Examining medieval Viking amulets believed to have the power to fight and cure illness.

By Dr. Rudolf Simek

Professor and Chair of Ancient German and Nordic Studies

University of Bonn

It is a well-known fact within Medieval studies that in Western Europe in the Middle Ages there existed, side by side, three major strategies of coming to terms with illnesses.

Firstly, what we today would consider proper medical therapy, in its many variants from traditional monastic medicine (by the infirmarii) to itinerant barber surgeons (medici) to academic medical science (phisici) as practised within and without the Salernitan school. Medical handbooks in manuscript form, containing collections of active ingredients (simplicia) and prescriptions for particular ailments (indicationes) as well as rules on dietetics and prognostics testify to this tradition even in Old Norse vernacular texts.

Secondly, by taking recourse to miraculous divine help, usually in the form of asking the saints for intercession on the behalf of the patient or his kin, whether by prayer alone or the promise of votive gifts, resulting in the miraculous recovery of the patient – at least in the many successful cases reported and handed down in hagiographic literature, usually in the miracle collections tied to the lives of particular saints, certainly not as case histories on the recovery of particular patients and even less connected with particular illnesses – unless the saint in question was known to “specialise” in certain medical problems, such as St. Margaret for difficult births and St. Blaise for throat illnesses, to name but two of many.

Thirdly, by taking resort to religio-magical practises, such as magical charms, amulets, and rituals. Although all of these were expressly condemned not only in the ecclesiastical writings of the missionary period – which considered them to be remnants of the heathen past – but also in penitential handbooks throughout the Middle Ages. Many of these practises may indeed have their roots in the pagan pre-Christian Germanic religion, but there is also much interference from much older Mediterranean and Near Eastern magical methods, that merged into what we now term typical Medieval Popular Religion.

The present paper only concerns itself with the third method of fighting illnesses, and within this group only with apotropaic measures to be found on amulets (ligamina, ligamenta, obligamenta, ligaturae).

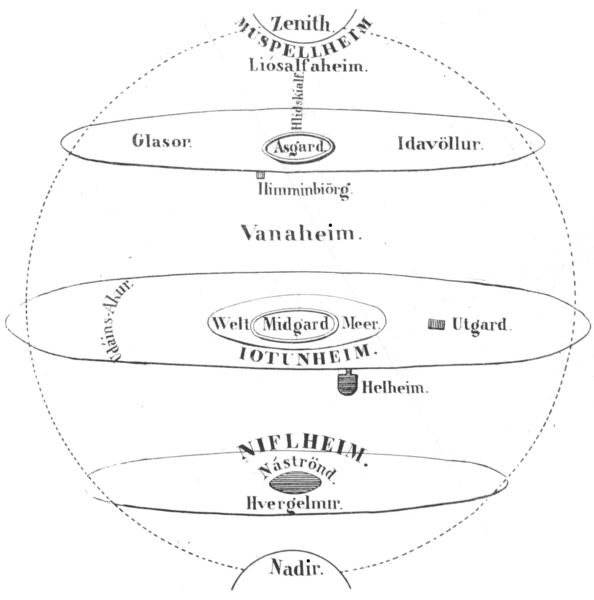

When, in previous papers,1 I was trying to work out what role the álfar had in the Scandinavian medieval popular religion (– who were occasionally, but rarely seen as having medical powers in the Icelandic sagas),2 and had to come to the conclusion that by the 11th–14th centuries, álfar (called elvos, elvas or similar in their Latinized form) were considered demons of illness, and the charms which preserve such identifications are found on lead amulets meant to conjure and thus avert the doings of these demons, thus removing the source of the illness. This throws light on an instance in Kormáks saga: the magical practise suggested here by an old witch thus did not attempt to call on the álfar/demons to heal the person in question, but rather tempt/bribe the demons to remove themselves as being the source of the illness. In this particular instance, the passage implies that: álfar are subterranean, that they live in (grave?)-mounds and have supernatural powers related to illnesses and that they can be influenced through rituals / magic practices.

But this is the only text I know of this particular type, although there may be others in hagiographic sagas. In other Old Norse sources, especially in Eddic poetry, the álfar were not primarily considered to be demonic at first sight. They are to the largest extent found in alliterative formulae, such in álfar ok æsir, or álfar ok æsir ok vísir vanir, and unless one would like to claim that the demonization of the old Scandinavian gods had progressed quite far at the time of the composition of Eddic poetry, we have to assume that the álfar stood for a mythological race whose exact identification is no longer possible, but was not synonymous with that of the æsir. However, it is not unlikely that they were considered to be con-nected with the world of spirits, and perhaps also directly connected with the dead, but in any case, to be one of the subterranean races.

In the present paper, I am not concerned with the identification and the nature of the álfar, but rather with the connection of álfar and other spirits to illnesses in popular religion, and mainly on medieval amulets.

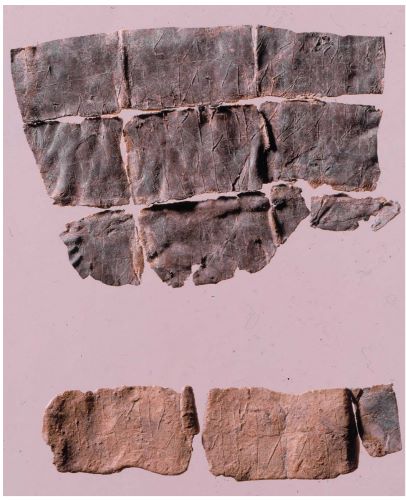

Of these, an increasing number of textual amulets have been found in recent years, most of them made from thin lead sheets, although a few silver and copper ones are known, too.3 Imer4 is able to list 30 amulets with text for Norway, 20 for Sweden and over a 100 for Denmark. In addition to that, a steadily increasing number of amulets are found in Germany, especially in the eastern part of the country.5 As far as I can make out, the majority of Danish amulets are executed in runes, the German ones mainly in Latin or cryptography. To these we may add some 18 Norwegian and two Swedish lead mortuary crosses,6 of which those with text on them seem always to be scratched in runes rather than Roman letters.7 Despite the fact that most of the Danish amulets are either illegible, fragmentary, or cannot be opened without damage to the object, it is noticeably that those with longer texts tend to be executed in Roman letters (the exceptions being the Odense and the Blæsinge amulets), whilst the shorter and/or unintelligible ones are predominantly in runes.

Apart from those amulets which carry an explicitly apotropaic text, conjuring spirits to prevent an illness, the amulets which carry either the full text of the beginning of the gospel according to John,8 such as the Randers amulet,9 or else reference to that Gospel and the very first word of it,10 such as the one from Schleswig, can also be considered to carry apotropaic messages, as is confirmed by the Codex Upsaliensis C 222 from c. 1300, which preserves a conjuration beginning

Jnitium sancti euangelij secundum iohannem. Jn principio erat uer-bum […] hoc erat in principio apud deum etc. Adiuro uos elphos elphorum gordin. ingordin. Cord’i et ingordin. gord’I.11

However, only the Schleswig lead tablet12 seems to combine the Gospel with a conjuration as in the Uppsala manuscript, and I shall not consider the amulets with the beginning of John’s Gospel in the following paper, although the connection between this text and particular ailments has to date not been fully investigated. But, as Steenholt Olesen13 points out correctly:

“In general, the evidence from late medieval medical books makes it clear that specific Latin phrases were used in rituals of protection and for the healing of fevers, eye diseases, boils, and so on.”

Only a small number of Scandinavian Medieval amulets actually contain a direct invocation of spirits, either as álfar or demons,14 but, as this identification is beyond doubt in these cases, the use of the terms elvos, elvas and similar may simply be seen as an attempt to produce the vernacular term for demon in the otherwise Latin texts – perhaps to ensure that the demons which were being conjured understood in any case. Therefore, I shall include all texts concerned with demonic conjurations, whatever term for demons is used, and whether written in Latin letters or (very occasionally) in runes; whichever script is used, the language is Latin throughout, with only a few vernacular words interspersed and several names of mixed, but mainly Latin, Greek, or even Near Eastern provenance. Despite the above-mentioned fact that a majority of lead amulets seems to be written in runes, those relatively few that contain a legible coherent text are predominantly written in Latin. This is a point that needs stressing, because “Lead tablets with Latin inscriptions in roman letters are also known from the Danish area, but unfortunately they have not been systematically registered.”15 Why this is so, and why archaeologists in Scandinavia seem to be more interested in amulets in runic script than those with Roman script one can only guess at. One may also speculate on the reasons why there are more meaningful amulets preserved in Roman script although the total number of runic ones is greater, especially as several of the shorter runic inscriptions do not seem to make sense at all or are even written in pseudo runes.16

Nearly all the amulets with longer texts I have studied not only conjure some supernatural beings, but also specify in some detail how or where the conjuration should protect the person in question, who I would like to call “the patient”, as it can be assumed that these amulets were not issued primarily to healthy persons to protect from all eventualities – the conjurations are somewhat too specific for that – but as a means to (further) protect a sick person from further suffering, if proper medical help had either proven ineffective or else was unavailable. To gain further insight into the methods used for these apotropaic measures I shall firstly look into the types of protection from illnesses named on the amulets and secondly try to ascertain whether there is any relation between the protection requested and the types of demons conjured.

In the current investigation, I have used the following amulets:

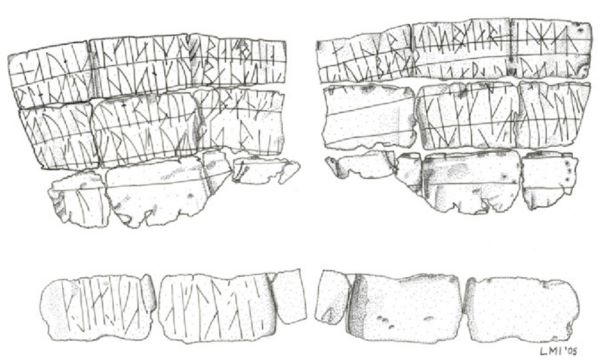

- The lead amulet from Blæsinge (Zealand, Sj 50), dating from any time between the 13th and the 15th century, is executed in Latin in runes and is, with roughly 500 runes, in fact the longest runic inscription found in Denmark to date.

- The lead amulet from Viborg (Jutland, MJy 32), from 1050–1300, with a short Latin text in runes which are difficult to read, but also preserves a type of Latin conjuration or prayer.

- The lead amulet from Romdrup (near Aalborg, Jutland), dating to around 1200, executed in Latin script like all the following texts.

- A newly found and not as yet properly published lead amulet from Møllergarde, Svendborg, also roughly dated to the High Middle Ages, in Latin letters.

- The lead amulet from Schleswig from either the 11th or early 12th century containing the longest of the texts with just under 600 letters.

- The lead amulet cross from Halberstadt (Saxony-Anhalt, Germany, dated to 1142), with a Latin text only fraction-ally shorter than the Schleswig amulet.

Of these, the following amulets name or define the spirits that are conjured: The Blæsinge amulet names them septem sorores … Elffrica (?), Affricea, Soria, Affoca, Affricala, the one from Romdrup eluos uel eluas aut demones, the one from Svendborg apparently more or less the same formula, the long Schleswig amulet the more comprehensive demones sive albes ac omnes pestes omnium infirmitatum and the one from Halberstadt the somewhat different alb(er) qui [u]ocaberis diabolus v(e)l satanas, i.e. the Devil himself.

As all the amulets mentioned are conjurations, and the rest of the texts on them have much in common between them,17 it can be assumed that the terms for the spirits conjured on these amulets were, at least to some extent, interchangeable, so that we have a list of spirits called, in the latinized forms used:

Demones (pl.)

Elvae (pl. f.)

Elves (pl. m.)

Albes (pl. f. and m.?)

Pestes (omnium infirmitatum) (pl., obviously as a personification of pestis “plague”: “you plagues of all illnesses”)

Septem sorores (with five out of seven names)

Alber (sg. m.)

Diabolus (sg. m.)

Satanas (sg. m.)

This array of demons is, not only on the Schleswig amulet, conjured to protect someone from some harm or illness. All of the items I have selected give some indication as to the nature of the protection expected from the conjuration, so that the demons are called upon:

- On the Blæsinge tablet: ut non noceatis istam famulum Dei, neque in oculis, neque in membris, neque in medullis, nec in ullo compagine membrorum eius “that you may not harm this servant of God, neither in the eyes nor in the limbs nor in the marrow nor in any joints of the limbs”.

- On the Schleswig text: ut non noceatis famulo dei neque in die nec in nocte nec in ullis horis “that you may not harm this [male] servant of God by day or by night, nor at any hours”.

- On Romdrup: ut non noceatis huic famulo dei nicholao in oculis nec in capite neque in ulla compagine membrorum “that you may not harm this servant of God, Nicholas, in the eyes nor in the head nor in the joints of his limbs”.

- On Svendborg: ut non noceatis famulam dei Margaretam nec in oculis nec in aliis membris “so that you may not harm this servant of Christ, Margaret, neither in the eyes nor in other limbs [or: other parts of the body]”.

- On the Halberstadt tablet: non habeas potestatem in ista[…] dere aut istum amicum dei TADO. Ne nocere possis non in die neque in nocte non in […] su neque non bibenda neque manducando “so that you have no power over this ….. or this friend of god Tado, so that you cannot harm during the day nor by night nor drinking nor eating nor …”.

- On the both fragmentary and badly executed Viborg amulet we can reconstruct the words: æb omnis febris “from all fevers” from the runic sequence mitius(æ)(o)ni fibri, although there is not enough left of the amulet to discern any conjuration, only an invocation of God, the Holy Spirit and Mary.

Of all these indications as to the nature of the illnesses meant, the most disappointing is the one on the Schleswig amulet, just asking for protection “by day and by night”. However, as the beginning of the conjuration formula is very close to those on the Romdrup and Svendborg amulets, it is possible to infer what the protection was about: Both the latter ones ask for protection of the eyes and the limbs, Romdrup in addition names the head and the joints of the limbs, thus specifying the seat of the illness caused (apparently) by the “demons and elves” called upon by all three texts.

The Halberstadt text is less specific again, but the reference to “day and night” and “eating and drinking” may suggest that the devil called Alber here might have something to do with poising or spoiling of food and drink, but this if of course impossible to prove.

The most interesting information, therefore, is the one on the Blæsinge and the Romdrup texts, where “eyes nor in the limbs nor in the marrow nor in any joints of the limbs” and “in oculis nec in capite neque in ulla compagine membrorum” are referred to, as well as the new Svendborg amulet, which also seems to mention the eyes and the limbs. A quick diagnosis of an illness that causes pains in the eyes, the head, and the joints of the limbs points very much to a febrile infection of the influenza type, according to GPs consulted. But as mentioned before, the only fevers mentioned, namely on the Viborg amulet, we cannot, due to the fragmen-tary state of the piece, associate with any particular spirits. All we know is that it was used to avert fevers.

In order to ascertain which spirits are actually causing which illnesses, this leaves us with the most specific of all the known amulets, namely the Blæsinge one, which conjures the Seven Sisters in order to prevent them from doing harm “in the eyes nor in the limbs nor in the marrow nor in any joints of the limbs.” This is, of course, very similar to the descriptions given on the amulets from Schleswig, Romdrup and Svendborg, but the conjuration of the Seven Sisters opens up an additional line of interpretation.

Although the Seven Sisters are, to my knowledge, not mentioned on any other amulets found to date, they do appear in several medieval manuscripts, which provide further details. Already Düwel18 could refer to Stoklund19 for several invocations calling upon the septem sorores, printed by Franz.20 The most detailed from the Codex Vaticanus Latinus 235 (fol. 44–45; 10th/11th century) reads:

Coniuro uos, frigores et febres – VII sorores sunt – siue meridi-anas, siue nocturnas, siue cotidianas, siue secundarias, siue tercianas, siue quartanas, siue siluanas, siue iudeas, siue hebreas, uel qualicunque genere sitis, adiuro uos per patrem […], ut non habea-tis licentiam nocere huic famulo dei nec in die nec in nocte, nec uigilanti nec dormienti, nec in ullis locis.21

I conjure you, shivers and fevers – who are seven sisters – like the midday ones, the nightly, the daily, the bi-daily, the three-daily, the four-daily, the wood fevers, the Jewish fevers, the Hebrew fevers, or whatever sort you are: I conjure you through the Father […], so that you may not have leave to harm this servant of God by day or night, neither waking nor sleeping, nor in any place.

The long incantation goes on further below:

coniuro uos, de quacunque natione estis, per patrem et filium et spiritum sanctum […] per has omnes inuocationes, coniuro uos, frigores et febres, ut non habeatis ullam licentiam, nocere huic famulo dei N. nec eum fatigare, sed redeatis, unde uenistis, nec potestatem habeatis nec locum in isto famulo dei amen.22

Letter against shivers. In the name of the Father […] I conjure you shivers, seven sisters, the first one called klkb, the other rfst-klkb, the third fbgblkb, the fourth sxbfpgllkb, the fifth frkcb, the sixth kxlkcb, the seventh kgncb: I conjure you, of whatever origin you are, through the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit […] through these invocations I conjure you, shivers and fevers, so that you do not have leave to harm the servant of Christ N. nor torture him, but return to where you came from, so that you have no power nor a place in this servant of God. Amen.

The second version of the invocation uses a cryptographic method to encode the names of the Seven Sisters, but the code used is a very simple one and can easily be deciphered if one replaces every vowel with its preceding letter:23 Ilia, Restilia, Fagalia, Subfogalia (recte: Subfogllia), Frica, Iulia, Ignea (recte: Ignca) in the Vatican text. A Danish formula from the 15th century calls them Illia, Reptilia, Folia, Suffugalia, Affrica, Filica, Loena vel Igne, which gives a very similar result.24 However, as the spelling of the names on the Blæsinge tablet is extremely deviant from any other text, we cannot really supplant the two missing names there, although Iulia and Ignea are the ones most obviously absent.

However, the demonic Seven Sisters are certainly not only known from the Blæsinge amulet and the manuscripts mentioned above, but seem to be far more common in Medieval Europe than that. Several British manuscripts from the later Middle Ages and even Early Modern Times mention their names, and also give some of their uses.

In the British Library manuscript MS Sloane 3853, 143v (16th century), the “septem sorores” are mentioned, but only six names given, namely: “lilia, Restilia, Foca, Affrica, Iulia, Iuliana.” Here, this is called a charm for “expulsion of elves and fairies”, and as such refers only to the conjuration, but not to its purpose. For this period, one may add the manuscript MS. Xd 234 (ca. 1600) from the Folger Shakespeare library, Washington D.C., giving their names as Lilia, hestillia, fata, sola, afrya, Africa, Iulia, and venulla (variant: Venila), which ventures a magic spell to conjure up the Seven Sisters of the Fairies and tie them to you for ever!25

Another, even later magical 17th century manuscript (British Library Sloane 3825) names them as “Lillia, Restilia, Foca, Tolla, Affrica, Julia, Venulla.” As for their function, the similarly magical British Library Manuscript Sloane Ms 1727, 23v (17th century) calls upon them like that:

I conjure you sps. or elphes which be 7 sisters and have these names. Lilia. Restilia, foca, fola, Afryca, Julia, venulia […] that from hensforth neither you nor any other for you have power or rule upon this ground; neither within nor without nor uppon this servant of the liveing god.: N: neither by day nor by night […].26

This wording is, of course, very closely related to both the Schleswig and the Halberstadt texts and shows that such beliefs were still known in Early Modern times, but none mentions any illnesses and none of them is as detailed as the Vatican manuscript mentioned above which must, therefore, remain our main guide. The wording in this manuscript shows that the missing words on the Blaesinge amulet must have referred to those frigores et febres (“shivers and fevers”) mentioned in both versions in this manuscript.

From the detailed description, however, we learn a lot about the seven sisters which does not become clear from the Blæsinge amulet alone: 1. The Seven Sisters are demons for various types of fevers and are individually named, but neither the names nor their numbers bear any direct relationship to the nine types of fevers enumerated in the text. 2. The Seven Sisters are supposedly of different origin (the text says “nation”, which refers to geographical direction rather than ethnicity). 3. The aim of the invocation is twofold, firstly to deprive the sisters of their power to harm and secondly to send them back to where they came from.

The earliest instance of the invocation of the Seven Sisters (as seven fevers) is apparently an eleventh-century charm attributed to Saint Sigismund, the so-called Sigismund charm.27 This refers to King Sigismund of Burgundy, murdered in 523, and early on considered to be useful for invocations against fevers, whether by masses read to call on him or the charm. It is found in a Latin manuscript from Dijon, Bibliotheque municipiale 448, fol. 181r28 fol, addressing them as follows: “I conjure you, O fevers, you are seven sisters”, followed by their names Lilia, Restilia, Fugalia, Suffoca, Affrica, Julia, Macha.29

Although the names of the Seven Sisters are far from stable in the transmission, at least in the Early or High Medieval texts they are clearly considered to be seven fever-demons; but as the first of the incantations in the Vatican manuscript names all sorts of fevers, there is no reason to believe that either the incantations or the Blæsinge amulet or any of the others are only specifically aimed at malaria, as Stoklund30 and Düwel31 seemed to think, although malaria was known in medieval Northern Europe sim-ply because of the much warmer climate then.32

A detailed list of fevers in the context of an invocation is contained in another Vatican manuscript, Cod. Lat. Vat. 510, 168r, dating from the 12th century and probably originating in the French Premonstratensian Abbey of Clairefontaine in Picardy.33 It certainly was too long to ever have been used on an amulet, but it shows to what extreme detail and completeness a formula for an incantation was able to go to by naming an incredible number of saints, angels and names of God.34 Despite the fact that it does not name any fever demons, it gives a list of the various types of fevers concentrating to the recurrent types of fevers or malaria:

† In nomine domini nostri Jhesus Christi coniuro uos febres cotidianas, biduanas, triduanas, quartanas, quintanas, sextanas, septanas, octavas, nonas usque ad nonam graduationem, ut non habeatis potestatem super hunc famulum dei .N.35

† In the name of our Lord Jesus Christ I conjure you daily fevers, bidaily fevers, three-daily fevers, […] nine-daily fevers, up to the ninth graduation, so that you may not have power over this servant of God N.N.

It seems therefore that the observation made from the description of body parts on the Blaesinge and Romdrup amulets holds true: that it is indeed some general infection, which was only identified by its main symptoms – fever and cold shivers. Such infections belonged, right up to the late 19th century, to the most enigmatic illnesses, especially those with regularly recurrent fever attacks. This is not without good reason, as feverish infections may be caused by viruses (as influenza, three-day fevers/Roseola infan-tum, measles and rubella), by bacteria (as in some cases of influenza), or parasites (as with malaria). As none of these sources have any clear or visible reasons, the assumption of demonic origin is obvious. Thus, to look for demonic help or ways of controlling the demonic forces was an obvious way of dealing with them, and this is what our amulets attempt to do.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Simek 2011; 2013; 2017.

- Cf. Kormáks saga Ch. 22.

- Cf. Stoklund 2003.

- Imer 2015:14–15.

- Cf. Muhl 2013.

- Sørheim 2004:213–214.

- Cf. McKinnel et al. 2004.

- Joh. I, 1–14.

- Imer & Uldum 2015:12.

- Joh. I, 1.

- Düwel 2001; Simek 2011.

- Gastgeber & Harrauer 2001; Düwel 2001.

- Steenholt Olesen 2010:172.

- The recently found and as yet unpublished lead amulet from Svendborg is the third such text from Denmark with an identification of demons and álfar, after the Romdrup and Schleswig amulets. The equation on the Halberstadt cross of a certain Alber with Satan can be added to these.

- Steenholt Olesen 2010:172.

- E.g. Æbelholt-blyamulet Sj 11; Vokslev-blyamulet NJy 57; Køge-blyamulet Sj 14. See http://runer.ku.dk/Search.aspx (as of 1st Feb. 2016).

- Cf. the close comparison of textual units in Düwel 2001.

- Düwel 2001:243.

- Stoklund 1986:207–208.

- Franz 1909 II:483; cf. also Simek 2011.

- Codex Vaticanus Latinus 235.

- Codex Vaticanus Latinus 235.

- Cf. Düwel 2003:243.

- Ohrt 1917–1921 II:1143.

- I am grateful to Joseph H. Peterson for pointing out the Sloane and Folger manuscripts to me.

- Briggs 1959:250–251.

- Wallis 2010:69.

- Wickersheimer 1966:32–33.

- Whether the medieval tradition of the demonic Seven Sisters goes back to the pseudo-epigraphic Testament of Solomo (4th century), where seven sisters of demons are named, and these in turn originally referred to the seven Pleiades of Greek mythology (but they were called Alkyone, Asterope, Ceaeno, Elektra, Maia, Merope, Taugete, which have absolutely no reflection in the medieval names), or else to the Biblical statement that Jesus had driven out seven demons from the body of Mary of Magdala (Luc. 8,2: Maria, quae vocatur Magdalene, de qua septem daemonia exierant), or even have something to do with the legend of the Seven Sleepers (Septem dormientes) still needs further investigation for which this is not the place.

- Stoklund 1986:204–207.

- Düwel 2001:243.

- Cf. also Schmid 1904.

- Schmid 1904:296–297.

- Cf. Simek 2011.35. fol. 168v; Schmid 1904:208.

Bibliography

- Briggs, Katharine Mary. 1959. An Anatomy of Puck. An Examination of Fairy Beliefs among Shakespeare and his Contemporaries. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Düwel, Klaus. 2001. Mittelalterliche Amulette aus Holz und Blei mit lateinischen und runischen Inschriften. In V. Vogel (ed.). Ausgrabungen in Schleswig. Berichte und Studien 15. (= Das Archäologische Fundmaterial II), Neumünster: Wachholtz, 227–302.

- Franz, Adolph. 1909. Die kirchlichen Benediktionen im Mittelalter. 2 Vols., Freiburg i.B.: Herder.

- Gastgeber, Christian & Harrauer, Hermann. 2001. Ein christliches Bleiamulett aus Schleswig. In V. Vogel (ed.) Ausgrabungen in Schleswig, Berichte und Studien 15 (= Das archäologische Fundmaterial II), Neumünster: Wachholtz, 207–226.

- Imer, Lisbeth M. & Uldum, Otto C. 2015. Mod dæmoner og elver-folk. In Skalk 2015, 9–15.

- McKinnel, John & Simek, Rudolf & Düwel, Klaus. 2004. Runes, Magic and Religion. A Sourcebook. Vienna: Fassbaender.

- Muhl, Arnold & Gutjahr, Mirko. 2013. Magische Inschriften in Blei. Inschriftentäfelchen des hohen Mittelalters aus Sachsen-Anhalt. Halle/S.: Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Sachsen-Anhalt (= Kleine Hefte zur Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt 10).

- Ohrt, Friedrich. 1917–1921. Danmarks Trylleformler. Vol. 1: Inledning og tekst. Kopenhagen/Kristiania: Gyldendal. Vol. II: Efterhøst og Lönformler. Kopenhagen/Kristiania: Gyldendal.

- Schmid, Ulrich. 1904. Malariabenediktionen aus dem XII. Jahrhundert. In Römische Quartalschrift 18, 205–210.

- Simek, Rudolf. 2011. Elves and Exorcism. Runic and Other Lead Amulets in Medieval Popular Religion. In D. Anlezark (ed.). Myths, Legends and Heroes. Essays on Old Norse and Old English Literature in Honour of John McKinnell. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 25–52.

- Simek, Rudolf. 2013. Álfar and Demons, or: What in Germanic Religion Caused the Medieval Christian Belief in Demons? In R. Simek & L. Slupecki (eds.). Conversion. Looking for Ideological Change in the Early Middle Ages. Vienna: Fassbaender (= SMS 23), 321–342.

- Simek, Rudolf. 2017. “On Elves”. In S. Brink & L. Collinson (eds.). Theorizing Old Norse Myth. Turnhout: Brepols, 195–223.

- Steenholt Olesen, Rikke. 2010. Runic Amulets from Medieval Denmark. In Futhark. International Journal of Runic Studies 1 (2010), 161–176.

- Stoklund, Marie. 1984. Nordbokorsene fra Grønland. In Nationalmuseets Arbejdsmark 1984, 101–113.

- Stoklund, Marie. 1986. Runefund. In Aarbøger for Nordisk Oldkyndighed og Historie 1986, 189–211.

- Stoklund, Marie. 2003. Bornholmske runeamuletter. In W. Heizmann & A. van Nahl (eds.). Runica – Germanica – Mediaevalia (= Ergänzungsbände zum RGA 37). Berlin: de Gruyter, 854–870.

- Sørheim, Helge. 2004. Lead Mortuary Crosses Found in Christian and Heathen Graves in Norway. In Medieval Scandinavia 14, 195–227.

- Wallis, Faith. 2010. Medieval Medicine. A Reader. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Wickersheimer, Ernest. 1966. Les manuscrits latins de médecine du haut Moyen Age dans les bibliothèques de France. Paris: Centre national de la recherché scientifique.

Contribution (375-389) from Myth, Materiality, and Lived Religion: In Merovingian and Viking Scandinavia, edited by Klas Wikström af Edholm, Peter Jackson Rova, Andreas Nordberg, Olof Sundqvist, and Torun Zachrisson (2019, Stockholm University Press), published by OAPEN under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.