Examining the way certain materials and motifs acquire sacred meanings and functions.

By The MAP Academy

Open Access Online Platform

Introduction

Across diverse religious beliefs and practices in the Indian subcontinent, the creation of cloth has often been linked to the creation of the universe. These interconnections are reflected most explicitly in the frequently shared vocabulary between textiles and spiritual literature. For instance, the “Sutras” that document Gautam Buddha’s sermons on transcending the cycle of life are named after Suta, the Pali word for yarn. Let’s explore other examples of how textiles have evoked the cosmos through examinations of the origins of cloth, the meditative nature of the weaving process, and the way certain materials and motifs acquire sacred meanings and functions.

At the Cradle of Creation: Divine Fibers

Several communities in the subcontinent associate the origins of fibers, the very building blocks of textiles, with the divine. Such interconnections have been encapsulated in ancient scriptures, mythological narratives, and folktales which have permeated the daily lives and beliefs of people.

In Hindu mythology, for example, the earliest threads known to mankind are believed to have emerged from Lord Vishnu’s navel in the form of a lotus stem. It is unsurprising then that threads have gained special significance within Hindu practices. Several Hindu communities conduct a thread ceremony, a rite of passage for young boys entering adulthood, which involves tying threads across their torsos to symbolize the knowledge acquired from ancient scriptures. It’s important to note here that these rites were exclusive to upper-caste communities, and as a result these threads also served as a marker of one’s status.

Beyond this ritual, other kinds of threads are considered sacred by most Hindu communities. Devotees often tie red threads around their wrists to symbolically carry the blessings of deities, and yellow threads are used in wedding ceremonies as markers of commitment.

Another prominent creation myth, chronicled in oral traditions, narrates the birth of the indigenous silks of Northeast India. According to an Assamese folktale, a widowed mother of three children is banished to a forest. An ascetic takes pity on her and transforms her children into the three kinds of silk that are characteristic of this region—Eri, Muga and Pata. Such stories have shaped regional notions of silk-weaving, where women primarily engage in textile practices and have played a significant role in cementing the importance of textiles in spiritual literature and religious ceremonies.

Weaving God on the Loom: Meditative Processes

Beyond the sacred associations of the creation of fibers, the processes of textile-making are also suffused with spiritualism. Weavers often chant religious verses while engaging in their practice. Some communities believe that their work is intrinsically linked to prana, the force of life, while others compare it to the cyclical nature of time. In fact, the repetitive interlacing of the warp and the weft has been used to describe the unfolding of day and night in ancient Hindu scriptures such as the Rigveda (c. 1500–1000 B.C.E.). The cosmic significance of the weaving process has been explored in spiritual and religious literature across centuries, a pertinent example being that of Kabir’s writings.

The 15th-century poet-saint Kabir, who was born into a Muslim weaving community in Benaras (present-day Varanasi), employed weaving as a metaphor for his devotion to God in his writings. In his poem Weaving your name quoted below, he compares the act of spiritual meditation to the process of weaving. Notice the use of phrases such as “counting God’s name,” “make my garment,” and “combing through the twists and knots of my thoughts” which draw from the images of the systematic and meditative act of interlacing the warp and the weft by hand.

I weave your name on the loom of my mind,

To make my garment when you come to me.

My loom has ten thousand threads

To make my garment when you come to me.

The sun and moon watch while I weave your name;

The sun and moon hear while I count your name.

These are the wages I get by day and night

To deposit in the lotus bank of my heart.

I weave your name on the loom of my mind

To clean and soften ten thousand threads

And to comb the twists and knots of my thoughts.

No more shall I weave a garment of pain.

For you have come to me, drawn by my weaving,

Ceaselessly weaving your name on the loom of my mind.

Kabir, Weaving your name

Kabir’s literary visualizations linking textile-making processes with spiritual and cosmic meditation became culturally embedded. From Kangra school miniatures to Company-style painting, representations in visual art often depict Kabir working on a loom while preaching to his disciples, emphasizing the devotional aspect of weaving.

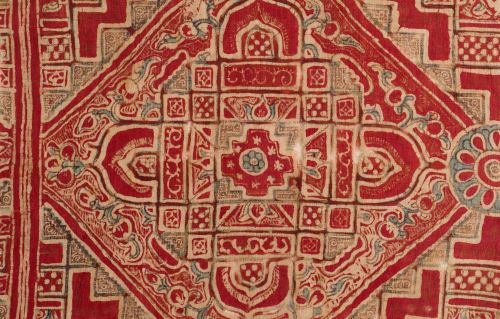

Seeking Infinity through Symmetry: Cosmic Motifs

Across different geographies, cultures, and time periods, artists have used symmetry in their work to explore and interpret abstract cosmological concepts and metaphysical questions of creation and being. From Islamic art and architecture to Hindu art forms like Kolam, one can find the use of symmetry and geometric patterns to symbolize the unity of creation and the order of the universe. In Islamic art, symmetry is achieved through the repetitions of geometric designs, giving the illusion of infinity. Revered for their seeming perfection, one can find these designs in religious textiles such as prayer mats, ritual caps, and headscarves. Within Hinduism as well, symmetric designs invoke the pattern of the cosmos since it is believed that the universe is metaphorically constructed by the intersection of the warp and the weft. Textiles with motifs like the chowk, a grid-like design, are often worn by Hindu devotees for important ceremonies.

Beyond influencing the design vocabulary of sacred textiles, the desire for cosmic wholeness also determines the nature of materials and costumes considered fit for ritual use. Unstitched, “whole” textiles—directly off the loom—that can be draped around the body as saris or dhotis hold religious significance in ancient Hindu scriptures since the ordered universe is envisioned as a continuous fabric woven by the Gods. As the art historian Stella Kramrisch has expressed, “Whether as a cover for the body or as ground for a painting, the uncut fabric is a symbol of totality and integrity. It symbolizes the wholeness of manifestation.”1

Although different communities in the Indian subcontinent interpret and engage with spirituality and cosmology in their own ways, textiles have historically been used across religions to explore the symbolic interconnections of the cosmos and the wonders of the universe. Such beliefs and practices have imbued the production and consumption of textiles with religious and spiritual meanings. They are deeply embedded in a larger understanding of divine creation and cyclical time.

Appendix

Endnote

- Stella Kramrisch, “The Ritual Arts of India,” Aditi The Living Arts of India, edited by Patricia Gallagher (Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1985), pp. 247–69.

Bibliography

- Take a short course on Textiles from the Indian Subcontinent with The MAP Academy

- Jasleen Dhameeja, Sacred Textiles of India (Mumbai: Marg Publications, 2014).

- Jasleen Dhameeja, Textiles and Dress of India: Socio-economic, Environmental and Symbolic Significance (Minnesota: University of Minnesota, 1992).

- Jennifer Harris, 5000 Years of Textiles (London: British Museum Press, 1995).

- Barbara A. Holdrege, “Body Connections: Hindu Discourses of the Body and the Study of Religion,” International Journal of Hindu Studies, volume 2, number 3 (1998), pp. 341–86.

- Ananya Singh, “Mashru Tales of Patan,” National Institute of Fashion Technology (2019).

- Radhika Singh, Suraiya Hasan Bose Weaving a Legacy (New Delhi: Tara India Research Press, 2019).

Originally published by Smarthistory, 11.01.2024, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.