He wished to throw the glory of the Marathon battle into the shade for his own rhetorical purposes.

By Dr. Andreas Markantonatos

Professor of Ancient History and Archaeology

University of the Peloponnese

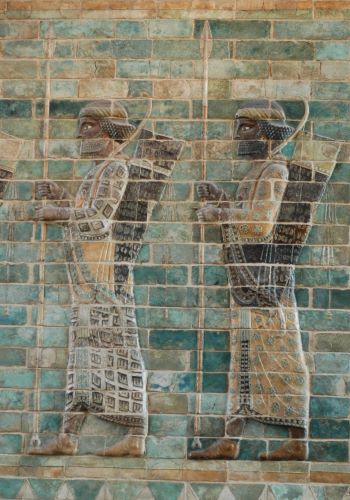

It is an undeniable fact that the battle of Marathon1 is a major landmark in Athenian history,2 a remarkable display of courage, military prowess, and strategic planning, recognized as a model for younger generations to emulate.3 It was therefore no surprise that this remarkable episode of the first phase of the Persian Wars rapidly came to be seen as the epitome of Athenian bravery, as well as a symbol and a prefiguration of Athenian hegemony, embodying the hopes and ambitions of the people of Athens. What is more, the then still fledgling radical democracy discovered in the land battle of Marathon a most popular morality tale, showing the Athenians fighting fearlessly for justice against impious oppressors. Democracy’s eager embrace of the Marathon triumph and, more widely, of the honourable campaigns of 490-78 BC is a clear indication of how the Athenian polis created and reinforced her reputation as a civilizing city always ready to wage the war of justice against hubris. It is a commonplace of current scholarship that the telling and retelling of the glorious history of the Persian Wars in song and story played a direct role in the gradual shaping of the Athenian image of Athens during the fifth and fourth centuries BC – that is, the progressive formation of an Athenian identity through the constant recital of great exemplary deeds illustrating the city’s unique moral sense in pursuing the justified claims of the weak, as well as in repelling the uncivilized forces of the East from Greece.4

There is, however, another underlying aspect to the inextricable connection between the Persian Wars and Athenian ideology that we need to address here. Not only did the victorious Marathon campaign, together with such milestones as the land battles of Thermopylae and Plataea and the sea battles of Salamis and Artemisium, end Persian efforts to conquer Greece, but it also staved off the threat to democracy posed by the dispossessed tyrant of Athens, Hippias, who had joined the Persian side in the hope of being restored to power. It is thus fair to say that the battle of Marathon marked a watershed in the Greco-Persian Wars, showing the Greeks that the Persian might is far from unbeatable, especially when matched against the vast superiority of the Greek hoplite army over the Persian infantry, and on a purely Athenian level strengthened the democratic regime by averting the social turmoil and the political chaos that a Persian-backed tyranny would otherwise have created.5 From this moment onwards the elimination of Persian influence over the Hellenic world became a rallying cry for Athenian democracy.

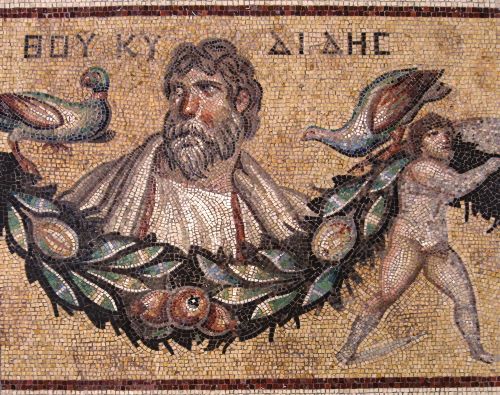

I shall discuss how Thucydides responds to the battle of Marathon, suggesting that he gives some broad hints that there is indeed an indissoluble link between the defeat of the Persians at Marathon and the Athenian constitution, though in Book 1 he appears to dismiss the battle of Marathon as not being part of the Persian Wars proper in an effort to emphasize the significance of the Peloponnesian War. This extraordinary event of the Persian Wars would have a special place in the context of Athenian democratic ideology as it took shape in fourth-century oratory, especially in funeral speeches in honour of the war dead. The eulogy of Marathon as a topos of Athenian bravery is one of the standard characteristics of fourth-century encomiastic rhetoric: the popular idea of a purely Athenian victory over the wicked Asiatic invaders, together with the notion of a distinctly democratic accomplishment of great moment setting the pattern for other Greeks to follow, takes centre stage in epideictic speeches.6 But it is my basic contention here that, while the ideology can be seen at its most explicit in the fourth century, and despite the almost total loss of fifth-century oratory, certain allusions to Marathon in Thucydides allow us to see the presence of this ideology already in the fifth century. Despite his agonistic dismissal of Marathon and ta Mêdika, Thucydides indirectly acknowledges the significance of the battle. Much as he wishes to throw the glory of the Marathon battle into the shade for his own rhetorical purposes, as well as making light of other decisive Greek victories against powerful foreign invaders, he cannot suppress its vital role in the formation of Athenian self-identity. Without wishing to stretch a point, I shall argue that, taken together, his fleeting references to the battle of Marathon (no more than seven in total) have all the essential ingredients of an Athenian tale of democratic goals achieved in the face of extreme danger. Apparently, by the time of Thucydides, the triumphant Marathon campaign had come to be seen as both a truly memorable occasion of endurance and resilience demonstrated by the Athenian fighting forces on the battlefield, and a further proof of democracy’s ability to design military and political strategies to defend the rights of the Athenian citizens against dynastic aggressors.

In the Archaeology, Thucydides alludes to those celebrated national champions, the Marathon-fighters (Μαραθωνομάχοι) familiar to us from comedy, who came to be seen as a powerful symbol of the Golden Age of Athens, thereby offering a rare insight into Athenian social mores and expectations, as well as hinting at the intimate relationship between the Marathon triumph and Athenian self-perception. In fact, before referring directly to the battle of Marathon in Book 1, he recounts how the Athenians, first among all Greeks, adopted a more comfortable way of life having abandoned the rather uncivilized fashion of wearing arms (1.6.3-4):

The Athenians were the first to lay aside their weapons, and to adopt an easier and more luxurious mode of life; indeed, it is only lately that their rich old men left off the luxury of wearing undergarments of linen, and fastening a knot of their hair with a tie of golden grasshoppers, a fashion which spread to their Ionian kindred, and long prevailed among the old men there. On the contrary a modest style of dressing, more in conformity with modern ideas, was first adopted by the Lacedaemonians, the rich doing their best to assimilate their way of life to that of the common people.

Contrary to widespread practice, the aristocratic older men of Athens, typically identified with the brave men of the days of Marathon, those Μαραθωνομάχοι, wore linen tunics and fastened a knot of their hair with golden grasshopper brooches.7 Nevertheless, fashions and trends come and go as much as societies change. In the days of the empire, the wealthy elders assumed a less flamboyant style of dressing more along the lines of the stricter Spartan dress code. In his Knights (1321-34) and Clouds (984-86), Aristophanes provides abundant evidence of the close relation between the traditional dressing code and the Marathon-fighters, in contexts of praise for the old system of education which bred strong, honest, and righteous citizens.8 In particular, in Knights 1329-34 the Sausage-seller welcomes the magically rejuvenated Demos, and the Chorus of Athenian cavalrymen echo his enthusiasm, invoking the glory of Marathon as a symbol of collective moral responsibility:

Chorus-leader: Athens the gleaming, the violet-crowned, the all-envied, show us the monarch of Greece and of this land.

Sausage-seller: Behold the man, wearing a golden cicada, resplendent in antique costume, smelling not of mussel-shells but of peace-libations, and anointed with myrrh.

Chorus-leader: All hail, sovereign of the Greeks; we rejoice with you; for your bliss is worthy of the city and of the trophy at Marathon.

trans. A. H. Sommerstein

The context makes explicit that the Chorus-leader sees in the purified Demos a true representative of the old spirit of Marathon; the splendid attire, together with the golden cicada worn as a hair ornament, is a distinct sign of those days of yore, when ancestral law reigned supreme and the city of Athens held sway over much of Greece, which is seen here as no more than her due in view of her instrumental role in bringing about an end to the bitter conflict between Greeks and barbarians. The linkage between the time-honoured lustrous dress and the political heritage of the Marathon triumph is further reinforced by the profuse praise for Aristeides and Miltiades, the victor of Marathon (l. 1325).9 We can therefore safely draw the conclusion that not unlike Thucydides Aristophanes is sensible of the fact that the generation which emerged triumphant from the Marathon battle not only set an example to future generations of Athenians, but earned Athens the right to rule. In fact, Thucydides stresses the importance of a more relaxed way of living, pointing out that with the new dress style the rich Athenian elders made a complete break with unsophisticated conventions and piratical methods. It could be argued that he presents this comfortable lifestyle in the best possible light, regarding this sea-change in societal attitudes as bringing progress and civilization in a world plagued by incessant wars and conflicts. Similarly, Aristophanes wishes to bring the simplicities of an old way of life to bear upon reshaping the fiendishly complex present. In a time of ferocious political tensions in Athens his plays argue of the fact that the gentility and refinement of the Marathon-fighters would never have allowed the city to descend into a terrifying spiral of violence.

The oblique references to the glory days of the Athenian past are soon to be followed by express mentions of the Marathon battle. This time, however, the splendour surrounding the Persian Wars provides a mere foil for the fierce intensity of the intra-Hellenic violence of the military confrontation between Athens and Sparta. More specifically, in the first Book of his History (1.23.1), Thucydides argues that the Peloponnesian War far surpassed all other armed conflicts in destructive power:

The Persian War, the greatest achievement of past times, yet found a speedy decision in two actions by sea and two by land. The Peloponnesian War was prolonged to an immense length, and long as it was, it was short without parallel for the misfortunes that it brought upon Hellas.

To the uninitiated it certainly comes as a surprise to hear that the two Persian invasions of Greece were decided by merely four battles; and it is even more surprising to realize that in his account of early times Thucydides excludes the battle of Marathon from the list of decisive collisions between Greeks and barbarians as an isolated incident, giving instead more focus to the second phase of the Greco-Persian Wars, when the son of Darius and new ruler of Persia, Xerxes, led his innumerable host into Greece ten years after the humiliating defeat of the Persian army at the bay of Marathon. We have already noted that Thucydides makes much of the Peloponnesian War to the point of arguing emphatically, in what looks like a pointed response to Herodotus (7.20-21), that what came before in Greek history, even if that was the legendary Persian Wars, bears no comparison to the far more ferocious and violent conflict between Athens and Sparta.10 There is a difference of opinion as to the validity of his conclusion; it is nonetheless important not to overlook that his approach to human history can be at times far too realistic for those romantic readers who are highly susceptible to ‘David against Goliath’ tales of glory. A. W. Gomme is right to suggest that ‘Thucydides is concerned with war as a κίνησις, a destructive agency, and in that sense… for Greece the Persian war ended with the expulsion of the invaders’,11 whereas, we may add, the repercussions of the internecine struggles for power and dominance between the Athenians and the Spartans continued to reverberate through the Greek world for years on end.

Although Thucydides appears to be dismissive of the Marathon campaign in his brief narrative of early Greek history, he nonetheless refers to it directly before he makes, as noted above, what some critics have felt as too sweeping a statement about the priority of the Peloponnesian War over other Greek military triumphs.12 It is particularly interesting to note that here the Marathon battle is closely linked with the deposition of the tyrants in Athens and the rest of Greece with the help of the Lacedaemonians. According to Thucydides (1.18.1-2), soon after the tyrants’ removal from power, the Athenians confronted the Persians at Marathon:

Not many years after the deposition of the tyrants, the battle of Marathon was fought between the Medes and the Athenians. Ten years afterwards the barbarian returned with the armada for the subjugation of Hellas.

More importantly, Thucydides readily acknowledges a strong connection between the defeat of the Persians at the bay of Marathon and the Athenian army. It is at this juncture that he stresses a favourite narrative theme – the battle of Marathon as a purely Athenian victory. The Athenian infantry repulsed the Persian attack in the wake of major political reforms in the Greek city-states. Though Thucydides is not explicit about the democratic dimension of the Athenian accomplishment at Marathon, he implicitly alludes to it by emphasizing the benefits accruing from the deposition of tyrannical rulers in Greece and elsewhere.13 He praises Sparta for enjoying unbroken freedom from tyranny, having obtained good laws at a very early period. It may be rightly said that at Marathon Athens herself, unburdened by the onus of old dynastic families, fought the good fight of freedom from both Persian despotism and tyrannical rule.

The collective Athenian pride in the battle of Marathon is also evidenced elsewhere in Thucydides. In the first book of his History there is a direct reference to the instrumental role of Athens in the success of the Marathon campaign. This time it is not the historian who makes mention of the Marathon triumph in connection with the city of Athens; the Athenians themselves take pride in their victory over the Persian invaders at the bay of Marathon (1.73.4), warning against attacking courageous and determined opponents who proved themselves capable of adjusting to the gravest emergency:

However, the story shall be told not so much to deprecate hostility as to testify against, and to show, if you are so ill-advised as to enter into a struggle with Athens, what sort of an antagonist she is likely to prove. We assert that at Marathon we were at the front, and faced the barbarian single-handed. That when he came the second time, unable to cope with him by land we went on board our ships with all our people, and joined in the action at Salamis. This prevented his taking the Peloponnesian states in detail, and ravaging them with his fleet; when the multitude of his vessels would have made any combination for self-defence impossible.

The occasion is an extremely important one: Athenian envoys are in Sparta making every effort to persuade the Lacedaemonians to resist the clamorous voices of their allies demanding the destruction of Athens. In their passionate speech they invoke the Persian Wars, placing special emphasis on their share in the solid results of this brutal clash between Greeks and barbarians. Naturally, the battle of Marathon takes pride of place in their short narrative, which serves, among other things, as a further proof of the emergence of the new genre of encomiastic oratory in the fifth century BC.14 The Athenian ambassadors assert that ‘Μαραθῶνί τε μόνοι προκινδυνεῦσαι τῷ βαρβάρῳ’ (‘at Marathon we were at the front, and faced the barbarian single-handed’), failing to notice the active part played by the Plataeans in the fighting.15 Aside from the slight exaggeration, probably called for by the high urgency of the situation, the Marathon triumph is credited to the Athenians alone; and, as a matter of fact, in the Plataean Debate in Book 3 the Plataeans themselves are at pains to under-emphasize their participation in the Marathon campaign and draw attention instead to the fact that although they are an inland people they became inextricably involved in the sea battle at Artemisium. Simon Hornblower is justified in thinking that in contrast to the battle of Plataea the Marathon campaign was indissolubly linked with Athens, as well as rightly suggesting that ‘the Athenian associations of Artemisium were perhaps less inescapable’ for the Spartans to take offence if the Plataeans appeal to a sea battle in which, as is widely known, the 127 Athenian ships were partly manned by Plataean fighters despite their ignorance of nautical matters (Herodotus 8.1.1).16

The theme of Marathon as a military triumph of democratic Athens is once more evoked in the context of the Funeral Oration of Pericles in Book 2. Before the commencement of the speech, Thucydides notes that the Athenians bury their dead in the state tomb except for those who fell at Marathon. The reference here is particularly striking, since Pericles is about to pass over the deeds of the ancestors in his Funeral Oration (2.34.4):

The dead are laid in the public sepulchre in the most beautiful suburb of the city, in which those who fall in war are always buried; with the exception of those slain at Marathon, who for their singular and extraordinary valour were interred on the spot where they fell.

Given that the men who fell at Salamis and Plataea were also given burial where they were slain, the question of Thucydides’ reference to the Marathon dead is still hotly debated by scholars.17 Nevertheless, we do not have to assume that Thucydides is ignorant of the burial sites of those who fell at Salamis and Plataea.18 The Marathon tomb had already become a powerful symbol for Athens and especially for Athenian democracy, bearing eloquent witness to what might be achieved through unity and self-belief. In that September of 490 BC, the victory at Marathon endowed the young Athenian democracy with a faith in her destiny that was to endure for almost a century – this is a generally acknowledged fact, and Thucydides invokes a powerful symbol of Athenian courage and determination at a time of intense national alert.

It is therefore only natural that in Book 6, in what is his last express mention of Marathon (6.59.4), Thucydides once more relates the battle to the fall of tyranny in Athens, turning full circle to the story of the expulsion of the Pisistratids from Athens (1.18.1). Moreover, it is significant that the story of Hippias is re-narrated in the context of the sacrilege of the Eleusinian Mysteries and the mutilation of the Herms – a very turbulent period, that is, during which political rivalries led to renewed factional conflict within the Athenian democracy. In actual fact, according to Thucydides’ account, after the assassination of Hipparchus by Harmodius and Aristogeiton, Hippias reigned for three more years, and then in 510 BC was deposed by the Lacedaemonians and the banished Alcmaeonidae and went to King Darius, from whose court he headed out twenty years later and came with the Persians to Marathon in the autumn of 490 BC.19

To sum up then. Unlike the fourth-century orators who were lavish in their praise for Marathon, Thucydides is relatively silent about the glory of the Marathon campaign. But in his restrained way he is nonetheless generous in crediting the victory solely to the Athenian spear, never failing to allude to what was truly at stake in that battle: the freedom of Greece from Persian autocracy and the freedom of Athens from tyrannical oppression.

Endnotes

- I would like to thank most warmly the participants of the Marathon conference for their constructive criticism and in particular Professors Georgia Xanthaki-Karamanou and Christopher Carey for their advice and encouragement. It should be noted that the text of Thucydides used in this paper is the OCT (H. S. Jones and J. E. Powell, Thucydidis Historiae, 2 vols [Oxford 1942 with numerous reprints]). Richard Crawley’s translation of Thucydides is reproduced throughout this essay (The complete writings of Thucydides: the Peloponnesian War, ed. J. H. Finley, Jr. [New York 1951]).

- Given the worldwide celebration of the 2,500th anniversary of the battle of Marathon, the relevant bibliography has grown considerably. In Greece alone, there have been no fewer than five specialized publications commemorating the land battle at Marathon: G. Steinhauer, Ο Μαραθών και το Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο (Athens 2009) (for a useful abridged version, see G. Steinhauer, Μαραθώνας: Η Μάχη πουσ ημάδ εψετηνισ τορία [Athens 2010]); K. Bourazelis and K. Meidani, ed., Μαραθών: Η Μάχη και οαρχαί οςδήμος (Athens 2010); F. Frangos, ΧωρίςΙπ πείς: ημάχητου Μαραθώνα (490 π.Χ.) 2.500 χρόνια (Athens 2010); K. Meidani, V. Lazou, and K. Kartalis, ed., Ημάχη του Μαραθώνα (Athens 2010); S. Merkouris, ed., ∆ημοκ ρατία και ημάχη του Μαρα θώνα. Ζάππειον Μέγαρον, 23-31 Οκτωβρίου 2010 (Athens 2010). For detailed discussions of the battle and related issues, see principally J. F. Lazenby, The mountains look at Marathon: the defence of Greece 490-479 BC (Warminster 1993); A. Lloyd, Marathon: the crucial battle that created western democracy (London 2005); R. A. Billows, Marathon: the battle that changed western civilization (New York 2010); P. Krentz, The battle of Marathon (New Haven 2010). Cf. also, e.g., N. G. L. Hammond, ‘The campaign and battle of Marathon’, JHS 88 (1968) 13-57; N. G. L. Hammond, A history of Greece to 322 B.C. (Oxford 1986) 212-18; R. Osborne, Greece in the making, 1200-479 BC (London and New York 1996) 328-33.

- For the role of Marathon as a paradigm in subsequent Athenian literature, see the chapters of Karamanou, Xanthaki-Karamanou, Volonaki, Papododima, and Carey in this volume.

- On Athenian imperial ideology and Athenian self-presentation, see N. Loraux, The invention of Athens: the funeral oration in the classical city, trans. A. Sheridan (Cambridge, MA and London 1986) esp. 132-71; A. L. Boegehold and A. C. Scafuro, ed., Athenian identity and civic ideology (Baltimore and London 1994); S. Mills, Theseus, tragedy and the Athenian empire (Oxford 1997) 43-86. On the impact of the Persian Wars on fifth-century Athens and beyond, see recently E. Bridges, E. Hall, and P. J. Rhodes, ed., Cultural responses to the Persian wars: antiquity to the third millennium (Oxford 2007).

- This does not at all mean that the Marathon triumph caused the slow demise of factional politics in Athens, as can be seen from the sad story of Miltiades, the hero par excellence of the Marathon campaign. Not long after the Persian defeat at the bay of Marathon, Miltiades evoked a hostile response from his political opponents for his audacious expeditionary plan to lay siege to the city of Paros. In fact, all his efforts to capture Paros ended in failure, and his enemies made sure that he died in disgrace upon his return to Athens (Hdt. 6.132-6). See also the sobering comments in Osborne, Greece in the making (n. 2 above) 330-32.

- See principally Loraux, The invention of Athens (n. 4 above) 155-71, with the relevant ancient sources. On rhetoric and Athenian democracy, see H. Yunis, Taming democracy: models of political rhetoric in classical Athens (Ithaca, NY 1996); V. Wohl, ‘Rhetoric of the Athenian citizen’, in E. Gunderson, ed., The Cambridge companion to ancient rhetoric (Cambridge 2009) 162-77.

- See also A. W. Gomme, A historical commentary on Thucydides, volume I. Introduction and commentary on Book I (Oxford 1945) 100-03; S. Hornblower, A commentary on Thucydides, Volume I. Books I-III (Oxford 1991) 25-27.

- See A. H. Sommerstein, The comedies of Aristophanes, vol. 2: Knights (Warminster 1997) 1325 and 1331, and The comedies of Aristophanes, vol. 3: Clouds (Oxford 2007) 984, with relevant bibliography. Cf. also D. E. O’Regan, Rhetoric, comedy, and the violence of language in Aristophanes’ Clouds (New York and Oxford 1992) esp. 89-105; A. M. Bowie, Aristophanes: myth, ritual and comedy (Cambridge 1993) 58-59, 201; D. M. MacDowell, Aristophanes and Athens: an introduction to the plays (Oxford 1995) 80-149.

- See also Sommerstein, Knights (n. 8 above)1325.

- Perhaps the irreconcilable accounts of an earthquake at Delos in Herodotus (6.98.1-3) and Thucydides (2.8.3) are a further proof of the latter’s tendency to play down the Persian Wars and especially the Marathon battle. According to Thucydides, the island of Delos was shaken by an earthquake for the first time in the living memory of the Greeks a little before the Peloponnesian War, whereas Herodotus says that before the battle of Marathon Delos experienced a seismic shock for the first and last time ever, adding significantly that this earthquake was a divine warning for the Greeks signalling the misfortunes that were in store for them in the coming years. Cf. also A. W. Gomme, A historical commentary on Thucydides, the ten years’ war, volume II. Books II-III (Oxford 1956) ad loc.; Hornblower, A commentary on Thucydides, volume I (n. 7 above) 245-46.

- Gomme, A historical commentary on Thucydides, volume I (n. 7 above) 151.

- See Hornblower, A commentary on Thucydides, volume I (n. 7 above) 62-64, with further bibliography.

- In this Thucydides agrees with Herodotus’ judgement on the importance to Athens of the removal of the tyrants (5.78).

- On epideictic oratory, see recently J. Hesk, ‘Types of oratory’, in The Cambridge companion to ancient rhetoric, ed. Gunderson (n. 6 above) 156-61.

- See also W. C. West III, ‘Saviors of Greece’, GRBS 11 (1970) 271-82; K. R. Walters, ‘“We fought alone at Marathon”: historical falsification in the Attic funeral oration’, RhM 124 (1981) 204-11.

- Hornblower, A commentary on Thucydides, volume I (n. 7 above) 448.

- See, e.g., Gomme, A historical commentary on Thucydides, volume II (n. 10 above) 34.1; Hornblower, A commentary on Thucydides, volume I (n. 7 above) 294.

- Cf. also M. Ostwald, Nomos and the beginnings of the Athenian democracy (Oxford 1969) 175.

- See also A. W. Gomme, A. Andrewes, and K. J. Dover, A historical commentary on Thucydides, volume IV. Books V 25-VIII (Oxford 1970) ad loc.

Contribution (69-77) from Marathon – 2,500 Years, edited by Christopher Carey and Michael Edwards (University of London Press, 12.02.2013), Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.