An attack on private property angered Colonial leaders as much as the British public.

By Dr. Eliga Gould

Professor of History

University of New Hampshire

Introduction

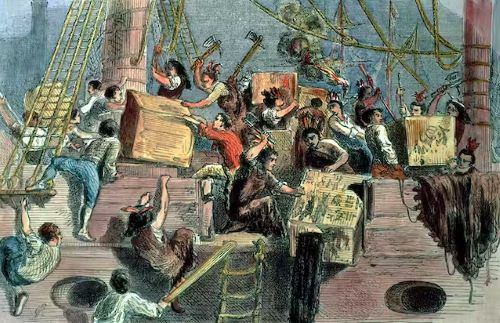

On the evening of Dec. 16, 1773, a crowd of armed men, some allegedly wearing costumes meant to disguise them as Native American warriors, boarded three ships docked at Griffin’s Wharf in Boston. In the vessels’ holds were 340 chests containing 92,000 pounds of tea, the most popular drink in America. With support from the patriot group known as the Sons of Liberty, the intruders methodically searched the ships and dumped their tea into Boston Harbor.

According to the British East India Company, whose proprietors owned the destroyed cargo, losses totaled more than a million dollars in today’s currency.

The “destruction of the tea” – as the Boston Tea Party was originally called – was the pivotal event in the coming of the American Revolution. Before Dec. 16, a peaceful resolution to American objections to Parliament’s repeated attempts to tax the Colonies without their consent seemed possible. Afterward, both British and American Colonial positions hardened. Within a year, Britain and America were at war.

An Attack on Private Property

Because it was an attack on private property, the Tea Party offended many patriots in America. When George Washington learned what had happened, he made clear he disapproved of “destroying the tea.”

Benjamin Franklin so disliked the action that he offered to pay for the East India Company’s losses himself. Samuel Adams, assumed by both his peers and modern historians to be one of the Tea Party’s organizers, never admitted to being involved.

The Original Multinational Conglomerate

Given the importance that Americans attached to property rights, why were Boston patriots willing to take such a calculated risk? The answer was the corrupt bargain that Lord North, the British prime minister, struck with the East India Company during the spring of 1773.

The East India Company was Britain’s wealthiest, most powerful corporation. The company had its own army, which was more than twice the size of the king’s regular forces. Political economist Adam Smith described the administration of its territorial empire in South Asia as “military and despotical.” Yet the company was on the verge of bankruptcy – a victim of a devastating famine in Bengal and its own corrupt administration.

North’s solution was the Tea Act. Hoping to fix Britain’s problems in both India and America, Parliament gave the East India Company a monopoly to sell 17 million pounds of tea in America at a reduced price – while keeping in place the Colonial tax on tea that Parliament had levied in the Townshend Acts of 1767. Even with the added cost of the tax, the company’s tea promised to be cheaper than tea sold by anyone else, including untaxed Dutch tea smuggled by merchants like John Hancock.

Parliament’s attempts to tax the Colonies since the Stamp Act of 1765 had largely failed. American patriots feared that the Tea Act would be a victory for British politicians who believed Parliament had the right to raise a revenue in the Colonies without the consent of Colonial representatives.

A National Response

Although the most violent resistance to the new measure occurred in Massachusetts, Boston was not alone. As opposition to the Tea Act spread, New York and Philadelphia patriots refused to allow ships with company tea to unload, forcing them to return to Britain.

Elsewhere, tea was unloaded and left on the docks to rot. After merchants in Charleston, South Carolina, paid for a shipment of tea, they were forced by local patriots to empty it into the harbor.

In Edenton, North Carolina, the resistance came from women, 51 of whom signed a petition pledging not to drink tea until the laws “to enslave this our Native Country” were repealed. Women in the port of Wilmington burned tea on the town green.

Parliamentary Anger

When news of the destroyed tea reached London, even Britons who sympathized with the American cause were appalled, in part for the same reason many Colonists objected: It was an attack on private property.

Parliament responded with three punitive laws, limiting Massachusetts’ self-government, interfering with the Colony’s courts and stopping all trade through the port of Boston until its people compensated the East India Company for the losses. Historians today remember the statutes as the Coercive Acts. Colonists called them the “Intolerable Acts.” Both descriptions were accurate.

If Parliament had responded less harshly, Americans would have had to weigh their objections to paying Parliament’s tax on tea against the discomfort that many of them felt over the destruction of private property in Boston. Eventually, the men who boarded the ships on Griffin’s Wharf might have been brought to justice.

As it happened, though, Lord North claimed Parliament had no choice. “Whatever may be the consequence,” he told the House of Commons on April 22, 1774, “we must risk something: if we do not, all is over.”

Almost exactly a year later, the government’s coercive measures, which North hoped would settle the dispute on Britain’s terms, tipped 13 of George III’s Colonies into open rebellion. Whatever Americans thought of the events on Dec. 16, the punishment imposed on Massachusetts terrified them even more, raising fears that a similar fate awaited Colonists elsewhere.

If coercion was Britain’s only choice, then the Colonists began to see that perhaps they, too, had just one choice: armed resistance, followed on July 4, 1776, by a declaration of independence.

Originally published by The Conversation, 12.13.2023, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.