Exploring medieval English mysticism in the post-Reformation period.

By Dr. Victoria Blud

Research Associate

Centre for Medieval Studies

University of York

One of the central tensions from which mystic writing emerges is the mystic’s negotiation of the world she wishes to transcend. The space of mystic writing is both within and without, a threshold between this world and the next; the space proper to the mystic is always in some sense beyond what is knowable. As Michel de Certeau memorably put it, ‘He or she is mystic who cannot stop walking and, with the certainty of what is lacking, knows of every place and object that it is not that’; in the pursuit of the mystic destination, ‘[p]laces are exceeded, passed, lost behind it. It makes one go further, elsewhere’.1 The notion of space frequently structures the study of mysticism, whether this dimension is viewed as physical or metaphysical: the world of the mystic and her place within it is at once a condition on her union with God and the condition upon which she might attempt to express this union. Carmel Bendon Davis thus looked at mysticism and space as a philosophical continuum, considering the mystical experience as an ‘embodied’ one that occurs in what she called

mystical space. This is the multifaceted space of mystical experience and its subsequent representations (social and textual). It incorporates all aspects of the mystics’ life conditions: their personal experience of God; their physical environment; social influences, past and present; the influences of the communities in which they lived and wrote; their religious enculturation; and, additionally, their texts and the language of those texts.2

This essay looks at medieval English mysticism in the post-Reformation period, specifically the Benedictine nuns of Cambrai. This community holds particular interest for medievalists for their part in the dissemination and publication of Julian of Norwich’s writings:3 under the direction of Augustine Baker, they not only read widely in the medieval contemplative tradition but subsequently also nurtured members like Gertrude More, Margaret and Catherine Gascoigne and Barbara Constable, who attracted acclaim in their own right for their spiritual writings.4 Here, recusant readers and writers invoke many thresholds: between the world of the devotional writer or reader and the world at large; between medieval and early modern; between Catholic and Protestant Europe; between the self and community. Set apart from England, this little island of medieval learning was a port in one storm, but became the eye of another.

The development of the Cambrai community and the contemplative character of their approach to the cloistered life insisted on the continuing usefulness and relevance of medieval mystic texts to those who, seeing their native country leave Catholicism behind, had left England behind in turn. This mode of contemplation also had the effect of re-emphasizing withdrawal from the world, to an even greater extent than the convents in exile were already removed from the spiritual and political ambit of their native land. In its emphasis on the personal connection with God, the Cambrai method also afforded a confessor less influence over his charges. Certainly, in their approach the nuns at Cambrai were not representative of the English Benedictine community more generally, where Ignatian spirituality, emphasizing self-examination and the capacity to find God in all things but also collaboration and regulation, were more often favoured.5 The more individualistic of the nuns’ writings and Baker’s teachings were called into question for diverging from more conventional Jesuit principles. This essay therefore considers the nuns along with their medieval literary exemplars as a community that spanned and crossed chronological and topographical boundaries, investigating the influence of medieval mysticism and the opportunities it afforded women who pursued a devotional life that was in many ways anchored to another time and place.

In the post-Tridentine Catholic Church, both monasticism and the mission took on renewed and international significance. In England, the great Catholic families began to send their daughters overseas to new convents, especially in France and the Low Countries, where they awaited the return of Catholicism to their homeland. Some of the earliest were Brigettines from Syon abbey, who relocated to Lisbon in 1594, but within a relatively short period their example was imitated by Benedictines (Brussels, 1599), Augustinians (Louvain, 1609), Poor Clares (Gravelines, 1609), Carmelites (Antwerp, 1618) Franciscans (Brussels, 1619), Sepulchrines (Liège, 1642) and Dominicans (Brussels, 1660).6 The space of mystic writing was changing as well. This kind of writing always deals with an unattainable space, that of union with the divine – a space that is always at a remove. The classic, idiosyncratic and often reclusive English mystic was now more likely to be cloistered in an order; the complexion of English mysticism took on a different aspect as it was translated to new environments.

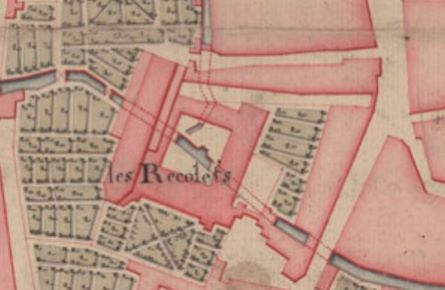

The Monastery of Our Lady of Comfort at Cambrai was established in 1623, when a small group of young women from prominent Catholic families crossed over to the Spanish Netherlands from England.7 The community had been planned with the English Benedictine Congregation from around 1620; on arrival at Douai the novices met with Frances Gawine of the older Benedictine cloister at Brussels, who would guide them in their new vocation. It was in the following year that the fledgling community would gain its most controversial member, when Augustine Baker arrived to serve as the convent’s spiritual director. In contrast to the Jesuits who had previously instructed the novices, Baker’s methods placed remarkable emphasis on the individual’s own engagement with spiritual discourses and texts, with the objective of attending to the ‘inner’ life of contemplative prayer and meditation, rather than imposing what might prove to be merely an ‘outer’ discipline. This is reflected in his summary of his recommendations to Gertrude More in his account of her life, where he writes that her method relied on ‘the exercise of affections, either as her propensity moved her to do by itself, or as she chose herself out of a book, or by custom, or from memory’.8 A bibliophile who associated with Cotton and Selden, Baker brought with him a great enthusiasm for medieval works and the mystics of the later middle ages, and he encouraged wide reading and active engagement with these works. The textual environment in which the nuns’ writings were composed would have included the works of Julian, Bridget of Sweden, Suso, Hilton and Tauler (the latter two favourites of Baker’s).9 As Baker’s methods were adopted, the Cambrai house became a close-knit community of readers, writers, patrons, commentators and translators. When some of the Cambrai books were transferred to a sister house, Our Blessed Lady of Good Hope in Paris (1651), the contemporary cataloguer thus listed one set of volumes as having been copied ‘the one by Sr Hilda’s hand, the other in every bodyes’.10

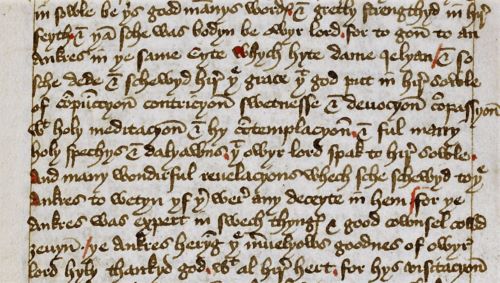

The manuscripts that were taken from the convent at Cambrai after the French Revolution are now preserved in the Archives Départementales du Nord at Lille. This cache of documents offers a window onto contemporary and transtemporal textual relationships in the sisters’ engagement with their texts. While the nuns’ books reveal wide interests, their fascination with medieval texts and their somewhat unusual reading informs their own writing, revealing the effects of participating in what might be considered a larger ‘mystic space’ such as that Davis suggested. The remains of the Cambrai collection are sparse, and what is in Lille represents much less than is recorded in Cambrai’s book lists, copied at the time the convent was vacated during the Revolution.11 In this are listed multiple works by the convent’s own mystic stars – nine copies of Gertrude More’s Spiritual Exercises, twenty-three copies of Augustine Baker’s Sancta Sophia, and of course Serenus Cressy’s edition of Julian of Norwich’s Shewings (fifteen copies). One short catalogue note (written in two different hands) in the records of the Paris house offers another insight into the original collection:

Bookes of F. Baker which I brought with mee to Paris.

Of Sicknes. Written by Ster Hilda. — — 4to

[cancellation]

2 Parts of the Mission in F. Bakers hand. 80

[cancellation]

2 Parts of the Stay in Ster Hilda’s hand. – 80

Of Confession in my Ladyes hand. — — 80

Caveats in F. Bakers hand. — —— —— 80

Five Treatises, in Ster Hilda’s hand, unbound — 80

The Anchor, in Ster Hilda’s hand — — — 80

The two parts of Thalamus Sponsi,

one by Sr Hilda’s hand, ye other in every bodyes

Our fathers at St. Edmonds have these following

Conversio forum (imperfect)

summarie D. H. Doubts

directions for praier12

Like most catalogues, the book lists of the Paris house include various tantalizing phantoms, a liminal library of texts that we know of and which might bear their traces in other works, but which have disappeared. The notes of the librarians preserve a multi-generational commentary as books are mislabelled, renamed and recatalogued. Some books have perhaps been taken out of circulation, as attested by another document headed, ‘A Chatilodg of the secrit boakes that our Rd Mo: Pir: is to keepe’.13

These ‘secret’ books – here absent, yet present – include Baker’s lives of Gertrude More and Francis Gascoigne (the brother of Abbess Catherine Gascoigne), ‘The Booke called ye Apolidg for his wrightings’, Baker’s treatise on the English mission, other works of his such as A Stay in All Temptations and The Book of Admittance, and ‘The Booke called Secrettum’, probably Secretum sive mysticum, Baker’s tract glossing the Cloud of Unknowing. Baker’s own youth was spent in spiritual tumult: having ‘lost his virtue and his Christian faith in bad company’ while at Oxford, he was later reconciled to the Catholic church, prompted by a brush with death while engaged on business.14 He arrived at Cambrai in 1624 to instruct the nuns in Benedictine contemplative prayer, and More’s life and the dissemination of her works thereafter also became tied up with his reputation.

Jenna Lay has argued for the importance of assessing the nuns’ work in the light of their independence of Baker as well as the extent to which they were influenced by his approach, using Barbara Constable as her example.15 A large number of manuscripts is attested in the Cambrai catalogue, though these are not listed individually but rather as a job lot, tagged with the underwhelming description: ‘839 volumes manuscrits de differents formats (ecriture moderne) presque tous relies en parchemin; peu interessans, et tous sur des objets pieus’.16 In the Lille collection, there are more texts that bear the marks of the nuns’ interactions with their reading matter; these can be fairly brief but still striking glimpses of how these texts became part of their meditations, and inspired them to respond, sometimes with arresting immediacy. In a Lenten sermon, for example, a flyleaf is covered with what look on the one hand like pen trials, but which, on the other hand, consist of the words ‘I’m sorry’, written over and over in the blank space.17

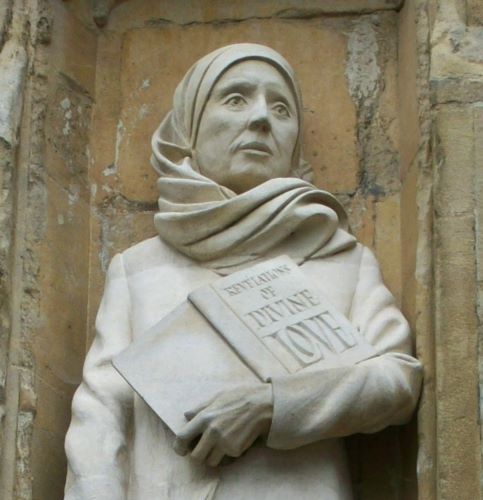

More subtle and frequent are the allusions in the writings of this community that read medieval texts to look both backwards to a former age and forwards to the return of the faith to England. This community has been studied often for its role in the dissemination and publication of Julian of Norwich’s writings, and certainly she made an impact. Margaret Gascoigne, for example, whose ‘loose papers’ were edited into a series of soliloquies or Devotions by Baker upon her death, drew on Thomas à Kempis, Gertrude of Helfta and Julian in her writing, but Julian was so important to Margaret that on her deathbed, she had a quotation from Julian’s Showings placed where she could gaze upon it in her last illness:

She caused one, that was most conversant and familiar with her, to place (written at and underneath the Crucifix, that remained there before her, and which she regarded with her eyes during her sickness and till her death) these holy words that had sometime ben spoken by God to the holie Virgin Julian the ankresse of Norwich, as appeareth by the old manuscript Booke of her Revelations, and with the words our Dame had ever formerlie been much delighted: ‘Intend (or attend) to me, I am enough for thee: rejoice in me thy Saviour, and in thy Salvation.’ These words (I say) remained before her eyes beneath the Crucifixe till her death.18

Since the Council of Trent, enclosure for nuns was now mandatory (reinforcing Boniface VIII’s Periculoso) and subject to heavy sanctions for violation;19 it is hardly surprising that the Lille collection hints at further devotion to quasi-anchoritic enclosure. There is an anchoritic ring, for instance, to a poem found in the leaves of a book belonging to Ann Benedict:

Alone retired in my natiue cell,

At home within my self, all noyse shut out,

In silent mourning I resolue to dwell,

With thoughts of Death, Ile hang my walls about:

All windows close, Faith shall my Taper be,

At whose dim flame Ile Hell & Judgment see.20

With its claustrophobic imagery of a cell with tight-closed windows, in which the speaker contemplates death, the verses recall the strict admonishments of anchoritic guides on the subject of looking through one’s windows, and the temptations that begin with the overstimulation of the senses. This particular poem – with its images of darkness and sensory withdrawal – has been linked to the artistic tradition of interpreting John of the Cross’s Dark Night of the Soul (a work also known to the convent);21 however, while that work evokes a venturing forth, a journey, with a guide unseen and a lover as the goal, this poem turns its attention inward to the practice of virtue. Though it describes a spiritual ascent, the perspective remains very much shut in, with the speaker striving in subsequent stanzas to make hunger into food, thirst into drink, clothing from dust.

The project of writing and translating also encompassed making English versions of more recent Continental works. Among the survivors from Cambrai, there are excerpts from Tauler (20H 3, 39), Teresa de Avila (20H 38, 39, 48), Blosius (20H 38), Harphius (20H 23, 24, 35), Girolamo Savonarola (20H 17), Ruesbroec (20H 33), St. Gertrude (20H 39) and Thomas à Kempis (20H 39, 48). Jeanne de Cambrai’s commentary on the Song of Songs was translated as The building of divine love by Agnes More (cousin to Gertrude),22 and the work of Francis de Sales is represented by dozens of printed texts by 1793. Predictably, though, there is a firm attachment in both the printed and handwritten material to the British Isles. The 1793 catalogue has an extensive section devoted to printed historical works, with traditional accounts from the medieval history of the English church, including Josephus, Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica, and another chronicle of a displaced religious community, Simeon of Durham’s Libellus de exordio. In the tradition of Catholic historiography the handwritten histories in the collection also draw on the medieval past.23 The Cambrai writers and copyists accordingly represent a range of windows onto this outside world, including a description of ‘S Winefrid’s Well called Holy Well in Flintshire North Wales, the most extraordinary & surprising spring perhaps in the world’, a short excerpt from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, and a brief account of a romance entitled ‘A challenge brought to K. Arthur from a king of North Wales’.24

So the image that emerges of the community is one of quiet withdrawal and yet close sorority; on a macro level, attachment to the traditions and history of a forsaken homeland juxtaposes both current geographical location and the effort to forget the world. Gertrude More unites some of these conflicted influences and desires. She was one of these nuns in exile, participating in the displaced continuation of English Catholic piety. Born Helen More in 1606, she had an illustrious and somewhat overwhelming lineage – she was the great-great-granddaughter of Sir Thomas More, with whom she is inevitably linked in the contemporary literature. Her father, Cresacre More, had provided financial support for the foundation of the Cambrai convent, and Helen entered Cambrai with two of her cousins, Grace (in religion, Agnes) and Anne; her younger sister Bridget would go on to be prioress of their convent’s sister house, Our Blessed Lady of Good Hope in Paris.

Alongside her cousins, Helen professed (as Gertrude) in January 1625. When she entered into religion she was, as she describes herself, ‘cheerful, merry and free’.25 Her first eighteen months were difficult and Baker describes her distress at the spiritual confusion she experienced in trying to reconcile her vocation with her ‘defectuositie’.26 Like others at Cambrai, she was influenced by the wide-ranging medieval mystic tradition in which she was schooled by Baker.27 Though her writing engages with the apophatic or negative theology of Pseudo-Dionysius and his heirs, More was also particularly fond of the Psalms, Proverbs, the Song of Songs; she was a devotee of St. Augustine, after whose Confessions she models her own major work, and Evelyn Underhill declared that it displayed ‘the romantic and personal side of mysticism even more perfectly than [that of ] St. Teresa’.28 The metaphors in her meditations are often time-honoured ones (heat and fire, and dryness parched by the divine fountain), but the familiar can also be arresting:

Lett all things praise thee, & lett me in all praise thy diuine Matie wth them that loue thee. Behold, fire, ice, snow, thunder, lightning, haile, & the spiritt of stormes do thy will; & yet I in all contradict it, who am capable of thy loue, & am inuited so manie wayes by thee, my God. […] Lett it wholie consume me, that I may be wholy turned into loue, & that nothing else may be desired by me. Lett me be drowned & swallowed vp in that sea of diune loue, in [which] my soule may swimme for all eternity, & neuer more by sinne be seperated from thee.29

The reader is reminded vividly that this is a writer who reached her new life after undertaking a sea voyage, and who is separated from familiar scenes by a strait of water. Philip Edwards has suggested that in this period in particular, ‘the traditional image of the frail ship venturing into the power of the unpredictable and uncontrollable sea must have become more alive for writers, even if they never went to sea’.30 Yet More imagines the sea not as a traversible space that separates her from her destination but as the destination itself, the limits to comprehension in which she will become lost and found.

Such maritime images thus draw on earlier exemplars but also reach beyond them. Sebastian Sobecki’s study of the sea in medieval insular thought considered the sea as the site of primal fear, as the condition for pilgrimage, as wilderness, as the limit of the world, as purgatory, as spiritual obstacle to be traversed, as symbol of challenge, chaos, or seat of the Devil.31 As Christopher Daniell noted, it is rather unusual for Christians to drown. In the bible and in saints’ lives, the faithful are, indeed, often saved from the waters and borne over them.32 St. Bridget, who was shipwrecked before she was even born, speaks of the sea in exactly this way, as the storm-tossed waters that the ship of the body must navigate:

The Son speaks: “Listen, you who long for the harbor after the storms of this world. Whoever is at sea has nothing to fear so long as that person stays there with him who can stop the winds from blowing, who can order any bodily harm to go away and the rocky crags to soften, who can command the storm-winds to lead the ship to a restful harbor.”33

Elsewhere, Bridget also paints an image of the body as a boat with a bad sailor inside who lets in water until the vessel sinks, or the three kinds of ship in varying states of repair through which men must travel through the seas of the world.34

For Julian, meanwhile, the understanding of God’s providence is evoked in a vision of a seabed expedition:

One time my understanding was led downe into the sea grounde, and ther saw I hilles and dales grene, seming as it were mosse begrowen, with wrake and gravel. Then I understode thus: that if a man or woman wher there, under the brode water, and he might have sight of God — so as God is with a man continually — he shoulde be safe in soule and body, and take no harme.35

Yet Julian’s seascape is a situation that is escaped through God’s aid, as opposed to the scene in which the soul melts into divine oneness. More figures water and especially the sensation of drowning and being completely surrounded and submerged in water as the route to God, not to perdition. In her poem Amor ordinem nescit, More writes of the wish to ‘swim’ in divine love, but only until she is ‘absorpt’ by and can ‘melt into’ this sea of love; the soul’s goal is to drown and not to float.36 Yearning to ‘be swallowed up in the bottomless ocean of all love’,37 she also echoes Tauler, who glosses Psalm 61 – ‘deep calls to deep’ – as an expression of how ‘the human spirit is lost in God’s spirit – sunk in the fathomless ocean of the Godhead’.38 In More’s imagery, unusual in sea metaphors, the depths are the object of desire.

In 1633, Baker departed Cambrai after controversy over his work: Francis Hull, the chaplain, accused him of anti-authoritarian preaching and Baker’s writings were investigated for heretical leanings. More and the abbess Catherine Gascoigne wrote in his defence; Baker was cleared but later removed to Douai. However, the Cambrai nuns continued to provoke controversy after Baker’s death. In 1655, Claude White, president of the English Benedictine Congregation, demanded that Abbess Catherine Gascoigne release the original Baker manuscripts, accusing the nuns of harbouring ‘poysonous, pernicious and diabolicall doctrine’.39 Though Baker’s works had been judged orthodox (by examiners that included White himself), White’s insistence brought further troubles to the convent.40 His proposed censorship, however, only focused on autograph manuscripts, not the works composed by the nuns in this model. Around the same time, Serenus Cressy was preparing Baker’s works for print, under the title Sancta Sophia (1657).41

While the doctrine may not have been diabolical, the community looked beyond Jesuitical methods, and the character of their practice was individualistic to the extent that a nun might even feel enabled to go beyond the supervision of a spiritual director on her deathbed. More’s Apology for Herself and Her Spiritual Guide, written in defence of Baker’s methods, is certainly wary of the methods used by instructors who came before him, remarking, ‘They speak with little consideration who say it is enough to do what a counsellor adviseth’ and saying of the Jesuit insistence on strict obedience that the novice who observes their instructions ‘grows but by this into favour with Superiors, and companions, … thinking that if she can please them she dischargeth her duty to God and her obligation of tending to perfection’.42

In the section of the Apology relating to confession, More again draws on Tauler, remarking that ‘Tauler saith that it is as easy for one that hath an aptness for an internal life, and will be diligent and observe in it, to note, observe, and discern the Divine call within him, as it is for one to distinguish his right hand from his left’.43 More argues that no one should place such store in the word of a confessor that she forgets her confidence should be in God, for if she did, then she is destined to ‘die perplexed and troubled’.44 Confessors were also wont to disagree among themselves: the one might warrant the penitent where the other would bring her into mortal dread. More herself was suspicious of one particular confessor’s motives and his desire for control, asking, ‘should I […] put my soul into his hands, who desired to know all that had passed in my life, to inform him in some things he desired to know out of policy, thereby to tie me to himself more absolutely?’45 Suspecting that such policy or stratagem reflected not piety and judgment but rather a bid for personal control over her, More explains how the autonomy encouraged by Baker’s methods enabled her to evade such tactics.46

More’s faith in the self-directed methods she had practised was indeed fast until the end. Margaret Gascoigne had Julian for her deathbed focus; when More died (of smallpox, aged 27), though she had made a confession during her illness, she declined to speak with a priest the night before she died; she did not even ask for Baker, but asked those with her to ‘give him thanks a thousand times, who had brought her to such a pass that she could confidently go out of this life without speaking to any man’. Catherine Gascoigne remarked ‘how confidently she died, relying wholly upon God’.47

The nuns of Cambrai were engaged and educated readers who benefited from a programme of devotion and spiritual practice that drew on the texts of the medieval mystic past. These works enabled them to participate in a special kind of literary community in which they were encouraged in their affinity with earlier greats like Julian, so that their figurative isolation not only saw them excluded from Protestant realms but ultimately included in an insular medieval tradition. The engagement with the mystic by which the sisters diverged from the usual authorities placed the nuns beyond the usual pattern of Benedictine spirituality, and made a sort of rebellion even out of strict claustration.

The experience of and longing for transcendence, going beyond the world, are predicated on the awareness of space that is often inextricable from mystic endeavour. de Certeau remarked that in the era that came after the middle ages, mysticism was ‘a suspect neighbourhood’, a ‘stigmatized region’ of conflict and plots – mysticism in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was ‘generally inseparable from quarrels and struggles. No mystics without trials’.48 Not only did the Cambrai nuns venture out of their country, out of the newly Protestant territory, to be cloistered away from the world, but they also engaged with the writings of self-directed, sometimes outspoken recluses, and occasionally even with those who might be called heretics.49 As sisters who were happy to be doing it for themselves, there was an extent to which they even stood outside of the norms of their own order: for some in the Benedictine Congregation they were beyond another pale.

The nuns’ unusual independence in spiritual self-governance was bolstered by the emphasis on their own reading and interpretation in the Cambrai method initiated by Baker, but also by the invocation of a medieval past, which represented a space beyond Ignatian teachings, beyond the Protestant present, and beyond the cloister. This ‘medievalism’ contributed to the sisters’ spiritual methodology and singular style of devotion, which intersected with the liminal space in which they practised it: drawing from models from a different space and time – mystic space, perhaps – which supported a more independent and individualistic approach to life in religion that, while benefiting by the encouragement of a male director, did not rely on it. From the convent of Our Lady of Comfort, what we have are only fragments of what was, but these remnants offer a tantalizing glimpse of the tensions between orthodoxy and rebellion, independence of confessors and devotion to them, quiet seclusion and textual community, medieval writers and their readers in exile.

Endnotes

- M. de Certeau, The Mystic Fable: Volume One – the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, trans. M. B. Smith (Chicago, Ill., 1992), p. 299.

- C. Davis, Mysticism and Space (Washington, D.C., 2008), pp. 5–6 (original emphasis).

- For the early modern career and early publications of Julian’s Showings, see J. Summit, ‘From Anchorhold to closet: Julian of Norwich in 1670 and the immanence of the past’, in Julian of Norwich’s Legacy: Medieval Mysticism and Post-Medieval Reception, ed. S. Salih and D. N. Baker (Basingstoke, 2009), pp. 29–47; J. Bolton Holloway, Julian Among the Books: Julian of Norwich’s Theological Library (Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 2016), pp. 246–88. On the role of early modern Catholic women in preserving medieval devotional and literary works, see J. Summit, Lost Property: the Woman Writer and English Literary History, 1380–1589 (Chicago, Ill., 2000), pp. 109–62; D. Wallace, ‘Nuns’, in Cultural Reformations: Medieval and Renaissance in Literary History, ed. J. Simpson and B. Cummings (Oxford, 2010), pp. 502–26.

- See Gertrude More (CB137), Margaret Gascoigne (CB077), Catherine Gascoigne (CB074), Barbara Constable (CB043) in ‘Who Were the Nuns?’, Queen Mary University of London <https://wwtn.history.qmul.ac.uk> [accessed 6 Dec. 2017].

- The Spiritual Exercises of Ignatius of Loyola (composed 1522–48) were regularly used in the convents and were adapted for a number of different audiences. They comprise exercises and meditations moving through purgative, illuminative and perfective stages; novices would begin with spiritual and emotional preparation before graduating to contemplation and imitation of Christ’s life, and eventually exercises for affective association with Christ. See Ignatius of Loyola: Spiritual Exercises and Selected Works, ed. and trans. G. E. Ganss (Mahwah, N.J., 1991). The method focuses on the dialogue between director and exercitant, with a view to equipping directors with the necessary tools to guide their charges. However, as L. Lux-Sterritt observes, ‘The Jesuit Exercises were devised for the use of men, and of missionaries: nuns were neither’. See ‘Clerical guidance and lived spirituality in early modern English convents’, in Spirit, Faith and Church: Women’s Experiences in the English-Speaking World, 17th–21st Centuries, ed. L. Lux-Sterritt and C. Sorin (Newcastle, 2012), pp. 51–78, at p. 67.

- For the establishment and eventual repatriation of the English convents in exile, see English Convents in Exile, 1600–1800, ed. C. Bowden (6 vols., 2013), vi, p. xvii.

- Later Our Lady of Consolation; now Stanbrook abbey, Wass.

- The Life and Death of Dame Gertrude More, ed. B. Wekking (Analecta Cartusiana, cxix, no. 19, Salzburg, 2002), p. 36.

- For the account of Baker’s reading and correspondence with Cotton, see P. Spearitt, ‘The survival of mediaeval spirituality among the exiled black monks’, American Benedictine Review, xxv (1974), 287–316. Sancta Sophia or Holy Wisdom, the most well-known of Baker’s works, has been recently re-edited: The Sources of Fr. Augustine Baker’s ‘Sancta Sophia’, ed. J. Clark (Analecta Cartusiana, cxix, no. 43, 2 vols., Salzburg, 2016).

- C. Walker analysed the implications of this collaboration on the part of the nuns in her article ‘Spiritual property: the English Benedictine nuns of Cambrai and the dispute over the Baker manuscripts’, in Women, Property and the Letters of the Law in Early Modern England, ed. N. E. Wright, M. W. Ferguson and A. R. Buck (Toronto, 2004), pp. 237–55. Walker highlighted the strength of Gascoigne’s argument that the Baker papers were, like all books in a Benedictine community, held in common and did not belong to any one individual, but also the difficulty the Cambrai convent had to negotiate in order to retain their autonomous spiritual practice: ‘What rights did the religious women have to the documents held in their possession, which arguably they had jointly created with Baker?’ (p. 239).

- Catalogue des livres provenant des religieuses angloises de Cambray: Book List of the English Benedictine Nuns of Cambrai c.1739, ed. J. T. Rhodes (Analecta Cartusiana, cxix, no. 42, Salzburg, 2013). Bowden has made an extensive survey of the commonalities and distinctions among the convents in exile with regard to their programmes of reading and writing, and the creation and subsequent fates of their libraries (C. Bowden, ‘Building libraries in exile: the English convents and their book collections in the seventeenth century’, British Catholic History, xxxii (2015), 343–82).

- Paris, Bibliothèque Mazarine MS. 4058 (loose leaf ). See also J. T. Rhodes, ‘Augustine Baker’s reading lists’, The Downside Review, cxi (1993), 157–73.

- Paris, Bibliothèque Mazarine MS. 4058 (loose leaf ). On the role of abbesses, their discrimination and influence on the nuns’ reading in the convents, see Bowden, ‘Building libraries’, pp. 350–52.

- D. Knowles, The English Mystical Tradition (1961), p. 154. On Baker’s life, writings and teachings, see the essays in That Mysterious Man: Essays on Augustine Baker with Eighteen Illustrations, ed. M. Woodward (Abergavenny, 2001); Dom Augustine Baker, 1575–1641, ed. G. Scott (Leominster, 2012).

- J. Lay, ‘An English nun’s authority: early modern spiritual controversy and the manuscripts of Barbara Constable’, in Gender, Catholicism and Spirituality ,ed. L. Lux-Sterritt and C. M. Mangion (Basingstoke, 2011), pp. 99–111.

- ‘839 manuscript volumes in different formats (modern writing), almost all bound in parchment; little of interest, and all on pious matters’. The entry notes among these works sermons, theological treatises, saints’ lives, epistles, gospels, meditations, prayers, paraphrases, psalms, advice, instruction and ascetic tracts (Rhodes, Catalogue, p. 189).

- Lille, A.D.N. 20H 13.

- Downside abbey MS. Baker 42, pp. 232–34. Quoted in The Writings of Julian of Norwich, ed. N. Watson and J. Jenkins (University Park, Penn., 2006), pp. 438–9. On Gascoigne’s engagement with Julian and the convent’s reception of Gascoigne’s devotions, see J. Goodrich, ‘“Attend to me”: Julian of Norwich, Margaret Gascoigne and textual circulation among the Cambrai Benedictines’, in Early Modern English Catholicism: Identity, Memory and Counter-Reformation, ed. J. E. Kelly and S. Royal (Leiden, 2017), pp. 105–21; G. Gertz, ‘Barbara Constable’s Advice for Confessors and the tradition of medieval holy women’, in The English Convents in Exile, 1600–1800: Communities, Culture and Identity, ed. C. Bowden and J. E. Kelly (2017), pp. 123–38. See also M. Truran, ‘Spirituality: Fr Baker’s legacy’, in Lamspringe: an English abbey in Germany, 1643–1803 (York, 2004), pp. 83–96.

- For the development of the decrees of enclosure for nuns, see E. M. Makowski, Canon Law and Cloistered Women: Periculoso and its Commentators, 1298–1545 (Washington, D.C., 1997).

- A.D.N., 20H 25. Also edited in D. L. Latz, Glow-Worm Light: Writings of 17th-Century English Recusant Women from Original MS. (Salzburg, 1989), p. 70.

- See discussion by C. Koslofsky (referencing P. Choné’s analysis), in Evening’s Empire: a History of the Night in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge, 2011), pp. 78–9. Among the Cambrai papers, excerpts from John of the Cross appear in several manuscripts including 20H 31, 38, 39 and 48.

- A.D.N. 20H 18.

- For instance, A.D.N. 20H 51, which includes a history of England (drawing on Bede), and of Europe and the Holy Land, and 20H 52, a history of the aristocracy of Wales that lists Merlin, Vortigern and Arthur.

- A.D.N. 20H 50, 51 (fo. 24v) and 54 respectively.

- G. More, ‘Apology’, in The Inner Life and Writings of Gertrude More, ed. B. Weld-Blundell (2 vols., 1910–11), p. 279.

- Wekking, The Life and Death of Dame Gertrude More, p. 29. For Baker’s indebtedness to Blosius in his account of Gertrude More’s life, see V. van Hyning, ‘Augustine Baker: discerning the “call” and fashioning dead disciples’, in Angels of Light? Sanctity and the Discernment of Spirits in the Early Modern Period, ed. C. Copeland and J. Machielson (Leiden, 2012), pp. 143–68.

- See M. Norman, ‘Dame Gertrude More and the English mystical tradition’, Recusant History, xiii (1976), 196–211; D. L. Latz, ‘The mystical poetry of Dame Gertrude More’, Mystics Quarterly, xvi (1990), 66–82.

- E. Underhill, Mysticism: a Study in the Nature and Development of Man’s Spiritual Consciousness (1949), p. 88.

- Confession 16, Fr. Augustine Baker OSB, Confessiones Amantis: the Spiritual Exercises of the most Vertuous and Religious Dame Gertrude More, ed. J. Clark (Analecta Cartusiana, cxix, no. 27, Salzburg, 2007), pp. 83–4.

- P. Edwards, Sea-mark: the Metaphorical Voyage. Spencer to Milton (Liverpool, 1997), p. 1.

- See S. I. Sobecki, The Sea and Medieval English literature (Cambridge, 2008), esp. pp. 25–47. For comparison with seagoing pilgrimage narratives, see E. Bekkhus in this volume, although of course Bekkhus is talking about Irish traditions.

- C. Daniell, Death and Burial in Medieval England, 1066–1550 (1997), p. 71.

- The Revelations of St. Birgitta of Sweden, trans. D. Searby, ed. B. Morris (4 vols., Oxford, 2006–15),i. 91.

- Revelations of St. Birgitta, i. 71–3; ii. 166–7.

- Watson and Jenkins, The Writings of Julian of Norwich, Long Text, ch. 10 (ll. 16–20).

- ‘O lett me, as the siluer streamesInto the ocean glide,Melt into that vast sea of loueWhich into thee doth slide!’ In Oxford, MS. Bodleian Rawlinson C. 581, fos. 1–7v, edited in Confessiones Amantis, ed. Clark, pp. 1–11, at p. 8.

- More, Writings, pp. 147–8. ‘Fragments: Various Sentences and Sayings of the Same Pious Soul Found Among her Papers’. This phrase is also found in the Apology (More, Writings,p. 289).

- Second sermon for the fifth Sunday after Trinity, ‘Fishing in Deep Waters’, in The Sermons and Conferences of John Tauler of the Order of Preachers, surnamed ‘The Illuminated Doctor’ being his Spiritual Doctrine, ed. and trans. W. Elliott (Washington, D.C., 1910), pp. 442–7, at p. 447. Baker remarks in his own account of More’s life that a soul away from the divine is like a whale in a brook: ‘the great creature has not space enough to swim or plunge […] it ever desires the ocean which, for its depth and wideness, is capable of containing it and millions of others’ (Wekking, The Life and Death of Dame Gertrude More,p. 231).

- C. Gascoigne to A. Conyers: Oxford, MS. Rawlinson A.36, fo. 45, Bowden, Convents in Exile,iii. 289. On the Baker scandal, see C. Walker, Gender and Politics in Early Modern Europe: English Convents in France and the Low Countries (2003), pp. 143–7; Walker, ‘Spiritual property’, in Wright, Ferguson and Buck, Women, Property and the Letters of the Law, pp. 237–55; Lay, ‘An English nun’s authority’, pp. 99–114.

- In a letter of 3 March 1655, Christina Brent (CB015) confided to Anselm Crowder her wish that ‘the affaire of the books rest’, so that the strain and practical problems it had brought – including the withholding of permission for novices to profess and thereby endow the convent – might be concluded (Bowden, Convents in Exile, iii. 291).

- Baker’s works were edited by Dom. Justin McCann OSB and, more recently, by J. Clark for the Analecta Cartusiana series. The new editions in particular have renewed interest in the affair that led to Baker’s and Hull’s removal to Douai, and a certain degree of scepticism about the guileless image of Baker promulgated by the Cambrai community and in Cressy’s rather coy editing of Sancta Sophia. See D. Lunn, ‘Augustine Baker (1575–1641) and the English mystical tradition’, Jour. Eccles. History, xxvi (1975), 267–77; L. Temple, ‘The mysticism of Augustine Baker, OSB: a reconsideration’, Reformation and Renaissance Review, xix (2017), 213–30.

- More, ‘Apology’, in Writings, pp. 261, 263.

- More, ‘Apology’, in Writings, p. 243.

- More, ‘Apology’, in Writings, p. 244.

- More, ‘Apology’, in Writings, pp. 245–6.

- A later treatise from Cambrai reflects the continuity of this determination among the Cambrai sisters in that it is entitled, ‘A notable treatise of the meanes to be observed by a Soule to come to the perfection of a Spirituall life, either w[i]th or w[i]thout a Director’ (A.D.N., 20H 35).

- More, Writings, pp. 271, 279 (Augustine Baker’s accounts from lay sister Hilda Percy and the abbess Catherine Gascoigne).

- M. de Certeau, The Mystic Fable: Volume Two – the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, ed. L. Giard, trans. M. B. Smith (Chicago, Ill., 2015), p. 5; de Certeau’s la mystique is translated by Smith as mystics.

- A.D.N., 20H 17 consists of a tract by ‘Geronimo de Ferrara’ – Girolamo Savonarola. It is copied seemingly out of concern for the completeness of the nuns’ seclusion, advising, ‘Nor is it enough […] that the convent door be kept allwaies shutt; the spouse of Christ must not only flie into a monastery to hide herselfe from the world, but even there seeke a farther retreate’. A.D.N., 20H 17, ‘A short Treatise of ye three principall Vertues and Vows of Religious Persons’(11v-12). Also in Selected Writings of Girolamo Savonarola: Religion and Politics, 1490–1498, ed. A. Borelli and M. Pastore Passaro (New Haven, Conn., 2006).

Chapter 5 (75-89) from Gender in Medieval Places, Spaces and Thresholds, edited by Victoria Blud, Diane Heath, and Einat Klafter (University of London Press, 01.03.2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.