Did British people understand specific types of luxury goods as distinctly different from widely traded Asian commodities?

By Dr. Kate Smith

Associate Professor in Eighteenth-Century History

University of Birmingham

Introduction

The term ‘ivory’ describes the teeth or tusks of elephants and other mammals, including the Asiatic and African boar, the Arctic walrus, hippopotamus, warthog and whale. Ivory is a dense material that can be carved, engraved, turned, pierced and painted, and it has the strength and elasticity required for use both as a solid material and a veneer. In the Indian context, hunters removed ivory from the upper front tusks of the elephants found across the subcontinent, from the foothills of the Himalayas to the southern tip of Ceylon.1 This article explores the objects made from these tusks. It particularly focuses on the furniture pieces, made by skilled craftsmen in the subcontinent during the eighteenth century. Although Europe had a long tradition of ivory goods, often made from African and Asian elephant ivory (which was imported to Europe in greater quantities from the 1500s onwards), skilled Indian craftsmen made ivory furniture which presented European consumers with new and desirable aesthetic options.2 Ivory furniture thus acts as a lens through which to examine how individuals in the modern period related to objects from the subcontinent.

More particularly, ivory furniture is useful in considering a question central to The East India Company at Home: were objects purchased, transported, gifted and retained by East India Company (EIC) families understood as distinct from commodities traded more generally by the EIC? If so, how? Despite greater scholarly interest in commodities traded between Europe and Asia by companies such as the EIC, less is known about what objects that were imported through other, more exclusive, routes came to mean in Britain. Tillman Nechtman has argued that these objects were understood as deeply imperial: ‘a means of narrating an imperial identity, of spanning the distance between empire and nation’.3 While it is possible to make this argument for remarkable objects such as diamonds and dress, which were worn, gifted and scrutinized in public spaces such as the court, it becomes more difficult to track reactions to objects in domestic spaces.4 Yet, as this volume seeks to show, elite domestic objects and spaces were and are important in understanding how contemporaries confronted empire.

The range of Indian ivory furniture found in the collections of British museums, such as the V&A, as well as private collections, reflects eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britons’ desire to possess these exotic luxury goods. Yet as Anne Gerritsen and Stephen McDowall warn in the case of porcelain, the survival of many items in museum collections should be treated with caution and should not be understood as unproblematic evidence of historical popularity.5 Compared to better-known large-scale imports of domestic goods such as porcelain and textiles, however, ivory furniture’s presence in British collections is noteworthy precisely because the Company did not trade in it. In contrast to widely traded commodities like tea, textiles and porcelain, ivory furniture generally came to Britain through individual purchases made by EIC servants while in India. Moreover, whereas men and women in Britain could commission armorial porcelains or Chinese wallpaper at a distance, families or individuals tended to purchase items of ivory furniture while in India or when trading on the Indian coast. While these purchases could be acquired from Company individuals on the secondary market, their initial acquisition meant that they were firmly associated with families involved in trading. Furthermore, ivory wares proved difficult for European manufacturers to imitate. Given the limitations imposed by modes of purchase and manufacture, ivory furniture provides a particularly clear lens through which to ask, did British men and women understand specific types of imperial luxury goods as distinctly different from widely traded Asian commodities?

This article shows that although ivory furniture was increasingly made to European forms, contemporaries in Britain continued to understand it as representing a family’s link to the subcontinent. Although those lower down the social scale may have encountered ivory in small items such as snuffboxes, fans or ivory-handled cutlery, substantial furniture items were rare and valuable and thus marked elite status.6 Furthermore, ivory furniture continued to act as a prompt for retelling EIC family narratives long after the family members with links to the Company had died. Like the men and women who bought, collected and retained them, Company objects had complicated and global biographies, which shaped British material cultures long after the initial point of exchange. To understand the history and significance of these imperial objects then, we need to study their meaning both at the point of initial purchase and after it, as they moved on into other families, houses and institutions.

To capture the meanings that such objects held in wider British culture, this article examines ivory furniture both in situ in particular houses and at moments in which these goods moved and circulated. For it is often in moments of movement that objects emerge onto the historical record with their greatest force. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when people advertised objects for sale, singled them out for inheritance, or valued them, they tended to describe and arrange them, privileging certain components for inclusion or note. The texts created to record exchange and circulation offer historians important evidence through which to understand the meanings affixed to objects. These texts are steeped in particular conventions (the inventory, the sales catalogue), which need to be fully understood and accounted for as shaping forces, altering how descriptions and notes are written. Nevertheless, these texts provide important sources for the question at hand, and therefore this article uses newspapers, sale catalogues, inventories, wills and correspondence, to examine three different types of movement chronologically. After considering the production of these objects in India, the first part of the article examines the initial purchase of ivory furniture by members of the EIC elite, such as Edward Harrison (1674– 1732), in the early eighteenth century. It investigates why EIC officials bought ivory furniture by asking what the visual and material qualities of such pieces might represent. The second section of the article explores how collections purchased in the eighteenth century came to be dismantled and re- circulated in the nineteenth century, focusing on Warren Hastings and the sale of parts of his ivory furniture collection in the mid- nineteenth century. It examines the ways in which these goods were presented to interested parties and questions how and why newspaper writers used the sale of his country house Daylesford’s contents to embark on further retellings of the Hastings myth. The article ends by looking at non- EIC families, such as the Morrisons and the Kleinworts, who purchased Indian ivory furniture in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and asks what ivory objects might have meant when circulated outside EIC networks.

In following these avenues this article explores British public understandings of empire through ivory objects across the eighteenth, nine-teenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries. It finds that when exchanged between family members, gifted to other families or advertised on the open market after the death of the initial purchaser, ivory objects retained biographies that explicitly linked them to imperial geographies and narratives. As such, they played important roles in consolidating the narratives of empire constructed by and about particular families. At the same time, claims to origin were aided by the materiality of the objects, refer-ring as they did to particular regions, through the veneering techniques of Vizagapatam or the solid ivory turning technologies of Murshidabad. These objects thus enjoyed very different biographies and meanings to those commodities traded in large numbers by the EIC; as holders of particular meanings and narratives they also significantly shaped the places and people to which they became attached.

Production

Before the Battle of Plassey in 1757, Murshidabad was an important centre of ivory carving, primarily producing solid ivory pieces of furniture and decorative items.7 After the Treaty of Allahabad in 1765, as the British began to administer the diwani (tax collection and revenue administration) in the Bengal region, ivory carvers in Murshidabad increasingly sought to make goods that were desirable to Anglo-Indian consumers by producing furniture that more readily conformed to European styles. The circulation of print sources, such as Thomas Chippendale’s The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Director (1754) and George Heppelwhite’s The Cabinet Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide (1788), containing European designs, facilitated this process.8 Information about European designs was also transmitted to Indian workshops through the arrival of skilled furniture makers from Europe. Amin Jaffer gives particular credit to the presence of Charles Rose, a British furniture maker who was recorded as being in Bengal from 1772 and was registered as an inhabitant in Murshidabad in 1793.9 In the later eighteenth century, Murshidabad workshops began to produce chairs, candle stands and worktables. Particular skills in solid ivory carving allowed these workshops to produce items with distinctive arms and legs made of turned solid ivory. Jaffer has argued that Murshidabad ‘can now be recognised as most probably the source of most surviving Anglo-Indian solid-ivory furniture’.10

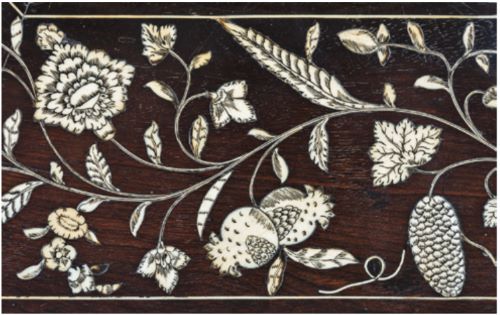

Much further south from Murshidabad, Vizagapatam on the Coromandel Coast was also a key production site for ivory furniture. From the late seventeenth century until the mid-eighteenth century, Vizagapatam was especially known for furniture that featured inlaid ivory work (see Figure 1). As in Murshidabad, artisans in this area increasingly used their ivory carving skills to produce furniture in Western forms.11

Between 1760 and 1780, Kamsali-caste ivory carvers in Vizagapatam began to use new techniques involving ivory veneer (see Figure 2). During this period ivory veneer gradually replaced ivory inlay as the main form of production. It was constructed by attaching a thin layer of ivory, by means of fixatives and rivets, to a wooden carcass. Decorative schemes appeared on these veneers through engraving the ivory and then filling the spaces with a type of black lacquer to create a monochrome design. While visiting Vizagapatam in 1801 with her mother and sister, Henrietta Clive witnessed the production of these ivory furniture pieces. On 4 April 1801 she described to her father (the Governor of Madras) watching monochrome ivory veneers being manufactured. She described how ‘We have seen the people inlaying the Ivory [with lac]’ and that ‘it appears very simple’. Henrietta observed that ‘they draw the pattern … they intend with a pencil and then cut it out slightly with a small piece of Iron, they afterwards put hot Lac upon it, and when it is dry scrape it off and polish it, the Lac remains in the marks made with the piece of Iron’.12

Switching to ivory veneer was an important change in aesthetic terms as it allowed makers a greater degree of flexibility when designing decorative schemes for furniture. Being able to implement a range of decorative schemes became important in the later eighteenth century as carvers began to incorporate increasingly elaborate figurative and architectural scenes into their furniture. Decorative ivory veneers proved a popular innovation with consumers. The circulation of European prints was important to the construction of these wares. Many of the veneer panels included scenes inspired by European prints, which became widely available on the subcontinent in this period.

As Henrietta Clive’s written description of ivory engraving for her father demonstrates, elite British consumers became increasingly curious about ivory’s material properties and the production techniques involved in making ivory furniture, workboxes, chairs and cabinets.13 For EIC women, imperial employments offered opportunities for observing production and gaining further material literacy. Some elite women who remained in Britain also became curious to further their knowledge; Margaret, second Duchess of Portland (1715–85) and Mary Delany (1700–88) took up ivory turning themselves.14 Alongside genteel and feminine interests in learning japanning techniques to produce objects in imitation of Chinese and Japanese lacquer wares, such forms of making provide a genteel and domestic variation on narratives of Asian import substitution, which, Maxine Berg argues, shaped British manufacturing distinctly in the eighteenth century.15 While a wider interest in ivory had emerged by the mid-eighteenth century, in the early decades of the century elite EIC families, such as the Harrisons, were collectors of ivory furniture pieces.

Purchase

Edward Harrison (1674–1732) inherited Balls Park in Hertfordshire after the death of his father Richard Harrison in 1726.16 Prior to establishing himself at the estate during the 1720s, Edward had worked in different capacities in the service of the EIC. It is possible that he began his EIC career as purser upon the London in the early 1690s.17 He certainly went on to captain EIC ships including the Powderham Castle, which sailed to Borneo in the late 1690s and the Kent, which he commanded on voyages to China in 1704–5 and 1706–10.18 Towards the end of 1710, after completing his final voyage on the Kent, Harrison was appointed Governor of Fort St George, Madras.19 After completing his tenure as Governor in 1717 Harrison returned to England, where he continued to be involved with the EIC and simultaneously established a career in Parliament. Between 1717 and 1722 he acted as MP for Weymouth and Melcombe Regis before going on to represent Hertford between 1722 and 1726. After moving to Balls Park in 1726, Harrison re-established himself once again within the Company by becoming Deputy Chairman of the Court of Directors in 1728, Chairman in 1729 and Deputy Chairman for a second time in 1731.20 By the time of his death in 1732 Edward Harrison was deeply embedded in EIC life – he had travelled to places as diverse as Macao and Batavia on Company business, he had led Company operations in Madras and had worked to govern the Company in London.

Edward Harrison’s EIC career is visible not only through Company records that list orders from the Directors for copper, tea, green ginger, rhubarb, wrought silks, raw silk and china.21 Harrison’s experiences of Asia and Eurasian trade were (and are) also made materially manifest through the objects he returned with and the wealth he acquired.22 Of particular interest here is the ivory furniture he purchased while in India, most likely as Governor of Fort St George between 1711 and 1717. Ivory furniture acts as an important signifier of Company connections for historians because once acquired by an individual it is one of the few Asian goods that can be identified in inventories.23 As a distinctive material, appraisers writing up probate records often included the descriptor ‘ivory’ when itemizing these objects.24 On Edward Harrison’s death in 1732 appraisers compiled an inventory of movable goods at Balls Park estate. Although Harrison had served as an MP in the later years of his life, in constructing the inventory the unnamed appraiser identified Harrison through his EIC career, as ‘the Honourable Edward Harrison Esq deceased late-Governor of Fort St George at his seat Balls in the County of Hertford’.25 The inventory demonstrates that the Harrisons were keen collectors of Indian (or Indian-inspired) textiles as well as of ivory furniture. Calico quilts appear in many rooms, including the Nursery, Drawing Rooms, Mrs Harrison’s Room, the House Keeper’s Room and Brown Room. The presence of calico in these rooms and not others marks both the rooms and the calicos as of less social importance. In contrast, those rooms specifically linked to Edward Harrison and his wife, contained more valuable Indian textiles such as chintz (spelt ‘Chince’ in the inventory).26 Similarly the ivory objects owned by the Harrisons appear in some of the house’s most important rooms. ‘The Governors Bed Chamber’, contained ‘a very curious India Book case inlaid with Ivory’, while ‘The Long Galery [sic]’ included twelve ebony ‘China’ chairs inlaid with ivory, as well as two similar elbow chairs and two couches.27 It is probable that Harrison bequeathed some of his movable household goods, including the bookcase, to his only child Etheldreda (commonly known as Audrey) (c.1708–1788). A 1737 inventory for her London home in Grosvenor Street notes that her per-sonal room contained ‘A Desk and book case inlay’d with Ivory’.28

In 1723 Etheldreda married Charles Townshend (1700–64) afterwards third Viscount Townshend.29 While the relationship between Etheldreda and Charles remained turbulent, the alliance instituted an important link between the EIC and the Townshend family. Such links were further consolidated when Charles’s brother Augustus captained the East Indiaman Augusta.30 On his final voyage, destined for China, another Townshend, Roger (d.1759), the fifth son of Etheldreda and Charles, joined Augustus and further consolidated the family’s links to global trade. Before preparations to sail on the Augusta began, Charles and Augustus worriedly wrote numerous letters, assuring each other that Roger was sufficiently prepared for the voyage. Augustus advised that around £200 would be required to see Roger set up on ship and during the journey.31 After setting sail in February 1745, Roger finally returned to Britain in November 1749. He returned without his uncle who had died on board ship and despite the Augusta being captured by the French as it tried to return home.32

The difficulties Roger experienced might explain why on return-ing he was distinctly keen to switch profession, hoping instead to join the army or navy. Charles wanted Roger to remain in the Company, but remarked to his brother that at least a change would mean that the family were no longer dependent on the solicitations of the Court of Directors.33 While the Townshend family’s growing range of connections to the Company is made visible through these professional concerns, Etheldreda’s earlier connections to the Company through her father and his links to the Coromandel Coast were manifest through material possessions that were recognizably Indian and more specifically, recognizably from Vizagapatam in the Madras Presidency of which Harrison was Governor.

Placed on the market in 2011 and attributed as one of Edward Harrison’s pieces, an ivory-inlaid teak, ebony and tortoiseshell bureau-cabinet continues to act as a material manifestation of Harrison’s particular links to the subcontinent.34 The bureau-cabinet is likely the ‘Desk and book case inlay’d with Ivory’ that belonged to Etheldreda, which she had inherited from her father. Moreover, the Harrison bureau is aesthetically similar to one purchased by Richard Benyon (1698–1774) who worked as Governor of Fort St George, Madras after Harrison, between 1735 and 1744.35 As pieces featuring ivory inlay work, these bureau-cabinets linked Harrison, Benyon and their families to Madras and the Coromandel Coast. Unlike more perishable goods such as textiles, these valuable and highly valued cabinets remain as testimony to such connections. They have been passed down through generations and retain a strong sense of provenance.36

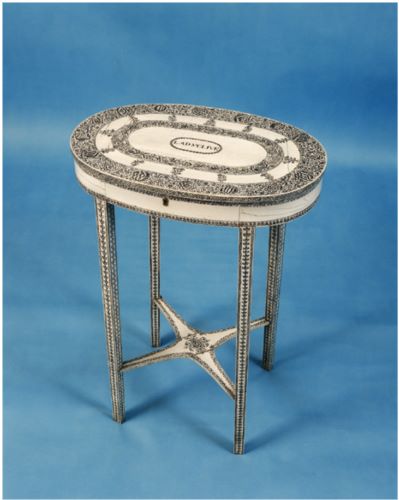

Not all ivory furniture pieces, however, stayed within EIC families. Company servants also purchased them to be later gifted or sold. Moreover, while it was the EIC elite who predominantly purchased ivory furniture in the early eighteenth century, in the later decades of the period, those (slightly) lower down the social ladder were also able to acquire such pieces. Evidence for the consumption of ivory furniture by those below the Governor rank can be seen through the example of Captain James Monro (1756–1806) who purchased a miniature cabinet with ivory veneers, made in Vizagapatam in the second half of the eighteenth century. As it displays such an elaborate collection of ivory veneer sections, the piece can be dated to the post-1760 period when the majority of Vizagapatam ivory production shifted focus from ivory inlay work to ivory veneer.

In researching the miniature cabinet, furniture historian Elizabeth Jamieson demonstrated how objects themselves are sometimes able to allude to their histories.37 Hidden on the sandalwood top of the lower section of the cabinet Jamieson found an inscription that read ‘Out of No. 201 Houghton/Capt Monro’. The inscription connects the cabinet to the East Indiaman, the Houghton. Between 1766 and 1789 James Monro was a member of the crew on every voyage that the Houghton took. Monro, the third son of physician John Monro,38 began his seafaring career at the age of 10 when he worked as a captain’s servant on the Houghton as it travelled out to trade at Whampoa near Canton. After this early engagement with shipping, Monro went on to work as midshipman and fifth mate on the Houghton before completing a further voyage as fourth mate on the Osterley II.39 At the age of 20, Monro returned to the Houghton as second mate, a role he also performed on the York before finally gaining command of the Houghton for the first time in 1782. After this, Monro captained the Houghton on three further journeys to Asia.40 Most significantly for this article, on his voyage to Bengal, as second mate on the Houghton, between 1777 and 1778, Monro stopped at Vizagapatam. The port had acted as an important English trading post or ‘factory’ since 1668. After 1768, however, when the Northern Circars came under the control of the English East India Company, Vizagapatam increased in importance as a place of settlement and a lucrative port for conducting Coromandel Coast trade in textiles.41 Here Monro would have been able to see a range of ivory furniture pieces at first hand, perhaps encouraging him to purchase a piece later on when he had risen to the position of captain and was able to afford it. As captain, Monro would have been well placed to purchase pieces such as this and to transport them back to Britain as part of his privilege allowance.

James Monro’s letters demonstrate that he purchased smaller items such as ceramics and furniture while on voyage, for gifting and sale once he returned to England. Writing to his elder brother Charles as he sailed from China to St Helena in November 1785, James described how he had managed to purchase some Chinese tables and tea sets, as well as some small chairs.42 He generously offered Charles and his new wife first refusal on his bountiful supplies. Like other Company men, James Monro appears to have depended upon his brother for support and information.43 Even when in England, but away from the centre of news and markets in London, James requested Charles to complete payments and order clothes on his behalf.44 After James’s death in 1806, Charles continued to play an important role in the life of his family. James’s wife Caroline (d. 1848) outlived him and Charles took responsibility for her and the remaining children. For instance, a letter from 1811 suggests that Charles was actively involved in managing the family’s financial affairs, particularly those of James’s daughters. He ensured that household goods such as furniture were turned into investments such as an ‘Old South Sea Ann’ty’ and kept distinct from the ‘Estate’. After Caroline’s death it was these items and not the ‘Estate’ that would have been allotted to her daughters and Charles realized that they would ‘not be generally divisible’ or financially useful.45 If the Vizagapatam cabinet remained in the family rather than being sold when James returned from India, it may well have been unsentimentally sent to market to provide for his daughters and their future life.46 These ivory objects, bearing materials from the subcontinent and Africa, produced through the enactment of highly skilled Indian craftsmanship to European designs, remained valuable and desirable commodities. Their links to the subcontinent through the EIC were part of their allure. Moreover, they often experienced an afterlife linked to, but independent of, their Company history.

Dispossession

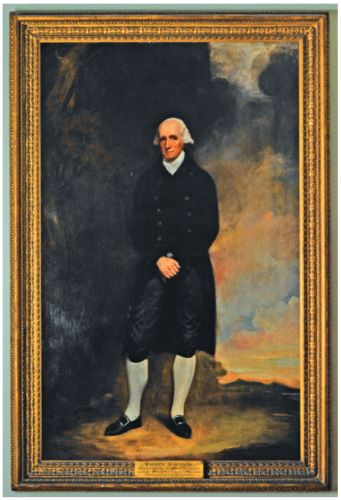

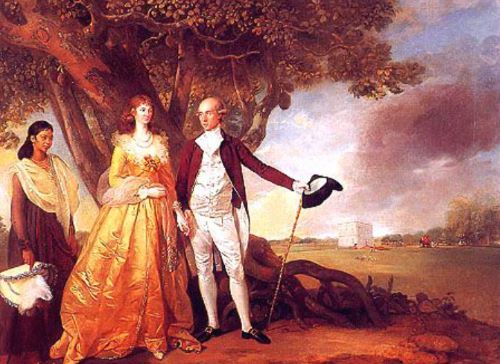

Throughout the late eighteenth century Warren Hastings (1732–1818) (see Figure 3) and his wife Marian (1744–1837) held an important place in Britons’ imaginings of empire. The press and the public used the Hastings as an important conduit through which to understand empire broadly and Britain’s relationship to the subcontinent more particularly. They did so in three key ways: first, through Hastings’s career, second, through his marriage to Marian and finally, through his estate – Daylesford.

Warren Hastings’s career path mirrored Britain’s increasingly imperial role in the subcontinent. Hastings joined the EIC in 1750 after his guardian Joseph Creswicke secured him a writership in Calcutta. Twenty-two years later in 1772, Hastings rose to the position of Governor General. Although Hastings fulfilled many objectives, his long tenure as Governor (13 years in total) was also marked by war and accusations of corruption.47 As Britain’s control of the American colonies became weaker during the course of the Wars of Independence, the British public’s interest in India increased. When Hastings resigned in 1785 and returned to Britain, his impeachment and trial (1787–95) had a ready audience.

As Tillman Nechtman has shown, interest in Hastings’s personal life further consolidated and shaped the public’s desire to understand the nature of Britain’s empire.48 Warren Hastings first met Marian von Imhoff (née Anna Maria Apollonia Chapuset) while sailing to India in 1769. At the end of the journey Marian went with her husband to Calcutta, while Hastings went to Madras to take up the post of second-in-council at Fort St George. Once appointed Governor in 1772, Hastings moved to Calcutta, the seat of the Company’s government, where Marian and her husband Baron Carl von Imhoff were resident. In 1773 Marian remained in India when the Baron returned to Europe. Her husband divorced Marian in 1776, and a year later she married Hastings. Their marriage underlined how the social rules structuring life in the metropole often became blurred once abroad.49 When the couple returned to Britain in 1785, Marian was subject to further criticism because she both wore and distributed the fruits of empire. She supposedly appeared at court decked out in diamonds and offered up rich and elaborate gifts to the Royal family – including ivory armchairs from Murshidabad. Critics, such as Fanny Burney, feared that Marian would undermine the morality of court, bringing it under the influence of empire and imperial riches.50

The couple’s country house, Daylesford, also acted as an important part of the family’s myth. During his trial, for example, the press used Hastings’s purchase of Daylesford variously as a means to reaffirm his morality and immorality. The Hastings family had been linked to the Daylesford estate since the thirteenth century, but when they experienced reduced circumstances in the early years of the eighteenth century, the lands were sold off. Both Hastings’s father and grandfather continued to live near the estate and Warren Hastings’s desire to re-acquire it and re-establish the family fortune acted as a compelling part of his life narrative. As the trial wound on, writers explored Hastings’s desire and motives for different ends. For example, articles in both the St James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post and the World discussed his purchase of Daylesford in terms of his family’s long attachment to the estate. An anonymous letter published in the St James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post on 29 September 1785 (after Hastings had returned to England) noted that although Hastings had been linked to several houses, he never had any intention of purchasing anything other than Daylesford.51 The writer went on to note that Daylesford had been in the possession of his family from ‘1281 to 1715’ and that in reacquiring it Hastings sought to return to the status of ‘respectable Country Gentleman’.52 Similarly a biographical sketch published in the World at the height of his trial in 1792 noted that Hastings’s grandfather had been forced to sell the Daylesford estate, ‘which had been possessed by the family of Mr Hastings from 1280 to 1715’.53 In contrast to using Daylesford to make claims regarding the respectability and longevity of the Hastings family, other publications used Daylesford (and more particularly its rebuilding) to suggest Hastings’s duplicity. On 6 October 1795 (after the final acquittal), for example, rather than take pity on Hastings and the high costs he incurred as a result of the lengthy trial, The Morning Post and Fashionable World took umbrage at the Indian profits he was seen to retain. They particularly noted the money Hastings had spent on ornamenting his gardens. The writer quipped that ‘To throw away [£]50,000 in making Shrubberies and Gravel Walks is an unquestionable proof of poverty.’ It further asked ‘When a man throws away [£]90,000 in merely ornamenting the grounds about his Country House, what may we calculate his whole fortune to be?’54

By examining how the Hastings family were described in the press and other print forms, it is possible to understand the role that objects, such as ivory furniture, played in consolidating links between individuals and empire. That Daylesford was an important site through which the public could discuss Hastings (and by implication empire) became doubly apparent during its sale in the 1850s. In this instance, ivory furniture was of particular importance in providing signifiers that linked Hastings to empire. The sale of Daylesford in the early 1850s and the subsequent sale of its contents in August 1853 attracted the attention of newspapers across Britain. Such was the perceived public interest in these events that following the sale, on 10 September 1853 the Oxford Journal republished an article that had appeared in The Times, which proposed that:

It is scarcely possible to read this announcement of the sale of Daylesford without emotion – so much of hope and feeling had been bound up with the trees and pastures of that pleasant spot … Well did he [Hastings] keep his word [to reclaim Daylesford] … He did purchase the estate – he did build upon it a mansion suitable for the Inhabitants of an English country gentleman.55

Why was the Daylesford sale such an important event? Cynthia Wall has drawn our attention to the importance of understanding auctions and house sales as ‘dismantlings’. For Wall ‘The auction is the site for the disassembling of one instance of the existing world and the promise of the reconstruction of a new one.’56 As The Times article reprinted in the Oxford Journal demonstrates, the attention that the sale of Daylesford and its contents attracted, focused specifically on the house’s relationship to Warren and Marian Hastings rather than its most recent owner (Marian’s son by her first marriage) Charles von Imhoff, or its purchaser, a financier called Mr Grisewood.57 The catalogue, and its later dissemination, constructed and consolidated this focus. It too primarily understood Daylesford House as ‘The Seat of the late Right Hon. Warren Hastings’, while the sale itself was framed as occurring ‘By orders of the Executors of the late Mrs Hastings’.58 Playing to the connection between Warren and Marian Hastings and Daylesford, the frontispiece of the sale catalogue hints at the end of such connections and the dismantling of their lives.

Even in the 1850s, as his house and contents were sold, Warren Hastings’ connection to empire remained the key frame through which he was understood. Such connections were significantly underlined through material manifestations of empire – such as ivory furniture. In its first few lines, the frontispiece to the Daylesford sale catalogue highlighted the ivory furniture belonging to the Hastings. It described itself as ‘A catalogue of the valuable contents of the mansion embracing a unique & costly drawing room suite of solid ivory, finely carved and gilt, and finished in the Richest Style of Oriental Magnificence, comprising Two beautifully formed Sofas, Nine Chairs, Two Ottomans, a Table, and a pair of Screens’.59 Ivory furniture, brought from the subcontinent, was the first type of object that any potential purchaser was asked to consider. Rather than ‘Indian’, however, in this part of the catalogue its geographical origin is unclear. It is marked as ‘Oriental Magnificence’ in style, simultaneously suggesting at its perceived exuberance and that of Asian goods more generally. Inside the catalogue ivory furniture was further highlighted, this time through the use of typographical techniques, rather than hierarchical positioning. Other pieces of furniture in the Daylesford collection were described through a standardized font of the same point size. In contrast, bolding, capitalizing and italicizing marked out the ivory furniture pieces as distinctive, important and (it could be assumed) valuable – here there were important things to see that required special billing. In employing typographical strategies to emphasize certain goods, the catalogue reimagined the sale as spectacle and show.60 For instance the catalogue listed the drawing room contents as:

A SOFA OF SOLID IVORY, in the richest style of Oriental magnificence, superbly carved and richly gilt, the elbows finished with tiger heads, stuff seat and two bolsters, covered en-suite with curtains, and extra Indian dimity cases – 6 ft. 6 long

THE COMPANION COUCH

A PAIR OF ELBOW CHAIRS, IN SOLID IVORY, of corresponding style, and of equal magnificence with sofas

A PAIR OF DITTO

A PAIR OF DITTO

ONE DITTO

ONE DITTO

ONE DITTO (damaged)

A SOLID IVORY TABLE, of elegant form, on shaped legs, beau-tifully carved and gilt, fitted with two drawers with silver locks and handles, and covered with fine green cloth, edged with silver lace

A SQUARE FOOT OTTOMAN, OF SOLID IVORY, gilt, stuffed and covered en-suite with sofas

A DITTO

A PAIR OF CARVED IVORY ORIENTAL OFFICIAL STAFFS (5ft. long), ornamented with silver gilt bands and wire, mounted in ebonized and gilt frames and silk mounts to form fire screens, and white Indian dimity covers

Whereas the catalogue placed little significance on the material qualities of other items, in promoting the ivory objects its author was at pains to highlight the importance of ‘solid ivory’ furniture. In nineteenth-century Britain, as understandings of ‘veneer’ shifted from skilled practice to false and cheap rendering, claims of ‘solid ivory’ would have been quickly understood as holding higher value.61 As noted earlier, underlining this quality might have also made certain purchasers aware that these items likely came from a particular part of the subcontinent – Murshidabad. For those with an understanding of the subcontinent, the catalogue provided grounds on which to establish a connoisseurial engagement with the auctioned items.

While the catalogue imagined the ivory furniture within the expected space of the drawing room, it also destabilized the idea of a domestic setting by itemizing the pieces. As with other auction catalogues, such lists create a productive tension between the idea of plenty (something for everyone) and exclusivity (particular objects are of special import). At the same time, by using the convention of newspaper advertisements, which appeared to artlessly itemize many goods, auction catalogues underlined that these objects were for sale and could sell themselves.62 Rearranging the items for sale both by randomizing their location in the lists and giving importance to some over others, the Daylesford catalogue reordered the Hastings’ possessions and allowed them to be reimagined within other homes and lives.63

Alongside dismantling Hastings’s home, articles appearing in news-papers across Britain in 1853 used the event to re-examine Hastings’s life and legacy. Central to these re-examinations was (perhaps inevitably) his imperial career. The importance of imperial connections in shaping what Daylesford (and Hastings) was and meant, was further confirmed through the way in which the objects were arranged for sale. The subcontinent loomed large in the contents sale, through the presence of a collection of ivory furniture. It was this and not the mahogany and satinwood furniture that received top billing. As such this example reminds us of the important role furniture played in representing the subcontinent and Britain’s imperial ambitions there. The sale of the contents of Daylesford also reminds us that by the nineteenth century an active market arose that enabled the recirculation of goods originally linked to EIC families in the eighteenth century. The dispossession of collections, such as that belonging to the Hastings family, also offered up an occa-sion upon which to dismantle their family narrative. Yet as the Hastings example shows, it also reified the Hastings drama, allowing others to purchase pieces understood as important to the imperial story. Chief amongst these, as the sale catalogue promised, was the ivory furniture largely bought from skilled craftsmen in Murshidabad. What happened to pieces such as these as they entered new settings and new narratives? How were they presented and understood? What position did they hold?

Recirculation

By studying examples of ivory furniture situated in British country houses in the nineteenth, twentieth and twenty-first centuries, we can begin to understand the changing positions that objects such as these held for contemporaries. This section of the article examines ivory furniture pieces held in two specific collections – Basildon Park, Berkshire in the nineteenth and early twentieth century and Sezincote, Gloucestershire in the mid-twentieth century. Both these collections were (and are, in the case of Sezincote) situated in country houses that were significantly rebuilt in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries as a result of Company money. Both sites have EIC narratives to reclaim and explore, making them productive examples of the recirculation of meaning through Indian ivory furniture. I will first explore a pair of ivory chairs owned by the Morrison family in the nineteenth century and then briefly contrast these purchases with those made by Sir Cyril and Lady Kleinwort in the 1940s. Is it possible to recover the intention of these individuals in purchasing these items? What were the narratives told by these pieces? What did they mean and what purposes did their purchase enable or allow? What histories are revealed by the long afterlives of imperial objects?

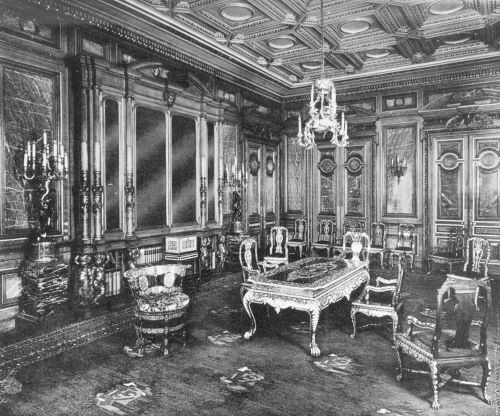

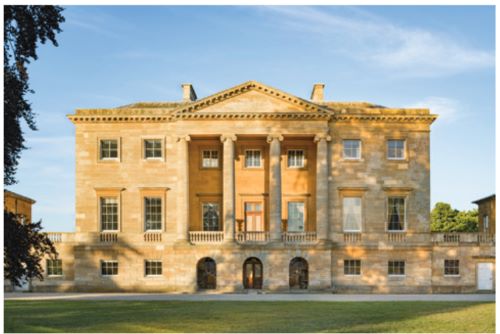

James Morrison purchased Basildon Park (see Figure 4) in the late 1830s. Originally built by EIC servant Francis Sykes in 1776, the mansion and estate at Basildon passed to Sykes’s son and then soon after his grandson Sir Francis (3rd Baronet), who was just four years of age when he inherited. Mismanagement during his minority and the fulfillment of the expensive tastes of the 3rd Baronet and his wife meant that the family fell into serious financial difficulties. The estate was put up for sale in 1829 and after much negotiation was finally sold to James Morrison in 1838. Morrison made his wealth not through the EIC, but rather through a textile trading business based in London. His financial successes allowed him to also establish a career as a Member of Parliament and accumulate a large and prestigious art collection, which he housed at Basildon Park.64

On James Morrison’s death in 1857 the house passed to his eldest son Charles and was inhabited by Charles’s sister Ellen. On Charles’s death in 1909 the house passed to his son Archie. In straitened circumstances the house was sold in 1929 and was purchased and restored by Lord and Lady Iliffe in the 1950s. Before the sale of the estate itself, Archie Morrison sold its furniture collection in 1920. Amongst other items, the furniture sale catalogue demonstrates that the Morrison family owned a pair of ivory chairs.65 The chairs do not appear in the 1859 inventory of Basildon Park or the Morrison’s London house in Harley Street.66 Rather than acquiring them from Basildon’s previous residents, the Sykes family, it seems likely that Charles or Archie purchased them on the English or European market. Their intention in purchasing them is unclear – did they buy them to reference the earlier connections of Basildon to the EIC through the Sykes family? Did they purchase them because they had become a de rigueur piece within British country houses? Did they purchase them because in the late-nineteenth century they once again became fashionable?

The Morrison family’s intention in purchasing these intricately designed goods appears opaque in the historical record. In contrast the Kleinwort’s intention is perhaps more readily discerned. As Jan Sibthorpe’s research on Sezincote, Gloucestershire has shown, in the mid-twentieth century the Kleinwort family worked to restore Sezincote to its early-nineteenth-century splendour, reinvigorating Indian elements and features that had originally been designed by Samuel Pepys Cockerell (1753–1827) and installed for his elder brother Charles Cockerell (1755–1837).67 Situated just a few miles from Warren Hastings’s Daylesford, Sezincote came to be partially inherited by EIC official and private trader Charles in 1798. He then fully purchased it from his siblings in 1801. He worked with his brother Samuel to design and build one of the few Indian-inspired country houses of the period. Sezincote fell out of the possession of later Cockerell family members and was purchased by James Dugdale in 1884. It remained in the Dugdale family until the Kleinworts purchased it, in a somewhat dilapidated condition, in 1944. As part of this renovation, Lady Kleinwort purchased at auction in the 1940s, a set of six sandalwood chairs, veneered with ivory, highlighted with black lac and gilt, with cane seats.68 As with the Morrison pieces, the veneering on the chairs suggests that they were made in Vizagapatam in the 1770s. Displayed in the house they act to visually reaffirm Sezincote’s connections to India.69

The Sezincote chairs underline how ivory furniture continued to hold its EIC connections long after the Company’s demise. In recent years when ivory furniture pieces have come onto the market, their provenance and thus their links to an EIC past through reference to a particular individual, have been underscored. As such then, these objects have acted as relatively stable markers of Britain’s involvement in and relationship to the subcontinent.

Conclusion

Exploring the production, purchase, dispossession and recirculation of ivory furniture reveals the different kinds of value at play within imperial material cultures – emotional, monetary, political and historical – and the ways in which these values have changed over time. Purchasing these objects while in Company service and engaging with the often difficult process of bringing them home intact, early EIC families recognized their emotional value as pieces which could mark their imperial service and experiences on the subcontinent. Bequeathed to family members, as in the cases of Edward Harrison, these pieces continued to act as important affective objects as they came to be possessed and used by younger generations. Later in the eighteenth century, their purchase by EIC servants not only for familial use but also for possible resale on the open market, suggests that as European audiences became aware of these pieces (and more particularly their increasingly European forms and styles), they gained market value and could be easily resold. Recognizing, and simultaneously adding to, their status, these items were also considered wor-thy gifts within the court. Given to Queen Charlotte by Warren Hastings, ivory furniture pieces obtained political value in the later eighteenth century. Nevertheless, after what might be understood as their high point in the late-eighteenth century, in the nineteenth century these same pieces of ivory furniture were understood to retain their links to the previous century and in recirculation became principally valued for their historic connections. In the postcolonial era, they offered compelling instruments for the reconstruction of a particular imperial British past.

Uncovering the changing values embedded within ivory furniture pieces is important in demonstrating the ways in which objects from the subcontinent acted as sites upon which and through which contemporaries recognized links to the EIC and empire. Despite being increasingly made to European designs, these pieces often resisted naturalization and remained connected to the narratives of empire that families and other individuals constructed – a process encouraged by appraisers, auctioneers and country house owners. Becoming entangled in different forms of meaning making, these objects came to embody empire and even in the twentieth century could be called upon to represent imperial links.70 Easy to recognize and difficult to imitate, their material form marked these wares out as distinct. Such recognition was reproduced in the historical record by appraisers constructing inventories, auctioneers writing catalogues, and historic house staff producing guidebooks. Reproduced and replicated over time, the distinction of ivory furniture marked these pieces, making them distinct from the more ubiquitous porcelain and textile goods. In consequence, this article demonstrates that what might be regarded as a domestic object – ivory furniture – exists as an important route through which to understand the ways in which EIC families, but also British culture more broadly, understood and recognized Britain’s imperial projects.

Endnotes

- Amin Jaffer, Luxury Goods from India: The Art of the Indian Cabinet-Maker (London, 2002), 125.

- Kirsten A. Seaver, ‘Desirable Teeth: The Medieval Trade in Arctic and African Ivory’, Journal of Global History, 4:2 (2009), 276.

- Tillman W. Nechtman, Nabobs: Empire and Identity in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Cambridge, 2010), 170.

- For the importance of being seen to wear Indian goods in public see Tillman W. Nechtman, ‘Nabobinas: Luxury, Gender, and the Sexual Politics of British Imperialism in India in the Late Eighteenth Century’, Journal of Women’s History, 18:4 (2006), 8–30.

- Anne Gerritsen and Stephen McDowall, ‘Global China: Material Culture and Connections in World History’, Journal of World History, 23:1 (2012), 5.

- For snuffboxes and fans for example see ‘lost property’ notices in Post Boy (London), 8–10 April 1712; Daily Courant (London) 18 February 1713; Daily Courant (London), 1 April 1713.

- Jaffer, Luxury Goods from India, 82.

- Jaffer, Luxury Goods from India, 85.

- Amin Jaffer, ‘Tipu Sultan, Warren Hastings and Queen Charlotte: The Mythology and Typology of Anglo-Indian Ivory Furniture’, The Burlington Magazine, 141:1154 (1999), 278; British Library, European Inhabitants of Bengal, IOR/0/5/26.

- Jaffer, ‘Tipu Sultan, Warren Hastings and Queen Charlotte’, 277.

- Amin Jaffer and Karina Corrigan, Furniture from British India and Ceylon: A Catalogue of the Collections in the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Peabody Essex Museum (London, 2001), 172.

- As cited in Mildred Archer, Christopher Rowell and Robert Skelton, Treasures from India: The Clive Collection at Powis Castle (London, 1987), 84.

- The increased interest in the manufacturing of ivory products mirrors a more general and emerging interest on the part of consumers as to how consumer goods were made. See Kate Smith, Material Goods, Moving Hands: Perceiving Production in England, 1700–1830 (Manchester, 2014).

- Stacey Sloboda, ‘Displaying Materials: Porcelain and Natural History in the Duchess of Portland’s Museum’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 43:4 (2010), 464.

- Maxine Berg, ‘In Pursuit of Luxury: Global History and British Consumer Goods in the Eighteenth Century’, Past & Present, 182:1 (2004), 85–142; Maxine Berg, ‘From Imitation to Invention: Creating Commodities in Eighteenth-Century Britain’, Economic History Review, 55:1 (2002), 1–30.

- Paul Sangster, Balls Park, Hertford (Caxton Hill, 1972), 3.

- See ‘The Harrison & Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, The Exceptional Sale, Christie’s, London, 7 July 2011, 60. With many thanks to Sharon Goodman for her original research on the Harrison and Townshend collection, which has greatly enhanced this study, particularly in uncovering the Rainham Hall 1732 inventory and the Lord Lynn 1737 inventory (see below).

- See Anthony Farrington, A Biographical Index of East India Company Maritime Service Officers, 1600–1834 (London, 1999), 355; Anthony Farrington, Catalogue of East India Company Ships’ Journals and Logs 1600–1834 (London, 1999), 359 and 515.

- Sir Charles Lawson, Memories of Madras (London, 1905), 54.

- George K. McGilvary, East India Patronage and the British State: The Scottish Elite and Politics in the Eighteenth Century (London and New York, 2008), 5.

- British Library, ‘Order and instructions to Captain Edward Harrison, Edward Herris and John Cooke, Supercargoes of the Kent, bound for Canton’, 1 December 1703, IOR/E/3/95, 83–86.

- Edward Harrison also used his connections to commission an armorial porcelain service from China. See David Sanctuary Howard, Chinese Armorial Porcelain (London, 1974), 43.

- For discussion of use of inventories in historical research see Nancy Cox and Jeff Cox, ‘Probate 1500–1800: A System in Transition’, in Tom Arkell, Nesta Evans and Nigel Goose (eds), When Death Do Us Part: Understanding and Interpreting the Probate Records of Early Modern England (Oxford, 2000), 13–37; Margaret Spufford, ‘The Limitations of the Probate Inventory’, in John Chartres and David Hey (eds), English Rural Society, 1500–1800: Essays in Honour of Joan Thirsk (Cambridge, 1990), 139–74.

- This is in contrast to ceramic goods, which are often difficult to identify with any clarity in inventories. See Francesca D’Antonio, ‘The Willow Pattern: Dunham Massey’, East India Company at Home (June, 2014), 3. http://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah/files/2014/06/Willow-Pattern-PDF-Final-19.08.14.pdf.

- Raynham Hall Archive, ‘An Inventory and Appraism’, 15 December 1732, RAS H1/4/3. With thanks to the Marquess Townshend’s kindness in granting permission for information from the Raynham Hall Archive to be cited. The inventory is also mentioned in ‘The Harrison & Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, 61.

- Raynham Hall Archive ‘An Inventory and Appraism’, 15 December 1732, RAS H1/4/3.

- Raynham Hall Archive ‘An Inventory and Appraism’, 15 December 1732, RAS H1/4/3. For images of bookcase see ‘The Harrison & Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, 64–7.

- British Library, Townshend Papers, ‘An Inventory of the Right Honorable the Lord Lynn’s Goods taken at His Lordships House in Littel Grosvenor Street this 11 day of July 1737’, Ms. 41656, 209–10. The inventory is mentioned in ‘The Harrison & Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, 62.

- Linda Frey and Marsha Frey, ‘Townshend, Charles, second Viscount Townshend (1674–1738)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford, 2004). Accessed 6 Jan 2017. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/27617; John Martin, ‘Townshend, Etheldreda, Viscountess Townshend (c.1708–1788)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004). Accessed 6 Jan 2017. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/68358.

- Farrington, A Biographical Index, 793. He captained the Augusta on the following voyages: 1738/9, 1741/2 and 1744/5.

- Raynham Hall Archive, Augusta Townshend to Charles Townshend, 24 December 1744, RAS B2/6.

- Raynham Hall Archive, A Journal of a Voyage from London to China on Board the Augusta Kept by Roger Townshend Anno Domini 1745, RAS H4/3.

- Raynham Hall Archive, Charles Townshend to a brother, 5 December 1747, RAS B2/6.

- See ‘The Harrison & Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, 60–77.

- See Kate Smith, ‘Imperial Objects? Country House Interiors in 18th-Century Britain’, in Jon Stobart and Andrew Hann (eds), The Country House: Material Culture and Consumption (London, 2015), 111–18. See also ‘The Harrison & Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, 66.

- See ‘The Harrison & Townshend Anglo-Indian Furniture’, 60–77. This strong sense of provenance can be seen in the marketing materials produced for the piece during its sale in 2011. Items no longer made available by Christie’s. See also catalogue details for Sir Thomas Rumbold’s ivory desk, another Madras Governor: http://www.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/col-lections/furniture/vizagapatamdesk.

- Many thanks to Elizabeth Jamieson, MA (Freelance furniture historian) for allowing me to include the research she completed for Bonhams.

- Jonathan Andrews, ‘Monro, John (1715–1791)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, 2004). Accessed 21 May 2014. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/18976.

- Farrington, A Biographical Index, 552.

- Farrington, A Biographical Index, 552.

- Jaffer and Corrigan, Furniture from British India and Ceylon, 172.

- Elizabeth Jamieson mentions this letter in the research she completed on the cabinet for Bonhams. London Metropolitan Archives, James Monro to Charles Monro, 22 November 1785, Acc/1063/034.

- This close relationship appears to be the case as a selection of letters between the two brothers survives in the archives of the London Metropolitan Archives. The survival of these letters suggests they were valued, but as it is only them that survive it might also be misleading in terms of the wider network James Monro established and used while working as a captain for the East India Company. See multiple letters in London Metropolitan Archives, James Monro to Charles Monro, ACC/1063/014–043 (1775–1790). Many thanks to Elizabeth Jamieson for the reference to these letters.

- London Metropolitan Archives, James Monro to Charles Monro, 31 January 1780, ACC/1063/015.

- London Metropolitan Archives, Charles Monro to Mrs Caroline Monro, 14 January 1811, ACC/1063/121.

- For more on the inheritance of household goods by women see Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, ‘Hannah Barnard’s Cupboard: Female Property and Identity in Eighteenth-century New England’, in Ronald Hoffman, Mechal Sobel and Fredrika J. Teute, Through a Glass Darkly: Reflections on Personal Identity in Early America (Chapel Hill and London, 1997), 238–273; Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, The Age of Homespun: Objects and Stories in the Creation of an American Myth (New York, 2002).

- P. J. Marshall, ‘Hastings, Warren (1732–1818)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford, 2004). Accessed 19 May 2014. http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/12587.

- Nechtman, ‘Nabobinas’, 8–30.

- Nechtman, Nabobs, 197.

- Nechtman, Nabobs, 190.

- Hastings landed at Plymouth on 13 June 1785.

- St James’s Chronicle or the British Evening Post (London), 29 September 1785.

- World (London), 16 July 1792.

- Morning Post and Fashionable World (London), 6 October 1795.

- Oxford Journal (Oxford), 10 September 1853.

- Cynthia Wall, ‘The English Auction: Narratives of Dismantlings’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 31:1 (1997), 3.

- Information regarding Grisewood taken from the Dundee Courier, 14 September 1853.

- Catalogue of the Valuable Contents of Daylesford House, Worcestershire, the Seat of the Late Right Hon. Warren Hastings (London, 1853).

- Catalogue of the Valuable Contents of Daylesford House.

- Barbara Benedict, ‘Encounters with the Object: Advertisements, Time, and Literary Discourse in the Early Eighteenth-Century Thing Poem’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 40:2 (2007), 196.

- Peter Betjeman, ‘Craft and the Limits of Skill: Handicraft Revivalism and the Problem of Technique’, Journal of Design History, 21:2 (2008), 189.

- Benedict, ‘Encounters with the Object’, 198.

- Wall, ‘The English Auction’, 14.

- Caroline Dakers, A Genius for Money: Business, Art and the Morrisons (New Haven and London, 2011), 170.

- See Lots 769 and 769a in Antique and Modern English and Continental Furniture, 1920 October 26 – November 3 (London, 1920).

- Many thanks to Caroline Dakers for her help in ascertaining this.

- Jan Sibthorpe, ‘Sezincote, Gloucestershire’, East India Company at Home (May 2014), 8. http://blogs.ucl.ac.uk/eicah/files/2013/06/Sezincote-PDF-Final-19.08.14.pdf; Ellen Filor and Jan Sibthorpe, ‘Outside the Public: The Histories of Sezincote and Prestonfield in Private Hands’, in Margot Finn and Kate Smith, (eds), New Paths to Public Histories (London, 2015), 103.

- Sibthorpe, ‘Sezincote’, 28.

- A connection further highlighted in material terms by Sezincote’s current owners, the Peake family. Sibthorpe, ‘Sezincote’, 29; Filor and Sibthorpe, ‘Outside the Public’, 105–106.

- In contrast to Bernard Porter’s argument that the impact of empire was neither broad nor deep. See Bernard Porter, The absent-minded Imperialists: Empire, Society, and Culture in Britain (Oxford, 2004), xv.

Chapter 3 (68-87) from The East India Company at Home, 1757-1857, edited by Margot Finn and Kate Smith (UCL Press, 02.15.2018), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.