Political discourse essentially as part of a dialogue, in which rhetoric plays a crucial role.

By Dr. Stéphane Benoist

Professor of History and Archaeology

L’Université de Lille

This is a contribution about ‘an imperial discourse’ in which long-term notions of the Roman Empire in the worlds outside of that empire, and of the outside worlds from within the Roman Empire, are related to the multiple figures of the princeps. It raises diverse (Roman and alien) conceptions of the imperial power during the first five centuries of the Principate, and analyses the various messages we can find during periods of peace and war. Epigraphic, numismatic, juridical, and iconographic evidence, e.g., from the Res Gestae diui Augusti to the so-called Res Gestae diui Saporis, is used to analyse different aspects of the conception of the princeps by insiders and outsiders.1

This contribution is part of a research program which interprets the imperial identity through the various ‘forms, practices, and representations of the imperial power at Rome and in the Roman world from the beginnings to the Late Antique Empire.’ The process of construction of a discourse involving a sort of ‘double-entendre’2 (various meanings depending on diverse audiences) will be the main focus of this inquiry. It sees political discourse essentially as part of a dialogue, in which rhetoric plays a crucial role.3

This interpretation of imperial power can be illustrated through two well-known situations at the margins of the Imperium Romanum. Both deal with the apparatus of the emperor handling foreign embassies. The two examples show how, on the one hand, the image of an all-powerful Rome, which had dominated the first three centuries of the Principate, is still put forward in the second half of the third century, but contrasts sharply with testimonies produced by enemies of Rome during the second part of the 3rd, or during the 4th and 5th centuries AD.4

Dexippus, in a fragment, describes Aurelian’s negotiations with the Iuthungi, in probably 270.5 He gives us a very interesting description: the army was arranged around the prince, who was seated on a high stage, as accompanied by eikones Basileioi and gold eagles.6 Those signa and imagines were taken from the sacellum of the military camp, and were used to boost the notion of solemnity at the reception of the ambassadors of the Iuthungi. This spectacular imperial manifestation will certainly have impressed the visitors; but what was the real meaning of this staging? For whom was it primarily intended? Was it chiefly aimed at the Roman soldiers (insiders), or at the foreign ambassadors (outsiders)? Was it meant to give the Roman emperor the necessary auctoritas to maintain his power under very difficult circumstances, or did it seek to inspire awe into his enemies (the latter being the traditional interpretation of the passage)?7 The physical link that was created between the ruler (Aurelian) and his predecessors (the diui = eikones basileioi) created a concrete expression of the eternity of Rome (Roma Æterna) and of the statio principis (Æternus Augustus or perpetuus Augustus), visible to every participant in this political ritual.8

About a century later, the situation had changed profoundly. Ammianus Marcellinus gives us an account of the meeting between Athanaric’s Visigoths and the emperor Valens in order to prepare the treaty of 369. It was finally concluded in the middle of the Danube, because neither the Romans nor the Visigoths were able to convince the others to cross the river. “Because Athanaric asserted that an oath pronounced with formidable curses stopped him from ever walking on Roman ground, that his father in his recommendations had forbidden it, and that it was, moreover, impossible to oblige him to do so, and because on the other hand the emperor would have to dishonour himself and stoop to crossing the river to meet him, some counsellors with a straight judgment decided that ships should be rowed into the middle of the river, the one carrying the emperor with his guards, the other the judge of the people of this country with his own guards, to conclude the peace in the terms that had been agreed upon.”9 As a matter of fact, the weakness of the Roman Empire was demonstrated clearly, as was the importance of the physical presence of the emperor, at the Danube frontier during the second part of the 4th century AD.

In the period of time between our two introductory examples, several orators still tried to celebrate an imperium sine fine, but it no longer existed. Panegyrists may have asserted that “beyond the Rhine everything is Roman!”,10 and that “in its peaceful embrace the Roman power (Romana res publica) embraces all which, in the succession and the diversity of time, was at some moment Roman, and this greatness, which often had tottered as under an excessive weight, found its cohesion in an ultimately unshakable Empire (solido imperio).”11 However, the Pax Romana embodied by the Imperator Caesar Augustus had failed.

These two case studies illustrate the scope in which an empire made of words differed from the empire as it was experienced by contemporaries. It is worthwhile to consider this in perspective of ‘an imperial discourse,’ composed of words, monuments, and acts. This will help us to understand relationships between ‘Ours’ and ‘Theirs’, insiders and outsiders, Romans and Barbarians in the period from Augustus to Theodosius.

Following the two examples from the Rhine and Danube limites in the 3rd and the 4th centuries AD, we will further concentrate on the Oriental frontier, looking at diplomatic as well as military relationships between Romans and Parthians/Persians, from the very beginnings of the Empire onwards. Some relevant elements are already visible in the so-called “Königin der Inschriften”; the famous Res Gestae diui Augusti.12 Five passages that are important in this context deal with Armenian affairs (27.2), the recovery of military standards by Tiberius in Augustus’ name (29.2), embassies from faraway kings (31.1–2), royal fugitives and hostages (32.1–2), and finally rulers imposed by Rome to foreign kingdoms (33). They are worth quoting in full:

Although I could have made Greater Armenia a province, on the assassination of Artaxes its king, I preferred, in accordance with the example set by our ancestors, to hand this kingdom over to Tigranes, son of King Artavasdes, and also grandson of King Tigranes, through the agency of Tiberius Nero, who at the time was my stepson. And when the same people later revolted and rebelled, they were subdued through the agency of Gaius, my son, and I handed them over to King Ariobarzanes, son of Artabazus King of the Medes, for him to rule, and after his death to his son, Artavasdes; on his assassination, I sent into this kingdom Tigranes, who was descended from the Armenian royal family.13

I compelled the Parthians to give back to me spoils and standards of three Roman armies and humbly to request the friendship of the Roman people. These standards, moreover, I deposited in the innermost sanctum, which is in the temple of Mars the Avenger.14

Embassies of Kings from India were often sent to me, such as have not ever been seen before this time in the presence of any Roman general. The Bastarnae sought our friendship through envoys, and the Scythians, and kings of the Sarmatians who are on both sides of the river Don, and the king of the Albanians and of the Hiberians and of the Medes.15

Kings of the Parthians, namely Tiridates and later Phraates, son of King Phraates, Artavasdes King of the Medes, Ataxares of the Adiabenians, Dumnobellaunus and Tincomarus of the Britons, Maelo of the Sugambri, [?-]rus of the Suebic Marcomanni fled for refuge to me as suppliants. Phraates, son of Orodes, King of the Parthians, sent all his sons and grandsons into Italy to me, even though he had not been conquered in war, but asking for our friendship through pledging his children. And while I have been leader very many other peoples have experienced the good faith of the Roman people; between them and the Roman people previously no embassies or exchange of friendship has existed.16

From me the Parthian and Median peoples received kings, whom they had requested through envoys drawn from their leaders: the Parthians received Vonones, son of King Phraates, grandson of King Orodes, the Medes Ariobarzanes, son of King Artavazdes, grandson of King Ariobarzanes.17

These different passages from the RGDA are essential to understand the Roman approach to frontiers, and to notice how a specific conception of space was connected closely to the perception of imperial power (statio principis). It is worth recalling Claude Nicolet’s “inventory of the World,” which he set out in an essay published in 1988 in French and then in 1991 in English, in which he linked the evolution from a closed to an open space to how new provinces at the borders of the empire could be understood as sorts of “new frontiers.”18 We may underline how we can analyse the Augustan monument in that perspective to show what were the main processes that were brought into play.

It is not necessary to re-open the uexata quaestio about the true meaning of the provincial copies of the RGDA, nor about the idea of a proper adaptation of the text to this specific Galatian context, through for example the use of an appendix.19 More important for the purposes of this paper are the circumstances in which the original text was read out publicly by Tiberius, in his role as imperial successor, followed in this by his son Drusus, who read out the major part of this Augustan auto-evaluation.20 The new princeps, reading an evaluation of Augustus’ works written by himself, was in this way obliged to publicly respect the main recommendations of his father. Delivering as a speech this Augustan rewriting of the history of Rome, from the civil wars to the last months of his life, in front of sons and nephews of Republicans and Antonians, was a true political ritual.21 Tiberius was still under the control of the late pater patriae, his adoptive father, who had held patria potestas over him until he died. Personal relationships and the broad outline of Augustus’ politics, the text suggested, should be respected by Tiberius. This very long text could be considered as a form of mandata by the dead emperor (now diuus) to his adoptive son, who had been his legatus during the last period of Augustus’ principate.

Performing this act of pietas was a political necessity for Tiberius in the summer of 14 AD (from the 19th of August to the 23rd of September); it presents us with a few lessons: crucial is the personalization of the accounts in the RGDA of political and diplomatic decisions. As is well known, only very few names are mentioned in the text, except the regular presence of Augustus’ sons,22 and of the kings of Armenia and Parthia.23 The personal relationships between the late Roman emperor and foreign kings are clearly expressed through embassies (ad me / a me), and by the regular mention of the amicitia. This will be a permanent structure within Roman imperial history—from the beginnings of the Imperium Romanum with the Republican magistrates to the late Antiquity—.24 It is enough to quote the end of RGDA’s chapter 32.3:

“And while I have been leader very many other peoples have experienced the good faith of the Roman people (p(opuli) Ro]m(ani) fidem me principe); between them and the Roman people previously no embassies or exchange of friendship (legationum et amicitiae [c]ommercium) has existed.”

Tiberius was forced to accept, through his extensive public reading of the RGDA in the Curia, the Augustan conception of power within and outside of the empire. This applied to power structures between the senate, the people and the princeps in Rome, but also with foreign kings across the frontiers. During the first century of the Principate, these power relations formed the basis of what became a stereotypical discourse to divide between good and bad emperors, making use of private and public behaviour and focusing on the functioning of the domus Augusta.25 The portrait of a good ruler could be sketched by portraying how the Roman Empire functioned. An important role was played by looking at the Parthian counterpart to the Roman Empire, and at Armenia placed between these superpowers. There were many family connections and specific mandates for members of the imperial family—Tiberius, Caius, Germanicus, as potential heirs—regarding Armenian and Parthian successions. In that perspective, we can find a genuine Roman ‘Parthian’ discourse that lays behind the notion of a princeps Parthicus, from Trajan to Lucius Verus, and finally Septimius Severus.

The conception of the Roman Empire, between an image of a “coherent geographical and strategic entity bounded by three great rivers: Rhine, Danube and Euphrates”26 and the ideology of permanent conquest, could be studied through various portraits of emperors. Of particular interest are pairs of Imperatores Caesares Augusti, that show us contrasting views of the Imperium Romanum (Augustus-Tiberius, Trajan-Hadrian, etc.). From Fronto to the Historia Augusta, the complicated “Parthian” question figures prominently in literary evidence showing a strictly Roman “imperial” point of view, e.g., the different attitudes that Roman rulers held regarding peace and war. From Augustus to the 3rd century AD, one can see the development of a rhetorical process, in which two different imperial identities are contrasted: the idealized p(ius) f(elix) <semper> inu(ictus) emperor, with an impressive titulature, from the last Antonines to Constantine, versus a stereotypical tyrant.27

An important aspect of this rhetorical process is presented by the modes to delegitimize an emperor. These can be traced by a precise analysis of the varying rhetoric within our textual and material evidence, literary as well as epigraphic, from Cicero to the Historia Augusta.28 Sometimes, we can find elaborate rhetorical strategies to put forward different portrayals of ruling emperors, or to contrast different members of the domus Augusta.

Two well-known examples may be mentioned: they both use the Parthian/Persian war and the foreign king as an enemy, in order to contrast imperial behaviour. According to Fronto, who wanted to give advice to his pupil Marcus Aurelius, who according to him had a too much philosophical mind, Lucius Verus behaved better than Trajan during his Parthian campaign: “Lucius, on account of the ingenuity of his advice, is by far the elder of Trajan;”29 Verus sent a letter to his enemy, Vologaeses, offering him peace. He thus cared for the safety of his soldiers, and preferred peace to vainglory, whilst avoiding any treachery.30 We may be surprised to find Lucius Verus, who is regularly portrayed as a debauchee, as the ideal prince in Fronto’s epistula:

“Lucius bears a great reputation of justice and leniency among the Barbarians; Trajan was not equally innocent for all. Nobody has regretted placing his kingdom and fortune under Lucius’s protection.”31

This ‘reversed’ portrait of Lucius might have been written in anticipation of the younger imperator’s journey back to Rome, and of his upcoming aduentus and triumphus. As Parthicus, Lucius Verus could be celebrated like a ‘good prince.’32

One of the most important aspects of the Roman commemorative identities that took shape in the Augustan Principate was linked to the return to peace (a verbal discourse in Virgil’s Aeneid) and to the celebration of diplomatic conquest over the Parthian empire by the recovery of Crassus’s lost standards (a monumental discourse through the Parthian Arch in the forum Romanum, and the statue of Prima Porta). The recurrent Parthian wars could be used to demonstrate the uirtus and the fortuna of any emperor. Yet, as we have seen, it was possible to completely inverse the ‘normal’ perspective and describe Trajan as full of treachery and cruelty towards the Parthian and Armenian kings, whilst Lucius Verus became a good soldier and a general who took care of his legionaries. Consequently, we can argue that the official conception of an empire ab origine rests on a rhetorical construction that diffused inside and outside mes-sages through an imperial stereotypical portrait.

A century later, we find another piece of evidence for this imperial discourse: the portrait of Gallienus, son of the defeated emperor Valerian, who was captured by Shapur. Gallienus is usually condemned by the senatorial historiography for his edictum on military careers and the government of imperial provinces.33 In the vita written by the author of the Historia Augusta, the legitimate emperor is condemned as a tyrant, a mollis, while Odaenathus from Palmyra—and to an extent also his wife Zenobia, whose description is ambiguously positive, and shows noble courage and virility34—became the protector of the pars Orientalis of the empire. He defended the Roman territory facing Sapor, and his “sole purpose was to set Valerian free” while the official ruler Gallienus “was doing nothing at all”.35

Romano-Parthian or Persian relationships have been an essential part of the process of constructing an imperial identity from Augustus to Gallienus. The recovery of military standards by Tiberius was celebrated to commemorate the revenge over Crassus’s defeat. This became a fundamental act for the Augustan time (the conditio of a new era). The message that was transmitted through the ‘Power of Images’ (to cite Zanker) included references to this revenge in the statue of Prima Porta, or Virgil’s Aeneid, Horace’s Carmen Saeculare, and Ovid’s Fasti.36 More than a century later, Trajan became the first emperor to be (posthumously) named diuus Traianus Parthicus, and coin types support the idea that there was a representation of a statue in a chariot with the legend Triumphus Parthicus. It would have been impossible to stage a posthumous triumphus, but an aduentus of the image of a ‘diuus Traianus Parthicus’ may have been an adequate ceremony for Hadrian to celebrate his predecessor’s victory and mark the return of his ashes.37 The Severan campaign against the Parthians was a decisive element of the new dynastic promotional programme, during the years 195–198. It allowed the new fam-ily to emphasis imperial continuity, which was celebrated by coins noting the laetitia temporum or the felicitas saeculi as well as the æternitas imperii. The same themes were developed afterwards in association with the decennalia, Caracalla’s wedding and the preparation of the ludi saeculares.38 Making use of a recognised imperial discourse allowed the Severan principate to legitimize itself through close connection to the glorious past. Thus, a link to Trajan was made by celebrating the Severan victory over the Parthians in 198, and by associating this to the elevation to power of a son by his father (Caracalla by Septimius Severus). According to the Feriale Duranum, Trajan, the Parthian victor, became sole emperor on the 28th of January 98, exactly a century earlier.39

In 260, in contrast, the defeat of Valerian and his humiliating captivity were surely a symbolic nightmare, and a major disadvantage for his son Gallienus in maintaining his power and ensuring legitimacy. We should, in that perspective, consider Odaenathus’ legatio40 as a sensible decision by an emperor who was confronted with a process of dissolution of the unity of his empire (from West to East, from the so-called Gallic empire to the Palmyrian kingdom).41

The imperial discourse considers the conception of a territorial empire, such as the statio principis, as a double-mirror, which can be appropriated into a rhetoric construction about good and bad emperors. In the perspective of such a construction of a collective and personal identity, created from res gestae and personae, imperial titulatures can be analysed as a way to define the Imperium Romanum as a space; a process of transformation of territories by the Roman army or after diplomatic agreements; and as a means to think about a universal city embodied by its princeps.42 A few documents support the main arguments.

The first example may be useful to understand how the personal identification of emperors in standard formulations like legati Augusti pro praetore—of which there remain sixty cases within around two thousands inscriptions—was usually linked to special situations.43 These were the participation in military campaigns alongside the prince (as amicus or / and comes), the creation of new provinces, or control over ad hoc associations of several provinces, diplomatic missions, etc.44 An anonymous cursus honorum from Heliopolis provides an excellent example of such close connections between emperors and legati, in this case during the successive campaigns of Trajan in Dacia and Parthia.45

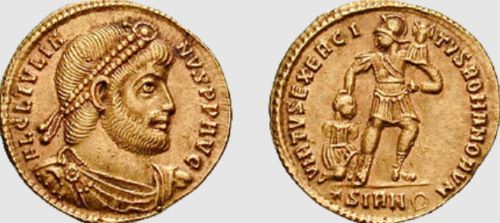

The cognomina deuictarum gentium46 can be understood as a perception of what was considered ‘becoming Roman’ in the perspective of military campaigns and the ensuing process of provincialization. We can illustrate that process through the examples of Septimius Severus’ and Julian’s cogno-mina (Arabicus, Adiabenicus and Parthicus Maximus, Alamanicus Maximus, Francicus Maximus and Sarmaticus Maximus).47 One very interesting aspect about our main focus of attention, the Parthian/Persian affairs, is the concomitant use of the cognomina Parthicus and Persicus during the 3rd century AD. In that period, it was possible to use those two cognomina in different perspectives: in memoriam of the glorious past embodied by the good emperors Trajan or Septimius Severus, and as a contemporary reference to present circumstances. From the 220’s onwards, after all, Sassanids conquered power and became an aggressive enemy, which formed the main risk for the Roman Empire.48 A victory over the Persians, henceforth, could be celebrated as either a clear reference to Persian ethnical identity (i.e. the new dynastic power in charge of that region), or to recall past glory. A few decades later, Numerian’s inscriptions should be reconsidered by analysing their use of Parthicus Maximus/Persicus Maximus in the forms. Perhaps we can even rehabilitate his reign, and especially his Persian campaign and the last fifteen months of Numerian’s life, if we combine an African inscription, coins, a papyrus and a passage from Nemesianus’ Cynegetics.49

The permanence of the imperial identity as expressed through references to the power of the princeps and the ways in which he was commemorated becomes clear from an example at the very end of our period of study, during the 4th and the 5th centuries AD. Constantine was celebrated as the Maximus uictor (after he had abandoned the title inuictus) ac triumfator semper Augustus.50 He was, as far as we trust the evidence, the first emperor with nine cognomina: Germanicus, Armeniacus and Medicus Maximus, as well as Sarmaticus Maximus, Arabicus Maximus and Persicus Maximus, and finally Britannicus Maximus, Carpicus Maximus and Gothicus Maximus.51 For Julian, the fundamental link between the emperor, the Imperium Romanum as a territory, and the ‘Others’, is acutely expressed in a Palestinian text: the emperor is celebrated as the Romani orbis liberator, the barbarorum extinctor and a perpetuus Augustus.52 The princeps is naturally the protector of the empire and its inhabitants, and, in doing so, he has to reply to any request. In this he was like he was described in the adsertio of the magister militum Orientis Anatolius in 438 AD, who considered that soldiers should not be disturbed by civilian accusations. Theodosius II responded to the praefectus praetorio Orientis Florentius in a mostly rhetorical answer about those limitanei milites (in extrema parte Romani saeculi), whose life was difficult and whose duty towards the Res publica was essential, even if the Sassanid threat was real but the direct conflicts between Romans and Persians very rare under this reign.53

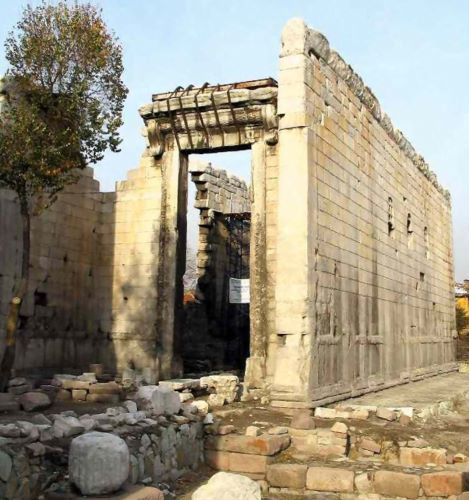

The main argument developed above about a Roman imperial discourse, and the identity of the Roman Empire and its princeps through the perception of Others in a few documents from Augustus to Theodosius II, is essentially dependent on ‘Roman’ evidence, even if there is some evidence for neighbours’ voices, e.g. Parthian ones. This is why this paper now ends with reference to a last piece of evidence, the Inscription of Shapur I at Naqsh-e Rustam, near Persepolis. I am, by no means, a specialist of medium-Persian or Parthian languages. My knowledge is based on secondary literature, from André Maricq to Richard Frye or Philip Huyse.54 A few years ago regular seminars about the 3rd century AD were held at the Sorbonne (Centre Gustave-Glotz). In these seminars, the late Xavier Loriot and Philip Huyse proposed a very interesting form of communication, combining two voices from two different perspectives: Roman history and Persian philology and linguistic, about the Roman contingents during the third Sasanid campaign against Valerian.55

Two brief remarks to conclude. Firstly, this so-called Res Gestae diui Saporis,— the name of which is surely a miscomprehension of the document,56 even if the inscription, post-Maricq, has been seen as a kind of 3rd-century parallel of the RGDA,— is essential to understand the Persian version of Valerian’s defeat in 260. It gives a precise description of the Persian Empire, beginning with a complete list of lands under the rule of Shapur (ŠKZ I §2–5). Then, it mentions the three Roman emperors, Gordian III, Philip and Valerian, and their “deeds” related to Persia (maybe there is some sort of irony in the presentation of those events) (ŠKZ I §6–30). This monumentum can be understood as a triumphal assertion about an empire, its ruler, and his actions under the protection of Mazda.57 If we want to propose a true Roman parallel, the same elements of self-confidence in an ever glorious power can be found in the triumphal ceremonies at Rome: processions of the armies, tituli and pictures to tell the story of the campaigns and statues to celebrate the permanent victor (even if the laudationes funebres could be interpreted in the same framework). These ceremonies formed a more comprehensive exhibition, combining words, rituals and monuments.

Secondly, the elements of the Roman imperial discourse which this paper discusses, from the RGDA and various imperial titulatures to literary texts, all incorporate references to enemies to formulate the princeps’ identity. They belonged to a set of notions which together shaped the Roman imperial res publica. We can assume that some of those texts pertained to political rituals, which were supposed to define the empire and its ruler through collective commemoration: Tiberius in the Senate reading the Res Gestae of his father, publicly formulating an account that defined the political agenda, and the nature of the statio principis; or any emperor responding to petitions in his chancellery. The Principate needed to find a public expression that could be accepted by the SPQR. The discourse in which ‘Others’ figured prominently—or in which their image was reconstructed—was essential to define the nature of the Principate.58

Endnotes

- For a few preliminary aspects about the frontiers of the Roman Empire and the conception of imperial power: Stéphane Benoist, ‘Penser la limite: de la cité au territoire impérial’, in Olivier Hekster and Ted Kaizer (eds.), Frontiers in the Roman World, Proceedings of the Ninth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire (Durham, 16–19 April 2009), (Leiden/Boston 2011), 31–47.

- About ‘double-entendre’ and the nature of a ‘subtext,’ see Stéphane Benoist, ‘Fragments de mémoire, en quête de paroles condamnées’, in Bénédicte Delignon and Yves Roman (eds.), Le Poète irrévérencieux. Modèles hellénistiques et réalités romaines, collection du CEROR 32 (Paris 2009), 49–64, for a general overview.

- E.g. Stéphane Benoist, ‘Identité(s) du prince et discours impérial, l’exemple des titulatures, des Sévères à Julien’, in Moïra Crété (ed.), Discours et systèmes de représentation: modèles et transferts de l’écrit dans l’Empire romain (Besançon 2016) forthcoming; and the conclusion of the same volume: Id., ‘Miroir des princes et discours d’éloge, quelques remarques conclusives’; Id., ‘Rhétorique, politique et pratique épigraphique monumentale’, Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz 25 (2014), 209–214.

- See the accurate inquiry by Audrey Becker, Les relations diplomatiques romano-barbares en Occident au Ve siècle. Acteurs, fonctions, modalités (Paris 2013) on this radical change of perspectives from a conquering Rome to a much more disputed situation.

- Jacoby FGRH II.A = Dex., Frag. 6.3.

- For a commentary about ‘the images of emperor and empire’ citing this testimony (i.e. Excerpta de legationibus, Dexippus 1 de Boor [FHG fr. 24 = Dindorf, HGM fr. 22]), see Clifford Ando, Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire (Berkeley 2000), 263.

- E.g. Ando 2000, 263: “On the appointed day, the emperor ordered the legions to assemble as if for battle, to terrify the enemy (. . .) Aurelian’s preparations were successful: the Juthungi, we are told, were stunned and remained silent for a long time.”

- See Stéphane Benoist, ‘Images des dieux, images des hommes. Réflexions sur le ‘culte impérial’ au IIIe siècle’, in Marie-Henriette Quet (ed.), La “crise” de l’empire romain de Marc Aurèle à Constantin (Paris 2006), 27–64: the display of imagines of deceased emperors, probably the diui, reminds us of Decius’ use of a monetary series of diui from Augustus onwards. The conception of the Eternity of the Empire and the emperor was central from the very beginning of the Principate, but increasingly became so during the 3rd century AD: Stéphane Benoist, Rome, le prince et la Cité. Pouvoir impérial et cérémonies publiques (Ier siècle av.–début du IVe siècle ap. J.-C.), collection Le Nœud Gordien (Paris 2005), chapters VII–VIII, 273–333.

- Amm. Marc. XXVII.5.9: et quoniam adserebat Athanaricus sub timenda exsecratione iurandi se esse obstrictum, mandatisque prohibitum patris ne solum calcaret aliquando Romanorum, et adigi non poterat, indecorumque erat et uile ad eum imperatorem transire, recte noscentibus placuit, nauibus remigio directis in medium flumen, quae uehebant cum armigeris principem gentisque iudicem inde cum suis, foederari, ut statutum est, pacem. Becker 2013, op. cit. (n. 4), quotes this passage in her introduction (15–16), underlining the symbolic aspect of the Danube as an appropriate space belonging to nobody, neither the Romans, nor the Visigoths.

- Mamertinus, Maximiano Augusto, Pan. 10 [II].7.7: quidquid ultra Rhenum prospicio, Romanum est.

- Constantio Caesari, Pan. 8 [V].20.2: Tenet uno pacis amplexu Romana res publica quidquid uariis temporum uicibus fuit aliquando Romanum, et illa quae saepe ueluti nimia mole dif-fluxerat magnitudo tandem solido cohaesit imperio.

- Th. Mommsen, ‘Der Rechenschaftsbericht des Augustus’, in Gesammelte Schriften IV (Berlin 19062 [1887]), 247.

- RGDA 27.2: Armeniam maiorem interfecto rege eius Artaxe, c[u]m possem facere prouin-ciam, malui maiorum nostrorum exemplo regn[u]m id Tigrani, regis Artauasdis filio, nepoti autem Tigranis regis, per T[i(berium) Ne]ronem trade[r]e, qui tum mihi priuignus erat. et eandem gentem postea d[e]sciscentem et rebellantem domit[a]m per Gaium filium meum regi Ariobarzani regis Medorum Artaba[zi] filio, regendam tradidi, et post eius mortem filio eius, Artavasdi; quo [i]nterfecto Ti[gra]ne<m>, qui erat ex regio genere Armeniorum oriundus, in id regnum misi. Four editions of the Res Gestae Diui Augusti (RGDA) have been published recently: John Scheid, Res Gestae Diui Augusti. Hauts faits du divin Auguste, CUF-Les Belles Lettres (Paris 2007); the English translation follows Alison E. Cooley, Res Gestae Divi Augusti (Cambridge 2009); Stephen Mitchell, David French, The Greek and Latin Inscriptions of Ankara (Ancyra). Vol. I: From Augustus to the end of the third century AD, Vestigia 62 (Munich 2012); and Augusto, Res gestae. I miei atti, a cura di Patrizia Arena, Documenti e studi 58 (Bari 2014).

- RGDA 29.2: Parthos trium exercit<u>m Romanorum spolia, et signa re[ddere] mihi sup-plicesque amicitiam populi Romani petere coegi. ea autem si[gn]a in penetrali, quod e[s]t in templo Martis Vltoris reposui.

- RGDA 31: 1. ad me ex In[dia regum legationes saepe] m[issae sunt non uisae ante id t]em[pus] apud qu[em]q[uam] R[omanorum du]cem. 2. nostram amic[itiam appetiue]run[t] per legat[os] B[a]starn[ae Scythae]que et Sarmatarum qui su[nt citra fl]umen Tanaim et ultra re[ges, Alba]norumque rex et Hiberorum e[t Medorum].

- RGDA 32: 1. ad me supplices confugerunt [r]eges Parthorum Tirida[te]s et post[ea] Phrat[es], regis Phratis filiu[s], Medorum Ar[tauasdes, Adiabenorum A]rtaxares, Britann[o]rum Dumnobellaunus et Tin[comarus, Sugambr]orum Maelo, Mar[c]omanorum Sueborum [ . . . rus]. 2. ad [me re]x Parthorum Phrates, Orod[i]s filius, filios suos nepot[esque omnes] misit in Italiam non bello superatu[s], sed amicitiam nostram per [libe]ror[um] suorum pignora petens. 3. plurimaeque aliae gentes exper[tae sunt p(opuli) Ro]m(ani) fidem me principe, quibus antea cum populo Roman[o nullum extitera]t legationum et amicitiae [c]ommercium.

- RGDA 33: a me gentes Parthorum et Medoru[m per legatos] principes earum gentium reges pet[i]tos acceperunt: Par[thi Vononem, regis Phr]atis filium, regis Orodis nepotem, Medi Arioba[rzanem], regis Artavazdis filium, regis Ariobarzanis nepotem.

- Claude Nicolet, L’inventaire du monde. Géographie et politique aux origines de l’Empire romain (Paris 1988 [2e éd. 1996]); Space, geography, and politics in the early Roman empire, Thomas Spencer Jerome Lecture 19 (Ann Arbor 1991).

- The main aspects of the epigraphic survival of the text through Anatolian copies (in Ancyra, Pisidian Antioch, and Apollonia) are developed by Cooley 2009, op. cit., esp. 6–22, and Scheid 2007, op. cit., IX–XIII; XVII–XXI; XXIX–XXXIV, in their editions of the RGDA(n. 13). Cf. P. Thonemann, ‘A Copy of Augustus’ Res Gestae at Sardis’, Historia 61.3 (2012), 282–288, and Arena 2014, op. cit., 14–15, for an Asian copy of the text discovered in Sardis and the consequences of this find for the different attested Greek translations.

- Cf. Suet., Aug., 101.1: Testamentum L. Planco C. Silio cons. III. Non. Apriles, ante annum et quattuor menses quam decederet, factum ab eo ac duobus codicibus, partim ipsius partim libertorum Polybi et Hilarionis manu, scriptum depositumque apud se uirgines Vestales cum tribus signatis aeque uoluminibus protulerunt. Quae omnia in senatu aperta atque recitata sunt; 6, Tribus uoluminibus, uno mandata de funere suo complexus est, altero indicem rerum a se gestarum, quem uellet incidi in aeneis tabulis, quae ante Mausoleum statuerentur, tertio breuiarium totius imperii, quantum militum sub signis ubique esset, quantum pecuniae in aerario et fiscis et uectigaliorum residuis; and Tib., 23 (discourse by Tiberius and reading of Augustus’ will); Dio Cass., 56.33.

- About this specific dimension and its impact on the normative processes of imperial power, see Stéphane Benoist, ‘Noms du prince et fixation de la norme: praescriptio / inti-tulatio, subscriptio . . .’, lecture delivered at the Institut de droit romain in Paris (22.3.2013) to be published by the Revue historique de droit français et étranger.

- Cf. RGDA 8.4: conlega Tib(erio) Cae[sare filio] m[eo; 12.2: Ti(berio) Nerone . . . cos; 14.1: [ fil]ios meos . . . Caium et Lucium Caesares; 16.2: Ti(berio) Nerone . . . consulibus; 20.3: filio-rum m[eorum; 22.1: filiorum meorum aut n[e]potum nomine; nepo[tis] mei nomine; 22.3: filio[ru]m meorum et nepotum; e.g., about Armenia, 27.2: per T[i(berium) Ne]ronem . . . qui tum mihi priuignus erat / per Gaium filium meum; 30.1: per Ti(berium) [Ne]ronem, qui tum erat priuignus et legatus meus.

- Artaxes, Artavasdes, Tigranes, Ariobarzanes with Artavasdes of the Medes in RGDA 27.2; Tiridates, Phraates, in RGDA 32.1–2 with other kings, and in RGDA 33. See Mario Pani, Roma e I re d’Oriente da Augusto a Tiberio (Cappadocia, Armenia, Media Atropatene) (Bari 1972), chapter I “Lotte dinastiche per l’Armenia e ‘reges dati’ in eta’ augustea,” 15–64; Richard D. Sullivan, Near Eastern Royalty and Rome, 100–30 BC (Toronto 1990), 290–291 (Artaxias II), 297–300 (Artavasdes I), 313–318 (Phraates IV); and Marie-Louise Chaumont, ‘L’Arménie entre Rome et l’Iran I. De l’avènement d’Auguste à l’avènement de Dioclétien’, ANRWII.9.1 (1976), 73–84 (“La politique d’Auguste en Arménie”).

- Cf. RGDA 31–33. About the conception of a Roman diplomacy through the relationships between the emperors and the members of their family (domus Augusta), Stéphane Benoist, ‘Les membres de la domus Augusti et la diplomatie impériale. À propos de l’empire et des “autres” ’, in Audrey Becker and Nicolas Drocourt (eds.), Ambassadeurs et ambassades au cœur des relations diplomatiques, Rome—Occident médiéval—Byzance (VIIIe s. avant J.-C.–XIIe s. après J.-C.), collection du CRULH 47 (Metz 2012), 65–81. Note how 4th-century letters between Constantine or Constantius and Shapur II confirm permanent diplomatic activities between emperors and foreign kings: Eusebius, Vita Constantini, 4.9–13 (letter in Latin translated in Greek by Eusebius from Constantine to Shapur), and Ammianus Marcellinus, 17.5 Constantius Aug. et Sapor Persarum rex frustum de pace per lit-teras et legatos agunt (with two examples of letters from an exchange between Constance and Shapur: 3. Rex regum Sapor, particeps siderum, frater Solis et Lunae, Constantio Caesari fratri meo salutem plurimam dico; 10. Victor terra marique Constantius, semper Augustus, fratri meo Sapori regi salutem plurimam dico); two pieces of evidence quoted by Fergus Millar, ‘Emperors, Frontiers, and Foreign Relations, 31 B.C. to A.D. 378’, Britannia 13 (1982), 1–23 = Hannah M. Cotton, Guy M. Rodgers (eds.), Government, Society, and Culture in the Roman Empire, vol. 2 of Rome, the Greek World, and the East (Chapel Hill and London 2004), 160–194 (at 162).

- Benoist 2012, op. cit. (n. 24).

- Cf. Fergus Millar’s seminal essay about ‘Emperors, Frontiers, and Foreign Relations’, published in 1982 (op. cit. n. 24), 188, with references to Strabo, Velleius, Josephus, Statius, Tacitus, and Suetonius.

- On the use of tyranus as a term to describe any illegitimate princeps, bad ruler, or usurper: Stéphane Benoist, ‘Usurper la pourpre ou la difficile vie de ces autres “principes” ’, in Stéphane Benoist and Christine Hoët-van Cauwenberghe (eds.), La vie des autres. Histoire, prosopographie, biographie dans l’Empire romain, collection Histoire et civilisations (Villeneuve d’Ascq 2013), 37–61.

- On the various perceptions of an imperial discourse and its own processes of com-memoration and denigration of emperors: Stéphane Benoist, ‘Cicéron et Octavien, de la res publica au princeps, lectures croisées’, in Robinson Baudry and Sylvain Destephen (eds.), La société romaine et ses élites. Hommages à Élizabeth Deniaux, (Paris 2012), 25–34; Id., ‘Honte au mauvais prince, ou la construction d’un discours en miroir’, in Renaud Alexandre, Charles Guérin and Mathieu Jacotot (eds.), Rubor et Pudor. Vivre et penser la honte dans la Rome ancienne, Études de littérature ancienne 19 (Paris 2012), 83–98; Id., ‘Le prince nu. Discours en images, discours en mots. Représentation, célébration, dénoncia-tion’, in Valérie Huet and Florence Gherchanoc (eds.), Vêtements antiques. S’habiller et se déshabiller dans les mondes anciens (Paris 2013), 261–277; and finally Id., ‘Trahir le prince: lecture(s) de l’Histoire Auguste’, in Anne Queyrel Bottineau, Jean-Christophe Couvenhes and Annie Vigourt (eds.), Trahison et traîtres dans l’Antiquité, collection De l’archéologie à l’histoire (Paris 2013), 395–408.

- M. Cornelius Fronto, Epistulae, ed. Michael Petrus Josephus Van den Hout, Teubner (Leipzig 19882), 202–214 (Principia historiae), with Van den Hout’s accurate commentary in A commentary on the letters of Marcus Cornelius Fronto (Leiden/Boston 1999), 463–487. Principia historiae 16 (<. . .> Lucius consiliorum sollertia longe esse Traiano senior <. . .>).

- Fronto, Principia historiae 16–17: recte res gesta: paucis ante diebus L<uciu>s ad Vologaesum litteras ultro dederat, bellum, si uellet, condicionibus poneret. Dum oblatam pacem spernit barbarus, male mulcatus est. 17. Ea re dilucide patet, quanta Lucio cura insita sit militum salutis, qui gloriae suae dispendio redimere cupiuerit pacem incruentam. Traiano suam potiorem gloriam in sanguine militum futuram de ceteris eius studiis multi coniectant; nam saepe Parthorum legatos pacem precanteis dismisisse inritos.

- Idem 18: Iustitiae quoque et clementiae fama apud barbaros sancta de Lucio; Traianus non omnibus aeque purgatus. Regnum fortunasque suas in fidem Luci contulisse neminem paenituit.

- Note the equally surprising negative description of Trajan in the episode of Parthamasiris’ murder as narrated by Fronto in his Principia historiae 18: Traiano caedes Parthamasiri regis sup<p>licis haud satis excusata. Tametsi ultro ille uim coeptans tumultu orto merito interfectus est, meliore tamen Romanorum fama impune supplex abisset quam iure supplicium luisset, namque talium facinorum causa facti latet, factum spectatur, longeque praestat secundo gentium rumore iniuriam neglegere quam aduerso uindicare. “the murder of Parthamasiris, a pleading king, was not enough justified by Trajan. Although he had deserved to be killed, because he had begun on his own initiative the violence at the origin of the disorders, it would have been however preferable for the Roman reputation to let a supplicant leave without any damage rather than to chastise him, because the reasons of such a crime remain obscure: we see only the action, and it is by far prefer-able to neglect an insult with the public approval that to take revenge of it in the general disapproval.” On Armenia under Trajan’s rule and its annexation, Chaumont 1976, op. cit. (n. 23), 130–143.

- See Lukas de Blois, The policy of the emperor Gallienus (Leiden 1976), 57–83, especially 78–80: “The hatred of senators for Gallienus and the emperor’s bad name among Latin historians”; and Michel Christol’s abstract of his unpublished thesis ‘L’État romain et la crise de l’empire (253–268)’, L’Information historique 44 (1982), 156–163, with ‘Armée et société politique dans l’Empire romain au IIIe siècle ap. J.-C.’, Civiltà classica e cristiana 9 (1988), 169–204.

- On the impossibility of a feminine imperium and the use of this topos in our literary evidence, Stéphane Benoist, ‘Women and Imperium in Rome. Some imperial perspectives’, in Jacqueline Fabre-Serris and Alison Keith (eds.), Women and War in Antiquity ( Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 2015), 266–288.

- For this stereotypical vision of Gallienus facing Odenathus in the Historia Augusta: Gall., X, 1. Gallieno et Saturnino conss. Odenatus rex Palmyrenorum optinuit totius orientis imperium, idcirco praecipue, quod se fortibus factis dignum tantae maiestatis infulis declarauit, Gallieno aut nullas aut luxuriosas aut ineptas et ridiculas res agente. 2. Denique statim bellum Persis in uindictam Valeriani, quam eius filius neglegebat, indixit. 3. Nisibin et Carras statim occupat tradentibus sese Nisibenis atque Carrenis et increpantibus Gallienum. 4. Nec defuit tamen reuerentia Odenati circa Gallienum; nam captos satrapas insultandi prope gratia et ostentandi sui ad eum misit. (. . .) 6. Odenatus autem ad Ctesifontem Parthorum multitudinem obsedit uastatisque circum omnibus locis innumeros homines interemit. 7. Sed cum satrapae omnes ex omnibus regionibus illuc defensionis communis gratia conuolassent, fuerunt longa et uaria proelia, longior tamen Romana uictoria. 8. Et cum nihil aliud ageret nisi ut Valerianum Odenatus liberaret, instabat cottidie, ac locorum difficultatibus in alieno solo imperator optimus laborabat. “In the consulship of Gallienus and Saturninus Odaenathus, king of the Palmyrenes, held the rule over the entire East chiefly for the reason that by his brave deeds he had shown himself worthy of the insignia of such great majesty, whereas Gallienus was doing nothing at all or else only what was extravagant, or foolish and deserving of ridicule. Now at once he proclaimed a war on the Persians to exact for Valerian the vengeance neglected by Valerian’s son. He immediately occupied Nisibis and Carrhae, the people of which surrendered, reviling Gallienus. Nevertheless, Odaenathus showed no lack of respect toward Gallienus, for he sent him the satraps he captured though, as it seemed, merely for the purpose of insulting him and displaying his own prowess. (. . .) Odaenathus, besides, besieged an army of Parthians at Ctesiphon and devastated all the country round about, killing men without number. But when all the satraps from all the outlying regions flocked together to Ctesiphon for the purpose of common defence, there were long-lasting battles with varying results, but more long-lasting still was the success of the Romans. Moreover, since Odaenathus’ sole purpose was to set Valerian free, he daily pressed onward, but this best of commanders, now on a foreign soil, suffered greatly because of the difficult ground” (English translation, ed. Loeb, David Magie).

- Cf. Paul Zanker, The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus (Ann Arbor 1988), 167–238, and Karl Galinsky, Augustan Culture. An Interpretive Introduction (Princeton 1996), 10–41. The links asserted there with the Auctoritas have been recently discussed by Gregory Rowe, ‘Reconsidering the Auctoritas of Augustus’, Journal of Roman Studies 103 (2013), 1–15.

- Benoist 2005, op. cit. (n. 8), 236–239 (about the pseudo-triumphus Parthicus), and 150–156 (the distinction between funus and consecratio); contra Javier Arce, ‘Muerte, consecratio y triumfo del emperador Trajano’, in Julián González (ed.), Trajano emperador de Roma (Rome 2000), 55–69; and recently ‘Roman imperial funerals in effigie’, in Björn C. Ewald and Carlos F. Noreña (eds.), The Emperor and Rome. Space, Representation, and Ritual (Cambridge 2011), 309–324.

- Benoist 2005, op. cit. (n. 8), 71–74 (about the adventus), 284–288 (the ludi saeculares), and 307–308 (the Eternity theme with the coins of plate IIIb about Aeternitas under the Severan emperors).

- Cf. Feriale Duranum, I, 14–16 : (a. d.) V. K[a]l. [ feb]rarias ob V[i]ctori[as— et Parthica]m Maxi/m[a]m diui Seue[ri e]t ob [imperium diui Traiani uictoriae part]hic[a]e / b(ouem) [ f. d]iuo Traian[o b. m. For a brief presentation, Stéphane Benoist, ‘Le Feriale Duranum’, in Antoine Hermary and Bertrand Jaeger (eds.), Thesaurus Cultus et Rituum Antiquorum (ThesCRA), VII. Festivals and contests, III. “Fêtes et jeux dans le monde romain” ( J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 2011), 226–229, with bibliographical references.

- How should we understand this legatio? As an interpretatio Romana of a separate power or a real delegation by Gallienus of an Imperial authority? Cf. Stéphane Benoist, ‘Le prince et la société romaine d’empire au IIIe siècle: le cas des ornamenta’, Cahiers du Centre Gustave-Glotz 11 (2000), 309–329, using then recently discovered papyrological documentation, and the interpretation by David Potter of ‘The Career of Odaenathus’, in Prophecy and History in the Crisis of the Roman Empire. A Historical Commentary on the Thirteenth Sibylline Oracle (Oxford 1990), Appendix 4, 381–394.

- A general overview of the context by Michel Christol, L’empire romain du IIIe siècle. Histoire politique (192–325 après J.-C.) (Paris 1997), 139–162.

- On the concept of an imperial discourse through epigraphic evidence, Stéphane Benoist forthcoming, op. cit. (n. 3).

- CIL, III, 14387 d & w; IGLS, 6, 2775, Heliopolis, Syria: tri]b(uno) mi[l(itum) leg(ionis) XIIIGem(inae), III uir(o) a(uro) a(rgento) a(ere) f(lando) f(eriundo), leg(ato)] / [pro p]r(aetore) prou[inciae Cretae et Cyren(aicae), aedili] / [cur(uli) ?], praet(ori) p[eregr(ino) ?, leg(ato) Aug(usti) leg(ionis) XI Cl(audiae) p(iae) f(idelis), praepo]/[sit]o leg(ionis) IIII S[cyth(icae) b]ell[o Dac(ico) —], / [le]g(ato) pro pr(aetore) pr[oui]nc[iae Iudaeae et leg(ionis) X fret(ensis), ad]/[lect]o inter c[omite]s Au[g(usti) exped(itione) Dacic(a) II ab Imp(eratore)] / [Caes(are)] Nerua Traiano [Aug(usto) Germ(anico) Dacico Parthico, praeposi]/[to a]b eodem Imp(eratore) Parth[ico bello —] / [et] donis militar(ibus) do[nato bis ?, leg(ato) pro pr(aetore) Imp(eratoris) Caes(aris) Neruae] / [Tr]aiani Aug(usti) Germ(anici) Da[cici Parthici prouinciae Cappadociae et Galati]/[ae], item leg(ato) pro pr(aetore) eius[dem Imp(eratoris) Caes(aris) Neruae Traiani Aug(usti) prou(inciae)] / Syriae P[hoenices Commagenae huic senatus] / [c]ensuit m[aximo principe Imp(eratore) Caes(are) Nerua] / [Traiano Aug(usto) Germ(anico) Dacico Parthico auctore], / [statuam in foro Aug(usti) pecun(ia) publ(ica) ponendam].

- Stéphane Benoist, ‘Princeps et legati, de la conception impériale de la délégation de pouvoir. Nature, fonction, devenir, d’Auguste au IVe siècle de notre ère’, in Agnès Bérenger and Frédérique Lachaud (eds.), Hiérarchie des pouvoirs, délégation de pouvoir et responsabilité des administrateurs dans l’Antiquité et au Moyen Âge (Metz 2012), 135–159, on the different circumstances which explain specific formulas (with an appendix of 60 inscriptions).

- About the general context of the Trajanic Wars, see Julian Bennett, Trajan Optimus Princeps. A Life and Times (London 1997), esp. “Dacicus” and “Parthicus,” 85–103 and 183–204, with endnotes 245–250 and 269–274; and Karl Strobel, Kaiser Traian. Eine Epoche der Weltgeschichte (Regensburg 2010), “Der Weg zum Feldherrnruhm,” 218–303, and “Das Abenteuer des Partherkrieges,” 348–398.

- For a different perspective of the perpetual victory of emperors, Benoist 2005, op. cit. (n. 8), 255–265.

- For Septimius Severus, AE, 1993, 1789 = RMD, III, 189: Imp(erator) Caes(ar) diui M(arci) Antonini Pii Germ(anici) Sarm(atici) f(ilius) diui / Commodi frater diui Antonini Pii nep(os) diui Hadriani / pronep(os) / diui Traiani Parth(ici) abnep(os) diui Neruae adnep(os) / L(ucius) Septimius Seuerus Pius Pertinax Aug(ustus), Arab(icus) Adiab(enicus) Par/thic(us) max(imus), pontif(ex) max(imus), trib(unicia) potest(ate) XIIII, imp(erator) XIII, co(n)s(ul) III, p(ater) p(atriae), proco(n)s(ul), / Imp(erator) Caesar Luci Septimi Seueri Pii Pertin(acis) Aug(usti) Arab(ici) / Adiab(enici) Parth(ici) max(imi) f(ilius) diui M(arci) Antonini Pii Germ(anici) Sarm(atici) / nep(os) diui Antonini Pii pronep(os) diui Hadriani abnep(os) / diui Traiani Parth(ici) et diui Nervae adnep(os) / M(arcus) Aurellius Antoninus Pius Aug(ustus), tr(ibunicia) pot(estate) VIIII, co(n)s(ul) II, proco(nsul). // A(nte) d(iem) X K(alendas) Dec(embres) / Marso et Faustino co(n)s(ulibus) (22 november 206) / ex gregale / C(aio) Iulio Gurati f(ilio) Domi/tiano Antioc(hia) ex Syr(ia) Coele / et Proculo f(ilio) eius / descriptum et recognitum ex tabula ae/rea qu(a)e fixa est Rom(a)e in muro pos(t) templum / diui Aug(usti) ad Mineruam. For Julian, AE, 1969/1970, 631 = 2000, 1503, Ma’ayan Barukh, cf.W. Eck, ‘Zur Neulesung der Iulian-Inschrift von Ma’ayan Barukh’, Chiron 30 (2000), 857–859: R[o]mani orbis liberat[o]/r[i], templorum / [re]stauratori, cur/[ia]rum et rei public/[ae] recreatori, bar/[ba]rorum extinctor[i] / d(omino) n(ostro) Iouliano / perpetuo Augusto / Alamannico maximo / Francico maximo / Sarmatico maximo, / [p]ontifici maximo, pa/tri patriae, Foenicum / genus, ob imperi[um] / [eius uota . . .].

- Christol 1997, op. cit. (n. 41), has chosen the Sasanids’ establishment as a turning point for his history of the 3rd century AD: 2nd part “La puissance de Rome à l’épreuve (226–249),” esp. 73–75 and 111 (notes); and Potter 1990, op. cit. (n. 40), “Appendix III: Alexander Severus and Ardashir,” 370–380, previously published in Mesopotamia 22 (1987), 147–157, with minor differences.

- See the convincing arguments about different documents by Xavier Dupuis, ‘L’empereur Numérien Germanicus maximus Gothicus maximus sur un milliaire du Sud tunisien’, Cahiers de Centre Gustave-Glotz 25 (2014), 263–279, within the acts of the colloquium of the French Society of Roman Epigraphy SFER [Paris 8 June 2013], about “Épigraphie et discours impérial: mettre en scène les mots pour le dire”): a milestone ( Jules Toutain, ‘Les nouveaux milliaires de la route de Capsa à Tacape découverts par M. le capitaine Donau’, MSAF 64 (1905), 153–230, no. 33; Pierre Salama, ‘Anomalies et aberrations rencontrées sur des inscriptions milliaires de la voie romaine Ammaedara-Capsa-Tacapes’, ZPE 149 (2004), 245–255, at 246–247 with Fig. 2 et 3 page 255) and Nemesianus, Cynegetics 63–71, for the main evidence about this peculiar commemoration of imperial victories.

- AE, 1975, 785d = AE, 1961, 26b, Yornus (Pontus et Bithynia): Impe[ratori Ca]es(ari) / Fl(auio) Val(erio) C[onst]antino / maximo uictor(i) / ac triumfator(i) / semper Aug(usto) / et Fl(auio) Cl(audio) Constantino / et Fl(auio) Iul(io) Constantio / et Fl(auio) Iul(io) Constantae (!) / [nobbb(ilissimis tribus) Caesss(aribus tribus)].

- About Constantine’s titulature, Stéphane Benoist, ‘La statio principis de l’empereur Constantin: figure augustéenne ou prince révolutionnaire?’, in Josep Villela Masana (ed), Constantinus. ¿El primer emperador cristiano? Religión y política en el siglo IV, Barcelona-Tarragona 20–24 de marzo de 2012 (Barcelone 2015), 325–336. For an inventory of the different cognomina deuictarum gentium, Benoist 2005, op. cit. (n. 8), 257–258.

- Cf. Stéphane Benoist, ‘Identité du prince et discours impérial: le cas de Julien’, Antiquité tardive 17 (2009) [2010], 109–117.

- Nov. Theod. 4, Feb. 25, 438: (. . .) ne libeat audacibus exercere litigia, ut liceat nostris militibus otiari, quos in extrema parte Romani saeculi sacramentorum legibus amandatos calumnia latentes inuenit? Quamobrem, Florenti parens karissime atque amantissime, inlustris et magnifica auctoritas tua, quae statuta maiestatis augustae cura peruigili et congruo semper fine conclusit, nunc etiam edictis propositis ad omnium notitiam faciat peruenire. “We must hope, that it will not please the audacious to employ litigation, and thus Our soldiers may be allowed to be at ease, although calumny finds them in obscurity in the farthest parts of the Roman Empire where they have been assigned by the regulations of their military oaths of service. Wherefore, O Florentius, dearest and most beloved Father, since Your Illustrious and Magnificent Authority always consummates the statutes of Our August Majesty with watchful care and with a suitable execution, you shall now also by posting edicts cause them to come to the knowledge of all.” (trans. Clyde Pharr, The Theodosian Code and Novels and the Sirmondian Constitutions [Princeton, 1952]). Cf. Fergus Millar, A Greek Roman Empire: Power and Belief under Theodosius II (408–450), Sather Classical Lectures 64, (Berkeley 2006), 75–76, about security and insecurity in a section dealing with “the Eastern Frontier: Sasanids and Saracens.”.

- The title Res Gestae was first conferred by Michael Rostovtzeff in his paper published in 1943: ‘Res Gestae Divi Saporis and Daru’, Berytus 8 (1943), 17–60. From Maricq’s edition to the monumental one by Philip Huyse who provided the last comprehensive edition of the text in the Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, after Richard Frye’s translation of the first part of the text in an appendix of his History of Ancient Iran: André Maricq, ‘Res Gestae Divi Saporis’, Syria 35 (1958), 295–360 = Classica et orientalia (Paris 1965), 37–101; Philip Huyse, Die dreisprachige Inschrift Šābuhrs I. an der Ka‘ba-I Zardušt (ŠKZ), Corpus Inscriptionum Iranicarum, III. Pahlavi Inscriptions, I. Royal Inscriptions (London 1999), and Richard N. Frye, The history of Ancient Iran (Munich 1983), “Appendix 4,” 371–372. About the interpretation of the text within the relations between Romans and Persians, from our “Roman evidence”—e.g. Dio to Ammianus Marcellinus, see above n. 24 the mention of the correspondence between Constance and Shapur II—, the accurate analysis by Erich Kettenhoffen, ‘Die Einforderung des Achämenidenerbes durch Ardašīr: Eine interpretatio romana’, Orientalia Lovaniensia Periodica 15 (1984), 177–190: Saphur I is by no means a “Cyrus redivivus!” For a complete overview of our evidence about the Romano-Parthian war: Id., Die römisch-persischen Kriege des 3. Jahrhunderts n. Chr. Nach der Inschrift Šāhpuhrs I an der Ka‘be-ye Zartošt (ŠKZ) (Wiesbaden 1982).

- Xavier Loriot and Philip Huyse, ‘Commentaire à deux voix de l’inscription dite Res Gestae Divi Saporis’, in Marie-Henriette Quet (ed.), La ‘crise’ de l’empire romain de Marc Aurèle à Constantin (Paris 2006), 307–344: Huyse, “Les provinces romaines dans la grande inscrip-tion trilingue de Šābuhr Ier sur la Ka‘ba-ye Zardošt,” 308–327; Loriot, “Les contingents de l’armée de Valérien,” 328–344.

- For example, Leo Truempelmann, ‘Sasanian Rock-Reliefs’, Mesopotamia 22 (1987), 337–340, who concluded his short paper by this final remark: “To sum up: The Sasanian reliefs within the enclosure-wall at Nagh-I Rustam were not to be seen by the public. They were not means of propaganda but were the grave-monuments of the respective kings and showed what the prominent achievement in the live of the king had been. It was for their soul and name-preservation that the reliefs had been made.” Contra Zeev Rubin, ‘The Roman Empire in the Res Gestae Divi Saporis. The Mediterranean World in Sāsānian Propaganda’, in Edouard Dąbrowa (ed.), Ancient Iran and the Mediterranean World. Proceedings of an international conference in honour of Professor Józef Wolski held at the Jagiellonian University, Cracow, in September 1996, (Cracow 1998), 177–185.

- The status of the Greek text of the trilingual inscription remains a real debate between specialists: for example, the Appendix of Zeev Rubin’s paper, ‘Res Gestae Divi Saporis: Greek and Middle Iranian in a Document of Sasanian, anti-Roman Propaganda’, in J.N. Adams, Mark Janse and Simon Swain (eds.), Bilinguism in Ancient Society. Language Contact and the Written Text (Oxford 2002), 267–297, “The Problem of the Genesis of the Greek Text,” 291–297 is a response to Huyse’s edition of the ŠKZ (1999, op. cit. n. 54), whose own 2006 paper (op. cit. n. 55) considers the use of three languages as a way to “univer-saliser les paroles du roi dans les langues vernaculaires de l’époque (at page 322).”

- I am very grateful to Mike Peachin and Olivier Hekster for improving my arguments and my English text, at various steps.

Chapter 4 (45-64) from Rome and the Worlds Beyond Its Frontiers, Edited by Daniëlle Slootjes and Michael Peachin (Brill, 11.17.2016), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.