Insights into the local sociability and networks of the ‘middling’ strata of medieval London society.

By Dr. Justin Colson

Senior Lecturer in Urban and Digital History

Centre for the History of People, Place and Community

Institute of Historical Research

School of Advanced Study

University of London

Introduction

One of Caroline Barron’s articles set out to find the ‘small people’ of medieval London, drawing upon late fourteenth-century scrivener Thomas Usk’s distinction between the ‘worthy persons and the small people’.1 Usk was referring to the supporters of John of Northampton, especially the lesser artisans and craftsmen, and yet, perhaps counter-intuitively, those of such relatively humble status, but who did not run afoul of the authorities, are less well documented than those even further down the social spectrum. The most marginal individuals, such as fraudsters, prostitutes and petty criminals, can be found throughout London’s late medieval court records. At the upper levels of urban society, members of London’s ‘merchant class’, defined by Sylvia Thrupp as the liverymen of the greater companies, tend to be documented well enough to build comprehensive and meaningful biographies.2 This is especially true when our focus is restricted, as it often tends to be, to that even narrower subset of merchants who sought and achieved political office as common councilmen, aldermen and mayors.

The medieval Londoners for whom it is hardest to build biographies are those who fell between the two extremes of fortune and notoriety: the artisans, retailers and members of the mercantile companies who never made it to the ranks of the livery or the top of the league tables of international trade.3 This essay seeks to build on Caroline Barron’s inquiry into ‘the small people’ and to construct something of a ‘biography’ of a group of middling people in late medieval London. Rather than focusing upon an individual or an institutionally defined group of individuals who practised the same trade or who were members of the same parish, this chapter explores the history of one inn and the people connected with it over the course of the fifteenth century. Inns provided a unique combination of hospitality for travellers and sociability for locals, apparently avoiding some of the negative associations of other drinking establishments, such as alehouses (a distinction discussed below). Examining a range of documents, especially those which were witnessed by, or otherwise had the involvement of, innkeepers, gives a new insight into the local sociability and networks of the ‘middling’ strata of medieval London society.

Uses of Inns and Taverns

The social role of drinking establishments in the late medieval period has received rather less attention than might be expected, and medieval London’s inns have, as yet, received no dedicated comprehensive studies. Although there are some valuable general studies of inns, taverns and alehouses in the middle ages, this essay will also draw on the more extensive literature on the cultural history of drinking, and of drinking places, in the early modern period to help to build a rich picture of the varied uses of the semi-public, semi-private spaces of taverns and inns.4

The tripartite division between inns, which provided accommodation and a full hot-food service; taverns, which sold wine; and alehouses, which sold only ale, is well rehearsed, although in practice the boundaries could be a little blurred.5 It certainly seems to have been the case that alehouses often catered to travellers and inns often entertained locals, even if taverns might have maintained control over the retailing of wine. In London especially, inns and taverns had developed a notable sideline as restaurants during the fifteenth century, catering to the nobility, organizations and merchants.6 The reputations for respectability of the different types of establishment also seem to have been less clear-cut than might be imagined. Historians have perhaps too often tended to assume that medieval drinking houses were somewhat seedy environments.7 It is true that Judith Bennett’s account of women’s roles in brewing and selling ale emphasized the association of ale-selling with corruption, dishonesty and, if not actual prostitution, then at least sexual suggestion and flirtation.8 However, the social world of the tavern was much more complex.9 In practice, many of those joining in the most boisterous drinking games included figures of authority, such as the parish constable noted as having attempted to drink two gallons of ale from a stone pot, and having passed out for the whole of the next day, in Layer Marney, Essex, in 1604.10

Many of the most negative anecdotes relate to alehouses, and it would seem as though inns were the more respectable drinking establishments. Most obviously, they were much larger, requiring greater capital to own and operate, and therefore tended to be run by more respectable landlords than the frequently somewhat marginal alehouse keepers, who often improvised a normal domestic space into a ‘public house’. John Hare suggested that, by the sixteenth century at least, provision of locked chambers for guests was a key feature of inns, with even those in provincial towns sometimes providing upwards of a dozen guest rooms, while Beat Kümin calculated that early modern inns had on average forty to fifty beds.11 Travel accounts from before 1500 reported that elites including prelates, diplomatic envoys and high-ranking pilgrims routinely stayed at inns.12 Respectable men and women of knightly and gentry families also patronized inns, with both the Stonors (who, interestingly, let their own property and instead stayed in public inns) and Pastons staying in such establishments in London.13 Older studies have implied that the respectability of inns in the middle ages declined during the early modern period, although both Kümin and Hare suggested that this model required a lot more nuance: there was no shortage of ‘respectable’ opportunities for men and women to attend, or indeed to run, taverns and inns in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as there had been in the fourteenth and fifteenth.14 There are, however, plenty of indications that not all medieval inns were as ‘respectable’ as the contrast with alehouses might suggest. Erasmus’s discussion of inns throughout Europe was certainly less than flattering, highlighting again the importance of a female host of ‘handsome of carriage’ and the somewhat questionable attitude to service (especially in Germany), where eighty or ninety people of every social rank were made to eat together in a single sitting and change was rarely given at the reckoning.15 While there were undoubtedly differences between inns and alehouses, they were certainly nuanced.

Nonetheless, there were important ways in which inns and taverns particularly served unambiguously legitimate social functions in pre-modern cities. Phil Withington has argued that legitimate sociability and ‘keeping company’ were integral to the establishment of corporate and civic identities and solidarities; and while haunting taverns too much was to be avoided, they were still appropriate venues for respectable sociability.16 What was, and was not, acceptable in terms of the use of drinking establishments was socially and contextually specific. Drinking with one’s peers was absolutely routine and integral to the mechanisms of social capital for the elites, but was confined to inns and taverns. The boisterous drinking of the poor in alehouses was always much more suspect.17 The legitimacy of a visit to a tavern or inn depended upon its purpose: if there was any serious purpose, it was perfectly legitimate for anyone of any status or sex to visit a drinking house. Yet haunting taverns for its own sake was certainly seen as a danger: Thomas Dekker’s satirical Gull’s Hornbook (1609) suggested ironically that the man who ‘desires to be a man of good reckoning in the city … take his continual diet at a tavern, which out of question is the only rendezvous of boon company’.18 It is also important to remember that not only were there a multitude of legitimate reasons for respectable men and women to visit all manner of drinking houses, including alehouses, but that in practice any one such establishment would host any number of ‘companies’ of drinkers, all engaged in their own conversations, business or drinking games.19

A wide range of activities which took place within inns and taverns could be classed as legitimate forms of sociability. According to Clark, both taverns and inns were ‘places for business to be done; investments arranged, lawyers and physicians consulted’.20 From the early seventeenth century dedicated tavern societies used the private rooms available within a tavern or inn to provide particular forms of sociability, such as the Convivium Philosophicum which met at the Mitre tavern around 1611.21 This use of inns and taverns for organized cultural activities was nothing new. Anne Sutton has convincingly argued that the Tumbling Bear on Cheapside was the meeting place of the fraternity known as the Puy, which met during the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries to compose a new chant royale.22 The socially prestigious Jesus guild, which met in St. Paul’s cathedral from the mid fifteenth to mid sixteenth centuries, also made extensive use of inns and taverns, including in 1514 when the assistants of the guild convened at the Mitre in Cheapside for the ‘makyng of the ordenances’.23 Inns and taverns could, then, certainly be quite respectable places. Indeed, the inn that features most prominently in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, the Tabard, was explicitly described as a ‘gentyle tavern’ and was a place in which a wife, a prioress and a monk all saw fit to stay.24

The important place of the inn in the social and economic life of the city also emerges from sixteenth-century theatre. The anonymous Famous Victories of Henry V, widely considered to be Shakespeare’s source for Henry IV and Henry V, offered a lively description of the ‘old tavern’ on Eastcheap.25 Shakespeare developed this image of the prince’s affray in a way that transposed the Boar’s Head of his own era into the medieval period for, as John Stow was at pains to point out, there was no tavern on Eastcheap at that time, only cookshops.26 Hostess Quickly sets out her case against Falstaff in Henry IV Part 1 with what Nina Levine has described as an ‘outrageously detailed account of the material circumstances’ to give authority and authenticity to her claim: ‘Thou didst swear to me upon a parcel-guilt goblet, sitting in my Dolphin chamber, at the round table, by a sea-coal fire’.27 Levine argued that Shakespeare’s use of the tavern setting ‘delineates a world whose ethics are rooted as much in the business practices of London’s middling sort as the holiday festivities of popular culture’ and, furthermore, emphasized the place of credit and centrality of contracts in that world.28 In theatre, the tavern or the inn stood for the social world of London and the commercial mind-set that went with it; there was no contradiction between the tavern as place of mischief and of business.

Barbara Hanawalt referred to the medieval tavern as a ‘permeable domestic space’, where gendered work replicated that of a domestic house: wives and daughters oversaw the running of the house and supervised servants, while husbands supervised guests and looked after provisioning. Female employees, and even daughters and wives, were at risk of being pimped, while ordinary female patrons were not beyond suspicion.29 Again, this was highly contextual: women’s use of public space was ‘neither simple nor free’ but certainly could include taverns and inns.30 Laura Gowing has persuasively argued that while the late medieval and earlier early modern periods might not have seen the inclusiveness and parity between the sexes that the theory of the growth of ‘separate spheres’ after 1650 has implied, gendered spaces were certainly permeable.31 A woman’s place might have been in the household, but that was not synonymous with the physical limits of the house. Indeed, witness testimonies described women routinely moving around the streets, shops and inns and taverns of their neighbourhoods.32

Meanwhile, Shannon McSheffrey’s analysis of matrimonial litigation in the London Consistory Court has suggested that, outside of homes and churches, drinking houses such as inns, taverns and alehouses were the most common locations for the making of marriage contracts. The testimonies describing such marriages, whether testifying for or against, do not appear to have made any judgement as to the drinking house having been unsuitable or disreputable. Indeed, McSheffrey argued that, especially for those of middling and lower status, the tavern served as a home away from home. Marriages were, she argued, most often contracted and announced to those closest to the couple in a domestic or quasi-domestic space before being announced more widely.33 While courtship in taverns was common, in the form of eating and drinking together, the actual formal contracting of marriage was no less common – guests and witnesses were specially gathered together in a public space. Those contracting marriage in a tavern were not seeking to escape the patriarchal authority of the household, but were more likely simply to have lacked a suitable space of their own. At no point in the testimonies did women try to claim that they had not been drinking in a tavern, suggesting there was nothing disreputable about it, although it would still have been more common for women to visit only in the company of men.34 There was no cultural objection to such a venue: ‘In a world in which the sacred was immanent, medieval people saw nothing unusual about undertaking a sacrament “before God” in a space that we might regard as obviously profane’.35 The defining factor in the choice of an appropriate venue for an exchange of wedding contracts was accessibility: propriety depended upon visibility. Thus, a tavern, like the hall of a prosperous household or a church, was a social centre, full of people, and was thus an eminently suitable location for the exchange of a contract because of the ready supply of witnesses.

Marriages were far from the only contracts routinely drawn up in the tavern or inn. In market towns and smaller cities drinking establishments could invariably be found near marketplaces and inns themselves were often the site of economic exchange, both legitimate and underhand.36 It was also common for larger provincial inns to act as forerunners of county halls from the later sixteenth century, playing host to courts and administrative meetings.37 Nor was Chaucer’s parish clerk doing something unusual in using the tavern as venue for his charters of land:

Wel koude he laten blood, and clippe ans shave,

And maken a charter of lond or acquitaunce

. . .

In al the toun nas brewhous ne tavern

That he ne visited with his solas,

Ther any gaylard tappestere was.38

The wide range of business activities routinely carried out in inns and taverns often led to conflict; and the role of a successful taverner or innkeeper entailed a large part of mediation – not least as they were legally required to act as paterfamilias for those (and their property) under their roof.39 The language used to describe Chaucer’s innkeeper Harry Bailly is evocative of statutes and ordinances; and Martha Carlin has proposed that contemporary audiences would have identified the host in the Canterbury Tales with ‘the Southwark MP and innkeeper of the same name’.40 Hanawalt concluded that the successful innkeeper, just like Chaucer’s Harry Bailly, required ‘a ready wit heightened by some education, sharp eyes, a physical appearance and strength adequate to overcome resistance, and a certain presence and seeming gentility of manner’.41 Alan Everitt also highlighted the importance of early modern innkeepers’ roles as proto-bankers, retaining cash and administering credit on behalf of regular patrons.42

London’s inns and taverns simultaneously stood comparison with those of provincial English towns, but were quite distinct in other ways. While many inns could be found in the central marketplaces of the city, such as Cheapside, there was a much stronger tendency for inns to be located near, or even outside, the gates, as land values forced the space-hungry inns out from the centre from as early as the fourteenth century.43 In terms of their physical form, though, medieval London taverns and inns were more similar to their provincial counterparts. While there was a tradition of taverns and social drinking spaces occupying cellars, as has remained common in the Germanic world, in London the main drinking spaces of taverns and inns tended to concentrate on the ground floor. When Ralph Treswell surveyed three small taverns in 1610, all had their drinking rooms on the ground floor.44 The physical form of inns most obviously varied from taverns in terms of the provision of stabling facilities and accommodation, increasingly in the form of private rooms, on upper floors.45 The inn that we take as our case study, the Star on Bridge Street, provides an example of an inn serving the travelling public but emerges most clearly as a social space for the local community.

The Star Inn

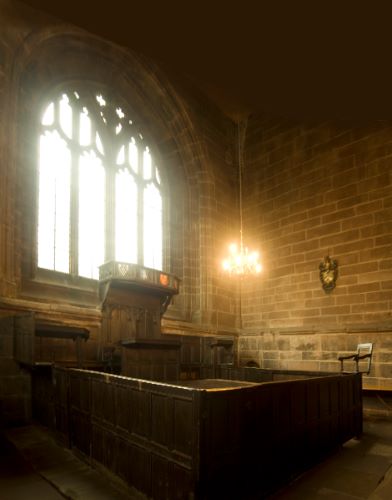

The inn known as ‘le Sterre’ was a large tenement in the north of the parish of St. Margaret Bridge Street, just a few moments’ walk from London Bridge. It spanned the whole area between Bridge Street to the west and Pudding Lane to the east, and from the cemetery of St. Margaret’s to the south to the parish boundary to the north. The Star is exceptionally well documented because it passed into the ownership of the Fishmongers’ Company in 1505 and a complete collection of original deeds survive in the Fishmongers’ collection at the Guildhall library.46 This tenement was one of numerous drinking establishments along Bridge Street which also included the Kings Head, the Bell and the Castle on the Hoop in the parish of St. Magnus; and the Hotelar, formerly known as the Brodegate; and the Sun on the Hoop in St. Margaret Bridge Street.47 Tenements known as ‘on the hoop’ tended to be alehouses, their title apparently originating in the adoption of a metal hoop, as used in beer barrels, as a frame for their sign, whereas taverns and inns had no particular theme to their names.48

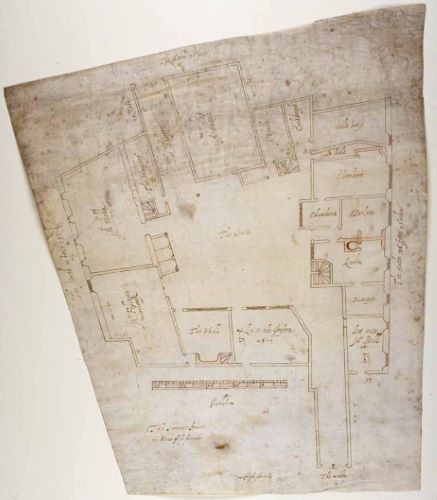

The fact that the Star formed part of the institutional property portfolio of the Fishmongers’ Company has meant that not only the fifteenth-century deeds survive, but also detailed surveys. Unusually, plans for the Star exist in both pre- and post-Great Fire forms. The first plan, catalogued by the London Metropolitan Archives as dating from c.1700, has been identified by Dorian Gerhold as having a much earlier date (see Figure 2.1).49 This plan depicts one room in the south-west corner of the inn as let to a John Ball, ironmonger. He had leased the shop to the south of the inn gateway that abutted this room in 1617 and hired the room in question before 1639, but had left by 1645, establishing the dating of the plan.50 The plan was evidently drawn up in connection with the request of the lessee, William Molins, to rebuild the east (Pudding Lane) side of the inn when the Company required him to provide a ‘draughte’ of his plans. This plan shows a complex layout of uses and sub-tenancies. Beyond Ball’s second room or shop, the southern range included the kitchen and buttery, two chambers and stores for both wood and coal. Stables were found at the east side, one of them reaching all the way to Pudding Lane, but mainly separated by a fifteen-foot gap occupied by separate shops. Next to the eastern gateway a room with a spiral staircase was referred to as ‘the Hoastrey’, while the main hall, with large fireplace and elaborate windows, was directly opposite. Another well-lit room was let to the Grocers’ Company and a warehouse in the north-western corner was let to one Mr. Fellton. Molins requested to rebuild in order to provide small chambers upstairs ‘for want thereof looseth many guests’, suggesting that the original medieval form of the inn with communal accommodation had survived until this point.51

The second plan is part of the Fishmongers’ Company plan book, still kept at Fishmongers’ hall and securely dated to 1686. The passageway from Pudding Lane had been re-aligned to give a continuous line of five shops, noted as having been rebuilt by the lessee of the inn, to the north of the passageway. To the west, the shop facing Fish Street Hill to the south of the main gateway was now included as part of the plan.52 The area around the central yard was dominated by a large stable to the north and a smaller one to the east, with stairs alongside leading up to the main accommodation areas of the inn, spread over two extra storeys on all sides, including a substantial projection over the yard and offering no fewer than thirty-three chambers.53 The southern range included another shop in what had been Ball’s room, a kitchen and buttery and a parlour and a chamber in what had been the wood and coal stores. The grandest parlour, with a large fireplace, and the tap-house were on the west range within the yard. The Star’s central location was more constrained than that of most other London inns, but its lessees clearly did their best to maintain the facilities that were expected of a metropolitan inn, catering to both travellers and Londoners.

The Whaplodes, the Fishmongers, and the Star Inn

While the earliest extant visual depictions of the inn are firmly seventeenth century, it was nonetheless thoroughly documented in earlier periods. The chronology of the ownership of the tenement, revealed through the virtually unbroken sequence of deeds, quitclaims, leases, indentures, receipts and acknowledgements, is, as such documents generally are, complex and detailed, particularly on legal ownership. There were at least nineteen transactions in the century from 1403 to 1505, with four of these having occurred within the same year (1498). The longest period of stable tenure of the property, thirty-two years, occurred between 1456 and 1488, perhaps representing the lowest point in the ‘slump’ of the fifteenth-century economy.54 The Star’s fifteenth-century history began with the death of Walter Doget, a fishmonger, in 1403 and its sale by his son and executor, John, to a consortium of local merchants. At this time it was occupied by a brewer, Robert Forneux.55 At some point before 1425 this group sold the tenement on to another group of locals, including the rector of St. Margaret’s, Henry Shelford. At this point the Star first entered the hands of Robert Whaplode, a hosteller and one of this consortium of 1425, who presumably occupied it and traded there.56 Following Whaplode’s death in the 1430s, his co-investors conducted a series of leases and grants of rents upon the property before selling it to a further consortium, comprising chaplains, clerks, country gentlemen, and even a royal justice, in 1442.57 These transactions, involving many parties as both grantors and grantees, are particularly ambiguous, potentially representing either a genuinely collaborative investment purchase, or a kind of mortgage. London does not seem to have seen the same kind of official mortgage often seen in the cities of the Low Countries, which were often backed by religious houses. Instead it appears to have been routine for lenders to have been listed among the grantees in a transaction and then gradually recording quitclaims until a single owner was left.58 Several patterns emerge from the late medieval history of the Star and its owners which neatly illustrate some wider trends in London’s late medieval property market and patterns of tenure. For example, while occupation of a tenement by a single householder might remain stable for many years, this had little relation to the ownership of that property, which could change much more frequently. Furthermore, while a single household may have occupied and used a property, ownership seldom rested with any one individual, or even with family or company-related groups of individuals.

The Star was leased to another group of fishmongers in 1488 which included William Whaplode, son of Robert, the hosteller who had been an owner from 1425.59 In 1498 the remnant of the 1442 owners, Edmund Watton, a gentleman from Addington in Kent, sold the tenement to a further group comprising William Palley, a stockfishmonger, and several gentlemen from Kent for the considerable sum of 230 marks. One of the Kent gentlemen, all seemingly connected with the village of East Peckham, was Sir Alexander Culpepper, participant in the October 1483 rising against Richard III, who served as sheriff of Kent in 1500 and 1507 and was the father of Thomas Culpepper, gentleman of the privy chamber who was executed as the supposed lover of Queen Katherine Howard.60 Such gentry investment in the urban land market was surprisingly common in this period and provides an interesting counterpoint to the typical narrative of London wealth being exported to the shires as mercantile dynasties ‘come of age’ as gentry families. After numerous intermediate quitclaims and grants, the Kent gentlemen Richard Broke, Reginald Pekham and Alexander Culpepper sold the Star to the Fishmongers’ Company, in the form of its twelve feoffees, in 1505. Among the feoffees was none other than William Whaplode, who was still tenant under the terms of the lease of 1488; and although he was free of the Fishmongers’ Company, the Star was undoubtedly in use as an inn.61 It is therefore interesting to observe the well-documented tendency for successful and aspirational members of minor companies to ‘trade up’ when apprenticing their children. Here, within the immediate social world, the dominant local company was chosen but, in practice, traditional family business interests prevailed.

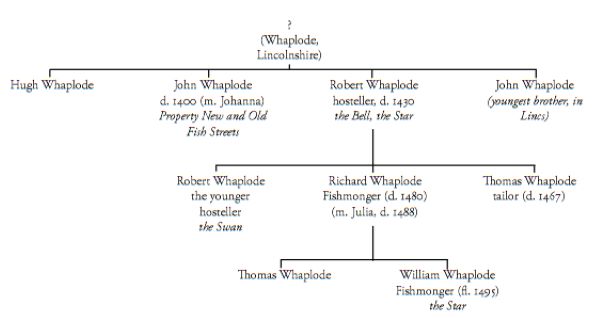

The connections between the Fishmongers’ Company and the Whaplode family are particularly illuminating as to how personal and institutional networks intersected in the late medieval city. Brothers John and Robert Whaplode, from the village of that name near Spalding in Lincolnshire, arrived in London in the closing decades of the fourteenth century. Undoubtedly exploiting his east coast connections, John became a successful fishmonger and owned lands in the parishes of St. Margaret Bridge Street and in St. Nicholas Cole Abbey in what would later be known as New and Old Fish Street respectively. John died in 1400 and appears to have been childless; at least some of his property found its way to his brother, Robert, who was a hosteller in the parish of St. Margaret. Robert was indicted in the wardmote inquests of 1421 for ‘selling their ale within their hostels in hanaps [cups], and not in sealed measures according to the mayor’s proclamation’, as hosteller at the Bell and in 1423 both there and at the Star.62 His son, also Robert, was hosteller at the Swan at this time. All three taverns were located in Bridge Street, the venue of London’s main fish market. The elder Robert, while a hosteller, counted prominent local fishmongers among his associates, including Thomas Dursle and William Downe, to each of whom he left a money rent from his properties.63 Robert Whaplode apprenticed his oldest son, Richard, to a fishmonger, undoubtedly making use both of family connections and those he had built up by acting as host at an inn which was inevitably patronized by members of Fishmongers’ Company. Richard’s son William then continued the precedent set by his father, becoming a Fishmonger.

Far from being simply another tavern, the Star appears to have had a particular place in the history of the Fishmongers’ Company. Like most other victualling trades in medieval London, the markets for fish were situated on eastern and western hills of the city. This meant that for many fishmongers their day-to-day life was concentrated upon one market or the other and contacts between each branch were limited to the defence of their corporate liberties through the court of halimote.64 The division between the Fishmongers of New and Old Fish Streets ran so deep that civic proclamations were explicitly addressed to ‘the Masters of the Fishmongers of the one Street and the other’.65 Individual Fishmongers were equally aware of the distinction and their bequests to their brethren were phrased to make it very clear that they did not intend their generosity to extend to fishmongers of the other market. John Snoryng of St. Nicholas Cole Abbey, for example, bequeathed some silverware to the ‘brotherhood and fraternity of the Fellowship of Fishmongers in Old Fishstreet of London’ in 1490.66 Intensely local, market-based identity was clearly important in the lives of the Company and it is tempting to conclude that the Star might have functioned as the de facto hall for the Fishmongers’ Company in Bridge Street by the time it was leased to the trustees of the Company in 1488, before the establishment of the current hall in Stockfishmonger Row following the consolidation of the companies under ordinances drawn up in 1508.67 Priscilla Metcalf, historian of the Fishmongers’ halls, has suggested that this connection may have originated with a separate ‘regulars’ table’, or Stammtisch, in the tavern.68 The prime location in the midst of the fish market and the family connection of the Whaplodes certainly meant that the Star was integral to the life of the market and its users in the Fishmongers’ Company and beyond.

Robert Whaplode and Local Networks

The place of the inn and its proprietors in the social world of Bridge Street, its market and its dominant company becomes even clearer when we look at evidence for other forms of social interaction. Witnessing was integral to the verification of exchanges and the documents that recorded them in the pre-modern world, but also played a wider social role in cementing local relationships. Acting as a witness was, in the words of Craig Muldrew, ‘a casual, and normal, part of daily activity, and was one of the duties of neighbourliness’.69 While it might seem a rather abstract or impersonal act, Christine Carpenter has not been alone in arguing that the position of responsibility invoked through witnessing, together with glimpses of the contexts in which such documents were drawn up, makes their value as a marker of a social relationship clear.70 The witnessing of deeds relating to properties within the parish of St. Margaret Bridge Street during the first half of the fifteenth century (when enrolment in the court of husting was more prevalent) gives a detailed picture of relationships in property transactions. The vast majority of witnesses, and especially the most prolific, were members of the Fishmongers’ Company, which is an expected reflection of the social and economic characteristics of the neighbourhood.71

However, conspicuous among the Fishmonger witnesses was one member of a minor trade who in fact witnessed more local deeds than any other person: none other than Robert Whaplode, hosteller and tenant of the Star inn on Bridge Street. Whaplode’s prominence in the local deeds as a witness represented his role as landlord: it is indicative of the kinds of local social networks, just as found by the Clarks in their study of early modern Canterbury.72 It seems likely that, as Chaucer described, the physical process of validating written exchanges often took place within the hostelry and the innkeeper was called upon as a witness. The combination of the location of the inn and the intensely local nature of the Fishmongers’ Company in the earlier fifteenth century combined to create a special place for this hosteller which was perpetuated and even intensified over the course of the following century. Despite acting as churchwarden of St. Margaret’s in 1404,73 Robert Whaplode never attained civic office, but was clearly prosperous when considered in a local context: viewed from the street up, rather than the civic government down, he was certainly significant. If the Star was anywhere near as large and complex a business as it was in the plans of the seventeenth century, it would certainly have been a significant business to run.

The nature of medieval record-keeping ensures that the Londoners we know most about are those with great status and wealth or those who attracted the attention of the courts; and this has understandably led historians to focus upon the extremes of urban society: those in civic government or those constituting the ‘underclass’. While the records of the middling sort of late medieval London society might be sparse, this case study has shown how it is possible to examine their lives in a broader sense. Innkeepers, like the lower-status merchants and moderately prosperous artisans that appear to have formed their social milieu, frequently crossed paths with the ‘merchant class’, mayors and aldermen, but also possessed their own rich social lives and connections throughout the city. Taverns and inns provide a lens through which to view the range of social activities, from guild meetings to witnessing deeds, which middling-status late medieval Londoners conducted within their neighbourhoods. While it might not be possible to build a full biography of Robert Whaplode, a moderately prosperous but far from notable victualler, by examining the inn through which he and his family built a connection with their local community and local economy, a light has been cast into this stratum of late medieval London society, who might not be the ‘small people’ but certainly have been neglected.

Endnotes

- C. M. Barron, ‘Searching for the “small people” of medieval London’, Local Historian, xxxviii (2008), 83–94. See also F. Rexroth, Deviance and Power in Late Medieval London (Cambridge, 2007); R. M. Wunderli, London Church Courts and Society on the Eve of the Reformation (Cambridge, Mass., 1981).

- S. L. Thrupp, The Merchant Class of Medieval London, 1300–1500 (Chicago, Ill., 1948), pp. 1–52; see also, e.g., A. F. Sutton, ‘Nicholas Alwyn, mayor of London: a man of two loyalties, London and Spalding’ in this volume.

- Barron, ‘Searching for the “small people”’, pp. 83–8.

- Discussions of the archaeological remains and extant fabric of medieval inns are, by contrast with social and cultural studies, quite numerous. For a still-useful general survey of inn buildings in medieval England, see W. A. Pantin, ‘Medieval inns’, in Studies in Building History: Essays in Recognition of the Work of B. H. St. J. O’Neil, ed. E. M. Jope (London, 1961), pp. 166–91; for London, Ralph Treswell’s surveys provide valuable evidence of pre-Great Fire inns: The London Surveys of Ralph Treswell, ed. J. Schofield (London Topographical Soc., cxxxv, London, 1987).

- P. Clark, The English Alehouse: a Social History (London, 1983), pp. 5–15. John Hare noted that while ‘not everyone would have agreed on the borderline cases’ between inns and alehouses, medieval sources did try to distinguish the different types of establishment (J. Hare, ‘Inns, innkeepers and the society of later medieval England, 1350–1600’, Jour. Med. Hist., xxxix (2013), 477–97, at p. 480).

- M. Carlin, ‘“What say you to a piece of beef and mustard?”: the evolution of public dining in medieval and Tudor London’, Huntington Libr. Quart., lxxi (2008), 199–217, at p. 210.

- R. Mazo Karras, Common Women: Prostitution and Sexuality in Medieval England (Oxford, 1996), p. 72.

- J. M. Bennett, Ale, Beer and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300–1600 (Oxford, 1996), pp. 123–44.

- B. Hanawalt, Of Good and Ill Repute: Gender and Social Control in Medieval England (Oxford, 1998), p. 105.

- M. Hailwood, Alehouses and Good Fellowship in Early Modern England (Woodbridge, 2014), pp. 171–2.

- Hare, ‘Inns’, p. 481; B. Kümin, ‘Public houses and their patrons in early modern Europe’, in The World of the Tavern: Public Houses in Early Modern Europe, ed. B. Kümin and B. A. Tlusty (Aldershot, 2002), pp. 44–62, at p. 47.

- Kümin, ‘Public houses’, p. 50.

- C. M. Barron, London in the Later Middle Ages (Oxford, 2004), p. 59.

- Kümin, ‘Public Houses’, pp. 55–6; Hare cited the New Inn at Gloucester, which had its own tennis court (‘Inns’, p. 481). The Pastons stayed at the George at St. Paul’s wharf, where the innkeeper Thomas Green and his wife were trusted enough by the family to receive and forward messages and parcels for them (Barron, London, p. 59).

- The Colloquies of Erasmus, ed. N. Bailey (2 vols., London, 1878), i. 286–93.

- Hailwood, Alehouses, p. 56; P. Withington, The Politics of Commonwealth: Citizens and Freemen in Early Modern England (Cambridge Social and Cultural Histories, iv, Cambridge, 2005), pp. 127–37.

- Hailwood, Alehouses, pp. 55–7.

- The Gull’s Hornbook by Thomas Dekker, ed. R. B. McKerrow (New York, 1971), p. 69.

- Hailwood, Alehouses, pp. 180–1.

- Clark, English Alehouse, p. 13.

- M. O’Callaghan, ‘Tavern societies, the inns of court, and the culture of conviviality in early seventeenth-century London’, in A Pleasing Sinne: Drink and Conviviality in Seventeenth-Century England, ed. A. Smyth (Studies in Renaissance Literature, xiv, Cambridge, 2004), pp. 37–51, at p. 39.

- A. F. Sutton, ‘The “Tumbling Bear” and its patrons: a venue for the London Puy and mercery’, in London and Europe in the Later Middle Ages, ed. J. Boffey and P. King (London, 1996), pp. 85–110, at pp. 85–95.

- Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Tanner 221, fo. 35v; E. A. New, ‘The cult of the Holy Name of Jesus in late medieval England, with special reference to the fraternity in St. Paul’s cathedral, London’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 1999), pp. 230, 390. The Jesus Guild also owned a tavern, the Bull’s Head in St. Martin’s Lane, which they sold in 1507 with the explicit intention of acquiring a guildhall, although this never happened (MS. Tanner 221, fo. 14; New, ‘Cult of the Holy Name’, pp. 205–6).

- F or a useful historicization of the pilgrims and insightful discussions of Chaucer himself and of Harry Bailly, innkeeper of the Tabard, see M. Carlin, ‘The Host’, in Historians on Chaucer: the ‘General Prologue’ to the Canterbury Tales, ed. S. Rigby (Oxford, 2014), pp. 460–80.

- The Famous Victories of Henry the Fifth: Containing the Honourable Battell of Agincourt: As it was Plaide by the Queenes Maiesties Players (London, 1598) (STC 13072).

- N. Levine, Practicing the City: Early Modern London on Stage (New York, 2016), p. 26; A Survey of London by John Stow, ed. C. L. Kingsford (2 vols., Oxford, 1908), i. 216–7.

- W. Shakespeare, Henry IV Part 2, ed. by S. Greenblatt et al., in The Norton Shakespeare (New York, 1997), II. i. 79–81; Levine, Practicing the City, p. 42.

- Levine, Practicing the City, p. 33.

- Hanawalt, Of Good and Ill Repute, pp. 106–9.

- L. Gowing, ‘“The freedom of the streets”: women and social space, 1560–1640’, in Londinopolis: Essays in the Cultural and Social History of Early Modern London, ed. by P. Griffiths and M. S. R. Jenner (Manchester and New York, 2000), pp. 130–53, at p. 145.

- Gowing, ‘“Freedom of the Streets”’, pp. 133–4.

- Gowing, ‘“Freedom of the Streets”’, pp. 139–45.

- S. McSheffrey, Marriage, Sex, and Civic Culture in Late Medieval London (Philadelphia, Pa., 2006), pp. 129–30.

- McSheffrey, Marriage, Sex, and Civic Culture, pp. 133–4.

- Hanawalt, Of Good and Ill Repute, p. 105; S. McSheffrey, ‘Place, space, and situation: public and private in the making of marriage in late-medieval London’, Speculum, lxxix (2004), 960–90, esp. at pp. 973, 983–5.

- Hare, ‘Inns’, pp. 481–2. Hare noted that buying and selling within inns and taverns was forbidden in many places but could be part of regulated exchange, as in Exeter, where legitimate cloth sales occurred in the Eagle and the New inns.

- A. Everitt, ‘The English urban inn 1560–1760’, in Perspectives in English Urban History, ed. A. Everitt (London, 1973), pp. 91–137, at pp. 109–10.

- G. Chaucer, ‘The clerk’s prologue and tale’, in The Canterbury Tales, ed. L. D. Benson (3rd edn., Oxford, 1988), pp. 68–77, at p. 70, ll. 3326–36.

- Hanawalt, Of Good and Ill Repute, pp. 13–5.

- Carlin, ‘The Host’, p. 472.

- Hanawalt, Of Good and Ill Repute, p. 117.

- Everitt, ‘English urban inn’, pp. 109–10.

- C. Barron noted that in ‘Southwark and Westminster by 1400 inns were ubiquitous’ (Barron, London, p. 59).

- Schofield, London Surveys, p. 15 and nos. 43, 50, 51.

- J. Schofield, Medieval London Houses (London, 1995), p. 54; Hare, ‘Inns’, p. 481; Schofield, London Surveys, p. 15 and nos. 3 and 4. C. Barron observed that while ‘providing bed and breakfast … was an important part of the innholder’s job, the stabling and feeding of horses were probably even more important’ (Barron, London, p. 59).

- LMA, Fishmongers’ Company Deeds, CLC/L/FE/G/179/MS06696.

- CPMR 1413–1437, pp. 139–40, 158–9.

- M. Ball, The Worshipful Company of Brewers: a Short History (London, 1977), p. 63.

- LMA, CLC/L/FE/H/003.

- D. Gerhold, London Plotted: Plans of London Buildings c.1450–1720, ed. S. O’Connell, London Topographical Soc., clxxviii (London, 2016), p. 173.

- Gerhold, London Plotted, pp. 173–4.

- Gerhold, London Plotted, p. 175.

- Gerhold, London Plotted, p. 175.

- D. Keene, The Walbrook Study: a Summary Report: Social and Economic Study of Medieval London (London, 1987), pp. 19–20.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/131 (45).

- LMA, CLC/L/FE/G/179/MS06696, folder 1, item 16.

- The grantees were Henry Fane, gentleman, of Hadlowe in Kent; Alexander Colepepper, esquire; Reginald Pekham, esquire; William Palley, stockfishmonger; and Thomas Reynold of Hadlew, yeoman (LMA, CLC/L/FE/G/179/MS06696, folder 2, item 6).

- This appears to have been a covert way of arranging a mortgage and is also discussed in J. L. Bolton, ‘Was there a “crisis of credit” in fifteenth-century England?’, Brit. Numismatic Jour., lxxxi (2011), 144–64, at p. 156. London and other English cities did not see the widespread use of formal and explicit mortgages, which were common in many continental cities (C. Van Bochove, H. Deneweth and J. Zuijderduijn, ‘Real estate and mortgage finance in England and the Low Countries, 1300–1800’, Continuity and Change, xxx (2015), 9–38.

- LMA, CLC/L/FE/G/179/MS06696, folder 1, item 13.

- LMA, CLC/L/FE/G/179/MS06696, folder 2, item 6; P. Fleming, ‘Culpeper family (per. c.1400–c.1540)’, in ODNB <https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/52784> [accessed 28 Apr. 2009].

- LMA, CLC/L/FE/G/179/MS06696, folder 1, item 1.

- CPMR 1413–1437, pp. 139, 158.

- LMA, CLA/023/DW/01/159 (13).

- F or a more detailed discussion, see J. Colson, ‘London’s Forgotten Company? Fishmongers, their trade and their networks in later medieval London’, in The Medieval Merchant: Proceedings of the 2012 Harlaxton Symposium, ed. C. M. Barron and A. F. Sutton, Harlaxton Medieval Studies, n.s., xxiv (Donington, 2014), pp. 20–40.

- LMA, COL/CC/01/01/01, journal of the common council, i, fo. 51v.

- TNA, PROB11/8, fos. 207v–2078v.

- F or details of the merger of the companies, see J. N. Colson, ‘Negotiating merchant identities: London companies merging and dividing, c.1450–1550’, in Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton, ed. M. Allen and M. Davies (London, 2016), pp. 2–20, at pp. 9–10.

- P . Metcalf, The Halls of the Fishmongers’ Company: an Architectural History of a Riverside Site (Chichester, 1973), p. 12.

- C. Muldrew, ‘The culture of reconciliation: community and the settlement of economic disputes in early modern England’, Hist. Jour., xxxix (1996), 915–42, at pp. 926–7.

- C. Carpenter, ‘Gentry and community in medieval England’, Jour. Brit. Stud., xxxiii (1994), 340–80, at pp. 368–9.

- This is based upon an analysis of all deeds registered in the hustings court between 1400 and 1450 relating to the parish of St. Margaret Bridge Street. They are discussed further in J. Colson, ‘Local communities in fifteenth century London: craft, parish and neighbourhood’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 2011), pp. 279–89.

- P . Clark and J. Clark, ‘The social economy of the Canterbury suburbs: the evidence of the census of 1563’, in Studies in Modern Kentish History: Presented to Felix Hull and Elizabeth Melling, ed. N. A. Y. Detsicas (Maidstone, 1983), pp. 65–86.

- The only reference to Whaplode’s role as a churchwarden is a passing reference in a will proved in the commissary court (LMA, DL/C/B/004/MS09171/2, fo. 47v)

Chapter 2 (37-54) from Medieval Londoners: Essays to Mark the Eightieth Birthday of Caroline M. Barron, edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer (University of London Press, 10.31.2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.