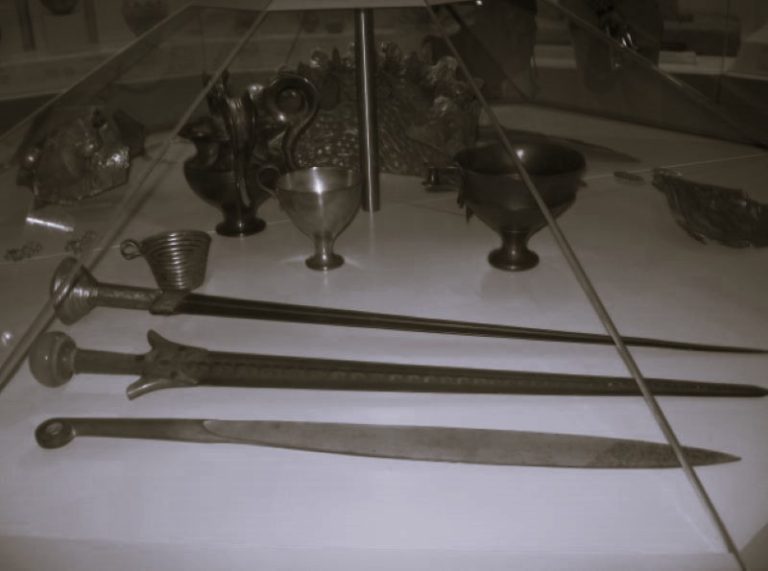

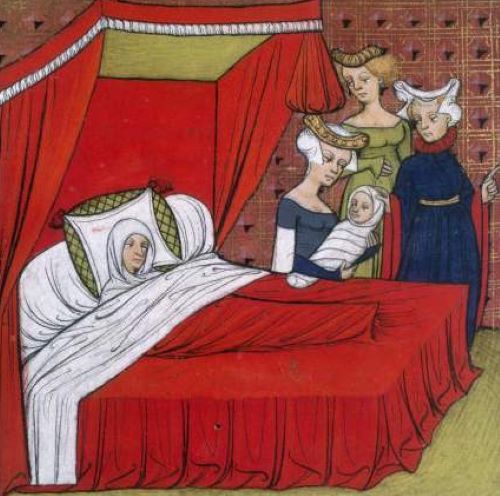

The birthing chamber was a dimly lit, crowded, and hardly antiseptic space.

By Dr. Louis Schwartz

Professor of English

University of Richmond

In her memoir, written in her early forties, Alice Thornton offered this account of the birth of the fifth of her nine children:

“…upon the Wednesday [December 10, 1657]…I fell into exceeding sharpe travill in great extreamity, so that the midwife did beleive I should be delivered soone. But loe! it fell out contrary, for the childe staied in the birth, and came crosse with his feete first, and in this condition contineued till Thursday morning betweene two and three a clocke, at which time I was upon the racke in bearing my childe with such exquisitt torment, as if each [limb] weare divided from other…att length, beeing speechless and breathlesse, I was, by the infinitt providence of God, in great mercy delivered. But I having had such sore travell in danger of my life soe long, and the childe comeing into the world with its feete first, caused the childe to be allmost strangled in the birth, only liveing about halfe an houer, so died before we could gett a minister to baptize him.”

Despite her pains and her loss, Thornton offered no despairing complaints. In fact, in another passage, she offered this pious meditation: “I trust in the mercys of the Lord…He requiring noe more then He gives. and His infinitt grace was to me in sparing my soule from death. Tho’ my body was torne in pieces, my soule was miraculously delivered”. She was thankful, not just for survival, but for the miracle of survival with her faith intact.

This is a good example of how English women confronted the pains and dangers of childbirth in the 17th century. In London and other cities and larger towns, about one woman died for every 40 births. And there was very little that the medical ingenuity of the day could do about that sad fact. A skilled midwife or surgeon could solve simple malpresentations, and a few could sew up perineal tears, but infections, haemorrhages, and toxaemia were beyond remedy. As a result, it was religion, rather than medicine that came to people’s rescue, providing comfort in the face of what could not be avoided. Religion gave some women a sense of control. Pain took on a spiritual significance, becoming not just a punishment, but a test. If they passed, women could be rewarded with either continued life or salvation after death. What mattered most about suffering was how one faced it.

Women also accepted pain and danger as marks of their zeal to obey God’s first commandment (“be fruitful and multiply”). Today, we might think of early modern women’s choices as limited by the culture’s ideas about gender or a lack of effective contraception, but many women felt that they had freely chosen motherhood in rejection of a celibate religious life, a “free” single life (that such a thing hardly existed seemed not to matter), or marriage without children. They saw themselves as suffering, anointed vessels of God’s creative power, as willing partners with Him in the act of creation. In the experience of birth itself, they surrounded themselves with other women, with a midwife and gossips who presided over a world with special rites and practices from which men were almost entirely excluded.

The poem Mary Carey wrote after a miscarriage she suffered just a few weeks after Alice Thornton’s painful stillbirth provides a striking example of how a woman might also re-imagine ideas she encountered in books written by men. Puritan preachers like John Oliver often proclaimed that women had to “repent of the miscarriages of [their] lives, if [they] would be provided against the danger of a miscarrying womb”, and Carey took the idea seriously. But not simply as an admonition. “Methinkes I heare Gods voyce”, she says in her poem, after asking Him why she had lost yet another child—she had given birth to seven, but only two were still living. God’s answer starkly echoes Oliver, but in response Carey’s religious imagination takes flight: “Lett not my hart, (as doth my wombe) miscarrie,” she pleads,

“but precious meanes received, lett it tarie;Till it be form’d; of Gosple shape, & sute;my meanes, my mercyes, & be pleasant frute:In my whole Life; lively doe thou make me:for thy praise. And name’s sake, O quicken mee;”

For 30 lines she continues, repeating the request for “quickening” over and over, weaving together more than a dozen echoes of scripture until her response becomes a passionate request for life, fertility, and grace. It may be difficult for modern readers to embrace what seems masochistic—she does at one point say that she wants to kiss the rod that God took in hand to punish her—but the passage also expresses a striking imaginative power. Carey not only re-imagines her spiritual regeneration in terms of her own bodily experience, but behind her figure of the heart-as-womb lies Paul’s sense of himself as a mother travailing “in birth again until Christ be formed” in his followers (Galatians 4:19). Carey claims the power not just to give birth to children, but to evangelise, to shape the souls of those who might witness her behaviour or read her poem.

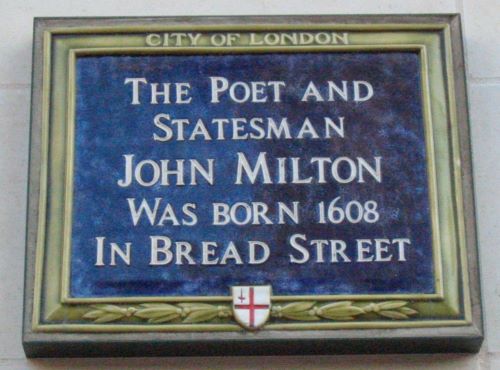

A few male poets also confronted the pains of childbirth, although they did so primarily as mourners. In John Milton’s Twenty-third Sonnet, for example, a bereaved husband dreams he sees his wife return from the dead. The poem’s allusions to the myth of Alcestis, to Old Testament rites of childbirth purification, and to contemporary childbirth rituals like the “Churching of Women”, all express an unresolved sense of sorrow, possible despair, and guilt:

“Methought I saw my late espousèd saintBrought to me like Alcestis from the grave,Whom Jove’s great son to her glad husband gave,Rescued from death by force though pale and faint.Mine as whom washed from spot of child-bed taintPurification in the Old Law did save,And such, as yet once more I trust to haveFull sight of her in Heaven without restraint,Came vested all in white, pure as her mind:Her face was veiled, yet to my fancied sight,Love, sweetness, goodness in her person shinedSo clear, as in no face with more delight.But O as to embrace me she inclined,I waked, she fled, and day brought back my night.”

Mary Powell, Milton’s first wife, died on May 5, 1652, 3 days after giving birth to her fourth child, and Katherine Woodcock, his second wife, died on Feb 3, 1656, of a “consumption” she seems to have contracted in the childbed while giving birth to her first child. The poem was probably written after the death of Katherine and her daughter, but it is full of images that can refer to either woman. It is particularly poignant that the speaker imagines his spouse fleeing just as he wakes—as if she were somehow afraid of his waking into the embrace she seemed about to give him. Some combination of sexual and emotional arousal, a sense of what has been lost in death, and guilt over what had actually killed both women (a penalty from which men were immune) causes the bereaved husband both to wake and to project fear onto the dream-image of his wives.

At around the same time, Milton also began working in earnest on Paradise Lost, and when he came to the moment where he had to imagine Eve’s creation, he decided to have Adam witness it while in a dream. Adam’s account is framed, moreover, by lines that echo the sonnet: “methought I saw,/Though sleeping, where I lay…,” he says, before describing how God opened his side, took out a rib, and formed a creature from it. Adam immediately falls in love with that creature, but then Milton has her disappear, leaving Adam “dark”. When he wakes, he finds her gone, and she only reappears, “led by her heavenly maker” and “such as” he “saw her in [his] dream”, after Adam begins to despair. These echoes bring the sad music of Milton’s sonnet into Adam’s celebratory account, as if Milton could not imagine his way back into the experience of the first man without carrying with him the burden of his own losses and those of so many of his contemporaries.

Poems and passages like those I have quoted give us a glimpse at how people dealt with problems that most of us who live in developed countries today will never face. The same desires for control and meaning, however, are still with us in childbirth. We may no longer need religion to explain things that we can now avoid, and I doubt that most of us would wish to revive the sorts of explanations that circumstance and religious doctrine drew out of Thornton, Carey, and Milton. Still, religion has hardly disappeared from public debate over what it means to become pregnant and what it means to exercise the choices that science now makes possible. In considering such choices, it is useful to take the long view of how people have used their imaginations to cope with life in the imperfect and vulnerable human body. This is especially so when it comes to the power our bodies have to recreate life in ways that still seem mysterious to us despite our greater technical understanding. Control, after all, isn’t everything, and it brings its own new demands and dilemmas. The men and women of early modern England exercised tremendous creativity in coping with the unavoidable. Their birthing chamber was a dimly lit, crowded, and hardly antiseptic space, but it was redolent with symbolism and rites that gave women a dramatic sense of their cosmic and social importance. It would be a shame if the things we can now do in a brightly lit hospital room should inadvertently also drain away some of that empowering mystery. And when terrible things such as perinatal loss happen, as of course they still do, perhaps we may need poetry or religion as much as any 17th-century Londoner.

Originally published by The Lancet 377:9776 (04.30.2011, 1486-1487) under the terms of a Creative Commons license.