Demonic possession had physical and mental signs, but it was not a physical or biological fact. Rather, it was a socially constructed phenomenon.

By Dr. Sari Katajal-Peltomaa

Senior Research Fellow

Tampere University

Introduction

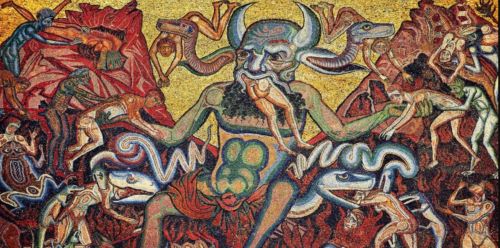

In late medieval culture demonic possession was considered to be one of the reasons behind mental disturbances and deviant behaviour. It overlapped with, but was not equivalent to raving madness, furia.2 Theological, physical and social reasoning intermingled when a person was labelled as possessed by a malign spirit. Theological context was essential since the Devil and demons were part of the spiritual realm, and as such they and their powers were created by God and accordingly categorized and explained by theologians.3

Demons could be seen to be behind various illnesses and in medical treatises exorcism rituals were occasionally recommended as a cure for lunacy and epilepsy.4 Furthermore, in medical and theological treatises a disease called incubus could mean either a sexual demon enticing to the sin of lust, a phantasma creating a sense of strangulation, or an actual disease with symptoms that included a sense of being strangled and inability to move. The physiological explanations for the disease vary, including a superabundance of black bile which could be remedied by balancing the diet, and a disease of the head linked with epilepsy, apoplexy and mania.5

Whether melancholy could be caused by demons was a question posed throughout the Middle Ages. Physicians, who were more eager than theologians to offer naturalistic explanations for supposedly supernatural events, usually argued that if melancholy was caused by evil spirits, they caused an imbalanced complexion of humours within the body.6 A disease called uterine suffocation, hysteria (from the Greek word for womb, hystera) also resembled demonic possession, in that it could cause mental confusion, grinding of the teeth and convulsive contractions.7

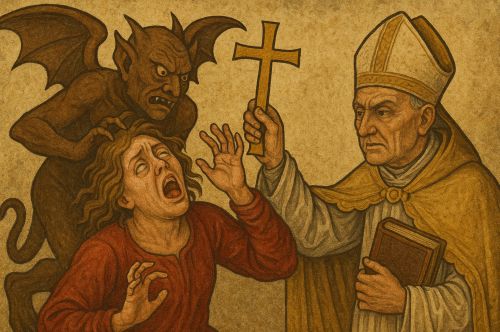

Similar symptoms could indicate demonic possession or other mental disturbance, yet there were some signs that were more typical of demoniacs: abnormal powers, convulsions, blaspheming of the saints and God, and abhorrence of sacred objects, as well as aggression against themselves and close ones. These symptoms or performances were crossing the boundaries of religion, health and proper conduct. Demonic possession was an overarching position, since the moral, physical and social state of a demoniac was affected, but it could also have legal consequences because of its close links to madness.8

Spirit possession has recently been studied by medievalists, but the phenomenon has mainly been approached from the theological perspective. Thus discernment of female mystics’ source of inspiration – whether they were possessed by a divine or a malign spirit – has attracted a keen interest.9 On the other hand, demonic possession as physical distraction10 or as deviant behaviour and rupture in the ideal social order has received less attention.11

The aim of this chapter is to analyse how different explanations and deviations of various categories, spiritual, physiological and social, intermingled in cases of demonic possession and delivery miracles in the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century canonization processes. What kinds of explanations were given as reasons for possession by both clergy and laity; what kind of features indicated delivery? First, hazardous food and drink and perilous places and activities as explanations for affliction are analysed; then concrete signs of the exit of a malevolent spirit are scrutinized. The geographical focus of the chapter is on northern and central Italy, since many detailed cases can be found there. However, for comparative purposes cases from other parts of Europe are also analysed.

Demonic Possession in Canonization Processes

In later medieval canonization processes, inquiries into a saint’s life, merits and miracles, demonic possession was analysed from multiple perspectives, which range from the theological ponderings of clerics to the more mundane explanations given by the laity. Canonization was a papal privilege, but before official proclamation of a candidate’s sanctity an official inquiry had to be held. Papal commissioners interrogated sworn witnesses who had personally experienced or witnessed a miraculous recovery, in this case a delivery from spirit possession.12 Miraculous exorcisms and deliveries from demonic possession had biblical prototypes; the biblical miracles – resurrection of the dead and recoveries of the blind and lame – were significant in evaluating a candidate’s sanctity. Exorcism miracles are not, however, among the most typical cases recorded in the canonization processes.13 Usually only a couple of cases can be found in each hearing.

Canonization hearings were a form of judicial process, an inquisitio: papal officials had the duty to pursue the cases, a reputation for sanctity among the public was a prerequisite for opening a process and the devotees, before being summoned to give witness, had no judicial standing in the inquiry. Respectable people were chosen to give their testimony.14 The questionnaire of the com-missioners dictated which themes were brought up, but at the same time wit-nesses pondered which details to mention and which to leave unsaid. For the commissioners, the most important thing was to find reliable information on alleged miracles, while the witnesses had also personal interests in their testimonies.

In addition, the work of notaries affected the final records; their task was to translate the vernacular oral testimony of the witnesses in order to produce the written Latin deposition. The notaries put the depositions in formam publicam and it was they who guaranteed the judicial reliability of the process. They may also have moulded the testimonies according to certain patterns and standardized the depositions to some extent while writing them down.15

Canonization processes were judicial records, but they were also part of the hagiographic genre. Typical elements of a miracle narration, such as the desperate situation before the cure, may have shaped the way the witnesses gave meaning to their personal experiences and moulded their narration. Both the act of interrogation and patterns of genre affected the chosen rhetoric of the witnesses.

Despite the above-mentioned reservations, canonization processes give a multi-faceted image of demonic possession. Since the definition of the state of affairs was an important part of the evaluation of a miracle, the symptoms were usually described and recorded with care. The signs of delivery were crucial evidence of a proper miracle and can regularly be found in the depositions.

Eat Your Greens! – But only with Care

A well-known example of the rationale of demonic possession was given by Gregory the Great in his Dialogues. Later, in the thirteenth century, this exemplum was re-told by Jacques de Vitry. The incident took place when a hungry nun devoured a lettuce without making the sign of the cross – and swallowed a demon in the process. Once exorcised, the demon complained: “What did I do? Why are you blaming me? I was just sitting on a lettuce when she ate me without crossing herself first.”16

This was probably not a warning against gluttony, gula, since, after all, a lettuce was a rather modest meal. Nonetheless, it was a caveat for deviant behaviour: pious conduct included control of bodily needs as well as proper signs and rituals, like crossing oneself before eating. This kind of reasoning was typical of the didactic stories, but similar logic can also be found in hagiographic material. Occasionally, an unlicensed meal could lead to spirit possession as a punishment. For example, a Dominican friar was possessed when he had eaten meat reserved for sick friars without a license – and without the sign of the cross. Similarly, another friar was possessed after drinking wine sine licencia et sine signo crucis. In both cases the demon argued that he was tormenting them for their actions, vexo eum quia meruit, stressing the educative aspect of the tale; the hagiographic part was emphasized by the exorcism effected by Saint Dominic in both cases.17

Demons were thought to dwell in the body, literally, amidst the entrails and filth. Only a divine spirit could enter a human soul.18 Thus, the souls of the demoniacs remained blameless.19 Nevertheless, an in-dwelling demon could fool the senses and affect demoniacs’ behaviour, which explained the symptoms. In the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century canonization processes the victims are typically described as possessus/a, obsessus/a, raptus/a or invasatus/a by demons; they were “besieged” or invaded, possibly by force.20

Physically, demonic possession was literally to have a demon inside one’s body. This possessing spirit was occasionally visible to the bystanders in an abnormal swelling of a body.21 As a physical phenomenon, demonic possession was also closely linked to the sex of the victim, as women’s bodies were considered to be more open and vulnerable and thus more exposed to spirit possession.22

Demons and malign spirits were spiritual creatures, but they could nevertheless be eaten or drunk, and so enter the body. Demonic possession was a spiritual state, but it was also a physical phenomenon, since demons actually entered a person’s body and exited it after a successful exorcism. The canonization process of Giovanni Bono (ad 1254) further illuminates this feature: when Benghipace was outside the city of Mantua she drank from a well. Immediately, she felt sad and burdened, nearly out of her mind. She returned home con-fused, as she described the situation. In the register of miracles the case is categorized more clearly: Satan had entered into her while she drank water at the well.23 Next day an attempt was made to lead her to a nearby church but she resisted fiercely. The day after that she was taken to the shrine of Giovanni Bono by three men. At the shrine she sensed something moving upward from her guts to her mouth. Once she had spat it out, she was delivered.24

Benghipace does not declare herself as possessed by a demon, but all the other witnesses, who were women neighbours, do use this definition. Her state also interested the commissioners, who asked the witnesses how they knew that she was possessed. The answer given by many was that she had all the typical signs of a demoniac, including an abhorrence of sacred things.25 Only Benghipace herself gives any reason for her possession, mentioning the well and the water. Similarly, she is the only one to mention the sign of the delivery, the thing she threw up, apparently the demon itself. Other witnesses based their justification on other criteria, namely disorderly behaviour. Conversely, they considered Benghipace cured once she began to act calmly and rationally again. Interestingly, all the details – the Devil drunk with the water, the thing vomited up and the subsequent cure – were mentioned in the register of miracles recorded by the local clerics before the official canonization hearing. For them these elements were important in the validation of a miracle, evidence that Benghipace had been truly possessed but then cured by the powers of Giovanni Bono.

Although the witnesses in Benghipace’s case gave little support to her tale of the water polluted by demons, there are other examples of water being a medium for possession. One example is of a man called Petrus, who drank from a spring while he was on a pilgrimage to Puglia and consumed demons with the water.26

Water was an important, and usually positive, ingredient in the Christian faith. Holy Water was important for several rituals, as it was used in purifying souls and spaces. It was an essential element in the sacrament of baptism, which literally washed away the original sin of Christians. Water in the form of tears was a sign of contrition for evil deeds, but tears could also signify baptism and rebirth. Crying for one’s sins was considered to purify the soul, and thus tears could be considered as a divine grace.27 Many wells and springs were connected with saints and their cults. Water from the shrine was one of the most typical secondary relics.28 But water was an ambiguous element and could also, apparently, be poisonous and carry evil elements,29 as the above examples demonstrate.

Not even water from a sacred place was free from danger, since Palmeria was possessed after drinking water from a well in a churchyard in Viterbo. However, in this case she may also be considered a victim of malediction, a woman who wanted to drink before her had told her that she would drink thousands of demons in the water – and so she did. Palmeria was pregnant and gave birth to a dead baby boy within eight days. Only after giving birth did the symptoms begin: she hit her husband, shouted, and could not listen to the words of the Holy Gospel.30

Her husband, Blasius, was another witness to the case, and he agrees with his wife on the malediction. However, he implies that there may also have been other reasons for the affliction. First of all, Palmeria had gone to the consecration of this church against his will. Blasius’s aim seems to have been first and foremost to exculpate himself from responsibility for this tragedy. After all, it was his duty as a husband to guard his wife from physical and especially from moral dangers. According to him, the maledicting woman was a prostitute, meretrix. The malediction seems to have been an essential element in this case, as it was cited in other versions of this miracle in other compilations, not only in the deposition of Palmeria.31 Furthermore, Blasius argued that Palmeria made the sign of the cross after her sip.32 Thus her actions were not blameworthy and she was an innocent victim.

For medieval societies, as for societies of any given period, questions of water supply were crucial. In Italian cities many wealthier households had their own cistern or well in their yard for security reasons, and there were also many common wells shared by a small number of households. The use of water accentuated social hierarchies and they made social relations more complex. Tensions emerged, especially in medieval Italy, where rapid urban growth put pressure on the traditional means of water supply.33 In Benghipace’s case the well was in an unfamiliar place for her, as she was outside her town of residence for unknown reasons. In Palmeria’s case the well was in common use, since it was in a churchyard. However, social hierarchies are manifest, especially in Palmeria’s case, in which the other woman apparently considered her-self worthy of drinking first, but Palmeria disagreed.

These cases of demonic possession may also reflect general fears for the purity of water. Physical and mental poisons could be found in it. Concerns for murky, smelly and unhealthy water were uttered already in the early Middle Ages and the connection between poor water and poor health was known. Occasionally, turbid and smelling water was seen as a divine punishment.34 Dietary requirements were important elements in sickness and in health and water was used as a healing ingredient: it was a major component in many medicines mixed with different herbs, powders and liquids and the taking of baths was used as a healing method.35 Safety and purity of water was a crucial concern for medieval people, evidence of which can also be seen in the accusations of poisoning wells. Such claims are known from different periods and they were often caused by social criteria of otherness and purity.36 Disputes over the right to use water could lead to conflict, sometimes explained as caused by demons, but in addition to social tensions the aforementioned cases may also reflect fears for the physical dangers that may lie within the water.

Between Nature and Civilization

Water could instigate quarrels and negotiations over authority within the domestic sphere too. Fetching water was a laborious task and it was often left to the least prestigious members of the household.37 Guerula and Joanna were fetching water from a well near their homes, most likely for the whole house-hold, when they fell victim to a demonic assault. A demon invaded Guerula on her way to the well in Mantua.38 In Siena, Joanna was also seized by a demon while fetching water, and as a consequence she sat by the well laughing and spitting in the faces of passers-by.39

In clerical rhetoric the virtue of women was closely connected with proper spaces: an honourable woman did not stray too far from home, as dangers, both physical and moral, were abundant in the public sphere. Obviously women were not confined to their homes, since many of their daily tasks, like fetching water from the town’s well, required use of the public space. Gendered allocation of space was linked with ideas of the moral fragility of women, who were seen to be closer to the Devil in clerical rhetoric. Women were both physically and mentally the weaker vessel and more prone to sin.40 However, demonic possession cannot be labelled an exclusively feminine phenomenon, since adult men too could get possessed, and also at the wells.41

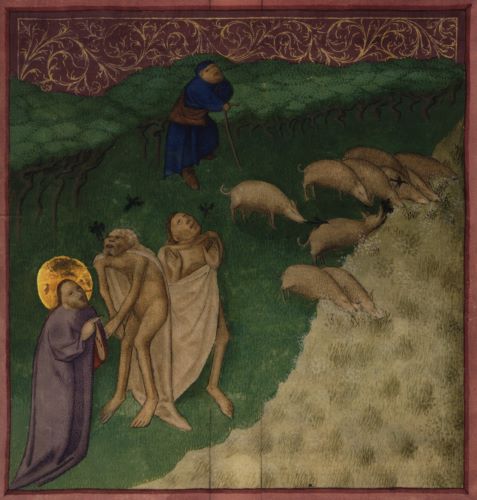

Possibly, in the aforementioned cases the reason was not moral as such, but religious. In the medieval imagination, water, and especially wells as openings in the ground descending from the surface to hidden and mysterious depths, could be inhabited by demons and malevolent clandestine creatures. Demons seem frequently to have dwelt around or inside wells.42 A vivid narration of wells as the residence of demons can also be found in the canonization process of Saint Birgitta of Sweden (ad 1374–1380). Petrus Gedde, a boy of ten, had been possessed by a demon for several years when he sought a cure at the shrine of Saint Birgitta in Vadstena, Sweden. The tormenting spirit made him prostrate on the ground for several days, but when it exited, it came out of the mouth of the boy in the form of a huge snake, after which it transformed itself into a goat and disappeared into the well of the monastery.43

A well, it seems, was a suitable place for demons to go. As if to emphasize this, when Antonius Tronto from Avignon saw a multitude of them trying to capture him, he shouted: “To the well these demons, projiciatis in puteos daemones istos.”44 In Antonius’s case the reason for the affliction may also have been a beverage he consumed, which was unsuitable in either a physical or a social sense, or both: he had been ill and resorted to medicine and potions ordered by a Jewish doctor, and lost his mind after taking them.

Nancy Caciola claims that possession in a liminal space is typical of folk beliefs. Boundaries between land and water, and especially forests, were particularly dangerous. Malevolent spirits inhabited these regions between inhabited areas, where culture and civilization was to be found, and nature.45 These claims can only be seen partially in the cases of demonic possession in the canonization processes, as many victims were possessed in their homes, even in their own beds. However, some of the cases are connected with liminal spaces: water was, of course, part of nature, but wells were also cultural constructions and part of society. Water was essential, but also potentially dangerous in the theological and especially in a physical sense, which may have increased anxiety about it. Furthermore, wells could be seen as liminal space between the inhabited commune and the depths of the earth. Yet, the majority of the conflicts may have evolved around social relationships: for instance, who had the right to use the water from a well, or who was obliged to fund its maintenance. All these elements made water as such and wells in particular potential mediums for social tensions, which may have been resolved in interpreting misbehaviour as demonic possession caused by drinking the water without sufficient care.

The interconnection of improper conduct and dangerous spaces is also often emphasised in exempla. In these didactic tales containing a moral lesson, parties, dances, and meetings were seen as particularly dangerous. Above all, the combination of dancing and singing was condemned, women participating in the dances being considered as especially immoral.46 In the didactic exempla, participating in chorea often led to peril, death, and damnation. Dancing was seen as a sin and as an activity clearly connected with the Devil. Demons enjoyed seeing people dancing and sometimes led the party, and occasionally those dancing in the dark forests were witches with demons. Dancers were like a cow with a bell: the sound informed the Devil of their whereabouts.47

This mode of thought was apparently internalized by the medieval laity, as well as the clergy, since such explanations can be found in the canonization processes and miracle collections. For example, in the canonization process of Saint Birgitta we encounter a miraculous delivery of Katherina, a citizen of the city of Örebro. She became possessed after taking part in dances and leading chorea during Lent.48 Similarly, in Siena, Ceccha became possessed while dancing at a wedding and playing an instrument which gave her great joy. Her relative Dinus de Rosia guessed that her dissolute behaviour had caused this.49 When Sienese Bonnannus de Ficeclo went with a group of people to a forest to fetch wood, some of the group started to sing and speak foolishly, even immodestly, and as a result a malign spirit gained power over a girl who was fiercely possessed. First she started to stutter and then she lost her speech completely, after which she tried to drown herself. Her face was pale and cold like death and her throat and stomach were swollen.50 The reason for her possession may have been moral transgression, yet the signs were physical and mental.

The case of Katherina was recorded by local clerics in an additional hearing and the cases of Ceccha and the unnamed girl were recorded in the miracles of the Blessed Ambrosius of Siena. Only one witness was interrogated and the hearing at the shrine is unlikely to have been as judicially accurate as the sworn testimonies in actual canonization hearings, so the recording clerics may have had more opportunity to modify these narrations and include didactic elements in them.

However, the laity acknowledged some moral deviance as direct motivation for demonic possession. Punishing miracles are occasionally linked with infestation by malign spirits. A vengeful saint could command demons to possess an unbelieving and disrespectful person.51 On the other hand, moral transgressions are rather rarely blamed for possession and cases of demonic possession often lacked any reason; after all, demons were malevolent creatures that had power over nature and humans, and they could possess an innocent victim without any apparent reason or personal culpability. Often, demonic possession seems to have been an unexpected tragedy that did not need to have a clear and simple reason behind it. Apparently the same logic could also work the other way around: when no reason could be given for an unknown affliction and improper behaviour, it was labelled as caused by demons.

The Blackest of Things

In a search for a cure, the possessed were taken to a shrine of a local intercessor, where they were delivered. Rituals of exorcism could take place on the spot, but in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries the delivery was typically by divine grace, caused to happen by the intercession of a saint. In the fifteenth century, rituals of exorcism performed by the clergy became more important.52 The signs of delivery were often accurately recorded, since they were crucial for all the participants. If no clear physical signs were manifest, they were expressed in words. For example, the aforementioned unnamed girl, once the tormenting spirit had left her, called to Bonnannus de Ficeclo and said “Don’t you see the blackest of things, nonne videtis nigerrimum?” arguing that the demon had visibly left her body. In the medieval imagination black animals and other black things, even black men, were typical incorporated forms of demons, since blackness, sin, death and damnation were linked.53 As an example, in the case of Emessendis, a daughter of Stephanus Mirati, the witnesses testified that black smoke exited the mouth of the girl when she was cured.54

The signs of delivery also interested the commissioners. For example, the aforementioned Palmeria was asked if she felt anything when the demons left her. She replied that she was so alienated by the demons that she did not feel it.55 A regained clear state of mind was one piece of evidence for miraculous recovery of the delivered demoniac, but other proofs were required too. Quite often such proofs were detailed meticulously, a typical symptom mentioned by the eye-witnesses being vomiting, often of black blood or other black material. For example, the above-mentioned Benghipace was cured at the shrine of Giovanni Bono, when she felt something coming up into her throat and exiting her mouth. Similarly, in Piacenza at the shrine of Saint Raimundo, Berta Natona was cleansed, purgata est, by crying, whimpering and vomiting blood.56 Vomiting black blood, coals and other black items were considered a sign that demons had been present and concrete proof of successful delivery.57

The importance of these elements is clearly visible in a case recorded in the canonization process of Saint Francesca Romana in the middle of the fifteenth century. A foreigner, a Hungarian according to the testimonies, was possessed by a demon and taken to the shrine of Saint Francesca in Rome. While close to the shrine, he vomited three coals and was cured. Bystanders were astonished at the miracle and the detail of the coals was mentioned by all the witnesses.58

In the cases of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries these elements were considered genuine signs of demonic possession and subsequent delivery. They were concrete proofs and their authenticity was not questioned. Later, however, the approach changed: Johannes Weyer, a sixteenth-century physician and demonologist, claimed that these vomited items were not demons, nor had they ever been inside the stomach. They may have been devilish delusions, but not what the onlookers thought. Demons may have enticed the possessed to feign such an event, but these items as such were not of demonic origin.59 Nevertheless, in the later Middle Ages, the delivery from a demonic possession was often a real and physical phenomenon, while mental disorder caused by demons was believed to be cured when the possessing spirit physically exited the victim. In the medieval visual evidence the delivery from spirit possession is typically a very concrete phenomenon, in which a black sub-stance or item often exits from the mouth of a victim, as is exemplified in the chapter of Gerhard Jaritz in this collection.

Conclusions

Demonic possession had physical and mental signs, but it was not a physical or biological fact. Rather, it was a socially constructed phenomenon, and the symptoms needed to be negotiated and discussed before a classification. For the definitions of the status of a demoniac, testimony of family and general fama were considered a sufficient proof for categorization – no expert wit-nesses were required, but consensus among the community was enough.60 Spirit possession was a mental state, a disorder which also affected the social position and physical appearance of the victim. It was closely linked to mental disability. The victim was out of his or her mind, acting irrationally and often violently. The symptoms were usually meticulously described. They were, of course, important details validating the state of the victim, but their social consequences, like unrest, improper behaviour and damaged goods, seem to have been the features that interested lay witnesses most.

Spirit possession as a mental confusion led to social disorder but originated from physical facts, namely, that an unclean spirit was thought to dwell inside the victim’s body. As a consequence, demonic possession could be connected to other physical disabilities, like raving madness, melancholy, epilepsy and uterine suffocation in the medical and theological treatises of the era, although pondering of this sort is usually absent from the medieval canonization processes and other hagiographic material. Medical theories cannot be found in the records of canonization hearings and doctors rarely appear as witnesses in cases of demonic possession. However, the physical nature of the phenomenon was acknowledged: sometimes an ingested demon manifested itself in the swelling of the body and the reason behind a spirit possession may have been improper food or beverage. Examples of swelling of the body as a sign of possession can be found in both northern and southern Europe.

Unsurprisingly, spirit possession was closely linked with moral states as well. Even if the victims were deemed innocent in the medieval mind, condemnations of moral deviance can be found in material with didactic over-tones in northern as well as in southern Europe, whereas in the depositions of the laity such explanations are rare. Demonic possession was commonly seen as an unexpected tragedy, the possessed were seen as innocent victims and there was no strong urge to find a reason or a person to blame. However, demonic possession was undoubtedly a social stigma, like any deviant behaviour. Therefore, the victims themselves occasionally tried to find an excuse or reason outside themselves for their affliction, such as drinking polluted water: after all, who could be blamed for having a sip of water?

Demons seem to have been accidentally ingested by drinking, particularly in Italian urban contexts. This undoubtedly reflects the social tensions connected to water supply in this region. In less urbanized areas water supply was not necessarily such a conflict-prone issue, but wells still seem to have been typical dwelling places for malign spirits in other parts of Europe.

Since the clergy generally agreed on the innocence of the victim, they were willing to record cases where demons were accidentally ingested. Simultaneously, such cases were a caveat and emphasized the need for penance and repentance, for demons lurked everywhere. Furthermore, cases of demonic possession underlined the cosmological hierarchy, offering evidence of the rule over demons exercised by heavenly intercessors.

The reason behind the affliction may have remained obscure, but it was important to determine the signs of delivery: the victim wanted to underline the recovery to enable his or her integration back into the community, other witnesses wanted to be certain that the disturbance was over and the commi-sioners wanted to verify the authenticity of the miracle. Therefore, genuine proofs of the exit of a demon, like vomited black items, blood and coals were often recorded meticulously.

In sum, demonic possession was a mental disturbance which showed physical signs and caused social turmoil. Nevertheless, the victims did not find themselves in a permanent marginal position, as they were not usually blamed for moral deviance and the physical and mental signs disappeared after the miraculous delivery. The remedy for this mental disorder was essentially devotional: saints’ intercessory powers chased away invading spirits and restored proper order, in a mental, physical and social sense.

Endnotes

- I am grateful to the projects of the Academy of Finland “Medieval States of Welfare: Mental Wellbeing in European culture c. 1100–1450” and “Gender and Demonic Possession in Later Medieval Europe” for funding the writing of this chapter.

- Demonic possession and furious insanity had many similar symptoms and were not easily separated from each other. Ronald Finucane, Miracles and Pilgrims. Popular Beliefs in Medieval England (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995), 107. They could have been categorized under one heading in miracle collections, see “De demoniacis invasacis seu evanitis et adr-abicis liberatis.” BAV MS Vat. Lat. 4027 ff. 27r. Occasionally a distinction was made, but the vocabulary may have been chosen by the commissioners or notaries, rather than by the wit-nesses in the canonization processes. Cf. BAV MS Vat. Lat. 4015 f. 212v–216v; BAV MS Vat. Lat. 4025 f. 99r; BAV MS Vat. Lat. 4019 ff. 62r–63v; 75r–76v; 78v–79r.

- The Fourth Lateran council in 1215 was a major turning point: Lucifer was defined as a fallen angel who was cast out of heaven after committing the sin of pride. Demons, as spiritual creatures, possessed knowledge of spiritual things. J. Alberigo et al., eds., “Concilium Lateranense IV,” in Conciliorum Oecumenicorum decreta (Freiburg: Herder, 1962), cons 1. On demons and demonic possession in the Biblical tradition, see Johannes Dillinger, “Beelzebulstreitigkeiten. Besessenheit in der Biblen,” in Dämonische Besessenheit. Zur Interpretation eines kulturhistorischen Phänomens, ed. Hans de Waardt et al. (Bielefeld: Verlag für Regionalgeschichte, 2005), 37–62.

- Lea T. Olsan, “Charms and Prayers in Medieval Medical Theory and Practice,” Social History of Medicine 16: 3 (2003): 343–366. Uses of incantations and amulets can frequently be found in medical treatises. On Anglo-Saxon examples, see Audrey L. Meaney, “Extra-Medical Elements in Anglo-Saxon Medicine,” Social History of Medicine 24: 1 (2011): 41–56; on comparison between thirteenth century pastoral manuals and medical texts, see Catherine Rider, “Medical Magic and the Church in Thirteenth-Century England,” Social History of Medicine 24: 1 (2011): 92–107.

- Medieval authors disagreed on whether an incubus was only a dream phenomenon or a real attacker. Maaike van der Lugt, “The Incubus in Scholastic Debate: Medicine, Theology and Popular Belief,” in Religion and Medicine in the Middle Ages, ed. Peter Biller and Joseph Ziegler York Studies in Medieval Theology III (York: York Medieval Press, 2001), 175–200. Cf. Rainer Jehl, “Melancholie und Besessenheit in gelehrten Diskurs des Mittelalters,” in Dämonische Besessenheit, 63–71.

- Joseph Ziegler, Medicine and Religion, c. 1300: the Case of Arnau de Vilanova (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 8, 173–175; also Roger Kenneth French, Canonical Medicine: Gentile da Foligno and Scholasticism (Leiden: Brill, 2001), 64. On melancholy and humoral theory, see the chapter of Timo Joutsivuo, and on practical advice for contentamento and mental well-being, see Iona McCleery’s chapter. However, physicians drawing from earlier Greek or Arabic tradition were more willing to accept demonic influence as a reason for affliction: see Catherine Rider’s chapter in this collection.

- Danielle Jacquart and Claude Thomasset, Sexuality and Medicine in the Middle Ages, trans. Matthew Adamson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 173–177. On uterine suffocation and other women’s diseases, see Monica H. Green, Making Women’s Medicine Masculine. The Rise of Male Authority in Pre-Modern Gynaecology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- On legal restrictions on the mentally ill, see Wendy J. Turner, ed., Madness in Medieval Law and Custom (Leiden: Brill, 2010).

- The most important contributions to the study of demonic possession during the Middle Ages are Nancy Caciola, Discerning Spirits. Divine and Demonic Possession in the Middle Ages (Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 2003), and Dyan Elliott, Proving Woman. Female Spirituality and Inquisitional Culture in the Later Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004). Taking a similar approach, see also Renate Blumenfeld-Kosinski, “The Strange Case of Ermine de Reims (c. 1347–1396): a Medieval Woman between Demons and Saints,” Speculum 85 (2010): 321–356; Moshe Sluhovski, “The Devil in the Convent,” The American Historical Review 107: 5 (2002): 1378–1411; Barbara Newman, “Possessed by the Spirit: Devout Women, Demoniacs, and the Apostolic Life in the Thirteenth Century,” Speculum 73 (1998): 733–770; Richard Kieckhefer, “The Holy and the Unholy: Sainthood, Witchcraft and Magic in Late Medieval Europe,” in Christendom and Its Discontents. Exclusion, Persecution, and Rebellion, 1000–1500, ed. Scott L. Waugh and Peter D. Diehl (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 310–337, and Peter Dinzelbacher, Heilige oder Hexen. Schicksale auffälliger Frauen (Düsseldorf: Patmos, 1995). For the Early Modern Era, see Sarah Ferber, Demonic Possession and Exorcism in Early Modern France (London and New York: Routledge, 2004) and Sarah Ferber, “Possession and the Sexes,” in Witchcraft and Masculinities in Early Modern Europe, ed. Alison Rowlands (Houndsmills: Palgrave McMillan, 2009), 214–238. For the evolution of this phenomenon in Christian tradition from Antiquity to the present day, see Brian P. Levack, The Devil Within. Possession & Exorcism in the Christian West (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2013).

- On demonic possession and physiology, see Nancy Caciola, “Breath, Body, Guts: The Body and Spirits in the Middle Ages,” in Communicating with the Spirits, ed. Gábor Klaniczay and Éva Pocs (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2005), 21–39 and Dyan Elliott, “The Physiology of Rapture and Female Spirituality,” in Medieval Theology and the Natural Body, ed. Peter Biller & A.J. Minnis (Bury St Edmunds: York Medieval Press, 1997), 141–173.

- On demonic possession and deviant behaviour, Cam Grey, “Demoniacs, Dissent and Disempowerment in the Late Roman West: Some Case Studies from the Hagiographical Literature,” Journal of Early Christian Studies 13: 1 (2005): 39–69 and Leigh Ann Craigh, Wandering Women and Holy Matrons. Women as Pilgrims in the Later Middle Ages (Leiden: Brill, 2009), 180–216, and Sari Katajala-Peltomaa, “Socialization Gone Astray? Children and Demonic Possession in the Later Middle Ages,” in The Dark Side of Childhood in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, ed. Katariina Mustakallio and Christian Laes (Oxford: Oxbow, 2011), 95–112. On demonic possession, laity and everyday life, see Michael Goodich, “Battling the Devil in Rural Europe: Late Medieval Miracle Collection,” La chris-tianisation des campagnes. Actes du colloque de C.I.H.E.C. (25–27 août 1994) Tom I, ed. J.-P. Massaut & M.-E. Henneau (Institut historique belge de Rome, bibliothèque: Bruxelles, 1996), 139–152, and Laura Ackerman Smoller, “A Case of Demonic Possession in Fifteenth-Century Brittany: Perrin Hervé and the Nascent Cult of Vincent Ferrer,” in Voices from the Bench. The Narratives of Lesser Folk in Medieval Trials, ed. Michael Goodich (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006), 149–176.

- On the practicalities of canonization hearings, see André Vauchez, Sainteté en Occident aux derniers siècles du Moyen Âge. D’après les procès de canonisation et les documents hagiographiques (Rome: École française de Rome, 1988), 39–67; on papal pursuits in canonization procedures during the thirteenth century, see especially Roberto Paciocco, Canonizzazioni e culto dei santi nella christianitas (1198–1302) (Assisi: Edizioni Porziuncola, 2006). On canonization privilege, see Aviad Kleinberg, “Canonisation without a Canon,” in Procès de canonisation au Moyen Âge – Medieval Canonisation Processes, ed. Gábor Klaniczay (Rome: École française de Rome, 2004), 7–18. See also Sari Katajala-Peltomaa, “Recent Trends in the Study of Medieval Canonization Processes,” History Compass 8/9 (2010): 1083–1092 for the historiography.

- On the importance of miracles with biblical prototypes, see Sari Katajala-Peltomaa, Gender, Miracles and Daily Life. The Evidence of Fourteenth-Century Canonization Processes (Turnhout: Brepols, 2009), 25, and 54.

- Canon law influenced the practicalities and gave guidelines for the formation of the ques-tionnaire of the interrogators; considerations of gender, age and reputation were important aspects in the process of validation of witnesses, but no clear rules or norms to organize a canonization hearing were given in the major compilations. Christian Krötzl, “Prokuratoren, Notare und Dolmetscher. Zu Gestaltung und Ablauf der Zeugeinvernahmen bei Spätmittelalterlichen Kanonisationsprozessen,” Hagiographica V (1998): 119–140. On the veneration and canonization of saints in commentaries of canon law, see Thomas Wetzstein, Heilige vor Gericht. Das Kanonisationsverfahren im europäischen Mittelalter (Köln: Böhlau, 2004), 244–276. The methods of choosing the witnesses varied from one process to another, see Paolo Golinelli, “Social Aspects in Some Italian Canonization Trials,” in Procès de canonisation au Moyen Âge, 166–180. The intermingling of religious and medical spheres can also be seen in the fact that expert medical judgment was needed to authenticate miracles: physicians were favoured as witnesses in late medieval canonization processes. Joseph Ziegler, “Practitioners and Saints: Medical Men in Canonization Processes in the Thirteenth to Fifteenth Centuries,” Social History of Medicine 12: 2 (1999): 191–225. However, in cases of demonic possession they do not regularly appear as witnesses.

- Vauchez, La Sainteté en Occident, 53–54; Krötzl, “Prokuratoren, Notare und Dolmetscher,” 119–140, and Didier Lett, Un procès de canonisation au Moyen âge. Essai d’histoire sociale. Nicholas de Tolentino 1325 (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 2008), esp. 265.

- “Que est culpa mea, quid feci, quare me compellis? Ego super lactucam sedebam et ipsam non signavit et ideo cum lactuca me comedit.” Jacques de Vitry, Exempla or illustrative stories from the sermones vulgares, ed. Thomas Frederick Crane (London: Folklore Society, David Nutt, 1890), CXXX, 59.

- Gerardus de Fracheto, Gerardi de Fracheto O.P. Vitae fratrum Ordinis Praedicatorum, necnon Chronica ordinis ab anno MCCIII usque ad MCCLIV, ed. Benedictus Maria Reichert O.P. (Rome: Institutum Historicum Fratrum Praedicatorum, 1897), 81, 198–199. On similar reasoning, cf. Caesarius of Heisterbach, Dialogus Miraculorum, ed. Joseph Strange (Ridgewood: The Gregg Press Inc., 1966), V, 26 and “Miracula B. Ambrosii Senensis,” in AASS, Martii III, 235.

- “Non potest esse diabolus in anima humana…Cum diabolus dicitur esse in hominem, non intelligendum est de anima, sed de corpore, quia de concavitatibus eius et in visceribus ubi stercora continentur, et ipse esse potest.” Caesarius of Heisterbach, Dialogus Miraculorum, V, 15. Cf. Caciola, “Breath, Body, Guts,” 21–39.

- Nevertheless, opposing views had been aired from late Antiquity onwards. For example, Origen claimed that excessive joy, sorrow or love opened the minds of people for demons to gain lodgement, intemperance being an important element in this process. Henry Ansgar Kelly, The Devil, Demonology and Witchcraft. The Development of Christian Beliefs in Evil Spirits (New York: Doubleday & Company Inc., 1968), 35. At the beginning of the Early Modern Era possession was more easily linked with witchcraft and the possessed were seen as having willingly submitted to the Devil, or as the innocent victims of bewitchment. Alain Boureau, Satan Hérétique. Histoire de la Démonologie. Naissance de la démonologie dans l’Occident médiévale (1280–1330) (Paris: Odile Jacob, 2004); Michael Bailey, “From Sorcery to Witchcraft: Clerical Conceptions of Magic in the Later Middle Ages,” Speculum 78 (2001): 960–990, Kelly, The Devil, Demonology and Witchcraft.

- Definitions like energumeni or demoniaci can also be found. See also Newman, “Possessed by the Spirit,” 738 and Muriel Laharie, La folie au Moyen Âge XIe–XIIIe siècles (Paris: Le Léopard d’Or, 1991), 27.

- On cases with a swollen stomach as a sign of demonic possession, see Isak Collijn, ed., Acta et processus canonizacionis Beate Birgitte (Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet ser 2. Latinska Skrifter, Band 1) (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksells boktryckeri Ab, 1924–1931), 176–177, 130 and 142; “Miracula B. Ambrosii Senensis,” 235. Cf. Caciola, “Breath, Body, Guts,” 21–39.

- Respectively, explanations following the humoral theory argued that women’s wet and cold complexion made them more easily subject to raptures. Elliott, “The Physiology of Rapture,” 157–161, and Dyan Elliot, Fallen Bodies. Pollution, Sexuality, and Demonology in the Middle Ages (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999), 37–45. Cf. Caciola, “Mystics, Demoniacs, and the Physiology of Spirit Possession in Medieval Europe,” Comparative Studies in Society and History, 42: 2 (2000): 268–306, 289–290. See also the chapter of Timo Joutsivuo in this compilation.

- “Miracula B. Joanni Bonis Erem. Ord. S. Augusti,” in AASS, October IX: 767.

- “Processus apostolici de Beate Joanne Bono,” in AASS, October IX: 882–883.

- “Processus apostolici de Beate Joanne Bono,” 882. On the role of neighbours and common fama in defining madness in medieval French customals, see Aleksandra Pfau, “Protecting or Restraining? Madness as a Disability in Late Medieval France,” in Disability in the Middle Ages. Reconsiderations and Reverberations, ed. Joshua R. Eyler (Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, 2010), 93–104.

- Thomas de Celano, “Vita prima sancti Francisci,” in Legendae S. Francisci Assisiensis sae-culis XIII et XIV conscriptae ad codicum fidem recensitae a patribus collegii, ed. Collegium S. Bonaventurae (Quaracchi-Florence: Collegium S. Bonaventurae, 1926–1941), 108.

- The positive religious connotation originated from the Sermon on the Mount: Blessed are those who mourn, for they shall be comforted (Matt. 5: 3–5). The gratia lacrymarum could be defined largely as devotional weeping as contrition for sins. In this sense the gift of tears might be seen as a virtue. However, the concept was also used in a stricter sense when it became a mystical experience and could be seen as charisma. See Piroska Nagy, Le don des larmes au Moyen Âge. Un instrument spirituel en quête d’institution (Ve–XIIe siècle) (Paris: Albin Michel, 2000), 22–24. On water in blessings, Derek A. Rivard, Blessing the World. Ritual and Lay Piety in Medieval Religion (Washington, DC: The Catholic University of America Press, 2009).

- A well known example of a healing well was Fontetecta, outside Arezzo. It was a popular pilgrimage site, where parents used to seek a cure for their children by submerging them in the ice cold water. According to Bernardino of Siena, these rituals had superstitious or pagan connotations, and he had the well demolished and a chapel for Virgin Mary built in its place. Franco Mormando, The Preacher’s Demons. Bernardino of Siena and the Social Underworld of Early Renaissance Italy (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1999), 100–102. On submerging as a cure for demoniacs in Early Modern Scotland, see Joyce Miller, “Towing the Loon. Diagnosis and Use of Shock Treatment for Mental Illnesses in Early Modern Scotland,” in Dämonische Besessenheit, 127–143. On healing wells, see also Brigitte Caulier, L’eau et le sacré: les cultes thérapeutiques autour des fon-taines en France (Paris: Beauchesne, 1990).

- For example, Tertullian recommended the exorcism of baptismal water and vessel before their use, since unclean spirits settle upon waters. On polluted waters, see Rivard, Blessing the World, 227–228. In an early medieval monastic order, Regula Magistri, drinking of water was condemned, as it enticed phantasms and inebriated the mind; water and other “wet” substances were linked with arousal of senses and provocation to excess. Paolo Squatrati, Water and Society in Early Medieval Italy, 400–1000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 39–40.

- This canonization process was carried out in 1240–1241 in Orvieto. “Processus canoniza-tionis B. Ambrosii Massani,” in AASS Novembris, IV: 594–595. Cf. Florence Chave-Mahir, L’exorcism des possédes dans l’Église d’Occident (Xe–XIVe siècle) (Turnhout: Brepols, 2011), 255 for other cases connecting malediction and eating or drinking.

- Thomas de Papia, Dialogus de gestis sanctorum fratrum minorum, ed. Ferdinandus M. Delorme O.F.M. Bibliotheca Franciscana ascetica medii aevi 5 (Ad claras Aquas & Quaracchi: Collegium S. Bonaventurae, 1923), 157–158.

- “Processus canonizationis B. Ambrosii Massani,” 595.

- Squatriti, Water and Society, 23–27. See also Roberta Magnusson and Paolo Squatriti, “The Technologies of Water in Medieval Italy,” in Working with Water in Medieval Europe. Technology and Resource-Use, ed. Paolo Squatriti (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 217–265, esp. 241–244.

- Patricia Skinner, Health and Medicine in Early Medieval Southern Italy (Leiden: Brill, 1998), 30; Nancy Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 117, and Nancy Siraisi, History, Medicine, and the Traditions of Renaissance Learning (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2007), 95, 168–169. On unclean water as a punishment for relic theft, see Squatriti, Water and Society, 36–38. On disputes concerning pure water between health-concerned friars and townsfolk in southern Europe, see Angela Montfort, Health, Sickness, Medicine and the Friars in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1988), 47–51.

- Siraisi, Medieval & Early Renaissance Medicine, 137; Siraisi, History, Medicine, and the Traditions of Renaissance Learning, 184–187. On herbal remedies, see Peter Dendle and Alain Touwaide, Health and Healing form the Medieval Garden (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2008), Helena M. Paavilainen, Medieval Pharmacotherapy, Continuity and Change: Case Studies from Ibn Sīnā and some of His Late Medieval Commentators (Leiden: Brill, 2009), and Susanna Niiranen’s chapter in this collection. Fasting was often recommended for demoniacs and occasionally it was a prerequisite for successful exor-cism. Adolph Franz, Die Kirchlichen Benediktionen in Mittlelater, vol. II (Freiburg: Herder, 1909), 562–564 and Chave-Mahir, L’exorcisme des possédés, 113–115. Antispasmodic herbs were also used to cure diseases with spasms, like epilepsy, frenzy and occasionally even possession. Laharie, La folie au Moyen Âge, 210.

- Often Jews and lepers were groups facing such accusations. Michael R. McVaugh, Medicine before the Plague: Practitioners and Their Patients in the Crown of Aragon 1285–1345 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 220–222; Jon Arrizabalaga, “Facing the Black Death: Perceptions and Reactions of University Medical Practitioners,” in Practical Medicine from Salerno to the Black Death, ed. Luis García-Ballester et al. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1994), 237–288.

- Cf. BAV MS 4019 ff. 61v–62r for the case of Petronilla, a young wife who was sent to fetch the water by her in-laws. She failed and a quarrel ensued, leading to her affliction. Cf. Squatriti, Water and Society, 25.

- “Processus apostolici de Beate Joanne Bono,” 778–779.

- “Vita beati Ambrosii Senensis,” in AASS, Mart III: 198.

- Elliott, “The Physiology of Rapture,” 141–173, and Elliot, Fallen Bodies, 37–45. Cf. Caciola, “Mystics, Demoniacs, and the Physiology of Spirit Possession,” 268–306, 289–290.

- Cf. Caciola, Discerning Spirits, 40, who claims that in the medieval context diabolic pos-session was primarily thought to afflict females; Chave-Mahir, L’exorcism des possédés, 253–254, who argues for the feminization of the phenomenon from the twelfth century onwards, and Ferber, “Possession and the Sexes,” 214–238, who sees demonic possession at the beginning of the Early Modern Era as a typically feminine phenomenon.

- In the medieval literature mirrors and water often symbolized liminality and functioned as a passage to another world. See Susanna Niiranen, “Miroir de mérite” Valeurs sociales, rôles et image de la femme dans les textes médiévaux des trobairitz. Jyväskylä studies in Humanities 115 ( Jyväskylä: Jyväskylän yliopisto, 2009), 168–169.

- Acta et processus canonizacionis Beate Birgitte, 142.

- The canonization process of Peter of Luxemburg was carried out in 1389–1390. “Ad Processum de vita et Miraculis Beati Petri de Luxemburgo, duobus annis cum dimidio a Beati obiti formatum,” in AASS, Julii I: cap. CLXX, 506.

- Caciola, Discerning Spirits, 50.

- Carla Casagrande, “The Protected Women,” in A History of Women in the West. Vol. II. Silences of the Middle Ages, ed. Christiane Klapisch-Zuber (Cambridge: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1994), 70–104, esp. 85, and Robert C. Davis, “The Geography of Gender in the Renaissance,” in Gender and Society in Renaissance Italy, ed. Judith C. Brown and Robert C. Davis (London and New York: Longman, 1998), 19–38.

- Jacques de Vitry, Exempla, CCCXIV, 131; Etienne de Bourbon, Anecdotes historiques, légen-des et apologues tirés du recueil inédit d’Etienne de Bourbon dominicain du 13e siècle, ed. A. Lecoy de la Marche (Paris: Librairie Renouard, 1877), 461–462, 398–399; cap. 270, 226; Thomas of Cantimpré, Bonum universale de apibus quid illustrandis saeculi decimi tertii moribus conferat, ed. Elie Berger (Paris: Thorin, 1895), 54–55, and Caesarius of Heisterbach, Dialogus Miraculorum, IV, 11. However, there was no general agreement on the dangers of dancing; physicians could recommend dancing and music for the maintenance of health. See, for example, Timo Joutsivuo’s and Iona McCleery’s chapters in this collection.

- Acta et processus canonizacionis Beate Birgitte, 124.

- “…in ipso autem actu dissolutionis hujus arripuit eam daemon, ac vexare cepit per plures dies.” “Miracula B. Ambrosii Senensis,” 236. This hearing was ordained by the Bishop of Siena after the death of Ambrosius of Siena in 1287. Thus it was not an official canonization hearing carried out by papal commissioners.

- “Miracula B. Ambrosii Senensis,” 235.

- Punishing miracles were a known topos from Late Antiquity onwards. Gábor Klaniczay, “Miracoli di punizione e maleficia,” in Miracoli. Dai segni alla storia, ed. Sofia Boesch Gajanao and Marilena Modica (Rome: Viella, 2000), 109–135 and Paolo Golinelli, Il medio-evo degli increduli. Miscredenti, beffatori, anticlericali (Milano: Mursia, 2009), 67–73 and 90–93.

- The number of cases of demonic possession decreases in the hagiographic material dur-ing the later Middle Ages. According to Alain Boureau, the clerical authorities’ intention was to clarify the distinction between possession and mental illness, and as a result raving madness became more clearly a separate medical affliction. Therefore, cases of demonic possession are absent, especially in canonization processes under tight clerical control. Alain Boureau, “Saints et démons dans les procès de canonisation du début du XIVe siè-cle,” in Procès de canonisation au Moyen Âge, 199–221, esp. 203–209 and 220–221. Nancy Caciola, on the other hand, claims that deliveries from spirit possession did not decrease as such, but were no longer manifestations of divine grace made to happen by the inter-cession of a local patron, instead being ordained liturgical performances carried out by the clergy. Caciola, Discerning Spirits, 236.

- Joan Young Gregg, Devils, Women and Jews. Reflections of the Other in Medieval Sermon Stories (New York: State University of New York Press, 1997), 33. Terrifying visions of black shapes could also be a symptom of melancholy: see Catherine Rider’s chapter in this volume. Examples of demons in the form of a black animal can be found in Scandinavian material as well. Tryggve Lundén, ed., Processus canonizacionis beati Nicolai Lincopensis (Stockholm: Bonniers, 1963), 362–364 and Isak Collijn, ed., Processus seu Negocium Canonizacionis Katerine de Vadstenis (Svenska Fornskriftsällskapet ser 2. Latinska Skrifter, Band 2) (Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksells boktryckeri Ab, 1942–1946), 196–197. Diane Purkiss (Troublesome Things. A History of Fairies and Fairy Stories (London: Allen Lane The Penguin Press, 2000), 12–15 and 212–213) argues that blackness is a typical feature of malevolent supernatural creatures from Antiquity onwards.

- “Ad Processum de vita et Miraculis B. Petri de Luxemburgo,” CLXXII: 506.

- “Interrogata si persensit quando fugati sunt demones, respondit quod ita erat alienate mente quod <non> persensit. Interrogata quis erat present, quando fugati sunt demones, respondit quod non recordatur propter alienationem mentis.” “Processus canonizationis B. Ambrosii Massani,” 595.

- “Miracula Sancti Raymundi Palmarii confessoris,” in AASS, Iulii VI: 661–662. Cf. “Documenta de B. Odone Novariensi Ordinis Carthusiani,” in Analecta Bollandiana, I, ed. Carolus de Smedt et al. (Paris and Bruxelles: Société générale de librairie catholique, 1882), 323–354, “evomendo sanguinem nigrum,” 337; “pluries et turpiter vomendo sanata fuit et liberate a pluribus demoniis sicut ipsa dicebat,” 340 and Enrico Menestò, ed., Il processo di canonizzazione di Chiara da Montefalco (Spoleto: Centro italiano di studi sull’alto medioevo, 1984), testis CCXXIII, 500, “et vidit unum scardabonem nigrum in terra, qui dicebatur exivisse de hore eorum, sicut gentes asserebant.” The other victim was afflicted at a well.

- “expuebat sputum nigerrimum et carbones, recte indicans quod erat quia nemo dat quod non habet,” “Acta Beati Francisci Fabrianensis,” AASS, April III: 998.

- Placido Tommasso Lugano, ed., I processi inediti per Francesca Bussa di Ponziani (S. Francesca Romana) 1450–1453 Studi e testi, 120 (Rome: Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, 1945), 122–124.

- Johann Weyer, Witches, Devils, and Doctors in the Renaissance, ed. John Mora, trans. John Shea Medieval & Renaissance Texts and Studies, vol. 73 (New York: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies 1991), 286–291. More typical among the fifteenth-century clergy, however, was a growing concern about demons’ powers and the possible misuse of religious objects and rites while expelling them. Michael D. Bailey, Fearful Spirits, Reasoned Follies. The Boundaries of Superstition in Late Medieval Europe (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2013), particularly 172–173 for approach to protective rites.

- On madness as social construction, see Sylvia Huot, Madness in Medieval French Literature. Identities Found and Lost (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003); On neighbourhood testimonies and general fama in defining whether a person was mad or not, see Pfau, “Protecting or Restraining?,” in Disability in the Middle Ages, 94.

Contribution (108-127) from Mental (Dis)Order in Later Medieval Europe, edited by Sari Katajala-Peltomaa and Susanna Niiranen (Brill Academic Pub., 03.12.2014), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.