Questioning the presumption that children were ignored or downplayed in the Middle Ages.

By Dr. Jean E. Jost

Professor Emerita of English

Bradley University

Introduction

“I could never have thought that God having divided me from my son, [and having him] pass from this life to another could have been for me and is such a grievous knife.”2

With this pitiful lamentation, Giovanni Morelli bemoans the loss of his ten-year-old son in 1406.1 Another grieving parent decries “It pleased God to call to himself the said Lucha on the eleventh day of August 1390; let us hope he has received him with his blessing and with my own.”3 Similarly, the expression of anguish by the grieving father of three-year-old Falchetta Rinucci in 1509 suggests his sincere sorrow at the great loss of his daughter as he laments “I am certain that she has flown to heaven . . . [and pray that] this saintly little dove will pray Divine goodness and his sweet Mother for us.”4 Such examples of parental devotion confirm one side of the controversy over the actual role of children in medieval society. The long-standing view, originally developed by Philippe Aries,5 that children were undervalued, unappreciated, and untended has recently been challenged by the discovery of contradictory documents such as these testimonials, heartfelt tombstone engravings, and letters.

Recent historical and literary critics have thus questioned the presumption that children have been ignored or downplayed in life as well as in literature of the Middle Ages. They contend that, contrary to popular belief, children have in fact played a rather significant role in their parents’ lives, and in the plots of English literature. While it is true that abandonment, suspicious crib-death, and at least some infanticide indicate conflicting attitudes, especially in the more poverty-stricken areas of society, Hans-Werner Goetz believes the notion that children were regularly ignored or neglected is unfounded. He maintains that

the previously held view that children were generally perceived to be a burden and little loved has been refuted. Burial with tombstones and the preserved letters of consolation written to parents whose children had died contradict such a theory…. On the whole, there can be little doubt that children were treated lovingly … 6

Barbara Hanawalt concurs, remarking

We who study medieval society… have neglected the two-way relationship between parents and children, and we have overlooked entirely the importance of community in raising and protecting children . . . [our studies have been] limited to cultural expressions of love of children rather than to the discipline, training, and oversight [of] the community. The culture of nurturing was continually articulated in medieval sources ranging from coroners’ inquests to the Prioress’s Tale.7

Hanawalt’s comments alert us to the need to examine more fully those familial assumptions of the last century. John Boswell furthers Hanawalt’s view, noting that

It has been argued in the past few decades that there was no concept of “childhood in premodern Europe, and that parent-child relations in previous ages were for this and other reasons (such as the high mortality rate) inherently and categorically different from those in the modern West. . . . But such theories do not account well for the available evidence There was no general absence of tender feelings for children as special beings among any premodern European peoples.8

Allison P. Coudert’s article “Educating Girls in Early Modern Europe and America” in this volume posits the same of the Early Modern period, noting, “In these early modern works [such as Rousseau’s Emile, Coler’s Haussbuch, and Montaigne’s “On the Education of Children”] one finds the same concern for the health and well-being of children . . . the very real affection and concern the majority of parents had for their children”—and this despite a rather harsh form of education of children, especially of girls, in the wake of the revised family ideology triggered by the Protestant Reformation.

But one can understand why Aries suspected a certain distancing between parents and children, given the harsh economic conditions, the exorbitant mortality rate, and the lack of available social history or other concrete written evidence. And no doubt both situations attained: children were both loved and prized and also distanced and abused. David Graizbord’s article “Converso Children Under the Inquisitorial Microscope in the Seventeenth Century: What May the Sources Tell us about Their Lives?” in this volume points to the ambiguous situation in seventeenth-century Spain where children were manipulated by the Inquisition into implicating their parents: “By alleging that their parents and relatives had tried to incorporate them in a life of Judaizing, the youths sought to settle scores and claim a measure of personal independence.”9 At least some measure of distance or disaffection must be assumed from such a statement, even if it is the normal phenomenon of children growing into maturity. Nor did the Holy Office respect the status of child, using “a form of inquisitorial manipulation so extreme that it resulted in the radical alteration of his legal, religious and hence social status. Such were the perils of being considered a ‘child’ by the Holy Office.” Furthermore, Klapisch-Zuber concludes that “Outside these favored milieus in which parents knew how to express their hopes and their suffering, direct testimony on the relations between parents and children is rare.”10 In 1990, Jacques Le Goff objected to Aries view, wisely moderating his previous position “that Philippe Aries was correct in affirming that in medieval Europe the child was not a highly valued object—which did not prevent parents from loving their children, but loving them particularly in view of the adults that they would become and that it was desirable that they become in the last possible time.”11 Confirming this final premise, Goetz claims, “By the tenth century at the latest, small children were considered full-fledged members of society,”12 thus shortening the period of complete nurture and protection, and perhaps thereby diminishing significance of the concept of childhood. In considering the importance of this time in life, what, then, constitutes “childhood”? As Boswell notes,

“Child” is in itself not an uncomplicated term. Among ancient and modern writers, conceptions of “childhood” have varied widely, posing considerable lexical problems for investigators. Even the bases of distinction change: sometimes the root concept arises from chronological boundaries (to age twenty-one, to age seven, etc.), sometimes from associated aspects such as innocence, dependency, mental incapacity, or youthful appearance According to [Isidore of Seville] up to 6 years constituted infancy; 7 to 13, childhood; 14 to 27, adolescence; 28 to 48, youth; 49 to 76 maturity (senectus); and 77 to death, old age.13

More recently, MacEdward Leach14 has considered the period of minority to extend to age twenty, or to an unspecified age of physical or mental competence. Peter Fleming’s 2001 Family and Household in Medieval England concurs with Boswell, as well as the eighth-century Isidore,

Medieval theorists divided childhood into three parts: infantia, from birth to the age of seven; pueritia, between the ages of seven and 14, and adolescentia, from 14 to the age of majority, which was increasingly regarded as 21. The common law recognized 21 as the age at which males holding by military tenures could enter their estates and administer them independent of parents or guardians. . . for society in general the defining point came when the young person was married and began to live with his or her spouse as husband and wife.15

Therefore, within the context of this discussion, any person who has not reached full adulthood or taken a spouse may be called a “child”-one still maturing physically, mentally, or emotionally. The span of childhood thus encompasses a flexible time period, and within this time, the child is slowly progressing from stage to stage as he or she moves into maturity.

Hence, within any given literary context—short tale, narrative poem, or long narrative—the maturation of a hero through social acculturation within family is best done within a protracted, episodic narrative, thus allowing sufficient germinating time for both the child’s and the story’s development, simultaneously confirming the medieval audience in its society. According to E. J. Graff, the three developments, of child, story, and audience, are coextensive throughout most literature. The family, furthermore, is the means of nurturing and bringing to fulfillment the human offspring, the author’s literary one, and the audience’s cognitive one. And while the traditional European family may not have always maintained close family ties,16 Middle English tales regularly depict emotional family bonds and touching moments at the heart of the plot. Inevitably, a child is at the core. While certain children, such as the little girl in Chaucer’s Merchant’s Tale may seem to function minimally, or stand as representatives of “the child,” others are crucial for the development of plot and theme. In fact, children in Middle English literature—fiction, drama, and poetry—often play a particularly significant role in the episodic, action-oriented events of extensive tales: they effect the story’s narrative turns or outcome, sometimes evolving into its heroes, either as children or budding adults. This study seeks to dispel the notion that children hold a minimal literary role within Middle English literature by examining their effect, specifically within the family situation, on the outcomes of several Middle English narratives. They may be aligned with or at odds with their family members, but in any event, they are not insignificant. Within these Middle English narratives, the growth and blossoming of child, story, and audience awareness are effected through the agency of family, and by means of the narrative.

Perhaps medieval authors include children in their literary works to evoke emotion, most often using them as actual or potential victims as well as to further narrative action. Two primary emotional paradigms overshadow the others, that of the innocent victim, seriously hurt or killed in tragic circumstances, and that of reclaimed victim, saved from destruction at the eleventh hour in a comic redemption. In both cases, of tragedy and its redemption, the pity and fear of the Greek drama, are the cathartic means of audience release.

Representing these binary oppositions are the Cycle Plays’ depiction of the “Slaughter of the Innocents” falling into tragic demise, physical if not spiritual death on the one hand, and the near tragic “Abraham and Isaac” salvation story heralding victory on the other; both elicit pathos though the children’s innocence and the gruesome circumstances. Appropriately, drama embodies both paradigms as a medium conducive to, and traditionally conveying emotion. Since the medieval treatment of children is overwhelmingly emotional, even pa-thetic—seeming to evoke pathos by their very presence—drama is a likely home for these emblems of doomed and redeemed victims. Other genres such as certain Chaucerian tales and the alliterative Morte Arthure poem, however, reinforce the themes of actual or near tragedy, with or without redemption. This discussion focuses on dramatic paradigms representing children in the Slaughter of the Innocents and Abraham and Isaac plays, and representation of other doomed or redeemed children in non-dramatic literature who exemplify these dramatic models.

Slaughter of the Innocents

“The Slaughter of the Innocents” ironically represents those lost children unredeemed from their fate, made to suffer needlessly, or mercilessly dispensed with. Unlike children in the Abraham-Isaac model who are at risk, threatened, and nearly sacrificed, these unfortunates are in fact slain. Their martyrdom, or their redemption in the next world, does not modify the victim paradigm. Sometimes their parents are the misguided perpetrators, or figure in the play as sorrowful victims of their children’s deaths.

Stage/costume directions for the eleventh- or twelfth-century Fleury Playbook containing the “Service for Representing the Slaughter of the Innocents” begins the play with “For the Slaughter of the Children let the Innocents be dressed in white stoles.”17 This symbol of their spotless nature free from sin makes their demise all the more devastating. The play’s crisis occurs when the man-at-arms advises Herod:

Determine, my lord, to vindicate your wrath, and, with sword’s point unsheathed, order that the boys be slain; and perchance among the slain will Christ be killed.

Herod delivering the sword to him saying:

My excellent man-at-arms, cause the boys to perish by the sword. (14-15)

While treatment of the actual murders are left to the individual producer, stage directions instruct: “Let the mothers, falling down, pray for the victims.” When Rachel enters, the directions indicate “standing over the boys let her mourn, falling at times to earth, saying:

Alas, tender babes, we see how your limbs have been mangled!

Alas, sweet children, murdered in a single frenzied attack!

Alas, one whom neither piety nor your tender age restrained!

Alas, wretched mothers, we who are compelled to see this!

Alas, we do we do now, why do we not submit to these things?

Alas, because no joys can erase our memories and sorrow,

For the sweet children are gone! (21-27)

This parent suffers from the evil perpetrated on her sons, like Abraham in the second paradigm who anguishes from the demand to slay his son; but in this play, Rachel’s pain satisfies no divine injunction. When the two comforters admonish her “Although you grieve, rejoice that you weep, / For, truly, your sons live blessed above the stars” (30-31), she rejects both their otherworldly perspective and their appeal to her vanity, that tears spoil her beauty. She retorts:

How shall I rejoice, while I see the lifeless limbs,

While thus I shall have been distressed to the depths of my heart?

Truly these boys will cause me to mourn endlessly.

Ο sadness! Ο the rejoicings of fathers and mothers changed

To mournful grief; pour forth weeping of tears. (32-36)

Furthermore, she is angry at their accusations, and their presumption:

Alas, alas, alas! Why do you find fault with me for having

poured forth tears uselessly,

When I have been deprived of my child

[who alone] would show concern for my poverty,

Who would not yield to enemies the narrow boundaries which Jacob

acquired for me,

And who was going to be of benefit to his stolid brethren, of whom

many, alas my sorrow, I have buried? (46-49)

The grieving mother, as well as the slaughtered babes, deserves audience sympathy. The combination of infanticide and her pain from that crime infuses the play with its stark horror. As Patricia Clare Ingham points out of Anglo-Saxon laments, “Female agency and power tend to be imagined as the opposite of pain and loss, an opposition that makes it difficult to see that a subject’s response to loss might constitute a set of significant activities, rather than an elaboration of passive victimhood.”18 Further, both Anglo-Saxon and later texts such as “The Slaughter of the Innocents” “suggest that women’s identification with family, her liminal position between cognate kin and exogamous alliance, marks women most intensely as the bearers of the ties to family, ties that must be mourned.”19 This mother experiences personal grief with political ramifications, but her strength of purpose and rational rhetoric prove she is an agent of sorrow and strength, not merely a victim. The choir of boys reinforce the message:

Ο Christ, Ο youth skilled in the greatest wars, how great an army do you gather for the Father, speaking prophetically to the people, drawing to you the souls of the departed, since you have so much compassion. (54)

These maternal emotive outpourings are as essential to the play, ensuring the audience response, as are the actual murders. In Aristotle’s schema, children are the subject, the material cause of maternal anguish, while the injunction to murder is the formal cause of the entire proceedings as Eva Parra Membrives suggests in her contribution to this volume, “Mutterliebe aus weiblicher Perspektive. Zur Bedeutung von Affektivität in Frau Avas Leben Jesu.”

Other Doomed Children: The Prioress’s Tale

Examples of the “Slaughter of the Innocents” model, in which children are often murdered by misguided or confused parents, include the Chaucerian Prioress’s Clergeon, the Physician’s Virginia, children of the Monk’s Hugelyn, and Mordred’s and Guinevere’s children ordered slain by Arthur. The fate of these doomed children casts a black cloud over literary medieval childhood.

However one feels about the Prioress, or even the innocence of her seven-year-old clergeon traipsing through the ghetto, insensitively intoning his hymns to taunt the Jews, no one wants him dead. Calculated audience empathy is the Prioress’s goal. The vulnerability of this fatherless lad devoted to the Virgin, his sincerity and youth, “For he so tendre was of age” (VII.524) are emotionally evocative. In “Victims or Martyrs: Children, Anti-Judaism, and the Stress of Change in Medieval England,” here in this volume, Diane Peters Auslander likewise notes the emotional value and appeal of children who “adorned with the aura of Christian sanctity and martyrdom, had the power to move whole communities of people… [generating] a powerful effect on people’s behavior” (#). His opposition, the evil-hearted Satanic Jews, are every bit as vile and violent as Herod’s messengers slaying the babes. Further, the Prioress claims a Jewish conspiracy, a plan not unlike Herod’s, to destroy that which threatens them, even if it be innocent little boys. She states, “Fro thennes forth the Jues han conspired/ This innocent out of this world to chace.”20 The gruesome details of the murderer who “kitte his throte, and in a pit hym caste Where as thise Jewes purgen hire entraille” (VII.571, 573) is reminiscent of the stark stage directions in the “Innocents” play. There “the children lie thrown on their backs” (after line 49), similarly degraded. The boy’s anxious mother, “with face pale of drede and bisy thoght… With moodres pitee in hir brest enclosed, / She gooth, as she were half out of hir mynde” (VII.589, 593-94) searching for her missing son. She “preyth pitously” with maternal agony, frustration, and the pain of loss similarly expressed by Rachel. The Prioress even explicitly associates the two, lamenting:

His mooder swownynge by his beere lay;

Unnethe myghte the peple that was theere

This newe Rachel brynge fro his beere. (VII.625-27)

The “pitous lamentacioun” (621) of the crowd echoes the sentiment of the narrator, and the expected audience response. Although the Prioress’s child is granted a brief and miraculous reprieve to sing with a cut throat until the Virgin’s grain is removed from his mouth, his demise is immanent. He is finally a lost victim, martyred for his song, unredeemed for his offense. Some might claim a greater supernatural victory for the lad, but on a natural, human level, his is a tragedy. Thus, a pattern amazingly similar to that of the holy innocents is discernable: dangerous circumstances, anguished mothers, pitying narrator, no remedy, vicious murder. The wailing and noisome crying of the mothers in “The Slaughter of the Innocents,” dramatically reinforced by their gestures, indicates their emotional involvement with their sons. In both cases, bereaved mothers’ sorrow reveal great bonding, and their children’s importance in their lives.

The Physician’s Tale

In Virginia’s situation, her anguished parent is the cause of her demise—through misguided or immoral perception. Anne Lancashire, in examining the “Physician’s Tale’s” sacrificial elements, points to Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac rehearsed throughout contemporaneous drama, lying behind the Chaucerian sacrifice.21 Her point is well taken, and her schema enlightening; my thesis, however, distin-guishes between attempted and actual sacrifice, thus placing Virginia in the Innocents category of physically unredeemed victims. Whereas the Prioress elicited sympathy for her clergeon by his tender age, the Physician does so by recounting Virginia’s beauty and goodness in more than seventy lines: “And if that excellent was hire beautee, / A thousand foold moore vertuous was she… As wel in goost as body chast was she” (VI.39-40, 43). Just as the Prioress claimed the fiend made his nest in the Jews’ hearts, so here that same “feend into [Apius’] herte ran” (VI.130), inspiring him to violate the young maid. He does so by secretly colluding with the churl Claudius whom he bribes into “hire conspiracie” (VI.149); as the Jews conspired to slay the boy, so the judge conspires to deceive and defile the maid. Virginius’ anguished decision is in fact reminiscent of Abraham’s, but with one primary difference—the maid perishes. Her father’s pity for her, despite his resignation, is evocative:

And with a face deed as asshen colde

Upon hir humble face he gan biholde,

With fadres pitee stikynge thurgh his herte,

Al wolde he from his purpos nat converte. (VI.209-12)

One may question his judgment, priorities, steadfast determination, or his failure to find alternatives to killing her, but not his sorrow for having to do so. His lament to her is emotional and pained:

Ther been two weyes, outher deeth or shame,

That thou most suffre; alias, that I was bore!

For nevere thou deservedest wherfore

To dyen with a swerd or with a knyf.

Ο deere doghter, endere of my lyf,

Which I have fostred up with swich plesaunce

That thou were nevere out of my remembraunce!

Ο doghter, which that art my laste wo,

And in my lyf my laste joye also. (VI.214-22)

His announcement to her of impending death, her incredulity, her begging for mercy, her tears as she hangs on his neck, her final resignation in God’s name reiterate Isaac’s lament:

“O mercy, deere fader!” quod this mayde …

VI.231, 234-36; 246-50

The teeris bruste out of hir eyen two,

And seyde, “Goode fader, shal I dye?

Is ther no grace, is there no remedye?” …

And after, whan hir swownyng is agon,

She riseth up, and to hir fader sayde,

“Blissed be God that I shal dye a mayde!

Yif me my deeth, er that I have a shame;

Dooth with youre child youre wyl, a Goddes name!”

Albrecht Classen’s fine introduction to this volume points to similar grief when Engelhard also laments his own killing of his children. Had a deus ex machina or other divine interposition appeared from the sky to spirit her to safety, this tale would more precisely recreate the Abraham and Isaac play; but, unfortunately for Virginia, no saving redemption is at hand. Death by the sword, despite her heavenly victory, places her within the “Slaughter of the Innocents” paradigm. The entire narrative centers around the child Virginia, and without her, and her pathetic situation, the story and tale could not exist. Whether his action of killing the maid is legitimate or not, Virginius’ pain in doing so is undeniable, as it heightens the pathos and confirms his emotional involvement with his daughter.

The Monk’s Tale

Likewise, in Chaucer’s Monk’s Tale, Hugelyn is yet another anguished father unable to prevent his sons’ death. Although his cannibalism is found in the tradition, this facet of the lore is omitted in Chaucer’s version. The Monk begins his story with

Off the Erl Hugelyn of Pyze the langour

VII.2407-08

Ther may no tonge telle for pitee.

Like the Prioress, the Monk elicits sympathy for the sons based on their youthful innocence, for “The eldest scarsly fyf yeer was of age” (VII.2412). Imprisoned in a tower with their father without adequate food, their plight elicits his heartfelt compassion. Realizing that they will die soon, “Alias!” quod he, “Alias that I was wroght!” / Therwith the teeris fillen from his yen” (VII.2429-30). Even more pathetic and emotionally stirring are the queries of the youngest:

His yonge sone, that thre yeer was of age,

VII.2431-36

Unto hym seyde, “Fader, why do ye wepe?

Whanne wol the gayler bryngen oure potage?

Is ther no morsel breed that ye do kepe?

I am so hungry that I may nat slepe.

Now wolde God that I myghte slepen evere!

Realizing his end is near, with no rescue possible, the babe cries “Tarewel, fader, I moot dye!’/ And kist his fader, and dyde the same day” (VII.2441-42). Biting his arms for grief, Hugelyn agonizes over the baby’s death until his sons, thinking him hungry, offer him their flesh saying:

… Fader, do nat so, alias!

VII.2449-52, 2454

But rather ete the flessh upon us two.

Oure flessh thou yaf us, take oure flessh us fro,

And ete ynogh” …

They leyde hem in his lappe adoun and deyde.

Interestingly this time the focus of pity is split between Hugelyn and his sons, all victims of starvation and he being a victim of cognition. No sense of redemptive grace lightens this tragic, and even sensational scene. It is a tale of child-parent interaction, desperation and horror.

The Alliterative ‘Morte Arthure’

Few children people the Arthurian Courts, but Guinevere’s and Mordred’s children in the Alliterative Morte Arthure22 stand out as the exception. The only crime of these doomed children is that of their birth, their heritage: they are as illegitimate as their notorious father Mordred, and as cursed. These incestuous offspring of Queen Guinevere and her husband King Arthur’s son/ nephew Mordred by Arthur’s sister Morgan la Fay are succinctly, but definitively laid to rest. Mordred, realizing their danger, sends word to Guinevere to “fly far off and flee with her children, / Till he could steal off and speak to her safely” (3907-08). But Arthur’s vengeful retaliation will no doubt reach them. In the final throes of battle, having been butchered by his illegitimate son, the King demands the death of his grandsons: on his deathbed, Arthur will prevent these children from running, and perhaps ruining the realm, by ordering their slaughter:

Sithen merk manly to Mordred children,

That they be slely slain and slongen in waters;

Let no wicked weed wax ne writhe on this erthe (4320-22)[… sternly mark that Mordred’s children

Be secretly slain and slung into the seas:

Let no wicked weed in this world take root and thrive.]

These innocent sons of a traitorous father and vengeful grandfather are considered dangerous because of their heritage—for there is precedent: Mordred himself is thought evil because of his unnatural birth, son of a brother and sister. For his young sons, there is no redemption. They too are slaughtered innocents, dead at the hands of their vengeful surrogate-father, their mother’s husband. Although the children are not the subject of this story of an empire’s self-destruction, their slaughter is the culmination of all that is unjust within it—that injustice perhaps being one reason for its ultimate demise.

Thus, no saving grace reclaims these poor unfortunates—Virginia, the Prioress’s little clergeon, Hugolino’s sons, Guinevere and Mordred’s children—from the ravishes of this world—often implemented by their parents. However spiritually saved, they are doomed to the world. As metaphorical siblings of the innocents slaughtered by Herod, they share in the characteristics of that paradigm: empathetic treatment, some complicity by parents, but final demise.

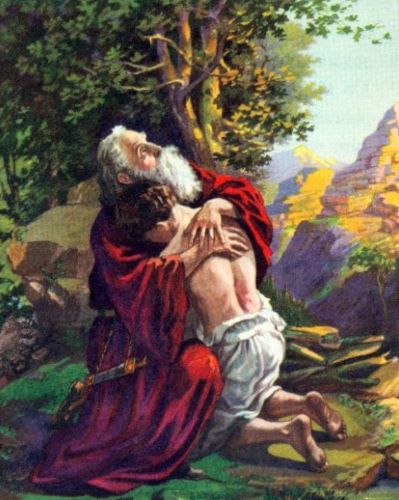

Redemption of Isaac

The “Abraham and Isaac” model offers a more fortuitous fate, for although these children undergo hardship, they yet find relief in rescue, ultimately becoming relatively happy. Interestingly, a parent, albeit an unwilling one, is still often the source of danger to, as well as pity for these innocents. Anne Lancashire precisely summarizes the Isaac story as interpreted by medieval dramatists, noting:

In the seven British Abraham and Isaac plays still extant today—four from the English cycles, one from the Cornish cycle, and the Brome and Northampton Abraham and Isaac dramas—details of the story vary, but within an outline common to all: God’s ordering of the sacrifice, Abraham’s acceptance of God’s will, Abraham’s sorrow at what he must do, a lengthy dialogue between Abraham and Isaac, which includes Abraham’s announcement to Isaac that Isaac must be killed by his father, Isaac’s (ultimate) acceptance of God’s will (except in the Towneley play), and God’s intervention at the moment of sacrifice, to save Isaac. And some details, though not found in all seven, are in a majority of the plays: for example, Isaac’s extreme youth and innocence, Isaac’s initial terror when told by Abraham of the necessary sacrifice, Isaac’s request for a quick or easy death, and reference to a sword as the instrument of sacrifice. In every play, at the heart of the drama is the dialogue between Isaac and his father: a dialogue highly emotional, and emphasizing the mutual love of father and child.23

This Biblical trope of a father instructed to slay his only son whom he loves and prizes as a test of loyalty to God, cruel as it might be, finally proves joyous at the end. The entire focus of these plays is on the subject, the idealized boy Isaac; God’s harsh injunction and Abraham’s obedient response both center on the child, even though the message of the tale is that one owes God whatever he demands, morally justified or not.

The Brome Old Testament “Sacrifice of Isaac,” a figural anti-Crucifixion play prefiguring the sacrifice of Christ, differs from its New Testament fulfillment in that the sacrifice of Isaac is never in fact enacted. Nevertheless, the pathos from the danger to young Isaac, and Abraham’s passion for and fear of his loss is evocative. As David Bevington says of the play, “The account is remarkable for its ballad-like simplicity, its intense portrayal of filial and parental tenderness, and its sustaining of dramatic tension.”24 The diction is appropriately child-like, even when Abraham speaks. His prayer to God aptly sets the stage for the conflict:

In my age thou hast grantyd me this,

11-20

That this yowng child with me shall won.

I love nothing so myche, iwisse,

Excep[t]e thin[e] owyn selffe, dere Fader of blisse,

As Isaac her[e], my owyn swete son.

I have diverse childryn moo,

The w[h]ich I love not halffe so well.

This fayer swet child, he schereys me soo

In every place w[h]er that I goo,

That noo dessece her[e] may I fell.

Ironically, like Joseph the favorite son, Isaac will be endangered precisely because of his father’s preference. His value in himself, as a “swet child” and to his father whom he attempts to cheer up in his time of anguish, establishes the expectation of disaster. Both touching, and anticipatory, Abraham prays for Isaac’s health, grace, and safety. Isaac’s ready obedience to follow Abraham without question when “Goo we hom and take owre rest” anticipates his ready obedience in a more perilous adventure. The play offers the dubiously legitimate motive for God’s testing of Abraham: a father’s express devotion to his son by an Old Testament God jealously testing “Whether he Iovith better his child or me” (44). Compliance wins him God’s friendship. Abraham’s crisis of conscience is wrenching, evoking pity for the struggling old man who utters:

I lovyd never thing soo mych in erde,

76-78; 81-82

And now I must the child goo kill.

A, Lord God, my conseons is stron[g]ly steryd! …

I love my child as my liffe,

But yit I love my God myche more.

But the resolution is one thing; the execution is another. The agonized father repeatedly expresses his anguish, exclaiming:

A, Lord of hevyn, my handys I wring!

120-21; 127-28

This childys words all to-wo[u]nd my harte

… my hart brekith on twain,

This childys wordys they be so tender!

Isaac’s slow realization that, lacking a live beast to sacrifice, he is to die in its stead, is skillfully depicted. The boy cries out,

Ya, fader, but my hart beginnith to quake,

147-48; 153-54; 161-62

To se that scharpe sword in yowre hond …

Tell me, my dere fader, or that ye ses,

Bere ye yowre sword draw[n] for me? …

I preye yow, fader, that ye will let me it wit,

W[h]yther schall I have ony harme or noo?

The absolute vulnerability and innocence of the child evokes pathos. When Abraham responds “A, Isaac, Isaac, I must kill the[e]!” (167), the shocked boy retorts,

Kill me, fader? Alasse, w[h]at have I don?

168-172

Iff I have trespassyd agens yow ow[gh]t,

With a yard ye may make me full mild;

And with yowr scharp sword kill me nought,

For iwis, fader, I am but a child.

He is right—this is not the way to treat children. Furthermore, there must be an alternative remedy, even if it be beating. Even more evocative is Isaac’s humble, if fearful acceptance, “I will never groche, lowd nor still” (191). Besides, he selflessly continues, you have another child or two whom you love, so

… make ye no woo;

(200-202)

For be I onys ded and from yow goo,

I schall be sone owt of yowre minde.

We watch the boy’s mind move from point to point, following his consciousness, fear, and stoic resolution. His only request is not for himself, but, he begs, “tell ye my moder nothing; Sey that I am in another cuntre dwelling” (205-06). The child’s generous, selfless spirit makes his plight all the more pathetic. No less anguished is his father’s response “Son, thy wordys make me to wepe full sore! Now my dere son Isaac, spek no more” (224-25). He asks only that his father “Smyth but fewe strokys at my hed,/ And make an end as sone as ye may,/ And tery not to[o] long” (230-33). But the prolonged farewell of Abraham’s kissing his son, proving his reluctance, only heightens the emotion, as does Isaac’s reassurance that Abraham need not bind his arms, for he will not resist. Rather, he encourages the deed with “My fayer swete fader—I geffe yow leve” (254). If children in the drama and other genres are often symbolically offered on the sacrificial altar, little Isaac is placed there literally! This contrasts the voluntary sacrifice of the young peasant girl discussed by David Tinsley in his “Reflections of Childhood in Medieval Hagiographical Writing: The Case of Hartmann’s Der arme Heinrich” in this volume. As the mourning Abraham bemoans the deed, his son begs

A, mercy, fader, mo[u]rne ye no more!

282-85

Yowre weping make[th] my hart sore

As my owyn deth that I schall suffere.

Yowre kerche, fader, abowt my eyn ye wind.

Just at the moment of slaughter, an angel miraculously appears to remove Abraham’s sword and replace the child with a sacrificial ram, saying “For Isaac, thy yowng son that her[e] is, / This day schall not sched his blood” (326-27). Just as Isaac substituted for Christ, so does the ram, a “jentyll scheppe,” for him. This twelfth-hour reprieve, a true salvation from death, is granted the child Isaac, and other literary children whom he epitomizes. Its concluding line reassuringly suggests that “Jesu, that werit[h] the crown of thorne, /[will] Bring us all to hevyn blisse!” (464-65). Thus the play reinforces its comic resolution and signifies a redemptive salvation, a gentler model for the fate of some children elsewhere in medieval texts.

Other Redeemed Children: ‘Amis and Amiloun’

Children redemptively saved after dangerous circumstances are more numerous than those slain outright. Amis’ unnamed children, “Pe fairest pat mist bere Hue” (1535) in the romance Amis and Amiloun,25 play a surprisingly significant role, for by their deaths, they save the desolate Amiloun from the dreaded pain of leprosy. Most of the romance transpires without their agency, as the devoted best friends Amis and Amiloun grow to manhood, marry ambiguously virtuous wives, and prove their capacity to rule kingdoms. When Amis requires the military services of his compatriot, Amiloun complies, but only with the onus of leprosy on his back for deceptively fighting as Amis. When the supernatural agent, the angel-messenger, reports that the children must be killed to save Amiloun from his leprous punishment—unlike Isaac who must be killed because of God’s jealous decree—another father will capitulate. The narrator relates:

An angel com fram heuen brist

(2200-08)

& stode biforn his bed ful rist

& to him ]JUS gan say:

if he wald rise on Cristes morn,

Swiche time as Ihesu Crist was born,

& slen his children tvay,

& alien his [broker] wi]s blode,

Iurch godes grace, fat is so gode,

His wo schuld wende oway.

The emotionally shocking incident absorbs some two hundred lines, perhaps to acclimate the audience to such an unexpected event. This father’s sorrowful reluctance to lose his children parallels Abraham’s incredulity, painful resistance and grudging acceptance of Isaac’s doom. He indecisively meditates:

Ful blijj was sir Amis so,

2215-19; 2245-50

Ac for his childer him was ful wo,

For fairer ner non born.

Wei loj) him was his childer to slo,

& wele lojjer his broker forgo….

tan jaoUjt {je douk, wi{j-outen lesing,

For to slen his childer so sing,

It were a dedli sinne;

& Jsan {x)ust he, bi heuen king,

His broker out of sorwe bring,

For Jat nold he noust blinne.

So, on Christmas Eve when all were at mass, Amis secretly steals into the nursery with candle and sword to perform his rite. The anguish of this parent perpetrating death on his innocents recalls Abraham’s similar distress:

[He] biheld hem bope to,

(2284-92)

Hou fair pai lay to-gider po

& slepe bop yfere.

fan seyd him-selue, “Bi Seyn Jon,

It wer gret rewepe sou to slon,

at god hap boust so dere!”

His kniif he had drawen pat tide,

For sorwe he sleynt oway biside

& wepe wip reweful chere.

Amis’ s obligation to his sworn brother is felt nearly as onerous as Abraham’s to God. Unlike Isaac, these children are not spared the knife. But like Isaac, rescued at the last moment, these innocents are miraculously restored to life, albeit after their murder. Amis’s grief is substantially lesser than the elderly prophet’s, for as his wife reassures him, they can engender more children, while Abraham cannot. As Albrecht Classen has well pointed out in his Introduction, in Konrad von Würzburg’s Engelhard, such a discussion between husband and wife does not transpire since Engelhard is alone at home, where he reflects upon the conflict between his love for his friend and his love for his children. Yet the stark grotesqueness of the actual murder is even more emotionally shocking than Isaac’s putative one, having been enacted with all the blood and gore of a Renaissance revenge tragedy. Their father

… hent his kniif wif dreri mode

2306-12

& tok his children po;

For he nold noust spille her blode,

Ouer a bacine fair & gode

Her throtes he schar atvo.

& when he hadde hem bope slain,

He laid hem in her bed ogain.

No less gruesome is the smearing of “Jjat blod |jat was so bri3t” (2341) all over the body of Amilion to complete the sacrificial rite. Anticipation builds as the household seeks the missing keys to the nursery, and as Amis requests his wife to enter alone with him. Like Isaac’s mother, she has no knowledge of the impending, or real disaster. Having ritually recounted the murder to Amilioun, Amis repeats it to his wife with anguish. But when they finally enter the death-chamber, the babies are joyfully playing together, miraculously restored to their former health. For joy the parents weep. Thus these children are the sacrificial means of restoration for Amilioun, and are themselves supernaturally restored. The focus of the tale rests doubly upon the emotional bond between parents and children and between Amis and Amiloun, but concern for and restoration of the children is the essential culminating force that makes this tale a romance rather than a tragedy.

The Clerk’s Tale

Griselda’s children in the Clerk’s Tale wield a similarly significant narrative power, again as pawns in their perpetrating father’s scheme. In this case, they are temporarily sacrificed not to save another, but for Walter’s indulgence, to test Griselda’s fidelity. When he asks her permission to kill her daughter, Griselda dutifully responds:

My child and I, with hertely obeisaunce,

(IV.502-04)

Ben youres al, and ye mowe save or spille

Youre owene thyng; werketh after youre wille.

Her maternal anguish is discerned in her injunction to the servant:

But ο thyng wol I prey yow of youre grace,

(IV.569-72)

That, but my lord forbad yow, atte leeste

Burieth this litel body in som place

That beestes ne no briddes it torace.

When, despite her loss, Griselda patiently bears a son, Walter’s second testing elicits the same obedience:

I wol no thyng, ne nyl no thyng, certayn,

(IV.646-48)

But as yow list. Naught greveth me at al,

Thogh my doghter and my son be slain.

Audience sympathy is with Griselda, who believing her offspring dead, suffers pain of loss; sympathy is thus not generated for the children, who in fact are not ultimately harmed. The revelation of their safety after believing them dead for years provokes her fainting, and her joyful tears:

… after hire swownynge

(IV.1080-85)

She bothe hire yonge children to hire calleth,

And in hire armes, pitously wepynge,

Embraceth hem, and tendrely kissynge

Ful lyk a mooder, with hire salte teeres

She bathed bothe hire visage and hire heeres.

The children’s vulnerability and weakness are highlighted, much as they were in the “slaughter of the innocents” victims, as Griselda laments “O tendre, ο deere, ο yonge children myne!” (IV.1093) before fainting a second time. Not a dry eye was left at the celebration, as pity moved the actual and reading audience. Once again, a father is responsible for his children’s welfare while a mother remains ignorant of their situation. Ironically, Griselda attributes Walter with saving her children, those who would never have been in jeopardy were it not for him! Since these innocents are only thought dead, their restoration is achieved naturally, without supernatural intervention such as the messenger-angel needed to rescue Isaac. The pattern of harsh fathers, unknowing mothers, and victimized children is repeatedly used for its evocative effect. Here the children play a pivotal narrative role, being the most precious objects of which Walter could deprive Griselda, the most extreme form of testing her loyalty to him, and the means of enacting a joyous culmination after she painfully accedes to his cruel demands.

The Man of Law’s Tale

Custance’s son in the Man of Law’s Tale undergoes actual and traumatic peril through the agency of an unnatural grandmother and naive father, thus breaking the format of paternal harshness seen above. The story begins when young Custance, herself no more than a child, pitifully begs her parents not to marry her off and send her half a globe away as an exile in a foreign land. Her words are particularly resonant of her own salvation and redemption as she begs for those graces: “Crist, that starf for our redempcioun / So yeve me grace his heestes to fulfille” (11.283-84). The emotional tenor continues as pity and fear are evoked through her speech:

“Fader,” she seyd, “thy wrecched child Custance,

(11.274-79)

Thy yonge doghter fostred up so softe,

And ye, my mooder, my soverayn plesaunce

Over alle thyng, out-taken Crist on-lofte,

Custance youre child hir recomandeth ofte

Unto youre grace.

Ironically, Custance, herself a pitiful, abandoned, vulnerable child at the beginning of her tale, and rescued much like Isaac and her own son by the end, is the means of Maurice’s survival. Here parental protection, not afforded her, proves his succor, and finally leads to his redemption. The process is a traumatic one. At his very birth, Maurice is threatened by his grandmother Donigeld’s interception of letters to her son; she deceitfully describes him as “a feendly creature” (11.751) and destroys Allah’s injunction to “Keepeth this child, al be it foul or feir” (11.764). Custance’s natural maternal instinct to protect her son is a foil to their callous treatment:

Hir litel child lay wepyng in hir arm,

(11.834-40)

And knelynge, pitously to hym she seyd,

“Pees, litel sone, I wol do thee noon harm.”

With that hir coverchief of hir hed she breyde

And over his litel eyen she it leyde,

And in hir arm she lulleth it ful faste,

And into hevene hire eyen up she caste.

The emotional tone and Custance’s protective gesture heightens Maurice’s vulnerability and audience pathos for his plight. Patricia Eberle’s notes to the Riverside Chaucer mention Bartholomaeus Anglicus’ injunction that “children should be protected from bright light, ‘for a place that is to bright departith and todelith the sight of the smale eiye that bes right ful tendre”‘ (862, n.837-38). This means of torture of children, of shining extremely bright light in their eyes, reinforces their vulnerability. Lancashire takes this as the explanation for Abraham’s covering Isaac’s eyes in many cycle plays when preparing to sacrifice him very literally.26 This seems to make perfect sense in the “Clerk’s Tale” where Custance is protecting her child from many things, light being one, and lulling him to sleep, darkness being conducive to repose; but it makes less sense in the Isaac story in which Abraham seems to be minimizing Isaac’s grief by preventing him from witnessing his own murder. Abraham can hardly be overly concerned with protecting his eyes while sacrificing his body to death.

When the false orders condemn her son to the sea, Custance’s maternal anguish inspires prayers to the Virgin who has similarly witnessed her own son’s demise. The distraught mother bemoans the innocence of her endangered child, claiming

“O litel child, alias! What is thy gilt,

(11.855-57)

That nevere wroghtest synne as yet, pardee?

Why wil thyn harde fader han thee spilt?”

Much like Griselda, begging the servant to let her give her usurped children a good-bye kiss, and not to let the beasts and birds feed on her young, with the same pathos Custance begs the servant

As lat my litel child dwelle heere with thee;

(11.859-61)

And if thou darst nat saven hym, for blame,

So kys hym ones in his fadres name!”

A similar sorrowful resignation, much like Abraham’s and even young Isaac’s, envelops these mothers. But after five years adrift, Custance and Maurice survive the natural elements. When tossed ashore and attacked by a heathen thief, they are saved through the Virgin Mary’s agency. The final fortuitous stroke of luck or providence is Maurice’s striking resemblance to Custance, for when Alia journeys to Rome and encounters the lad, he immediately sees his wife’s visage. A reunion—joy after woe—much like that of the Clerk’s Tale ensures the final and permanent safety of mother and son.

Here, not a vituperative father, but the agency of an evil woman, jealous of her daughter-in-law and protective of her Muslim beliefs, is the cause of the conflict. Both daughter-in-law Custance and grandson Maurice must suffer the consequences of her venom, with fate or Divine Providence protecting them from harm. The final restoration of the family through the physical appearance of young Maurice places him at the heart of the story, the most significant narrative agent for reuniting his parents.

Kidnapped children such as Tristan, Arthur, and Horn, later rightfully restored to their proper role form yet another coterie of abused children, albeit not usually by their parents. Although this discussion cannot include all their fates, they too fall into the Abraham-Isaac category of “ultimately redeemed.” Some children such as the Pearl maiden in The Pearl, little Sir Thopas in Chaucer’s Tale of Sir Thopas, the Merchant’s Tale’s little girl sitting silently with the wife, and little Owaines in Amis and Amiloun of course, fit into neither of these two iconic oppositional paradigms for they do not appear to suffer. The Pearl maiden’s function is to advise the obtuse narrator from a privileged vantage point, while Thopas gallops through his romance without much purpose at all—obviously Chaucer’s intent for him. The silent little girl in the Merchant’s Tale similarly claims no particular role beside that of innocent foil to the not-so-innocent wife, although her emotional state might be said to be affected. Child Owaines serves his leprous uncle Amiloun with generous devotion, and suffers his uncle’s pain with him, but is himself no victim. But these children are the exceptional few. In most cases of destruction and reclamation of children, audience involvement is ensured through the force of pitee evoked for the vulnerable children, often fragile, docile, unknowing victims of fate or fortune, good or evil.

Literary depiction of children owes much to the social situation in which they lived, and a type of accurate, gruesome realism permeates these children’s tales. John Boswell indicates that “The first of the authoritative collections of canonical decrees to influence the whole Western church was compiled by Regino of Prüm around 906. It imposes severe penalties for infanticide, for accidental suffocation of infants by parents, and even for the possibility of negligence when a child dies and the parents may not have done everything possible to prevent it.”27 The need for such decrees reveals much about the social attitude of the time. By the high Middle Ages, offering children to the church as oblations, or to creditors to satisfy debt was not uncommon, as Valerie Garver also points out in contribution to this volume, “The Influence of Monastic Ideals upon Carolingian Conceptions of Childhood.”28 Similarly, Boswell, commenting on a Bodleian manuscript miniature (Ms Bodl. 270b, fol. 181), states that starving mothers fighting over whose child they will eat is a “shocking topos occurring] with surprising frequency The king, observing the pitiful scene, rends his garments in horror [which] indicates, at the least, concern about the fate of children during periods of social distress.”29 Unfortunately that concern did little to alleviate the plight of many children—those dumped in rivers with weights attached to them to assure drowning, those beaten, or ignored. Investigation of literary children, emblemized in medieval drama as doomed or redeemed, concretely reinforces and graphically illustrates the assertion of brutality toward actual children, revealing them as the literary models used to evoke pity—occasionally salvaged, but often unsaved. Two major Middle English prototypical plays, the “Slaughter of the Innocents” and “Abraham and Isaac” well embody these dual treatments afforded many literary children. No doubt the actual social situation was as varied as its constituents-some children were well treated, and others not; but medieval authors, like the sensational media compilers today, often found more interest in scenes of lurid pain and anguish-of children suffering, dying, reaching the brink of disaster, and sometimes being saved. Their dramatic exemplars thus offered sensational material for other genres’ emulation in a most pitiful and powerful fashion.

Endnotes

- Earlier versions of this paper were delivered at the Southeastern Medieval Association in Asheville, North Carolina, September 2000 and at the Conference on Childhood in Tucson, April, 2004.

- Quoted by Christiane Klapisch-Zuber,” Women and the Family,” The Medieval World, ed. Jacques LeGoff, (1990; London: Collins and Brown, 1997), 303.

- Klapisch-Zuber, “Women and the Family,” 303.

- Klapisch-Zuber, “Women and the Family,” 302-03.

- Philippe Aries, Centuries of Childhood: A Social History of Family Life, trans. Robert Baldick (New York: Knopf, 1962).

- Hans-Werner Goetz, Life in the Middle Ages from the Seventh to the Thirteenth Century, tr. Albert Wimmer (Notre Dame and London: University of Notre Dame Press, 1993), 54.

- Barbara Hanawalt “Narrative of a Nurturing Culture: Parents and Neighbors in Medieval England,” Essays in Medieval Studies 12 (1995), http://www.luc.edu/publications/medieval/voll2/hanawalt.html (last accessed on March 14, 2005).

- John Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers: The Abandonment of Children in Western Europe from Late Antiquity to the Renaissance (New York: Pantheon, 1988,) 36,37.

- Graizbord, “Converso Children,” 381.

- Klapisch-Zuber, “Women and the Family,” 303.

- Jacques Le Goff, “Introduction,” The Medieval World, ed. Jacques Le Goff (1990; London: Collins and Brown, Ltd., 1997), 16-17.

- Goetz, Life in the Middle Ages, 54.

- Boswell, Kindness of Strangers, 26, 30.

- MacEdward Leash, Amis and Amiloun. EETS, o.s. 203 (1937; London, New York, and Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1960), 128, note to 1.1828.

- Peter Fleming, Family and Household in Medieval England (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 59.

- E. J. Graff, “What Makes a Family/’WTiaf Is Marriage For? (Boston: Beacon Press, 1999), 95-97.

- Medieval Drama, ed. David Bevington. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975), 67. Subsequent quotations will be from this text unless otherwise noted.

- Patricia Clare Ingham, “From Kinship to Kingship: Mourning, Gender, and Anglo-Saxon Community,” Grief and Gender: 700-1700, ed. Jennifer C. Vaught with Lynne Dickson Bruckner (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), 17-31; here 18.

- Ingham, “From Kinship to Kingship,” 19.

- Riverside Chaucer, ed. Larry D. Benson (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987), VH565-66. Subsequent quotations of Chaucerian texts will be taken from this volume.

- Anne Lancashire, “Chaucer and the Sacrifice of Isaac/’Chaucer Review 9 (1975): 320-26.

- King Arthur’s Death: The Middle English Stanzaic Morte Arthur and Alliterative Morte Arthure, ed. Larry D. Benson. The Library of Literature, 29 (Indianapolis and New York: Bobs Merrill Co., 1974).

- Lancashire, “Chaucer and the Sacrifice of Abraham/’ 321.

- Bevington, Medieval Drama, 308.

- Leach, Amis and Amilouti Subsequent quotations homAmis and Amiloun are from this edition.

- Lancashire, “Chaucer and the Sacrifice of Isaac,” 324.

- Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers* 222.

- For valuable suggestions and comments on various versions of this essay and the paper from which it was originally drawn I would like to thank Albrecht Classen , Robert Feldacker, Tom Noble, and fellow scholars who attended the international symposium on “Childhood in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Age,” at the University of Arizona (April 30-May 2, 2004).

- Boswell, The Kindness of Strangers, fig· 8, following p. 270.

Contribution (307-328) from Childhood in the Middle Ages and Renaissance, edited by Albrecht Classen (Walter de Gruyter, 07.18.2005), published by OAPEN under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported license.