During the later Middle Ages considerable numbers of pilgrims travelled to Jerusalem each year, and hundreds of pilgrimage accounts remain.

By Dr. Marianne Ritsema van Eck

Assitant Professor of Medieval History

University of Amsterdam

Abstract

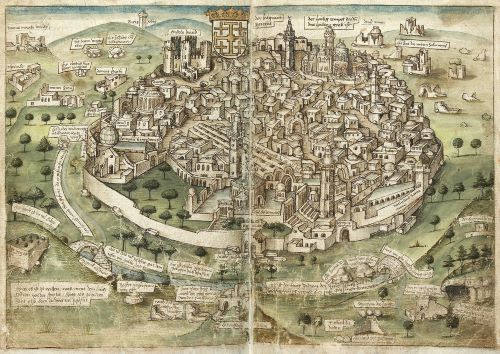

The late medieval illustrated Jerusalem travelogue by the Franciscan friar Paul Walther von Guglingen has heretofore received scant scholarly attention, perhaps owing to the unusual nature of some of its images. Guglingen charts decidedly Islamic spaces with his maps and plan, instead of the conventional sacred shrines of Christianity; these topographical features are interlaced with personal travelling experiences. Illustrations of flora and fauna encountered along the way are the result of careful observation, and meticulous recording. The author experiments with forms to visually represent his own lived experience. In all cases, text and image are closely intertwined and testify that non-religious aspects form a legitimate aspect of this pilgrimage account. Consideration of the illustrations in Guglingen’s Itinerarium, alongside, for example, those in the travelogue of his famous travel companion Bernhard von Breydenbach, allows us to illuminate more facets of the late medieval pilgrimage experience.

Introduction

During the later Middle Ages considerable numbers of pilgrims travelled to Jerusalem each year, and hundreds of pilgrimage accounts describing this experience have come down to us.1 While the holy pilgrimage is the main subject of these accounts, they also reflect wider developments in travel literature at the time. In the words of Jaś Elsner and Joan-Pau Rubiés, this period witnessed “the ultimate relocation of the paradigm of travel from the ideal of pilgrimage to those of empirical curiosity and practical science”.2 While the surviving illustrated Jerusalem travelogues are far outnumbered by those without illustrations, they offer remarkable insights on this development, portraying ethnographical, zoological and herbological subjects, as well as depictions of Christian pilgrimage sanctuaries. The illustrated accounts associated with pilgrims such as Bernhard von Breydenbach, Arnold von Harff, Konrad Grünemberg and Niccolò da Poggibonsi have attracted some scholarly attention.3

This article focuses on the illustrations in Paul Walther von Guglingen’s Jerusalem travelogue, which have received relatively little attention. Guglingen’s account not only portrays flora and fauna, but also offers visual renderings of Islamic spaces and buildings, rather than the Christian ones more commonly depicted in this type of account. The two maps and a plan contained in Guglingen’s travelogue were schematically rendered in Matthias Sollweck’s 1892 edition.4 However, although Andres Betschart does refer to these images in the appendix to his study of illustrated Jerusalem travelogues, they have not been analysed and some of the locations they portray were misidentified.5 The lack of attention for these maps so far may be connected to their exceptional nature: they are quite different from the maps, plans and city views commonly found in late medieval Jerusalem travelogues. Although Frederike Timm briefly mentions the existence of the depictions of animals and plants in Guglingen’s travelogue, these have remained uninvestigated so far.6

The maps and illustrations in Guglingen’s travelogue certainly warrant our attention because they involve a greater degree of empirical curiosity than that expressed by zoological and herbological subjects in contemporaneous illustrated accounts. Guglingen’s illustrations of flora and fauna are based first and foremost on his own acute observation of the natural specimens, which is quite unusual for the genre. Likewise, the maps and plan embedded within his Jerusalem travelogue represent a distinctly personal gaze: Guglingen exclusively charts what he experienced as impressive personal encounters with non-Christian sanctuaries, instead of the Christian shrines he visited as a pilgrim. Moreover, these topographic features are of considerable interest in themselves: they include an exceptional graphic itinerary map, a unique plan of the newly built Ashrafiyya madrasa, as well as a map of Hebron with a plan of the Ibrāhīmī mosque.

These maps, the plan and illustrations demonstrate that, even for a very devout Observant Franciscan friar travelling in the last decades of the fifteenth century, illustrating a Jerusalem travelogue could involve mainly secular subjects.7 Guglingen’s illustrations reflect exceptional attention for representing personally observed experience, as well as empirical curiosity for the natural and cultural world of the Levant. The relatively prominent place of curiosity about both these things in late medieval pilgrimage literature has long been acknowledged by several scholars.8 However, this has often been interpreted as a sign foretelling the demise of devout medieval pilgrimage as a form of travel, which was losing its legitimacy in favour of curiosity-driven Early Modern travel, perhaps most influentially by Justin Stagl.9 Based on Guglingen’s illustrations, this article argues against the idea that curious, rather than devout, engagement with one’s surroundings would be a delegitimizing force for late medieval pilgrimage. These eye-catching illustrations of the natural world, as well as the maps, most certainly represent a legitimate part of his pilgrimage experience, as do the ostensibly religious aspects of Guglingen’s verbal account of his pilgrimage. In order to substantiate this point, the author and his manuscript will first be introduced, the six illustrations depicting flora and fauna in the travelogue that have been absent from scholarship will be analysed, and finally the two maps and the plan are examined.

The Author and the Manuscript

Most of what we know about Guglingen comes from his own travelogue, although he is also mentioned by a few fellow pilgrims: Felix Fabri, Joos van Ghistele and Bernhard von Breydenbach.10 At the beginning of his pilgrimage account Guglingen offers a short autobiography.11 On 28 August 1481, aged 59, he departed from his convent in Heidelberg.12 Together with his companion, friar Johannes Wild, he made the journey to Italy on foot, hiking from convent to convent, and then departed from Venice by boat. They disembarked at Jaffa on 14 July 1482.13 After visiting the Holy Places as a pilgrim, Guglingen asked Paul of Caneto, the guardian of the Franciscan convent at Mount Zion, for permission to enter the convent.14

After having spent almost a year as a friar of the Franciscan custodia terrae sanctae, by the end of June 1483, Guglingen was asked by Paul of Caneto to leave for Europe again to deliver a document to the papal curia in Rome.15 Shortly afterwards, on 13 July a large company of German pilgrims arrived; among the members of this company Guglingen first mentions Bernhard von Breydenbach, and last but not least Felix Fabri.16 Bernhard von Breydenbach invited Guglingen to join their party on their route to St Catherine’s shrine in Egypt.17 Thus, travelling via Egypt, Guglingen finally delivered his missive to Rome on 10 February 1484.18 Here the travelogue ends; however, we know he travelled farther to northern Europe, holding various offices within the Franciscan order, finally serving as confessor of the Poor Claires of Söflingen, until he died at Ulm in 1496.19

In his travelogue, Guglingen relates events in chronological order and keeps a very precise record of time, giving the date and often the time of the day for each event. This suggests that he must have kept a diary during his travels, into which he also copied important documents; these are often recorded in the travelogue. Based on these very precise notes, he must have then composed the travelogue upon return, for it is written in retrospect. The travelogue is preserved in a single paper manuscript kept at the Staatlichen Bibliothek in Neuburg and der Donau.20 It measures 220 mm x 315 mm and is written by a single hand throughout in a cursive gothic minuscule, 45 to 50 un-ruled lines per page. The manuscript is bound between woodblocks and leather; the binding appears to be modern. At the bottom corner of the page the paper has been worn away, apparently by frequent turning of the pages. The manuscript does not have original folio numbers, but a modern pagination in pencil does exist throughout. There are 396 pages, of which the travelogue takes up 122, and the subsequent treatise on the Holy Land, also authored by Guglingen, occupies the remaining 274.21 The provenance of the manuscript is not known prior to the moment that Sollweck discovered it in the library of the study seminary at Neuburg.22

The manuscript should be dated to the end of the fifteenth century, which is in keeping with its script.23 It cannot have been written prior to Guglingen’s return home in 1484, and may well have been written by his own hand before his death in 1496. This is supported by a number of features of the manuscript that suggest it may be a first draft of the text: it has a varying number of un-ruled lines per page, and it is written in cursive script. Moreover, the text of the travelogue is fairly unstructured: its layout betrays little planning or standardization: there are only five rubricated section headings in 122 pages of text, only two of which head significant sections of the text.24 The collation of the quires of the Neuburg manuscript, as well as cross-referencing between the travelogue and the treatise on the Holy Land, indicate that the manuscript was planned as a whole, combining the travelogue and the treatise.25

Already in 1491, Nikolaus Glassberger, contemporaneous chronicler of the Franciscan order, referred to a now-lost version of Guglingen’s treatise, which was more elaborate than the one found in the Neuburg manuscript. Moreover, Glassberger reports that this expanded version was written for a noble patron, which presupposes a much more formal redaction of the text than can be found in the Neuburg manuscript, which appears like an informal draft.26 Accordingly, both the travelogue and the treatise found in the Neuburg manuscript were most likely written down some time before 1491. This dates the production of the Neuburg manuscript to Guglingen’s own lifetime, making it very likely to be an autograph. This has bearing on another important feature of the manuscript, namely that the nine illustrations closely embedded in the text of the travelogue were executed with the same pen used to write the text. The extremely close relationship between these illustrations and the text of the travelogue strongly suggests that they were indeed conceived by Guglingen himself.

Exotic Flora and Fauna: Monsters and Trees

The six illustrations in the Neuburg manuscript testify that curious interest in the natural world of the Levant forms an intrinsic part of the pilgrimage experience Guglingen projects with his travelogue. The function of these illustrations is to clarify and complement Guglingen’s textual description of impressive phenomena he encountered along his route. The author takes pains to render the exotic intelligible and imaginable for his readers, alongside his perhaps more easily recognizable, non-illustrated, religious experiences. As a Franciscan friar, Guglingen was aware of St Bonaventure’s theology of the essentially Good Creation: elsewhere in his writings Guglingen interprets marvellous creatures as expressions of the greatness of God.27 Thus, rather than a delegitimizing (or even entirely secular) aspect, these illustrations are not a curious sidetrack, but an integral part of this pilgrimage account.

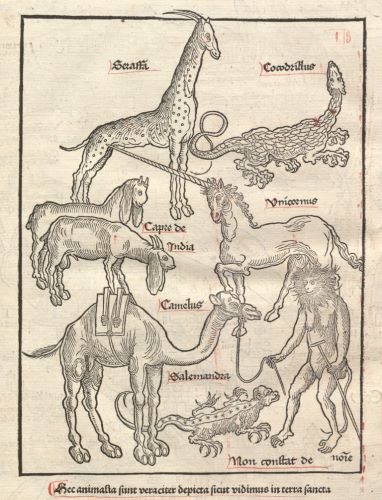

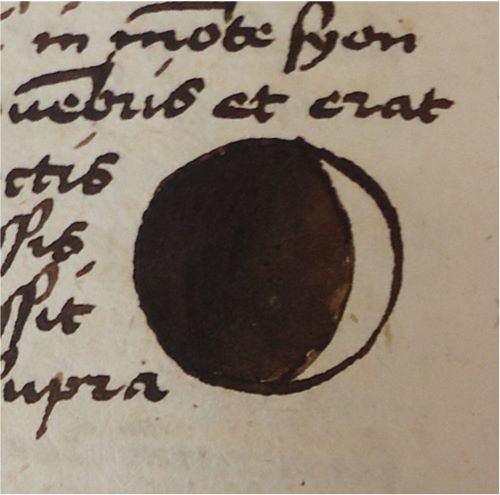

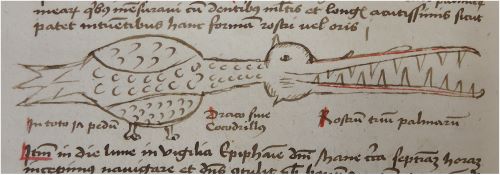

Guglingen’s illustrations are not mentioned in Sollweck’s edition of the travelogue: they include a crocodile (Figure 3), a sea monster (Figure 4), two exotic trees (Figure 5 and Figure 6), and a total and a partial lunar (Figure 2) eclipse. Unlike Guglingen’s maps and plan, these natural specimens can more easily be contextualized in the main thematic categories of images often found in late medieval Jerusalem travelogues; illustrations of exotic animals and plants are a reasonably common feature in these texts.28 What stands out about Guglingen’s illustrations is that they are based on careful empirical observation. Here we do not find depictions of (semi-)mythical creatures or material drawn from earlier visual or textual sources, but an attempt to record the natural world with care and precision. Guglingen minutely describes his subjects verbally, as well as visually, and occasionally invites his readers to carefully examine his drawings.

This approach to the flora and fauna of the Levant is remarkable within the genre of illustrated Jerusalem travelogues. This becomes clear, for example, when we compare it to the presentation of the plate with animals of the Holy Land by Reuwich in Breydenbach’s influential Peregrinatio (Figure 1).29 The caption of the plate invokes what Elizabeth Ross calls the conceit of the artist-viewer: “These animals are truthfully [veraciter] depicted as we saw them in the Holy Land.”30 However, the majority of them, including a unicorn, go back to medieval stock images, rather than eyewitness observation.31 Furthermore, the plate is found on the back of the fold-out Holy Land map, “text-external” in the words of Frederike Timm, and has a very loose relationship with the text of the travelogue; only three of the eight animals are mentioned at all.32 Conversely, Guglingen’s illustrations of flora and fauna are all embedded in the text of the travelogue, next to the portions of the text that discuss their particular subjects. Furthermore, the relationship between text and image is very close, as it was with the maps and the plan described above. The only Jerusalem travelogue that is somewhat comparable to Guglingen’s in this respect is the earliest illustrated manuscript copy of Niccolò da Poggibonsi’s Libro d’Oltramare, possibly dating back to the late fourteenth century.33 Otherwise, Guglingen’s travelogue stands quite apart from the much more formal illustrations depicting animals in Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio, copies of the travels of John Mandeville, and later printed editions of Poggibonsi’s Libro.34

Guglingen has included illustrations whenever he experienced objects or events as in some way impressive or remarkable. For example, he twice records and depicts a lunar eclipse, both of which occurred during his stay in Jerusalem. Guglingen notes the date, the time of day and describes how it occurred. The first time it concerns a partial eclipse (Figure 2) on p. 62 (17 mm in diameter), and the second time Guglingen refers his readers to the illustration of a full eclipse on p. 77 (16 mm in diameter).35 Both eclipses are shown as small circles embedded in the body of the text, partially darkened in the first case and entirely black in the second. Guglingen’s reasons for describing and depicting these lunar eclipses cannot be gauged beyond the fact that he perceived them as occurrences remarkable enough to be visualized in his diary-like travelogue.36 The remaining four illustrations of exotic fauna and flora in Guglingen’s travelogue are also inspired by impressive encounters, and are characterized by an extremely close relationship between text and image, as well as a preoccupation with careful observation and description of these specimens.

A Crocodile and a ‘Fetz’

Together with giraffes, elephants and camels, as well as a number of mythical animals, the crocodile has been a likely suspect in Jerusalem travelogues since the early days of Holy Land pilgrimage.37 In the second half of the seventh century, the Holy Land pilgrim Arculf already describes crocodiles living in the Nile.38 In late medieval Jerusalem, travelogue illustrations of crocodiles also appear.39 On his peregrinations, Guglingen too comes across a crocodile, describes it and includes a drawing of it:

Item, on that Sunday, in the evening around compline, I saw one whole, big, dead, and disembowelled dragon or crocodile, whose length with tail was a solid seventeen feet, large as a one-year-old calf, having four feet, with scales so hard that a gunshot cannot hurt him, his head is long, the mouth extending truly three hand-spans, by which I measured, with many long and very sharp teeth.40

This terse description consists of personally observed detail, supplemented with few elements from existing textual traditions.41 In the manuscript, it is immediately followed by the phrase “as it appears to those who observe this form of beak or mouth” (Figure 3).42 The illustration measures 142 mm x 33 mm, is embedded in the text of the travelogue, and renders the silhouette of a crocodile in the shape of a scaly birdlike creature with folded wings, on two legs, with a long, toothed beak. The correct number of feet is given in the caption: “in total four feet.”43 In addition, the name of the animal and the length of its snout are indicated: “dragon or crocodile / beak three hand spans.”44 The animal’s birdlike appearance may be inspired by Guglingen’s interpretation of its snout as a type of beak.45 Two dashes of rubrication highlight the snout with many long and sharp teeth as Guglingen described above. His preoccupation with the exact length of the snout is in character with his nature as a “devoted fact finder”, which is discernible throughout the travelogue.46

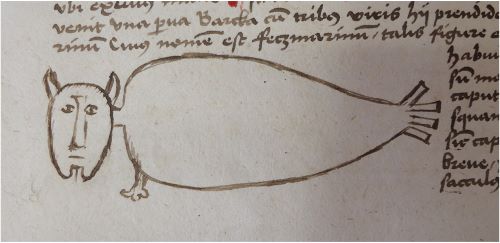

Guglingen includes another illustration of an exotic animal that is much less commonly found in illustrated Jerusalem travelogues: a sea monster he calls a “fetz” (Figure 4). Felix Fabri, member of the same company of pilgrims as Guglingen, reports to have seen the same animal and calls it “felchi”, and says they are “calves of the sea”. Sollweck suggests it might have been a sea cow, even though its habitat does not currently include the Mediterranean Sea.47 Arnold von Harff may have spotted that species in the sea by Madagascar in the late 1490s, where he reports to have seen a fight between “sea oxen” and a “sea cow” called “falchges”, and gives an illustration.48 Apart from the illustration in Von Harff’s travelogue, the illustration of the mysterious sea animal in Guglingen’s travelogue stands quite on its own. He too compares it to a calf, as well as many other things:

Item, on the second Sunday of Advent, around vespers, a small boat arrived with three men inside. They had seized a sea monster, whose name is sea fetz. [MS: of such figure and form as placed here] The aforesaid beast or sea monster has a head like a calf without scales or hair, like the head of a salmon, a short neck, the shape of the body like a sack full of water without back and ribs; it has only two flippers next to the neck, on which it has several very sharp nails. Its skin has a grey colour like ashes, its hair is very fine, its tail has no scales or fins but is fourfold. Its flesh is not eaten because of the stink, its hair is good only for a whip.49

Embedded in this section of text, the fetz is represented by an illustration measuring 97 mm x 35 mm. It features a head with humanoid facial features, two pointy ears and a goatee, a single paw-like neck flipper, and a plump, elongated body that terminates in a tail consisting of four rectangular flaps.

Both illustrations – of the crocodile and of the fetz – function as a clarification and demonstration to go along with Guglingen’s careful and detailed accounts of these unusual creatures. Like the textual descriptions, the illustrations portray the animals in terms of comparison. More well-known visual templates are adapted to render the exotic: the humanoid features of the fetz’s head and the birdlike appearance of the crocodile. Both text and image display a keenness for careful observation and meticulous record.

Trees in the Balsam Garden

The balsam garden was a regular station in the pilgrimage to Egypt and the shrine of St Catherine during the late medieval period.-50

This mode of depicting the balsam garden, which resonates with hortus conclusus iconography, is also encountered in the late Tractatus de Herbis. Collins, Medieval Herbals, 122, 253, 256–7, 266, 269; Arad, “As if You Were There”, 310–11. According to legend, the holy family rested at this location close to the village of Al-Matariyyah, on their flight into Egypt.51 On 7 October 1483, around four in the afternoon, when a dragoman arrived from Cairo, Guglingen and his fellow pilgrims entered the balsam garden. Guglingen first describes an enormous fig tree with a hollow trunk, where Mary was supposed to have placed the infant Christ.52 Next they came to another fruit tree, most likely a banana tree:

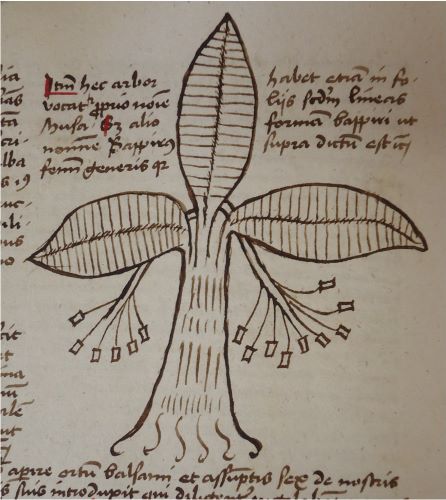

And there we found a reasonably large tree, not wooden but entirely green, which is called musa, or bappirus; they have very green leaves: eight feet long and two and a half feet broad. We secretly took the fruit, which is very sweet, like sugar, when it is ripe. And from that tree and its leaves, paper, on which we write, takes its name; because the leaves have perfect lines and when they will have been made dry, they will be white and suitable for writing.53

Following this description, a pen drawing is announced: “The form and appearance of that tree and its fruit appear clearly to those who diligently examine this tree, depicted here with a pen, etc.”54 To the right there is a drawing of the tree with a caption that indicates that it is called musa or bappirus (Figure 5).55 The illustration measures 112 mm x 104 mm, and shows a tree with three big leaves protruding from its trunk. The leaves have straight pinnate veins, and from the crown of the tree two branches slope down on either side of the trunk, splitting into several sub-branches, and ending in rectangular fruits. In the next paragraph on the manuscript page the description of this particular tree concludes with: “Item, this tree grows up from the ground in one year, and it makes very broad leaves and very sweet and medicinal fruits, and is of a most green colour as was said above, etc.”56

The function of the illustration yet again is to complement Guglingen’s verbal description of the tree, and to clarify its form and substance to the reader, as he explicitly states. He invites his readers to “diligently examine” the illustration in order to form an impression of the shape of the trunk, the leaves and their fine straight lines, as well as the position of the fruits. Although Guglingen is not the only traveller to include an illustration of a banana tree, this insistence on careful examination of the image is remarkable.57 In addition, his illustration is extraordinary because of its resemblance to an actual banana tree, which strongly suggests the image is based on personal observation; this is supported by the close relation between the image and text.

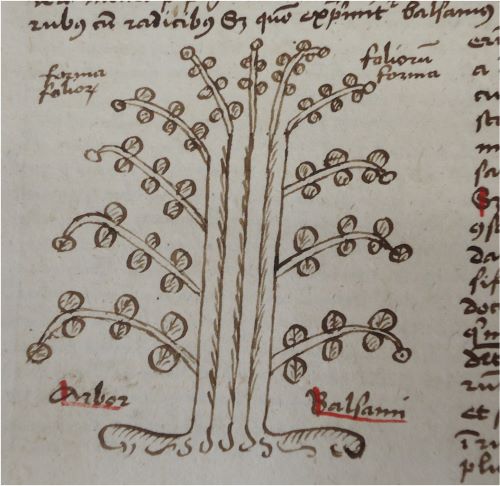

After having seen the musa tree, the pilgrims visit the balsam garden proper. In small groups of six members of the company at a time, they are led in to see the balsam trees. Guglingen writes: “The balsam tree is like some small bush, whose leaves are usually sevenfold on truly soft and fat branches, and when it is mature the balsam is extracted from the entire bush with sticks.”58 He sees the dragoman cut a branch and the balsam run out immediately. Guglingen then relates that there are three drafts of balsam, the first being the best, although this is not normally given to Christian pilgrims.59 He then refers to the illustration (Figure 6): “The form of this tree and the kind of leaves appear clearly in the bush here beside, depicted simply with a pen.”60 The illustration measures 85 mm x 86 mm and shows a bush with a thick trunk and 11 branches with rounded leaves. In this case, Guglingen wants the reader to observe the shape of the leaves in particular, as is also twice indicated in the caption: “the form of the leaves / the form of the leaves / Balsam Tree.”61 Again, the illustration serves to clarify the description of the tree, and to help the reader to imagine how it looks.

To my knowledge, Guglingen’s travelogue is the only Jerusalem pilgrimage account that includes an illustration of the balsam tree. Late medieval herbals do offer images of the tree from the late thirteenth century onwards, going back to earlier Arabic herbals, rather than naturalistic renderings.62 In this context, it seems pertinent to refer to the Gart der Gesundheit, a herbal printed in Mainz in 1485 on the initiative of Guglingen’s travel companion, Bernhard von Breydenbach, and in collaboration with, amongst others, Erhard Reuwich. In the preface, Breydenbach claims that he gathered information for this herbal on his Holy Land pilgrimage, bringing an artist along to portray these plants correctly.63 Although 77 of the 381 images of plants in the Gart were not adapted from earlier herbal depictions, and are occasionally quite true to nature, the image of the balsam tree, which Reuwich must have seen near Cairo, is based on earlier illustrative traditions. The woodcut on fol. 74v of the Gart is a rather generic depiction of a plant, with little baskets hanging from two of its branches, derivative of bottles or pots for balsam collection seen in earlier herbals (Figure 7).64 Breydenbach’s herbal project employs the conceit of the personal viewing of the Holy Land by the author-artist, whereas Guglingen’s observations are genuinely first-hand.65 He shows a keen interest in the balsam tree, continues to discuss its annual cycle of planting and harvest, and relates that it is watered from the nearby fountain of Mary:

And the Saracens say that it does not want to grow in any other place or ground except in this garden, nor does it want to be irrigated with any other water than that from the glorious fountain of Mary. Whether either of these things is true, I know not.66

Rather than being credulous of all he is told, Guglingen clearly trusts to his own careful observation more. The same goes for all of his illustrations of the natural world in his Jerusalem travelogue: they are based on direct observation and accompanied by meticulous descriptions. The goal of these illustrations is to help readers form the best possible impression of what Guglingen clearly perceived as a significant part of his travel experience. Since we know that Guglingen was wont to interpret Creation as an expression of the greatness of God, these illustrations are not a delegitimizing intrusion of irreverent curiosity on what ought to be a devout pilgrimage, but instead an intrinsic part of the same.67

A Map of Hebron and Surroundings

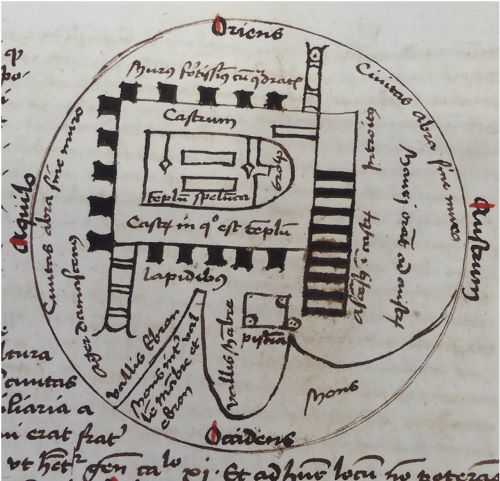

The maps and plan in the Neuburg manuscript likewise represent aspects of Guglingen’s pilgrimage experience he considered legitimate, even though they plot out Islamic rather than Christian spaces. The first map in the travelogue, which shows the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron and its surroundings, exemplifies Guglingen’s approach to mapmaking: using a clever combination of cartographic conventions as a story-telling device, to visually represent foreign spaces he was personally impressed by. This map is associated with an excursion that he made on 7–10 April 1483.68 The circular map on manuscript p. 75 measures 92 mm in diameter, has east at the top, and prominently features the plan of a fortified building, as well as the peaks of two mountains towards the west (Figure 8). The situation of valleys of Mambre and Hebron, associated with these mountains, is described by Guglingen, and his description concludes with a reference to a circular map: “as will appear more clearly to those who are observing the sphere of the situation of the city, found below.”69 However, at this point there is no map in sight; it only appears after three manuscript pages with a detailed description of Guglingen’s own stay at Hebron.70 The map then visually sums up the most important elements of that experience. Indeed, it is difficult to appreciate this map without first considering Guglingen’s personal encounter with Hebron, which is why the same approach will be adopted here.

Guglingen writes that on 7 April 1483, in the first hour after lunch, he set out from Jerusalem to go to Bethlehem, in the company of fellow friars and pilgrims. In the middle of the night, they continue from Bethlehem on the way to Hebron. This experience frightens Guglingen immensely: it is pitch dark, they can barely discern the rocky and mountainous roads, and have to be very quiet not to attract highwaymen. Then, the ass that Guglingen is riding starts to bray loudly, and the noise reverberates between the mountains, casting its rider into a state of panic. No robbers appear, however, and in the morning they continue to travel through what Guglingen identifies as the Valley of Tears, where Adam and Eve did penance in a cave for 100 years. This valley is separated by only one mountain from the Valley of Hebron; the company climb this mountain and look out on Hebron, at which point Guglingen first refers to the map.71

Upon arrival in Hebron the company first has lunch at the house of their dragoman, after which they set out to visit the Damascene field, just outside the city. The pilgrims perceive this as an important location, because it was generally believed that God had formed Adam from the soil of this particular field.72 Guglingen, impressed and humbled by this belief, takes up some soil and says a prayer.73 Then, after remarking on the thriving glassblowing industry at Hebron, Guglingen turns to discuss a square pond, which he saw in the city. He explains that at two corners of this pond Muslims come to wash their genitals, hands and feet after having sinned, and they then go to the southern corner of the pond to pray. Guglingen is disgusted when seeing a man put this custom into practice.74

Guglingen then discusses Hebron’s main monument: the Ibrāhīmī mosque in which the double cave, or duplex spelunca, is situated. In these caves the Old Testament patriarchs Adam, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and their wives were supposedly buried.75 He is impressed by the building: “This mosque is very great and powerfully walled-in with high walls like a fortress.”76 The same day the dragoman tries to find a way for the pilgrims to enter this mosque, but he returns with the news that it is not possible. Guglingen is relieved, because he has often heard it can be dangerous to enter mosques. However, the next day a number of pilgrims decide to offer money for a safe visit, and the dragoman goes to negotiate again. At this point, Guglingen becomes very anxious, and fervently prays to Christ to only allow this excursion to take place if it will not be to the detriment of their souls and bodies.77

The dragoman returns and says that for a ducat and a half a person they can enter the mosque at night, while all the lights will be extinguished: the guards have been bribed, but other visitors of the mosque should not see them. The Franciscan guardian of Mount Zion, who is among the company, exclaims that they will not enter in such a manner, after which there is much discussion within the company about how to proceed. To resolve this situation the guardian eventually appeals to Guglingen, as the most senior friar present, to give his opinion. Guglingen responds by giving a long speech, expressing the following doubts: first, if the lights of the mosque are suddenly extinguished, this will immediately create suspicion among those praying there; it is very likely the pilgrims will be apprehended and forced to convert to Islam or be killed. Moreover, they are most likely already suspected of wanting to enter the mosque because they have been walking about town all day.78 To conclude his argument, Guglingen discredits the sanctity of the site, saying he does not believe the patriarchs are buried there: this excursion is not worth a martyr’s crown.79

Convinced by this speech, the company abandon the plan, to Guglingen’s relief. The episode concludes with the phrase: “The layout of the mosque and the city appear more clearly in this circle, to those who are observing and considering single things, and the valleys of Hebron and Mambre, etc.”, next to which the map is shown on manuscript p. 75 (Figure 8).80 At the end of Guglingen’s narration of his stay at Hebron, the map provides a visual summary: it shows the arrangement of the most important elements of this episode in space, after the reader has just read it: the Ibrāhīmī mosque, the pond, the Damascene field and the valleys the company passed through on the way to Hebron.

The mosque with the cave of the patriarchs figures prominently in this map. We see its rectangular walls, marked on the map with the words “a very strong wall with battlements”, which had impressed Guglingen as strong and high.81 At two corners, the two minarets are indicated, sticking out flat to the sides. On the right hand side of the structure we see the steps leading up to the entrance, marked “ascent to the fortress” and “entrance”.82 This rendering of the outer structure corresponds roughly to the actual configuration of the building. Inside the walls, where Guglingen did not enter, the plan does not represent reality at the time.83 What looks like a courtyard is marked with the words: “fortress / fortress in which the temple is.”84 In the middle of this courtyard the shrine itself is indicated by the words “cave temple”, and rendered in the shape of a small western church with a “choir”.85 In the nave of this church plan there are two rectangles, which could possibly represent the cenotaphs of Rebecca and Isaac, or alternatively the two caves themselves.

Just below the mosque, to the west according to the orientation of the map, there is a small square structure with the caption “pond”.86 This element represents another impressive event during the episode at Hebron: the pool in which Guglingen saw a man wash himself. Semicircles at two corners inside the rectangular pond indicate where the washing occurs, while a third rounded shape that juts out towards the south represents the place where visitors of the pool would go to pray, after washing. We are reminded of this to the right-hand side of the map; in the southern direction this is indicated with the words “Muslims pray to the south”.87 The location of the first highlight of Guglingen’s stay at Hebron is indicated north of the mosque, to the left: “Damascene field.”88 The phrase “the city of Habra without wall” indicates in two places that Hebron lacks city walls.89 Finally, to the west we see the valleys of Hebron and Mambre and the peaks of two mountains: “Hebron valley / the mountain between Mambre valley and Hebron / Mambre valley / mountain”, associated with Guglingen’s unnerving nocturnal ride towards Hebron.90

Although late fifteenth-century educated Europeans were familiar with a variety of cartographic forms – Ptolemaic maps, town plans, charts and so forth – medieval maps representing small areas, such as this one, are relatively rare, and according to P.D.A. Harvey often seem to be the work of original minds, unaided by precedent or exemplar.91 Indeed, it is highly unlikely that Guglingen was inspired by an exemplar map of Hebron. He was certainly familiar, however, with the so-called T-O world map.92 Guglingen’s treatise on the Holy Land twice features a T-O world map, and it seems that he took the circular design of this type of map as a starting point for his map of Hebron and surroundings, also orienting it with east at the top.93 Into what he perceived as a conventional cartographic framework, he then inserted representations of structures and locations in and around Hebron: the mosque, the pond and the Damascene field, as well as mountains and valleys through which he travelled to the city. Apart from T-O maps, Guglingen may also have been familiar with architectural ground plans of buildings, for he shows the Ibrāhīmī mosque in plan.94 This is uncharacteristic of medieval mapping, which typically shows such objects pictorially, rather than in plan.95

Guglingen has inventively used the cartographic devices he knew, to provide the readers of his travelogue with a tool to navigate this eventful episode of his travels. He recapitulates it by supplying a visual overview of the main elements of his impressive encounter with these foreign spaces. In line with his lively and autobiographical style of writing, Guglingen’s approach to map-making involves plotting the locations associated with impressive personal experiences in space. With this map of Hebron and surroundings, he has found an ingenious way to sum up and represent his personal pilgrimage experience in the form of a map.

A Plan of the Ashrafiyya Madrasa

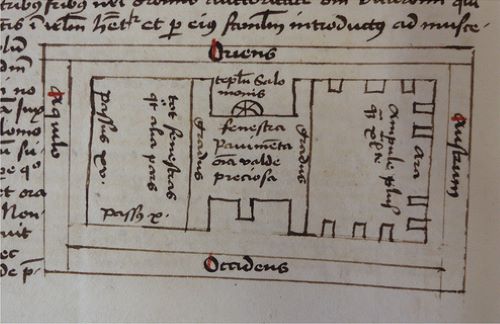

Like the map of Hebron, the next plan in the travelogue also represents a building that Guglingen interpreted as a mosque. In both cases, he underplays the possible meaning and importance these spaces might have to Christians, while nevertheless taking the effort to draft a plan. He clearly saw these topographic representations as an acceptable part of his Jerusalem travelogue, for which he felt no need to apologize. While Guglingen had argued against entering the Ibrāhīmī mosque in Hebron because of the dangers involved, he blithely entered and exuberantly admired the attractions of a madrasa on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. He saw no harm in visiting this building with three fellow friars, on 20 April 1483, around 11 o’clock, since there was no danger involved: they had explicit permission from the Mamlūk authorities to do so.96 Guglingen writes he was introduced to “a mosque, or a temple, or a chapel belonging to the Sultan”.97 In reality, it was a school recently built by Sultan Qāʾit Bāy (r. 1468–96): the today partially ruined Ashrafiyya madrasa.98 Guglingen visited the structure only one year after its completion in 1482, and he is aware of this, referring to it as “newly constructed”. He believed the Sultan lived on the ground floor of the building, while the upper floor was a mosque. It is this “mosque”, the main rooms of the madrasa that his plan represents: “The form of this mosque appears more clearly in the figure depicted above” (Figure 9).99

The plan on manuscript p. 76 represents the madrasa’s upper storey (now no longer extant), and when compared to modern reconstructions of the floor plan, it seems that Guglingen succeeded quite well at providing its general outlines.100 The plan measures 55 mm x 101 mm, including the frame around it, which holds indications of the cardinal directions: east is again at the top. Contained within this frame is the floor plan of the madrasa, which consists of a northern wing or īwān and a southern īwān, with a connecting central court, or såhn, between them. Notes in the plan express the grandeur of the madrasa; the loggia and the central court are preciously adorned: “window / floor / all very precious.”101 The south wing has “more than forty bottle-shaped lamps”, and a miḥrāb, which Guglingen interprets as an “altar”; the 10 blocks placed against the walls of this wing quite accurately indicate the position of the windows, when compared with modern reconstructions.102 Guglingen erroneously asserts that the north wing has “as many windows as other part”, and also notes in his plan that this wing is “fifteen steps” long and “ten steps” broad.103 These indications of dimension suggest Guglingen made an effort to measure the north wing, although his overall plan is not to scale. In the text of the travelogue, he also reflects on the size of the building, and confesses himself impressed by it: “This mosque is very preciously and curiously constructed with white, black, and red marble, and also porphyry in various colours, namely of green and blue, and mixed colours, various uncommon splits, which I cannot describe, neither very broad nor long, but reasonably high”; he is not afraid to praise this outstanding Mamlūk monument.104

Elizabeth Ross has argued that Reuwich captures the façade of the madrasa, just left of the Dome of the Rock on his Holy Land vista in Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio (1486) “with relative accuracy”.105 Guglingen does not represent the madrasa pictorially, but instead provides a markedly more accurate plan, as he did with the Ibrāhīmī mosque in Hebron. This confirms the impression that Guglingen was somehow acquainted with the concept of drafting floor plans of buildings, and deemed it an appropriate way to represent the building, rather than drawing its façade. The plan must have been based on Guglingen’s personal observation. This becomes clear from the accurate indication of the locations of windows in the south wing, which cannot be gleaned from the text of the travelogue, nor is it likely that a later Bavarian scribe had access to this information.

The words “Temple of Solomon” in the plan indicate that the Dome of the Rock (Qubbat al-Ṣakhrah) is situated east from the madrasa on the Temple Mount; the tag “Temple of Solomon” is placed just under the cardinal direction “east”.106 In the text of the travelogue, Guglingen also writes that the madrasa is situated “next to the temple of Solomon”.107 It is unlikely that the small rounded element below the words “temple of Solomon” is a pictogram representing the Dome of the Rock itself; more probably, it represents the octagonal lantern crowning the central court of the madrasa.108

It is pertinent to note that Guglingen provides a description and a plan of the Ashrafiyya madrasa, which he perceives as a newly built mosque, and not of the Dome of the Rock, which in his day was commonly interpreted as the Temple of Solomon by Christian pilgrims, and hence an important Christian monument.109 Yet, he uses this well-known landmark solely to make clear in his plan where the madrasa is situated, approximately. Guglingen’s choice to provide a plan of the madrasa, a building he knows to be entirely Islamic, exemplifies the complex paradigm of late medieval pilgrimage. He describes the building in terms of awe and admiration that remind more of the exclamations of a modern tourist appreciating Islamic architecture, than of a late medieval Jerusalem pilgrim on “unholy” ground. Furthermore, Guglingen clearly considers his visit to the madrasa as valid a part as any of his travelling experiences, to be put before a Western audience, providing a plan to better convey the marvels of this building to his readers. The intended audience of Guglingen’s travelogue – be it Franciscan or secular – is hard to gauge, other than that his readers needed to be versed in Latin. In any case, the author seems not to have been concerned that these topographic representations might detract from his travelogue as a pilgrimage account. As is the case with the map of Hebron, text and image work together to represent Guglingen’s impressive personal encounter with the Islamic spaces of the madrasa.

A Map of Cairo and Surroundings

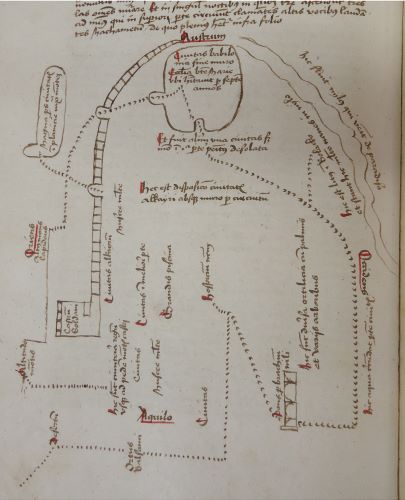

The same holds for the last map in the travelogue, which likewise – and perhaps even more so than the previous map and plan – plots personal experiences on a topographical plane. Once again, the author chose to represent Islamic monuments primarily. It is a remarkable map of Cairo and its surroundings, which charts the itinerary of Guglingen and his companions around the city on 14 October 1483 (Figure 10). This almost full-page map measures 215 mm x 190 mm, and is oriented with south at the top, which may be a result of the company’s approach to the city from the north.110 Its main organizing principle is the dotted line representing Guglingen’s route. Written tags and few symbols along the way mark sites described in the travelogue. The map is enveloped by a more general discussion of the city of Cairo, which starts on manuscript p. 102. The map itself appears on p. 104, while the description of Cairo continues on manuscript p, 105 with the words: “In this, depicted and described, city …” Then, at the bottom of p. 105, begins the account of the extensive exploration of the city of Cairo; this is the tour that the map depicts. Unlike in the case of the map of Hebron – which is placed at the end of the adventure that inspired it – this map of Cairo, although based on a personal itinerary, also serves as a more general depiction, contextualized within a broader description of the city. Nonetheless, the map portrays Cairo entirely through the lens of personal experience: text and image almost seamlessly work together in canvassing Guglingen’s tour of the city.

The travelogue and the map can be read in parallel, the dotted line tracing all the locations the company visited, in the order of the narrative. This path starts in the lower left-hand corner of the map, from the northeast; the first location that it passes is the “desert”.111 Then, representing the company’s movements on 7 October 1483, the path passes the “balsam garden”, then enters the “city” of Cairo, and leads straight up to the place where Guglingen’s company stayed: “our lodgings”.112 Here they stay 12 days, according to the main text of the travelogue, but are unable to go out much because of the hostile attitude of the local population. On 14 October, however, the company leaves for an extensive tour of the city, with the help of two formerly Christian dragomen. One of these was a German-speaking native of Basle called Sefogel, and Guglingen did his best to ride next to him so that he might question the man about the city.113 Thus, based on the expedition of 14 October, the path on the map exits “our lodgings” again, in a northwestern direction until it arrives to a “bridge over the arm of the Nile”.114 This feature is represented pictorially by a rectangular shape showing the arches of a bridge, seen from the side. In the text of the travelogue Guglingen writes: “And we began to ride north, and descended west, and we came to the shore of the Nile, where we saw many great ships from Alexandria and other parts of the world.”115

Next, the path bends south, and the text of the travelogue continues: “then we followed the Nile up-river towards the south.”116 The map indicates: “here the water encloses part of the city”, and most likely this refers to the islands in the Nile.117 In the main text of the travelogue Guglingen describes various things he saw along the way, such as a market place, and the local practice of hatching chicken eggs in ovens.118 “Then, having seen these things, we rode towards the south to the city of Babylon, which is not great Babylon, where Nimrod advised the sons of Noah to build a tower to heaven, … but Babylon minor”.119 On the map the path enters an enclosed area, under the cardinal direction “south”, this is the Babylon Fortress in Old Cairo.120

But before the path enters there, a sidetrack appears, bending off to the right towards the place on the banks of the Nile where Guglingen was to embark to leave Cairo five days later. The map indicates: “This is the shore and Bolacko, and there are many ships in the Nile.”121 The map also depicts the course of the Nile itself, denoted as “Here flows the Nile which comes from paradise”.122 Just before the path enters the Babylon Fortress, the map offers a comment on the dilapidated state of Old Cairo: “and it once was a city but now this area is almost entirely abandoned.”123 Within the walls of the fortress, the company visited a few of the many churches, including the church of St George, and the one on the spot where the holy family had stayed: Abu Sarga.124 The latter impresses Guglingen greatly, and is indicated on his map, within the walls of the fortress: “The city of Babylon or wall, the church of Mary where she lived for seven years.”125

The company leaves the Babylon Fortress by another gate than the one they entered by, as the path on the map indicates. Guglingen narrates: “Afterwards we rode out of Babylon towards the right hand and we approached a canal in a very high wall through which water of the Nile runs to the fortress of the Sultan.”126 The map shows that the company passed under the aqueduct that leads to the Citadel of Cairo, here represented on the map as a wall that leads up to a square structure marked with the words “fortress of the Sultan”.127 They rode north into the Muqattam hills, first climbing up to a “high rocky mountain”, and then to the “height of the mountain” indicated on the map.128 There the company enjoyed a vista of Cairo, and Guglingen is duly stunned:

Then we rode to the highest mountain of all, and from there we looked at the parts of the city. There, I secretly gave myself to careful consideration of the extent of the city and the multitude of mosques, and I could altogether not believe it.129

The number of mosques in Cairo is a fond subject of speculation for Guglingen.130 From the “height of the mountain” the path on the map takes a northwestern direction and terminates in the eastern medieval necropolis of Cairo, which houses the graves of the caliphs: “Here are the graves of the kings, up to the foot of the mountain of the fortress.”131

At the centre of Guglingen’s itinerary map are a number of written markers not directly associated with the depicted route. These include a tag in the middle of the map, which also supplies a title: “This is the disposition of the city of Cairo, not surrounded by a wall.”132 Further tags at the centre of the map thrice point out the presence of the city in this area, twice the presence of “many mosques”, once to a “big pond”, as well as to various vegetable gardens with palms and trees.133

All in all, there is a remarkably close affinity between the episode of Guglingen’s visit to Cairo in the text of the travelogue and its representation on the map. Text and image are highly intertwined, and together they underscore his personal experience of the city. This map, unlike that of Hebron, is not enclosed in a circular frame inspired on the T-O maps that Guglingen knew. Instead, he devised a type of map that would best express his personal experiences in and around Cairo: an itinerary map. It represents a route, a personal itinerary, linking Guglingen’s point of departure with his destination, via the places between those two. This was a highly unusual type of map during the medieval period, as itineraries most often took the form of a list of place names.134 Although Guglingen generally relies on written tags to identify locations, the map also contains a few modest pictorial elements: the bridge; the River Nile; the aqueduct; and the citadel of Cairo. Consequently, it might perhaps even be considered a graphic itinerary map, like the splendid map in the Chronica Maiora by Matthew Paris (ca. 1200–59): “the only known medieval graphic itinerary”, according to Catherine Delano-Smith.135

Guglingen’s motivations for creating such a highly unusual type of map are not directly apparent. There is no indication that the map was intended as a tool for a vicarious travel experience around Cairo, a function suggested for Matthew Paris’ map.136 Rather than an imagined pilgrimage, this map could have offered a virtual tour around predominantly (but not exclusively) Islamic monuments in and around Cairo. However, Guglingen says nothing to this effect in his travelogue, and it seems more likely that he chose the perspective of a personal route because he was keen to depict his highly individual encounter on 14 October 1483 with this foreign city, which had so deeply impressed him.

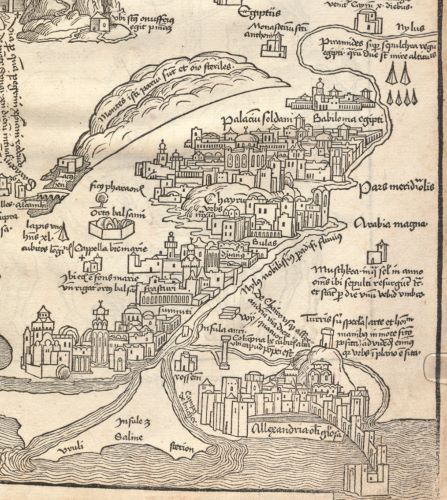

Although his approach is unconventional, Guglingen is not the only Jerusalem pilgrim to include a reasonably elaborate visual perspective on Cairo in his account: the famous view on the Holy Land in Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio in Terram Sanctam by Erhard Reuwich also includes Cairo, the balsam garden, and Babylon fortress on the right-hand-side wing of the fold-out Holy Land map (Figure 11).137

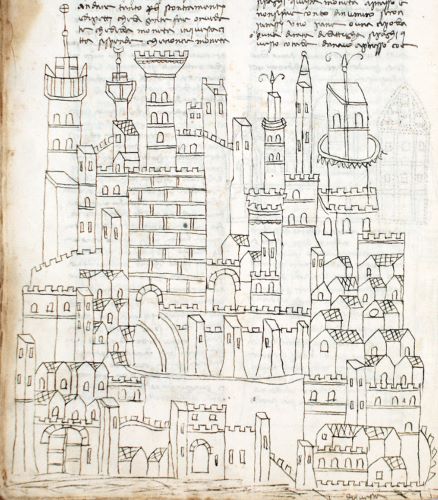

The illustrated manuscripts of the pilgrimage account of Niccolò da Poggibonsi, a Franciscan friar travelling around a century and a half earlier, also include an elaborate view of the city of Cairo (Figure 12), as do later printed editions, which are often anonymized or misattributed to Fra Noé Bianchi.138 In both cases, the city is visualized as an agglomeration of buildings and architectural elements, only some of which are particular to Cairo itself.139 Like so many non-specific medieval and early modern city views, they represent the concept of a city through a stylized portrayal of towers and buildings.140 By contrast, the organizing principle of Guglingen’s maps is a route around the city, instead of a view of it; moreover, he mostly uses written tags instead of architectural symbols to convey the presence and features of the city, such as for example its multitude of mosques, signalled at the centre of his map.

Guglingen’s map does not so much represent Cairo as aim to convey his personal experience of that city and its surroundings. Whereas, for example, the side wings of the Holy Land map by Reuwich in Breydenbach’s Peregrinatio represent paths the company did not actually take, and at times fail to show their actual route, with Guglingen we can literally trace his route, and associate each location with the eye-witness description in the text.141 In fact, Guglingen interlaces personal stories in all three of his maps, giving them, in the words of Michel de Certeau, the character of a “tour” rather than a “map, a totalizing stage … from which the describers have disappeared”.142 In this sense, Guglingen’s maps and plan are reminiscent of the antiquarian sylloge Quaedam Antiquitatum Fragmenta (1465) by the Italian humanist Giovanni Marcanova. This manuscript sylloge contains a narrative to guide the reader through an urban topography, enhanced by illustrations of inscriptions in specific spatial contexts. Likewise, the illustrations are the work of a narrator who is also a fervent admirer of the sites he chooses to depict, so as to create a personally involved guide.143 However, instead of an antiquarian desire to make the past visually accessible, Guglingen aims to portray the cultural landscape of the Levant, while evoking the affective experience of a traveller-guide.

Conclusion

The maps and plan in Guglingen’s travelogue convey personal travel experiences, rather than emphasizing Christian shrines per se, or the holy city of Jerusalem, as one might expect. Other illustrated Jerusalem travelogues that incorporate topographical features typically provide maps and plans of Jerusalem itself, the Holy Sepulchre church, and the aedicule of the Holy Sepulchre.144 Instead, Guglingen maps buildings that he perceives as mosques, such as the Ashrafiyya Madrasa in Jerusalem and the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron, and his map of Mamlūk Cairo features “many mosques”. In all three cases, Guglingen records personal encounters with decidedly Islamic spaces, rather than Christian sites. In this respect, the maps and plans in Guglingen’s Jerusalem travelogue are truly exceptional. The only mosque that ever really attracted the attention of Christian pilgrims was the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem.145 Their interest, however, was sparked by a traditional identification of this structure as the original Temple of Solomon, thereby turning it into a Christian hallmark of Jerusalem in their eyes, rather than an Islamic sanctuary.146

Remarkably, Guglingen has made no attempt to Christianize the Islamic spaces his illustrations represent, and accepted Mamlūk reality for what it was. For example, the composition of his map of Cairo and surroundings, and indeed Guglingen’s report of the excursion that inspired it, testify to a large and vivid interest in this foreign city, its many mosques, as well as other monuments. The illustrations of Levantine flora and fauna in Guglingen’s travelogue are likewise inspired by his personal experiences along the way. While these illustrations can more easily be contextualized within the corpus of late medieval illustrated Jerusalem travelogues, Guglingen’s images are unusual because they are based on acute observation, and the associated descriptions show a meticulous attention to detail normally lacking in such accounts. The function of these images in Guglingen’s Jerusalem travelogue is to help the reader form an accurate impression of these plants and animals. By means of short phrases in the text of the travelogue, Guglingen directs the reader’s attention to the pen drawings, and even urges his audience to examine them diligently, as in the case of the banana tree.

Guglingen exclusively chose to illustrate the natural and the cultural world of the Levant, yet not the shrines of Christianity he visited as a pilgrim. This focus seemingly supports the view that curious engagement with remarkable sites and phenomena encountered by pilgrims overseas eventually undermined late medieval pilgrimage, as well as its literature.147 Justin Stagl has influentially summed up this point of view, observing that late medieval pilgrimage literature increasingly reflects curiositas rather than pietas, and concludes that “pilgrimage was losing its legitimacy”, thus opening the way for early modern secular travel.148 This thesis about the secularization of travel has recently been at least partially debunked by research demonstrating that pilgrimage by no means ended at the turn of the sixteenth century, as is often assumed, but instead remained “alive and well and early modern”.149 Moreover, the argument for curiosity as a delegitimizing force for pilgrimage also entails the presupposition that interest for anything but the devout in medieval pilgrimage literature was quite generally experienced as affecting the validity of pilgrimage at its core, at the time. While the maps and illustrations in Guglingen’s Jerusalem travelogue cannot disprove this at a macro level, they can offer a unique perspective on how curious travel and devout pilgrimage could be two sides of the same coin.

These illustrations, the maps and plan, demonstrate that Guglingen’s Jerusalem account projects a religious experience that does not conflict with curiosity about new environments. The illustrations are the most eye-catching feature of the travelogue, certainly requiring more time and attention to design and draft than plain text. It is unlikely that Guglingen would have taken this trouble, if he had suspected that by doing so he would delegitimize his travelogue as an account of pilgrimage. Moreover, we should not forget Guglingen’s credentials as a very devout Observant Franciscan friar who took his Jerusalem pilgrimage very seriously indeed. In the opening statements of his travelogue Guglingen places his conversion to the Franciscan Observance and his inspiration to go on pilgrimage both on the same level of a divine calling.150 Piety permeates all aspects of his mental world: at several points in the travelogue he bursts out in fervent prayer; and once settled in Jerusalem, he devises a complex and time-consuming personal routine for visiting and meditating on a long list of sacred sites.151 Moreover, while the illustrations of flora and fauna may seem secular to our modern eyes, Guglingen would have seen the outstanding creations they portray as signs of the greatness of their Creator.152 Within his brand of Franciscan spirituality, paying attention to the natural landscape one passes through as a pilgrim is equivalent to an act of devotion, not an unwanted distraction.

The visual features in Guglingen’s Jerusalem travelogue represent things that would be unknown to his readership, and therefore difficult to picture. The Christian Holy Places would already be known and imaginable to a Western audience, based on previous reading of religious texts, as well as via visual representations.153 This may well explain why Guglingen chose to illustrate visually only those particular aspects of his pilgrimage experience that he knew would be truly novel to his readers. At the same time, the illustrations in no way detract from the religious experience that his pilgrimage account aims to convey. Guglingen’s illustrated Jerusalem travelogue presents a case for interpreting the combination of curious and devout elements as congruous elements in (late) medieval pilgrimage literature, be it illustrated or not. Rather than as a sign of decay that furthers a particular narrative about the development of early modern travel, the herbological, zoological and ethnographical illustrations in Jerusalem travelogues may be taken at face value, as a valid part of pilgrimage.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by Mediterranean Historical Review 32:2 (01.05.2018, 153-188) under the terms of a Creative Commons 4.0 Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.