Demons appear regularly as causes of mental disorder in saints’ lives and miracle stories.

By Dr. Catherine Rider

Associate Professor in Medieval History

University of Exeter

Introduction

Among the mentally disordered people who came to the shrine of Thomas Becket in Canterbury in the 1170s was an unnamed woman who had been possessed by a demon for eight years. While many of the possessed people who came to the shrine are described as violent, this woman’s demon acted rather differently: it caused her to speak Latin and German.1 These strange symptoms were not the norm in the Becket miracles, but they were not unique either. Many other saints’ lives and canonization processes contain similar stories of demoniacs who spoke foreign languages which they had not known before or displayed other special skills such as the ability to answer difficult scientific questions, predict the future or reveal other people’s sins.2 Indeed, a diagnosis of possession may have been especially likely in these cases, because it was hard to explain how else someone could acquire knowledge which they had never had the opportunity to learn. The knowledge must belong instead to the demon which possessed them.

Demons appear regularly as causes of mental disorder in saints’ lives and miracle stories but they were far from the only explanation available to medieval hagiographers. Early medieval and Byzantine saints’ lives attributed mental disorder to many different factors including epilepsy, demons, drunkenness, and simply “madness,”3 and Sari Katajala-Peltomaa’s chapter in this volume shows that the same was true of late medieval miracle narratives. It was not always easy to distinguish between these different forms of mental disorder. The “possessed” and “insane” people who came to saints’ shrines are sometimes described as behaving in very similar ways, with shouting and violence, and some observers found it difficult to distinguish between the two.4 Nevertheless, demonic possession was a distinct kind of mental disorder because of its non-physical cause and also in some cases because of its unusual symptoms such as the ones described in the Becket miracle. Possession has also often been treated as a distinct form of mental disorder by historians. Although surveys of madness and other forms of mental disorder in the Middle Ages do mention possession,5 most recent work on the subject has instead been done by historians of medieval religious culture. Their primary focus has been not on attitudes to mental disorder but on the ways in which clergy tried to distinguish between divine inspiration and demonic possession when faced with visionaries, especially women, who behaved oddly.6

A few of these studies have noted that medieval medicine and scientific writing provided an alternative set of conceptual tools with which to think about demons’ role in causing mental disorder. In particular Nancy Caciola has shown how thirteenth-century theologians such as Thomas Aquinas believed demons could provoke visions and hallucinations by interfering with the senses or balance of humours in the body.7 Renate Mikolajczyk has studied another thirteenth-century writer who made similar points, the Silesian scholar Witelo, whose treatise on demons discussed the role of both demons and physical problems in causing hallucinations.8 Nevertheless, despite these exceptions the ways in which medieval medicine conceptualised possession as a medical condition, rather than (or as well as) a spiritual one have received comparatively little attention.

One important reason for this is that late medieval medicine itself focused primarily on the natural causes of mental problems rather than on demons. As Timo Joutsivuo’s chapter in this volume shows, educated medieval physicians drew on ancient Greek and Arabic medical theory which emphasized that most mental disturbances were caused by imbalances of the humours. These imbalances might in turn be caused by a variety of physical and environmental factors including illness, poor diet, or emotional problems. Studies of mental disorder which draw on these medical texts therefore follow their sources in focusing primarily on humoral medicine. The chapter on medieval medicine in Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl’s Saturn and Melancholy, for example, argues that medieval physicians usually rejected demonic explanations for melancholy and devotes most of its space to outlining their views of melancholy’s humoral causes.9 The chapters on medieval medicine in Stanley W. Jackson’s history of melancholia and depression and Muriel Laharie’s history of madness in the Middle Ages likewise focus on humoral explanations, and Michael Dols’ study of madness in medieval Islamic society takes a similar approach to the Arabic medical texts although Laharie and Dols both note that medical writers might occasionally mention demons.10 The same approach can be seen in the much smaller historiography of epilepsy, another disorder which was occasionally associated with demonic possession in medieval miracle narratives. Thus the major history of epilepsy by Owsei Temkin notes that the condition became increasingly associated with possession during the Middle Ages but in his chapter on medieval medicine, Temkin focuses instead on humoral explanations for epilepsy.11

These studies are right to stress the importance of humoral explanations for mental disorder in medieval medicine but they do not tell the whole story. From the thirteenth century onwards a significant number of late medieval medical writers also discussed the possibility that demons might be involved in certain kinds of mental disorder. This information is found in late medieval treatises on practical medicine which go under the title of “practica.” These works were linked to the part of the university curriculum which focused on the diagnosis and treatment of illnesses rather than on medical theory. They came in a variety of formats but the focus of this essay will be on the large compendia or encyclopaedias which set out the causes and treatment of illnesses, starting with the head and working downwards. These “practica” works were written from the thirteenth century onwards by educated physicians and were primarily written for university students, but they also circulated more widely among educated medical practitioners. Because they were written in Latin, the language of university education, the same texts could be read by educated medical practitioners across Europe.12 These compendia therefore form a coherent body of writing on illness and by examining a range of works written between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries we can identify the continuities and changes in educated physicians’ understandings of demons and mental disorder across the late Middle Ages.

The compendia copied material from one another and also drew on earlier Arabic medical works which were translated into Latin in the late eleventh and twelfth centuries. Sometimes they simply organised and summarised this material without adding much new information, as did the voluminous Medical Sermons by the Florentine physician and medical writer Niccolo Falcucci (d. 1412). However, many authors reflected on what their predecessors had said and added new information based on their reading and sometimes their own observation.13 Danielle Jacquart has argued that fifteenth-century writers were especially willing to talk about their own experiences and, as we will see, this is true for their writing on mental disorder.14

Like other ancient and medieval medical treatises, medical compendia never presented demons as the main cause of mental disorder and devoted far more space to humoral causes, but they mentioned demons regularly when they discussed three conditions: mania, melancholia and epilepsy. All three were categorised as diseases of the head which disrupted the usual relationship between the mind and the body. Mania and melancholia were very broad categories and their symptoms ranged from mild to severe mental disorder, which could be temporary or permanent. Mania was caused by an excess of yellow bile in the brain and its symptoms included agitation and excitement, while melancholia was caused by an excess of corrupted black bile in the brain which led to sadness, fear and delusions.15 The boundaries between these two conditions were not always fixed, however, and several ancient and medieval medical writers discussed mania as a form of melancholia, or vice versa, rather than as a separate condition.16 Epilepsy had a more restricted range of symptoms but could stem from the same humoral causes: for example the tenth-century Arabic medical writer Ishāq ibn Imrān, whose treatise on melancholia was translated into Latin in the late eleventh century by the monk and prolific translator Constantine the African, noted that some epileptics were also melancholic.17 Demons were also sometimes mentioned as causes of other conditions, such as incubus, a sleep disorder in which a person feels that something is pressing down on them, which has been studied by Maaike van der Lugt.18 However, incubus did not produce symptoms which fitted so neatly with ideas about demonic possession, since the demon was believed to remain outside the body.

The authors of these compendia approached the relationship between demons and mania, melancholia and epilepsy in very diverse ways. Some dismissed the idea that demons caused these forms of mental disorder, saying that only ignorant people believed this. If mentally disordered people claimed to be threatened by demons, they argued, then this was simply a delusion. In many cases, however, medical writers offered more complex assessments. A few com-pendia presented demons as a cause of melancholia, mania or epilepsy which needed to be diagnosed and treated like any other. Others discussed whether physical causes could produce the symptoms which were usually attributed to demonic possession, including the ability to prophesy. All these positions had their roots in Arabic medical texts and in many cases they were ultimately derived from ancient Greek medicine, but as late medieval medical writers read and discussed these earlier works, they responded to them in a variety of ways which reflected their own concerns. Over the centuries they also came to take the relationship between demons and mental disorder more seriously, so that by the fifteenth century two physicians were giving the matter far more detailed and sophisticated consideration than earlier writers had.

This essay traces these late medieval medical approaches to the role of demons in affecting a person’s mental wellbeing. First it will look at the earlier medical texts which provided the basis for late medieval ideas about demonic mental disorder. Most of these were written in Arabic by physicians based in the Middle East and Muslim Spain, but they also drew heavily on ancient and late antique Greek medical writers such as Rufus of Ephesus, a physician writing in the second century ad. Next the ideas of Latin medical writers active between the thirteenth and the fifteenth centuries will be addressed. The essay will look at some of the ways in which physicians sought to dismiss the belief that demons caused mental disorder by claiming that visions of demons were hallucinations and that only ignorant people took them literally. Finally, it will turn to the strange, apparently demonic symptoms displayed by certain mentally disordered people, such as the ability to prophesy. How did late medieval physicians account for these, and how willing were they to concede that demons might be involved in these cases?

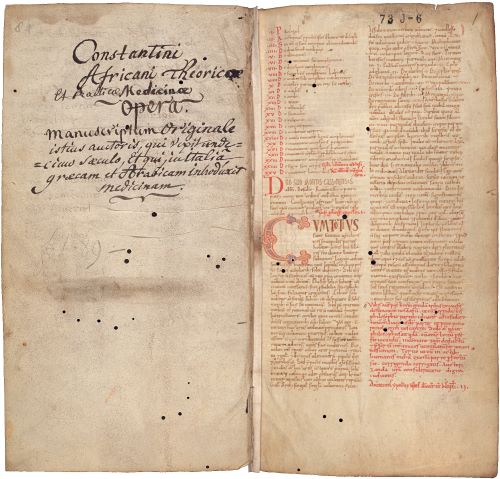

Demons and Mental Disorder in Arabic Medicine

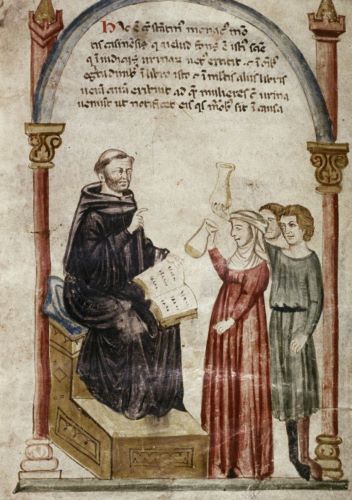

The Arabic medical texts on which late medieval European physicians drew did not always mention demons as a possible cause of mental disorder. For example, Ishāq ibn Imrān discussed only humoral causes for melancholia although he did note that “the common people” said epileptics were possessed by demons.19 However, several Arabic texts which were translated into Latin and widely read by later physicians did mention the subject. The first to be translated was the Pantegni of Constantine the African, which was a translation of an earlier medical encyclopaedia by the Persian physician Alī ibn al-Abbās al-Mağūsī, known in the Latin west as Haly Abbas (d. 994). In his chapter on epilepsy, Constantine mentioned demons as one possible cause. He included a series of tests to be used “when it is doubted, that is, whether [an epileptic person] is lunaticus [affected by the moon] or epileptic or demoniac.” Among these tests was one which, Constantine said, was “much proved by experience.”

Say this name in the ear of the patient or person you suspect: ‘Go back, demon, because the effymoloy order it.’ If he is a lunaticus or demoniac, he will immediately become like a dead man for one hour. When he rises, ask him about whatever thing you want and he will tell you. And if this does not happen when he hears this name, you will know he is epileptic.20

This was followed by a cure which could be used on demoniacs, epileptics and lunatici alike:

Whichever one of these above-mentioned conditions he suffers from, let him be treated with this most holy medicine. Indeed if he has a father and mother they should take him to church on the Ember Days21 and he should hear the mass on Friday. He should do the same on Saturday. When Sunday comes, a priest or monk should write out the gospel passage where it is said, “This kind is not expelled except by prayer and fasting.” (Matt. 17:21) He will be freed, whether he is epileptic or lunaticus or demoniac.22

The origins of these passages are obscure. As the use of Christian ritual and the Bible suggests, they are not found in al-Mağūsī’s Arabic original. In fact, the chapter on epilepsy falls in a part of the Pantegni which is not translated from al-Mağūsī’s text and seems to have been put together either by Constantine the African himself, or by another compiler working in the late eleventh or twelfth century.23 Whatever their origin, these passages described demons as one possible cause of epilepsy and distinguished them from other causes. They also offered a clear way of telling these different kinds of epilepsy apart: the person who was epileptic because of the moon or demons would respond differently to the verbal formula and would answer questions when an ordinary epileptic would not. The fact that these questions could be on “whatever thing you want” may be a nod to be the belief that possessed people had special knowledge or prophetic powers. The distinction between demonic and non-demonic epilepsy was not absolute, however. The moon could produce the same symptoms as demons; and moreover, after distinguishing between the three conditions, Constantine immediately conflated them again by recommending the same ritual cure for all three.

The Pantegni was not widely read in medieval universities after the twelfth century24 but these passages were quoted by medical compendia into the late Middle Ages, for example by the Montpellier professor of medicine Bernard de Gordon in the early fourteenth century and later by Niccolo Falcucci, who quoted them from Bernard.25 Another early fourteenth-century physician, John of Gaddesden, noted that the cure was especially suitable for children and other epileptics who could not take conventional medicines. He also claimed to have personal experience of using it: “I have found it to be true whether [the sick person] is a demoniac or lunaticus or epileptic.”26 This passage from the Pantegni therefore kept open the possibility that demons might cause epilepsy but it remained a small part of later writing on the condition.

Another discussion of demons and epilepsy is found in the second book of a large medical and surgical compendium by al-Zahrawi, a physician and surgeon active in Muslim Spain in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries, who was known in the Latin west as Abulqasim, Alsharavius or Albucasis. This part of al-Zahrawi’s compendium was translated into Latin in the mid thirteenth century.27 In it, al-Zahrawi listed five types of epilepsy. Four were caused by humoral imbalances but in the fifth kind of epilepsy the sufferer’s humoral balance was not disturbed. In this case the epilepsy was “caused by some out-side agent whose mode [of action] is not known, and it is said that it is caused by demons.”28 Al-Zahrawi also claimed to have seen cases himself in which epileptics spoke foreign languages and displayed scientific knowledge which they had never learned. In these cases, he said, if the physician’s own remedies failed the cure should be left to God.29 Like Constantine the African, he took demons seriously as a cause of epilepsy even though his emphasis remained on the humoral causes. However, he distinguished demons more clearly from the other causes of epilepsy than Constantine did, with his emphasis on the strange knowledge displayed by demoniacs and his suggestion that conventional cures might not work.

Neither the Pantegni nor al-Zahrawi mentioned demons as a possible cause of mania or melancholia but another, more influential Arabic medical work did. The Canon of Medicine by the physician and philosopher Avicenna (ibn Sīnā, d. 1037) was translated into Latin in the twelfth century and was widely read and commented on in universities from the thirteenth century onwards.30 In his chapter on melancholia, Avicenna referred briefly to the belief that demons could cause this condition:

And it has seemed to some physicians that melancholia happens by a demon, but we do not care if it happens by a demon or not because we teach medicine. Further, we say if it does happen by a demon it is enough for us that it has changed the [sick person’s] complexion to black bile, and the black bile is its immediate cause; then the cause of that black bile is a demon or not a demon.31

Avicenna, then, was willing to accept that demons might cause melancholia but unlike Constantine the African or al-Zahrawi he dismissed this as irrelevant for physicians. His view was quoted by many later Latin writers including Bernard de Gordon, Niccolo Falcucci and a fifteenth-century Italian physician, Giovanni Matteo Ferrari da Grado.32

These Arabic writers laid the foundations for a view of mental disorder which recognized demons as one possible explanation but did not place much emphasis on them. For Avicenna, the distinction between demonic melancholia and the non-demonic variety was irrelevant because demons worked through physical causes. The Pantegni did not go this far but it implied the symptoms might be similar, since a special test was needed to diagnose demonic epilepsy. For both these writers demonic and non-demonic mental disorders could be treated in the same way, by treating the immediate humoral causes (for Avicenna) or by prayer and religious ritual (for Constantine the African). In some respects this view probably corresponds with more widespread medieval views of mental disorder: as Alain Boureau and Laura Ackerman Smoller have noted, “possessed” and “insane” people are sometimes described as behaving in similar ways.33 For al-Zahrawi, by contrast, demonic and humoral epilepsy were far more distinct in both their symptoms and their treatment. All these views can be found in later medieval Latin medical texts, but Latin writers also expanded on them, either to dismiss demons as marginal to a medical understanding of mental disorder, or to explain in more detail how they might affect the mind.

“Wrong” Beliefs about Mental Disorder: Delusions, Metaphors, and Ignorance

One strand of late medieval medical writing did not present demonic mental disorder as a serious possibility but instead argued against people who wrongly attributed melancholia, mania or epilepsy to demons. One way in which physicians did this was by presenting demons not as a cause of mania or melancholia, but as a symptom. To do so they built on a long history of medical writing which set out the delusions experienced by melancholics.34 For example Ishāq ibn Imrān’s De Melancholia, translated by Constantine the African, stated that some melancholics saw “before their eyes terrible and frightening black shapes and similar things.”35

In a Christian context these black shapes were easily linked with demons and also, ironically, with black-clad Benedictine monks. Thus Gilbertus Anglicus, writing in around 1250, elaborated on Ishāq ibn Imrān’s comment to say that melancholics “see before their eyes terrible and frightening and black shapes such as monks, black men killing them, [and] demons.”36 In the early fourteenth century John of Gaddesden again claimed to have had personal experience of a phenomenon noted in much older written sources. He said he had treated a melancholic woman who was afraid to speak about the devil or look out of the window in case she saw him, and who feared that any man wearing black might be the devil.37 Some medical writers were still quoting similar ideas into the fifteenth century: for example in the 1440s the Italian physician Michele Savonarola noted that melancholics had “terrifying dreams, such as a vision of demons, black monks and other things of this sort.”38 For these physicians, demons were simply hallucinations brought on by the illness.

Another way of dismissing the role of demons in causing mental disorder was to argue that only ignorant people who did not understand the true causes of these mental conditions believed demons were really involved in them. Again this had a long history in medical writing. As we have seen, Ishāq ibn Imrān stated that it was “the common people” who thought epileptics were demoniacs and the same idea also appeared regularly in medical writing about incubus, as Maaike van der Lugt has shown.39 Late medieval medical writers usually made this point when they discussed forms of mania and melancholia which made their victims aggressive, and which went under various names including wolf or dog mania, wolf demon, demonic melancholia or simply demoniaca. Many physicians insisted that these names were metaphors used to describe the behaviour of the sufferers rather than evidence that demons were present. Thus a medical compendium by the thirteenth-century surgeon Guglielmo da Saliceto said that dog mania was “commonly” called demoniaca because of the “wickedness of its symptoms.”40 The fifteenth-century physician and medical writer Antonio Guaineri, who taught in the universities of Pavia and Cheri in northern Italy and then became physician to the duke of Savoy, likewise explained that “wolf demon” was so-called because “the patient has the ferocity of a wolf inside him, because he quarrels, hits, bites and per-forms other wolf-like acts.” However, he complained that the uneducated took the name literally: “the common people say this person has a wolf demon inside them, and especially the ignorant pizocharii.”41

When they discussed these “wrong” beliefs about demons and mental disorder, these late medieval medical writers sought to dismiss, or at least de-emphasize, the idea that demons were truly involved in these cases. To do so they built on ideas which had a long history in learned medical writing, but they went further than their Greek or Arabic sources in using these ideas to attack what they claimed were erroneous beliefs relating to demons and mental disorder.

Demons and the Strange Abilities of the Mentally Disordered

Nevertheless, it was not always satisfactory to argue that only ignorant people believed demons could cause mental disorder, especially since the New Testament made it clear that demons could possess people. Late medieval physicians confronted the difficulties surrounding demonic possession especially when they discussed cases in which melancholics and epileptics seemed to predict the future or displayed knowledge which they could not have acquired by normal means. Older views of these symptoms varied. A few earlier medical writers had accepted these gifts as genuine. For example in the second century ad, Rufus of Ephesus noted that melancholics had the gift of prophecy42 and as we have seen, al-Zahrawi linked epileptics’ prophecies to demons. However, many late antique and Byzantine medical writers were more cautious, noting that melancholics only thought they were prophets.43 In the Pantegni Constantine the African followed their approach, saying that certain melancholics “act as diviners and think they predict divine things.”44 This phrasing, with its emphasis on what the melancholics themselves thought, left open the possibility that the prophecy was simply a delusion, especially as Constantine included it in a list of other delusions suffered by melancholics and did not mention demons as a possible alternative explanation.

Late medieval medical texts preserved this spectrum of views. One strand of medical writing followed Constantine the African in noting that mentally disordered people only appeared to prophesy. Thus Gilbertus Anglicus noted that maniacs “seemed” to prophesy but did not pronounce on the truth of this himself: one derivation for the term mania, he said, was “from the hands of the gods of the netherworld [manibus diis infernalibus], for demons seem to speak within them and foretell hidden things.”45 Bernard de Gordon implied more strongly that these were not real prophecies. “It seems to other [melancholics],” he said, “that they are prophets and that they are inspired by the Holy Spirit, and they begin to prophesy and predict many future things, either about the state of the world or the Antichrist.”46 Like Constantine the African, he placed this at the end of a discussion of the various delusions experienced by melancholics, strongly implying that the prophecies, too, were delusions.

A second strand of medical writing went further and linked these cases of prophecy to specific physical conditions rather than to demons. One of the earliest writers to do this was Guglielmo da Saliceto, who in the thirteenth century described prophecy as a symptom of “dog mania” or demoniaca and connected it to menstrual problems. Humoral medicine regarded menstruation as an important way of purging a woman’s excess humours, so failure to menstruate (except during pregnancy) was believed to cause a wide variety of health problems. For Guglielmo these problems included certain kinds of mental disorder:

Moreover it may happen in women, according to many people, from the retention of purifying menses in the veins of the womb, from which fumes rise, disturbing the imagination [in medieval philosophical writing, the part of the brain which retains forms received by the senses] and the cogitative faculty [which combines and separates these sensory forms] to things which have been seen before, whether they are known [to the patient] or not. And they cause the patient to speak of future things, and even cause him [eum] to speak various languages, and what is more [speak] learnedly even if he has never heard letters. It happens also from sperm which is retained in the womb, which after corrupting and a long space of time is converted into poison, from which a poisonous fume rises. It influences the brain, the imagination, the cogitative faculty and the estimation [which perceives intentions and forms judgements] in many ways, so that it may induce the patient to the same motions which retained menses induce, as has been said above. And according to many people this happens to widows and members of religious orders and virgins who are ready for sexual intercourse, when the time for inter-course has passed.47

Guglielmo seems to have been the first medieval Latin writer to link the special abilities of mentally disordered people to a specific physical condition in this way. Interestingly, this was not a condition of the head but of the womb, which illustrates how far mind and body were linked in medieval medical theory. By linking prophecy and special abilities to the womb, Guglielmo also made these abilities specific to women, although there is some confusion here since he used the masculine pronoun eum (which can refer to men and women, or men alone) to describe the afflicted person. Gilbertus Anglicus, writing a little earlier, had linked mania to menstrual retention in women or the retention of corrupt sperm in men (without mentioning prophecy) and so it is possible that the early modern printed version of Guglielmo’s text is inaccurate here and that the second part of the passage was intended to relate to men.48 It is also possible that Guglielmo’s emphasis on women reflects the view, often found in religious writing on female visionaries, that women were more susceptible to spiritual influences, both positive and negative, than men were.49 Not all late medieval physicians linked prophecy so closely to the female body, however, and as we will see, Antonio Guaineri claimed to have seen a melancholic man with special abilities.

Guglielmo da Saliceto did not specifically exclude demons from provoking the prophecies and abilities of these women, but his detailed description of a physical cause could be taken to imply this. This was certainly how a later Italian physician, Niccolo Bertucci (d. 1347), interpreted his comments. After paraphrasing the passage from Guglielmo quoted above, Bertucci elaborated on the symptoms caused by poisonous fumes and some of the ways in which observers interpreted them:

And these things happen to certain people all the time and to certain people periodically, according to how the matter takes its course in the body, and then it is believed to be from demons, which afflict bodies at sacred times. Although according to truth and faith this is possible, more often, however, it happens from the matter described above, which is why it happens more to women than men, and [more] to widows than married women, and [more] to members of religious orders than secu-lars, and [more] to poor people who work a great deal in the sun and use garlic, mustard [and] onions than to the rich who use good foods and have the necessary funds for medicines and remedies. This would not happen if it always happened by a demon since a demon is not susceptible to a natural cure, nor does it distinguish between such persons.50

Guglielmo da Saliceto’s physical explanation therefore helped Niccolo Bertucci to argue against the likelihood of real demonic involvement in cases of mental disorder. These two men went further than earlier writers in linking prophecies to specific physical problems but their explanations did not answer every question about melancholics’ and maniacs’ special abilities. They did not make clear exactly why these particular physical conditions led people to prophesy, or whether their prophecies were genuine.

In the fifteenth century two medical writers attempted to answer these questions, seeking to fit prophecy into a broader understanding of how the body and mind worked. One was Antonio Guaineri, whom we have already met criticizing popular beliefs about “wolf mania.” His comments on melancholia offer an unusual, and unusually detailed, view of the special abilities of mentally disordered people. Instead of offering a few remarks in the context of a much longer chapter, Guaineri devoted a substantial sub-section of his chapter on melancholy to the question, “Why certain uneducated melancholics have become educated and how, too, some of these people predict future things.”51 He started by describing a case he had seen himself: “I saw a certain melancholic peasant in Pinerolo [northern Italy] who would always compose songs when the moon was burnt [combusta, perhaps referring to a new moon or eclipses], and when the burning was over by about two days he never offered any educated word until the next burning. And they told me this man had never learned letters.”52

Guaineri did not suggest that demons were the explanation for this and nor did he link these abilities to the womb or the balance of the humours. Instead his explanation lay in the relationship between body and soul: cut off from the senses, the soul could perceive the future. To argue this point, Guaineri cited three ancient Greek philosophical and astrological texts: Aristotle’s Metaphysics, Plato’s Timaeus and the Quadripartitum (or Tetrabiblos) of the Greek astronomer Ptolemy. Drawing on these works he built up an argument that all human souls were created perfect, and at their creation already possessed all the knowledge which they could ever acquire. The astrological conjunction at the moment when the soul was infused into a person’s body also gave the soul certain additional properties. Once the soul was placed inside a body, the body impeded it from accessing this innate or astrologically-infused knowledge but, Guaineri argued, if the senses were temporarily put out of action (for example by melancholy) the soul could once again access this information.53 Guaineri offered a similar explanation for the marvellous abilities of some epileptics. In epilepsy, again, the senses were impeded and so the soul was able to perceive the future. “Therefore, carried away by the paroxysm, they very often predict many future things, and so the common people who do not know the cause think this happens by the power of demons.”54

In these passages Guaineri offered an explanation for melancholics’ and epileptics’ special abilities which did not require them to be caused by demons; in fact, as with “wolf mania,” only “the common people” thought demons were present in these cases. Individually none of these ideas was new. Guaineri was not the first medical writer to offer a physical explanation for the special abilities of mentally disordered people or to dismiss what “the common people” thought. His ideas about the soul in particular were drawn from ancient Greek works which had been available in Latin since the twelfth century or earlier.55 What was new was the way in which he put this material together to answer this particular question in far more detail than earlier physicians.56 In doing so he constructed a view of mental disorder which accepted that certain melancholics and epileptics could predict the future and set out exactly how this worked without recourse to demons.

Another fifteenth-century medical writer who discussed the strange abilities of melancholics and epileptics in detail took a different view. Giovanni Matteo Ferrari da Grado (d. 1472) taught, like Guaineri, at the university of Pavia and was also associated with the court of Milan.57 In several respects his approach to the problem was similar to Guaineri’s. He too discussed both the physical and demonic aspects of prophecy at length and supplemented his reading of earlier texts with his own observation, but his sources and conclusions were different. Ferrari da Grado was more willing than Guaineri to admit that demons might give melancholics and epileptics special knowledge, and he drew his information not primarily from Greek philosophers and astrologers, as Guaineri did, but from Arabic medical writers, most notably al-Zahrawi.

In his chapter on epilepsy, Ferrari da Grado quoted al-Zahrawi’s description of a fifth kind of epilepsy in which the sufferer’s humoral balance did not change. Still quoting al-Zahrawi mentioned three possible causes of this: “from a bad regime of food and drink, and from sins and transgressions, and the final cause is from cursed demons who are called alabin.”58 By reproducing these explanations without criticism Ferrari da Grado implied that demons really did cause some epileptics to display special abilities. He raised the issue again in his chapter on melancholia and went into more detail. In a long discussion of the possible causes of melancholia, he first reproduced Avicenna’s view that if demons caused melancholia at all, they did so through manipulating the balance of humours in a person’s body. Then against this he cited the tenth-century Persian physician ar-Razi (known in the Latin west as Rhazes), who had argued that it was possible for melancholia to occur without a humoral change in the body, and the passage from al-Zahrawi which linked this to demons.59

In conclusion Ferrari sided with ar-Razi and al-Zahrawi against Avicenna, to argue that certain forms of melancholia were not caused by humoral imbalances, but he did not mention demons explicitly at this point. Instead the example he cited was from ar-Razi, of a person who made themselves melancholic by thinking too long or too hard about a topic.60 In this way he left space for demons to cause mental disorder but did not give them prominence. Later on in the chapter, however, Ferrari did mention a different way in which demons might cause mental disorder: they could incite people to bad habits which might, in their turn, cause melancholia.61

Ferrari da Grado followed al-Zahrawi more closely when he discussed possible cures for epilepsy and melancholia. He agreed with al-Zahrawi that if epilepsy was not caused by an imbalance of the humours, then physical cures might not work and in that case, the afflicted person should trust in God.62 In his discussion of cures for melancholia he again quoted al-Zahrawi but this time he added his own observation, making the Muslim author’s com-ments relevant to a Christian context: “This is also clear from experience, for we have seen some people vexed by demons who were apparently suddenly and immediately restored to health by the divine office through the hands of holy monks,” an instantaneous recovery which would not have been possible if they were suffering from humoral imbalances.63 Unlike Antonio Guaineri and most earlier physicians in the Latin tradition, then, Giovanni Matteo Ferrari da Grado presented demonic mental disorder as a possibility that physicians should take into account, which was not connected with the balance of the humours and so might require different treatment.

Neither Ferrari da Grado nor Antonio Guaineri rejected the idea that humoral factors caused mental disorder, but they were more willing than earlier medical writers to give demons serious consideration in cases which medical theory found difficult to explain. In the end they came to different conclusions: Ferrari was willing to accept the action of demons in some cases, while Guaineri preferred physical explanations even for strange symptoms. This diversity of opinion was not unusual. Danielle Jacquart has argued that fifteenth-century medical writers offered widely different assessments of many issues, despite their use of the same pool of learned authorities.64

Indeed, another fifteenth-century physician took a more extreme position based on similar evidence. Jacques Despars, a French physician whose work has been studied by Jacquart, was highly dismissive of demonic explanations for mental disorder and criticized theologians for encouraging sufferers to believe they were possessed and seek religious remedies instead of medical ones.65 Nevertheless, despite these significant differences, there were certain fundamental similarities between these physicians’ approaches. Ferrari, Guaineri and Despars all sought to integrate demons into a medical discussion of mental disorder in greater detail than had earlier writers, and all three also cited their own observation as well as earlier authorities to back up their views. It is therefore likely that this new interest in demonic mental disorder and special knowledge reflects the wider tendency among fifteenth-century medical writers to record their own experience, which Jacquart has noted.66 It may also correspond to a growing interest in “occult” diseases and treatments which could not be explained with reference to the theory of the humours, which Nancy Siraisi has argued is visible in the later fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.67

These physicians’ interest in demons, prophecy and mental disorder prob-ably also reflects broader religious and intellectual changes. In the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, prophets who claimed to predict the future through divine inspiration had become increasingly prominent and influential. Historians have often linked this to the Great Schism, arguing that the collapse of official authority at the top of the church allowed unofficial prophets, some of them women, to attract attention. Prompted by their observation of these prophets, several late fourteenth- and early fifteenth-century theologians wrote treatises on the discernment of spirits: the task of working out whether the spirit which inspired someone was divine or demonic.68 These inspired prophets may similarly have encouraged physicians to take an interest in the special powers of melancholics and epileptics and in the wider area of demonic possession: at least one later fifteenth-century physician, Antonio Benivieni, claimed that possession was a new epidemic in his own time.69 However, the medical writers were not interested in the same problems as the theologians. Instead of debating whether these prophets were inspired by good or evil spirits, physicians debated whether melancholics and epileptics who predicted the future or spoke foreign languages were inspired by a spirit at all, or whether there was a physical explanation for their actions.

The greater interest in demonic mental disorder shown by these fifteenth-century physicians may also be connected to a third factor: a change in attitudes to the demonic which can be seen in the earliest witch trials. It was in the first half of the fifteenth century that the first witch trials took place in parts of Switzerland and the adjacent regions of France and Northern Italy. In contrast to earlier trials for magic, these trials emphasized the importance of a close relationship between the witch and the devil, which was to become a key feature of early modern witch trials. Antonio Guaineri was particularly well placed to know about these because he was based in Savoy, a region which saw early witch trials, and he claimed to have seen cases of bewitchment in Pinerolo.70 Conversely, Jacques Despars’ skepticism about cases of supposed demonic possession may have been a reaction against these same concerns: Jacquart has argued that he may have formed his views by arguing against a fellow canon of the church of Notre-Dame at Tournai, the theologian Gilles Carlier, who wrote several treatises on exorcism.71 A greater interest in demonic activity, prophecy and mental disorder in a variety of intellectual circles is therefore likely to have persuaded these fifteenth-century physicians to take the issue more seriously and explore it in more depth than earlier writers had, even if they came to different conclusions.

Conclusions

Demons were never the primary explanation for mental disorder in late medieval medicine. Many medical writers did not mention them at all and those who did only did so after discussing the humoral causes of melancholia, mania and epilepsy at length. Before the fifteenth century a significant number of medical writers played down the importance of demons in causing mental disorder, and also refused to commit themselves as to whether epileptics and melancholics might really have special abilities. Although they did not dis-miss these possibilities altogether, they tended to present demons as hallucinations, metaphors to describe the symptoms of an illness, or an explanation offered by the ignorant; and they discussed melancholics’ and epileptics’ special abilities as delusions or symptoms of a physical condition. This conservative approach persisted into the fifteenth century, when Michele Savonarola discussed demons in traditional terms, as a delusion experienced by melancholics.

However, alongside this skepticism another strand of medieval medicine was more willing to accept that demons might cause certain forms of melancholy and epilepsy and sometimes (but not always) linked to this, that melancholics and epileptics might have genuine powers to predict the future. This can already be seen in the Pantegni and in the fifteenth century the matter attracted greater interest from Antonio Guaineri and Giovanni Matteo Ferrari da Grado, among others. These writers drew on earlier Greek and Arabic medi-cal writers who presented demons as one possible cause of mental disorder, but they were also influenced by more contemporary beliefs, especially in the fifteenth century.

These late medieval medical texts therefore shed light on how physicians thought about the ways in which mental wellbeing could be affected by external forces. In many texts, demons are depicted as working alongside natural forces to such an extent that the two were often difficult to separate: causing mental disorder by upsetting the balance of the humours in a person’s body, for example. This closeness between demons and physical causes meant that many apparently demonic symptoms were susceptible to physical explanations. Late medieval physicians drew these ideas from earlier medical writers like Constantine the African and Avicenna but they may have found them persuasive because they corresponded to a more general late medieval understanding of how demons interacted with the physical world. The idea that demons were part of the physical world and acted through physical causes was found in medieval theology72 and it may also have reflected more widespread beliefs: as Sari Katajala-Peltomaa points out, the witnesses in canonization processes sometimes described demons acting in very physical ways. This was not the only view available to late medieval physicians, however. Less prominent, but still present, was the view derived from the work of al-Zahrawi, that demons affected mental order in ways which were radically different from physical causes, and which required different remedies.

The same issues continued to be debated in later centuries, as rising numbers of witch trials encouraged more medical writers to write about demonic illnesses. In these debates the same strands of interpretation which are visible in medieval medical writing continued to surface. Thus many early modern physicians focused on the physical causes of mental disorder and denounced ignorant people who attributed it to possession or witchcraft, while others explained visions of witches or devils as delusions caused by black bile. Others again were more willing to accept demons as a cause of mental disorder and argued that the symptoms of possessed people could not be explained by physical causes.73 All these ideas had roots in the medieval past.

Late medieval physicians did not reach a consensus about these issues, any more than early modern ones did. Indeed, the range of opinions which they offered deserves further study. A larger sample of fifteenth-century writers, in particular, would shed light on how far other physicians were similarly interested in demons, prophecy and mental disorder. It would also be useful to explore whether there were variations between different geographical areas: for example, did physicians who were based in places which saw early witch trials show more interest in demonic mental disorder? Guaineri’s links with the duchy of Savoy and his mention of cases of magic in Pinerolo are suggestive here. Nevertheless, the physicians studied here help to illustrate the variety of views of mental disorder which existed simultaneously in medieval culture. Medical views of this condition were shaped by earlier texts which described a range of possible causes, and well-read physicians could choose from a variety of competing ideas about mental disorder. The behaviour of mentally disordered people or, at least, stereotypes about how they might behave (with violence, fits or prophecies) also suggested explanations to both the educated and the uneducated. Popular beliefs about mental illness offered other views again. Medieval physicians responded to these factors in many different ways which reflected their own reading, observation and ideas about what was possible.

Endnotes

- James Craigie Robertson, ed., Materials for the History of Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury, 7 vols (London: Longman, 1875–1885), 2.519.

- Nancy Caciola, Discerning Spirits: Divine and Demonic Possession in the Middle Ages (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2003), 48–49.

- Bernard Bachrach and Jerome Kroll, “Sin and Mental Illness in the Middle Ages,” Psychological Medicine 14 (1984): 511; Peregrine Horden, “Responses to Possession and Insanity in the Earlier Byzantine World,” Social History of Medicine 6 (1993): 186.

- Alain Boureau, Satan the Heretic: the Birth of Demonology in the Medieval West, trans. Teresa Lavender Fagan (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2006), 124; Laura Ackerman Smoller, “A Case of Demonic Possession in Fifteenth-Century Brittany: Perrin Hervé and the Nascent Cult of Vincent Ferrer,” in Voices from the Bench: the Narratives of Lesser Folk in Medieval Trials, ed. Michael Goodich (New York: Palgrave McMillan, 2006), 162–166.

- Muriel Laharie, La folie au Moyen Âge: XIe–XIIIe siècles (Paris: Le Léopard d’Or, 1991), 23–51; Stanley W. Jackson, Melancholia and Depression from Hippocratic Times to Modern Times (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 325–341.

- For a recent overview see Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, “The Strange Case of Ermine de Reims (c. 1347–1396): a Medieval Woman between Demons and Saints,” Speculum 85 (2010): 321–326. See also Boureau, Satan the Heretic; Caciola, Discerning Spirits; Dyan Elliott, Proving Woman: Female Spirituality and Inquisitional Culture in the Later Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004), part III.

- Caciola, Discerning Spirits, 213–214.

- Renate Mikolajczyk, “Non Sunt Nisi Phantasiae et Imaginationes: A Medieval Attempt at Explaining Demons,” in Communicating with the Spirits, ed. Gábor Klaniczay and Eva Pócs (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2005), 40–51.

- Raymond Klibansky, Erwin Panofsky and Fritz Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy: Studies in the History of Natural Philosophy, Religion and Art (London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, 1964), ch. II. Rejection of demonic explanations: 93–94.

- Jackson, Melancholia, 46–64; Laharie, Folie, 117–144; Michael W. Dols, Majnūn: the Madman in Medieval Islamic Society, ed. Diana E. Immisch (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992), ch. 4.

- Owsei Temkin, The Falling Sickness: A History of Epilepsy from the Greeks to the Beginnings of Modern Neurology, 2nd ed. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971), 86, 118–133.

- Jole Agrimi and Chiara Crisciani, Edocere Medicos: Medicina scolastica nei secoli XIII–XV (Naples: Istituto Italiano per gli Studi Filosofici, 1988), 158–160.

- Agrimi and Crisciani, Edocere Medicos, 177; Chiara Crisciani, “History, Novelty and Progress in Scholastic Medicine,” Osiris, 2nd ser. 6 (1990): 129–130.

- Danielle Jacquart, “Theory, Everyday Practice and Three Fifteenth-Century Physicians,” Osiris, 2nd ser. 6 (1990): 140.

- Jackson, Melancholia, 250.

- Jackson, Melancholia, 250–254; Laharie, Folie, 134.

- Ishāq ibn Imrān, Maqāla Fī L-Mālīhūliyā (Abhandlung über die Melancholie) und Constantini Africani Libri Duo de Melancholia, ed. Karl Garbers (Hamburg: Helmut Buske, 1977), 131.

- Maaike van der Lugt, “The Incubus in Scholastic Debate: Medicine, Theology and Popular Belief,” in Religion and Medicine in the Middle Ages, ed. Peter Biller and Joseph Ziegler (Woodbridge: York Medieval Press, 2001), 175–200.

- Ishāq ibn Imrān, Maqāla, 132.

- “In hoc loco dicendum est unde dubitatur, scilicet utrum lunaticus uel epilepticus uel demoniacus sit…Est et aliud expertissimum. Dic hoc nomen in aure patientis uel sus-pecti: Recede demon, quia effymoloy precipiunt. Si lunaticus sit uel demoniacus, statim efficitur uelud mortuus per horam i. Eo surgente, interroga eum de quacunque re uolueris et tibi dicet. Et si non acciderit audito hoc nomine, scias epilepticum esse.” Constantinus Africanus, Pantegni, Practica, 5.17, London, British Library MS Sloane 2946, fol. 44r. The 1515 printed edition words this passage slightly differently: Isaac Israeli, Opera Omnia (Lyons, 1515) fol. 99r. I have not been able to trace the term effymoloy.

- The Ember Days were four fast days observed four times a year.

- “Quodcunque supradictorum patiatur, hoc medicamine sanctissimo medicetur. Si uero patrem habeat et matrem, ducant ipsum ad ecclesiam in die iiii. temporum, et audiat missam in vi. feria. Similiter in die sabbati faciat. Die dominica ueniente, sacerdos uel religiosus uir scribat euangelium ubi dicitur, ‘Hoc genus non eicitur nisi oratione et ieiunio.’ Siue epilepticus siue lunaticus uel demoniacus sit, liberabitur.” Ibid, fol. 44r; see also Isaac Israeli, Opera, fol. 99r.

- Monica Green, “The Re-Creation of Pantegni, Practica, Book VIII,” in Constantine the African and Ali ibn al-Abbas al-Magusi: the Pantegni and Related Texts, ed. Charles Burnett and Danielle Jacquart (Leiden: Brill, 1994), 121–124.

- Danielle Jacquart and Françoise Micheau, La médecine arabe et l’occident médiéval (Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose, 1990), 174.

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium Medicinae (Lyons, 1559), 2.24, pp. 226–227; Niccolo Falcucci, Sermones Medicales (Venice, 1491), 3.5.13, fol. 86r.

- “Et quia multi pueri et alii qui non possunt uti medicinis vexantur epilepsia, fiat experimentum quod ponit Constantinus 5o practice sue, capitulo de epilepsia…Et ego inueni illud verum siue sit demoniacus siue lunaticus siue epilepticus.” John of Gaddesden, Rosa Anglica (Venice, 1502), 2.11, fol. 62v. Method of diagnosis: fol. 61r.

- See the introduction to his better known surgical treatise: Albucasis, On Surgery and Instruments: A Definitive Edition of the Arabic Text with English Translation and Commentary, ed. M.S. Spink and G.L. Lewis (London: Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, 1973), viii.

- Alsharavius, Liber Theoricae necnon Practicae (Augsburg, 1519), ch. 34, fol. 33v; trans. Temkin, Falling Sickness, 106.

- Alsharavius, Liber Theoricae, fol. 33v; Temkin, Falling Sickness, 106.

- Nancy Siraisi, Avicenna in Renaissance Italy: The Canon and Medical Teaching in Italian Universities after 1500 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987), 44–46, 50–53.

- “Et quibusdam medicorum visum est quod melancolia contingat a demonio, sed nos non curamus cum physicam docemus, si illud contingat a demonio aut non contingat. Postquam dicimus quoniam si contingat a demonio sufficit nobis ut conuertat complex-ionem ad coleram nigram, et fit causa eius propinqua colera nigra. Deinde fit causa illius colere nigre demonium aut non demonium.” Avicenna, Liber Canonis (Lyons, 1522) 3.1.4.19, fol. 150r. See also Dols, Majnūn, 81.

- Bernard de Gordon, Lilium Medicinae, 2.19, 204; Falcucci, Sermones, 3.5.7, fol. 71r; on Ferrari da Grado see below, n. 59.

- See above, n. 4.

- Dols, Majnūn, 28; Klibansky, Panofsky and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy, 50.

- “Vident enim ante oculos formas terribiles et timorosas nigras et similia.” Ishāq ibn Imrān, Maqāla, 120.

- “Vident enim ante oculos formas terribiles et timorosas et nigras sicut monachos, homines nigros illos occidentes, demones.” Gilbertus Anglicus, Compendium Medicinae (Lyons, 1510), fol. 103r.

- “sicut de una muliere quam habui in cura mea. Vidi quod non audebat loqui de diabolo nec respicere per fenestram exteriorem [my emendation: edition reads ‘extra’] ne videret diabolum, timens de omni homine nigris vestito ne esset ille.” John of Gaddesden, Rosa Anglica, 4.2, fol. 132r.

- “Somnia terribilia ut est visio demonum, monachorum nigrorum et aliorum huiusmodi.” Joannes Michael Savonarola, Practica Maior (Venice, 1497), 6.1.11, fol. 61v. On Savonarola see Jacquart, “Theory,” 141.

- van der Lugt, “Incubus,” 176, 195–197.

- “Vocatur communiter passio ista demoniaca propter pravitatem accidentium.” Guilelmus de Saliceto, Summa Conservationis et Curationis (Venice, 1489), ch. 21. On Guglielmo see Nancy Siraisi, “How to Write a Latin Book on Surgery: Organising Principles and Authorial Devices in Guglielmo da Saliceto and Dino del Garbo,” in Practical Medicine from Salerno to the Black Death, ed. Luis García-Ballester, Roger French, Jon Arrizabalaga and Andrew Cunningham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 92.

- “Patiens enim lupi ferocitatem in se habet, quia rixatur, verberat, mordet et alios lupinos actus exercet. Et hunc vulgares demonium lupinum in se habere aiunt, et maxime igno-rantes pizocharii.” Antonius Guainerius, Practica (Lyons, 1524), 1.15.1, fol. 40v. On Guaineri see Jacquart, “Theory,” 141. I have not been able to translate pizocharii.

- Klibansky, Panofsky and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy, 50; Jackson, Melancholia, 327.

- Klibansky, Panofsky and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy, 54.

- “Alii diuinant et se de diuinis predicere putant.” Constantine the African, Pantegni, Theorica 9.7, in Isaac Israeli, Opera, fol. 42r.

- “A manibus diis infernalibus. Videntur enim in eis demones loqui et vaticinari abscondita.” Gilbertus Anglicus, Compendium Medicinae, fol. 102v.

- “Aliis videtur quod sint prophete, et quod sint inspirati a spiritu sancto, et incipiunt prophetare et multa futura predicere, siue de statu mundi aut antichristi.” Bernard de Gordon, Lilium Medicinae, 2.19, 205.

- “Fiat autem in mulieribus ut plurimum ex retentione menstruorum mundantium in venis matricis ex quibus eleuantur fumi mouentes imaginationem et cogitationem ad ea que visa fuerint in preterito siue fuerint notata siue non et inducunt pacientem ad narrandum de futuris: et etiam inducunt eum ad loquendum variis linguis, et quod plus est litteraliter etiam si nunquam litteras audiuerit. Fit etiam ex spermate retentio in matrice quod conu-ersum est post corruptionem et temporis longitudinem in venenum, a quo fumus [my emendation; text reads ‘fuimus’] venenosus eleuatur. Mouet diuersimode cerebrum, imaginationem, cogitationem et extimationem, ita quod inducat patientem ad motiones easdem ad quas menstrua retenta inducunt, ut superius dictum est. Et hoc ut plurimum contingit viduis et religiosis et virginibus habilibus ad coitum cum tempus coeundi transierit.” Guilelmus de Saliceto, Summa Conservationis, ch. 21. For definitions of imaginatio, cogitatioand estimatio see Dag Nikolaus Hasse, “The Soul’s Faculties,” in The Cambridge History of Medieval Philosophy, ed. Robert Pasnau (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 309.

- Gilbertus Anglicus, Compendium Medicinae, fol. 103r.

- Caciola, Discerning Spirits, 19.

- “Et fiunt haec quibusdam hominibus omni tempore, et quibusdam periodice, prout mate-ria cursum in corpore suscipit; et tunc creditur esse a daemonibus, qui affligunt corpora tempore sacro. Quod licet secundum veritatem et fidem sit possibile, saepius tamen fit a materia praedicta, quare magis accidit mulieribus quam viris, et viduis quam nubentibus, et monachis quam secularibus, et pauperibus in sole multum laborantibus utentibus allio, sinape, cepe quam diuitibus bonis cibis utentibus, et necessaria pro medicinis et remediis habentibus. Quae non fierent, si semper a daemonio fierent, cum daemonium curam naturalem non recipiat, neque distinctionem talium personarum.” Niccolo Bertucci, Compendium Medicinae (Cologne, 1537), 1.1.7, fol. 31r.

- “Quare illiterati quidam melancolici litterati facti sunt et qualiter etiam ex his aliqui futura predicunt.” Guaineri, Practica, 1.15.4, fol. 42v.

- “Ego Pinaroli quemdam rusticum melancolicum vidi qui semper luna existente combusta carmina componebat, et transacta combustione circa duos dies usque ad aliam combus-tionem, verbum nunquam ullum litteraliter proferebat. Et hunc mihi nunquam didicisse litteras aiebant.” Ibid, fol. 42v.

- Ibid, fols. 42v–43r; summarized in Klibansky, Panofsky and Saxl, Saturn and Melancholy, 95–97.

- “Amoto itaque paroxismo plurima persepe futura predicunt, unde vulgares causam ignorantes demonum virtute hoc fieri putant.” Guaineri, Practica, 1.7, fol. 17r.

- Charles Homer Haskins, Studies in Mediaeval Science (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1924), 88, 110–111, 223.

- Klibansky, Panofsky and Saxl also note the novelty of this chapter: Saturn and Melancholy, 95.

- Nancy Siraisi, “Avicenna and the Teaching of Practical Medicine,” in Medicine and the Italian Universities 1250–1600, ed. Nancy Siraisi (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 73.

- “Ex malitia regiminis cibi et potus, et ex peccatis et preuaricationibus, et ultima causa ex maledictis demonibus qui dicuntur alabin.” Joannes Mattheus Ferrarius, Practica (Lyons, 1527), 1.8, fol. 54v; Temkin, Falling Sickness, 107.

- Ferrarius, Practica, 1.9, fols. 62r–v.

- “In hac ergo difficultate dimissis autoritatibus ad partem oppositam allegatis, teneo cum ista opinion Rasis primo Continens, scilicet quod imaginationes et cogitationes fortes cum premeditantur res profundas et longas aliquando adducunt ad hanc passionem non immutando realiter complexionem.” Ibid, fol. 62r.

- “Dico etiam quod preter has causas aliquotiens a demone spiritualiter inducunt tales mores.” Ibid, fol. 62v.

- Ibid, 1.8, fol. 58r.

- “Hoc etiam patet experientia: nam videmus aliquos vexatos a demonibus cum officio diuino per manus sacrorum religiosorum subito quasi et immediate ad sanitatem reduci.” Ibid, 1.9, fol. 62r.

- Jacquart, “Theory,” 159–160.

- Danielle Jacquart, “Le regard d’un médecin sur son temps: Jacques Despars (1380?–1458),” Bibliothèque de l’Ecole des Chartes 138 (1980), 70–71.

- See above, n. 14.

- Nancy Siraisi, “‘Remarkable’ Diseases, ‘Remarkable’ Cures, and Personal Experience in Renaissance Medical Texts,” in Medicine and the Italian Universities, 230.

- Caciola, Discerning Spirits, ch. 6; Elliott, Proving Woman, 250–263.

- Siraisi, “Remarkable Diseases,” 240.

- Catherine Rider, Magic and Impotence in the Middle Ages (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 198.

- Jacquart, “Regard,” 72–73.

- Robert Bartlett, The Natural and the Supernatural in the Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 20.

- David Harley, “Mental Illness, Magical Medicine and the Devil in Northern England 1650–1750,” in The Medical Revolution of the Seventeenth Century, ed. Roger French and Andrew Wear (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 121; Angus Gowland, “The Problem of Early Modern Melancholy,” Past and Present 191 (2006): 91–96.

Contribution (47-69) from Mental (Dis)Order in Later Medieval Europe, edited by Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Susanna Niiranen (Brill Academic Pub., 03.12.2014), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.