Free speech is not an absolute right.

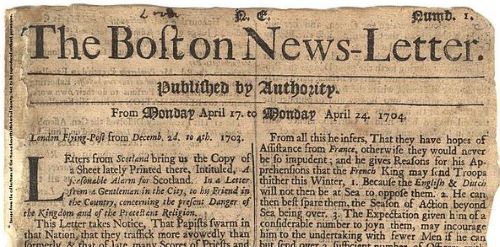

A fundamental revolutionary ideal that emerged in the early American republic is the concept of a free press, but free speech is not an absolute right. Here, we will learn the definitions of free press, libel, slander, and sedition to analyze and evaluate three primary sources from the colonial era.

Freedom of the press evolved in English law as a logical extension of the freedom of speech. Freedom of the press is the right to record and share your knowledge, thoughts, and opinions. Johann Gutenburg’s creation of a movable-type printing press (1440) meant that information could spread much faster and further. Books became less expensive and more people learned to read. To control the flow of information, England, like most other European countries, required that books and pamphlets be submitted to a censor before publication. However, many authors simply ignored this rule and found printers willing to publish their works either for a larger percentage of the profit or because the printer agreed with the ideas set forth in the book or pamphlet. The Bloudy Tenet by Roger Williams (one of the excerpts you will read) was published without approval and copies were later burned by order of Parliament in 1644.

Following the 1660 restoration of King Charles II to the throne, Parliament passed a new sedition law. The act stated that the previous “troubles & disorders did in a very great measure proceed from a multitude of seditious Sermons Pamphlets and Speeches dayly [daily] preached printed and published with a transcendent boldnes [boldness] defaming the Person and Government of your Majestie [Majesty] and your Royall [Royal] Father.” The act declared any attempt to depose the king or overthrow his government in any land under his control by printing, writing, or preaching was punishable by death after conviction at trial.

In 1769, English legal scholar William Blackstone described the concept of free press in the fourth volume of his Commentaries on the Laws of England. Blackstone stated that “The liberty of the press is indeed essential to the nature of a free state: but this consists in laying no previous restraints upon publications, and not in freedom from censure for criminal matter when published.” Blackstone did not think the government could force authors to submit their works to a censor before publication, but that authors did have to accept the legal consequences if they chose to publish something that was “improper, mischievous or illegal.” Blackstone further stated that the punishment of “dangerous or offensive writings” was “necessary for the preservation of peace and good order, of government and religion, the only solid foundations of civil liberty.”

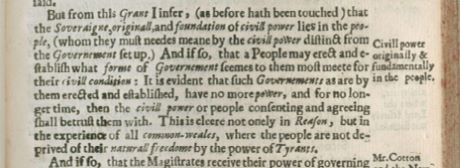

Roger Williams, an English-born Puritan convert, moved to what would become the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1631. Williams spoke out in favor of religious liberty, separation of church and state, and fair dealings with Native Nations. As a result, he was banished from Massachusetts and fled to Narragansett territory where he founded Providence Plantation with the agreement of the Narragansett Nation, who agreed to the settlement in exchange for protection from enemy nations.. While in England to gain a charter for Providence in 1644, Williams wrote The Bloudy Tenent, which set forth his ideas on many aspects of government. The book was not released until Williams left England. Its publication sparked an uproar and it was publicly burned by order of Parliament in July 1644.

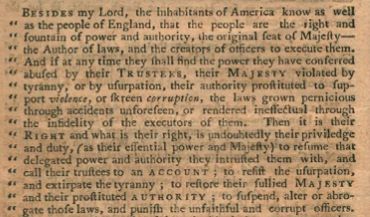

John Allen, a Baptist minister, arrived in Massachusetts in 1772 after publishing a pamphlet titled The Spirit of Liberty in 1770. Allen served as visiting minister of the Second Baptist Church in Boston from November 1772 to July 1773. On December 3, 1772, Allen delivered a Thanksgiving Sermon titled An Oration, Upon the Beauties of Liberty, Or the Essential Rights of the Americans. The sermon was a response to the British government’s investigation into the burning of the Gaspee, a customs enforcement ship, by Rhode Islanders in June 1772. The sermon was later published in seven cities or towns in four separate editions. It ranks as the sixth most popular pamphlet published in British North America between 1765 and 1776.

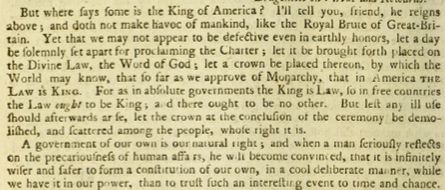

Thomas Paine, born in England in 1737, emigrated from England to the Americas in 1774, just as the tensions between the colonists and the British were coming to a climax. After the events of Lexington and Concord, as well as the first battle of the American Revolution at Bunker Hill, Paine published his pamphlet, Common Sense, in January of 1776. The pamphlet spoke to the American colonists in a common language expressing his ideas on the separation of the American colonies from the British Empire.

Originally published by National History Day, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.