Although much of ancient Roman life revolved around business, there was also time available for leisure.

By Dr. Harold Whetstone Johnston

Late Professor of Latin

Indiana University

Introduction

After the games of childhood were passed the Roman seemed to lose all instinct for play. Of sport for sport’s sake he knew nothing, he took part in no games for the sake of excelling in them. He played ball before his dinner for the good of the exercise, he practiced riding, fencing, wrestling, hurling the discus, and swimming for the strength and skill they gave him in arms, he played a few games of chance for the excitement the stakes afforded, but there was no “national game” for the young men, and there were no social amusements in which men and women took part together.

The Roman made it hard and expensive, too, for others to amuse him. He cared nothing for the drama, little for spectacular shows, more for farces and variety performances, perhaps, but the one thing that really appealed to him was excitement, and this he found in gambling or in such amusements only as involved the risk of injury to life and limb, the sports of the circus and the amphitheater. We may describe first the games in which the Roman participated himself and then those at which he was a mere spectator. In the first class are field sports and games of hazard, in the second the public and private games (lūdī pūblicī et prīvātī).

Sports of the Campus Martius

Overview

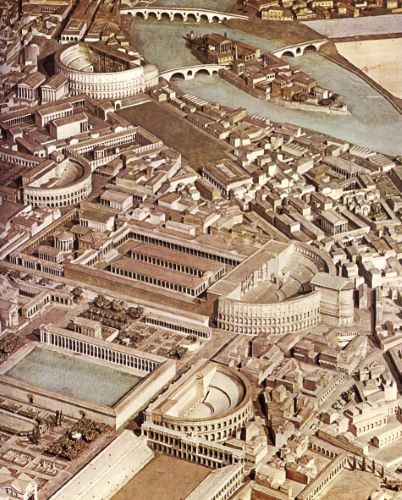

The Campus Martius included all the level ground lying between the Tiber and the Capitoline and Quirinal hills. The northwestern portion of this plain, bounded on two sides by the Tiber, which here sweeps abruptly to the west, kept clear of public and private buildings and often called simply the Campus, was for centuries the playground of Rome. Here the young men gathered to practice the athletic games mentioned above, naturally in the cooler parts of the day. Even men of graver years did not disdain a visit to the Campus after the merīdiātiō, in preparation for the bath before dinner, instead of which the younger men preferred to take a cool plunge in the convenient river.

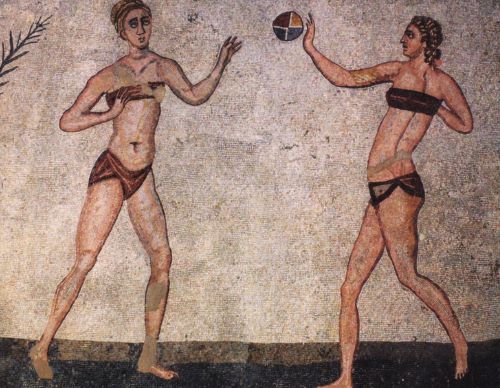

The sports themselves were those that we are accustomed to group together as track and field athletics. They ran foot races, jumped, threw the discus, practiced archery, and had wrestling and boxing matches. These sports were carried on then much as they are now, if we may judge by Vergil’s description in the Fifth Aeneid, but an exception must be made of the games of ball. These seem to have been very dull and stupid as compared with ours. It must be remembered, however, that they were played more for the healthful exercise they furnished than for the joy of the playing, and by men of high position, too—Caesar, Maecenas, and even the Emperor Augustus.

Ball Games

Balls of different sizes are known to have been used in the different games, variously filled with hair, feathers, and air (follēs). Throwing and catching formed the basis of all the games, the bat being practically unknown. In the simplest game the player threw the ball as high as he could, and tried to catch it before it struck the ground. Variations of this were what we should call juggling, the player keeping two or more balls in the air, and throwing and catching by turns with another player. Another game must have resembled our handball, requiring a wall and smooth ground at its foot. The ball was struck with the open hand against the wall, allowed to fall back upon the ground and bound, and then struck back against the wall in the same manner. The aim of the player was to keep the ball going in this way longer than his opponent could. Private houses and the public baths often had “courts” especially prepared for this amusement.

A third game was called trigōn, and was played by three persons, stationed at the angles of an equilateral triangle. Two balls were used and the aim of the player was to throw the ball in his possession at the one of his opponents who would be the less likely to catch it. As two might throw at the third at the same moment, or as the thrower of one ball might have to receive the second ball at the very moment of throwing, both hands had to be used and a good degree of skill was necessary. Other games, all of throwing and catching, are mentioned here and there, but none is described with sufficient detail to be clearly understood.

Games of Chance

Overview

The Romans were passionately fond of games of chance, and gambling was so universally associated with such games that they were forbidden by law, even when no stakes were actually played for. A general indulgence seems to have been granted at the Saturnalia in December, and public opinion allowed old men to play at any time. The laws were hard to enforce, however, as such laws usually are, and large sums were won and lost not merely at general gambling resorts, but also at private houses.

Games of chance, in fact, with high stakes, were one of the greatest attractions at the men’s dinners that have been mentioned. The commonest form of gambling was our “heads or tails,” coins being used as with us, the value depending on the means of the players. Another common form was our “odd or even,” each player guessing in turn and in turn holding counters concealed in his outstretched hand for his opponent to guess. The stake was usually the contents of the hand though side bets were not unusual. In a variation of this game the players tried to guess the actual number of the counters held in the hand. Of more interest, however, were the games of knuckle-bones and dice.

Knuckle-bones

Knuckle-bones (tālī) of sheep and goats, and imitations of them in ivory, bronze, and stone, were used as playthings by children and for gaming by men. Children played our “jackstones” with them, throwing five into the air at once and catching as many as possible on the back of the hand. The length of the tālī was greater than their width and they had, therefore, four long sides and two ends. The ends were rounded off or pointed, so that the tālī could not stand on them. Of the four long sides two were broader than the others. Of the two broader sides one was concave, the other convex; while of the narrower sides one was flat and the other indented. As all the sides were of different shapes the tālī did not require marking as do our dice, but for convenience they were sometimes marked with the numbers 1, 3, 4, and 6, the numbers 2 and 5 being omitted. Four tālī were used at a time, either thrown into the air with the hand or thrown from a dice-box (fritillus), and the side on which the bone rested was counted, not that which came up. Thirty-five different throws were possible, of which each had a different name. Four aces were the lowest throw, called the Vulture, while the highest, called the Venus, was when all the tālī came up differently. It was this throw that designated the magister bibendī.

Dice

The Romans had also dice (tesserae) precisely like our own. They were made of ivory, stone, or some close-grained wood, and had the sides numbered from one to six. Three were used at a time, thrown from the fritillus, as were the knuckle-bones, but the sides counted that came up. The highest throw was three sixes, the lowest three aces. In ordinary gaming the aim of the player seems to have been to throw a higher number than his opponent, but there were also games played with dice on boards with counters, that must have been something like our backgammon, uniting skill with chance.

Little more of these is known than their names. If one considers how much space is given in our newspapers to the game of baseball, and how impossible it would be for a person who had never seen a game to get a correct idea of one from the newspaper descriptions only, it will not seem strange that we know so little of Roman games.

Public and Private Games

With the historical development of the Public Games this book has no concern. It is sufficient to say that these free exhibitions, given first in honor of some god or gods at the cost of the state and extended and multiplied for political purposes until all religious significance was lost, had come by the end of the Republic to be the chief pleasure in life for the lower classes in Rome, so that Juvenal declares that the free bread and the games of the circus were the people’s sole desire. Not only were these games free, but when they were given all public business was stopped and all citizens were forced to take a holiday.

These holidays became rapidly more and more numerous; by the end of the Republic sixty-six days were taken up by the games, and in the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161-180) no less than one hundred and thirty-five days out of the year were thus closed to business. Besides these standing games, others were often given for extraordinary events, and funeral games were common when great men died. These last were not made legal holidays. For our purposes the distinction between public and private games is not important, and all may be classified according to the nature of the exhibitions as, lūdī scēnicī, dramatic entertainments given in a theater, lūdī circēnsēs, chariot races and other exhibitions given in a circus, and mūnera gladiātōria, shows of gladiators usually given in an amphitheater.

Dramatic Performances

Overview

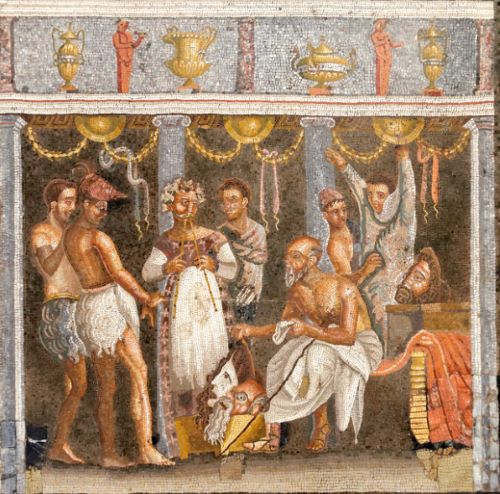

The history of the development of the drama at Rome belongs, of course, to the history of Latin literature. In classical times dramatic performances consisted of comedies (cōmoediae), tragedies (tragoediae), farces (mīmī), and pantomimes (pantomīmī). The farces and pantomimes were used chiefly as interludes and afterpieces, though with the common people they were the most popular of all and outlived the others. Tragedy never had any real hold at Rome, and only the liveliest comedies gained favor on the stage. Of the comedies the only ones that have come down to us are those of Plautus and Terence, all adaptations from Greek originals, all depicting Greek life, and represented in Greek costumes (fābulae palliātae).

They were a good deal more like our comic operas than our comedies, large parts being recited to the accompaniment of music and other parts sung while the actor danced. They were always presented in the daytime, as Roman theaters were provided with no means of lighting, in the early period after the noon meal, but by Cicero’s time they had come to be given in the morning. The average comedy must have required about two hours for the acting, with allowance for the occasional music between the scenes. We read of a play being acted twice in a day, but this must have been very exceptional, as time had to be allowed for the other more popular shows given on the same occasion.

Staging the Play

The play, as well as the other sports, was under the supervision of the officials in charge of the games at which it was given. They contracted for the production of the play with some recognized manager (dominus gregis), who was usually an actor of acknowledged ability and had associated with him a troupe (grex) of others only inferior to himself. The actors were all slaves, and men took the parts of women. There was no limit fixed to the number of actors, but motives of economy would lead the dominus to produce each play with the smallest number possible, and two or even more parts were often assigned to one actor.

The characters in the comedies wore the ordinary Greek dress of daily life and the costumes were, therefore, not expensive. The only make-up required was paint for the face, especially for the actors who took women’s parts, and the wigs that were used conventionally to represent different characters, gray for old men, black for young men, red for slaves, etc. These and the few properties (ōrnāmenta) necessary were furnished by the dominus. It seems to have been customary also for him to feast the actors at his expense if their efforts to entertain were unusually successful.

The Early Theater

The theater itself deserved no such name until very late in the Republic. During the period when the best plays were being written (200-160 B.C.) almost nothing was done for the accommodation of the actors or the audience. The stage was merely a temporary platform, rather wide than deep, built at the foot of a hill or a grass-covered slope. There were almost none of the things that we are accustomed to associate with a stage, no curtains, no flies, no scenery that could be changed, not even a sounding-board to aid the actor’s voice. There was no way either to represent the interior of a house, and the dramatist was limited, therefore, to such situations as might be supposed to take place upon a public street. This street the stage represented; at the back of it were shown the fronts of two or three houses with windows and doors that could be opened, and sometimes there was an alley or passageway between two of the houses. An altar stood on the stage, we are told, to remind the people of the religious origin of the games.

No better provision was made for the audience than for the actors. The people took their places on the slope before the stage, some reclining on the grass, some standing, some perhaps sitting on stools they had brought from home. There was always din and confusion to try the actor’s voice, pushing and crowding, disputing and quarreling, wailing of children, and in the very midst of the play the report of something livelier to be seen elsewhere might draw the whole audience away.

The Later Theater

Beginning about 145 B.C., however, efforts were made to improve upon this poor apology for a theater, in spite of the opposition of those who considered the plays ruinous to morals. In that year a wooden theater on Greek lines provided with seats was erected, but the senate caused it to be pulled down as soon as the games were over. It became a fixed custom, however, for such a temporary theater with special and separate seats for senators, and much later for the knights, to be erected as often as plays were given at public games, until in 55 B.C. Pompeius Magnus erected the first permanent theater at Rome. It was built of stone after the plans of one he had seen at Mytilene and seated at least seventeen thousand people; Pliny says forty thousand. This theater showed two noteworthy divergences from its Greek model. The Greek theaters were excavated out of the side of the hill, while the Roman theater was erected on level ground (that of Pompeius in the Campus Martius) and gave, therefore, a better opportunity for exterior magnificence. The Greek theater had a large circular space for choral performances immediately before the stage; in the Roman theater this space, called the orchestra then as now, was much smaller, and was assigned to the senators. The first fourteen rows of seats rising immediately behind them were reserved for the knights. The seats back of these were occupied indiscriminately by the people, on the principle apparently of first come first served. No other permanent theaters were erected at Rome until 13 B.C., when two were constructed. The smaller had room for eleven thousand spectators, the larger, erected in honor of Marcellus, the nephew of Augustus, for twenty thousand. These improved playhouses made possible spectacular elements in the performances that the rude scaffolding of early days had not permitted, and these spectacles proved the ruin of the legitimate drama. To make realistic the scenes representing the pillaging of a city, Pompeius is said to have furnished troops of cavalry and bodies of infantry, hundreds of mules laden with real spoils of war, and three thousand mixing bowls. In comparison with these three thousand mixing bowls, the avalanches, runaway locomotives, sawmills in full operation, and cathedral scenes of modern times seem poor indeed.

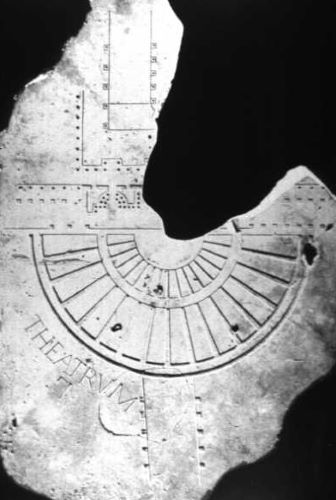

The general appearance of these theaters, the type of hundreds erected later throughout the Roman world, was like the plan of a theater on lines laid down by Vitruvius. GH is the front line of the stage (proscaenium); all behind it is the scaena, devoted to the actors, all before it is the cavea, devoted to the spectators. IKL in the rear mark the position of three doors, for example, those of the three houses mentioned above. The semicircular orchestra CMD is the part appropriated to the senators. The seats behind the orchestra, rising in concentric semicircles, are divided by five passageways into six portions (cuneī), and in a similar way the seats above the semicircular passage (praecīnctiō) shown in the figure are divided by eleven passageways into twelve cuneī. Access to the seats of the senators was afforded by passageways under the higher seats at the right and the left of the stage, one of which may be seen in Fig. 135, which represents a part of the smaller of the two theaters uncovered at Pompeii, built not far from 80 B.C. Over the vaulted passage will be noticed what must have been the best seats in the theater, corresponding in some degree to the boxes of modern times. These were reserved for the emperor, if he was present, for the officials who superintended the games and (on the other side) for the Vestals. Access to the higher seats was conveniently given by broad stairways constructed under the seats and running up to the passageways between the cuneī. Behind the highest seats were broad colonnades, affording shelter in case of rain, and above them were tall masts from which awnings (vēla) were spread to protect the people from the sun. Consider the remains of a Roman theater still existing at Orange, in the south of France. It should be noticed that the stage was connected with the auditorium by the seats over the vaulted passages to the orchestra, and that the curtain was raised from the bottom, to hide the stage, not lowered from the top as ours is now. Vitruvius suggested that rooms and porticos be built behind the stage, like the colonnades that have been mentioned, to afford space for the actors and properties and shelter for the people in case of rain.

Roman Circuses

Overview

The games of the circus were the oldest of the free exhibitions at Rome and always the most popular. The word circus means simply a ring and the lūdī circēnsēs were therefore any shows that might be given in a ring. We shall see below that these shows were of several kinds, but the one most characteristic, the one that is always meant when no other is specifically named, is that of chariot races. For these races the first and really the only necessary condition is a large and level piece of ground. This was furnished by the valley between the Aventine and Palatine hills, and here in prehistoric times the first Roman race course was established. This remained the circus, the one always meant when no descriptive term was added, though when others were built it was called sometimes by way of distinction the Circus Maximus. None of the others ever approached it in size, in magnificence, or in popularity.

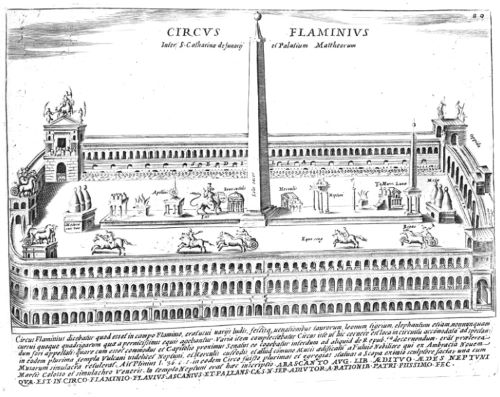

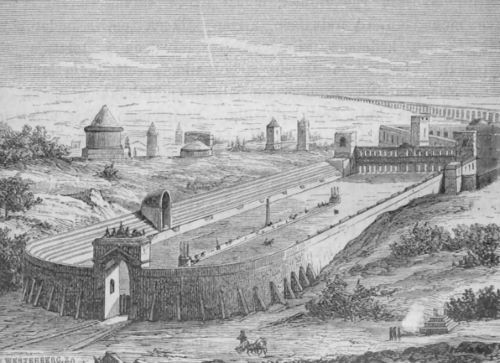

The second circus to be built at Rome was the circus Flāminius, founded in 221 B.C. by the same Caius Flaminius, who built the Flaminian road. It was located in the southern part of the Campus Martius, and like the Circus Maximus was exposed to the frequent overflows of the Tiber. Its position is fixed beyond question, but the actual remains are very scanty, so that little is known of its size or appearance. The third to be established was that of Caius (Caligula) and Nero, named from the two emperors who had to do with its construction, and erected, therefore, in the first century A.D. It lay at the foot of the Vatican hill, but we know little more of it than that it was the smallest of the three. These three were the only circuses within the city. In the immediate neighborhood, however, were three others. Five miles out on the via Portuēnsis was the circus of the Arval Brethren. About three miles out on the Appian way was the Circus of Maxentius, erected in 309 A.D. This is the best preserved of all, and a plan of it is shown in the next paragraph. On the same road, some twelve miles from the city, in the old town of Bovillae, was a third, making six within easy reach of the people of Rome.

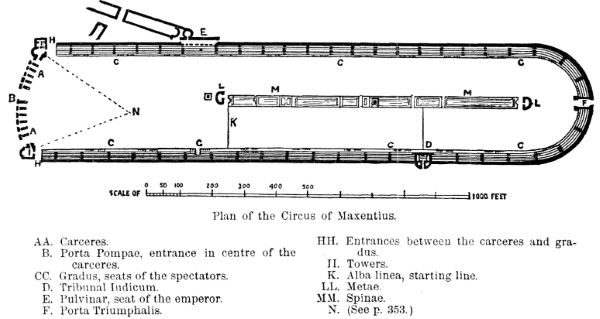

Plan of the Circus

All of the Roman circuses known to us had the same general arrangement, which will be readily understood from the plan of the Circus of Maxentius. The long and comparatively narrow stretch of ground which formed the race course proper (arēna) is almost surrounded by the tiers of seats, running in two long parallel lines uniting in a semicircle at one end. In the middle of this semicircle is a gate, marked F in the plan, by which the victor left the circus when the race was over. It was called, therefore, the porta triumphālis. Opposite this gate at the other end of the arena was the station for the chariots, called carcerēs, “barriers,” flanked by two towers at the corners, and divided into two equal sections by another gate, called the porta pompae, by which processions entered the circus. There are also gates between the towers and the seats. The exterior appearance of the towers and barriers were called together the oppidum.

The arena is divided for about two-thirds its length by a fence or wall, called the spīna, “backbone.” At the end of this were fixed pillars, called mētae, marking the inner line of the course. Once around the spīna was a lap (spatium, curriculum), and the fixed number of laps, usually seven to a race, was called a missus. The last lap, however, had but one turn, that at the mēta prīma, the one nearest the porta triumphālis, the finish being a straightaway dash to the calx. This was a chalk line drawn on the arena far enough away from the second mēta to keep it from being obliterated by the hoofs of the horses as they made the turn, and far enough also from the carcerēs to enable the driver to stop his team before dashing into them. The important things about the developed circus are the arēna, carcerēs, spīna, mētae, and the seats, all of which will be more particularly described.

The Arena

The arena is the level space surrounded by the seats and the barriers. The name was derived from the sand used to cover its surface to spare as much as possible the unshod feet of the horses. A glance at the plan will show that speed could not have been the important thing with the Romans that it is with us. The sand, the shortness of the stretches, and the sharp turns between them were all against great speed. The Roman found his excitement in the danger of the race. In every representation of the race course that has come down to us may be seen broken chariots, fallen horses, and drivers under wheels and hoofs. The distance was not a matter of close measurement either, but varied in the several circuses, the Circus Maximus being fully 300 feet longer than the Circus of Maxentius. All seem to have had constant, however, the number of laps, seven to the race, and this also goes to prove that the danger was the chief element in the popularity of the contests.

The distance actually traversed in the Circus of Maxentius may be very closely estimated. The length of the spīna is about 950 feet. If we allow fifty feet for the turn at each mēta, each lap makes a distance of 2,000 feet, and six laps, 12,000 feet. The seventh lap had but one turn in it, but the final stretch to the calx made it perhaps 300 feet longer than one of the others, say 2,300 feet. This gives a total of 14,300 feet for the whole missus, or about 2.7 miles. Jordan calculates the missus of the Circus Maximus at 8.4 kilometers, which would be about 5.2 miles, but he seems to have taken the whole length of the arena into account, instead of that merely of the spīna.

The Barriers

The carcerēs were the stations of the chariots and teams when ready for the races to begin. They were a series of vaulted chambers entirely separated from each other by solid walls, and closed behind by doors through which the chariots entered. The front of the chamber was formed by double doors, with the upper part made of grated bars, admitting the only light which it received. From this arrangement the name carcer was derived. Each chamber was large enough to hold a chariot with its team, and as a team was composed sometimes of as many as seven horses the “prison” must have been nearly square. There was always a separate chamber for each chariot. Up to the time of Domitian the highest number of chariots was eight, but after his time as many as twelve sometimes entered the same race, and twelve carcerēs had, therefore, to be provided, although four chariots was the usual number. Half of these chambers lay to the right, half to the left of the porta pompae.

The carcerēs were arranged in a curved line. This is supposed to have been drawn in such a way that every chariot, no matter which of the carcerēs it happened to occupy, would have the same distance to travel in order to reach the beginning of the course proper at the nearer end of the spīna. There was no advantage in position, therefore, at the start, and places were assigned by lot. In later times a starting line (līnea alba) was drawn with chalk between the second mēta and the seats to the right, but the line of carcerēs remained curved as of old. At the ends of the row of chambers, towers were built which seem to have been the stands for the musicians; over the porta pompae was the box of the chief official of the games (dator lūdōrum), and between his box and the towers were seats for his friends and persons connected with the games.

The Spina and Metae

The spīna divided the race course into two parts, making a minimum distance to be run. Its length was about two-thirds that of the arena, but it started only the width of the track from the porta triumphālis, leaving entirely free a much larger space at the end near the porta pompae. It was perfectly straight, but did not run precisely parallel to the rows of seats; at the end B the distance BC is somewhat greater than the distance AB, in order to allow more room at the starting line (līnea alba), where the chariots would be side by side, than further along the course, where they would be strung out. The mētae, so named from their shape, were pillars erected at the two ends of the spīna and architecturally a part of it, though there may have been a space between. In Republican times the spīna and the mētae must have been made of wood and movable, in order to give free space for the shows of wild beasts and the exhibitions of cavalry that were originally given in the circus. After the amphitheater was devised the circus came to be used for races exclusively and the spīna became permanent. It was built up, of most massive proportions, on foundations of indestructible concrete and was adorned with magnificent works of art that must have entirely concealed horses and chariots when they passed to the other side of the arena.

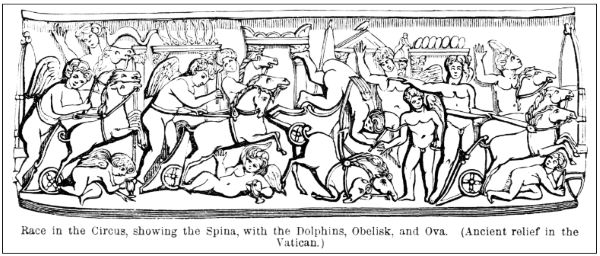

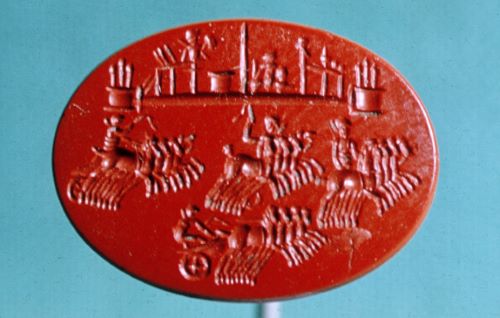

A representation of a circus has been preserved to us in a board-game of some sort found at Bovillae, which gives an excellent idea of the spīna. We know from various reliefs and mosaics that the spīna of the Circus Maximus was covered with a series of statues and ornamental structures, such as obelisks, small temples or shrines, columns surmounted by statues, altars, trophies, and fountains. Augustus was the first to erect an obelisk in the Circus Maximus; it was restored in 1589 A.D., and now stands in the Piazza del Popolo, measuring without the base about 78 feet in height. Constantius erected another in the same circus, which now stands before the Lateran church, measuring 105 feet. The obelisk of the Circus of Maxentius now stands in the Piazza Navona. Besides these purely ornamental features, every circus had at each end of its spīna a pedestal supporting seven large eggs (ōva) of marble, one of which was taken down at the end of each lap, in order that the people might know just how many remained to be run. Another and very different idea for the spīna is from a mosaic at Lyons. This is a canal filled with water, with an obelisk in the middle. The mētae in their developed form are shown very clearly in this mosaic, three conical pillars of stone set on a semicircular plinth, all of the most massive construction.

The Seats

The seats around the arena in the Circus Maximus were originally of wood, but accidents owing to decay and losses by fire had led by the time of the Empire to reconstruction in marble except perhaps in the very highest rows. The seats in the other circuses seem to have been from the first of stone. At the foot of the tiers of seats was a marble platform (podium) which ran along both sides and the curved end, coextensive therefore with them. On this podium were erected boxes for the use of the more important magistrates and officials of Rome, and here Augustus placed the seats of the senators and others of high rank. He also assigned seats throughout the whole cavea to various classes and organizations, separating the women from the men, though up to his time they had sat together. Between the podium and the track was a screen of open work, and when Caesar showed wild beasts in the circus he had a canal ten feet wide and ten feet deep dug next the podium and filled with water as an additional protection. Access to the seats was given from the rear, numerous broad stairways running up to the praecīnctiōnēs, of which there were probably three in the Circus Maximus. The horizontal spaces between the praecīnctiōnēs were called maeniāna, and each of these was in turn divided by stairways into cuneī, and the rows of seats in the cuneī were called gradūs. The sittings in the row do not seem to have been marked off any more than they are now in the “bleachers” at our baseball grounds. When sittings were reserved for a number of persons they were described as so many feet in such a row (gradus) of such a section (cuneus) of such a circle (maeniānum).

The number of sittings testifies to the popularity of the races. The little circus at Bovillae had seats for at least 8,000 people, according to Hülsen, that of Maxentius for about 23,000, while the Circus Maximus, accommodating 60,000 in the time of Augustus, was enlarged to a capacity of nearly 200,000 in the time of Constantius. The seats themselves were supported upon arches of massive masonry; an idea of their appearance from the outside may be had from the exterior view of the Coliseum. Every third of these vaulted chambers under the seats seems to have been used for a staircase, the others for shops and booths and in the upper parts for rooms for the employés of the circus, who must have been very numerous. Galleries seem to have crowned the seats, as in the theaters, and balconies for the emperors were built in conspicuous places, the ruins not enabling their positions to be fixed precisely. An idea of the appearance of the seats from within the arena may be had from an attempted reconstruction of the Circus Maximus, the details of which are quite uncertain.

Furnishing the Races

There must have been a time, of course, when the races in the circus were open to all who wished to show their horses or their skill in driving them, but by the end of the Republic no persons of repute took part in the games, and the teams and drivers were furnished by racing syndicates (factiōnēs), who practically controlled the market so far as concerned trained horses and trained men. With these syndicates the giver of the games contracted for the number of races that he wanted (ten or twelve a day in Caesar’s time, later twice the number, and even more on special occasions), and they furnished everything needed. These syndicates were named from the colors worn by their drivers. We hear at first of two only, the red (russāta) and the white (albāta); two more were added, the blue (veneta) in the time of Augustus probably, and the green (prasina) soon after, and finally Domitian added the purple and the gold.

The greatest rivalry existed between these organizations. They spent immense sums of money on their horses, importing them from Greece, Spain, and Mauritania, and even larger sums, perhaps, upon the drivers. They maintained training stables on as large a scale as any of which modern times can boast; a mosaic found in one of these establishments in Algeria names among the attendants jockeys, grooms, stable-boys, saddlers, doctors, trainers, coaches, and messengers, and shows the horses covered with blankets in their stalls. This rivalry spread throughout the city; each factiō had its partisans, and vast sums of money were lost and won as each missus was finished. All the tricks of the ring were skillfully practiced; horses were hocused, drivers hired from rival syndicates or bribed, and even poisoned, we are told, when they were proof against money.

The Teams

The chariot used in the races was low and light, closed in front, open behind, with long axles and low wheels to lessen the risk of turning over. The driver seems to have stood well forward in the car, there being no standing place behind the axle. The teams consisted of two horses (bīgae), three (trīgae), four (quadrīgae), and in later times six (sēiugēs) or even seven (septeiugēs), but the four-horse team was the most common and may be taken as the type. Two of the horses were yoked together, one on each side of the tongue, the others were attached to the car merely by traces. Of the four the horse to the extreme left was the most important, because the mēta lay always on the left and the highest skill of the driver was shown in turning it as closely as possible. The failure of the horse nearest it to respond promptly to the rein or the word might mean the wreck of the car (by going too close) or the loss of the inside track (by going too wide), and in either case the loss of the race. Inscriptions sometimes give the names of all the horses of the team, sometimes only the horse on the left is mentioned.

Before the races began lists of the horses and drivers in each were published for the guidance of those who wished to stake their money, and while no time was kept the records of horses and men were followed as eagerly as now. From the nature of the course it is evident that strength and courage and above all lasting qualities were as essential as speed. The horses were almost always stallions (mares are very rarely mentioned), and were never raced under five years of age. Considering the length of the course and the great risk of accidents it is surprising how long the horses lasted. It was not unusual for a horse to win a hundred races (such a horse was called centēnārius), and one Diocles, himself a famous driver, owned a horse that had won two hundred (ducēnārius).

The Drivers

The drivers (agitātōrēs, aurīgae) were slaves or freedmen, some of whom had won their freedom by their skill and daring in the course. Only in the most corrupt days of the Empire did citizens of any social position take actual part in the races. Especially to be noticed in the dress are the close fitting cap, the short tunic (always of the color of his factiō), laced around the body with leathern thongs, the straps of leather around the thighs, the shoulder pads, and the heavy leather protectors for the legs. Our football players wear like defensive armor. The reins were knotted together and passed around the driver’s body. In his belt he carried a knife to cut the reins in case he should be thrown from the car, or to cut the traces if a horse should fall and become entangled in them. The races gave as many opportunities then as now for skillful driving, and required even more of strength and daring.

What we should call “fouling” was encouraged. The driver might turn his team against another, might upset the car of a rival if he could; having gained the inside track he might drive out of the straight course to keep a swifter team from passing his. The rewards were proportionately great. The successful aurīga, despised though his station, was the pet and pride of the race-mad crowd, and under the Empire at least he was courted and fêted by high and low. The pay of successful drivers was extravagant, the rival syndicates bidding against each other for the services of the most popular. Rich presents, too, were given them when they won their races, not only by their factiōnēs, but also by outsiders who had backed them and profited by their skill.

Famous Aurigae

The names of some of these victors have come down to us in inscriptions erected in their honor or to their memory by their friends. Among these may be mentioned Publius Aelius Gutta Calpurnianus of the late Empire (1,127 victories), Caius Apuleius Diocles, a Spaniard (in twenty-four years 4,257 races, l,462 victories, winning the sum of 35,863,120 sesterces, about $1,800,000), Flavius Scorpus (2,048 victories at the age of twenty-seven), Marcus Aurelius Liber (3,000 victories), Pompeius Muscosus (3,559 victories). To these may be added Crescens, an inscription in honor of whom was found at Rome in 1878.

Other Shows of the Circus

The circus was used less frequently for other exhibitions than chariot races. Of these may be mentioned the performances of the dēsultōrēs, men who rode two horses and leaped from one to the other while going at full speed, and of trained horses who performed various tricks while standing on a sort of wheeled platform which gave a very unstable footing. There were also exhibitions of horsemanship by citizens of good standing, riding under leaders in squadrons, to show the evolutions of the cavalry. The lūdus Trōiae was also performed by young men of the nobility, a game that Vergil has described in the Fifth Aeneid. More to the taste of the crowd were the hunts (vēnātiōnēs), when wild beasts were turned loose in the circus to slaughter each other or be slaughtered by men trained for the purpose. We read of panthers, bears, bulls, lions, elephants, hippopotami, and even crocodiles (in artificial lakes made in the arena) exhibited during the Republic. In the circus, too, combats of gladiators sometimes took place, but these were more frequently in the amphitheater.

One of the most brilliant spectacles must have been the procession (pompa circēnsis) which formally opened some of the public games. It started from the capitol and wound its way down to the Circus Maximus, entering by the porta pompae, and passed entirely around the arena. At the head in a car rode the presiding magistrate, wearing the garb of a triumphant general and attended by a slave who held a wreath of gold over his head. Next came a crowd of notables on horseback and on foot, then the chariots and horsemen who were to take part in the games. Then followed priests, arranged by their colleges, and bearers of incense and of the instruments used in sacrifices, and statues of deities on low cars drawn by mules, horses, or elephants, or else carried on litters (fercula) on the shoulders of men. Bands of musicians headed each division of the procession, a feeble reminiscence of which is seen in the parade through the streets that precedes the performance of the modern circus.

Gladiatorial Combats

Overview

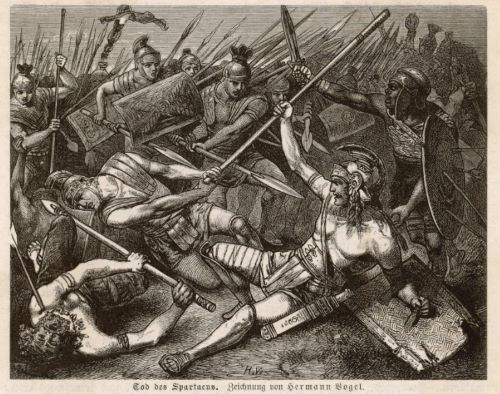

Gladiatorial combats seem to have been known in Italy long before the founding of Rome. We hear of them first in Campania and Etruria. In Campania the wealthy and dissolute nobles, we are told, made slaves fight to the death at their banquets and revels for the entertainment of their guests. In Etruria the combats go back in all probability to the offering of human sacrifices at the burial of distinguished men in accordance with the ancient belief that blood is acceptable to the dead. The victims were captives taken in war, and it became the custom gradually to give them a chance for their lives by supplying them with weapons and allowing them to fight each other at the grave, the victor being spared at least for the time. The Romans were slow to adopt the custom, the first exhibition being given in the year 264 B.C., almost five centuries after the founding of the city. That they derived it from Etruria rather than Campania is shown by the fact that the exhibitions were at funeral games, the earliest at those of Brutus Pera in 264 B.C., Marcus Aemilius Lepidus in 216 B.C., Marcus Valerius Lavinus in 200 B.C., and Publius Licinius in 183 B.C.

For the first one hundred years after their introduction the exhibitions were infrequent as the dates just given show, those mentioned being all of which we have any knowledge during the period, but after this time they were given more and more frequently and always on a larger scale. During the Republic, however, they remained in theory at least private games (mūnera), not public games (lūdī); that is, they were not celebrated on fixed days recurring annually, and the givers of the exhibitions had to find a pretext for them in the death of relatives or friends, and to defray the expenses from their own pockets. In fact we know of but one instance in which actual magistrates (the consuls Publius and Manlius, 105 B.C.) gave such exhibitions, and we know too little of the attendant circumstances to warrant us in assuming that they acted in their official capacity. Even under the Empire the gladiators did not fight on the days of the regular public games. Augustus, however, provided funds for “extraordinary shows” under the direction of the praetors. Under Domitian the aediles-elect were put in charge of these exhibitions which were given regularly in December, the only instance known of fixed dates for the mūnera gladiātōria. All others of which we read are to be considered the freewill offerings to the people of emperors, magistrates, or private citizens.

Popularity of the Combats

The Romans’ love of excitement made the exhibitions immediately and immensely popular. At the first exhibition mentioned above, that in honor of Brutus Pera, three pairs of gladiators only were shown, but in the three that followed the number of pairs rose in order to twenty-two, twenty-five, and sixty. By the time of Sulla politicians had found in the mūnera the most effective means to win the favor of the people, and vied with one another in the frequency of the shows and the number of the combatants. Besides this, the same politicians made these shows a pretext for surrounding themselves with bands of bravos and bullies, all called gladiators whether destined for the arena or not, with which they started riots in the streets, broke up public meetings, overawed the courts and even directed or prevented the elections. Caesar’s preparations for an exhibition when he was canvassing for the aedileship (65 B.C.) caused such general fear that the senate passed a law limiting the number of gladiators that a private citizen might employ, and he was allowed to exhibit only 320 pairs.

The bands of Clodius and Milo made the city a slaughterhouse in 53 B.C., and order was not restored until late in the following year when Pompey as “sole consul” put an end to the battle of the bludgeons with the swords of his soldiers. During the Empire the number actually exhibited almost surpasses belief. Augustus gave eight mūnera, in which no less than ten thousand men fought, but these were distributed through the whole period of his reign. Trajan exhibited as many in four months only of the year 107 A.D., in celebration of his conquest of the Dacians. The first Gordian, emperor in 238 A.D., gave mūnera monthly in the year of his aedileship, the number of pairs running from 150 to 500. These exhibitions did not cease until the fifteenth century of our era.

Sources of Supply

In the early Republic the gladiators were captives taken in war, naturally men practiced in the use of weapons, who thought death by the sword a happier fate than the slavery that awaited them. This always remained the chief source of supply, though it became inadequate as the demand increased. From the time of Sulla training-schools were established in which slaves with or without previous experience in war were fitted for the profession. These were naturally slaves of the most intractable and desperate character. From the time of Augustus criminals were sentenced to the arena (later “to the lions”), but only non-citizens, and these for the most heinous crimes, treason, murder, arson, and the like. Finally in the late Empire the arena became the last desperate resort of the dissipated and prodigal, and these volunteers were numerous enough to be given as a class the name auctōrātī.

As the number of the exhibitions increased it became harder and harder to supply the gladiators demanded, for it must be remembered that there were exhibitions in many of the cities of the provinces and in the smaller towns of Italy as well as at Rome. The lines were, therefore, constantly crossed, and thousands died miserably in the arena whom only the most glaring injustice could number in the classes mentioned above. In Cicero’s time provincial governors were accused of sending unoffending provincials to be slaughtered in Rome and of forcing Roman citizens, obscure and friendless, of course, to fight in the provincial shows. Later it was common enough to send to the arena men sentenced for the pettiest offenses, when the supply of real criminals had run short, and to trump up charges against the innocent for the same purpose. The persecution of the Christians was largely due to the demand for more gladiators. So, too, the distinction was lost between actual prisoners of war and peaceful non-combatants; after the fall of Jerusalem all Jews over seventeen years of age were condemned by Titus to work in the mines or fight in the arena. Wars on the border were waged for the sole purpose of taking men who could be made gladiators, and in default of men, children and women were sometimes made to fight.

Schools for Gladiators

The training-schools for gladiators (lūdī gladiātōriī) have been mentioned already. Cicero during his consulship speaks of one at Rome, and there were others before his time at Capua and Praeneste. Some of these were set up by wealthy nobles for the purpose of preparing their own gladiators for mūnera which they expected to give; others were the property of regular dealers in gladiators, who kept and trained them for hire. The business was almost as disreputable as that of the lēnōnēs. During the Empire training-schools were maintained at public expense and under the direction of state officials not only in Rome, where there were four at least of these schools, but also in other cities of Italy where exhibitions were frequently given, and even in the provinces. The purpose of all the schools, public and private alike, was the same, to make the men trained in them as effective fighting machines as possible. The gladiators were in charge of competent training masters (lanistae); they were subject to the strictest discipline; their diet was carefully looked after, a special food (sagīna gladiātōria) being provided for them; regular gymnastic exercises were prescribed, and lessons given in the use of the various weapons by recognized experts (magistrī, doctōrēs). In their fencing bouts wooden swords (rudēs) were used. The gladiators associated in a school were collectively called a familia.

These schools had also to serve as barracks for the gladiators between engagements, that is, practically as houses of detention. It was from the school of Lentulus at Capua that Spartacus had escaped, and the Romans needed no second lesson of the sort. The general arrangement of these barracks may be understood from the ruins of one uncovered at Pompeii, though in this case the buildings had been originally planned for another purpose, and the rearrangement may not be ideal in all respects. A central court, or exercise ground is surrounded by a wide colonnade, and this in turn by rows of buildings two stories in height, the general arrangement being not unlike that of the peristyle of a house. The dimensions of the court are nearly 120 by 150 feet. The buildings are cut up into rooms, nearly all small (about twelve feet square), disconnected and opening upon the court, those in the first story being reached from the colonnade, those in the second from a gallery to which ran several stairways. These small rooms are supposed to be the sleeping-rooms of the gladiators, each accommodating two persons. There are seventy-one of them (marked 7 on the plan), affording room for 142 men. The uses of the larger rooms are purely conjectural. The entrance is supposed to have been at 3, with a room, 15, for the watchman or sentinel. At 9 was an exedra, where the gladiators may have waited in full panoply for their turns in the exercise ground, 1. The guard-room, 8, is identified by the remains of stocks, in which the refractory were fastened for punishment or safe-keeping. They permitted the culprits to lie on their backs or sit in a very uncomfortable position. At 6 was the armory or property room, if we may judge from articles found in it. Near it in the corner was a staircase leading to the gallery before the rooms of the second story. The large room, 16, was the mess-room, with the kitchen, 12, opening into it. The stairway, 13, gives access to the rooms above kitchen and mess-room, possibly the apartments of the trainers and their helpers.

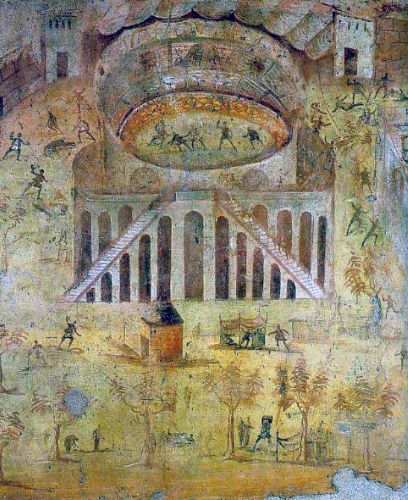

Places of Exhibition

During the Republic the combats of gladiators took place sometimes at the grave or in the circus, but regularly in the forum. None of these places was well adapted to the purpose, the grave the least of all. The circus had seats enough, but the spīna was in the way and the arena too vast to give all the spectators a satisfactory view of a struggle that was confined practically to a single spot. In the forum, on the other hand, the seats could be arranged very conveniently; they would run parallel with the sides, would be curved around the corners, and would inclose only sufficient space to afford room for the combatants. The inconvenience here was due to the fact that the seats had to be erected before each performance and removed after it, a delay to business if they were constructed carefully and a menace to life if they were put up hastily. These considerations finally led the Romans, as they had led the Campanians half a century before, to provide permanent seats for the mūnera, arranged as they had been in the forum, but in a place where they would not interfere with public or private business. To these places for shows of gladiators came in the course of time to be exclusively applied the word amphitheātrum, which had been previously given in its correct general sense to any place, the circus for example, in which the seats ran all the way around, as opposed to the theater in which the rows of seats were broken by the stage.

Amphitheaters at Rome

Ángel M. Felicísimo, Wikimedia CommonsJust when the first amphitheaters, in the special sense of the word, were erected at Rome can not be determined with certainty. The elder Pliny (†79 A.D.) tells us that in the year 55 B.C. Caius Scribonius Curio built two wooden theaters back to back, the stages being, therefore, at opposite ends, and gave in them simultaneous theatrical performances in the morning. Then, while the spectators remained in their seats, the two theaters were turned by machinery and brought together face to face, the stages were removed, and in the space they had occupied shows of gladiators were given in the afternoon before the united crowds. This story is all too evidently invented to account for the perfected amphitheater of Pliny’s time, which he must have interpreted to mean “a double theater.”

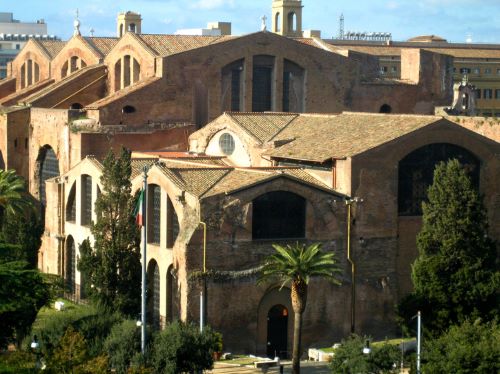

We are also told that Caesar erected a wooden amphitheater in 46 B.C., but we have no detailed description of it, and no reason to think that it was anything more than a temporary affair. In the year 29 B.C., however, an amphitheater was built by Statilius Taurus, partially at least of stone, that lasted until the great conflagration in the reign of Nero (64 A.D.). Nero himself had previously erected one of wood in the Campus. Finally, just before the end of the first century of our era, was completed the amphitheātrum Flāvium, later known as the colossēum or colisēum, which was large enough and durable enough to make forever unnecessary the erection of other similar structures in the city.

The Amphitheater at Pompeii

The essential features of an amphitheater may be most easily understood from the ruins of the one at Pompeii, erected about 75 B.C., almost half a century before the first permanent structure of the sort at Rome, and the earliest known to us from either literary or monumental sources. It will be seen at once that the arena and most of the seats lie in a great hollow excavated for the purpose, thus making sufficient for the exterior a low wall of hardly more than ten to thirteen feet in height. Even this wall was necessary on only two sides, as the amphitheater was built in the southeast corner of the city and its south and east sides were bounded by the city walls. The shape is elliptical, the major axis being 444 feet, the minor 342. The arena occupies the middle space. It was encircled by thirty-five rows of seats arranged in three divisions, the lowest (īnfima or īma cavea) having five rows, the second (media cavea) twelve, and the highest (summa cavea) eighteen. A broad terrace ran around the amphitheater at the height of the topmost row of seats. Access to this terrace was given from without by the double stairway on the west and by single stairways next the city walls on the east and south. Between the terrace and the top seats was a gallery, or row of boxes, each about four feet square, probably for women. Beneath the boxes persons could pass from the terrace to the seats. The amphitheater had seating capacity for about 20,000 people.

It was an ellipse with axes of 228 and 121 feet. Around it ran a wall a little more than six feet high, on a level with the top of which were the lowest seats. For the protection of the spectators when wild animals were shown, a grating of iron bars was put up on the top of the arena wall. Access to the arena and to the seats of the cavea īma and the cavea media was given by the two underground passageways, 1 and 2, of which 2 turns at right angles on account of the city wall on the south. From the arena ran also a third passage, 5, low and narrow, leading to the porta Libitinēnsis, through which the bodies of the dead were dragged with ropes and hooks. Near the mouths of these passages were small chambers or dens, marked 4, 4, 6, the purposes of which are not known. The floor of the arena was covered with sand, as in the circus, but in this case to soak up the blood as well as to give a firm footing to the gladiators.

Of the part of this amphitheater set aside for the spectators the cavea īma only was supported upon artificial foundations. All the other seats were constructed in sections as means were obtained for the purpose, the people in the meantime finding places for themselves on the sloping banks as in the early theaters. The cavea īma was strictly not supplied with seats all the way around, a considerable section on the east and west sides being arranged with four low, broad ledges of stone, rising one above the other, on which the members of the city council could place the seats of honor (bisellia) to which their rank entitled them. In the middle of the section on the east the lowest ledge is made of double width for some ten feet; this was the place set apart for the giver of the games and his friends. In the cavea media and the cavea summa the seats were of stone resting on the bank of earth. It is probable that all the places in the lowest section were reserved for people of distinction, that seats in the middle section were sold to the well-to-do, and that admission was free to the less desirable seats of the highest section.

The Coliseum

The Flavian amphitheater is the best known of all the buildings of ancient Rome, because to a larger extent than others it has survived to the present day. For our purpose it is not necessary to give its history or to describe its architecture; it will be sufficient to compare its essential parts with those of its modest prototype in Pompeii. The latter was built in the outskirts of the city, in a corner in fact of the city walls; the coliseum lay almost in the center of Rome, the most generally accessible of all the public buildings. The interior of the Pompeian structure was reached through two passages and by three stairways only, while eighty numbered entrances made it easy for the Roman multitudes to find their appropriate places in the coliseum. Much of the earlier amphitheater was underground; all of the corresponding parts of the coliseum were above the level of the street, the walls rising to a height of nearly 160 feet. This gave opportunity for the same architectural magnificence that had distinguished the Roman theater from that of the Greeks. The general effect is shown in Fig. 162, an exterior view of the ruins as they exist to-day.

The form is an ellipse with axes of 620 and 513 feet, the building covering nearly six acres of ground. The arena is also an ellipse, its axes measuring 287 and 180 feet. The width of the space appropriated for the spectators is, therefore, 166½ feet all around the arena. It will be noticed, too, that subterranean chambers were constructed under the whole building, including the arena. These furnished room for the regiments of gladiators, the dens of wild beasts, the machinery for the transformation scenes that Gibbon has described in his twelfth chapter, and above all for the vast number of water and drainage pipes that made it possible to turn the arena into a lake at a moment’s notice and as quickly to get rid of the water. The wall that surrounded the arena was fifteen feet high with the side faced with rollers and defended like the one at Pompeii with a grating or network of metal above it. The top of the wall was level with the floor of the lowest range of seats, called the podium as in the circus, and this had room for two or at the most three rows of marble thrones. These were for the use of the emperor and the imperial family, the giver of the games, the magistrates, senators, Vestal virgins, ambassadors of foreign states, and other persons of consequence.

The arrangement of the seats with the method of reaching them is shown in the sectional plan, Fig. 164. The seats were arranged in three tiers (maeniāna one above the other, separated by broad passageways and rising more steeply the farther they were from the arena, and were crowned by an open gallery. In the plan the podium is marked A. Twelve feet above it begins the first maeniānum, B, with fourteen rows of seats reserved for members of the equestrian order. Then came a broad praecīnctiō and after it the second maeniānum, C, intended for ordinary citizens. Back of this was a wall of considerable height and above it the third maeniānum, D, supplied with rough wooden benches for the lowest classes, foreigners, slaves, and the like. The row of pillars along the front of this section made the distant view all the worse. Above this was an open gallery, E, in which women found an unwelcome place. No other seats were open to them unless they were of sufficient distinction to claim a place upon the podium. At the very top of the outside wall was a terrace, F, in which were fixed masts to support the awnings that gave protection against the sun. The seating capacity of the coliseum is said to have been 80,000, and it had standing room for 20,000 more.

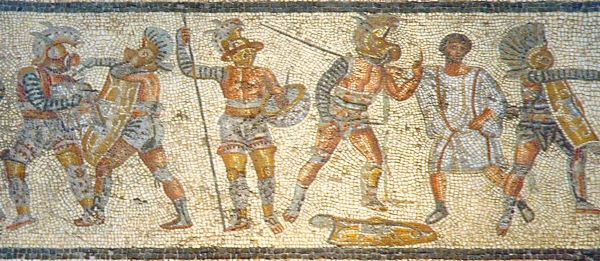

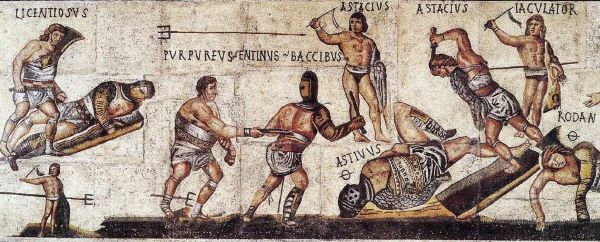

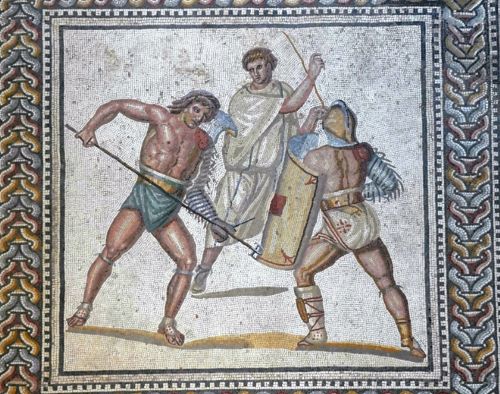

Styles of Fighting

Gladiators fought usually in pairs, man against man, but sometimes in masses (gregātim, catervātim). In early times they were actually soldiers, captives taken in war, and fought naturally with the weapons and equipment to which they were accustomed. When the professionally trained gladiators came in, they were given the old names, and were called Samnites, Thracians, etc., according to their arms and tactics. In much later times victories over distant peoples were celebrated with combats in which the weapons and methods of war of the conquered were shown to the people of Rome; thus, after the conquest of Britain essedāriī exhibited in the arena the tactics of chariot fighting which Caesar had described generations before in his Commentaries. It was natural enough, too, for the people to want to see different arms and different tactics tried against each other, and so the Samnite was matched against the Thracian, the heavy armed against the light armed. This became under the Empire the favorite style of combat.

Finally when people had tired of the regular shows, novelties were introduced that seem to us grotesque; men fought blindfold (andabatae), armed with two swords (dimachaerī), with the lasso (laqueatōrēs), with a heavy net (rētiāriī), and there were battles of dwarfs and of dwarfs with women. Of these the rētiārius became immensely popular. He carried a huge net in which he tried to entangle his opponent, always a secūtor (see below), despatching him with a dagger if the throw was successful. If unsuccessful he took to flight while preparing his net for another throw, of if he had lost his net tried to keep his opponent off with a heavy three-pronged spear (fuscina), his only weapon beside the dagger.

Weapons and Armor

The armor and weapons used in these combats are known from pieces found in various places, and from paintings and sculpture, but we are not always able to assign them to definite classes of gladiators. The oldest class was that of the Samnites. They had belts, thick sleeves on the right arm (manica), helmets with visors, greaves on the left leg, short swords, and the long shield (scūtum). Under the Empire the name Samnite was gradually lost and gladiators with equivalent equipment were called hoplomachī (heavy armed), when matched against the lighter armed Thracians, and secūtōrēs, when they fought with the rētiāriī.

The Thracians had much the same equipment as the Samnites, the mark of distinction being the small shield (parma) in place of the scūtum and, to make up the difference, greaves on both legs. They carried a curved sword. The Gauls were heavy armed, but we do not know how they were distinguished from the Samnites. In later times they were called murmillōnēs, from an ornament on their helmets shaped like a fish (mormyr). The rētiāriī had no defensive armor except a leather protection for the shoulder. Of course the same man might appear by turns as Samnite, Thracian, etc., if he was skilled in the use of the various weapons.

Announcement of the Shows

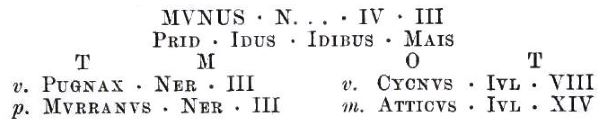

The games were advertised in advance by means of notices painted on the walls of public and private houses, and even on the tombstones that lined the approaches to the towns and cities. Some are worded in very general terms, announcing merely the name of the giver of the games with the date:

A • SVETTI • CERTI AEDILIS • FAMILIA • GLADIATORIA • PUGNAB • POMPEIS PR • K • JVNIAS • VENATIO • ET • VELA • ERUNT

“On the last day of May the gladiators of the Aedile Aulus Suettius Certus will fight at Pompeii. There will also be a hunt and the awnings will be used.”

Others promise in addition to the awnings that the dust will be kept down in the arena by sprinkling. Sometimes when the troop was particularly good the names of the gladiators were announced in pairs as they would be matched together, with details as to their equipment, the school in which each had been trained, the number of his previous battles, etc. To such a notice on one of the walls in Pompeii some one added after the show the result of each combat. The following is a specimen only of this announcement:

“The games of N… from the 12th to the 15th of May. The Thracian Pugnax, of the gladiatorial school of Nero, who has fought three times will be matched against the murmillō Murranus, of the same school and the same number of fights. The hoplomachus Cycnus, from the school of Julius Caesar, who has fought eight times will be matched with the Thracian Atticus of the same school and of fourteen fights.”

The letters in italics before the names of the gladiators were added after the exhibition by some interested spectator, and stand for vīcit, periit, and missus (“beaten, but spared”). Other announcements added to such particulars as those given above the statement that other pairs than those mentioned would fight each day, this being meant to excite the curiosity and interest of the people.

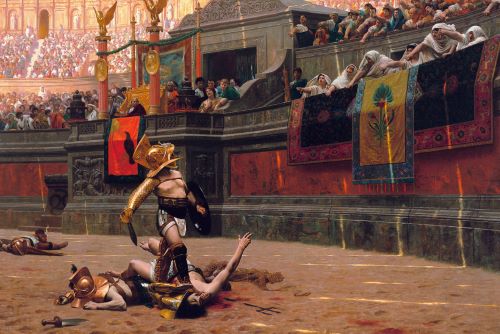

The Fight Itself

The day before the exhibition a banquet (cēna lībera) was given to the gladiators and they received visits from their friends and admirers. The games took place in the afternoon. After the ēditor mūneris had taken his place, the gladiators marched in procession around the arena, pausing before him to give the famous greeting: moritūrī tē salūtant. All then retired from the arena to return in pairs according to the published programme. The show began with a series of sham combats, the prōlūsiō, with blunt weapons. When the people had had enough of this the trumpets gave the signal for the real exhibition to begin. Those reluctant to fight were driven into the arena with whips or hot iron bars.

If one of the combatants was clearly overpowered without being actually killed, he might appeal for mercy by holding up his finger to the ēditor. It was customary to refer the plea to the people, who waved cloths or napkins to show that they wished it to be granted, or pointed their thumbs downward as a signal for death. The gladiator who was refused release (missiō) received the death blow from his opponent without resistance. Combats where all must fight to the death were said to be sine missiōne, but these were forbidden by Augustus. The body of the dead man was dragged away through the porta Libitinēnsis, sand was sprinkled or raked over the blood, and the contests were continued until all had fought.

The Rewards

Before making his first public appearance the gladiator was technically called a tīrō. After his first victory he received a token of wood or ivory, which had upon it his name and that of his master or trainer, a date, and the letters SP, SPECT, SPECTAT, or SPECTAVIT, meaning perhaps populus spectāvit. When after many victories he had proved himself to be the best of his class, or second best, in his familia, he received the title of prīmus, or secundus, pālus. When he had won his freedom he was given a wooden sword (rudis). From this the titles prīma rudis and secunda rudis seem to have been given to those who were afterwards employed as training masters (doctōrēs) in the schools.

The rewards given to famous gladiators by their masters and backers took the form of valuable prizes and gifts of money. These may not have been so generous as those given to the aurīgae, but they were enough to enable them to live in luxury the rest of their lives. The class of men, however, who followed this profession probably found their most acceptable reward in the immediate and lasting notoriety that their strength and courage brought them. That they did not shrink from the īnfamia that the profession entailed is shown by the fact that they did not try to hide their connection with the amphitheater. On the contrary, their gravestones record their classes and the number of their victories, and have often cut upon them their likenesses with the rudis in their hands.

Other Shows in the Amphitheater

Of other games that were sometimes given in the amphitheaters something has been said in connection with the circus. The most important were the vēnātiōnēs, hunts of wild beasts. These were sometimes killed by men trained to hunt them, sometimes made to kill each other. As the amphitheater was primarily intended for the butchery of men, the vēnātiōnēs given in it gradually but surely took the form of man-hunts. The victims were condemned criminals, some of them guilty of crimes that deserved death, some of them sentenced on trumped up charges, some of them (and among these were women and children) condemned “to the lions” for political or religious convictions. Sometimes they were supplied with weapons, sometimes they were exposed unarmed, even fettered or bound to stakes, sometimes the ingenuity of their executioners found additional torments for them by making them play the parts of the sufferers in the tragedies of mythology.

The arena was well adapted, too, for the maneuvering of boats, when it had been flooded with water, and naval battles (naumachiae) were often fought within the coliseum as desperate and as bloody as some of those that have given a new turn to the history of the world. The earliest exhibitions of this sort were given in artificial lakes, also called naumachiae. The first of these was dug by Caesar, for a single exhibition, in 46 B.C. Augustus had a permanent basin constructed in 2 B.C., measuring 1,800 by 1,200 feet, and four others at least were built by later emperors.

Roman Baths

Overview

To the Roman of early times the bath had stood for health and decency only. He washed every day his arms and legs, for the ordinary costume left them exposed, his body once a week. He bathed at home, using a very primitive sort of wash-room, situated near the kitchen in order that the water heated on the kitchen stove might be carried into it with the least possible inconvenience. By the last century of the Republic all this had changed, though the steps in the change can not now be followed. The bath had become a part of the daily life as momentous as the cēna itself, which it regularly preceded. It was taken, too, by preference in one of the public bathing establishments which were by this time operated on a large scale in all parts of Rome and also in the smaller towns of Italy and even in the provinces.

These offered all sorts of baths, plain, plunge, douche, with massage (Turkish), and besides in many cases features borrowed from the Greek gymnasia, exercise grounds, courts for various games, reading and conversation rooms, libraries, gymnastic apparatus, everything in fact that our athletic clubs now provide for their members. The accessories had become really of more importance than the bathing itself and justify the description of the bath under the head of amusements. In places where there were no public baths, or where they were at an inconvenient distance, the wealthy fitted up bathing places in their houses, but no matter how elaborate they were the private baths were merely a makeshift at best.

Essentials for the Bath

The ruins of the public and private baths found all over the Roman world, together with a dissertation by Vitruvius, and countless allusions in literature, make very clear the general construction and arrangement of the bath, but show that the widest freedom was allowed in matters of detail. For the luxurious bath of classical times four things were thought necessary: a warm ante-room, a hot bath, a cold bath, and the rubbing and anointing with oil. All these might have been had in a single room, as all but the last are furnished in every modern bathroom, but as a matter of fact we find at least three rooms set apart for the bath in very modest private houses and often five or six, while in the public establishments this number may be multiplied several times. In the better equipped houses were provided: (1) A room for undressing and dressing (apodytērium), usually unheated, but furnished with benches and often with lockers for the clothes; (2) the warm ante-room (tepidārium), in which the bather waited long enough for the perspiration to start, in order to guard against the danger of passing too suddenly into the high temperature of the next room; (3) the hot room (caldārium) for the hot bath; (4) the cold room (frīgidārium) for the cold bath; (5) the ūnctōrium, the room for the rubbing and anointing with oil that finished the bath, from which the bather returned into the apodytērium for his clothes.

In the more modest houses space was saved by using a room for several purposes. The separate apodytērium might be dispensed with, the bather undressing and dressing in either the frīgidārium or tepidārium according to the weather; or the ūnctōrium might be saved by using the tepidārium for this purpose as well as for its own. In this way the suite of five rooms might be reduced to four or three. On the other hand, private houses had sometimes an additional hot room without water (lacōnicum), used for a sweat bath, and a public bathhouse would be almost sure to have an exercise ground (palaestra), with a pool at one side (piscīna) for a cold plunge and a room adjacent (dēstrictārium) in which the sweat and dirt of exercise were scraped off with the strigilis before and after the bath. It must not be supposed that all bathers went the round of all the rooms in the order given above, though that was common enough. Some would dispense with the hot bath altogether, taking instead a sweat in the lacōnicum, or failing that, in the caldārium, removing the perspiration with the strigil, following this with a cold bath (perhaps merely a shower or douche) in the frīgidārium and the rubbing with linen cloths and anointing with oil. Young men who deserted the campus and the Tiber for the palaestra and the bath would content themselves with removing the effects of their exercise with the scraper, taking a plunge in the open pool, and then a second scraping and the oil. Much would depend on the time and the tastes of individuals, and physicians laid down strict rules for their patients to follow.

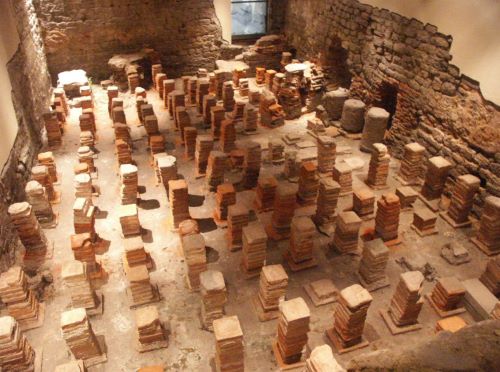

Heating the Bath

The arrangement of the rooms, were they many or few, depended upon the method of heating. This in early times must have been by stoves placed in the rooms as needed, but by the end of the Republic the furnace had come into use, heating the rooms as well as the water with a single fire. The hot air from the furnace was not conducted into the rooms directly, as it is with us, but was made to circulate under the floors and through spaces between the walls, the temperature of the room depending upon its proximity to the furnace. The lacōnicum, if there was one, was put directly over the furnace, next to it came the caldārium and then the tepidārium, while the frīgidārium and the apodytērium having no need of heat were at the greatest distance from the fire and without connection with it. If there were two sets of baths in the same building, as there sometimes were for the accommodation of both men and women at the same time, the two caldāria were put on opposite sides of the furnace and the other rooms were connected with them in the regular order, the two entrances being at the greatest distance apart.

There were really two floors, the first being even with the top of the firepot, the second (suspēnsūra) with the top of the furnace. Between them was a space of about two feet into which the hot air passed. On the top of the furnace, just above the level, therefore, of the second floor, were two kettles for heating the water. One was placed well back, where the fire was not so hot, and contained water that was kept merely warm; the other was placed directly over the fire and the water in it, received from the former, was easily kept intensely hot. Near them was a third kettle containing cold water. From these three kettles the water was piped as needed to the various rooms.

The hot water bath was taken in the caldārium (cella caldāria), which served also as a sweat bath when there was no lacōnicum. It was a rectangular room and in the public baths was longer than wide (Vitruvius says the proportion should be 3:2) with one end rounded off like an apse or bay window. At the other end stood the large hot water tank (alveus), in which the bath was taken by a number of persons at a time. The alveus (Fig. 173) was built up two steps from the floor of the room, its length equal to the width of the room and its breadth at the top not less than six feet. At the bottom it was not nearly so wide, the back sloping inward, so that the bathers could recline against it, and the front having a long broad step, for convenience of descent into it, upon which, too, the bathers sat. The water was received hot from the furnace, and was kept hot by a metal heater (testūdō), opening into the alveus and extending beneath the floor into the hot air chamber. Near the top of the tank was an overflow pipe, and in the bottom was an escape pipe which allowed the water to be emptied on the floor of the caldārium, to be used for scrubbing it. In the apse-like end of the room was a tank or large basin of metal (lābrum, solium), which seems to have contained cool water for the douche. In private baths the room was usually rectangular and then the lābrum was placed in a corner. For the accommodation of those using the room for the sweat bath only, there were benches along the wall. The air in the caldārium would, of course, be very moist, while that of the lacōnicum would be perfectly dry, so that the effect would not be precisely the same.

The Frigidarium and Unctorium

The frīgidārium (cella frīgidāria) contained merely the cold plunge bath, unless it was made to do duty for the apodytērium, when there would be lockers on the wall for the clothes (at least in a public bath) and benches for the slaves who watched them. Persons who found the bath too cold would resort instead to the open swimming pool in the palaestra, which would be warmed by the sun. In one of the public baths at Pompeii a cold bath seems to have been introduced into the tepidārium, for the benefit, probably, of invalids who found even the palaestra too cool for comfort. The final process, that of scraping, rubbing, and oiling, was exceedingly important. The bather was often treated twice, before the warm bath and after the cold bath; the first might be omitted, but the second never.

The special room, ūnctōrium, was furnished with benches and couches. The scrapers and oils were brought by the bathers, usually carried along with the towels for the bath by a slave (capsārius). The bather might scrape (dēstringere) and oil (deungere) himself, or he might receive a regular massage at the hands of a trained slave. It is probable that in the large baths expert operators could be hired, but we have no direct testimony on the subject. When there was no special ūnctōrium the tepidārium or apodytērium was made to do instead.

A Private Bathhouse