There are a number of 9th-century cases of projected or actual withdrawal from the world of persons of mature years.

By Dr. Janet L. Nelson

Professor Emerita of Medieval History

King’s College London

In 1970, Christopher Brooke published two papers that for this reader at least were intellectually life-changing: in one, on ‘Historical writing in England between 850 and 1150’, he pointed out, inter alia, the dependence of Asser’s biography of Alfred on the Lives of Louis the Pious by Thegan and the Astronomer; in the other, his presidential lecture to the Ecclesiastical History Society on ‘The missionary at home: the church in the towns 1000–1250’, Christopher compared the ‘worker priests’, that is, the secular clergy, in late Anglo-Saxon towns with the early friars, alike engaged in the work of conversion ‘by infiltration and example’.1 In 1989, Christopher published The Medieval Idea of Marriage which has ever since been a mainstay of my M.A. teaching on medieval religion and medieval women.2 That book was dedicated, with exquisite aptness, to Rosalind. And I cannot resist mentioning another mainstay-book which Christopher and Rosalind wrote together: Popular Religion in the Middle Ages: Western Europe 1000–1300.3 Note the time-spans covered in all those works – here you can see confident traversing of the divides between laypeople and professional religious and between earlier and central medieval periods. In deciding to talk this morning about a variant of conversion in the ninth century, I was encouraged by the thought that no medieval age, nor form of conversion, is alien to Christopher. I confess I was encouraged too by the vice-chancellor’s words yesterday about actuarial calculations of academic longevity; and also by Giles Constable’s acknowledgement of the varieties of religious life and the range of people serving God in their own way who could be embraced under the term conversi.4 Renouncing the world in mature years is a pan-medieval phenomenon.

But my paper for Christopher is about the ninth century – where some interesting conjunctures become visible. I begin with a reference in an unexpected place, and I explore the secular contexts for such renunciations. Then I turn to religious contexts, and discuss those gendered female. Finally I bring secular and religious together by extending the picture to include male renunciation.

First then, the reference:

If any one of our faithful men after our death and pierced by love for God and for us (Dei et nostro amore compunctus), wishes to renounce the world (seculo renuntiare), and has a son or kinsman who can be of service to the state (qui reipublicae prodesse valeat), let him be able to pass on his office(s) in a lawful assembly (suos honores … ei valeat placitare), as he thinks fit. And if he wants to live quietly on his own property (si in alode suo quiete vivere voluerit), let no-one [i.e., no state official] presume to put any obstacle in his way, nor require anything from him, except only this, that he go to the defence of the fatherland.5

This is Charles the Bald, king and emperor, about to set off from Francia for Italy in June 877, making arrangements for the welfare of the res publica in chapter 10 of the Capitulary of Quierzy. The text is famous not for the chapter just quoted, but for the one just before it, chapter 9, which provides for succession to countships – allegedly symptomatic of the growing tendency towards the heritability of office that brought down the Carolingian empire, but in fact foreseeing special conditions (si comes obierit [sc. back in Francia] cuius filius nobiscum [sc. in Italy] sit), providing for interim measures to have been taken by the officers of the county and the bishop acting together, and reserving the right of the king, once informed of the situation, to give the county to whomsoever he pleased.6 Chapters 9 and 10 belong together in the fairly obvious sense that they are both concerned with the transmission of office from one generation to the next. That theme in fact hovers over the whole capitulary: Charles the Bald, aged fifty-four, had the possibility of his own demise, and the succession to his own office, very much in mind as he embarked on what was indeed to be his final journey to Italy, 877 the last summer of his life. In chapter 10, however, he envisages that his own death might impel some of his faithful men who have adult sons (or kinsmen) of their own to withdraw from the world into monastic life. It is this renunciation of the world on the part of a man of mature years, a decision termed conversio in other Carolingian texts, whose meaning I want to explore in this paper.

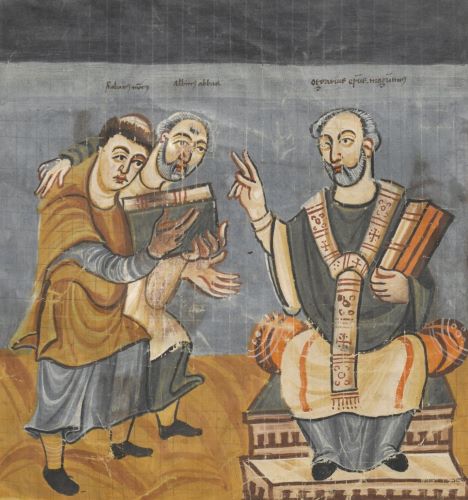

A number of ninth-century cases of projected or actual withdrawal from the world of persons of mature years can be set in the context of familial strategies. The earliest of the ninth-century cases – and I confess it is an atypical one, for reasons which will become clear – is that of Angilbert.7 Born into the high Frankish aristocracy, probably just a few years younger than Charlemagne, and ‘nurtured’ in the palace ‘almost from the rudiments of infancy’, Angilbert prospered at court, in part thanks to his poetic talents: Alcuin, chief scholarly adviser and for a while Angilbert’s teacher, nicknamed him Homer (or as Charlemagne called him, ‘Homerianus puer’),8 from which we can infer he had mastered the epic genre. Among Angilbert’s early work has been claimed ‘De conversione Saxonum’ (777), which celebrated Charlemagne ‘leading the new progeny of Christ into the palace’.9 Angilbert also rendered services of a different kind in the seven-eighties by helping to establish the Carolingian regime in Italy as adviser to Charlemagne’s young son, the sub-king Pippin, and then returning to Francia to advise Charlemagne himself (the king called him manualis nostrae familiaritatis auricolarius, ‘our close and intimate counsellor’), serving as a cleric in the royal chapel, and as chief envoy to Rome in the seven-nineties. At more or less the same time, Angilbert’s career at court progressed in two ways: he was given the abbacy of St.-Riquier, near Amiens, and became the lover of Charlemagne’s favourite daughter, Bertha. These signs of royal favour might seem to pull in different directions only if you did not appreciate the peculiar character of Charlemagne’s court. In the seven-nineties, Angilbert and Bertha produced two sons, one of them Nithard, the future historian of Carolingian dynastic wars, while Angilbert, wearing his abbatial hat, rebuilt the abbey-church on a splendid scale. He remained close to Charlemagne, and accompanied him to Rome in 800.

For Angilbert’s life in Charlemagne’s later years there is little evidence. He attested Charlemagne’s will in 811, perhaps on a rare visit to Aachen. He is not otherwise mentioned as involved in court activity, there was no more poetry, and there were no more children. My guess is that he had decided on conversio and that his last decade or so (he died on 18 February 814, just three weeks after Charlemagne) was spent at St.-Riquier living the life of monastic quies, quietness. It suited his age and stage of life. Other men, a new generation (Einhard, Wala), took his place in the inner counsels of Charlemagne.

A second case was that of William, count of Toulouse. Unlike Angilbert, William was no cleric but a palatinus and a warrior. But in 806 he too relinquished the life of the world to live his last years in a monastery. Of what inner motives impelled him there is absolutely no evidence. But Alcuin’s influence (804 was the year of his death) had encouraged laymen to practise daily private prayer, and thus, even while still in vita activa, to move towards a monastic life.10 Further, the presence of influential monks at court – Benedict of Aniane, Adalard of Corbie – encouraged the interest of lay aristocrats in monastic patronage, even monastic foundation. Benedict’s hagiographer wrote in the eight-twenties:

Count William who was more distinguished than anyone at the emperor’s court clung to the blessed Benedict with such affection of love that, despising the honours of the world he chose Benedict as his guide on the way to salvation . . . After he received permission [from the emperor] to convert, he surrendered to Benedict with gifts of gold and silver and all kinds of precious clothing. Nor did he allow any delay in having himself tonsured on the feastday of the apostles Peter and Paul. He put off his clothing embroidered with gold thread, and assumed the habit (habitus) of the worshippers of heaven . . . At Gellone, where he had ordered a cell to be built while he was still placed in the honour of this world, he entrusted himself to the service of Christ. Born to noble parents, he was eager to become nobler by embracing the highest poverty of Christ. For Christ he gave up the honour attained through birth.11

The hagiographer did not add that William had amassed countships on both sides of the Pyrenees, and that when he ‘converted’, he divided these between his two eldest sons (by different wives).12

A third case was that of Unroch, another of Charlemagne’s palatini, and an attester of his will, drawn up in 811.13 A fourth case was that of Charlemagne himself. His will envisaged the possibility that he might decide on withdrawal from the world (voluntaria saecularium rerum carentia), at which point his testamentary disposition would come into immediate effect.14 In the event, the emperor died in his Aachen palace, less than three years later.

One or two other ninth-century examples are worth mentioning: Louis the Pious was only forty when his first wife died, but had to be deterred by his counsellors from withdrawing from the world.15 Louis’s successor, the emperor Lothar I, did withdraw from the world, to the monastery of Prüm, disposed of his realm between his sons but died six days later: so, this was most likely the decision of a dying man rather than an aging one.16 Charles the Fat suffered, or staged, a mental and physical crisis in 873 when he publicly declared his wish to withdraw from the world, but since he was only thirty-four, this was hardly the conversio of an aged man.17 The episode’s context, though, was one of very serious tension between Louis the German and his three sons. Louis and his wife Emma, who lived into their early seventies and early sixties respectively, may well have had good political reasons for letting it be understood that they were living out a chaste marriage in later life – once their sons had begun to cause serious difficulties by repeated rebellion, solo or as duo or trio, against their father.18

The point that emerges strongly from all the above is that the transmission across time of familial authority had an inbuilt tendency to cause intra-dynastic conflict. The ninth-century Carolingians, with so many territories to share out, presented a series of particularly fraught cases. There were structural reasons, therefore, why an aging father might wish to opt out, or whose sons were ready to enforce his monastic retirement. That actually happened in 833, to Louis the Pious – a very clear case of carentia saecularium rerum involuntaria.19 Much less well recorded but likely to have produced similar conflicts were inter-generational tensions in aristocratic families. In the case of ninth-century elites, then, the developmental cycle of the domestic group (I borrow Jack Goody’s very useful concept) brought both father-son conflict and fraternal rivalry, sometimes sequential, sometimes simultaneous.20

The aging process for men, in the context of that cycle, could result in more mundane scenarios. The eighth-century Lex Bauiwariorum included a section on the circumstances in which the rebellion of the duke’s son against his father – an action normally repugnant in the law-maker’s view – might be seen as justified:

if [the father] could no longer argue a good case in a lawcourt, lead an army, judge the people, mount a horse in manly fashion (viriliter), wield his weapons vigorously (vivaciter), and, conversely, was troubled by deafness or poor sight.21

A little passage in the Royal Frankish Annals for 790 shows Charlemagne, aged only forty-two, but with four adult sons to think about, anxiously navigating up and down the river Saltz to avoid giving an appearance of slothfulness (ne quasi per otium torpere videretur).22

The case of Cozbert, a middle-ranking landowner in Alemannia in the early ninth century, could suggest an individual response to the developmental cycle, or, perhaps more probably, to aging itself (it is not clear that Cozbert had offspring), analogous to a corrody.23 He granted lands at three places, and a church, to the monastery of St.-Gall in May 816 on the following terms:

first, while I wish to remain in the world (cum in seculo manere voluero), I am to receive every year between the feast of St. Gall (16 October) and the feast of St. Martin (11 November) 8 solidi in silver, clothing and certain livestock as seemed suitable to the monks, and at the same time I am to receive two servile workers, a boy and a girl. And if it happens that I have to go to the palace or to Italy, the [community’s provosts responsible for managing three estates in the Bertholdsbaar] are to provide me with a horseman to serve me, and a well-loaded pack-horse. But when I want to convert to the monastery (ad monasterium converti voluero), then I shall have a room with a chimney assigned for my private use (kaminata privatim deputata) and I shall receive provender such as must be given to two monks (et ut duobus monachis debetur provehendam accipiam), and every year a woollen robe and two shirts and six [i.e., three pairs of ] shoes and two gloves (manices) and one cape, and bedding, and every two years a jacket; and I shall have a suitable place in the inner court when I wish to give myself to the community (me mancipare congregationi).24

This seems very much like a two-stage personal pension policy, underwritten by the monastery. Cozbert sounds rather like a prudent corrodian – a word and thing to be found in ninth-century Catalonia as in later medieval England. Private accommodation sounds the antithesis of the Benedictine Rule. Yet Cozbert seems to use the term ad monasterium converti interchangeably with me mancipare congregationi. (It is just possible that two distinct stages of withdrawal are anticipated.) Pre-arranged and paid-for care for the relatively well-off elderly was just one of the many functions performed by earlier medieval monasticism. Conversely, an irresponsible abbot of Fulda – according to complaints made by that community in 812 – had been expelling elderly monks when they became too needy and consigning them to private accommodation managed by laymen.25 There was some blurring of boundaries there.

All the above needs to be set in the broader context of Christian thinking about old age. Where did earlier medieval people get their ideas about old age from? Many, evidently, were derived from observation and experience, but there is curiously little material on this subject from the earlier middle ages.26 As for learned tradition, despite a few spectacularly old people in the Old Testament, and some substantial passages in Proverbs, biblical history had little to offer on this subject compared with classical sources, moral and medical. The central theme was, and has since remained, ambiguity. E. M. Forster noted ‘the seductive combination of increased wisdom and decaying powers’. Medical writers tended to stress the second. Cicero, on the other hand, had celebrated among the special joys of old age increased interest in agriculture and horticulture; also enjoyment of conversation and conviviality in the company of friends enhanced by now-natural moderation and abstemiousness in appetite for food and drink; but most of all growing pleasure in ‘intellectual pursuits and the satisfactions of the mind’, which in turn brought respect from juniors rather than contempt, provided that greater personal austerity was not accompanied by sourness or meanness, but like good wine, smoothed and matured by age.27

Hrabanus Maurus in the mid ninth century weighed up the good and bad: ‘Old age brings with it many good things and many bad things. Good things: because it frees us from very powerful masters, places a limit on our lusts, breaks the force of desire, increases wisdom, and gives more mature counsels’. The bad things were summed up in two words: debilitas and odium, bodily weakness and social contempt. Hrabanus had more to say about those, and especially about infirmity.28 Old age is relative: early medieval writers might rehearse the seven ages of man, but few had personal knowledge of persons of senectus in the strict classical sense of over-seventies. In practice anyone over fifty was old. In them, wisdom, mature counsel, a mind set on the next world, the weakening of lust and desire: all these were powerful assets, the last not least.

Women – deo devotae – were the first to see their chastity in mature years linked firmly with holiness and religious authority. Chaste widows were a separate ordo within the church, entitled to special respect, and protection. They wore a special habit and veil. Rich and well-born widows living in their own homes posed problems for bishops: in the end these women defied attempts at episcopal control.29 With the bishop’s approval, such women devoted themselves to prayer, and to pious works, especially the liturgical commemoration of their deceased husbands. Their old age was seen in positive terms. In one early ritual for veiling widows, the consecration-prayer asked God to ‘grant them glory for their good works, reverence for their modesty, and sanctity for their chastity’.30 Such widows were a firm fixture of various early medieval scenes, in Anglo-Saxon England, and on the Continent. They had, strictly speaking, no male equivalent. There was no word for widower. Nevertheless, my guess is that in the ninth century, as in the later middle ages in the view of Shulamith Shahar, the old body was seen ‘as an opportunity and means of atonement [for sins]’.31

With all that in mind, I think we should revisit those earlier medieval renouncers of the world. They renounced in a spirit not of defeatism but of hope. Through devotion to prayer, kings or leading men hoped to benefit their subjects as well as themselves. In 877, King Charles had the converse idea: namely, that his faithful men, in choosing to live quiete, that is, to renounce the world (quies had become virtually a synonym for such religiously-motivated withdrawal), might benefit him. Further, the timing of the withdrawal from the world was to coincide with the availability of a son or kinsman – sc. of the younger generation – to continue the father’s service to the state. Thus this clause, clause 10 of the Capitulary of Quierzy, was organically linked with clause 9, the one about the transmission of a countship if a count should die leaving a son or kinsman. Here, in other words, the king connected the transmission of high office across time with the senior man’s withdrawal from the world: the problem of succession found its solution. Finally, the king imagined the older man’s choice to withdraw from the world as motivated by love for God and the king – himself. Special love between the king and the closest of his fideles was a theme deeply embedded in what Stuart Airlie has called un monde quasi-idéologique, that embraced the ninth-century Carolingians and their aristocracies.32 Serving the king was a major constituent of the aristocrat’s sense of his identity. The king’s liturgical commemoration of favoured nobles was to have its quid pro quo in the prayers volunteered by fideles who were the kingdom’s senior citizens.

Charles the Bald’s approach was nothing if not instrumental: he intended to create a cadre of devoted intercessors. But it was also shot through with idealism: his faithful bedesmen would do it for love. The very fact that the king could entertain such hopes suggests something about the power his dynasty had acquired over aristocratic imaginations. It evokes a broader world, too, of house-monasteries in which old men lived in quasi-monastic quies, analogous to the house-convents of high-born widows; and of men like Cozbert who planned in old age to attach themselves to monasteries by special ‘private’ arrangement. I am reminded of the twelfth-century scenario that Giles Constable divined by touch in the evidential dark:

Very little is known about such relationships [between monasteries and laypeople], but they were presumably considered mutually beneficial, like those between religious, educational, and cultural institutions today and their benefactors, patrons and friends – the same old terms – who in return for donations receive prestige, invitations to dinners and receptions, and secular immortality on a bronze plaque, bench, or bookplate, or, if they give enough, a building.33

How should we situate that twelfth-century world vis-à-vis the ninth century? After re-reading Christopher Brooke on conversion by infiltration, and after focusing specifically on the needs and desires and aptitudes of ninth-century conversi of mature years, my own answer, borrowed from E. M. Forster, is: ‘only connect’.

Endnotes

- C. N. L. Brooke, ‘Historical writing in England between 850 and 1150’, in La storiografia altomedievale (Settimane di Studio del Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, xvii, 1970), pp. 233–47; C. N. L. Brooke, ‘The missionary at home: the church in the towns 1000–1250’, Studies in Church History, vi (1970), 59–83.

- C. N. L. Brooke, The Medieval Idea of Marriage (Oxford, 1989).

- C. N. L. and R. Brooke, Popular Religion in the Middle Ages: Western Europe, 1000–1300 (London, 1984).

- See above, p. 43.

- Capitularia Regum Francorum, ed. A. Boretius (2 vols., Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Leges, Hanover, 1883–93) (hereafter M.G.H. Capit.), ii, no. 281, c. 10, 358.

- M.G.H. Capit., c. 9, 358. For the doom-laden reading, see Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws, pt. vi, bk. 31, chs. 25, 28–30, trans. A. M. Cohler, B. C. Miller and H. Stone (Cambridge, 1989), pp. 708–9, 712–15. For a contextualized reading, see J. L. Nelson, Charles the Bald (London, 1992), pp. 248–51.

- For a thumb-nail sketch of his career, see J. L. Nelson, ‘La cour impériale de Charlemagne’, in La royauté et les élites dans l’Europe carolingienne, ed. R. Le Jan (Lille, 1998), pp. 177–91, at pp. 186–7, repr. in J. L. Nelson, Rulers and Ruling Families in Early Medieval Europe (Aldershot, 1999), ch. xiv.

- M.G.H. Epistolae, iv, no. 92 (dated 796), 136.

- S. Rabe, Faith, Art and Politics at Saint-Riquier: the Symbolic Vision of Angilbert (Philadelphia, Pa., 1995), pp. 54–81, at p. 65.

- See J. L. Nelson, ‘Did Charlemagne have a private life?’, in Writing Medieval Biography, 750–1250: Essays in Honour of Frank Barlow, ed. D. Bates, J. Crick and S. Hamilton (Woodbridge, 2006), pp. 15–28.

- Ardo, Vita sancti Benedicti Anianensis, c. 30, ed. G. Waitz (M.G.H. Scriptores, xv (i), Hanover, 1887), p. 211, trans. P. E. Dutton, Carolingian Civilization: a Reader (Peterborough, Oreg., 1993), p. 171 (I gratefully use Paul Dutton’s translation, making only slight changes).

- M. Aurell, Les noces du comte: mariage et pouvoir en Catalogne (785–1213) (Paris, 1995), p. 35.

- Einhard, Vita Karoli magni, c. 33, ed. O. Holder-Egger (M.G.H. Scriptores rerum Germanicarum, xxv, Hanover-Leipzig, 1911) (hereafter M.G.H.S.R.G.), p. 41, lists Unroch at number five of the counts attesting Charlemagne’s will; Unroch appears as the minder of a Saxon hostage in Indiculus obsidum Saxonum (M.G.H. Capit. i, no. 115, 233, and as a missusin the Ponthieu-Ternois-Flanders area in M.G.H. Capit., i, no. 85, 183. For Unroch and his descendants, see K. F. Werner, ‘Bedeutende Adelsfamilien im Reich Karls des Grossen’, in Karl der Grosse. Idee und Wirklichkeit, ed. W. Braunfels (5 vols., Düsseldorf, 1965–6), i. 83–142, at pp. 133–7 (‘Exkurs I, Die Unruochinger’); and for Unroch’s retirement from the world, see K. H. Krüger, ‘Sithiu/Saint-Bertin als Grablege Childerichs III und der Grafen von Flandern’, Frühmittelalterliche Studien, viii (1974), 71–80.

- Einhard, Vita Karoli, c. 33, 39. Cf. K. H. Krüger, ‘Königskonversionen im 8. Jhdt’, Frühmittelalterliche Studien, vii (1973), 169–222.

- Astronomer, Vita Hludowici imperatoris, c. 32, ed. E. Tremp (M.G.H.S.R.G., lxiv, Hanover, 1995), p. 392.

- Annales Bertiniani, s.a. 855, ed. F. Grat and others (Paris, 1964), p. 71.

- S. MacLean, ‘Ritual, misunderstanding, and the contest for meaning’, in Representations of Power in Medieval Germany, 800–1500, ed. B. Weiler and S. MacLean (Turnhout, 2006), pp. 97–120, at p. 118, points out that Charles fathered a son by a concubine not long after this event.

- E. J. Goldberg, ‘Regina nitens sanctissima Hemma: Queen Emma (827–876), Bishop Witgar of Augsburg, and the Witgar-Belt’, in Weiler and MacLean, pp. 57–95, at pp. 78–85.

- See M. de Jong, ‘Power and humility in Carolingian society: the penance of Louis the Pious’, Early Medieval Europe, i (1992), pp. 29–52.

- Cf. J. L. Nelson, ‘Charlemagne – pater optimus?’, in Am Vorabend der Kaiserkrönung, ed. P. Godman, J. Jarnut and P. Johanek (Stuttgart, 2002), pp. 269–81.

- Lex Baiuwariorum II, 9, ed. E. von Schwind (M.G.H. Leges nationum Germanicarum v (i), Hanover, 1926), pp. 302–3.

- Annales regni Francorum (so-called revised version), ed. F. Kurze (M.G.H.S.R.G., vi, Hanover, 1895), p. 87.

- For a Catalan conredium in 878, see P. de Marca, Marca Hispanica sive Limes Hispanicus (Paris, 1688), col. 803, cited by J. F. Niermeyer, Mediae Latinitatis Lexicon Minus (Leiden, 1997), p. 252, s.v. ‘conredium’. See now the evidence sensitively discussed by W. Davies, Acts of Giving: Individual, Community, and Church in Tenth-Century Christian Spain (Oxford, 2007), esp. pp. 139, 149–54. For corrodies in later medieval England, see B. Harvey, Living and Dying in England 1100–1540 (Oxford, 1993), pp. 179–209, noting that the young as well as the old could be beneficiaries of such care (both were, after all, in a state of inbecillitas, according to the Rule of St. Benedict, c. 37); see also S. Shahar, Growing Old in the Middle Ages (London, 1997), p. 125.

- H. Wartmann, Urkundenbuch der Abtei Sanct Gallen (4 vols., Zurich, 1863–99), i. no. 221 (May, 816), 211. I am very grateful to Gesine Jordan of the University of Saarland for drawing this text to the attention of the Earlier Medieval Seminar at the Institute of Historical Research, University of London (25 Apr. 2007).

- Supplex Libellus, c. v, ed. J. Semmler, in Corpus Consuetudinum Monasticarum, ed. K. Hallinger, i (Siegburg, 1963), 321–7, trans. J. L. Nelson, ‘Medieval monasticism’, in The Medieval World, ed. P. Linehan and J. L. Nelson (London, 2001), pp. 576–604, at p. 590.

- P. E. Dutton, ‘Beyond the topos of senescence: the political problems of aged Carolingian rulers’, in Aging and the Aged in Medieval Europe, ed. M. M. Sheehan (Toronto, 1990), pp. 75–94, repr. and retitled as ‘A world grown old with poets and kings’, in P. E. Dutton, Charlemagne’s Mustache and Other Cultural Clusters of a Dark Age (London, 2004), pp. 151–68, indicates the limits of available source-material. Shahar, an excellent survey, is typical in focusing almost exclusively on the period from the twelfth century onwards.

- Cicero, De senectute, cc. iv and v, trans. M. Grant, Cicero, Selected Writings (Harmondsworth, 1960), pp. 228–38, at p. 233. I have snitched the Forster quotation from Grant’s introduction to Cicero’s text, p. 211.

- Hrabanus Maurus, De rerum naturis, in Patrologia Latina, ed. J. P. Migne (221 vols. Paris, 1844–1903), iii, cols. 185–6.

- J. L. Nelson, ‘The wary widow’, in Property and Power in Early Medieval Europe, ed. W. Davies and P. Fouracre (Cambridge, 1995), pp. 82–113, repr. in J. L. Nelson, Courts, Elites and Gendered Power (Aldershot, 2007), ch. ii.

- The Claudius Pontificals, ed. D. H. Turner (Henry Bradshaw Soc., xcvii, Chichester, 1971), Pontifical I (tenth-century, but with older material), p. 71. Cf. E. Palazzo, ‘Les formules de bénédiction et de consécration des veuves au cours du haut moyen âge’, in Veuves et veuvage dans le haut Moyen Age, ed. M. Parisse (Paris, 1993), pp. 31–6; for Anglo-Saxon evidence, see S. Foot, Veiled Women (2 vols., Aldershot, 2000), i, ch. 5, esp. pp. 127–34.

- Shahar, p. 54, with nn. 79 and 84, citing St. Bernard, who said explicitly that the old body brought a man nearer to God because it had become free of lust, and Dante, who imputed spiritual elevation to the old: ‘calmly and gently, the ship lowers its sails as it approaches the harbour’. Hrabanus expressed a similar view less beautifully (cf. above, pp. 42–3).

- S. Airlie, ‘Semper fideles? Loyauté envers les Carolingiens comme constituent de l’identité aristocratique’, in Le Jan, pp. 129–43, at p. 131.

- G. Constable, The Reformation of the Twelfth Century (Cambridge, 1996), pp. 84–5..

Contribution (37-46) from European Religious Cultures: Essays Offered to Christopher Brooke on the Occasion of His Eightieth Birthday, edited by Miri Rubin (University of London, 08.05.2020), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.