Skepticism about religion became a strong player in the philosophical playground.

By Dr. Jesús Zamora Bonilla

Professor of Logic and Philosophy of Science

Dean, Faculty of Philosophy

Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED)

The Origins

We, philosophers, tend to be more skeptical than the average person (though, if you know a little bit of the theories of some philosophers, I would understand that you take my claim with a grain of skepticism). I will take you to a short visit to some of the most charming authors in the history of philosophy: the real skeptics. I will not present the theories of all, not even most of the main skeptical philosophers, but just those I think are more important – those having more to say about philosophy of science.

It would be unfair to say that skepticism was born together with philosophy. What we call ‘philosophy’ started as the attempt by a group of weird Greeks (Thales of Miletus & Co., around 600-500 years before our era) to understand the world just through what they called lógos, which is usually translated as ‘reason’, but that was a term most commonly used to refer to what we call ‘language’ or, more ordinarily, just ‘talk’, or, in the form dialógos, ‘conversation’ (the prefix dia- meaning ‘through’, not ‘two’ –as in ‘diameter’–, as many wrongly believe by a bad analogy with the word ‘monolog’). Stated more simply, Thales and his disciples experimented if they could understand the world with their own human means, not with the help of gods or heroes.

Those philosophers, now known as ‘pre-Socratic’, discussed above all on the question of what ‘the principle (arkhé) of all things’ was. Some identified with water, some with air or fire, some with ‘the indefinite’ (for it could become everything), but some decades later, Parmenides of Elea (a small Greek colony in southern Italy, close to the famous temples of Paestum), attempted to liquidate the question stating that the thing (or principle) that absolutely all beings had in common was… yea… being. What does not coincide with that principle, i.e., with being, is… yea… not being (we would say ‘nothing’). So, being cannot be ‘mixed’ with anything else because… yea… everything that is not being is nothing. Hence, being is the only thing that ‘is’ (we would say ‘exists’). Of course it look to us as if there were many different things, things that now are this way and later are that way, but what logos tells us is that this is just false: the only thing that is, is being, eternally equal to itself. There is no plurality, there is no diversity, there is no change. There is only being.

Perhaps, if philosophy had started in a different land than Greece, this would have been the end of philosophy, with Parmenides’ theory (actually, his poem, for he wrote it in Homeric hexameters) transformed in a kind of mystic cult reciting his verses till the end of the times. But the drug of dialógos was already impossible to eradicate from the Greek people (well, more than one thousand years later emperor Justinian decreed the end of philosophising by closing all the remaining schools of philosophy of the Byzantine empire, sending to the exile to their members who still didn’t want to convert to Christianism), so they continued to discuss and discuss the Parmenidian ontology with more and more elaborate arguments. Some of these are the marvelous ‘paradoxes’ of one of Parmenides’ disciples, Zeno, determined to show that his master was right. You will surely be familiar at least with the argument about ‘Achilles and the tortoise’ (Achilles cannot overtake a tortoise in a run in which the latter has a head-start, for every time Achilles reaches a point on which the tortoise has already been, the tortoise will be at some point further in front; when Achilles reaches that point, the tortoise will be at some other point further in front, and so on and so on; hence, Achilles will have to traverse an infinite number of steps –each of them of what we would call a ‘non-zero length’–, before overtaking the tortoise; hence, Zeno argued, Achilles would need an infinite amount of time to overtake the tortoise).

Other Zeno’s ‘paradoxes’ are less known: for example, he argued that a flying arrow is not really moving, because at every moment in its trajectory, the arrow is exactly in its place (in the space occupying the length from its point to its tail, so to say), and ‘staying exactly in one place’ is the definition of being in rest. Movement would be, hence, something like the combination of an infinite number of states of rest, but if each one of these states is really of rest, there sum cannot be other thing than rest. Hence, there is no really movement. Another ‘paradox’ does not refer to movement: if one grain of millet (or, with an easier example to us, a flake of cotton) falls to the ground, it makes no noise at all; the noise that a bushel of millet (or say, a big sack of cotton) makes when falling is the combination of all the sounds made by every grain within the bushel (or every flake within the sack); but the combination of thousands or millions of no-noises cannot be a noise. Hence, there is no real sound.

I beg you to erase the smile there is now on your face, for Zeno’s ‘paradoxes’ kept mad generation after generation of mathematicians and scientists, till in 19th century a new logical analysis of infinitesimal calculus (the most successful attempt of ignoring -not yet resolving- the problems stated by Zeno) eliminated all the contradictions that disfigured, and a till a scientific study of the neurophysiology of perception was possible even some decades later. Yes, you have read well: the monumental work of Newton and Leibniz you started to study in your high school was simply founded on contradictions, and all mathematicians from 1670 to 1870 (when Dedekind offered his own solution) knew that, in spite of the tremendous success of the calculus in its application to more and more difficult problems. This means that those mathematicians could not claim to have a knowledge of calculus that were ‘based on purely logical principles or self-evident intuitions’ (as it is usually claim in other areas of mathematics): they simply accepted it as valid because it helped wonderfully well to solve a lot of problems and to make a lot of successful predictions. I mean: they accepted the validity of calculus on empirical grounds. By mid 19th century (an essential part of) mathematics was, hence, an empirical science. And many suspect that it still is. But this is taking us too far apart from our story of the skeptics.

To tell the truth, we cannot consider either Parmenides or Zeno as real ‘skeptics’, for after all, they accepted the existence of something (the being), though they doubted of the truth of most, if not all, of our common knowledge. In order to meet the first ‘real’ skeptic we have to let pass a few decades and find another Italian (or, in this case, Sycilian), Gorgias of Leontini, one of the founders of the movement later known as ‘the Sophists’. We actually know almost as little from Gorgias as from his predecessors; it is particularly a pity that we know better some of his main theses than the arguments he himself offered to defend them: what we know are, rather, the attempts of authors several centuries his youngers to understand what Gorgias’s reasons to assert those strange theses could have been, or their own more or less confused understanding of Gorgias’ old text. The thesis, however, seem to have been pretty clear:

- Nothing exists (or, more exactly, ‘being is not’, i.e., the opposite of what Parmenides asserted).

- If something existed, we could no know it.

- If something existed and we could know it, we could not communicate it to other people.

These are obviously startling claims. For the first one, Gorgias’ argument seems to have been that the existence of being, as proposed by Parmenides and Zeno, had been shown to lead to lots of contradictions, so the notion of being is self-contradictory and cannot exist; but, if there is not being, then there is no being. For the two latter claims, the argument probably was that thought is different than being, and words are different than thought. I.e., things do not exist within your head when you think about them, or when you know them… what happens in your head –well, Gorgias very probably would not have talked about the head, but probably about the noûs, intelligence– is one thing, and what happens out in the world is another thing; the same happens with respect language: what you transmit by speaking are sounds, not thoughts (and even less the real properties of the supposedly real things existing ‘out there’). In a nutshell, being, thought, and talk are completely heterogeneous entities, so that no communication is possible between them.

We don’t know (of course we don’t, Gorgias would say) whether he was taking these arguments (or whatever his original arguments may have been) ‘seriously’ or just as a joke. The Sophists, after all, were proud to be capable of convincing us with equal strength of any two opposite claims. So, perhaps Gorgias was simply making fun of Parmenides’ and Zeno’s theories. Or perhaps not.

The Pyrrhonians

The man who very likely is the first skeptic philosopher properly speaking, Gorgias of Leontini, and who, as we saw, is said to have claimed, 1) that the being is not (or ‘there is nothing’), 2) that if some being existed, it could not be known, and 3) if something could be known, it could not be said. This, however, is hardly more a ‘skeptical’ position than that of a strict contemporary of Gorgias, which has become awfully more famous: the Athenian Socrates (approx. 470-399 BCE), the master of Plato (and of many others), whose main thesis is, as you will surely remember, that “I know one thing: that I know nothing”.

Actually, little is what we know with certainty about Socrates’ thought, for he didn’t write anything and each one of his disciples or later philosophers that wrote about his figure attributed to him very different viewpoints. What seems clear is that Socrates practiced a kind of reasoning (or dialog) that committed others to blatant contradictions, showing that the principles on which they were basing their opinions amounted to nothing; the main steps in this method were forcing the other to offer a precise definition of the concepts he was using, and then trying to look for counterexamples of those definitions. Socrates likely referred to this practice (later known as ‘the Socratic method’) as ‘examination’ (skepsis), but his most important followers (Plato in the first place, Aristotle later, as well as others) were confident enough in the capacity of human reason to find something like a firm grounding for rational knowledge (episteme, or, in latin, scientia), both in the theoretical and in the practical realms.

Being the oldest philosophers from which a big amount of writings had been preserved, the history of philosophy derived from Plato and Aristotle’s works has depicted Socrates as someone who put some of the main right questions and developed a way of criticizing the wrong answers, but who, like Moses dying just before entering the Promised Land, didn’t push reason enough to illuminate the right answers. It would have been funny seeing how Socrates himself would have reacted to the writings of these ‘classical’ philosophers; I’d bet that he would have applied his ‘examination’ leading Plato and Aristotle to blatant contradictions no less than he had done with his own contemporaries, who, after feeling so molested by his skepsis, condemned him to death by drinking a hemlock cup.

The truth is that some philosophers played exactly that role, some even from the very seat of Plato (his Academy in Athens, whose leaders of the 3rd century BCE, Arcesilaus and Carneades, are said to have become thoroughly skeptics), but the most influential skeptical school of the Antiquity had been founded a few years before, by Pyrrho of Elis (Elis is on the northwest of the Peloponnese, close to Olympia). Following the master Socrates, neither the ‘Academic’ skeptics Arcesilaus and Carenades, nor Pyrrho (who was a disciple of other branch of the Socratic schools: the Megarians, from Euclid of Megara, not to confuse with the great mathematician Euclid of Alexandria), seem to have written a single line. They saw philosophy rather like a living activity, and teaching as only a kind of direct acquaintance between master and disciple, not committable to dead ink and papyri. Hence, it is difficult to reconstruct their ideas.

Fortunately, something that might resemble the thought of Pyrrho was written five hundred years (!) after he lived, by an obscure author called Sextus Empiricus (approx. 160-210 CE; not a bad name for a philosopher), whose book entitled Pyrrhonian Outlines is our main source to know about old Greek skepticism.

I shall talk in a minute about this book, but I have to confess that the greatest pity is our having lost the work of one direct disciple of Pyrrho, a prolific author named Timon of Phlius (approx. 320-230 BCE), who wrote plenty of books in almost all genres, but who was most famous amongst ancient readers by the book entitle Silloi (‘Satires’ or ‘Lampoons’), mainly written as a dialog between himself and Xenophanes (one of the oldest pre-Socratic philosophers, and he himself reported as author of some satires), and containing burlesque criticisms of most of the philosophies known to the time, very probably based on Pyrrhonian arguments. Another work of Timon we know by secondary references, Indalmoi (‘Images’ or ‘Appearances’) likely was a description of the philosophy of his teacher. Regrettably, as with most of the Greek and Roman authors, just a few decontextualized quotes and references have remained in the best of the cases from Timon’s books.

What is most sure is that Pyrrho’s skeptical arguments were based on the confrontation of claims (for every thesis there are strong arguments in favor and against), on the idea that the most rational attitude in this case is suspension of belief (epoché), and that this is the best way towards the state of the mind that constitutes the greatest good: ataraxía or imperturbability. This certainly sounds weird for us, children of the Christian faith and of the science of the Enlightenment, for, is it not uncertainty what we fear most? Is it not knowledge what can save us, or at least make our lives more comfortable? Ancient skepticism seemed to function under a totally different paradigm: it is so little what we can know with certainty, that strong opinions will almost always cause us harm in a way or another; so it’s better not to have a strong opinion about anything (or, in most versions of ancient skepticism, about anything not directly testable by the senses). It is interesting to compare this strategy for happiness with those of other Ancient philosophical schools, like the Stoics, the Platonics, the Epicureans or the Cynics: in a way, all these schools aimed at the same state of mind (ataraxía) through a combination of accruing knowledge and limiting desire (though they disagree about what we know about the world and themselves, and about what desires are worth being curtailed). Instead, the skeptics looked for a kind of shortcut: it is our realizing that we cannot know basically anything for certain what lead us to deep tranquility.

Going back to our friend Sextus, his book is basically a recollection and exposition of the assortments of ‘arguments’ (or tropoi, i.e., ‘ways’, ‘ways of arguing’) that have been collected by generations of skeptics from the 3rd BCE to 2nd CE centuries, mainly amongst them Aenesidemus of Knossos, who taught in Alexandria in the 1st century BCE. The most famous of these lists is the one known as ‘the ten tropes’, which mentions ten difficulties in establishing the truth of anything.

The following are some of these arguments: Different animals perceive things differently, so, how can we say that the human way of perceiving things is the right one? Also different individuals perceive things differently, or do it so under different circumstances, or through different organs, so, what ensures that your view of things is more accurate, or that sight is a better representation of things than smell? Other arguments referred to differences in moral judgments between different societies, in a way that Greek Skeptics can also be regarded as the founders of cultural relativism. And furthermore, custom tends to makes us judge as normal or unsurprising what, from a different point of view, could be considered as more strange (for example, the sun is much more marvelous than a comet, but, since we the former everyday and the other rarely, we are much more excited by this one).

Other, more abstract set of ‘tropes’, are attributed by Sextus to a certain Agrippa (probably from 1st to 2nd century CE). These are the following:

- Disagreement: about everything there are different opinions with strong reasons in favour.

- Infinite regress: every justification we give of an opinion must itself be justified by another opinion.

- Relativity: everything seems different when considered from another point of view or circumstance (most of Aenesidemus’ tropes were clearly cases of this ‘trope’).

- Hypothesis: Many opinions are held without any argument, and so they are mere conjectures.

- Circularity: Many justifications given for an opinion have this opinion itself as a premise at some point.

Independently of whether we are skeptic or not, it is obvious that Agrippa’s five tropes have become part of what we understand by a rational attitude. The history of Greek skepticism lives much deeper in our mind than what most of us tend to think.

Medieval Doubts

Perhaps you ignore that the most influential philosopher of the early Middle Ages did not really exist. This Zenoan paradox is explained by the fact that the writings of this philosopher were falsely attributed to a different, and much more authoritative person, and hence, after the counterfeit was established about one thousand years later by humanist Lorenzo Valla and others, basically all Medieval philosophers (or it’s better to say theologians) were quoting and discussing the work of someone who was not the one they believed. Since we have no idea of the identity of the real author of those books, history has imprinted the name of the fake author in the philosophical tradition, and so you must not be surprised when finding a reference to someone weirdly referred to as ‘Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite’.

We know basically nothing about the biographies of neither the ‘real’ Dionysius nor the ‘fake’ one. The former is supposed to have been one of the first converts Saint Paul made in his visit to Athens, according to the Acts of the Apostles; the ecclesiastical tradition asserts that he was one of the judges of the Areopagus (a high court that sat on top of a big rock at the foot of the Acropolis) and that, once converted to Christianism, became the first bishop of Athens, but there is no way of knowing whether anything of that is true, nor even the existence of Dionysius himself. Instead, our friend ‘Pseudo-Dionysius’ lived (probably in Syria) surely more than four centuries after the one he took his pseudonym from, and composed a series of books that claimed to have been written by Paul’s Athenian disciple. It is not totally clear whether this ‘claim’ was intended by the real author as a mere literary figure, more or less common in Antiquity, or as a simple and pure attempt to deceive the readers about the identity of the author, and hence about his ‘authority’ (see Bart Ehrman’s book Forged, for a wonderful study of this fraudulent practice in early Christian writings, including several New Testament books). The fact is that, already from the early sixth century C.E. onward, not much later that they were composed, and probably even during the life of their real author, his works were already being uncritically cited as belonging to the ‘old’ Dionysius; so, even without the attempt to deceive, deception occurred. Just to give an impression of how deep the deception was, we can consider the fact that Pseudo-Dionysius is the second most cited philosopher in the works of Thomas Aquinas (13th century), only after Aristotle. Pseudo-Dionysius started to be influential in the West, however, around three centuries after his death, when the Byzantine emperor Michael II gifted a manuscript of his works to Charlemagne, who in turn donated it to the monastery of St. Denis in Paris (by the way, it also circulated the conjecture that the real author of the works was this other Dionysius, the 3rd century ‘apostle of the Gaul’), a manuscript that that was soon translated into Latin.

We know Pseudo-Dionysius was a fake thanks to philological analysis: not only important aspects of his thought, but even full paragraphs of his texts, come from an author four centuries younger than the ‘original’ Dionysius, the Neoplatonic Proclus, probably the last important figure in Ancient, non-Christian philosophy, who was the leader of the Academy in Athens during the second half of the 4th century C.E. Proclus died in 485, and the first known references to Pseudo-Dionysius (or to his preserved books, collectively known as Corpus Areopagiticum) date from about 40 to 50 years later, so our fake author must have lived around the turn of the 4th and 5th centuries, and probably was himself a disciple of Proclus, and a student in the Platonic Academia.

But Pseudo-Dionysius is important in a history of skepticism not, of course, for being an example of how we must doubt even of philosophical authorship, nor because of his thought really being an example of skepticism in the Sophistic or Pyrrhonian traditions we met in the previous entries of this series. After all, Pseudo-Dionysius was a Christian thinker, author, among other things, of a big part of the celestial mythology about the number of heavens and classes of angels you perhaps are familiar with (and which influenced, among other works, Dante’s Divine Comedy): Seraphim, Cheribum and Thrones; Dominions, Virtues and Powers; Principalities, Archangels and Angels. We wouldn’t classify as a skeptic someone that seriously explains that these ‘spheres’ or ‘choirs’ of celestial beings exist. But Pseudo-Dionysius has not passed to the history of philosophy mainly for his taxonomic work in angelic zoology, but for what later has been known as ‘negative theology’ (also known as ‘apophatic theology’; apophasis is a rhetoric figure consisting in mentioning someone or something by stating that one will not talk about him or her, something similar to Spanish PM Rajoy’s alluding to corrupts members of his party as ‘those people I have nothing to say about’).

According to Pseudo-Dionysius, in his book entitled On Mystical Theology, God is absolutely transcendent to human reason, language and knowledge, in a similar way to the aporias Parmenides and his disciples found when trying to talk about Being (recall the first entry of this series). This means that we cannot assert absolutely anything about Him, but we can only negate, for each possible predicate we could think of attributing to Him (say, ‘omniscient’, ‘living’, ‘creator’, even ‘being’, i.e., ‘existing’), that He has the property denoted by that predicate. I.e., we can only say what God is not, and what He is not is just… everything: He is not omniscient, He is not living, He is not powerful, He just is not. God, for example, is no more spirit, son or father than it is ‘soft’ or ‘asleep’. These negations, however, are to be distinguished from ‘privations’: a privation is simply the absence of a given predicate that could be present. The absence of the predicate is opposed to its presence: ‘lifeless’ is opposed to ‘living’. But when we say that God is not ‘living’, we do not mean that He is ‘lifeless’, for actually He is not lifeless either. God is just beyond the lifeless as well as beyond the living. For this reason, Pseudo-Dionysius says that our affirmations about God are not opposed to our negations, but that both must be transcended: even the negations must be negated. This ‘negation’ parallels the only possible human experience of god, that Pseudo-Dionysius exemplifies with the figure of Moses on the mount Sinai, and that describes it as “silence, darkness, and unknowing”. This theory opened the way to the rich mystical tradition in Christianity (recall John of the Cross’s verses, more than a millennium later: “lleguéme donde no supe / y quedéme no sabiendo, / toda ciencia transcendiendo” – “I came into the unknown / and stayed there unknowing / rising beyond all science”). But, skeptic or not, it was most influential as a signal of the limits of human reason to understand ‘the Absolute’, and as a reminder that all theology is, in the end, an exploration out of those limits. Once the faith in the truth of religion (as well as the social power of the Church), became to weakening many centuries later, the existence of negative theology could start to be seen as an argument against the reasonableness of all those attempts of saying anything about God or the divine.

Needless to say, the Middle Ages were not a good time for skepticism, especially for skepticism about the dogmas of religion, but the skeptic tradition managed to survive for more than a millennium, at least under the form of something that philosophers should try to refute. Even one century before Pseudo-Dionysius, the great theologian Augustine of Hippo confessed that, before converting to Christianity, he had flirted with a fistful of philosophical and rhetorical schools, including skepticism, and devoted some pages of his work to rebut some of the skeptics’ arguments, as did many other philosophers afterwards. In doing so, he was the first one of presenting the argument that not everything can be doubted, because when one doubts, one knows for certain that he is thinking: cogito, ergo sum.

However, Medieval philosophy produced a couple of families of arguments that were later fruitfully employed by Modern skeptics (and that worried to some Medieval ones). In the first place, the work of the Arab mathematician, physician and astronomer Alhazen (10th-11th centuries C.E.) established for the first time, in his important work on optics, that visual appearances are created by our cognitive organs, or stated in other terms, that perceptions, even the simpler ones, are always constituted by inferences, and hence are not anything like a ‘direct unity’ with the perceived object (as was defended, e.g., by Aristotle’s theory of perception). In the second place, the idea of God’s omnipotence seemed to entail, according to some philosophers, that He could deceive us if He wants, even when we are feeling the greatest of the certitudes, in seeing something in front of us, or in understanding the proof of a mathematical theorem. But, as it is well known, it was later philosophers who were to extract more interesting conclusions about these ideas.

The Renaissance of Skepticism

Skepticism had a relatively minor role during the development of medieval philosophy, with the main exception of the interesting possibility of interpreting the Pseudo-Dionysius as a skeptic about our knowledge of the nature of God (not, of course, of its being… save for ‘being’ being one of the doubtful things belonging to the nature of something). For all the great medieval theologians, skepticism became rather a kind of ‘straw man’ that they felt obliged to ‘refute’ at some point or other of their long and elaborate writings.

Things started to substantially change by the end of the Middle Ages, with the rediscovery of the text of Sextus Empiricus and other sources about ancient skepticism. But what makes it important the renaissance of skeptical arguments by around the 16th century is not a matter of mere philology, but the power those arguments were destined to have in the enormous social and cultural transformations Western societies were starting to experience. Modern skepticism had three main traditions as its targets: the tradition of science and the tradition of religion, on the one hand, and the ‘traditions’ of, so to say, popular ideas and popular culture .

‘Science’, by 1500-1600, basically meant the scholastic development of the Platonian-Aristotelian worldview, not only in what regards the content of that view, but mainly its method: the idea that human intelligence can grasp the ‘essence’ of things (either by some kind of intellectual intuition, as in the case of Plato, or by some type of induction, as in the case of Aristotle), and derive all necessary knowledge about the world starting from the truths about those essences and proceeding by syllogistic reasoning.

‘Religion’, of course, meant the authority of the Catholic Church and its doctors on the interpretation of the Holy Scriptures (and later, also the intellectual and moral authority of the Reformation leaders’ arguments and writings). Of course, since the philosophy of those doctors was in the end based on the scholastic view of knowledge, most of the skeptical attacks could be directed at both targets at the same time; but it is interesting to maintain the difference, because one of the most striking facts about the evolution of skepticism in the modern age is that it started using the criticism to Aristotelian science as a way of saving the truth of Revelation from the fallacies of scholastic philosophers or religious reformers (depending on the author of each argument), but ended, by the time of the Enlightenment, as a criticism to religion.

This is important: Renaissance and early modern skeptical philosophers were not, in general, critics of the Christian faith, rather on the contrary: they were arguing that human natural cognitive capabilities (as we would say today) are too feeble to allow us to know God in a ‘scientific’, or ‘philosophical’, or ‘metaphysical’ way (no difference existed by that time between these concepts), neither, of course, all the other things God wanted us to know for our salvation. Hence, most Renaissance skeptics were really fideists to some or other extent.

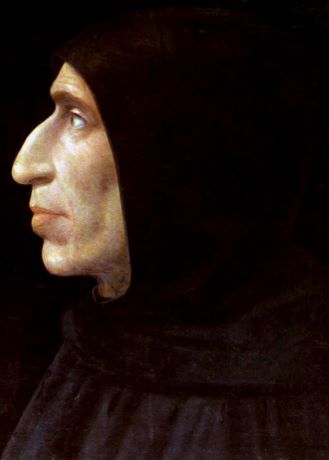

The problem, of course, was: which is the right source of faith? The Italian preacher and reformer Girolamo Savonarola (1452-1498) is the first one whose theses seem to have been inspired by the rediscovered Pyrrhonian arguments of Sextus Empiricus, that he might have known through his friend Pico della Mirandola (1463-1494); Savonarola employed Pyrrhonian style arguments to put under doubt the sources of the authority of the Pope and the church; not being a real philosopher (but most preoccupied in the growing corruption of the clergy and of all society), his standing sermons do not reflect this too directly, but it is a piece of indirect evidence of this Pyrrhonian influence that the main judge in charge of Savonarola’s trial (as well as torture and execution) had to borrow the Greek manuscript copy of Sextus Empiricus (no printed edition existed till 1562, in Latin translation) held by the popes in Rome, in order to mount the official accusation. By the way, that manuscript was later lost.

Curiously, similar but more sophisticated arguments were mounted a few decades later by Erasmus of Rotterdam (1466-1536) in order to establish the limits of human natural rationality as a criticism of a more successful reformist (Luther). In a similar way, authors as Michel de Montaigne (1533-1592) and Blaise Pascal (1623-1662; in this case, a long time after ‘Renaissance’) still used skepticism as a way of limiting the capacity of reason to criticize the truths of Revelation. Of course, these three authors (Erasmus, Montaigne, and Pascal) did not limit to offer a dogmatic defence of the Catholicism, as it is proved by the fact that their works and influence were seen with great suspicion by the Church.

It is precisely with Montaigne that ‘public opinion’ (as we would say in today’s idiom; perhaps ‘customs’ would be a better term, if we include within its meaning the ‘customs of thought’) becomes one of the main target of skepticism. This led to the first most important example of what we could call ‘cultural relativism’ (again, with the ancient Greeks’ permission). Montaigne is, for example, one of the first ones condemning the European conquest of America, as well as the religion wars of his time, on the basis of a criticism to the main philosophical premise that was employed to justify them: the ‘superiority’ of one culture, or one faith, over another.

But probably the most incisive skeptical authors of that time were not those coming from a Christian tradition, but those of Hebrew origins (which, by the way, could easily put arguments against the Catholic Church similar to those put by catholic philosophers against protestants). After all, medieval Jewish philosophy had not such a big debt to Aristotelian metaphysics and epistemology as Christian scholasticism. For example, rabbi Hasdai Cercas (ca. 1340-1410), the head of the Jewish community of Aragon, had vigorously attacked Aristotle in his writings (though his arguments were only known by those knowing Hebrew, and within Christians, mainly by aficionados to the Kabbala).

A much more influential author of Jewish origin would become Francisco Sanchez (1551-1623), born of converted parents, probably in Southern Galicia or Northern Portugal, though educated in Italy and working as a doctor in France for most of his life. His main work gets the undoubtfully skeptical title Quod nihil scitur (“That nothing is known”), published in 1581. The book starts (perhaps more rhetorically than as a real logical move) by denying that one can even know the only thing Socrates said he knew; according to Sanchez, one cannot even know that one knows nothing. Then he offers one of the most elaborate criticism of the Aristotelian view of science, denying that one can proceed from definitions (that are mere words, and that we cannot know whether they describe the ‘real essence’ of things) through deductive syllogisms (that in the end constitute a petitio principii), nor through induction (for we cannot experience everything). Of course, Sanchez remains one of the ‘fideist skeptics’ crowd, asserting that true knowledge can only come to us from faith and revelation. But the seeds of (modern) skepticism were planted and were soon to flourish.

Descartes’ Evil Daemon

Together with the discovery of America, the Protestant Reformation was probably the main historical factor in the (European) Modern Age. As we saw in the previous entry, the debate between different Christian denominations was a perfect breeding ground to put into use the recently rediscovered arguments of the ancient Greek Skeptics (though in practice the ‘debate’ was, for 150 years, more the job of weapons and fires), and the main casualty of that polemic was, instead, the Aristotelian, scholastic view of ‘science’ (not distinguishable till then from ‘metaphysics’ or ‘philosophy’) that had developed in the Middle Ages to support the Christian view of the world. Christian faith, however, survived basically intact, though multiply diversified, from these debates of the early Modern Age, with the only caveat that, by the end of the Thirty Years war, it was more or less clear to most ‘intellectuals’ that the dogmas of religion cannot be based at all in ‘reason’, but come from mere faith (though, of course, reason still had an important role in maintaining the internal coherence of the dogmas and to avoid blatant contradictions between them and worldly savoir); but by mid 17th century, (Christian) faith was still seen as a legitimate source of ‘knowledge’, whereas Aristotelian metaphysics had suffered so lethal blows that it had already gone through most of its way to the dusty shelves of the history of philosophy and the obscure aisles of theological faculties, from which he never raised again as a robust foundation of scientific research and knowledge (save, perhaps, in the case of biology, in which it somehow lived a couple of centuries more).

I shall deal in a future entry of the series about the turn from this ‘religion-friendly’ to a more hostile-to-faith species of modern skepticism from mid 17th century on. My topic here will be, instead, the transformation of epistemological scepticism from its more moderate brand prevalent in the Renaissance (i.e., from a version conspicuously addressed towards a limited set of targets), to its most radical version, as a universal claim against basically all forms of knowledge about the world. As it is well known, the author that helped the most to fully open the perilous Pandora’s box of skepticism was René Descartes (1596-1650), mostly in his tremendously influential books Discours de la Méthode (anonymously published in Holland in 1637, though it seems that the author’s identity was soon notorious) and Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (published in Paris four years later). Like the mythological Pandora, Descartes seemed to be confident on his own capacity of closing the dangerous box at his will, but history proved it wasn’t going to be so easy.

After two centuries of, so to say, guerrilla attacks to Aristotelianism (and all the ‘science’ loosely erected in its surroundings) with the help of Pyrrhonian style arguments, Descartes had the idea of mounting something like a global assault, in the form of a more radically skeptical strategy. Instead of making use of a type of argument (or ‘trope’, remember the second entry of the series) here, of another one there, etc., tailored by the knowledge or prejudices of each author to the peculiarities of the thesis or claim he might by trying to refute, Descartes thought that a single strategy could ‘fit all sizes’, and later tradition called this strategy ‘the methodical doubt’: just reject every assertion or hypothesis as if it were totally false, if there is the minimal chance of its not being demonstrated with the most absolute certainty. The French philosopher, as many after him, must have been frightened at the beginning by the destructive power of this argument: what, after all, can be taken as being beyond all possible doubt? Greek skeptics had favoured empirical knowledge above (Platonic-Aristotelian) ‘intellectual apprehension of essences’ in spite of acknowledging the limitation of our capacity of extracting generalities from observations and the multiple sources of error that can affect our senses, but they trusted to some extent immediate experience, what we immediately observe at the commons sense level. Descartes, instead, is the first philosopher arguing that the whole of experience could be a dream or a hallucination, and hence, we cannot assert that we know even what we are actually perceiving; not that we cannot make inferences, generalisations or predictions with the help of it, but that it just can be false that the things we are seen happening right now in front of our eyes are happening.

No better luck enjoyed the ‘truths of reason’, mathematical propositions paradigmatically, what for other schools of thought had been the paramount exemplar of certitude. To show that error can be at the basis of this other ‘source of knowledge’ Descartes invents one of the most wonderful tales of the history of human thought: the ‘evil demon’ (génie malin) that might have created (or been controlling) our brains or minds, so that it makes us experience the feeling of certitude at the moment of considering some false mathematical propositions. I.e., perhaps 2 plus 2 is not equal to 4, but our minds have been maliciously engineered so that we are utterly sure it is. Of course this is a strange hypothesis, but is a conceivable one, since Descartes strategy has been that of rejecting everything that we can conceive to be false, even logic and mathematics fall demolished by the strength of this skeptical argument.

The rest of the story is well known. Descartes found a lifeboat: even if everything I’m thinking is false, it cannot be false that I am thinking it while I am thinking it. Cogito, ergo sum. And, in the same way as Noah repopulated the Earth with the animals saved in his ark, Descartes happily thought he could prove the validity of many areas of knowledge thanks to the primordial certitude he had found. “Everything which I perceived as clearly and distinctly as I perceive the reality of my own mind must be equally true”. Amongst these certain things, Descartes finds the existence of god, by a curious argument: one of the ideas I discover in my mind is the idea of an infinitely perfect being, but, being myself imperfect (for I doubt lots of things and being in doubt is worse than having real knowledge), I cannot be the ultimate cause of that idea of infinite perfection; only an infinitely perfect being can be the creator of the idea of an infinitely perfect being. Hence, that being exists, and is my creator, and has put in my mind the idea of such a being as a kind of ‘logo’ or ‘trademark’, so that I recognise who has been my creator. And if an infinitely benevolent god, instead of an evil demon, has created my mind with all my innate ideas (i.e., those allowing me to discover mathematical propositions), these ideas must also be true. Hence, everything I can discover about the world with the help of mathematics will be absolutely certain. And in conclusion, this (i.e., what we could call ‘theoretical mathematical physics’) is the new kind of science that has to replace the failed, old-fashioned Aristotelian philosophy.

So, skepticism was for Descartes (as for many before and after him) only a moment in the course of a longer philosophical project. But his efforts to close again the cover of his particular Pandora’s box soon encountered many difficulties in the arguments of other philosophers. The génie malin contained in the box had experienced for the first time the joy of open air, and he was not to allow to be caught in his prison again.

The Mother of All Lost Causes

Descartes’ opening of the Pandora’s box of skepticism, and the liberation of the Evil Demon it triggered, started a terrible shock in the tectonic plates of Western thought, a shock whose waves still reach us with more or less strength, and that mainly contributed to configure our contemporary intellectual landscape. I shall devote the next entry to narrate how post-Cartesian (from the Latin version of Descartes’ name: Cartesius) skepticism affected the status of religious beliefs, but in this one I will concentrate in how the Evil Demon managed to escape from Descartes’ (and a lot of other philosophers of the time) attempts to domesticate it and to persuade him to remain quiet and still in his corner of Pandora’s box.

It goes without saying that Descartes’ arguments in favour of the existence of god, of the reality of the things we ordinarily perceive, and of the existence and properties of our own minds were criticized from the beginning. On the one hand, most of the critiques from, so to say, official university positions pointed to the validity of his methods, in an attempt to save some types of ‘knowledge’ (either Aristotelian science or Christian faith) deemed to be important, but most of this I’ll leave it for the next entry. The other main group of strong opponents to Descartes’s was constituted by who later were identified as the empiricists, and, perhaps not as a coincidence, they tended to be not university professors, at least for most of their intellectually active life. These do not oppose so much to Descartes’ methodical doubt, but to his claims of being able of proving a lot of things thanks to it. Of course, there were other philosophers that agreed with the main Cartesian thesis and elaborated them in a more congenial way; these were later known as the rationalists (the main representatives being Spinoza and Leibniz).

Curiously, one of the first authors that offered an empiricist criticisim of Descartes’ ideas was a French priest (as well as mathematician, astronomer and physicist), Pierre Gassendi (1592-1655), in big part within the context of his attempt to use the empiricist and atomist views of Epicurus as a foundation of knowledge and make this compatible with the teachings and dogmas of the Church (in a similar way as Thomas of Aquinas had done with Aristotle in the middle ages). The English Thomas Hobbes offered also a similar critique during Descartes’ life, and in fact both criticism were included in the wide set of “Objections” (and replies) published in the second edition of Descartes’ Mediationes. Both Hobbes and Gassendi assert that the only reliable source of knowledge are the impressions of the senses, and the more or less uncertain comparisons and analogies that can be derived from them (Hobbes explicitly talked about computations, being the first author equating reasoning with computing, a topic later developed by Leibniz). The supposed “clear and distinct” ideas of Descartes are, says Gassendi, not so clear and distinct at all, and are susceptible to easy misinterpretations. In the line of classical skeptics, Gassendi also asserts that all conclusions derived from reasoning are less certain than the direct acquaintance of the senses, and they can give us not too much insight into the real nature of even the physical things (better available to experimental scrutiny), nor of more abstract entities like the mind or god. It is not strange that Gassendi were one of the first fans of Galileo’s experimental method, applying it to many areas in physics and chemistry, as well as a renowned astronomer of his time (he was the first one in creating a map of the moon). He, however, never explicitly accepted the Copernican model and even publicly defended the Church in the case of Galileo’s trial, though some of his biographers doubt whether his private opinion on the topic was different as the one he had to defend as a Catholic priest.

n one of the strangest twists of the history of philosophy, the dialectic of the discussion between Descartes, Gassendi and Hobbes led several decades later to a totally unexpected point of view. Traditionally, empiricism had been associated with materialism, so strongly that both terms could even have been considered as synonyms: after all, it is material things what we perceive with our senses, whereas ‘the objects of reason’ seem to be all of them utterly ‘immaterial’ entities. In spite of this, another priest, in this case the Anglican, Irish pastor Georges Berkeley (1685-1753), and later bishop of Cloyne, published when he was only 25 one of the strangest philosophical theories of all times. According to Berkeley, yes, it is through our senses that we gain all our knowledge of the world (and in this, he is utterly an empiricist), but all our knowledge consists of ideas (a term borrowed from Descartes himself), i.e., mental representations, which in the case of empirical perception are the colours, sounds, feelings of touch, etc., that we notice. The question Berkeley puts is, then, from where do we derive our notion of matter, or ‘material substance’ or ‘substrate’, that thing in which the perceived objects would consist in the end? According to Berkeley, we just do not have that idea, for the idea is itself a contradiction in terms: the idea (i.e., the mental representation, or ‘sensation’) of something that has properties that can be perceptually represented, but which in itself is not something perceptually representable, i.e., the idea of something of which there can be no idea (i.e., no perception). The only things we can conceive are, so to say, sensory qualities and, obviously, the minds that are having those sensations. To be (hence) is to be perceived, or to be a mind that perceives. Esse est percipi. Matter does not, cannot exist, for it corresponds to an internally inconsistent notion, and the only things that are real are our minds and their perceptions, and of course the mind that guarantees that everything is existing even when we do not perceive it: the mind of god, Who is permanently perceiving everything.

This theory was referred to as idealism (the opposite of materialism), and had later numerous sequels that fall outside the scope of my story. Berkeley was as far as to deny the existence of general concepts (what the hell is the general notion of a triangle, i.e., a triangle that is neither right, nor acute, nor obtuse?), as well as the consistency of Newton-Leibniz infinitesimal calculus, with arguments that, as we saw, were not convincingly contested till more than one century later. He also wrote on other stranger topics, like the nearly universal virtues of the infusion of tar (pine resin), a best-selling book of the time, or the convenience of baptizing slaves so that they obey their masters not only for fear of the whip, but for the fear of god (an argument developed in Bermuda when he spent there a couple of years trying to build a school for priests in the colonies).

But the philosopher who was to take the curse of the Evil Demon to its limits was, also in the 17th century, the Scotch David Hume (Edinburgh, 1711-1776), who also in his twenties published a book that went much further than that of Berkeley: the Treatise of Human Nature (1739), a work of which only a few samples were sold at the time, and that later he resumed and re-elaborated in a couple of shorter and much more popular works, in particular, for our topic, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748), which, according to the modest author of this series, is the most important philosophical books of all times.

Hume is sympathetic to the spirit of the Berkeleyan criticism to the idea of matter: we just don’t have any idea at all of what an ‘imperceptible substratum’ of material things can be (though, of course, we may have the idea of objects so small that cannot be seen, like atoms, e.g., as far as we represent them through sensory ideas). But Hume claims that exactly the same can be asserted about the mind (or the soul, like was still typical to say): we don’t perceive our mind perceiving the sensory representations we see, we simply see those sensations; actually, it is an unjustified conclusion to say that I am perceiving a sensory idea; what the sensory experience directly shows is only itself, i.e., that some sensory experience (a colour, a sound…) is being real at this moment. Is there a subject ‘having’ that sensation? The idea of such a ‘subject’ is, for Hume, as dim as the idea of ‘material substrate’ was for Berkeley. The Cartesian sentence, “I think, therefore I am”, should be changed for something much more simpler, like “there is a thought now; full stop”.

But Hume went even much further. Both Cartesians and anti-Cartesians, even Berkeley himself, had used an almost unnoticed principle in order to conclude about the existence of almost everything whose existence they wanted to prove: the external world causing our sense impressions (let it be ‘material’ or ‘ideal’), our minds as the receptors of these impressions, and even god himself as the uncaused cause of everything else. I am referring, of course, to the principle of causality, according to which everything that happens must have a cause to happen. Hume asks what can be a demonstration of the validity of this principle. It cannot be a ‘truth of reason’ because, he says, we can conceive that something happens without a cause, and truths of reason are only those propositions whose negation is a contradiction, and hence, something impossible to conceive. Can we, then, know the truth of the principle by experience? This question led Hume to one of his most famous arguments: every time we derive a conclusion from experience (e.g., every time we make a generalisation, or a prediction), we are assuming that what we have not observed will follow the same regular connections we have actually observed; for example, we assume that the samples of water we have not seen heating till 100º C at normal pressure will transform in vapour when they do it.

Stated differently, we are assuming something even more abstract that the principle of causality, which is the principle of induction: if something has happened in some way every time we have observed it, it will happen in that same way every time simpliciter. But again, how can we demonstrate that this principle is valid? Like the principle of causality, it is not a truth of reason (we can conceive cases in which it fails; furthermore, if it were a truth of reason, why would we feel more certain that a generalisation is valid when we have observed it in lots of cases, than when we have observed just a few ones). Hence, can we demonstrate empirically that the principle of induction is valid? Not at all, again, for this would be a blatant petitio principii: “if the principle of induction has been observed to be valid in the cases we have observed it, then, by induction, we conclude that it will be valid in all cases”. Hence, the principle of induction is not a valid type of argument, nor can be used to prove that everything must have a cause. We are totally limited to the empirical regularities we have observed, and to our (felt) conjecture or expectation that these regularities are more or less permanent. But all our conjectures can possibly fail at some point, so there is, nor can there be, nothing as a ‘certain knowledge’ of the world, much less of all types of things that can neither directly nor indirectly be observed by us. We cannot even be sure of our memories, because our present experience of them is assumed to be an effect of past events (the facts we observed, and the fact that we observed them), and if the relation of cause-and-effect is not sure, who knows if there is a cause of our having memories now, or what that cause may be. In conclusion, what we call ‘knowledge’ is, rather, the custom or habit of expecting that the operations of nature are everywhere and every time as we think we have observed. No surprise that, after hours and hours speculating about these things, the only sensible reaction for Hume were to go out and play billiard with the friends for perhaps no less hours.

The Vulgate Wars

If you have been following this series, I guess you will by now have learned a few surprising details about the history of western thought. For example, the fact that Ancient skeptics considered that it was suspension of belief, rather than the search for certainty, what most plausibly could lead us to happiness (through the virtue of imperturbability: ataraxía); or the fact that radical empiricism, though usually associated in contemporary times to some type of idealism (the view that mental-stuff-made ‘sense-data’ are our only direct access to knowledge), was considered till the beginning of the Enlightenment as the most typical form of materialism; or the fact that the target of most skeptics’ works, at least till the first centuries of Modern Age, was not ‘faith’, or ‘religion’ at all, but mainly what at their contemporaries took as ‘science’. We shall make a brief detour in the chronology of our history of skepticism (that in the previous entry had reached the work of Hume at the peak of the Enlightment), in order to look over the convoluted story of how religion ended being the most paradigmatic victim of skeptic arguments.

Of course, it had been our good-old-fashioned Greek philosophers who have started to offer something like a ‘rational critique of religion’. For example, the pre-Socratic Xenophanes of Colophon (6th century B.C.) had already exposed the irrationality of attributing anthropomorphic qualities to the gods, and the Epicureans had also submitted to radical scrutiny the traditional practices associated to established religions as long as they were based on mistaken ideas about the nature of the gods (who, according to Epicurus, were so perfect and happy that didn’t care a dime by our human miseries). But most of the few Middle Age and Renaissance authors that (to some limited extent) might be classified as ‘skeptics’ didn’t target their arguments against the ‘truths of (Christian, or Muslim, or Hebrew) revelation’, i.e., against religious faith, but rather against the standard philosophical theories of their time. Furthermore, in many cases their skepticism was rather a weapon against the possible superiority of rational enquiry over religious faith.

However, for more than a millenium of contact with philosophical theories, monotheistic religions hadn’t had an easy relation with these. The Platonic philosopher Celsus (2nd century CE) had offered a devastating disparagement of some central Christian claims, showing how literally absurd they were from a rational point of view, but the work of a colossal army of theologians during the next centuries (starting with Celsus’ immediate critic, Origen) had helped to build a complex philosophical scaffolding that served to make the dogmas of religion more or less swallowable for regular logical minds, but most of the attempts to elaborate a dialogue between revelation and one or other classical philosopher had led to a myriad of skirmishes, and not always bloodless ones, and not without insisting that, however, the relations between ‘reason’ and ‘faith’ might be stated, the latter was immensely superior to the former as a foundation of our knowledge of God and our salvation.

Under the religions ‘of the Book’, the notions of ‘faith’ and ‘revelation’ were hardly distinguishable from their respective sacred texts themselves, the Torah, the Bible, or the Kuran. Actually, the youngest of the three big monotheistic religions was so conscious of that identity that, since the beginning, it devoted every possible effort to preserve the integrity of its own sacred book, a human effort that, of course, though much more successful than in the case of the Christian and Hebrew Bible, could not have been absolutely infallible. This means that the rational scrutiny of the sacred texts could always be a substantial danger for the integrity of the faith, and those religions tried to build a formidable institutional protective wall that could prevent that the study of their Books was done in inconvenient places or by inappropriate people. It was, of course, Renaissance humanists who took the obvious step of thinking that, what they were doing in order to ‘recover’ the purity of texts of classic Greek and Latin philosophers, poets, grammarians, and historians, could also be done in order to analyse the biblical texts themselves.

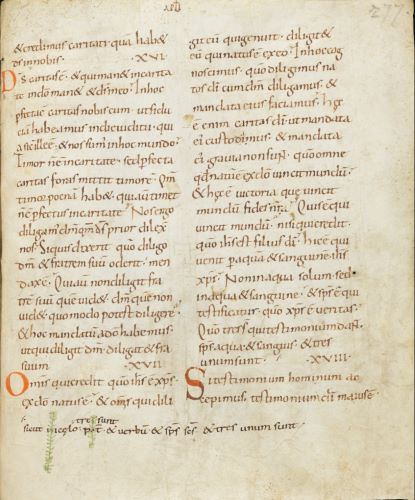

The case was still clearer for Roman Catholics (as compared not only to Hebrews and Muslims but to Greek orthodox Christians), for in their case the sacred, revered and assumedly inerrant text was nothing else than a translation, a translation largely performed by one single man, St. Jerome, between the 4th and 5th centuries. It was this Latin text, known as the Vulgate, the one that was used not only in the Catholic masses, but as the most legitimate source of quotations whenever someone wanted to back any opinion, sentence, or discourse with ‘the word of God’. But of course, Catholics couldn’t really pretend that their God ‘speaks’ Latin as Muslims do pretend that Allah ‘speaks’ Arabic. Neither Moses, nor Jesus, nor Paul spoke or wrote in the language of Julius Caesar (Paul perhaps could speak it if it is true that he was a Roman citizen, but all his preserved writings are in Greek, even his Letter to the Romans), and on top of that, contrarily to the case of the Kuran, the Christian Bible, and particularly the New Testament, is an heterogeneous collection of books written by diverse authors during a span of time of one century or more, of which many different and often conflicting copies survived, and that were immersed in a pool of many other texts (later known as the ‘Apocrypha’) equally reclaiming for themselves the authenticity associated to Christ’s Apostles or at least that of their first followers.

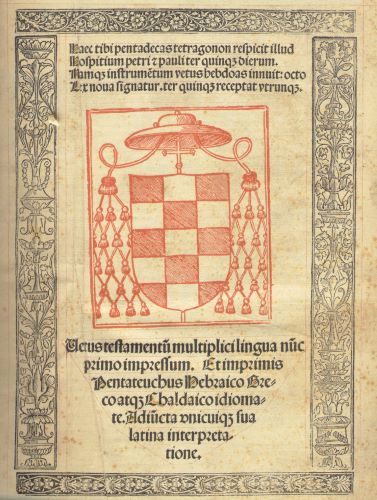

For many humanists of the Renaissance, the temptation of applying their philological savoir-faire to the problem of establishing a proper edition of the Greek text of the New Testament, as well as a proper translation of it into Latin, must have been incredibly exciting. It was Erasmus of Rotterdam, whom we have already met in passing a few entries ago, the first humanist in completing such a work, in a formidable priority race against the publishers of the Complutensian Polyglot Bible: Erasmus published the first printed edition of the Greek New Testament (under the title of Novum Instrumentum, and later known as Textus Receptus) in 1516, whereas the scholars in charge of the edition of the Alcalá Bible, comissioned by cardinal Cisneros to a team whose director was Diego López de Zúñiga, didn’t see it published till 1520 (though it is possible that the New Testament translation had been completed and printed already by 1514, after ten years of work, though it was only published six years later, when the whole Bible edition was ready). In his command to work on the new edition of the Bible, Cisneros had stated that his main goal was “to revive the hitherto dormant study of the scriptures” with the help of the best possible scholars; he tried to enrol Erasmus himself in the team (to which several converted Jews belonged), but the Flemish refused, preferring to work on his own project, and probably having access to a larger set of Greek manuscripts in German and Italian libraries. Erasmus’ refusal gave occasion to his famous phrase “non placet Hispania” (in a letter to Thomas More), what some attribute to his disliking the prevalence of people of Hebrew origin within the Spanish academia of the time.

Humanists had three fundamental concerns regarding the Vulgate. First, the text, through more than a millenium of copying manuscript after manuscript one by one, had been corrupted to an inadmissible degree for a philologist; so, by the 15th century, knowing what exactly the text of Jerome’s translation had been had become a serious problem in many cases, for different manuscripts contained different readings at many points. Second, the fact, already mentioned, that the Vulgate was after all a mere translation, and a good edition of the Greek text itself (particularly of the New Testament) was needed in order to illuminate the true sense of God’s revelation to the inspired writers. And third, and not less important, the fact that the Vulgate language was… exactly that: vulgar (yes, it was). The Lusitanian pope Damasus I had commissioned Jerome by the end of the 4th century with a translation of the Bible to an idiom that most Latin speaking people of the time could easily understand, for most of the partial translations already existing (what later became known as Vetus Latina) had been poured into a rather ‘classical’ (i.e., Ciceronian) language, a language that, to almost everyone except the most learned, had become by that time not totally unintelligible, but greatly so, especially because most of the Latin speakers of the time were not of Roman origins. The grammatical and lexical subtleties of a Virgil or a Lucretius, that more than a millenium later will make the delights of the humanists, had been literally crushed by generation after generation of ‘barbarians’ that, across the Empire, had been forced to learn Latin as adults, or from people that had learnt it that way; a Latin they didn’t have received, on the other hand, from the exalted writings of poets, by from the coarse mouths of rustic sergeants. Jerome’s work was, hence, that of translating the Bible to vulgar Latin. By the way, most of the texts of the New Testament had not been originally written in a very elevated Greek, to say the least, and so a Ciceronian translation of them was certainly a ‘betrayal’ in a sense.

Nonetheless, the effort of producing a better edition and translation of the Bible could hardly be kept in the tranquil waters of philological erudition. Zúñiga, for example, authored several pamphlets against Erasmus, accusing him of being much better a philologist than a theologian (or, to be more precise, of knowing and understanding much better the Latin classics than the Fathers of the Church, on whose comments to the Biblical texts many of Jerome’s lexical choices were based). From the Spaniard’s point of view, this had led Erasmus to commit blatant mistakes in his translation, offering readings that could be used to justify almost any conceivable heresy, and that soon were associated to the most hated villain of the time both in Rome and in Spain (Martin Luther), in spite of Erasmus’ indication that he had published lots of works criticizing the theses of the German reformer and defending the legitimacy of the Church. Just to give a couple of examples: Erasmus’ translation says mysterium or arcanum in the passages in which the Vulgate refers to marriage as a sacramentum, what could be interpreted as a denial of the Church power. He also chooses to translate the Greek kyriótetos as dominium, instead as the Jeromian dominatio; this may seem a trivial difference, but Zúñiga argued that dominatio is a better option because dominationes is how the Church traditionally refered to one of the choruses of angels in the heavenly courts (remember the angelo-zoology of the Pseudo-Dyonisus from the third entry of this series). Erasmus’s own sarcastic and Epicurean answer to this last critique was that he didn’t imagine that the angels were going to feel very offended by been called “dominions” instead of “dominations”.

After many disputes like this one, a ‘definitive’ (and more or less humanist-friendly) version of the Vulgate was commissioned by the Catholic Church in the council of Trent by the mid 16th century, and was finally published in 1590, benefitting from the work of people like Zúñiga, Erasmus, and many others. By that time, however, the war around the Christian sacred text had left many decades ago the field of libraries and universities, to install itself in a non-reversible way in the breakdown of Western Christianity. Even the idea of producing an authoritative and updated Latin version of the Bible had been rendered obsolete by the Protestants’ defence of each Christian’s freedom to read the sacred text in his own vernacular language… a claim that surely the Lusitan pope Damasus would have understood perfectly well by the end of the 4th century. But this freedom, in a moment when the vision of the world was changing so quickly and so profoundly, was soon going to become the worst enemy of the supposed truth of the Bible.

Do You Have a Brain or a Religion?

As you can imagine from the reading of the previous entries, it was by no means an easy task to transform skepticism into a weapon against religious belief. This does not entail that criticisms of religion tout court had failed to exist before, say, the late Modern Age. Not to mention again our adorable Greeks, in the Middle Ages there was a fistful of Arabic thinkers that seemed not to be happy at all about the supposed truth of Islam. For example, the Syrian poet and philosopher Al-Maʿarri (born near of Aleppo by the end of the 10th century) criticized religion and their sacred Scriptures for being just a collection of idle tales and legends, but mainly criticized believers for accepting the dogmas of religions without submitting them to the scrutiny of reason; he even wrote that “the inhabitants of the earth are of two sorts: those with brains, but no religion, and those with religion, but no brains.” As many of the people we shall meet here, Al-Maʿarri was not an atheist strictly speaking, for he didn’t deny the existence of god though he probably thought of the divine as an impersonal being, and he did explicitly reject the afterlife. Two almost contemporaries of Al-Maʿarri were the Persians al-Rawandi and al-Warraq, with similar views on the irrationality of most religious beliefs. Curiously, ‘Ibn Warraq’ has been the pseudonym recently chosen by the occult author of the famous book from 1995, Why I am not a Muslim.

But in the West, open criticisms to the Christian Bible had to wait for centuries. This does not mean that the Bible had been read in a totally uncritical way, blindly assuming its literality. Church fathers and theologians had assumed that the Bible words are usually allegoric, containing a transcendent meaning for which the literal one was often not of the highest relevance. It was also patently clear for the connoisseurs that the Scripture contained some blatant contradictions (e.g., three of the four gospels say the Last Supper was on Thursday, but John’s claims it was on Wednesday), and that Jesus himself talked to his disciples in parables, so many of the other things the Bible says could be ‘parables’ of a kind. But, besides these marginal and very technical reasons for suspecting that not all of the Bible text could be literally true, the fact is that most of what it says was assumed ‘by default’ as… well… the Word of God, and therefore, the truest of all the truths, especially while careful study of the Biblical text was limited to the most educated of the members of the Church.

But the massive translation and printing of the Bible into vernacular languages starting from the 16th century, as well as the proliferation of theological and philological disputes, not only amongst Catholic scholars, but also between members of different and rivalling confessions, all these made that more and more people started to feel free to have a say on what is written in the Bible. Perhaps the first important author daring to publish in a book a more or less systematic criticism of the content of the Scripture was the British philosopher Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679), also one of the founders of modern empiricism and materialism, though it is better known as the father of the modern political theory, soon followed by Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677), a Dutch champion of rationalism, who was a Jew of Sephardic (most likely Portuguese) descent. Both authors are also important for being amongst the first ones to defend that religion must not only be separated from the State, but must be submitted to the laws emanating from the political sources of sovereignty (not insignificantly, both philosophers included their arguments about the Bible into books whose main topic was politics: the Leviathan -1651- in the case of Hobbes, and the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus -anonymously published in 1670- in Spinoza’s). What is most relevant for us now are, however, their arguments about the Bible as a historical document; or more precisely, how those arguments helped to transform the Bible from ‘the Holly Scripture’ into ‘Just-Another-Book-From-Ancient-Times’.

In his Leviathan, Hobbes employs the Bible as a continuing source of philosophical inspiration and authority, in a similar way as many other authors had done during the previous centuries (Leviathan is, after all, a mythical beast mentioned in the Genesis, that Hobbes employs as a metaphor for the political power as the union of the wills of all citizens). But for the first time, he does not abstain from discussing the rational verisimilitude of what the Bible says, neither from offering a rationalistic (or, we would say, naturalistic) interpretation of the text and the stories, rather than a mystical one. So, in a famous passage, Hobbes discusses what is the kind of authority the Ten Commandments had over the people of Israel, taking into account that, even if the Laws had been directly given by God to Moses on the Sinai mount, the people hadn’t seen that, and only experienced Moses coming down with the Tables and saying that these had been given to him by God. According to Hobbes, this entails that, for the people, the authority of the Commandments had just the nature of a political law, to which they must abide by the political authority of Moses, not of a religious law. Hobbes was also the first one in setting out the hypothesis that Moses could not have been the author (or at least, the sole author) of the Pentateuch (i.e., the first five books of the Jew and Christian Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy), as the tradition claimed, for in some parts the text refers to events that supposedly took place after Moses’ death. He also criticizes the interpretation of many of the stories of the Bible as examples of supernatural events and starts a tradition of trying to interpret them as confused and magnified narrations of purely natural phenomena.

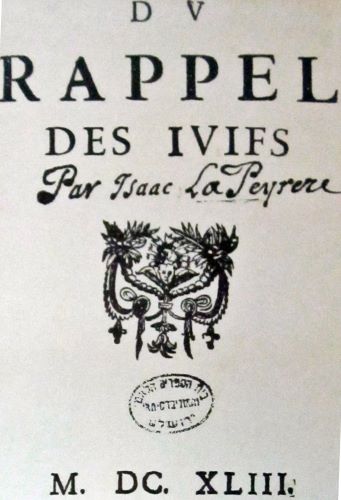

Hobbes’ approach to the ‘authenticity’ of the Bible was, however, neither systematic nor anything but a marginal aspect of his use of the Scripture as a source of authority for his own politico-philosophical project. Similarly, other contemporary authors who started submitting to criticism the truth of many other passages of the Bible, as well as the preservation of its literal content after centuries of copying, basically were employing these arguments as pillars in their own theologian (and political) plans. One example is Isaac de La-Peyrère, a French Calvinist of Jew origin who denied that Adam were the first man or that all the humans alive today descended from Noah; or Samuel Fisher, a Quaker that first started to discuss the problem of how the transmission of the sacred text could corrupt the pristine revelation; or Adam Boreel, a Dutch scholar who claimed that Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad were mainly political leaders using religion as a way of inciting people to follow them. Boreel’s thesis was very influential on a book published anonymously several decades later (1716) and that became very famous during the Enlightenment: Les trois imposteurs, a supposed translation into French of a legendary Latin manuscript from the 13th century, to which Voltaire later replied with his famous thesis that “si dieu n’existait pas, il faudrait l’inventer”.

Spinoza, however, tried a more systematic, rationalistic approach. He also put his arguments to the service of a political project very different from that of Hobbes: though both argued that religious authority had to be subordinated to the power of the civil government, the English was defending an absolutist regime, using religion as a tool for the maintenance of the absolute power of the king, whereas Spinoza is one of the fathers of democratic republicanism, and tried to denounce the use of religion as a menace for the rational and free development of humanity. Having been raised as an orthodox Jew in the relatively tolerant society of 17th century’s Amsterdam, Baruch Spinoza belonged to a family of merchants but soon became interested in the study of science and Cartesian philosophy. His ideas contrary to traditional religion must have risen very early, for when he still was in his early twenties he was harshly excommunicated from the Synagogue (i.e., he was vitriolicly cursed, and any contact of Jews with him was roughly prohibited). The resentment of the Jewish religious authorities against our philosopher must have been so strong that as recently as in 2012, Amsterdam’s chief rabbi (Pinchas Toledano) refused to accept a public petition to remove the anathema against him.

Spinoza’s “preposterous ideas” (to use Toledano’s own terms) were published more than a decade after his excommunication, in his already mentioned Tractatus theologico-politicus, certainly one of the milestones of Western thought (though philosophers, strange as they usually are, tend to have an incomprehensible preference for his other major work, his posthumous Ethica more geometrico demonstrata). The Tractatus constitutes the historical point where rational thinking positively liberates itself from the oppressive dominion of religious dogmas. It starts showing that ‘prophecy’ (in the religious sense of transmitting the word of God, not that of forecasting the future) cannot be taken but for an psychological effect of the imagination of the so-called ‘prophets’, who could by no means be rationally (i.e., Cartesian) certain of the truth of the supposed ‘voice of God’ was telling them. Spinoza (who, by that time, had changed his Hebrew name to its Latinized form ‘Benedict’) then pass to criticize the notion of ‘miracle’, something he simply asserts cannot happen, for constituting a violation of the rational laws of Nature. This, so to say, ‘metaphysical’ criticism must not be confused with the ‘epistemological’ argument forwarded almost one century later by David Hume: that when someone claims have witnessed a miracle, we have two possibilities, that the miracle (i.e., a violation of natural laws) has taken place, or that the supposed witness is wrong. Since, by definition of what a natural law is, it is always more probable that the witness is wrong than that a natural law has been violated, we simply cannot rationally believe that a miracle has occurred. Spinoza proceeds then to criticize, as Hobbes had done some years before, the claim that Moses had been the author of the Pentateuch, but he expands his criticism to cover many of the other books of the Old Testament (like Joshua, Judges, and Kings), which he shows can not have been written near the time of the events they narrate, but many centuries later.

Next, and more importantly, Spinoza introduces the idea that the Scripture cannot be taken as a (privileged) source of knowledge, but as an object of knowledge, i.e., as something that has to be studied on equal foot as any other natural object (or, as we would say some centuries afterwards, ‘scientifically’). The main question is not, hence, whether everything the Bible says is true or not (what Spinoza doubts in a big part), but why does it say what it says. Spinoza’s answer is that the Scripture must not be seen as a literally true account of historical facts, but rather as an exposition of moral lessons. This moral knowledge can also be attained by reason thanks to philosophical analysis, but the Bible was, and is, addressed to unlearned people who has no way of successfully engaging in philosophy, and for whom allegoric tales are a much more efficient way of moral instruction. Spinoza doesn’t doubt that the truth of these moral teachings can be said to have in some sense a divine origin (after all, he, like Descartes, was by no means an atheist), but he definitely rejects the power of the religious and civil authorities to impose on citizens some beliefs or others, and ends the Treatise with one of the first and clearest defences of the absolute freedom of thought and of expression.