The rebuilding of London Bridge in stone was a significant bridge building project.

By Dr. John A. McEwan

Assistant Professor, Digital Humanities

Saint Louis University

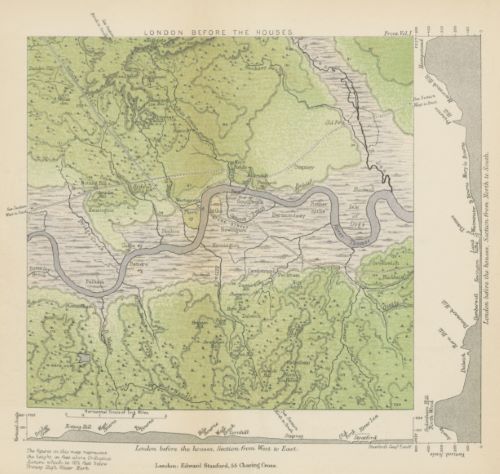

The rebuilding of London Bridge in stone in the period c.1176–1209 was a major undertaking, similar in scale to building ‘a large castle or cathedral in terms of costs, manpower and materials required’.1 When completed, the new bridge not only proved an important amenity for the people of London, allowing them to pass with greater ease over the River Thames and bringing more trade to their city, but also posed political challenges. Londoners invested significant resources in building the bridge, but keeping it in working order required constant maintenance.2 Who would pay for repairs and ensure they were carried out? By studying the men who took charge of the bridge in the years between c.1176 and 1275, the shifting balance of power between the various groups that had an interest in the bridge can be traced and through this the growth of the authority of the civic government over the city of London and its people.

The rebuilding of London Bridge in stone was a significant bridge building project, but within its regional context it was not unique. In England and France in the twelfth century a number of bridges were built, or rebuilt, in stone and these projects were organized in a variety of ways.3 People considered the building and maintaining of bridges a Christian work and could treat them as charitable enterprises.4 Kings could also support bridge-building through the imposition of taxes and other customary duties.5 In London the stone bridge replaced an earlier bridge which was once supported by a customary duty.6 Therefore, in the late twelfth century the Londoners could look for inspiration and models for the finance and governance of the stone bridge to charitable bridge-building projects and to their own experiences with royal administration.

There is little evidence, it is important to note, to suggest that London’s own civic government could make a substantial contribution to the administration of London Bridge in the twelfth century.7 Nonetheless, by the later thirteenth century the city had assumed an important role. A sign of this development is a reference in 1275 to the civic government holding an election to appoint men to take charge of the bridge.8 Therefore, between c.1176 and 1275 the city’s role in the administration of the bridge had changed, but when did this change happen and what do the timing and circumstances of the change reveal about the development of the government’s relationship with the people of the city? The bridge’s records offer evidence that previous scholars have not fully taken into account.

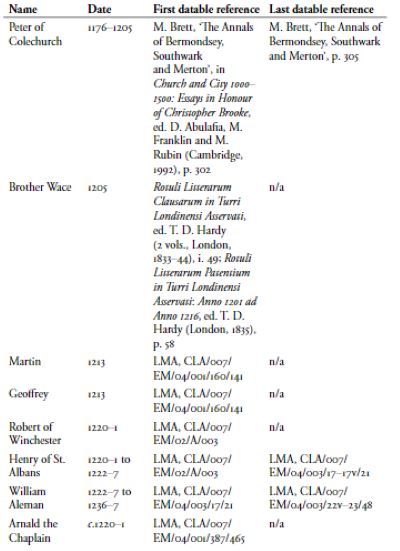

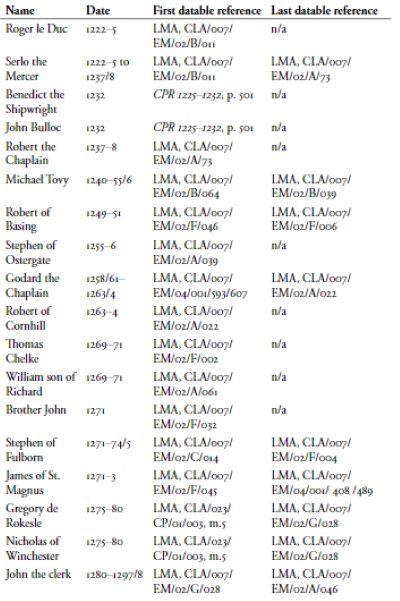

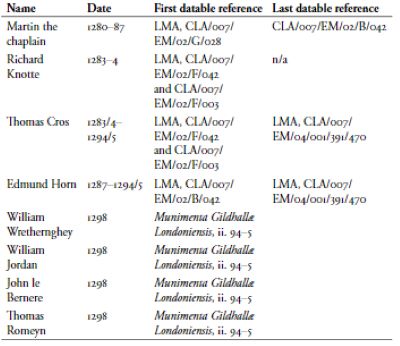

The bridge’s archives preserve property records that name men who acted on behalf of the bridge from the late twelfth century onwards (Table 10.1). Gwyn Williams, in his study of thirteenth- and fourteenth-century London, demonstrated that the history of the government could fruitfully be approached through the personal histories of the leading men in the community.9 Using similar methods, this chapter will trace the history of the bridge by establishing the sequence of men involved in its direction and considering their backgrounds, interests and affiliations. Some men were only associated with the bridge organization briefly, but others were involved for many years and it is these long-established men whose biographies are particularly revealing of the changing relationship between the bridge and the civic government.

In the late sixteenth century John Stow asserted that the rebuilding of the bridge in stone was a project initiated by Peter of Colechurch, a ‘priest and chaplaine’.10 Peter’s existence is well attested in contemporary records and his seals show that he identified himself as a priest while acting on behalf of the bridge.11 Stow suggested that one of Peter’s first achievements was the establishment of a bridge chapel, and once it was completed ‘many charitable men gaue lands, tenements, or summes of money towards maintenance thereof ’, which surviving records verify.12 Other aspects of Stow’s account are more difficult to confirm. Stow credited the king, a cardinal and the archbishop of Canterbury with offering important financial support. Moreover, Peter of Colechurch died before the bridge was finished and Stow suggested that ‘worthy Marchants of London, Serle Mercer, William Almaine, and Benedict Botewrite’ then completed the work.13 Thus, Stow shared credit for the construction of the bridge between the crown, the Church and the leading men of London, but he contended that even before the project was completed, responsibility for the direction of the bridge had passed to several leading Londoners. However, Stow’s reference to Serlo, William and Benedict, who participated in the affairs of the bridge in the 1220s and 1230s (Table 10.1), well after the death of Peter of Colechurch, suggests that Stow may not have appreciated the full sequence of events.

Building on the work of previous generations of historians, modern scholars have offered a number of interpretations of the events of the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries.14 Derek Keene noted that ‘the bridge project and its estate originated in a period when the institutional expression of the citizens’ collective authority was at an early stage’ and that consequently, he argued, ‘the enterprise became an independent trust rather than an integral element of civic administration’.15 If, as an ‘independent trust’, it was not an ‘element of civic administration’, what form did the ‘trust’ take? Christopher Brooke emphasized that the leading figure in the bridge project was Peter ‘vicar of St. Mary Colechurch’, but added that Londoners were involved through ‘a series of confraternities and guilds’ whose members then raised money ‘as a pious and charitable work’.16 As Brooke suggested, the way in which the bridge project was organized in its early years was probably indebted to charitable models, in keeping with the existing tradition in England of treating the building of bridges as an act of piety.17 Indeed, on the Continent at this time, and particularly in the south of France, charitable organizations were busy building bridges, so there were contemporary parallels.18 The bridge was probably established as a charitable and ‘independent trust’, but acknowledging this leaves historians of the thirteenth century to establish when the bridge was brought under the authority of the civic government.

Chronicles, judicial materials and royal records offer evidence on the governance of the bridge in the early to mid thirteenth centuries, but the most important sources are documents preserved in the archives of the bridge itself.19 These records are largely concerned with property because, from an early date, the bridge acquired land that served as an endowment. Indeed, some of the earliest properties were located on the bridge itself. In 1202 the crown proposed that buildings should be placed on the bridge to provide rents.20 In 1212 a fire swept through Southwark and onto the bridge, reaching as far as the centrally located bridge chapel, which suggests that the bridge was lined with houses and shops by this date.21 When in 1244 royal justices asked the Londoners by what warrant they had built on the bridge, they responded that the structures had been erected by the wardens and brethren of the bridge with the alms of the people of London. They asserted that the structures represented an improvement to the fabric because they allowed people to move across the causeway ‘securely and boldly’ and helped to fund the maintenance of the bridge.22 Properties on the bridge were part of the original nucleus of the bridge’s endowment, but the bridge also acquired lands in other parts of London, Southwark and in the surrounding region. The bridge kept records relating to its properties, particularly the deeds documenting their acquisition, and those records can identify men who acted on behalf of the bridge organization.

When Peter of Colechurch died in 1205, he was buried in the bridge chapel.23 Stow suggested that, following Peter of Colechurch’s death, a group of ‘merchants’ from London took charge of the project, but contemporary records indicate that these were men who could personify the bridge’s charitable status (Table 10.1). King John intervened in the appointment of Peter’s successor and directed that a royal almoner, known as brother Wace, and a ‘law-worthy man’ of London, selected in consultation with the mayor of London, should be granted responsibility for the bridge.24 Brother Wace took charge of the administration of the bridge’s endowment25 and although the identity of Wace’s colleague, if indeed one was appointed, is obscure, it is clear that in subsequent years the practice of having two or more men share responsibility for administering the bridge became conventional. Brother Wace’s immediate successors seem to have been either chaplains or members of the bridge’s own brotherhood. Richard of Muntfichet, in a document dated 1212–4, handed over a mill to ‘London Bridge and the brethren’.26 These men are difficult to identify, but a deed dated 1213 tersely remarked that ‘Martin and Geoffrey’ entered into an understanding with Henry de Arches and Margaret his wife concerning land in the parish of All Hallows Barking.27 The absence of second names suggests that they were members of the brotherhood rather than merchants of London. Thus, responsibility for the bridge probably did not shift directly from Peter of Colechurch to ‘worthy Marchants of London’ but first came to rest in the hands of the ‘brotherhood’ that had taken shape during Peter’s lifetime and was devoted to serving the bridge.

The brotherhood admitted both men and women. Three mid thirteenth-century agreements recording the reception of married couples into the brotherhood survive.28 Each couple made a payment to the bridge, which suggests that the agreements were corrodies.29 In 1255–6 the brethren admitted Thomas Iuvene and Isabel his wife.30 They were to receive a servant, living space within the ‘enclosure’ (clausus) and an allowance of one mark a year for clothing; and they agreed to be ‘faithful, honest and reverent’ as is customary among ‘religious men’. In return, they donated funds to the bridge which were used to purchase rents. In 1250–1 John, son of Matthew and his wife Juliana, joined the brotherhood on similar terms.31 They received a chamber within the ‘enclosure’, a servant and 1 mark for their clothing; and they were asked to be faithful, honest and reverent to the wardens and the brethren. In 1277 Henry ‘in-the-lane’ and Isabel his wife gave 100 marks to the bridge and in return, for the term of their lives, they received two chambers and a solar located in the ‘enclosure’.32 Furthermore, each day they were also provided with food and drink in the same proportions as were given to two chaplains. Although these couples may not have been typical of the brotherhood’s membership, all three agreements point to the existence of a collection of houses where the brothers and sisters lived in a communal fashion.

Some of the brothers may have been men who could take an active role in managing the bridge’s estates. In 1280 Martin the chaplain, John the clerk and the bridge wardens granted John of Brokele, bridge brother, lands owned by the bridge in Lewisham and Greenwich ‘for his sustenance’. A detailed agreement was drawn up that listed the value of the estate and an inventory of the contents.33 The inventory included a variety of tools and farm implements as well as geese, hens, three horses and six oxen. There were also a mill and seventy-six acres of land sown with corn, rye, oats, peas, vetch, beans and barley. The agreement stipulated that John of Brokele had to pay to the bridge 50s a year in rent, but he failed as an estate manager and in June 1297–8 he was asked to return custody of the estate.34 At that time it was noted that brother John was not only behind in his rent payments, but that stock and implements had disappeared and he had failed adequately to maintain the mill, woods, hedges and houses. The same day, another bridge brother, John of Lewisham, was sworn as the new ‘baillif ’ of the estate.35 Although some brothers may have managed estates, perhaps they were not all suited to this work.

A more common role for bridge brothers was to participate in fundraising. In 1253, for instance, the brethren of the bridge were granted protection for ‘their messengers, collecting alms for the maintenance of themselves and the bridge’.36 Their success in soliciting donations is underlined by the dedication clauses of the thirteenth-century deeds. Between 1228 and c.1238, for example, Matilda and her husband Alexander Palmer confirmed a gift to the bridge in a deed that noted the gift was for ‘God and the blessed Thomas the Martyr and London Bridge and the Brothers and Sisters there serving God’.37 In 1235–36, the executors of Roger le Duc gave 21s 8d of rent from property on the bridge to the work of London Bridge and the ‘brothers of the same Bridge’ for the benefit of Roger’s soul.38 In 1237–8 Albin son of Alan noted that he had paid 1 mark of silver to the ‘brothers and sisters’ of the bridge.39 In 1271 William Blund of Lewisham and Berta his wife confirmed land to the ‘brothers and sisters of the Bridge House of London’; and brother John was recorded as giving William and Berta 13s 2d.40 Many of the dedication clauses in the early thirteenth-century deeds emphasized the religious and charitable character of the bridge, acknowledging God, the bridge’s patron saint Thomas Becket and the prominence of the bridge brothers and sisters. These dedication clauses demonstrate that members of the bridge brotherhood played an important public role by representing the organization to the Londoners.

Another focal point of the bridge organization was the bridge chapel, where Peter of Colechurch was apparently buried, for it served as a centre for both the religious life of the bridge and the administration of the endowment. When Martin, son of Robert Dun, gave ‘God and the blessed Thomas the Martyr and London Bridge’ a gift of 10d of rent in c.1235, the deed specified that the rent was to be paid on the altar of the Blessed Thomas ‘on London Bridge’.41 In return for prayers in the bridge chapel, in 1244–8 John Everard released the bridge from an obligation.42 The chapel was also used as a venue for the confirmation of agreements well into the fourteenth century.43 At least two chaplains regularly served in the chapel: Godefrid and Simon were mentioned in 1220–1; William of Hereford and Godard in c.1240–56; and Godard and Richard in the mid thirteenth century.44 In the later thirteenth century records mentioned the chaplains James of St. Magnus, Martin and William Wrethernghey, who all participated in managing the bridge’s properties (Table 10.1). Throughout the thirteenth century the chapel was an important place for the administration of the bridge’s endowment. Moreover, it had an important complement of staff, which included several chaplains, some of whom contributed to the administration of the endowment. Peter of Colechurch’s legacy included not only the bridge and an endowment to support its maintenance, but also an organization. This organization was composed of men and women who, as chaplains or members of a brotherhood, could personify the bridge’s charitable status. They lived in a communal fashion in a complex of buildings on the south bank of the Thames, in Southwark, near the bridgehead. They raised funds for the bridge but they also contributed to the administration of its endowment.

Early in the reign of Henry III the organization was augmented by a pair of laymen who formed an additional layer of authority within the bridge organization. In 1220–1 Henry of St. Albans and Robert of Winchester, ‘proctors of London Bridge’, and Arnald the chaplain made a grant confirmed with the ‘consent’ of the ‘brethren’.45 As such records suggest, the laymen did not take over from the chaplains and brothers their role in administering the endowment, but rather shared it with them.46 This is underlined by cases in which the lay bridge officials appeared in records of exchanges not as parties but rather as witnesses. For example, in c.1225 Warin de Wadessele made a grant to ‘God, the blessed Thomas the martyr, and London Bridge’ and the witnesses included Serlo the Mercer, ‘warden’ of the bridge.47 While his title indicates that he was present in an official capacity, Serlo’s role as a witness rather than a party to the agreement suggests that he was there to offer support and oversight but had not supplanted the chaplains and brethren as sole administrator of the bridge.

More than thirty men are known to have contributed to the administration of the bridge’s endowment during the thirteenth century, including members of the brotherhood, chaplains and laymen (Table 10.1). In the 1220s and 1230s perhaps the most important laymen were Henry de St. Albans, Serlo the Mercer and Michael Tovy. They always worked in partnership with other men, but their sequential terms of office and contrasting careers offer an indication of how the organization changed during their terms of office.

Henry of St. Albans’s origins are obscure, but he was a member of the civic community. Henry had property in the parish of St. Martin Vintry.48 He had a son named William and his daughter Margery married John Viel (sheriff, 1218–20).49 Henry and Serlo served together as sheriffs of London in 1206–7 and then both pursued mercantile careers. In 1207 Henry was one of several Londoners who sold wine to the crown.50 In subsequent years references in royal records show that he was involved in shipping and the trade in wine and wool.51 Through this work he developed a close relationship with the crown, which led to his appointment in 1222 as keeper of the exchange of London. This was an important royal financial office, which he retained until 1226.52 In these years he also participated in a number of transactions on behalf of the bridge and frequently appeared in witness lists of bridge deeds, where he was consistently assigned a place of precedence.53 He then disappeared from the witness lists of transactions involving the bridge but he remained active in London through the 1230s.54 Henry’s career illustrates the complex affiliations of prominent Londoners in the early thirteenth century. He served as a sheriff and his daughter was married to another sheriff, but Henry pursued connections with King John and his son and successor, Henry III. As keeper of the exchange he was accountable to the crown and thus a royal officer, but he also offered financial services to the crown and can be glimpsed acting on the king’s behalf in more informal capacities in other periods. How he became involved in the bridge organization is obscure, but his simultaneous service in the royal exchange and the bridge suggests that within the bridge organization he may have acted as an informal representative of the king.

Serlo the Mercer has been described as the ‘archetype of the late twelfth-century mercer who made good’.55 He is first mentioned in charters dated (through internal evidence) between c.1190 and c.1200.56 He was then known as Serlo son of Hugh of Kent and he owned a large block of property, described in the records as his ‘fee’, in the parish of St. Martin Outwich, which lay in the north-east section of the city. He served with Henry of St. Albans as sheriff of London in 1206. Like Henry, Serlo was involved in mercantile activity. In 1215 King John’s barons revolted and took control of London.57 Caught in the midst of this conflict, the Londoners decided they needed new leadership and Serlo the Mercer became mayor.58 Serving as mayor at this point involved keeping peace in the city, but it also posed financial challenges, as the Londoners had made a substantial loan to the French prince, Louis, who had attempted to oust King John, and Serlo, along with Henry of St. Albans, played a role in organizing Louis’s repayment.59 When the immediate crisis passed Serlo stepped down as mayor, but he was reappointed in 1217 and served until 1222. Matthew Paris would later describe him, albeit in connection with a crisis in 1222, as a ‘vir prudens et pacificus’ [a prudent and peaceable man].60 However, like Henry of St. Albans, there is little evidence that he served as an alderman, so he, too, may not have been fully integrated into the close-knit group of men who dominated local government in the city. During his second term as mayor he witnessed a substantial number of transactions involving the bridge, which suggests that he worked with Henry of St. Albans to oversee the affairs of the bridge.61 When Serlo resigned from the mayoralty, he then took a more formal role within the bridge organization which lasted until the mid 1230s and involved offering oversight and contributing to administration.62 Henry of St. Albans and Serlo the Mercer might seem to have had contrasting careers, as one focused on service to the crown and the other to the civic community, but their work on the bridge suggests that the bridge organization remained an area of co-operation between the city and the king.63 However, Henry was followed by Serlo and Serlo then served with the bridge organization for many years, which suggests that it was the civic community that was more determined to influence the affairs of the bridge in the 1220s and 1230s.

After Serlo’s departure, Michael Tovy assumed his role in the bridge organization.64 Tovy’s origins are difficult to establish, but he had interests in Kent which suggest ties to that region.65 In London he was known as a goldsmith but he was also involved in the wine trade and perhaps offered financial services.66 Tovy certainly had an exceptional career in civic politics. He served for a term as sheriff in 1240–1, not long after he acquired an aldermanry, and in 1244 he was appointed mayor.67 Arnold son of Thedmar suggested that he was a populist and that he courted controversy by attempting to push through the re-election of Nicholas Bat to a second consecutive term in the office of sheriff in 1245.68 Tovy’s proposal aroused resistance from some of the aldermen, but they were unable to block his motion because of his popular support.69 The crown intervened and not only forced the removal of Nicholas Bat from office but also insisted that Tovy be replaced as mayor. A few years later Tovy was reappointed mayor and he served two more terms, from 1247 to 1249. Throughout these years Tovy was also active within the bridge organization, where he both offered oversight and participated in administration. For example, among the records from the year 1248–9 a deed refers to a quitclaim granted to the ‘master and brethren’ of London Bridge which Tovy witnessed as mayor.70 Another shows that William of Welcomestowe and Margaret his wife confirmed some land to ‘London Bridge, and the brothers and proctors’ and the witnesses to the exchange included Michael Tovy as mayor.71 However, another record notes that Imbert, prior of Bermondsey, granted land to Michael Tovy, ‘warden of London Bridge’, for the upkeep of the bridge.72 The mid thirteenth-century records suggest that Michael Tovy had a hand in managing the endowment, even as he continued to support and oversee the chaplains and brethren administering the bridge’s assets.

The participation of Henry of St. Albans, Serlo the Mercer and Michael Tovy in the governance of the bridge testifies to the increasing role of lay Londoners within the organization. Henry of St. Albans and Serlo the Mercer, while contemporaries, chose different paths of advancement. Henry was valued by the crown for his financial and administrative abilities and was associated with the bridge while he served in a royal office. Serlo had considerable influence in the civic community, although he does not seem to have served as alderman; and he proved, through several terms as mayor, that he could work with the crown. Serlo’s formal involvement in the affairs of the bridge started shortly after he left civic politics. Michael Tovy, by contrast, was probably a young man when he first appeared as a bridge official. Tovy possessed considerable civic political ambition and during his association with the bridge he scaled the rungs of the civic political ladder, serving as sheriff, alderman and mayor. That Tovy, as mayor, combined posts in both organizations might be taken as evidence that the bridge had been formally brought under the authority of the civic government, but rather it points in the opposite direction, as it is difficult to imagine Tovy submitting to an audit administered by either the crown or the civic government (see below). Tovy’s career thus shows that, by the mid thirteenth century, the leading men of London were interested in directing the administration of the bridge’s endowment, but it also shows they did not yet have the capacity to do this through agents, who could be appointed by the civic government and then held accountable by the government.

Before examining the events of the third quarter of the thirteenth century, it is useful to touch on the history of the leper hospital of St. Giles in the Fields, Holborn, as it helps to establish the political context in which charitable organizations in the city operated. The hospital was founded by Queen Matilda (d. 1118), wife of Henry I, but in the following years the hospital received significant new donations from Londoners that increased the endowment. Londoners were keen to ensure that the hospital was well funded, but also well administered. Like the bridge, the hospital was a twelfth-century foundation and around the time of Magna Carta, as with the bridge organization, there is evidence that leading members of London’s mercantile community were becoming involved in the governance of the hospital. For example, a deed from this era noted that the proctor of the hospital, William de Cokefield, together with the ‘brothers and sisters’ of the hospital, acted with the ‘consent’ of Thomas de Haverhill and William Hardel, ‘wardens’ of the hospital.73 Both ‘wardens’ were important and influential men in civic politics: Thomas de Haverhill was, at about this time, serving as an alderman in the civic government, and William Hardel served briefly as mayor, following Serlo the Mercer. In the mid thirteenth century a number of mayors of London participated in the oversight of the administration of the hospital’s endowment.74 However, as in the case of the bridge the participation of men who also served as mayors did not mean that the hospital had become a department of the civic government. When, in the later thirteenth century, it became politically important to define more clearly the respective spheres of authority of the king and the civic government, they fought over the selection of lay Londoners as ‘wardens’ of the hospital and the king prevailed.75 In the fourteenth century the civic authorities continued to put forward their version of events, arguing that the hospital had been founded by a Londoner who provided that ‘two persons of the City, elected by the mayor and aldermen, should be wardens … to see that the issues of the said lands, tenements, and rents were properly expended for the benefit of the said lepers’.76 The fourteenth-century civic authorities’ claims about the origins of the hospital were ill-founded, but they are important because they show that by the fourteenth century the civic government wanted to exercise oversight of the hospital through a pair of elected wardens and the king denied them this privilege. The case of the leper hospital shows that in the later thirteenth century the crown regarded oversight of charitable organization in the city as a privilege which it was not prepared to concede unquestioningly to the civic government. The dispute in the late thirteenth century between the civic authorities and the crown over the appointment of wardens for the bridge was thus not an isolated conflict but part of a broader struggle to define the scope of the civic government’s authority in the city.

The dispute between the king and the civic government over the appointment of wardens of London Bridge broke out in earnest in the 1260s. Following Michael Tovy’s retirement, Godard the chaplain took the leading role in administering its endowment. Godard was active in the bridge organization during Tovy’s tenure of office; and when Tovy left, Godard began conducting transactions on behalf of the bridge, with oversight from lay wardens.77 However, following the rebellion of 1263–5 the Londoners submitted to the king.78 As part of a campaign to assert his authority over the city, Henry III handed the bridge to Queen Eleanor. The queen then placed the bridge in the custody of the hospital of St. Katherine by the Tower, whose masters she appointed.79 The hospital of St. Katherine was instructed to hold the wardenship of the bridge and ‘apply the rents, tenements and other things belonging thereto within and without the city to the repair of the bridge’.80 In practice, the hospital ensured that the bridge was operated by men who would obey the queen, such as Thomas Chelke, the master of St. Katherine’s hospital, and William son of Richard, who was a notable royalist.81 By 1271 they had been succeeded by Stephen of Fulborn and James of St. Magnus. Stephen was Thomas’s successor as master of St. Katherine’s hospital, but he also held many other positions, including by 1273 bishop of Waterford and by 1274 treasurer of Ireland.82 In contrast to Stephen, James of St. Magnus’s first loyalty was probably to the bridge organization.83 As he had considerably less standing than Stephen, he may have had the day-to-day responsibility for administering the bridge. However, Margaret Howell has argued that in financial affairs Eleanor proved that she was determined to obtain as much income as possible and ‘condoned ruthless exploitation of estates in her wardship’.84 Indeed, under her direction the bridge was operated in a way which suited her rather than the Londoners.

Setting responsibility for the bridge in the hands of a hospital only cloaked the queen’s authority over the bridge. When the bridge officials came to terms with the representatives of the church of St. Peter of Ghent, the deed noted that in the event of a dispute the issue would be settled in the presence of Queen Eleanor or other ‘worthy men’.85 An agreement of 1271 notes that Stephen of Fulborn acted on the ‘command’ of the queen.86 The same year, James of St. Magnus ‘and the masters and brothers’ of the bridge acted with the consent of the queen in assigning a shop in the parish of St. Magnus the Martyr to Robert Lambyn.87 The treatment of the chantry of Richard Cook perhaps illustrates the type of transactions that were conducted during the queen’s oversight of the bridge. The will of Cook, proved in the hustings court on 2 May 1269, provided that houses in the parish of Colechurch would be transferred to the bridge to support a chantry in the bridge chapel.88 Queen Eleanor, however, soon sold the property to the Friars of the Sack in return for 60 marks and made them responsible for the chantry in a transaction described as being conducted with the ‘assent and will of the Friar Stephen of Fulborn … and the rest of the brethren’ of the Bridge House.89 The Friars of the Sack in turn transferred the properties to Robert FitzWalter, the lord of Baynard’s Castle.90 All these transactions benefited the participants at the expense of the long-term interests of the bridge by diminishing the resources supporting Richard Cook’s chantry.91 Had the queen, through her agents, ensured that the bridge was well maintained, then perhaps the Londoners would have tolerated her administration. Instead, the bridge’s fabric was neglected, which generated discontent.

Arnold son of Thedmar captured the tenor of public opinion when he remarked in his chronicle that the officials appointed by the queen ‘collected all issues of the rents and lands of the said bridge, converting the same to I know not what uses, but expending nothing whatever upon the repairs of the said bridge’.92 In 1274–5 the crown gave local juries the means to comment on local government and they complained about how the bridge was managed.93 Maintenance work was not being carried out, leaving the structure in an increasingly precarious state. If a section of the bridge had collapsed, it would have had to be reconstructed, which would not only have been expensive and inconvenient for the Londoners but would have broken a key link in the transport network and disrupted the economy of the entire region. The queen, through her appointees, had exploited the bridge’s endowment for almost a decade, but by 1275 the crown probably judged that it was financially risky and politically costly to continue. An entry in the husting rolls recorded that in May 1275 the king ‘restored the bridge’ to the city ‘at the instance and by the diligent persistence of mayor Gregory of Rokesle’.94 However, the king did not hand control over the bridge back to the bridge brothers and the chaplains but rather to the civic government, which was determined that for the foreseeable future it would directly administer the bridge’s endowment.

The civic government used the opportunity offered by the ‘restoration’ to assert its own authority over the bridge. Perhaps this was partly motivated by a desire to make it more difficult for the king to interfere in the affairs of the bridge in the future, but it also helped to restore the reputation of the bridge organization in the eyes of the civic community. People wanted to know the bridge would be well-administered, but they also wanted a say in the process, so the civic government organized an election, involving representatives from the wards, to appoint bridge wardens accountable to the civic government. Gregory of Rokesle himself, who was then serving as mayor, together with the alderman of Langbourn ward, Nicholas of Winchester, were the first bridge wardens following the ‘restoration’ (Table 10.1). However, at the end of their term of office the king asked them to submit to an audit. Gregory argued that if he submitted to an audit, even if it was only with regard to his actions as a bridge official, it risked undermining his authority as mayor.95 Gregory and Nicholas were then succeeded by men who did not already hold important civic offices. The decline in the standing of the bridge wardens may have been partly due to the threat of audits, which discouraged the city’s leading men from serving in the office, but it is also important to note that between 1285 and 1298 the governance of the city was directed not by its own mayor, but rather by a royal warden appointed by the king.96 Consequently, towards the end of the century the bridge was dependent on the civic government, but the civic government was directed by a royal appointee. These appointees were, perhaps, not interested in allowing men who already held important posts in the civic government to accumulate further power. Nonetheless, following the restoration of the bridge the civic government gained more authority over the bridge, even if the civic government itself remained vulnerable to royal interference.

Although the civic government changed how the bridge organization was directed and handled funds, it also worked, with some encouragement from the crown, to restore the bridge’s finances. The civic government found the bridge new sources of revenue. In February 1282 the crown granted Rokesle, as the mayor of London, permission ‘to associate with himself two or three discreet and lawful citizens of London’ and collect tolls at the bridge for its repair ‘until the next Parliament after Easter’.97 In July 1282 the grant was renewed for a further three years.98 By 1282 surviving enrolments of debts preserved in the city’s records indicate that the civic authorities were encouraging the parties to these agreements to direct penalties payable for breaches of contract to the bridge.99 A more significant addition to the revenue of the bridge were the proceeds from the operation of the stocks market.100 The market had only recently been created as part of an attempt to reorganize trading in the city and it was intended to provide a covered location for the buying and selling of fish. During the mayoralty of Henry le Waleys the civic authorities decided that the substantial rents paid by the fishmongers for the use of the market should be devoted to the bridge.101 All these sources of revenue were important, but the financial foundations of the organization remained the endowment and charitable donations, which the chaplains and brethren continued to collect. In January 1281 the crown granted its protection to ‘the keepers of London Bridge, or their messengers’, who were ‘collecting alms throughout the realm for the repair of the bridge which has fallen into a ruinous state’.102 In 1297 William son of Henry Boydin gave ‘London Bridge and the brothers of that place and their successors’ one penny of rent ‘in perpetual alms’.103 Studies of donations recorded in the husting wills suggest that a high-water mark of the popularity of the bridge as a recipient of donations was reached in the early fourteenth century. Harry Miskimin found that in the first decade of the century almost eighty per cent of wills enrolled in the husting court offered donations to the bridge.104 Nonetheless, the bridge was now firmly under the oversight of the civic government. References to agreements reached between grantors and a bridge chaplain at the ‘instance’ of the bridge wardens imply that real authority in the organization now rested firmly in the hands of the civic government’s representatives. John son of John Jukel, for example, confirmed land to Martin the chaplain and the brethren of the bridge at the ‘instance’ of Thomas Cros and Edmund Horn, wardens of the bridge.105 In 1287 William, son of William le Hwyte of Lewisham, at the ‘instance’ of the bridge wardens, likewise transferred a rent to Martin the chaplain.106 Although the nature of the bridge organization may have been clear to Londoners, to outsiders it still seemed to be a charitable enterprise. In 1295 the abbot of St. John’s Colchester was collecting a tax on the Church granted in aid of the Holy Land and he asserted that London Bridge should contribute.107 However, the bridge wardens successfully argued that it should not contribute on the grounds that they were laymen. By 1295 the bridge organization still had features of a charitable trust but its finances were firmly under the control of laymen appointed by the civic government.

Peter of Colechurch’s legacy included both the bridge itself and an organization devoted to its maintenance, and change in that organization during the thirteenth century can be traced through its leadership. In the early years of the thirteenth century, lay participation in the governance of the bridge proved compatible with the bridge’s charitable mission and its independent status. Leading Londoners such as Henry of St. Albans, Serlo the Mercer and Michael Tovy offered oversight and advice, but they also had a hand in managing the endowment. However, these men were not appointed by the civic government, which at this point in its history was itself still in the process of consolidating its own position as the principal civic political institution. Then the bridge, because of its importance to the civic community and its valuable endowment, was, in the mid thirteenth century, dragged into the struggle between the crown and civic government for authority in London. In 1265 the crown took control of the bridge, but it proved unable to operate the bridge in the long term, so in 1275 it gave the bridge to the city, which then incorporated it into the framework of the civic government. Remarkably, the assertion of civic control over the bridge did not erase its charitable status. What had been two distinct organizations with contrasting approaches to organizing the people of London towards common goals were brought together. As its relationship with London Bridge demonstrates, by the end of the thirteenth century the city of London, as an institution of government, had grown dramatically in power, influence and complexity. Londoners became willing to permit the civic government to take responsibility not only for such things as operating courts, organizing the watch and collecting taxes, which were its traditional roles, but also for overseeing the administration of an endowment that provided the Londoners with an amenity that improved their lives and remembered past benefactors.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Chapter 10 (223-244) from Medieval Londoners: Essays to Mark the Eightieth Birthday of Caroline M. Barron, edited by Elizabeth A. New and Christian Steer (University of London Press, 10.31.2019), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.