The Civil War severely tested the established patterns of civil–military relations.

By Dr. Charles A. Stevenson

Adjunct Lecturer in American Foreign Policy

Nitze School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS)

Johns Hopkins University

Introduction

The particulars of your plans I neither know or seek to know. You are vigilant and self-reliant; and, pleased with this, I wish not to obtrude any constraints or restraints upon you.

Abraham Lincoln to Lt. Gen U.S. Grant, April 30, 18641

I can’t tell you how disgusted I am becoming with these wretched politicians; they are the most despicable of men … The Presdt [sic] is nothing more than a well meaning baboon.

General George McClellan2

I have done everything in my power here to separate military appointments and commands from politics … but the task is hopeless.

General-in-Chief Henry Halleck3

[Army officers who] indulge in the sport [of politics] must risk being gored. They can not, having exposed themselves, claim the procedural protections and immunities of the military profession.

Secretary of War Stanton to Lincoln, January 18634

There must be something in these terrible reports, but I distrust Congressional committees. They exaggerate.

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles5

We are here armed with the whole power of both houses of Congress. They have made it our duty to inquire into the whole conduct of the war; into every department of it. We do not want to do anything that will result in harm or wrong. But we do want to know, and we must know if we can, what is to be done, for the country is in jeopardy.

Senator Benjamin Wade, Chairman of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War6

The top item on Abraham Lincoln’s desk when he entered the White House the morning after his swearing-in was a letter from the Union commander at Fort Sumter reporting that his dwindling supplies would last only another six weeks and expressing his professional opinion that only reinforcement by at least 20,000 men could save the fort. The new president promptly asked his civilian and military advisers what they thought should and could be done.7

Lincoln was then buffeted with conflicting advice on how to save the Union and whether to try to defend the fort in Charleston harbor. Radical anti-slavery members of his own Republican Party pressured him to assert control over federal facilities in the seceding southern states while his new Secretary of State was in secret talks with representatives from those rebellious areas. Navy officials recommended re-supplying and strengthening Fort Sumter, but army leaders considered it indefensible. Instead, they favored a mission to Fort Pickens in Florida, the only other major federal outpost in the south still in Union control. The cabinet was 5–2 against any re-supply missions as too provocative.8

Abraham Lincoln believed that it would help the Union cause if the Confederates fired the first shot, but he was unsure how to achieve that goal. In fact, he was woefully ignorant of how to be commander-in-chief since he had only “a few months’ token service as a junior militia offi cer in the Black Hawk war of 1832, where his military experience included a (lost) wrestling contest with another captain for whose company would occupy a choice campground.”9

Lincoln sought information and consulted widely and frequently with his cabinet and other officials. He pleaded with the senior army general to keep him informed. “Would it impose too much labor on General Scott to make short, comprehensive daily reports to me of what occurs in his Department?”10 He even sent friends to provide first-hand reports on conditions in Charleston. Despite the pessimistic views of army leaders, he decided to send Fort Sumter a relief mission by sea under the command of his attorney general’s brother-in-law. He also secretly approved an army-sponsored plan to send supplies to Fort Pickens. Bureaucratic foul-ups prevented both missions from being carried out as planned – a harbinger of events throughout his administration. Both the army and navy planned to use the navy’s premier warship, the Powhatan, and conflicting orders were sent to its base in New York City. The ship sailed toward Florida, with its captain disbelieving last-minute orders from the president to go to South Carolina.11 On April 10, Confederate forces demanded the surrender of Fort Sumter and two days later began the bombardment that started the war.

The Civil War severely tested the established patterns of civil–military relations. By war’s end, Lincoln had a senior general he trusted, a loyal and effective Secretary of War, a strategy acceptable to most officials, and a Congress more supportive than disruptive. But that state of affairs was far from inevitable. In the early stages of the war, there were serious conflicts between the president and Congress, between each branch of government and senior military officers, and between career military men and the new volunteers. These conflicts were sometimes political, sometimes personal, sometimes over strategy, sometimes over minor tactical or technical matters. Normal disagreements were exacerbated by poisonous levels of distrust. Over time, however, the constitutional system worked. The president became the de facto as well as the de jure commander-in-chief; Congress raised the revenues, wrote the necessary laws, and approved the key appointments; and military commanders deferred to the civilian leaders even when they held them in contempt.

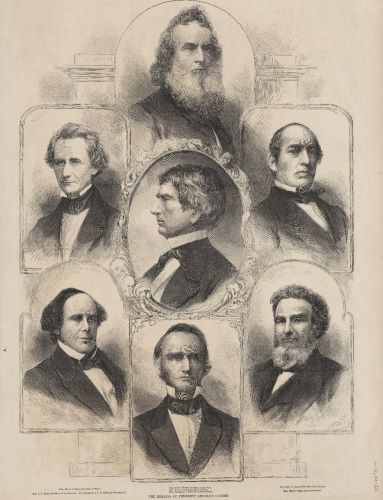

Reluctant Dictator

As soon as he learned of the attack on Fort Sumter, Lincoln convened his cabinet for the first of many lengthy sessions on handling the war. The cabinet was a fractious group, not least because Lincoln offered positions to four of his rivals for the Republican nomination, several of whom remained convinced that they were better qualified than the backwoods lawyer from Illinois. Throughout his term these ambitious politicians maneuvered against each other and even against the president, hoping to succeed him as the Republican nominee in 1864.12

Lincoln had won election with only 40 percent of the popular vote, winning the electoral votes of all of the free states except New Jersey, which split its votes between Douglas and Lincoln, and none in the south or border states. His Republican party had been formed only six years before. And as one historian described it, “The so-called party comprised several groups, under chieftains personally hostile and full of jealousy and rivalry, who had come together upon one question only.” What they agreed on was opposition to extending slavery into the new territories of the west. They disagreed, either as a matter of principle or as a question of political tactics, on whether slavery should be abolished where it then existed. Their 1860 platform, which Lincoln had quoted in his inaugural address, had declared “the right of each state to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively.”13

Preserving the union without abolishing existing slavery remained Lincoln’s goal in the immediate aftermath of the attack on Fort Sumter. He wanted to prevent additional secessions that could make Washington vulnerable or make military action against the rebels infeasible.

On April 15, he issued a proclamation calling on the states to mobilize 75,000 men in their militias for Federal service and summoning the Congress into special session starting July 4. The newly mobilized troops were to take back the forts and other property seized from the Union so that the laws could be properly executed. Lincoln also appealed “to all loyal citizens to favor, facilitate, and aid this effort to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our National Union.”14

Two days later Virginia voted to secede, and two days after that Lincoln ordered a blockade of southern ports to help put down what he called an insurrection. He remained concerned about Maryland, which was torn by pro-slavery and pro-Union factions. To secure the lines of communication and to prevent pro-secession uprisings, Lincoln declared martial law in Maryland on April 27 and allowed detentions without trial by suspending the writ of habeas corpus, the fi rst of eight similar actions during the course of the war.15

Lincoln took many acts of borderline constitutionality, hoping and expecting that Congress would later authorize his emergency measures – though the lawmakers waited until March 1863, to authorize his suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. In one dramatic case, Union soldiers arrested John Merryman, who had allegedly burned bridges and destroyed telegraph wires during the April, 1861 riots near Baltimore. The case was heard by the Chief Justice, Roger Taney, who ruled that Lincoln’s order was unconstitutional, since only Congress had the power to suspend the writ. Lincoln refused to comply with the ruling. Taney had to be content fi ling a report. Merryman was released a few weeks later when military authorities concluded that he could never be convicted by a Maryland jury.16

Lincoln also had to take steps to rein in some abolitionist fi rebrands, such as General Benjamin F. Butler, who ruled escaped slaves “contraband of war” and refused to return them to their owners. When the popular Republican General John C. Fremont proclaimed slaves in Missouri free, Lincoln revoked the order and shortly thereafter relieved Fremont of command. The president was still worried that abolitionist actions might drive Kentucky to secede, and that, he feared, would doom the Union cause. The most Lincoln could accept was the law passed by the special session of Congress in early August. It allowed confiscation of property – including slaves – but only if they had been directly employed by Confederate armed forces.17

Meanwhile, the cabinet members undertook their duties in support of the war. Secretary of State William Seward notified foreign governments of the US action; Navy Secretary Gideon Welles sent orders imposing the blockade; and Secretary of War Simon Cameron began planning for the equipping of the additional troops.

On May 3, Lincoln called for an increase in the size of the regular army by 23,000 as well as 18,000 more sailors and a force of 42,000 volunteers for a three-year enlistment.18 In the ensuing weeks, troops streamed into Washington. Lincoln and his cabinet members often reviewed them and met with their commanders. Both sides prepared for what they thought would be a short, decisive battle.

The most senior military officer, however, proposed a different strategy, one of limited means for limited ends. General Winfield Scott was an aging, infirm, and perhaps senile relic of a former era. Already 75 in 1861, Scott had been a general in the War of 1812, was a hero in the war with Mexico, ran for president on the Whig Party in 1852 while still in uniform, and remained loyal to the Union despite his Virginia birth. He was called “Old Fuss and Feathers.” In the spring of 1861 he devised a plan to strangle the south with a naval blockade of the coasts and naval and ground force seizure of the Mississippi River. This plan, dubbed “Anaconda”, had the advantage of limiting Union casualties and the disadvantage of requiring time to assemble the necessary forces.19

Lincoln and the politicians did not want to wait. They wanted to use the 90-day volunteers in some kind of battle, and believed that the capture of the new Confederate capital at Richmond, Virginia, would bring a quick end to the war. At a strategy conference on June 29, Lincoln told the field commander, General Irwin McDowell, who wanted more time for training, “You are green, it is true, but they are green, also; you are all green alike.”20

When that first major encounter came, on July 21 along the creek called Bull Run near the Virginia town of Manassas – Union forces tended to name their battles after streams, Confederates after nearby towns – the outcome was a powerful setback for the Union. Federal forces fled in disarray, shocking members of Congress who had ridden out to observe the anticipated Union victory.

Three months later, after Confederate forces established defensive positions along the Virginia border and General George McClellan prepared for combat without actually launching any attacks, Union forces did move against Ball’s Bluff on the Potomac River. Union forces suffered a quick and ignominious failure, including the death of Colonel Edward Baker, a close friend of the president and Senator from Oregon. These two defeats prompted the Congress, when it met in December, to establish an investigative committee.21

Congress was also primed to investigate problems in contracting and supply for Union forces. The man in charge of supply was Simon Cameron, a former Democrat who had become the Republican party boss in Pennsylvania and US Senator when Lincoln nominated him to head the War Department. Lincoln liked Cameron and wanted a Pennsylvanian in his cabinet, but tried to withdraw his offer of a position after being besieged with numerous reports of Cameron’s corruptness. Cameron reportedly ran his political machinery with bribery and intimidation. Another Pennsylvania Republican, Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, when asked by Lincoln whether Cameron was an honest man, replied, “I don’t think he would steal a red hot stove.” Even the incoming Vice President, Hannibal Hamlin of Maine, said that naming Cameron would have an “odor about it that will damn us as a party.”22

Cameron soon lived up to his sullied reputation. Facing wartime urgency, Cameron ignored existing legal requirements for competitive bidding and awarding contracts to low bidders. He favored suppliers and middlemen from his home state and paid dearly for poor quality goods. As two historians of the period concluded, “Cameron conducted the War Department as if it were a political club house; he used contracts freely to pay off old political debts and to shower additional favors on his henchmen.”23 In one celebrated case, the War Department paid $58,200 plus $10,000 for transportation to acquire one thousand horses for a Kentucky cavalry regiment – 485 of which had to be rejected as diseased and worthless.24 Lincoln confided to his secretary that Cameron had proved to be “utterly ignorant … Selfi sh and openly discourteous to the President[,] Obnoxious to the country [and] Incapable of either organizing details or conceiving and advising general plans.”25 The fi nal straw came in December 1861, when Cameron, without consulting with the president or informing him of his plan, released a report to Congress and the press calling for the creation of an army of former slaves – a policy Lincoln strongly opposed at the time.26

Lincoln responded to these setbacks not by changing strategy, but by changing personnel. In the fall, he decided to change the leadership of the army and the war department. He accepted the resignation of General Scott and forced the resignation of Secretary Cameron. In their places, he put General George McClellan and Edwin M. Stanton.

Coalition of Rivals

These events of 1861 show that the Union leadership was hardly unifi ed. Republicans were divided between abolitionists and union preservationists who were willing to tolerate slavery confined to the south. Democrats were split between those supporting war to preserve the union and those favoring negotiations for a peaceful settlement, either with separation or with reunion keeping slavery intact. Many of the generals considered themselves Democrats, and they hoped for an agreement that avoided massive bloodshed. McClellan and his West Point compatriots tended to favor European-style wars of maneuver rather than decisive battles or strategies of annihilation of enemy forces. Radicals dominated the Congress, and Lincoln was left to juggle the many disparate views.

The mood in Washington in January 1862, was captured by Congressman Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, who wrote to his wife: “Confidence in everybody is shaken to the very foundation. The credit of the country is ruined – its army impotent, its Cabinet incompetent, its servants rotten, its ruin inevitable.”27 Everyone hoped that McClellan and Stanton would be the heroes who would turn things around.

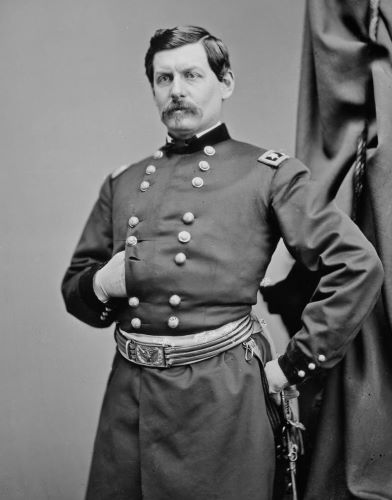

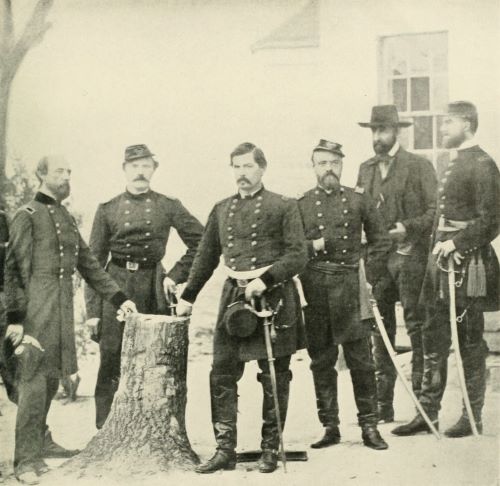

George McClellan had a distinguished career at West Point and in the war with Mexico. He had resigned his commission in 1857, in order to become an official of railroad companies in Ohio and Illinois. He was made a major general after the war broke out and was given command of the Army of the Potomac after McDowell’s defeat at Bull Run. A lifelong Democrat, he had a low opinion of the Republican administration. As he wrote to his wife, “I can’t tell you how disgusted I am becoming with these wretched politicians; they are the most despicable of men … The Presdt [sic] is nothing more than a well meaning baboon.”28 He wrote of being “bored and annoyed” at an October 1861 cabinet meeting. “There are some of the greatest geese in the cabinet I have ever seen – enough to tax the patience of Job”, he wrote.29

Lincoln made a valiant effort to consult with his top general, frequently visiting his home in the evening to discuss strategy. But McClellan rebuffed his commander-in-chief. In one notorious case, on November 13, the general returned home from a wedding party and went to bed, deliberately ignoring the president and secretary of state, who had been waiting over an hour to talk to him.30 Lincoln would spend the next year cajoling, pushing, reassuring, and supporting McClellan before finally deciding to replace him.

Edwin M. Stanton was another inauspicious choice, but one who turned out to be a loyal, devoted, and very effective cabinet officer. He was a pro-union Democrat from Ohio who had been attorney general in the final months of the Buchanan administration. He had a passing acquaintance with Lincoln in 1855, when he was involved in the McCormick reaper patent case, in which the Illinois lawyer had been retained in case the trial were heard in Chicago. Stanton was rude and snobbish to all of his underlings, but Lincoln held no lasting grudge from the encounter. Stanton openly disparaged the new president in 1861, referring to him as “the original gorilla.” He also wrote to just-departed President Buchanan, “No one speaks of Lincoln or any member of his cabinet with respect or regard.”31

The Ohio lawyer had many friends in that cabinet and Lincoln wanted to give prominent positions to pro-war Democrats, so Stanton was a welcome addition when the president lost confidence in Cameron. Stanton was also well regarded in Congress and, perhaps ironically, by McClellan. Soon after Bull Run the general turned to the lawyer as a legal adviser and friend, frequently using Stanton’s house as a refuge from other officials, even the president. Ultimately, however, McClellan bitterly concluded that “His purpose was to endeavor to climb upon my shoulder and then throw me down.”32

McClellan became general-in-chief in November, when Scott was forced into retirement. Stanton took over the War Department in January, when Cameron was reassigned as Minister to Russia. The general continued his preparations for a spring offensive, while the secretary of war seized effective control of his department and, more broadly, of the running of the war.

Stanton took office determined to improve administration and push the army into action. As he wrote to Charles Dana, “As soon as I can get the machinery of the office working, the rats cleared out, and the rat-holes stopped, we shall move. This army has got to fight or run away; and while men are striving nobly in the West, the champagne and oysters on the Potomac must be stopped.”33

The new secretary seized control of communications, both with field armies and the press, by moving the telegraph office, which had been at McClellan’s headquarters, next to his own. This action also meant that the president was a frequent visitor, walking next door from the White House and often staying for hours at a time. Stanton set aside two rooms for McClellan to use as headquarters, but the disgruntled general seldom used them. The secretary also created a separate military telegraph system which, by the last year of the war, employed more than 1,000 men and stretched over 5,000 miles of lines.34

Stanton tightened the administration of military contracting with a return to competitive bidding and closer oversight. Through old friendships and persuasive powers he won funds from Congress to refurbish his department’s dilapidated building and to hire several dozen additional personnel. He also won passage of a law giving the president power to seize the railroads and telegraph for military purposes. In fact, the railroads had been very cooperative, but Stanton used the law as a lever to negotiate reasonable rates, standardized gauges and signaling, and military cargo priority. He then used railroads to engineer the rapid supply of Union forces during and after key battles, as demonstrated at the time of Antietam and later Chattanooga.35

The civilian secretary tried to forge close professional ties with McClellan and advised the general on ways to improve his standing with the cabinet. Early on, the two men spent entire days together, in apparent harmony. But eventually Stanton, wanting an alternative, disinterested military viewpoint, hired a retired general, Ethan Allen Hitchcock, who had a distinguished military record and had been commandant at West Point. Hitchcock was often amazed at how willingly and earnestly Stanton accepted his military advice.36

The secretary cultivated close ties to Capitol Hill. He welcomed frequent meetings with key legislators. He deflected one investigator who had been making wild charges about disloyal officials by meeting with one of the congressman in question, going over his bulging files, and then dismissing one officer and three clerks. He made a special effort to engage with the joint committee set up to investigate the conduct of the war, attending many of its secret sessions and even using it to elicit information and uncover fraud.37

Surprisingly, Stanton also forged an extremely close and loyal relationship with the president. Lincoln warmed to the man he called his “Mars”, telling a journalist that his cabinet officer was “utterly misjudged.” One of the army telegraphers called the president and his secretary the heart and the head of the war. Grant later observed that “Stanton required a man like Lincoln to manage him”, that Lincoln dominated his subordinate by “that gentle firmness.”38

Each could veto the acts of the other, but Stanton would ultimately defer if he was confident that the president had reached a firm decision. Lincoln himself described the arrangement. “I want to oblige everybody when I can; and Stanton and I have an understanding that if I send an order to him which cannot be consistently granted, he is to refuse it. This he sometimes does.”39

Stanton’s biographers report an incident which illustrates this relationship:

Once when Lincoln sent a petitioner to Stanton with a written order complying with his request, the man came back to report that Stanton had not only refused to execute the order but had called Lincoln a damn fool. Lincoln, in mock astonishment, asked: ‘Did Stanton call me a damn fool?’ Being reassured on that point, the President remarked drolly: ‘Well, I guess I had better step over and see Stanton about this. Stanton is usually right.’40

Organizing for Victory

When it came to fighting the war in 1862, the warriors and politicians clashed repeatedly. McClellan and much of the officer corps disagreed with the president and secretary of war over grand strategy, domestic politics, military professionalism, and the command and control of major military operations.

On many issues related to the war and slavery, Lincoln tried to preserve his freedom of action and avoid premature commitments by claiming, “My policy is to have no policy.” But he had a clear vision of what he thought the army should do: attack, attack repeatedly, and destroy the Confederate army. He disparaged what he called “strategy”, but what he meant was the Napoleonic war of maneuver. He favored decisive battles with Union victories as the best way to end the war quickly. What today’s soldiers would call the enemy’s “center of gravity”, the capture of which would lead to its collapse, was to Lincoln the rebel army. “I think Lee’s army and not Richmond is your true objective point”, he wrote in 1863, expressing a view he held throughout the war after the initial battle at Bull Run. McClellan and his successors, until Grant, seemed to prefer wars of maneuver and the capture of political objectives like the Confederate capital.41

Domestic politics also divided the Republican civilian politicians from much of the military leadership. While some generals were viscerally anti-politician – General William T. Sherman complained to General U.S. Grant, “I am not a politician, never voted but once in my life, & never read a political platform”42 – many were professed Democrats.

Of the 110 generals in the Union army in 1861, according to a Republican Senator, 80 were Democrats. According to a Republican congressman in 1863, four-fifths of the brigadier- and major-generals in the Union army were Democrats. As one historian has noted, “Most Union generals, through whatever mixture of conviction and self-interest, displayed rather than disguised their political leanings.”43

Those political leanings should not be surprising, however, since most senior officers had risen in the ranks under Democratic administrations and with partisan sponsorship. Until Lincoln took office, Democrats had controlled the White House since 1828 except for two single terms won by war heroes – William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor – running as Whigs. Democrats had also controlled both houses of Congress for all but six of those years. Moreover, the Republicans were a new national party, having elected its first members to Congress only in 1854.

The newly empowered Republicans remained suspicious of the officer corps, and even critical of West Point. Many viewed the military academy as “the hotbed in which rebellion was hatched”, and they decried the many regular army officers defected to the Confederacy – about one in every four in the army in 1861. Republicans claimed, however, that no enlisted men turned traitor.44 The distrust between career soldiers and the militia leaders, rooted in the Framers’ suspicions about a standing army and continuing through most of American history, had political overtones in the Civil War.

In the mobilization for war, there were essentially Republican and Democratic armies. Mostly Democratic officers led the regular army regiments, while the newly formed volunteer units were often peopled and led by avowed Republicans who were willing to fight for their political beliefs regarding slavery and the Union. Of course, many pro-war Democrats were commissioned to lead volunteer units, but they too were taking up arms for the sake of their political views. Major General Jacob D. Cox, founder of the Republican party in Ohio and never before in the military, explained the rise of political generals:

In an armed struggle which grew out of a great political contest, it was inevitable that eager political partisans should be among the most active in the new volunteer organizations. They called meetings, addressed the people to arouse their enthusiasm, urged enlistments, and often set the example by enrolling their own names first.45

Lincoln claimed that “in considering military merit … I discard politics.”46 But in fact he was quite adroit in building a bipartisan administration and army with careful attention to political affiliations and factors. The general-in-chief after McClellan, Henry Halleck, complained, “I have done everything in my power here to separate military appointments and commands from politics … but the task is hopeless.”47 What the president and Stanton did do, however, was to quash those officers who tried to play politics against the administration. As Stanton wrote to Lincoln in January, 1863, “[Army officers who] indulge in the sport [of politics] must risk being gored. They can not, having exposed themselves, claim the procedural protections and immunities of the military profession.”48

Warriors and politicians also clashed over their respective roles and responsibilities, by way of differing views of military professionalism. Lincoln went out of his way to show deference and respect for military commanders, such as by going to see Scott and McClellan rather than summoning them to the White House. His letters to his commanders were unfailingly polite, even when remonstrating them or issuing clear orders. In a letter to General Joseph Hooker, for example, he praised the officer’s abstinence from politics as well as his ambition and self confidence. But he also pointed out, “there are some things in regard to which I am not quite satisfied with you”, and went on to criticize, as we shall see, Hooker’s call for a dictatorship in Washington.49

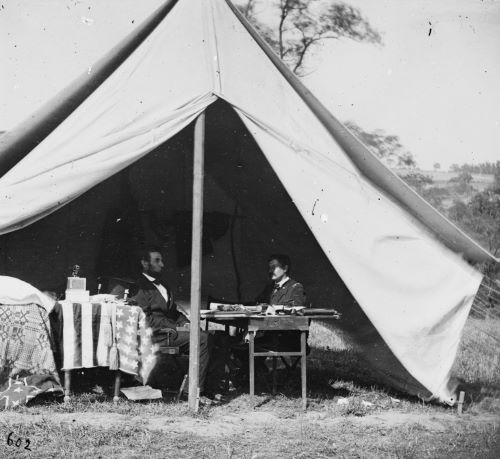

On paper, Lincoln subscribed to the notion that military operational plans were beyond his purview. Writing to Grant in 1864, he declared, “The particulars of your plans I neither know or seek to know. You are vigilant and self-reliant; and, pleased with this, I wish not to obtrude any constraints or restraints upon you.” Only a few days later, however, he ordered specific changes in Grant’s plans for the Red River campaign. In fact, as Eliot Cohen has demonstrated, Lincoln remained “deeply immersed in the details of military operations”, exercising strong oversight, though he did it more by questioning, prodding, and suggesting than by direct orders.50

The commander-in-chief also made several visits to the front lines to confer with his generals and to observe the condition of the men and their equipment. He and Stanton also sent their own bureaucratic spy, Charles Dana, who was ostensibly investigating military pay problems, but in fact was instructed by Stanton that “your real duty will be to report to me every day what you see.” Dana was even given a special cipher to use in his reports.51

Generals like McClellan, however, resented political intrusions, either by the president or the investigative congress. Few of the congressional fi re-brands had any military experience, yet they gratuitously offered their advice on strategy and tactics. The commanders resented the pressure to launch attacks before their troops were trained and ready to their professional standard. The ritual complaint from the politicians became, why don’t they attack? Many of the West Point professionals also disliked the presence of so many newly commissioned generals who had political connections but little military experience. These cultural clashes were not unique to nineteenth century America, but they did at times infringe upon the conduct of the war.

In one famous incident, Lincoln dismissed from service a politically well-connected major, John Key, who was overheard declaring that the army wanted a negotiated peace and was avoiding major battles. “That is not the game”, Key said. “The object is that neither army shall get much advantage of the other; that both shall be kept in the field till they are exhausted, when we will make a compromise and save slavery.” When Key sought reinstatement, the president refused, saying “I had been brought to fear that there was a certain class of officers in the army, not very inconsiderable in number, who were playing a game to not beat the enemy when they could, on some peculiar notion as to proper way of saving the Union …. I dismissed you as an example and a warning to that supposed class.”52

In January 1862, Lincoln held several meetings to discuss the conduct of the war. On January 6, he met with the new congressional committee investigating the conduct of the war and heard their criticisms of McClellan and their demands for decisive action. He said he had no knowledge of McClellan’s plans or the reasons for delay, but that he had no intention of interfering with the commander. Afterward, he wrote to McClellan, who had been confined to his sickbed for several days, urging him to meet with the committee members as soon as possible.53

On January 10 he began a series of meetings with his cabinet and senior generals. At one point he visited the Quartermaster General, Montgomery Meigs, and told him, “The people are impatient; [Treasury Secretary] Chase has no money, and he tells me he can raise no money; the Gen[eral] of the Army has typhoid fever. The bottom is out of the tub. What shall I do?”54 McClellan finally showed up on January 13, but still refused to give details of his plans for fear of a leak. The same day, Lincoln replaced Cameron with Stanton, and the new secretary of war began holding lengthy meetings with the congressional committee.55

Responding to the political pressures for action, Lincoln then prodded McClellan on January 27 by issuing General War Order No. 1, which commanded all Union armies to make a coordinated advance on all fronts by Washington’s Birthday, February 22. Four days later he issued a special War Order No. 1 to the Army of the Potomac, directing it “after providing safely for the defense of Washington,” to seize Manassas Junction and advance toward Richmond by that date.56

McClellan objected in a 22-page letter, revealing that he preferred to attack Richmond from the east. Lincoln sought the views of McClellan’s division commanders and found eight in favor and four opposed, but only two of the four supported the president’s idea of a direct assault. “We saw ten generals afraid to fight”, commented Stanton.57 But Lincoln acquiesced in the judgment of the men in the field.

On February 19, Stanton corralled McClellan to meet with some members of the congressional investigating committee. When the general explained that one reason for delay was to secure a line of retreat, Senator Benjamin Wade of Massachusetts exploded. The Army of the Potomac, he said, could “whip the whole Confederacy if they were given the chance; if I were commander, I would lead them across the Potomac, and they should not come back until they had won a victory and the war ended, or they came back in their coffins.”58 The general noted that Stanton did not once speak up in his defense.

By early March, however, with McClellan still preparing but not advancing, Lincoln came under renewed pressure from Congress and his advisers to discipline his top general. The committee members urged the removal of McClellan, but had no one to propose in his place. “Anybody will do for you”, Lincoln told Senator Wade, “but I must have somebody.”59 Stanton agreed with the congressional recommendation for a reorganization of the army into corps d’armée instead of the existing division structure. On March 8 Lincoln endorsed McClellan’s plan for the peninsula campaign but ordered the reorganization of the army. He also conditioned his approval on McClellan’s leaving enough forces behind to secure Washington. On March 11, he took away his commander’s title as general-in-chief, leaving him only in charge of the Army of the Potomac.60 A month later, he warned the general that the country was watching him, that “it is indispensable to you that you strike a blow. I am powerless to help this.”61

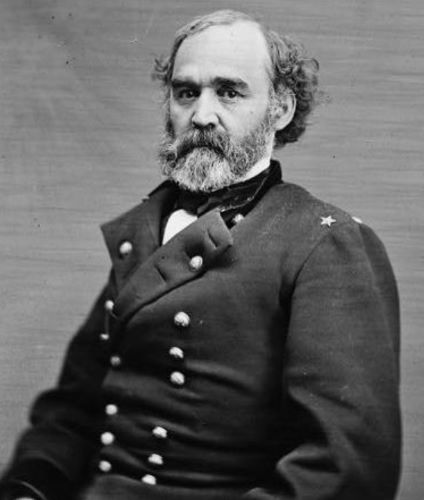

From March until Henry Halleck was promoted to general-in-chief in July, Lincoln and Stanton effectively ran the war. They faced a difficult task since there was no unity of command, but eight separate commands reporting to Stanton. The amateur generals did reasonably well, coordinating operations in various theaters, including an offensive in the west. Halleck turned out to be indecisive, however, forcing Lincoln and Stanton to maintain close control.62

Meanwhile, McClellan’s move toward Richmond was stalled and then turned back by the new commander of the Army of Northern Virginia, Robert E. Lee. Anxious and shaken, McClellan wired a hysterical message to Stanton. “If I save this army now, I tell you plainly that I owe not thanks to you or to any other persons in Washington. You have done your best to sacrifice this army.”63 Lincoln responded with a promise of reinforcements, but faced continued pressure to replace his failing commander.

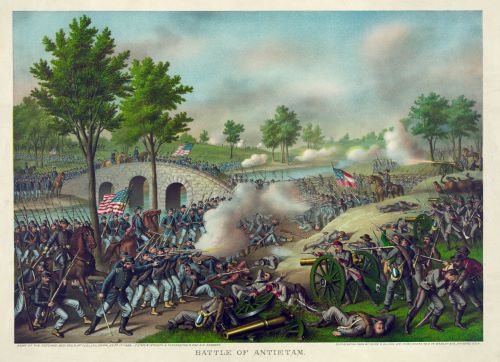

Lee then moved north, winning a second battle at Bull Run at the end of August and attacking into Maryland in September. Desperate to defend the capital, Lincoln overruled his cabinet by putting McClellan in charge of forces around Washington. After the bloodiest single day of the war, in the battle at Antietam Creek, Lee headed south, allowing the Union to claim a victory. Lincoln ordered McClellan to follow Lee and deliver a knockout blow, but the Union general claimed logistical problems.

New Team, New Strategy

These events – the continuing, inconclusive, deadly war with no immediate prospect of victory – helped convince Lincoln to change his war aims, using the sense of victory after Antietam as the occasion to announce it. Until then, the president had insisted that his only goal was to restore the Union. He avoided the issue of slavery. But by the late summer of 1862 he decided to announce his intention to proclaim the emancipation of slaves in the south, at least in those areas which had not returned to the Union by January 1, 1863. He knew this would be popular in Republican areas, and he hoped to strengthen his party in the 1862 congressional elections. He also had to deal with the practical problems raised as Union forces moved into rebel territory and had to do something about the slaves they encountered.

Lincoln also realized that McClellan did not favor the kind of vicious, all-out war that the president believed was necessary to defeat the rebels. The two men made clear their differing views in July, when they met at Harrison’s Landing, Virginia. The general gave the president a long letter, arguing that the war “should be conducted upon the highest principles known to Christian Civilization.” He opposed “confiscation of property, political executions of persons” and “forcible abolition of slavery.”64 Lincoln and the Congress were moving in the opposite direction, both with a new confiscation act liberating the slaves of those who supported the rebellion and with orders by General John Pope, approved by Stanton, ordering his army to live off the country, to not worry about protecting the private property of rebels, and to arrest all disloyal males and females. As Stanton told a journalist who asked about the treatment of captured guerrillas, “Let them swing.”65

Immediately after the 1862 elections, Lincoln finally ousted McClellan, turning command over the General Ambrose Burnside, the first of several officers who tried and failed to achieve a decisive victory over the next year and were promptly replaced. After suffering heavy casualties at Fredericksburg, Lincoln gave command to General Joseph Hooker. But the president gave the new commander an explicit warning:

I have heard, in such a way as to believe it, of your recently saying that both the the Army and the Government needed a Dictator. Of course it was not for this, but in spite of it, that I have given you the command, Only those generals who gain successes, can set up dictators. What I now ask of you is military success, and I will risk the dictatorship.66

Within fi ve months, however, Hooker had been defeated at Chancellorsville and was refusing to defend Harper’s Ferry as Lee moved north. Hooker resigned in protest, and Lincoln selected General George Meade to take command – just two days before the two armies stumbled into the giant battle at Gettysburg. Once again, the Union prevailed, Lee retreated, and the Union commander failed to attack the withdrawing troops. Lincoln wrote a tough letter to Meade – “Your golden opportunity is gone, and I am distressed immeasurably because of it” – but then decided not to send it. Meade, learning of the president’s dismay, offered his resignation but was persuaded by General Halleck to withdraw it.67

Meade held important commands for the duration of the war. But he seemed to have no grand plan for victory, and Lincoln turned instead to a newly victorious general in the west, U.S. Grant, who did. Grant believed in, and practiced successfully, a war of annihilation of the enemy. He was willing to suffer heavy casualties in order to defeat the enemy. As he told one officer, “The art of war is simple enough. Find out where the enemy is. Get at him as soon as you can. Strike him as hard as you can and as often as you can, and keep moving on.”68

Lincoln put Grant in command of the western armies in October, then brought him back to Washington in March 1864, to give him supreme command of the Union armies, with the newly revived rank of Lieutenant General. Grant pushed on, heedless of heavy casualties, against Lee’s forces. General William T. Sherman moved from Tennessee across Georgia, taking his scorched earth campaign directly to southern civilians, and capturing Atlanta on September 2.

Relations among the civilian and military leaders were surprisingly good during 1864. General Halleck dismissed reports of high level quarrels as “all ‘bosh.’” One of Lincoln’s secretaries said that “the stories of Grant’s quarreling with the Secretary of War are gratuitous lies. Grant quarrels with no one.”69 And Grant himself wrote an extraordinary letter to Lincoln in May:

From my first entrance into the volunteer service of the country to the present day I have never had cause of complaint, never have expressed or implied a complaint against the administration or the Secretary of War for throwing any embarrassment in the way of my vigorously prosecuting what appeared to be my duty. Indeed, since the promotion which placed me in command of all the armies … I have been astonished at the readiness with which everything asked for has been yielded, without even an explanation being asked.70

Despite this outward harmony, however, Lincoln was acutely conscious of the impending presidential elections. McClellan was preparing to run against the president for the Democrats and the influential New York Herald was promoting Grant as a candidate. Lincoln may have named Meade to replace Hooker because Meade had been born abroad and was considered ineligible to run for president. Only when Lincoln had received a letter from Grant pledging that nothing could persuade him to be a candidate did the president support the enactment of a law reestablishing the rank of Lieutenant General, a measure pushed in the Congress as a reward to Grant.71

Congress at War

In the nineteenth century, Congress was still a part-time legislature, typically meeting only three months per year, from early December until March 3. Every other year’s session was lame-duck, peopled by members elected two years before and meeting after the latest balloting. Lincoln accelerated the convening of the new thirty-seventh Congress by calling a special session in July of 1861 rather than waiting for the normal time in December. The Senate alone had met for three weeks following Lincoln’s inauguration in order to receive and act on nominations for the cabinet and lesser posts, including military officers. But the Senators had finished their work and adjourned two weeks before the attack on Fort Sumter.

Returning on July 4, the new thirty-seventh Congress spent a busy month responding to Lincoln’s call with a burst of legislative activity. Republicans had controlled the House of Representatives during the second half of Buchanan’s presidency, then gained majorities in both houses in the 1860 elections. Lincoln’s party had a 33–15 lead over the Democrats in the Senate, with three from other parties, and a commanding 108–44 majority in the House, with 31 from other parties.72

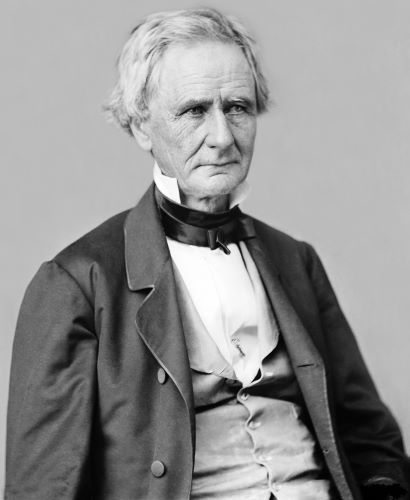

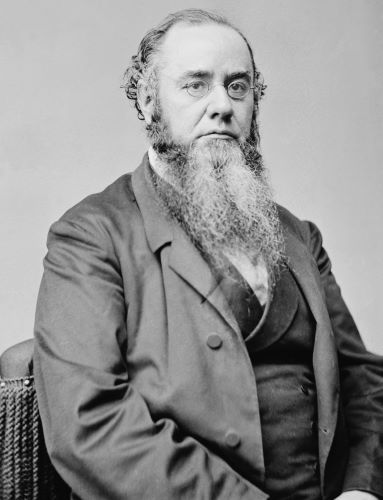

Legislators took seriously their constitutional powers to raise and support armies and to provide and maintain a navy, as well as to set the rules for the armed forces. Senator Benjamin Wade of Massachusetts expressed the Legislative Branch view of things when he said that the President might be Commander-in-Chief, “but Congress, the legislative power sitting superior to him or any the magistrate in the nation, may regulate, modify, and direct whatever principles they please [that] their chief commander shall act upon and execute.”73

While the president enforced civilian control through his chain of command, Congress asserted its own civilian control through its powers of lawmaking and funding. Congress also had enormous influence over the selection of military personnel, starting with its authority to nominate men to attend the academies at West Point and Annapolis, the entry points for commissioned officers. While congressmen did not have explicit patronage power over military appointments, as they did over most civilian positions, they frequently recommended officers for key assignments in their states and took personal interest in their careers. As two historians of the patronage system concluded, “Congressmen or Congressional delegations usually gave the President the names of those whom they wished appointed as brigadiers, major generals, and lesser officers.”74

Many in Congress were more radical than the president, more willing to make the war about slavery rather than simply preserving the Union. On July 9, for example, the House passed a resolution declaring that soldiers had no duty to capture and return fugitive slaves. After wrangling over more extreme measures, Congress finally passed, on August 6, a compromise measure confiscating only that property used “in aid of the rebellion” – that is, only slaves actually employed in arms or labor against the Union could be freed. In the Senate, Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, chairman of the military affairs committee, met resistance to his measure retroactively approving Lincoln’s call for volunteers, increase of the regular army, blockade of southern ports, and suspension of the writ of habeas corpus. After much debate, the Senate approved all but the language relating to the writ.75 To fund the war, it enacted America’s first income tax.

With the Senate in session, the president submitted list after list of military nominations, most of which were routinely and promptly confirmed – over 10,000 in the course of the war. The military affairs committee acted without partisan splits on appointments. But its chairman, Senator Wilson of Massachusetts, did refuse to confirm any officers who had returned fugitive slaves to their masters.76

While passing laws to organize and equip the rapidly expanding army, Congress also decided to increase its oversight of the process. In July the House established a special committee to investigate reports of fraud and mismanagement in government contracting. That committee later exposed scandals in Missouri under the regime of General Fremont. Senator Wilson welcomed visits by officers and enlisted men who wished to tell his committee of their views and problems.77

Although Congress was out of session from early August until December, some members continued to push for offensive actions. After the Union defeat at Ball’s Bluff in October, for example, three Senators harangued General McClellan and then met with Lincoln to press their views.78

The union defeats at Bull Run and Ball’s Bluff prompted legislators in both houses to create an investigative committee when Congress reconvened in December. A New York congressman introduced a resolution calling for information to be provided regarding Ball’s Bluff. In the Senate, one member proposed a committee of inquiry into both recent defeats and then, when others wanted to add additional topics to the committee’s agenda, Senator Grimes of Iowa proposed a joint committee to examine all aspects of the war, with “the power to send for persons and papers.” Senator Sherman of Ohio noted that voting appropriations was easy, “but if we ignore the high duty imposed upon us as representatives of the people to investigate the conduct of the war and of all the officers of the Government, we neglect the chief duty that is now imposed on us.” Both houses agreed, and the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War (JCCW) was established on December 20, with three Senators and four Representatives, including one Democrat from each chamber. Senator Benjamin Wade of Massachusetts was named chairman. None of the original members had any prior military experience, and all but one were lawyers. Radicals had a 4–3 majority over moderates.79

The JCCW had the tools available to any congressional committee – oversight, subpoena, publicity, presumptive right of consultation – and it used them vigorously. Some historians see the committee as a hindrance to the war effort, treating several senior offi cers unfairly and trying to impose its strategic ideas on the administration.80 That was certainly the view of two men who later became president – Woodrow Wilson and Harry Truman – and who fought to prevent creation of such an intrusive committee during the two world wars.

I believe that the JCCW should be seen as an ordinary and legitimate instrument of congressional prerogatives. It had an important oversight function, but its members had their own political motivations, and they used their committee positions to advance themselves and their views. The president and secretary of war conferred with committee members frequently, not only because of any threat of investigation but also because these men represented important segments of public opinion, whose support was ultimately vital for the war effort. Some senior commanders resented being called before the committee – an attitude not uncommon even today – but that is an important feature of the American system of civilian control.

Two facts in particular defend the advantages of having such a committee: it worked hard and it worked in secret. Committee members met almost daily when Congress was in session, gathering information and conducting hearings. It held 272 official sessions during three and a half years. Its members initiated meetings with the president at least eight times, and with Secretary Stanton even more often. And although the committee’s 11 reports were highly critical of many aspects of the war, these reports were released only after weeks and months of secret sessions. There was no parade of leaks to shape news coverage and public opinion.81

Members traveled widely to gain first hand impressions and to understand what they were investigating. Subcommittees went to Boston, New York, Annapolis, Illinois, and to the battlefields in Virginia, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Besides investigating military disasters, the committee looked into several operations on which it filed no report. It also looked into many allegations of contracting and supply problems. A further proof of respect for the JCCW, lawmakers frequently referred press allegations to the committee and requested investigations.82

On the other hand, it is true that the committee had its favorites, like General Fremont, whom it defended despite significant incriminating information. And it had its targets, like McClellan and General Charles P. Stone of Ball’s Bluff, whom it pursued unmercifully.83 It also had a perhaps naïve strategy – attack, attack, always attack – which was attractive to civilians sitting in Washington. But these views were no different from those of many in the cabinet, elsewhere in Congress, or in the press.

On several occasions, the committee was the conscience pushing Lincoln toward emancipation or the “bad cop” he could cite when politely urging generals to take the offensive. Its very records provide key documentation for our understanding of the war and the many confusions attendant to its conduct. Commanders were probably more careful because they anticipated questions from the legislators. Speeches by its chairman, drawing on its reports, were widely circulated by the Republican party during the 1864 presidential campaign.84

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles reflected a critical view of the JCCW when he said, “There must be something in these terrible reports, but I distrust Congressional committees. They exaggerate.” The members defended themselves and explained their purpose in an 1863 report: “Your committee therefore concluded that they would best perform their duty by endeavoring to obtain such information in respect to the conduct of the war as would best enable them to advise what mistakes had been made in the past and the proper course to be pursued in the future.” Chairman Wade explained to McClellan:

We are here armed with the whole power of both houses of Congress. They have made it our duty to inquire into the whole conduct of the war; into every department of it. We do not want to do anything that will result in harm or wrong. But we do want to know, and we must know if we can, what is to be done, for the country is in jeopardy.85

Congressional oversight was not omnipresent, however, for even during some of the most important periods of the war the legislators were out of session for extended periods. Most members were away from Washington during August 6 to December 2, 1861; July 17 to December 1, 1862, March 14 to December 7, 1863; and July 4 to December 5, 1864. In other words, Congress was absent during the Shenandoah Valley and Antietam campaigns in 1862, during the musical chairs of generals in 1863, and during Grant’s long, bloody campaign of 1864.

One of the most difficult issues faced by Congress was the question of conscription. In July 1862, the legislators approved amendments to the Militia Act reiterating the obligation of all able-bodied males 18–45 years of age and requiring up to nine months’ federal service. Using this new law, Lincoln on August 4 announced a draft of 300,000 men for nine months for all those states which had not met their quotas of volunteers for three-year terms. Practical problems prevented this measure from ever having real effect, so the lame-duck Congress on its final day, March 3, 1863, passed a comprehensive conscription bill. This measure required house-to-house canvasses for draftees, but allowed men to avoid service by finding a substitute or by paying a commutation fee of $300.86

This law came about through the normal legislative process of pulling, hauling, and compromise. Both bills, in 1862 and 1863, became vehicles for amendments dealing with emancipation and military service for blacks. Shifting majorities passed or defeated amendments trying to deal with these topics, along with the underlying conscription issue.87 Senator Wilson, chairman of the Military Affairs Committee, offered a fl oor amendment, previously rejected by his committee, for the $300 commutation fee. An important factor behind Wilson’s support of this fee, in addition to pressure from wealthy constituents, was to help highly industrialized Massachusetts maintain its labor supply. Later he persuaded Stanton to increase enlistment bonuses so as to minimize the need for draftees. The draft riots of 1863 and other public opposition drove Congress in 1864 to amend the law, repealing the commutation fee except for conscientious objectors. On another occasion, Wilson won enactment of a measure granting equal pay for black and white soldiers, and making it retroactive to the date of enlistment.88 These actions display Congress in action on the details of major legislation. Members were following their individual policy and political judgments; the executive branch was not the key player.

As things turned out, the major impact of the draft law was to stimulate volunteer enlistments. In the first draft call of 1863, 255,373 were called; 117,986 hired substitutes; 86,724 paid the commutation fee; and 4,316 failed to show; only 46,347 – 18 percent – actually entered the ranks.89 Overall, only six percent of the 2.7 million men who served in the Union army during the Civil War were directly drafted.90

The Politics of War

Elections strongly influenced the course of the war. Lincoln’s victory in 1860 drove many southern states to secede. The prospect of congressional elections in 1862 led the president and congressional Republicans to push for a strong offensive to end the war or at least demonstrate Union resolve. The sense that Antietam was a Union victory, as Lee retreated into Virginia, reassured Lincoln enough to announce his planned emancipation proclamation. But the Republican losses in the 1862 elections made Lincoln more radical on war aims and tactics, and perhaps more desperate to find a winning general. In 1864, Lincoln was unsure of winning re-nomination until the Baltimore convention in June and fearful of defeat at least until the confidence-boosting fall of Atlanta in September.

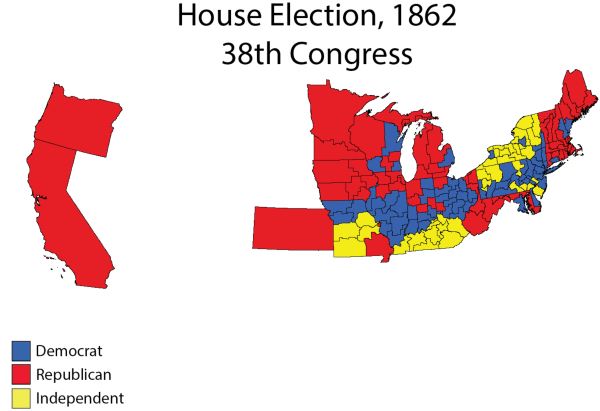

In 1862, the Republicans held on to 33 of 52 Senate seats, but saw their lead in the House drop from 108–44 – plus 34 of other parties – to 85–72 – with 27 from other parties. These results could deny them a working majority.91

Stanton reacted to these setbacks by working to guarantee a strong Republican turnout in the 1863 state elections and in the 1864 presidential contest. He made sure that Ohio defeated a leading peace Democrat running for Governor, for example, by arranging for Ohio troops to vote in the field and allowing war department clerks to travel home with free railroad passes. Lame-duck Democrats tried to pass a bill censuring Stanton and forbidding military officers from interfering in civil elections, but the measure failed.92

In 1864, Stanton pressured military officials to help Republican state agents and to thwart the Democrats. Entire regiments were furloughed home to crucial states. As Charles Dana commented, “all the power and influence of the War Department … were employed to secure the re-election of Mr. Lincoln.”

Stanton knew how strongly the men in uniform supported the president: Lincoln got 53 percent of the votes overall, but a rousing 78 percent of those of Union soldiers.93

Political considerations also influenced military goals and strategy. They help explain why Lincoln moved to the radical position on freeing slaves and using them in the army. They help explain why northerners embraced Sherman’s attacks on the people of Georgia and why they accepted the heavy casualties under Grant, which led to victories over Lee. Congress reflected the divisions within the country, and Lincoln steered a course through them.

At the end, however, there was still basic split – between Lincoln and the moderates who favored a benevolent reconstruction and the radicals who demanded southern capitulation and black empowerment. The president used a pocket veto to kill the Wade–Davis bill in 1864, which would have imposed a congressional plan antithetical to Lincoln’s approach. For example, it would have required a majority of each seceded state to take an oath of past as well as future loyalty in order to reestablish their own local governments. Lincoln favored a prospective loyalty oath and a 10 percent threshold of citizens taking the oath.94

As the Confederate forces seemed on the verge of surrender, Lincoln took special measures to ensure that his more lenient approach was followed. On March 3, 1865, he specifically ordered Grant not to “decide, discuss, or confer upon any political questions” with General Lee. “Such questions the president holds in his own hand; and will submit them to no military conferences or conversations.” When Sherman, shortly after Lincoln’s assassination, offered generous terms to General Joseph Johnston – including provisions on the recognition of southern governments, referral of measures to the Supreme Court, and a general amnesty – Stanton ordered the deal revoked, an action which led the angry Sherman to refuse to shake the War Secretary’s hand during a grand review of Union troops a few weeks later.95

Assassination and Aftermath

The struggle over control of the military continued even after the end of the war and the assassination of the president. Indeed, Andrew Johnson was impeached and nearly removed from office because he refused to obey the law giving Congress the power over the appointment of the Secretary of War and other officials. The underlying dispute was that Johnson favored a more forgiving policy toward the former rebels, while the radical Republicans in Congress insisted on more punishment for southern whites and more empowerment for southern blacks. As the occupying force, the US Army was caught in the cross-pressures.

At the apex of the power struggle was Secretary of War Stanton, who sided with the radicals. Asked to resign by President Johnson in August 1867, Stanton refused, relying on the Tenure of Office Act, passed over Johnson’s veto, which prohibited the removal of cabinet officers until their successors had been confi rmed by the Senate. He did, however, step aside and let General Grant act as interim secretary until December, when the reconvening Congress passed a resolution supporting him. Stanton then encamped in his offi ce and refused repeated presidential orders to surrender power. On the very days that Johnson tried to force the issue, impeachment resolutions were filed in the House and reported by Committee in February 1868. Stanton remained at his post until May, when the Senate fell one vote short of convicting and ousting the president.96

Stanton resigned; Grant was chosen as Republican candidate for president in the fall elections; and Reconstruction proceeded as intended by the Congress. The era of congressional dominance of government, briefly interrupted by the demands of Civil War, resumed. It was destined to last for over three decades, until Theodore Roosevelt came to power. In the interim, the army was punished for having been the implementer of Reconstruction. A key feature of the settlement of the disputed presidential election of 1876, which awarded Rutherford B. Hayes the electoral votes to become president, was the removal of US troops from the southern states and passage of the posse comitatus law, which still forbids the use of troops for domestic law enforcement.

The legacy of congressional involvement in the war was also negative. When Congress declared war against Germany in 1917, President Woodrow Wilson vigorously opposed any effort to create the equivalent of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War. In time, however, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee became the focal point for skeptical oversight and ultimately the engine of defeat of the Versailles peace treaty. In the Second World War, then Senator Harry Truman, mindful of the precedents, actively worked to limit his committee, the Special Committee to Investigate the National Defense Program, to matters of military contracting. He did not try to oversee the strategy or conduct of the war.

The Civil War poisoned American civil–military relations so much that it took several generations for the warriors and politicians to recover from its effects.

Endnotes

- Eliot A. Cohen, Supreme Command, New York, NY: Free Press, 2002, p.15.

- Quoted in Benjamin P. Thomas and Harold M. Hyman, Stanton: The Life and Times of Lincoln’s Secretary of War, New York, NY: Knopf, 1962, p.128.

- Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder: The Committee on the Conduct of the War, Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998, p. 200.

- Thomas and Hyman, p. 262.

- Tap, p. 200.

- Elisabeth Joan Doyle, “The Conduct of the War, 1861”, in Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr. and Roger Bruns (eds), Congress Investigates, 1792–1974, New York, NY: Chelsea House Publishers, 1975, p. 73.

- David Herbert Donald, Lincoln, New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 1995, p. 285.

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1946, p. 172.

- Cohen, p. 19.

- C. Percy Powell, Lincoln Day by Day: A Chronology, 1809–1865, Volume III: 1861–1865, Washington, DC: Lincoln Sesquicentennial Commission, 1960, April 1, 1861, p. 32.

- Donald, p. 291; James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1988, pp. 267–8.

- McPherson, p. 260; Hendrick, p. 4.

- Donald, p. 256; Hendrick, p. 4; Inaugural address, available at http:whitehousehistory.org/04/subs/activities_03/c02_01.html.

- April 15, 1861, Presidential Proclamation, available at http:whitehousehistory.org/04/subs/activities_03/c02_02.html.

- Geoffrey R. Stone, Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime, New York, NY: W.W. Norton, 2004, pp. 84–5, 120 and 124.

- Stone, pp. 85, 87 and 124.

- McPherson, pp. 352–3 and 355–6.

- McPherson, p. 322.

- McPherson, pp. 333–4.

- McPherson, p. 336.

- McPherson, pp. 362–3.

- Hendrick, p. 52; Donald, p. 266.

- Harry J. Carman, and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1964, p. 148.

- Hendrick, p. 222.

- Quoted in Donald, p. 325.

- Hendrick, pp. 230–1.

- Quoted in Thomas and Hyman, p. 135.

- Quoted in Thomas and Hyman, p. 128.

- Hendrick, p. 289.

- Donald, pp. 319–20.

- Thomas and Hyman, pp. 63–6; Hendrick, pp. 257 and 259.

- Hendrick, pp. 260 and 261.

- Quoted in T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1965, p. 110.

- Thomas and Hyman, p. 155; Cohen, p. 27.

- Thomas and Hyman, pp. 152–4, 223 and 287.

- Thomas and Hyman, pp. 185 and 186.

- Thomas and Hyman, pp. 147 and 148.

- Thomas and Hyman, p. 386.

- Donald, p. 334.

- Thomas and Hyman, p. 390.

- Cohen, p. 31; Michael D. Pearlman, Warmaking and American Democracy. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1999, p. 128; Russell F. Weigley, The American Way of War, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1977, p. 134.

- Thomas and Hyman, p. 412.

- Hendrick, p. 282; William Whatley Pierson, Jr., “The Committee on the Conduct of the Civil War”, American Historical Review, vol. 23, no. 3, April 1918, pp. 556–7; Marcus Cunliffe, Soldiers & Civilians: The Martial Spirit in America, 1775–1865, Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1968, p. 329.

- The Congressional Globe, January 15, 1863, p. 324.

- Cunliffe, p. 330.

- Pearlman, p. 134.

- Tap, p. 99.

- Thomas and Hyman, p. 262.

- Quoted in Cohen, pp. 19–20.

- Cohen, pp. 15, 47 and 41.

- Cohen, p. 43.

- Cohen, pp. 39 and 40.

- Williams, p. 83; Day by Day, January 8, 1862, p. 88.

- Quoted in Day by Day, January 10, 1862, p. 89.

- Day by Day, January 13, 1862, p. 89; Williams, p. 110.

- Russell F. Weigley, A Great Civil War, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2000, p. 119; Thomas and Hyman, p. 170.

- Thomas and Hyman, p. 171.

- Quoted in Tap, pp. 112–3.

- Tap, p. 113.

- Pierson, p. 568; Day by Day, March 11, 1862, pp. 99–100.

- Quoted in Thomas and Hyman, p. 189.

- Weigley, American Way, p. 248; Pendleton Herring, The Impact of War, New York, NY: Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., 1941, pp. 151–2.

- Quoted in Thomas and Hyman, pp. 205–6.

- Tap, p. 127.

- Thomas and Hyman, pp. 217–8.

- Cohen, p. 20.

- Cohen, p. 41.

- Pearlman, p. 129.

- Thomas and Hyman, p. 299.

- Thomas and Hyman, p. 299.

- Cunliffe, p. 328; Donald, p. 491.

- Richard B. Morris, Encyclopedia of American History, New York, NY: Harper & Brothers, 1953, p. 406.

- Doyle, p. 72.

- Carman and Luthin, p. 151. The Secretary of War tried to prohibit officers from visiting Washington except on official business in 1833 but had to cancel his order. An officer in 1855 explained the siren call of the capital: “I must get to Washington & try to get promotion …. There is nothing like being on the spot”, Willliam B. Skelton, “Officers & Politicians”, reprinted in Peter Karsten (ed.), The Military in America, New York, NY: Free Press, rev. ed., 1986, p. 91.

- Williams, pp. 26 and 27; Richard H. Abbott, Cobbles in Congress: The Life of Henry Wilson, 1812–1875, Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1972, pp. 122–3.

- Abbott, pp. 126–7.

- Donald, p. 325; Abbott, p. 123.

- H. L. Trefousse, Benjamin Franklin Wade: Radical Republican from Ohio, New York, NY: Twayne Publishers Inc., 1963, p. 154.

- Tap, pp. 22–4 and 32; Pierson, pp. 555 and 558.

- T. Harry Williams, for example, says (p. 71): the JCCW “represented a full-throated attempt on the part of Congress to control the executive’s prosecution of the war.”

- Doyle, pp. 67 and 74.

- Pierson, pp. 561–3.

- Pierson, p. 569.

- Pierson, p. 573.

- Tap, pp. 200 and 34; Doyle, p. 73.

- Russell F. Weigley, History of the United States Army, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, Enlarged Edition, 1984, pp. 208 and 209.

- Allan G. Bogue, The Earnest Men: Republicans of the Civil War Senate, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1981. pp. 160–6.

- Abbott, pp. 132, 133, 135 and 138.

- Stone, p. 92.

- Weigley, Army, p. 210.

- Morris, p. 406.

- Thomas and Hyman, pp. 294–5.

- Thomas and Hyman, pp. 332–3; Pearlman, p. 140.

- Donald, p. 510; Thomas and Hyman, p. 310.

- Cohen, p. 45.

- Thomas and Hyman, pp. 525, 527, 549, 569, 573, 585, 592–3 and 608.

Chapter 3 (30-51) from Warriors and Politicians: US Civil-Military Relations under Stress, by Charles A. Stevenson (Routledge, 07.13.2006), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.