The range of contexts in which such name-dropping might occur.

By Dr. Ewen Bowie

Emeritus Fellow in Classics

Corpus Christi College

University of Cambridge

Introduction

The great battles of the early fifth-century Persian Wars were remembered and discussed in many different contexts by the Greek πεπαιδευμένοι of the Roman empire. Doubtless some could say more about them than others, and according to Dio of Prusa there were those who held that Salamis was fought later than Plataea.1 But whether one was a man from mainland Greece or western Asia Minor, a man from Tarsus or Naucratis or the Roman province Syria, or even not quite a man from Arelate in the Rhone valley, like Favorinus, the names Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea, and sometimes the names Artemisium, Thermopylae, Mycale, and Eurymedon, could be used to decorate one’s discourse and flaunt one’s philhellenism.

Part of my purpose in this paper is to give an idea of the range of contexts in which such name-dropping might occur. But I also suggest that by the 150s AD we find Marathon cited much more often, proportionately, than in earlier years, and that this pre-eminence may be due to the most influential citizen of the Attic deme Marathon in the period, L. Vibullius Hipparchus Ti. Claudius Atticus Herodes – simply Herodes to his friends and pupils. It may of course be doubted whether we have enough evidence to do a poll of the relative popularity of Persian War battles in the first and second centuries AD: often particular reasons can be found in the literary context for the mention of one battle rather than another. So my idea that Marathon became the leader of the pack from around AD 150 may be a mirage. But the interest of Herodes Atticus, with which I shall conclude, is hard to deny.

First, some pre-history: in the later first century BC, we can see a relatively even-handed treatment, as befits a historian, in the account of Diodorus of Agyrrhium in Sicily: Marathon ends his Book 10, then Artemisium, Thermopylae, Salamis, Plataea, Mycale, and Eurymedon are narrated in his Book 11. Later in the same century Dionysius of Halicarnassus’ only primary citation mentions all four Athenian battles, Marathon, Artemisium, Salamis, and Plataea, this in his discussion of whether λόγοι ἐπιτάφιοι can be traced earlier in Greece or in Rome.2 Dionysius’ omission of Thermopylae is simply because Athenians were not involved.

With Strabo of Amaseia’s Geography we come nearer to a work that might give us a glimpse of a plain but hard-thinking man’s priorities. Marathon gets only one mention: listing Attic demes as one sails up the north-east coast of Attica, Strabo notes Marathon as the place ‘where Miltiades utterly destroyed the forces with Datis the Persian without waiting for the Spartans, who were late because of the full moon’.3 By contrast Salamis gets two mentions – later in book 9, where the temple of Aphrodite Kolias is noted as the place the wrecked ships of the Persian fleet washed up, and earlier in book 8 when Strabo notes that Aegina contested with Athens the prize for fighting at Salamis.4 Plataea also gets two mentions, first a general statement about war damage in 479 BC,5 then a more detailed statement (Strabo 9.2.31):

Here the Greek forces utterly annihilated Mardonius and his 300,000 Persians; and they established a sanctuary of Zeus Eleutherios and declared a stephanitic athletic competition, calling it the Eleutheria. And there is displayed the public tomb of those who died in the battle.

This is more than Strabo tells us about Marathon, where we know from other sources, but not from Strabo, that Athenian ephebes brought ritual offerings.

Finally in Strabo Thermopylae merits three mentions. The importance of geographical knowledge is illustrated by the treachery of Ephialtes;6 the elegiac couplet on one of the five inscribed στῆλαι by the πολυάνδριον at Thermopylae is quoted for the status of Opous;7 and finally Strabo contrives to introduce the story of Leonidas’ Spartans combing their hair into a digression about men wearing women’s clothes and giving attention to their hairstyle.8 Strabo does not mention the battles at Artemisium or Eurymedon, and of Mycale he says only that the mountain is εὔθηρον καὶ εὔδενδρον, ‘well-forested and good for hunting’.9

The next decades are not ones for which surviving and dated Greek texts are numerous. But courtesy of the Garland of Philip we have some relevant poems from Lollius Bassus, active perhaps around AD 19, and Tullius Geminus, consul suffectus in AD 46 and legatus Augusti of Moesia in the early 50s. Of Lollius Bassus’ dozen poems in the Garland of Philip two handle Thermopylae,10 while from Tullius Geminus we have an epitaph for Themistocles in which he is the speaker and names Hellas, Persians, Xerxes, and Salamis as well as himself,11 and a poem ostensibly for a monument to the battle of Chaeronea which into its speech packs Cecrops, Philip, Marathon, Salamis, Macedonia, and Demosthenes.12

This even-handedness between Marathon, Thermopylae, and Salamis also emerges in two utterances by characters in Chariton’s Chaereas and Callirhoe, a work known by the early 60s AD.13 First play is made by Callirhoe, seeing off the eunuch Artaxates, with Chaereas’ city Syracuse having defeated Athens, the victor of Marathon and Salamis (Chariton, Chaereas and Callirhoe 6.7.10):

Chaereas is of noble birth, the first citizen in a city which was not even defeated by the Athenians, who defeated your Great King at Marathon and Salamis.

Later, when Chaereas himself gathers precisely 300 Greeks to storm Tyre, he underlines the numerical allusion to Thermopylae for any slow-witted reader (Chariton, Chaereas and Callirhoe 7.3.9):

For we shall find it to be possible and easy, more difficult in expectation than in experience. This was the number of Greeks who resisted Xerxes at Thermopylae – but the Tyrians do not number five million.

Dio and Plutarch

The decades from the 60s AD to the early second century are much richer, being those during which Dio of Prusa and Plutarch of Chaeronea composed.

In Oration 73 (de fide), tackling the subject of the Athenians’ harsh treatment of Themistocles, Miltiades, and Cimon despite their achievements fighting Athens’ enemies, Dio succeeds in referring unambiguously to the battles of Marathon, Salamis, and Eurymedon without using these toponyms.14 In Oration 56 (Agamemnon) he sets out Sparta’s comparable ill-treatment of Pausanias, again without naming Plataea.15 In a more playful mood, in his Oration 11 (Trojan), Dio alleges disputes over the relative chronology of Salamis and Plataea and offers a version he claimed to have heard from a Mede:16 Datis was sent to deal with Naxos and Eretria, and was returning, mission accomplished, when some of their ships, no more than twenty, drifted towards Attica and there was a skirmish with the natives. Then in his expedition against Greece Xerxes defeated the Spartans at Thermopylae and killed their king Leonidas, destroyed Athens, and enslaved any Athenians who had not fled. End of story.

For Plutarch the Persian Wars furnished important episodes for his fifth-century Athenian Lives. As John Marincola pointed out in a recent paper which he has generously allowed me to see,17 Plutarch is especially interested in showing the benefits of harmony and concession-making between the leading Greek politicians, and the extent to which personality and oratorical skills were able to help them persuade the dēmos. These targets, and that of showing off each leader’s personal capacities in the best possible light, make a major contribution to Plutarch’s trimming and slanting of episodes. Nothing emerges that would allow us to decide which battle, if any, Plutarch thought most important. Since Plutarch wrote no Miltiades there is no full account of Marathon: that battle appears chiefly in the Aristides, with most attention to Aristides the στρατηγός giving up his day of supreme command to Miltiades and thus persuading the other στρατηγοί to do the same; to his fighting alongside Themistocles, each at the head of their φυλή; and to his scrupulous guarding of the captured Persian treasure.18 Marathon turns up elsewhere as iconic: Themistocles’ ambition is fired by Miltiades’ achievement;19 the Athenian forces at Plataea recall Marathon and Salamis;20 people mention Marathon to encourage the rising Cimon.21 When we turn to the Roman lives, in his Camillus Plutarch shows interest in the battle’s exact date (6 Boedromion) and in his Flamininus he notes it as among the few great battles of Greek history that were not internecine. The other such battles were indeed all fought in the Persian Wars – Salamis, Plataea, Thermopylae, Eurymedon, and Cimon’s Cypriot campaign (in that order).22 Finally in the Theseus we get a detail that would doubtless have enhanced a Life of Miltiades had one been written: during the battle a φάσμαof Theseus was seen hurling itself against the βάρβαροι.23

It is clear, however, from his other worksthat Plutarch had more material that he couldhave offered on Marathon had he so decided. In the On the ill-will of Herodotus, for example, unpicking Herodotus’ account, Plutarch castigates his silence on the establishment of the festival of Artemis Agrotera, a ritual still performed in his day, ἔτινῦν;24 he also pretends to doubt, and attempts to demolish, the story of the Spartans waiting for full moon – rather, he suggests, the Athenians did not send for them until they had won their victory;25 moreover he rubbishes the shield story, claiming that it is an attempt by Herodotus to discredit the Alcmaeonids.26 There are also more details in de gloria Atheniensium: for example, again a mention of the festival of Artemis Agrotera (unless a different commemoration is meant).27 Both these works, however, mention most other battles too – de gloria Atheniensium Artemisium, Salamis, Mycale, and Plataea at one point, Salamis and Eurymedon alongside Marathon at another.28 The comparison of Aristides and Cato notes that Aristides was in all three of Marathon, Salamis, and Plataea.29 Non posse suaviter is unusual in mentioning Marathon twice, once together with Plataea, once with together Salamis.30

For Salamis Plutarch naturally grasps the opportunity for a very full narrative in the Themistocles.31 But Salamis appears repeatedly elsewhere too, especially of course in the Aristides, with Aristides sailing from Aegina through the Persian fleet and going to Themistocles’ tent to urge cooperation, and with his effective military action on the island of Psyttaleia.32 In other contexts Plutarch tells of the alleged sacrifice of young Persian princes to Dionysos ὠμηστής before the battle,33 and shows interest and apparently indecision on its date – around 20 Boedromion according to the Camillus, 16 Mounichion according to the Lysander.34 In his Cimon Plutarch has a nice anecdote about Cimon’s response to Themistocles’ Salamis decree having been to dedicate a horse-bridle on the Acropolis, and in his account of Eurymedon he judges that this victory trumps both Salamis and Plataea because on one day Cimon was victorious both in a sea and in a land battle.35 Finally the participation of Phayllus of Croton, known from Herodotus (8.47) and, as I have recently argued,36 remembered by Alexander the Great, who sent a share of his spoils to Croton.37 To say nothing of the dog – the famous story of Xanthippus’ swimming dog.38

Plataea too is given a full account. It constitutes the major military panel of the Aristides, starting with Aristides leading 8000 Athenian hoplites to Plataea and continuing for ten chapters, with a later reference back in the context of Pausanias’ recall.39 It is not surprising that this is the battle where the Boeotian Plutarch shows greatest interest in local topography, and indeed some delicacy in blaming the ‘medism’ of some Boeotians on their leaders. He repeats the tradition that Plataea was fought on the same day as Mycale,40 a day he takes to be 3 Boedromion.41

This reference in the Aemilius Paullus and that already noted in de gloria Atheniensium42 are, I think, Plutarch’s only mentions of Mycale: this seems to be the first battle to drop off any list. Artemisium too is given rather little space: it is mentioned in the Themistocles 7-9 and receives a glance in the Alcibiades where we learn that Clinias fought there in a trireme he had equipped himself.43 Eurymedon fares somewhat better, with a predictably adequate account in the Cimon and inclusion in the great battles picked out in the Flamininus as not internecine.44 It is also one of the three battles whose inflammatory evocation Plutarch’s πολιτικὰ παραγγέλματα recommend banishing from political oratory and confining to the schools of the sophist, the other two being Marathon and Plataea.45 It may be that in this work Eurymedon is mentioned partly because its addressee was Menemachus of Sardis and so Plutarch was temporarily adopting an Anatolian mind-set. But Eurymedon is also one of three Persian War battles, alongside Marathon and Artemisium, in de sera numinis vindicta.46

The loser in Plutarch’s overall presentation is perhaps Thermopylae. But then, even if it was a moral victory, it was a military defeat, as Plutarch, narrating the arrival of the bad news at Artemisium in the Themistocles, has to admit.47

Some Second-Century Writers

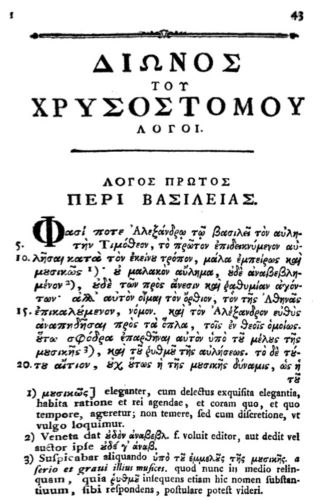

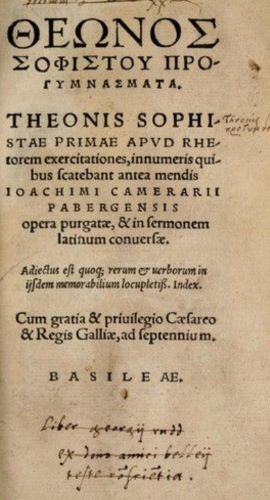

For the quarter century after the latest works of Dio and Plutarch the appearances of Marathon and other battles are too scant to allow useful inferences. The rhetor Theon, if he really belongs around now,48 has no mention of Thermopylae or Mycale, but twice mentions the battle of Plataea in connection with the siege of Thucydides Book 2, and twice mentions Themistocles,49 without naming Salamis, though in the second case the mention of Artemisia’s name guarantees that context. He has two very different references to Marathon: in one he envisages the speech that Datis made on his return to Dareius,50 and in the other he quotes the Philippica of Theopompus as reporting some to have questioned the historicity of the battle of Marathon: ἔτι δὲ καὶ τὴν ἐν Μαραθῶνι μάχην οὐχ ἅμα πάντες ὑμνοῦσι γεγενημένην.51

Longinus touches on the Persian War battles only in relation to Demosthenes’ invocation of Marathon, Salamis, Artemisium, and Plataea – only, of course, ones in which Athens was involved.52

I move on, therefore, to writers in the second half of the second century. First, Appian of Alexandria has only one reference to the Persian Wars in his Roman History, when in his Hannibalic book he refers to the small city of Plataea aiding Athens, a reference to their aid in the battle of Marathon.53 Second, the rhetor Hermogenes of Tarsus, writing around AD 180, has five references to Marathon. In one of these Marathon is part of a threesome – Marathon, Plataea, and Salamis.54 This is Hermogenes’ only reference to Plataea and Salamis. Hermogenes’ other four references (admittedly three of these in a single sequence, and all involving citation of Demosthenes’ oath: ‘by our ancestors who faced danger for their city at Marathon’) are to Marathon alone.55 This is perhaps striking for a boy from Tarsus, even if he is working in an Athenian environment. Again in Maximus of Tyre Marathon gets several mentions, the other battles each either one or none.56 What has happened to promote Marathon to this extent? Has indeed Marathon been promoted? Some figures from intervening years suggest that it has.

Aelius Aristides

First, Aelius Aristides’ apportionment of his always copious rhetoric in his Panathenaicus of AD 155. The main section dealing with the battle of Marathon (104-10) is shorter than that dealing with Salamis (135-72). Neither is straight narrative: rather it is an argumentative meta-narrative which assumes that the audience knows all the basic facts. But in these two meta-narratives the shadow of Marathon is longer. We initially encounter Marathon at 13: here was the first Persian landing. At 63 a brief comment about the Marathonian τετράπολις being given to the Heraclidae says nothing of the battle. After the section pirouetting around the battle itself, 104-10, we hear at 114 that Dareius was at a loss, became enraged, and collapsed, dying before a second invasion could be launched. Xerxes then demanded expiation for Marathon (117) where, we are reminded (126), Athens stood alone – a point repeated at 167: in neither case are the Plataeans mentioned at all. Shortly Aristides compares Thermopylae disparagingly with Marathon: at Thermopylae some fled, others who stayed perished ineffectively (131). Much later we hear that the exiles at Phyle almost surpassed the fighters at Marathon, implying that the latter constitute the gold standard. Finally at 347 Aristides awards his prizes: Athens’ top land battle, Marathon; Athens’ top sea battle, Salamis; Athens’ top cavalry battle, Mantinea.

The battle of Salamis does indeed do well in the Panathenaicus, with a long close-up from 135 to 172. But there are fewer other mentions: 347 (just cited), 128, 180, 231. Artemisium and Plataea tie for third position: Artemisium is mentioned at 128 and 160, and its outcome is contrasted with the failure at Thermopylae at 167; Plataea is mentioned at 172 and 190, and a very short account of the battle itself is offered at 182-83. Mycale (198) and Eurymedon (202-03) each get only one mention.

The proportions are similar in Oration 3, On behalf of the four, but the fact that Miltiades, Themistocles, and Cimon are three of the four naturally requires special attention to Marathon, Salamis, Plataea, and Eurymedon. The Marathon sequence here includes references to the aid of Pan and Heracles (191), the establishment of Pan’s cult (191) and the arrangements for the burial of the fallen (196).

Other Witnesses

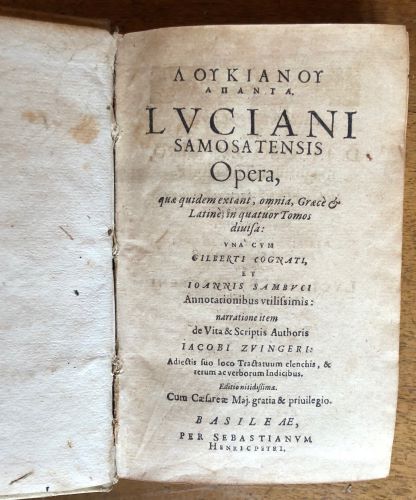

My next witness, with more substance and humour, is Lucian. Only once does Lucian mention Artemisium, Thermopylae, and Plataea: giving advice on declaiming in Athens in Teacher of rhetors the speaker says (Luc. Rh. Pr. 18):

On every occasion bring in Marathon and Cynegirus – without them nothing would be successful. Always have Athos being sailed through and the Hellespont crossed on foot and the sunlight cut off by Median missiles and Xerxes fleeing and Leonidas being admired and the letter of Othyradas being read,57 and Salamis and Artemisium and Plataea – many of these events and often.

Note that here Marathon heads the teacher’s catalogue. Apart from this mention of Salamis there are only two others in Lucian. One is indeed not nominatim to Salamis, but to Themistocles and Miltiades ‘suspected of betraying Greece after such great victories’.58 The second is in his Tragic Zeus: Zeus observes that it is predictable that men pay no attention to gods since there have been ambiguous oracles like that to Croesus (concerning the Halys) and (Luc. JTr. 31):

O divine Salamis! You will destroy the children of women.

A little later in the dialogue Zeus’ rejection of Heracles’ proposal to zap the Epicurean Damis brings in the battle of Marathon (Luc. JTr. 32):

ZEUS: Heracles, by Heracles, this is peasant talk, terribly Boeotian, to destroy so many good men along with a scoundrel, and in addition the Stoa, along with Marathon and Miltiades and Cynegirus. With their collateral destruction how could the rhetors perform their rhetoric any longer, once deprived of the most important theme for their speeches.

This is an interesting if jocular testimony to the prominence of Marathon in epideictic oratory in Athens, something corroborated by a detail in Philostratus’ Lives of the sophists: Ptolemy of Naucratis, a pupil of Herodes, had the nickname Marathon, either, Philostratus suggests, because he was enrolled in that deme, or because in his epideictic performances with an Athenian setting he often mentioned those who had risked their lives at Marathon.59

Marathon, as we have begun to see, is also prominent in Lucian’s own work. The tradition of Pan’s assistance appears three times. Perhaps it could hardly be avoided in Dialogues of the gods – what else would an Attic Pan say (Luc. DDeor. 2.3)?

I also rule over all Arcadia: and the other day I also fought alongside the Athenians at Marathon and was so far the best fighter that the cave under the Acropolis was actually chosen for me as my prize.

This tradition of Pan’s help is also brought in by Hermes speaking in Twice accused (probably written around AD 166) and mocked by Tychiades in Lovers of fictions 3.60 Finally in a latish work, In defence of a mistake in greeting, Lucian retells the story of (in this version) Philippides running from Marathon to bring news of the victory to the ἄρχοντες and dying as he uttered the word χαίρε<τε>.61

My last witness is Pausanias. Pausanias indeed mentions all the battles of the Persian Wars, often of course in connection with dedications by the Greek victors, but also in his review of great men whose military actions had benefited Greece as a whole. That list includes Thermopylae, Artemisium, Salamis, and Plataea. It also mentions Mycale and Cimon’s eastern campaigns. But it is headed by Miltiades (Paus. 8.52.1-3):

For Miltiades the son of Cimon defeated in battle those of the barbarians who had landed at Marathon and halted the Median expedition from advancing further: he was the first common benefactor of Greece.

Book 10 has some mentions of Thermopylae, but all these are comparanda embedded in the narrative of the Gallic invasion on which Pausanias here lavishes his writing skills. Books 9 and 10 offer several details about Plataea and consequent dedications, but Artemisum, Mycale, and Eurymedon only figure in connection with dedications, and even Salamis gets only cursory mention, e.g. when Themistocles is said to have been αἴτιος of the victory or when Pausanias’ tour takes him to Psyttaleia, though with no mention of Aristides.62 But neither get the close focus that Marathon receives in Pausanias’ description of the paintings in the Stoa Poikile,63 or that the battlefield and soros receive a little later in Book 1.64 Indeed Pausanias seems to share the privileging of Marathon he attributes to the Athenians, noting that despite also fighting at Artemisium and Salamis Aeschylus only mentioned Marathon in his sepulchral epigram (Paus. 1.14.5):

And still further on is a temple of Eucleia, it too a dedication from the Medes who attacked the country at Marathon. And I reckon that the Athenians feel the greatest pride in this victory. Indeed Aeschylus, when the end of his life was expected, recalled none of his other achievements, despite having acquired such a reputation for his poetry and having fought at Artemisium and at Salamis: he wrote his name, and his father’s and that of his city, and that he had as witnesses of his bravery the grove at Marathon and those of the Medes who landed there.

A Wind of Change?

Has there, then, been a change during the second century in the relative importance of the Persian War battles? By the AD 150s, I think, Marathon has become discernibly more prominent. This may be due to the number of our sources that reflect the priorities of epideictic rhetoric, together with the Attic focus, or mis-en-scène, of these sources. Sophistic performances in Sparta or Pamphylia may have privileged Thermopylae and Eurymedon respectively, just as we may be confident that when P. Anteius Antiochus of Aegeae was honoured at Argos his performances there invoked Argive victories and not those of Athenians or Spartans in the Persian Wars.65 We must also recall that already before his death c. AD 150 the great sophist M. Antonius Polemo devoted a pair of declamations to Callimachus and Cynegirus.

But, as I have said, I think another factor is at work – Herodes Atticus’ interest in his own deme Marathon.66 That interest is attested archaeologically by the inscriptions from the gate of the villa he developed jointly with his Italian wife Regilla, the sculptures of the couple and the imperial family still visible in the museum, and the temple of the Egyptian gods down by the shore – Philostratus’ τὸ τοῦ Κανώβου ἱερόν (‘the sanctuary of Canopus’) – where, like Lucius at Cenchreae in Apuleius’ Metamorphoses, Herodes could see the moon rise over the sea to the east and fancy that she was Isis.67 Herodes enjoyed spending time at Marathon, and Philostratus narrates how his pupils would escort him around Cephisia and Marathon, much as certain modern professors move about surrounded by bevies of graduate students (Philostr. VS 2.1.562):

For after the events in Pannonia Herodes spent his time in Attica in his favourite demes, Marathon and Cephisia, escorted by young men from all over, who would come to Athens out of desire for his eloquence.

It is Marathon whose delight at Herodes’ return is asserted by the long elegiac poem composed to welcome him on his return from exile after the emperor Marcus had brokered a deal with his enemies in Athens.68 It was on the hill route between Cephisia and Marathon across the slopes of Pentelicon that he seems to have had his encounters with the unspoilt, Atticizing child of nature, Heracles-Agathion. It was in Marathon that Herodes wanted to be buried.69 Moreover Herodes claimed descent from Miltiades and Cimon, calling one of his own daughters Elpinice.70

Now we know that even away from Attica Herodes remembered Marathon. At his villa at Loukou he had there at least one stele relating to Marathon. The stele that survives almost complete, published in 2009 by Giorgos Spyropoulos, bears across the top the name of the Athenian tribe Erechtheis, next a four-line elegiac epigram, then below twenty-two names – the names of ‘these men’ (τῶνδ’ ἀνδρῶν) invoked at the beginning of the epigram’s second line – all in early fifth-century letters. Further work has been done on the text of the epigram by Steinhauer.71 I remain unconvinced that the first line has been solved, but this chapter is not the appropriate place to discuss possible readings. What is important is that there are also fragments of a second similar stele, not from parts that would have been inscribed. This suggests, or at least raises the possibility, that in the display hall from which they and some pieces of sculpture seem to have come Herodes had on show a complete set of ten stelai, phyle by phyle, bearing epigrams commemorating the Marathon dead. It is hard not to think that these are the stelai that Pausanias saw encircling the soros, also commemorating the Marathon dead phyle by phyle.72 I do not doubt this claim of Pausanias, and it does not conflict with the discovery of the stelai at Loukou. Pausanias’ account of the soros is in his earliest book, Book 1, written in the later 150s:73 Herodes still had more than a decade of active life in which he could have decided to move the stelai from the plain of Marathon, much of which he owned, to his Cynourian villa. It is also possible, of course, that the stelai at Loukou are copies: some petrological work on the stone might help to resolve that question. In either case Herodes’ attachment to his deme Marathon is further demonstrated.

Let me return very briefly to two sophistic witnesses in whose eyes Marathon seems pre-eminent, Aelius Aristides of Hadrianoutherae and Ptolemy of Naucratis. Both these sophists are said by Philostratus to have studied with Herodes.74 It is not surprising if Herodes’ preferences are reflected in theirs. Herodes was also important in a different way for Lucian: some of Lucian’s cynic satire seems to have Herodes in its sights, in particular the juxtaposition of property-holding in Marathon and in Cynuria in his Icaromenippus 18.75 I suggest that Marathon’s lead over other Athenian Persian War victories in the years after AD 150 reflects the preferences of a man who was Onassis, Levendis, and Niarchos all rolled into one, L. Vibullius Hipparchus Ti. Claudius Atticus Herodes.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Contribution (241-253) from Marathon – 2,500 Years, edited by Christopher Carey and Michael Edwards (University of London Press, 12.02.2013), Institute of Classical Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license.