People have always pushed back against the social expectations that constrain them.

Femininity

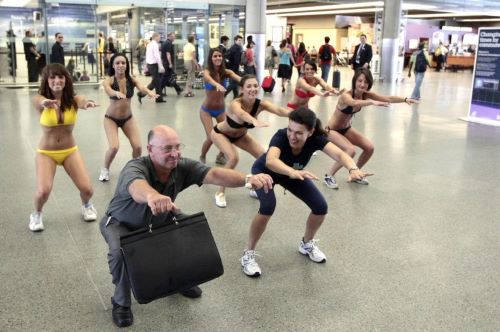

The Physical Education of Women is Fraught With Issues of Body, Sexuality, and Gender

A new book, ‘Active Bodies,’ explores the history.

Women who made a living as gym teachers—combining the “manliness” of a gym-centered life with the grace and maternal energy associated with femininity—were a puzzling sight to some, particularly before women’s professional sports existed. Gym class is now such an entrenched part of American education—and American comedy—that it seems like it’s always been with us. But in her new book, Active Bodies: A History of Women’s Physical Education in Twentieth-Century America, Bucknell University historian Martha H. Verbrugge traces the very specific history of this field, and its relationship to gendered ideas about health, bodily capabilities, and living an “active” life.

Before Woody Allen’s famous line—“Those that can’t do, teach, those that can’t teach, teach gym”—and before lowbrow dodgeball humor, there was the German, English, and American physical culture movement, a late 19th century wave of health mania inspired by a zest for competition and a belief that calisthenics and fresh air were core civilizational pressure valves.

By the early 20th century, physical education emerged as a distinct discipline and a vocation in the U.S., and it drew a varied lot of young men and women. As Verbrugge writes, before 1915, only three states required physical education. By the end of World War I, that number had grown to 28. Just over a decade later, it was 46 states. In addition to its roots in physical culture, the rise in phys ed was part of a broader national push for compulsory education, which included the formalization of attendance policies and curriculum. Exercise programs at public schools grew sharply during the first half of the 20th century, and many of the teachers were young women.

The women who found their way to the nascent field were mostly “white, native-born and middle-class,” according to Verbrugge, and their routes to phys ed were often “indirect or unplanned.” Some were athletes turning their enthusiasm for sport into a profession, others had discovered phys ed through forms of physical therapy after an injury. And still others may have been drawn at least in part by the promise of community. As Verbrugge writes, “A significant number of unmarried teachers were lesbians….Careers in recreation, physical education, and sports not only nurtured lesbians’ professional interests but also opened doors to nontraditional jobs and friendships.” Lesbianism was the field’s “open secret” (and best known stereotype) for decades, but fear of actually being accused of “deviance” was very real.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT TIMELINE

How Training Bras Constructed American Girlhood

In the twentieth century, advertisements for a new type of garment for preteen girls sought to define the femininity they sold.

In the early twentieth century, it was still something of a novelty to encounter mass-produced undergarments at all—or clothing that was specific to children. Before then, middle-class children in Europe and North America essentially wore kid-sized versions of adult clothing. “From the seventeenth to the nineteenth century,” the museum curator Anaïs Biernat wrote in the 2015 collection Fashioning the Body, “like their parents, children’s bodies were constricted by a hidden frame consisting of whalebone stays or a corset that formed a rigid structure around the torso.”

According to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), patents for softer, less restrictive alternatives to corsets were filed in the late nineteenth century and developed in the 1910s. The idea of separate undergarments for young girls developed in parallel. By the 1920s, a “junior” market for youth clothing was in full swing, as corset makers deliberately sought to turn young girls into lifelong consumers. According to the historian Jill Fields:

Manufacturers still maintained concerns that younger women in the 1920s might never wear corsets if they did not undergo the initiation into corset wearing that women had in previous generations. They looked closely at the circumstances of a young girl’s first corset fitting in order to find ways of luring young women to a corsetiere.

It wasn’t only corsets. Girdles and brassieres became part of the burgeoning youth market, with the Warner Brothers Corset Company selling a “Growing Girl” brassiere in 1917. The trend led a fashion buyer to report in the 1920s that “[s]mall sizes sell best—even the little girls wear brassieres now.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JSTOR DAILY

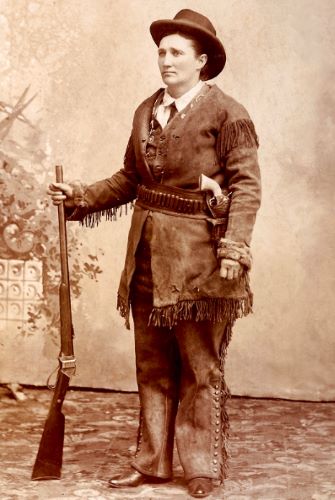

The Real Calamity Jane Was Distressingly Unlike Her Legend

A frontier character’s life was crafted to be legendary, but was the real person as incredible?

‘This is the West, Sir,’ says a reporter in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. ‘When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.’ This is very much the advice that has applied to Calamity Jane over the years. She was the lover of ‘Wild Bill’ Hickok, avenged herself on his killer and bore his secret love-child. She rode as a female army scout and served with Custer. She saved a runaway stagecoach from a Cheyenne war party and rode it safely into Deadwood. She earned her nickname after hauling one General Egan to safety after he was unhorsed in an ambush. She was a crack shot, a nurse to the wounded, a bullwhacker and an elite Pony Express courier.

Not one of these things is true. In fact, as Karen Jones sets out dismayingly early in her book, the only things that the real-life ‘Calamity Jane’ can with confidence be said to have in common with her legend is that she wore pants, swore like a sailor and was drunk all the time. Martha Jane Canary spent most of her itinerant life in grim poverty and hopelessly addicted to alcohol. She worked not as an army scout but as a camp-follower, laundress, saloon girl and occasional prostitute. As one 20th-century biographer put it crisply, her true story is ‘an account of an uneventful daily life interrupted by drinking binges’.

Karen Jones’s book, then, is a sort of dual biography: it’s the biography of Martha Canary (who checks out halfway through this book in 1903, at 47, from alcohol-induced inflammation of the bowels), and it’s the biography of the legend that grew up around her, much of it during her own lifetime and with her encouragement and collusion, and how it changed over the years that followed. She was, writes Jones, a ‘multi-purpose frontier artifact’.

The main point that Jones makes, and makes rather a lot, is that by dressing like a man and drinking in saloons and swearing and shooting things (aka ‘female masculinity’) Martha disrupted the ‘normative feminine behavior’ of the Old West. Non-academic readers might be warned that there’s a good deal of social studies jargon woven through this story. Jones is forever going on about normativity and gender performance and ‘the frontier imaginary’ (in an apt piece of linguistic cross-dressing, ‘frontier’ here serves as an adjective and ‘imaginary’ as a noun). But the material is all here, and very interesting material it is, too. There can be pretty much no reference to Calamity Jane that this diligent researcher does not find space to note: the Beano character ‘Calamity James’; My Little Pony’s ‘Calamity Mane’; ‘“Calamity” Jane Kennedy’ in the Devon-set BBC comedy drama The Coroner; and even — I was impressed by this — a trash-removal company in Margate that ‘sports an advertising insignia of a horse-drawn stage and a name founded on a stupendous use of badinage: WhipCrapAway’.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE SPECTATOR WORLD

“All the World’s a Harem”

How masks became gendered during the 1918–1919 Flu Pandemic.

Carlotta, with the drooping mouth; Esther, with the too-tilted nose, and Mary, the colleen with brown freckles, are taking full benefit of this temporary masked delusion…Carlotta, Esther, and Mary, and many other Carlottas, Esthers, and Marys, are making the most of the opportunity to show their eyes to advantage, forgetting the while about pug noses, large mouths, and freckles.

During the influenza epidemic that ravaged the United States in the fall and winter of 1918 and 1919, cities across the country advised or required masks. Soon, discussions of masks took center stage across American media. Newspapers were filled with articles explaining how to make, wear, and purchase masks. From their inception, these discussions were focused on gender, and women in particular: how were women adjusting to the new normal? What was the public’s perception of women wearing masks? Readers of the October 29, 1918 edition of The Seattle Star got a peek into this new narrative in the quote above, implying women with less-than-desirable facial traits should be grateful for the temporary reprieve flu masks provided.

This stereotype of women wearing masks found expression in a cartoon published in the Muncie Evening Press on October 23, 1918. In this cartoon, a male patient pretends to have the influenza “just to get that pretty little nurse around and here she is wearing a mask.” Yet in the final frame, when the nurse removes the mask, which she is “sick of wearing,” she turns out to be less attractive than the male patient has imagined — leading him to announce, “Me? I’m cured!” This cartoon reinforced stereotypes as it sexualized the nurse’s appearance, ignoring her professional role. In the context of the 1918 influenza epidemic, however, this cartoon also illustrates how the image of the masked nurse became part of daily experience.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NURSING CLIO

Nevertheless, She Lifted

A new feminist history of women and exercise glosses over the darker side of fitness culture.

Danielle Friedman’s new book Let’s Get Physical traces the recent history of women’s fitness in the United States, primarily through a series of biographical sketches of women who, like Prudden, have shaped that history. Each chapter centers on a woman, or several, who pioneered a major fitness trend in a given decade. The first chapter focuses on Prudden, detailing her research on children’s fitness, her many popular books promoting exercise for women, her prison program and its accompanying New York Times coverage, and her TV show. Later chapters focus on Lotte Berk, the originator of the barre workouts that emerged in the 1960s, and, of course, Jane Fonda’s ’80s aerobics.

Friedman’s lively anecdotes about these women and their early followers are fun to read. The book presents a dynamic cast of characters, many of whom are little-known now, like Lisa Lyon, a bodybuilder who posed for Playboy and was profiled by Eve Babitz in Esquire (Babitz wrote that she had a “perfect little Bardot-Ronstadt face”); or Janice Darling, an instructor at Jane Fonda’s original workout studio who was one of the few Black fitness instructors of the era and who credited her fitness routine with helping her recover from an accident that broke both her legs and severed a muscle in one eye. It’s fun, too, to gawk at the now obviously ridiculous sexism many of them faced. Friedman writes, for instance, that for decades women were discouraged from exercising because it was believed that too much exercise could make their uteruses fall out.

Friedman clearly views the telling of this history as a feminist project. As she writes, “American women’s fitness history is more than a series of misguided ‘crazes.’ It’s the story of how women have chosen to spend a collective billions of dollars and hours in pursuit of health and happiness. In many ways, it’s the story of what it has meant to be a woman over the past seven decades.” She is right that exercise is a significant concern for many women, and so there is a feminist stake in refusing to dismiss or overlook its history. But the fact that there is a compelling feminist argument for studying the history of women’s fitness does not make that history, in and of itself, feminist—something Friedman’s book struggles to grasp.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE BAFFLER

The Fitness Craze That Changed the Way Women Exercise

Fifty years after Jazzercise was founded, it is still shaping how Americans work out—for better or for worse.

While exercise spaces for women existed at the time, they often assumed that women valued prettiness and poise over feeling powerful. As early as the 1930s, a Chicago “figure salon” invited women to “soothe the nerves and control the curves,” according to a 1936 piece in the Chicago Tribune. For decades, these businesses were largely owned by men, whose rationale for sex segregation—such as having “ladies’ days” at the bodybuilder Vic Tanny’s chain of clubs—was more about maintaining proper distance between the sexes than enabling women to freely enjoy exercise.

But ideas about women’s bodies and who should have agency over them, at the gym and elsewhere, were changing. New research touted the benefits of aerobic exertion, expanding the popular understanding of exercise to include arenas outside of smelly weight rooms. Many proponents of women’s liberation sought to obliterate old ideas about female frailty and celebrated what women’s bodies could do, whether breastfeeding or playing basketball. Along with Missett, women such as Jacki Sorensen, who developed the competing “aerobic dancing,” and Lydia Bach, who imported Lotte Berk’s barre workout from London, infused this philosophy into exercise.

Jazzercise, with its mostly female clientele and high-energy vibe, was of this moment that Missett seized and helped shape. Her family relocated to San Diego in 1972, where a body-conscious health culture was kicking up. Military wives packed Missett’s classes, which she said she taught so frequently that she nearly permanently lost her voice. When her students’ husbands were reassigned, many of these women were so heartbroken imagining life without Jazzercise that Missett created an official certification program, and then a franchise system, turning exercise into employment for thousands of women and creating global brand ambassadors before such a term existed.

Thousands of letters Missett has saved relay how Jazzercise moved women not only to lose inches, but also, in some cases, to leave abusive husbands, demand raises, and generally find joy in their bodies and lives. Jazzercise’s empowerment effect could be especially intense, because enjoying classes could become a career (more than 90 percent of franchisees begin as students; even more are women). I’ve interviewed women whose first solo travel, in their 30s, was to a Jazzercise convention. They found in the franchise a rare opportunity for employment and camaraderie that fit in with the demands of child-rearing. Missett relishes such stories of how Jazzercise has enabled women’s economic independence, including her own: She gleefully recounts a triumph in 1975 over a sexist Parks and Rec bureaucrat who balked at writing a big paycheck to a “little exercise girl.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE ATLANTIC

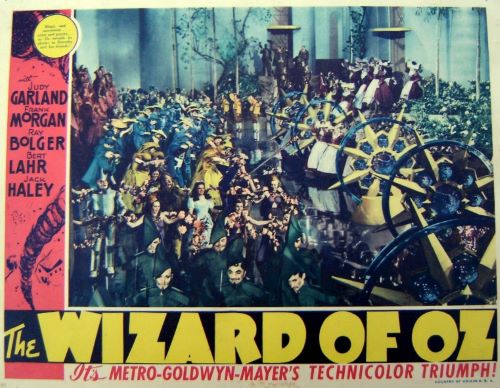

“The Wizard of Oz” Invented the “Good Witch”

Eighty years ago, MGM’s sparkly pink rendering of Glinda expanded American pop culture’s definition of free-flying women.

Delving into the provenance of Glinda’s character reveals a lineage of thinkers who saw the witch as a symbol of female autonomy. Though witches have most often been treated throughout history as evil both in fiction and in real life, sentiments began to change in the 19th century as anticlerical, individualist values took hold across Europe. It was during this time that historians and writers including Jules Michelet and Charles Godfrey Leland wrote books that romanticized witches, often reframing witch-hunt victims as women who’d been wrongfully vilified because of their exceptional physical and mystical capabilities. Per Michelet’s best-selling book, La Sorcière of 1862: “By the fineness of her intuitions, the cunning of her wiles—often fantastic, often beneficent—she is a Witch, and casts spells, at least and lowest lulls pain to sleep and softens the blow of calamity.”

The ideas of Michelet and like-minded writers influenced Matilda Joslyn Gage, an American suffragist, abolitionist, and theosophist. She posited that women were accused as witches in the early modern era because the Church found their intellect threatening. “The witch was in reality the profoundest thinker, the most advanced scientist of those ages,” she writes in her feminist treatise of 1893, Woman, Church, and State. Her vision of so-called witches being brilliant luminaries apparently inspired her son-in-law, L. Frank Baum, to incorporate that notion into his children’s-book series about the fantastical land of Oz. (Some writers have surmised that “Glinda” is a play on Gage’s name.)

Like Gage, Baum was a proponent of equal rights for women, and he wrote several pro-suffrage editorials in the South Dakota newspaper he owned briefly, the Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer. Although his book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published in 1900, is titled after a man, it is fundamentally a female-centric story: a tale about a girl’s journey through a land governed by four magical women. There are actually two good witches in Baum’s original version: Glinda is the witch of the South, not the North, in his telling, and she doesn’t appear until the second-to-last chapter. The book states that she is not only “kind to everyone,” but also “the most powerful of all the Witches.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE ATLANTIC

An Investigation Into the History of the ‘Ditz’ Voice

How pitch, tonality, and celebrity imitation have portrayed cluelessness.

In January, Saturday Night Live aired a sketch spoofing The Bachelor, one of many they’ve done throughout the reality juggernaut’s time on air.

Bachelor contestants adhere to a long-established archetype in the public consciousness: the vapid gold-digger who needs a man to make her life complete. Most of the cast members depicting the contestants adopted a certain speaking style: monotonous, with elongated ending syllables and a lot of vocal fry, in line with the voice associated with “ditzy” girls today. But host Jessica Chastain’s interpretation was slightly different: her voice had a higher pitch and a little more musicality—more AMC than ABC. Though it sounded old-fashioned, it was clearly recognizable as part of a library of voices women have pulled from over the years to play silly, sappy, or simpering women.

A version of this voice has existed since sound met film and, in a way, since a little before that. Actresses of early film played mostly damsels in distress or wide-eyed young women, and by the time talkies took over, women were still portrayed as less headstrong, more head-in-the-clouds. “The 1920s had a serious case of the cutes,” notes Max Alvarez, a New York-based film historian. “There is a prevalence of childlike women in the popular culture [at the time] … Girlish figures, girlish fashion, girlish behavior.” Along with these girlish figures came a girlish voice—high-pitched, a bit breathy, and a little bit unsure, evident in Clara Bow’s pouty purr, and even Betty Boop’s singsong.

Shortly after the advent of sound in cinema, the scrappy, spunky flappers of the ‘20s were relegated to supporting characters—“the gangster’s moll, the cocktail waitress,” says Alvarez. Musicals of the era, says Alvarez, were bastions of these kinds of wise-cracking wacky sidekicks. “Anything with a backstage Broadway setting, you’re gonna find these women.” The speaking voices filling these film’s chorus lines were still childlike as in the decade prior, but started to show signs of the modern-day “sexy baby voice”: a little bit breathy, a little bit nasal, and with fewer harsh consonant sounds.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT ATLAS OBSCURA

The Failed Promise of the Aerobics Revolution

A new dramedy on Apple TV+ explores the roots of America’s fitness craze.

Revolutions don’t always happen in the streets. In the early 1980s, a seismic shift took place in strip-mall storefronts that smelled of sweat and Enjoli. Pulsing to the beat of Donna Summer and glistening with spandex, these fluorescent-lit rooms vibrated with the energy of career women and housewives bouncing in unison.

Aerobics was liberation. It offered a way for millions of women to feel proud of what their bodies could do, not just how they looked.

My mom was one of these women. She was intrigued at first by aerobics’ promise to help her lose the weight she had gained during her pregnancy with me, and then she found that she loved the music, the energy, the adult camaraderie.

One particularly challenging day at home caring for my older sister and me, she told me later, she was counting down the hours until my dad’s return from work, when she could leave for aerobics. She was already in her leotard, tights, and sweatband when he called to remind her he had to stay for a meeting that night — she’d have to miss her class. She sat down at the kitchen table and wept. Taking in the ridiculous combination of her Lycra and tears only made her cry harder. Aerobics, she realized, had become integral to her identity as a woman, independent from her roles as wife and mother.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK TIMES

Sluts and the Founders

Understanding the meaning of the word “slut” in the Founders’ vocabulary.

“A lady who has been seen as a sloven or slut in the morning will never efface the impression she then made with all the dress and pageantry she can afterwards involve herself in,” Thomas Jefferson wrote to his daughter Patsy, then eleven, in December 1783. “Nothing is so disgusting to our sex as a want of cleanliness and delicacy in yours. I hope therefore the moment you rise from bed, your first work will be to dress yourself in such a stile as that you may be seen by any gentleman without his being able to discover a pin amiss, or any other circumstance of neatness wanting.”

It’s safe to say that “gentle parenting” enthusiasts wouldn’t approve of his approach, but Martha, Patsy’s mother, may have. When Jefferson wrote those words, he was less than a year into grieving her. Martha’s own mother died when she was two, and by the time she was twelve she had buried two stepmothers. Historians know little about her relationships with them, but we do know she wanted to protect her children from a similar fate. As she lay on her deathbed, witnesses—including Sally Hemings, Martha’s enslaved half-sister who would go on to have six of Jefferson’s children—would remember her making an astonishing request:

When she came to the children, she wept and could not speak for some time. Finally she held up her hand, and spreading out her four fingers, she told him she could not die happy, if she thought that her four children were ever to have a stepmother brought over them. Holding her hand, Mr. Jefferson promised her solemnly that he would never marry again. And he never did.

As Annette Gordon-Reed writes in The Hemingses of Monticello, “That Jefferson at age thirty-nine promised not to do so extraordinary.” But as Gordon-Reed brought to light, he didn’t spend the rest of his life alone.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT STUDY MARRY KILL

Casimir Pulaski, Polish Hero of the Revolutionary War, Was Most Likely Intersex

Disputed remains were the right height and age and showed injuries consistent with the general’s life. There was just one catch: The skeleton looked female.

He is called the “father of the American cavalry,” a Polish-born Revolutionary War hero who fought for American independence under George Washington and whose legend inspired the dedication of parades, schools, roads and bridges.

But for more than 200 years, a mystery persisted about his final resting place. Historical accounts suggested the cavalryman, Casimir Pulaski, had been buried at sea, but others maintained he was buried in an unmarked grave in Savannah, Ga.

Researchers believe they have found the answer — after coming to another significant discovery: The famed general was most likely intersex.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORK TIMES

Ida Lewis, “The Bravest Woman in America”

In her thirty-two years as the keeper of Lime Rock Lighthouse, Ida Lewis challenged gender roles and became a national hero.

Ida Lewis, the namesake of Arlington National Cemetery’s Lewis Drive, was once known as “the bravest woman in America.” Lewis served as an official lighthouse keeper for the U.S. Lighthouse Service (later absorbed into the Coast Guard) from 1879 until her death, at age 69, in 1911. As the keeper of Lime Rock Light Station off the coast of Newport, Rhode Island, Lewis performed work that was critical to national security: lighthouses, administered by the federal government, aided navigation and helped protect the nation’s coastlines.

Lewis also performed personal acts of heroism by rescuing people from drowning in the turbulent, cold waters off Newport. According to Coast Guard records, Lewis saved the lives of 18 people, including several soldiers from nearby Fort Adams; unofficial accounts hold that she saved as many as 36. Until 2020, she was the only woman to receive the Coast Guard’s Gold Lifesaving Medal, the nation’s highest lifesaving decoration.

When ANC dedicated its 27-acre Millennium site in 2018, Lewis became the first woman honored with a road in the cemetery named for her. Ida Lewis Drive runs between Section 29 and Sections 77–84, the new sections created with ANC’s Millennium Project expansion, in the northwest of the cemetery. Lewis herself is buried at Island Cemetery in her birthplace of Newport, near the lighthouse she once managed.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Valentina Tereshkova and the American Imagination

Remembering the Russian cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman in space, and how she challenged American stereotypes.

The first woman in space was the cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, who launched on June 16th, 1963. Her craft, Vostok 6, orbited the planet forty-eight times over three days. Tereshkova’s achievement was one of great pride and propaganda value for the U.S.S.R.—and confusion and consternation for the U.S.A.

For one thing, she didn’t fit American’s Cold War-era stereotypes of Soviet women. One such stereotype, as historian Robert L. Griswold reveals, was the “graceless, shapeless, and sexless” Russian working class woman. Many Americans imagined female Soviets as miserable and shabby, suffering from bad clothes and makeup, thanks to their inferior form of government. According to Griswold, by the late 1950s, the “American conception of Soviet working class femininity became a way to reassert the boundaries of proper womanhood” which, after World War II in the US, no longer had a place for “Rosie the Riveter.”

Then there was the stereotype of the apolitical matron, informed by Nina Khrushcheva, partner of Nikita Khruschev. Practically everybody liked “Mrs. K.” when she toured the U.S. in 1959. Although she was in fact “a revolutionary in her own right,” in the eyes of the American media she “became a kind of world grandmother who focused on her family and had little interest in Kremlin intrigue.” Griswold writes that in this case, conservative Baby Boomers’ maternal ideology was more powerful than anti-Communism.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JSTOR DAILY

Jenny Zhang on Reading Little Women and Wanting to Be Like Jo March

From the moment I learned English—my second language—I decided I was destined for genius and it would be discovered through my writing—my brilliant, brilliant writing. Until then, I had to undergo training, the way a world-class athlete might prepare for the Olympics; so I did what any budding literary marvel desperate to get to the glory and praise stage of her career would do—I read and read and read and then imitated my idols in hope that my talents would one day catch up to my tastes.

At age ten, I gave up picture books and took the leap into chapter books, but continued to seek out the girly subjects that alone interested me. Any story involving an abandoned young girl, left to survive this harsh, bitter world on her own, was catnip to my writerly ambitions. Like the literary characters I loved, the protagonists in my own early efforts at writing were plucky, determined, unconventional girls, which was how I saw myself. They often acted impetuously, were prone to bouts of sulking and extreme mood swings, sweet one minute and sour the next.

I always gave my heroines happy endings—they were all wunderkinds who were wildly successful in their artistic pursuits and, on top of it, found true, lasting love with a perfect man. I was a girl on the cusp of adolescence, but I had already fully bought into the fantasy that women should and could have it all.

On one of my family’s weekly trips to Costco, I found a gorgeous illustrated copy of Little Women by Louisa May Alcott, a book I had seen and written off every time I went to the library, repelled by the word women. Unlike the girl heroines I loved, a woman was something I dreaded becoming, a figure bound up in expectations of sacrifice and responsibility. A woman had to face reality and give up her foolish childish dreams. And what was reality for a woman but the life my mother—the best woman I knew—had? And what did she have but a mountain of responsibilities—to me, to my father, to my younger brother, to her parents, to my father’s parents, to her friends, to my father’s friends, to their friends’ parents, to her bosses, to her coworkers, and so on?

Her accomplishments were bound up in other people, and her work was literally emotional, as she was expected to be completely attuned to everyone else’s feelings. She worked service jobs where she was required to absorb the anger of complaining customers and never betray any frustration of her own. Her livelihood depended on being giving and kind all of the time, suppressing her less sunny emotions into a perpetually soaked rag that she sometimes wrung out on my father and me.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LITERARY HUB

Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight

The aviation pioneer was many things before—and after—her career as a pilot was cut short.

There were, in fact, other famous female aces in the early decades of aviation. All of them were daring—some were said to be better pilots than Earhart—and many of them were killed and forgotten. If Earhart became an “icon,” it was, in part, because women who aspired to excel in any sphere, at a high altitude, looked upon her as their champion. But it was also because the unburied come back to haunt us.

Earhart had already tried to circle the globe once in 1937, flying westward from Oakland, but she had crashed taking off in Honolulu. Determined to try again, she coaxed additional funds from her sponsors, and “more or less mortgaged the future,” she wrote. The plane, hyped as a “flying laboratory” (it wasn’t clear what she planned to test, beyond her own mettle and earning power), was shipped back to California for repairs, and, once Putnam had renegotiated the necessary landing clearances and technical support, she and Noonan set off again, on June 1st, this time flying eastward—weather patterns had changed. A month and more than twenty-two thousand miles later, they had reached Lae, New Guinea, the jumping-off place for the longest and most dangerous lap of the journey. The Electra’s fuel tanks could keep them aloft for, at most, twenty-four hours, so they had almost no margin of error in pinpointing Howland, about twenty-five hundred miles away. Noonan was using a combination of celestial navigation and dead reckoning. They had a radio, but its range was limited.

Early on July 2nd, on a slightly overcast morning, about eighteen hours into the flight, Earhart told radiomen on the Itasca, a Coast Guard cutter stationed off Howland to help guide her down, that she was flying at a thousand feet and should soon be “on” them, but that her fuel was low. Although the Itasca had been broadcasting its position, so that Noonan could take his bearings and, if necessary, correct the course, they apparently couldn’t receive the transmissions, nor apparently could they see the billows of black smoke that the cutter was pumping out. Earhart’s last message was logged at 8:43 A.M. No authenticated trace of the Electra, or of its crew, has ever been found.

After twenty-five years of research, the Longs concluded that “a tragic sequence of events”—human error, faulty equipment, miscommunication—“doomed her flight from the beginning,” and that Earhart and Noonan were forced to ditch in shark-infested waters close to Howland, where the plane sank or broke up. There is, however, an alternative scenario—a chapter from Robinson Crusoe. It is supported with methodical, if controversial, research by Ric Gillespie, the author of “Finding Amelia” (2006), which has just been republished.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE NEW YORKER

The Sorry History of Car Design for Women

A landscape architect of the 1950s predicted that lady drivers would want pastel-colored pavement on the interstate.

In 1958, landscape architect A. Carl Stelling tried to calm the fears of a public that would soon be connected by the interstate highway system. It wasn’t just anxiety about what these new roadways would mean for communities that was on people’s minds, there was also concern about exactly who would be using the highways. As Stelling wrote, “Say what you will—and all of us have—you are going to see more and more of the woman driver.” He added, “This prospect is not as catastrophic as it may appear.”

Stelling predicted that this new crop of “timid” and “panicky” drivers would spark changes to current roadways. Feminine pastel colors would “replace the drab, monotonous tones of present-day pavement”; designs would include an extra-slow, truckless lane for “women who become nervous at high speeds”; and wider travel lanes would allow women “a greater margin of error in their maneuvering.”

Stelling was hardly the first—or the last—to ask about the role of gender in the car industry. As sociologist Diane Barthel-Bouchier writes: “From their beginnings at the end of the nineteenth century, automobiles were defined as masculine.” The electric car, for example, was initially seen as a “ladies’ car for gadding about the city,” compared to the more “manly” gas-powered option.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JSTOR DAILY

We See You, Race Women

We must dive deeper into the intellectual artifacts of black women thinkers to support the evolution of black feminist discourse and political action.

When I was in graduate school, whenever a black woman scholar presented her work a peculiar phenomenon emerged: peers always and only remarked on the speaker’s person, rather than on her ideas. At almost no time did auditoriums or classrooms pour out with chatter about the scholarly intervention we’d just witnessed. Instead, fellow students talked about the often senior and sometimes advanced mid-career expert’s hair, clothing, impressive physical presence, or overall beauty.

The issue at hand is not that these speakers—visiting and core faculty from our university and leaders in their fields—were not attractive women, but that the intellectual production of these women did not provide the foundation for my colleagues’ attraction. Fellow graduate students could only observe these black women’s bodies. My peers were accidentally or willfully blind to black feminine scholarly production. In other words, these black women were intellectually illegible to my colleagues.

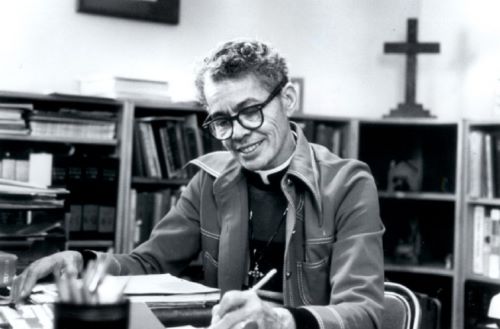

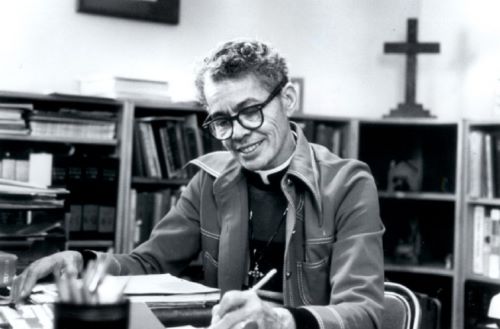

It is precisely this phenomenon of black women’s political, intellectual, and social illegibility that Brittney C. Cooper takes up in Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women, published last May. Cooper begins her critical intellectual history of black women thinkers and activists from the turn of the century through the 1970s by making the stakes of her study quite clear. She is not interested in charting only the biographies of the core figures in her work: Fannie Barrier Williams, Mary Church Terrell, and Pauli Murray. Instead, Cooper moves beyond biography to call for and demonstrate an in-depth analysis of literary production, philosophies, and direct political actions of these public intellectual “race women” and the women with whom they built robust proto-black-feminist discourses, frameworks, and blueprints.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT PUBLIC BOOKS

Voices in Time: Epistolary Activism

An early nineteenth-century feminist fights back against a narrow view of woman’s place in society.

In the summer of 1837, Angelina and Sarah Grimké were traveling in eastern Massachusetts. The white, South Carolina–born sisters were working on behalf of the American Anti-Slavery Society, lecturing and organizing to end slavery immediately in the southern United States. During their travels in New England, they drew the ire of the conservative wing of the Massachusetts Congregational ministry, which opposed the immediate abolition movement. In July a pastoral letter was read from Congregational pulpits across the state condemning women who entered what was called the “public sphere” to give speeches supporting “reform.”

The attacks did not surprise the sisters. When they first began speaking in public about slavery six months earlier in New York City, many privately told them that they should stop. The sisters’ actions were indeed groundbreaking. While Frances Wright and Maria Stewart had given reform lectures earlier, neither had taken to the road on behalf of a single controversial reform. Catharine Beecher, prominent female educator, did not approve. Like the conservative Massachusetts Congregational clergy, she and her famous father, the Congregational minister Lyman Beecher, supported sending African Americans to Africa as a solution to slavery and opposed the immediate abolition movement.

In May 1837 Catharine published a pamphlet criticizing that movement as seriously misguided and Angelina Grimké, with whom she had been friends in the 1820s, for violating woman’s God-given place as subordinate to men. In response to Beecher’s pamphlet, Angelina published her own, in the form of a series of letters. The first letter was published in June in several reform newspapers. Two of the last three letters dealt with women’s equality and were as much a response to the pastoral-letter controversy as to Beecher’s limited vision for women. In the second-to-last letter, the first half of which is reprinted here, Angelina sets aside Beecher’s arguments and forthrightly states her own regarding women’s full human equality.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LAPHAM’S QUARTERLY

American Women’s Obsession With Being Thin Began With This ‘Scientist’

Greta Garbo and Marlene Dietrich were hooked on his diet.

Bengamin Gayelord Hauserwasn’t the first diet guru to worm his way into Western women’s collective consciousness. The dieting advice of William Banting, an English undertaker turned anti-fat crusader, was so influential in Victorian-era London that his surname became a verb, synonymous with dieting (i.e., “I’m banting”). Hauser also wasn’t the first to count celebrities among his followers. John D. Rockefeller and Franz Kafka were both devoted “Fletcherites,” convinced that chewing a mouthful of food 100 to 700 times resulted in improved health and a slimmer body shape, while Henry Ford was a Hay man (à la Dr. William Hay) who never ate starch and protein at the same meal.

What Hauser managed to do that Banting, Fletcher, and Hay couldn’t was capitalize on the fears and desires of women in postwar America. Unlike women of previous generations, those in the first half of the 20th century had fewer children, better health, longer lives, and more disposable income. Middle age, in particular, no longer meant retreating into a housecoat and waiting to die. Now women “could afford to have a new sense of optimism about what life over fifty could be,” writes Catherine Carstairs in her 2014 article for the journal Gender & History, “‘Look Younger, Live Longer’: Ageing Beautifully with Gayelord Hauser in America, 1920–1975.”

Hauser’s approach to diet and nutrition emphasized that living a healthful life meant travel and dancing and enjoying small pleasures. He gave women of a certain age permission not just to exist publicly but to be the center of attention. To be in the spotlight, though, was a privilege that only those who were beautiful and slim and took special care to adhere to a healthy diet deserved. “There is real tragedy in fat,” Hauser wrote in 1939’s Eat and Grow Beautiful.

How to get and stay slim? Hauser came up with a number of approaches in the 50 years of his career, including juicing, eating according to one’s “type” (potassium, phosphorus, calcium, and sulphur), avoiding white bread, sugars and over-refined cereals, and preparing “healthful” recipes like the “pep breakfast”: two raw eggs beaten in orange juice to create, as he writes in his most famous book, Look Younger, Live Longer (1951), a “creamy drink fit for a King’s table.” Most important of all, don’t skimp on the “wonder foods,” advocated Hauser, including yogurt, powdered skim milk, brewer’s yeast, wheat germ, and blackstrap molasses.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT TIMELINE

As Swimsuit Season Ends, Pursuit of the ‘Bikini Body’ Endures

The “bikini body” is out. But the pressure to maintain the ideal female physique lives on.

I was 16 when I bought my first bikini at the mall. It was a reward. That morning, when I knew my stomach was flattest, I had lain on my bed, taken a deep breath and rested a ruler across my hips. Just barely, but sure enough, there was space between the plastic and my flesh. I deserve this, I thought, as I proudly plunked down the money I had earned scooping ice cream to pay for the few inches of shiny purple fabric. I had finally achieved the “bikini body” plastered on the pages of the teen magazines I pored over.

More than 20 years later, the anecdote makes me cringe. Openly aspiring to attain a “bikini body” has become shorthand for a slavish, self-hating fealty to a set of beauty standards decidedly out of step with the “empowerment branding” that today predominates in the fitness industry. Women’s Health banned the phrase from its cover in 2015, and a ubiquitous meme on the body-positive Internet reminds women that a “bikini body” is, well, any body that happens to be wearing a two-piece.

Yet ditching the phrase hasn’t destroyed its underlying ethos. Consider that the most popular global fitness celebrity is arguably Australian Kayla Itsines, whose “bikini body army,” armed with old-school before-and-after photos, is over 10 million strong.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

Masculinity

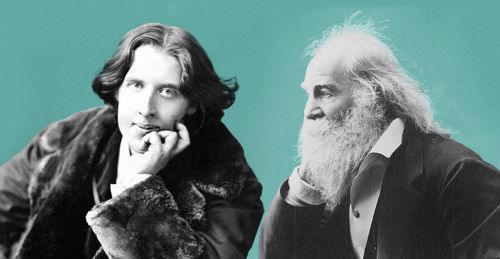

When Wilde Met Whitman

As he told a friend years later, “the kiss of Walt Whitman is still on my lips.”

The 19th century was fixated on manhood. Much has been written about the constraints on Victorian women but gender expectations for men were no less real, although less pronounced. The debates swarming around Wilde were personal, but they also touched on fundamental questions about what made a man a man. Poetry was a battleground for masculinity, and Wilde had entered the fray.

“What is a man anyhow?” a then little-known poet called Walt Whitman asked at mid-century. His reply came in the form of Leaves of Grass, an 1855 poetry collection that sought to establish the nobility of the American working man. Whitman’s inclusive spirit and comprehensive range made his poetry nothing short of revolutionary. When he pictured seamen and horsedrivers, gunners and fishermen, he praised their blend of “manly form” with “the poetic in outdoor people.” Likewise, he assured readers that the ripple of “masculine muscle” definitely had its place in poetry. In Whitman”s book, a working poet could be as manly as marching firemen, and wrestling wrestlers could be just as poetic. Every working man could represent what he triumphantly called “manhood balanced and florid and full!” He redefined who counted as a real man.

It wasn’t long before the essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson was writing to congratulate Whitman. Emerson had given much thought to these matters. Decades earlier, in his celebrated 1837 “American Scholar” speech, he had observed that society rarely regarded a man as a whole person, but reduced him to less than the sum of his parts. Now Whitman’s poetry had restored men to their whole potential. Leaves of Grass “meets the demand I am always making,” Emerson told Whitman in 1855, praising his exceptionally brave handling of his materials. Here, finally, was an American poet who embraced the totality of man, and celebrated him as a fully embodied individual. “I greet you at the beginning of a great career,” Emerson wrote him.

For a long time, sexuality had been excluded from literature. No more. “I say that the body of a man or woman, the main matter, is so far quite unexpressed in poems; but that the body is to be expressed, and sex is,” Whitman replied to Emerson. The place to do it, he said, was in American literature. And the way to do it was by writing the truth about men’s appetites, and rejecting the fiction known as “chivalry.” At one time, chivalry designated medieval men-at-arms, but in Wilde’s lifetime, it meant idealized gallantry, especially towards women, and a willingness to defend one’s country. To Whitman, the notion felt clankingly old-fashioned. ”Diluted deferential love, as in songs, fictions, and so forth, is enough to make a man vomit,” he thought. Replace it with a truer picture of love and human nature, Whitman said, and “this empty dish, gallantry, will then be filled with something.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LITERARY HUB

How John Wayne Became a Hollow Masculine Icon

The actor’s persona was inextricable from the toxic culture of Cold War machismo.

In the long working “friendship” between the two men, unless I missed it, Ford never spared a kind word for his protégé. In fact, Ford was savage in his mistreatment of Wayne, even though—or because?—Wayne worshipped him. (“My whole set up was that he was my mentor and my ideal! I think that deep down inside, he’s one of the greatest human beings that I have ever known.”) From Stagecoach through Liberty Valance, their last Western together, Ford rode Wayne so mercilessly that fellow performers—remarkably, given the terror Ford inspired—stepped in on Wayne’s behalf. Filming Stagecoach, Wayne revealed his inexperience as a leading man, and this made Ford jumpy. “Why are you moving your mouth so much?” he demanded, grabbing Wayne by the chin. “Don’t you know that you don’t act with your mouth in pictures?” And he hated the way Wayne moved. “Can’t you walk, instead of skipping like a goddamn fairy?”

Masculinity, says Schoenberger, echoing Yeats, was for Ford a quarrel with himself out of which he made poetry. Jacques Lacan’s definition of love might be more apt: “Giving something you don’t have to someone who doesn’t want it.” Ford was terrified of his own feminine side, so he foisted a longed-for masculinity on Wayne. A much simpler creature than Ford, Wayne turned this into a cartoon, and then went further and politicized it. There was an awful pathos to their relationship—Wayne patterning himself on Ford, at the same time that Ford was turning Wayne into a paragon no man could live up to.

Of all the revelations in Schoenberger’s book, none is more striking than this: After Stagecoach, a critical and commercial success, Wayne disappeared into mostly unmemorable films for another nine years. It was only in 1948, in the film 3 Godfathers, that John Wayne at last began to resemble the image we have of him in our heads. He was the apotheosis of a Cold War type—unsentimental, hard, brutal if necessary, proudly anachronistic, a rebuke to the softness of postwar affluence. He was turning, in other words, from an artist into a political symbol. “Unlike Ford,” Schoenberger says, “he ended up making propaganda, not art.” Wayne was an unyielding anticommunist; by binding up his screen image with his “ultra-patriotism,” as Schoenberger calls it, he posed himself against a liberal establishment that was feminized, and therefore worthy of populist disgust.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE ATLANTIC

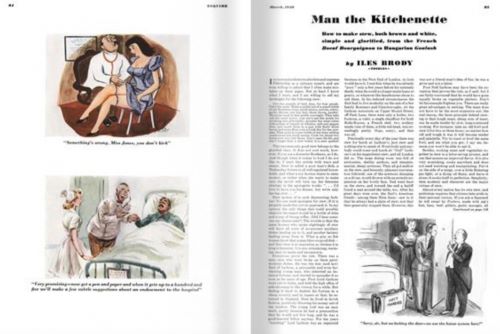

When Salad Was Manly

Esquire, 1940: “Salads are really the man’s department… Only a man can make a perfect salad.”

The differences between “women’s tastes” and “men’s tastes” are long entrenched in American cultural history. As the stereotype goes, meat is manly and women love salad.

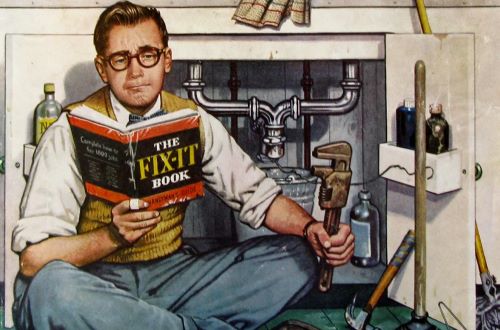

Or is it that simple? A look back at the food writing directed at men in the period following the Second World War reveals a different relationship between men and salad. In this era, making and eating a salad wasn’t frilly and feminine, but was actually one of the most masculine things a man could do.

In a 1940 installment of his long-running Esquire cooking column “Man the Kitchenette,” Iles Brody writes: “salads are really the man’s department… Only a man can make a perfect salad,” which was “never sweet and fussy like a woman’s.” Given the right context, self-confidence, and ingredients, a man could transcend the girly boundaries of vegetables, reasserting his dominance in the kitchen and in his relationship to women. A growing body of instructional literature aimed to teach him how to do it.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JSTOR DAILY

The Masculinization of Little Lord Fauntleroy

The 1936 movie Little Lord Fauntleroy broke box office records, only to be toned down and masculinized amid cultural fears of the “sissified” male.

“With men and women at a late hour forming long lines in front of the box office, the management of the world’s largest theater late tonight announced the initial production from Selznick International would be held over for a second week by popular demand,” The Los Angeles Times reported in 1936. The production in question was Little Lord Fauntleroy, and by the newspaper’s account, crowds were braving terrible spring weather to see it. New York City moviegoers muddled through a “slashing rainstorm,” while Buffalo audiences tunneled out of “record-breaking snowstorms.” In Denver, too, there was heavy snow. Perhaps the most devoted fans were in Philadelphia and Cincinnati. Both cities were hit with floods, which did nothing to stop the ticket sales.

No matter where Little Lord Fauntleroy opened and no matter the forecast, there were broken box office records and “standing room crowds.” It was a testament to the enduring popularity of the character, an aristocratic young boy created by author Frances Hodgson Burnett. Yet, curiously, even as men and women were racing through the rain to see the production, there was backlash building. Little Lord Fauntleroy not only entered the slang lexicon as an insult, but inspired a panic among certain parents, who feared their sons might turn out “priggish,” “sugary,” or, as all these coded words seemed to suggest, emasculated.

Little Lord Fauntleroy debuted as a serialized children’s story in St. Nicholas Magazine in 1885. It was later collected into a book, “which vastly outsold masterpieces such as Tolstoy’s War and Peace” and became “a trans-Atlantic best-seller prized by a dual readership of adults and children,” Princeton professor U. C. Knoepflmacher writes. The story concerned a boy named Cedric Errol, born to an American mother and a British nobleman. Shunned by the snobby English side of the family, Cedric and his mother struggle to make ends meet in New York City after his father’s passing.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JSTOR DAILY

The Right Worries Minnie Mouse’s Pantsuit Will Destroy Our Social Fabric. It Won’t.

Of mice and men.

The recent announcement that Minnie Mouse has joined Pantsuit Nation, or at least Pantsuit Magic Kingdom, temporarily swapping her red dress for a polka-dot pantsuit designed by Stella McCartney, triggered a mini-meltdown on Fox News. Conservatives tend to be, by definition, change-adverse. Minnie’s new clothes — coming on the heels of culture-war skirmishes over the green M & M’s “progressive” sneakers and Hasbro’s dropping of the “Mr.” from Mr. Potato Head — may have been the straw that broke Candace Owens’s brain. The right-wing pundit went on “Jesse Watters Primetime” to slam Disney for making Minnie “more masculine” in an attempt to “destroy fabrics of our society” — an interesting Freudian slip, conflating “fabrics” (that is, textiles) with the social “fabric,” or structure.

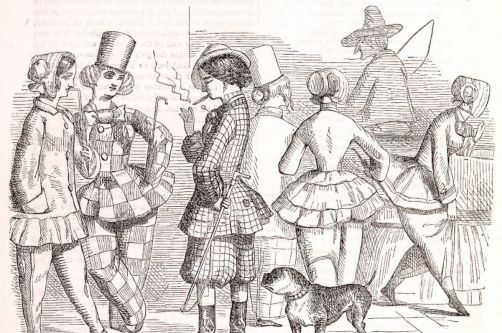

Of course, as many pointed out on social media, Minnie has worn pants (and shorts) in the past. And at least she’s fully clothed, unlike some pantsless male Disney characters. (Looking at you, Winnie the Pooh and Donald Duck). But the move still riled the right because the politicization of women’s pants is an American tradition. Critiques of women’s fashion have often served as thinly veiled attacks on women themselves, and wearing pants — in the West, reserved for men from the late Middle Ages until just recently — is a convenient metaphor for appropriating historically masculine privileges, from voting to running for president.

In the 19th century, early suffragists like Susan B. Anthony, Amelia Bloomer and Elizabeth Cady Stanton experimented with wearing voluminous pants — also known as “the freedom dress” — but suffered so much mockery that they ultimately rejected them as unhelpful distractions from their cause. The 19th Amendment actually preceded women’s right to wear trousers in public, which was granted by the U.S. attorney general on May 29, 1923.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST

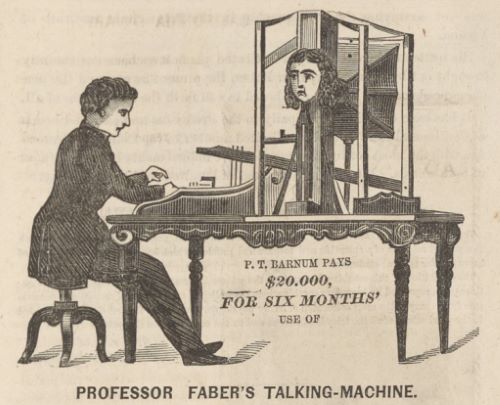

Mr. and Mrs. Talking Machine

The Euphonia, the Phonograph, and the Gendering of Nineteenth Century Mechanical Speech

In the early 1870s a talking machine, contrived by the aptly-named Joseph Faber appeared before audiences in the United States. Dubbed the “euphonia” by its inventor, it did not merely record the spoken word and then reproduce it, but actually synthesized speech mechanically. It featured a fantastically complex pneumatic system in which air was pushed by a bellows through a replica of the human speech apparatus, which included a mouth cavity, tongue, palate, jaw and cheeks. To control the machine’s articulation, all of these components were hooked up to a keyboard with seventeen keys— sixteen for various phonemes and one to control the Euphonia’s artificial glottis. Interestingly, the machine’s handler had taken one more step in readying it for the stage, affixing to its front a mannequin. Its audiences in the 1870s found themselves in front of a machine disguised to look like a white European woman.

By the end of the decade, however, audiences in the United States and beyond crowded into auditoriums, churches and clubhouses to hear another kind of “talking machine” altogether. In late 1877 Thomas Edison announced his invention of the phonograph, a device capable of capturing the spoken words of subjects and then reproducing them at a later time. The next year the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company sent dozens of exhibitors out from their headquarters in New York to edify and amuse audiences with the new invention. Like Faber before them, the company and its exhibitors anthropomorphized their talking machines, and, while never giving their phonographs hair, clothing or faces, they did forge a remarkably concrete and unanimous understanding of “who” the phonograph was. It was “Mr. Phonograph.”

Why had the Euphonia become female and the phonograph male? In this post, I peel apart some of the entanglements of gender and speech that operated in the Faber Euphonia and the phonograph, paying particular attention to the technological and material circumstances of those entanglements. What I argue is that the materiality of these technologies must itself be taken into account in deciphering the gendered logics brought to bear on the problem of mechanical speech. Put another way, when Faber and Edison mechanically configured their talking machines, they also engineered their uses and their apparent relationships with users. By prescribing the types of relationships the machine would enact with users, they constructed its “ideal” gender in ways that also drew on and reinforced existing assumptions about race and class.

Of course, users could and did adapt talking machines to their own ends. They tinkered with its construction or simply disregarded manufacturers’ prescriptions. The physical design of talking machines as well as the weight of social-sanction threw up non-negligible obstacles to subversive tinkerers and imaginers.

Born in Freiburg, Germany around 1800, Joseph Faber worked as an astronomer at the Vienna Observatory until an infection damaged his eyesight. Forced to find other work, he settled on the unlikely occupation of “tinkerer” and sometime in the 1820s began his quest for perfected mechanical speech. The work was long and arduous, but by no later than 1843 Faber was exhibiting his talking machine on the continent. In 1844 he left Europe to exhibit it in the United States, but in 1846 headed back across the Atlantic for a run at London’s Egyptian Hall.

That Faber conceived of his invention in gendered terms from the outset is reflected in his name for it—“Euphonia”—a designation meaning “pleasant sounding” and whose Latin suffix conspicuously signals a female identity. Interestingly, however, the inventor had not originally designed the machine to look like a woman but, rather, as an exoticized male “Turk.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT SOUNDING OUT!

Diners, Dudes, and Diets

How gender and power collide in food media and culture.

It took me six months to dream up the title Diners, Dudes, and Diets (University of North Carolina Press, 2020). For anyone who’s ever watched Guy Fieri’s show Diners, Drive-Ins and Dives, my inspiration is likely pretty clear. As I researched gender and power in contemporary American food media, I spent years analyzing Fieri’s polarizing persona (and watching dozens upon dozens of episodes of his shows), but I’d been thinking about what and why we eat for much longer.

I wrote my undergraduate thesis on the language of the weight loss industry and how it crafts a dieting theology based on “guilt-free” and “sinfully delicious” eating. Although I loved that research and writing, my younger self worried that such bookish activities were not enough to make a difference in the world, so I went to graduate school to study public health nutrition. I was convinced that fresh fruits and vegetables could fix everything, or at least put a dent in “diet-related diseases.” I’m now less interested in how food directly affects our health (though it does) or how it might change the world (though it can). I’m more invested in understanding why we believe this, why we continue to find in food such profound power, and why food remains such an anxious arena within our consumer culture and popular media.

In Diners, Dudes, and Diets, I focus on a particular kind of anxiety about our identities, which marketers call “gender contamination.” Marketing scholar Jill Avery explains this concept as “consumer resistance to brand gender-bending”—that is, how consumers react, sometimes quite negatively, when a brand’s perceived gender changes.1 In her study, Avery researched men’s reactionary, hyper-masculine responses when the Porsche Cayenne SUV became popular among women drivers, since these men considered Porsche a masculine brand—heck, one of the poster children for male midlife crisis! This idea of gender contamination can work in multiple directions. For example, a woman drinking a brand of whiskey marketed to men can create perceptions of empowerment. But for male consumers, sipping a diet soda marketed to women can lead to a perception of social stigma because the brand is feminized.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NURSING CLIO

Boys in Dresses: The Tradition

It’s difficult to read the gender of children in many old photos. That’s because coding American children via clothing didn’t begin until the 1920s.

Exploring the biographies of men as disparate as Tsar Nicholas II (b. 1868), Franklin Delano Roosevelt (b. 1882), and Ernest Hemingway (b. 1899), you’re apt to come across pictures of them as young boys looking indistinguishable from young girls. Their hair is long and they’re wearing dresses.

Scholar Jo B. Paoletti examines the changing fashions in children’s wear at the turn of the twentieth century, as a long tradition transitioned to more overtly gender-coded clothing. As she notes,

Until World War I, little boys were dressed in skirts and had long hair. Sexual “color coding” in the form of pink or blue clothing for infants was not common in this country [the US] until the 1920s; before that time male and female infants were dressed in identical white dresses.

Paoletti writes that young children’s clothing became more “sex-typed” as “adult women’s clothing was beginning to look more androgynous.” Before that transition, clothing styles for children followed a predictable progression.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JSTOR DAILY

Fear of the “Pussification” of America

On Cold War men’s adventure magazines and the antifeminist tradition in American popular culture.

Of all the responses to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States—ranging from debates over mask wearing to school closings— perhaps the most bizarre is the suggestion that this deadly disease can be avoided simply through manliness.

Nowhere was this made more explicit than when former US Navy Seal Robert O’Neill shared a photo of himself, unmasked, on a Delta Airlines flight. “I’m not a pussy,” declared O’Neill on Twitter, as if to suggest that potent, masculine men, like those on Seal Team 6, would not be cowed into wearing cowardly protective gear (Never mind that a passenger sitting one row behind O’Neill, in a US Marine Corps baseball cap, was wearing his mask).

O’Neill’s use of the “P-word” was far from an outlier; in fact, it has been employed near and far in recent months. Adam Corolla stoked public outcry only weeks later when he maintained, incorrectly, that only the “old or sick or both” were dying from the virus. “How many of you pussy’s [sic] got played?” the comedian asked.

Nor were these remarks limited to COVID-19. Not to be outdone by such repugnant rhetoric, President Donald Trump—who elevated the word during the 2016 presidential campaign for other reasons—reportedly lambasted senior military leaders, declaring that “my fucking generals are a bunch of pussies.” On the opposite end of the military chain of command, 2nd Lt. Nathan Freihofer, a young celebrity on TikTok, recently gained notoriety for anti-Semitic remarks on the social media platform. “If you get offended,” the young officer proclaimed, “get the fuck out, because it’s a joke…. Don’t be a pussy.”

What should we make of these men, young and old, employing the word as a way to shame potential detractors? Perhaps the most telling, and least surprising, explanation is that sexism and misogyny are alive and well in Trump’s America. Yet it would be mistaken to argue that the epithet has regained popularity simply because the president seemingly is so fond of the word. Rather, such language—and more importantly, what it insinuates—is far from new.

In July, after Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) was verbally accosted on the Capitol steps by fellow representative Ted Yoho (R-FL), the congresswoman delivered a powerful speech on the House floor. The problem with Yoho’s comments, Ocasio-Cortez argued, was not only that they were vile, but that they were part of a larger pattern of behavior toward women. “This is not new, and that is the problem,” she affirmed. “It is cultural. It is a culture of lack of impunity, of accepting of violence and violent language against women, and an entire structure of power that supports that.”

She’s right. This “violent” language—calling women “bitches” and men “pussies”—and the understandings that accompany it has a long history in American popular culture. And few cultural artifacts depict such sexist notions more overtly than Cold War men’s adventure magazines.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT HISTORY NEWS NETWORK

Frances Clayton and the Women Soldiers of the Civil War

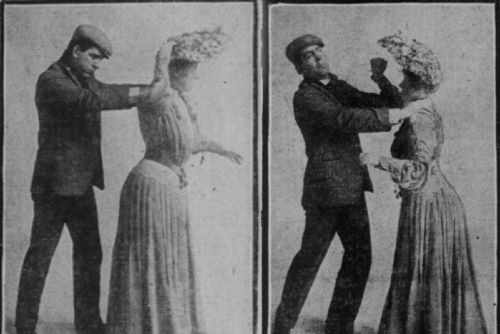

Notions of women during the Civil War center on self-sacrificing nurses, romantic spies, or the home front. However, women charged into battle, too.

Popular notions of women during the Civil War center on self-sacrificing nurses, romantic spies, or brave ladies maintaining the home front in the absence of their men. This conventional picture of gender roles does not tell the entire story, however. Men were not the only ones to march off to war. Women bore arms and charged into battle, too.

DeAnne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook, They Fought Like Demons, p. 1.

Minnesotan Frances Louisa Clayton (sometimes spelled Clalin; born ca. 1830) was purported to have disguised herself as a man under the alias Jack Williams in order to enlist and fight in the United States army during the Civil War, at a time when women were barred from service. Some historians question the veracity of accounts of Clayton’s military service. However, her story would not have been as rare an occurrence as one might think. In They Fought Like Demons (2002), historians DeAnne Blanton and Lauren M. Cook note they had discovered evidence of some 250 women soldiers who adopted male personas in order to fight in the Civil War. Moreover, Blanton and Cook expect there are hundreds more women whose stories have gone undocumented as lower literacy rates as well as the private nature of their soldierly subterfuge meant they were less likely to write letters or diaries detailing their experiences than their male counterparts. “Unless women were discovered as such … or unless they publicly confessed or privately told their tale of wartime service, the record of their military career is lost to us today.” As the authors acknowledge, Black women, in particular, are underrepresented in this history due to the fact that biographical stories of Black soldiers serving in the United States Colored Troops largely went uncovered by the mid-nineteenth century’s racist and white-centered mass media. What is certain, however, is that “more women took to the field during [the Civil War] than in any previous military affair [in the United States’ history].”

What we know of Clayton comes from newspaper reports and men’s eyewitness accounts. Interviews with Clayton and witnesses featured in many newspapers when her story broke in 1863. One witness’s account lauds her service: “She stood guard, went on picket duty, in rain or storm, and fought on the field with the rest and was considered a good fighting man.” However, only sparse details about Clayton’s military service are documented as “most reporters found the story of the faithful wife more appealing than the details of Clayton’s life as a soldier.” Reports say she enlisted alongside her husband, John, in a U.S. Missouri regiment in the fall of 1861. She fought in eighteen battles between 1861 and 1863. These included the Battle of Fort Donelson in Tennessee (February 11–16, 1862), in which she was wounded. During the Battle of Stones River (December 31, 1862–January 2, 1863), Clayton reported having witnessed her husband’s death “just a few feet in front of her. When the call came to fix bayonets, [she] stepped over his body and charged.” Clayton was discharged in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1863.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA LIBRARY

Manly Firmness: It’s Not Just for the 18th Century (Unfortunately)

The history of presidential campaigns shows the extent to which the language of politics remains gendered.

The references to “manly firmness” are everywhere in late-18th-century political sources. For example, Edward Dilly wrote to John Adams from London in 1775 to praise the men in the Continental Congress, “for the Wisdom of their Proceedings — their Unanimity, and Manly firmness.” In the Declaration of Independence, Thomas Jefferson listed the crimes of the King against the North American colonists. He pointed a finger at George III for dissolving representative governments in the colonies because those governments had opposed “with manly firmness” the King’s “invasions on the rights of the people.” After the war, as James Madison and Alexander Hamilton pushed for a more centralized form of government, they used the adjective “manly” in three of the numbers of the Federalist Papers. In Number 14, Madison crafted a version of the American Revolution in which colonists had “not suffered a blind veneration for antiquity, for custom, or for names,” and praised “this manly spirit,” to which “posterity will be indebted.”

None of this is news for anyone who has studied the United States’ founding era for the last four decades. In 1980, Linda Kerber told us in the very first page of the very first chapter of Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America that the “use of man” by Enlightenment writers “was, in fact, literal, not generic.”1 It’s not that these writers and thinkers completely ignored women and women’s roles, but rather they did not challenge the roles of women in society in the same ways that they challenged their ideas about taxation, monarchy, male citizenship, and other formerly-accepted constructions in the world around them.

In the founding era, both male and female writers had acknowledged that women could understand politics, but when these same writers approached the idea of a woman’s formal political participation, they tended to do so in a mocking and dismissive manner. Decades of college students have now studied Abigail Adams’s 1776 plea to her husband that Continental Congress should “Remember the Ladies” as they created a “new Code of Laws.” These students have also read John Adams’s maddening response, calling his wife “saucy,” and proclaiming, “We know better than to repeal our Masculine systems.”

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT NURSING CLIO

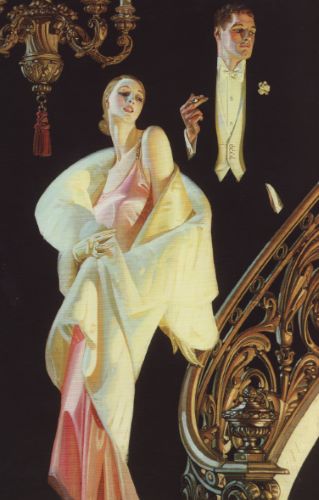

What Maketh a Man

How queer artist J.C. Leyendecker invented an iconography of twentieth-century American masculinity.

He stands on a staircase behind his paramour. His hand, hovering in the void where tuxedo blends with room, holds a cigarette as though at any moment he might toss it like a pair of cards into the muck. His bowtie is exquisitely knotted, collar stiff and starched, boutonniere like a white heart newly blossomed on his breast, everything tailored to perfection. He has a strong jaw and a dimpled chin. He looks off into the distance, away from you and away from his lover, too, alluringly unattached. His eyes are lowered, melancholic but without a trace of self-pity.

Or: He teeters precariously—one foot on the ground, the other extended in front of him, mid-punt. His hands act as counterweights, balancing him amid the movement. His football pants are baggy at the knees and the hips. His blue shirt’s brown shoulder pads turn his toned if unexceptional shoulders almost Herculean. His eyes remain on the football that he’s just sent sailing through the air. There’s not a hair on his head that’s out of place, despite the movement. His cheeks are rosy—out of red-blooded exertion rather than jejune innocence—yet the whole affair feels unlabored, amusing, fun. The corner of his mouth curls up slightly into an almost grin. He hopes he has just impressed his high school sweetheart, who must be sitting in the stands with her parents. A sea of white crosshatched brushstrokes form a textured abstract backdrop.

Or: He stands upright, in profile, the posture of an educated Jesuit. His military uniform is tan, recently laundered. A satchel hangs off his shoulder, resting at the base of his buttocks. His head is strapped into a Brodie helmet. That brown leather strap is flush to his cheeks and chin, contorting his face uncomfortably. He tries to show no emotion as an older man pins a medal to his breast, but his eyes betray both a sense of pride and a measure of sadness. Yet another honor his fallen brethren will not receive.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LAPHAM’S QUARTERLY

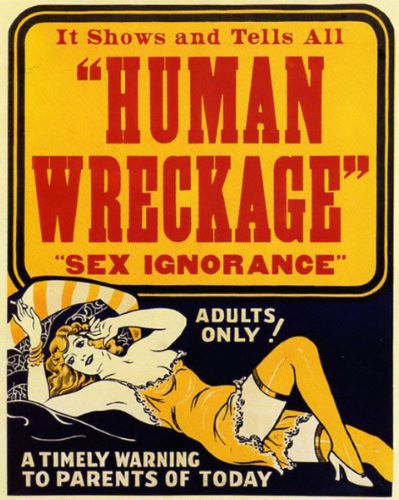

Slut-Shaming, Eugenics, and Donald Duck

The scandalous history of sex-ed movies.

After excusing herself from the dinner table, the 13-year-old girl begins to shout, her excited voice ringing through her family’s Mid-Century Modern home, “I got it! I got it!!” Her mother, in a Donna Reed-type dress, beams, while her 10-year-old brother looks up quizzically and asks, “Got what?” The boy’s father turns to him and says, brusquely, “She got her period, son!”

I saw this film in a middle-school sex-education class in 1988, and even though I’d read, “Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret,” the movie seemed embarrassingly old and this scene particularly laughable. How uncool did you have to be to announce the arrival of your period to the whole house? Is it really something you want your dad and brother discussing over potatoes? After all, our school felt girls had to be separated from the boys in our class just to watch this movie.

Today, most American adults can call up some memory of sex ed in their school, whether it was watching corny menstruation movies or seeing their school nurse demonstrate putting a condom on a banana. The movies, in particular, tend to stick in our minds. Screening films at school to teach kids how babies are made has always been a touchy issue, particularly for people who fear such knowledge will steer their children toward sexual behavior. But sex education actually has its roots in moralizing: American sex-ed films emerged from concerns that social morals and the family structure were breaking down.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT COLLECTORS WEEKLY

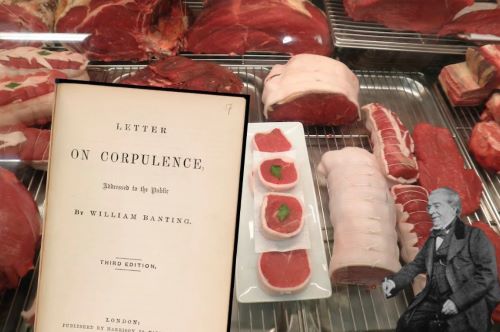

When Dieting Was Only For Men

Today, we tend to assume dieting is for women, but in the 1860s, it was a masculine pursuit.

It’s New Year’s resolution season, which means it’s time for many of us to try once again to stick to a diet. Today, we tend to assume dieting is mostly for women, but Katharina Vester explains that when Americans first started following diets in the 1860s, it was a masculine pursuit.

The notion of dieting hit the American shores as a British import in the mid-nineteenth century. This was an era of new individualism, when the idealized middle-class man rose through society by virtue of ambition and self-control. Reverend Sylvester Graham, inventor of the graham cracker, was already promoting an austere diet as a way to curb sexual impulses. Now, with more men working in sedentary professional jobs, many worried that their bodies were becoming soft and feminine. Men began looking to lose some weight.

In 1863, a British undertaker named William Banting published a diet book, A Letter on Corpulence, that quickly became popular in the United States. Banting’s Atkins-esque plan called for limiting starchy foods and sweets while consuming plenty of meat and liquor, a diet with a distinctly masculine slant. He also emphasized that the plan was rational and scientifically grounded and did not call for self-denial or sacrifice, which were understood as feminine attitudes in Victorian culture.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT JSTOR DAILY

Feminism in the Dock

Can (and should) conservatives reclaim feminism from the radicals?

I am often asked by young women if we should take back the term “feminism.” It still carries the cachet of caring about women, and most of us are quite happy with the achievements of first-wave feminism: equality before the law, voting rights, and property rights. But feminism in its current form is a radical devolution: divorcing sex from gender, vilifying all masculinity as toxic, and warring against nature and the family. How do we take back a feminism that has become so distorted? And do we want to? It’s worth considering some of the reasons feminism resonated with women, to identify questions that remain unanswered, and challenges women will potentially always face.

The debate over taking back feminism is complicated by the fact that no cohesive and consistent definition of feminism exists. It seems the only thing that unites feminists is that they care about issues that are related, and sometimes only tangentially related, to women. Underlying that are strong disagreements about what is good for women and human beings and what encompasses a life well lived. Feminists can’t even agree on what defines “women.” For example, trans-exclusionary feminists rebel against the encroachment of trans women into female sports and spaces, while other feminists do not—at least publicly—voice such objections.

Often, feminism is discussed as coming in three or more waves. First-wave feminists wanted to be treated as equal citizens, a project that culminated with the passing of the 19th Amendment, guaranteeing women the right to vote. Second-wave feminism of the mid-twentieth century focused on eliminating discrimination in the workplace and expanding educational opportunities. The movement soon allied itself with abortion advocates, connecting it to a Sexual Revolution ethos that saw marriage and family primarily as impediments to women’s personal goals and ambitions. Third and subsequent waves of feminism are even more difficult to describe and delineate, as factions within the movement have grown leaving no clear breaks from one wave to the next. The element that labeled gender a social construct has taken off and advocated for positions with radical implications, including transgender ideology.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT LAW & LIBERTY

The Huckster Ads of Early “Popular Mechanics”

Weird, revealing, and incredibly fun to read.

When I’m bored and worried about falling into a Twitter hole, there’s one thing that can always divert my attention.

Going over to the Internet Archive and perusing the incredibly weird ads of early-20th-century Popular Mechanics.

What, you haven’t already discovered this yourself?

You’re in for a treat. Popular Mechanics was a curious beast back in those days. Like the name suggests, it included tons of stories about inventors around the world, and stuff they were getting up to. So in the April 1920 issue, for example, you had articles like these …

George Washington Would Have So Worn a Mask

The father of the country was a team player who had no interest in displays of hyper-masculinity.

The genre “What would X do?” – where X stands for a noted figure in history, say Jesus or Dolly Parton – is silly. And yet, as a scholar writing a new biography of George Washington, I can’t help making a bold declaration: The Father of this country would wear his mask in public.