These tales recur in the myths and legends of many Indo-European cultures.

By Dr. Stephen A. Mitchell

Robert S. and Ilse Friend Professor of Scandinavian and Folklore

Chair, Folklore & Mythology

Harvard University

Medieval Nordic vernaculars routinely use the terms dreki (pl. drekar), ‘dragon’, and ormr (pl. ormar), both ‘serpent’ and ‘dragon’, in often overlapping ways, although clearly dreki, a word of foreign origin (< Latin draco, from Greek drakōn) has the more restricted range, never referring to snakes as such, but always, and only, to the kind of serpentine beasts known from myth and legend.1 By contrast, ormr, cognate with Old English wyrm ‘snake,’ ‘dragon’ and so on, is employed to mean both the actual reptiles of the suborder Ophidia and cryptozoological monsters. So intertwined are the two in medieval texts and in artistic representations that one scholar has suggested the Swedish neologism drakorm (pl. drakormar) as a means of referring to the two as a group.2

In surviving texts concerned with Old Norse mythological and legendary traditions, modern readers encounter three especially well-known dragons: Níðhǫggr, the Miðgarðsormr, and Fáfnir. There are other named dragons and other terms, of course, as Snorri remarks in his Skáldskaparmál:

Þessi eru orma heiti: dreki, Fáfnir, Jǫrmungandr, naðr, Níðhǫggr, linnr, naðra, Góinn, Móinn, Grafvitnir, Grábákr, Ófnir, Sváfnir, grímr.3

These are the names for serpents: dragon, Fafnir, Iormungand, adder [naðr], Nidhogg, viper [naðra],4 Goin, Moin, Grafvitnir, Grabak, Ofnir, Svafnir, masked one.5

What these legendary drakormar of Norse tradition have in com-mon with the well-known dragons of Christian tradition, such as those that do combat with Christian heroes such as Saint George, is that they are typically seen to have negative associations, that is, generally negative and adversarial relations with human society: according to Vǫluspá in GKS 2365 4to, Níðhǫggr, for example, inn dimmi / dreki fljúgandi (‘the dark dragon flying’) bears corpses í fjǫðrom (lit., in [his] feathers’; Vǫluspá (K) st. 63 cf. Vǫluspá (H) st. 58) and is said in Grímnismál (st. 35) and Gylfaginning to gnaw (skerðir) at the roots of the World Tree.

This adversarial “man versus monster” scenario, the central image of the various story lines gathered as motifs A876, A1082.3 and so on in The Motif-Index of Folk-Literature,6 is one that has ancient roots: not only the North Germanic peoples but also many other Indo-European cultures – i.e., Italic, Indo-Iranian, Celtic, Greek, Anatolian and other historically- and linguistically-related traditions – were, according to Calvert Watkins’ How to Kill a Dragon: Aspects of Indo-European Poetics,7 inheritors of a millennia-old formula of the following sort:

(HERO) SLAY (*guhen-) SERPENT (WITH WEAPON; alt., WITH COMPANION)

It is, of course, a tale that recurs in the myths and legends of many Indo-European cultures, for example, in the storied confrontations between Zeus and Typhon, Herakles and the Hydra, Perseus and the Gorgon, Indra and Vṛtra, and, in the Nordic case, Þórr and the Miðgarðsormr.

Given this well-documented archaic story pattern and such popular Christian presentations of dragons in the Nordic Middle Ages as the legend of Saint George, it seems that the principal way these beasts ought to be understood is within an adversarial context; however, several scholars have been at pains to argue for a different perspective on pre-Christian perceptions, and uses, of dragons. Basing his interpretation on close examination of Bronze Age rock art and images on bronze objects, Flemming Kaul has proposed an integrated understanding of what he has termed the religion of “the solar age” (solalderen).8 According to Kaul’s anal-ysis, this is a belief system connected to a social elite exercising control of, and trade in, bronze.9 In it, the drakorm provides assistance to the sun in its daily movement by leading it below the horizon for its nocturnal aqueous passage.10

On the significance of such an understanding of Bronze Age religion in the North for the Germanic Iron Age many centuries later, Kaul thinks such continuity unlikely, mainly due to what he understands to be two periods of disruption: one c. 500 BC with a change in ritual patterns, and another, c. 500 AD, with the establishment of a religion centered on the Æsir. But, even if he thinks the possibility slight of there being any meaningful comprehensive connections between the Bronze Age materials and, for exam-ple, later written sources, Kaul concedes that some of the earlier motifs, including the snake motif, may have been transformed in ways that allowed them to survive into the Iron Age.11

Birgitta Johansen, also an archaeologist, concludes as well that there may have been generally positive relationships of drakormar to human society. Treating the Roman Iron Age up through the Middle Ages (200 CE –1400 CE), Johansen examines the evolution of social and mental constructs, especially as these are to be inferred from the natural and built landscapes (e.g. hill forts, stone walls), and their interrelationships. Johansen’s interpretation relies heavily on what she sees as the contrasting views of pagan vs Christian Scandinavia, especially as these perspectives are employed in dragon imagery on rune stones.12 Johansen argues that the previously positive connection between drakormar and women turns negative under Christianity’s influence:

My conclusion is that women are the users of the dragon (even explicitly against men) and that the dragon protects women. The dragon fights with men and it kills men. These roles eventu-ally changed, the dragon increasingly becoming a threat to men and something men could control only by killing. In addition it became, during the Middle Ages and under Christian influence, a deadly threat to women too.13

Thus, against the view that human relations to drakormar were necessarily negative, as in so many Indo-European sources and such Old Norse narratives as those about Þórr and the Miðgarðsormr, an alternative, positive interpretation also emerges for the pre-Christian era. Recognizing the possibility then that there may have existed two distinctly different interpretations of drakormar in the Iron Age, how might our understanding of the drakorm figure as seen in Gotland be re-interpreted?

Drakorm elements figure strongly in the island’s art tradition, and a number of Gotlandic picture stones provide important clues about the drakorm’s status. Frequently, these images come from the earliest era of the Gotlandic picture stones,14 a turning point in the history of religious and cultural life in northern Europe.

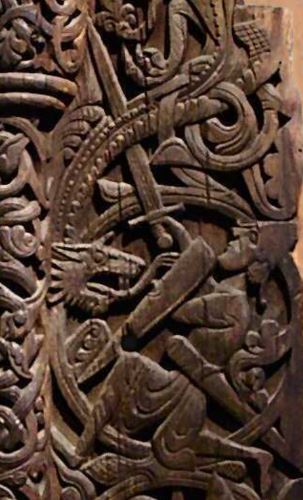

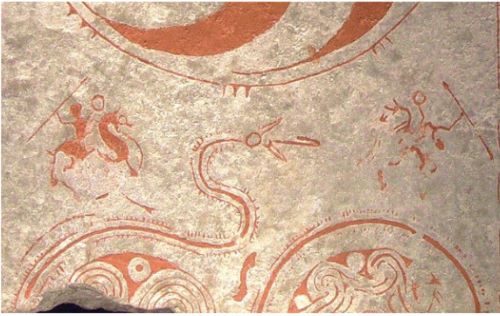

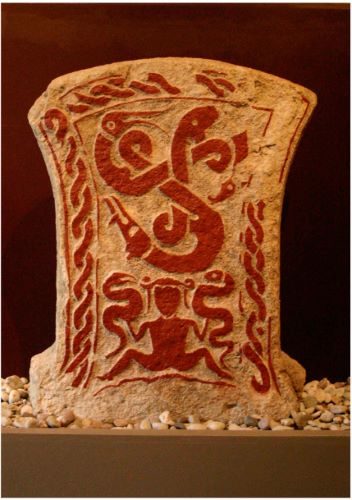

From the earliest periods, Lindqvist’s group Aa, now understood to include the 2nd through the 6th centuries,15 such drakorm images as Martebo Church (G 264) (Fig. 1) and Hangvars Austers I, for example, testify to the popularity of the dragon-snake motif within the island’s art traditions. For the most part, these depictions appear to fall well within the adversarial dragon tradition.16 A related, but much more complex and divergent, use of drakormar is also one of the best-known Gotlandic picture stones to the world at large, namely, the remarkable monument from Smiss in När Parish, discovered in 1955, sometimes called the “snake witch stone” (Swedish ormhäxan, alt., ormtjuserskan).17

När Smiss III (Fig. 2) is usually dated to the 6th to 7th centuries (although some have suggested that it might be from as early as the 5th century).18 In it, rather than the dominating central whirling solar figures on Martebo Church (G 264) and Hangvars Austers I, När Smiss III has instead a large triskele of three animals, often interpreted as a boar, a raptor, and a drakorm. Beneath this group is the figure of a human, generally, although not always, believed to be a woman, legs outstretched, holding two differing drakormar, one in either hand.

Interpretations of this stone’s origins, history and meaning have been much discussed, although little agreed on – already its discoverer, Sune Lindqvist, brought not only Norse but also Celtic and Minoan traditions into the debate and these possibilities have tended to dominate discussion ever since. The stone has, for example, been understood to be a product of Celtic artisanship representing Daniel in the lion’s den;19 others have also promoted possible Celtic connections, especially to the degree to which the image has been likened to the god, Cernunnos, as presented on the Gundestrup Cauldron.20 Karl Hauk sees in the figure a shape-shifted Óðinn in the form of a Seelenführer.21 And comparisons with the famous Minoan snake goddess figurines from the “houses of the double-axe” in Knossos and other Cretan towns are highly suggestive but of uncertain value given our current state of knowledge. The very uniqueness of this stone among Gotlandic picture stones makes the object difficult to assess, although one need not be quite so pessimistic as the Harrisons, who include the stone in their 101 föremål ur Sveriges historia noting simply that “we haven’t a clue about what the stone says”.22

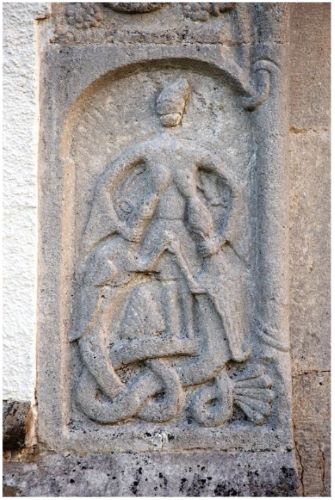

By contrast, local historians and other enthusiasts have been neither silent nor uncertain about this remarkable stone, and we may, in fact, be able to provide a context which at the very least situates När Smiss III within an empirically-based matrix, such that it no longer seems so utterly sui generis. Of particular interest, despite being half a millennium later than När Smiss III, has been a 12th-century stone relief at Väte Church, Gotland (above).

It has sometimes been suggested that such scenes are legacies of a pre-Christian belief in Terra mater, the earthmother, nursing beasts, including serpents. Another, and in my opinion likelier, interpretation is that it reflects an interest in such vision literature as e.g. the 4th-century Vision of Saint Paul, the 5th-century Apocalypse of Elijah, or the (contemporary) 12th-century Vision of Alberic, all of which present women condemned to nurse serpents in Purgatory/Hell, because they have refused to care for orphans, or, in other instances, their own children. And in Continental church art, these unusual scenes of multispecied nursing are understood to be a punishment for lust and debauchery, an idea occasionally applied to Väte as well;24 moreover, similar scenes are also found in medieval homiletic literature, which again point to envy and lust as the causes of this unusual suckling.25 Recent arguments have pushed back against this ecclesiastical interpretation and contended anew that it is, in fact, Terra mater and not Luxuria that is being presented here and elsewhere in Nordic contexts.26

Importantly, one of the other sites comes from the church at Linde on Gotland, part of a baptismal font described as showing “a standing woman with a ‘snake’ [orm] at one breast”.27 Naturally, the origin of the medieval drakorm-nursing images at Väte and Linde are most easily explained by these ecclesiastical references – yet whatever the Church’s specifically theological rationale, nothing about this scene dictates that islanders who knew of a traditional association of women and drakormar could not interpret it in ways that were convivial to local beliefs and customs, an association that could, in fact, have played a role in the Church’s selection of this theme. The two images at Väte and Linde are hardly a large dataset and one might reasonably conclude that these unusual human-drakormar interactions are merely examples of the so-called “infinite monkey theorem”. Yet, as already strongly hinted at in Peel’s edition and translation of medieval Gotlandic law and legend,28 there are, in fact, several other significant indications of a local tradition involving drakormar.

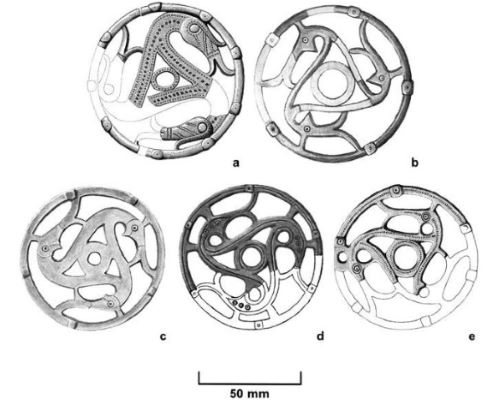

Although the human figure on the lower portion of När Smiss III is unique on Gotland, the triskele design on the upper portion is not. In fact, in reviewing the archaeological record from the period 550–750 CE,29 it is clear that designs similar to the När Smiss III triskele are a common feature of Gotlandic iconography throughout these pre-Viking periods, as in the following examples of perforated discs.30

The design of these artifacts, of which there are a great many from Gotland, strongly resembles the triskele on När Smiss III (although it shows three different animals), especially when it is presented in a similar style (Fig. 5).

One particularly interesting item in this inventory (item c in Fig. 4), as noted already in Peel,31 comes from an early 9th-century Gotlandic grave for a woman at Ihre in Hellvi Parish in northeastern Gotland. Although the grave itself dates to the 9th century,32 it has been argued that the object may date to the period 650–700 CE.33 One possible interpretation of this chronology would be that the disc, as a noted archaeologist suggests “might have been an antique when it was buried and this raises the possibility of such decorative discs having been heirlooms passed from mother to daughter”.34

The continuity of these ornamental discs, their style, and their concern with drakormar brings to mind, as is occasionally mentioned on online sites about Gotland, that also concerned with women and serpents is an important episode in the so-called Legendary History of Gotland from the 13th century:

Þissi Þieluar hafþi ann sun, sum hit Hafþi. En Hafþa kuna hit

Huitastierna. Þaun tu bygþu fyrsti a Gutlandi. Fyrstu nat, sum

þaun saman suafu, þa droymdi henni draumbr, so sum þrir ormar

varin slungnir saman i barmi hennar, ok þytti henni sum

þair skriþin yr barmi hennar. Þinna draum segþi han firir

*Hafþa, bonda sinum. Hann *reþ draum þinna so:

‘Alt ir baugum bundit.

Boland al þitta varþa,

ok faum þria syni aiga.’35

This same Þieluar had a son named Hafþi, and Hafþi’s wife was called Huitastierna. These two were the first to settle in Gotland. The first night that they slept together, she dreamed a dream. It was just as if three snakes were coiled together within her womb, and it seemed to her as though they crawled out of her [womb]36. She related this dream to Hafþi, her husband, and he interpreted it as follows:

‘Everything in rings is bound.

Inhabited this land shall be;

we shall beget sons three.’

This legendary text as a whole has been the subject of much discussion over the decades,37 and although its immediate context – the Laws of Gotland – suggests that it largely functioned as a framing device for these important documents, few doubt that much of the material in the history offers us insights into the early history and traditions of the island.38 The opening settlement or foundation legend, for example, has numerous parallels, including the three brothers, but virtually without parallel is the notion of Huitastierna dreaming of having three snakes coiled in her womb who are subsequently born and who, as humans, settle the island.

A somewhat similar tale is the dream reported about Clytemnestra in the second of Aeschylus’ Oresteia trilogy, Choephoroi (The Libation Bearers), according to which Clytemnestra has given birth to a monstrous and vengeful snake. But even if the basic idea – an elite woman giving birth to one or more snakes – is the same, it is in one instance meant to be a real snake and in the other a dream to be interpreted, like the cows and corn that Jacob reveals to pharaoh (Genesis 40–41); moreover, the consequences of the dreams are quite different.39 On the other hand, the association of snakes with birthing can boast many parallels: the resemblance of entwined snakes to the umbilical cord, a perception that leads to the connection, and perhaps even metonymy, of this funiculus and snakes, is a phenomenon well-documented in a variety of ancient and modern cultures.40 Moreover, the skin-shedding or sloughing (edysis) of snakes has led to the association of these animals with concepts of re-birth in e.g. ancient Egyptian and Mesoamerican cultures.

The occasional attempts to link this episode of the Legendary History to När Smiss III might easily be dismissed as an exuberant exercise in local pride, yet viewed in the context of the decorative disc from Ihre and the other Gotlandic drakorm triskeles that suggest a long-standing preoccupation with these motifs, it is worth noting that that keen native observer of Gotlandic history and culture, Hans Nielsön Strelow (1580s–1656), makes much of the continued popular importance in his day of Huitastierna and her role in creating the identity of the island, concluding by saying that “The Gotlanders ascribe much to her” (Hende tilskrifuer Guthilenderne megit).41

Two further data points can be added to this puzzle, one from the Danish “solar age”, the other broadly contemporary with the Iron Age materials from Gotland. The Bronze Age votive offering from Fårdal in Jutland – the most impressive of several Bronze Age scenes Kaul sees as representing humans, snakes and drinking/suckling – consists of some five bronze pieces (Fig. 6), among them, a kneeling woman and a serpentine beast.

In his interpretation, Kaul argues that the woman is turning toward the snake, “and with her hand she is holding her breast, presenting her breast to the snake, as if inviting it to drink”;42 moreover, he suggests that the hole made by the woman’s closed hand and the hole in the head of the serpent indicate that the two had been connected with a line.

Furthermore, recent research by Sigmund Oehrl on Gotlandic picture stones using RTI technology, and presented at the 2015 Stockholm Mythology Conference, considerably strengthens the possible correctness of the argument here. The advanced techniques offered by RTI have led Oerhl to an entirely different understanding of the depiction usually described as being of Gunnar in the snake pit on the Klinte Hunninge I picture stone. This monument was assigned by Lindqvist to the 8th century; current research places its group to the late 8th to 10th centuries.43 The newly revealed tableau, especially in light of the current discussion, looks like nothing quite so much as a birthing scene – a recumbent woman,44 assisted by one, perhaps two, midwives, and accompanied by drakormar. To this, one might add Kaul’s understanding that snakes in his reconstructed Bronze Age religion assisted the sun’s transition between worlds – perhaps this function has translated over time into drakormar helping the child’s transition into the world during childbirth.

Is it possible then that we see in these Iron Age materials the echoes of a tradition with deep roots involving women, drakormar, and parturition, a tradition which, at least by the time of our medieval text, has become the “myth” of Huitastierna’s vision of ormar and the origin of the island’s population – and also a tradition the Church appropriated to its own ends at Väte and Linde, returning closely, visually at least, to Kaul’s lactating Fårdal figurine? That is a long leap, I realize, and, if anything, we should view such a scheme with healthy skepticism, but such an evolution would both explain our data and conform to them. Certainly, I do not insist on such an interpretation, yet I hope by focusing on the Gotlandic materials we now have a better purchase on how drakormar may have played a role in the lived lives of Gotlanders in the Merovingian Period and later.

Appendix

Endnotes

- The subject of medieval Nordic dragons has attracted considerable attention in recent years (e.g., Johansen 1997; Lionarons 1998; Evans 2005; Ármann Jakobsson 2010; Cutrer 2012; Acker 2013; and Mitchell).

- Johansen 1997. In sympathetic appreciation of the conundrum addressed by this term, I adopt its use here.

- Skáldskaparmál, Faulkes 1998:90.

- The terms translated as ‘adder’ and ‘viper’ – nadr and nadra – would seem to be most simply understood as the gendered male and female counterparts of the same animal, as both Cleasby-Vigfusson 1982 and Zoëga 1975 treat the terms, yet as an indication of the complexity associated with this category of beast, although Fritzner 1973 accepts nadra as a poisonous snake (vipera), he suggests that nadr might indicate some sort of lizard-like creature (firben, øgle). Ordbog over det norrøne prosasprog notes some 18 instances of nadra but for nadr, only the current citation in Snorra edda and as a sword name in Egils saga Skalla-Grímssonar. On drakorm names and swords, cf. Skáldskaparmál, Faulkes 1998, st. 451, 459.

- Skáldskaparmál, Faulkes 1998:137.

- Thompson 1966.

- Watkins 1995.

- Kaul 2004a:408–409. Cp. Nordberg 2013:232, “Kauls solara tolkningar har fått stort genomslag i de senaste decenniernas arkeologiska forskning om bronsålderns religion. Idéhistoriskt sett utgör hans studier en av de senaste länkarna i den solmytologiska skola som har sitt egentliga ursprung i romantikens idévärld, 1800-talets theologia naturalis, den evolutionistiska religionsforskningen och Max Müllers komparativa mytologi.”

- See Kaul 2004a:369–406.

- Cp. Kaul’s observation (1998:263), “On the other hand, the possibility cannot be excluded that the snake can have played a role in the morning.” I note too that Kaul typically uses the term “snake” (slange) in his writings.

- Kaul 1998:11–16, 221–41.

- Johansen 1997:63–107.

- Johansen 1997:253–54.

- Cf. Karnell 2012:10–21.

- Cf. Karnell 2012:14–15.

- Cf. e.g. Andrén 2014:136–38 et passim.

- Regarding this stone, see the detailed information in Guta saga,Peel 2015:283–284.

- Recently, Pearl (2014:137) concludes that it belongs to “an artistic tradition that should be dated conservatively from the beginning of the 5th century AD to the middle of the 7th century AD.”

- Arrhenius & Holmquist 1960.

- See Hermodsson 2000.

- Hauk 1983:556.

- “Vår något nedslående slutsats blir alltså att vi inte har en aning om vad bildstenen berättar” (Harrison Lindberg & Harrison 2013:64).

- http://www.europeana.eu/portal/record/91622/raa_kmb_ 16001000197924.html. Accessed 9 January 2016. Accessed 9 January 2016.

- On the motif of the femme-aux-serpents, especially in medieval church art, see Luyster 2001. I take this opportunity to thank Sara Burdorff for pointing this important connection out to me.

- From Tubach 1969: #4281 An empress, envious of another who has greater prestige than she, makes her put two snakes at her breasts. #4888 A woman bears two sons in adultery; her first son, a hermit, has a vision of his mother in which she has two toads at her breasts and a snake about her head.

- Ohlson 1995, who provides a survey of parallels from, e.g. three Scanian baptismal fonts (63–64). Cf. Herjulfsdotter & Andersson 2012, who suggest additional sites, as well Mackeprang (1941:10 et passim) on the remarkable baptismal font from Vester Egede, Denmark.

- Ohlson 1995:63, “en stående kvinna med en orm vid ena bröstet.” Cp. Lagerlöf 1981:81, and, especially, the image and detailed description in Stenstöm 1975:109–10.

- Guta saga, Peel 1999:19–20; Guta saga, Peel 2015:283–84.

- As reported in e.g. Nerman 1917–1924 and Nerman et al. 1969–1975.

- Cf. Nerman et al. 1969–1975, II, Table 174, Nr. 1451 and III:31, “St. u. Lilla Ihre, Ksp. Hellvi. St. 20550: Grab 159.”

- Guta saga, Peel 1999:19–20.

- Nerman 1969–1975.

- “A small disc with a pierced decoration, about two and a half inches in diameter, was found in a woman’s grave at Ihre in Hellvi parish, northeastern Gotland, and seems to depict three intertwined serpents. The grave is dated, on the basis of other finds within it, to the beginning of the ninth century” (Guta saga, Peel 2015:283).

- Quoted in Guta saga, Peel 2015:283–284.

- Peel 1999:2–3.

- ‘Womb’ (in square brackets) modifies Peel’s translation slightly in order to indicate that Old Gutnish barmbr (dative barmi) is used in both instances in the original as the site within which the “snakes” apparently gestate and out of which they ‘crawl’ (skriþa).

- Cf. Mitchell 1984; Guta saga, Peel 1999; 2015; and Pearl 2015.

- Cf. Mitchell 2014; Guta saga, Peel 2015.

- There are, of course, other tales involving kindred beasts, such as the Tóruigheacht Dhiarmada agus Ghráinne ‘Pursuit of Diarmaid and Gráinne’ of the Irish Fenian cycle. On it, Persian and Nordic parallels, see Nagy 2017.

- E.g. Herskovits & Herskovits 1938 II:248.

- Strelow 1633:16.

- Kaul 2004b:36; cf. 2004a:328–330.

- Karnell 2012:14–15.

- The character of birthing in the Germanic Iron Age is unknown: images from the Classical world often show the parturient seated, but some authorities (e.g. Soranus, Gynecology) also mention lying down. Likewise, in the Eddic poem Oddrúnargrátr, several positions are noted, with the maid saying initially (st. 4), Hér liggr Borgný, of borin verkiom (“Here lies Borgny, overcome with labour pains”). For other Old Norse examples, see Gotfredsen 1982.

Bibliography

- Acker, Paul. 2013. Dragons in the Eddas and in Early Nordic Art. In P. Acker & C. Larrington (eds.). Revisiting the Poetic Edda. Essays on Old Norse Heroic Legend. New York: Routledge, 53–75.

- Andrén, Anders. 2014. Tracing Old Norse Cosmology. The World Tree, Middle Earth, and the Sun from Archaeological Perspectives. Vägar till Midgård, 16. Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

- Ármann Jakobsson. 2010. Enter the Dragon. Legendary Saga Courage and the Birth of the Hero. In M. Arnold & A. Finlay (eds.). Making History. Essays in Fornaldarsögur. London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 33–52.

- Cleasby, Richard and Gudbrand Vigfusson (eds.). 1982 (1957). An Icelandic-English Dictionary. Second rev. ed. by William Craigie. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Cutrer, Robert. 2012. The Wilderness of Dragons. The Reception of Dragons in Thirteenth century Iceland. M.A. thesis, Háskóli Íslands.

- Evans, Jonathan. 2005. ‘As Rare as They are Dire’. Old Norse Dragons, Beowulf, and the Deutsche Mythologie. In T. A. Shippey (ed.). The Shadow-Walkers. Jacob Grimm’s Mythology of the Monstrous. Arizona Studies in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, 14. Tempe, Arizona: Arizona CMRS (with Brepols), 207–269.

- Fritzner, Johan (ed.). 1973 (1886). Ordbok over Det gamle norske Sprog. 4th rev. ed. Oslo, etc.: Universitetsforlaget.

- Gotfredsen, Edvard. 1982 (1956–1978). Barsel. In J. Brøndsted et al. (eds.). Kulturhistorisk leksikon for nordisk middelalder. Copenhagen: Rosenkilde og Bagger: I, cols. 354–365.

- Gräslund, Anne-Sofie. 2006. Wolves, Serpents and Birds. Their Symbolic Meaning in Old Norse Belief. In A. Andrén et al. (eds.). Old Norse Religion in Long-Term Perspective. Origins, Changes, and Interactions. Vägar till Midgård. Lund: Nordic Academic Press, 124–129.

- Harrison Lindbergh, Katarina, & Harrison, Dick. 2013. 101 föremål ur Sveriges historia. Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Hauk, Karl. 1983. Text und Bild in einer oralen Kultur. Antworten auf die zeugniskritische Frage nach der Erreichbarkeit mündlicher Überlieferung im frühen Mittelalter. Zur Ikonologie der Goldbrakteaten XXV. In Frühmittelalterliche Studien 17, 510–599.

- Herjulfsdotter, Ritwa, & Andersson, Tommy. 2012. Luxuria eller Terra på relieferna i Siene och Strö? In Skara stiftshistoriska sällskap. Medlemsblad 20:1, 8–10.

- Hermodsson, Lars. 2000. En invandrad gud? Kring en märklig got-ländsk bildsten. In Fornvännen 95, 109–118.

- Herskovits, Melville J. & Herskovits, Frances S. 1938. Dahomey. An Ancient West African Kingdom. New York: J.J. Augustin.

- Johansen, Birgitta. 1997. Ormalur. Aspekter av tillvaro och landskap. Stockholm Studies in Archeology, 14. Stockholm: Arkeologiska institutionen. Stockholms universitet.

- Karnell, Maria Herlin (ed.). 2012. Gotlands bildstenar. järnålderns gåtfulla budbärare. Gotländskt arkiv, 84. Visby: Fornsalens Förlag.

- Kaul, Flemming. 1998. Ships on Bronzes. A Study in Bronze Age Religion and Iconography. Studies in Archaeology & History, 3. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

- Kaul, Flemming. 2004a. Bronzealderens religion. Studier af den nordiske bronzealders ikonografi. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab.

- Kaul, Flemming. 2004b. Bronzealderens religion. Studier af den nordiske bronzealders ikonografi. Dansk resumé. English Summary. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Nordiske Oldskriftselskab.

- Lagerlöf, Erland. 1981. Linde kyrka (Fardhems ting, Gotland, VII:2). Sveriges kyrkor, konsthistoriskt inventarium, 186. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Lionarons, Joyce Tally. 1998. The Medieval Dragon. The Nature of the Beast in Germanic Literature. Enfield Lock, Middlesex: Hisarlik Press.

- Luyster, Amanda. 2001. The Femme-aux-serpents at Moissac. Luxuria (lust) or a Bad Mother? In S.R. Asirvatham et al. (eds.). Between Magic and Religion. Interdisciplinary Studies in Ancient Mediterranean Religion and Society. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 165–191.

- Mackeprang, Mouritz. 1941. Danmarks middelalderlige Døbefonte. Copenhagen: Selskabet til Udgivelse af Skrifter om Danske Mindesmærker.

- Mitchell, Stephen A. 1984. On the Composition and Function of Gutasaga. In Arkiv för nordisk filologi 99, 151–174.

- Mitchell, Stephen. 2014. The Mythologized Past. Memory and Politics in Medieval Gotland. In P. Hermann et al. (eds.). Minni and Muninn. Memory in Medieval Nordic Culture. Acta Scandinavica, 4. Turnhout: Brepols, 155–174.

- Mitchell, Stephen. Dragons, a Cryptozoological Journey into the Nordic Otherworld. In J.F. Nagy (ed.). Comparing Dragons. Ancient, Medieval, and Modern. UCLA CMRS. Mundi. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Nagy, Joseph Falaky. 2017. Vermin Gone Bad in Medieval Scandinavian, Persian, and Irish Traditions. In P. Hermann et al. (eds.). Old Norse Mythology in Comparative Perspectives. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Nerman, Birger. 1917–1924. Gravfynden på Gotland under tiden 550–800 e. K. In Antikvarisk Tidskrift för Sverige 22:4, 1–102, I–XXX.

- Nerman, Birger et al. 1969–1975. Die Vendelzeit Gotlands. Monographien hg. von der Kungl. Vitterhets, historie och antikvitets akademien, 48, 55. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Nordberg, Andreas. 2013. Fornnordisk religionsforskning mellan teori och empiri. Kulten av anfäder, solen och vegetationsandar i ide-historisk belysning. Acta Academiae Regiae Gustavi Adolphi, 126. Uppsala: Kungl. Gustav Adolfs Akademien för svensk folkkultur.

- Oehrl, Sigmund. 2012. Ikonografiska tolkningar av gotländska bildstenar baserade på nya analyser av ytorna. In M. H. Karnell (ed.). Gotlands bildstenar. Järnålderns gåtfulla budbärare. Gotländskt arkiv, 84. Visby: Fornsalens Förlag, 91–106.

- Oehrl, Sigmund. 2017. Re-Interpretations of Gotlandic Picture Stones Based on the Reflectance Transformation Imaging Method (RTI). Some Examples. In K. af Edholm et al. (eds.). Myth, Materiality, and Lived Religion in Merovingian and Viking Scandinavia. Stockholm: Stockholm University Press.

- Ohlson, Elisabeth. 1995. Själajakt och fruktbarhetssymbolik. Romanska reliefer på de gotiska kyrkorna i Grötlingbo och Väte. In Gotländskt arkiv 66, 49–66.

- Pearl, Frederic B. 2014. The Water Dragon and the Snake Witch. Two Vendel Period Picture Stones from Gotland, Sweden. In Current Swedish Archaeology 22, 137–156.

- Peel, Christine. 1999. Guta saga. The History of the Gotlanders. Ed. and transl. Christine Peel. Viking Society for Northern Research. Text Series, 12. London: Viking Society for Northern Research.

- Peel, Christine. 2015. Guta Lag and Guta Saga. The Law and History of the Gotlanders. Ed. and transl. Christine Peel. Medieval Nordic Laws. New York: Routledge.

- Stenstöm, Tore. 1975. Problem rörande Gotlands medeltida dopfuntar. PhD Diss. Umeå: Umeå Universitet.

- Thompson, Stith (ed.). 1966. Motif-Index of Folk-Literature. Second rev. ed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Tubach, Frederic C. 1969. Index Exemplorum. A Handbook of Medieval Religious Tales. Folklore Fellows Communications, 204. Helsinki: Akademia Scientiarum Fennica.

- Watkins, Calvert. 1995. How to Kill a Dragon. Aspects of Indo-European Poetics. New York: Oxford University Press.

Contribution (115-134) from Myth, Materiality, and Lived Religion: In Merovingian and Viking Scandinavia, edited by Klas Wikström af Edholm, Peter Jackson Rova, Andreas Nordberg, Olof Sundqvist, and Torun Zachrisson (2019, Stockholm University Press), published by OAPEN under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.