A medieval past and an imagined future can still find ways to ‘touch’.

By Dr. Martha G. Newman

Professor in the Departments of History and Religious Studies

The University of Texas at Austin

Abstract

Sometime after 1188, Engelhard of Langheim composed a story about a Cistercian monk named Joseph. Engelhard insisted Joseph was a woman, but he also undercut normative assumptions to display gender fluidities for which he lacked a conceptual vocabulary. He preserved a binary gender system that controlled the dangers of a woman in a male monastery. Yet his willingness to ventriloquize Joseph’s male voice presents a Joseph who, with God’s help, successfully performed his male trans identity, while his depiction of Joseph’s death suggests Joseph’s soul miraculously became female after he died. Engelhard did not explicitly acknowledge either possibility, but in a world in which the miraculous could break naturalized categories, both transitions remain beneath the surface of his tale.

Introduction

Sometime in the last decade of the twelfth century, the Cistercian author Engelhard of Langheim dedicated a collection of stories to the nuns of the Franconian abbey of Wechterswinkel. Engelhard’s tales portray things that are not what they seem. The Eucharist looks like bread but is really the body of Christ, sweat is perfume, woollen cloth is purple silk, and monks are not always as holy as they appear. Engelhard’s last story, which depicts the life of a young monk named Joseph and his death at the Cistercian abbey of Schönau, continues this theme.1 ‘This man was a woman although no one knew it’, Engelhard proclaims as he begins his tale, this time asserting distinctions between male and female as the reality that could not be discerned from visible signs.2 But his story about the invisibility of gender differences diverges from his tales of the Eucharist and other holy objects. Whereas most of Engelhard’s stories teach how to imagine connections between the signs provided by everyday objects and an invisible and transcendent reality, the story of Joseph breaks connections between visible signs and the binary categories of gender that behaviours and physical characteristics conventionally signify. Engelhard could not find in Joseph’s outward appearance and behaviour markers that referenced normative gender distinctions. Ultimately he resorted to the physical characteristics of Joseph’s body to assert that Joseph was and would always be a woman. Nonetheless, Engelhard’s choices in constructing and narrating his tale undercut his normative assumptions and display transgender possibilities that he did not have the conceptual vocabulary to acknowledge.

I f irst wrote about brother Joseph in the early years of the twenty-first century. In an article entitled ‘Real men and imaginary women: Engelhard of Langheim considers a woman in disguise’, I analysed the tale in the context of cross-dressing. There, I referred to Joseph as ‘Hildegund’ – the name the monks eventually assign Joseph after his death – and I argued that the story illuminates its author’s confused efforts to appropriate characteristics of female religiosity in order to celebrate his monastery’s male holiness.3 I remain interested in the author’s confusions, but these last fifteen years have changed my perspective. I wrote – and still write – as a cisgender, heterosexual feminist, interested in the cultural construction of gendered categories. My earlier essay accepted Engelhard’s gender essentialism, emphasizing the f igure of Hildegund and the possibilities she offers for medieval women.4 I offer this essay to rethink what I once took for granted.5 A focus on Joseph rather than on Hildegund offers glimpses of multiple and mutable medieval genders while also demonstrating the operations of power that inscribe normative categories.6 Engelhard wrote at a time when religious women had started to follow the customs of Cistercian men, and the structure of his story preserves a normative, binary gender system that reinforces the physical separation of monks and nuns. At the same time, his story encourages a process of religious formation that nuns and monks could share, and it offers a protagonist whose identity undercuts fixed categories in multiple ways. In offering multiple readings of Joseph’s stories, I question direct lines and identifications between the past and the present but suggest the possibility that, to use Carolyn Dinshaw’s term, a medieval past and an imagined future can still find ways to ‘touch’.7

The Story of Brother Joseph

We know of brother Joseph from five accounts that Cistercian monks composed in Latin over a span of fifty years, from about 1188 to 1240. Other shortened versions appear in later collections of exempla.8 There is no evidence for Joseph’s life outside of these tales. The five descriptions of Joseph’s life contain common elements but they are not identical, suggesting that their authors heard different versions of the tale. In two, the authors identify their informants as someone who knew Joseph at Schönau; in a third, the author himself claims to have been Joseph’s friend, teacher, and fellow novice. Such variations are common among the oral and written stories that late twelfth- and early thirteenth-century Cistercians circulated between their communities. In many cases, written accounts of miraculous events and holy figures provide the visible tips of an extensive substratum of oral tales.9 These stories often claim witnesses and informants to confirm their veracity, but their variations undermine this testimony, suggesting that the witnesses authenticate the stories rhetorically rather than legally. Whether or not Joseph lived and died at Schönau, the Cistercian authors present his story as if it were plausible, exemplary, and one to be admired.

Engelhard of Langheim appears to be the first to record Joseph’s story. Born and educated in Bamberg before he joined the Franconian abbey of Langheim, Engelhard was a collector of Cistercian exempla and an author who wrote to and about religious women.10 His tales for the nuns of Wechterswinkel offer one of the first extant texts written by Cistercian monks for religious women interested in following Cistercian customs.11 It appears that Engelhard sent an earlier version of the collection to his friend Erbo, abbot of Prüfening, and that his composition contains stories that circulated orally among male communities. Sometime after 1188, he added more stories to his collection, including the tale of brother Joseph, and he sent it to the nuns at Wechterswinkel in recompense for an unspecified favour the nuns had done for him. Thus, he did not compose his stories for women alone. Nor do his stories articulate a distinctive form of female spirituality that differs from that of men. Instead, they assume that the nuns would be interested in tales about Cistercian monks. In fact, Engelhard’s stories address monks and nuns as a single social group that bypassed male sacerdotal authority on one hand, and a specifically female religiosity on the other. In describing everyday objects and behaviours that were not what they seemed, they suggest that both male and female monastics could find sacramental potential in the labour and prayer associated with their religious life.12 The story of Joseph further reflects Engelhard’s interest in addressing an audience of both monks and nuns, but it also demonstrates the limits of the Cistercians’ gendered language of sanctity. Influenced especially by Bernard of Clairvaux’s sermons on the Song of Songs, twelfth-century Cistercian monks employed feminine imagery to describe their spiritual development, and they considered their souls as the Bride of the Song who longed for the divine embrace of her Bridegroom Christ.13 Engelhard’s story suggests that this Cistercian language of gender fluidity resonated differently when addressed to an audience of both monks and nuns. By implying the possibility of actual, rather than metaphorical, movement between genders, the tale nearly slipped from Engelhard’s control. Only by asserting from the beginning that Joseph was a woman did Engelhard constrain such slippage within the realm of metaphor and reinscribe a normative gender essentialism.

Engelhard’s presentation of Joseph’s story is unusual. He wrote most of his tale in Joseph’s voice, allowing Joseph to recount his adventures and trials, and he framed Joseph’s tale with his own introduction, conclusion, and interpretation. Engelhard often composed in the present tense, frequently used direct dialogue to make the action immediate for his audience, and occasionally appended personal comments, but Joseph’s is the only tale that he constructed in the first person. Scholars have long pondered the significance of the ‘I’ in medieval texts, especially when writings about the self rely on established models and patterns and do not distinguish between history and fiction.14 The late eleventh and twelfth centuries saw a growth in first-person narratives, many of which were monastic accounts depicting a path of conversion to religious life loosely modelled on Augustine’s Confessions.15 Rarer are authors who wrote in the voice of another person. The technique does appear in stories of dream visions in which a first-person account of solitary experience is at a remove from the text in which the vision is recorded. This use of the first person asserts a story’s veracity, allowing the audience to hear the narrator recount their experiences orally.16 Engelhard’s use of the first person has the same effect, and he may have chosen this technique as a means of enhancing the immediacy of his tale. Yet Engelhard nowhere claims to have heard Joseph speak. Rather, he remarks that he relied on information provided by a monk at Langheim who had been present at Joseph’s death and funeral. Even with this information, the chain of transmission breaks down, for it is unlikely that this informant heard Joseph tell his story. Engelhard constructs Joseph’s account as an extension of Joseph’s deathbed confession at which only the prior was present. The informant, if he even existed, must have heard the story from the prior before transmitting it to Engelhard. Joseph’s language is thus Engelhard’s construction. The tension between Engelhard’s presentation of Joseph’s voice and the narrative framing that constrains the story creates possibilities within the tale that Engelhard did not explicitly acknowledge.

Although Joseph’s deathbed tale is an extension of his confession, it is a description of his life rather than an enumeration of his sins. The story is filled with the sorts of wondrous events that Cistercian storytellers such as Engelhard loved to collect. Joseph informs the prior he was born near Cologne and, as a child, accompanied his father on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem after his mother’s death. The father died in Tyre, leaving Joseph in the care of an untrustworthy servant who stole his possessions and left him destitute. Eventually, pilgrims helped him return to Europe. In Rome, he received an education, ‘begging letters in the schools just as I had begged scraps at the door ’.17 Once back in Cologne, he served in the household of the archbishop. This prelate, who was in the midst of a dispute with the emperor Frederick Barbarossa over an episcopal election at Trier, asked Joseph to transport a letter to the pope in Verona in hope that Joseph’s youth might avoid the suspicion of Frederick Barbarossa’s men. As Joseph neared Augsburg his traveling companion abandoned him, leaving him with a sack filled with stolen goods. Caught with the sack, Joseph was tried and sentenced to be hung. While imprisoned, he convinced a priest of his innocence by showing him the hidden message for the pope, and he proved his innocence to the rest of the community by undergoing an ordeal of hot iron. The people released him and caught the real thief, whom they hung.

But Joseph’s problems were not over. The thief ’s relatives resented Joseph’s acquittal, and they captured him, cut the thief from the gibbet, and suspended Joseph in his place. ‘And yet’, Joseph continues, ‘as all human aid had ceased, divine aid arrived, and a good angel of God was sent to me as solace’.18 The angel supported his feet, comforted him with a sweet taste and smell, and explained that the beautiful music he heard was the sound of angels transporting the soul of his sister to heaven. In three years, Joseph learned, he would receive a similar reception. He remained on the gibbet for three days until local shepherds noticed him, cut him down, and fled in fear when his body, still supported by the angel, floated gently to the ground. Much to his surprise, Joseph discovered he was already in Verona. He completed his errand, returned to Cologne and, at the recommendation of a female recluse, entered the Cistercian monastery of Schönau in gratitude for the divine aid he received. ‘I came here’, he informs the prior, ‘as an act of thanks in response to God because he kept me clean and unblemished in this world’.19 Now, he explains, the day foretold for his death has arrived. He soon dies, on the day he had predicted.

A Transgender Monk

Throughout his account of his life and adventures, Joseph uses male pronouns and masculine endings for his nouns and adjectives. By giving Joseph a male voice, Engelhard reveals non-normative possibilities that he did not have the language to acknowledge. One possibility is that Joseph is a transgender man. Engelhard did not have the conceptual vocabulary to articulate Joseph’s trans identity but, as Blake Gutt argues, our modern ability to notice medieval gender fluidities provides a corrective to the idea that non-normative genders are a recent phenomenon.20 Engelhard leaves traces in his account that can touch the present and help imagine the future.21 Engelhard depicts Joseph as a person who lives his life as a man, who proves his truthfulness before God through an ordeal, and who chooses to become a Cistercian monk. To see Joseph as a trans man rather than as a woman in disguise is to assume that his performance of masculinity is neither a disguise nor a choice but rather the realization of his identity.

Joseph enacts patterns of masculinity that were familiar to members of the Cistercian order. Cistercian monks frequently told tales of young men whose adventures and experiences convinced them to join a monastery to avoid the dangers of the world. Such accounts appear in a variety of forms, including exempla, sermons, letters, and first-person accounts of conversion. Aelred of Rievaulx, for instance, described his temptations at the Scottish court of King David and his eventual decision to enter a Cistercian abbey, while Bernard of Clairvaux sought to convince scholars in Paris as well as numerous young knights to abandon the dangers of the world for the monastery.22 Bernard’s parables provide allegorical accounts of young knights, often described as ‘delicate’ or ‘inexperienced’, who endure trials that teach them to combat vice, embrace virtue, and learn to trust in God.23 For the most part, Joseph’s description of his adventures follows this pattern. He too is an innocent and inexperienced youth, buffeted by the dangers of the world and supported by divine aid when abandoned by human assistance. Cistercian monks, accustomed to stories of such conversions, would have heard little unusual in his tale. One of the few comments that could have signalled Joseph’s difference is his assertion that he entered Schönau to thank God for keeping him ‘pure and unblemished in this world’. Many Cistercian stories tell of youths who succumb to temptations before they convert, while the idea of preserving purity is often associated with female sanctity. Nonetheless, Engelhard recounts other stories of monks who are also concerned about maintaining their virginity and the purity of their bodies, so even here, Joseph fits into a pattern attributed to Cistercian men. His comment might have served as a clue for those in Engelhard’s audience who had already heard Engelhard declare that Joseph was a woman, but it would not have seemed out of the ordinary for those who assumed he was a man.

Engelhard’s multiple voices, and his interest in the contrast between appearance and invisible reality opens up the possibility that Joseph is a trans man. Engelhard frames Joseph’s story, told in Joseph’s voice, with an introduction that declares that ‘this man was a woman’. This statement implies that Joseph was assigned female at birth, but it also assumes that this natal categorization was both true and fixed. Engelhard’s assertion at Joseph’s death, that the monks think it was a woman who died, furthers his presentation of gender as unalterable. The authors of the later accounts of Joseph’s life explicitly present Joseph’s masculinity as a disguise, suggesting that he adopts male clothing for reasons of safety when he and his father embark on their pilgrimage, that he lives in ever-present fear of discovery, and that he enacts stereotypically female characteristics such as vanity and sexual attractiveness.24 Engelhard’s Joseph, however, does none of these things. In fact, when Engelhard speaks in Joseph’s voice, he undermines this position, since Joseph does not present himself as a disguised woman, but as a man. Furthermore, Engelhard remarks that the female recluse who recommends Joseph to Schönau ‘knew the secrets of his conscience’, but nonetheless advised him to enter a male monastery.25 He twice mentions the recommendation of this holy woman, suggesting that it is one of the reasons the monks at Schönau did not further investigate Joseph’s background. In retrospect, her advice suggests that she both knows of Joseph’s assigned sex and recognizes his male identity as genuine. Although Engelhard explicitly employs the idea that Joseph is not what he seems, hiding a female reality under his male dress, he also implies a contrast between the appearance of Joseph’s body and the invisible reality of his male identity. Engelhard may have consciously chosen to tell Joseph’s story in Joseph’s male voice in order to confirm the veracity of the story, but this choice also implies that, despite his physical characteristics, Joseph is really a man.

Engelhard’s narration of the arc of Joseph’s life reveals patterns that resonate with trans experience. Scholars have argued that queer and trans lives construct identities outside of the normative social structures and temporal progressions from which they have often been excluded, especially outside of progressions based on biological procreation. Queerness can create alternative ways of ‘being in the world’, including new understandings of birth and development.26 In medieval Europe conversion to a religious life offered such an alternative by providing a way to escape structures and temporalities based on procreation.27 In Engelhard’s ventriloquizing of Joseph’s voice, Joseph never suggests that he was assigned female at birth. Instead, he articulates three alternative births, each of which is also marked by a death. Joseph experiences the first as a child, at the death of his mother, when his father vows to take him to Jerusalem if God permits Joseph to live. In explaining this to the prior, Joseph attributes his life to God rather than to his parents. His father’s death in Tyre initiates a second birth: Joseph became an orphan and enters a life characterized by difficulty and struggle. Joseph’s near-death experience on the gibbet marks the beginning of his third birth, one that culminates in his entrance into the monastery of Schönau. Conversion to monastic life traditionally seemed a rebirth in which a convert ‘put off the old man and took on the new’.28 In Joseph’s case, this rebirth is further accentuated by the angel’s intervention and the vision of his sister’s soul ascending to heaven. Both imply that he had embarked on a new path that led to heaven. Joseph’s three births ref lect a spiritual formation modelled on a Christian progression of grace, struggle, and salvation, a progression that also appears in Bernard of Clairvaux’s parables.29 Joseph’s self-narration performs a male identity familiar to the monks, but it also articulates the development of a particular Christian identity in which Joseph could disassociate himself from biological progressions and familial structures.

Finally, Joseph recognizes his difference by attributing it to divine beneficence, not to his own choice. He begins his story by telling the prior that after his death, ‘you will marvel at what you will find in me, although it is not customary. For God did great things for me; let my response to these gifts be fitting. If it will not bore you to hear this, I will tell you what miraculous things God did in me’.30 It is possible to read this statement as Joseph’s – or Engelhard’s – recognition that the brothers at Schönau would marvel when they discovered that Joseph’s bodily morphology seemingly revealed him to be a woman. But this statement is actually more ambiguous. Joseph thinks the prior will marvel at what the monks found ‘in him’ (‘in me’), and he repeats the phrase a sentence later when he speaks of the miraculous things done in him (‘in me’). His use of this preposition shifts the focus from the appearance of his body, suggesting that the monks would discover a gift from God that Joseph had incorporated into himself. It implies that Joseph’s identity as a man is neither a choice nor a disguise but rather a divine gift.

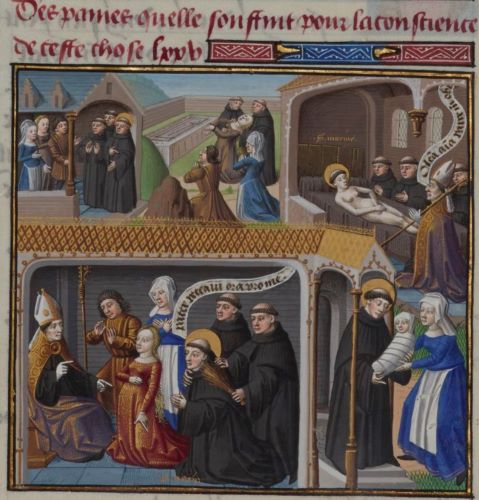

Female at Death

A reading enabled by modern trans theory, which reveals Joseph as a trans man, is not the only way of approaching non-normative gender in Engelhard’s tale. The idea of Joseph as trans separates his male gender from the appearance of his body but it also assumes that his male identity is a fixed, transcendent reality. A second reading of Engelhard’s story, however, suggests a gender fluidity in which Joseph miraculously changes from male to female at death. This possibility is what the monks at Schönau experience. They know Joseph as a man, and, even after he dies, they initially celebrate his holiness as a man who had a vision of his sister’s salvation and a foreknowledge of his own death. Only after Engelhard articulates his confidence that Joseph ‘was accepted by Christ in an odour of sanctity and led in peace by an angel of peace’ does he offer another miracle in which a man suddenly becomes a woman.31 Strikingly, the signs of this miracle are verbal more than physical. Unlike the authors of later versions of the story who linger on the appearance of Joseph’s body, noting breasts constricted by a bandage ‘lest they flopped or hung down and showed her to be a woman while she lived’, Engelhard downplays this uncovering.32 He remarks only that ‘this little body was stripped to be washed, but only by a few and likewise only for the briefest time. Immediately it was recovered with astonishment and wonder ’.33 Instead, the uncovering is verbal. In comparison to the few who saw Joseph’s body, ‘for everyone else, the news was uncovered (detegitur) that this was a woman who had died, and the abbot, who was giving his commendation, changed (transivit) the gender (genus) from masculine to feminine’.34 This act creates a moment of linguistic recognition in which ‘all those who are literate are astounded, hearing a woman commended’, and it produces a cathartic moment in which the monastic community praises and blesses God for his gifts.35 By this point, Engelhard is working to control the story, and the miracle he wants to emphasize is the ability of a woman to live as a monk without detection. Unacknowledged but suggested by the structure of his account, however, is that the monks experience a different miracle, in which Joseph only becomes a woman after death.

The miraculous, like the queer, breaks an order of things that has become naturalized. The idea that a man could become a woman or a woman become a man upends a Biblical anthropology that assumes God created two sexes distinguished by bodily characteristics. Nonetheless, the miraculous possibility that a monk could experience the transformation of his gendered or sexed identity remained within the cultural parameters of Cistercian monasticism. One of the stories that Cistercian monks circulated describes a monk who asks an angel to help him control his sexual desires; the angel, in a dream, removes his penis and the monk’s temptations disappear.36 Similarly, the community at the Cistercian abbey of Villiers celebrated their abbot William whose body at death had ‘no vestige of [male] genitals except for a clear smooth area, bright and pure’.37 Even more central to Cistercian culture were Bernard of Clairvaux’s sermons on the Song of Songs, which encouraged monks to identify with the female figures in the Canticles. In providing a model for the soul’s progression as it learns to participate in divine love, Bernard suggests that his monks can overcome the foolishness of young women, develop the productivity of a mother, and identify with the Bride’s love and longing as she seeks and encounters her Bridegroom. As Line Cecilie Engh argues, Bernard encourages monks to perform the Bride so that they may ultimately become better men.38 Engelhard’s story of Joseph, however, holds out the possibility that a performance of the Bride might actually transform monks into women.Did Joseph’s body after death reflect the female quality of his perfected soul as it became a Bride of Christ, united with the divine in heaven?

Normative Confusions

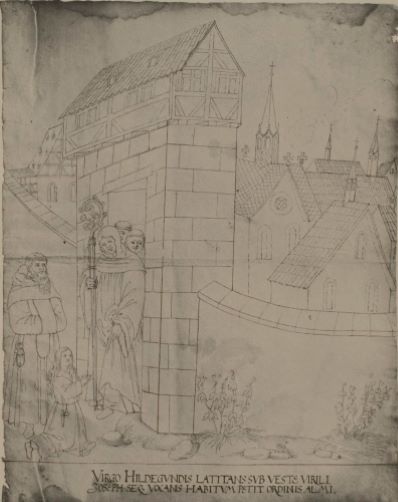

Engelhard’s introductory and concluding commentary, and his description of Joseph’s death, constrain these non-normative readings of Joseph’s gender. By insisting that Joseph was always a woman, Engelhard denies the possibility that performing the Bride might make monks female. He also denies that Joseph’s performance of maleness was a divine gift that showed he was a man. Instead, by proclaiming at the outset that ‘[t]his man was a woman, although no one knew it’, Engelhard prepares his audience to interpret Joseph’s narrative within a fixed, binary system of sexual categories in which physical morphology signals gender. Furthermore, although Joseph uses masculine endings in his own narrative, the scribe wrote feminine endings into the rubrics, and Engelhard employs female pronouns and endings in his introduction and conclusion.39 This gives the story an organizational structure that tries to assert that Joseph was always female. Engelhard describes the abbot shifting to feminine pronouns in his commemoration, and notes that the monks of Schönau refused to use the name ‘Joseph’ in their obituary, since ‘Joseph signified the masculine and not the feminine’.40 The monks eventually settle on the label ‘maid of God’. Only in later accounts do the authors determine that Hildegund is the name that Joseph was assigned at birth.

Engelhard’s insistence that Joseph is a woman limits the fluid possibilities within his story, but this tactic creates other problems for Engelhard. The Cistercians had long criticized other religious groups for an unwillingness to segregate men and women. Engelhard’s tale, as well as any circulation of an oral version of Joseph’s story, could have opened the Cistercians to the same charges they had levelled at others. Engelhard’s account dulls such criticism, however. He emphasizes that Joseph arrived at Schönau with the recommendation of the holy recluse, and he insists that Joseph entered the monastery ‘regulariter’, that is, according to the rules.41 He articulates Joseph’s recognition that the monks will not find him ‘customary’, but insists that Joseph’s behaviour is a fitting response to God’s gifts. He describes Joseph’s purity, giving no hints of sexual impropriety, and he depicts the monks’ modesty in their very brief observation of Joseph’s body.42 In fact, Engelhard asserts that Joseph converts to Cistercian life because it replicates the sense of heavenly contact that he experienced while supported by the angel.43 Despite the seeming irregularity of Joseph’s presence, Engelhard uses the story to praise the special holiness of his order.

Engelhard also controls against criticism by suggesting that it is difficult for the monks at Schönau to discern normative female characteristics from Joseph’s appearance and behaviour. However, such a diff iculty undermines the gender essentialism that Engelhard works to establish and solidify. Again, Engelhard’s approach to the story differs from that of later authors who depict feminine characteristics that remain unchanged despite Joseph’s appearance. Caesarius of Heisterbach, for example, describes Joseph as vain, interested in inspecting his appearance in a mirror, and he recounts that another monk claims that he could not look at Joseph without temptation.44 Caesarius enjoys the irony of recognizing what the characters in his story do not see. For Engelhard, however, the problem is not that the monks at Schönau cannot recognize signs of femininity that are in plain sight. Rather, the signs themselves are unclear. Despite his efforts, Engelhard can neither find nor describe characteristics that clearly distinguish men from women. As a result, he comes close to articulating a third, non-normative conception of gender, in which male-female differences evaporate and, following Paul in Galatians 3:28, ‘all are one in Jesus Christ.’45

Engelhard tries to use the dichotomy of strength and weakness to separate male and female but he cannot maintain weakness as a clear sign that Joseph is a woman. Initially, his categories seem distinct. Not only was ‘[t]his man a woman’, but the monks at Schönau should have noticed that Joseph was female since ‘her weakness frequently proclaimed it. What could she do? She did not know how to act like a man since the nature of her sex prevented it, especially among us where all of our sex are strong’.46 Yet at the same time, Joseph’s weakness is no different from that of the monks around him. Engelhard describes Joseph’s weariness and exhaustion, but then asks: ‘What in this seems female, what is to be suspected as foreign and new?’47 There was nothing uniquely female in Joseph’s behaviour. Engelhard tells of other male novices who became weary and despaired of their ability to endure Cistercian life; in fact, this was something he experienced himself when a novice. Even as an adult, he thought it possible for a monk to show a ‘female’ weakness, for in a letter to his friend Erbo of Prüfening, he develops an elaborate humility trope through which he confesses that he himself ‘is a woman’ because he does not have the strength to do manly things.48 The weakness with which Engelhard tries to characterize women could also describe the condition of men.

In fact, Joseph does not remain weak. Like other monks who model their development on Cistercian stories and sermons, Joseph gradually moves beyond feminine weakness to became strong. As a result, Engelhard’s language becomes contradictory. At times, he suggests that God works through female weakness, for Joseph is a ‘delicate girl in whom the virtue of God and the wisdom of Christ could mock the devil’.49 Yet this young woman also overcomes her sex, acting as ‘a weak woman who had forgotten her sex, who entered and finished the battle, and who triumphed over the enemy’.50 Like the young knights in Bernard of Clairvaux’s parables who fight against temptations and learn to become strong, Joseph too ‘valiantly (fortiter) but briefly undertook to perform strong (fortes) battles in war, so that as victory was achieved by this weak (infirmiori) knight over the strong (forti) enemy, so glory increased for the king’.51 At this point, Engelhard’s interpretation dovetails with Joseph’s own narration, for whether as a young man or as a young woman, Joseph resembles other virtuous monks in fighting valiantly to overcome weakness and become strong.

Having tried, and failed, to maintain a dichotomy between female weakness and male strength, Engelhard returns to an essentialist separation of male and female by suggesting gendered reactions to Joseph’s story. He tells his audience, ‘I wish this to be a wonder for women but an example for men, so that while women boast about her, men are ashamed that today we are not lacking women who dare strong things for Christ, while the majority of men follow the weakness of women’.52 In some of the manuscripts of the story, Engelhard goes still further, telling his readers: ‘I do not encourage this in women, for while many are equal in strength, they are unequal in fate, and often the stronger falls at the same turning point in battle at which the weaker triumphs’.53 At this point, Engelhard dissolves the dichotomy between male strength and female weakness with which he began his tale. Now men have become weak and women dare to be strong, so much so that the sexes have become equal in strength and can only be distinguished by fortune. In fact, Engelhard ends his exemplum by asking monks to identify with Joseph’s ‘female’ weakness, and to take to heart the message that God would reward the weak. Weakness is no longer a natural condition of women, but has become a characteristic of men that they should fight to overcome.

A Story for Cistercian Nuns

Engelhard assumed that both men and women would read his story, but he hoped that monks and nuns would read it differently. This gendered response reflects the circumstances around the composition and transmission of his text. In dedicating his collection to the nuns of Wechterswinkel, he demonstrates his supposition that nuns would be interested in stories of Cistercian monks. This gift further supports the likelihood that these nuns already followed Cistercian customs or were interested in doing so. Exactly what Cistercian customs they might have adopted, however, is not clear. Twelfth-century Cistercian women ‘followed the institutes of the Cistercian brothers’, but we do not know the extent to which such communities adapted male customs for the use of women.54 One twelfth-century observer, Herman of Tournay, describes women in the diocese of Laon as living ‘according to the ordo of Cîteaux, which many men and hardened youth fear to undertake’; he portrays women who not only worked at weaving and sewing, which he understands to be women’s work, but who also harvested, cut down trees, and cleared the fields, imitating ‘in all things the monks of Clairvaux’.55 Engelhard’s depiction of female strength as equal to that of men suggests that he thought women were capable of living as did men, and that their struggles with the difficulties of Cistercian life would be no different from those of men. But he also assumed that his audiences lived in communities that were segregated by sex. In suggesting that the women of Wechterswinkel should admire Joseph but not imitate him, Engelhard makes clear that he did not want women to become monks. His story of Joseph offers to both men and women a progression from weakness to strength, but it also insists they remain in gender-specific spaces.

Engelhard understood male and female as divinely established categories, naturalized by God’s creation of humanity and displayed through bodily characteristics. Furthermore, he considered sexual difference as intertwined with grammatical distinctions, so that the gender of names and pronouns signifies sexual categories. Still, he inhabited a monastic culture in which monks could identify with the female Bride in the Song of Songs, and religious women could enact the virile strength needed to adopt the customs and institutes of their male counterparts. His story of Joseph displays this fluidity. The language of his story corresponds with his understanding of his audience’s social position, as he thought that monks and nuns could follow the same customs and enact the same processes of spiritual formation in which they, like Joseph, could learn to overcome weakness and become strong. Nonetheless, he sought to keep such gender fluidities within the realm of metaphor, and to maintain a real and physical separation between female and male. By placing Joseph in the category of people and things that look one way but are another, he insisted that Joseph was always a woman, whom divine grace had made capable of acting as if she were a man, and he ignored the possibility that Joseph instead may always have been a man.

Nonetheless, Engelhard’s story also contains elements that unsettle medieval Christian gender binaries and touch the medieval to the present. In trying to control against the dangers of a woman in a male monastery, Engelhard blurred the signs of gender difference. His willingness to ventriloquize Joseph’s voice shows that language could create a Joseph who, with God’s help, successfully performs his trans identity. Yet Engelhard’s language also suggests a Joseph who miraculously became a woman after death. Engelhard did not elaborate on either possibility, but in a world in which the miraculous could break naturalized categories and disrupt the normal order of things, they both remain just beneath the surface of his tale. Engelhard may have employed Joseph’s tale to limit female behaviours and assert normative genders, but his tale also undermines fixed binaries, and it suggests that medieval religious communities could provide a space for transgender possibilities and expressions of gender fluidity.

Appendix

Endnotes

- Engelhard’s story collection has been partially edited by Griesser (‘Exempelbuch’, pp. 55-73). Schwarzer edited the last tale (‘Vitae’, pp. 515-29), usually known as the story of Hildegund of Schönau (Bibliotheca hagiographica latina no. 3936). I cite Schwarzer’s edition except in cases where the manuscripts diverge. All translations from Latin, whether from this text or others, are my own.

- ‘Femina fuit hic homo; nemo cognovit’. Schwarzer, ‘Vitae’, p. 516.

- Newman, ‘Real Men’, pp. 1184-1213. I relied on Marjorie Garber’s insights in Vested Interests, where she discusses the ways cross-dressing creates space for a ‘third gender’. Although the concept of a ‘third gender’ remains useful, I now recognize the essentialist assumptions in the concept of transvestism and the way an emphasis on disguise can erase transgender possibilities. I am grateful to C. Libby for our conversation about disguise and for sharing forthcoming work. We need to reexamine other medieval saints who once were considered transvestites. For the older literature, see Anson, ‘Female Transvestite’; and Patlagean, ‘L’histoire’. For the latest work, see, for example, Bychowski (pp. 245-65), Wright (pp. 155-76) and Ogden (pp. 201-21) in this volume. On ‘Hildegund’, see Hotchkiss, Clothes; and Liebers, Geschichte.

- As ‘Hildegund’ is Joseph’s dead name, I will only use it when quoting Engelhard. See ‘Dead Name; Dead-Naming; Dead Name’ in the Appendix: p. 292.

- See also Karras and Linkinen, ‘Revisited’.

- See Mills, ‘Visibly Trans?’, p. 541.

- Dinshaw, Getting Medieval, p. 47; Devun and Tortorici, ‘Trans, Time, and History’, pp. 530-31.

- For analysis of the five versions of this story, see McGuire, ‘Written Sources’, pp. 247-54, and Newman, ‘Real Men’. Joseph also appears in the vita of Eberard of Commeda [Bibliotheca hagiographica latina no. 2361]; see de Visch, Vita.

- See Newman, ‘Making Cistercian Exempla’, pp. 45-66.

- His extant texts include correspondence with Erbo, abbot of Prüfening; a vita of the nun and canoness Mechthild of Diessen; a meditation on the life of the Virgin Mary; and a collection of Cistercian exempla dedicated to the Cistercian nuns of Wechterswinkel. For his letters, see Griesser, ‘Engelhard von Langheim und Abt Erbo von Prüfening’; for the vita, see Vita de B. Mathilde Virgine [Bibliotheca hagiographica latina, 5686], AASS 7 May, pp. 436-49, now translated by Lyon in Noble Society, pp. 163-219. The meditation on the life of the Virgin is unedited, but can be found in Poznań, Biblioteka Raczyńskich Rkp.156, fols. 3r-26v.

- Scholars long considered Wechterswinkel as one of the f irst houses of Cistercian women in German-speaking lands, but Wagner (Urkunden) has shown that much of the evidence for this affiliation dates to the thirteenth century. Nonetheless, the twelfth-century nuns at Wechterswinkel founded two communities that followed Cistercian customs, established granges, and rededicated their community in honor of the Virgin Mary. By the early thirteenth century, they were clearly affiliated with the Cistercian order; it may be that Engelhard wrote these nuns as they were considering adopting Cistercian customs.

- Newman, Cistercian Stories, pp. 138-48.

- See, most recently, Engh, Gendered Identities. See also Newman, ‘Crucified by the Virtues’, pp. 192-209.

- See Schmitt’s discussion of medieval autobiography (Conversion, pp. 44-50), and McNamer’s discussion of the relation between the author’s and the recipient’s ‘I’ (Affective Meditation, pp. 67-73).

- Schmitt, Conversion, pp. 57-62. These include the writings of John of Fécamp, Otloh of Saint-Emmeran, Guibert of Nogent, and Aelred of Rievaulx.

- See the account of the conversion of Herman the Jew (Schmitt, Conversion), which relies on a first-person narration of Herman’s dream. See also Thomas of Cantimpré’s vita of Christina the Astonishing in Collected Saints’ Lives; and Gardiner, Visions, especially pp. xxiii-xxv.

- ‘Adjeci studium et didici litteras, mendicans illas in scholis sicut in ostiis bucellas’. Schwarzer, ‘Vitae’, p. 517.

- ‘Attamen humano cessante auxilio, affuit divinum, et angelus Dei bonus mihi missus in solatium’. Ibid., p. 519.

- ‘Sic veni huc in gratiarum actione responsurus Deo, quia mundum et immaculatum custodivit ab hoc seculo’. Ibid. This is a quotation from the Epistle of James, 1:27.

- Gutt, ‘Transgender Genealogy’, p. 130. See also Gutt, ‘Medieval Trans Lives’.

- Devun and Tortorici, ‘Trans, Time, and History’, pp. 530-31, Dinshaw, p. 47, Getting Medieval.

- See Aelred of Rievaulx, On Spiritual Friendship; Bernard of Clairvaux, Letters 108-114, pp. 156-172; and Bernard of Clairvaux, “Sermon on Conversion”, in Sermons, pp. 31-79.

- On Bernard of Clairvaux’s parables, see Bruun, Parables.

- ‘Vita Hildegundis’, in AASS 2 April: pp. 778-88; Caesarius of Heisterbach, Dialogus Miraculorum, i, c. 40, pp. 47-53.

- ‘[S]pecialiter ei commendatus ab inclusa sancta que secreti hujus sola creditor conscia’. Schwarzer, ‘Vitae’, p. 517.

- See, for instance, Edelman, No Future, pp. 5-8; Halberstam, Queer Art, pp. 2-3, 98. Gutt, in ‘Transgender Genealogy’, employs Deleuze and Guattari to retheorize this antisocial turn and show how a story can create queer socialities.

- Insistence on celibacy often breaks familial expectations of marriage and procreation. See, for instance, the life of Christina of Markyate, especially the analysis by Head, ‘Marriages’, pp. 75-102.

- See Ephesians 4.22, and the Cistercians’ description of conversion in their Exordium parvum c. 15, in Waddell, Narrative and Legislative Texts, p. 434.

- On resurrection and resuscitation in saints’ lives, see Spencer-Hall, Medieval Saints, pp. 83- 87.

- ‘Invenietis in me, quod miremini, sed non oportet. Magna mihi fecit Deus; dignum esset, quod responderem beneficiis ejus. Si non tedet vobis audire, referam vobis, quid miraclorum fecit Deus in me’. Schwarzer, ‘Vitae’. p. 517.

- ‘[A]cceptus ipse Christo in odorem suavitatis et deductus in pace ab angelis pacis’. Ibid., p. 520.

- ‘[Q]ua constricta fuerant ubera, ne fluerent aut dependerent’. Vita S. Hildegundis Virginis AASS 5.32, p. 787.

- ‘Tollitur ex more corpusculum, nudatur ad lavandum, a paucis tamen idem que brevissimum; nam protinus est cum stupore et admiratione retectum’. Schwarzer, ‘Vitae’, p. 520.

- ‘Ceterum fama detegitur cunctis, feminam esse, que obiit et in commendatione, quam abbas interim fecit, genus masculinum in femininum transivit’. Ibid. Every version of the story emphasizes that the abbot changed the Latin gender markers of his prayers, suggesting that the Cistercians found this an essential element of the narrative.

- ‘Stupent litterati omnes, audientes feminam commendari, et inter longa suspiria mirabantur virtutem Christi’. Schwarzer, ‘Vitae’, p. 520.

- Herbert of Clairvaux, Liber, 1.3, pp. 10-11.

- ‘Nec apparuit in loco dicto aliquod vestigium genitalium nisi sola planities plana, clara et munda, reverberans oculos intuentium claritate nimia’. Cronica Villariensis monasterii, ed. G. Waitz, MGH SS 25:202.

- Engh, Gendered Identities, pp. 405-8. See also Bynum, ‘Jesus as Mother’, pp. 110-65.

- A single exception: Engelhard once uses gloriosus (glorious) rather than gloriosa in his commentary. Schwarzer, ‘Vitae’, p. 517.

- ‘[Q]uia Joseph masculum, et non feminam significaret’. Ibid., p. 521.

- ‘Intravit regulariter intromissus’. Ibid., p. 516.

- In this, Engelhard’s story differs from Byzantine stories of transformation, in which monks who lived as male but were assigned female at death were accused of fathering children. On this, see Bychowski (pp. 245-65) and Szabo (pp. 109-29) in this volume.

- ‘Reor et hoc ordinis nostris qualecunque preconium, quod virgo Christi tot agonibus fatigata, nec victa, dum ab angelo transitus sui tempus et felicitatem agnovit, nusquam sibi tutius Deoque laudabilius quam in religione nostra finiri se credidit’. Schwarzer, ‘Vitae’, p. 520.

- Caesarius of Heisterbach, Dialogus Miraculorum, i, c. 40, pp. 46-53.

- Engelhard employs Pauline ideas of strength and weakness in his Vita de B. Mathilde Virgine, primarily to note Mechthild’s strength. He does not make her male, but compares her to a list of strong women. On Galatians 3.28, see Meeks, ‘Image’, pp. 165-208; and Kahl, ‘No Longer Male’, pp. 37-49. On a third gender in early medieval saints’ lives, see McDaniel, Third Gender.

- ‘Femina fuit hic homo; nemo cognovit, quamquam hoc infirmitas crebra clamaverit. Quid faceret? viriliter agere noluit, obstitit sexus natura, maxime apud nos, ubi cuncta sunt fortia.’ Schwarzer, ‘Vitae’, p. 516.

- ‘Sed quid in illa videre femineum, quid alienum aut novum suspicari?’ Ibid., pp. 516-17.

- ‘Fateor, mulier sum ego, uiris me non comparo, patrem me fore non deopto, uirtute dico, non dignitate.’ Griesser, ‘Engelhard von Langheim und Abt Erbo von Prüfening’, p. 25.

- ‘[Q]uod in puella tam tenera diabolo illusisset Dei virtus et dei sapientia Christi.’ Schwarzer, ‘Vitae’, p. 520.

- ‘[F]ragilis hec oblita sit sexum, inierit atque finierit prelium, triumpharit inimicum’. Ibid.

- ‘Fortiter siquidem et non diu in bello factura fortes pugnas aggressa est, ut regi suo tanto cresceret gloria, quanto [in]f irmiori militi f ieret a forti hoste victoria’. Ibid.

- ‘Velim hanc miraculo feminis, viris exemplo, ut glorientur ille, illi erubescant, quod hodieque non desint in feminis, que pro Christo audeant fortia, quod in viris pars maxima mulierum sectantur inf irma.’ Ibid.

- ‘Nulli tamen feminarum similia suaserim, quia multis par fortitudo, sed dispar est fortuna, et eodem belli discrimine sepe cadit fortior, quo vincit inf irmior.’ Ibid. This second sentence appears in the two copies of Engelhard’s story collection now in the Biblioteka Raczyńskich in Poznań, Poland, but not in a manuscript produced at the male monastery of Prüfening. It is possible that the Poznań manuscripts, filled with Engelhard’s texts for and about women, may have been intended for female communities.

- As Berman and others have argued, women who ‘followed the institutes of the Cistercian brothers’ should be considered Cistercian nuns (Berman, ‘Cistercian Nuns’, pp. 853-55). See also Lester, Cistercian Nuns, pp. 83-84.

- ‘Ordinem Cistellensem, quem multi virorum et robustorum juvenum aggredi metuunt’; ‘vitamque Clarevallensium monachorum per omnia imitantes’. Herman of Tournay, De miraculis, PL 156: 1001-02.

Bibliography

Manuscripts

- Engelhard of Langheim’s Exempla Book, Poznań, Poland, Biblioteka Raczyńskich Rkp.156, fols. 49v-97v.

- Engelhard of Langheim’s Exempla Book, Poznań, Poland. Biblioteka Raczyńskich Rkp.173, fols. 42r-101r.

Primary Sources

- Aelred of Rievaulx, Spiritual Friendship, trans. by Lawrence C. Braceland, ed. by Marsha Dutton (Collegeville: Cistercian Publications, 2010).

- Bernard of Clairvaux, The Letters of Bernard of Clairvaux, trans. by Bruno Scott James (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1998).

- —, Sermons on Conversion, trans. by Marie-Bernard Saïd (Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications, 1981).

- Bibliotheca hagiographica latina antiquae et mediae aetatis, 2 vols. (Brussels: Société des Bollandistes, 1898-1901).

- Caesarius of Heisterbach, Dialogus Miraculorum, ed. by Joseph Strange, 2 vols. (Cologne: Heberle, 1951).

- Cronica Villariensis monasterii, ed. by G. Waitz, in Monumenta Germania Historica, Scriptores 25 (Hannover: Hansche, 1880), pp. 195-209.

- Engelhard of Langheim, Vita de B. Mathilde Virginis, ed. by Gottfrird Henschen, Acta Sanctorum 7 May, 436-449 (Paris: Victor Palmé, 1866).

- Gardiner, Eileen, ed., Visions of Heaven & Hell before Dante (New York: Italica, 1989).

- Griesser, Bruno, ‘Engelhard von Langheim und Abt Erbo von Prüfening: Neue Belege zu Engelhards Exempelbuch’, Chistercienser-Chronik, 67/68 (1964), 22-37; 76 (1969), 20-24.

- —, ‘Engelhard von Langheim und sein Exempelbuch für die Nonnen von Wechterswinkel’, Cistercienser-Chronik, 65/66 (1963), 55-73.

- Herbert of Clairvaux, Liber visionum et miraculorum Clarevallensium, ed. by Giancarlo Zichi, Graziano Fois, and Stefano Mula (Turnhout: Brepols, 2017).

- Herman of Tournay, De miraculis sanctae Mariae Laudunensis, in Patrologia Latina, cursus completus, ed. by J.-P. Migne, 221 vols. (Paris: Migne, 1841-1865), 156:961-1016.

- Lyon, Jonathan R., trans., Noble Society: Five Lives from Twelfth-Century Germany (Manchester: Manchester University, 2017).

- Schwarzer, Joseph, ‘Vitae und Miracula aus Kloster Ebrach’, Neues Archiv der Gesellschaft für ältere deutsche Geschichtskunde, 6 (1881), 515-29.

- Thomas of Cantimpré, The Collected Saints’ Lives, ed. and trans. by Barbara Newman and Margot King (Turnhout: Brepols, 2008).

- Visch, C. de, ed., Vita reverendi in Christo patris ac domini D. Adriani … vitae alio-rum duorum veterum monachorum ord. Cisterc. sanctitatis opinione illustrium, Eberardi cognominati vulgo de Commeda… ([Dunes] 165 5).‘Vita Hildegundis’, in Acta Sanctorum, 2 April, 778-88 (Paris: Victor Palmé, 1866).

- Waddell, Chrysogonus, ed., Narrative and Legislative Texts from Early Cîteaux (Cîteaux: Commentarii cistercienses, 1999).

- Wagner, Heinrich, Urkunden und Regesten des Frauenklosters Wechterswinkel, Quellen und Forschungen zur Geschichtes des Bistums und Hochstifts Würzburg 70 (Würzburg: Kommissionsverlag Ferdinand Schöningh, 2015).

Secondary Sources

- Anson, John, ‘The Female Transvestite in Early Monasticism: The Origin and Development of a Motif ’, Viator, 5 (1974), 1-32.

- Berman, Constance, ‘Were There Twelfth-Century Cistercian Nuns?’ Church History, 68 (1999), 824-64.

- Bruun, Mette B., Parables: Bernard of Clairvaux’s Mapping of Spiritual Topography (Leiden: Brill, 2007).

- Bynum, Caroline Walker, ‘Jesus as Mother and Abbot as Mother: Some Themes in Twelfth-Century Cistercian Writing’, in Jesus as Mother: Studies in the Spirituality of the High Middle Ages (Berkeley: University of California, 1982), pp. 110-65.

- DeVun, Leah, and Zeb Tortorici, ‘Trans, Time, and History’, Transgender Studies Quarterly, 5.4 (2018), 518-39.

- Dinshaw, Carolyn, Getting Medieval: Sexualities and Communities, Pre- and Post-modern (Durham: Duke University, 1999).

- Edelman, Lee, No Future: Queer Theory and the Death Drive (Durham: Duke University, 2004).

- Engh, Line Cecilie, Gendered Identities in Bernard of Clairvaux’s Sermons on the Song of Songs: Performing the Bride (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014).

- Garber, Marjorie, Vested Interests: Cross-Dressing and Cultural Anxiety (New York : Routledge, 1992).

- Gutt, Blake, ‘Medieval Trans Lives in Anamorphosis: Looking Back and Seeing Differently (Pregnant Men and Backward Birth)’, Medieval Feminist Forum, 55.1 (2019), 174-206.

- —, ‘Transgender Genealogy in Tristan de Nanteuil’, Exemplaria, 30.2 (2018), 129-46.

- Halberstam, J., The Queer Art of Failure (Durham: Duke University, 2011).

- Head, Thomas, ‘The Marriages of Christina of Markyate’, Viator, 21 (1990), 75-102.

- Hotchkiss, Valerie R, Clothes Make the Man: Female Cross Dressing in Medieval Europe (New York: Garland, 1996).

- Kahl, Brigitte, ‘No Longer Male: Masculinity Struggles behind Galatians 3:28’, Journal for the Study of the New Testament, 79 (2001), 37-49.

- Karras, Ruth Mazo and Tom Linkinen, ‘John/Eleanor Rykener Revisited’, in Founding Feminisms in Medieval Studies: Essays in Honor of E. Jane Burns, ed. by Laine E. Doggett and Daniel E. O’Sullivan (Woodbridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2016), pp. 111-24.

- Lester, Anne, Creating Cistercian Nuns: The Women’s Religious Movement and Its Reform in Thirteenth-Century Champagne (Ithaca: Cornell University, 2011).

- Libby, C., ‘The Historian and the Sexologist: Revisiting the Transvestite Saint’, Transgender Studies Quarterly, Special Issue: Europa (Summer 2021).

- Liebers, Andrea, “Eine Frau War Dieser Mann”, Die Geschichte der Hildegund von Schönau (Zürich: eFeF-Verlag, 1989).

- McDaniel, Rhonda L., The Third Gender and Aelfric’s “Lives of Saints” (Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute, 2018).

- McGuire, Brian Patrick, ‘Written Sources and Cistercian Inspiration in Caesarius of Heisterbach’, Analecta Cisterciensia, 35 (1979), 227-82.

- McNamer, Sarah, Affective Meditation and the Invention of Medieval Compassion (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2009).

- Meeks, Wayne, ‘Image of the Androgyne: Some Uses of a Symbol in Earliest Christianity’, History of Religions, 13 (1974), 165-208.

- Mills, Robert, ‘Visibly Trans? Picturing Saint Eugenia in Medieval Art,’ Transgender Studies Quarterly, 5.4 (2018), 540-64.

- Newman, Martha G., ‘Making Cistercian Exempla or, the Problem of the Monk Who Wouldn’t Talk’, Cistercian Studies Quarterly, 46.1 (2011), 45-66.

- —, ‘Real Men and Imaginary Women: Engelhard of Langheim Considers a Woman in Disguise’, Speculum,78 (2003), 1184-1213.

- —, Newman, Martha G. ‘Crucified by the Virtues: Monks, Lay Brothers, and Women in Thirteenth-Century Cistercian Saints’ Lives’, in Gender and Difference in the Middle Ages, ed. by Sharon Farmer and Carol Braun Pasternack (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2003), pp. 192-209.

- —, Cistercian Stories for Nuns and Monks: The Sacramental Imagination of Engelhard of Langheim (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2020).

- Patlagean, Evelyne, ‘L’histoire de la femme déguisée en moine et l’évolution de la sainteté féminine à Byzance’, Studi medievali, 3rd. ser., 17.2 (1976), 597-623.

- Schmitt, Jean-Claude, The Conversion of Herman the Jew: Autobiography, History, and Fiction in the Twelfth-Century, trans. Alex J. Novikoff (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2003).

- Spencer-Hall, Alicia, Medieval Saints and Modern Screens: Divine Visions as Cinematic Experience (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University, 2018).

Chapter 1 (43-63) from Trans and Genderqueer Subjects in Medieval Hagiography, edited by Alicia Spencer-Hall and Blake Gutt (Amsterdam University Press, 04.06.2021), published by OAPEN under the terms of an Open Access license.