Close woman–woman friendships that supported and made the work of the visionary possible.

By Dr. Jennifer N. Brown

Professor of Writing, Literature, and Language

Chair, Humanities & Social Sciences

Chair, Writing Literature & Language

Marymount Manhattan College

The medieval women whose lives have come to us in most detail are the exceptional ones, those championed by powerful men, and those who were or remain controversial. In some cases—such as with visionary or mystical women—they are all three at once. And all too often the stories that survive—often hagiographies—are told by men and primarily concerned with the men with whom these women had often deep, intimate friendships. Many scholars have written about the close relationships between male writers and their female subjects, or other cross-sex friendships born from intellectual and spiritual connection.1 But surely for many of these women, particularly those who lived or ended their lives in cloisters surrounded by other women, their friendships with their sisters and female friends were the deepest. This essay seeks to answer the question Karma Lochrie raises in her essay “Between Women”: “Where [in medieval texts] were the women who formed communities with each other, engaged in deep, abiding friendship together, and experienced sexual bonds with other women?”2 I have chosen to look at visionary women, whose specific burden of care and support is perhaps more urgent than that of other medieval religious women because of the physical and emotional toll of their raptures. In choosing a few examples from the twelfth century to the sixteenth, in various European contexts (modern-day Low Countries, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, and England), I hope to demonstrate how necessary the female friend was to the medieval visionary woman and how, by looking closely at their surviving textual evidence, we can see those friendships in stark relief.

There are many women I could consider for this essay, but I have chosen those that I feel exemplify some of the categories of women’s spiritual friendship that we can glean from medieval sources and that demonstrate the nuanced relationships that surrounded and supported them: the mentor and/or mentee, the scribe and/or intellectual confidant, and a member of the visionary’s close circle or community of support. The women I examine here cross these categories, and sometimes blur them, but they clearly represent close woman–woman friendships that support and make the work of the visionary possible: Hildegard of Bingen and two nuns she lived with and knew, as well as some women with whom she had an epistolary friendship; Elsbeth of Stagel and her sisterbook writings about Elizabeth of Töss; Catherine of Siena and the women of her famiglia, especially her female scribes; and, finally, the early modern Syon nun Mary Champney, a woman who inspired an anonymously authored vita after her death. In each of these cases, the friendship among women is not central (and is often, indeed, hidden), but between the lines of their surviving records one can piece together how these celebrated women had a network of others around them making their success possible.

Friendship has previously been examined in a spiritual context, and many of the women looked at here are known for their male friends (Hildegard and Volmar; Elsbeth of Stagel and Henry Suso; Catherine of Siena and Raymond of Capua). In Hildegard’s and Catherine’s cases, these friends also became the women’s hagiographers. Their friendships thrived despite a tradition of auctoritas that agreed, as Jane Tibbets Schulenburg notes, that “it was virtually impossible for women to enter into and maintain ‘pure’ friendships with members of the opposite sex.”3 The potential erotics of these relationships—imbalanced because of the notoriety of the woman visionary/saint and the hagiographer imbued with Church power and masculine authority—can sometimes be read into the vitae or other surviving texts. Alongside this tradition is another of “spiritual friendship,” largely defined by the work of Aelred of Rievaulx in his book of that title, De spiritali amicitia, written in the mid-twelfth century, a text that was widely translated and disseminated.4 Aelred drew on classical works but reframed them in a Christian context and described how human friendship can lead to the divine. Writing at first a dialogue between two men and later a discussion among three, Aelred explains the true nature of friendship and how it opens the mind and heart to Christ: “Was that not like the first fruits of bliss, so to love and so to be loved, to help and to be helped, and from the sweetness of brotherly love to fly aloft toward that higher place in the splendor of divine love, or from the ladder of charity now to soar to the embrace of Christ himself, or, now descending to the love of one’s neighbor, there sweetly to rest?”5 However, Aelred is clearly dis-cussing male friendship here—the “brotherly” love he gestures toward places these friendships firmly in the monastery, although he himself documents his close relationship to his sister in the guidelines he writes for her life as an anchoress, De instiutione inclusarum. As Lochrie has noted, however, female–female friendship is a dangerous proposition in Aelred’s eyes. For in the text he writes to his sister, he “imagines the slippery slope leading from solitary spiritual perfection to sexual and spiritual decadence through female gossip.”6 For Aelred, spiritual friendship must involve men.

There are surely some similarities between the male, monastic friend-ship that Aelred envisions and those among medieval religious women. For example, Marsha Dutton points out that for Aelred, the seeds of that spiritual friendship are in the work of the community and in the monastic life. In this sense, many of the women do have this kind of “spiritual friendship” that he envisioned, buoyed and supported by the women of their communities, either formal—like the Dominican nuns in sisterbooks—or informal—like the famiglia that surrounded Catherine of Siena.7 In this light, Aelred envisions the spiritual friendship between Mary and Martha of Bethany as a metaphor for the perfect friendship. As Dutton notes, “These sisters appear throughout Aelred’s works . . . as representatives of the contemplative and active lives and of the dynamic tension between those lives. Additionally, however, they represent the way their friendship contained Jesus concretely at its center.”8 Aelred sees in Mary and Martha the embodiment of community, of service, of prayer, and—despite their sex—of brotherly love.

I propose here that friendship among religious women, particularly visionary women, functions differently. Aelred’s vision of male monastic friendship has also governed how both contemporaries and present-day readers of medieval women’s lives have read these friendships among spiritual women. But by moving away from this model, we can see that there are important distinctions. Jane Tibbets Schulenburg’s extensive study of female sanctity traces the ways in which friendship evolved and was seen among men and women throughout medieval Christianity. She notes that in women’s same-sex friend-ships, there persists a “frustrating silence,” but that by looking more closely at the extant evidence of holy women’s lives, such as their vitae, “bonds of friendship seem in fact to have played a remarkably important role in the lives of these early medieval women.”9 Although since Schulenburg’s book (1998) there has been more work, it has primarily focused on the erotic and queer potential and tensions of same-sex friendships in monastic settings.10 The texts I am looking at here certainly contain these possibilities—Hildegard’s letters to Richardis, for example, almost demand to be read through this lens, as her passion for and distress about Richardis are so palpable. They read like a woman’s loss of a lover, not just of a friend and confidante. I do not mean to discount the erotic interpretations inherent in these examples; I believe both are true: the women in these texts are friends and they can also be lovers or potential lovers. Their friendship may not be sexual, or it may be infused with erotics, or it may be both.

Visionary women complicate some of the elements of Aelred’s schematic. Women’s relationships can be generational, familial, and erotic, but women’s friendship intersects all of these while also carving out its own distinct space. They are also not necessarily a relationship between equals, as Aristotle argued, and they are not uncomplicated. While many of these women live in communities, they also are fundamentally apart from communal life either because of the physical and emotional toll of the visions or because of the kind of work their visions lead them to (theological, political, literary). In this way, Christ is not at the center of women’s friendships. He may be at the center of the visionary woman’s life and consciousness, but her friends work to make that possible for her. These friendships take the form of a community supporting the visionary, as powerful mentoring relationships, and as familial ones—modeled as sisters or mothers/daughters.

Visionary women’s friends are always part of their hagiographies. Many of their visions, in fact, concern the lives or futures of friends for whom they have concern. As H. M. Canatella has noted, “Visionary experience was often a key component of medieval spiritual friendship. For example, Christina of Markyate’s vita often described visions that she had of Abbot Geoffrey of Saint Albans, and these visions served to provide Christina with special knowledge that she could then share with Geoffrey so as to strengthen their bond of friendship.”11 But often these friendships as described in hagiographic texts are male–female, with the female visionary friend to, and championed by, the male priest who authorizes her mystical activity for a suspicious church hierarchy. The female–female friendships are less pronounced in these texts, but they are definitively there, and upon further scrutiny they show that the visionary is really dependent on the friendships of women around her in order to succeed.

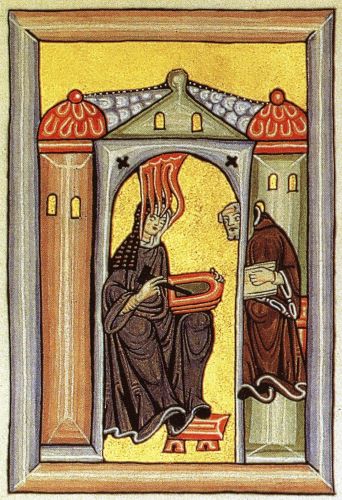

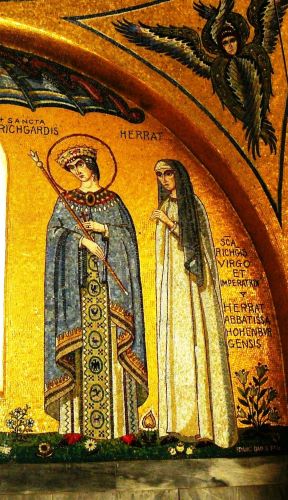

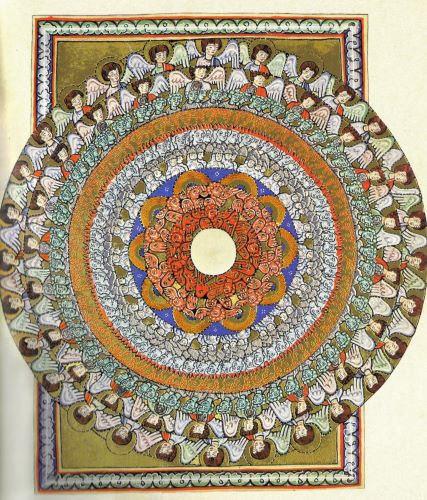

The twelfth-century visionary Hildegard of Bingen (c. 1098–1179) is in many ways the prototypical medieval woman mystic. She entered a Benedictine convent in Germany at a young age, at first hid her visions, and eventually described them and wrote them down, gaining both political and religious fame as a result. Her fame comes to us through her writings but also because of her correspondence with, and sanction by, important Church leaders at the time, Bernard of Clairvaux and Pope Eugenius III among them. But Hildegard’s story has the intertwining stories of other women at the margins. She is mentored by a woman, Jutta; she is encouraged by and loves deeply a nun at her convent, Richardis; and, as her fame and reputation spread, she mentors other women through epistolary correspondence, including the visionary Elizabeth of Schönau. Probing more deeply here, we can see that Hildegard’s network of women is what makes her position possible and that she very well understands this to be the case.

Hildegard’s hagiographer was Theodoric of Echternach (d. 1192), although he compiled much of Hildegard’s life from other sources and witnesses.12 From the first sentences of the vita, we are introduced to the importance of women and their friendship in Hildegard’s life, as her enclosure with the anchoress Jutta is her first defining moment: “When she was about eight years of age, she was enclosed at Disibodenberg with Jutta, a devout woman consecrated to God, so that, by being buried with Christ, she might rise with him to the glory of eternal life.”13 Jutta becomes a mentor, a teacher, and a friend to Hildegard, but their relationship was already partly forged through their families. Barbara Newman notes that “Jutta’s family was closely connected with Hildegard’s, and her conversion provided an ideal opportunity for Hildegard’s parents, Hilde-bert and Mechthild, to perform a pious deed. They offered their eight-year-old daughter, the last of ten children, to God as a tithe by placing her in Jutta’s hermitage. As a handmaid and companion to the recluse, Hildegard was also her pupil: she learned to read the Latin Bible, particularly the psalms, and to chant the monastic Office.”14 Hildegard left her large family for a new family of two, and until other nuns joined them when they established a new convent together, Jutta must have been the most important person in Hildegard’s life. Jutta’s friendship and mentorship would have been foundational, but she is rarely mentioned in Hildegard’s writings or vita, which point to a connection that is not as close a relationship as Hildegard will later forge. Franz Felten writes, “Hildegard speaks of her detachedly as a noble woman to whom she was consigned in disciplina. She does not call her magistra or even mention her name.”15 However, Hildegard is quoted in her vita, noting that it was Jutta to whom she first entrusts her visions: “A certain noblewoman to whom I had been entrusted for instruction, observed these things and laid them before a monk known to her.”16 It is the monk, of course, whose authority will carry validation of Hildegard’s visions, but it is her friend, Jutta, who is the first to know of them and who seeks out that authority.

While Hildegard’s life gives us some important insight into her relationship with Jutta, Jutta’s vita, by an unnamed author, shows us more depth in the friendship between the two women.17 Here, we learn that after Jutta’s death, Hildegard and two other nuns, “more privy to her secrets than the others,” take on the intimate task of washing and preparing her body.18 Later, Hildegard asks for and receives a vision explaining her friend’s death:

“When all these things had been reverently and fittingly completed, a certain faithful disciple [i.e., Hildegard] of the lady Jutta herself, one who had been the most intimate terms with her while she still lived in the flesh, devoutly desired to know what kind of passage from this life her holy soul had made.”19

The hagiographer, after describing the vision, confirms, “now the virgin to whom these things were shown was the lady Jutta’s first and most intimate disciple, who, growing strong in her holy way of life even to the pinnacle of all the virtues, had certainly obtained this vision before God through her most pure and devout prayer.”20 At the end of her life, Jutta is surrounded by nuns in a convent where she herself is prioress (Hildegard succeeds her in this position), but the vita is careful to point out that there are special relationships here.21 The three nuns who prepare her body are the keepers of her secrets, and Hildegard is given a vision of Jutta’s death because of their intimacy.

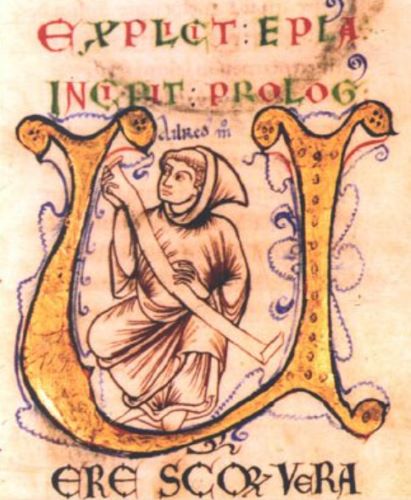

Jutta’s is the first friendship of Hildegard’s recorded life, but it reverberates in relationships that follow, first with a nun at her convent and then later through her letters to other women and visionaries. Hildegard’s first book of visions, the Scivias, took her ten years to write, and only then, she explains, with the help and assistance of two people: the nun Richardis von Stade, whom she mentored (Jutta’s niece), and the monk Volmar of Dibodenberg. Hildegard writes in her introduction:

“But I, though I saw and heard these things, refused to write for a long time through doubt and bad opinion and the diversity of human words, not with stubbornness but in the exercise of humility, until, laid low by the scourge of God, I fell upon a bed of sickness; then, compelled at last by many illnesses, and by the witness of a certain noble maiden of good conduct [Richardis] and of that man whom I had secretly sought and found, as mentioned above [Volmar], I set my hand to the writing.”22

Hildegard’s friendship with Richardis consumed her, and although Richardis is credited here with giving Hildegard the courage to write her book, her letters show the depth of that friendship and the pain it caused Hildegard when Richardis left the convent to form another.

Ulrike Wiethaus notes of these letters that they “equal in tragic passion and depth the letters between Héloïse and Abelard. . . . The intensity of images and dramatic involvement we sense in the visions is the same we detect in Hildegard’s feelings for Richardis.”23 This passion has sparked much academic discussion, casting the relationship between Hildegard and Richardis as mutually erotic or with Hildegard as a dominant figure, from whom Richardis feels she must escape.24 Hildegard’s efforts to keep Richardis with her and not moved to Bassum, where she had been elected abbess, are also the subject of many of her letters to Church figures, including Pope Eugenius. But these facts and speculations aside, we can still see the friendship at the core of what existed between these two nuns. Hildegard’s book is written only with the encouragement and love of Richardis, and, as with Jutta, her work is first dependent on a woman’s response before she disseminates it outward. It is hard to know what Hildegard’s relationship with Richardis was while they were together, because the evidence we have is in letters Hildegard wrote after Richardis has left and Hildegard’s great distress therein. Her retrospective response likely colors the account of their friendship.

One of these letters shows how this departure has almost led to a crisis of faith for Hildegard:

“Daughter, listen to me, your mother, speaking to you in the spirit: my grief flies up to heaven. My sorrow is destroying the great confidence and consolation that I once had in mankind. . . . Now, again I say: Woe is me, mother, woe is me daughter, ‘Why have you forsaken me’ like an orphan? I so loved the nobility of your character, your wisdom, your chastity, your spirit, and indeed every aspect of your life that many people have said to me: What are you doing?”25

Hildegard’s intense attachment to Richardis is positioned as that of both a mother and a daughter, but she also describes herself as Christlike and as an orphan in her grief. These mixed metaphors attempt to express the depth both of what Richardis meant to her and of what her loss now feels like. Peter Dronke analyzes the language of this letter, noting that it is “both intimate and heavy with biblical echoes. These can heighten, but also modify, what she is saying; they make the letter supra-personal as well as personal. Both aspects are vital to what is essentially a harsh confrontation between transcendent love and the love of the heart.”26 That Richardis’s support is so essential to Hildegard’s own intellectual and visionary output further underscores what the women meant to each other. She, along with the monk Volmar, are really seen as collaborators in the Scivias; the visions may be Hildegard’s, but the writing and formulation of them are with the help of her friends.27

We can see that this closeness extends to Hildegard’s letters regarding Richardis and how she is addressed concerning her. At Richardis’s death, her brother Hartwig, the archbishop of Bremen, writes to Hildegard with the news, acknowledging the close relationship forged between the two women:

“I write to inform you that our sister—my sister in body, but yours in spirit—has gone the way of all flesh, little esteeming that honor I bestowed upon her. . . . Thus I ask as earnestly as I can, if I have any right to ask, that you love her as much as she loved you, and if she appeared to have any fault—which indeed was mine, not hers—at least have regard for the tears that she shed for your cloister, which many witnessed.”28

Although the relationship between Hartwig and Hildegard was obviously fraught—she blames him for Richardis’s departure, and he refuses her entreaties to have her return—he recognizes the importance of his duty in letting Hildegard know and acknowledges the intimacy the women shared. Hildegard responds to him that God “works in them like a mighty warrior who takes care not to be defeated by anyone, so that his victory may be sure. Just so, dear man, was it with my daughter Rich-ardis, whom I call both daughter and mother, because I cherished her with divine love, as indeed the Living Light had instructed me to do in a very vivid vision.”29

Hildegard’s letters reveal that she was sought out as a mentor by both lay and religious women. Although these friendships were primarily epistolary, they show tenderness and intimacy despite the formal, biblical, and metaphoric language that Hildegard favors. Beverlee Sian Rapp concludes that the language she uses in her letters is different for the female correspondents than for the men: “Such comforting and supportive language is almost unheard in Hildegard’s letters to her male correspondents, but here, in a community of women, she does not hesitate to offer kind and supportive words, which may help a sister in God to deal with her troubles.”30 One unknown abbess—who appears to have previously known Hildegard in person—writes to her with affection but expresses sadness that she had not received a letter in return:

“It seems clear that I must accept with equanimity the fact that you have failed to visit me through your letters for a long time, although I am greatly devoted to you. . . . For if it is not granted to me to see your beloved face again in this life—and I cannot even mention this without tears—I will always rejoice because of you, since I have determined to love you as my own soul. Therefore, I will see you in the eye of prayer, until we arrive at that place where we will be allowed to look upon each other eternally, and to contemplate our beloved, face to face in all his glory.”31

Hildegard’s response is curt and a bit scolding, not reflecting at all the depth of feeling revealed in the abbess’s letter. As with Hildegard’s relationship with Richardis, this reminds us that not all friendships go both ways, and, as with all kinds of love, it can be unrequited or unequal.

Among Hildegard’s many letters to women, those to Elisabeth of Schönau have received the most attention. In Hildegard’s relationship with Elisabeth, whose visions began after Hildegard was known for hers, we can see how she passes along the kind of friendship that she has received, becoming the kind of mentor that she did not have from a fellow visionary. Newman notes the similarities between the two women: “Temperamentally, Elisabeth resembled Hildegard in many ways; she shared the older women’s physical frailty, her sensitivity to spiritual impressions of all kinds, and her need for public authentication to overcome initial self-doubt. Just as Hildegard had written in her uncertainty to Bernard, the outstanding saint of the age, so Elisabeth wrote to Hildegard.”32 Elisabeth reaches out to Hildegard in a lengthy and personal letter, immediately claiming a kinship and asking for advice—counsel she understands can only come from a woman in a similar position:

“I have been disturbed, I confess, by a cloud of trouble lately because of the unseemly talk of the people, who are saying many things about me that are simply not true. Still, I could easily endure the talk of the common people, if it were not for the fact that those who are clothed in the garment of religion cause my spirit even greater sorrow.”33

She explains the circumstances and contents of her visions, and why they are doubted, and begs for Hildegard’s advice and her stamp of approval in her closing words: “My lady, I have explained the whole sequence of events to you so that you may know my innocence—and my abbot’s—and thus may make it clear to others. I beseech you to make me a participant in your prayers, and to write back me some words of consolation as the Spirit of the Lord guides you.”34

Hildegard takes up her role as mentor and friend, encouraging Elisa-beth in the face of her detractors, but also showing what she has learned as a visionary. Ulrike Wiethaus calls their relationship a “professional friendship,” noting that “both women exchanged thoughts about their public ‘work,’ their calling, their literal profession as visionaries.”35 Hildegard writes, warning her of temptation because she is a holy vessel,

“So, O my daughter Elisabeth, the world is in flux. Now the world is wearied in all the verdancy of the virtues, that is, in the dawn, in the first, the third, and the sixth—the mightiest—hour of the day. But in these times it is necessary for God to ‘irrigate’ certain individuals, lest His instruments become slothful.”36

She closes by speaking to her own role as a visionary describing herself as a trumpet for God’s word in order that Elisabeth can better understand her own role:

“O my daughter, may God make you a mirror of life. I too cower in the puniness of my mind, and am greatly wearied by anxiety and fear. Yet from time to time I resound a little, like the dim sound of a trumpet from the Living Light. May God help me, therefore to remain in His service.”37

Hildegard uses her life as an example to Elisabeth, warning her of pride and demonstrating through her own example a language which Elisabeth can use to describe her role as visionary.

Elisabeth clearly takes her words to heart. She responds to Hildegard describing a vision and noting, “you are the instrument of the Holy Spirit, for your words have enkindled me as if a flame had touched my heart, and I have broken forth into these words.”38 Elisabeth ultimately wrote three books of her visions, the third written after this correspondence. Like Hildegard, Elisabeth would go on to lead her religious community, demonstrating how these women’s friendships successively influence others.39 Through the interconnections of Jutta, Richardis, Hildegard, and Elisabeth, we can see how these visionary women are in fact dependent on their friendships and relationships with each other and the support of women around them. The texts of Hildegard may not have existed without encouragement of Jutta and Richardis, or those of Elisabeth without Hildegard.

We can see the outlines of visionary women’s friendships a century later, again in Germany, in the phenomenon of the fourteenth-century Schwesternbücher, or sisterbooks. These books are records of many members of the same convent who experienced visions and revelations, and who wrote them down collectively. Albrecht Classen explains, “We know primarily of nine major convents where this phenomenon took place, all of them located within the Dominican province of Teutonia in the Southwest of modern Germany, in the Northeast of France, and in Switzerland.”40 These books recorded the lives of exemplary sisters and served as models of holy and pious behavior for the convent, but they also allow glimpses into convent life. The simple fact of their witness—that women were moved enough to write and preserve the memory of their sisters—demonstrates an act of female friendship. Generally, the books’ existences are in themselves testaments to friendship, but also their contents, as Gertrud Jaron Lewis points out, “represent a rich source of information about monastic women’s friendships.”41 The books describe the extraordinary (the visions, the charisms) and the everyday interactions among the sisters. We see their daily routines and a sense that these are women of all ages making a life together. For example, Mathilde van Dijk looks closely at the sisterbook from the community Saint Agnes and Mary at Diepenveen, suggesting that the books reflect an interest in the good works and charity of the nuns, practices that reflect their pious interior lives, rather than the vision or other outsized evidence of their holiness. The examples she gives of how the leaders of the convent are described demonstrate the kindness and care among the women:

“When the sub-prioress Liesbeth of Delft (d. 1423) insisted on helping to spread manure, the other sisters refused to allow it and took the spade from her. Eventually, she grabbed the mulch with both hands. . . . [For-mer prioress] Salome Sticken insisted on sitting with the youngest sisters in the choir, although her experience and age entitled her to a superior place.”42

However, many of the sisterbooks also support the lives and words of vision-ary women. The Engelthal sisterbook, for example, was formed at a Dominican monastery that was home to the German visionary Christine Ebner.

Why the sisterbooks were written and what their purposes were are somewhat unclear. They are part chronicle, part exempla, but the fact that they are written by the women of the convent in order to document the lives of their sisters is at the heart of what I am interested in here. I would like to look more closely at the sisterbook of the Monastery of St. Maria in Töss, in what is today Switzerland. The community there, according to Lewis, “had its origin in a beguinage in Winterthur. . . . The Töss monastery was officially incorporated into the Order of Preachers by Innocent IV in 1245; but even prior to this date, the nuns had for several years been spiritually cared for by the friars of Zürich.”43 While a few of the sisterbooks were written in Latin (Unterlinden and Adelhausen), the book at Töss is one of the seven written originally in the vernacular German,44 and, among its four extant complete manuscripts, one is the only illuminated copy of any of the sisterbooks.45 One of the writers is Elsbeth of Stagel (1300–c. 1360), who, Lewis notes, “became known as a writer, scribe, and translator, but was perhaps made most famous for her spiritual friendship and literary cooperation with Heinrich Suso.”46 Many of their extant letters survive, and she may deserve credit for a large portion of Suso’s work because she initially wrote down his visions and he used her text as a basis for his own.47

Elsbeth almost certainly wrote the life of Elizabeth of Töss, which is appended to the sisterbook and describes the visionary woman and her life at the convent. Sarah McNamer has argued convincingly that it is this Eliza-beth who is the subject of the Middle English hagiographies attributed to St Elizabeth of Hungary, but not the popular St Elizabeth of Hungary who was the daughter of the king (and with whom she appears to have been confused because she was also a member of the royal family).48 Elsbeth may have written the visions down as well, although the authorship is unclear, but she is clearly credited with Elizabeth’s vita.49 Elsbeth speaks with a certain pride about this royal nun, noting that she entered their order at thirteen and that she was the first virgin received in the order at their new foundation.50 We know from both her vita and Elizabeth’s Revelations that she develops a visionary bond with the Virgin Mary, with whom she dialogues. The sisterbook vita lays bare the kind of community support that allows that visionary activity to happen. In one scene of the vita, for example, one of the nuns has a dream vision where she sees the sisters arranged for matins, and, as they pray, their words appear to be pearls that fall from their mouths into a cup—but two pearls fall from Elizabeth’s mouth for each word she utters. Although this underscores Elizabeth’s holiness (the point of the vita, after all), it demonstrates how she is part of a communal life with women who are supporting and sharing her in her works.

The vita closes with an exhortation to the sisters to remember not only how Elizabeth was a model of devotional piety and excellence but how she supported and participated in the Order. Elsbeth points out how even though she was from a royal family, she lived the life of the Order in humility and poverty, an example to all the sisters.51 This emphasis on the community of nuns demonstrates how important that community is to the making and supporting of the visionary (Elizabeth) but also to the construction of the story of the community in the sisterbook. Here, the friendships among the women create a network of support that manifests itself in the text, giving the women exempla but also recording their lives.

Catherine of Siena is not in the formal community of a convent and her friends are mentioned in supporting roles throughout her vita, although we also have more direct evidence of women as her friends because they served as scribes for her, pointing beyond intimacy and a support system to an active role in shaping the life of the visionary women and her legacy afterward. This is not unique to Catherine. As we have seen, the nun Richardis acted as a scribe and collaborator for Hildegard. Another famous German mystic, Mechthild of Hackeborn, was assisted by Gertrude of Helfta (who herself was assisted by fellow nuns in the writing of her own visions). These collaborations are more than just scribal activity; the women often serve as the sounding boards for their visionary friends, the first to hear the visions as they help shape them and write them down.

In Catherine’s case, women who are part of her famiglia of followers act as scribes for some of her many letters. Kimberly Benedict reads in the scribes’ notations at the ends of Catherine’s letters a “provocative kind of dialogism,” which uses humor to make the women’s presences known: “After transcribing the holy woman’s messages, the assistants would conclude with brief remarks of their own. Whereas Catherine’s comments generally consist of pious instructions and exhortations, however, the scribes’ messages tend to be humorous, shifting the letters’ focus from the sacred to the absurd. For example, the scribes identify themselves using unflattering nicknames such as ‘fat Alessa,’ ‘crazy Giovanna,’ and ‘Cecca the time-waster.’ While the names are inherently silly, they are also satirical insofar as they give an impertinent twist to the humility tropes typically used by medieval religious writers.”52

These marks of humor throughout the letters also demonstrate a sign of affection between Catherine and the women of her famiglia, in addition to the intimacy inherent in the scribal relationship where Catherine dictates personal thoughts. For example, in one of her letters to a woman named Monna Agnesa Malavolti, a member of the third order of lay Dominicans (as was Catherine) and a woman from an important Siennese family, Catherine encourages her to take heart and devote herself to Mary Magdalen among other female saintly role models. She and her scribe, Cecca, close the letter, written during a pilgrimage to the Dominican monastery in Montepulciano, in a way that demonstrates their close bond as well as the slippage between the writer and the scribe:

In the name of Christ and in my name encourage and bless Monna Raniera and all my other daughters. Bless and encourage Caterina di Ghetto a thousand times for me and for Alessa and all the others who are here with me. Really, we felt like saying, “Let’s make three tents here”! because truly it seems like paradise to us to be with these very holy virgins. They are so taken up with us that they won’t let us leave, and we are always bewailing the fact that we are leaving. . . . I Cecca am almost a nun, because I’m beginning to chant the Office with all my might along with these servants of Jesus Christ!53

Suzanne Noffke, who has translated and edited all of Catherine’s letters, suggests that the “my name” in the first sentence is Catherine but that the “me” in the remaining parts are Cecca, her scribe and companion (Francesca di Clemente Gori). She notes that she thinks the Alessa here is Alessa dei Saracini, “a close and constant member of Catherine’s circle.”54 This movement from Catherine’s voice (“bless . . . all my other daughters”) to Cecca’s (“Bless . . . Caterina . . . for me and for Alessa and for all the others who are here with me”) demonstrates this close circle of women friends with Catherine at its center. Catherine is the main voice, the purpose, but she is surrounded by a group that knows her and each other well. Even Cecca’s nearly humorous signoff—“I . . . am almost a nun”—shows a camaraderie and closeness among the women and their correspondence.

It is significant that the scribes for Catherine sign their names—often these women collaborators are lost to anonymity—showing that they felt themselves to be integral to Catherine’s mission and messages. However, it is equally significant that the women’s names appear only on her early letters and that eventually her letter writing is taken over by male scribes. The humorous epithets give way to more pro-forma signatures from Catherine, and the scribes are no longer clearly identified. The women move to the background of Catherine’s life, even though they continue to travel with and support her as part of her family.

In this light, it is telling that the many women we see and know of in her letters are all but absent from her vita. Her mother, Lapa, and some sisters and sisters-in-law get mentioned, but the names of Alessa and Cecca are often missing although they are sometimes named as a source of a story or as an additional witness to a miracle. The women who have roles of note are those who benefited from Catherine’s intercessional prayers or the miracles attributed to her. For example, in describing how Catherine cured a woman, Monna, of a possession by an evil spirit, Raymond of Capua writes: “Present at this miracle, besides Monna Bianchina, who is still alive, were Friar Santi, the holy virgin’s companions Alessia and Francesca, her sister-in-law Lisa, and about a score and a half of other people of both sexes, whose names I cannot give as I have no record of them.”55

Catherine’s female friends and their roles as witnesses and important sources for Catherine’s life are acknowledged by Raymond at the end of his vita. He vouches for them as sources of reliable information in reporting on Catherine’s life:

“But in case I may seem to be simply misleading my readers by mentioning these people in a merely general way, I shall list their names, both the men and the women, separately. These are the people to be believed, not me! . . . Here are their names. I will begin with the women, as these were with Catherine practically all the time.”56

Here, Raymond also inadvertently demonstrates how close Catherine was to her female friends—they were with her “practically all the time.” Catherine does not exist without them.

Raymond goes on to describe and praise the women closest to Catherine. He notes that Alessa (here Alessia) was the recipient of Catherine’s intimacies:

“Alessia of Siena, one of the Sisters of Penance of St. Dominic, though she was one of the last to put herself under Catherine’s guidance, was nevertheless in my opinion the most perfect of all of them in virtues. . . . She was so assiduous and perfect that if I am not mistaken the holy virgin revealed her most intimate secrets to her towards the end and desired that after death the others should accept in her stead and take her as their model.”57

He continues to describe Francesca: “a most religious woman, united to God and Catherine in truest affection. . . . Francesca, like many others, gave me much information.”58 He closes by noting of her sister-in-law, Lisa,

“Of Lisa I shall say no more, as she is still alive, and also because she was the wife of one of Catherine’s brothers. I should not like the unbelievers to be able to cast doubts on her evidence, though as a matter of fact I have always found her to be the kind of woman who does not tell lies.”59

Although studies of Catherine typically identify her in relation to the men in her life (Stephen Maconi, Raymond of Capua, Thomas Caffarini, etc.), this closer look at her letters and her vita demonstrates the absolutely essential role that the women in her life played—especially Alessa, Cecca, and Lisa. These women not only supported her physically as they traveled but also worked as her scribes—essential for Catherine’s establishment of her reputation through her extensive letter-writing network. Finally, they serve as the sources for Raymond’s vita, giving him the stories and the personality behind the woman he knew and championed. Even Raymond realizes how much he is in their debt.

I would like to conclude by looking at “The Life and Good End of Sister Marie,” which describes the death of an English visionary nun after the Reformation. Compared with her more famous predecessors, named and described in this essay, Marie Champney’s name has largely been lost to history. Perhaps she would have had a rich hagiographic tradition in the vein of her predecessors if her story had taken place before the Dissolution; instead, her Life serves as a testament to the women who tried to keep that tradition somewhat alive by documenting and honoring their friend in her death; they may not have actually written her Life, but they certainly provided its details. In her Life, there are many of the themes of friendship, community support, and mutual affection that we have observed in other vitae and texts, but here they are more apparent as Marie and her sisters are exiled and are, in many senses, alone without some of the resources (human or monetary) available to them.

Marie was an English Bridgettine nun and had religious visions throughout her childhood. While abroad in Flanders, she had a vision encouraging her to become a nun and to remain there, so she joined the then exiled house of Syon Abbey, where the habits matched her visions and where, Ann Hutchison notes, “Mary felt she had been destined.”60 Syon in exile was not the powerful and supported community that it was in England. The nuns were having trouble finding a permanent home abroad and the exile took its toll on them emotionally, spiritually, and physically. As Hutchison describes, “Sometime in the autumn of 1578, at least ten, and perhaps more, of the younger members of the monastery were sent to England. The decision to send them had been made by the Abbess and Confessor-General at a time when Calvinists were ravaging the religious establishments in the Low Countries, attacks from which women’s houses in particular suffered terrible horrors.”61 The vignettes about Marie’s life focus on her return to England. The authorship is unknown, although Hutchison suggests that a likely candidate is the householder (male or female) who housed Marie in England. Marie and her sisters suffer a difficult channel crossing and then are hidden in houses throughout London with recusant Catholics, but she, like other sisters, probably because of the terrible conditions in Flanders, immediately fall very ill. They cannot maintain their community together in Protestant England, and their separation is both emotional and physical.

The description of these sisters in exile reveals how friendships were forged in that crossing and how their physical separation in various houses was overcome when their sister Marie was so deathly ill—perhaps precipitated by the loss of that community of sisters around her. As part of the Bridgettine Rule, two sisters must sit with the ailing nun night and day once it is clear that she will die. These sisters are called from other parts of the city to be with Marie:

“A Thursdaye, one sister was come vp and founde her prettie and hartye, with no smale comforte to both sides. Inso much that Sister Marye called the goodman, which had fetched so quicklie vp one of her best frendes; therefore gevinge him—by comon consente—a very fayre corpus case of crim-son inbrodered with golde, of her one makinge, to remember her at the holye Aulter, in fine and hansome makinge.”62

Despite the danger inherent in the sisters coming together in London, where they are essentially in hiding by living separately, they do so to usher Marie into her death.

The love they show her at her death, that they show all their sisters, truly underscores the intimacy of the nunnery and especially one in exile and peril:

So sinkinge downe hir eye liddes, while [the priest] blessed hir and absolved her at hir passinge; never breathinge, nor gaspinge more, but holdinge the holie candle still fast in her hande, when hir holie soule was yeelded vp for hir sisters to close hir eyes and kisse their sweete Maries coarse, which was as white, as the white virgins waxe, her eyes as plumbe and as comelie as any childes in a slumber, her cheekes no leaner then in tyme of healthe, and hir cowntenaunce as asweete as the smyling babes.63

Although Marie is never a candidate for sainthood, the vita-like narrative describing her visionary past and her holy death allows us to place her among the other women discussed here. For Marie, the isolation and hardships of the recusant nuns encourages a special kind of friendship among her sisters. Unlike a nun in a convent, surrounded always by the women who support her, Marie’s friends must come—at some peril—to see her to her death. These bonds are apparent in this deathbed scene where they are closing her eyes and kissing her corpse, keenly aware of the loss of their own. Like Marie, the vibrant hagiographic tradition and its associated texts about and by visionary women has become a shadow of itself. It is the end of an era.

Each of the women written about here stands somewhat outside the normal structures of a convent in addition to her outsider status as visionary and mystic. Hildegard is for a long time enclosed as an anchoress; the sister-books were written seemingly without any male or Church oversight within their Dominican convents; Catherine of Siena was a member of the Dominican third order, and Sister Marie was at first away from her homeland and then hiding within it. For all these women, the isolation of their situations led to intense female friendships with the women around them. And yet these friendships each manifest in markedly different forms: sometimes as replacement family, as mentoring or mentored, or as physical and emotional support network. The contours of visionary women’s friendships are complex, resisting the taxonomy laid out by Aelred and instead forging different bonds. Scrutiny of these texts, among others, shows that despite the idea that these women somehow were alone, lost until the men who would eventually champion them crossed their paths and recognized their gifts, we see instead women who depend on a network of other women to live the life of the visionary and what it entailed.

Endnotes

- See, for example, the collection edited by Catherine Mooney, Gendered Voices: Medieval Saints and Their Interpreters (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 1999); John Coakley, Women, Men, and Spiritual Power: Female Saints & Their Male Collaborators (New York: Columbia University Press, 2006), and H. M. Canatella, “Long-Distance Love: The Ideology of Male-Female Spiritual Friendship in Goscelin of Saint Bertin’s Liber confortartorius,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 19 (2010): 35–53. My own work on the subject can be found in Jennifer N. Brown, “The Chaste Erotics of Marie d’Oignies and Jacques de Vitry,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 19 (2010): 74–93, and Fruit of the Orchard: Catherine of Siena in Late Medieval and Early Modern England (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018).

- Karma Lochrie, “Between Women,” in The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women’s Writing, ed. Carolyn Dinshaw and David Wallace (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 70–88, at 70.

- Jane Tibbets Schulenburg, Forgetful of Their Sex: Female Sanctity and Society ca. 500–1100 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998), 309. See especially the entire chapter on “Gender Relationships and Circles of Friendship” for the history of Church attitudes toward friendship among men and women and how these change.

- Marsha L. Dutton dates it between 1164 and 1167, in Aelred of Rievaulx: Spiritual Friendship ed. Marsha L. Dutton and trans. Lawrence C. Braceland, SJ (Collegeville, MN: Cistercian Publications, 2010), 22; for more on Spiritual Friendship, see Dutton, “The Sacramentality of Community in Aelred,” in A Companion to Aelred of Rievaulx, ed. Marsha L. Dutton (Leiden: Brill, 2017), 246–67; as well as Domenico Pezzini, “Aelred’s Doctrine of Charity and Friend-ship,” in A Companion to Aelred of Rievaulx, 221–45. Nathan Lefler, Theologizing Friendship: How Amicitia in the Thought of Aelred and Aquinas Inscribes the Scholastic Turn (Cambridge: James Clarke, 2014), describes the classical sources and basis for Aelred and his relation to the later Thomas Aquinas’s theorizing of spiritual friendship.

- Aelred of Rievaulx: Spiritual Friendship, 124; The Latin can be found in Aelredi Rievallensis, De spiritali amicitia, in Aelredi Rievallensis Opera Omnia, ed. A. Hoste and C. H. Talbot (Turnhout: Brepols 1971), 348.

- Lochrie, “Between Women,” 72.

- Dutton, “The Sacramentality of Community in Aelred,” 246.

- Dutton, “The Sacramentality of Community in Aelred,” 251.

- Schulenburg, Forgetful of Their Sex, 349.

- Notably, Judith M. Bennett’s idea of the “lesbian-like” has been useful for many scholars to read same-sex desire in the medieval past. This has been responded to and problematized by scholars but remains an important category of understanding medieval same-sex female relationships. See “‘Lesbian-Like’ and the Social History of Lesbianisms,” Journal of the History of Sexuality 9 (2000): 1–24. Other scholars have looked at the convent through the lens of queer desire. See, for example, Lisa M. C. Weston, “Virgin Desires: Reading a Homoerotics of Female Monastic Community,” in The Lesbian Premodern: A Historical and Literary Dialogue,ed. Noreen Giffney, Michelle Sauer, and Diane Watt (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2011), 93–104. Most recently, Laura Saetveit Miles reads Margery Kempe and Julian of Norwich’s meeting through a queer lens in “Queer Touch between Holy Women: Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe, Birgitta of Sweden, and the Visitation,” in Touching, Devotional Practices, and Visionary Experience in the Late Middle Ages, ed. David Carrillo-Rangel, Delfi I. Nieto-Isabel, and Pablo Acosta-García (New York: Palgrave, 2019), 203–35.

- Canatella, “Long-Distance Love,” 48.

- For more on the compilation of Hildegard’s hagiographic corpus, see the introduction to Jutta and Hildegard: The Biographical Sources, ed. Anna Silvas (Turnhout: Brepols, 1998).

- Jutta and Hildegard, 140; the Latin can be found in Godefrido et Theodorico Monachis, Vita Sanctae Hidlegardis, in AASS, 17 Sept, V, 91–130, at 91>.

- Hildegard of Bingen: Scivias, trans. Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop, introd. Barbara J. Newman, pref. Caroline Walker Bynum (New York: Paulist Press, 1990), 11.

- Franz J. Felten, “What Do We Know about the Life of Jutta and Hildegard at Disibodenberg and Rupertsberg?,” trans. John Zaleski, in A Companion to Hildegard of Bingen, ed. Debra Stoudt, George Ferzoco, and Beverly Kienzle (Leiden: Brill, 2014), 15–38, at 26.

- Jutta and Hildegard, 159; “Sed quaedam nobilis femina, cui in disciplina eram subdita, haec notavit, et cuidam sibi notae monachae,” Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, 103.

- For speculation on the authorship of Vita domnae Juttae inclusae, see Jutta and Hildegard, 47–50.

- Jutta and Hildegard, 80. The Latin can be found in Franz Staab, “Reform und Reformgruppen im Erzbistum Mainz. Vom ‘Libellus de Willigisi consuetudinibus’ zur ‘Vita domnae Juttae inclusae,’” in Stefan Weinfurter and Hubertus Seibert, Reformidee und Reformpolitik in Spätsalisch-Frühstaufischen Reich: Vorträge de Tagung der Gessellschaft für Mittelrheinische Kirschengeschichte Vom 11. Bis 13. September 1991 in Trier (Mainz: Selbstverlag der Gesekkschaft, 1992), 119–88, at 184.

- Jutta and Hildegard, 81–82; Staab, “Reform und Reformgruppen,” 185.

- Jutta and Hildegard, 83; Staab, “Reform und Reformgruppen,” 186.

- The titles of abbess and prioress and leader are all used to describe Jutta and then Hildegard, although at the beginning there was no formal convent—just women enclosed together. Some of this is laid out in Felten, “What Do We Know?,” 15–38.

- Hildegard of Bingen: Scivias, 60; the Latin can be found in Hildegardis Scivias, ed. Adelgundis Führkötter OSB (Turnholt: Brepols, 1978), 5–6.

- Ulrike Wiethaus, “In Search of Medieval Women’s Friendships: Hildegard of Bingen’s Letters to Her Female Contemporaries,” in Maps of Flesh and Light: The Religious Experience of Medieval Women Mystics, ed. Wiethaus (Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, 1993), 93–111, at 105.

- See, for example, Kimberly Benedict’s discussion of Richardis in Empowering Collaborations: Writing Partnerships between Religious Women and Scribes in the Middle Ages (New York: Routledge, 2004), 55–56.

- “Letter 64: Hildegard to Abbess Richardis,” in The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen, vol. 1, trans. Joseph L. Baird and Radd K. Ehrmann (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), 143–34, at 144; the Latin can be found in “Epist. LXIV: Hildegardis ad Richardem Abbatissam,” in Hildegardis Bingensis Epistolarium, Pars Prima I-XC, ed. L. Van Acker (Turnholt: Brepols, 1991), 147–48, at 147>.

- Peter Dronke, Women Writers of the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), 157.

- This view of Hildegard’s writing is seen early in Hildegard studies and persists.

- “Letter 13: Hartwig, Archbiship of Bremen to Hildegard,” in Letters, vol. 1, 49–50, at 50; “Epist. XIII: Hartvvigvs Archiepiscopvs Bremensis ad Hildegardem,” Hildegardis Bingensis Epistolarium, 29.

- “Letter 13r: Hildegard to Hartwig, Archbishop of Bremen,” in Letters, vol. 1, 51; “Epist. XIIIR, Hildegardis ad Hartvvigvm Archiepiscopvm Bremensem,” Hildegardis Bingensis Epistolarium, 30–31, at 30.

- Beverlee Sian Rapp, “A Woman Speaks: Language and Self-Representation in Hildegard’s Letters,” in Hildegard of Bingen: A Book of Essays, ed. Maud Burnett McInerney (New York: Garland, 1998), 3–24, at 22.

- “Letter 49: An Abbess to Hildegard,” in Letters, vol. 1, 49–50, at 50; “Epist. XLIX: Abbatissa ad Hildegardem,” Hildegardis Bingensis Epistolarium, 119–20.

- Barbara Newman, “Hidlegard of Bingen: Visions and Validation,” Church History 54 (1985): 163–175, at 173.

- “Letter 201: The Nun Elisabeth to Hildegard,” Letters of Hildegard of Bingen, vol. 2, trans. Joseph L. Baird and Radd K. Ehrmann (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 176–79, at 176. The Latin can be found at https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/letter/123.html (accessed September 23, 2019).

- “Letter 201: The Nun Elisabeth to Hildegard,” Letters, vol. 2, 176–79, at 179; https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/letter/123.html (accessed September 23, 2019).

- Wiethaus, “In Search of Medieval Women’s Friendships,” 103.

- “Letter 201r: The Nun Elisabeth to Hildegard,” Letters, vol. 2, 180–81, at 180; “Epist. CCr: Hildegardis ad Elisabeth Monialem,” Hildegardis Bingensis Epistolarium, 456–57, at 457.

- “Letter 201r: Hildegard to the Nun Elisabeth,” Letters, vol. 2, 180–81, at 181; “Epist. CCr: Hildegardis ad Elisabeth Monialem,” Hildegardis Bingensis Epistolarium, 456–57, at 457.

- “Letter 202/203: Elisabeth to Hildegard,” Letters, vol. 2, 181–85, at 181; https://epistolae.ctl.columbia.edu/letter/124.html (accessed September 23, 2019).

- María Eugenia Góngora, “Elizabeth von Schönau and the Story of St Ursula,” in Mulieres Religiosae: Shaping Female Spiritual Authority in the Medieval and Early Modern Periods,ed. Veerle Fraeters and Imke de Gier (Turnhout: Brepols, 2014), 17–36, at 19.

- Albrecht Classen, The Power of a Woman’s Voice in Medieval and Early Modern Literatures (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2007), 245. He notes that these convents are “Adelhausen, Diessenhofen, Engeltal, Gotteszell, Kirchberg, Oetenback, Töss, Unterliden, and Weiler” (245). For individual descriptions of these convents and the contents of their books, see Gertrud Jaron Lewis, By Women, for Women, about Women: The Sister-Books of Fourteenth-Century Germany (Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies, 1996).

- Lewis, By Women, for Women, about Women, 222.

- Mathilde van Dijk, “Female Leadership and Authority in the Sisterbook of Diepenveen,” in Mulieres Religiosae, 243–264, at 259.

- Lewis, By Women, for Women, about Women, 21.

- Claire Taylor Jones, Ruling the Spirit: Women, Liturgy, and Dominican Reform in Late Medieval Germany (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2017), 57.

- Lewis, By Women, for Women, about Women, 23.

- Lewis, By Women, for Women, about Women, 24.

- See, for example, Albrecht Classen, “From Nonnenbuch to Epistolarity: Elsbeth Stagel as a Late Medieval Woman Writer,” in Medieval German Literature: Proceedings from the 23rd International Congress on Medieval Studies: Kalamazoo, Michigan, May 5–8, 1988, ed. Classen (Göppingen: Kümmerle Verlag, 1989), 147–70.

- See the introduction in Sarah McNamer, The Two Middle English Translations of St Elizabeth of Hungary (Heidelberg: Universitätsverlag C. Winter, 1996).

- There are no English translations of the sisterbooks. I have excerpted here from the German editions, as well as used the French translation: Jeanne Ancelet-Hustache, La Vie Mystique d’un Monastère de Dominicanes au Moyen Age D’après la Chronique de Töss (Paris: Perrin, 1928); Kleinere mittelhochdeutsche Erzählungen, Fabeln und Lehrgedichte. I. Die Melker Hand-schrift, ed. Albert Leitzmann (Berlin: Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, 1904), 98.

- Kleinere mittelhochdeutsche Erzählungen, 101.

- Kleinere mittelhochdeutsche Erzählungen, 121.

- Kimberly Benedict, Empowering Collaborations: Writing Partnerships Between Religious Women and Scribes in the Middle Ages (New York: Routledge, 2004), 32.

- Suzanne Noffke, ed., “Letter T61/G183/Dt2 To Monna Agnessa Malavolti and the Mantellate of Siena,” in The Letters of Catherine of Siena Volume I (Tempe: Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 2000), 4–5.

- Noffke, “Letter T61/G183/Dt2 To Monna Agnessa Malavolti and the Mantellate of Siena,” 5n17.

- Raymond of Capua, The Life of St. Catherine of Siena by Blessed Raymond of Capua, trans. George Lamb (Rockford, IL: Tan Books and Publishers, 1960, repr., 2003), 249; the Latin can be found in Raimondo da Capua, Legenda maior, ed. Silvia Nocentini (Firenze: Edizioni del Galluzzo, 2013), 318.

- The Life of St. Catherine of Siena, 309; Legenda maior, 366–67.

- The Life of St. Catherine of Siena, 309–10; Legenda maior, 367.

- The Life of St. Catherine of Siena, 310; Legenda maior, 367.

- The Life of St. Catherine of Siena, 311; Legenda maior, 367.

- Anne M. Hutchison, “Mary Champney: A Bridgettine Nun under the Rule of Queen Elizabeth I,” Birgittiana 13 (2002): 3–32, at 4.

- Hutchison, “Mary Champney,” 4.

- Ann M. Hutchison, “The Life and Good End of Sister Marie,” Birgittianna 13 (2002): 33–89, at 73.

- Hutchison, “The Life and Good End of Sister Marie,” 85.

Chapter 1 (15-35) from Women’s Friendship in Medieval Literature, edited by Karma Lochrie and Usha Vishnuvajjala (Ohio State University Press, 07.11.2022), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.