through long-distance trade and represented prestige items (Vanhaeren and D’Errico 2005). The stone structure and the inventory of the burial indicate the high status of the buried woman. The painted remains of bison and deer may be the signs of the animal-patrons. The fox mandible appears to be very significant. Mandibles were semantically important parts of the animal body (Mykhailova 2017a, 182). Fox mandibles were also discovered in Epipalaeolithic burials in the Levant. Natufian burials at Ain Mallaha and Hayonim Cave (Southern District, Israel) contain isolated fox mandibles or, more commonly, perforated teeth. In the Neolithic, foxes are common, particularly at the ritual burial site of Kfar HaHoresh (Northern District, Israel), where fox mandibles were found associated with human skulls and partially articulated fox remains are known from two child burials (Maher et al. 2011). According to ethnographic and archaeological materials, animal mandibles were used in rituals aimed at the rebirth of the animals (Mykhailova 2017b, 182).

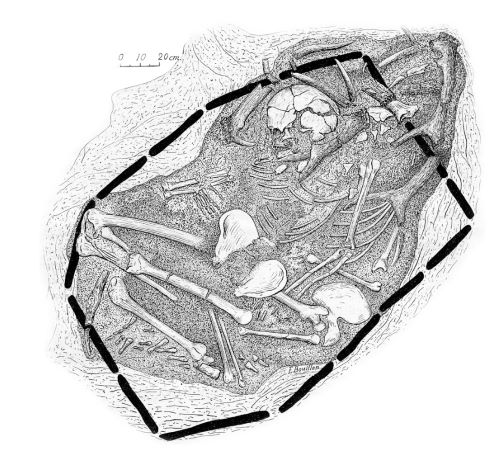

The Late Mesolithic complex at Téviec (Dép. Morbihan, France) comprised a grand total of 10 individual and collective burials in pits covered with stone slabs, along with the remains of ritual fires and offerings (Péquart et al. 1937). Tent-like red deer antler structures are associated with two adult females (grave A; Fig. 1) and one adult female with a child (grave D). There was an unusual richness of grave goods in comparison with the other graves at that site: flint tools, ornament-ed bone points, daggers, a worked boar tusk, perforated red deer teeth, and an abundance of perforated marine shell of various species. The authors of the excavation report concluded that the presence of antlers on top of the burial allows us to assume that the dead people were connected with religious activity (Péquart et al. 1937). Especially ornamented bone pins, used as garment fasteners, and long flint blades were found in the cemeteries with antlers. ‘Tests of association show a relationship between antler structures, flint blades and bone pins….’ (Schulting 1996, 346). ‘An interesting finding is that those graves with antler structures – all adults – have markedly greater artefact richness than those without such structures. Bone garment pins and flint blades, both of which may have been made specifically as grave inclusions, are also associated with significantly higher than average artefact richness’ (Schulting 1996, 349).

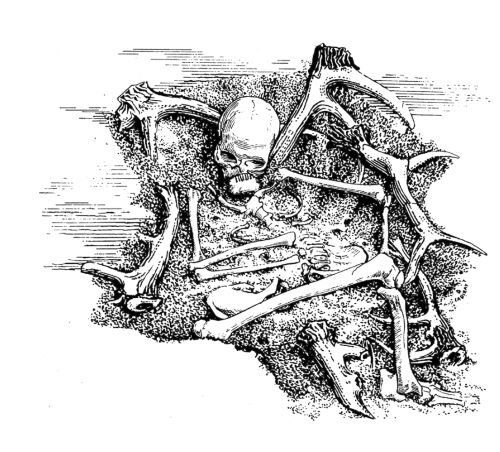

In the Mesolithic burial complex at Hoëdic (Dép. Morbihan, France; 6575+350 BP; Fig. 2), which comprises nine graves, four adults (two males and two females: graves F, H, J, K) were accompanied by shed red deer antlers (Fig. 2; Péquart and Péquart 1954). The two female burials were especially rich. To my mind, the blades and other flint tools in the female burials may testify to certain male activity on the part of the deceased women.

A small test excavation at the contemporaneous site of Beg-er-Vil (Dép. Morbihan, France), located between Téviec and Hoëdic, revealed a pit surmounted by three antlers. There was a bone pin in the pit (Kayser and Bernier 1988, 45). It was probably an attribute of a person of high status. A similar find was made at the Teviec cemetery.

Southern Scandinavia

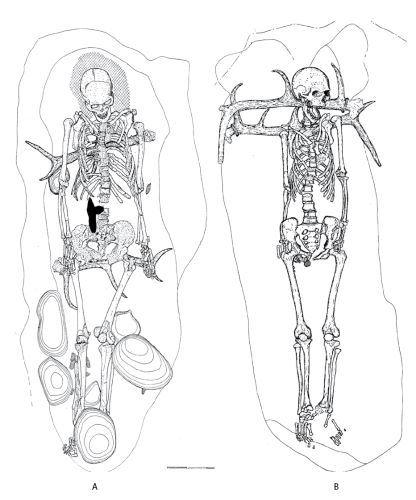

The Mesolithic cemetery at Vedbæk, Henriksholm-Bøgebakken (Rudersdal Kommune, Denmark) belongs to the late Kongemose culture and the early Ertebølle culture (4100 BCE). Twenty-two graves were excavated there. Three of them had deer antlers. The undisturbed grave 10 contained the unusually well-preserved skeleton of a 50-year-old male (Fig. 3A). Two large flint blades were found to the right of and just above the pelvis. The deceased had been laid to rest on a pair of red deer antlers, one placed under the shoulders, the other under the pelvis. Five big stones had been placed on the person’s lower extremities. The skull was surrounded by ochre. There were remains of a wooden structure, probably a boat, around the body. Burials in boats are well known from prehistoric times. The undisturbed grave 11 was of the same type as the other burials. A red deer antler, a bone awl, and a shaft-hole axe were found at the bottom. The floor of the grave was coloured by ochre, but there were no traces of the interred person. The explanation offered by the excavators is that the detailed stratification of the fill suggests that the body was disinterred shortly after burial. The composition of the grave goods suggests that grave 11 originally contained a man.

The undisturbed grave 22 at Vedbæk, Henriksholm-Bøgebakken, contained the well-preserved skeleton of a 40- to 50-year-old female (Fig. 3B). There was no ochre in the grave, but a pair of deer antlers lay below the head and shoulders of the deceased. The antlers were from slain animals. It was noted that the graves containing antlers were the deepest in the cemetery. Grave 10 had stones to weigh down the legs of the deceased (Albertsen and Petersen 1976, 28).

So, the deceased with antlers were old men and women. Antlers marked semantically important parts of the body – the shoulder, pelvis, and head. These burials had some distinguishing features. The graves were deeper, but the grave goods were poorer than in other graves. The deep pits and the stones like in grave 10 indicate that the deceased were people of high status (Mykhailova 2017a, 196).

A woman with a three-year-old child was buried in the Vedbæk-Gøngehusvej 7 burial complex in Denmark (5480-5390 BCE; Schulting 1988). The grave was deep, and the sides of the grave, beginning at the top, had been strewn with ochre. There was bird beak near the head of the woman, probably part of a headdress. There were roe deer phalanges on the torso; possibly the woman had been wrapped in a roe deer skin. Both individuals were accompanied by pendants made from animal teeth, bone and stone pendants, flint and bone knives, a bone hairpin and needles, and an abundance of red ochre.

The Skateholm II site (Trelleborgs kommun, Skåne län), in Sweden, comprises a settlement area and cemetery, both of Late Mesolithic age. Twenty-two graves have been examined at Skateholm II. Grave XI, with a young adult male in a supine position, featured a veritable network of red deer antlers placed transversely across the man’s shins. Two antlers were still attached to a cranial fragment. Grave XV contained a young male placed in a seated position. Two red deer antlers lay by the man’s head, while a further large antler lay by his feet. A row of perforated red deer teeth ran across the top of the cranium – evidently the remains of an elaborate headdress. Two flint blades lay by the hip, and a core axe lay at the left of the thigh. Several teeth of wild boar lay below the right underarm. Grave XX contained a young female in a supine position. A row of perforated tooth beads extended around the waist, including teeth of aurochs. Tooth beads were also found behind the head. A dog was found in a pit behind grave XX, a red deer antler lying along its back. In addition, three flint knives and an ornamented hammer of red deer antler were found on the dog’s stomach. A pit with no traces of a skeleton contained three large deer antlers. This feature has, with some reservation, been interpreted as a cenotaph (Larsson 1989, 373). Grave XXII included a woman seated on deer antlers, accompanied by animal tooth beads and shale a blade (Hansen 2003).

Burials in Central Europe

A Mesolithic burial of a woman with a baby was excavated at Bad Dürrenberg (Saalekr., Germany; 7930+90 BP [OXA-27244], 5625-5490 cal BCE; Grünberg 2016, 17). The body of the woman was in a vertical position; the little baby was between the woman’s hips. The rich inventory includes roe deer antlers, boar tusks, turtle shell, stone and antler axes, the teeth and jaws of animals, shells, and a drilled bone item (probably a musical instrument). The pathology of the cervical spine is said to be an indirect argument for the shamanic interpretation of the burial (Porr 2004, 292-293). The roe deer antlers may have been part of the shaman’s costume (Porr 2004, 299 Fig. 24.14). The tradition of burials with red deer symbolism was continued into the Neolithic, particularly in the burial complexes near the Iron Gates, in the lower Danube region (Budja 2006). The cemeteries at Lepenski Vir, Padina, Vlasach, and Gayduchca Vodenitsa (all Borsky okrug, Serbia) include trapezoidal limestone structures with rectangular hearths and sculptured boulders with fish-human features. Skulls of red deer were founded near several skeletons, of men, women, and children (Budja 2006).

Burials in the Eastern Mediterranean

The use of antlers to signify deer is known from the Near East as well, for example, from the Uyun al-Hammam cemetery (Irbid Governorate, Jordan), dated to the Epipalaeolithic (17,250-16,350 cal BP and 15,000-14,200 cal BP; Maher et al. 2011). ‘Two adjacent graves contain the articulated remains of several individuals and include the following elements: 1) the earliest human-fox burial, 2) the movement of human and animal (fox) body parts between grave, and 3) the presence of red ochre, worked bone implements, chipped and ground stone tools, and the remains of deer, gazelle, aurochs, and tortoise’ (Maher et al. 2011, 2). ‘A nearly complete fox skeleton, missing its skull and right humerus, was discovered in Grave VIII, adjacent to a bone “spoon”, red deer antler, several large flint blades and flakes, and several flat, unmodified cobbles’ (Maher et al. 2011, 4). Spoons, as an implement for eating ritual meals, had high semantic status in northern Eurasia in historical times, where they often served as attributes of priests (Mykhailova 2017, 151).

The so-called shaman’s burial from the Upper Palaeolithic cave site of Hilazon Tachtit (Northern District, Israel), in the southern Levant, should also be mentioned. The grave was constructed and specifically arranged for an elderly disabled woman, who was accompanied by exceptional grave offerings. The grave goods comprised 50 complete tortoise shells and selected body parts of a wild boar, an eagle, a cow, a leopard, and two martens, as well as a complete human foot (Grosman et al. 2008). In my opinion, the zoomorphic features of the cemetery, especially the eagle wing and the cow’s tail, undoubtedly indicate a connection between the buried woman and animal-patrons.

Rock Carvings and Burials in Northeastern Europe and Siberia

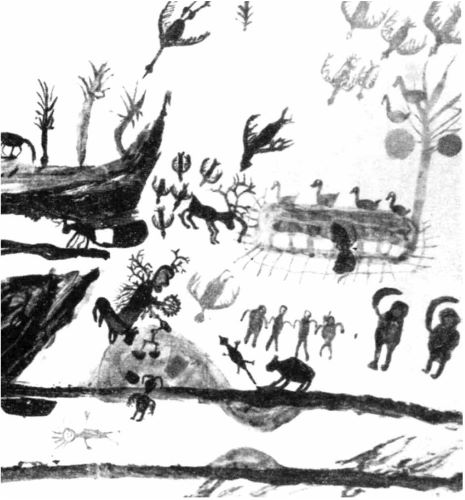

The elk became the main traded animal in northern Eurasia in Neolithic times. Numerous staffs with one end shaped like a female elk’s head have been found, from Denmark to the Far East (Carpelan 1975). There are numerous depictions of humans with elk-headed staffs in northern European rock art (Ravdonikas 1936). Sometimes these people were depicted in elk-headed boats (Lahelma 2005; Mykhailova 2017a, 136). Some scholars have compared them with rock carvings found in northern Europe of people with emphasised sexual attributes and holding zoomorphic objects (Helskog 1987, 24-25), such as at Alta (Fínnmark county, Norway), Zalavruga (Karelia Republic, Russia), Peri Nos (Karelia Republic, Russia), and Namforsen (Sollefteå kommun, Sweden). Some of them are dancing or conducting ritual activity.

Many burials of people with elk-headed staffs are known from northern Eurasia. The most famous is the Mesolithic burial (55-56-57) of a man and two women on Oleniy Island, in Lake Onega (Karelia Republic; end of 7th century-beginning of 6th century BCE; Fig. 4B; Gurina 1956). The skeletons were buried in the same pit, under a single stone covered with red ochre. They were accompanied by numerous elk teeth, bones of animals, and a snake figurine. The richest was the male burial (56). It had an elk-headed staff near the head (Gurina 1956, 202; 204). The women do not look like victims. It seems that they had equal rights to men (Khlobystina 1993). Another six burials had the same kind of staff (Fig. 4A; Gurina 1956, 203). The staff probably became an incarnation of the elk-patron, most likely Great Elk-Mother (Mykhailova 2017, 205).

The Mesolithic burial complex at Zveinieki (Tukuma District, Latvia) is the richest in Europe (Zagorska 1998). Grave 57 (6825 ± 60 BP [Ua-3636]), of a female, was deep, and the sides of the grave had been strewn with ochre. A thick layer of ochre surrounded the skeleton. The grave goods consisted of a stone axe, flint artefacts, and animal tooth pendants (elk, red deer, and aurochs). This individual had been provided with a bone spearhead and an elk-headed staff. Her grave was the richest female grave in the entire cemetery, confirming the special role of this person in the Late Mesolithic community. The stone axe and flint artefacts look like male inventory.

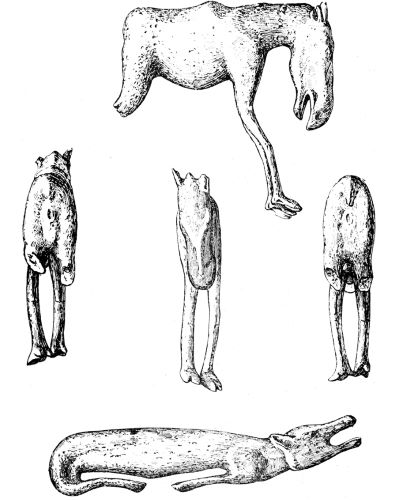

The Neolithic burial at Bazaikha (Irkutsk District, Russia) belongs to the Serovo culture of Siberia (6th-3rd century BCE). An elk-like staff and four realistic figurines of elks shown during their mating ritual were found near the male skeleton (Fig. 5). A zooanthropomorphic figurine was found in the cemetery as well (Okladnikov 1950, 280-283).

Ethnographic Evidence from Siberia

Overview

The Soviet ethnographers A. D. Anisimov (1958), G. M. Vasilevich (1957), A. A. Popov (1936), U. H. Popova (1981), E. D. Prokofieva (1959), L. P. Potapov (1934), Y. S. Vdovin (1981), A. I. Mazin (1984), and others have gathered and published unique materials from the 19th and 20th centuries CE relating to Siberian shamanism, which can serve as a source for many generations of researchers.

In the ideological system of the indigenous peoples, shamans played the role of mediators between the world of humans and the world of the spirits. According to Evenkian mythology, the giant Elk-Female, Bugady-Eninteen, was the mother of the animals and hostess of the forest. Her image was portrayed on the sacral Bugady rocks (Evenkia District, Russia), dating from the Neolithic (Okladnikov 1950, 317; Anisimov 1958, 104). The shaman had a virtual connection with the Great Mother during shamanistic sessions. This ‘relationship’ was reflected in the shaman’s attributes.

Ethnographic Materials

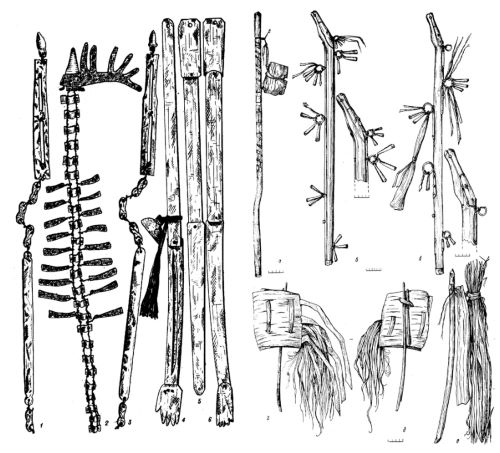

The coat of the Evenkian shaman was made of deer hide, and it had small iron antlers on the shoulders – a very important element of a costume. Initially, real antlers were used. When the shaman danced, the antlers rose over the shaman’s head (Fig. 6; Alexeenko 1981, 106; Potapov 1935; Mazin 1984, 66).

The most important feature of the shaman’s costume was a headdress with antlers − a symbol of the shaman’s power and strength (Fig. 7). By putting on this crown, the shaman acquired the mystical qualities of a heavenly deer (Potapov 1935; Anisimov 1958, 179) (Fig. 7).

The embodiment of the deer-ancestor or spirit-helper of the shaman was a tambourine − the most important attribute of a shaman, made from the sacred deer’s skin. The shaman was ‘reincarnated’ in this deer during the initiation ceremony (Potapov 1947, 163-172). In South America, Huicholi shamans also used a drum made from the divine skin (Fig. 8; Furst 1977, 11).

Shamans initially used the bow and arrow for musical accompaniment. Later, the tambourine replaced the functions of a bow and got given the same name. Siberian shamans used the model of the bow as an accessory on their parkas (Potapov 1934, 64-77; Anisimov 1958, 26-35). The Huicholi used a bow for ‘charming’ game (Furst 1977, 11).

Gender Roles of Shamans

Women as well as men could be shamans in the hunting societies of Siberia. Female shamans were engaged in ‘domestic’ forms of shamanism, and sometimes they were more skilled in shamanic practice than men. The Chukchi believed that a female shaman could influence the success of the hunt just as well as a male hunter could (Bogoraz 1939). Many folkloric, written, linguistic, and archaeological data testify to these female shamans’ high social status (Sorokina 2005). The costume of the female shaman was more richly ornamented, and this is argued to be evidence that women need more protection against spirits (Sorokina 2005).

Transvestism was common among shamans in various Siberian cultures. So-called ‘soft men’ sometimes changed their appearance, clothes, and pendants. Their attributes were not weapons but needles and scrapers (Bogoraz 1939). Sometimes there was a hormonal change in the body. The transformation began\shaman. ‘Soft man’ lost his male power, legerity, hardiness, and courage; he became helpless, like a woman. Such shamans even ‘married’ men. These ‘transformed’ specialists were very skilful in their shamanistic activities (Bogoraz 1939; Torchinov 2005, 123-143).

Sometimes female shamans cut their hair, changed their clothes, and learned to use a spear and a gun. But such cases were rare (Bogoras 1939).

Among North American indigenous peoples, there is strong tradition of male transvestism, called two-spirits (berdaches). When two-spirits (berdaches) became shamans, they were regarded as exceptionally powerful (Vitebsky 1995, 93).

Vladimir Bogoraz thought that shaman transvestism was a remnant of early shamanism, when its ‘female’ element prevailed (Bogoraz 1910). This statement can be confirmed with the archaeological materials.

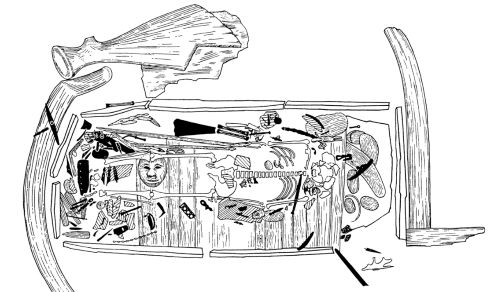

Some female burials of the Stone Age of Europe had flint tools (Teviec, Hoedic, Zveinieki) or stone and bone axes (Bad-Dürrenberg), which can be defined as male. I propose to compare them with the cemetery in the Far East. Different materials were discovered in the female shaman cemetery of Ekven (Fig. 9; Chukotka autonomous okrug, Russia). It is one of the important sites of the Old Bering Sea culture, which existed from 400 BCE to possibly as late as 1300 CE (Ackerman 1984; Arutiunov and Sergeev 2006). In burial 145, the body was surrounded by large bones of a whale – it was ‘inside’ the whale symbolically. The skeleton was lying face down. The rich burial inventory is associated with woman’s activity and sacral practice (scrapers, pottery paddles, knives, a walrus ivory chain, wooden dance goggles, drum handles, and a wooden anthropomorphic mask), but also with men’s activity, as evidenced by a number of tools, including lance points and harpoons. So, the woman performed the functions of a male shaman (Tromnau and Loffler 1991).

Buried Shamans in Historic Times

Death is the transition to the Other’s world – the world of the dead and the animals. A person acquires zoomorphic features after death (Petrukhin 1986, с. 11). This idea of acquiring zoomorphic features is well reflected in the materials in the female shaman cemetery of Ekven (Fig. 9), mentioned above.

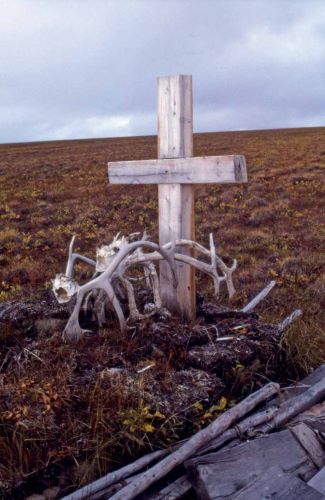

Siberian shaman’s graves were marked by deer antlers, as is documented by single burials erected in modern times in the Siberian landscape, separated from the usual cemeteries (Fig. 10). An eyewitness described a Siberian shaman’s grave as follows: ‘It is low chest made of boards, strengthening by six stakes. The cross-beams are decorated with nice branchy antlers of wild deer, as a symbol of last funeral repast, as an offering. The chest was covered by red cloth. The stones are lying on the cloth, to hold from the storm. There is the opened sacral shaman’s box behind […]’ (Khomich 1981, 37).

According to Vladimir Bogoraz, ‘Giant antler storages were grown on the Big Men or shaman’s burials. On the great island Ayon the ancient fence, made from antlers, situated. It was connected with the name of “Qeeqe”, female shaman, which was buried there’ (Fig. 11; Bogoraz 1939, 192).

Indigenous peoples believe that shamans receive very independent additional power after death. Tribes people disfigured their bodies to protect against these powers: they put the bodies in an unusual position or put stones or weapons on the body (Kosarev 2000, 534, Serikov 2003, 141-164; Chernetsov 1959, 144). Investigators of Siberian shamanism have distinguished some common features of shaman’s cemeteries: burials in caves or under stone slabs; unusual positioning of the deceased (e.g. sitting); deep pits; dismemberment; and bones of animals, birds or fishes as a detail of the costume (Serikov 2003). There was a custom among indige-nous peoples to exhume dead bodies of sorcerers and other dangerous diseased and to bury them in another place, or to drown them in water (Varavina 2008).

Conclusions

Reconstructing the phenomena of the primeval worldview is an enormously complicated task. For a complete understanding of the archaeological objects as elements of the primordial mytho-ritual complex, extensive use of ethnographic analogy is necessary.

Numerous burials with associated zoomorphic characteristics discovered in Europe dating to the Upper Palaeolithic, Mesolithic, and Neolithic may be interpret-ed as burials of ritual executors or shamans. The zoomorphic features may relate to the existence of a virtual connection between the buried person and a deer/elk-like patron or ancestor (Animal Mother). The burials that have Cervidae (deer and elk) elements associated with them are of men as well as women. In many cases, the graves of females have the same inventory as those of males. Sometimes, however, the grave offerings can be far more extensive, indicating that the deceased were more dependent on the animal-patron. The Upper Palaeolithic burial at Saint-Germain-la-Rivière was supplemented by spectacularly abundant adornment, made from red deer teeth. Two ‘antler daggers’ are reminiscent of the ‘beaters’ of the northern shamans. Similar items have been found in many Upper Palaeolithic sites of Europe (Mykhailova 2017a, 163). A fox jaw was an outstanding attribute of the Lady of Saint-Germain-la-Rivière cemetery. As noted above, fox mandibles were also discovered in Epipalaeolithic burials in the Levant. Animals mandibles, as important attribute of the rituals of the rebirth of the animals, are found in numerous burial complexes and offering places of ancient and historical times in both Europe and Asia (Mykhailova 2017b, 182).

Especially rich female burials, covered with antlers, come from the Téviec and Hoëdic Mesolithic burial complexes. I assume that certain features of cemeteries with antlers demonstrate that they may be ‘shaman’s’ graves. The unusual richness of grave goods (in comparison to those of other graves of both complexes) looks like a feature of ‘shaman’ burials.

In the Mesolithic funerary complex at Vedbæk, Henriksholm-Bøgebakken, the deceased, laid on deer antlers, also have the features of ‘shamans’. In the Skateholm II Mesolithic burial complex, two female graves were accompanied by deer antlers and richly ornamented with beads made from animal teeth. The deceased have the features of a shaman − seated position and headdresses with deer teeth.

Especially prominent were cemeteries of women with young children. Burial D at Téviec was accompanied by abundant adornments. In the Vedbæk-Gøngehusvej Mesolithic cemetery, the grave of a woman with a six-month-old child was richly ornamented. The most fascinating is the Mesolithic burial at Bad Dürrenberg, of a woman with a baby. The rich grave inventory, which includes a wide variety of flint, bone, and stone tools, allows us to characterise the inventory as being both male and female.

I would argue that these outstanding findings are comparable to those from the so-called shaman’s burial from the Upper Palaeolithic cave site of Hilazon Tachtit, in the southern Levant, where the zoomorphic features mentioned above indicate a connection between the buried woman and animal-patrons.

Cemeteries with elk-headed staffs, as the signs of the Elk-Mother, are widespread in northern Europe and northern Asia in Mesolithic and Neolithic times. The staff probably became an incarnation of an elk-totem, the sacral animal-ancestor. People with elk-shaped staffs were probably shamans who had had virtual relations with the Great Elk-Mother. Elk-headed staffs look like the horse-headed shaman’s sticks of the Yakuts (Fig. 6; Diakonova 1981). The grave of the old woman with the elk-head-ed staff from the Mesolithic complex at Zveinieki was the richest of all contemporaneous burials in Europe. The stone axe and flint artefacts look like male inventory.

Based on the deer/elk symbolism in these burials, we may assume that in the hunter-gatherer societies of the Stone Age women occupied an outstanding place in sacred practice.

We can summarize that Stone Age burials with the signs of the deer can be the evidence of shamanic transformations. Buried persons had a virtual connection with the Deer Patron or Ancestor (Great Mother), and, during shamanic mysteries, ‘transformed’ into the sacral Deer for the ‘journey’ to the supernatural world. Given that women played a great role in primeval ritual activity, many of the deceased with the signs of the deer were female. Simultaneously, some of the buried women had both female and male inventory. They probably had ‘fluid’ gender or ‘changed’ their gender role during shamanic séances.

References

- Ackerman, Robert 1984. Prehistory of the Asian Eskimo zone. In: Damas, David, and Sturtevant, William V. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians 5. The Arctic. Washington: Smithsonian Institution, 106-118.

- Albertsen, Svend, and Petersen, Erik 1976. Excavation of a Mesolithic cemetery at Vedbæk. Acta Archaeologica, 47, 1, 1-28.

- Anisimov, Arkadij F. 1958. Religija Evenkov V Istoriko-genetičeskom Izučenii I Problemy Proischoždenija Pervobytnych Verovanij. Moskva, Leningrad: Akademija Nauk SSSR, Inst. Archeologii, Leningrad.

- Arutiunov, Sergei A., and Sergeev, Dorian A. 2006. Ancient Cultures of the Asiatic Eskimos: The Uelen Cemetery. Anchorage: Shared Beringian Heritage Program.

- Bahn, Paul 1989. The early postglacial period in the Pyrenees: some recent work. In: Bonsall, Clive (ed.). The Mesolithic in Europe. Papers presented at the third International Symposium, Edinburg 1985. Edinburgh: John Donald, 556-560.

- Bogoraz, Vladimir 1910. The Chuckchee mytology. Publication of the Jesup North Oacific Expedition 8,1. Leiden.

- Bogoraz, Vladimir 1939. Chukchi. Leningrad: Izdatelstvo Hlavsevmorputi.

- Boyd, Carolyn, and Cox, Kim 2013. La peinture rupestre du Chaman blanc. Dossiers d’archeologie, 358, 72-76.

- Budja, Mihael 2006. The transition to farming and the ceramic trajectories in Western Eurasia: from ceramic figurines to vessels. Dokumenta Praehistorica, 33, 183-201.

- Carpelan, C. 1975. Alg-och björnhuvudföremål från Europas nordliga delar. Finkst museum, 82, 5-67.

- Chernetsov, Valerij N. 1959. Predstavleniia o dushe u obskich ugrov. Trudy Instituta etnografii AN SSSR, 51, 114-156.

- Clottes, Jean, and Lewis-Williams, David 1996. Les chamanes de la préhistoire: transe et magie dans les grottes ornées. Paris: Seuil.

- Conneller, Chantal, and Schadla-Hall, Tim. 2003. Beyond Star Carr: The Vale of Pickering in the 10th millenium BP. Proceedings of the Prehistoric societies, 69, 85-105.

- Dams, Lya 1981. La Roche peinte dÁlgodonales (Cadiz). In: Altamira Symposium. actas del symposium internacional sobre arte prehistórico celebrado en conmem-oración del primer centenario del descubrimiento de las pinturas de Altamira (1879-1979), Madrid 1979. Madrid: Ministerio de Cultura, Subdirección General de Arqueología, 475-494.

- Devlet, Ekaterina 2001. Rock art and the material culture of Siberian and Central Asian shamanism. In: Price, Neil S. (ed.). The Archaeology of Shamanism. New York: Routledge, 43-55.

- Diakonova, Vera P. 1981. Predmety k lechebnoi funktsii shamanov Tuvy i Altaia. In: Boris Putilov (ed.). Materialnaia kultura i myfolohiia Soobcheniia Muzeya Archeologii i Etnographii, 37. Leningrad: Nauka, 138-153.

- Dowson, Thomas, and Porr, Martin 2004. Special objects – special creatures: Shamanistic imagery and the Aurignacian art of south-west Germany. In: Price, Neil S. (ed.). The Archaeology of Shamanism. New York: Routledge, 165-178.

- Furst, Peter T. 1977. The roots and continuities of shamanism. In: Trueblood Brodzky, Anne, Danesewich, Rose, and Johnson, Nick (eds). Stones, bones and skins. Ritual and Shamanic art. Toronto: Society of Art, 1-28.

- Gracheva, Galina N. 1981. Shamany u nganasan. In: Vdovon, I. S. (ed.). Problemy istorii obshchestvennoho soznaniia aboryhenov Sibiri (po materialam vtoroy poloviny XIX – nachala XXV). Leningrad: Nauka, 69-90.

- Grosman, Leore, Munro, Natalie D., and Belfer-Cohen, Anna 2008. A 12,000-year-old Shaman burial from the southern Levant (Israel). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105, 17665-17669. <www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2584673/>.

- Grünberg, Judith 2016. Remains of the mortuary rituals of upright seated individuals in central Germany. In: Meller, Harald., Grünberg, Judith M., Gramsch, Bernhard, Larsson, Lars, and Orschiedt, Jörg (eds). Mesolithic Burials: Rites, Symbols and Social Organisation of Early Postglacial Communities: International Conference Halle (Saale), Germany, 18th-21th September 2013. Halle (Saale): Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt, 18-21.

- Gurina, Nina N. 1956. Oleneostrovskij Mogil’nik. Materialy I Issledovanija Po Archeologii SSSR 47. Moskva: Izdatel’stvo Akademii Nauk SSSR.

- Hameau, Philippe, and Painaud, Albert 2004. L’expression schématique en Aragon présentation et recherches récentes. L’Anthropologie, 108, 5, 617-651.

- Hansen, Keld 2003. Preboreal elk bones from Lungby Mose. In: Larsson, Lars, Kindgren, H., Knutsson, K., Loeffler, D., and Akerlunci, A. (eds). Mesolithic on the Move. Papers presented at the Sixth International Conference on the Mesolithic in Europe, Stockholm 2000. Oxford: Oxbow, 521-526.

- Helskog, Knut 1987. Selective depictions. A study of 3,500 years of rock carvings from Arctic Norway and their relationship to the Sami drums. In: Hodder, Ian (ed.). Archaeology as long-term history. New directions in archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 17-31.

- Hoffman, Kay 1998. The Trance Workbook: Understanding and Using the Power of Altered States. New York: Sterling.

- Hoppál, Mihály 1987. An Archaic and/or Recent System of Beliefs. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House.

- Ivanov, S. V. 1954. Materialyi po izobrazitelnomu iskusstvu narodov Sibiri HIH – nachala HH v. Syuzhetnyiy risunok i drugie vidyi izobrazheniy na ploskosti. Trudy Instituta Etnografii, Novaya seriya 22. Moskva, Leningrad: Izdatelstvo AN SSSR.

- Jacobson, Esther 2001. Shamans, shamanism and anthropomorphizing imagery in prehistoric rock art of the Mongolian Altay. In: Francfort, Henri-Paul, and Hamayon, Roberte (eds). The concept of shamanism: Uses and abuses. Bibliotheca Shamanistica 10. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó, 277-294.

- Jacobson-Tepfer, Esther. 2015. The Hunter, the Stag, and the Mother of Animals. Image, Monument, and Landscape in Ancient North Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kayser, Olivier, and Bernier, Gildas 1988. Nouveaux objects decors du mesolithic Armoricain. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique de France, 85, 45-47.

- Khlobystina, Maria. D. 1993. Problema sociogeneza kultur severnoy Evrasii v neo-lite-paleometalle. AD Polus. Archeologicheskiie isyskaniia, 10, 69-74.

- Khomich, Lulmila. V. 1981. Shamany u nentsev. In: Innokentiy, Vdovin (ed.). Problemy istorii obschestvennogo soznaniia aborigenov Sibiri. Leningrad: Nauka, 5-41.

- Kosarev, Michail F. 2000. Priobscheniie k nesemnym sferam v sibirskom yasychestve. In: Akimova, Ludmila, and Kifishin, Anatoliy (eds). Zertvoprinosheniie. Moskva: Yazyki russkoy kultury, 42-53.

- Lahelma, Antti 2005. The boat as a symbol in Finnish rock art. In: Devlet, Ekaterina, and Dėvlet, Marianna A. (eds). Mify v kamne: mir naskal’nogo iskusstva v Rossii. Ėtnokul’turnoe vzaimodeĭstvie narodov Evrazii. Moskva: Aleteĭa, 359-363.

- Lahelma, Antti. 2008. A Touch of Red: Archaeological and Ethnographic Approaches to Interpreting Finnish Rock Paintings. Iskos 15. Helsinki: Finnish Antiquarian Society.

- Larsson, Lars 1989. Late Mesolithic settlements and cemeteries at Skateholm, Southern Sweden. In: Bonsall, Clive (ed.). The Mesolithic in Europe. Papers presented at the third International Symposium, Edinburg 1985. Edinburgh: John Donald, 367-378.

- Lewis-Williams, David, and Dowson, T. 1988. The signs of all times: entoptic phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic art. Current Anthropology, 29, 2, 21-45.

- Maher, Lisa, Stock Jay, Finney Sarah, Heywood James, Miracle Preston, and Banning Edward 2011. Unique Human-Fox Burial from a Pre-Natufian Cemetery in the Levant (Jordan). PLoS ONE, 6, 1. Article e15815. doi: <10.1371/journal.pone.0015815>.

- Mazin, Anatolij I., and Derevjanko, Anatolij 1984. Tradicionnye verovanija i obrjady ėvenkov-oročonov: konec XIX – načalo XXV. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Mykhailova, Nataliia. 2009. Obryadovyi aspect kulta olenia po materialam arche-ologicheskikh pamiatnikov Evrazii. In: Vasilev, Sergei, and Kulakovska, Larisa (eds). S. N. Bibikov I pervobytnaya archeologiia. Sankt-Peterburg: IIMK RAN, 269-276.

- Mykhailova, Nataliia 2016. Deer offerings in the archaeology and art of Prehistoric Eurasia. Expression, 10, 53-59.

- Mykhailova, Nataliia 2017a. Cult olenya u starodavnokh myslyvtsiv Evropy ta Pivnich-noi Asii. Kyiv: Stylos.

- Mykhailova, Nataliia 2017b. Cult sites and art. Images of the deer and cult places of Europe and Northern Asia. Expression, 17, 37-48.

- Okladnikov, Aleksej P. 1950. Neolit i bronzovyi vek Pribaikal’ia: istoriko-arkheolog-icheskoe issledovanie. Materialy i issledovaniia po arkheologii SSSR 18. Moskva, Leningrad: Izd-vo Akademii nauk SSSR.

- Okladnikov, Aleksej P. 1966. Petroglify Angary. Moskva, Leningrad: Nauka.

- Péquart, Marthe, Boule, Marcellin, and Péquart, Saint-Just 1937. Téviec: Station-nécro-pole Mésolithique Du Morbihan. Archives de l’Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, Mémoire 18. Paris: Masson et Cie.

- Péquart, Marthe, and Péquart, Saint-Just 1954. Hoëdic: Deuxième station-nécropole du Mésolithique côtier armoricain. Anvers: De Sikkel.Petrukhin, Vladimir 1986. Chelovek i zivotnoe v mife i rituale. In: Zhukovskaia, Nataliia (ed.). Mify, culty, obryady narodov zarubeznoy Asii. Moskva: Arthaaintustarseline.

- Popov, Andrej A. 1936. Tavgiytsy [The Tavgi]. Trudy Instituta Antropologii 1, 5. Moskva, Leningrad: Izdatelstvo Akademii Nauk SSSR.

- Popova, Uliana H. 1981. Perezhitki shamanizma u evenov. In: Vdovin, I. S. (ed.). Problemy istorii obshchestvennoho soznaniia aboryhenov Sibiri (po materialam vtoroy poloviny XIX – nachala XXV). Leningrad: Nauka, 233-253.

- Porr, Martin 2004. Grenzgängerin. Die Befunde des mesoltihischen Grabes von Bad Dürrenberg. In: Meller, Harald (ed.). Paläolithikum und Mesolithikum. Kataloge zur Dauerausstellung im Landesmuseum für Vorgeschichte Halle 1. Halle (Saale): Landesamt für Denkmalpflege und Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt Halle (Saale), 291-300.

- Potapov, Leonid P. 1934. Luk I strela v shamanstve u altaytsev. Sovetskaya etnografiia, 3, 64-76.

- Potapov, Leonid P. 1935. Sledy totemisticheskykh predstavleniy u altaytsev. Sovetskaya etnografiia, 4-5, 130-137.

- Potapov, Leonid P. 1947. Obryad ozivleniia shamanskogo bubna u tyutkoyasychnikh plemen Altaya. Trudy Instituta etnografii AN SSSR, 1, 139-183.

- Prokofieva, Ekaterina D. 1959. Kostium selkupskoho shamana. Sobranijach Muzeia Archeologii i Etnografii, 11, 335-372.

- Ravdonikas, Vladislav I. 1936. Naskal’nye izobrazenija Onezskogo ozera i Belogo Morja [Les gravures rupestres des bords du lac Onéga et de la mer Blanche]. Trudy Instituta antropologii, arkheologii i etnografii 9. Moskva, Leningrad: Izdatelstvo Akademii nauk SSSR.

- Ribakov, Boris A. 1981. Jazyčestvo drevnich slavjan. Moskva: Nauka.

- Robert-Lamblin, Joëlle 2005. La symbolique de la grotte Chauvet à Vallon-Pont-d’Arc sous le regard de l’anthropologie. In: Geneste, Jean-Michel (ed.). La grotte Chauvet à Vallon-Pont-d’Arc. Un bilan des recherches pluridisciplinaires. Actes de la séance de la Société préhistorique française, 11 et 12 octobre 2003, Lyon. Traveaux (Société préhistorique française) 6. Paris: Société préhistorique française, 199-210.

- Rozwadovski Andrzei, 2012. Shamanism, rock art and history: Implications from a Central Asian case study. In: Smith, Benjamin W., Helskog, Knut, and Morris, David (eds). Working with rock art: recording, presenting and understanding rock art using indigenous knowledge. RARI monographs 4. Johannesburg: Wits Univer-sity Press, 192-204.

- Sagalaev, Andrej M. 1991. Uralo-Altayskaya mifologija. Novosibirsk: Nauka.

- Schulting, Rick 1988. Creativity’s coffin. Innovation in the burial record of Mesolithic Europe. In: Mithen, Steven (ed.). Creativity in human evolution and prehistory. Theoretical Archaeological Group. London: Routledge. 203-226.

- Schulting, Rick 1996. Antlers, bone pins and flint blades: The Mesolithic cemeteries of Téviec and Hoedic, Brittany. Antiquity, 70, 335-350.

- Serikov, Jurij B. 2003. Shamanskiie pohrebeniia kamennoho veka. In: Ėtnografo-ark-heologicheskie kompleksy: Problemy kul’tury i sotsiuma 6. Novosibirsk: Nauka, 141-164.

- Sorokina, Sophiia A. 2005 Gendernye aspekty traditsionnoy kultury narodov severa, sibiri I dalnego vostoka. PhD-thesis, University St Peterburg. <cheloveknauka.com/gendernye-aspekty-traditsionnoy-kultury-narodov-severa-sibiri-i-dalnego-vostoka#ixzz5QQA2ZkGN>, retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Studzitskaya, Svetlana V. 2004. Izobrazheniie losia v melkoi plastike lesnoi Yevrazii (epoha neolita i rannei bronzy). In: Savinov, D.G. (ed.). Izobrazitelnyie pamyatni-ki. Styl, epokha, kompozytsyia. St Petersburg: Istoricheskii fakultet St Petersburg, 25-31.

- Torchinov, Evgeny A. 2005. Religii mira: opyt zapredelʹnogo: psikhotekhnika i transper-sonalʹnye sostoianiia. St Peterburg: Centr Peterburgskoe Vostokovedenie.

- Tromnau, Gernot. 1991. Archäologische Funde und Befunde zum Schamanismus. In: Tromnau, Gernot, and Loffler, Ruth (eds). Schamanen. Mittler zwischen Menschen und Geistern. Duisburger Akzente 15. Duisburg: Kultur- und Stadthistorisches Museum.

- Utrilla Pilar Miranda, Maria del, and Martinez-Bea, Manuel. 2005. La captura del ciervo vivo en el arte prehistoric. munibe Antropologia – Arkeologia, 57, 161-178.

- Vanhaeren Marian, and D’Errico, Francesco 2000. Grave goods from the Saint-Germain-la Riviere burial. Evidence for social inequality in the Upper Palaeolithic. Journal of Anthropological archaeology, 24, 117-134.

- Varavina, Galina. N. 2008. Pogrebeniia shamanov u evenov Yakutii. In: The way to Siberia.<//archive.li/QmXB4>, retrieved 22 June 2015.

- Varela Gomes, Mario. 2007. Os períodos iniciais da arte do Vale do Tejo (Paleolítico e Epipaleolítico). Cuadernos de arte rupestre. Revista digital de Arte Rupestre, 4, 81-117. <www.cuadernosdearterupestre.es/arterupestre/4/81_116.pdf>, e-published 2007; retrieved 23 March 2019.

- Vasilevich, G. M. 1957. Drevnie ohotnichi I olenevodcheskie obryady evenkov. Sbornik museya antropologii i etnografii, 17, 151-185.

- Vdovin, I. S. 1981. Chukotskiie shamany i ih sotsialnyie funktsii. In: Vdovin, I. S. (ed.). Problemy istorii obščestvennogo soznanija aborigenov Sibiri (po materialam vtoroj poloviny XIX-načala XXV.). Leningrad: Nauka, 178-217.

- Vitebsky, Piers 2001. Shamanism. Norman: Oklahoma Press.

- Zagorska, Ilga 1988. The art from Zveinieki burial ground, Latvia. In: Butrinas, Adomas (ed.). Prehistoric art in the Baltic region. Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis 20. Vilnius: Vilnius Academy of Fine Arts, 79-92.

- Zagorska, Ilga 2008. The Use of Ochre in Stone Age Burials of the East Baltic. In: Fahlander, Fredrik, and Oestigaard, Terje (eds). The Materiality of Death: Bodies, Burials, Beliefs. BAR International Series 1768. Oxford: Archaeopress, 115-124.

Chapter 2.4.1 (341-362) from Gender Transformations in Prehistoric and Archaic Societies, edited by Julia Katharina Koch and Wiebke Kirleis (Sidestone Press, 01.07.2020), published by OAPEN under the terms of an Open Access license.