Whether the judicial system can handle the intricacies of climate science remains to be seen.

By Ray Levy Uyeda

Staff Reporter

Prism

Earlier this month, the state of California announced it is suing five of the world’s largest oil and gas companies, alleging that they engaged in a “decades-long campaign of deception” to convince consumers that their product was harmless. The truth couldn’t be further from the companies’ claim, and the state hopes a courtroom will see that too. While notable for its scale and potential to set a history-making precedent, this is not the first case of its kind.

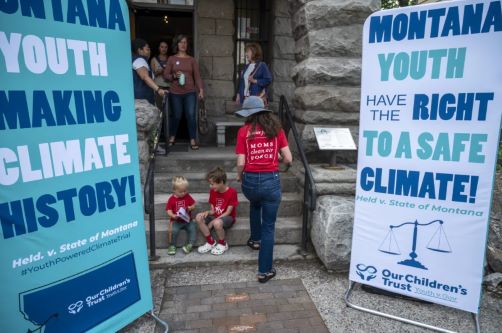

Since 2015, the cumulative number of climate change-related cases filed at local, state, and national levels worldwide has doubled to more than 2,000. Most of the defendants in these cases are either governments or fossil fuel profiteers, which plaintiffs generally claim have tacitly supported the interests of Big Oil or captured and exploited a customer base into dependency on a product that will slowly kill them.

The courtroom is not generally a place where climate wins or justice happens. The birth of the environmental justice movement in the 1980s in Warren County, North Carolina, and later across the American South paved the way outside the courts. The Black communities that fought racist placement of amenities, like landfills and toxic-waste dumps near school and poor neighborhoods, illustrated how people have always created the conditions for possibility and change, and how they have ultimately shaped justice.

Since the environmental justice movement first emerged, the consequences of climate change have ballooned in all directions. Meanwhile, government funds are stretched thin, unable to relieve the impacts and shape-shifting threats of the floods and hurricanes that are becoming features of life in places like the Gulf Coast. The rapidly changing climate system impacts first and worst the very same communities that laid the groundwork for environmental justice activism four decades ago. The problems have gotten more extreme, more expensive, and with each passing season, more intractable. Without substantive government action, activists seek redress from the courts, though there are different opinions on what the benefits might actually be.