Following the life course, running from birth to old age and death.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Household and Family in Early Modern History (ca. 1500–1800)

By Dr. Sarah Carmichael

Assistant Professor of Social and Economic History

Utrecht University

By Dr. Xenia von Tippelskirch

Chair of Religious Dynamics

Goethe-Universität

Overview

Since Aristotle, there has been a thread of thought which maintains that the way parents and children, as well as husbands and wives, relate to each other forms a subconscious model for political systems, serving as the template for how the individual relates to authority. Whether one subscribes to this view or not, everyday life and the organisation of society at the family and household levels are clearly fundamental to how European societies have functioned over time. Yet such topics were for a long time neglected by historians, who focused narrowly on economic and political developments or who relegated them to the field of women’s history, which they treated as separate and non-essential. When it comes to our historical understanding of family and household, a lot of what people presume is true of the past is based either on the behaviour of elites, on portrayals in literature, or on ideologically framed, older research. For instance, the idea persists that historically, girls across Europe married universally and usually in their teens, or that large family groups were the norm for all societies. Many of these assumptions, however, do not stand up to scrutiny.

Examining the setup of care duties often associated with female roles in society (childbearing and -rearing, housekeeping etc.) can help us understand developments in a given period, not just for women themselves but for societies as a whole. In this sub-chapter we sketch the most important characteristics of family and household in early modern Europe, drawing out temporal and geographical distinctions where necessary. The origin of these regional differences is debated, with some historians arguing that differences in legal systems, inheritance regimes, or agrarian practices (such as the presence or absence of certain types of plough technology) are at the bottom of these differences. It is in any case important to differentiate between rural and urban settings and between the conditions of high nobility and peasants. Furthermore, the distinction between family and household also differs between contexts. Sometimes all individuals living together in domestic groups will be related by blood but in other situations there may be many additions to the basic domestic unit in the form of lodgers, servants, apprentices, and so on. Historians have tended to find it easier to research domestic residential groups (i.e., households) than kinship networks.

The structure of this essay follows that of the life course, running from birth (including infanticide), children and childhood, marriage, households and servants, to old age and death (including inheritance regimes). Finally, we will focus on how early modern houses were furnished and on the role of property during one’s lifetime and after one’s death.

Childbirth and Childhood

Childbirth and childhood were highly risky periods for those born in the early modern period. But during this period important changes also took place in how both were dealt with and both topics have stimulated wide-ranging research on various subjects associated with infancy. The focus on birth has allowed social historians (especially since the 1970s) to reconstruct the particular position that women occupied in early modern families, to question the role of legitimacy and how transmission of heritage was managed. Investigations of the history of childbirth have also given us insight into the anatomical and medical knowledge of the period. In this context, religious dimensions proved to be very important: the questions of when a foetus was actually alive and the fate of children who died unbaptised occupied contemporaries intensely. Early modern mortality rates for mothers and newborns were extremely high, with roughly twenty-seven precent of infants not living to see their first birthday (and about half didn’t make it to adulthood), and four to five births out of every thousand leading to the death of the mother. (Taking into account that mothers in this period were likely to have multiple children, the risk for any given mother was therefore much higher.) Thus, births were accompanied by religious and magical rituals by which contemporaries hoped to achieve a fortuitous birth. Once the child was born, efforts were made to baptise it as quickly as possible in order to integrate it into the community of believers.

Throughout the early modern period children were born at home with the help of midwives, who mostly passed on their knowledge orally. We know of the practices that characterised midwifery thanks to the regulations of territorial authorities, but also through some medical literature—Eucharius Rösslin’s Der Rosengarten (The Rose Garden), an illustrated text from 1513 that circulated widely throughout the sixteenth century in Latin, English, French, and Italian translations. From the seventeenth century onwards, we also have treatises written by midwives. The French royal midwife Louise Bourgeois (1563–1636) was the first woman to publish about her art; the handbook of the court midwife Justine Siegemund (1636–1705) from Lower Silesia enjoyed particular success. In her richly illustrated book, which she compiled on the basis of her readings and her own practical experience, she primarily addressed other midwives she wanted to teach. Siegemund shows how assistance could be given during birth. Another famous treatise by the Parisian midwife Angélique Marguerite Le Boursier du Coudray (first published in 1759) even had coloured plates in its second edition (1777). The rarity of such colour illustrations proves that it was a very popular text, for which such expensive additions were seen as worthwhile. These works reveal how midwives dealt with difficult births, but also which instruments and manual techniques they used, how they performed emergency baptisms and, more generally, the ways in which the unborn were imagined.

At the end of the eighteenth century, responsibilities shifted: midwives were no longer chosen by childbearing women as before, but instead had to pass examinations organised by (male) physicians. The first lying-in hospitals were established during the eighteenth century. If one compares the situation in Europe, then clear differences become visible. For example, the university-affiliated lying-in hospital (Accouchierhaus) established in Göttingen in 1751 served primarily to train male obstetricians. Lying-in hospitals in Catholic countries existed in part to offer unmarried women the possibility to preserve their honour. In Milan (since 1780) and Paris (Office des Accouchées of the Hôtel-Dieu, founded in 1378 but with vastly greater influence in the latter half of the eighteenth century), they were directly connected to foundling homes. In England, however, hospitals such as the Lying-in Hospital for Married Women (established in London in 1749) accepted only poor married women and existed thanks to philanthropic organisations. Throughout Europe, at the beginning of this process of medicalisation, the risk of infection (childbed fever) in these clinics was extremely high, so that better-off women preferred to give birth at home until the nineteenth century. In some regions, newborns were systematically given to wet nurses. In Tuscany, sometimes fathers-to-be were involved in discussions about the choice of wet nurse, demonstrating that the task of caring for newborns was not an exclusively female one.

With the increasing regulation and institutionalisation of marriages in the course of the Reformation and Catholic reform, pregnancy outside marriage became a real problem. Until well into the sixteenth century, a marriage vow and consummation of the marriage had been sufficient to declare a marriage legally valid. However, in subsequent decades ecclesiastical authorities increasingly required marriages to take place before a priest and in the presence of witnesses. At the same time, they stigmatised extramarital sexual intercourse. Unmarried women who were pregnant affirmed their good faith and honourable status in church courts, hoping to obtain marriage and recognition for their children. They were not always successful. Sometimes the social pressure was so great that they saw no other way out than to get rid of the unwanted newborn.

Unlike in many other parts of the world, not much evidence has been found for sex-selective infanticide or child abandonment in early modern Europe. The Constitutio Criminalis Carolina (1532) defined infanticide as a crime, ordered torture for questioning suspects, and threatened the death penalty. Those who had deprived still unbaptised children of the possibility of salvation were to be punished severely. Thus, in the area of the Holy Roman Empire, the rules for dealing with child murderers were clearly defined. Research has found different patterns in dealing with suspected child murderers. Proceedings were not always initiated at all, as the evidence was often difficult to produce. There also seem to have been marked differences between urban and rural and Catholic and Protestant areas. At the end of the eighteenth century, there was an increasing number of voices arguing for awareness of the impact of social pressures on single women from the lower classes and thus for a reduction of the penalty.

Childhood was a concept of growing importance in early modern Europe, though historians differ in how they assess it. Some have argued that modern childhood emerged in the transition from the Middle Ages to the early modern period or that the sentiment of motherly love was ‘invented’ in the seventeenth century, while others point to later changes during the Victorian era. No matter what position one takes, it is clear that something indeed changed in the understanding of childhood over the course of the early modern period. Children started to gain a status of their own, no longer seen merely as tiny adults but increasingly as innocents in need of protection from the adult world (particularly from the world of work). Education thus took on increasing importance. Early childhood education was a family affair in this period, especially for girls from the lower classes, who were educated within the framework of their families. But this period also saw a steady increase in schooling, often provided by the church. Many middle-class boys and even some girls were sent to school around age six, certainly in Britain but also in other parts of Europe. Apprentices and periods of servitude long remained a normal part of childhood, with the guild system creating opportunities for parents to outsource the housing and education of their children to a skilled master. Communal institutions also emphasised the importance of charity and education for abandoned children, trying to keep boys out of gangs and girls out of prostitution. Orphanages were introduced in various regions partly in order to reduce infanticide—the baby hatches or foundling wheels found in many churches during the medieval and early modern periods bear testimony to that.

The Adult World and the Household

In early modern Europe, key stages of adult life were defined by marriage, work, old age, and death, each of which had an impact on the organisation of the household as an institution. Much of the historical work on marriage in early modern Europe revolves around proving or disproving the claims of John Hajnal. Hajnal was a mathematician who, in 1965, identified a geographic line running through Europe from Trieste to St Petersburg which seemed to separate Europe into two marriage systems: one in the east, where marriage was universal, where women married young to partners substantially older than themselves, and another system in the west, in which at least ten precent of people remained unmarried, while women married around the age of twenty-three to men who were, on average, two and a half years older. This contrast between the two halves of Europe has been much critiqued, but a picture has emerged which confirms that, at least for England and the Netherlands, marriage ages were (and remain) high for both men and women. However, the debate around this topic has demonstrated that rather than a strict line of division across the continent, it might be more accurate to talk of a gradient, with Central Europe representing an intermediate case where marriage ages were lower than in the west but higher than in the east. We therefore see, roughly speaking, marriage ages of twenty-four and above (often substantially so) for both men and women in north-western Europe, between twenty and twenty-four for women in Central and Southern Europe, and under twenty for women in many parts of Eastern Europe, though the male age at marriage is often substantially higher in these regions.

In a period where contraception methods were unreliable and sex outside of marriage was frowned upon (though pre-marital sex did occur, and frequently), marriage ages had a direct effect on the number of children women bear. Relatively close ages of spouses have been linked to a more consensual, equitable type of relationship. Studies of present-day couples show that in regions where the age gap between husband and wife is large, with husbands much older than their brides, this leads to more exposure to domestic violence, less investment in children’s (particularly girls’) schooling and less say in important decisions such as the distribution of expenditure on health care.

One factor which may explain higher marriage ages in north-western Europe is the fact that couples, upon getting married, were expected to establish their own households. This meant that time was needed to train, work and save enough to do so. While households in Eastern Europe consisted largely of family members related by blood, west of the so-called ‘Hajnal line’, live-in servants and lodgers frequently extended the otherwise ‘nuclear family’ (i.e. a married couple and their children). These servants were often (although not always) young employees working for wages. This system led to a life-cycle in which a period of service was the norm in north-west Europe, as opposed to the situation in Eastern Europe. At almost all levels of society, families in north-west Europe sent their adolescent children out of their households to work as servants or apprentices, to board near a teacher or school, or to perform service for royalty. This mobility was notable to visitors from further afield. Life-cycle service died out with the shift from pre-industrial to industrialised production techniques, which was detrimental to the position of women, as they no longer had access to labour markets in which to gain skills and earn wages.

In addition to pointing out the significance of marriage patterns, research has been conducted on the legal and confessional dimensions of marriage. Very often, religious conversion was a precondition to marriage. The existence of denominationally mixed marriages demonstrates how fluid confessional identities could be in the early modern context. Dowries had to be negotiated in each case, but economic considerations were not the only connection between spouses. In cases of domestic violence or other marital conflict, divorce was only possible in Protestant countries. In Catholic areas, it was sometimes possible to obtain a dispensation on proof of an unconsummated marriage or to demand separation from table and bed before a church court. The petitions and testimonies required in the context of investigations and court trials provide insights into what early modern people had to say about their everyday married life. What often emerges is that those living in the early modern period had a lot more “agency” than we might sometimes assume, and that particularly women petitioned courts to uphold promises of marriage where they had not been fulfilled and they were left literally holding the baby.

An important feature of how the life-cycles of households were arranged is what happened after death. Although life expectancy at birth for the early modern period sat at around thirty to thirty-five years of age, most individuals who survived infancy could expect to live much longer—perhaps to around the age of sixty. This also meant that some degree of old age care provision was often necessary. In the Netherlands, early forms of retirement homes emerged where elderly couples could pay in advance for care. In many other parts of Europe, care by family members remained the norm. These patterns of what different generations do for each other and how they live together have long historical roots, with ramifications right through to the present day. In Spain and Italy, for example, even the state provision of old age care today is heavily influenced by the idea that it is your children who care for you once you are no longer able to do so. Households in north-western Europe were frequently extended by live-in servants, or lodgers who provided commercialised care or the money with which to buy care.

Households of course exist not only as a set of relationships but also as tangible, material spaces. Historians like Raffaella Sarti have demonstrated the significance of objects in the context of early modern households. Young couples needed to procure the material conditions of living together, with basic necessities including a bed and a fireplace. The early modern period also witnessed a growing demand for luxury goods such as the wave of goods that became available through colonial trading networks, with spices and textiles from Asia arriving in the European market. This contributed to the so-called “industrious revolution”, a shift in which households devoted more time to employment and less to leisure in order to afford luxuries. Tied in with this, the putting-out system—subcontracting manufacturing tasks to remote workers—meant that manufacturers across Western Europe in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries could tap into a large labour supply available in rural households. The ability to produce goods for manufacturers at home while combining this with agrarian work meant that rural households could increase monetary incomes. As a result, early modern urban households became further embedded in a monetary system and the market, both in terms of production and consumption.

Conclusion

This chapter has shown that household and family arrangements across Europe differed greatly across the continent, including distinct east/west variants associated with marriage patterns. These differences are debated but also had a significant impact on how societies operated. It is often argued that those from regions where networks were based on extended family ties put trust in the extended family over market-based relationships, whereas in a nuclear family setting individuals perhaps engaged more actively with the marketplace and put more trust in anonymous transactions, thereby fostering the rise of individualism and capitalism. Households and families are therefore key to our understanding of many other important historical processes. They also help to explain the emergence or persistence of disparities across the continent. Smaller nuclear households in north-west Europe provided less of a safety net to fall back on when times were hard. These ‘weaker’ family ties can also be linked to the development of forms of collective action (i.e. where people work together to improve their lot and to achieve a common goal) such as guilds, commons, and other collaborative forms that were based on common interests rather than family ties.

Household and Family in Modern History (ca. 1800–1900)

By Dr. Sarah Carmichael

Assistant Professor of Social and Economic History

Utrecht University

By Dr. Darina Martykánová

Historian and Assistant Professor

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

By Dr. Mónika Mátay

University Associate Professor

Eötvös Loránd University

By Dr. Julia Moses

Assistant Professor and Reader in Modern History

University of Sheffield

Overview

Improvements in agriculture and the industrial revolution had a profound effect on European societies, not just economically but also in the way that households and families were organised, largely through its impact on the way that people earned their incomes. The timing of the increase in agricultural productivity and the industrial revolution differed across the continent. Its impact was shaped by the pre-existing forms of household and family organisation and by the political context. However, the establishment of a system whereby income for a large part of the population was earned by working in mining, industrial establishments and services had a number of significant consequences for the family and household. First, it meant that household work in cottage industries began to decline, as work was increasingly undertaken outside the home. Second, and relatedly, larger family and kinship networks were no longer regarded as necessary for contributing to household industries, and individuals began to seek work elsewhere, including far from home. Finally, the shift to industrial work meant that labour increasingly came to be seen as something performed by male family ‘breadwinners’, even if the important contributions of women and child workers continued.

These developments, of course, varied dramatically across Europe and even within individual countries. For this reason, among others, historians and social scientists have debated whether there has been a single model of the ‘European family’. Some have debated over divisions between north-western Europe and the rest of the continent. Others have pointed out specifically Eastern European or Southern European family models in which agriculture and intergenerational families played a greater role into the early twentieth century—though even in these regions, nuclear families (based on a mother, father and their children) were the most common pattern in cities. The idea of a European family model has also been questioned by scholars who have argued that households based on the nuclear family were not necessarily the norm in the past, despite popular memory. Indeed, a number of scholars have highlighted the role of single mothers and patchwork families during this period, not least because of spousal abandonment and widowhood in an era of high mortality and difficult divorce laws.

Nonetheless, despite these variations within the history of the family and household, there were several common trends during this period, including the predominance of patriarchy—the rule of the father, which determined the legal status of women and children as well as how households were generally governed. Moreover, in this era of mass migration and imperial expansion, frequent encounters with ‘others’ of various kinds helped to solidify certain ideas about what families and households should look like in particular countries or societies.

This chapter draws attention to several facets of these issues, including the vast socioeconomic and legal changes affecting marriage and the family, as well as cultural redefinitions of the family and the often moralising discourses surrounding sexuality, which likewise shaped the household and the family in modern Europe.

Changing Economic and Legal Frameworks

The industrial revolution, which took hold at different times in different countries, had profound effects on how households functioned. Both the guild system and the ‘putting-out’ system were replaced almost wholesale by factory production. The rise of factory production and wage labour meant that, where previously households had operated as units of production, goods were now increasingly manufactured outside the home. This meant that remuneration for paid labour became increasingly important as households became ever less self-sufficient. At the same time, an ideal model of family organisation emerged among upper-middle-class families whereby men should earn the sole income to support the household, with women focused on creating a domestic sphere. This so-called male breadwinner model persists to the present day, but its origins are to be found in the time of industrialisation, when wages that had previously been paid to a household were increasingly paid to individuals. However, this was only ever an ideal. In reality, particularly in poorer households, women and children did a lot of work both in and outside the home. And of course, a male breadwinner household could only exist if the male of the household was alive and present. For many households, death and disappearance, travel for work or conscription to fight in wars led to men’s absence, leaving women and children to make do as best they could. In many European countries, such as Spain, Portugal or France, the concept of the man as an exclusive breadwinner did not become hegemonic in the nineteenth century, and men welcomed their wives and single daughters bringing complementary income home—so long as men remained by law the supreme authority (chef de famille, cabeza de familia) in the household.

Parallel to the advance of industrialisation across much of Western Europe, there emerged another significant development: the rise of the modern state. In the late eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century, states around Europe began to develop modern bureaucracies, new tax systems and comprehensive legal codes which enabled them to know more about the families that lived within them. These developments also enabled states to shape families in new ways, largely as a result of the shift in power over daily affairs from religious institutions to governmental ones.

This transformation could be seen, first of all, in the domain of family law, which became a distinct area of jurisprudence from the eighteenth century and began to outline how to deal with areas such as marriage, inheritance, adoption, and divorce. The emergence of new civil codes in the wake of the French Revolution and various subsequent revolutions over the nineteenth century also brought about clear rules on matters pertaining to the household and family. For example, the Prussian Civil Code of 1794 declared the purpose of marriage as mutual support, both financial and procreative. Just a few years later, in 1804, the French Civil Code, which had been introduced in the Napoleonic backlash against the French Revolution, marked a return to more conservative rules on marriage and the family after various revolutionary-era experiments that had included rights to civil marriage and divorce, as well as women’s rights within marriage.

These legal developments were a watershed in the relationship of the family (and household more generally) with the states in which they resided. To be sure, the family had previously been subject to some governmental regulations and was certainly subjected to church rules on a wide variety of matters, from incest to marriage and its collapse. Throughout much of European history, marriage had been seen as a sacrament, a sacred ritual within Christianity that bestowed divine grace. As such, various church edicts in the medieval and early modern period allowed people to marry as long as they chose to do so freely, and as long as they married in front of witnesses who could testify to the new union. The marriage contract was effectively between the couple and God, not between the families of the marrying couple or as an act before the state. The advent of new Protestant traditions in the early modern period meant that, at least for Protestants, marriage was no longer seen as a sacrament, but it was still upheld as something special and worthy of protection.

New legislation that took off with the French Revolution was therefore a radical change, as were the reforms instituted by various civil codes afterwards. One of the most significant changes was the introduction of compulsory civil marriage, which meant that individuals needed to marry through the state—at state registry offices or with judges—rather than through the church, even if they chose to marry in the church afterwards. In countries that adopted laws on civil marriage, the only marriages that were valid were those registered with the state. The civil marriage movement took off across much of Europe over the course of the long nineteenth century, for example, in France (1792), Prussia (1794) and as an option in England in 1836, and its roots could also be seen in earlier attempts to separate matters of church and state, such as Austria’s 1783 Marriage Patent.

Alongside marriage, divorce and marital separation shifted to the centre of debates about changing policies on the family in nineteenth-century Europe. Under Catholicism, separation ‘from bed and board’ was allowed in cases of marital breakdown, but not divorce. Protestants allowed divorce, but rules varied widely, with some more restrictive than others. Against this backdrop, different states gradually introduced laws on divorce and these varied, for example, with allowances only in case of spousal abuse, abandonment or adultery. Rules on divorce also varied within countries, depending on how unified their legal systems were. For example, in Germany, divorce was easier to obtain within predominantly Protestant Prussia than within predominantly Catholic Bavaria. In Austria and in the Ottoman Empire, the laws on divorce and separation were determined by one’s religion. In any case, even where divorce laws existed, as in Britain after a key reform in 1857 (the Matrimonial Causes Act), it remained expensive and legally difficult to end a marriage, meaning that marriages that did break down often did so under the radar.

Although marriage and divorce, as well as other aspects of family law, came increasingly within the remit of the state over the course of the nineteenth century, the impact of the law within the household was limited. Ideas about the rule of the husband and father, and of parents more generally, meant that the law often turned a blind eye to abuse, whether physical, emotional or financial. For example, the English social reformer Caroline Norton’s husband took custody of her three children and barred her from seeing them after she left him in 1836. It was his legal right to retain custody, though she campaigned and eventually succeeded in the enactment of the Infant Custody Bill in 1839, which allowed mothers to keep their children. Divorces like Norton’s moreover reveal the double standard applied to husbands and wives: whereas the laws of many European countries allowed husbands to divorce on grounds of adultery alone, women were usually required to prove not only adultery but some other forms of abuse as well such as living bigamously or committing incest.

Uneven power relations in the household also meant that financial decisions, the holding of marital property, and decisions about children were usually in the hands of husbands and fathers. The concerted efforts of various individuals like Norton, the Swedish reformer Ellen Key and the German reformer Helene Stocker, as well as women’s rights groups like the Belgian League for the Rights of Women (1893) and the German League for the Protection of Mothers (1904), meant that many of these practices of patriarchy came into question or were reformed. In the name of ‘maternalism’—defined by historian Ann Taylor Allen as “the exaltation of motherhood as the woman citizen’s most important right and duty”—married women rallied together to call for rights to manage their own finances, to choose whether or not to work, and to have a say, for example, in the education of their children.

Emotional, Cultural and Moral Dynamics

Changing patterns of family relations affected the expectations that people had of different family members. While the presence of servants continued to be the norm in well-off European families throughout the nineteenth century (with demand in the cities met by massive female migration from rural areas), the definition of family began to narrow in scope, to the ties of blood and affection; service, meanwhile, was redefined with an increasing stress on economic, contractual aspects, particularly in the case of male servants. European societies came to perceive a manifest emotional preference for one of the children (mostly, but not always, the oldest son) as unjust and undesirable, while the stress on gender differences among children did not diminish, but rather grew due to a growing emphasis on formal education for boys. More intense care became expected from mothers, who were now supposed to oversee their children’s care, upbringing and education. Previously, these tasks had often been performed by nannies, older siblings, or elderly female relatives, while the poorer mothers worked and the wealthier ones socialised. Indeed in many countries, from Spain and Austria-Hungary to the Ottoman Empire, supporters of women’s education stressed the requirements of motherhood to defend their stance. Childrearing, however, was not their only argument: the ideal of companionship in marriage was another key point.

Even in the countries where polygamy existed, the ideal of marriage came to revolve around the notion of a couple that married for love and a woman who submitted—of her own free will and not because of the law—to her husband’s authority and guidance. Novels, poems, operas and plays helped spread this idea and render it desirable to people in Europe and far beyond. Young men became critics of sexual segregation and forced or arranged marriages, and defended the education of women not only from a political, philosophical, or patriotic stance, but also because they learnt to expect and long for a companion in their wife. While this new ideal of marriage insisted on emotional and intellectual intimacy and joint activities, it continued to be a hierarchical one, with the husband in charge of supervising and guiding the wife. The gendered division of tasks between the couple often increased, as productive and political activities moved from households to public spaces.

Political discourses heavily shaped attitudes to the family as well: particularly in the regions where stateless nationalist movements, like the Basque or the Czech ones, emerged, the home was not to be an apolitical haven, but a place of patriotic education and sociability. Moreover, pro-natalist discourses and policies strove to actively shape family size and lifestyles as well as opinions and legislation on the suitable age for marriage, the upbringing of the children and parenting. Not only public institutions intervened in this debate, but also legal and medical professionals, charities, social movements (such as feminism), and political movements and parties.

Historical research, especially the critical views of twentieth-century theorists like Michel Foucault and Judith Butler, has challenged previous assumptions about nineteenth-century sexual behaviour, such as the notion that the Victorians were extremely prudish and repressed their sexual desires. Foucault refused the so-called ’repressive hypothesis’ that the nineteenth-century was asexual and that sex was not even mentioned in public. In fact, he suggested that just the opposite was the case: sexual behaviour was widely discussed in legal, medical, and religious texts.

Behind the proliferation of discourse on issues related to sex and sexual attitudes, one can identify new social developments all over Europe. One of the most important factors in social change was the immense growth of the urban population. The resulting social mixing meant not only a statistical increase in population size, but also the emergence of new relations, novel urban social figures, and identities. As cultural historian Judith Walkowitz explored in her treatise on the narratives of sexual danger in Victorian London, the big city—the metropolis—was constructed in contemporary literary texts as a “seductive labyrinth”, a powerful and dark monster. Contemporaries referred to the metropolis as a modern Babylon, where many lives were broken and where young men and women were trapped.

Although we have no idea of the exact numbers, prostitution—or, as it was labelled by contemporaries, the ‘Great Social Evil’—grew radically within European urban environments. In the nineteenth century prostitution in its various forms was considered one of the major social problems. Politicians, doctors, journalists, and other intellectuals were preoccupied with the figure of the prostitute, her role in the spread of the dangerous venereal disease syphilis, and the moral threat that prostitutes supposedly embodied for European societies. The prostitute, the ‘fallen woman’, undermined the moral well-being of the middle class and the ‘nation’. She thus represented the opposite of the contemporary female ideal of the ’innocent virgin’ and of values such as chastity and grace.

In the nineteenth century, the word ‘prostitution’ referred not only to women who sold their bodies for sexual services (as the term is used today) but was also used to describe women who lived with men outside of marriage, or who gave birth to ‘illegitimate’ children. Moreover, only men were considered to experience sexual pleasure, while women who maintained a relationship for their own delight and happiness earned a bad reputation for themselves. Various forms of prostitution existed, including serving in brothels, streetwalking, or being a ‘kept woman’. Authorities constantly monitored prostitutes and prosecuted illegal forms of prostitution. As the case of prostitution shows, differences between urban and rural areas as well as between social classes were decisive for how differences of gender played out in the sexual culture of the nineteenth century.

Conclusion

The nineteenth century stands out as a period of major transformations in family dynamics. First and foremost, households ceased to be the main centres of production. A symbolic separation between public and private spaces took place, situating household and family firmly in the latter, while political and productive activities shifted to outside of the household. At the same time, family became a truly public issue, as revolutionaries, social reformers, and moralists from across the political spectrum argued that the state of the family was intrinsically linked to the state of the nation. Furthermore, the rise of the individual as a cornerstone of modern subjectivity led to a redefinition of the ideal family. According to most nineteenth-century Europeans, the authority of the father and the husband was to be preserved and exercised—but it should be based on love and persuasion, not on violence or the threat of it. In any case, adult sons were to be respected as fully autonomous individuals who could decide freely on their marriage and profession. The notion of marriage, in particular, shifted towards a union of feelings, in which the wife submitted to the husband’s leadership and loving guidance—though the law took care to reaffirm male authority within the couple. Nonetheless, the nineteenth century also witnessed more dramatic ruptures within the hierarchical family and the development of ideas about equalitarian marriage, free love, and alternative spaces for child-rearing. At the same time, public authorities and civil society intervened ever more frequently into family life, with justifications ranging from the well-being of helpless children to the social responsibility of fathers and mothers.

Household and Family in Contemporary History (ca. 1900–2000)

By Dr. Sarah Carmichael

Assistant Professor of Social and Economic History

Utrecht University

By Dr. Julia Moses

Assistant Professor and Reader in Modern History

University of Sheffield

By Dr. Ángela Pérez del Puerto

Professor of Contemporary History

Universidad Autónoma de Madrid

By Dr. Florence Tamagne

Professor of History

Université de Lille

Overview

The last century and a quarter have seen sweeping changes in how people organise their household and family life. From the emergence of private day care facilities to the establishment of general pension schemes, from rising divorce rates to far higher life expectancies (meaning that couples who stay together can expect to spend many more years in each other’s company), households and families are very different now compared to those of our great-grandparents. Many of the services previously provided within a household (most significantly childcare) have been outsourced to organisations outside of the household, changing the roles of parents and relatives in the raising of future generations. Significant differences exist in how these changes have taken place across Europe.

Another major change in households is that couples now live together for long periods without marrying, or never marry but have children and live together without the formal status of marriage. Many more households than ever before consist of single individuals who live alone for much or all of their life-course or who create blended households unrelated to formal family ties. Divorce and remarriage have also meant that many children grow up with siblings originally born in other families and to whom they may not be biologically related. Although such blended families existed in the past, generally due to the death of one parent, they are now far more frequent and may mean that children are part of two households. The ramifications of these changes are far-ranging for adults too, and often gendered in their outcome. Multiple studies show that divorce is often detrimental to a woman’s economic position, but that men are in many cases actually financially better off after a divorce. Parts of this chapter therefore focus on the female position in this story, as it is often women who are most affected by changes to household and family, having long been officially and unofficially the centre of these two societal units (especially during the nineteenth century). However, it is also important to note that with the growing visibility of LGBTQ+ individuals, gender roles tied to a male/female binary are in flux and contemporary households may well be centred on different roles and definitions. The changes to household and family thus took place in many dimensions. In this chapter we discuss shifts in the division between public and private realms, in marriage and family law, and in relation to sexuality.

Public versus Private

The twentieth century saw a clear redefinition of the boundaries between what was public and what was private, and women opened many doors which had previously been closed. On their non-linear journeys between public and private, some women left their homes for public professions from which they had previously been barred, others remained or returned to the private sphere but questioned the impositions within it, and others experienced the difficulty of reconciling both options. Women had long been involved with the labour market (especially during the Industrial Revolution) but this period saw further, massive increases in the degree to which women worked for wages.

The new century saw the continuation of the struggle for suffrage, a mobilisation that brought together women from different backgrounds to fight for their citizenship. The ‘woman question’ became a topic that dominated public debates and exposed for many housewives the social and legal bases of discrimination against their gender. Very different kinds of feminism represented women in the home and in the factory, but the movement suffered significant setbacks with the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. During the war, female participation was key to the defence of the nation, whether it meant safeguarding the family structure at home or working in factories to replace men who now fought at the front. Women and their labour were required in the arms sector, in agriculture, in banks, and so on. In addition, many participated in the war as nurses, even at the frontlines of battle. As a result, the work of women, inside and outside the home, was essential for the war effort. At the same time this called into question arguments that had been used in the past to justify their social and legal discrimination.

Female participation in the war effort, following years of struggle for suffrage, precipitated women’s securing of the right to vote in many countries in the 1920s, though this proceeded in parallel with the reinstatement of earlier discourses of female domesticity. Once their patriotic work was accomplished, women were effectively told to return home to make way for men returning from the front. However, many women used their experiences to question this and to challenge the biological determinism that had until then justified their limited access to certain jobs or social functions. The rise of fascism, though, led to the strong imposition of a patriarchal model in which women were above all mothers and wives. With no time to heal the wounds of the First World War, another conflict broke out in 1939, and women were again incorporated into the tasks that men at the front left vacant. They also re-experienced, like a déjà vu, the contradiction of public policies when, as war came to a close in 1945, governments once again asked them to return to the home as their supposedly ‘natural’ place. The post-war home was a mechanised one, presenting the modern housewife as a fulfilled woman surrounded by washing machines and stoves. However, many women had embarked on a one-way journey out of the domestic sphere, pursuing higher education and positions of ever greater specialisation. This situation strengthened the second feminist wave in the 1960s, which emphasised cultural challenges and the weight of gender constructions. This gave all women the opportunity to question their own assumptions about their supposedly ‘natural’ limitations.

This path led to an unrelenting rise in the access of women to the world of non-domestic work, but at the same time it revealed certain challenges that remained unresolved even at the end of the century. In particular, the ‘double burden’ of balancing professional and personal life has made it hard to reconcile a maternal desire with work aspirations. Thus there continues to be a very clear dividing line between those who opt for the domestic sphere and those who choose the public sphere.

Marriage and Family Law

The twentieth century witnessed competing movements of liberalisation and reaction in terms of marriage and family law that roughly mirrored the waves of revolution, war and the growth of new ideologies across the continent. Prior to the First World War, a number of countries experienced a push to democratise divorce and improve the rights of women within and beyond marriage, and the results of these movements continued into the interwar era. For example, in Britain, women were unable to hold property in their own names upon marriage until 1870, and it took several reforms, up until 1926, for married women to have the same rights to own and dispose of property as men. Similarly, divorce was uncommon and expensive prior to the First World War. It took a number of legal reforms to make it more accessible, including laws in 1923 and 1937 that first allowed women to end their marriages if their husbands committed adultery and also enabled partners to split on grounds including cruelty, desertion, and insanity.

Both World Wars, alongside the prolonged period of economic decline between them, generated reactions against the growing role of women outside the home, and more generally against the supposed breakdown of what many perceived as the traditional family. This movement cut across the political spectrum and across the continent, from liberal Britain to fascist Italy and Germany as well as the Soviet Union. One impetus for the movement to uphold this ideal of the family was the fact that so many marriages had broken down during the war through abandonment, separation, or death on the battlefield. For example, in Germany, the marriage rate almost halved between 1913 and 1916. In the interwar period, a number of different measures around Europe encouraged families to have more children, and women to stay at home. These included ‘marriage bars’ that prevented married women from taking up certain jobs (such as working for the post office), and family allowances or even prizes to encourage women to have more children. Fascist Italy famously introduced a ‘bachelor tax’ to encourage men to settle down and start families. Even in the Soviet Union, which had initially sought equality for women and innovation in the sphere of the family, later constitutional changes meant that women were encouraged to prioritise their roles as wives and mothers.

Some of the movements to preserve the family during this period did not, however, aim to preserve the old order but rather to forge a new, supposedly ‘purer’ order. For example, National Socialist Germany banned intermarriage between Jews and non-Jews in 1935. Germany was not unique in adopting racial and eugenic family policies. Sweden, too, for example, introduced laws that banned ‘undesirable’ individuals, such as the disabled, from marrying and having children, while Switzerland separated parents and children within the partly nomadic Yenish population between 1926 and 1973, in an attempt to force this minority group to assimilate.

Progressive campaigns related to marriage and family law nonetheless continued in parallel with movements that sought to preserve what was seen as the traditional family. This could be seen, for example, in the international arena, where a woman’s right to retain her own citizenship upon marriage was fought out in the interwar period. Eventually, countries like Britain, France and Germany changed the law so that women could maintain this essential aspect of autonomy in cases of intermarriage. International bodies and conventions in the interwar and post-1945 period, such as the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (1979), continued to call for greater rights for women to choose whether and whom to marry, and also for rights within marriage, such as the right to retain a professional life and to be educated. They also outlined universal rights for children, regardless of their family of origin, as in the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child.

In fact, the period after 1945 continued to be characterised by the tension between conservatism around the family and calls for loosening restrictions—on women as well as on different sexual practices. This could be seen, for example, in the movement for no-fault divorce that took off across Europe (from the late 1960s), as well as ongoing changes to women’s rights to property and inheritance (as was the case in France into the 1980s), and women’s equal rights within marriage (introduced in West Germany, for example, as late as 1977). It could also be seen in the outlawing of marital rape across much of Europe in the last quarter of the twentieth century (as was the case in Italy in 1976 and in England and Wales only in 1991).

Some of the most significant shifts in family law came in the 1990s and 2000s, with legislation creating civil partnerships and same-sex marriage. Europe has since continued to witness significant legal changes, including the expansion of adoption and pension rights for civil partners and same-sex couples, new rights for cohabitees, and recognition of transgender individuals. Indeed, the many shifts in marriage and family law described above were part of a broader story, in which questions of sexuality (including sexual rights, women’s rights and the treatment of children) were intimately intertwined, as we shall see in the following section.

Sexuality in Europe in the Twentieth and Twenty-first Centuries

For much of the twentieth century (and especially its first half), sexuality was still understood as the privilege of married couples that were procreative, heterosexual, and monogamous. Nevertheless, by the 1960s, a kind of sexual liberation (sometimes described in terms of a ‘sexual revolution’, although it was the result of a long-term shift) had taken hold within a context of growing secularisation and the affirmation of feminist and LGBTQ+ rights.

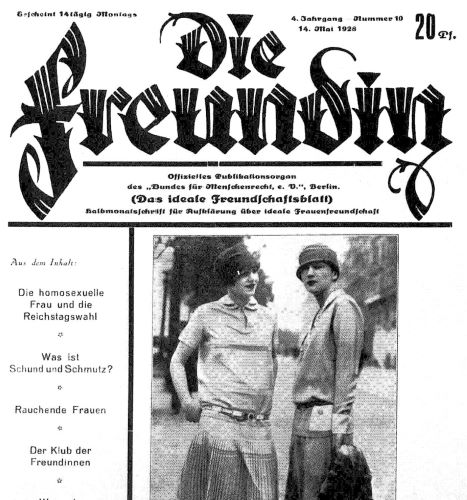

At the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries, anarchist and socialist thinkers (from Charles Fourier in France to Alexandra Kollontaï in Russia) had already begun to question the traditional family and advocating gender equality, free union and sometimes sexual freedom. In the 1920s, psychoanalysts such as Sigmund Freud and Wilhelm Reich denounced sexual repression as a source of neuroses, while the World League for Sexual Reform (1928–1932) and others promoted birth control, the prevention of prostitution, and the decriminalisation of homosexuality. Although some countries, such as France, had already decriminalised sodomy as early as 1791, others created new penalties for sexual relations between men (though rarely for those between women), as in Britain’s Criminal Law Amendment Act (1885) and Germany’s Paragraph 175 (1871). From 1897 onwards, homosexual movements, such as the Scientific Humanitarian Committee from Magnus Hirschfeld in Germany, fought for their rights.

Hitler’s rise to power put an end to this first wave of emancipation. Although the Nazi regime encouraged sexual relationships outside marriage (as long as they contributed to the pro-birth policy), it forbade interracial relationships and sent men accused of homosexuality (‘Pink Triangles’) to concentration camps. In 1934, Stalin’s Soviet Union re-criminalised both homosexuality and abortion, which had been legalised in 1917 and 1920 respectively.

After the Second World War, many European countries—whether they were governed by Christian democrats or by communists—sought to restore supposedly ‘traditional’ gender and sexual norms. It was not until the 1960s that this model began to be challenged openly, by both the scientific field of sexology (the publication of the Kinsey Reports on human sexual behaviour, 1948–1953) and the movements associated with 1968 (including so-called ‘counterculture’). Over time, sex education became mandatory in schools (as in Sweden in 1955), censorship generally lost ground (leading to a rise in pornography), and sexuality came to be seen as a fundamentally political question.

Birth control and abortion were among the main demands of second-wave feminist movements, which had been notably influenced by Simone de Beauvoir’s essay The Second Sex (1949). Even though birth control in the form of ‘the pill’ (first trialled in 1956) gradually liberated women from the fear of unwanted pregnancies, abortion rights were often only granted after years of struggle in different countries across Europe (as early as 1967 in Britain and as late as 2018 in Ireland). Poland, which had authorised abortion in 1956 (following the example of the USSR), has since drastically limited its use, introducing stringent legislation since 2016 to essentially outlaw it in nearly all cases. Since the 1990s, Assisted Reproductive Technology that was developed to tackle infertility has become a subject of public debate, especially when same-sex couples are concerned.

In fact, achieving visibility and the recognition of rights for LGBTQ+ persons has been one of the biggest challenges for European societies of the last fifty years. Following the United States, European countries saw the rise of revolutionary movements for gay and lesbian liberation in the 1970s, which began coming out of the closet, advocating gay pride, and demanding LGBT rights. In Western Europe, states began decriminalising same-sex relations between consenting adults at the end of the 1960s (Britain in 1967 and West Germany in 1969 for instance), although laws on age of consent continued to penalise homosexual relations more than heterosexual relations for much longer (until 1982 in France and until 1994 in united Germany). In Central and Eastern Europe it was generally only in the 1990s that homosexuality was decriminalised, often under the pressure from the European Union. Strong opposition remains in countries such as Poland where, although homosexuality has not been a crime since 1932, local governments have since 2019 started declaring themselves as “LGBT-free zones”. When the LGBT community was struck by AIDS, new demands emerged in favour of recognising same-sex relationships through civil unions (the first of which were established in Denmark in 1989) and, later, same-sex marriage (starting with the Netherlands in 2001). The World Health Organization ceased to regard homosexuality as a mental disease in 1990, and did the same for trans identity in 2019. Even though some European countries today acknowledge non-binary gender identities, facilitate the changing of one’s legal gender, and support transgender rights, transgender people still suffer numerous legal and social discriminations, and often see their identity negated or questioned, even in LGB and feminist circles.

The outcomes of the sexual revolution remain controversial. In the 1970s, some feminists worried that sexual freedom would only prove profitable for men. The quest for sexual gratification generated new fears related to sexual performance (or at least new markets, as demonstrated by the authorisation of Viagra in 1998). Although many countries strengthened their laws regarding sexual assault, sexual and gender-based violence is still a massive issue (as shown by the #MeToo movement). Prostitution remains a divisive topic, with countries such as the Netherlands, Switzerland, or Germany regulating red-light districts (while at the same time condemning sex trafficking), and others like Sweden making it illegal to buy sex (1999). Child sexual abuse, for a long time a taboo subject, has been a topic of concern following several high-profile media cases, some of them directly involving the Catholic Church.

Conclusion

This chapter has shown that understandings of household and family remained in flux in the contemporary period. Large changes were—and still are—underway, with wide-ranging implications for society as a whole, as households and families have become ever more fluid. While we know that many families in earlier periods also did not conform to the two-parent norm, personal choice is now a much greater factor than in previous centuries (when death and abandonment were the main drivers of diversions from the nuclear family). Households and family influence how the rest of society is organised, but they have also been reshaped by changes in the wider world. The emancipation of women, the growing recognition of sexual rights/freedoms, and the burgeoning recognition of the LGBTQ+ community in the twentieth century had profound impacts on how households and families were defined and how they continue to operate.

Suggested Reading

- Aldrich, Robert, ed., Gay Life and Culture: A World History (London: Thames & Hudson, 2006).

- Allen, Ann Taylor, Feminism and Motherhood in Western Europe, 1890–1970: The Maternal Dilemma (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan 2005).

- Davidoff, Leonore, et al., The Family Story: Blood, Contract and Intimacy, 1830–1960 (London: Longman, 1999).

- Filippini, Nadia Maria, Pregnancy, Delivery, Childbirth: A Gender and Cultural History from Antiquity to the Test Tube in Europe (New York: Routledge, 2020).

- Hamling, Tara and Catherine Richardson, A Day at Home in Early Modern England: Material Culture and Domestic Life, 1500–1700 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2017).

- Herzog, Dagmar, Sexuality in Europe: A Twentieth Century History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011).

- Humphries, Jane, Childhood and Child Labour in the British Industrial Revolution (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010).

- Kertzer, David I. and Marzio Barbagli, Family Life in the Long Nineteenth Century, 1789–1913 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002).

- Kertzer, David I. and Marzio Barbagli, Family Life in the Twentieth Century (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2003).

- Mason, Michael, The Making of Victorian Sexuality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

- Maynes, Mary Jo and Annhttps://amzn.to/3xtOjLy Beth Waltner, The Family: A World History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- Montenach, Anne, Espaces et pratiques du commerce alimentaire à Lyon au XVIIe siècle: L’économie du quotidien (Grenoble: Presses Universitaires de Grenoble, 2009).

- Perrot, Michel, ed., A History of Private Life, IV: From the Fires of Revolution to the Great War (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1990).

- Sarti, Raffaella, Europe at Home: Family and Material Culture, 1500–1800 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2002).

- Steinberg, Sylvie, ed., Une histoire des sexualités (Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 2018).

- Szołtysek, Mikołaj, Bartosz Ogórek and Siegfried Gruber, ‘Global and Local Correlations of Hajnal’s Household Formation Markers in Historical Europe: A Cautionary Tale’, Population Studies 75:1 (2020), 67–89.

- Therborn, Göran, Between Sex and Power: Family in the World, 1900–2000 (London: Routledge, 2004).

- van Zanden, Jan Luiten, Tine de Moor and Sarah Carmichael, Capital Women: The European Marriage Pattern, Female Empowerment and Economic Development in Western Europe 1300–1800 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019).

- Walkowitz, Judith R., City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1992).

Chapter 2.3: Household and Family, from The European Experience: A Multi-Perspective History of Modern Europe, 1500–2000, published by Open Book Publishers (02.06.2023) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license.