The inaccuracies function on a series of imbricated planes, with interwoven agendas.

By Dr. April Harper

Associate Professor of History

SUNY Oneanta

In 1952, Charles Singer published his great criticism of medieval medicine in which he set the tone for the treatment of the subject for the next two, and arguably four decades. He decried it as ‘the last stage of a process that has left no legitimate successor, a final pathological disintegration of the Greek system of medical thought’.1 A decade later he had not changed his mind when he wrote that medieval medicine was ‘demonstrative of the wilting mind of the dark ages’.2 He argued it ‘lacked any rational element which might mark the beginnings of scientific advance’.3 Medical historians, especially from the 1990s onward, have challenged Singer’s assertions and successfully shown the efficacy of many medieval medical treatments and recipes. Perhaps more importantly, they have sought to reconstruct the history of Western medicine, not as a series of peaks and troughs, in which the Middle Ages represents the greatest nadir, but as a transformation of theories connecting the practices of ancient, medieval and Renaissance medicine, in order to accurately portray the development of the field.4 While important work is being done to strip the prejudice and stigma from the subject, it is the inaccuracies in the portrayal of medieval medicine, science and technology that provide key insight into modern fears and conflicts. The inaccuracies function on a series of imbricated planes, with interwoven agendas acting: on the most basic level, as a signifier of the medieval in modern media and the imagination; on a more complex level, as a means to reinforce a comfortable narrative of historical progress in which the primitive and barbarous medieval is comfortably dissimilar to our own modern world; and lastly, at a deeper and arguably far more disturbing level, is the means by which these inaccuracies allow us to portray the Middle East as a backward place that has refused to develop past the medieval and by its rejection of the modern, has rejected the science, technology and philosophy that has defined humanism and humanity in the West and therefore validates the dehumanization of Muslims who, having once been on the forefront of all scientific advancement, chose to remain medieval, rather than embrace Renaissance and Enlightenment.

Singer’s argument that medieval medicine was ‘the last stage of a process that has left no legitimate successor’5 establishes an estrangement so severe between the science, medicine and technology of the modern world and that of the medieval, that there is no discernible link between the two periods. It is what the most obvious and common use of medicine in modern media (especially television and film in which the time available for world-crafting is limited) likewise accomplishes – the immediate acknowledgement that the audience is experiencing a radically different time and mindset that is nothing like our own. It is immediately foreign and immediately medieval in the depiction of its lack of scientific technology and the ubiquitous image of its medicine as brutal, superstitious and often magical. This is important for what Andrew Elliott describes in his Remaking the Middle Ages as ‘authenticity’ – part of a medieval imaginary in which certain sets of signs form a recognizable idea. It creates a ‘feel’ of medieval.6 Science and technology, or the lack thereof, are just as important as signifiers of what is medieval as depicted in modern media as is a castle, knights on horseback, dirty peasants or even dragons. Science and technology are a key divide between the perceived medieval and modern.

As a signifier of the medieval, medical treatment in modern media productions is often depicted to compliment a perceived brutality of medieval life. The medieval reality of hospitals (depending on time period and geographic location), educated practitioners, medication and even cleanliness must remain absent from this constructed medieval world entirely in order for the medieval imaginary to be fully constructed.7 For example, in the popular TV show Vikings, a character named Torstein is hit with an arrow in the upper arm and in a very masculine fashion, breaks it off, but the wound becomes infected and one afternoon, while sitting around the fire, he asks his friends to cut off his arm ‘because he never liked it anyway’.8 Several men stand up, ready to do the procedure, but he asks for one man in particular to do the job, not because of his medical knowledge but because he had wronged him before and it seems to be a kind of statement of trust. The patient is held down by multiple men, an axe is heated red hot to cauterize the wound, and a successful amputation is done in a few neat whacks. The cinematic demands to showcase brutality and primitivism and celebrate the hyper-masculinity of the battlefield and Viking culture are satisfied.

Chronicles and other non-medical texts of the Middle Ages, such as those by Jean de Joinville, the crusader and author of The Life of Saint Louis who was excited to have returned from battle with ‘only five arrows’ stuck in him,9 and the poetry of Norman poet Ambroise, who describes King Richard looking ‘like a hedgehog’ from the amount of arrows in him, detail just how common arrow wounds were and that soldiers, and indeed their medieval audience knew better than to break off an arrow.10 Arrowhead extraction, though painful, was common and largely successful, as was treatment of infection. The texts of battlefield surgeons illustrate the wide variety of arrowheads and other ballistics that any surgeon needed to know how to remove. The battlefield often proved a fertile ground to train in surgery, to pioneer new techniques of arterial stitching and wound management. Battlefield weaponry was changing as fast as battlefield medicine could adapt, though arrows remained a core concern and standard subject in all surgical texts. Detailed procedures clearly show an understanding of the nature of such wounds and their particular risks, depending on whether they had targeted flesh, artery, joint, nerve or bone. The surgeon John Bradford’s innovative solution in extracting the head of a bodkin that had come loose from its shaft after penetrating the future Henry V of England’s face and lodging in the interior bone of his skull shows not only a deep understanding and familiarity with arrow wounds but also the understanding that the worst case scenario was an arrowhead that had come loose from a shaft, or a broken shaft left in the body.11 Amputation, that the character of Torstein so easily embraced, was a last resort and would have been carried out by a specialist. Evidence of this kind of specialization and practice exists in Scandinavia and England as early as the ninth century. By the eleventh century, the Muslim physician Al-Zahrawi, latinized as Albucasis, wrote a detailed procedure for amputation, describing the process of ligature and the problems and necessary procedural differences depending on the location of amputation, different tissues and the presence of a healthy or bad bone.12 While the inaccuracy in the presentation of Torstein’s amputation is deeply problematic for historians of medicine, as it continues and reinforces the misinformed image of the brutal ignorance of medieval medicine, for medievalists, it is the power of this image combined with other signifiers, such as the hyper-masculinity of the Vikings, the adherence to codes of honour, rules of feuding and even choice of weaponry, that provides valuable insight into the creation of the ‘medieval’.

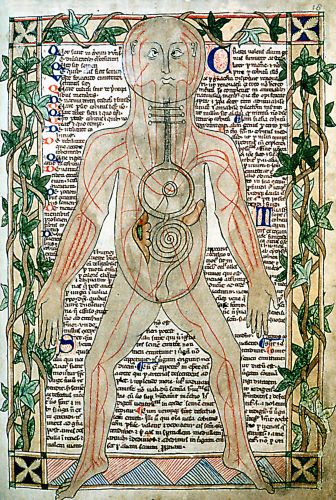

While brutality is one of the common ways in which the medicine of the Middle Ages is instantly identifiable to a modern audience, the medieval imaginary is often crafted through a complete sacrifice of both logic and realism in the depiction and acceptance that the only effective medieval medicine is linked to magic. There are many examples of this, from the slight to the fantastical. In the TV series Merlin, for example, the young sorcerer is given a book of magic in the first episode.13 As he thumbs through it, he is amazed by the spells and the screen settles on a particular page of the magical text that historians of medicine will recognize as the entry for the herb henbane in the Old English Herbarium, a ninth-century, Anglo-Saxon medical text. The vibrant colours; spidery, calligraphic Anglo-Saxon written text, and images of plants and animals seem to be enough to render it suitably magical in the audience’s mind. Countless other television shows and films rely on the connection between medicine and sorcery ranging from the simple references akin to that in Merlin to the wilder images and dangerous necromancy of shows like Game of Thrones. Many recent television miniseries, including The Last Kingdom, Game of Thrones and The World Without End, have developed this trend to tap into a kind of pseudo-feminist Romanticism of the imagined medieval pagan past. In these productions, the inadequate medieval medicine practiced is the preserve of men whose patriarchy proves impotent in the face of real disaster. The only capable healers in these dramas are female, often greatly sexualized, pagan priestesses or witches, who wield true, though often dangerous, power. Extremes are often taken to craft this image that seems far more unbelievable than the efficacy of medieval medicine. Yet, the power of these signifiers is such that directors, writers and audiences readily engage in a kind of suspension of disbelief that renders them willing to accept that this period is so removed from history that it has also become removed from reality and that in this imaginary, magic was more real, more common and more efficacious than actual medieval medicine.

The second, and more complex level at which the images of medieval medicine interact is upon historical narrative. While the inaccuracies functioning as signifiers create the idea of the Middle Ages as comfortingly dissimilar from our own, they are also able to function simultaneously at deeper levels, to reinforce a false narrative of historical progress that allows us to avoid our own scientific shortcomings by giving credence to Singer’s next claim – that medieval medicine ‘lacked any rational element which might mark the beginnings of scientific advance’.14 This narrative is usually promoted by the use of two major themes in medicine: the incurable medieval disease that is easily cured in the modern period and ineffective and/or dangerous medicine of the Middle Ages.

The first of these themes – the incurable – is especially effective as it plays upon the universal human fears of the unknown and death. These scenes are often highly emotionally charged by a seeming senselessness to deaths that are easily preventable in the modern world. While many advancements in medicine were made within the Middle Ages that improved the quality of life and in some cases, even saved the lives of patients, such as fistula, hernia and cataract surgeries, and skin grafting, modern media rarely focuses on highly risky surgeries, such as bladder stone removal to illustrate historical progress. Instead, it is the inability to help the most vulnerable that helps further this agenda the most. This may account for why images of sick children and especially women dying in childbirth feature prominently in this category. The trope is a common backstory for tragic male figures who have lost their families in childbirth-gone-wrong and, as most famously depicted in Robin Hood Prince of Thieves (1991), provides a dramatic scene in which even the martial prowess of a story’s hero cannot save a woman who struggles to give birth.

Outside of TV and film, there are webpages, blog and articles devoted to a similar image of medieval childbirth as terrifying and deadly. Supposedly historical blogs feature titles such as ‘The Historical Horror of Childbirth’;15 a popular health magazine runs the story ‘Medieval Pregnancy Advice That Is Beyond Disturbing’;16 and the Daily Mail headlines an article ‘Medieval Woman Gave Birth After Death’.17 The goal of these sensationalist headlines and the images of the inability of medieval medicine is to save these women through what by modern standards is seen as a simple caesarean delivery, to disparage the Middle Ages and comfort the audience with the knowledge that progress has been made. Indeed, each of the written sources – blog, journal and newspaper – ends with an assurance that things are better today. However, childbirth is still one of the most dangerous events in a woman’s life, with approximately 143 deaths per 100,000 live births, making it the fifth greatest cause of death for women, according to global data collected for the year 2015.18

Childbirth was dangerous in the Middle Ages, and although access to medical care varied due to financial status, social class and even geography, women were commonly attended by midwives and royal women often had personal surgeons and physicians who were well-educated in gynaecology. Physicians and midwives were familiar with the various fetal presentations, including dangerous positions, such as a breech birth.19 While caesarean births were originally developed as a means to save a baby after the death of the mother during labour, by the fifteenth century, caesarean births in which the mother and child could both be saved are recorded in texts.20

There may be evidence of successful surgeries being practiced earlier, as rabbinical texts describe the practice carried out with both maternal and child survival in Jewish communities as early as the second century AD.21 Midwives who were ignorant of possible complications of childbirth could be found guilty not only of malpractice but of murder if their actions or lack of skill was at fault in a maternal death, as illustrated in the fourteenth-century case of a French midwife named Philipa, who attempted to remove the afterbirth of a woman by pulling on the still-anchored umbilical cord. The legal text in which this case is recorded describes her actions as ‘crude [. . .] brutal and cruel’, implying that this kind of ignorance was against standards of practice and certainly not the norm.22 By not waiting for the arrival of a more experienced midwife and carrying out actions that led to the death by haemorrhage of the mother, Philipa found herself on trial for murder. Despite the historical reality of obstetric good practice, film, television and the media continue to conflate many images of life in the Middle Ages with that of the American Wild West and it is especially evident in the erroneous depiction of women giving birth in isolation and the dehumanized, uncaring treatment given to women in childbirth that is more akin to the treatment of livestock than one’s wife. This portrayal has little in common with the medieval reality of village life, the community nature of childbirth and the common presence of educated and/or experienced female attendants, midwives and/or physicians.23 The inaccurate portrayal of hopelessness and tacit acceptance of needless death is critical, though, in forming the narrative of progression, even when the same condition remains a threat to the modern audience. As long as there are perceived differences or the option of scientific recourse, there is a distinguishable difference and the narrative can be confirmed.

This highly effective imagined combination of despair and inadequate medical response can be combined with an additional attribute that signifies historical progress – compassion, or rather the medieval lack thereof, in order to create a powerful ‘proof ’ of not only our scientific, but moral distance from the medieval. Perhaps the best example of this is in the image of the Plague. Understandably, filmmakers and screenwriters are intrigued by the plague, just as historians, and especially historians of medicine, are profoundly interested in the impact it had upon medical practice, theory and regulating institutions. The actual terror the Black Death inspired in medieval people cannot be understated. Contemporary chroniclers, such as the Irish friar John Clynn, described himself as ‘waiting among the dead for death to come’. He ends his work by stating, ‘I leave parchment for continuing the work, in case anyone should still be alive in the future and any son of Adam can escape this pestilence and continue the work thus begun.’24 Fear led many of the wealthy to flee the cities for their countryside estates, hoping to outrun the outbreaks, as the setting of Boccaccio’s Decameron illustrates. Some left their homes entirely and, as the Bishop of Bath and Wells bemoaned, it was impossible to recruit new priests to replace those who had died while tending to the ill.25 The misunderstanding of the plague’s origin led to outbreaks of violence against minorities and strangers.26 The problem of the inaccuracies of modern media is not that it portrays some or even all of these responses in its depiction of the Black Death but that it presents these very real fears as the status quo in the Middle Ages, not the world-upside-down experience it really was.

The use of the plague, in film and television particularly, is disturbing as it seems to have become an all-inclusive image of life in the Middle Ages, especially in Hollywood blockbuster culture. Indeed, there often seem to be two overarching themes for medieval productions: war or plague and sometimes war and plague as shown in films such as The Seventh Seal (1957) and Season of the Witch (2011) among others. The combination of themes presents a past in which life was held cheaply and those who did survive lived in squalor, filth and abject fear. The perceived baseness of human nature in the Middle Ages that is portrayed in these films is shown through terrifying acts of violence and the wholesale neglect of the ill and destitute. Even comedies that address the Black Death, such as Monty Python’s Holy Grail, show a disregard for life, the elderly are depicted as a burden, children are too many and entirely replaceable and no one mourns the dead.

It also shows little of the attempts to deal with this epidemic. While films like Season of the Witch link the plague to the revenge of downtrodden pagans and portray the authorities as crazed zealots hunting down young women, in reality, the greatest medical minds in Europe’s leading universities were attempting to find scientific rationale for the plague.27 Historical outbreaks of other plagues were studied; surgeons and physicians, including the Pope’s own physician, began to write treatment protocols that advocated frequent bathing, the use of vinegar washes, frequent washing of clothing and so on, and civil government began to step in to regulate at-risk areas and implement quarantines, waste disposal and mandate that bodies must be placed in a coffin before leaving the house, the coffin must be sealed with nine-inch nails to prevent it from coming open during burial or in high water table areas and that all graves be dug a minimum of six feet deep in order to not interfere with drinking water.28 The terror of the Black Death was deeply felt, and while a cure evaded medieval physicians, fifteenth-century Europe was far from the Monty Python-esque image of a mud-soaked hovel. Rather, at the onset of the plague, Europe was stable, prospering, enjoyed a level of education previously unknown, had seen the establishments of universities as well as hospitals and had experienced four renaissances. While the objective of creating a myth of historical progress is achieved through inaccuracy, it is interesting to note that the image of the period as one in which primitivism supersedes all rational thought and humanity reverts to some imagined dark age in which hunger, filth and a mass grave await us all as far more in common with images of the holocausts and post-apocalyptic, dystopian nightmares of our postmodern society than it does with an accurate medieval past. The power of this ‘authentic’ rather than ‘accurate’ image may be two-edged at this level – providing comfort in the historical narrative of progress, but also admonitory in purpose, warning what should befall us if we cease to continue to progress.

The second of these is themes is historical narratives promoting the ineffective or dangerous nature of medieval medicine. While audiences are often willing to suspend disbelief in order to accept magical medical cures, when pressed to witness real medieval medical treatment, the media images of doctors as bumbling fools, or pedantic churchmen, whose treatment is quite commonly ineffective or even counter-productive, seem to resonate so strongly that modern audiences are averse to admit any value to the practice. Instead, emphasis is given to the futility of the treatments: the perceived disgusting nature of suitably ‘medieval’ ingredients such as dung, beer and grease, and the copious amount of praying that often accompanies certain procedures or processes. Even today, when some medieval medical treatments are found to be most efficacious, with better results than modern medicine, acceptance and enthusiasm are low. For example, in 2015, the University of Nottingham combined experts in molecular biology and Anglo-Saxon studies to work on a recipe for eye salve from Bald’s Leechbook, a ninth-century Anglo-Saxon medical text. The simple ingredients of onion, garlic and wine were mixed with gall from the stomach of an ox and allowed to sit in a brass container for nine days. The resulting mixture has proven to be an incredibly strong antibacterial tincture that has proven more effective at fighting MRSA than modern medicines. Interestingly, however, media attention has focused on the humble and medievally ‘gross’ ingredients and the shock of the researchers involved at its efficacy. The pejorative presentism surrounding the medieval nature of the recipe is found in titles of articles such as ‘Getting Medieval on Bacteria’, The Smithsonian’s ‘This Nasty Medieval Remedy Kills MRSA’ and from The Conversationalist, an academic online journal, the article ‘Why I wasn’t excited about the medieval remedy that works against MRSA’. The latter, written by the well-respected classicist Helen King, employs an argument from fallacy in which she pairs a very brief summary of the project in a tone that all but denies its results, with a much longer description of the more fantastical recipes found within the Leechbook that include charms or supernatural elements, in an attempt to discredit the efficaciousness of Anglo-Saxon medicine and to argue for the fruitlessness of continuing such research. This is remarkably interesting, considering that the same year, the chemist Tu Youyou received the Nobel Prize in Medicine for her similar work in researching efficacious treatments from ancient Chinese medicine. However, comments on a variety of pages seem to echo those of Dr King, such as this comment from David Wright, another classicist:

The odds are against anything spectacularly effective having been ‘lost’ [. . .] effort should be spent on 21st century remedies [. . .] To those who say this is ‘culturally insensitive’ I merely shrug and say ‘Look at mortality rates for now well-understood conditions, then and now. Would you rather be treated by the old, or new, methods? And your children? I rest my case.’29

The appeal of the fallacious argument and fear-mongering in Wright’s comment is not unlike those voiced by readers in the comments section of various articles covering this experiment:

Find something that worked in ages past and turn it into something else that will cause ‘unfortunate side effects’ which will require more drugs to alleviate. Sort of explains the whole bit about Pharma (cology) originating from the Latin word for ‘sorcery’.30

A lot of good people died because of those treatments. That is not allowed today. They did their best, but, have you ever looked at our lifespan and compared it to the days of the healers?31

Let’s see, possibly because its [sic] a foul nasty brew, and no one is going to apply to their skin? Also, it may not be something in itself that can be ingested, and if it possible, if it’s that horrible, good luck swallowing it and not vomiting. So yes, they need to see what in the slime is doing the job and than [sic] replicate it and put it in a usable form.32

Why mess with stinky stuff ?33

While we might be amused or intrigued by the efficacy of some medieval treatments, such as the Anglo-Saxon eye salve, by and large audiences can feel comforted by this topos of the ineffective, dangerous and disgusting pharmacopeia that not only acts as a signifier, creating an immediately identifiable medieval world that is comfortingly distinct from our own, but affirms the present as progressive, distinct, logical, scientific and less vulnerable. Louise D’Arcens and Clare Monagle aptly note, ‘Since the Renaissance, whenever modernity has found itself in crisis – when the shibboleths of rationalism, secularism, capitalism and the nation-state seem to be coming apart at the seams – fantasies of the medieval have suggested a mostly frightening, though sometimes alluring, vision of what the alternatives to modernity might be.’34 No matter what we face in the modern age, we have evidence that we have survived worse and we have the tools of medicine, science and technology to overcome our present challenges. By constantly portraying the Middle Ages as a period of medical and scientific backwardness, we

affirm a progressivist model of history which emphasises the breach between periods, and arguably validates and advocates for modernity for its implicitly more evolved culture [. . .] the medieval period is evoked as a superseded age of ignorance and cruelty [. . .] provid[ing] a reservoir of images and ideas that have been crucial to defining what it is to be modern.35

Thirdly, and perhaps the most important level at which the inaccuracies of medieval medicine, science and technology impact the modern world is in the interaction of these deeply imbedded signifiers and narratives of modernity with the leitmotif of the medieval technologically advanced Muslim. The image of Muslims as a people who once held advanced technology and engaged in cutting-edge science but through laziness and cultural and religious prohibitions ceased to progress is more than Orientalism or even popular Islamophobic bigotry. It is far more dangerous. Andrew Elliott includes in his work, Medievalism, Politics and Mass Media, a political cartoon in which a directional sign that points to the ‘Middle East’ is vandalized to read ‘Middle Ages’ instead. He notes how

such a syllogism has important ramifications in our reclassification of the world not into geopolitical entities but also into a chronological idea of progress [. . .] Even the language we use to divide the world bears witness to such chronological division when, for example, we divide the world into developed and developing worlds, a metaphor whose implicit logic is temporal and dependent on our seeing the so-called ‘developed’ worlds of the West teleologically as the most fulfilled and modern point of evolution, while the others languish in a pre-modern state of ungentrified barbarity.36

The perceived ‘barbarity’ of Islam is key not just to the defamation of Islam, but to the dehumanization of all Muslims. Much attention has been given, especially in the press, in television and media, to the physical violence that the Islamic State has engaged in and even its own use of nostalgia, that consistently references the medieval. And while numerous historians and political commentators have repeatedly pointed out, as John Terry aptly states, ISIS is ‘not medieval – it is viciously modern’, the power of calling it and its actions ‘medieval’, ‘tempts us to define the group’s special barbarism as something from the past that should be eradicated because, by God, we’ve progressed and are therefore advanced as a people.’37 Indeed groups like IS and the Taliban ‘becomes something not only out of place but, more importantly, out of time’.38 Chris Jones argues:

to call the perpetrators of these crimes, and the societies that foster them ‘medieval’ is to place them on the other side of a temporal fault-line imagined to run through history. ‘We’ are ‘modern’ and therefore civilized and unable to countenance these forms of violence; ‘they’ are ‘medieval’, pre-modern, and have not progressed through the same process of historical evolution that would render such acts unthinkable. In effect ‘they’ are inhuman, or rather ‘pre-human’ if being human means having gone through the later stages of European history (and it is a metaphor which is entirely Euro-centric), which Humanists first labelled ‘the Renaissance’, and subsequently that most savage of times, ‘The Enlightenment’. There is already a substantial history of this language of medievalism being used to describe the opponents of the West. On occasions, in denying individuals their humanity. [. . .] The medievalist academic Bruce Holsinger has analysed how the so-called ‘torture memos’ of the U.S. State argue that the Taliban is an apparently ‘feudal’ organization, and one which has therefore failed to evolve into a modern state, and as a consequence its ‘medieval’ members do not qualify for the protections of the Geneva Convention while under detention at Guantanamo. The logic is shockingly brutal: ‘medieval’ people are not modern humans; Human Rights do not need to be extended to ‘pre-humans’.39

Interestingly, the majority of effective, non-magical, medical treatment in medieval film and TV productions is carried out by Muslims. In 2001, director Spike Lee spoke publicly on the cliché of the ‘magical black man’ in film and TV, noting a longstanding tradition that the only acceptable character of colour has to be the exceptional, a trope commonly referred to as ‘the magical black man’.40 In medieval film, this exceptional character is often cast as a Muslim, though Hollywood occasionally conflates the two, as found in Morgan Freeman’s portrayal of the black, Muslim sidekick to Robin Hood in Kevin Costner’s Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991).41 While we might be tempted to refer to this trope as the ‘magical medieval Muslim’, it is his (to date, this figure is universally male) complete lack of magic that marks him as different and exceptional. The inclusion of a non-magical though nevertheless fantastical, scientifically minded, technologically advanced Muslim often acts within the script as a kind of deus ex machina device as illustrated in Freeman’s character. Azeem, with his knowledge of gunpowder and his possession of technology, such as the telescope, is an invaluable sidekick who gives Robin Hood an advantage over his less-developed, Western European foes. This superior knowledge also enables Azeem to save the life of Little John’s wife, delivering her child by Caesarean. As previously noted, Caesarean sections were most likely not performed with maternal survival before the fifteenth century. Similarly, Muslims did not acquire the knowledge of gunpowder until the late thirteenth century; telescopes were first developed in the early seventeenth century in the Netherlands. If these were just isolated incidents of such misattribution, one might be tempted to just blame them on a film that is already fraught with a wide variety of inaccuracies. However, this kind of chronological misappropriation of scientific goods and technologies is not unusual and affects not just fantasy film and fiction, but has infiltrated official narratives of the history of science. Professor Nir Shafir, an expert on Ottoman science and medicine, has recently noted the production and circulation of many images that have been intentionally changed on the internet to imply Muslim technological inventions and advancements that are being attributed to the Middle Ages, though, in some cases, hundreds of years before the actual development of some technologies. While we may expect this of the unregulated nature of the internet, more disturbingly, he has also found a similar wide variety of misrepresentations in art and in heritage settings.42 These include alterations, such as an original painting depicting an Islamic astronomer using a sextant that has now been over-painted to show him using a telescope; medical images drawn in a medieval style, but with modern knowledge of anatomy; paintings of world maps that contain details only known post-nineteenth century; and even updated recreations of supposedly medieval scientific instruments and machines. While some of these forgeries are found online or in tourist shops, others have worked their ways into museums and libraries such as the Museum for the History of Science and Technology in Islam in Istanbul and the ‘Science in Islam’ exhibition website at the Museum of the History of Science in Oxford. Even the Wellcome Collection in London, which specializes in the history of medicine, was found to have what Nazir describes as ‘several poorly copied miniatures demonstrating Islamic models of the body, written over with a bizarre pseudo-Arabic and with no given source’.43

While these pseudo-scientific modernizations and forgeries may seem bizarre, they have a firm footing in medievalism from the nineteenth century onwards. In John Ganim’s work, Medievalism and Orientalism, he notes that the

European powers mounted enormous international exhibitions, displaying both their technological and economic power and their newly acquired colonial possessions. [. . .] As it turns out, world’s fairs in the nineteenth century not only celebrated the triumph of European modernity, they also displayed aspects of Europe’s own medieval past. From the Great Exhibition of 1851 onwards, medieval reconstructions were among the most popular exhibits at world’s fairs.44

While medieval installations may seem to be out of place in such display, the fairs’ focus was not only to showcase advances in technology, but to celebrate empire and Western cultural superiority over the colonized. The fairs had displays of handicrafts and items from colonized lands that stood in stark contrast to the modernity of the Western European installations, but bore striking resemblance to the mocked up Western medieval goods often showcased right next to them. The medieval and the colonized Muslim were displayed side by side.

The link between medievalism and orientalism was already well-established in art and literature, but was now connected in science as well. Ganim illustrates how firmly this connection was made in his example of an address given to the Workingman’s College in 1881:

‘All the heaped up knowledge of modern science, all the energy of modern commerce, all the depth and spirituality of modern thought, cannot reproduce so much the handiwork of an ignorant, superstitious Berkshire peasant of the fourteenth century, nay of a wandering Kurdish shepherd.’45

This teaming of the modern Middle East with the Middle Ages contributed to a growing trend for scholars to shift between the two fields of study and a great deal of conflation to take place. As Ganim argues, ‘The Middle Ages represented in time what the Orient represented in space, an “other” to the present development of western civilization.’46

While the connection between the science and technology of the East and that of the medieval was firmly established in the nineteenth-century fusion of orientalism and medievalism, it seems confusing why modern productions that embrace both these analytical approaches would choose to show Islam as advanced and even attribute developments from the European late Middle Ages and early modern period to it. The answer may lie in the West’s devotion to the Whiggish narrative of progress. As Chris Jones argues, the Italian humanists’ desire to separate themselves from past resulted in them:

denigrat[ing] this ‘middle age’ as a period of ignorance and backwardness precisely in order to promote themselves, and the new age in which they had decided they were living, as more ‘advanced’. Styling the previous ten centuries of human achievement as barbarically ‘medieval’ was, in short, a hugely successful piece of spin – a Public Relations coup for a new philosophical ‘brand’ being launched by an elite group of western Europeans, [. . .] For ‘the Middle Ages’ is not a neutral historical term. It’s a metaphorical way of understanding history as a process of evolution, by which a less advanced culture has to (or perhaps fails to) progress from a ‘medieval’ period to modernity.47

The display of the inferior West and the technological superior, though still medieval, Islam fuels a two-fold modern desire to show the incredible progress of the West, while showing stagnation of Islam. The eagerness of the West to advance and Islam’s inability to do so is especially evidenced in the films The Physician (2013) and in Kingdom of Heaven (2005).

In The Physician, a young Englishman travels to Persia in the eleventh century to learn from Avicenna, one of the greatest medical minds of the period. It is a deeply problematic film in many ways, for its portrayals of race, for its bizarre conflation of historical events and its complete lack of understanding of any aspect of medieval medicine. While the inaccuracies are rampant throughout the film, it is the relationship between the Englishman and his Muslim teacher that proves more important for how these inaccuracies function at this third level. The student surpasses not only all his peers in class but then begins to rival his master. He not only perfects many of Avicenna’s theories, but is found arguing with his teacher when the Muslim proves too cowardly to push forward in their discoveries or to challenge previous beliefs. Avicenna is comfortable with his reputation and satisfied in achieving a high level of respect within the field, but lacks drive and bravery to continue to progress. In the end, the Englishman leaves the school, riding away as the compound slams its doors shut under the new rule of a conservative Muslim ruler. The message is clear: Islam fears modernity and it is up to the Westerner to continue the progress begun by Islam.

Similarly, in Kingdom of Heaven, a narrative of Western progress is set against the image of a hesitant and wilfully stagnant Muslim east. This is especially obvious in the protagonist, Balian’s, first encounter with the East. As Paul Sturtevant notes:

In this scene, Balian surveys his newly inherited lands, and, finding them well-populated but parched, orders his men to build a well. Balian himself leads the team of welldiggers [. . .]. Water is struck, and in the following scenes, his lands are transformed into and oasis paradise. This scene is controversial because it calls back to an imperialist, Orientalist and colonialist narrative wherein Europeans were needed to ‘make the desert bloom’ – bringing civilization to the Arab world [. . .] This sets up a problematic paradigm where without dictates from a strong (European) leader, the people are so listless that they will not even work together to provide for their most basic needs.48

The complete lack of a desire to progress marks the Muslims throughout the film, as does their need to have Europeans develop and even re-teach them their own once-superior science. The message is clear – Middle East is medieval and desires to remain so, while the West, even when medieval, is progressive, active and leading the way to modernity.

There is a terrible power in interpreting, labelling and portraying not only the violence perpetrated by Islamic groups as ‘medieval’ but also their motivations, their worldview and their culture, as ‘medieval’. It marks them as hopelessly different, not human. In an age where science becomes one of our greatest signifiers between our past and present, periods such as the Renaissance and the Enlightenment act as a kind of lock in the river of progressivism, not only enabling forward momentum but raising Western culture as well and ensuring against any backslip.

In conclusion, science and technology are a key divide between the perceived medieval and modern. In the preface to his collection of essays, Jacques Le Goff describes the idea of a medieval period ‘dying under the blows of the industrial revolution’49 and no matter the inaccuracy of that statement, it does bely a pervasive image of a lack of scientific understanding or development in the Middle Ages. The inaccuracies act on the most basic level as powerful signifiers – a bubbling potion, a spell-book, the mention of a disease long-eradicated or no longer threatening, a wound from weapons no longer used; these create an immediately identifiable medieval world that is comfortingly distinct from our own. However, when applied to medicine, science and technology, inaccuracy is not only a general tool for world-crafting, but functions on far deeper emotional and cognitive levels, impacted by nationalism and fear. Accurately portraying a medieval European past that was in possession of logical, rational, scientific medicine, that was scientifically minded and technologically innovative is simply counterproductive to the progressivist, presentist narrative demanded by many modern audiences and so filmmakers, television directors and the media continue to engage in the comfortable Western narrative of progress and cultural superiority. That narrative serves to create an idea of a Middle Ages that is dissimilar enough from our present that, despite our current scientific shortcomings, we can map a trajectory of success over nature, disease and the unknown. It allows Islam’s early scientific success to be not a challenge to the superiority of the West but, when paired with the image of its current state of stagnation, to become a vivid image of regression – a society that has not evolved socially, technologically, philosophically or morally. This final stage in the use of inaccuracy in the portrayal of medieval medicine is the most powerful and potentially the most destructive, as the imbrication of the various uses and effects of the inaccuracies reduces the image of the Muslim to signifiers of a past age and as evidence confirming a dangerous metanarrative that not only includes Western progress, but the admonition of what happens if the West fails to progress or tolerates those it sees as doing so.

Endnotes

- J. H. G. Grattan and Charles Singer, Anglo-Saxon Magic and Medicine (London: Folcroft Library Editions, 1952), 92.

- Charles Singer, A Short History of Medicine (New York: Oxford University Press, 1962), 31.

- Ibid.

- M. L. Cameron, Anglo Saxon Medicine (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 1993); Monica Green, The Trotula: An English Translation of the Medieval Compendium of Women’s Medicine (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002); Mirko Grmek, ed., Western Medical Thought from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, trans. Antony Shugaar (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1998); A. Wear, Lawrence Conrad, Michael Neve, Roy Porter, and Vivian Nutton, The Western Medical Tradition: 800 BC to AD 1800 (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 1995) and Vivian Nutton, Ancient Medicine (New York: Routledge, 2004).

- Grattan and Singer, Anglo-Saxon Magic, 92.

- Andrew Elliott, Remaking the Middle Ages (Jefferson: McFarland, 2011), 178.

- Medical care available depended largely on geographic location and the time period in question. See Grmek, 1998 and Wear, Conrad, Neve, et al., 1995.

- The Vikings, ‘The Wanderer’, Season 3, Episode 2, (2015), [TV programme] History Channel, 26 February.

- Ambroise, Estoire de la Guerre Sainte – Histoire en Vers de la Troisieme Croisade (1190-1192), ed. G. Paris (Paris: Imprimerie nationale, 1897), 311.

- Jean Joinville, The Life of St Louis (London: Sheed and Ward, 1955), 84.

- H. Cole and Tig Lang, ‘The Treating of Prince Henry’s Arrow Wound, 1403’, Journal of the Society of Archer Antiquaries (2003): 95–101.

- Piers Mitchell, Medicine in the Crusades (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 153.

- Merlin, ‘The Dragon’s Call’, Season 1, Episode 1, (2008), [TV programme] BBC One, 20 September.

- Grattan and Singer, Anglo-Saxon Magic, 92.

- Miss Cellania, ‘The Historical Horror of Childbirth’, Mental Floss, 9 May 2013. Available online: http://mentalfloss.com/article/50513/historical-horror-childbirth , accessed 13 October 2019.

- L. Douglas, ‘Medieval Pregnancy Advice That Is Beyond Disturbing’, Healthyway, 5 April 2007. Available online: https://www.healthyway.com/content/medieval-pregnancy-advice-that-is-beyond-disturbing/, accessed 13 October 2019.

- C. MacDonald, ‘The Haunting Remains of a Medieval Woman Who Had a Hole Drilled into Her Skull at 38 Weeks Pregnant and “Gave Birth” AFTER She Was Buried’, Dailymail.com , 10 December 2018. Available online: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-5547203/Medieval-woman-hole-drilled-skull-38-weeks-pregnant-gave-birth-death.html, accessed 13 October 2019.

- This data is based on figures worldwide. Maternal death figures must not to be presumed to represent only the third world, as shown in the article’s statistics revealing the United States to have the highest maternal death rate in the developed world with approximately nineteen maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. See Ellison, Katherine; Nina Martin, ‘Lost Mothers: Severe Complications for Women During Childbirth Are Skyrocketing — And Could Often Be Prevented’, ProPublica, 22 December 2017. Available online: https://www.propublica.org/article/severe-complications-for-women-during-childbirth-are-skyrocketing-and-could-often-be-prevented, accessed 14 July 2018.

- Monica Green, The Trotula and Monica Green, Women’s Healthcare in the Medieval West (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002).

- Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, Not of Woman Born: Representations of Caesarean Birth in Medieval and Renaissance Culture (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1991).

- Jeffrey Boss, ‘The Antiquity of Caesarean Section with Maternal Survival: The Jewish Tradition’, Medical History 5, no. 2 (1961 April): 117–31.

- Monica Green, ‘The Art of Medicine: Midwives and Obstetric Catastrophe’, The Lancet, 372. https://www.thelancet.com/pdfs/journals/lancet/PIIS0140-6736(08)61467-1.pdf, accessed 14 July 2018.

- Monica H. Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine: The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- R. Butler (ed.), Annalium Hibernae Chronicon, Irish Archaeological Society. 1849, 35–7 in The Black Death, ed. Rosemary Horrox (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994), 84.

- D. Wilkins, Concilia Magnae Britanniae et Hiberniae, 4 vols, 1739, II, 745-6 in The Black Death, ed. Rosemary Horrox (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994), 271.

- See Rosemary Horrox, ‘Human Agency’, in The Black Death, ed. Rosemary Horrox (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994), 205–26.

- R. Hoeniger (ed.), Der Schwarze Tod, Berlin, 1882, appendix III, pp. 152–6 in The Black Death, ed. Rosemary Horrox (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994), 158–63.

- A. Chiappelli (ed.), ‘Gli Ordinamenti Sanitari del Comune di Pistoia contro la Pestilenza del 1348’, Archivio Storico Italiano, series 4, XX, 1887, 8–22 in The Black Death, ed. Rosemary Horrox (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1994), 194–203.

- David Wright. Richard Landes, April 2015, comment on Helen King, ‘Why I wasn’t excited about the medieval remedy that works against MRSA’, The Conversationalist (blog), 9 April 2015. Available online: https://theconversation.com/why-i-wasnt-excited-about-the-medieval-remedy-that-works-against-mrsa-39719#comment _641009, accessed 8 May 2018.

- ExpertExpat, 2017, comment on Erin Blakemore, ‘This Nasty Medieval Remedy Kills MRSA’, Smithsonian 21 March 2015. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/nasty-medieval-remedy-kills-mrsa-180954808/#comment-3287469822, accessed 8 May 2018.

- Cordel, 2017, comment on Erin Blakemore, ‘This Nasty Medieval Remedy Kills MRSA’, Smithsonian, 21 March 2015. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/nasty-medieval-remedy-kills-mrsa-180954808/#comment-3287469822, accessed 8 May 2018.

- Unthwarted, comment on Erin Blakemore, ‘This Nasty Medieval Remedy Kills MRSA’, Smithsonian 21 March 2015. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/nasty-medieval-remedy-kills-mrsa-180954808/#comment-3287469822, accessed 8 May 2018.

- Kathleen Marion, comment on Erin Blakemore, ‘This Nasty Medieval Remedy Kills MRSA’, Smithsonian21 March 2015. Available online: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/nasty-medieval-remedy-kills-mrsa-180954808/#comment-3287469822, accessed 8 May 2018.

- Clare Monagle and Louise D’Arcens, ‘“Medieval” Makes a Comeback in Modern Politics: What’s Going On?’, The Conversation, 22 September 2014. Available online: https://theconversation.com/me dieval-makes-a-comeback-in-modern-politics-whats-going-on-31780, accessed 8 May 2018.

- Louise D’Arcens, Comic Medievalism: Laughing at the Middle Ages (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2017), 12.

- Andrew B. R. Elliott, Medievalism, Politics and Mass Media: Appropriating the Middle Ages in the Twenty-First Century (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2017), 200–201.

- John T. R. Terry, ‘Why ISIS Isn’t Medieval’, Slate, 19 February 2015. Available online: http://www.slate.com/articles/news_and_politics/history/2015/02/isis_isn_t_medieval_its_revisionist_history_only_claims_to_be_rooted_in.html , accessed 14 August 2018.

- Elliott, Medievalism, Politics, 66.

- Chris Jones, ‘Is the Islamic State Medieval?’, The Research Headlines, 18 September 2014. Available online: https://researchtheheadlines.org/2014/09/18/is-islamic-state-medieval/ , accessed 16 June 2018.

- Susan Gonzalez, ‘Director Spike Lee Slams “Same Old” Black Stereotypes in Today’s Films’, Yale Bulletin & Calendar (Yale University), 2 March 2001. See also Matthew Hughey, ‘Cinethetic Racism: White Redemption and Black Stereotypes in “Magical Negro” Films’, Social Problems 25, no. 3 (August 2009): 543–77.

- See The Public Medievalist. Available online: https://www.publicmedievalist.com/race-racism-middle-ages-toc/ for an ongoing series on the topic of race and medievalism.

- Nir Shafir, ‘Why Fame Miniatures Depicting Islamic Science Are Everywhere’, Aeon,11 September 2018. Available online: https://aeon.co/essays/why-fake-miniatures-depicting-islamic-science-are-everywhere, accessed 1 October 2018.

- Ibid.

- John Ganim, Medievalism and Orientalism (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), 84.

- Ibid., 42.

- Ibid., 85.

- Jones, ‘Is the Islamic State Medieval?’.

- Paul Sturtevant, The Middle Ages in Popular Imagination: Memory, Film and Medievalism (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2018), 139.

- Jacques Le Goff, Time, Work, and Culture of the Middle Ages (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1980), ix.

Chapter 4 (58-73) from The Middle Ages in Modern Culture: History and Authenticity in Contemporary Medievalism, edited by Karl C. Alvestad and Robert Houghton (Bloomsbury Academic, 10.07.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.