The right to vote became the critical step in protecting civil liberties.

Segregated America

Overview

After the Civil War, millions of formerly enslaved African Americans hoped to join the larger society as full and equal citizens. Although some white Americans welcomed them, others used people’s ignorance, racism, and self-interest to sustain and spread racial divisions. By 1900, new laws and old customs in the North and the South had created a segregated society that condemned Americans of color to second-class citizenship.

The Promise of Freedom

For formerly enslaved people, freedom meant an end to the whip, to the sale of family members, and to white masters. The promise of freedom held out the hope of self-determination, educational opportunities, and full rights of citizenship.

“Now we are free. What do we want? We want education; we want protection; we want plenty of work; we want good pay for it, but not any more or less than any one else…and then you will see the down-trodden race rise up.” – John Adams, a former slave

In the above Civil War handbill for black recruits, African American soldiers are shown liberating slaves and bringing new hope for a good education and a productive way of life.

The Reconstruction Amendments were intended to extend the rights of citizenship to African Americans. The Thirteenth Amendment (1865) abolished slavery; the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) extended “equal protection of the laws” to all citizens; and the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) guaranteed that the right to vote could not be denied “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

The only way to guarantee freedom for formerly enslaved African Americans was to grant them the full privileges and responsibilities of citizenship. The right to vote became the critical step in protecting their civil liberties. It would also be the first of their freedoms taken away.

“Slavery is not abolished until the black man has the ballot.” – Frederick Douglass, 1865

For much of the Reconstruction era, from 1869 to 1877, the federal government assumed political control of the former states of the Confederacy.

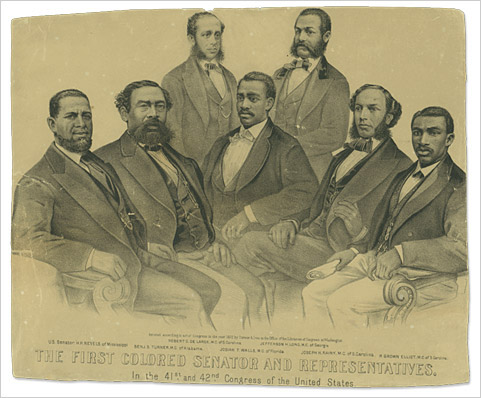

Voters in the South elected more than 600 African American state legislators and 16 members of Congress. Black and white citizens established several progressive state governments that attempted to extend educational opportunities and civil and political rights to everyone.

White Only

By the late 1870s Reconstruction was coming to an end. In the name of healing the wounds between North and South, most white politicians abandoned the cause of protecting African Americans.

In the former Confederacy and neighboring states, local governments constructed a legal system aimed at re-establishing a society based on white supremacy. African American men were largely barred from voting. Legislation known as Jim Crow laws separated people of color from whites in schools, housing, jobs, and public gathering places.

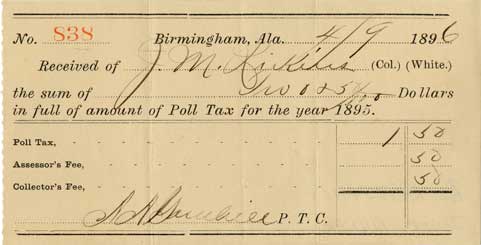

Denying black men the right to vote through legal maneuvering and violence was a first step in taking away their civil rights. Beginning in the 1890s, southern states enacted literacy tests, poll taxes, elaborate registration systems, and eventually whites-only Democratic Party primaries to exclude black voters.

The laws proved very effective. In Mississippi, fewer than 9,000 of the 147,000 voting-age African Americans were registered after 1890. In Louisiana, where more than 130,000 black voters had been registered in 1896, the number had plummeted to 1,342 by 1904.

Poll taxes required citizens to pay a fee to register to vote. These fees kept many poor African Americans, as well as poor whites, from voting. The poll tax receipts displayed here is from Alabama.

The above songbook, published in Ithaca, New York, in 1839, shows an early depiction of a minstrel-show character named Jim Crow. By the 1890s the expression “Jim Crow” was being used to describe laws and customs aimed at segregating African Americans and others. These laws were intended to restrict social contact between whites and other groups and to limit the freedom and opportunity of people of color.

Insulting racial stereotypes were common in American society. They reinforced discriminatory customs and laws that oppressed Americans of many racial, ethnic, or religious backgrounds. The early 20th-century advertising cards depict common stereotypes of African Americans, Chinese Americans, Jews, and Irish Americans.

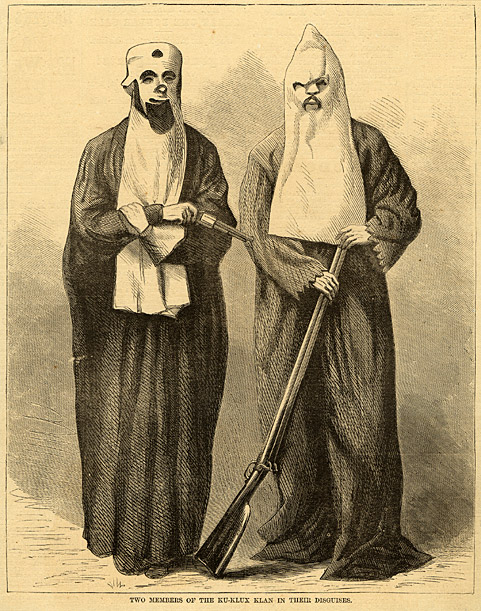

The Ku Klux Klan was founded in Pulaski, Tennessee, in 1866 to combat Reconstruction reforms and intimidate African Americans. By 1870 similar organizations such as the Knights of the White Camelia and the White Brotherhood had sprung up across the South. Through fear, brutality, and murder, these terrorist groups helped to overthrow local reform-minded governments and restore white supremacy, and then largely faded away.

By the mid-1920s the Klan was again a powerful political force in both the South and the North, spreading hatred against African Americans, immigrants, Catholics, and Jews.

Klan membership plummeted later in the decade after a series of scandals involving its leadership. But by then, the Klan had inflamed racial hatred and strengthened the political power of white supremacists in many parts of the country. This Ku Klux Klan robe and hood date from the 1920s.

The fight over civil rights was never just a southern issue. This ballot is from the race for governor of Ohio in 1867. Allen Granbery Thurman’s campaign included the promise of barring black citizens from voting. He narrowly lost to future president Rutherford B. Hayes. Thurman was then appointed U.S. Senator for Ohio, where he worked to reverse many Reconstruction-era civil rights reforms.

Race and white privilege have long been central issues in American politics. At the Democratic presidential convention in 1948, southern delegates broke with the party over civil rights and formed the State’s Rights Party.

Their nominee for president was a prominent segregationist, South Carolina governor Strom Thurmond. He received more than a million votes and carried four southern states—Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and South Carolina. His campaign sent a clear message to the nation that the South would not give up segregation without a fight.

Separate but Equal: The Law of the Land

African Americans turned to the courts to help protect their constitutional rights. But the courts challenged earlier civil rights legislation and handed down a series of decisions that permitted states to segregate people of color.

In the pivotal case of Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racially separate facilities, if equal, did not violate the Constitution. Segregation, the Court said, was not discrimination.

In 1890 a new Louisiana law required railroads to provide “equal but separate accommodations for the white, and colored, races.” Outraged, the black community in New Orleans decided to test the rule.

On June 7, 1892, Homer Plessy agreed to be arrested for refusing to move from a seat reserved for whites. Judge John H. Ferguson upheld the law, and the case of Plessy v. Ferguson slowly moved up to the Supreme Court. On May 18, 1896, the U.S. Supreme Court, with only one dissenting vote, ruled that segregation in America was constitutional.

The Battleground: Separate and Unequal Education

Overview

After the Civil War, millions of formerly enslaved African Americans hoped to join the larger society as full and equal citizens. Although some white Americans welcomed them, others used people’s ignorance, racism, and self-interest to sustain and spread racial divisions. By 1900, new laws and old customs in the North and the South had created a segregated society that condemned Americans of color to second-class citizenship.

Denied public educational resources, people of color strengthened their own schools and communities and fought for the resources that had been unjustly denied to their children. Parents’ demands for better schools became a crucial part of the larger struggle for civil rights.

The Educated Citizen

Americans have long believed that a healthy democracy depends in part on free public education. The nation’s founders stressed that an educated citizenry would better understand their rights and help build a prosperous nation. Beginning in the early 1800s, the federal government and the states encouraged a public school system, largely under local control.

For millions of children, the American public school movement opened new opportunities. But millions of others were excluded because of their race or ethnicity. Segregated education was designed to confine these children to a subservient role in society and second-class citizenship.

Quest for Education

Before the 1860s most of the South had only a rudimentary public school system. After the Civil War, southern states ultimately created a dual educational system based on race. These separate schools were anything but equal.

Yet, the commitment of African American teachers and parents to education never faltered. They established a tradition of educational self-help and were among the first southerners to campaign for universal public education. They welcomed the support of the Freedmen’s Bureau, white charities, and missionary societies. Black communities, many desperately poor, also dug deep into their own resources to build and maintain schools that met their needs and reflected their values.

“We went every day about nine o’clock, with our books wrapped in paper to prevent the police or white persons from seeing them…After school we left the same way we entered, one by one, when we would go to the square about a block from school, and wait for each other.” – Susie King, who attended a secret school in Savannah, Georgia

The Freedmen’s Bureau was established in 1865 to aid formerly enslaved African Americans. Its limited resources never met the tremendous demand for education from African Americans across the South.

To meet the enormous desire for education among African Americans, northern charities helped black communities start thousands of new schools in the South. One of the largest programs was the Julius Rosenwald Fund, established in 1914 by a Sears, Roebuck, and Company executive.

The fund required matching contributions from local communities. Even in the poorest rural areas, black men and women held fundraisers, donated land, and built schools with their own hands.

Northern missionary societies founded some of the first schools for southern blacks after the Civil War. Missionary schools continued to provide education well into the 20th century. The above photograph album belonged to Fred and Mary Vandivier, teachers at the Southern Christian Institute outside Edwards, Mississippi, about 1917.

Despite the burdens of segregation and racism, some high schools and colleges for black students provided educational opportunities that rivaled those offered to white students. Morehouse College and Tuskegee, Howard, and Fisk universities have educated African Americans since the late 1800s. This history class is at Tuskegee University.

Separate public schools were often created for Asian, Latino, and Native American children. Where there were not enough children of a single racial group to form their own school, they were usually required to attend black institutions.

“Colored” and “white” schools in Paxville, South Carolina. In some southern states, white schools received two to three times more money per student than black schools. Black taxpayers in several states not only bore the entire cost of their own schools, but helped support white schools as well.

School administrators often took a hand-me-down approach to black schools. Outdated textbooks from white schools, such as the one above from Raleigh, North Carolina, would be transferred to a local black school.

In Pursuit of Equality

Across the country, parents and community leaders fought a long struggle against school segregation. With little money or public support, they argued their cases before white judges and all-white school boards that had little sympathy for their concerns. The stories here outline three examples of the legal battles in the long fight that eventually led to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the 1840s Benjamin Roberts of Boston began a legal campaign to enroll his five-year-old daughter, Sarah, in a nearby school for whites. The Massachusetts Supreme Court ultimately ruled that local elected officials had the authority to control local schools and that separate schools did not violate black students’ rights. The decision was cited over and over again in later cases to justify segregation.

Black parents in Boston, however, refused to accept defeat. They organized a school boycott and statewide protests. In 1855 the Massachusetts legislature passed the country’s first law prohibiting school segregation. The above image, entitled Turned Away from School, appeared in the Anti-Slavery Almanac in 1839.

Robert Morris was one of the country’s first African American attorneys, and Charles Sumner was a leading abolitionist lawyer. They represented the Roberts family in their suit to end segregated schools. The arguments of the two attorneys echoed through the Brown v. Board of Education case more than 100 years later.

“The separation of the schools, so far from being for the benefit of both races, is an injury to both. It tends to create a feeling of degradation in the blacks, and of prejudice and uncharitableness in the whites.” – Robert Morris and Charles Sumner, in Roberts v. City of Boston, 1849

In 1884 Joseph and Mary Tape attempted to enroll their daughter Mamie at Spring Valley School in San Francisco. Principal Jennie Hurley cited school board policy against admitting Chinese children, and the Tapes took the case to court. On March 3, 1885, the California State Supreme Court said that state law required public education to be open to “all children” and ruled in favor of the Tapes.

After the decision, the state legislature quickly passed a law allowing schools to establish separate facilities for “Mongolians.” Other Asian parents continued the fight for integrated schools until their eventual victory in 1947. This photograph of the Tape family shows Mamie in the center.

Legal Campaign

Overview

Beginning in the 1930s, African American attorneys developed a long-range strategic plan to use the legal system to challenge official segregation in the United States. Their decades-long campaign demanded a powerful strategy, support from black communities across the country, and extraordinary legal expertise.

Two institutions led the way: the Howard University School of Law and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Lawyers, many trained at Howard and supported by the NAACP, helped African American plaintiffs bring lawsuits against segregated school systems. Case by case, their efforts began to undermine the legal principle of separate but equal.

Howard University: Leadership through Scholarship

Howard University is one of the oldest historically black universities in the United States. It was established by act of Congress in 1867 and named for Oliver Otis Howard, a Union general in the Civil War and a director of the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Howard provided education in social sciences, physical sciences, fine arts, law, and medicine at a time when most African American programs were devoted to vocational education. Many Howard graduates became national and international leaders.

Howard University’s faculty included some of the intellectual leaders of the nation. Ironically, they came together at Howard and mounted an effective challenge to segregation partly because they were excluded from teaching positions at white universities.

As a symbol of black aspirations, Howard University had a special purpose. From Howard’s founding, its graduates and faculty have responded to racism in society with service to the African American community.

Charles Hamilton Houston

One of the most influential figures in African American life between the two world wars was Charles Hamilton Houston. A scholar and lawyer, he dedicated his life to freeing his people from the bonds of racism.

Houston earned an undergraduate degree at Amherst College and a law degree at Harvard University. When he returned to Washington to join his father’s law firm, he began taking on civil rights cases. Mordecai Johnson, the first African American president of Howard University, named Houston to head the law school in 1929. Houston set out to train attorneys who would become civil rights advocates.

Charles Houston was one of the most important civil rights attorneys in American history. A lawyer, in his view, was an agent for social change—“either a social engineer or a parasite on society.”

Charles Houston grew up in a middle-class family in Washington, D.C. His father, William Le Pre Houston, was an attorney, and his mother, Mary Hamilton Houston, a seamstress.

During World War I, Houston was an artillery officer in France. He witnessed and endured the racial prejudice inflicted on black soldiers. These encounters fueled his determination to use the law as an instrument of social change.

Charles Houston used the above Dictaphone to make voice recordings that were transcribed into letters and legal documents. He also recorded the testimony of clients and preserved his thoughts about legal strategy and the details of his cases.

William Houston practiced law in Washington, D.C., for more than four decades, and taught legal office management at Howard University’s law school.

Howard University School of Law: Preparing for Struggle

Charles Hamilton Houston became vice-dean of the Howard University School of Law in 1929 and brought an ambitious vision to the school. At the time, courses were offered only part-time and in the evening. Houston created an accredited, full-time program with an intensified civil rights curriculum. His determination to train world-class lawyers who would lead the fight against racial injustice gave African Americans an invaluable weapon in the civil rights struggle.

The above 1931 memorandum from Houston asked all law school staff to provide an overview of their courses and stated his intention to strengthen the curriculum. He diversified the course offerings and made sure students received more rigorous training for work in the field of civil rights.

The row house above in downtown Washington was the home of the Howard University law school when Charles Houston was dean. He strengthened the school’s academic standards and instilled a sense of social mission. Under Houston, the law school graduated a group of highly effective civil rights lawyers, the most illustrious of whom was Thurgood Marshall.

Houston knew many of the foremost legal minds of his day and brought them to Howard as program advisors and speakers. In the above photograph, he poses with Mordecai Johnson, president of the university, and Clarence Darrow, the famed lawyer who defended the theory of evolution in the Scopes trial in 1925.

Houston continued to argue cases in court and work for equality in the legal community during his years as dean of Howard’s law school. When the American Bar Association refused to admit African American attorneys, he helped found the National Bar Association, an all-black organization, in 1925.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

Founded in 1909, the NAACP is the nation’s oldest civil rights organization. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the association led the black civil rights struggle in fighting injustices such as the denial of voting rights, racial violence, discrimination in employment, and segregated public facilities. Dedicated to the goal of an integrated society, the national leadership has always been interracial, although the membership has remained predominantly African American.

Anti-lynching demonstrations by the NAACP challenged the American people and government to face the violence of lynching. Approximately 8,000 black Americans marched down Fifth Avenue in New York City in a silent protest against ongoing murder, violence, and racial discrimination on July 28, 1917.

The NAACP focused on five major areas from 1920 to 1950: anti-lynching legislation, voter participation, employment, due process under the law, and education. At yearly conventions in different cities around the country, it drew attention to regional needs and interests and encouraged nationwide participation.

NAACP’s Legal Team

In 1934 Charles Houston left the Howard University School of Law to head the Legal Defense Committee of the NAACP in New York City. Seeking out bright, dedicated attorneys to join the mission, he built an interracial staff that defended victims of racial injustice. Among the lawyers recruited was Thurgood Marshall, Houston’s star student from Howard’s law school.

In July 1938 policy disagreements and health problems caused Houston to relinquish the leadership of the NAACP legal committee to Thurgood Marshall. Summing up Houston’s contribution to the struggle against segregation and racism, Marshall later remarked, “We owe it all to Charlie.”

Travel was an essential part of being an NAACP lawyer. With this portable typewriter, Charles Houston crisscrossed the country to research and document racial bias and unfair treatment of blacks.

As Charles Hamilton Houston researched the cases, he created a visual record of his observations with still and moving images. He used this information to formulate his legal strategies. As he researched the cases, he created a visual record of his observations with still and moving images. He used this information to formulate his legal strategies.

“Mr. Civil Rights”

Thurgood Marshall grew up in a nurturing African American community in segregated Baltimore. After graduating from all-black Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, he enrolled in Howard University’s law school. In 1934 he began practicing law in his hometown and immediately was drawn into the local civil rights movement.

Thurgood Marshall moved to New York and joined the NAACP legal staff in 1936. In 1938 Marshall took over the leadership of the NAACP legal team from his mentor Charles Hamilton Houston. A year later, he established the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund to carry out the organization’s legal campaign. Marshall’s legal skills, his earthy wit, and easy manner made him an effective leader.

Above is Thurgood Marshall’s high school graduation photograph at age 17. His father was a railroad dining-car porter and steward at a country club; his mother, a homemaker, was a graduate of the historically black Coppin Normal School.

Soon after graduating from law school, Thurgood Marshall took the case of Donald Gaines Murray, an African American student seeking admission to the University of Maryland School of Law. This case went to the state Supreme Court and successfully challenged segregated education in Maryland. Shown above are Marshall, Donald Gaines Murray, and Charles Houston during the 1933 suit against the University of Maryland.

Thurgood Marshall above with the two principal officers of the NAACP: Walter White, the national secretary, center, and Roy Wilkins, the assistant national secretary.

The NAACP Targets Higher Education

A long-range strategic plan grew out of extensive research about the most effective means of destroying segregation. This plan involved mobilizing civil rights plaintiffs and lawyers in local African American communities. Over time, the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund won a series of groundbreaking cases that chipped away at the edifice of segregated university education. These victories served as the legal foundation for a head-on attack on state-imposed segregation.

In 1930 the NAACP commissioned attorney Nathan Margold to produce a plan for a legal campaign against segregation. The Margold Report proposed to attack the doctrine of separate but equal by challenging the inherent inequality of segregation in publicly funded primary and secondary schools.

Charles Hamilton Houston, however, recognized the pervasiveness of racism and believed that they needed to first establish a series of legal precedents. He modified the Margold Report by beginning the NAACP’s legal campaign with lawsuits for equal facilities in graduate and professional schools.

The Power of Precedent

The American legal system is based on the principle of stare decisis—legal precedent establishes the law. The strategy of civil rights lawyers was to get the Supreme Court to make a series of judgments in support of racial integration. These judgments became legal precedents and the foundation for dismantling segregation in public schools.

The legal precedents:

- 1938 Missouri ex. rel. Gaines v. Canada

- 1948 Sipuel v. Oklahoma State Regents

- 1950 McLaurin v. Oklahoma

- 1950 Sweatt v. Painter

Missouri ex. rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938)

In the 1930s no state-funded law schools in Missouri admitted African American students. With guidance from NAACP lawyers, Lloyd Gaines, applied to the University of Missouri law school. Denied admission, Gaines was offered a scholarship to an out-of-state school. Gaines then sued the law school.

When the case reached the Supreme Court, Charles Houston persuaded the justices that offering Gaines an out-of-state scholarship was no substitute for admission. The court ruled that the state either had to establish an equal facility or admit him.

Ada Sipuel was denied admission to the University of Oklahoma Law School in 1946. With the help of the NAACP, she sued the school. Thurgood Marshall argued that separating black students, no matter what the conditions, denied them access to opportunities provided to others.

The law school admitted Sipuel rather than continue the dispute. She went on to become one of the first African American women to sit on the board of regents of Oklahoma State University. The photograph above shows Marshall and Sipuel in 1948, with J. E. Fellows and Amos T. Hall.

Rather than admit Heman Sweatt to its law school, the state of Texas offered to create a separate program for African Americans. The University of Oklahoma accepted George McLaurin to its graduate program in education, but separated him from other students.

Both students sued, and the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ruled that dividing students by race in graduate programs fell short of the legal standard of separate but equal. Interaction among students, the court said, was an integral part of the educational experience.

Five Communities Change a Nation

Overview

When Thurgood Marshall launched the full-scale attack on segregation, the United States was very different from today. For some white Americans, changes in attitudes about race followed dramatic events in American society—the Depression, World War II, the integration of major league baseball by Jackie Robinson in 1947, and the desegregation of the armed forces in 1948. But deeply rooted feelings of white superiority continued to guide daily life.

In five different communities, African Americans from various walks of life bravely turned to the courts to demand better educational opportunities for their children. Together with the NAACP, these communities attempted nothing less than the destruction of segregation in the United States and the transformation of American society.

Bitter Resistance: Clarendon County, South Carolina (Briggs et al. v. Elliott et al.)

In the heart of the cotton belt, where white landowners and business leaders had ruled Clarendon County for generations, poor rural African Americans made a stand. They asked for a school bus for their children, and the county denied their request. Risking retaliation, they raised the stakes and demanded that their children have the right to attend white schools.

Thurgood Marshall committed the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund to help this courageous community make a direct assault on legalized public school segregation. Briggs v. Elliott was filed in the United States District Court, Charleston Division on December 22, 1950.

Briggs v. Elliott Legal Case Summary

Place: Clarendon County in rural South Carolina

Grievance: Starkly unequal, segregated schools for black and white children

Plaintiffs: Harold Briggs and 19 other parents in the county

Decision: A federal district court ruled against the plaintiffs. Their appeal reached the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the 1950s Clarendon County, South Carolina, was the Deep South. Jim Crow laws and customs separated blacks and whites. Challenging this order, African Americans knew, could bring swift and severe consequences.

In 1950 about 32,000 people lived in the county. More than 70 percent were African Americans. Outside the towns of Summerton and Manning, the county was mostly rural and poor. Whites owned nearly 85 percent of the land, much of it leased to black tenant farmers. Two-thirds of the county’s black households earned less that $1,000 a year, mostly growing cotton.

The county provided 30 buses to bring white children to larger and better-equipped facilities. White children from the Summerton area attended the red brick building pictured above with a separate lunchroom and science laboratories. Most rural black schools had neither electricity nor running water.

In the 1950s things were changing in Clarendon County. A new generation of African Americans, many of whom had fought in World War II, saw a world of greater possibilities.

The community’s initial demand was small—a bus for children who had to walk up to nine miles to school. But the indifference of white officials stiffened their parents’ resolve to seek more. At this meeting in the Liberty Hill African Methodist Episcopal Church in 1950, parents signed a petition demanding integrated schools. Thurgood Marshall filed the document with the United States District Court on December 22, 1950.

Harry Briggs’s name appeared first on the complaint. A Navy veteran, he worked as an automobile mechanic. His wife, Eliza, was a maid in a nearby motel. Like many who signed the petition, they were fired from their jobs for their courage and eventually left Summerton to find work.

Outspoken and fearless, Modjeska Simpkins was one of the leaders of the NAACP in South Carolina from the 1930s to the 1970s. In the Briggs case, she helped draft the petition for integrated schools. As a member of the board of directors of the black-owned Victory Savings Bank, she helped arrange loans for some people of Summerton who lost their jobs for supporting the case.

To pursue the complaint in court, Rev. Joseph De Laine turned to Harold Boulware, the leading NAACP attorney in South Carolina. Boulware knew that the national office of the NAACP was looking for school cases to challenge segregation, and he invited Thurgood Marshall to South Carolina. Boulware, also a graduate of the Howard University School of Law, was the first African American to pass the bar in South Carolina since Reconstruction.

On May 24, 1951, Kenneth Clark, a psychology professor at City College of New York, came to Summerton. Using dolls of different colors, he tested the children of Scott’s Branch school to measure how they felt about themselves. He asked the children to show him the “nice” doll, the “bad” doll, and the doll that “looks like you.”

Ten of the 16 children said the brown doll looked bad. The results of these tests strongly suggested that forced segregation damaged the self-image of African American children.

To probe the effects of segregation, Kenneth Clark asked the black children of Summerton to color these drawings. After they colored the other items on the page, he asked the children to color one of the figures to look “like yourself” and the other “how you would like little children to be.”

Fifty-two percent colored the other child white or an irrelevant color. The South Carolina case was the first time this kind of psychological evidence was used in major school desegregation lawsuits. It would become a key argument in the NAACP’s future cases before the Supreme Court.

On May 28, 1951, Thurgood Marshall, Robert Carter, and Spottswood Robinson brought the case before a three-judge panel at the federal courthouse in Charleston, South Carolina. The defendant was Roderick W. Elliott, a local sawmill owner and the school board chairman.

The lawyers argued that segregated schools harmed black children psychologically and violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection under the law. Two of the judges, citing the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896, held that separate-but-equal facilities were constitutional and ruled against the parents.

“I am of the opinion that all of the legal guideposts, expert testimony, common sense and reason point unerringly to the conclusion that the system of segregation in education adopted and practiced in the state of South Carolina must go and go now. Segregation is per se inequality.” – Judge J. Waties Waring, in dissent, Briggs v. Elliott

J. Waties Waring, a member of the three-judge panel, wrote the dissenting opinion. He was one of many white southerners who stood up for justice at a time when many of his neighbors clung to old ways. As a supporter of equal rights, he endured both psychological and physical intimidation and eventually moved from Charleston to New York City.

The NAACP lawyers appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court for the October term in 1952.

Topeka, Kansas: Segregation in the Heartland (Brown et al. v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas)

Slavery was never legally established in Kansas, and racial separation there was less rigid than in the Deep South. School segregation was permitted by local option, but only in elementary schools. In 1950 the state capital, Topeka, operated four elementary schools for black children.

African American parents and local activists from the NAACP challenged Topeka’s policy of segregated schooling. They filed their case in U.S. District Court in 1951. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas gave its name to the collection of cases that ended segregation in public schools.

Brown v. Board of Education Legal Case Summary

Place: Topeka, Kansas

Grievance: Segregated elementary schools, and the harmful psychological effects of segregation on African American children

Plaintiffs: Oliver Brown and 13 other parents from Topeka

Decision: A three-judge federal court ruled against the plaintiffs. The plaintiffs’ appeal reached the U.S. Supreme Court.

Lucinda Todd was the secretary of the Topeka branch of the NAACP and the first plaintiff to volunteer in the lawsuit against the Topeka Board of Education.

Gathered around the above table in Lucinda Todd’s dining room, members of the Topeka chapter of the NAACP committed themselves to challenging segregated schooling.

In the early 1950s Topeka had a population of about 80,000. The city was an economic center for the surrounding farmlands. Hospitals and clinics were the largest employers, and the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad had its headquarters there.

Many African American families had migrated to the city after the Civil War in search of land and opportunity outside the South. Eight percent of the city’s residents were black. Buses and railroads were integrated, but most restaurants, hotels, and other public places were usually segregated—by practice, not by law.

Oliver Brown’s name appears first on the most famous desegregation case in the nation’s history, Brown v. Board of Education. He was a welder for the Santa Fe Railroad and a part-time assistant pastor at St. John African Methodist Episcopal Church.

Pictured above, a student reads aloud in a first-grade class at segregated Washington Elementary School in Topeka. With only four public elementary schools for black children, some students had to take long bus rides to reach their schools, and some of the schools lacked the facilities and programs of white elementary schools.

McKinley Burnett was an outspoken critic of racial injustice. As president of the Topeka NAACP, he had repeatedly petitioned the Topeka Board of Education and had grown frustrated with their refusal to end segregation. In August 1950 he wrote to the NAACP, seeking help in preparing a lawsuit against the school board.

Charles and John Scott and Charles Bledsoe of Topeka, joined by Robert Carter and Jack Greenberg of the NAACP’s national office, presented the case to a panel of three federal judges. The NAACP attorneys argued that segregated schools violated the Fourteenth Amendment and harmed black students.

The judges conceded the damage caused by segregated education. Nevertheless, the Court ruled that white and black schools in Topeka were comparable and that segregation was consistent with the laws of Kansas and the Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson.

“We weren’t in sympathy with the decision we rendered. If it weren’t for Plessy v. Ferguson, we surely would have found the law unconstitutional. But there was no way around it—the Supreme Court would have to overrule itself.” – Judge Walter A. Huxman, reflecting on the decision in Brown v. Board of Education, 1970s

The NAACP attorneys appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court for the October 1952 term.

Black Students On Strike! Farmville, Virginia

Moton High School is just a few miles from Appomattox, Virginia, the site of Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Ulysses S. Grant to end the Civil War. In 1951 African American students from the school fought their battle for access to equal education.

Led by Barbara Johns, a determined eleventh-grader, a group of students organized a strike for a better school. The students rallied their fellow classmates, an entire community, and NAACP attorneys to their cause. Their courage and commitment brought their demand for justice before the nation.

Davis v. School Board of Prince Edward County Legal Case Summary

Place: Rural Farmville, Virginia

Grievance: Overcrowded, underfunded segregated schools for African American children

Plaintiffs: Ninth-grader Dorothy Davis and 116 other students and parents of Farmville

Decision: A federal district court ruled against the plaintiffs. The plaintiffs’ appeal reached the U.S. Supreme Court

Prince Edward County opened its first black high school in 1939. Unlike its counterpart for white students, Robert Russa Moton High School had no gymnasium, cafeteria, lockers, or auditorium with fixed seating. Built with a capacity for 180, it contained 450 students by 1950.

To house the additional students, the school board built plywood structures covered with tarpaper and heated them with pot-bellied stoves. These “tarpaper shacks” became a symbol of all that was wrong with segregated education. The all-white school board promised to build a new school, but never followed through.

While many in the town called for patience, 16-year-old Barbara Johns refused to wait. With a few other classmates, she quietly organized the entire student body. On April 23, 1951, the principal was lured off campus, and all 450 students were called into the auditorium. After the students asked the teachers to leave, Barbara convinced her classmates that they should walk out until a new building was under construction.

Barbara Johns is shown above with her high school teacher. Johns’s name did not appear on the lawsuit. Fearing for her safety, her parents sent her to live with her uncle in Montgomery, Alabama.

At the request of Thurgood Marshall, Hill and Robinson had agreed to look for a case in Virginia to challenge segregation directly. At this meeting in Rev. L. Francis Griffin’s church, they persuaded the students to drop their request for a new school and demand that the court strike down the Virginia law requiring segregated schools.

Then came Davis v. Prince Edward County. Dorothy Davis, a ninth grader, was the first plaintiff listed on the complaint filed on behalf of 117 Moton students. The state reaffirmed its commitment to segregation and challenged the NAACP’s arguments about the harmful effects of segregated education.

According to the state’s expert witness, blacks were intellectually inferior to whites; it was therefore in everyone’s best interest to separate the races. The federal district court upheld segregation in Prince Edward County, and the NAACP lawyers immediately appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The NAACP lawyers appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court for the October term in 1952.

Delaware: Conflict in a Border State (Bulah v. Gebhart and Belton v. Gebhart)

When the Civil War began, Delaware and other border states permitted slavery but refused to join the Confederacy. Issues of race in Delaware reflected this mixed heritage, and both white and black people had misgivings about school desegregation. Yet, laws on segregation followed the state’s southern traditions.

A small group of African American parents, upset when their children had to bypass white schools to reach black ones, sought to challenge state-enforced segregation. Two cases from Delaware ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court as part of Brown v. Board of Education.

Bulah v. Gebhart and Belton v. Gebhart Legal Case Summary

Place: Wilmington County, Delaware

Grievance: Segregated schools far from the homes and neighborhoods of African American children

Plaintiffs: Two mothers of children in the county schools, Sarah Bulah and Ethel Belton, and seven other parents in the community

Decision: A state court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs. An appeal to the state supreme court and the U.S. Supreme Court followed.

The city of Wilmington had a black population of about 17,000 out of 110,000 in 1950. Racial prejudice there was less conspicuous than in the rural counties of Sussex and Kent, but most public facilities were segregated. Discrimination confined most African Americans to service and labor jobs. Despite these obstacles, many African Americans still forged successful careers in the face of racism.

Ethel Louise Belton traveled two hours every day to Howard High School in Wilmington from her community of Claymont. The local white high school offered courses and extracurricular activities unavailable at Howard. Ethel’s mother said, “We are all Americans, and when the state sets up separate schools for certain people of a separate color, then I and others are made to feel ashamed and embarrassed.” Nine other black plaintiffs from Claymont felt the same way and joined her in a lawsuit.

For many years, Howard High School was Delaware’s only business and college preparatory high school for African Americans and served the entire state. With few exceptions, this institution produced the leaders of Delaware’s black community.

Shirley Bulah endured a long daily walk to the Hockessin Colored Elementary School. Her mother, Sarah, asked if her daughter could share a bus with white children or have a separate bus. When her requests were refused, she went to see attorney Louis Redding.

Fearful of change, the pastor of the local African Methodist Episcopal Church opposed Sarah Bulah’s lawsuit, and many black people stopped speaking to her. But her push for school integration had the firm support of the Wilmington branch of the NAACP.

Louis Redding, shown above with Thurgood Marshall, received his law degree from Harvard University. In 1929 he became the first African American to practice law in Delaware, and some 20 years later took on the cases of Bulah v. Gebhart and Belton v. Gebhart. According to one NAACP member, Redding accepted no payment for his services. He directed the chapters instead to raise money for court costs.

In the Delaware cases, Bulah v. Gebhart and Belton v. Gebhart, the NAACP attorneys presented two main arguments: segregated schools harmed black children and violated the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection of the laws. Chancellor Collins Seitz ruled that African American pupils were receiving an inferior education and must be admitted to white schools. But he declined to strike down the principle of separate but equal. That responsibility, he said, belonged to the U.S. Supreme Court. The Delaware Supreme Court upheld his decision.

Both sides were dissatisfied with the state court’s decision and appealed the case. In December 1952, the Supreme Court agreed to hear the case and combined it with the other four.

The Decision: A Landmark in American Justice

Overview

In 1952 the Supreme Court decided to hear school desegregation cases from across the country. When the trial began, everyone in the courtroom knew that the future of race relations in America hung in the balance. The attorneys for both sides believed that law and morality supported their arguments.

A victory by the plaintiffs would mean that the highest court in the land officially endorsed the ideal of equal opportunity, regardless of race. Defeat would mean that the Supreme Court continued to sanction a system of legal segregation based on the notion of racial inferiority.

The Defenders of Segregation

In defense of segregation, South Carolina gathered a team of lawyers that included the state’s top legal officers, headed by one of the most respected constitutional lawyers in the country. Kansas sent a lone reluctant young assistant attorney general.

Citing Plessy v. Ferguson, the defenders claimed that the equal protection clause of the Constitution did not require integration and that the states had already begun a good faith effort to make their facilities equal. Inequality between the races persisted, they explained, because African Americans still needed time to overcome the effects of slavery.

James Lindsay Almond Jr., as state attorney general, was the lead lawyer for Virginia. After receiving his law degree from the University of Virginia, he was a legislator and judge in the city of Roanoke. In his arguments before the Court, he claimed that “with the help and sympathy and the love and respect of the white people of the South, the colored man has risen…to a place of eminence and respect throughout the nation.” From 1958 to 1962 he served as governor of Virginia and remained a leading advocate of segregated schools.

John W. Davis was the lead attorney for South Carolina. A graduate of the Washington and Lee University School of Law, Davis was one of the most distinguished constitutional lawyers in the nation. He had participated in more than 250 Supreme Court cases and appeared before the Court some 140 times. He had been a congressman from West Virginia, the U.S. Solicitor General, ambassador to Great Britain, and in 1924 the Democratic presidential candidate against Calvin Coolidge. In private practice in 1954, he took the case without accepting a fee. An intelligent and elegant advocate for segregation, he died a few months after the decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

Paul E. Wilson argued the case for Kansas. An assistant state attorney general, he was possibly the least enthusiastic of the defenders of segregation. Two of the public schools in Topeka had already desegregated, but it remained his job to defend the laws of his state until the Supreme Court ruled otherwise. A graduate of the Washburn University School of Law, he served two terms as district attorney of Osage County, Kansas. He was later a law professor and published his memoirs of the Brown case, entitled A Time to Lose, in 1995.

H. Albert Young represented Delaware. A graduate of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, he had misgivings about defending legal segregation. As a trial attorney, he advocated for women serving on grand juries. Although he presented a technical defense of Delaware’s segregated school system, he later became the first state attorney general to enforce the Supreme Court’s decision. In 1959 Young entered private practice.

Milton Korman defended the District of Columbia. A graduate of Georgetown University law school, he served as corporation counsel, or chief legal officer, for the D.C. government for several years prior to the Supreme Court case. He claimed that the question of segregation in the city schools was beyond the Court’s jurisdiction and that only Congress had the authority to legislate for Washington, D.C. Later he was appointed to the D.C. Superior Court.

The Segregationists’ Arguments

The case for the defenders of segregation rested on four arguments:

- The Constitution did not require white and African American children to attend the same schools.

- Social separation of blacks and whites was a regional custom; the states should be left free to regulate their own social affairs.

- Segregation was not harmful to black people.

- Whites were making a good faith effort to equalize the two educational systems. But because black children were still living with the effects of slavery, it would take some time before they were able to compete with white children in the same classroom.

The Challengers of Segregation

The civil rights lawyers of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund were younger than their adversaries and had far fewer resources to prepare their cases. Much of their work was done at the law schools of Howard and Columbia universities.

The Plessy v. Ferguson decision, they argued, had misinterpreted the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment—the authors of this amendment had not intended to allow segregated schools. Nor did existing law consider the harmful social and psychological effects of segregation. Integrated schools, they asserted, were a fundamental right for all Americans.

Thurgood Marshall coordinated all of the plaintiff attorneys and presented arguments in the South Carolina case. A graduate of Howard University School of Law, he was the director counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. After the Brown case, he argued several other civil rights cases before the Supreme Court.

From 1961 to 1965 Marshall served as a judge for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and as solicitor general from 1965 to 1967. In that year President Lyndon Johnson appointed him to the U.S. Supreme Court, where he served until his retirement in 1991.

Robert Carter presented the arguments in the Kansas case. He attended Howard University School of Law and completed graduate studies at Columbia University. After encountering widespread racism in the army during World War II, he decided to join the NAACP legal team in 1944 and became Marshall’s key assistant.

From 1956 to 1968 Carter became the general counsel of the NAACP where he continued to be an aggressive advocate for civil rights. In 1972 he was appointed U.S. District Court judge for the Southern District of New York.

Spottswood W. Robinson III argued the Virginia case. A graduate of Howard University School of Law, Robinson entered private practice with his partner, Oliver W. Hill, in 1939. At one point, Robinson and Hill had ongoing lawsuits with 75 school districts. Robinson was appointed dean of Howard’s law school in 1960. In 1966 he was named chief judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals and served until his retirement in 1989.

Louis L. Redding presented a portion of the arguments in the Delaware cases. He graduated from Harvard Law School in 1929 and became Delaware’s first African American attorney. After the 1954 decision, he continued his legal practice in Wilmington and his commitment to defending civil rights cases. For the rest of his life, he was considered Delaware’s leading civil rights attorney.

Jack Greenberg presented part of the arguments in the Delaware cases. He graduated from Columbia Law School in 1948. After Brown, Greenberg eventually replaced Thurgood Marshall as the leading counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

In 1968 he helped found the Mexican-American Legal Defense and Education Fund and since then has helped establish other global humanitarian organizations. In recent years, Greenberg has written several books and is currently professor emeritus at Columbia Law School.

George E. C. Hayes argued the first portion of the Washington, D.C., case. A graduate of Howard University’s law school in 1918, he was for many years a faculty member there, as well as chief legal counsel for the university. He also served on the District of Columbia school board.

After Bolling v. Sharpe, Hayes argued several civil rights and civil liberties cases. In 1954 he represented Annie Lee Moss, a black woman falsely accused of being a Communist, before Senator Joseph McCarthy and the House Un-American Activities Committee.

James Nabrit Jr. argued the second part of the Washington, D.C., case. A graduate of Northwestern University Law School, he joined Howard’s law faculty in 1936 and helped establish the school’s coursework in civil rights law. He served as president of Howard University in the 1960s and deputy ambassador to the United Nations in 1966.

The Integrationists’ Arguments

Lawyers for the plaintiffs relied on legal arguments, historical evidence, and psychological studies:

- In Plessy v. Ferguson, the Supreme Court had misinterpreted the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Equal protection of the laws did not allow for racial segregation.

- The Fourteenth Amendment allowed the government to prohibit any discriminatory state action based on race, including segregation in public schools.

- The Fourteenth Amendment did not specify whether the states would be allowed to establish segregated education.

- Psychological testing demonstrated the harmful effects of segregation on the minds of African American children.

The Justices: Coming to a Decision

The Supreme Court agreed to hear Brown v. Board of Education in June 1952. Deciding the case was difficult from the start. Differing social philosophies and temperaments divided the nine justices. Chief Justice Fred Vinson and several others doubted the constitutional authority of the Court to end school segregation. And the justices worried that a decision to integrate schools might be unenforceable.

In September 1953 Vinson died, and President Dwight Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren as chief justice. His leadership in producing a unanimous decision to overturn Plessy changed the course of American history.

The Court’s Decision

“Segregation of white and colored children in public schools has a detrimental effect upon the colored children. The impact is greater when it has the sanction of the law, for the policy of separating the races is usually interpreted as denoting the inferiority of the Negro group…Any language in contrary to this finding is rejected. We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” – Earl Warren, Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court

Earl Warren wrote the decision for the Court. He agreed with the civil rights attorneys that it was not clear whether the framers of the Fourteenth Amendment intended to permit segregated public education. The doctrine of separate but equal did not appear until 1896, he noted, and it pertained to transportation, not education.

More importantly, he said, the present was at issue, not the past. Education was perhaps the most vital function of state and local governments, and racial segregation of any kind deprived African Americans of equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment and due process under the Fifth Amendment.

Legacy

Achieving Equality

In the mid-1950s Americans remained deeply divided over the issue of racial equality. African Americans pressed to have the Brown decision enforced, and many people were unprepared for the intensity of resistance among white southerners. Likewise, defenders of the “southern way of life” underestimated the determination of their black neighbors.

The African American freedom struggle soon spread across the country. The original battle for school desegregation became part of broader campaigns for social justice. Fifty years after the Brown decision, the movement has come to include racial and ethnic minorities, women, people with disabilities, and other groups, each demanding equal opportunity.

“With All Deliberate Speed”

The Brown decision declared the system of legal segregation unconstitutional. But the Court ordered only that the states end segregation with “all deliberate speed.” This vagueness about how to enforce the ruling gave segregationists the opportunity to organize resistance.

Although many whites welcomed the Brown decision, a large number considered it an assault on their way of life. Segregationists played on the fears and prejudices of their communities and launched a militant campaign of defiance and resistance.

Southern congressmen and governors attacked the Supreme Court’s decision. Through state and local governments and private organizations, white supremacists attempted to block desegregation. People across the country, like these from Poolesville, Maryland, in 1956, took to the streets to protest integration. This kind of opposition exposed the deep divide in the nation, and revealed the difficulty of enforcing the high court’s decision.

Freedom Struggle

The movement for African American civil rights began long before the Brown decision and continues long after. Still, the defeat of the separate-but-equal legal doctrine undercut one of the major pillars of white supremacy in America. In the decades that followed, a heroic ongoing campaign for civil rights has lifted the nation closer to its ideals of freedom.

This NAACP membership application from 1955 celebrated the victory in the Brown case and called on “every freedom-loving American to put into everyday practice both the letter and the spirit” of the Court’s decision.

Some of the first pioneers to cross the color line were young children and teenagers who showed courage beyond their years. President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent U.S. Army troops to enforce school integration in Little Rock, Arkansas. The soldiers escorted nine African American students past threatening mobs at Central High School in September 1957, and newspapers around the world carried photographs of the event.

Norman Rockwell painted The Problem We All Live With in 1964. It depicts federal marshals guarding six-year-old Ruby Bridges on her way to elementary school in New Orleans, Louisiana, in 1960.

On February 1, 1960, four African American college students sat down at a lunch counter at Woolworth’s in Greensboro, North Carolina, and politely asked for service. Their request was refused. When asked to leave, they remained in their seats. Their passive resistance and peaceful sit-down demand helped ignite a youth-led movement to challenge racial inequality throughout the South.

In Greensboro, hundreds of students, civil rights organizations, churches, and members of the community joined in a six-month-long protest. Their commitment ultimately led to the desegregation of the F. W. Woolworth lunch counter on July 25, 1960.

Above, Ezell A. Blair, Jr. (now Jibreel Khazan), Franklin E. McCain, Joseph A. McNeil, and David L. Richmond leave the Woolworth store after the first sit-in on February 1, 1960.

On the second day of the Greensboro sit-in, Joseph A. McNeil and Franklin E. McCain are joined by William Smith and Clarence Henderson at the Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina.

In 1963 about 250,000 Americans of all races joined together in Washington D.C., to stand firm against racial injustice and to demand the passage of national civil rights legislation. At the March on Washington, Martin Luther King proclaimed, “I have a dream,” invoking the hopes of all Americans seeking racial harmony. The official poster, platform pass, and handbill are from the march.

During the late 1960s the tone of the African American freedom struggle changed. An emerging black consciousness movement began to emphasize self-reliance, cultural pride, and a more forceful response to white violence. The Black Panthers is an example of the movement.

Northern and southern whites in large numbers resisted integration at the workplace, in housing, and in schools. In the 1970s court-ordered busing provoked violent reactions as many whites fought to keep black children out of local schools.

On September 1, 1967, Thurgood Marshall took the oath of office to become the first black Supreme Court justice. He wore the above robe during his years on the Court. His appointment was the culmination of a lifetime devoted to using the American legal system to provide equal opportunity for all. Marshall continued that mission until he resigned from the court in 1991. He died on January 24, 1993.

Equality for All

The achievements of the modern black freedom struggle, which followed the victory in the Brown decision, have reverberated throughout society and provide a model for social change. They have given inspiration and encouragement to other Americans fighting for equal rights and access to opportunities regardless of race, ethnicity, religion, age, sexual orientation, or disabilities.

Changing Definitions of Equal Education

Since the 1960s Americans have continued to press for equal educational opportunity. But the meaning of equal opportunity remains controversial. Americans have put their hopes in different and sometimes conflicting approaches to education—further integration, a return to racially separate schools, neighborhood choice, school vouchers, multicultural teaching, or an end to multicultural programs. Through all these years, immigration has continued to change the complexion of classrooms and the expectations of parents and students for American schools.

In addition, schools are influenced by where people choose to live and the use of property taxes to finance public education, among other factors. While not consciously racist, these practices tend to perpetuate segregated and unequal public schools.

“This Court has long recognized that ‘education…is the very foundation of good citizenship’ Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954). For this reason, the diffusion of knowledge and opportunity through public institutions of higher education must be accessible to all individuals regardless of race or ethnicity.” – Sandra Day O’Connor, from the majority opinion

In April 2003 crowds gathered outside the Supreme Court to voice their concerns during the hearing of two cases on affirmative action at the University of Michigan—Gratz v. Bolinger and Grutter v. Bolinger. On June 23, the Supreme Court struck down a special admissions program for the undergraduate school, but upheld a narrower program for the law school. The Court affirmed educational diversity as a goal, and ruled that race, along with many other factors, could be taken into account when considering a student for admission.

Five Communities since Brown

Five communities sent school desegregation cases to the Supreme Court that came to be known collectively as Brown v. Board of Education. Their response to the Court’s decision—from steady integration of public schools to outright defiance—echoed how communities across the country faced the challenges of desegregation. Creating and sustaining equal opportunity in education remains a daily challenge in all American schools.

Clarendon County, South Carolina: In the town of Summerton, African Americans and white children finally began to attend public schools together in 1965, without incident. Today Clarendon County still has a majority black population, and most of the students in public schools are African Americans.

Topeka, Kansas: The public schools began integrating in 1955. In the 1970s black and Latino students staged a strike over a lack of ethnic studies in the curriculum. In 1979 Charles Scott Jr., one of the original Brown attorneys, sued to have the 1954 lawsuit reopened because patterns of segregation had reappeared. In recent years, the city has made progress towards a return to integration.

Prince Edward County, Virginia: The county’s immediate response to desegregation was “massive resistance”—the public schools closed from 1959 to 1964. Excluded from any education, the black children of the county became known as the “crippled generation.” Segregationists throughout the South sent money to support local white students in private schools. Public schools reopened to black students later in the 1960s, and white enrollment has gradually increased since then.

Wilmington, Delaware: School desegregation began in Delaware in the fall of 1952. As a result of white flight from the city, federal courts ordered a massive busing program in 1976. The order sparked bitter opposition. The city’s white population has continued to decline, and the Latino population has grown. Today, the city has a diverse student population and a neighborhood choice plan.

Washington, D.C.: In the nation’s capital, public schools complied with the Supreme Court’s decision in the fall of 1954. But racial tension and white flight to the suburbs persisted. By the 1970s more than 90 percent of the students in D.C. public schools were black. Today Washington, D.C., schools face the same challenges as other urban school systems and have considered some of the same responses—magnet schools, vouchers, and charter schools, among others.

Fifty Years after Brown

Brown v. Board of Education did not by itself transform American society. Changing laws does not always change minds. But today, thanks in part to the victorious struggle in the Brown case, most Americans believe that a racially integrated, ethnically diverse educational system is a worthy goal, though they may disagree deeply about how to achieve it.

“Had there been no May 17, 1954, I’m not sure there would have been a Little Rock. I’m not sure there would have been a Martin Luther King Jr., or Rosa Parks, had it not been for May 17, 1954. It created an environment for us to push, for us to pull.

We live in a different country, a better country, because of what happened here in 1954. And we must never forget it. We must tell the story again, over and over and over.” – U.S. Rep. John Lewis at a ceremony commemorating the 48th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education at Topeka’s First United Methodist Church

When the U.S. Supreme Court struck down school segregation, it advanced the cause of human rights in America and set an example for all the peoples of the world. The American dream of ethnic diversity and racial equality under the law is a dream of liberty and justice for all.

Originally published by the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, reprinted with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.