Interpretations that suggest Ragnarøk motifs in Viking age iconography.

By Dr. Anders Hultgård

Professor Emeritus and Former Chair of Religious History

Uppsala University

Introduction

Despite its character of being a well-known and still used concept in Scandinavian cultures, the idea of Ragnarøk is based on a limited body of texts preserved on Iceland. No wonder, then, that iconographical evidence has been sought, in order to supplement the meagre textual sources. To take a few examples. In a recent book on Anglo-Saxon stone sculpture, the author, having mentioned the Gosforth Cross, states that “Sculptural evidence from the Isle of Man provides further proof that the events of Ragnarøk were known in the British Isles”.1 The presence of Ragnarøk motifs on Danish and Swedish rune stones suggested by runologists such as Erik Moltke and Sven B.F. Jansson serves to show that the Ragnarøk myth was told all over Scandinavia. The degree of certainty with which scholars present their interpretations varies on a scale from plain statement of facts to a cautious “perhaps”. Often one gets the impression that scholars cannot resist the temptation of proposing a Ragnarøk interpretation, but that the insertion of a simple question mark saves them from reproaches for being too speculative. In addition, we may point to the circumstance that interpretations of pictorial scenes tend to be repeated by others without independent reflection.

The purpose of my contribution is to make a critical assessment of the interpretations that suggest Ragnarøk motifs in Viking age iconography. Space does not allow me to review all the material at our disposal. Instead, I will pick out some of the more important monuments and objects that have been associated with the Ragnarøk.2 For a fuller review of such iconographic material, I refer to my book on the Ragnarøk myth.3

The Gosforth Cross

Let us begin with the Gosforth Cross. It has been dated to the first half of the 10th century and is still standing on its original place in St Mary’s churchyard at Gosforth in northern England. The four and a half metre-high stone pillar has figurative motifs on all four sides, but the decorative aspect dominates: long bands of elements, interlaced or linked together, that end up in yawning animal heads (Fig. 1). The figurative scenes are generally considered to be a mixture of Christian and pagan elements. The first person to interpret the carvings with reference to Old Norse mythology seems to have been the Dane George Stephens at the beginning of the 1880s.4 He was soon followed by the English antiquarian Charles Arundel Parker in his book on the Gosforth Crosses.5 Subsequently, a number of scholars have followed this line of interpretation, among them Axel Olrik,6 Knut Berg;7 Richard Bailey;8 Sigmund Oehrl9 and Lilla Kopár.10

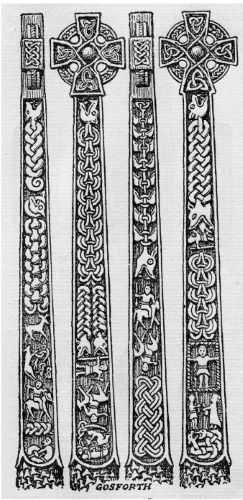

I will briefly summarize how the picture scenes of the cross are usually explained. Starting at the bottom of the east face, we are undoubtedly confronted with a crucifixion scene (Fig. 2). Longinus, the Roman soldier, piercing the side of Jesus with his lance; the blood pouring forth; the woman may represent Mary, mother of Jesus, Mary of Magdala, or Ecclesia, the Church personified, who approaches with her bottle-like bowl to receive Christ’s blood. Another interpretation suggests that the woman has been substituted for Stephaton, the sponge-bearer in the Christian standard scenes of crucifixion.11 She offers a mead cup or a drinking horn to Jesus as a symbol of death. This would suggest an influence of Germanic myth. The crucifixion scene together with the monument’s shape and original location makes it clear that the frame of interpretation must be Christian. However, the rest of the figurative scenes seem to be more difficult to place in that context. At this point, Old Norse mythology intervenes and rescues scholars from their bewildering situation.

arther up, on the east face, a man is seen leaning on a staff (less probably a spear; Fig 3); his left arm is raised upwards and his hand touches the upper jaw of the beast. The man’s one leg appears as if trapped in the tongue of the beast which is cleft in the way typical of serpents; the foot is hidden behind the inferior jaw. The male figure is generally interpreted in accordance with the description of the Prose Edda as being the god Víðarr who is tearing the jaws of Fenrir to avenge his father’s death.12

At first glance, the interpretation seems convincing, but in my view it is not. The details of the picture do not tally with the descriptions of the Poetic Edda which are roughly contemporaneous with the date of the Gosforth Cross. According to the Vǫluspá, Víðarr thrusts his sword into the heart of the monster and in the version of the Vafþrúðnismál he splits the jaws of Fenrir (with his sword). The German philologist Richard Reitzenstein suggested instead that the male figure represents Christ who is opening the jaws of Satan or Death in order to liberate the souls of the just from their captivity in hell. The myth of Christ’s descensus ad inferos was well known in Christian antiquity, and its popularity increased considerably in the Middle Ages which is shown by the many versions in the vernacular. Reitzenstein’s interpretation is not without problems either, however. The way in which Christ confronts the Devil, as described in the main textual sources, does not quite agree with the pictorial representation of the Gosforth Cross. According to the Gospel of Bartholomew, Jesus seized Beliar (= the Devil), flogged him and bound him in fetters that could not be broken. The Gospel of Nicodemus, states that Christ, the King of Glory, trod Death beneath his feet, seized Satan and delivered him into the power of Hades. The Old Norse version from the twelfth century, the Niðrstigningar saga, may be closer to the imagery of the Gosforth Cross in telling that Satan transformed himself into an enormous serpent or dragon. Having learnt that Jesus was dying on the cross (var þá í andláti), he went to Jerusalem in order to capture the soul of Jesus. But Jesus had prepared a trap with a hook hidden in the bait. When Satan attempted to devour Jesus, he became stuck on the divine hook and the cross fell on him from above: þá beit ǫngullinn guðomsins hann ok krossmarkit fell á hann ofan. Then Jesus approached, bound the Devil and ordered his angels to guard him (varðveita hann).13

The west face shows a similar figure to the one on the east face (Fig. 4). A man is standing in front of two gaping beasts. Unlike the animal head of the east side, these are depicted with teeth similar to those of a wolf. The man holds a staff in one hand and in the other an object that looks like a drinking horn. The motif is considered to represent the god Heimdall at the moment when he is to give a great blast on the Gjallarhorn to warn the gods of their approaching enemies; he tries to keep them away with his “spear”.14 However, the figure may as well depict Christ, although the horn appears to be somewhat odd in the context. Below, we see a rider set upside-down holding a spear (note the pointed form of the end unlike the staff).

At the bottom, there is a scene showing a male figure with bound hands and feet; something like a snare is hanging around the neck (Fig. 5). The man seems to have his hair arranged in a long braid; in front of him is another figure, also with a braid, usually interpreted as a woman, in a kneeling position and holding a sickle-shaped object. The head of a snake can be distinguished above the figure to the left. A band with a knot seems to protrude from the band along the edges; the two figures are, as it were, encircled. Almost all commentators agree on the interpretation that the motif represents the punishment of Loki bound in the cave and also showing his wife Sigyn with her bowl. Even Reitzenstein had to admit the Scandinavian origin of the scene, but emphasized that it is only a symbol or typos for the Devil being fettered in the body of Hades. However, uncertainty about the Loki-Sigyn interpretation was expressed by Jan de Vries,15 and I am not quite convinced that the scene is inspired by Norse mythology.

The figurative motifs of the north and south faces are more difficult to interpret in a clear-cut manner (see Fig 1). Some scholars find Christian symbolism,16 others suggest figures such as Týr, the dog Garm, the stag Eikþyrnir and the Fenris Wolf.17

To conclude, doubt can be raised regarding the iconographical interpretations relying on Scandinavian mythology, but explaining convincingly all the pictures in the context of Christian ideas is not without its problems either. The only scene that presents an undisputed picture is the crucifixion scene on the east face. The proponents of the “Scandinavian mythology” interpretation explain the presence of the Ragnarøk motifs by the fact that they serve as symbols to communicate important Christian teachings. But if so, why were they not pictured so as to better fit in with what is told in Old Norse mythology, and the question still remains – how could the viewers know that the figurative scenes should be interpreted symbolically?

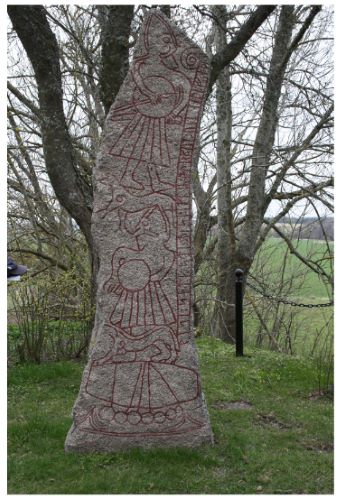

The Tullstorp Stone

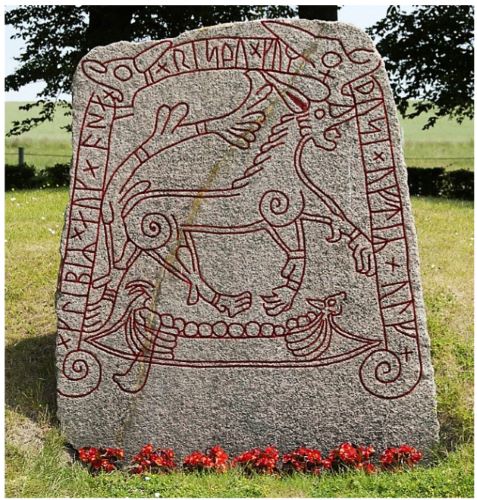

Several pictures on rune stones have been considered to allude to the Ragnarøk drama. Among them is this large beast of the Tullstorp Stone (DR 271; Fig. 6), usually interpreted as the wolf Fenrir running to attack the gods.18 The shape of this four-legged animal shows it to be part of a particular type of animal representation known from many other stones and objects, in the first place the Jelling Stone. Examples from Sweden are the Stora Ek Stone (Vg 4) and the Norra Åsarp Stone (Vg 181) both in the province of Västergötland. I call this type of animal the “the big, gaping beast” and have described its characteristics elsewhere.19

The iconography of this animal type has also been studied by Sigmund Oehrl20 who terms it “das grosse Tier”. As to the image on the Tullstorp Stone, there are two points to be made. First i should not be interpreted in isolation from other representations of “the big, gaping beast” and secondly, I find it rather improbable that the patron or the artist of the monument had intended to depict the wolf Fenrir. This does not exclude the possibility that onlookers of the eleventh century were able to discover an allusion to this Ragnarøk monster animal.

The Ledberg Stone

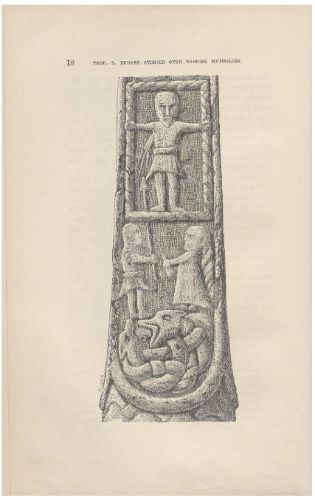

The stones belonging to the Tullstorp group show only animal representations. Other stones that have been associated with Ragnarøk motifs display both animal and human figures. The most well-known example is the Ledberg Stone (Ög 181) which has images engraved on three sides. The front side (A) shows two warriors with round shields (Fig. 7). The warrior above holds an axe in one hand and in the other an object that looks like a sword. The body position of the warrior below is different; his right arm is pointing downwards and he holds something that could be a spear. Between the two warriors an animal, dog or wolf, is seen running. Close to the warrior below the contours of a second animal can be distinguished in a position as if attempting a leap. The lowest part shows a ship with mast and shields.

The back (B) presents another scene (Fig. 8) Again we meet two warriors dressed in the same way as those on the front but lacking weapons. The position of their bodies seems to indicate defeat and death. An animal, dog or wolf, is seen biting the foot of the warrior above, whereas the warrior below stretches his arms for-ward; his legs are missing.

One of the edge sides (C) shows a cross, drawn like a tree with its roots (Fig. 9).The inscription says that a man, Bisi, and a woman, Gunna, had the stone set up in memory of his (or their) father Thorgaut, and the text ends with the formula þistill/mistill/kistill which probably was intended to protect the monument or perhaps serve as a sort of password formula for the dead person on their way to the other world. The formula most probably had a ritual background and might have been used in private or public worship.

The iconography of the stone, in particular side B, has been linked to the Ragnarøk myth by several commentators, who see in it Óðinn’s confrontation with the wolf Fenrir.21 Reference is thereby made to a similar pictorial scene on the Thorvald Cross from Kirk Andreas on the Isle of Man.

In my view, we should keep the two sides (A and B) together when seeking to understand the iconography of the stone. One interpretation could be that the four warrior figures represent one and the same person shown at different moments of a struggle against one and the same animal. Above, on the front (A) we see the warrior at full strength with battle-axe and shield. The wolf is moving around him. In the next scene, the beast prepares to attack and the warrior now appears less forceful and even indecisive. On the back (B) the wolf has seized the foot of the warrior who seeks to escape, having lost his weapons. The final scene (below, side B) shows the defeated warrior sinking to the ground. But who is the warrior and who the wolf?

Erik Brate, the editor of Östergötlands runinskrifter, suggested that the four warrior figures depicted Thorgaut himself at different moments of the combat alluded to in the final part of the inscription, which Brate read as “he fell among the men of Tröndelag”. But this reading is now abandoned for the formula þistill, mistill, kistill. The animals, Brate thought, only had an ornamental purpose. A more likely view is that the figurative scenes are inspired by mythic tradition or some heroic legend. If one prefers the former alternative, all four warrior pictures would then show Óðinn fighting the wolf Fenrir. However, in this case the iconography is not in accordance with the statement in all the textual sources that the wolf will swallow (gleypir) the god entirely. Perhaps there is an allusion to some heroic tradition, like the allusion in one of the stanzas of the Ǫrvar Odds saga. Here a seeress predicts that a serpent shall bite the foot of the hero: naðr mun þik hǫggva neðan á fǿti. On the Ledberg Stone we find a wolf instead, but otherwise the parallel is striking. The pictorial configuration of a wolf or serpent biting a man’s foot could also be another way of stating a warrior’s death in combat.22

The family that had the Ledberg Stone erected lived at a period of religious change when Christianity had penetrated into southern Sweden. The cross on the edge (C; Fig. 9) is evidence, but the inherited faith was still alive and could inspire the choice of pictorial elements and formulae, as well as the adoption of pagan ideas that in their basic sense did not oppose Christian teachings. Such an idea was the final battle at Ragnarøk, the confrontation of Good and Evil. The iconography of the Ledberg Stone could in fact have to do with that myth. After his death, Thorgaut might have hoped to join the host of the einherjar and to fight against the powers of evil when the time came.

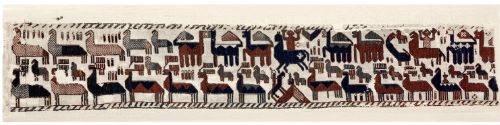

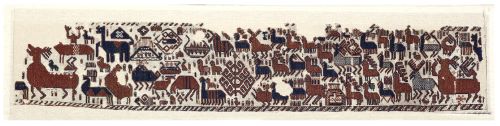

The Wall-Hangings of Överhogdal

The wall-hangings of Överhogdal consist of five pieces or weaves that were later sewn together to form a cover (Fig. 10, 11 and 12). The radio carbon dating (900‒1100) brings us back to the late Viking period which sets the frame of interpretation. The textiles have in all probability a local origin somewhere in the region from Tröndelag in the west over Jämtland to Hälsingland in the east. Some of them (Ia, Ib and III) would have decorated the walls of a chieftain’s hall or a wealthy farmer’s house; for weave II which has the most explicit Christian elements its original place in an early stave church seems likely. Weave Ia contains a runic inscription that should be read upside down. It was interpreted as guðbȳby Jöran Sahlgren.23

Here is not the place to make a detailed description of the wall-hangings and I pass directly to the discussion of their interpretation. Two studies have to be commented upon in the first place, one by Ruth Horneij24 and the other by Sture Wikman.25 Taking weave II (Fig. 10) as a point of departure, Horneij explains the pictorial contents as being derived from medieval illuminated manuscripts of the biblical Book of Revelation. For instance, the tree in the middle and the small animal below could represent the Tree of life and the Lamb, i.e. Christ (Rev. 22,1–2); the pictures of this motif in the Trier Apocalypse and on the so-called “Marcus Throne” in Venice in fact provide good parallels. The building to the far left is tentatively explained by Horneij as God’s temple in heaven; in the chancel we see Christ holding two book scrolls and the figures in the nave represent the seven apocalyptic angels, following Revelation Chapters 8 to 10.

Coming to pieces Ia and Ib (Fig. 11 and 12), Horneij has to have recourse to Old Norse mythology for her interpretation, although she thinks the overall message is still Christian. The tree with a bird on the top and another bird at the base depicts Yggdrasill at the beginning of Ragnarøk, the birds also alluding to the crowing cocks of the Vǫluspá. Some of the animal figures could, according to Horneij, be interpreted as animals taking part in the last battle at Ragnarøk. The beast with a wide-open mouth above the tree is the wolf Fenrir and the ship would then be Naglfar.

The eight-legged animal also appearing twice would be Óðinn’s horse Sleipnir which is taking part in the last battle together with the horse of St. Michael shown to the left. The blue animal below the runes would be the dog Garm and the large red animal looking backwards is probably meant to represent a reptile and could thus picture the Midgard serpent. For the figure inside the hexagonal construction, Horneij proposes three different interpretations 1) the bound Loki (but without Sigyn), 2) Gunnar in the snake pit and 3) the fettered Devil.

The building above the runes is explained as the New Jerusalem coming down from heaven and the figures inside would then represent redeemed souls. To support her interpretation, Horneij refers to the runes read as guðbȳ which would mean ‘God’s abode’. Further figurative elements of piece Ia could also be seen in a Christian eschatological context and Horneij concludes that weave Ia is an early Christian apocalyptic wall-hanging in part inspired by the Ragnarøk myth.

The animal with big hooves or paws could be another representation of the wolf Fenrir and the small human figure on the back who appears to stick something into the mouth of the beast would represent the god Víðarr fighting Fenrir. In my opinion, it is highly improbable that Víðarr performing the most heroic act of Ragnarøk should have been represented by such a tiny figure whose weapon cannot clearly be distinguished. Moreover, we can-not be sure of the narrative connection between the beast and the human figure. In addition, an unprejudiced interpretation could see the ears where Horneij sees the mouth.

Although having a less varied pictorial content, Horneij finds it easier to establish the Christian character of piece Ib. She points especially to the rider figures that she believes represent Christ. To the right, he raises his hands triumphantly after having defeated the dragon. The second picture in the middle shows Christ mounted on an ass rather than on a horse, thus recalling the prophecy of Zechariah Chapter 9. And the third rider picture would represent Christ when he returns as the Messiah.

The scene in the middle below shows a man with an axe riding up a triangular construction upon which a small human figure is seen sitting or lying on a throne or a bed. The motif which is unique has given rise to rather imaginative explanations: a missionary riding up to the top of a hill to smash an enthroned pagan idol,26 or Sigurdr Fáfnisbani riding up the mountainside to waken the sleeping valkyrie Sigrdrifa.27 Piece III should be explained, according to Horneij, by Christian legend about the virgin Mary and the infancy history of Jesus.

The study of Horneij merits recognition because she tries to interpret wall-hangings II, Ia and Ib as a whole from the viewpoint of Christian eschatology. The interpretation is beset with some difficulties, as she herself admits. The problem, as I see it, is to explain convincingly the mixture of Scandinavian and Christian myth on wall-hanging Ia in particular. Horneij thinks the missionaries could have included some pagan ideas in order to better illustrate the Christian doctrine about the end of the world. The animals inspired by Norse mythology are there in their function of representing the pagan world and the evil powers that will perish in the Ragnarøk. Thus, even Óðinn’s horse Sleipnir seems to belong with the monster animals, as Horneij points out.

The study by Wikman, presents a more consistent Ragnarøk interpretation. He agrees with the identifications of Old Norse motifs proposed by Horneij on piece Ia, but adds further elements. The eight-legged horse is of course Sleipnir, here bringing Óðinn to take counsel from Mímir’s head, which may be pictured by the object down to the right. In addition to the beast with gaping jaws (Fig. 12), Wikman identifies three further representations of the wolf Fenrir, depicting him in different situations. First, when he is fettered and Týr puts his hand into the mouth of the wolf. Second, the larger animal with its head bent downwards and lines on its body would represent Fenrir tearing dead bodies, an allusion to the Vǫluspá st. 50: “the Grey one tears the corpses”, slítr nái niðfǫlr. The third one shows the wolf at the moment when he has come loose from his chain that can still be seen hanging from his neck. To me, it seems rather unlikely that Fenrir should have been depicted four times on the same piece of tapestry in such varying shapes.

The statement that Surt throws fire upon the earth is, according to Wikman, illustrated by the “combs” of fire depicted above Loki and elsewhere on this textile. However, the most significant details that show the overall theme to be that of Ragnarøk are the three large rider figures with uplifted hands on wall-hangings Ia and Ib. They represent the three main gods at the moment when they perish in the final battle. To the far left of piece Ia we see how Óðinn is being caught up by the wolf Fenrir, and on piece Ib the Midgard Serpent turns his head toward the god Þórr to release its venom. The motif in the middle of the same wall-hanging depicts Surt riding up the bridge of Bifrost towards the guardian of the gods, Heimdall. Above, we find the third main god, Freyr, waiting to confront Surt beside the bursting sky.

The interpretation of wall-hangings Ia and Ib by Wikman is open to several critical remarks. It is not at all apparent that the three large figures should depict gods. We may equally well assume that they represent mounted worshippers or heroes. According to the Prose Edda, only Óðinn rides on a horse to the battlefield at Ragnarøk. The Vǫluspá uses the word ferr approximately “advances” followed by vega “fight” to describe the confrontations of Óðinn and Freyr with their respective opponents, whereas Þórr is said to walk, gengr, when he meets the Midgard Serpent; after the combat he takes, gengr (SnE: stígr), nine steps before falling down dead (Vsp 56; SnE 51). The figure riding up the “bridge” (or the “hill”) having an axe on its shoulder is less likely to rep-resent Surt, since the textual tradition pays much attention to the fact that Surt has a sword. Furthermore, it seems that the artist of the wall-hangings did not have in mind any hostile relationship between the three rider figures and the animals with which they are associated; still less is it possible to distinguish fighting scenes between them.

Wall-hanging II displays, according to Wikman, another aspect of the Ragnarøk myth, namely the new world to come after the destruction. The two figures on the eight-legged horse are considered to show Víðarr and Vali reappearing in the new world on the back of their father’s horse, whereas the sons of Þórr, Móði and Magni, arrive riding in a chariot which here looks like a sleigh. One of them is holding Mjǫllnir in his hand. For his Ragnarøk interpretation, Wikman attaches particular importance to the rectangular object with squares that can be seen above the horse and the chariot/sleigh. It represents one of the golden game bricks that the gods will find in the grass on the earth having arisen once again out of the sea (Vsp 59). Wikman cannot deny the fact that wall-hanging II shows obvious Christian elements, and he explains their presence by assuming the wish of the artist to relate pagan views of the world’s restoration with the Christian idea of Paradise.

To sum up, looking at the figurative scenes of the Överhogdal Tapestry without any preconceived notions about what should be there, one is far from convinced of their association with the Ragnarøk myth. If the wall-hangings had been designed to reproduce motifs from that myth, one would have expected a more unequivocal Ragnarøk iconography. The pictorial elements are never precise enough to exclude other interpretations.

Conclusion

Interpreting Viking age iconography is an intricate matter. The pictorial details are seldom so apparent as to remove every doubt about what they represent. The image of Christ on the Jelling Stone and the visit of the Magi on the Dynna Stone in Norway are two notable exceptions, however. With respect to the social and historical context, we have to recognize different actors who are involved in shaping the meaning of the iconography. There is first the person or persons who wished to set up a monument, to make a tapestry or some other object and paid for them, second, the artist who designed and produced them, and third, the viewers who may have associated the pictures with quite different things than those the patron and the artist had in mind.

In that respect, the pictures are multivalent and some people looking at them might have found motifs from the Ragnarøk myth where the representation of other ideas was originally intended. The answer to the question first raised: “Do we find Ragnarøk motifs in pictures?” has to be neither a clear “yes” nor a definite “no”. It seems more complicated than that, as I have attempted to show.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Kopár 2012.

- The rendering in English of Old Norse mythic names follows Larrington 2014.

- Hultgård 2017.

- Stephens 1884.

- Parker 1896.

- Olrik 1902.

- Berg 1958.

- Bailey 2003.

- Oehrl 2011:135–140.

- Kopár 2012:75–77, 90–94.

- For this interpretation and a summary of the previous discussion of the Gosforth Cross’s crucifixion scene, see Kopár 2012:94–101.

- For example Olrik 1902:163; Berg 1957–1958:212; de Vries 1956‒1957:§514; Oehrl 2011:163, 171; Kopár 2012:77, 91–92.

- Soga om nedstinginga i dødsriket 4.

- So Berg 1957–1958; McKinnell 2001; Bailey 2000; Oehrl 2011:169; Kopár 2012:92.

- de Vries 1956–1957:§558.

- Stephens 1884 and Reitzenstein 1924.

- Berg 1957–1958; Bailey 2003.

- E.g. Moltke 1985; Ellmers 1995.

- Hultgård 2017.

- Oehrl 2007; 2011.

- Jansson 1987:152; Moltke 1985:246‒248; Gschwantler 1990:521; Düwel 2001:139; McKinnell 2007; Oehrl 2011:229; Kopár 2012:71, 78, 125.

- Oehrl (2011:229–230) indicates a similar interpretation line.

- Sahlgren 1924.

- Horneij 1991.

- Wikman 1996.

- Karlin 1920.

- Branting & Lindblom 1928.

Bibliography

- Bailey, Richard N. 2000. Scandinavian Myth on Viking-Period Stone Sculpture in England. In G. Barnes & M. Clunies Ross (eds.). Old Norse Myths, Literature and Society. Proceedings of the 11th International Saga Conference 2–7 July 2000, University of Sydney. Sydney: University of Sydney, 15–23.

- Berg, Knut. 1957‒58. Gosforth-korset. En Ragnaroksfremstilling i kristen symbolikk. In Viking (English version in The Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 1958:21), 203–228.

- Branting, Agnes & Lindblom, Andreas. 1928. Medeltida vävnader och broderier i Sverige 1. Uppsala.

- Collingwood, W. G. 1927. Northumbrian Crosses of the Pre-Norman Age. London: Faber & Gwyer.

- Düwel, Klaus. 2001. Runenkunde. 3. Aufl. Stuttgart: Metzler.

- Ellmers, Detlev. 1995. Valhalla and the Gotland Stones. In O. Crumlin-Pedersen & B. Munch Thye (eds.). The Ship as Symbol in Prehistoric and Medieval Scandinavia. Copenhagen: Copenhagen National Museum, 165–171.

- Gschwantler, Otto. 1990. Die Überwindung des Fenriswolfs und ihr christliches Gegenstück bei Frau Ava. In T. Pároli (red.). Poetry in the Scandinavian Middle Ages. The Seventh International Saga Conference. Spoleto: Centro Italiano di Studi Sull‘ Alto Medioevo, 509–534.

- Heizmann, Wilhelm & Axboe, Morten (Hrsg.). 2011. Die Goldbrak-teaten der Völkerwanderungszeit. Auswertung und Neufunde. Berlin, New York: W. de Gruyter.

- Horneij, Ruth.1991. Bonaderna från Överhogdal. Östersund: Jämtlands läns museum.

- Hultgård, Anders. 2017. Midgård brinner. Ragnarök i religionshistorisk belysning. Uppsala: Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien.

- Jacobsen, Lis et al. (eds.). 1942. Danmarks runeindskrifter. Ved Lis Jacobsen og Erik Moltke under medvirken af Anders Bӕksted og Karl Martin Nielsen. København.

- Jansson, Sven B. F. 1987. Runes in Sweden. Stockholm: Gidlund.

- Karlin, Georg J:son. 1920. Över-Hogdals tapeten. En undersökning. Östersund: Jämtslöjds förlag.

- Kopár, Lilla. 2012. Gods and Settlers. The Iconography of Norse Mythology in Anglo-Scandinavian Sculpture. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Larrington, Carolyne. 2014. The Poetic Edda. Translated with an Introduction and Notes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McKinnell, John. 2001. Eddic Poetry in Anglo-Scandinavian Northern England. In J. Graham-Campbell et al. (eds.). Vikings and the Danelaw. Oxford: Oxbow, 327–344.

- Moltke, Erik. 1985. Runes and their Origin. Denmark and Elsewhere. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

- Oehrl, Sigmund. 2007. Das Große Tier. Zur Deutung eines spätwikinger-zeitlichen Bildmotivs. In A. Heitmann et al. (eds.). Tiere in skandina-vischer Literatur und Kulturgeschichte. Freiburg: Rombach, 41–71.

- Oehrl, Sigmund. 2011. Vierbeinerdarstellungen auf schwedischen Runensteinen. Studien zur nordgermanischen Tier- und Fesselungsikonografie. Berlin, New York: W. de Gruyter.

- Olrik, Axel. 1902. Om Ragnarok. In Årbøger for nordisk oldkyn-dighed og historie, 157–291.

- Parker, Charles Arundel. 1896. The Ancient Crosses at Gosforth, Cumberland. London: E. Stock.

- Reitzenstein, R. 1924. Weltuntergangsvorstellungen. Eine Studie zur vergleichenden Religionsgeschichte. Särtryck ur Kyrkohistorisk årsskrift 1924. Uppsala: A.-B. Lundequistska Bokhandeln.

- Sahlgren, Jöran. 1924. Runskriften på Överhogdalsbonaden. In Festskrift tillägnad Hugo Pipping. Helsingfors: Mercator, 462–464. Soga om nedstiginga i dødsriket (Niðrstigningar saga), tekst og omsetjing ved Odd Einar Haugen. Bergen 1985: Nordisk Institutt.

- Stephens, George. 1884. Prof. S. Bugge’s studier over nordisk mythologi. Supplement. In Aarbøger for nordisk Oldkyndighed 1884, 1–47.

- de Vries, Jan.1956‒57. Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte, I–II. Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

- Wikman, Sture. 1996. Fenrisulven ränner. Östersund: Jamtli.

Contribution (89-109) from Myth, Materiality, and Lived Religion: In Merovingian and Viking Scandinavia, edited by Klas Wikström af Edholm, Peter Jackson Rova, Andreas Nordberg, Olof Sundqvist, and Torun Zachrisson (2019, Stockholm University Press), published by OAPEN under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.