“Prophecy” is a word with many meanings, depending on the context and the user.

By Dr. Martti Nissinen

Professor of Old Testament Studies

University of Helsinki

Prophecy as a Construct

Historical Phenomenon and Scholarly Concept

In January 2016, I attended the concert of the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra performing Richard Danielpour’s percussion concerto The Wounded Healer, conducted by Jacques Lacombe with Lisa Pegher as the percussion soloist. Thework consists of four parts, entitled The Prophet, The Trickster, The Martyr, and The Shaman, “based on different guises and faces that the Wounded Healer might show up as across different cultures,”as told by the soloist on her website.1 Each part introduces a new perspective to the title of the concerto. The concerto begins with austere sound of chimes introducing The Prophet, whose voice, standing clearly out throughout the first part, is followed by The Trickster, a crispy and playful interplay of the marimba with the orchestra. The nearly anguished tone of the xylophone gives expression to the agony of The Martyr, only to give way to the frantic drum solo in the last part, The Shaman.

The respective roles of the four healer characters can be described as the messenger inspired by a higher power (The Prophet), the rule-breaking equalizer (The Trickster), the persecuted advocate of a belief (The Martyr), and the spiritual journeyer having access to the transcendental world (The Shaman). The four characters of Danielpour’s concerto are indicative of the role models attributed to people who are believed—at least by some other people—to be able to mediate between the human and superhuman worlds, bringing about a remedial effect in human society while themselves being wounded by their own activity often seen as bizarre by other members of the community. These persons exist historically, but they also represent a cultural image, both as a projection and as a retrojection.

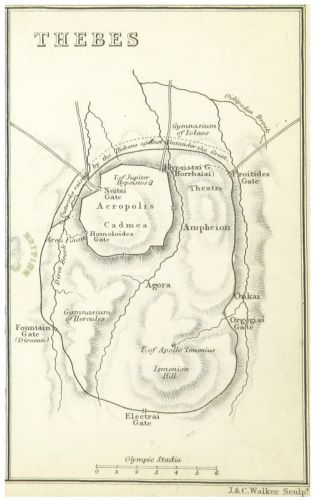

Characters with one or more of the features of Danielpour’s healers can regularly be found in textual sources from the ancient Eastern Mediterranean sphere, whether we think of the biblical prophets, the Delphic Pythia, or the Mesopotamian ecstatics, all appreciated in their time as messengers of the divine—however, not without contestation. It is through these characters and their activities in ancient Near Eastern (including the Hebrew Bible) and Greek texts that this article attempts to draw a picture of the ancient phenomenon known as prophecy.

“Prophecy” is a word with many meanings, depending on the context and the user. It may be used in a very broad sense, including all of Danielpour’s four characters, or in a more restricted sense referring only to specific kinds of activities. A brief look at a dictionary of any modern language will reveal that the most common meanings of the word “prophecy” are related to the prediction of future, the “prophet” being equivalent to a fortune-teller, a soothsayer, or whatever designations are used for persons who claim, or are believed, to be able to see future events. The predictive meaning of the “prophetic” vocabulary is concomitant of the use of similar terminology in the ancient Mediterranean cultures. However, it is evident that there is more to prophecy than just prediction in ancient sources. In fact, the predictive activity appears not to be the primary function of people usually designated as prophets; rather, prediction is but another aspect of mediation of knowledge that is believed to derive from divine sources.

Who are, then, the people we talk about when we refer to “prophets” in the ancient Eastern Mediterranean, and what kind of sources do we look for when we want to know about these people? This is something the scholarly community has to agree about. As a scholarly concept, prophecy is created and maintained by the community of scholars that provides the matrix within which the concept works and the purpose for which it is constructed. As a historical phenomenon, the thing we call prophecy is the multifarious product of socially contingent processes that have taken place in different times and contexts. Both ways, prophecy is not something that is just “out there,” inevitably determined by the “nature of things”; rather, it is a social and intellectual construct that exists if there is a common understanding about what it means and how it can be recognized.2

Prophecy is not (or, perhaps, not anymore) a matter of course. The historical phenomenon and a corresponding scholarly concept cannot be taken for granted but needs to be defined, constructed, and reconstructed by any community that needs it for historically contingent purposes. Prophets, whether as a concept or as a class of people, exist if there is a community acknowledging their existence and providing certain people and practices with such a label.3 The difference between the concept and the people can be seen as one between map and territory: the concept of prophecy is a map attempting to draw a navigable picture of the terrain formed by the sources informing on people and practices we try to interpret.4 Like every map, every concept is also the result of an interpretative process, during which decisions are made concerning the features that are highlighted more than others. A map is not a mere description of the terrain, and “a theory, a model, a conceptual category, cannot be simply the data writ large.”5

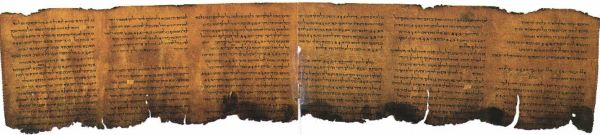

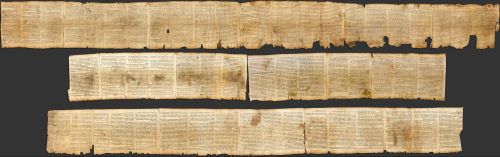

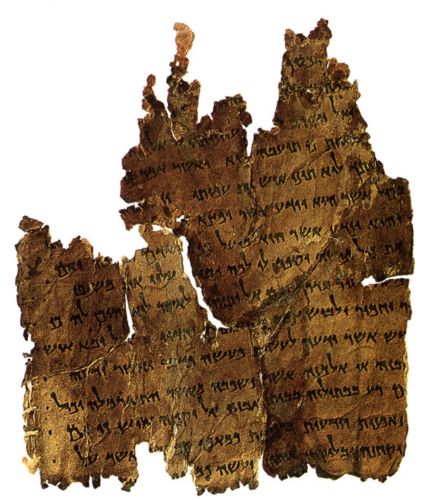

To say that prophecy is a construct is not to say it is not true, much less to diminish the value of the phenomenon thus called or the people involved in it. The construct refers to the scholarly idea and matrix, not to historical people and events. Prophets appear as intellectual constructs already in ancient texts, such as the prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible and in their subsequent learned interpretations in, for instance, the Dead Sea Scrolls.6 To call prophecy a construct, thus, does not deprive prophecy of its historical significance, let alone its veracity—on the contrary, we can hope that the idea and the matrix can help us to identify social contingencies that make our construct absolutely inseparable from historical factualities and people involved in them. Why should we still call it a construct? There are two reasons:first, because all history-writing is based on sources that themselves present constructs of the realities of their time; and second, because we are ourselves subjects of the social and historical processes, indeed, a part of the matrix within which the construct takes shape.

Moreover, even though we should always be careful to distinguish the ancient native (“emic”) constructs from the modern analytical (“etic”) ones, the scholarly reconstruction of an ancient phenomenon is always to some extent a “mimetic” enterprise7 because the modern constructs cannot but rest upon the ancient ones. This does not exclude a critical stance on the ancient constructs, but it certainly makes it difficult to see alternative pictures, unless they are provided by the sources themselves.

Ancient sources always comprise a fragmentary set of different kinds of materials; disconnected pieces of evidence and scattered sets of more or less compatible sources whose relationship we have to establish and reconstruct. This means, figuratively speaking, that we have just a “keyhole” perspective to the past;8 that our sole access to the past is through sources that yield only restricted views of the landscape. Sometimes the perspective is wide, but very often it is quite narrow. Sometimes two or three different keyholes show clearly the same landscape, but very often two keyholes show different parts of a landscape offering only a partial view on it; indeed, we have to decide whether the two views show the same landscape at all. The question is how we are able to connect the fragments, combining the views seen through different keyholes in a methodologically sound and historically reliable way.

Our sources present the prophetic phenomenon in “different guises and faces” depending on the historical context, perspective, and textual genre. Even the academic constructs of prophecy necessarily reflect the diversity of the sources, resulting in a variety of scholarly constructs, often organized according to traditional academic disciplines specializing in specific parts of the ancient Eastern Mediterranean source materials. Therefore, our phenomenon, as presented in academic studies and textbooks, always inhabits a setting in a scholarly agenda, be it a“Theology of the Old Testament, ”a“ History of Greek Religion,” “Ancient Near Eastern Divination,” or another matrix within which the idea of prophecy has a meaning.

Hebrew Bible, Ancient Near East, and Greece

Hitherto, the documentation of ancient Eastern Mediterranean prophecy has been viewed roughly as three distinct groups: biblical prophecy and ancient Near Eastern prophecy, which have been the subject of comparison since the 1950s, plus the Greek oracle, not always designated as “prophecy” and usually not discussed in conjunction with the biblical and Near Eastern sources, even though it could and should be seen as a part of the same landscape in geographical and phenomenological terms. This threefold construction arises from the classification of ancient phenomena according to source materials coming from different times and places, written in different ancient languages, and studied in different academic contexts.

The threefold breakdown of the source material into biblical, Near Eastern, and Greek reflects the current division of academic disciplines and the present state of communication between them. Even the present article is based on this division, however, in awareness of its shortcomings. The canonized biblical text with its long and unbroken history of interpretation has a distinctive literary and historical character very different from the more or less haphazard variety of Near Eastern textual evidence, which, again, shows a picture rather distinct from the Greek sources which also represent a great variety of text types. This may be an incentive for scholars to study the three source materials as integrated entities, presuming a straightforward correspondence of the ancient phenomenon to the image given by the source materials, and imagining the “biblical” (or “Israelite”), “ancient Near Eastern,” and “Greek” prophecies as inherently autonomous, if not autochthonous phenomena. Such a construction has the propensity for hiding the variation within each class while at the sametime highlighting the gap between them. As the result, one may easily lose sight of simple facts, for instance, that the Hebrew Bible is part of ancient Near Eastern literature, and that Greece is actually not worlds apart from Mesopotamia.

The threefold division of ancient prophecy also reflects different interpretative contexts of the ancient material and, consequently, the history of research. The study of biblical prophecy has a long history as an academic pursuit, preceded by an even longer Jewish and Christian interpretative tradition. As a biblical concept, prophecy is contextualized in Jewish and Christian theology and religion, whereby prophecy is not just an object of study but a significant constituent of cultural memory and provider of identity. The academic study of biblical prophecy, for its part, is deeply rooted in nineteenth-century scholarship whose brilliant representatives, such as Julius Wellhausen and Bernhard Duhm,9 were the founding fathers of the scholarly image of what was later to be called the “classical prophecy” of “ancient Israel.”10

When we turn to the study of the so-called “extra-biblical prophecy”—a term to be abandoned, because it lumps together so much different material with the single common denominator of not being biblical—the situation looks very different. Non-biblical prophecy may still often play the role of “the other” in studies of ancient prophecy, because the texts documenting prophecy in the ancient Eastern Mediterranean are hardly a constituent of any modern scholar’s religious tradition. They do form part of our cultural heritage but not of our cultural memory. This is probably why it has been a commonplace until the very recent years to approach the ancient Near Eastern records of prophecy from the biblical point of view, using them as “context of scripture,” a background against which the special features of biblical prophecy can be highlighted. There is nothing to be wondered at about this. The very concept of prophecy has traditionally belonged primarily to the vocabulary of biblical scholars and theologians. On the other hand, the documentation of the ancient Near Eastern prophecy has until the end of the twentieth century remained meager in quantity and restricted both in terms of geography and chronology.

The Bible-centered approach has the disadvantage of highlighting primarily those features in other sources that are useful in resolving biblical problems and serve the comparative purpose, and neglecting other, perhaps more significant aspects. Furthermore, a value judgment in favor of biblical prophecy, spoken or unspoken, can be recognized especially when it comes to the ethical proclamation of the biblical prophets which allegedly sets them qualitatively apart from their cognates in the ancient Near East.11 The higher appreciation of the biblical prophecy is closely related to the idea of ethical monotheism found in texts of the“writing prophets”of the Hebrew Bible, who, therefore, have been strictly divorced from their religio-historical environment and elevated to a higher level of spirituality.12

Compared to biblical prophecy, the ancient Near Eastern texts related to prophecy have been the object of active study for only a relatively short period. The very category of “ancient Near Eastern prophecy” did not emerge before the last decades of the twentieth century, and it is still sometimes ignored by Assyriologists.13

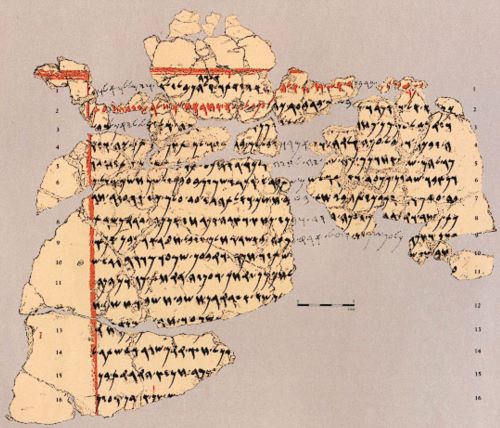

Even though it was still possible in the 1950s to hold the opinion that biblical or Israelite prophecy had no historical counterpart,14 some historians of religion of the first half of the twentieth century, such as Gustav Hölscher, Johannes Lindblom, and Alfred Haldar, duly recognized sources comparable to biblical prophecy, without, however, having much ancient prophetic material to refer to.15 Some of the texts from the seventh century BCE now known as Assyrian prophecies were published already in 1875 but were recognized as anything comparable to biblical prophecy by a few scholars only.16 The comparative work on prophetic sources—or better, the search for parallels to biblical prophecy—was slowly revived only when the eighteenth-century BCE archives of Mari were discovered and several letters with a prophetic content were published from 1948 on,17 culminating in the 1988 edition of the main bulk of the epistolary material by Jean-Marie Durand.18 Assyrian prophecy re-entered the scholarly agenda in the early 1970s, but Simo Parpola’s edition of the texts had to wait until the late 1990s,19 after which the number of studies devoted to Neo-Assyrian prophecies, often in comparison with their parallels in the Hebrew Bible and in the letters from Mari, has multiplied.20

The publication of the two main corpora of sources has been the prerequisite of recognizing ancient Near Eastern prophecy as a meaningful category. To date, the documentation of prophecy in the ancient Near East, that is, Mesopotamia, Syria, and the Levant, comprises over 170 texts,21 which makes it possible to study it in its own right and not just as a parallel phenomenon to biblical prophecy. This by no means excludes comparative studies—on the contrary, it enables the comparison of the textual materials on a broader basis and in a more critical fashion.

While ancient Near Eastern and biblical prophecy are now generally perceived as belonging to the same picture, the discussion on the relationship between ancient Near Eastern prophecy and Greek oracle is still at an initial stage. Even the use of common terminology has taken different routes at some significant points: classicists may use the word “prophecy,” but not quite in the same meaning as biblical scholars who, for their part, use the word “oracle” typically in a more narrow sense than the classicists.

The Greek oracle, the Delphic oracle in particular, has been the object of scholarly study for quite as long a time as biblical prophecy;22 however, the different historical and academic contexts seem to have discouraged a thorough comparison between the sources for Greek oracle and biblical or other Near Eastern texts. As a consequence, Greek oracle and biblical and Near Eastern prophecy have been approached as more or less strictly distinct categories. Classical scholars belonging to older generations would rather flatly deny any relevance of Near Eastern or biblical materials for the study of the Greekoracle.23 Fortunately, we can today observe an increasing and mutual interest in exploring the Greek, Near Eastern, and biblical materials as belonging to the shared cultural sphere of the ancient Eastern Mediterranean, whatever their mutual connection and influence might be thought of to have been.24

Constructing the big picture of ancient Eastern Mediterranean prophecy has long been obstructed by the separate lives of the disciplines of biblical and classical studies, and the late appearance of a larger bulk of pertinent Mesopotamian sources to the scholarly agenda. The picture is still in the making, but a scholarly motivation is emerging for constructing it as big and attractive as the sources enable it to appear.

Prophecy as Divination

Why Divination?

Once we have agreed that prophecy is not simply “out there” but is a social and intellectual construct, the existence of which is the matter of mutual agreement of the community who provides the matrix within which the idea of prophecy works, we will also have to contextualize it, defining its relation to other related matrices, first and foremost to the concept and institutions of divination.25

As the starting point for the contextualization, we mayfirst pay attention to the notion of divine–human communication—a cross-cultural idea to be found independently in different times and cultures and belonging to the basic architecture of human perception of what is perceived of as superhuman or supernatural. The people living in the ancient Eastern Mediterranean world, as far as our sources enable us to know, did not reckon on an absolute chasm between the natural and the supernatural. Everything that happened was “natural” in the sense that “nature” belonged to the domain of the supreme agency of the divine agents whose capabilities, if not absolutely unlimited in every case, clearly exceeded those of humans. The alleged activity of the divine agents was“superhuman”indeed because of its indefinite capacity, without, therefore, being perceived of as “supernatural.” The difference between humans and deities was recognized and actively maintained in various ways, but it was nevertheless not totally unbridgeable. Communication between the domains was seen as a distinct possibility, and collaboration between human and divine agents was believed to take place.

The idea of communication between human and divine realms implies the idea of the agency and intentionality of divine, or superhuman, agents (gods, spirits, demons, and the like) who are in possession of knowledge that is not ordinarily available to human beings.26 The mental idea of a superhuman becomes practicable in various public representations such as practices, institutions, and artifacts, which are needed for the maintenance and elaboration of mental ideas.27 The idea of divine–human mediation can be seen as a universal product of the human mind. The human intuition about gods communicating with humans is a mental representation taking shape either independently or through cultural contacts in different social settings. An institution or a practice, on the other hand, is a public representation based on the mental representation.

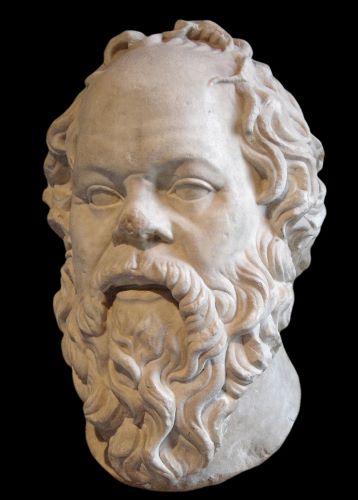

Within the cognitive framework involving divine agency, superhuman knowledge is typically perceived of as a secret of gods, which is normally hidden from humans. Socrates, according to Xenophon:

if there was no room for doubt, he advised them to act as they thought best; but if the consequences could not be foreseen, he sent them to the oracle to inquire whether the thing ought to be done.28

The deepest secrets, says Socrates, the gods reserved to themselves, hence:

what is hidden from mortals we should try to find out from the gods by divination for to him that is in their grace the gods grant a sign.29

Divine knowledge may be mediated to humans by means of specific practices and rituals performed by specialists “in the grace” of the gods, authorized by respective institutions (prophets, diviners, shamans, and the like). These practices and institutions scan be seen as “networks of systematic relations, correlations and causations between this and the ‘other world’: things in this world are signs of necessity, knowledge and intentionality.”30 Human communities tend to institutionalize such a communication by appointing specialists who master the specific techniques and skills necessary for its maintenance. In the ancient Eastern Mediterranean world, such specialists were appointed by virtue of their background, education, personal skills, or behavior—not every person was qualified to do that. While gods were typically thought to be free to communicate with anyone by any means, accredited institutions of divination were usually regarded as the most reliable interpreters of the “signs of knowledge.”31

The rationale behind divination is, thus, (1) the human experience of the lack of full knowledge of things essentially important for running the everyday life; (2) the belief in superhuman full-access agents who possess this strategic information;32 and (3) the availability of this information to humans to a certain extent by way of consulting the full-access agents with the help of divinatory experts. The need for divination is triggered by uncertainty, and its purpose is to become conversant with superhuman knowledge in order to “elicit answers (that is, oracles) to questions beyond the range of ordinary human understanding.”33 Where the source of the uncertainty is found in human ignorance of divine decrees, divination is there to help both individuals and communities to explain contingency, to reduce anxiety about the uncertainty and insecurity of human life, and to cope with the risk brought about by human ignorance.34

Divination is one of the systems of knowledge and belief that serve the purpose of the maintenance of the symbolic universe.35 The phenomenon of divination is known from all over the world in societies sharing the conviction that things happening on earth are not coincidental but managed by superhuman agents, reflecting decisions made in the world of gods or spirits. In ancient Eastern Mediterranean cultures divination had a fundamental socio-religious significance. In spite of philosophical discussions on the role of chance in human life, “[f]or most Greeks there was no such thing as ‘coincidence,’”36 and the same can be said of ancient Mesopotamians and the Levantine peoples, whose divinatory practices are well documented. In Mesopotamian texts we find the concept of šīmtu, often translated as “fate,” but better understood as the divinely fixed order of things that is involved “in the most basic levels of human experience; the personal, social, and cosmic, that is to say, in the sphere of man’s relation to the gods.”37 The šīmtu was decreed by gods, but it was not deterministic and unalterable, since gods were always free to do what they wanted. Even chance, therefore, had a divine agent.

Divination and Magic

Divination and magic belong to the same conceptual world. “Magic” can be defined as symbolic ritual activity with the purpose of attaining a specific goal by means of divine–human communication and superhuman assistance, relying on specific skills, actions, and knowledge required from the human agent.38 Magic and divination have much in common. Both are based on collaboration of human and superhuman agents who often are acknowledged as accredited professionals with special skills and capacity of intermediating between divine and human worlds. Diviners and magicians may also be distrusted, either because of their faulty performance or because the superhuman powers represented by them are found either hostile or futile.39

However, there is a difference between magic and divination with regard to their practice and purpose. The function of divination is to acquire and transmit superhuman knowledge. Diviners receive messages and omens that are believed to be of divine origin and transmit the divine knowledge to their audiences, often with an interpretation of the meaning of the messages and omens they have received. The recipients of the message are supposed to draw their own conclusions of how this knowledge should be implemented. Magic, again, attempts to bring about a change in the life of the patient, whether beneficent (healing, warding off evil) or harmful. While the function of divination, hence, is to acquire and transmit divine knowledge, the purpose of magic is to cause a direct effect to the patient in collaboration with the divine powers.40

Magic is typically ritual activity, while divinatory acts may or may not be accompanied by a ritual. The divinatory performance depends on the method. While the prophetic performance typically happens in an altered state of consciousness, haruspices perform their divinatory rituals in an ordinary state of mind. The outcome of the prophetic performance is primarily oral, while the outcome of the reading of the entrails of a sacrificial animal is reported in a written document. In both cases, the verbal expression has a narrative function, expressing the divine will in a verbal form. In magical acts, the function of verbal expressions is performative rather than narrative: instead of transferring information, they are performed to fulfill the purpose of the magical act. Both magic and divination may make use of material objects. In divination, the sheep liver or the constellation of stars serve as platforms of the omens to be interpreted. In a magical act, the material element may represent the patient of the act (for instance, hair), or symbolize the divine protection (for instance, amulet).

Differences in function and performance entail differences in agency. The agency of the diviner is essentially reception and intermediation of super-human knowledge, while the agency of a magician is rather putting such knowledge into practice. Therefore, the agency of the magician is typically more proactive and goal-oriented than the agency of the diviner. Applying Jesper Sørensen’s cognitive model of human action consisting of the conditional space, the action space, and the effect space, we could say that divinatory agency is essentially related to the preconditions of the action and, hence, performed in the conditional space, while magical agency is bound to the effect and, therefore, belongs to the action space.41

In spite of the differences in function, performance, and agency, the roles of the diviner and the magician may be assumed by one and the same person. Prophets, such as Isaiah or Jeremiah, sometimes perform acts that certainly belong to the effect space of human action (2 Kgs 20:7/Isa. 38:21; Jer.51:59–64). A prophet’s hair and a fringe of a cloth may be used by another diviner to test whether the prophecy is trustworthy.42 In the Greek magical papyri from Roman Egypt, divination appears as but one of a variety of magical practices.43 On the conceptual level, magic and divination are, therefore, polythetic categories sharing certain family resemblances.

Two Types of Divination?

Since divination is understood as divine–human communication, the role of the diviner is basically that of an intermediary between the human and superhuman domains. Sources from the ancient Eastern Mediterranean reveal a considerable variety of methods of divination.44 These methods are often divided into two broad categories:45

- technical, or inductive methods that involve systematization of signs and omens by observing physical objects (extispicy, astrology, lot-casting, bird divination, fish divination, oil divination, etc.); and

- intuitive, or inspired, or non-inductive methods, such as dreams, visions, and prophecy.

The basic difference between the two types is that in the first category, divine knowledge is believed to be acquired by a cognitive process, while in the second category, it is supposedly obtained through inspiration or spirit-possession. Ulla Koch’s distinction between artificial and natural divination amounts essentially to the same, but is based on the divinatory apparatus: “artificial divination relies on signs or messages, which have to be decoded whereas natural divination is perceived as immediately intelligible.”46 This classification of divinatory methods appears at its clearest in Mesopotamian societies, where diviners were typically educated specialists of one art of divination, and the job descriptions of the haruspex, the astrologer, the exorcist, and the prophet did not overlap.47

The distinction between artificial and natural derives from Cicero’s treatise De divinatione, where he recognizes these two types of divination.48 Cicero addresses the significance of divination for philosophical inquiry into the relationship of divine and human worlds. For Cicero, the mantikē of the Greeks meant the foresight and knowledge of future events (praesensio et scientia rerum futurarum) acquired by means of consulting the counsel of the gods (consilium deorum). Cicero acknowledges both technical divination, such as Assyrian and Chaldean astrology, and non-technical divination, inspired in two ways, “the one by frenzy and the other by dreams” (uno furente, alterosomniante).49

Cicero was demonstrably aware of the variety of divinatory practices in the ancient Eastern Mediterranean and even Mesopotamia,50 and his distinction of artificial and natural divination derives from Plato’s discussion on divination in Phaedrus (244a–245a), where Socrates notes the difference between divinely inspired knowledge based on mania (“madness”) and divinatory tekhnē based on observation and calculation. Socrates is strongly in favor of the former as a source of divine knowledge: according to his reasoning, mania is divinely inspired and therefore superior to a sane mind (sōphrosynē), which is only of human origin:

in reality the greatest of blessings comes to us through madness, when it is sent as a gift of the gods. For the prophetess at Delphi and the priestesses at Dodona when they have been mad have conferred many splendid benefits upon Greece both in private and in public affairs, but few or none when they have been in their right minds; and if we should speak of the Sibyl and all the others who by prophetic inspiration have foretold many things to many persons and thereby made them fortunate afterwards, anyone can see that we should speak a longtime. . . . The ancients, then testify that in proportion as prophecy (mantikē) is superior to augury, both in name and in fact, in the same proportion madness, which comes from god, is superior to sanity, which is of human origin.51

Another type of mania is beneficial in curing sicknesses, and yet another the one that comes from the Muses, inspiring songs and poetry.52 In his dialogue with Ion, Socrates juxtaposes the diviners with the poets inspired by the Muses while arguing for the divine origin of poetry:

For not by art do they utter these things, but by divine influence; since, if they had fully learned by art to speak on one kind of theme only, they would know how to speak on all. And for this reason God takes away the mind of these men and uses them as his ministers, just as he does soothsayers and godly seers (khrēsmōdois kai tois mantesi tois theiois), in order that we who hear them may know that it is not they who utter these words of great price, when they are ou tof their wits (nous mēparestin), but that it is God himself who speaks and addresses through them.53

In this passage, even the seers (manteis), like the poets, are said to speak while “out of their wits.” This is noteworthy as the designation mantis was used by inspired and technical diviners alike. This does not neutralize the distinction but relativizes it—and not only on a terminological level, since our sources suggest that the Greek “soothsayers and godly seers” could sometimes divine in both ways. Greek sources describe lot-casting at Dodona and Delphi, whose female prophets are usually thought of to have delivered their oracles in the state of mania.54 Therefore, while the Platonic distinction should be fully acknowledged,55 we should not assume that the Greek divinatory practices over several centuries were necessarily organized according to this divide. Moreover, the distinction should refer to the practices of transmission rather than to Plato’s judgments about the diviners themselves.56

A different, and perhaps more momentous, dichotomy can be found in the Hebrew Bible where forms of divination other than prophecy are generally condemned as belonging to the foreign practices forbidden to the people of Israel:

When you come into the land that the Lord your God is giving you, you must not learn to imitate the abhorrent practices of those nations. No one shall be found among you who makes a son or daughter pass through fire, or who practices divination, or is a soothsayer, or an augur, or a sorcerer, or one who casts spells, or who consults ghosts or spirits, or who seeks oracles from the dead. For whoever does these things is abhorrent to the Lord; it is because of such abhorrent practices that the Lord your God is driving them out before you. You must remain completely loyal to the Lord your God. Although these nations that you are about to dispossess do give heed to soothsayers and diviners, as for you, the Lord your God does not permit you to do so.57

In a less polemical mood, a biblical psalm refers to the supreme knowledge of God too wonderful for a human being to understand and too high to be attained, ending with the request:

Search me, O God, and know my heart;

test me and know my thoughts.

See if there is any wicked way in me,

and lead me in the way everlasting.58

Read against the background of divination, this psalm sounds like the end of it: there is no way to become conversant with divine knowledge. God’s thoughts cannot be tested by humans in order to cope with the uncertainty and insecurity of everyday life; instead, God will test “if there is any wicked way” in the psalmist’s life.

Prophecy becomes the privileged way of God’s communication with humans in the Hebrew Bible. The elevated status of prophecy is not challenged anywhere in the biblical and early Jewish tradition, and biblical prophetic texts become the object of intensive reinterpretation—indeed, omens to be interpreted.59 However, even in the Hebrew Bible, divination other than prophecy is not censured altogether.60 Dreams may play an important role in revealing the divine will, and cleromancy (lot-casting) performed by notable figures such as Joshua and Samuel is reported with approval (Josh. 7:14–18; 1 Sam. 10:20–1). The oracle devices called ephod as well as urim and thummim are legitimately used by David (1 Sam. 14:41–2,23:1–13, 30:7–8), and the last mentioned divinatory apparatus is placed prominently in the high priest’s sacred breastplate (Exod. 28:30; Lev. 8:8). The narrative about Jehoshaphat’s and Ahab’s consultation of prophets mixes binary questions typical of technical divination with the rather ecstatic comportment of the prophets (1 Kgs 22). Daniel’s divinatory skills were found “ten times better than all the magicians and enchanters” in Babylonia (Dan. 1:20). Daniel’s excellence “in every aspect of literature and wisdom” (Dan. 1:17) is noteworthy because there is enough evidence of the use of Babylonian astrology in the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Talmud to demonstrate that certain arts of divination may have been forbidden but still practiced in communities belonging to the biblical stream of tradition.61

The examples from Plato, Cicero, and the Hebrew Bible show conclusively, albeit in different ways, that while the distinction between technical (inductive) and intuitive (inspired) divination was recognized by the ancient writers, the boundaries between these two basic kinds of divination fluctuate in Greek sources and, to a lesser extent, in biblical texts. Even anthropological evidence of divination points to the same direction: technical, intuitive, and interpretative techniques easily overlap.62

Mesopotamian sources, on the other hand, provide abundant evidence of highly specialized and non-exchangeable divinatory methods with equally specialized practitioners. Extispicy and astrology in particular follow specific procedures of experiment (observing or manipulating specific phenomena), interpretation (applying the divinatory code), and actualization.63 This modus operandi differs very much from the non-technical divinatory procedures not involving systematic observation, empirical methodology, and education in these skills, even though the motivation triggering the procedure and the action following it may not be essentially different. Harold Torger Vedeler has recently suggested that the two types of divination represent different cognitive modes. Technical divination, such as extispicy, utilizes a logico-scientific mode in explaining superhuman causality by way of systematized observation. Intuitive divination, such as prophecy, is based on a narrative mode in transmitting divine knowledge to the audience without using any analytical tools.64

All this gives reason to a fourfold conclusion:

- The phenomenon of prophecy should be regarded as another type of divination of the intuitive kind, not an antithesis of divination at large;

- The distinction between technical and intuitive divination makes sense, and both the practices and the practitioners of the two types of divination can usually be distinguished from each other; however,

- The dichotomy of technical and intuitive is not absolute but emerges differently in different cultures and source materials, sometimes allowing overlaps of different divinatory methods;

- Both kinds of divination belong to the same (local) symbolic universe, in whatever way it is articulated, and fulfill the function of helping communities and their individual members to cope with contingency, uncertainty, and insecurity.

As a corollary of this fourfold conclusion, it is now possible to start drawing the image of a diviner called a prophet in this article: a person who transmits divine knowledge predominantly, if not exclusively, by non-technical or intuitive means, believed to be inspired by a divine agent.

Prophets as Intermediaries

What Is Prophecy?

Inspired intermediaries are known by several designations in written sources from the ancient Eastern Mediterranean, whether written in Akkadian, Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic, or even in Egyptian or Luwian. The scholarly concept of “prophecy” does not cover exactly the semantic field of any of the designations known from ancient sources; even the fact that the modern word-family “prophet”—“prophecy”—“prophesy” in different languages is derived from the Greek prophētēs—prophēteia—prophēteuō does not entail semantic correspondence. Moreover, as we have seen, the use of the word-family in modern vernacular does not correspond to scholarly needs either. Therefore, we need to define the scholarly field of application of “prophecy” and “prophets.”

As argued above, “prophecy” is a scholarly concept constructed by the community of scholars that provides the matrix within which the concept works. What Jonathan Z. Smith said about “religion” more than three decades ago is, mutatis mutandis, true for “prophecy” as well; according to Smith, religion “is solely the creation of the scholar’s study. It is created for the scholar’s analytical purposes by his imaginative acts of comparison and generalization.”65 Hence, whatever is defined as prophecy is not an image of truth but an aid of communication between scholars specializing in different materials.

From the point of view of the sociology of knowledge, the definition of prophecy, like any definition, should be seen as a methodical process that emerges from concrete needs of the scholarly community, not claiming finality but developing along with its application. Moreover, the definition should be an aid, not an impediment, to the study of the sources; it should clarify, not complicate things. An over-exact and monothetic definition is not helpful because it may restrict all too much the scholar’s view which is already narrowed by the nature of the source material. A polythetic definition66 allowing variation within the defined entity enables the identification of—to use a Wittgensteinian term—family resemblances67 between materials without forcing them into a theoretical and terminological straightjacket.

Keeping this in mind, it is interesting to note that the definition of prophecy first formulated in 1988 by Manfred Weippert, a pioneer of the study of ancient Near Eastern prophecy, has held sway over decades and can still be taken as a point of departure. According to Weippert’s definition, prophecy is in question when a person

(a) through a cognitive experience (a vision, an auditory experience, an audio-visual appearance, a dream or the like) becomes the subject of the revelation of a deity, or several deities and, in addition,

(b) is conscious of being commissioned by the deity or deities in question to convey the revelation in a verbal form (as a “prophecy” or a “prophetic speech”), or through nonverbal communicative acts (“symbolic acts”), to a third party who constitutes the actual addressee of the message.68

Weippert’s definition has not gone without criticism, especially with regard to the aspect of cognition and consciousness,69 but it has the advantage of notbeing over-exact and focusing on the procedure rather than its paraphernalia. Moreover, an undeniable strength of this definition is the clarity with which it describes the prophetic process of communication as an act of divine-human intermediation consisting of four basic components:

- The sender of the message, believed to be a superhuman agent;

- The actual message and its verbal or symbolic performance;

- The prophet, that is, the diviner who mediates the divine message;

- The human recipient(s) of the divine message.

This divinatory procedure, drawn from ancient Near Eastern sources but applicable even to Greek material,70 can be seen as the most important polythetic characteristic of the defined phenomenon. While well compatible with the definition of divination,71 it is also clearly distinct from the procedure of technical divination based on systematic observation of signs. The relationship of prophecy to other kinds of divination is not part of Weippert’s definition but can be deduced from it by comparison with the procedure of extispicy or astrology, which, as sketched by Ulla Koch, consists of six steps: motivation, experiment, validation, interpretation, actualization, and action.72 The second, third, and fourth steps involve skills in observation, manipulation, and classification of specific phenomena and application of authoritative written tradition that can only be attained through education. The performance of the prophetic procedure, not requiring the management of such skills and education, is rather more simple and straightforward. Nevertheless, the pre- and post-performance steps, that is, motivation, actualization, and action belong to both types of divinatory procedure and may turn out to be essentially similar.

I would like to develop Weippert’s definition of prophecy by complementing it with the following five viewpoints.

First, the prophetic process of communication is a form of social communication, not a one-way street from the deity through the prophet to the addressee, perhaps through one or more go-betweens. The prophetic performance happens within a community that ultimately makes prophecy functional by acknowledging its value, veracity, and applicability.73 The recognition of the performance as prophecy presupposes a shared belief in the superhuman full-access agent(s), that is, the deity or deities whose words are being mediated, and the shared conviction of the community (or at least some part of it) of the capacity of the person in question of acting as a true prophet. This conviction often arises from the patterned public behavior of the prophet, which, however, is too variable to be made part of the definition.

Second, as the written evidence of prophecy demonstrates, the prophetic process of communication does not necessarily end when the message has reached its recipient, but may be prolonged by means of writing. Sometimes the written record, such as a letter, is the way by which the message is conveyed to the addressee, but a written version of the prophetic message may also be prepared for archival purposes, thus becoming part of the scribal tradition that can have a long afterlife. A prophecy once written down can be reinterpreted in a new historical situation and, as in the case of the Hebrew Bible, become the object of a long process of literary interpretation, or Fortschreibung.74 Following Armin Lange, I make a difference between written prophecy, that is, written records of orally delivered prophetic oracles, and literary prophecy, which covers both scribal interpretation and recontextualization of earlier written prophecies and inventing entirely new prophetic texts.75

Third, because of the implications of the use of the “prophetic” vocabulary in modern vernacular, it may be necessary to say a word on the relationship of prophecy and prediction. Since the uncertainties of life very are often related to the impossibility of seeing around the corner, it is clear that Zukunftsbewältigung,76 coping with the future, is part and parcel of all divination. This is true even for prophecies which, however, are usually not downright descriptions of what will happen in the future. Prophecies may include predictions as an element of the transmitted divine knowledge, but a predictive text is not per definitionem a prophecy.

Fourth, Weippert’s definition works best when applied to ancient Near Eastern material but may not be fully applicable to Greek or even biblical texts. This is not to say that there are no persons corresponding to prophets thus defined in these texts; however, it may turn out that the Greek (and to some degree, biblical) prophets do not represent exactly the ideal type of an inspired diviner portrayed by the definition. As we have observed above, the distinction between technical and intuitive divination is nearly absolute in Mesopotamian sources, but less so in Greek ones. This does not invalidate the use of the definition for Greek prophets; we only have to allow for some flexibility with regard to the divinatory method in individual cases.

Fifth, the separate lives of the academic disciplines have resulted in a divergent terminology of Classicists, Assyriologists, and Bible scholars; therefore, whatever terms are used for diviners of different kinds may cause communicational problems. My own predilection for the word “prophecy” is certainly due to my education in biblical studies, the academic domain where this word has been always at home. Today, the word “prophecy” is increasingly becoming part of the Assyriological vocabulary as well;77 however, Classical scholars usually prefer the terms “oracle” and “seers” for what biblical and ancient Near Eastern scholars call “prophecy” and “prophets.”78 In addition, the word “oracle” is not only used for the outcome of the divinatory procedure but also of the person who delivers the divine message and the site where all this takes place.

To reduce the effects of the confusion caused by the divergent terminology, I would like to clarify my own use of it. I use the term “prophet” for a diviner of the intuitive or non-technical type corresponding to Weippert’s definition, whether the person in question is found in Near Eastern, Greek, or biblical sources. I have nothing in principle against the term “seer,” but I do not use it very often, because the term denotes diviners of both types and may, therefore, be potentially confusing. With the word “oracle” I refer primarily to “verbal communications to humans from the gods or other supernatural beings,”79 including prophecies but not excluding other verbal outcomes of divination.

Who Were the Prophets?

Having now defined a “prophet” as someone who intermediates allegedly divine knowledge by non-technical means, let us now take a look at the sources to find the people at the roots of this definition. Meanings of words in modern languages cannot be determined by their use in ancient times;neither should modern semantics interfere too much with the reading of ancient sources. The word-family “prophecy” is a parade example of shifting sands in semantics. First, the use of this word-family in modern languages owes its use first and foremost to the Bible, which has made some scholars hesitant to use it in non-biblical contexts.80 However, if its use is categorically denied outside the biblical tradition, biblical prophecy becomes isolated from related phenomena in the ancient Near East and closed up in its own biblical ghetto, which easily appears as an all too coherent and unproblematic whole in comparison with the variegated hodgepodge of ancient Near Eastern divination. Second, the strongly personalized association of prophecy with a certain kind of a person with the specific idea of the characteristics of a “true prophet” easily leads to the search of similar persons in other languages and cultures, even though the comparative quest should primarily concern functions and phenomena rather than persons.81 Third, there is no one title or concept for prophets and prophecy in ancient languages, and therefore, the “who’s who” in ancient prophecy must be based on a scholarly construct rather than emic terminology.82 I try to keep these problems in mind when looking for the answer to the important and legitimate question of who the prophets were.

Since different languages, the academic terminology included, have inherited the “prophetic” word-family from Classical Greek, it makes sense to start with Greek sources and their divinatory terminology. When the translators of the Septuagint needed a Greek equivalent for the Hebrew word for a prophet, nābî’, they quite systematically chose to use the word prophētēs, which in their view, rendered an idea that was close enough to what they thought anābî’ was. The Greek word-family was thus influenced by a strong semantic input from the biblical tradition, which had effects on its use in early Jewish and Christian parlance and writing.

For an overview of the Greek semantic field, a quick look at Liddell and Scott’s Greek–English Lexicon83 will show that prophēteia is presented as equivalent to the “gift of interpreting the will of gods” and the verb prophēteuō to being an “interpreter of the gods,” whereas prophētēs (fem. prophētis) is “one who speaks for a God and interprets his will to man,” or, in a more general sense, an “interpreter.” In the New Testament, the word-family has a more specialized meaning, reflecting especially the gift of expounding scripture, speaking and preaching—even predicting future events.

A deeper look at the sources confirms Liddell and Scott’s basic semantic fields, but also shows some variance depending on time, place, and literary genre. The most common Greek term for a diviner is mantis (pl. manteis), a word which Plato derived from mania, arguing that the word was the result of the tasteless insertion of the letter “t” to the original word.84 Elsewhere, Plato argues that “no man achieves true and inspired divination when in his rational mind, but only when the power of his intelligence is fettered in sleep or when it is distraught by disease or by reason of some divine inspiration.” The inspired speech of a mantis, then, must be interpreted by other people with sound mind, whom Plato would call prophētai manteuo menōn, “prophets of things divined,” rather than manteis.85 Plato’s use of the word prophētēs focuses here on the mediatory and interpretative quality of the word rather than to the inspired state of the diviner, implying a similar chain of communication as Pindar: “Give your oracle, o Muse, and I will be your prophet!”86 Plato alsousesprophētēsin the sense of prognostication: “And if you liked, we might concede that prophecy (mantikē), as the knowledge of what is to be (epistēmētou mellontos), and temperance directing her, will deter the charlatans, and establish the true prophets (alēthōs manteis) as our prognosticators (prophētastōn mellontōn).”87

In the last quoted passage of Plato, the semantic difference between themantisand the prophētēs is minimal, which, however, is not always the case. In Greek texts, the word mantis is used for several kinds of male and female diviners from legendary heroes to itinerant diviners without implying a distinction between different technical or non-technical methods of divination.88 It is much more frequently used than the word-family prophētēs which, despite Plato’s above-quoted opinion, more often than not denotes inspired divination and transmission of divine words.89 This corresponds to the etymology of the word, consisting of the elements pro– “before, on behalf of” and phēmi “to say, to declare, to make known one’s thoughts,” and enabling a twofold meaning: speaking on behalf of the deity, or speaking before the deity and/or the people. The word promantis conveys basically the same idea and is used more or less synonymously with prophētēs or prophētis.90

The word-family prophētēs does not appear before the fifth century BCE and is rarely used in texts written between the fifth and the third century.91 Only a dozen writers use prophētēs or prophētis before the third century, among them Herodotus, Aeschylus, Euripides, and Plato, and people thus designated include both mythical diviners such as Cassandra and Teiresias,92 and historical figures such as the female prophets at Delphi and Dodona.93 The male term also denotes a temple official responsible for the oracular process at Delphi and mediating the words of the Pythia to the consultants—among other duties.94 In the Hellenistic period, the use of prophētēs and prophētis becomes much more common and it is widely used also in inscriptional material from the third century BCE onwards. In the temple of Apollo at Didyma, the female prophet is called prophētis or promantis (but not mantis95), whereas the title prophētēs does not belong to the inspired seer but to the mediating official responsible for the publicizing of the oracular responses given by the female prophet and administering the oracular process.96 At Claros, again, the inspired prophet was a male person, also known as hypophētēs; the title is a semantical equivalent of prophētēs. There are two theories concerning the identity of the male prophet at Claros. Either he was the prophētēs, whose oracular responses were perhaps versified by the poetic chanter the spiōdos, who would then deliver them to both the consultants and the grammateus who eventually wrote them down;97 or according to another theory, the roles of the prophētēs and the thespiōdos were reversed, the last-mentioned official acting as the inspired speaker.98

In sum, the male term prophētēs can denote either a male prophet or a mediator of prophetic messages, while prophētis is used exclusively for the female prophets. In both cases, the persons thus defined appear to have an affiliation with an oracle site.99 The word-family, hence, inhabits a semantic domain of intermediation of divine words in the socio-religious setting of temples where non-technical divination was practiced—in contrast to the word-family mantis which covers a larger semantic field and does not as such imply a setting in oracle shrines. Therefore, any prophet may be called mantis but not every mantis is a prophet.

Since the vocabulary of the Hebrew Bible contributes to the later use and understanding of the Greek prophetic vocabulary through the Septuagint, we discuss it before turning to the Mesopotamian terminology. The “master term” for a prophet is nābî’ (fem. nĕbî’â, pl. masc. nĕbî’îm). With its 325 occurrences,100 it is used far more often than any other related designation and becomes the technical term for (mostly) non-technical divination in the Hebrew Bible. This term is used for more than fifty biblical characters who either carry this title or are otherwise acting as anābî’. Non-biblical evidence of nābî’ consists of only a couple of occurrences in the letters from Lachish dating to c.600 BCE.101 The word is usually understood as a nominal qatīl– derivative of the Semitic root nb’/nbyto be interpreted in a passive sense as “the one who has been called,” that is, by a divine agent.102

The most common image of a nābî’ is that of an oracle-deliverer such as the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, or Ezekiel or, say, Gad, Ahijah of Shiloh, Huldah, and Shemaiah103—even Moses as the mediator of the Torah.104 The basic occupation of a nābî’ in the Hebrew Bible is clearly the transmission of the word of God to the person or the people to whom it is addressed, either to an individual—typically a king—or to a community. The substance of the message is often called “word of Yahweh” (dĕbar Yhwh) that “comes” or “happens” to the prophet,105 or a “vision” (ḥāzôn) seen by the prophet.106 The prophet’s reception of the divine message is described by the verb “to see (a vision)” (ḥzh),107 and the outcome of the prophetic performance may also be called “oracle of Yahweh” (nĕ’um Yhwh) or just “oracle” (maśśā’).108

The Hebrew verbs denoting prophesying, nibbā’ and hitnabbē’, are derived from the noun nābî’ and have the meaning “to act as/like a nābî’,” the last mentioned form sometimes taking on a demeaning sense of “pretending to be a nābî’.”109 The verbs are used almost exclusively of delivering divine messages,110 and refer many times explicitly to a spirit-possessed ecstatic behavior.111 The same vocabulary is also used for persons condemned as false prophets.112

While the emphasis of the word nābî’ is clearly on the transmission of divine messages, the biblical text lets people thus designated appear in various other divinatory roles, too. Prophets are never found practicing technical divination that would require a special education, such as extispicy, augury, or astrology. However, some prophets are presented as observing ominous things113 or even promising an omen or portents,114 and some are found performing healing rituals.115 Dreams, visions, and prophecies are many times presented as cognate or parallel phenomena.116 Occasionally, the prophet’s advice seems to be based on clairvoyance rather than a divine word.117 Some persons like Moses, Miriam, Deborah, and Samuel are divinely inspired leaders or judges rather than prophets in the strict sense.118 Elijah and Elisha function most of the time as miracle-workers rather than mediators of divine messages, and this is also true for Elisha’s apprentices called “sons of the prophet” (bĕnê han-nĕbî’îm).119 In the books of Chronicles, the prophets also act as scribes, recording the acts of the kings of Judah;120 even this can be considered as an act of divination in the context of Chronicles where the written product may be called “prophecy” (nĕbû’â) or “visions” (ḥăzôt)121 as if the history itself was an omen to be interpreted.122

The social status of biblical prophets is often seen as more or less marginalized because of their cultic and social criticism, and there is some truth to this image when we look, for instance, at a figure like Jeremiah who is indeed portrayed as being persecuted by his fellow Judeans.123 On the other hand,many prophets are presented as having easy access to the king and the court. Moreover, the compound “priests and prophets,”124 often supplemented with rulers, officers, and other leaders of the people,125 brings the prophets close to the realm of the priests and makes them appear as a part of the socio-religious establishment of the society, however critical a stance the text takes on it.126 A few times prophets appear together with other kinds of diviners, showing that prophecy was indeed regarded as another art of divination even by some biblical writers.127

Other designations used for persons whose activity more or less corresponds to our definition of prophecy include rō’ê (√r’h,“to see”) and ḥōzê (√ḥzh,“to see, to have a vision”), both translated as “seer,” as well as ’îšhā’ĕlōhîm “man of God.” These words have fewer occurrences, but are used for persons involved in activities similar to those of the nābî’. Sometimes more than one of the above designations are parallelized or used for one and the same person, which causes their sematic fields to overlap. The title rō’ê has not much of an independent existence, since it is only used for two persons—Samuel, who is also called a nābî’, and Hanani128—and the plural form occursonce as a poetic parallel of ḥōzîm.129 The title ḥōzê, again, appears as a designation of a prophet especially in Chronicles where Gad, Heman, Iddo, Jehu, Asaph, Jedutun, and an anonymous prophet carry this title;130 elsewhere, it is used for Gad, David’s seer, in 2 Sam. 24:11, and for Amos by the priest Amaziah in Amos 7:12. In addition, ḥōzê occurs several times as a synonymous parallel of nābî’.131

The limited number of occurrences and the close semantic proximity to nābî’ makes it very difficult to define independent semanticfields for rō’ê and ḥōzê.132 The “man of God” (’îšhā’ĕlōhîm) is more common but has a somewhat different character. This title, used even for Moses and David,133 “denotes a close relationship between a human and a deity”134 often materializing as the use of superhuman power, but also in speaking on behalf of God. Bearers of this title include Samuel, Shemaiah, Hanan son of Igdaliah, five anonymous characters,135 and especially Elijah and Elisha, in whose activity the prophetic transmission of the divine word coexists with miracle-working.136

The Hebrew Bible consists of material accumulated during several centuries; hence it can be assumed that the meanings of the prophetic vocabulary have undergone transformations which, however, are extremely difficult to track down. This makes it difficult to identify historical developments of the prophetic phenomenon in early Israel and Judah on the basis of terminology. Certain vocabulary is used by some texts more than by others,137 and texts deriving from different periods may have different nuances for each term. This is recognized even in the biblical text itself: “Formerly in Israel, anyone who went to inquire of God would say, ‘Come, let us go to the seer’; for the one who is now called a prophet (nābî’) was formerly called a seer (rō’ê)”(1 Sam. 9:9). Knowing this, however, is not especially helpful for the modern reader, who must ask: “If a nābî’ was a rō’ê, what then was a rō’ê?”;138 when was “now,” and who is talking?

All this means that what we can study in the first place is the image of the prophets drawn by a variety of biblical writers—constructions that are very reluctant to let historical developments and circumstances shimmer through. Biblical constructions do not form a unified whole, which probably reflects the multifarious nature of the historical phenomenon.139 What they reveal is, first and foremost, that non-technical divination was an integral and important method of divine–human communication in the societies where the texts of the Hebrew Bible emerged, that is, the kingdoms of Israel and Judah and the Persian province of Yehud. According to the biblical constructions, a prophet—mostly called nābî’, sometimes ḥōzê or rō’ê140—is a diviner whoseperformance is believed to be inspired by God, whose divinatory methodology is predominantly intuitive and who, therefore, corresponds well to the definition of prophecy presented above. The prophet is recognized as another type of practitioner of divination in the biblical text; however, there is a strong ideological tendency in the historical and prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible to make a sharp distinction between true and false prophets and to prohibit most methods of technical divination, which doubtless existed in ancient Israel and Judah but are very difficult to reconstruct.

The dominance of the term nābî’ over other designations is probably dueto a historical development referred to already in 1 Sam. 9:9, and it is possible that this title is attached to some biblical prophets only secondarily.141 One indication of this is the frequency of nābî’ as the title of Jeremiah in the Masoretic Hebrew text as compared to the much less frequent use of prophētēs as his title in the Septuagint translation which is based on a shorter and, as most scholars agree, older Vorlage.142 In later texts, the word nābî’ clearly becomes the technical term for prophecy, and not only that, but its semantic field broadens towards an honorific title, denoting a special relationship with God or god-given authority and wisdom rather than intermediation in the first place.143 The title nābî’/prophētēs begins to be used not only of the prophets but also other important forefathers and leading figures. Jesus Sirach uses the title also of Joshua and Job,144 and the book of Tobit counts even Noah and the patriarchs Abraham, Izaak, and Jacob among the prophets.145 On the other hand, contemporary persons who would well deserve to be called prophets according to our definitions, such as the Teacher of Righteousness in the Dead Sea Scrolls,146 never carry this title which seems to have become reserved for the prophets of old. Perhaps for the same reason, Daniel is never called a prophet in the book of Daniel.147

Turning now to the Mesopotamian colleagues of the Greek and biblical prophets, we may start with the observation that the commonest Mesopotamian prophetic designation is derived from the verb maḫû “to become crazy, to go into a frenzy,” which, like the Hebrew root nb’, denotes ecstatic comportment and especially receiving and transmitting divine words in an altered state of consciousness.148 The noun derived from this verb appears in both masculine and feminine forms, muḫḫûm (masc.)/muḫḫūtum (fem.) in Old Babylonian texts149 and maḫḫû (masc.)/maḫḫūtu (fem.) in Middle Babylonian,150 Neo-Assyrian,151 Neo-Babylonian,152 and Late Babylonian153 texts. In Old Babylonian texts, muḫḫûm/muḫḫūtum is the commonest prophetic title, whereas in Assyrian texts, maḫḫû/maḫḫūtu appears only in literary texts, in lexical lists, and in a couple of administrative documents.

Many of the carriers of this title appear as recipients of food or other goods in administrative documents154 or act as witnesses in legal documents.155 These texts seldom reveal much of the prophetic capacity of the persons thus designated, but they document their presence in different parts of Mesopotamia and beyond—not only at Mari, but also in Ešnunna, Babylonia, and Syria.156 It becomes abundantly evident from the sources that, regardless of the time and place, the principal environment of the activity of the muḫḫû/maḫḫû was a temple context. They are often identified by the name of adeity,157 they may appear as ritual practitioners,158 the administrative documents present them as part of the temple personnel,159 and the lexical and omen tradition regularly connects them with other cultic performers, such as lamentation singers and other musicians, men–women (assinnu and kurgarrû),and other ecstatics.160

Many texts do not reveal much of the functions of the muḫḫûm/maḫḫû, but there is enough evidence to justify the translation of this designation as “prophet.” The ecstatic element of their ritual performance is presupposed in several texts. They are mentioned together with other ecstatics (male zabbu and female zabbatu) not only in lexical lists but also in one Neo-Assyrian ritual text,161 and their frenzied comportment is alluded to in the Middle Babylonian “Righteous Sufferer” text found at Ugarit: “My brothers bathe in their blood like prophets.”162 Another poetic text, a Neo-Assyrian prayer to Nabû, also hints at an altered state of consciousness: “I have become affected like a prophet: what I do not know I bring forth.”163

The verse from the prayer to Nabû implies what the ecstasy of the maḫḫû is all about: it serves the purpose of bringing forth things unknown in an altered state of mind. The transmissive function is evident virtually always when anything is said about their goings-on. In the letters from Mari, the muḫḫûm or muḫḫūtum regularly conveys a divine message either in the temple of his/her tutelary deity or coming to a person who writes about the divine message to king Zimri-Lim.164 In Neo-Assyrian inscriptions, prophecies are referred to as šipir maḫḫê našparti ilāni u Ištar,“reports of the prophets, messages from the gods and Ištar.”165

Only in a couple of cases is the mediatory function of the maḫḫû not immediately evident. It is not quite clear what the prophets and prophetesses, together with other male and female ecstatics, actually perform at the bed of the sick person in the Neo-Assyrian ritual of Ištar and Dumuzi (*118), and the ritual duties of the prophet in the Neo-Babylonian ritual text from Uruk (*135o) include ritual circumambulation and carrying a water-basin, but neither prophesying nor ecstatic behavior is mentioned here. These exceptions, however, hardly justify the conclusion that the prophetic role of the muḫḫûm/maḫḫû is secondary to their ecstatic function;166 it is difficult to see what purpose other than prophesying their ecstasy would have served. Intermediation of divine messages is the principal aspect of what the muḫḫûm/maḫḫû do, whether or not in a state of frenzy, in almost all of the sources that indicate anything at all about their activity.

In addition to muḫḫûm, the texts from Mari use frequently another designation, āpilum (fem. āpiltum167) for persons involved in prophetic activities.168 The word is derived from the root apālu “to answer”and is often understood as denoting a transmitter of divine answers to human inquiries. In the available texts, however, the oracles delivered by an āpilum do not appear as responses to oracle questions. The etymology allows for better translations such as “interpreter”169 or “spokesperson.”170 The āpilum typically conveys divine messages in the very same manner as does the muḫḫûm. The performance of an āpilum, like that of a muḫḫûm, may take place in a temple,171 but this is not always the case—one letter reports on the proclamation of an āpilum of Marduk at the gate of the royal palace in Babylon,172 and many times a prophet is said to have“come”to the letter-writer without indicating where this took place. Many times an āpilum, like the muḫḫûm, is associated with a specific deity,173 but it is difficult to know whether this also implies an affiliation with a specific temple.

The titles āpilum/āpiltum and muḫḫûm/muḫḫūtu mare never used forone and the same person in the available documents, hence there must have been a reason for two different prophetic titles at Mari. Serious attempts have been made to figure out a functional difference between these two groups of prophets. It has been suggested that the trance of an āpilum was actively provoked, unlike that of the muḫḫûm which was passively received and spontaneous,174 but the evidence is ambiguous at best, since an āpilum is never actually caught in the very act of provoking an altered state of consciousness. References to the altered state of mind of an āpilum/āpiltum were not available until the publication of the previously unknown passage belonging to the fifth tablet of the Epic of Gilgameš, in which Enkidu and Gilgamešare approaching the cedar forest to kill the demon Humbaba. Enkidu says to Gilgameš:

“My [fr]iend knows what a combat is,

he who has seen the battle has no fear of death!

You have been smeared [with blood], you have no fear of death!

[Be] furious, like a prophet (āpilum) g[o into a f]renzy!175

Let [your] s[hout] boom loud [lik]e a kettledrum!

[Le]t stiffness leave your arm, let debility depart [from] your [l]oins!”176

At the very least, this passage of the Standard Babylonian Epic of Gilgameš, dating to the Neo-Babylonian period, suggests that the altered state of mind belonged to the social memory concerning the āpilum.177

It seems that an āpilum was freer to move from one place to another, whereas the activity of a muḫḫûm/muḫḫūtum was more restricted to the temple to which he or she was affiliated.178 While this is not an absolute rule either, we may notice that theāpilum, unlike the muḫḫûm, may be commissioned by the king to specific tasks, like Lupaḫum, the prophet of Dagan who is sent to Tuttul and Der, and he comes with divine messages from both places.179 Moreover, an āpilum, unlike any of the muḫḫûm’s known to us, can be found actively involved in writing down the divine message he has received for the king.180 While this evidence is hardly enough to make the āpilum a court official, it may be taken as an indication that the position of the āpilum was closer to the royal court than that of the more temple-bound muḫḫûm. In general, the activity of both classes is described in a similar way, and there is not enough evidence to make a clear difference between their job descriptions, much less to make a wholesale distinction between the āpilum/āpiltum as a professional prophet and the muḫḫûm/muḫḫūtum as a“lay-prophet.”181 As much as can be seen through the keyholes provided by the preserved sources, both groups show themselves to belong to a prophetic institution which had an established position in the society of Mari.

However professional, the āpilum/āpiltum and the muḫḫûm/muḫḫūtum were not the only ones acting as mouthpieces of deities at Mari. Prophecies can be uttered by private—especially female—individuals, whether a servant girl or a free citizen’s wife.182 In a number of documents, people belonging to neither of the two groups transmit divine messages. One of them is called anonymously “the qammatum of Dagan of Terqa, ”whose message was significant enough to be reported independently by two or three different letter-writers.183 There is no question of the prophetic role of this female person, but the title is hardly a standard prophetic designation. The word qammatum is of unclear derivation. If not a proper name,184 it may refer to a person with a characteristic hairstyle.185

Two persons called assinnu, translatable as “man-woman” because of their atypical gender characteristics,186 appear several times prophesying at Mari.187 While assinnu is not a prophetic title as such,188 their prophetic function is significant with regard to the repeated appearance of prophets grouped with assinnu in lexical and administrative lists.189 Finally, people called the nabûm’s of the Haneans are made to deliver an oracle to the king of Mari.190 The word nabûm may be etymologically related to Hebrew nābî’.191 The performance of the persons thus designated is broken away, but what is left of the oracle question may suggest a binary form of an answer, hence leaving the door open to interpret their activity as technical divination rather than prophecy.

In Neo-Assyrian sources, the standard word for a prophet is raggimu (fem. raggintu), a noun derived from the verb ragāmu “to shout, to proclaim,” which is used for prophesying.192 The noun raggimu/raggintu is virtually exclusively Neo-Assyrian,193 according to Simo Parpola “a specifically Neo-Assyrian designation of prophets replacing the older maḫḫû, which was retained as a synonym restricted to literary use.”194 This assumption is corroborated by the rather genre-specific use of the two terms: maḫḫû/maḫḫūtu can be found inroyal inscriptions and poems as well as cultic text, omens, and lexical texts from the Neo-Assyrian period,195 whereas raggimu/raggintu is the word used in letters and the colophons of the prophetic oracles which reflect better the Neo-Assyrian vernacular.196 In administrative documents, both raggimu and maḫḫāte (fem. pl.) have a single occurrence.197

Only once can the two terms be found in juxtaposition, and this is the casein the Succession Treaty of Esarhaddon: “If you hear an evil, ill, and ugly word that is mendacious and harmful to Assurbanipal (…), may it come from the mouth of (…) a raggimu, a maḫḫû, or an inquirer of divine words, (…) you must not conceal it but come and tell it to Assurbanipal (…).”198 This has been explained in two ways, either regarding the words as synonyms199 or as a reference to three different classes of diviners.200 Both explanations have their problems. A cluster of synonyms is suspicious because other people mentioned in the same paragraph (that is, family members) cannot be understood as synonyms; however, this single text gives hardly enough reason to consider raggimu and maḫḫû strictly different coexisting classes of prophets either.201 In my view, the sources do not endorse such a dichotomy, since both the raggimu/raggintu and the maḫḫû/maḫḫūtu are presented as speakers of oracles to the king202 and both appear in temples and in ritual contexts.203 The former are presented as communicating with the king more often than the latter, but this is to be expected because the raggimu/raggintu appear in oracles and letters addressed to the king. On the other hand, the maḫḫû/maḫḫūtu are more often associated with ecstasy, mainly because of the preference for the word maḫḫû/maḫḫūtu in lexical texts and omens.204 The ecstatic comportment of a raggimu/raggintu is not described anywhere, but it would be too hasty to conclude that “there are no indications that the raggimu delivered oracles in an ecstatic state,”205 since the verb ragāmu may carry this connotation in itself.