It was considered a time of rebirth, in which the rulers considered the region to be of central importance.

By Dr. Joshua P. Nudell

Assistant Professor of History

Truman State University

Introduction

Ancient historians suggest that the world waited for Alexander’s death with bated breath and careful preparation, and that the news was met with a flurry of activity. In Europe Athens instigated the Lamian War, in Asia Minor Rhodes expelled its Macedonian garrison (Diod. 18.8.1), and in central Asia colonists settled by Alexander refused to stay in place (Diod. 18.7.1–5). InIonia, there was no revolt against Macedonian rule and, with the notable exception of refugee Samians returning to their island in the face of Athenian resistance, the Hellenistic period began with a conspicuous calm at the eye of the storm overtaking the eastern Mediterranean. That calm did not last, and Ionia was soon caught up in the conflicts and rivalries that defined the end of the fourth century.

Richard Billows has characterized this period in Ionia as a time of rebirth, in which the rulers considered the region to be of central importance and therefore planted the seeds of prosperity with favorable policies.1 As is typical of recent scholarship, Billows here challenged a tradition that treated the early Hellenistic period as a destructive time in Ionia. Mikhail Rostovtzeff, for instance, described the wars of this period as an unstoppable force that “stunted and then gradually atrophied” the economic capacity of the Greek poleis, and Michael Austin described the Diadochoi as pirates who used wars to gather money to pay soldiers and legitimize their rule as “spear-won territory” in emulation of Alexander.2 On one level it is hard to disagree with Billows: Hellenistic rulers offered tax exemptions, favorable statuses, and donations to gain influence with the Ionians that laid a solid foundation for renewed prosperity, while also allowing some of the tribute payments to stay in the community. Even the outlay of resources for urban walls proved invaluable during the Galatian wars of the 270s (I.Priene 17; I.Ery. 24). However, the dissolution of the Macedonian empire after Alexander’s death made for an unstable situation, and the same central geographic location that made the Ionians worth courting put them firmly in the middle of the early wars of the successors. This environment of competition allowed the Ionians to manipulate the imperial contenders, but in its own way this perpetuated the situation that the Ionians had been living under for two centuries. Only after the wars moved away from Ionia in the 290s did the Ionian renaissance begin in earnest.

Samians Restored

After the Athenian conquest of Samos in 365, refugees had scattered across the Mediterranean. Most found a new home nearby through the patronage of the Hecatomnid dynasts and existing networks of relationships, but a few found themselves as far away as Sicily.3 Some individuals may have received citizen-ship where they settled, but most would have lived as metics.4 Despite lacking a polis, the Samians appear to have maintained something of a coherent identity after their displacement, and even competed in and won events in Panhellenic festivals.5 This situation where the Samians preserved their identity and never gained full protections of citizenship elsewhere explains why when Alexander reversed his ruling on Athenian ownership of Samos in 324, the refugees began to flock to Anaia on the mainland across from the island.

Refugees began to return to Samos late in 324 or early 323, and an Athenian decree issued instructions for the strategos on the island to arrest those who made the crossing and send them to Athens as hostages.6 Despite the official ruling in their favor and support from foreign patrons, including two ships provided to them by Nausinicus of Sestus,7 the short voyage to Samos was a dangerous proposition. Athens enjoyed temporary naval supremacy in the Aegean at the outset of the Lamian War,8 but Samos was just one of its concerns, and the Samian position was enhanced when the Athenian fleet suffered defeats near Amorgus in 323/2, and then near Abydus (IG II2 398; II2 493) and off the Lichades islands in 322.9 When the war turned against the Athenians, they condemned the Samian hostages to death but relented after Antileon of Chalcis stepped in to pay their ransoms.

Antipater, the governor of Macedon, referred the issue of Samos to the kings Philip III Arrhidaeus and Alexander IV after the conclusion of the Lamian War, and the regent Perdiccas issued a decree on their behalf that confirmed Alexander’s decision to return the island to the Samians (Diod. 18.18.69). In return, the Samians established a new festival, the basilica, in honor of the kings, but official support did not return the island to them. The Samians still had to kill or physically expel the cleruchs, and the Athenians, impelled by the influx of displaced citizens, continued to regard the return as illegal. Several inscriptions may testify to additional Athenian attacks in the years after 321 (IG XII 6 51–52),10 but Samos never again fell to Athens.

However, physical security was just one of the difficulties facing the new community. A series of honorific decrees reveal the extent to which the new polis relied on foreign aid. In addition to the decree for Gorgos of Iasus, who financed the return of some Samians (RO 90B = SIG3 312), and Antileon of Chalcis, who paid the ransom for those captured by Athens (IG XII 6 1:42),11 there are inscriptions detailing honors for citizens of Ephesus, Erythrae, Magnesia, Priene, and Heraclea, as well as the tyrant of Syracuse and Gela.12 The Spartans reportedly underwent a one-day fast, with the savings going to Samos (Arist. Oec. 2.1347b 16–20), and Sosistratus of Miletus offered a three-talent loan to the new community (IG XII 37).13

The Samian need is easily explained. The refugees were long absent from their land, which was the primary source of wealth in ancient Greece, and what little they had in the way of liquid assets was probably needed to equip and pay soldiers to defend against Athenian attacks. Moreover, once returned to Samos, they faced agricultural start-up costs for tools and seed at the same time as needing to purchase grain to feed the community because it is unlikely that the departing Athenians left much behind. A widespread grain shortage around the Aegean in these years complicated matters further (RO 96 = SEG IX 2; Dem. 56),14 and Samian inscriptions reveal the lengths that the community went to encourage merchants to bring grain. One decree from c.322/1 (SEG I 361),15 for instance, records honors for Gyges of Torone for bringing three thousand medimnoi of grain to Samos and offers him citizenship, either in accordance with a law that honored grain traders or in a bid to persuade Gyges to sell them even larger quantities.

In contrast, the motivations for the honorands are less clear. They might have sympathized with the refugees, but neither spite for Athens nor human rights considerations explain the outpouring of support. Priene, Ephesus, and Miletus, despite disputes with Samos that spanned generations, also had regional connections through institutions like the Panionion and local trade that would have encouraged investment in the new community.16 Likewise, honors are not mutually exclusive from straightforward economic motivations. Men like Gyges and Sosistratus undoubtedly saw in Samos an investment opportunity, which would reap dividends through straightforward monetary repayment and through an outpouring of honors.17

The leaders of Samos in the years after the restoration were the wealthy citizens who led the exiles back to the island. Notable among these was the family of Duris of Samos. Pausanias describes a statue at Olympia dedicated to Caius, Duris’ father, for his victory during the period of exile (νικῆσαι Σκαῖον ἡνίκα ὁ Σαμίων δῆμος ἔφευγεν ἐκ τῆς νήσου, 6.13.5 = BNJ 76 T 4).18 The text continues, revealing that in due time Caius had something to do with the return of the Samians (τὸν δὲ καιρὸν [ . . . ] ἐπὶ τὰ οἰκεῖα τὸν δῆμον), but there is a critical lacuna that includes the verb of the clause. Modern scholars restore the text that he both led the exiles back and infer that he became a tyrant soon thereafter (BNJ 76 T 4).19 Graham Shipley has, however, called into question the source tradition about the early days of the new Samian state. He contends that Pausanias’ source for the importance of Caius in 322/1 is Duris himself, who had a reputation for exaggeration and a vested interested in burnishing his father’s reputation (BNJ 76 T 8 = Plut. Per. 28.1–3).20 The monument may record an authentic victory, but the inscription probably dates to after the restoration of Samos, which makes it impossible to know whether Caius represented himself as a member of a Samian community at Olympic games or, as I believe, this is an embellishment meant to show his dedication to his homeland.

The incipient state was heavily dependent on its wealthy citizens to function, for many of the same reasons that it was dependent on foreign aid. Robert Kebric argues that it was this dependence that led to a peaceful emergence of Caius’ tyranny out of what had been a de facto plutocracy.21 The question is what to make of this position called “tyranny.” If Duris is an unreliable narrator presenting an official account of this period, it is more difficult to reconstruct the political divisions on Samos. On the one hand, Caius and his sons undoubtedly held a dominant position in Samian politics. Duris’ name appears on Samian coins dating to c.310–300, which indicates that he held a monetary office during that period, and a brother Lysagoras introduced the honorific decree for Heraclea c.300.22 This confluence suggests that the family held a tight grip on the reins of power, but it is also possible that their position was not unlike that of Pericles in fifth-century Athens in that he was able to dominate the polis and be characterized as a tyrant without actually being one.23 This family’s prominence on Samos clearly existed under the leadership of their patriarch Caius, but its role in the restoration of Samos was expanded in memory through Duris’ writing and strategically erected monuments.

Samos and Diadochic Politics

The contested status of Samos made it particularly vulnerable to the political disputes of the early Hellenistic period. In 319 the new regent for Alexander IV and Philip III Arrhidaeus, Polyperchon, tried to win Athenian support for his war against Cassander by offering among other things to recognize Athenian ownership of the island in the name of the kings (Diod. 18.56.7). This scheme came to naught when Demetrius of Phalerum seized Athens with Cassander’s support in 317, but this did not mean that the Athenians abandoned their insular ambitions. In 313, the Athenian assembly voted to award honors to the satrap Asander in return for warships (IG II2 450, ll. 19–20). The purpose of the gifts to Athens is unknown, but Lara O’Sullivan argues that Asander provided the ships with the understanding that they would be used against Samos and connects this with two inscriptions from the island that record a siege (IG XII 6, ll. 51–52).24

These continuing threats against Samos had the effect of strengthening its relationship with Antigonus Monophthalmus. Despite Perdiccas’ support for the restoration of Samos, Antigonus was likely building his relationships there as early as 322/1. Certainly, after Triparadeisus, Antigonus’ sphere of influence as strategos of Asia was expanded to include Ionia, and his position as the protector of Samos was strengthened by Polyperchon’s support for the Athenian claim. Antigonus’ aid allowed the Samians to triumph against the attacks in 313, which cemented Samos within the Antigonid sphere of influence until 294.

The relationship between Samos and Antigonus is most clearly demonstrated in stone. Surviving inscriptions record numerous honors granted to members of Antigonus’ retinue, including a statue for Nicomedes of Cos.25 There is likewise evidence of Samian soldiers serving with Antigonus’ forces in various capacities. At the upper levels, Themison of Samos brought Antigonus forty ships at Tyre in 314 (Diod. 19.62.7) and served as a naval commander at the battle of Salamis in 306 (Diod. 20.50.4). But more indicative of this relationship than a single highly placed individual is that the Samians inscribed their thanks for Hipparchus of Cyrene for his support for Samos and, in particular, his treatment of Samian soldiers in Caria.26 On the island itself, there are the remains of towers on the western side that were probably constructed under the Antigonid aegis.27 These towers plausibly indicate the presence of a garrison, but the threat of force was probably not overtly coercive because the unique situation meant that the Samians also stood to gain time to restore their community.

The Wars of the Diadochoi and Ionia

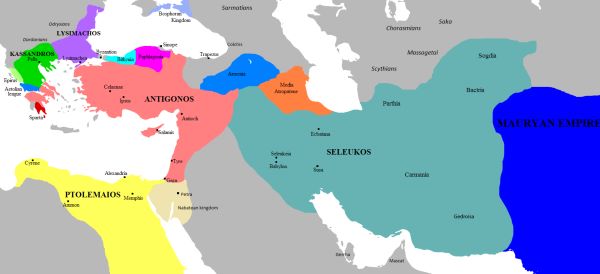

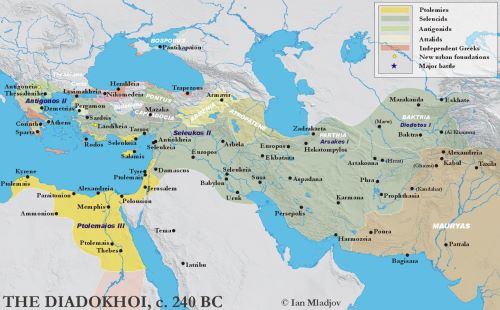

While the Samians were occupied with the restoration of their polis, the rest of Ionia was buffeted by the currents that swept across the Macedonian empire. The first Macedonian settlement, which took place at Babylon in the immediate aftermath of Alexander’s death in 323, confirmed the existing political structure of Asia Minor. Antigonus Monophthalmus received an expanded satrapy that included Pamphylia, Lycia, and Greater Phrygia, while Menander and Asander had their commands in Lydia and Caria confirmed (Diod. 18.3.1).28 The settlement at Babylon did not have a significant impact on Ionia at face value, but it laid the groundwork for a showdown between Antigonus and the regent Perdiccas, who was bringing him up on charges.

Antigonus fled from his province in 322, seeking protection from Antipater and Craterus in Macedon (Diod. 18.23.3–4). When Perdiccas left Anatolia to invade Egypt in 321, Antigonus crossed the Aegean again, this time with three thousand soldiers and ten Athenian ships. It was at this point that Ionia joined the story. According to Arrian in his fragmentary history of this period, Ephesus and the other Ionian poleis followed the lead of the Menander and Asander in throwing their support behind Antigonus (Succ. F 1.2). Antigonus’ rapid success leads Richard Billows to speculate that he had struck a deal with the two satraps in advance of crossing back to Asia.29 Irrespective of when Menander and Asander committed to war against Perdiccas, diplomatic communication between them and Antigonus is all but certain. The same cannot be said with confidence about the cities of Ionia. Antigonus had accepted the surrender of Priene on Alexander’s behalf in 331, but then the evidence for continuing communication disappears. Nevertheless, there is reason to suggest that Antigonus laid the diplomatic groundwork to quickly gain their support. It is certainly possible that Asander and Menander served as proxies for him in their respective spheres, but, more directly, Antigonus’ satrapal retinue included at least one Ionian, Aristodemus of Miletus, and the Macedonian Theotimides, whom the Samians awarded honors.30

Yet it is worth asking how the Ionians received these entreaties. Samos and Ephesus had known grounds for sympathy for Perdiccas because the regent had rendered judgments in their favor. For the Samians, he had confirmed Alexander’s ruling against Athens (Diod. 18.18.6–9). They had appropriately decreed honors for the kings in whose name he issued the ruling but were unlikely to be ignorant of who stood as their benefactor. The situation at Ephesus was more complicated. Under uncertain circumstances in the last years of Alexander’s reign Philoxenus had arrested the three sons of Echeanax and taken them to Sardis (Polyaneus 6.49). The brothers planned a daring jail-break, filing their chains and escaping over the walls dressed as slaves, but one, Diodorus, fell and was left behind, and so was sent to Alexander in Babylon for punishment. Perdiccas, however, returned Diodorus to Ephesus to stand trial, thereby demonstrating a deference to the local Ephesian institutions, particularly if, as I suggested in the last chapter, the root cause of this incident lay in local factionalism. This decision was just a small part of Perdiccas’ courtship of Ephesus, where his brother Alcetas, Cleitus the White, and another Ionian with ties to the Macedonian court, Hagnon of Teos, all received citizenship.31 Ephesian inscriptions in these years reflect a community in turmoil, and Andreas Walser describes the outpouring of honors as the result of fearful maneuvering,32 and with good reason. Polyaenus only provides the narrowest glimpse into domestic divisions in the city but concludes his anecdote by saying that Anaxagoras and Codrus returned to Ephesus to rescue their brother, almost certainly with the support of Antigonus.

The political map of the Macedonian world shifted again in 320 when Antipater, Antigonus, and the survivors of Perdiccas’ invasion of Egypt convened a meeting at Triparadeisus (Diod. 18.39.2–6).33 Asander was confirmed in his position as satrap of Caria, but Cleitus the White replaced Menander in Lydia (Diod. 18.39.6; Arr. Succ. F 1.41) and while Antipater formally became the new regent, Antigonus became strategos of Asia.34 The new arrangement lasted about year before Antipater died in 319, leaving the regency to Polyperchon (Diod. 18.48.4). The following year Cleitus prepared for war by installing garrisons in poleis in his territory, including at Ephesus, before crossing the Aegean to denounce Antigonus to Polyperchon. Antigo-nus promptly marched on and captured Ephesus with ease because a faction inside the walls opened the gates to his army (Diod. 18.52.7). Diodorus says that Antigonus seized six hundred talents of silver being carried from Cilicia to Macedon when the ship put into the harbor at Ephesus, thereby formally renouncing his allegiance to the kings. However, this episode is generally not considered for what it meant for Ephesus. Antigonus’ presumption marked a new phase in the unfolding Macedonian drama, but the appearance of rival factions who exploited that same drama for their own local ends remained business as usual in Ionia.

After Antigonus left Ephesus to chase Eumenes into the interior of Asia, there was a period of respite for Ionia until 315 when the Third Diadochic War returned the fighting to the eastern Aegean. This war set Antigonus and his son Demetrius Poliorcetes against Ptolemy in Egypt, Cassander in Macedonia, and Lysimachus in Thrace, and the fighting extended from the European side of the Aegean to Gaza and Babylon.35 Ionia was not a stronghold for any of the principal warlords, but nevertheless was exposed to attack by virtue of being in the middle of this wide-ranging war. One campaign in particular brought the war to the region. In the autumn of 315 Seleucus, having fled Babylon after arousing Antigonus’ ire earlier that year, led a Ptolemaic fleet to the Aegean and laid siege to Erythrae (Diod. 19.60.3–4).36 Antigonus responded by sending his nephew Polemaeus to the region to deter Ionian communities from capitulating, and Seleucus quickly abandoned the siege (Diod. 19.86.6).

Polemaeus’ campaign put additional pressure on Asander, the satrap of Caria, who concluded an alliance with Ptolemy in 314/3 and subsequently sailed to Athens seeking support from Cassander and Demetrius of Phalerum (IG II2 450). Both Ptolemy and Cassander offered him military assistance, but both expeditions suffered disastrous defeats (Diod. 19.68.2–7), and Asander agreed to surrender his armies to Antigonus (Diod. 19.75).37 When he reneged on this deal and called for support from the Ptolemaic fleet still under the command of Seleucus, Antigonus recalled his forces from their winter quarters, divided them into four columns, and conquered the region in a matter of weeks (Diod. 19.75).

The nature of the sources for the Third Diadochic War make it difficult to reconstruct its effects on Ionia. For instance, Diodorus records that Seleucus besieged Erythrae in 315, but offers scant detail about the polis other than that it held out against Ptolemy’s fleet. Diodorus also paints a simplistic picture of the situation at Erythrae where the resistance was more likely an Antigonid garrison than general opposition from the citizens. The exception to the general dearth of sources for Ionia during these years is at Miletus, which, although particular to the conditions there, also helps to shed light on the relationship between Ionia and the Macedonian warlords.

There is limited evidence for Miletus after 334, when Alexander captured it, but, at some point, the walls punctured by Alexander’s siege weapons were repaired and reinforced. Like the other Greek poleis in Asia Minor, Miletus slipped into limbo after Alexander’s death, but it remained deeply connected to Caria, which Asander received in the Macedonian settlements. In the wake of his agreement with Antigonus in 313, Asander installed a garrison in Miletus, allowing Antigonus’ forces to encourage the Milesians to assert their freedom (τούς τε πολίτας ἐκάλουν ἐπὶ τὴν ἐλευθερίαν, Diod. 18.75.4).

Yet there are signs that the Milesians were not passive victims of Hellenistic predation. Two years earlier, in 315, leading Milesians probably opened negotiations with Seleucus, then besieging Erythrae. The details of these negotiations are unknown, but in later years Seleucus would claim to have received a favorable oracle in the exchange. The problem, though, is that the oracle at Didyma had fallen silent when its hereditary priests were deported to central Asia a century and a half earlier. The Milesians had delivered alleged oracles to Alexander in Egypt in 331 as a veiled request for money (Strabo 17.43) and may have done so again with Seleucus.38 These negotiations therefore reveal a community trying to recover its lost prominence in this new world. The political and diplomatic activity was mirrored by a renewed spate of monumental construction that included the Delphinium and plans to restore the sanctuary of Apollo at Didyma. But there are signs of discontent and difficulty beneath the surface. One of the smaller pieces of monumental construction was the publication of inscriptions that record the list of aesymnetes (the eponymous officials). The second list begins after Antigonus’ capture of Miletus in 313/2 with the declaration that, in the term of Hippomachus, Antigonus restored autonomy and democracy to the polis (Ἱππόμαχος Θήρωνος, ἐπὶ τούτου ἡ πόλις | ἐλευθέρα καὶ αὐτόνομος ἐγένετο ὑπὸ | Ἀντιγόνου καὶ ἡ δημοκρατία ἀπεδόθη, Milet I.3, no. 123, ll. 2–4).39

The credulous reading of this inscription would accept that this was indeed how the Milesians thought of Antigonus, even though it invokes loaded terms such as “freedom” that became increasingly impotent missiles to be launched at opponents in the verbal wars of the Diadochoi. Further, the first entry to follow this declaration was Ἀπόλλων Διός, meaning that in the very next year the eponymous official was the god Apollo. Apollo appeared only twice on the list before this date, both in the tumult that followed Alexander’s conquest, but became a common occurrence in the early Hellenistic period, including four consecutive years in the 260s (Milet I.3, no. 123 ll. 53–56). The most common explanation for why the Milesians formally recorded Apollo as aesynmnetes is that these were years in which Miletus was in a state of financial emergency,40 but it is equally possible that it records a moment of social strife when the typical mechanisms for selecting the eponymous official broke down. In both scenarios, it holds that the reference to Antigonus was representative of the war-lord’s demands and not a celebration of liberty.

The inscription on the Milesian aesynmnetes list was a local manifestation of Antigonus’ imperial policy. In 314, Antigonus had made a proclamation at Tyre that all Greek poleis were to be free, autonomous, and ungarrisoned, which was followed in short order by a decree from Ptolemy to the same effect (Diod. 19.61.3–5).41 Richard Billows puts the proclamation in the context of Antigonus facing four hostile dynasts and thus argues that “the primary motive . . . was clearly to incite mainland Greeks to rebel against Kassandros [and] one may conclude that it was purely a politico-military maneuver, devoid of any broader policy or idealistic content.”42 Likewise, Sviatoslav Dmitriev sees the policy in light of Antigonus’ urgent need to “break down a military alliance that had been forged against him.”43 He further declares: “All these words and deeds had nothing to do with the actual status of individual cities.”44 The autonomy of the Greeks, including the Ionians, was a cornerstone of Antigonus’ policy between 315 and 301. What set him apart from his rivals with reference to Ionia was that he was in position to act upon his words.

Antigonus’ actions toward Ionia between 318 and 315 were opportunistic, driving Cleitus the White’s garrison from Ephesus (Diod. 18.52.5–8), but also supporting Cassander against Polyperchon, the latter of whom had promised the Greeks that he would remove Antipater’s garrisons installed after the Lamian War (Diod. 18.53.2–57.1; Plut. Phocion 31.1).45 In 318, Antigonus had a sphere of influence that was nominally limited to Anatolia, where he supported the Greeks against Cleitus. Since Polyperchon had already issued a declaration of freedom of the other Greek poleis, Antigonus gained little by following suit. This was also a period in which Antigonus had only minimal contact with Ionia since he was in the interior of Asia in pursuit of Eumenes until 316.46 Antigonus probably saw more value in independent allied cities than in expending his own forces to secure their allegiance. His forces therefore “liberated” the rest of Anatolia, and he ensured that a clause guaranteeing Greek autonomy appeared in the treaty of 311 (Diod. 20.19.3–4).47 These actions gave Antigonus a reputation for defending autonomy that Ionian poleis made reference to later in the third century when seeking royal benefactions,48 but he was also not opposed to creating garrisons when necessary (e.g., Diod. 20.111.3).49 Autonomy for Ionia served Antigonus’ purposes, but it was autonomy on his terms and always backed by the threat of force. The result was an upheaval in the human geography.

The wars of the Diadochoi between the Peace of 311 and the Ipsus campaign of 302/1 largely bypassed Ionia. Ptolemy sent a fleet to the southern coast of Caria, capturing Phaselis, Xanthus, Caunus, Myndus and Iasus, but Demetrius prevented the fall of Halicarnassus, so the campaign stalled before reaching Miletus (Diod. 20.27.1–2). Ptolemy spent the winter of 309/8 at Cos, where he proposed marriage to Alexander the Great’s sister Cleopatra, but after her murder he sailed on to Europe without attacking Ionia (Diod. 20.37).50 At the same time, Ionians participated in these wars on all sides. Much like the Samian soldiers discussed above and individual philoi, there is scattered evidence for Ionian mercenaries serving abroad, including a list of 150 mercenaries at Athens c.300 that records at least seven Ionians from five different poleis (IG II2, 1956).51 However, only in 302, when Lysimachus’ and Cassander’s general Prepelaus crossed the Hellespont as part of the final campaign against Antigonus, did war return to Ionia.

Prepelaus led his forces south through Aetolia to Ionia, where, according to Diodorus, his siege struck fear into the Ephesians and they surrendered without a fight (τὴν δ ̓ Ἔφεσον πολιορκήσας καὶ καταπληξάμενος τοὺς ἔνδον παρέλαβε τὴν πόλιν, 20.107.4). Prepelaus made a show of liberating Ephesus, confirming the tax exemption for the sanctuary of Artemis, freeing Rhodian hostages Demetrius had sent there, and declaring its freedom. At the same time, he burned warships in the harbor and, in a more galling move, installed his own garrison that either he or the garrison commander quartered in land belonging to the sanctuary of Artemis, from which they also requisitioned supplies (Diod. 20.107.4–5).52 Moreover, despite Diodorus’ mild language, Prepelaus enacted a domestic revolution within the ruling elite that rewarded the groups who opened the gates to him and toppled those that had been supported by Antigonus. When Demetrius recaptured Ephesus in 302, he replaced the garrison with one of his own and forced it back to its earlier condition (ἠνάγκασε τὴν πόλιν εἰς τὴν προϋπάρχουσαν ἀποκαταστῆναι, Diod. 20.111.3).53

There is a frustrating lack of information regarding what the Ionians thought about these shifting tides of war. Much as at the end of the fifth century, when Pausanias described the Ionians “painting both sides of the walls” (6.3.15), they seem to have fostered ties with both sides such that they were always victorious—or, at least, always in a position to minimize property damage.54 Certainly, the Hellenistic kings went to lengths to present their conquests as liberations, but their armies still needed to be fed, which placed strains on the Ionian economies.55 It is therefore not a surprise that the most common type of honorific decrees from early Hellenistic Ionia were those given to men who helped supply food, such as the Samian grant of citizenship for Gyges of Torone in 322/1 (SEG I 361)56 and the Ephesian decree for Archestratus of Macedonia in 302 (OGIS 9).57 Although the necessity of supplying grain to the Ionian poleis had governed the relationship with imperial powers in the past, the ubiquity of these honors reflects both the changing epigraphic habits in the early Hellenistic period and an evolution in how these negotiations took place. Where before Clazomenae might have received exemptions from regulation to ensure the grain supply, poleis now offered honors to individuals who might procure food for the community. Pausanias’ proverb about the Ionian flip-flopping represents a whitewashed memory of a divisive period in Ionian history when the contests over control of the region required poleis to court anyone able to help.

Prepelaus concluded his campaign in northern Ionia by accepting the surrender of Teos and Colophon but had to settle for raiding the territory of Clazomenae and Erythrae when they were reinforced by Antigonid soldiers. Such was the situation in Ionia in 301 when a coalition army under the command of Seleucus and Lysimachus defeated Antigonus and Demetrius at the battle of Ipsus.

After Ipsus

According to Plutarch, the victors of Ipsus carved up Antigonus’ kingdom as though it was a slaughtered animal (Demet. 30.1).58 Ionia nominally fell into the haunch claimed by Lysimachus north of the Taurus Mountains, but the situation on the ground was less certain. Immediately following the battle, Demetrius led nine thousand soldiers from the interior of Asia Minor to Ephesus (Plut. Demet. 30). He did not remain there long, but took steps to ensure its loyalty, including that he prohibited his soldiers from desecrating the sanctuary of Artemis. There is also evidence from Ephesus that Lysimachus encroached on Ionian territory, resulting in a low-intensity war after which the Ephesians gave citizenship to Thras[—] of Magnesia because he paid ransom for their captured citizens (I.Eph. 1450). (The final letters of his name are unfortunately lost.) Another inscription from after 299 records honors granted to Nicagoras of Rhodes, who relayed a joint declaration from Demetrius and Seleucus reaffirming their commitment to the freedom of the Greeks against Lysimachus—and gives Demetrius pride of place despite then being a political prisoner of Seleucus (OGIS 10).59

Concurrent with this apparently positive relationship between Demetrius and Ionia was the reality that the key to control of the region was Demetrius’ garrisons. According to Polyaenus, Lysimachus sought to claim Ephesus by bribing Diodorus the commander garrison in 301/0, but Demetrius ended this threat by luring him onto a boat in the harbor and killing him along with his supporters (4.7).60 Nor was Ephesus unique, and another decree granted honors to Archestratus, Demetrius’ strategos in Clazomenae, for protecting the ships carrying grain (OGIS 9).

Lysimachus was not the only king with ambitions toward Ionia. Ptolemy’s forces captured Miletus in c.299/8, though Demetrius appeared on the aesymnetes list for 295/4, indicating that he continued to wield influence there (Milet I.3, no. 123 l. 22).61 It was in this same period that Seleucus’ relationship with Miletus flourished. Seleucid propaganda promoted the story that the oracle at Didyma had foretold his rise and backed up this claim with a set of massive offerings to adorn the new temple (I.Didyma 479), as well as with dedications from his son Antiochus and wife Apame that defrayed the construction costs (SEG 4 470 and SEG 34 1075).62 The Milesians duly offered honors for the royal family, but these benefactions did not prevent the reappearance of Apollo on the aesymnetes list for 299/8 (Milet I.3, no. 123, l. 18).

Demetrius sailed to Athens in 296/5, and Lysimachus took the opportunity to seize Ionia. Although Demetrius temporarily regained control of the region in 286/5, Lysimachus’ campaign in 294 was the denouement of the war in Ionia that reached its bloody climax at Ipsus.

Ionia and the Kings: Euergetism and Human Geography

The early Hellenistic period in Ionia was defined by its relationship with the kings, both for good and for ill. On one side of the ledger, Richard Billows has argued that royal favor in the form of tax exemptions and donations laid the foundation for a renaissance in Ionia.63 On the other side, though, the wars of the successors imposed economic costs that stunted growth. Apollo appears with increasing regularity on the Milesian aesymnetes list in this period, for instance, and there is an Ephesian debt law of c.297 that was likely directed at ameliorating the consequences of property destruction. Nor were taxes the only financial demand made on Ionia. Poleis were expected to contribute to the upkeep of the garrisons, and while they benefited from royal building programs, they were also frequently expected to both leave alone sacred funds and pick up the tab for civic projects.

The toll war took on Ionia is taken as a truism in scholarship, with the question then being which of the kings is to blame for impoverishing the region, because that might give some indication of political sympathies. Lysimachus is the traditional villain because he demanded new taxes after he captured Ionia in 294. Moreover, Lysimachus was uncommonly honest about his taxation, leading to the assumption of his miserliness that exposed him to denunciations from the other kings about how he deprived the Greeks of their freedom. Helen Lund has persuasively argued that Lysimachus’ impositions were neither novel nor excessively harsh and therefore blames Antigonus and Demetrius instead.64 Stanley Burstein likewise relieves Lysimachus of sole blame but more plausibly accuses all the Diadochoi of extorting the Ionians.65 There are also examples of euergetism from kings courting Ionian poleis while they were subject to a rival. These donations were symbols that marked out an ideological claim to space, while simultaneously performing elaborate courtship rituals that paid homage to the fiction of the autonomous polis.66

The reciprocal relationship of taxation and benefaction only tells one part of the story. Ionian poleis offered the kings a variety of honors, including festivals and grants of ateleia (tax exemption). These awards went out to a king for his euergetism on behalf of the community. Samos founded a religious festival for Antigonus and Demetrius after 306 and renamed one of its existing tribes Demetrieis to proclaim its allegiance to Antigonus and his son. Similarly, the Samians voted honors for an associate of Demeterius’ wife Phila, whom they petitioned about an unknown issue in 306 (SIG3 333, ll. 8–9).67 On the mainland, Ephesus awarded the traditional founder cult honors to Lysimachus when he moved its location in c.294 and by 289/8, Seleucus asked for libations from the temple of Apollo at Didyma for his continued good health (OGIS 214, ll. 11–12).

The politics of reciprocity demanded that the kings exchange something in return even if the privileges were frequently more symbolic than practical. In rare instances the benefits included tax exemptions such as Antigonus granted to Erythrae (I.Ery. 31 and 32) and Ephesus,68 but these were the exception. In other cases, the kings prescribed new civic building projects, such as walls at Colophon, Erythrae, and Ephesus, but left a significant portion of the expenses to the citizens.69 There was a proliferation of increasingly expensive defensive fortifications, including circuit walls, forts, and watchtowers, built in nearly every Ionian polis, which marked a departure from the fifth and early fourth centuries, when Ionia was famously unwalled. The impressive circuit walls of Ephesus and Colophon dated to the early Hellenistic period, and Anthony McNicoll characterizes the technical details as a response to the increasing sophistication of Macedonian siege warfare, but these structures were part of a longer continuum of Ionian history. At Priene, for instance, the fortifications that Rostovtzeff characterized as “unsurpassed in technical efficiency and sober beauty” show clear parallels with contemporary Carian examples, suggesting that they were established earlier in the century.70 Inscriptions also record the appointment of civic officials to oversee maintenance on the walls (e.g., I.Ery. 23).71 More importantly, though, are inscriptions recording private donations for wall construction, with fragments from Erythrae revealing contributions of more than sixteen thousand drachmae for one part of the construction (two and half talents; I.Ery. 22A and B) and an inscription at Colophon recording contributions of more than two hundred thousand drachmae (thirty-five talents).72

The human geography of Ionia also changed in the early Hellenistic period. Either Antigonus or Lysimachus refounded Smyrna by combining four small towns, though tradition gave credit to Alexander (Pausanias 7.5.1–3; Aelius Aristides 10.7, 20.20), and it was likely at this time that it received admission to the Panionion.73 Although local identities proved an intractable problem in some of these synoikisms, the reshuffling made sense for the kings. The patch-work of small towns made each community vulnerable, while consolidation made control over the region easier.74 The nucleated settlement at Colophon moved between 315 and 306, which is attested by a new set of walls built by Antigonus that enclosed both the new and old settlements.75 What makes this civic project notable beyond that the community soon relocated is a partial list of donors who contributed funds for construction. In addition to many citizens, the list includes four men identified as Macedonians. One Stephanus offered one of the largest single donations: three hundred gold staters.76 Although there is no information about these people outside this list, other Ionian poleis offered the Macedonians citizenship,77 so the listed individuals likely had close connections to the community, perhaps even living there. In c.303, there was also a proposed synoikism of Teos and Lebedus that, if it was not the brainchild of Antigonus, was pursued under his direction (Ager 13, ll. 5–15).78 An earthquake in 304/3 had caused considerable damage in Ionia, so Billows posits that both poleis suffered damage and sought Antigonus’ help, perhaps unaware that the king would instruct them to merge and to send joint representatives to the Panionion.79 In contrast, the citizens of Myus voluntarily relocated to Miletus because the gnats in the surrounding marshes became unbearable (Pausanias 7.2.11; Strabo 14.1.10).80 The story that insects defeated the polis is probably hyperbolic, but the silting up of the Gulf of Latmus likely caused the farmland at Myus to turn to marsh and provides a salient reminder that the Ionian communities faced natural as well as human challenges in the early Hellenistic period.81

The largest Ionian polis to undergo a transformation was Ephesus, which moved to a new site shortly before 294 because the original location ceased to have access to the sea due to the silting of the Cayster River (Paus. 1.9.7).82 According to Strabo, the Ephesians found the idea of moving distasteful, but Lysimachus literally flushed them from their homes by blocking the sewers in advance of a torrential downpour, thereby flooding the original settlement (Strabo 14.1.21). Strabo’s story is far-fetched, but the flooding was most likely real. The contemporary poet Duris of Elaia composed an epigram about a deluge sweeping all into the sea (Stephanus, Greek Anthology 9.424) and Ephesus had long been combating the rivers, including a project to dam the Silenous in order to prevent it from flooding the sanctuary.83 Guy Rogers therefore convincingly argues that Ephesus moved location before Lysimachus captured the region and that blaming him for the deluge was a story started by Demetrius’ allies in the polis.84

In addition to renaming Ephesus “Arsinoeia” after his third wife, Lysimachus added to it the populations of Colophon, Lebedus, and probably Pygela (Paus. 1.9.7, 7.3.4–6).85 The capture of Colophon prompted the iambic poet Phoenix to compose a lament (Paus. 1.9.7), and Pausanias cryptically adds that the Colophonians were the only people to fight against the new foundation of Arsinoeia (7.3.4). How the evidence for the sack of Colophon and temporary relocation of the citizens to Ephesus correlates with the earlier synoikism of the old and new settlements in the reign of Antigonus is unknown.86 The Lebedians maintained a coherent identity at Ephesus, though, and refounded their polis in c.266 with the blessing of Ptolemy II Philadelphus in exchange for naming it “Ptolemais,” once again using imperial politics for local ends.87 Arsinoeia (Ephesus) flourished at the new location even though some of its new populations left after Lysimachus’ death, but it reverted to its traditional name and continued to struggle with the silting of the Cayster River (Strabo 14.1.21, 25).88

Although the traditions surrounding Lysimachus’ refoundation of Ephesus are suspect, he did have a lasting impact on Ephesus by neutering the power of the Artemisium, perhaps because it was closely associated with Demetrius. The sanctuary itself was untouchable, so Lysimachus instead underwrote the costs of a new temple complex at Ortygia for Artemis Soter. The cult was multidimensional. Ortygia, near the boundary between Ephesus and Pygela, was one of the traditional birthplaces for Artemis, and this martial avatar commemorated Lysimachus’ victory and alluded to his protection of Ephesus, while calling to mind the Ephesian claim to Pygela even if the community was in the process of being incorporated into Arsinoeia. But the most important feature of the cult was that Lysimachus took for himself some of the religious authority and delegated to the Arsinoeian Gerousia the right to oversee the festivals and mediate between the two sanctuaries of Artemis, which gave Ephesus unprecedented control over its sanctuary.89

The kings also intervened in the Ionian poleis through arbitrations.90 When Antigonus presided over the proposed synoikism between Teos and Lebedos, he appointed Mytilene as an arbitrator in cases that dealt with the special agreement he instructed the two states to develop, but both the new laws and unforeseen disputes were to be referred to Antigonus himself, following the model established by Alexander, which in turn, followed the example of the Persian satraps.91 The king framed his decision in the language of a neutral arbitrator, but royal suggestions carried the force of commands. Antigonus also likely established regulations for the arbitration of a border dispute between Clazomenae and Teos c.302 (SEG XXVIII 697). Though the inscription is heavily reconstructed and both the name Antigonus and the regulations open to debate, Clazomenae and Teos shared a small peninsula, and Sheila Ager reasonably argues that population growth from the result of the inchoate synoikism between Teos and Lebedos prompted the Teians to expand their territory and thus ran into conflict with the Clazomenaeans.92

Finally, the kings supported the Ionian League, which took on a new political importance. The league served the kings by providing a system of organization. When Lysimachus conquered Ionia he appointed strategoi to oversee the league, perhaps in parallel to Philoxenus during the reign of Alexander, but there is no evidence for a comparable appointee under Antigonus.93 The relationship between strategos and league is largely unattested; Helen Lund speculates that he had the authority to intervene in the judicial and financial affairs, but she also posits that the absence of evidence for strat-egoi later in Lysimachus’ reign indicates that the position was an extra security measure for an important region that was neither routine nor entirely unique.94

The question remains what can be said about the state of the Ionian poleis between 323 and 294. They were clearly subordinate to and, in many respects, at the mercy of the Diadochoi, even while they maintained some level of autonomy. In other words, whereas the early Hellenistic period saw a radical reorientation on the imperial playing field, there was a great deal of continuity in Ionia. The replacement of satraps and imperial poleis with kings increased the asymmetrical power relationships, but it did not stop the Ionian poleis from nego-tiating their existence within this sphere. Characterizing the Ionian poleis as simply subordinate to the Diadochoi also obscures the local and regional political activity taking place, as Jeremy LaBuff has recently shown for Hellenistic Caria.95 Likewise, in addition to circuit walls around the nucleated settlements, the chorae of Hellenistic Ionia contained forts garrisoned by citizen-soldiers, which John Ma has demonstrated indicates an ongoing militarism.96 In Ionia, Miletus and Teos were two of the earliest poleis outside Athens to institute formal ephebeia, and an inscription found at Smyrna records regulations and pay for the Teian garrison in the citadel of Cyrbissus, a nearby town whose inhabitants gained citizenship at Teos in the third century (SEG XXVI 1306).97 Likewise, a late fourth-century inscription records a treaty of isopolity between Pygela and Miletus (Milet I.3, no. 142), giving Pygelans rights in Miletus, but equally important, offering protection against the ongoing encroachment of Ephesus that culminated in Pygela being absorbed by Arsinoeia. Even as the Ionians were subject to the demands of the Hellenistic kings, they continued to play out regional competitions that had existed for as long as their cities had.

Endnotes

- Richard A. Billows, “Rebirth of a Region: Ionia in the Early Hellenistic Period,” in Regionalism in Hellenistic and Roman Asia Minor, ed. Hugh Elton and Gary Reger (Pessac: Ausonius, 2007), 33–44.

- Mikhail Rostovtzeff, Social and Economic History of the Hellenistic World, vol. 1 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1941), 4; M. M. Austin, “Hellenistic Kings, War, and the Economy,” CQ 236, no. 2 (1986): 464–65.

- Christian Habicht, “Samische Volksbeschlüsse der hellenistischen Zeit,” MDAI(A) 72 (1957): nos. 25 and 30 dated to 306/5, probably recording honors for Syracusans. Another inscription (no. 23) records honors for a man from Heraclea, but it is unknown whether this was the polis of that name in Sicily or Heraclea under Latmus; see Graham Shipley, A History of Samos, 800–188 BC (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987), 164 n. 52, who prefers the latter identification.

- On the consequences, see Shipley, Samos, 165–66.

- BNJ 76 T 4; Robert B. Kebric, In the Shadow of Macedon, Duris of Samos (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner, 1977), 7. There are complications in this evidence for a coherent polis-in-exile

- Habicht, “Samische Volksbeschlüsse,” no. 1.

- Habicht, “Samische Volksbeschlüsse,” no. 2.

- The Athenians had access to around 410 ships in the 320s, IG II2 1631, ll. 167–74. See N. G. Ashton, “The Naumachia near Amorgos in 322 B.C.,” ABSA 72 (1977): 1–11; A. B. Bosworth, “Why Did Athens Lose the Lamian War?,” in The Macedonians in Athens, 322–229 B.C., ed. Olga Palagia and Stephen V. Tracy (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 14–15.

- Ashton, “Naumachia Near Amorgos,” 1–11; Waldemar Heckel, Who’s Who in the Age of Alexander the Great (New York: Routledge, 2005), 87–88. Bosworth, “Why Did Athens Lose?,” 19–22 argues that there were additional, unrecorded naval battles in 323/2. The arrival of Cleitus the White’s massive fleet in 322 drove the Athenians from the eastern Aegean.

- Lara O’Sullivan, The Regime of Demetrius of Phalerum in Athens, 317–307 BCE (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 261–63; Lara O’Sullivan, “Asander, Athens, and ‘IG’ II2 450: A New Interpretation,” ZPE 119 (1997): 107–8.

- Habicht, “Samische Volksbeschlüsse,” 156–64, no. 1.

- Christian Habicht, “Hellenistische Inscriften aus dem Heraion von Samos,” MDAI(A) 87 (1972): nos. 2, 4; Habicht, “Samische Volksbeschlüsse,” nos. 2, 18, 23, 30; Shipley, Samos, 161–63. On the honorific inscriptions cf. below, “Samos and Diadochic Politics.”

- On long-term loans for the Samian state, see Habicht, “Hellenistische Inscriften,” 201–2. Christian Habicht, “Der Beitrag zur Restitution von Samos während des lamischen Krieges (Ps. Aristoteles, Ökonomik II, 2.9),” Chiron 5 (1975): 45–50, connects the Spartan fast to their refusal to assist Athens in the Lamian War, but Shipley, Samos, 168, also points out that Samos and Sparta had a history of close relationships dating back to the Archaic period; cf. L. H. Jeffrey and Paul Cartledge, “Sparta and Samos: A Special Relationship?,” CQ2 32, no. 2 (1982): 243–65.

- The inscription records the purchase of grain from Cyrene for many communities in the Aegean and for Olympia and Cleopatra. Rhodes and Osborne also provide a map showing sale distribution, but Ionia is conspicuously absent from the list. This fact could be interpreted to mean that Ionia was self-sufficient in grain, but it is more likely that Ionian imports came from the north. Dominic Rathbone, “The Grain Trade and Grain Shortages in the Hellenistic East,” in Trade and Famine in Classical Antiquity, ed. P. D. A. Garnsey and C. R. Whittaker (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1983), 45–55, posits that though war could have disrupted the flow of grain, many of the crises were the result of price gouging rather than limited supply. By the end of the third century there were regular grain distributions at the temple of Hera; see Habicht, “Samische Volks-beschlüsse,” no. 63, with the dating. Daniel J. Gargola, “Grain Distributions and the Revenue of the Temple of Hera on Samos,” Phoenix 46, no. 1 (1992): 12–28, points out that the law was a form of social control rather than a humanitarian venture. See Errietta M. A. Bissa, Governmental Intervention in Foreign Trade in Archaic and Classical Greece (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 169–203, on Ionian grain imports, which were a regular part of Greek legislation; cf. Wim Broekaert and Arjan Zuiderhoek, “Food and Politics in Classical Antiquity,” in A Cultural History of Food in Antiquity, ed. Paul Erdkamp (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), 75–94.

- Habicht, “Samische Volksbeschlüsse,” no. 6. One medimnos in the Attic measurement system was 51.84 liters.

- An Athenian inscription from 387/6 regulating trade at Clazomenae lists poleis that Clazomenaeans purchased grain from, including Phocaea, Chios, and Smyrna, demonstrating the robust regional trade in Ionia (RO 18 = IG II2 28, ll. 17–18).

- For honors being a regular aim of commerce, see Darel Tai Engen, Honor and Profit: Athenian Trade Policy and the Economy and Society of Greece, 415–307 BCE (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010), 8–12.

- The name Caius is remarkable for its parallel to the Latin praenomen, which is taken to buttress the case that his family spent the period of their exile in Sicily; see Kebric, In the Shadow of Macedon, 4; Frances Pownall, “Duris of Samos (76),” BNJ T 4, commentary, but this is a particularly tenuous connection so long before the First Punic War that established Roman control of the island.

- Pownall, “Duris of Samos (76),” T 4 commentary; J. P. Barron, “The Tyranny of Duris at Samos,” CR 12, no. 3 (1962): 191; Helen S. Lund, Lysimachus: A Study in Early Hellenistic Kingship (New York: Routledge, 1992), 124; Kebric, In the Shadow of Macedon, 7–8.

- Shipley, Samos, 178. On Duris, see Pownall, “Duris of Samos (76),” T 8, commentary, following W. E. Sweet, “Sources of Plutarch’s Demetrius,” Classical Weekly 44 (1951): 177–81.

- Kebric, In the Shadow of Macedon, 8. See Pownall, “Duris of Samos (76),” T 4 commentary and biographical commentary, for arguments on the dates of Caius’ tyranny and the proposal that Duris’ reign should not be tied to the hegemony of a single Hellenistic king.

- Habicht, “Samische Volksbeschlüsse,” no. 23; Stephen V. Tracy, “Hands in Samian Inscriptions of the Hellenistic Period,” Chiron 20 (1990): 62; Shipley, Samos, 178; J. P. Barron, The Silver Coins of Samos (London: Athlone, 1966), 124–40.

- Cf. Thuc. 2.65 for Pericles’ power over Athens.

- O’Sullivan, Regime of Demetrius, 261–63. Edward M. Anson, “The Chronology of the Third Diadoch War,” Phoenix 60, nos. 3–4 (2006): 230–31, finds O’Sullivan’s chronology problematic and concludes that while her reconstruction is the most attractive thus far, the purpose can only be guessed. Cf. Richard A. Billows, Antigonus the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 116–17 n. 43. Shipley, Samos, 172, connects the attack to the campaign waged by Myrmidon of Athens, a mercenary who commanded Cassander’s Carian campaign. Most likely, Cassander and Demetrius coordinated their attacks.

- Habicht, “Samische Volksbeschlüsse,” no. 3. Shipley, Samos, 171, modifies Habicht’s dating of the inscription from 320 to 319 in responses to Polycheron’s edict granting Samos to Athens, but Billows, Antigonus, 411–12, Appendix 3 no. 82 dates the inscription to 312–310.

- Habicht, “Samische Volksbeschlüsse,” no. 22.

- Shipley, Samos, 246–47.

- On the power struggle among the Macedonian ruling class, see Edward M. Anson, Alexander’s Heirs: The Age of the Successors (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2014), 47–49; Richard A. Billows, Kings and Colonists: Aspects of Macedonian Imperialism (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 90–92; Billows, Antigonus, 402–3; R. Malcolm Errington, “From Babylon to Triparadeisos: 323–320 B.C.,” JHS 90 (1970): 49–59; Alexander Meeus, “The Power Struggle of the Diadochoi in Babylon, 323 BC,” Anc. Soc. 38 (2008): 39–83; Robin Waterfield, Dividing the Spoils: The War for Alexander the Great’s Empire (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 16–29. Menander had been satrap of Lydia since 331; see Heckel, Who’s Who, 163. The decision at Babylon with the greatest significance for Ionia was Lysimachus receiving Thrace, but the consequences of that appointments would not be seen for nearly two decades.29. The chronology for the first Diadoch War is contested. Pierre Briant, Antigone le Borgne: Les débuts de sa carrière et les problèmes de l’Assemblée macédonienne (Paris: Les Belles Lettres, 1973), 208, suggests that Asander and Menander only joined with Antigonus after Craterus and Antipater declared war. On the issues of chronology, cf. Anson, Alexander’s Heirs, 57–58; Hans Hauben, “The First War of the Successors (321 B.C.): Chronological and Historical Problems,” Anc. Soc. 8 (1977): 85–119; Waterfield, Dividing the Spoils, 57–60. Supposedly it was news of Perdiccas’ courtship of Alexander’s sister Cleopatra, which Antigonus learned after he crossed into Asia, that swayed the other two Macedonians (Diod. 18.25.3). Anson, Alexander’s Heirs, 56; James Romm, Ghost on the Throne: The Death of Alexander the Great and the Bloody Fight for His Empire (New York: Vintage Books, 2011), 147–48; Waterfield, Dividing the Spoils, 57–60. Asander and Antigonus may have been kinsmen; see Heckel, Who’s Who, 57. Menander supposedly resented Perdiccas because the regent had made Cleopatra his superior at Sardis: Arr. Succ. 1.2.6; Waldemar Heckel, Marshals of Alexander’s Empire (New York: Routledge, 1992), 54; Heckel, Who’s Who, 57, 163.

- Antigonus dispatched Aristodemus to the Peloponnese to recruit mercenaries. Diodorus (19.57.4–5) refers to him as strategos; Plutarch Demet. (17.2), calls him “first in flattery” (πρωτεύοντα κολακείᾳ); Billows, Antigonus, for Aristodemos: 372, for Theotimides: 437–38; Jeff Champion, Antigonus the One-Eyed: Greatest of the Successors (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2014), 23; Shipley, Samos, 166.

- I.Eph. 1435, 1438, 1437; Andrew J. Bayliss, “Antigonos the One-Eyed’s Return to Asia in 322,” ZPE 155 (2006): 108–26; Attilio Mastrocinque, La Caria e la Ionia méridionale in epoca ellenistica (Rome: L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1979), 17.

- Andreas Victor Walser, Bauern und Zinsnehmer: Politik, Recht und Wirthschaft im frühhel-lenistischen Ephesos (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2008), 49–55.

- The chronology of this period is disputed between the so-called high chronology and the low, which holds that events took place one year later; I follow the low chronology. For the low, see Errington, “From Babylon to Triparadeisos,” 75–77; R. Malcolm Errington, “Diodorus Siculus and the Chronology of the Early Diadochoi, 320–311 B.C.,” Hermes 105, no. 4 (1977): 478–504; Edward M. Anson, “Diodorus and the Date of Triparadeisus,” AJPh 107, no. 2 (1986): 208–17; Edward M. Anson, “The Dating of Perdiccas’ Death and the Assembly at Triparadeisus,” GRBS 43, no. 4 (2003): 373–90; Anson, Alexander’s Heirs, 58–59; Billows, Antigonus, 64–80; Joseph Roisman, Alexander’s Veterans and the Early Wars of the Successors (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012), 136–44; high: A. B. Bosworth, “Philip III Arrhidaeus and the Chronology of the Successors,” Chiron 22 (1992): 55–81; A. B. Bosworth, “Perdiccas and the Kings,” CQ2 43, no. 2 (1993): 420–27. Tom Boiy, Between High and Low: A Chronology of the Early Hellenistic Period (Mainz: Verlag Antike, 2007) offers a compromise between the two.

- Anson, Alexander’s Heirs, 70–74; Errington, “From Babylon to Triparadeisos,” 67–71; Heckel, Who’s Who, for Asander 57, for Menander 163, for Cleitus, 87–88; Heckel, Marshals, 58–64; Waterfield, Dividing the Spoils, 66–68. The two other appointments at Triparadeisus with ramifications for Ionia later in the Hellenistic period were Ptolemy in Egypt and Seleucus in Babylon.

- For studies of the Third Diadochic War, see particularly Anson, “Chronology,” 226–35; Alexander Meeus, “Diodorus and the Chronology of the Third Diadoch War,” Phoenix 66, nos. 1–2 (2012): 74–96; Roisman, Alexander’s Veterans, 130–44; Pat Wheatley, “The Chronology of the Third Diadoch War, 315–311 B.C.,” Phoenix 52, nos. 3–4 (1998): 257–81.

- Billows, Antigonus, 113; Champion, Antigonus, 80. John D. Grainger, Seleukos Nikator: Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom (New York: Routledge, 1990), 58–59, speculates that Seleucus’ siege of Erythrae was a distraction to give his troops something to do while he negotiated with Asander.

- For analyses of the relationship between Asander and Antigonus at this juncture, see Richard A. Billows, “Anatolian Dynasts: The Case of the Macedonian Eupolemos in Karia,” CA 8, no. 2 (1989): 173–206; Billows, Antigonus, 120; Waterfield, Dividing the Spoils, 116–17.

- See Joshua P. Nudell, “Oracular Politics: Propaganda and Myth in the Restoration of Didyma,” AHB 32 (2018): 49–53, on the nature and date of this interaction.

- Anson, “Chronology,” 230; Lund, Lysimachus, 115; R. H. Simpson, “Antigonus the One-Eyed and the Greeks,” Historia 8, no.4 (1959): 392. Robin Seager, “The Freedom of the Greeks of Asia: From Alexander to Antiochus,” CQ2 31, no. 1 (1981): 107, notes that Diodorus says this campaign is how the Greeks became subject to Antigonus.

- Stanley M. Burstein, The Hellenistic Age from the Battle of Ipsos to the Death of Kleopatra VII (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 33 n. 3; Robert K. Sherk, “The Eponymous Officials of Greek Cities IV: The Register: Part III: Thrace, Black Sea Area, Asia Minor (Continued),” ZPE 93 (1992): 229–32.

- On these proclamations, see Claude Wehrli, Antigone et Démétrios (Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1968), 110–11; Billows, Antigonus, 116, 199–200; Sviatoslav Dmitriev, The Greek Slogan of Freedom and Early Roman Politics in Greece (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 117–19; Simpson, “Antigonus the One-Eyed,” 390; Ian Worthington, Ptolemy I: King and Pharaoh of Egypt (Oxford: Oxford University Press 2016), 118–19.

- Billows, Antigonus, 199.

- Dmitriev, Greek Slogan of Freedom, 118.

- Dmitriev, Greek Slogan of Freedom, 119.

- Billows, Antigonus, 199; Heckel, Who’s Who, 227. Cornelius Nepos, Phocion, 3, says that Cassander had supporters in Athens, but that the popular party in Athens had the support of Polyperchon.

- Billows, Antigonus, 198.

- Billows, Antigonus, 200 n. 29; Mastrocinque, La Caria, 26, describes the Peace of 311 as a temporary truce along the lines of the status quo, while R. H. Simpson, “The Historical Circumstances of the Peace of 311,” JHS 74 (1954): 25–31, posits strategic gain for Antigonus through diplomacy in that he conducted negotiations with Lysimachus and Cassander that forced Ptolemy to exclude Seleucus from of the settlement. Cf. Simpson, “Antigonus the One-Eyed,” 393–94.

- E.g., C. Bradford Welles, Royal Correspondence in the Hellenistic Period (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1934), no. 15.

- Seager, “Freedom of the Greeks,” 107; Lund, Lysimachus, 116–17. Lund’s list of garrisons is exaggerated, and includes one dated after Antigonus’ death and those in Cilicia.

- On the marriage proposal, see recently Worthington, Ptolemy, 152–54, with bibliography.

- There were one each from Ephesus and Priene, two from Colophon, three from Miletus, and an indeterminate number of Erythraeans. This is a small, but not insignificant, percentage of the total.

- On the capture of Ephesus, see Billows, Antigonus, 176; Lund, Lysimachus, 72, 118; Guy Maclean Rogers, The Mysteries of Artemis of Ephesos: Cult, Polis, and Change in the Graeco-Roman World (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2012), 44–46; Walser, Bauern und Zinsnehmer, 67.

- Lund, Lysimachus, 125–26.

- J. K. Davies, “The Well-Balanced Polis: Ephesos,” in The Economies of Hellenistic Societies, Third to First Centuries BC, ed. Vincent Gabrielsen, J. K. Davies, and Zosia Archibald (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 193–94, suggests that Ephesus was particularly adept at this practice.

- Angelos Chaniotis, “The Impact of War on the Economy of Hellenistic Poleis: Demand Creation, Short-Term Influence, Long-Term Impacts,” in The Economies of Hellenistic Societies, Third to First Centuries BC, ed. Vincent Gabrielsen, J. K. Davies, and Zosia Archibald (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011), 126–27; A. Chaniotis, War in the Hellenistic World (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005), 122–28. Gary Reger, “The Economy,” in Companion to the Hellenistic World, ed. Andrew Erskine (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003), 337–38, also notes that expanding populations challenged the food supply of Hellenistic poleis.

- Habicht, “Samische Volksbeschlüsse,” no. 6.

- On the grain supply to Ionian poleis, see Richard A. Billows, “Cities,” in Companion to the Hellenistic World, ed. Andrew Erskine (Malden, MA: Blackwell: 2003), 212; Chaniotis, War in the Hellenistic World, 129; Léopold Migeotte, “Le pain quotidian dans les cités hellénistiques: À propos des fonds permanents pour l’approvisionnement en grain,” Cahiers du Centre G. Glotz 2 (1991): 19–41; Rathbone, “Grain Trade and Grain Shortages,” 45–55.

- For broader fallout from the battle of Ipsus, see Grainger, Seleukos, 121–22; R. Malcolm Errington, A History of the Hellenistic World (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008), 51–52; Waterfield, Dividing the Spoils, 172–74.

- A. B. Bosworth, The Legacy of Alexander: Politics, Warfare and Propaganda under the Successors (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002), 268, observes the order of the honors.

- Lund, Lysimachus, 84 n. 14 points out that the dearth of evidence makes it equally possible that Lysimachus’ attack could be dated to 301 in the immediate aftermath of Ipsus or to 298. Cf. Rogers, Mysteries of Artemis, 53–54.

- Stanley M. Burstein, “Lysimachus and the Greek Cities of Asia: The Case of Miletus,” AncW3, nos. 3–4 (1980): 78–79, argues that Demetrius received Miletus as a condition of his peace with Ptolemy in 297/6.

- On the relationship between these gifts and the restoration of the oracle at Didyma, see Nudell, “Oracular Politics.” Cf. Chapter 9.

- Billows, “Rebirth of a Region,” 33–44.

- Lund, Lysimachus, 128–52. Ptolemy is excused for the purposes of this discussion because his interaction with Ionia came later in the Hellenistic period.

- Burstein, “Lysimachus and the Greek Cities,” 73–75.

- The clearest example of this was Seleucus’ interactions with Miletus, which Paul J. Kosmin, The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2014), 61–67, has shown marked the far northwestern bound of his territory.

- Shipley, Samos, 173.

- Dieter Knibbe and Bülent Iplikçioglu, “Neue Inscriften au Ephesos VIII,” JÖAI 53 (1982): 130–32.

- Benjamin D. Meritt, “Inscriptions of Colophon,” AJPh 56, no. 4 (1935): nos. 1 and 2. The inscription for the walls of Colophon does include an entry for allied contribution; John Ma, “Fighting Poleis of the Hellenistic World,” in War and Violence in Ancient Greece, ed. Hans van Wees (London: Duckworth, 2000), 340–41; Lund, Lysimachus, 128–29; for a study of Hellenistic walls, see Anthony W. McNicoll, Hellenistic Fortifications From the Aegean to the Euphrates, rev. N. P. Milner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 46–48, with table 7 and 69–70.

- Rostovtzeff, Social and Economic History, 179. On the comparison with other fortifications in the time of Mausolus, see Andreas L. Konecny and Peter Ruggendorfer, “Alinda in Karia: The Fortifications,” Hesperia 83, no. 4 (2014): 739. The fortifications at Ephesus are confidently dated to the early third century; see Thomas Marksteiner, “Bemerkungen zum hellenistischen Stadtmau-erring von Ephesos,” in 100 Jahre österreichische Forschungen in Ephesos, ed. Herwig Freisinger and Fritz Krinzinger (Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1999), 413–20, while recent archaeological research at Priene, e.g., Uli Ruppe, “Neue Forschungen an der Stadtmauer von Priene—Erste Ergebnisse,” MDAI(I) 57 (2007): 271–322, has shown the evolution of the fortifications there.

- This inscription from Erythrae specifically deals with the official designated with protecting the walls against moisture damage, a process called ἀντιπλάδη. The name of this office varied by polis, being τειχοποίοι at Miletus and Priene, ἐπίσταται τεῖχον at Teos and Erythrae; cf. Chaniotis, War in the Hellenistic World, 32.

- For the estimated amount for Erythrae, see Léopold Migeotte, Les souscriptions publiques dans les cités grecques (Paris: Editions du Sphinx, 1992), 336. The contributions range from as little as twenty drachmae (l. 125) to as many as five hundred (ll. 38 and 40), and one entry that might have been more than a thousand (l. 48). For Colophon, see Migeotte, Les souscriptions publiques, 337.

- Billows, “Rebirth of a Region,” 34; Billows, Antigonus, 213; Lund, Lysimachus, 175–76. The site of the new community was likely the suburb Ephesian Smyrna; see Lene Rubinstein, “Ionia,” in An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis, ed. Mogens Herman Hansen and Thomas Heine Nielsen (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 1071. Ryan Boehm, City and Empire in the Age of the Successors (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2018), continues to credit Alexander.

- Boehm, City and Empire, 29–87. Smyrna would come to rival Ephesus in time but it was far enough away that the immediate impact was minor since most conflicts between Ionians involved borders.

- Billows, “Rebirth of a Region,” 35; Billows, Antigonus, 213; I.Ery. 22.

- Argyro B. Tataki, Macedonians Abroad: A Contribution to the Prosopography of Ancient Macedonia (Paris: Diffusion de Boccard, 1998), 56, 61, 191, 238.

- For instance, Leucippus, son of Ermogenous, and one Calladas at Ephesus; see Tataki, Macedonians Abroad, 140, 335. Rogers, Mysteries of Artemis, 56, notes that Ephesus sold citizenship to raise money.

- Billows, “Rebirth of a Region,” 36.

- Billows, Antigonus, 213–14, 217; Welles, Royal Correspondence, no. 3; Sheila L. Ager, Interstate Arbitrations in the Greek World, 337–90 B.C. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 61–64.

- Alan M. Greaves, Miletos: A History (New York: Routledge, 2002), 137.

- Ronald T. Marchese, The Lower Maeander Flood Plain: A Regional Settlement Study (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), 117–19, 166–68; Peter Thonemann, The Maeander Valley: A Historical Geography (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 295–338.

- Billows, “Rebirth of a Region,” 35; Billows, Antigonus, 217; Lund, Lysimachus, 120, 175–76; Burstein, “Lysimachus and the Greek Cities,” 75; Rogers, Mysteries of Artemis, 62–67.

- On the silting of the Cayster River, see Anton Bammer and Ulrike Muss, “Water Problems in the Artemision of Ephesus,” in Cura Aquarum in Ephesus, vol. 1, ed. Gilbert Wiplinger (Leuven: Peeters, 2006), 61–64; Rogers, Mysteries of Artemis, 65.

- Rogers, Mysteries of Artemis, 64–67.

- Pygela largely escapes mention in the ancient accounts of the refoundation, which focus on the more prominent Ionian poleis to the north, but was likely included without having been physically relocated, as suggested by Louis Robert, “Sur les inscriptions d’Éphèse: Fêtes, athletes, empereurs, épigrammes,” RPh 41 (1967): 40, and followed by Boehm, City and Empire, 147; François Kirbihler, “Territoire civique et population d’Éphèse (Ve siècle av. J.-C.-IIIe siècle apr. J.-C.),” in L’Asie Mineure dans l’Antiquité: Échanges, populations et territoires: Regards actuels sur une péninsule, ed. Hadrien Bru, François Kirbihler, and Stéphane Lebreton (Rennes: Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2009), 309; Gabrièle Larguinat-Turbatte, “Les premiers temps d’Arsinoeia-Éphèse: Étude d’une composition urbaine royale (début du IIIe S.),” REA 116, no. 2 (2014): 470–73; Giuseppe Ragone, “Pygela/Phygela: Fra Paretimologia e storia,” Athenaeum 84, no. 1 (1996): 371–74.

- Billows, “Rebirth of a Region,” 36–37.

- Billows, Antigonus, 217; Billows, “Rebirth of a Region,” 36–37. Strabo 14.29 records that the citizens of Lebedus fled to Ephesus from civil strife in Teos.

- Strabo refers to Ephesus as the largest emporium east of the Taurus Mountains and writes about the construction of a mole to narrow the harbor entrance with the idea that it would keep the harbor deep enough to accommodate large merchant ships. Engineers working for Attalus Philadelphus (r. 160–138) only succeeded in trapping the silt in the harbor (Strabo 14.1.25).

- As argued by Rogers, Mysteries of Artemis, 81–88. It was in this same period that the Milesians subordinated Didyma to the polis, but there the process accompanied the restoration of the cult; see Nudell, “Oracular Politics,” 53–56.

- Lysimachus continued to arbitrate between Ionian poleis beyond the scope of this inquiry, including between Magnesia and Priene in 287/6 and Samos and Priene in 283/2; see Ager, Interstate Arbitrations, 87–93; Sheila L. Ager, “Keeping the Peace in Ionia: Kings and Poleis,” in Regionalism in Hellenistic and Roman Asia Minor, ed. Hugh Elton and Gary Reger (Pessac: Ausonius, 2007), 45–52.

- Ager, Interstate Arbitrations, 61–64; Ager, “Keeping the Peace,” 46; Billows, Antigonus, 213–14; Welles, Royal Correspondence, no. 3, ll. 24–40, 43–52.

- On this arbitration, see Ager, Interstate Arbitrations, 67–69; Sheila L. Ager, “A Royal Arbitration between Klazomenae and Teos?,” ZPE 85 (1991): 87–97.

- Lund, Lysimachus, 143–44.

- On Lysimachus’ other administrative measures, see Lund, Lysimachus, 144–46.

- Jeremy LaBuff, Polis Expansion and Elite Power in Hellenistic Caria (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2015).

- Ma, “Fighting Poleis,” 341–44; cf. John Ma, “Une culture militaire en Asie Mineure hellénistique?,” in Les cités grecques en Asie Mineure à l’époque hellénistique, ed. Jean-Christophe Couvenhes and Henri-Louis Fernoux (Tours: Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, 2004), 199–220; Thibaut Boulay, Ares dans la cite: Les poleis et la guerre dans l’Asie Mineure hellénistique (Pisa: Fabrizio Serra Editore, 2014); Chaniotis, “The Impact of War,” 122–41.

- On this inscription, see Louis Robert and Jeanne Robert, “Une inscription grecque de Téos en Ionie: L’union de Téos et de Kyrbissos,” JS (1976): 188–228; Jean-Christophe Couvenhes, “Les cités grecques d’Asie Mineure et le mercenariat å l’époque hellénistique,” in Les cités grecques en Asie Mineure à l’époque hellénistique, ed. Jean-Christophe Couvenhes and Henri-Louis Fernoux (Tours: Presses universitaires François-Rabelais, 2004), 92–93. Although this inscription is often seen as coercive, William Mack, “Communal Interests and Polis Identity under Negotiation: Documents Depicting Sympolities between Cities Great and Small,” Topoi 18, no. 1 (2013): 105–6, characterizes it as the product of a negotiation between the two sides and notes that such treaties established protections for the weaker party.

Chapter 8 (158-181) from Accustomed to Obedience?: Classical Ionia and the Aegean World, 480-294 BCE, by Joshua P. Nudell (University of Michigan Press, 03.06.2023), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.