The alien subsidies are not the only source for resident immigrants in England.

By Dr. Jessica Lutkin

Head of Grant Development

The National Archives Fellow

Royal Historical Society

The publication in 1998 of The Alien Communities of London in the Fifteenth Century, edited by J. L. Bolton, presented an important reassessment of the alien population of London and its suburbs. His reappraisal of the statistics afforded a new perspective on the ground-breaking research of Sylvia Thrupp, undertaken in the 1950s.1 Her articles on immigrants in England in general and in London in particular were pioneering, and an enormous undertaking which have been relied upon heavily by many students of the period.2 However, against a backdrop of contemporary racial tension as a result of mass immigration following the end of the Second World War, her view of the immigrant experience in the fifteenth century was through somewhat rose-tinted spectacles. As a result of research since Thrupp’s publications, the rose-tinted spectacles have been removed, providing much greater knowledge of the popular feeling against immigrants in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.3 Revising Thrupp’s figures for London, Bolton concluded that ‘resident aliens formed at least six per cent of the population, a figure substantially higher than the two to four per cent suggested by Thrupp’.4 He also raised many further questions, delving into the problems with the data available to us and our interpretation of it. This chapter offers further analysis, adding to the work of both Bolton and Thrupp, and revisiting many of the questions posed by Bolton, including the permanence of the alien community in London.5

The present study is primarily based on the fifteenth-century alien subsidies, as used by Thrupp and Bolton, supported by various other documents.6 The alien subsidy was granted by parliament at irregular intervals between 1440 and 1487. It was instigated partially as a response to the popular unrest against resident immigrants, and was in effect a poll tax. Initially granted by parliament in 1440, the grant was renewed a further five times until 1487. The tax divided the aliens into two groups, categorized as householders and non-householders, initially paying 16d and 6d respectively. Children under the age of twelve were not liable for the tax, and neither were alien wives of English husbands.7 With each new grant of the subsidy, these groups evolved, and new rates were introduced for certain groups, such as merchants. Exemptions for previously included national groups increased, beginning with the Channel Islanders and the Irish, until by 1483 the Hanse, Normans and Bretons were excluded, as were certain merchants from Spain, Italy and Brittany.8 The initial enthusiasm for the assessment and collection of the tax soon waned, and despite the renewals of the subsidy in 1442, 1449 and 1453, only the first grant in 1440 and the penultimate grant in 1483 saw comprehensive assessments of England’s resident aliens.

Not only were there regular changes to the conditions of the subsidy, but there was little regularity in the taxation across the country. The assessment and collection of the tax was left to interpretation by the local authorities, resulting in wide variations of detail and accuracy in the surviving sources. Indeed, any fervour in making the initial assessments soon dissipated, and the collectors seem to have been lenient with non-payers. While it appears that London was particularly rigorous and diligent in its assessment of the tax, especially when compared to other counties of England, there was not as much diligence when it came to collecting payment. This comes as little surprise – Londoners were the most vociferous when it came to the alien population, and perhaps saw this poll tax as a useful local census and a tool against those it was not keen to accommodate in the city.9

While they are the most substantial source, the alien subsidies are not the only source for resident immigrants in England. Other documents include letters of denization, which have been gleaned from patent rolls, as have the details of those swearing an oath of fealty to the crown.10 Other grants in the patent rolls record the names and details of resident aliens, such as letters of protection, where deemed relevant, and licences to remain.11 Denization rolls from the mid Tudor period are also a vital source of information.12 While they reveal a relatively small number of aliens, they provide an important alternative and supporting view of the immigrant population in London.13

In summary, between 1336 and 1584, 17,376 instances of resident aliens can be positively identified in London.14 Of these, 325 individuals in London swore the oath of fealty in 1436, 144 obtained letters of denization (the majority in 1544), fifty-one obtained licences to remain (predominantly Scots in 1480/1), and twenty-two were granted letters of protection (in the fourteenth century). The remaining 16,823 are all to be found in the tax assessments between 1441 and 1488. In London’s suburbs, a further 6,725 aliens can be positively identified living in Southwark (631) and Middlesex (6,094). However, the scope of this chapter does not allow for a full discussion of the suburbs, and will focus on the city’s alien population.15

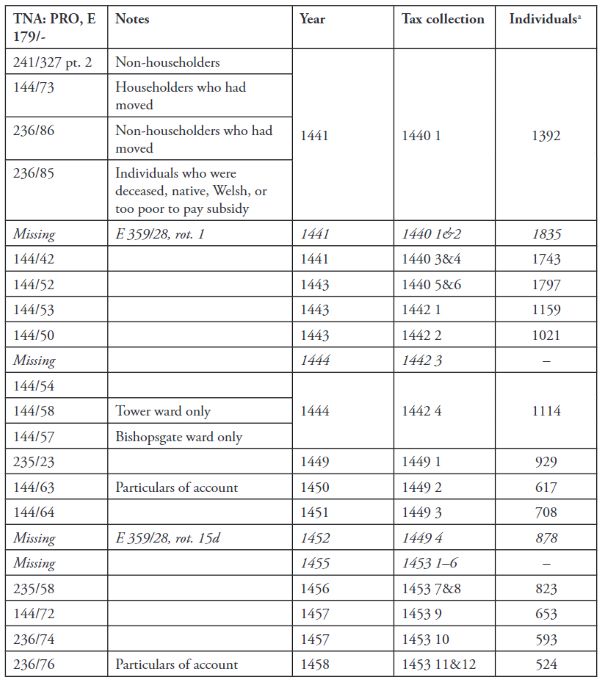

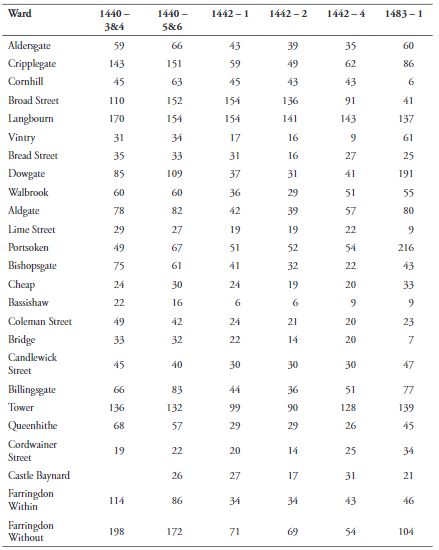

The survival rate of the alien subsidy documents for London is particularly high, and while there are some gaps in the records, their loss is not felt too greatly. As Table 7.1 demonstrates, documents survive for each parliamentary grant of the subsidy (in 1440, 1442, 1449, 1453, 1483 and 1487). For some years only the particulars of account have survived, and consequently only the sum total of individuals for the year are known, rather than names, and for a couple of years where no individual subsidy records survive at all, the main account roll at least provides the summary figures.16 The gap in the figures highlighted by Thrupp at the beginning of the period can therefore be satisfactorily filled.17

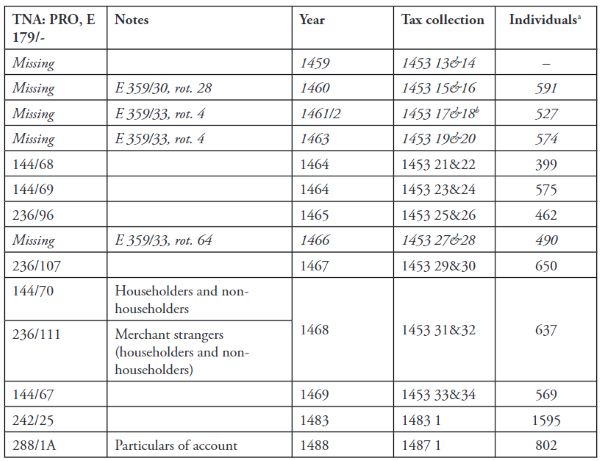

Figure 7.1 shows the distribution of the London aliens in the tax records. The largest numbers are to be found in the early collections; the numbers then fall through the middle of the period, and do not rise back to the same level again until 1483. Bolton calculated that in 1483/4 there were some 3,400 alien men, women and children in London and its suburbs, forming at least six per cent of the general population.18 Using Bolton’s assumptions and calculations, it can be estimated that in 1441 a similar number were living in the city and its suburbs, at approximately 3,540.19 However, there was a decline in the number of immigrants recorded as resident in London between the dates 1440/1 and 1483/4.

The overall pattern of decline is typical of the patterns to be found across the rest of the country, for example as shown in Figure 7.2 illustrating Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire. Yet the difference is in the sheer quantity of named individuals. The lowest number of aliens assessed in London was in 1464, where 399 names were returned. While Bolton views this dip as unlikely to have been caused by trade depression and plague alone, the dip in London is not as exaggerated as it is for the other counties of England.20 In the 1450s and 1460s in the counties of England, the number of individuals fell to the tens and twenties, and in some cases none were recorded at all. It is highly notable that the individual fall-off rate was not as high in London as in other counties. The average number of aliens assessed in London fell 64 per cent from the 1440 subsidy assessments to the 1453 assessments, whereas in Hampshire and Southampton, for example, the fall was 96 per cent.21 This suggests that, taking into account the increasing number of exempt nationalities, the authorities in London were exceptionally diligent in this matter, even in a plague year.

The 16,822 instances of aliens assessed to pay the alien subsidy across the forty-three year period in London comprised a wide variety of individuals, and the figure also includes the wives of aliens, even though they were not specifically taxed until 1483, when they were assessed as non-householders.22 The vast majority of individuals were male, totalling 13,952, while 2,804 were female (1,452 of which were married to an alien), and sixty-six individuals cannot be identified by gender. There were 5,673 male householders who paid the higher tax rate, while 8,276 were male non-householders. Of the unmarried women, only 225 were recorded as householders, leaving 1,045 who were non-householders, and of the total 1,270 unmarried women, forty-three were widows. A total of 487 aliens were recorded as servants to 222 alien masters and mistresses, averaging two per household. The vast majority of alien servants in an alien household were male (424), while sixty-one were female and six were of unrecorded gender.

A number of families can be identified, many of which are apparent in the published 1483 assessment, as they are neatly listed in familial groups.23 Some families in earlier assessments can also be identified, such as Arnold Abbrethen and his two unnamed sons, assessed in 1444, living in either Bishopsgate ward or Broad Street ward.24 Henry Berman was assessed as a householder in Aldgate ward 1441, and he had two children over the age of twelve, John and Joan.25 In total, twenty-six sons and twenty-one daughters were assessed to be taxed. Doubtless there were many more children, as discussed by Bolton, but were under the age of twelve and so not assessed. It is a difficult task to estimate how many children were actually classed as aliens, as many children of immigrant couples could have been and were born in England, and therefore second-generation immigrants and technically English.26 This is particularly in evidence in the later record of the Westminster denization roll of 1544, where many individuals are listed as being married and having children, and careful note is made that the children were born in England. Only a handful are positively identified as being foreign-born. It is highly likely that this was a similar scenario a century earlier. It is also impossible to suggest how many male immigrants were married to Englishwomen, and so reflecting their integration into the London community. Inter-marriage did occur, again as the Westminster denization roll demonstrates. Many were recorded as being married to Englishwomen, and in 1544 one London resident, Archilus de le Garde, had been married to his English wife for twenty-eight years.27

A satisfactory statistical analysis of the occupations of London’s resident immigrants is hard to reach, as occupations are only given in detail in the 1483 assessment, and have been thoroughly discussed by Bolton. As he surmised, ‘this was an artisan-craftsman working population based on the family unit of production’.28 Unfortunately, throughout the rest of the subsidy records, the only occupations that can be positively identified are servant, merchant and merchant’s clerk or factor.29 Merchants and their clerks and factors were taxed at different rates in the 1453 subsidy, and many non-householders were only identified as a servant of another individual, without giving their own name. Between 1440 and 1483, 715 merchants can be identified, with sixty-five merchant’s clerks and twenty-nine factors. 1,291 servants can be positively identified, the majority of whom (1,117) were male servants. As noted above, some alien servants were identified as servants to alien householders in the assessments. In total, 222 alien householders employed 487 alien servants, some having particularly large alien households as a result. Most of these feature in the 1483 assessment, but there are a few earlier examples of smaller alien households. For example, in 1449 the Italian Benedetto Borromei was identified as having two unnamed alien servants.30 He was a significant Milanese and Florentine merchant who was present in London between 1432 and 1449.31 In 1456 John Hasard and Peter Mason were identified as having one unnamed alien servant each.32 The remaining servants were employed in English households, some of which can be identified. For example, Henry Sebbe was assessed in 1444 as a servant of Matthew Philip, a leading goldsmith in Farringdon Within ward.33

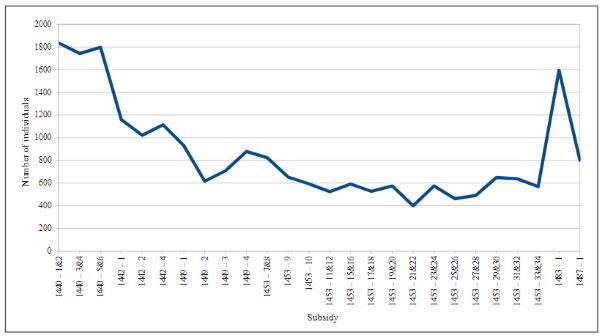

One of the greatest challenges posed by the alien subsidies is identifying the nationalities of London’s resident immigrants, as the details were not recorded by the assessors until 1483. Suggestions can be made regarding origin using an individual’s surname, such as Frenchman/woman (143 individuals), or Dutchman/woman (314 individuals), or Irishman/woman (fifteen individuals), but this is not without issues. For example, a Lewis Scot features in the records, but he has been identified by Helen Bradley as an Italian.34 Yet we do have to start somewhere, and unless there is any evidence to the contrary, it has been assumed that a national toponymic surname correlates to an individual’s nationality.

The largest national group identified is the rather broad ‘Teutonic’ group, identified as such in the 1483 assessment. This is closely followed by the Italians, although, as Bolton noted, in 1483 they were exempt from the subsidy, but were still a sizeable community in London.35 Another similarly large group are the ‘Doche’ and Netherlanders, closely followed by the French.36 Other nationalities include Greeks, Irish, Icelanders, Portuguese, and Danish (Table 7.2). As discussed by Bolton, the 1483 label of ‘Teutonic’ or German was probably used indiscriminately to include ‘Fleming’ as well.37 Including the Flemish group in the Teutonic/German group, the total reaches 1,764 individuals. Specific origins for this group are only given for those recorded in the 1436 oath of fealty, and the group remains non-specific in the remainder of the records.38 Another problematic group is the French. As suggested by Bolton, it is highly likely that their nationality was hidden by their names in the records, and much more research is required on this elusive alien group in London.39

The dominant Teutonic/German/Flemish migrant group brought into England many occupations beyond the somewhat stereotyped Flemish weaver, including cobblers and cordwainers, cappers and hatmakers, goldsmiths, tailors, beerbrewers and beermen, and other highly specialized crafts.40 Other national groups present typical occupations, in particular the Italian merchants, clerks and factors using London as a trading outpost. The Scottish and French residents of London were predominantly servants, although some individuals were in skilled occupations, including tailors, joiners and a surgeon. However, it is still a matter of debate whether the push or pull factor was stronger in encouraging the skilled migrants to England.41

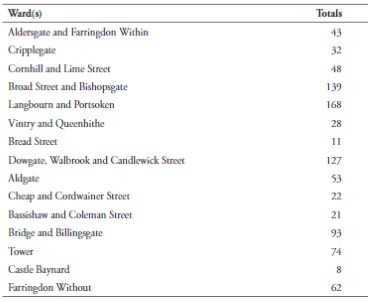

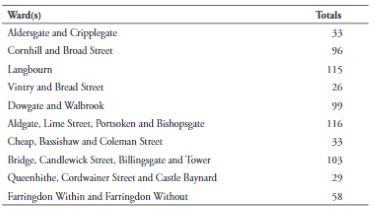

In Bolton’s assessment of the geographical distribution of aliens, his main observation was that it was an uneven spread across the city.42 He identified the most heavily populated wards in the 1441 and 1483 assessments as Tower, Billingsgate, Dowgate, Vintry, Queenhithe, Candlewick Street and Langbourn, and this is consistent with the other subsidy collections, with a few exceptions. Portsoken, Dowgate and Vintry wards were far less populated with immigrants in the early 1440s than in 1483. However, Tower and Langbourn wards were consistently popular locations for immigrants to settle in from the 1440s to 1483. In the 1440s popular wards also included Cripplegate, Broad Street and Farringdon Without, but all three wards had an approximate drop of 50 per cent in their immigrant populations by the time of the 1483 assessments. The alien population drop in Broad Street ward is at first glance surprising, particularly as it peaked in 1443 with 154 identified residents. As a large mercantile and banking centre, it should have remained a draw in 1483. However, the largest national group resident there is Italian, and it served as an enclave for an Italian mercantile community, rather than a wider mixed community.43 So in part the marked decrease in Broad Street ward’s given population can be attributed to the exemption of Italian merchants from the alien subsidy in 1483. While this is only a tentative analysis of the distribution of the aliens in the city, it may be suggested that in the 1440s there was a slightly more even distribution than in 1483, and less tendency to concentrate in the outer ring of wards (Tables 7.3a–c).44

The alien subsidy records and the supporting documents only offer one view of the alien population in London. As the alien subsidies are surveys fixed to one point in time, they only provide a momentary representation of the residents within a given year. As stated by Bolton, ‘account must also be taken of the transients who came to London for a variety of reasons, and stayed only a few weeks or months’.45 There is no question that many immigrants, in particular skilled craftsmen, would have passed through London as the first point of entry to the country, perhaps only staying for a short period, and then moving on to more permanent homes in the rest of England where they could find employment, although definite examples remain elusive. Others would have been sailors on the frequently visiting ships and in London for only a matter of weeks.46 Priests and friars, soldiers, and ambassadors and their representatives would also have had an impact on the size of the immigrant population. There are also those who simply avoided being assessed by making themselves scarce or perhaps seeking royal favour, although, as discussed below, this did not always work in London.

There was certainly a proportion of aliens who regarded London as their permanent home. Some 144 aliens living in London obtained letters of denization between 1406 and 1549, indicating that they considered themselves permanent residents, and expected to be treated as such. However, this was not always enough to convince London’s authorities that some denizened aliens were legitimate and exempt from the alien subsidy. For some, the only answer was to obtain letters of denization and to be accepted into the freedom of the City, although achieving this was no mean feat. This extra secure approach was achieved by the Italian merchant Simon Bochell in the 1360s, but it was rarely realized in the fifteenth century.47 The cost of doing this may have inhibited many.48 For others it was a continuous battle to get their denizen status recognized. One particular individual who suffered from such non-acceptance was Gervase le Vulre, Henry VI’s French secretary. He was a resident of London between 1436 and 1465, but despite his letters of denization and writs to the mayor and aldermen of London, he was persistently assessed for the alien subsidy until 1451.49 Similarly, Joyce Hals, who swore the oath of fealty in 1436, was assessed to pay the tax from 1441. He obtained letters of denization in 1447, but continued to be assessed to pay the subsidy until 1465.50 As suggested by Thrupp, they by no means ended up paying the tax, yet they were still assessed because the London jurors believed denization only legitimized an alien’s right to buy land, and did not grant exemption from taxation. Indeed, some letters of denization specified that the alien was to continue to pay customs as an alien, showing that the non-standardization of such letters meant a degree of confusion to the assessors in London.51 Nevertheless, a few aliens who obtained letters of denization in London were accepted as denizens and left alone. Flory Lambard was assessed to pay the alien subsidy in 1441, but by 1444 he was a denizen and no longer featured in the subsidy assessments.52 Yet those with letters of denization comprise barely one per cent of the 18,000 instances of aliens in London between 1330 and 1550, and are hardly representative of a long-term residential group.

Other long-term and permanent residents can be found in the course of the alien subsidies, many of whom have already been highlighted by Bolton. Most notable is Alexander Effamatos, the Greek goldwiredrawer, a resident between 1441 and 1483, who was assessed in ten collections between 1456 and 1483.53 Tyse Jeweller was identified by Bolton as appearing in the assessments in the 1460s, and he was also assessed in 1457.54 Another long-term resident was Dederick Ketilwood, who was first assessed in 1456.55 He was originally identified as a merchant stranger, being either Hanse, Prussian or Easterling, in 1456, and he was assessed a further four times in London (in 1464, 1465, 1467 and 1469) before moving to Westminster by 1484.56

One of the long-term residents who has been identified consistently throughout the subsidies is Florence Hynk, recorded as a Teutonic embroiderer in 1483, living with his German wife Margaret.57 He is first recorded in 1441, and then again in 1443 as a resident of Broad Street ward.58 While he is not assessed in the 1449 subsidy, he returns again for the 1453 subsidy, and is assessed in 1456, 1457, 1464, 1465 and 1467, before finally being assessed in 1483 when he was still living in Broad Street ward.59 His forty-two year residency is one of the longest to be found using the alien subsidies. There are others who can be traced over a shorter period, such as Guy Asshewell, who was first assessed in 1457.60 He then appears in 1465, 1467 and 1469, and is finally assessed in 1483, where he is identified as Teutonic, a weaver, with a Teutonic wife, Elizabeth, and two Teutonic servants.61 Nicholas Dowland, a Zeelander, swore the oath of fealty in 1436, and then was assessed to pay the tax as a resident of Broad Street ward in 1443, 1449, 1456, 1467 and 1469.62 A Laurence de Costa from Picardy swore the oath of fealty in 1436, and was then assessed to pay the alien subsidy in 1441 and 1444 in Langbourn ward.63 Finally, Tilman Kerseman also appears in the records sporadically between 1436 and 1451.64 This handful of examples illustrates the variety of residents who were certainly not transient and chose to settle in the city. Some were highly skilled, like Hynk, and doubtless found regular employment in London, which encouraged them to settle, some with their families and wider alien households. Long-term residents of other ports and towns can be found. For example, Edward Cattaneo was present in Southampton between 1440 and 1466, heading up that branch of the Cattaneo family’s trade interests in England.65 Derek Keene identified a corveser, William Kneppell, as an alien who was recorded as a long-term resident of Winchester between 1436 and 1453.66 He was assessed as an alien householder in 1440, and again in 1444, 1449 and 1453.67

These select examples show how it is possible to trace certain individuals through the records, but significantly it is only possible for those with distinctive names. There are some particularly unusual names that make it easy to establish the continuity of an individual resident, such as Albright Rosegarden, a resident of Candlewick Street ward, who was assessed to pay the alien subsidy in 1441, 1443, 1449 and 1451.68 However, it is more often the case that names are generic and sweeping assumptions of connections must be avoided, unless there is strong evidence to suggest that two people with names like William Arnoldson were actually the same person, especially when there is a ten-year gap or more between the name appearing in the records. The nature of the London records means that it is not always possible to connect individuals between records, and it is possible that some long-term residents cannot be traced as such.

For every one or two individuals who can be followed through the tax records, another ten or more have only a fleeting appearance, just once or twice at most. The records between 1436 and 1483 for London do tend to support Bolton’s assertion that only 20 per cent of the householders were long-term residents, and that permanency was not the nature of the capital city. The different names given in the assessments for the same ward year on year indicate that there was a steady stream of newly arrived immigrants in London who were eligible for taxation. A small sample survey taken from the assessments for the first collection of the 1440 subsidy concurs with Bolton’s findings for the later subsidies.69 The assessment records householders who had apparently moved between the initial assessment and payment. However, sixty-three could be found in a following assessment, and forty of those could be found in more than two further assessments, suggesting they were at least resident for more than two years in London, and in some cases for at least six years as they were also previously recorded as swearing the oath of fealty in 1436.70 In total, 130 out of the 579 individuals (including wives) recorded in this assessment could be found in further assessments in the 1440s and 1450s. While this is only a very small sample of a vast group of individuals, it does suggest that we can begin to think of London’s immigrants in three categories: short-term and fleeting, being present for less than a year; mid-term, being visibly present for up to ten years; and long-term, living in London for more than ten years.

However, consideration must be taken of the nature of the records and the changes that took place over time. As already indicated, the nationalities and groups that were liable for taxation fell in number over the forty-year period, chipping away at the groups of aliens who could be assessed. Even the zealous assessors in London could not get away with incorrectly assessing those exempt from the tax by law, despite their apparent confusion regarding letters of denization. So, for example, many who were assessed in 1441 were certainly not included the next year, even if they were long-term residents, because a particular national group had been declared exempt.71 There is also the issue of avoidance. Doubtless many immigrants went out of their way to avoid assessment, and certainly many avoided paying the tax when collection was due. There are instances where an individual is noted as a non-payer, having moved or died, only to appear again the next year in the assessment, and to be noted as having paid. Certainly the nature of the administration of the alien subsidies creates many challenges to assessing the make-up of London’s migrant population.

The alien subsidies and the letters of denization or protection are limited in what they can reveal about the popular feeling towards the immigrant population in London, and its fluidity. The attacks on various national groups in London coincided with national political crises and economic downturn, and the alien subsidies were one of various responses to public hostility. Yet they were not the solution, as shown by the attacks on Italian merchants in 1456–7 and the attack on the Steelyard in 1493. As Bolton has also highlighted, from the 1381 Peasants’ Revolt, to the Readeption of Henry VI in 1470, to the Bastard of Fauconberg’s Rising in 1471, political upheaval allowed local and personal violence against London’s resident aliens to take place. Yet this underlying threat to the safety of migrant groups did not prevent many choosing to remain in the city.72

London would always attract incomers – be they Englishmen looking for opportunities in the city, or alien craftsmen or merchants. The latter group would perhaps bring with them their own servants as part of their household, but other alien servants may have come seeking opportunities in the city, perhaps with the hope of moving on quickly. The capital city was certainly an immigration hub, but this did not mean that it was not viewed by a sizeable group as a potential new home. There were opportunities to work and trade, and corners of markets to be exploited. The Greek Alexander Effamatos is a prime example of an expert bringing his craft to a city where the demand for luxury goods was extremely high. So while the numbers of fleeting immigrants cannot be satisfactorily quantified, mid-term and long-term resident immigrants can be pinned down to suggest that for at least some the city was somewhere to settle.

Endnotes

- The Alien Communities of London in the Fifteenth Century: the Subsidy Rolls of 1440 and 1483–4, ed. J. L. Bolton (Stamford, 1998).

- S. L. Thrupp, ‘A survey of the alien population of England in 1440’, Speculum, xxxii (1957), 262–73; S. L. Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London in the fifteenth century’, in Studies in London History Presented to P. E. Jones, ed. A. E. Hollaender and W. Kellaway (1969), pp. 251–72.

- See Bolton, Alien Communities, pp. 38–40 for a summary of anti-alien feelings.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, pp. 8–9.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 3.

- TNA: PRO, E 179.

- Alien wives of alien husbands were also not considered liable for the tax on most occasions.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, pp. 3–4 (Thrupp, ‘Survey’, pp. 262–4, and Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London’, p. 254 for more details).

- Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London’, pp. 256–8.

- Letters of denization began to be issued after 1378. For further discussion of the development and use of letters of denization, see B. Lambert and W. M. Ormrod, ‘Friendly foreigners: international warfare, resident aliens and the early history of denization in England, c.1250–c.1400’, English Historical Review, cxxx (2015), 1–24. Oaths of fealty to the crown were sworn by particular groups of aliens at certain times of crisis. The 1436 oaths of fealty is the most notable, as it followed the breakdown of the Anglo-Burgundian alliance and involved individuals pertaining from the Low Countries. Irish and Welsh residents in England swore an oath of fealty to the crown in 1413.

- CPR 1330–1509; Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, of the Reign of Henry VIII, 1509–1547 (23 vols., 1862–1932).

- Westminster Abbey Muniments (WAM) 12261; TNA: PRO, C 67/72–73; Letters of Denization and Acts of Naturalization for Aliens in England: 1509–1603, ed. W. Page (Lymington, 1893).

- Only 15% of the individuals in the ‘England’s immigrants 1330–1550’ database are from sources other than the alien subsidies.

- These figures include multiple instances of individuals who occur twice or more. No attempt has been made to remove multiple entries, as the data range over time and the repetition is indicative of the long-term presence of many immigrants. For further discussion of multiple entries, see below.

- For Bolton’s study of the suburbs, see Bolton, Alien Communities, ‘Introduction’.

- TNA: PRO, E 359/28, 30, 32, 33.

- Thrupp, ‘Survey’, p. 265.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 8.

- In the city there were 1,743 individuals, of which 243 were married couples, plus an assumption of 486 children (at two per married couple), resulting in an estimated 2,229 individuals. In Middlesex there were 399 individuals, of which approximately 55 were married couples, with an assumption of 110 children, resulting in an estimated 509 individuals. In Southwark, according to Bolton’s figures, there were 631 individuals, of which 84 were married couples with 168 children, totalling 799 individuals.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 25; Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London’, p. 258.

- J. Lutkin, ‘A survey of the resident immigrants in Hampshire and Southampton, 1330–1550’, Hampshire Studies: Proceedings of the Hampshire Field Club & Archaeological Society, lxx (2015), 155–68.

- In London, wives were only taxed in 1483/4, assessed to pay the non-householder rate. Thrupp chose to exclude them from her 1440 alien subsidy figures.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 8.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/235/23, m. 2.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/144/42, m. 24.

- Bolton adds two children per household to the 1483 figures, adding a further 720 to his total (Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 8).

- WAM 12261, m. 19.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, pp. 19–24.

- The City and London company records could provide more detail on occupations pre-1483, but this is beyond the scope of this chapter.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/235/23, m. 10.

- The Views of Hosts of Alien Merchants 1440–1444, ed. H. Bradley (London Record Society, xlvi, 2012), pp. 272–3.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/235/58, m. 1. Hasard was a resident of either Bishopsgate, Portsoken, Aldgate or Lime Street between 1451 and 1457. There is no further information on Peter Mason. As there were several recorded in the subsidy records for London, it is not possible to distinguish one from another.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/144/54, m.12. It is likely that this is Hans, recorded as a ‘Dutchman’, newly sworn into the Goldsmiths’ Company on 9 May 1442 with Matthew Philip (The Wardens’ Accounts and Court Minute Books of the Goldsmiths’ Mistery of London, 1334–1446, ed. L. Jefferson (Woodbridge, 2003), p. 524). For Matthew Philip’s biography, see T. F. Reddaway and L. Walker, The Early History of the Goldsmiths’ Company 1327–1509 (1975), pp. 301–2.

- H. Bradley, ‘The Italian community in London c.1350 to c.1450’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 1992), p. 388; TNA: PRO, E 179/144/64, m. 11.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 6. See also Bradley, ‘Italian community’ and Bradley, Views of Hosts.

- ‘Doche’, like ‘Teutonic’, was another generic term used to describe an individual from the Low Countries or Northern Germany, and was most commonly used in London.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 30. See also p. 6 for a discussion of the Hanse.

- Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London’, p. 259.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, pp. 7–8. Thrupp suggested that the French preferred small towns and villages to London, but more work needs to be conducted to substantiate this (Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London’, p. 260).

- In particular, the flood of Flemish goldsmiths into London and Southwark from 1370 onwards has been discussed in detail in Reddaway and Walker, Goldsmiths, pp. 120–5.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, pp. 32–4. It is still a matter of debate whether migrants left their homeland because a poor situation there, including conflict and economic decline, pushed them to seek a new home, or whether the promise of an economic boom and opportunities for better standards of living pulled them to their new place of residence.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 11. See also J. L. Bolton, ‘La répartition spatiale de la population étrangère à Londres au XVe siècle’, in Les étrangers dans la ville: minorités et espace urbain du bas Moyen Age à l’époque modern, ed. J. Bottin and D. Calabi (Paris, 1999), pp. 425–37. The assessments for the 1440, 1442, 1449 and 1483 subsidies were conducted by individual wards, rather than consolidating the entirety of London. The assessments of 1449 saw wards being assessed together, such as Dowgate, Walbrook and Bridge wards.

- Bradley, ‘Italian community’, pp. 30–1.

- Further analysis of the distribution of immigrants in the city is beyond the scope of this chapter. As identified by Bolton, much further analysis of each ward is required. For an example, see D. Keene, ‘A new study of London before the Great Fire’, Urban History Yearbook (29 vols., Cambridge, 1984), xi. 11–22. For the draw of alien fraternities as a factor in specific London wards, see J. Colson, ‘Alien communities and alien fraternities in later medieval London’, The London Journal, xxxv (2010), 111–43.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 9.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, pp. 9–10, esp. n. 25.

- J. Lutkin, ‘Goldsmiths and the English royal court, 1360–1413’ (unpublished University of London PhD thesis, 2008), p. 355. Bochell’s ‘letter of denization’ was not a true letter of denization, but rather a precursor to the legal status. In his grant, he was quit of 3d of the pound, as he had long stayed in London with a permanent house (CPR1361–4, p. 42).

- Reddaway and Walker, Goldsmiths, p. 172.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/144/42, m. 15, /52, m. 3, /57, /64, m. 4, E 179/235/58, m. 1. In the final record he is named as Master Gervase Urle; Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London’, p. 254; for a fuller but incomplete biography, see J. Otway-Ruthven, The King’s Secretary and the Signet Office in the XV Century (1939), pp. 94–103.

- CPR 1429–36, p. 552, CPR 1446–52, p. 53; TNA: PRO, E 179/236/85, E 179/235/23, m. 2, E 179/144/64, m. 8, E 179/236/74, E 179/144/72, E 179/144/69, E 179/236/96, m. 2. It is possible to consider that there were two Joyce Hals, perhaps father and son, particularly as he is noted to have deceased in the subsidy records dated 1441. However, these notes are regularly erroneous, and it is more likely that this was one individual.

- Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London’, p. 255.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/144/73, rot. 1, m. 2; CPR 1441–6, p. 207.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 26. See also J. Harris, ‘Two Byzantine craftsmen in fifteenth-century London’, Journal of Medieval History, xxi (1995), 387–403. His brother Andronicus was also a long-term resident, although he died ten years before the 1483 assessment.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 26. TNA E 179/236/74, E 179/144/72, E 179/144/68, E 179/144/69, E 179/236, m. 2, E 179/144/70, E 179/236/107, m. 2, E 179/144/67. The additional records from 1457 make Bolton’s suggestion that he could be Tyse Soler, jeweller, named as one of the executors of John van Ursell, a goldsmith, in 1457, all the more likely.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/235/58, m. 1; Bolton, Alien Communities, p. 11 n. 29.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/144/69; E 179/236/96, m. 2; E 179/236/107, m. 2; E 179/144/67; E 179/141/94, m. 3.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/242/25, m. 11.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/241/327 pt. 2, rot. 1; E 179/144/53, m. 15.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/144/50, m. 10; E 179/235/58, m. 1; E 179/144/68, 69, 72; E 179/236/96, m. 2; E 179/236/107, m. 2.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/144/72 etc.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/236/74; E 179/236/96, m. 2; E 179/144/70; E 179/236/107, m. 2; E 179/144/67; E 179/242/24. His servants were Lambert van Lyngdon and Thomas Symondson.

- CPR 1429–36, p. 577; TNA: PRO, E 179/144/53, m. 15; E 179/144/50, m. 10; E 179/235/23, m. 8; E 179/235/58, m. 1; E 179/236/107, m. 2; E 179/144/67.

- CPR1429–36, p. 558; TNA: PRO, E 179/144/73; E 179/144/54, m. 23.

- CPR 1429–36, p. 549; TNA: PRO, E 179/144/50, m. 23; E 179/235/23, m. 9; E 179/144/64, m. 5. He lived in London with his unnamed wife and his son, John, the latter of whom was also taxed as an alien.

- A. A. Ruddock, Italian Merchants and Shipping in Southampton, 1270–1600 (Southampton, 1951), pp. 107, 110, 124, 128, 216; TNA: PRO, E 179/176/585, rot. 2d, E 179/173/116, E 179/173/136, E 179/173/139, E 179/173/137, m. 1, E 179/173/133, m. 1, E 179/173/134, m. 1, E 179/173/132, m. 1.

- D. Keene, Survey of Medieval Winchester (Oxford, 1985), p. 383.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/176/585, rot. 7; E 179/364/18, m. 5; E 179/270/32 part 2, m. 1; E 179/173/138.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/144/42, m. 11; E 179/144/53, m. 4; E 179/144/50, m. 18; E 179/144/52, m. 23; E 179/235/23, m. 9; E 179/144/64, m. 11.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/144/73.

- TNA: PRO, E 179/144/42.

- Although, as Thrupp noted, not all jurors honoured the exemptions, and some Irish, Welsh and French individuals were still included in later assessments. Thrupp, ‘Aliens in and around London’, p. 254.

- Bolton, Alien Communities, pp. 38–9.

Chapter 7 (137-155) from Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton, edited by Martin Allen and Matthew Davies (Institute of Historical Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 06.30.2016), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons