Major towns and cities might have many moneyers’ houses and workshops.

By Dr. Martin Allen

Senior Curator, Medieval Money

Fitzwilliam Museum

Affiliated Lecturer in History

University of Cambridge

One of the most important themes of Jim Bolton’s book Money in the Medieval English Economy 973–1489 is the crucial role of merchants in supplying bullion to the mints, and its economic context. It is the purpose of this chapter to explore further the activities of merchants as customers of the English mints and exchanges in the period covered by the book, the connections between the production of coinage and foreign and domestic trade, and official responses to monetary problems.

The English mints were usually dependent upon bullion imported by merchants to a great extent, although there were some limited supplies of locally mined silver; precious metal objects might be converted into coins; and the recycling of the currency in circulation could provide most of the bullion at times of recoinage.1 The great expansion in English mint outputs in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries may well have been largely supported by imports of German silver from Flemish and German merchants coming to England to buy wool and other commodities.2 England also had trade with Normandy, Scandinavia and Ireland in the eleventh century, attested by coin finds as well as by written sources, which probably provided some silver for the English mints.3 It has been argued that the Flemish cloth industry would not have needed significant quantities of English wool before the twelfth century, but this is far from certain, and in the twelfth century we begin to have good evidence for England’s wool trade with Flanders and exports via the Rhineland.4 Hermann of Laon’s account of the visit of canons of Laon to England in 1113 provides the earliest known documentary evidence for the wool trade with Flanders. The canons sailed from Wissant in Flanders to Dover with some Flemish merchants, who were carrying more than 300 marks (£200) in silver to buy English wool, which they deposited in a warehouse at Dover for eventual export (prevented by the warehouse burning down).5 The first book of Henry of Huntingdon’s Historia Anglorum (1131×1135) attributes England’s plentiful supplies of silver to its extensive commerce in wool and other goods with the Rhineland.6 It has been suggested that an increase in supplies of mined silver from Germany caused a substantial growth in the English currency from the 1170s.7

Merchants with silver to exchange for new English coins may have visited the moneyers at their houses or workshops, or have done business with them at a market.8 Major towns and cities might have many moneyers’ houses and workshops. In Winchester, the Winton Domesday (c.1110) documents five mint workshops (monete) destroyed to make room for the enlargement of the royal palace in the city; at least eighteen forges (forgiae), some of which may have been used by moneyers; and many houses of moneyers, both at the time of the survey and in the reign of Edward the Confessor (1042–66).9 There is further evidence of this kind in the Winchester survey of 1148.10 Some smaller urban centres may only have had the services of moneyers when they visited them to do business. The survey of the estates and revenues of Peterborough Abbey during the vacancy of 1125–8 notes that the moneyers of Stamford owed 20s a year for their exchanges at the markets of Oundle and Peterborough (which did not have resident moneyers), and another 20s at a recoinage.11 In 1129–33 a charter of Henry I granted the customs, exchange (bursam), market and port of Lynn (now King’s Lynn) to the bishop of Norwich, which may indicate that Norwich moneyers visited Lynn to exchange their coins.12

During the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries the number of English mints was progressively reduced, with some temporary increases, until by the early 1220s there were only three, in London, Canterbury and Bury St. Edmunds. The London and Canterbury mints now had almost complete control of the business generated by foreign trade, which was reinforced in 1221 by a writ to the abbot of Bury St. Edmunds, prohibiting the use of his mint to exchange the silver of merchants who would normally have gone to the London mint.13 In 1223 letters patent were sent to the merchants of Arras, Ghent, St. Omer and Ypres in Flanders informing them that their silver could now only be exchanged in London and Canterbury.14 Some foreign silver may have continued to go to the Bury St. Edmunds mint, but its exchange was leased to the king from 1223 to 1230.15

Flemish wool merchants never had a monopoly of the import of silver. In 1235 merchants of the Toulousain in southern France were licensed to import silver to be taken to the London and Canterbury mints, and about 200 marks of silver was stolen from some merchants of Brabant travelling through Hampshire in 1248.16 Richard Cassidy’s analysis of the merchants’ names in the four surviving rolls of purchase from the London and Canterbury exchanges in the 1250s and 1260s has shown that most of the names indicating places of origin relate to Flanders, Brabant and England, with a few names from Cologne, Hamburg, Gascony, Scotland and Denmark, and one Florentine.17 On a much smaller scale, an account of the Bury St. Edmunds mint for a few months of a year between 1268 and 1276 records purchases of silver from four merchants, two of them German and the other two English.18

During Simon de Montfort’s brief ascendancy in 1264–5 the wool trade and the English mints’ supplies of silver were severely affected by an Anglo-Flemish trade dispute. After de Montfort’s defeat and death at Evesham in 1265 steps had to be taken to encourage foreign merchants to come to England again, including the issue of a safe conduct to the merchants of Ghent bringing their silver to the London exchange.19 There was further disruption of the wool trade and mint business during a revival of the Anglo-Flemish dispute in the 1270s.20 Letters patent were issued in 1271 and 1272 to merchants of Brabant coming to England with silver for the London mint, giving them safe conduct, but the Anglo-Flemish dispute caused the closure of the Canterbury mint nonetheless.21 Later in the 1270s an epidemic of coin clipping also had a bad effect on mint business. The chronicler Thomas Wykes says that foreign merchants were staying away from England because they did not want to be paid in bad money.22 This problem was solved by Edward I’s recoinage of 1279–81, which removed from circulation the existing coinage, clipped and unclipped.

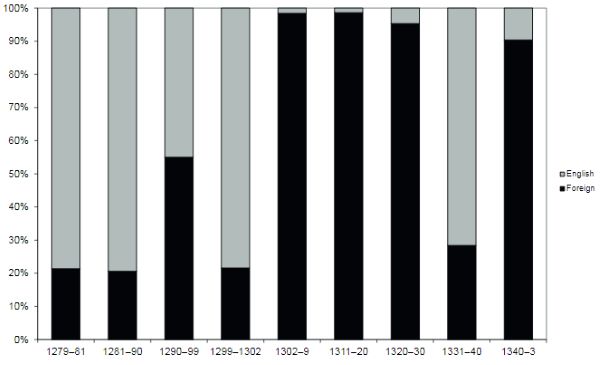

From the inception of Edward I’s recoinage in 1279 to 1343 the accounts of the London and Canterbury mints record purchases of imported foreign silver and English silver separately, because they incurred different minting charges.23 This provides a measure of the relative contributions of foreign and domestic sources of silver not available at any other time. It will be seen from Figure 10.1 that foreign silver was usually the main source of bullion, except at times of recoinage (1279–81 and 1299–1302), and in 1331–40, when imported foreign gold and silver coins were being used to pay for wool exports without being taken to the mints for conversion into English coins.24

The import and use of foreign coins by merchants was a perennial problem for medieval English governments and parliaments, causing them concern because it threatened the quality of the currency in circulation in England and took business away from the mints. The official responses to this problem in the 1280s and 1290s are particularly well documented. In 1283 John de Bourne was appointed to search for foreign coins imported at Dover and Sandwich, and in the following year the search was extended to other ports to enforce a statute against imported coins, but in 1285 John de Bourne was censured for confiscating money that foreign merchants had claimed they were taking to the mints.25 In 1289 the prohibition of foreign coins was reissued, and the searches were extended to further ports.26 A new statute against foreign and clipped coins in 1291 was followed in 1291–2 by confiscations from 138 foreign merchants at Dover and Sandwich, the checking of all money paid in at the exchequer, and searches at fairs, in the port of London, and on London Bridge.27 Some searches continued until 1296.28 After all this effort, nothing could be done to prevent the influx of the foreign sterlings known as pollards and crockards in the late 1290s that culminated in the Statute of Stepney in 1299 and the recoinage of 1300.29

Prohibitions of imported foreign coins continued until the 1470s, and in 1340 there was the first of a new series of regulations requiring merchants to deposit bullion with the mints or the customs collectors when they exported English goods (mainly wool).30 The Statute of Westminster required merchants to deposit 2 marks of silver for every sack of wool exported, but the re-enactment of this statute in 1343 was opposed by merchants in parliament on the grounds that they had to sell their wool for gold and not silver.31 The introduction of Edward III’s gold coinage in 1343–4 finally provided the means to convert the gold received by wool merchants into English coins. A last attempt to revive the statute of 1340 in 1348 was shelved after merchants successfully claimed in parliament that the count of Flanders, Louis de Male, had prevented their compliance by a ban on exports of bullion from his lands.32

The mint that opened at Calais in 1363 (after a false start in 1349–50), to serve the needs of the wool trade, became a focus of attempts to regulate the supply of bullion by merchants. In 1363 it was decreed that all foreign coins received by the Staple newly established at Calais should be taken to the mint, and in the following year this was superseded by new regulations requiring the deposit of three ounces of gold or its equivalent in silver for each sack of wool, but the effectiveness of these regulations is doubtful.33The regulations took no account of the increasing use of credit and bills and letters of exchange in the wool trade, which reduced the need to take bullion to Calais.34 The business of the Calais mint also seems to have been badly affected in the 1370s by the licensing of wool sales outside the control of the Staple, which was included in the articles of impeachment against Richard Lyons (the warden of the London mint) and Lord Latimer in the Good Parliament of 1376. In this parliament the London merchant Adam de Bury was accused of causing the closure of the king’s exchange in the city of London by exchanging in his own house.35

In 1379 a continuing shortage of bullion at the mints was the subject of a parliamentary enquiry. Mint officials and experts summoned to answer questions said that English coinage was being exported because it was too strong in comparison with foreign currency, and that any bullion imported was immediately re-exported. English silver coins were being exported in exchange for bad Scottish coins, and the coins remaining in circulation were being reduced in bullion value by clipping. The solutions proposed included requiring merchants to spend all of the proceeds of their sales of imports on English goods, the banning of exports of bullion and imports of Scottish and Flemish money, a strict control of the taking of money abroad to the papal curia and by clergy and pilgrims, and a reduction of the amount of gold in the English noble.36 All of these solutions would be tried, with varying degrees of success, over the next century or so. The most immediate result of the enquiry was an ordinance requiring the deposit of one shilling’s worth of gold for every pound in value of wool exports and certain luxury imports, which seems to have yielded no more than a relatively small amount of gold.37

Mint outputs continued to decline in the closing years of the fourteenth century, despite all official attempts to sustain them. Mints throughout Europe were feeling the effects of a ‘bullion famine’ (caused by a combination of a slump in mining outputs and the export of precious metals to the east), which was at its worst in the first decade of the fifteenth century, and a temporary recovery was followed by a second crisis from the 1440s to the 1460s.38 In response to the onset of the first bullion famine, bullion regulations of 1391 and 1397 required exporters to deposit one ounce of gold at the London mint for each sack of wool or 240 wool fells.39 These regulations were put into effect, although the merchants of the Calais Staple petitioned that it was inconvenient for them to take gold to London when there was a mint in Calais and a ban on the export of gold from the Burgundian Low Countries.40 Henry IV rescinded the requirement to take the gold to the London mint in his first parliament in 1399, but the Calais mint closed in 1403/4, as the bullion famine worsened.41 The merchants of the Staple may themselves have contributed to the difficulties of the Calais mint by using the light-weight imitations of the English noble struck in Flanders from 1388 to 1402. A petition in the parliament of 1401 complained that the Staplers were importing Flemish nobles (worth 2d less than the English originals) into England, and a ban on Flemish coins resulted.42

The severe shortage of bullion in the early years of the fifteenth century prompted the appointment of Richard Garner as master of the mints and warden of the city of London exchange in 1409, and the reductions of the weight standards of the coinage that followed.43 Weight reductions increased the prices that the mints were able to pay for bullion, and they could encourage the recoinage of heavier coins still in circulation. Mint outputs revived after the weight reductions of 1411/12, but many of the coins in circulation were clipped down to the new weights or below, causing a new problem.44 A statute in the parliament of May 1421 banned the use of gold coins weighing less than the official standard from the following Christmas. A London chronicle records that Londoners hastened to supply themselves with scales to weigh their gold coins, and that there was a shortage of silver coins caused by a reluctance to exchange silver for the now suspect gold.45 In the parliament of December 1421 the government had to concede that nobles containing only 5s 8d worth of gold would be accepted at their full face value of 6s 8d in payment of a lay subsidy granted to finance the war in France, and official weights were issued to check gold coins.46 A recoinage of clipped gold which lasted until about 1425 greatly increased activity at the mints and exchanges, at least temporarily.47

Bartholomew Goldbeter, the master of the royal mints from 1422 to 1431, was the subject of parliamentary petitions which throw some light upon relations between the mints and their merchant customers at this time. Goldbeter himself initiated the series of parliamentary exchanges on the master’s role with a petition in the parliament of November 1422 claiming that the terms of his indenture were too harsh, that his minting charges were too low, and that merchants should bear the cost of any losses of bullion in the minting process.48 The terms of the master’s indenture were not modified in Goldbeter’s favour, but he did obtain a potentially profitable appointment as warden of the city of London exchange (which was a separate operation from that of the London mint’s exchange in the Tower).49 In the parliament of October 1423 some of Goldbeter’s customers went on to the offensive, petitioning that he was over-charging for the minting of silver and making only gold nobles and silver groats and no smaller coins, contrary to his indenture.50 Goldbeter was ordered to pay a fair price for bullion and to observe the terms of his indenture, but a petition that he should exchange small sums free of charge was answered with an announcement that if any man would offer to do this he would be heard by Henry VI’s council.51 Another petition in this parliament of October 1423 complained that although a mint had been established in York for the recoinage of clipped coins, Goldbeter and his men had left York before their mission was accomplished, and the mint was ordered to be reopened.52

The petitions against Bartholomew Goldbeter do not complain about access to the mints when they were open, or about the speed of delivery of new coins, but these were issues that might cause concern. In 1344 the constable of the Tower had to be ordered to allow free access for merchants coming to the mint in the Tower, during daylight hours.53 Starting in 1355 mint indentures routinely specified that merchants should have free access to the Tower, without payments to porters or others, and they should not have to pay clerks for the issue of bills of receipt, which implies that such payments may have been demanded in the past. The indentures also required that new coins should be delivered to the merchants or their representatives at least once a week, and that if the money was insufficient to pay everybody in full they should be paid with regard to when they had delivered their bullion and its quantity.54

One of the complaints against Bartholomew Goldbeter in 1423 was that he was not making the smaller coins, contrary to the terms of his indenture.55 Goldbeter’s indenture did indeed specify the proportions of the gold and silver he received that were to be allocated to various denominations, as had been the case in most of the indentures since 1355, but he had no financial incentive to make the smaller coins, and many of his customers may have preferred to be paid in large denominations.56 The failure of the mints to provide sufficiently large quantities of small change for the needs of retail trade was a long-standing problem, reflected in many parliamentary petitions between 1363 and 1445.57 One such petition in 1402 resulted in a statute which included a provision that one third of the silver taken to the mint should be struck into halfpence and farthings, and another in 1445 led to an exceptional issue of light-weight halfpence in 1445–7.58

When Bartholomew Goldbeter was first appointed as master of the mints, in February 1422, the reopening of the Calais mint (closed since 1403/4) was in prospect.59 A petition in the parliament of December 1420 had unsuccessfully asked for the reopening of the Calais mint, supported by ‘hosting’ regulations, under which all alien merchants coming to Calais would have had to host with officially registered brokers and deposit their bullion and money with them. Foreign money and underweight English coins found on inspection would have been exchanged for new coins from the Calais mint.60 The merchants of the Staple continued their campaign for the reopening of their mint in the parliament of May 1421, petitioning that the wool subsidies could be paid in English gold nobles only, although they were not allowed to export these coins from England, but they were unsuccessful once more.61 In November 1421 the lieutenant and constables of the Staple wrote to Richard Whittington, the mayor of Calais, complaining they were being obliged to obtain nobles at great expense in Flanders to pay their dues, and seeking his help in speaking to Henry V’s council about the need to reopen the mint.62 Finally, a petition in the parliament of December 1421 was successful, and the mint was reopened in the summer of 1422.63 The Calais mint then embarked upon a period of exceptionally heavy output in gold, with a move to silver in the mid 1420s following changes in the mint prices for bullion in Flanders which made silver the metal of preference in payments for wool.64

Much of England’s export trade was conducted on credit and by sending money in bills of exchange, and this posed a constant threat to the viability of the Calais mint, the London mint and the city of London exchange. A statute of 1382 had prohibited the sending of money out of England by bills of exchange, except under licence, and another statute in 1390, re-enacted in 1401, stipulated that the full value of money sent abroad in exchange transactions and 50 per cent of the proceeds of sales by alien merchants in England should be spent or ‘employed’ on goods in England.65 In 1402 this ‘employment’ law was extended to 100 per cent of sales values (after reasonable expenses), and merchants were given only three months to make necessary purchases.66 In the parliament of 1404 Italian merchants petitioned unsuccessfully against the regulations, complaining that trade could not be conducted without exchange transactions between merchants.67 In this parliament the employment law was actually extended, placing all foreign merchants with English hosts, who would supervise their compliance with the bullion regulations, and the Italians petitioned to be able to choose their own hosts, in vain.68 The employment and hosting laws were reissued on many occasions until 1487.69

In 1429 parliament passed the Partition and Bullion Ordinances, to regulate the wool trade of the Staple at Calais and protect the mint. The ordinances required payment of the full purchase price of wool in gold or silver as soon as a deal was made, with a proportion of the price to be delivered to the Calais mint. These regulations, which were originally intended to last only three years, were subsequently extended indefinitely, but they seriously damaged England’s relations with Burgundy, which were of paramount importance to its foreign trade and to English interests in the closing stages of the Hundred Years War.70 The ordinances threatened the viability of the mints of Philip the Good, the duke of Burgundy, resulting in a Burgundian ban on exports of bullion to Calais in 1433, and a ban on purchases of English cloth in 1434.71 In 1435 Anglo-Burgundian negotiations to modify the ordinances were unsuccessful, and in September of that year Duke Philip switched sides in the war from England to France, in the treaty of Arras.72 A Burgundian siege of Calais in 1436 and subsequent hostilities caused the closure of the mint in 1436–7, and the conclusion of a treaty between England and Burgundy in 1439 did not end the Burgundian ban on bullion exports to Calais.73 In the parliament of January 1442 the merchants of the Staple attempted to resolve the situation by offering to take one third of the value of their wool in silver to the mint, in return for an abolition of the ordinances, but the implementation of this proposal was pre-empted by a mutiny of the Calais garrison in pursuit of arrears of wages, which forced a suspension of all requirements to take bullion to the mint in October 1442.74 There was a short-lived revival in mint output at Calais, but the Burgundian ban on bullion exports remained, and the mint closed for good in about 1450.75 The ordinances were reissued in 1454, and the formal end of the Burgundian ban on bullion exports was delayed until 1489.76 In these circumstances a statute of 1463 requiring purchasers of wool to pay one half of the purchase price in English coins or in bullion taken to the Calais mint did not cause the mint to reopen.77

The English mints and exchanges could not have existed without the silver and gold of merchants. The wool trade and supplies of imported silver were of great importance to the production of the English coinage from the twelfth century and probably earlier, but the mints and exchanges were highly vulnerable to fluctuations in trade and European supplies of precious metals. Official attempts to regulate the activities of merchants in bringing bullion to the mints or taking it out of England might be limited in success or actively counterproductive.

Endnotes

- M. Allen, ‘Silver production and the money supply in England and Wales, 1086–c.1500’, Economic History Review, lxiv (2011), 114–31; M. Allen, Mints and Money in Medieval England (Cambridge, 2012), pp. 295–316; J. L. Bolton, Money in the Medieval English Economy 973–1489 (Manchester, 2012), pp. 66–8.

- P. H. Sawyer, ‘The wealth of England in the eleventh century’, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th ser., xv (1965), 145–64, at pp. 158–63; D. M. Metcalf, ‘Continuity and change in English monetary history c.973–1086. Part 2’, British Numismatic Journal, li (1981), 52–90, at pp. 57–8; P. Nightingale, ‘The evolution of weight-standards and the creation of new monetary and commercial links in northern Europe from the tenth century to the twelfth century’, Economic History Review, 2nd ser., xxxviii (1985), 192–209, at pp. 99–101; P. Spufford, Money and its Use in Medieval Europe (Cambridge, 1988), pp. 74, 86–90; P. Sawyer, The Wealth of Anglo-Saxon England (Oxford, 2013), pp. 15–20, 98–101, 111, 114.

- M. Dolley, ‘The coins and jettons’, in Excavations in Medieval Southampton 1953–1969: the Finds, ed. C. Platt and R. Coleman-Smith (2 vols., Leicester, 1975), ii. 315–31, at pp. 326–8; P. Sawyer, ‘Anglo-Scandinavian trade in the Viking age and after’, in Anglo-Saxon Monetary History: Essays in Memory of Michael Dolley, ed. M. A. S. Blackburn (Leicester, 1986), pp. 185–99, at pp. 185–7, 191–9; D. M. Metcalf, An Atlas of Anglo-Saxon and Norman Coin Finds, c.973–1086 (Royal Numismatic Society Special Publication, xxxii, 1998), pp. 86, 88–9; M. Gardiner, ‘Shipping and trade between England and the Continent during the eleventh century’, Anglo-Norman Studies, xxii (1999), 71–93, at pp. 73, 83, 92–3; B. Cook, ‘Foreign coins in medieval England’, in Local Coins, Foreign Coins: Italy and Europe 11th–15th Centuries. The Second Cambridge Numismatic Symposium, ed. L. Travaini (Società Numismatica Italiana Collana di Numismatica e Scienze Affini, 8 vols., Milan, 1999), ii. 231–84, at pp. 237–8, 269–70; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 253.

- T. H. Lloyd, The English Wool Trade in the Middle Ages (Cambridge, 1977), pp. 1–2, 6–7; T. H. Lloyd, Alien Merchants in England in the High Middle Ages (Brighton, 1982), pp. 10–12, 98–9, 128–9; Nightingale, ‘The evolution of weight-standards’, pp. 203–4, 207; Sawyer, ‘Anglo-Scandinavian trade’, pp. 187–91; D. Nicholas, Medieval Flanders (1992), pp. 113, 116–17; E. Miller and J. Hatcher, Medieval England: Towns, Commerce and Crafts 1086–1348 (1995), pp. 188–94; A. Verhulst, The Role of Cities in North-West Europe (Cambridge, 1999), pp. 136–7; Gardiner, ‘Shipping and trade’, pp. 73–4; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 253; Bolton, Money in the Medieval English Economy, p. 98; Sawyer, The Wealth of Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 15–20.

- Patrologia Latina, ed. J. P. Migne (217 vols., Paris, 1844–55), clvi. cols. 975–7; J. S. P. Tatlock, ‘The English journey of the Laon canons’, Speculum, viii (1933), 454–65, at pp. 456–7; E. Power, The Wool Trade in English Medieval History (Oxford, 1941), p. 52; R. Bartlett, England under the Norman and Angevin Kings 1075–1225 (Oxford, 2000), p. 368; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 253–4; Sawyer, The Wealth of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 105.

- Historia Anglorum, ed. and trans. D. Greenway (Oxford, 1996), pp. lxvi–lxxvii, 10–11; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 254: Sawyer, The Wealth of Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 26, 105, 114.

- P. D. A. Harvey, ‘The English inflation of 1180–1220’, Past & Present, lxi (1973), 3–30, at pp. 25–8; Harvey, ‘The English trade in wool and cloth, 1150–1250: some problems and suggestions’, in Produzione, commercio e consumo dei panni di lana, ed. M. Spallanzani (Florence, 1976), pp. 369–75, at pp. 370–2, 375; N. J. Mayhew, ‘Frappes de monnaies et hausse des prix en Angleterre de 1180 à 1220’, in Études d’histoire monétaire XIIe–XIXe siècles, ed. J. Day (Lille, 1984), pp. 159–77, at pp. 166–8; A. Dawson and N. Mayhew, ‘A Continental find including Tealby pennies’, British Numismatic Journal, lvii (1987), 113–18, at p. 115; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 254–5.

- M. Biddle and others, Winchester in the Early Middle Ages: an Edition and Discussion of the Winton Domesday (Winchester Studies 1, Oxford, 1976), pp. 402, 421, 443–4.

- Biddle, Winchester in the Early Middle Ages, pp. 397–403, 405, 407, 409–10, 421–2; D. M. Metcalf, ‘The premises of early medieval mints: the case of eleventh-century Winchester’, in I luoghi della moneta le sedi delle zecche dall’antichità all’età moderno. Atti del convegno internazionale 22–23 ottobre 1999 Milano, ed. R. La Guardia (Milan, 2001), pp. 59–67, at pp. 60–1; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 6–7.

- Biddle, Winchester in the Early Middle Ages, pp. 415–21; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 7–8.

- Chronicon Petroburgense, ed. T. Stapleton (Camden Series, xlvii, 1849), p. 166; W. C. Wells, ‘The Stamford and Peterborough mints. Part 1’, British Numismatic Journal, xxii (1934–37), 35–77, at pp. 54, 57; E. King, ‘Economic development in the early twelfth century’, Progress and Problems in Medieval England, ed. R. Britnell and J. Hatcher (Cambridge, 1996), pp. 1–22, at p. 15; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 3, 11.

- Regesta regum anglo-normannorum, 1066–1154, ed. H. W. C. Davis, C. Johnson and H. Cronne (4 vols., Oxford, 1913–69), ii. 279, no. 1853; King, ‘Economic development’, p. 15; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 3.

- Rotuli litterarum clausarum in Turri Londinensi asservati, ed. T. D. Hardy (2 vols., London 1833–44), i. 479; J. D. Brand, The English Coinage 1180–1247: Money, Mints and Exchanges (British Numismatic Society Special Publication, i, 1994), p. 49; R. J. Eaglen, The Abbey and Mint of Bury St. Edmunds to 1279 (British Numismatic Society Special Publication, iv, 2006), p. 147; A. Gransden, A History of the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds 1182–1256 (Samson of Tottington to Edmund of Walpole) (Studies in the History of Medieval Religion, xxxi, Woodbridge, 2007), p. 241; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 59, 257.

- CPR 1216–1225, p. 366; L. A. Lawrence, ‘The short-cross coinage, 1180 to 1247’, British Numismatic Journal, xi (1915), 59–100, at pp. 73–4; The De moneta of Nicholas Oresme and English Mint Documents, ed. and trans. C. Johnson (1956), p. xxiii; Gransden, A History of the Abbey of Bury St. Edmunds, p. 241.

- CPR 1216–1225, pp. 405–6; CCR1227–1231, p. 299; Brand, The English Coinage, p. 49; Eaglen, The Abbey and Mint, pp. 147–8; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 257.

- CPR 1232–1247, p. 90; Chronica majora, ed. H. R. Luard (Rolls Series, lvii, 7 vols., 1872–83), v. 56–60; M. T. Clanchy, ‘Highway robbery and trial by battle’, in Medieval Legal Records Edited in Memory of C. A. F. Meekings, ed. R. F. Hunnisett and J. B. Post (1978), pp. 26–61; N. Fryde, ‘Silver, recoinage and royal policy in England 1180–1250’, in Minting, Monetary Circulation and Exchange Rates, ed. E. van Cauwenberghe and F. Irsigler (Trierer Historische Forschungen, vii, Trier, 1984), pp. 11–30, at pp. 20–2, 26; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 257.

- R. Cassidy ‘The exchanges, silver purchases and trade in the reign of Henry III’, British Numismatic Journal, lxxxi (2011), 107–18, at pp. 113–16.

- BL, Harley MS 645, fo. 219; M. Allen, ‘Documentary evidence for the output, profits and expenditure of the Bury St. Edmunds mint’, British Numismatic Journal, lxix (1999), 211–13.

- Chronicon Petroburgense, pp. 69, 73; Annales monastici, ed. H. R. Luard (Rolls Series xxxvi, 4 vols., 1864–69), iv. 158–9; CPR 1258–1266, pp. 454, 459; Allen, Mints and Money, 257; R. Cassidy, ‘The royal exchanges and mints in the period of baronial reform’, British Numismatic Journal, lxxxiii (2013), 134–48, at p. 145.

- Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 25–59; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 258; Cassidy, ‘The royal exchanges and mints’, p. 145.

- CPR 1266–1272, pp. 522, 632; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 257; Cassidy, ‘The royal exchanges and mints’, p. 145.

- Annales monastici, iv. 278; M. Mate, ‘Monetary policies in England, 1272–1307’, British Numismatic Journal, xli (1972), 34–79, at pp. 40–1.

- C. G. Crump and C. Johnson, ‘Tables of bullion coined under Edward I, II, and III’, The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society, 4th ser., xiii (1913), 200–45, at pp. 204–16, 226–32; H. A. Miskimin, Money, Prices, and Foreign Exchange in Fourteenth-Century France (1963), pp. 96–8; Mate, ‘Monetary policies’, pp. 75, 78; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 259–60.

- M. Mate, ‘High prices in early fourteenth-century England: causes and consequences’, Economic History Review, 2nd ser., xxviii (1975), 1–16, at p. 13; T. H. Lloyd, ‘Overseas trade and the English money supply in the fourteenth century’, in Edwardian Monetary Affairs (1279–1344): a Symposium held in Oxford, August 1976, ed. N. J. Mayhew (British Archaeological Reports xxxvi, Oxford, 1976), pp. 96–124, at pp. 105–8; N. J. Mayhew, ‘From regional to central minting, 1158–1464’, in A New History of the Royal Mint, ed. C. E. Challis (Cambridge, 1992), pp. 83–178, at pp. 143–4; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 261–2.

- CPR 1281–1292, p. 86; Statutes of the Realm, i. 219; R. Ruding, Annals of the Coinage of Great Britain and its Dependencies; from the Earliest Period of Authentic History to the Reign of Victoria (3rd edn., 3 vols., 1840), i. 196–7; M. Prestwich, ‘Edward I’s monetary policies and their consequences’, Economic History Review, 2nd ser., xxii (1969), 406–16, at pp. 407–9; Mate, ‘Monetary policies’, pp. 56–7; J. H. Munro, ‘Bullionism and the bill of exchange in England, 1272–1663: a study in monetary management and popular prejudice’, in The Dawn of Modern Banking, ed. F. Chiappelli (1979), pp. 169–239, at pp. 188–9, 216; N. J. Mayhew, Sterling Imitations of Edwardian Type (Royal Numismatic Society Special Publication xiv, 1983), p. 18; M. B. Mitchiner and A. Skinner, ‘Contemporary forgeries of English silver coins and the chemical compositions: Henry III to William III’, The Numismatic Chronicle, cxlv (1985), 209–36, at pp. 214, 226; Cook, ‘Foreign coins’, p. 250; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 259, 355.

- CCR 1288–1296, p. 9; Mate, ‘Monetary policies’, p. 57; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 355.

- Statutes of the Realm 1101–1713, ed. A. Luders, T. E. Tomlins, J. France, W. E. Taunton and J. Raithby (11 vols., 1810–28), i. 220; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 198–9; Mate, ‘Monetary policies’, pp. 58–9; N. J. Mayhew and D. R. Walker, ‘Crockards and pollards: imitation and the problem of fineness in a silver coinage’, in Mayhew, Edwardian Monetary Affairs, pp. 125–46, at p. 130; Munro, ‘Bullionism and the bill of exchange’, pp. 188–9; Mitchiner and Skinner, ‘Contemporary forgeries’, p. 215; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 355.

- J. C. Davies, ‘The wool customs accounts for Newcastle upon Tyne for the reign of Edward I’, Archaeologia Æliana, 4th ser., xxxii (1954), 220–308, at pp. 275–96; Mate, ‘Monetary policies’, pp. 59–60, 63; J. D. Brand, ‘A glimpse of the currency in 1295’, Spink Numismatic Circular, xcv (1987), 215–16, 251–3, at pp. 251–2; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 355–6.

- Statutes of the Realm, i. 131–5; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 199–201; Mate, ‘Monetary policies’, pp. 63–4; Mayhew, ‘From regional to central minting’, pp. 138–40; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 193–4, 260–1, 356–7; Bolton, Money in the Medieval English Economy, pp. 161–2.

- Munro, ‘Bullionism and the bill of exchange’, pp. 192–6, 216–19.

- Rot. Parl., ii. 105, 137–8; Statutes of the Realm, i. 289, 291; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 213, 216; J. H. Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold: the Struggle for Bullion in Anglo-Burgundian Trade, 1340–1478 (Brussels and Toronto, 1973), p. 36; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 183–5, 196–8; Lloyd, ‘Overseas trade’, pp. 109–10; M. Mate, ‘The role of gold coinage in the English economy, 1338–1400’, Numismatic Chronicle, 7th ser., xviii (1978), 126–41, at pp. 127–8; Munro, ‘Bullionism and the bill of exchange’, pp. 193, 226; Mayhew, ‘From regional to central minting’, pp. 163–6; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 263.

- Rot. Parl., ii. 202, no. 15; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 35–7; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 183–4, 196–7; Munro, ‘Bullionism and the bill of exchange’, p. 193.

- Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, ii. 255; L. Deschamps de Pas, ‘Études sur les monnaies de Calais’, Revue Belge de Numismatique, xxxix (1883), 175–224, at pp. 182–6; A. S. Walker, ‘The Calais mint, A.D. 1347–1470’, British Numismatic Journal, xvi (1921–22), 77–112, at pp. 107–9; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 39–40; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 266.

- Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 240–2, 244; Lloyd, ‘Overseas trade’, p. 118.

- Rot. Parl.. ii. 323–5, 330; CFR1369–1377, p. 348; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 233; T. F. Reddaway, ‘The king’s mint and exchange in London 1343–1543’, English Historical Review, lxxxii (1967), 1–23, at p. 9; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, p. 223; P. Woodhead, ‘Calais and its mint: part two’, in Coinage in the Low Countries (880–1500): the Third Oxford Symposium on Coinage and Monetary History, ed. N. J. Mayhew (British Archaeological Reports International Series, liv, Oxford, 1979) pp. 185–202, at p. 188; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 220, 267.

- Rot. Parl.,iii. 126–7; Munro, ‘Bullionism and the bill of exchange’, pp. 202–3; W. M. Ormrod, ‘The Peasants’ Revolt and the government of England’, Journal of British Studies, xxix (1990), 1–30, at p. 27; Mayhew, ‘From regional to central minting’, pp. 170–1; P. Nightingale, A Medieval Mercantile Community: the Grocers’ Company and the Politics and Trade of London, 1000–1485 (1995), p. 258 n. 2; J. L. Bolton, ‘Was there a “crisis of credit” in fifteenth-century England?’, British Numismatic Journal, lxxxi (2011), 144–64, at pp. 149–50; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 267; Bolton, Money in the Medieval English Economy, pp. 245–6, 247–8.

- Rot. Parl., iii. 66, 392; CCR1377–1381, p. 193; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 237–9; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, p. 44; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, p. 242; Lloyd, ‘Overseas trade’, p. 117; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 267.

- J. Day, ‘The great bullion famine of the fifteenth century’, Past & Present, lxxix (1978), 3–54 (reprinted in J. Day, The Medieval Market Economy (Oxford, 1987), pp. 1–54); Spufford, Money and its Use, pp. 339–62; Bolton, ‘Was there a “crisis of credit”’, p. 145; Bolton, Money in the Medieval English Economy, pp. 47, 232–6, 249.

- Rot. Parl., iii. 285, 340; CCR 1389–1392, pp. 422–3, 448, 527–8; CCR 1396–1399, pp. 37–8, 88–9; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 246; E. E. Power, ‘The wool trade in the fifteenth century’, in Studies in English Trade in the Fifteenth Century, ed. E. E. Power and M. M. Postan (1933), pp. 39–90, at p. 80; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 46, 54–5; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 243–5; Lloyd, ‘Overseas trade’, p. 118; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 267–9.

- Rot. Parl., iii. 369–70; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 246–7; Walker, ‘The Calais mint’, pp. 110–11; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, p. 56; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, p. 245; Lloyd, ‘Overseas trade’, pp. 118–19; J. H. Munro, ‘Mint policies, ratios, and outputs in the Low Countries and England, 1335–1420: some reflections on new data’, Numismatic Chronicle, cxli (1981), 71–101, at pp. 87–8; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 268.

- Rot. Parl., iii. 429; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 249; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 56–7; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, p. 245; Lloyd, ‘Overseas trade’, pp. 118–19; Woodhead, ‘Calais and its mint’, pp. 188–9; Munro, ‘Mint policies’, pp. 91–2; M. Allen, ‘The output and profits of the Calais mint, 1349–1450’, British Numismatic Journal, lxxx (2010), 131–9, at pp. 134, 138; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 270.

- Rot. Parl., iii. 470; Statutes of the Realm, ii. 122; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 250; Power, ‘The wool trade’, pp. 80–1; P. Spufford, ‘Continental coins in late medieval England’, British Numismatic Journal, xxxii (1963), 127–39, at pp. 130–1; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, p. 60; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, p. 245; Munro, ‘Mint policies’, p. 92; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 270–1.

- CPR 1408–1413, p. 102; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 254–5; C. E. Blunt, ‘Unrecorded heavy nobles of Henry IV and some remarks on that issue’, British Numismatic Journal, xxxvi (1967), 106–13, at pp. 111–13; Reddaway, ‘The king’s mint and exchange’, pp. 13–14; Mayhew, ‘From regional to central minting’, pp. 172–3; M. Allen, ‘Italians in English mints and exchanges’, in Fourteenth Century England II, ed. C. Given-Wilson (Woodbridge, 2002), pp. 53–62, at pp. 61–2; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 87–8.

- M. M. Archibald with A. G. MacCormick, ‘The Attenborough, Notts. 1966 hoard’, British Numismatic Journal, xxxviii (1969), 50–83, at pp. 60–4; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 285.

- Statutes of the Realm, ii. 208–9; The Great Chronicle of London, ed. A. H. Thomas and I. D. Thornley (1938), p. 119; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 263–4; Bolton, Money in the Medieval English Economy, p. 237.

- Rot. Parl., iv. 151, no. 10; iv. 155, no. 21; CFR 1413–1422, p. 414; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 264–6, 269; Reddaway, ‘The king’s mint and exchange’, p. 14; T. F. Reddaway and L. E. M. Walker, The Early History of the Goldsmiths’ Company 1327–1509 (1975), p. 112; N. Biggs, ‘Coin-weights in England – up to 1588’, British Numismatic Journal, lx (1990), 65–79, at p. 72; Mayhew, ‘From regional to central minting’, p. 173; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 151–2; Bolton, Money in the Medieval English Economy, p. 47.

- Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 227–8, 285–6.

- Rot. Parl., iv. 177–8, no. 35; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 267–8; ii. 142; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 180.

- Statutes of the Realm, iv. 178; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 268–9.

- Rot. Parl., iv. 257–8, no. 55; Statutes of the Realm, ii. 223; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 271–2.

- Rot. Parl., iv. 258, no. 55; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 272.

- Rot. Parl., iv. 200, no. 12; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, ii. 269–70; M. Allen, ‘Documentary evidence for the Henry VI Annulet coinage of York’, British Numismatic Journal, lxv (1995), 120–34.

- CCR 1343–6, p. 327; B. J. Cook ‘The late medieval mint of London’, in La Guardia, I luoghi della moneta, pp. 101–13, at p. 106.

- CCR1354–1360, pp. 236–7; Mayhew, ‘From regional to central minting’, pp. 168–9; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 80 (A New History of the Royal Mints, ed. C. E. Challis (Cambridge, 1992), pp. 699–758 summarizes the mint indentures with references).

- Rot. Parl., iv. 257–8, no. 55; Statutes of the Realm, ii. 223; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 271–2.

- CCR 1422–1429, pp. 59–62; M. Allen, ‘The proportions of the denominations in English mint outputs, 1351–1485’, British Numismatic Journal, lxxvii (2007), 190–209, at pp. 190–2.

- J. Kent, Coinage and Currency in London from the London and Middlesex Records and other Sources: from Roman Times to the Victorians (2005), pp. 30–1, 33; Allen, ‘The proportions of the denominations’, pp. 192–4; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 360; Bolton, Money in Medieval English Society, pp. 250–1.

- Rot. Parl., iii. 498, no. 46; v. 108–9; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 250–1, 275–6; Mayhew, ‘From regional to central minting’, p. 176; Allen, ‘The proportions of the denominations’, pp. 193–4; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 361–3.

- CCR 1419–1422, pp. 230–4; Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council of England 1386–1542, ed. N. H. Nicolas (7 vols., 1834–37), ii. 332; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 256, 264; Deschamps de Pas, ‘Études sur les monnaies’, pp. 194–6; Walker, ‘The Calais mint’, pp. 90–1; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, p. 73; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 248, 258–9; Woodhead, ‘Calais and its mint’, p. 189; Challis, A New History, pp. 708–9; Allen, ‘The output and profits’, pp. 134–5.

- Rot. Parl., iv. 125–6; Statutes of the Realm, ii. 203; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 263; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, p. 72; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, p. 247.

- Rot. Parl., iv. 146; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 264; Deschamps de Pas, ‘Études sur les monnaies’, pp. 194–5; Walker, ‘The Calais mint’, p. 90; Power, ‘The wool trade’, p. 81; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, p. 73; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, p. 248; Woodhead, ‘Calais and its mint’, p. 189.

- Power, ‘The wool trade’, pp. 81–2.

- Rot. Parl., iv. 154; Statutes of the Realm, ii. 210; Walker, ‘The Calais mint’, p. 90; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 248, 258–9; Allen, Mints and Money, pp. 271–2.

- P. Spufford, Monetary Problems and Policies in the Burgundian Netherlands 1433–1496 (Leiden, 1970), p. 97; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 73–4, 81–3; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 259–60; J. H. Munro, ‘Bullion flows and monetary contraction in late-medieval England and the Low Countries’, in Precious Metals in the Later Medieval and Early Modern Worlds, ed. J. F. Richards, (Durham, N.C., 1983), pp. 97–158, at pp. 116–17, 124; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 272.

- Statutes of the Realm, ii. 17–18, 96; ii. 122; Rot. Parl., iii. 119–21, 278, 468; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 249–50; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, p. 45; Munro, ‘Bullionism and the bill of exchange’, pp. 202–4; Allen, Mints and Money, p. 221.

- Rot. Parl., iii. 509, no. 103; Statutes of the Realm ii. 142; CCR 1399–1402, p. 596; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 251.

- Rot. Parl., iii. 553, nos 37–38; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 253.

- Statutes of the Realm, ii. 145–6; Rot. Parl., iii. 553, no. 39; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 252–3.

- Munro, ‘Bullionism and the bill of exchange’, pp. 198–205, 228–30.

- Rot. Parl., iv. 359, 454; Statutes of the Realm, ii. 254–5; Walker, ‘The Calais mint’, pp. 109–10; Power, ‘The wool trade’, pp. 82–3; Spufford, Monetary Problems, pp. 99–100; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 84–6, 91–2, 99–100; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 261–2; Munro, ‘Bullionism and the bill of exchange’, pp. 195–6; Bolton, Money in the Medieval English Economy, p. 246.

- Power, ‘The wool trade’, pp. 84–5; Spufford, Monetary Problems, p. 100; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 86–8, 93, 98–9, 102–4, 106–10.

- Power, ‘The wool trade’, p. 85; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 110–12.

- Power, ‘The wool trade’, pp. 83–8; Spufford, Monetary Problems, pp. 101–4; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 112–15, 117–120, 122; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 263, 266, 268; Allen, ‘The output and profits’, pp. 136–8.

- Rot. Parl., v. 64; Statutes of the Realm, ii. 324–5; Proceedings and Ordinances of the Privy Council, v. 216–17, 219–22; Power, ‘The wool trade’, pp. 88–9; Spufford, Monetary Problems, p. 104; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 124–6; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 268–9.

- Rot. Parl., v. 275–7; Ruding, Annals of the Coinage, i. 277; Deschamps de Pas, ‘Études sur les monnaies’, p. 200; Power, ‘The wool trade’, p. 89; Spufford, Monetary Problems, pp. 104–5; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 150–1; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 268–9; P. Spufford, ‘Calais and its mint: part one’, in Coinage in the Low Countries (880–1500). The Third Oxford Symposium on Coinage and Monetary History, ed. N. J. Mayhew (British Archaeological Reports International Series, liv, Oxford, 1979), pp. 171–83, at pp. 177–8; Allen, ‘The output and profits’, pp. 136–8.

- Rot. Parl., v. 256; Spufford, Monetary Problems, p. 106; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, pp. 148–9; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, p. 274.

- Rot. Parl., v. 503–8; Statutes of the Realm, ii. 392–4; Deschamps de Pas, ‘Études sur les monnaies’, p. 201; Munro, Wool, Cloth and Gold, p. 159; Lloyd, The English Wool Trade, pp. 277–9; Munro, ‘Bullionism and the bill of exchange’, p. 205.

Chapter 10 (197-212) from Medieval Merchants and Money: Essays in Honour of James L. Bolton, edited by Martin Allen and Matthew Davies (Institute of Historical Research, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 06.30.2016), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons