Dead communicating with the living.

By Dr. Mario Erasmo

Cultural Historian

Professor and Head Undergraduate Coordinator

University of Georgia

Introduction

Barlow Bonsall cook @ 1700–1800 for 2 to 3 hours

So reads the text of a tattoo, inside a yellow and orange flame, of Army veteran and cancer survivor Russell Parsons.1 “It’s a recipe,” the 67-year-old widower from Hurricane, West Virginia said. “It’s a recipe for cremation.” Barlow Bonsall, the addressee of the tattoo, is the name of the Funeral Home and Crematorium that will carry out the cremation. In a variation of a will or epitaph designed to identify the deceased or the location of their remains, the unique tattoo ensures that Parsons’s corpse itself will communicate directions for a proper disposal to the crematorium staff. No mention is made of what will happen to his remains after his cremation, rather the words describe the process of cremation that will perish during the cremation process. Since Parsons refers to the tattoo as a “recipe” rather than “directions” for a cremation, the tattoo alludes to recipes found in a cookbook: Parsons humorously self-identifies his future corpse as a meal that will be prepared by a cremating chef. Parsons’s tattoo is now a symbol of his mortality that allows the living to interpret and even commemorate his future death and disposal.

With the exception of Parsons’s tattoo, the bodies of corpses themselves do not normally communicate with those in charge of their disposal. The tattoo, however, is instructive of the interpretative challenge posed by descriptions of cremations in Latin epic. Corpses and their disposal both in the reader’s experience and within a narrative can be read figuratively. We can examine the descriptions of cremation in Vergil and Ovid as elements of a narrative strategy that turns the associative reading experience into a participatory act: Vergil aroused pathos through allusions to pastoral poetry in the cremation of Pallas, whereas Ovid’s absurd treatment of Hecuba’s grief in locating the discovery of her dead son Polydorus at the same time as she prepares to wash her daughter’s corpse subverted the solemnity of funeral ritual into bathos. The displacement of Julius Caesar’s cremation allowed Ovid to make himself the teleological focus of the poem and to express his poetic immortality through allusion to death ritual.

Here, I look at how the reader’s participatory reading experience is further manipulated by authorial agendas that make narratives of funeral rituals even more disturbing and bizarre. Lucan takes Ovid’s cue and exploits the potential inherent in the historical details surrounding Pompey’s death and cremation to turn the reader into a voyeuristic audience of a grotesque spectacle. In the Thebaid, Statius also engages the reader’s familiarity with the topos of cremation to turn it into an intertextual exercise that has little in common with either the ritual itself or epic intertexts. The descriptions of the dual cremations of Opheltes and the serpent, the cremations of Eteocles and Polynices, and the abandoned description of Creon’s funeral and cremation challenge the reader’s familiarity with funerary ritual and previous literary intertexts in a disassociative narrative designed to repel and confuse.

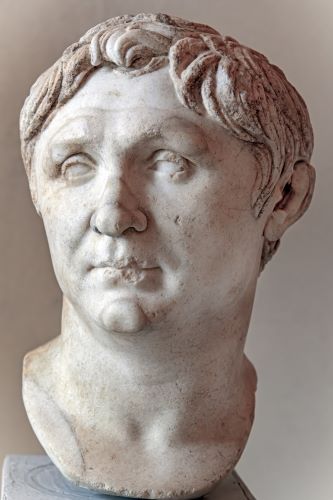

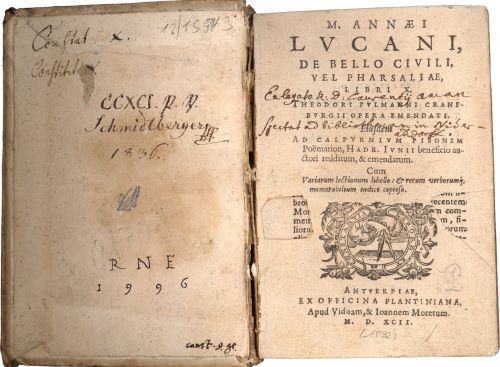

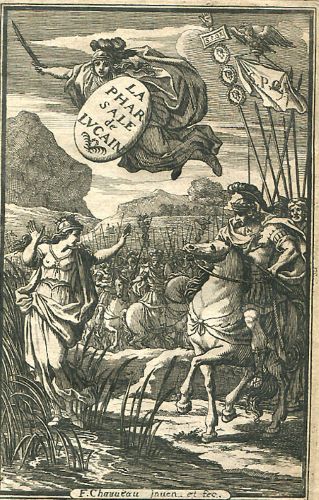

Cremating Pompey in Lucan’s ‘Bellum Civile’

At Bellum Civile 8.692–700, Lucan contrasts the tomb of Alexander the Great and the funeral monuments of the Ptolemies (pyramids and mausolea) with Pompey’s unburied corpse:

litora Pompeium feriunt, truncusque vadosis

huc illuc iactatur aquis. adeone molesta

totum cura fuit socero servare cadaver?2The shores beat against Pompey, his headless corpse

is tossed, here and there, by the shallow waters.

Was it too much trouble to keep the corpse whole

for his father-in-law? (8.698–700)

The restful slumber of Alexander and the Ptolemies focuses by contrast on the abuse suffered by Pompey’s corpse. Lucan elicits pathos with his description of Pompey’s headless body (truncus) being tossed about (huc illuc) by the waves. Pathos, however, turns to voyeuristic fascination when Lucan focuses on the corpse on the beach:

pulsatur harenis,

carpitur in scopulis hausto per vulnera fluctu,

ludibrium pelagi, nullaque manente figura

una nota est Magno capitis iactura revulsi.He is beaten by the sands,

he is torn on the rocks as water is drawn in through

his wounds, he is the plaything of waves, with no

distinguishing feature remaining, the loss of his

decapitated head makes him recognizable as Magnus. (8.708–11)

Pompey is now described as the plaything of waves (ludibrium) as water fills and flows in and out of his body cavity and foreshadows Cordus’ lament over the corpse when his tears fill every wound (8.727) and echo Ovid, Met. 13.490 where Hecuba’s tears fill the wounds of Polyxena’s corpse: huic quoque dat lacrimas; lacrimas in vulnera fundit.3 Ironically, it is because the corpse has no head that it is identifiable as Pompey’s.4 How should the reader interpret this passage which at once arouses sympathy, disgust, and even humor?5

The passage also parallels the well-known passage of Aeneid 2. 557–58, where the headless corpse of Priam evokes the death of Pompey.6 Vergil’s readers, like Aeneas, lose sight of Priam’s corpse before it receives burial.7 In Lucan, however, Book 8 focuses on the murder, decapitation, and burial of Pompey’s corpse. Whereas Vergil elicits pathos in his allusion to Pompey’s death, Lucan, like Ovid, undercuts his narrative with the grotesque and absurd.8 The narrative of Pompey’s decapitation and treatment of his corpse, through allusion to Roman burial ritual, places the reader in the alternating roles of reader/spectator and participant who is drawn to the repulsive details of Pompey’s extended death and burial.9

Text as Corpse

Lucan’s narrative reflects the treatment of Pompey’s mutilated corpse. The description of Pompey’s death and burial extends over Books 7, 8, and 9 and provides thematic unity even while structurally severing the narrative of his unnaturally prolonged death.10 Book 9, furthermore, opens and closes with Pompey’s death.11 Like the decapitation of Pompey, the narrative of the decapitation is, itself, divided into two parts: the actual decapitation (8.663–87) and the preservation of his head (8.688–91). Narrative interruptions, from Pompey’s purported final thoughts (8.622 ff.) to his wife Cornelia’s lament (8.639 ff.), delay the anticipated description of his decapitation and reflect Pompey’s prolonged death. The historical Pompey has become a rhetorical persona whose death can be manipulated to suit narrative purposes.12

Lucan’s narrative focus further reflects his manipulation of details surrounding the death and burial of Pompey. The encounters between Pompey and his killer Achillas and his beheader Septimius evoke a gladiatorial combat that turns the amphitheater into a metaphor for civil war.13 The narrative of the decapitation, furthermore, elicits a voyeuristic response that turns the reader into what Matthew Leigh describes as an amphitheatrical audience.14 The narrative encourages a disengaged emotional response to Pompey’s decapitation, which contrasts with a narrative voice that reserves its sympathy for the poetic outbursts that frame descriptions of Pompey’s murder and mutilation. In other words, the narrator interprets the mutilation of Pompey’s corpse as a moral act while the narrative of the mutilation treats it as a physical one, causing the reader to alternate between feelings of sympathy and disengaged curiosity.15 From an aesthetic perspective, the abuse of Pompey’s corpse can also be read as a damnatio memoriae and a similar viewer response results from a narrative process whereby Pompey’s corpse substitutes for the mutilation of his statue contemporaneously with his murder.16

Lucan anticipates the decapitation by concentrating the reader/audience’s attention on Pompey’s head, with the narrative equivalent of a zoom lens: at 8.613 ff.: after Pompey sees Septimius with knives, he covers his head and remains silent with eyes closed and imagines that it is Caesar rather than Achillas who murders him.17 The effect of this narrative focus is that the reader “sees” the scene more clearly than Pompey himself (613–17):18

ut vidit comminus ensis,|

involvit vultus atque indignatus apertum

Fortunae praebere caput; tum lumina pressit

continuitque animam, ne quas effundere voces

vellet et aeternam fletu corrumpere famam.When he saw the sword nearby,

he covered his face and head, scorning to offer

it bare to Fortune; then he sealed his eyes and

held his breath in case he would pour out his feelings

and ruin his immortal fame with tears.

Pompey is dead to the narrative of his murder in the text before the description of his actual death. It is only when Septimius slits the fabric of his head covering to decapitate Pompey (669), that he “faces” his murderers. Ironically, Pompey is a metaphorical corpse before his actual death. The paradox continues after his death and is reversed: his head is seemingly alive while impaled. From this point, Pompey is reduced to a head with a soon-to-besevered body.19

Text with a Corpse

The description of Pompey’s murder is unexpectedly brief:

sed, postquam mucrone latus funestus Achillas

perfodit, nullo gemitu consensit ad ictum

respexitque nefas, servatque immobile corpus [ . . . ]But after the deadly Achillas dug into his side with his sword,

with no groan did he acknowledge the blow and heed the crime,

but kept his body motionless . . .

Lucan devotes more space to dying, decapitation, and poetic outburts. The quickness of Achillas’ actions contrasts with Pompey’s slow death. Lucan does not state explicitly that both Achillas and Septimius were present during Pompey’s murder and mutilation. Rather Achillas seems to be present for the stabbing while Septimius performs the decapitation.20 The focus in each event, therefore, is on just two combantants, killer and victim, emphasizing the reader’s role as amphitheater audience.

The narrative interruptions following Pompey’s murder make it easy to overlook the fact that Pompey is still alive, both when Lucan attributes final thoughts to him (8.622 ff),21 and during Cornelia’s outburst before leaving her dying husband before the decapitation (8.639–62). Therefore, narrative interruptions that delay the actual moment of Pompey’s death reflect his prolonged agony.22 The prolonged process of the decapitation (diu, 323) mirrors, in turn, the prolonged narrative of Pompey’s death.23

The description of Pompey’s decapitation focuses on the process of the act and Septimius’ difficulty in cutting the head from the body:

At, Magni cum terga sonent et pectora ferro,

permansisse decus sacrae venerabile formae

placatamque deis faciem, nil ultima mortis

ex habitu vultuque viri mutasse fatentur

qui lacerum videre caput. nam saevus in ipso

Septimius sceleris maius scelus invenit actu,

ac retegit sacros scisso velamine vultus

semianimis Magni spirantiaque occupat ora

collaque in obliquo ponit languentia transtro.

tunc nervos venasque secat nodosaque frangit

ossa diu: nondum artis erat caput ense rotare.

at, postquam trunco cervix abscisa recessit,

vindicat hoc Pharius, dextra gestare, satelles.

degener atque operae miles Romane secundae,

Pompei diro sacrum caput ense recidis,

ut non ipse feras?But, while the back and chest of Magnus resonated with the sword,

the august beauty of his sacred features remained and his expression

was at peace with the gods, and those who saw the severed head

claimed that death did not change his appearance and his face.

In the very act of committing a crime, cruel Septimius discovered

a greater one. By tearing the covering, he laid bare the sacred features

of the half-alive Magnus, grabbed the still breathing head and

laid the drooping neck across a bench. Then, for a long time, he cut

the muscles, the veins, and the knotty bones: not yet was it an art to

make heads roll with the sword. But, after the severed neck was

separated from his torso, the subordinate Pharius claimed the right

to carry it in his right hand. You degenerate and a Roman soldier of

an inferior deed, do you sever the sacred head of Pompey with your

polluted sword, in order not to carry it yourself? (8.663–78)

At several points, Lucan includes details that further prolong the narrative by causing the reader to question the accuracy of the account: fatentur (line 666), for example, undercuts the narrator’s credibility as an eyewitness and describes the state of the head at a later time and not at the time of its removal.24 In addition, the detail on the type of weapon used reads more like a footnote to Lucan’s contemporary readers who might wonder why Pompey’s head is cut off with an axe, rather than the sword, which was not yet in current use. The focus on details surrounding the severing of specific body parts makes it easy to get lost in the gore and to forget the larger focus that it is Pompey’s head being severed rather than the head of a sacrificial animal. The description of Pompey’s decapitation is so graphic that one can almost hear it.

It is significant that the actual moment of death is not given. In fact, Pompey is described as half-alive (semianimis, 670), so not only did Achillas not kill him, Pompey is still alive when Septimius beheads him and even, seemingly, when he is impaled. To make the status of Pompey more confusing, the narrator claims that those who saw Pompey’s head noticed no change in his features (665 ff.), before Septimius slit the fabric and actually exposed the head (669). It is the realization of this constantly suffering Pompey, strangely never quite dead or alive, which makes the narrative more disturbing.25 The description of Pompey as semianimis provides a flashback to the beginning of Book 8 when Cornelia faints while Pompey visits her on Lesbos: semianimem . . . eram (8.66). The additional irony that Pompey exiting Italy boasted of “beheading” Crassus (2.546–47) is not lost on the reader.26

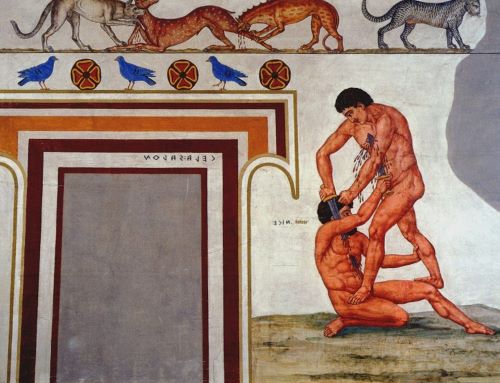

The manipulation of scenery and narrative focus also affect the reader’s response to Pompey’s decapitation.27 The scene evokes the gladiatorial aspect of the famous duel between Manlius Torquatus and the Gaul. Livy (7.10.6), and Claudius Quadrigarius before him, focus more on the provocation and combat, before an audience of Romans and Gauls, than the actual decapitation of the fallen Gaul.28 Evocations of Aeneas’ duel with Turnus are also present in the narrative of Pompey’s decapitation.29 Unlike Vergil, however, who gives a panoramic view of Turnus’ death with the hero himself the object of a sympathetic collective groan, Lucan gives a close-up and even magnified view.30 In Lucan’s narrative, Pompey and the reader hear only the surf and its waves that will continue to ebb and flow after Pompey’s death. The sound and rhythmic movement of the sea contrast with Pompey’s separation and imminent departure from nature, and they seem to mock rather than comfort him in his silence and expectation of death. By alluding to these earlier combats, Lucan identifies Pompey with anti-heroes, but while the allusions encourage us to cheer on the one doing the slaying, the narrative encourages us, as with the death of Turnus and Hector before him, to sympathize with Pompey the slain.

The description of Pompey’s decapitation also contains allusions to funeral rituals. These allusions serve as cultural markers to arouse sympathy and pity through the evocation of rituals known to the reader, but shock when the reader’s experience is not reflected in the text. Since Pompey dies alone, pathos is aroused since no one can catch his last breath with a kiss.31 By alluding to Pompey’s head in terms reserved for imagines: sacros . . . voltus (8.669) before the actual decapitation and sacrum caput (8.677) thereafter, Lucan recalls ancestor masks which, as discussed above, were stored in the atrium of a Roman house and either carried during a funeral pompa or worn by an actor who would imitate the deceased.32 Pompey’s head stands, by synecdoche, for Rome: Lucan claims that the head was one which Rome was once proud to wear (hac facie, Fortunam tibi Romana, placebas (8.686), thus identifying Rome with a mime wearing the mask of a deceased person, perhaps at the funeral of the Republic itself.

Even more disturbing than the comparison of Pompey’s head to an imago is the fact that the reader is still not entirely sure that Pompey is dead, since his head is impaled while seemingly still alive:

impius ut Magnum nosset puer, illa verenda

regibus hirta coma et generosa fronte decora

caesaries comprensa manu est, Pharioque veruto,

dum vivunt vultus atque os in murmura pulsant

singultus animae, dum lumina nuda rigescunt,

suffixum caput est [ . . . ]So that the impious boy would recognize Magnus,

that thick hair revered by kings and the curls handsome

on his noble brow were grabbed with his hand, and on

a Pharian spear, while the face was living and gasps

of breath forced the mouth to murmur, while the

unclosed eyes became stiff, his head was fixed. . . . (8.679–84)

The narrative focus remains Pompey’s head. Vivunt vultus (682) echoes the description of Pompey as semianimis during the decapitation and reminds us of his prolonged death. The emphasis on the still living features of the dying Pompey recalls Sallust’s description of the dying Catiline (Cat. 61.4). As with Lucan’s Pompey, Sallust focuses on Catiline’s face. Catiline’s lifelike features in death, like those of Pompey, are described in terms similar to those of an imago.33 Sallust emphasizes the isolation of Catiline’s cadaver since it is separated from his own men and is now among the enemy, but also the unnaturalness of Catiline’s prolonged life after death. Lucan’s allusion to this passage provides another example of how the narrative encourages the reader to view Pompey in antiheroic terms as it also arouses sympathy for him.

The second part of the narrative that focuses on the decapitation concerns the preservation of Pompey’s head as proof of death. The description of the head’s preservation by embalming is graphic, like its severing, which focuses on the liquids pouring out of the head rather than on the head itself:

nec satis infando fuit hoc vidisse tyranno:

vult sceleris superesse fidem. tunc arte nefanda

summota est capiti tabes, raptoque cerebro

assiccata cutis, putrisque effluxit ab alto

umor, et infuso facies solidata veneno est.Nor was this enough for the unnatural tyrant to look at:

he wants a proof of his crime to survive. Then by the

impious art, the fluid is drawn from the head, the brain

removed, and the skin dried. Putrid fluid poured out from

deep within and his features stiffened when a potion was poured in. (8.687–91)

Lucan refers to embalming as arte nefanda (688), which are related to the arts of Erictho and thus designated as morally suspect. The graphic description suggests that embalming was a procedure outside of Roman funerary custom, thus further alienating the reader as mourner. Descriptions of Poppaea’s embalming also treat the procedure as foreign rather than a customary form of corpse treatment.34 The embalming of Pompey’s head recalls Lucan’s narrative of the beheading (8.665 ff.), while Pompey was seemingly still alive, where Pompey’s facial features are described as fixed in death. The embalming seems unnecessary in a narrative that repeatedly emphasizes the lingering life of Pompey and his head, thus making the graphic description of the embalming seem like an additional outrage to Pompey’s corpse. The textual emendation of placatam for irratam to describe the head (665) alters the scene dramatically: a preserved expression of anger would serve as condemnation for the treatment of his corpse while a peaceful expression would imply Pompey’s acceptance of his fate, perhaps to the chagrin of Septimius and Caesar.35 It is significant that the features of Pompey’s head later change—exactly how is not stated—when the head is brought to Caesar as proof of Pompey’s death (Book 10), providing yet another instance of how Lucan keeps Pompey and his remains seemingly alive beyond the narrative of his death.

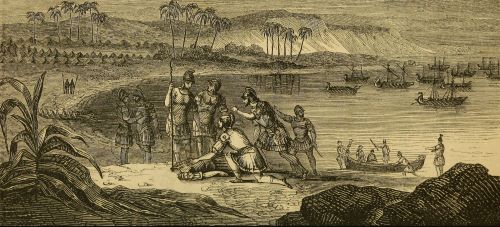

Lucan describes the cremation of Pompey’s corpse in terms which evoke a pauper burial.36 In an extended narrative composed of numerous prayers, the quaestor Cordus retrieves Pompey’s corpse and prays to Fortune to grant Pompey a meager funeral.37 Cordus laments that his burial of Pompey is inexpensive: non pretiosa . . . sepulchra (8.729), with no funeral procession, no funeral oration in the forum, and no military tributes (8.731–35). In other words, Pompey “the Great” is to receive a pauper’s burial: vilem plebei funeris arcam (8.736). The paltry cremation materials contrast with the treefelling passages of Ennius and Vergil, adding to the anti-heroic tone of the passage:38

non pretiosa petit cumulato ture sepulchra

Pompeius, Fortuna, tuus, non pinguis ad astra

ut ferat e membris Eoos fumus odores,

ut Romana suum gestent pia colla parentem,

praeferat ut veteres feralis pompa triumphos,

ut resonent tristi cantu fora, totus ut ignes

proiectis maerens exercitus ambiat armis.

da vilem Magno plebei funeris arcam

quae lacerum corpus siccos effundat in ignes;

robora non desint misero nec sordidus ustorYour Pompey, Fortune, does not seek a precious pyre with incense

heaped up, nor that the thick smoke should carry eastern scents

from his body to the stars, nor that dutiful Roman necks should bear

their parent, nor that his funeral procession should display his triumphs

of old, nor that the Fora should echo with sorrowful song, nor that the

whole army in mourning should lay down their arms and walk around

the flames. Give to Magnus the cheap coffin of a plebeian funeral

which will pour out the mutilated body onto the thirsty flames;

but do not let the miserable one lack timber or a cheap corpse-burner. (8.729–38)

Cordus proceeds to give Pompey’s headless corpse a partial cremation by stealing the burning embers from someone else’s bier:39

Sic fatus parvos iuvenis procul aspicit ignes

corpus vile suis nullo custode cremantis.

inde rapit flammas semustaque robora membris

subducit. ‘quaecumque es,’ ait ‘neglecta nec ulli

cara tuo sed Pompeio felicior umbra,

quod iam compositum violat manus hospita bustum,

da veniam: si quid sensus post fata relictum est,

cedis et ipsa rogo paterisque haec damna sepulchri,

teque pudet sparsis Pompei manibus uri.’

sic fatus plenusque sinus ardente favilla

pervolat ad truncum, qui fluctu paene relatus

litore pendebat. summas dimovit harenas

et collecta procul lacerae fragmenta carinae

exigua trepidus posuit scrobe. nobile corpus

robora nulla premunt, nulla strue membra recumbunt:

admotus Magnum, non subditus, accipit ignis.Thus having spoken, the youth saw small fires in the distance,

with no guard, cremating a body worthless to its family.

Next, he seized fire and half-burnt timbers from under the limbs.

“Whoever you are,” he said, “abandoned shade and dear to none of

yours but luckier than Pompey, forgive that a stranger’s hand

violates your assembled pyre: if there is any feeling left after death,

give over these things from your pyre and these losses from your grave

and feel shame that you were burning while the shades of Pompey lie

scattered.”

Thus he spoke and with his cloak full of burning ashes,

flew to the torso which, almost carried off by the waves,

was hanging on the shore’s edge. He moved aside the topmost sand

and shaking, placed into the shallow pit the fragments of a broken boat

found at a distance. No timbers press against his noble body,

no limbs lie on a pile: a fire placed beside, rather than beneath, burns

Magnus. (8.743–58)

Pompey’s pauper burial is all the more shocking because of the narrative that barely makes the pauper burial happen: while Cordus was stealing wood from someone else’s pyre, which may be contaminated with his ashes, a wave almost carried away his torso;40 the pyre is not constructed of wood; the cremation pit is barely drawn into the sand; and the fire that should be burning below the corpse actually burns beside it.

The narrative calls attention to Cordus’ gathering of wood and his preparation of the pyre in a way that evokes Metamorphoses 8.640–45 when Philemon and Baucis entertain the gods, in particular, Baucis’ preparation of a fire with which to cook the meal.41 By connecting Pompey’s pyre with Baucis’ hearth, Lucan presents Pompey as the victim of fate who is offered to the gods as reproach for the inhumane treatment suffered by his corpse. The cannibalistic implications are reminiscent of Seneca, Thyestes 760 ff., where Atreus cuts off the limbs of Thyestes’ sons and boils their body parts. The actual description of the cremation is brief compared to the narrative of its preparation, but the reference to Magnus personifies Pompey’s corpse in an unsettling way:

excitat invalidas admoto fomite flammas.

carpitur et lentum Magnus destillat in ignem

tabe fovens bustum.He rouses the weak flames by adding fuel.

Magnus is reduced and drips into the slow fire,

feeding the pyre with his melting flesh. (8.776–78)

The setting sun interrupts the order of Pompey’s cremation (ordine rupto / funeris, 779–80), and coincides with the glowing of the ashes as Cordus gathers the bones for burial.

The cremation, however, is not complete as sinews and marrow cling to the bones:

semusta rapit resolutaque nondum

ossa satis nervis et inustis plena medullis

aequorea restinguit aqua congestaque in unum

parva clausit humo.42He seized the half-burnt bones, not sufficiently

separated from the muscles and full of burned marrow,

extinguished them with sea water, piled them up

and covered them with a bit of earth. (8.786–89)

Reflecting the simple burial, few words are devoted to its narrative. Pothinus gives further details about the small mound’s appearance when he points it out in Book 10:

aspice litus,

spem nostri sceleris; pollutos consule fluctus

quid liceat nobis, tumulumque e pulvere parvo

aspice Pompei non omnia membra tegentem.Look at the shore, the pledge of our crime; consult

the polluted waves

about what we can do, and look at the grave made from meager

dust, not covering all of Pompey’s limbs. (10.378–81)

The description of the grave can be interpreted two ways: that it was insufficient to cover all of Pompey’s remains and barely in compliance with burial ritual or that the insufficient burial did not contain all of Pompey’s remains since it does not contain his head (non omnia membra, 381). The reminder that Pompey is not all there suggests that his corpse has no identity like the corpse whose embers Cordus stole.

The narrative of Pompey’s cremation extends to Book 9 with the apotheosis of Pompey’s soul, lamentation for his death, and Cornelia’s substitute cremation of Pompey’s clothing. Pompey’s soul rises from his ashes and laughs at the abuse inflicted on his corpse as he flies over the battlefields of Pharsalus (9.1–18):

At non in Pharia manes iacuere favilla

nec cinis exiguus tantam compescuit umbram:

prosiluit busto semustaque membra relinquens

degeneremque rogum sequitur convexa Tonantis.

qua niger astriferis conectitur axibus aer

quodque patet terras inter lunaeque meatus,

semidei manes habitant, quos ignea virtus

innocuos vita patientes aetheris imi

fecit et aeternos animam collegit in orbes.

non illuc auro positi nec ture sepulti

perveniunt. illic postquam se lumine vero

implevit, stellasque vagas miratus et astra

fixa polis, vidit quanta sub nocte iaceret

nostra dies risitque sui ludibria trunci.

hinc super Emathiae campos et signa cruenti

Caesaris ac sparsas volitavit in aequore classes,

et scelerum vindex in sancto pectore Bruti

sedit et invicti posuit se mente Catonis.But his spirit did not lie among the Pharian embers

nor did the meager ash confine such a shade:

it leapt up from his grave and leaving his half-burnt limbs

and the unworthy pyre, heads for the Thunderer’s vault.

Where the dark air is connected to the star-bearing heavens

in the regions between the earth and the paths of the moon,

semidivine shades live, those whom innocent in life, their

fiery virtue has made able to endure the lower aether and

has gathered their spirits among the eternal spheres.

Not there do people laid in gold or buried with incense

come. There, after Pompey’s spirit filled itself with true light,

and having marveled at the wandering planets and the stars

fixed to the heavens, it saw how much our daylight lies under

the night and it laughed at the insults to his torso.

From here, it flew above the Emathian fields, the standards

of Caesar and the fleet arrayed in the sea and as an avenger

of crime, it settled in the sacred breast of Brutus and positioned

itself in the mind of invincible Cato.

Pompey’s apotheosis takes place much faster than the narrative of his lingering death and abuse of his corpse and Pompey’s soul takes on a vigor that contrasts with his former passivity. A temporal adjustment is needed since his corpse was abused before its cremation. The reader, therefore, must now imagine that Pompey’s soul (even prior to his cremation) was witnessing events from Book 8, like his murder and abuse of his corpse, with the reader unaware of his soul’s presence. From a semiotic perspective, Pompey was an audience to his own audience of events on earth, watching himself watching events of his murder unfold, watching his corpse being decapitated and abused (now referred to as a spectacle: ludibria), watching Cordus’ hasty funeral and the cremation of his remains from which his soul arose. Pompey continues to be both dead and alive and his remains both separated, while his head awaits cremation, and reconstituted as his soul soars over the earth as a witness and audience of events, past and current. Thus, Pompey emerges as a self-representational character, changing his role from character to author, as he provides closure to the narrative of his death and disposal denied to him by Lucan. The description of his apotheosis becomes his own sphragis on Lucan’s text: Pompey has achieved immortality as both a character and author. Like Horace in Ode 2.20 where the poet soars as a swan making Augustus’ empire the boundaries of his, the poet’s, fame, Pompey surveys the geographic and poetic boundaries of his own renown.

Despite his apotheosis and self-asserted self-representation in the text, Lucan regains authorial control as the text returns to Pompey’s corpse and his second (symbolic) cremation. In a gesture reminiscent of Dido in Aeneid, Book 4. 642 ff., Cornelia burns clothing (Iliacas vestis, 648) and other items belonging to Pompey, but absent is any allusion to the effigy of Aeneas which Dido had placed on her pyre:

sed magis, ut visa est lacrimis exhausta, solutas

in vultus effusa comas, Cornelia puppe

egrediens, rursus geminato verbere plangunt.

ut primum in sociae pervenit litora terrae,

collegit vestes miserique insignia Magni

armaque et impressas auro, quas gesserat olim

exuvias pictasque togas, velamina summo

ter conspecta Iovi, funestoque intulit igni.

ille fuit miserae Magni cinis. . . .But all the more do they wail and redouble the

strikes against their breasts when they see

Cornelia leaving her ship, worn out by tears and

disheveled, hair loosened across her face.

When at first she arrived on the shores of allied land,

she collected the clothes and insignia of wretched Magnus,

his weapons and armor, impressed with gold, which he

once had worn and his embroidered togas, garments seen

three times by highest Jove, and she placed them on the

funeral fire. To the pitiable woman, that was the

ash of Magnus. (9.171–79)

Cornelia does not perform an actual cremation, but rather a substitute cremation since Pompey’s trunk has already been burned. But by including a second cremation of Pompey, Lucan makes the reader mourn again. The prolonged and repetitive treatment of the corpse reflects the prolonged narrative of his decapitation and lingering death (or rather the lingering life attributed to his head).

While Cornelia is performing her substitute cremation, Pompey’s head is apparently en route to Caesar who has arrived in Egypt. When Pompey’s head is brought to Caesar, he first treats Pompey as a foe and then as a kinsman as he sheds crocodile tears (9.1064–1104). When Pompey’s head is revealed, the face has been changed in death and its features both attract and repel Caesar’s gaze:

Sic fatus opertum

detexit tenuitque caput. iam languida morte

effigies habitum noti mutaverat oris.

non primo Caesar damnavit munera visu

avertitque oculos; vultus dum crederet, haesit;Thus he spoke and uncovered and

held up his head. Already, the head, languid

in death, had changed the appearance of his familiar

features. At first, Caesar did not condemn the gift

nor turn his eyes from the sight; he stared until

he believed it was his face. (9.1032–36)

The ability of Pompey’s face to change features again suggests that he is still not dead and that he is playing dead like the dying Catiline in Sallust. In this case, however, the moral consequence of the ambiguity falls on Caesar, rather than Pompey, whose head reminds the reader (and Caesar in the text) of Pompey’s brutal murder and decapitation. The staging of the scene also reinforces Caesar’s guilt: Pompey’s head becomes the narrative focus as we watch Caesar looking at Pompey’s head as he scrutinizes the features for a long time. Surprisingly, Lucan does not tell us whether Pompey was looking back at Caesar since the text does not make explicit whether or not Pompey’s eyes are shut. Caesar’s reluctance to look at Pompey’s head when it is shown to him reflects a merging or fusion of the amphitheatrical audience between reader and epic character. Should the reader continue to follow Caesar as he looks away from the head or should the reader keep looking at Pompey? The reader, therefore, remains voyeuristically involved in the narrative.

Caesar immediately plans a proper burial for Pompey’s head which is to be interred with the ashes of his cremated remains:

vos condite busto

tanti colla ducis, sed non ut crimina solum

vestra tegat tellus: iusto date tura sepulchro

et placate caput cineresque in litore fusos

colligite atque unam sparsis date manibus urnam.

sentiat adventum soceri vocesque querentis

audiat umbra pias.Bury the head of so

great a leader in a grave, but not only so that the

earth can conceal your crimes: offer incense on a

proper grave and revere the head and after you have

collected all of his ashes spread along the shore,

place the scattered shades into a single urn. Let his

shade sense the arrival of his father-in-law and let it hear

his pious complaints. (9.1089–95)

Caesar’s call to reassemble Pompey’s corpse also functions at the symbolic level: now that Caesar has confirmed the identity of the head and acknowledged the death of Pompey, he proposes to transfer Pompey’s identity onto his remains. By giving directions to collect the ashes of Pompey’s trunk (cineresque in litore fusos / colligite, 1092–93), Caesar ignores Cordus’ earlier pauper burial of Pompey’s remains and suggests that he alone would be providing a proper burial. Caesar’s proposal also represents a variation of the Roman burial ritual of ossilegium whereby a severed body part, normally a finger, was placed in an urn with the cremated remains in connection with Theseus’ gathering of Hippolytus’ remains.43 Since Caesar does not suggest cremating the head, the reader is left with the image of Pompey’s head sitting in an urn. In fact, Lucan does not tell us whether Caesar’s plans for a burial were carried out, so Pompey’s corpse remains unassembled in the poem. As with Cornelia’s substitute cremation, Caesar’s planned burial of all of Pompey’s remains further prolongs the reader’s mourning process as Lucan, again, denies both characters and reader any closure to Pompey’s death and burial.

Corpse with a Text

When Cordus provides Pompey’s remains with a pauper burial, he marks the spot with a stone (8.789–93):

tunc, ne levis aura retectos

auferret cineres, saxo compressit harenam,

nautaque ne bustum religato fune moveret

inscripsit sacrum semusto stipite nomen:

‘hic situs est Magnus.’Then, so that a gentle breeze

would not uncover and carry off the ashes,

he weighed the sand down with a rock, and

to prevent a sailor from disturbing the grave

with a mooring rope, he wrote his sacred name

with a half-burnt stick: “Here lies Magnus.”

The epitaph which Pompey receives hardly befits his enormous fame and the one word Magnus must suffice to identify the remains of this great Roman. Unlike Priam’s corpse in Aeneid, 2.558 which is described as nameless (sine nomine corpus), Pompey’s corpse is identified by the epitaph, but there is an irony in referring to him by his cognomen alone that goes beyond referring to someone as a great person whose name actually was “great.” On the one hand the reference is flattering: this person is so great that everyone knows his actual name; but it is also unflattering. If this person is so great, why is he buried in such a simple way in such a strange location?

There is a sense of urgency connected with the burial: Cordus writes Pompey’s name onto a rock with a charred stick (semusto stipite, 792); therefore, the inscription is a highly perishable and time-sensitive grave marker, especially considering its proximity to water. In addition, the posting of an epitaph identifying the remains as those of Pompey recalls the description of the impaling of his head (suffixum caput est, 684). Since the epitaph is only for Pompey’s trunk, however, both the epitaph and the allusion to his impaling serve as substitutes for his head while simultaneously calling greater attention to its absence.

The epitaph Hic situs est Magnus (8.793) serves as both grave marker and text marker: hic (793) is locative and indicates that the corpse is no longer rolling in the surf. But where exactly is hic? Unlike burials along the Via Appia in Rome, for example, Pompey’s tomb lies somewhere along the shore in a foreign land. Lucan tells us that the corpse is buried hic, but we know that the head is en route to Caesar as Cordus performs his pauper burial and that, at least in the poem, Pompey’s head is not reassembled to his trunk. Therefore, the epitaph misrepresents the truth about its location and its contents and the ambiguity further prolongs the abuse suffered by Pompey’s still improperly buried corpse.

In a final description of Pompey’s tomb (8.816–22), Lucan notes that no description of Pompey’s life appears, other than his name which used to adorn temples and arches.44 The epitaph simply informs the passerby or reader that Pompey’s remains were located at the spot marked by the epitaph without giving any further information about his identity or life accomplishments. The narrator’s lament of the lack of biographical details serves as substitution for information normally contained in an epitaph. Lucan, therefore, severs a traditional epitaph, by separating references to Pompey’s name from his accomplishments as an allusion to the actual severing of his head.

Cordus as epitaph writer parallels Lucan as narrator.45 Both authors mark the death of Pompey but since Cordus writes a highly perishable inscription, like Parsons’s cremation tattoo intended to burn with his body, it is Lucan’s verse that will immortalize Pompey:

haec et apud seras gentes populosque nepotum,

sive sua tantum venient in saecula fama

sive aliquid magnis nostri quoque cura laboris

nominibus prodesse potest, cum bella legentur,

spesque metusque simul perituraque vota movebunt,

attonitique omnes veluti venientia fata,

non transmissa, legent et adhuc tibi, Magne, favebunt.Even among later peoples and the descendants of grandsons,

these events, whether by their own fame they survive into the future

or whether the care of my labor can be useful to great names, will

instill hope and fear and, at the same time, doomed prayers when battles

are read, and all will be amazed when they read about events, as

forthcoming

rather than in the past, Magnus, and they will still be favorable to you. (7.207–13)

Lucan’s readers will read Pompey as they read his poem. Therefore, the poet’s conceit and his future success are tied to his narrative of Pompey. The poet’s immortality is also related to Pompey’s catasterism in Book 10: Pompey is immortalized in a poem that seeks immortality through a narrative of his death and burial.

The poet’s allusion to death ritual and poetic (self) referencing, however, does not end in Book 10. Tacitus’ description of Lucan’s own death provides an epilogue to the Bellum Civile in which Lucan continues to engage his amphitheatrical audience:

Exim Annaei Lucani caedem imperat. is profluente sanguine ubi frigescere

pedes manusque et paulatim ab extremis cedere spiritum fervido adhuc

et compote mentis pectore intelligit, recordatus carmen a se compositum

quo vulneratum militem per eius modi mortis imaginem obisse tradiderat,

versus ipsos rettulit eaque illi suprema vox fuit.46Next he [Nero] ordered the death of Annaeus Lucanus. When he felt that

the loss of blood was beginning to turn his feet and hands cold and his life

gradually leaving his extremities, although there was still heat in his heart

and a presence of mind, he remembered a poem, written by himself, that

told how a wounded soldier died in a way similar to his own death and

recited them and these were his very last words. (Annales, 15.70.1)

According to Tacitus, Lucan cites his own verses with his dying breath in a narrative that seems to satirize the unnaturally prolonged death of Pompey (paulatim). We are not told whether Lucan quoted from his Bellum Civile, only that he quoted lines from a carmen which he had given to one of his literary characters—a dying soldier. Suetonius, however, does not mention the recitation of lines, only that Lucan wrote directions for the editing of his poetry.47 In Tacitus’ more dramatic version, Lucan rhetoricizes his own death by assuming a fictional identity as a response to his forced suicide. Fiction and reality blend when both actor and character die simultaneously, but reality reasserts itself with the poet’s final breath since the corpse, stripped of its fictional identity, belongs to the poet Lucan. In framing his death in either literary or dramatic terms, Lucan (through Tacitus’ narrative) also turns his witnesses into readers/audience members to create a theater of death that reverses the role played by his epic readers. Lucan’s epic readers now mourn the death of the poet, as the poet, metaphorically, becomes his poem.

Lucan’s narrative of Pompey’s death and burial, therefore, confounds the reader’s role as mourner. The narrative elicits pathos for the grotesque treatment of Pompey’s corpse and its allusion to Roman funerary ritual, but it also exasperates the reader when it frustrates the reader’s experience of those rituals to produce the double outrage that results from imagining Pompey’s death and reading Lucan’s account of it. Pompey’s lingering death, the lifelike appearance and behavior of his corpse, and the repeated funerary rituals imagined or performed on his remains deny closure to both Lucan’s characters and his reader/audience.

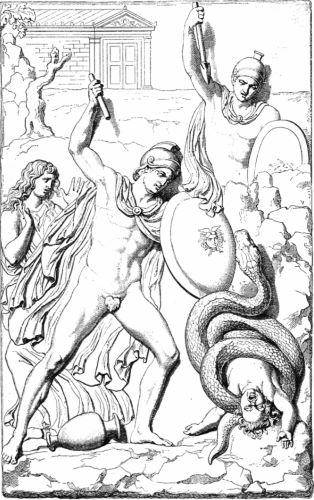

The Cremation of Opheltes in Statius’ ‘Thebaid’

The Thebaid contains two major cremation episodes in Books 6 and 12: Book 6 describes the cremation of the infant Opheltes, the son of Eurydice and Lycurgus of Thebes, and a second pyre to expiate the death of the serpent that killed Opheltes; Book 12 contains the cremation and burial of Theban dead, including the cremations of Polynices and Eteocles. Statius’ narrative of funerary ritual is complex in its intertextuality with the descriptions of cremations and burials found in preceding epics. A reader familiar with Ovid’s manipulation of Hecuba’s grief and Lucan’s maltreatment of Pompey’s corpse could expect the grotesque elements to rise exponentially, but Statius takes his narrative in another direction. The fictive reality of the Thebaid does not allude to actual funerary ritual familiar to his readers, but rather to literary descriptions of cremations and burials found in Vergil, Ovid, and Lucan.48 Like Ovid, Statius uses funerary ritual to comment on the writing process and his role as poet.

In Book 6, Statius alludes to the cremation of Pallas in his description of Opheltes’ cremation and to the cremation of Misenus in his description of the pyre dedicated to the serpent. But he adds grotesque and absurd elements found in the Metamorphoses, the Bellum Civile, and Senecan drama to his Vergilian intertexts to create an original description of Opheltes’ funeral and cremation.49 The addition of new intertexts, such as Catullus and Seneca, signals Statius’ intent to engage the reader’s recognition of elements from the epic trope of cremations, but also to engage the reader in a complex narrative strategy: the text constantly varies its thematic focus and questions its own emphasis on various episodes, such as the excessive ceremony and intertextual details that accompany Opheltes’ cremation.

The narrative of Opheltes’ cremation is unique. The child was in the care of Hypsipyle of Lemnos, who arrived in Thebes as a fugitive for sparing her father when the island’s women were slaughtering all male inhabitants, but was killed by a serpent while Hypsipyle, forgetful of him, was narrating the details surrounding events on Lemnos.50 The description of the sleeping child foreshadows his death and burial:

ille graves oculos languentiaque ora comanti

mergit humo fessusque diu puerilibus actis

labitur in somnos, prensa manus haeret in herba.51He buries his heavy eyes and drooping head into

the leafy soil and, tired from too much child’s play,

he sinks to sleep and his hand holds grass tightly clutched. (5.502–4)

After the serpent is killed, Hypsipyle discovers the mangled corpse of Opheltes, which evokes the corpse of Hippolytus in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (15.529: unumque erat omnia vulnus), Seneca’s Phaedra (1265–66: hoc quid est forma carens / et turpe, multo vulnere abrumptum undique?), and the corpse of Astyanax in Seneca’s Troades (1116–17: iacet / deforme corpus):

non ora loco, non pectora restant,

rapta cutis, tenuia ossa patent nexusque madentes

sanguinis imbre novi, totumque in vulnere corpus.No face or chest were left in place,

skin torn away, thin bones lay bare and sinews

are soaked in fresh currents of blood—the whole

body is one wound. (5.596–98)

The placement of Opheltes’ corpse among so many intertexts illustrates the complexity of Statius’ narrative and raises the expectation that the cremation and burial of the infant’s corpse will also be linked with these same intertexts.

Many details of Opheltes’ cremation, however, depart from these initial intertexts to allude to the cremation of Pallas in the Aeneid. What makes his cremation even more unusual than the fact that an infant receives a funeral worthy of a warrior, is that it is accompanied by a second and contemporaneous cremation designed to expiate any evil resulting from the killing of the serpent rather than to cremate an actual corpse. Variation on a theme is accompanied by reduplication of that variation. The allusion to intertexts followed by reader frustration at having been misled by expectations of familiarity when the narrative diverges from the trope is part of Statius’ narrative strategy and allows him, at once, to allude to and to vary the epic trope of funerals.

The cremation of Opheltes is the narrative focus of Book 6 and he is honored with a cremation worthy of a seasoned warrior:

Tristibus interea ramis teneraque cupresso

damnatus flammae torus et puerile feretrum

texitur: ima virent agresti stramina cultu;

proxima gramineis operosior area sertis,

et picturatus morituris floribus agger;

tertius adsurgens Arabum strue tollitur ordo

Eoas complexus opes incanaque glebis

tura et ab antiquo durantia cinnama Belo.

summa crepant auro, Tyrioque attolitur ostro

molle supercilium, teretes hoc undique gemmae

irradiant, medio Linus intertextus acantho

letiferique canes: opus admirabile semper

oderat atque oculos flectebat ab omine mater.

arma etiam et veterum exuvias circumdat avorum

gloria mixta malis adflictaeque ambitus aulae,

ceu grande exsequiis onus atque immensa ferantur

membra rogo, sed cassa tamen serilisque dolentes

fama iuvat, parvique augescunt funere manes.

inde ingens lacrimis honor et miseranda voluptas,

muneraque in cineres annis graviora feruntur;

namque illi et pharetras brevioraque tela dicaret

festinus voti pater insontesque sagittas;

iam tunc et nota stabuli de gente probatos

in nomen pascebat equos cinctusque sonantes

armaque maiores exspectatura lacertos.

[†spes avidi quas non in nomen credula vestes†|

urgebat studio cultusque insignia regni

purpureos sceptrumque minus, cuncta ignibus atris

damnat atrox suaque ipse parens gestamina ferri,

si damnis rabidum queat exsaturare dolorem.]Meanwhile, the bier condemned to burn and the child-sized litter

|are woven with gloomy branches and tender cypress;

the lowest part of the bier is lush with rustic greens;

the area closest is more ornate with woven grass,

and the pile is decorated with flowers about to die;

the third level rises piled with Arabian spices encircled by

Eastern riches and clumps of white incense and cinnamon

from the time of Belus. The top rustles with gold and a

soft covering made with Tyrian purple is raised high;

here and there polished gems sparkle within the acanthus

border, Linus is woven and the hounds that brought him death:

his mother always hated this admirable work and always

turned her eyes away from the omen. Even weapons and the

armor of ancient ancestors are spread around the pyre,

the glory of the distressed house mixed with its misfortunes,

|just as though the procession were carrying a heavy burden and|

huge limbs to the pyre; yet even his empty and immature fame

is a comfort to the mourners and Opheltes’ tiny shade is magnified

by the funeral. Then comes the great honor of tears, a pitiable

delight as gifts greater than his years are carried to the pyre;

For his father, hasty in his vow, had set apart for his son|

quivers, small spears and innocent arrows; he was even rearing

in his name excellent horses from the famous herd of his stable,

clanging belts and armor more suited to fuller shoulders.

†Empty hopes: what cloaks in his name, hopeful,†

in her zeal, did she not hasten, the emblems of royal ritual,

purple robes and a miniature scepter? All his fierce father himself

condemns to the black flames and even his own insignia to be

brought out if only to satiate his rabid grief by their loss.

Many details of Opheltes’ bier (torus . . . feretrum, 6.55) allude to the cremations of Pallas and Misenus, but Statius goes beyond his Vergilian intertexts to make the infant’s funeral at once exotic and excessive. The bier is childlike in size and is composed of gloomy branches and cypress shoots. While cypress trees surrounded the pyre of Misenus (Aen. 6.216–17), here cypress trees comprise the actual bier—funereal symbol has become a funeral accessory. The bier rests on top of four layers that are unique and prioritized: the higher the layer, the more expensive the offering.52 The prioritized objects also reflect a metaphorical transition: from bucolic innocence to civilized materialism with Opheltes’ body closest to most expensive items. From a sensory perpective, there is a transition from smell (cypress to incense/spices) to sight (jewels).

The bottom two layers evoke bucolic imagery and are reminiscent of Pallas’ cremation: the tender shoots reflect the age of the deceased but, like the tender shoots of Pallas’ pyre, they are impractical from a cremation point of view. Pallas was placed on top of a rustic bier (hic iuvenem agresti sublimem stramine ponunt, 11.67) but rustic greens comprise the lowest level of Opheltes’ bier: ima virent agresti stramina cultu (6.56). Shared language connects the two biers but Opheltes’ corpse does not share the same proximity with rustic foliage as did Pallas. Statius further changes the bucolic imagery of Pallas’ cremation: whereas Pallas was compared to a cut flower (Aen. 11. 68–71) to emphasize his youth, flowers that are soon to die decorate the second layer together with grassy wreaths. As with the cypress trees, funereal symbol has become a funeral accessory.

The third layer of Opheltes’ bier is composed of incense and exotic spices that separate the bucolic layers from the fourth layer, a canopy of Tyrian purple (6.62–63) which is decorated with gold and jewels. Prior to his lighting of the pyre, Lycurgus places locks of his cut hair over Opheltes’ face so presumably Opheltes’ body lay on top of layer 3 but below layer 4, therefore among the most valuable of the objects. The description of the canopy is unique in its intertextuality: the reference to Tyrian purple evokes Dido’s cloak which was placed on Pallas’ corpse (Aen. 11.74–75). It is only with the description of this fourth layer that the reader realizes that Statius has deconstructed Dido’s cloak for the third and fourth layers of Opheltes’ pyre. The canopy is decorated with a representation of Linus and the hounds who killed him (6.64–66). Allusion to Linus connects Eurydice with a mythological intertext of a youth killed by animals, but the narrative also makes it clear that this is not the first time that she has seen the canopy since it was hateful to her even before Opheltes’ cremation and she interpreted the myth depicted on it as a bad omen for her own child. The canopy has served its intertextual purpose and now burns with her child.

Statius contrasts the size and age of Opheltes with the excessive honors of his cremation. Mourners add the armor of the infant’s ancestors onto the bier (now described as rogus at 6.70) to make it bigger and heavier (6.67–70), which also seem to make Opheltes’ shade increase in size (6.71). Lines 79–83 are marked as spurious in some editions, but as they now stand, Opheltes’ father increases the number of items placed on the pyre that contrast with the age and military experience of the boy. Mourners become actors as they treat the infant’s corpse as though he were an adult deserving of the military honors of his ancestors. Transferring future accomplishments prospectively (hypothetically) onto the child gives real meaning to their role-playing gestures in the present. Just as the bier is suddenly referred to as a pyre, Opheltes is also transformed by the mourners’ gestures and his tiny body seems to grow in stature (parvi augescunt funere manes). Even the funeral offerings contrast with the youth of Opheltes (muneraque in cineres annis graviora feruntur, 6.73). The irony or asymmetry of the excessive funeral for the dead Opheltes extends to the narrative itself: why devote so much attention to an infant’s cremation? Does the excessive treatment signal the narrative’s recognition of its inappropriateness? The reader must interpret the scene from these two juxtaposed narratives: the actual cremation of an infant which should arouse sympathy and the hyperbolic treatment of that cremation which could alienate another or the same reader.

Just as the reader’s attention is focused on Opheltes’ pyre and the piling of offerings, the narrative shifts to a second pyre located parte alia to expiate the killing of the serpent (6.84).53 The two pyres evoke the narrative shift in the description of the two pyres built for the mass cremations of Trojans and Latins in the Aeneid: diversa in parte (11.203), which turns the reader’s attention to the Latin pyre after the description of the Trojan pyre. In both epics, the reader’s focus is prioritized: the pyre of Opheltes is thematically more important than the expiatory pyre as is the Trojan pyre over their Latin opponents. Ironically, Statius further distinguishes the two pyres by describing how similar they are:

Iamque pari cumulo geminas, hanc tristibus umbris

ast illam superis, aequus labor auxerat aras,

cum signum luctus cornu grave mugit adunco

tibia, cui teneros suetum producere manes

lege Phrygum maesta. Pelopem monstrasse ferebant

exsequiale sacrum carmenque minoribus umbris

utile, quo geminis Niobe consumpta pharetris

squalida bissenas Sipylon deduxerat urnas.Already equal labor had built twin altars of similar

height, one to the gloomy shades, the other to the

gods above, when the lamentation from the curved

horn gave the sad signal, at which it was the custom

according to the mourning ritual of Phrygians to

carry out the young dead. They say that Pelops taught

this funeral rite and chant used for the youthful dead,

by which Niobe, consumed by the twin quivers,

in mourning brought out twelve urns to Sipylus. (6.118–25)

Thematically, the two pyres evoke those two pyres constructed for the mass cremations of Trojans and Latins in the Aeneid, but the description also serves an aitiological purpose: the music was originated by Pelops for the funeral at which Niobe cremated her twelve children. Niobe was punished for boasting about her fertility, but her punishment was also visited upon her innocent children and so, too, is the infant Opheltes punished for civic strife for which he is not responsible.

The two pyres compete for the reader’s attention: the pyres are identical and yet prioritized; one is for a specific person, the other for the slain serpent; one is dedicated to the shades below and the other to the gods above. Numerous digressions and references to the second pyre also divert the reader’s attention from Opheltes’ pyre. Statius now refers to the pyres as altars (6.119), but they are clearly constructed as pyres so their twofold purpose reveals another detail of their appearance and function. The reader must also refocus her narrative gaze and look left or right to imagine the second pyre and then down and up for the dedicatees of the pyres. Since Opheltes’ pyre is the thematic focus, the reader’s attention returns to it but only after the multisensory diversion occasioned by the second pyre. From an aural point of view: the funereal pipes and carmen add another sensory detail to the scene; however, Statius does not record the words of the carmen for his readers, and so his own narrative alludes to and also substitutes for the carmen.

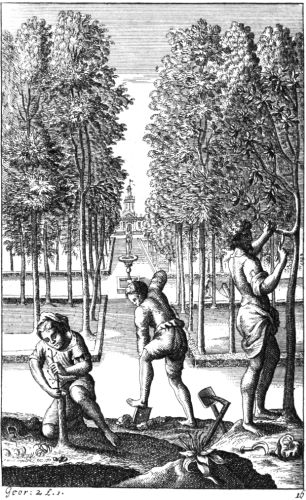

The narrative of the army’s cutting of trees for the second funeral pyre is excessive in its emphasis and intertextuality of the epic trope of tree felling for the construction of a pyre (6.90–117):

sternitur extemplo veteres incaedua ferro

silva comas, largae qua non opulentior umbrae

Argolicos inter saltusque educta Lycaeos

extulerat super astra caput: stat sacra senectae

numine, nec solos hominum transgressa veterno

fertur avos, Nymphas etiam mutasse superstes

Faunorumque greges. aderat miserabile luco

exscidium: fugere ferae, nidosque tepentes

absiliunt (metus urget) aves; cadit ardua fagus,

Chaoniumque nemus brumaque illaesa cupressus,

procumbunt piceae, flammis alimenta supremis,

ornique iliceaque trabes metuendaque suco

taxus et infandos belli potura cruores

fraxinus atque situ non expugnabile robur.

hinc audax abies et odoro vulnere pinus

scinditur, acclinant intonsa cacumina terrae

alnus amica fretis nec inhospita vitibus ulmus.

dat gemitum tellus: non sic eversa feruntur

Ismara cum fracto Boreas caput extulit antro,

non grassante Noto citius nocturna peregit

flamma nemus. linquunt flentes dilecta locorum,

ostia cana, Pales Silvanusque arbiter umbrae

semideumque pecus, migrantibus aggemit illis

silva, nec amplexae dimittunt robora Nymphae.

ut cum possessas avidis victoribus arces

dux raptare dedit, vix signa audita, nec urbem

invenias; ducunt sternuntque abiguntque feruntque

immodici, minor ille fragor quo bella gerebant.Immediately, a wood, never before deprived of its ancient branches,

is felled by an axe, none more opulent than which in the deep shade,

between the glades of Argos and Lycaeus, raised its top above the

stars. It stands hallowed by the sanctity of old age; not only is it said

to go back in years before the ancestors of men but also to have outlived

the succession of Nymphs and flocks of Fauns. In that wood came

pitiable

destruction: beasts flee, birds in their terror leap out of warm nests, the

lofty beech falls, the Chaonian groves and the cypress unharmed in

winter, pine trees lie on the ground, nourishment for cremation fires,

ash trees, timbers of ilex, the yew feared for its sap, mountain ashes soon

to drink the horrific blood of battle, and the oak invincible in its place.

Then the bold fir and the pine with its scented wound is cut; the alder,

friend

to the seas, bends untrimmed tops toward the ground, and the elm ever

welcoming to the vine. The Earth groans: not so are the Ismaran woods

carried away uprooted when Boreas freed from his cave raises his head,

no swifter does a nighttime blaze consume a forest when Notus

approaches.

Weeping, they leave their choice lairs, ancient homes, Pales and Silvanus,

ruler of the shade, and the semidivine flock and at their departure, the

wood

sobs and embracing Nymphs hold tight to their oaks. Just as when a

general

hands over to the greedy victors captured citadels to plunder, the signal is

barely heard, nor after would you find a city: greedily, they carry off,

overturn,

haul away, and plunder, the sound of battle waged was not as loud.

Statius goes beyond his epic intertexts of Homer, Ennius, and Vergil in the variety and sensory descriptions of the trees as he focuses on the effect of the destruction caused to the forest and its inhabitants by the removal of the trees. The woodland gods lament the destruction of the forest but not the death of Opheltes (aderat miserabile luco / exscidium) and their mourning for the lost trees competes with humans’ mourning for Opheltes. However beloved the trees to the woodland gods, the trees are cut and nature is marred; therefore, human grief is prioritized as more important than the preservation of such a hallowed and nurturing setting, thus calling attention to the incongruous mourning ritual for the dead child. The metaphor of the captured town further reminds readers that Opheltes is an infant and not a military hero and perhaps undeserving of such excessive grief.

The focus of the wood gathering, although connected with the death of Opheltes, is properly for the dead serpent, and the narrative is more elaborate than the description of the wood gathered for his pyre. Since the reader encounters the pyre of Opheltes first, there is a certain narrative tension over whether Statius will allude to the trope. This prioritizing of the narratives recalls Vergil’s use of his Homeric and Ennian intertexts of tree felling for the pyre of Misenus rather than that of Pallas. Once both pyres are constructed, however, the prioritizing of the tropes reveals that Statius’ allusions to Vergil are chiastic: he first alludes to the bier of Pallas, which occurs in Aeneid Book 12, after the description of Misenus’ pyre, in connection with the bier of Opheltes. He then proceeds to the construction of the serpent’s pyre, thus alluding to the construction of Misenus’ pyre which the reader encounters first in Aeneid Book 6. The complex relationship of the intertextuality of the descriptions begins to resemble the complexity of the intertextuality of the pyres themselves.

After the digression to the forest, the narrative returns to Opheltes’ bier as Greek leaders bring gifts and offerings for burning (6.126 ff). It is only after a second lengthy interval (longo post tempore, 6.128) that Opheltes’ body is carried on his bier (torus) to his pyre accompanied by his parents, but the text is vague as to the distance between the bier and the pyre. The reference to the transfer of Opheltes’ corpse occurs so briefly that his body gets lost in the crowd of mourners. Visualizing the scene, however, would restore Opheltes not among the crowd, but rather above it—on top of the many layers of his bier carried on the shoulders of young men with the canopy rising even higher.

The lamentation of Opheltes’ mother, Eurydice (6.135–85), alludes to speeches by Evander and Aeneas lamenting the death of Pallas.54 Statius also uses the trope of a parent lamenting the loss of a child to double as a call for revenge. Following Eurydice’s lament, the narrative focus returns to the pyre as her husband, Lycurgus, throws his scepter on it (6.193) and covers Opheltes’ face with his cut hair (6.194–96). Lycurgus then sets fire to the pyre by lighting the bottom timber first: iam face subiecta primis in frondibus ignis / exclamat; labor insanos arcere parentes / “already the torch is applied and the fire crackles among the lowest branches; it was hard to keep his stricken parents away,” 6.202–3. The emphasis is on lighting the lower flames first in order for the pyre to catch fire sufficiently. Denying access to the grieving parents who approach the burning pyre of their child adds a further touch of pathos to the scene as fire, which is a symbol of purification, also becomes a symbol of demarcation that separates the living from the dead.

Statius describes the cremation in-progress, but the description of the melting and burning sacrificial offerings substitutes for a description of Opheltes’ burning flesh (6.204–12):

Stant iussi Danaum atque obtentis eminus armis

prospectu visus interclusere nefasto.

ditantur flammae; non umquam opulentior illis

ante cinis: crepitant gemmae, atque immane liquescit

argentum, et pictis exsudat vestibus aurum;

nec non Assyriis pinguescunt robora sucis,

pallentique croco strident ardentia mella,

spumantesque mero paterae verguntur et atri

sanguinis et rapto gratissima cymbia lactis.The Danaans, ordered, stand and, with their armor

positioned, they block their view at some distance from the

horrific sight. The flames are enriched, never was there

a more lavish fire before turning to ashes: gems crackle, a huge

amount of silver melts, and gold oozes from the embroidered

cloaks; the timber is fattened with Assyrian fluids, and burning

honey hisses with the pale crocus, plates spewing wine are

overturned and cups of black blood and milk most pleasant

to the one taken away.

No mention is made of Opheltes’ burning corpse and Statius shields the reader from his cremation, as do his characters who use their armor to avert their gazes from the pyre. The description of the burning pyre is unique: although the timbers at the bottom of the pyre were set on fire first, the pyre burns from top to bottom and the order in which the offerings burn is prioritized as though the flames respect the narrative layering of the offerings. As the pyre burns each layer, the narrative order of the cremation reverses the earlier order of the piling as the most expensive objects on top of the pyre, which were placed last, burn first and the least expensive objects, which were placed first, burn last.

Although the reader does not see Opheltes’ corpse burn on the pyre, Statius uses an allusion to Seneca’s Thyestes to draw a grotesque parallel between the burning corpse of Opheltes and Atreus’ boiling of his nephew’s flesh:

haec veribus haerent viscera et lentis data

stillant caminis, illa flammatus latex

candente aeno iactat.

Impositas dapes

transiluit ignis inque trepidantes focos

bis ter regestus et pati iussus moram

invitus ardet. strident in veribus iecur;

nec facile dicam corpora an flammae magis

gemuere.55The innards are stuck on spits and drip above a slow

fire, boiling water in a heated pot tosses the other parts.

The fire leaps around the feast placed over it but is

thrown back onto the blazing hearth over and over again,

and ordered to endure it, unwillingly burns. Liver hisses

on the spits; not easily could I say whether the bodies

or the flames groaned more. (765–72)

Like Seneca, Statius’ narrative of the cremation emphasizes the melting, flowing, sputtering, and hissing of the offertory objects, in particular, his allusion to the detail of hissing spits of liver: strident in veribus iecur (770), by using the same verb to describe the burning of offerings (6.210). The personification of the burning offerings substitutes for a description of the burning Opheltes, but it also dehumanizes the boy who burns among disturbing literary intertexts. The intertextual reference to Atreus is furthermore unsettling when one recalls that Opheltes is an infant who died an untimely death is compared to Thyestes’ sons (three in Seneca’s play) and unexpected considering the multiple references/allusions to Vergil’s Aeneid and the death of Pallas.

The ceremony moves from the center of the pyre to its perimeter: Lycurgus leads seven squadrons around the pyre with their shields reversed, with their circular motion from the left hand side being emphasized (6.214 ff).56 They circle the pyre seven times as the clashing of weapons alternates with the wailing of women. Statius then redirects the focus away from Opheltes’ pyre to another pyre on which animals are offered, although it is not clear whether he is referring to a fire next to Opheltes’ pyre or the serpent’s pyre, which is burning contemporaneously, before returning to the final offerings made to Opheltes: semianimas alter pecudes spirantiaque ignis / accipit armenta (6.220–21). The prophet orders the mourners to change directions, and they now encircle the pyre from the right hand side (6.221ff) as they throw armor onto the flames. Opheltes’ pyre burns completely and is watered down (6.234–37):

Finis erat, lassusque putres iam Mulciber ibat

in cineres; instant flammis multoque soporant

imbre rogum, posito donec cum sole labores

exhausti; seris vix cessit cura tenebris.This was the end and tired Mulciber was already

consumed among the decaying ashes; they approached

the flames and soaked the pyre with much water,

until their labor ended with the setting of the sun;

scarcely did their care yield to the late shadows.

The text announces that this was the end of the cremation, but the narrative omits details of the gathering of Opheltes’ cremated remains which could have provided further intertextuality with texts, such as Seneca’s Phaedra, that include a performative description of the ritual ossilegium. Hypsipyle’s earlier gathering of Opheltes’ mangled flesh (605–6), rather, anticipates and serves as a substitution for the actual gathering of his cremated remains.

After nine days have passed, the cremation site has undergone a change and the focus is now a marble temple built over the pyre to house Opheltes’ ashes (6.242–48):

stat saxea moles,

templum ingens cineri, rerumque effictus in illa

ordo docet casus: fessis hic flumina monstrat

Hypsipyle Danais, hic reptat flebilis infans,

hic iacet, extremum tumuli circum asperat orbem

squameus: exspectes morientis ab ore cruenta

sibila, marmorea sic volvitur anguis in hasta.A marble heap stands,

a huge temple to his ashes, with a sculpted frieze that

tells of his misfortunes: here Hypsipyle points out the

river to the tired Danai, here crawls the weeping baby,

here he lies, the scaly serpent ravages the furthest area of the

mound: you would expect hissing from the bloody mouth

of the dying serpent, thus does it coil around the marble spear.

The temple contains a frieze with a narrative cycle that describes the two causes of Opheltes’ death: Hypsipyle and the serpent. Select scenes are depicted on the temple (unless the narrative only focuses on select scenes): the unattended Opheltes (killed while Hypsipyle was recounting the details of Lemnian slaughter and her sham cremation of her father), the dead child, the retreating serpent, and his death in progress. The actual death of Opheltes is not shown. hic iacet (6.246) gives an epitaph to the dead Opheltes which is not otherwise explicitly described as part of the temple or frieze detail.

The narrative frieze changes appearance as it recounts details surrounding the deaths of Opheltes and the serpent and reflects the shifting appearance of the site into a temple which represents a second metamorphosis of the site as it changes from pyre to altar and then to a temple following Opheltes’ cremation. The changing appearance and function of the site are appropriate since they reflect the various metamorphoses of Opheltes: a dead infant who is cremated as an adult warrior reduced to ashes and commemorated with a temple. The funeral games that follow the cremation are also transformative as the landscape provides a theatrical backdrop to the games in much the same way that nature provided a theater for the deaths of Astyanax and Polyxena in Seneca’s Troades.

Thus, Statius’ approach to intertexts in Book 6 is complex as he at once alludes to or sets up an expectation of an allusion to the epics of Vergil, Ovid, and Lucan and other intertexts such as Seneca’s Phaedra and Thyestes. He also diverges from them to create an original description of Opheltes’ cremation. The result is a text in which the infant Opheltes is transformed and overshadowed by the narrative of his own cremation and the competing and reduplicating narrative of the symbolic cremation dedicated to the serpent. The reader loses sight of Opheltes almost as soon as his body is laid on top of his unique and intertextual bier. The narrative further distances the reader from Opheltes’ corpse and cremation by questioning its own epic treatment of the cremation and thus leaving the reader an univited guest at a funeral that assaults the reader’s sense of propriety and familiarity with the trope of epic funerals.

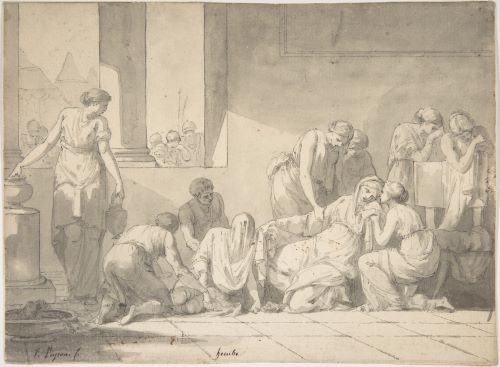

Corpses in Search of a Cremation

The first half of Book 12 (lines 1–463) revolves around the cremation and burial of Theban dead from which the devotion of Argia, daughter of Inachus, and of Antigone to cremating Polynices becomes a central issue, especially, in light of Creon’s ban against cremating the Argive dead.57 The women are affected by the war, but they can only enter the battlefield following the battle to look for the corpse of Polynices. They find his corpse by different routes, and out of varying motivations give his corpse a cremation but inadvertently on the same pyre that is consuming Eteocles’ corpse. Their piety contrasts with the actions of Hypsipyle in Book 5, in particular, her sham cremation for her father, but their rivalry following the discovery of their cremation of Polynices echoes the brothers’ enmity toward each other.58 The episode is a turning point as Theseus kills Creon in the book’s second half; but like the rivalry between Argia and Antigone, the killing of Creon is the just the latest perpetuation of more rivalry and bloodshed. After a series of endings, Statius claims in a sphragis that he is unable to describe the countless funerals that followed and wishes an immortal fame for his poem that will respect the primacy of the Aeneid. Statius, however, continues to allude to both death ritual and Vergil, thus negating his claim that he is not capable of further intertextuality.

Burial of the dead is both a moral and narrative imperative as the epic continues to use allusions to death ritual and epic intertexts to inform and challenge the narrative and the reader.59 Statius goes beyond his Vergilian intertext in a number of ways: by imitating the narrative excesses and grotesque and absurd elements from Ovid and Lucan to describe the roles played by Argia and Antigone to bury Polynices, the description of the joint cremation of Polynices and Eteocles, and by alluding to the ending of the Aeneid at line 781 but then extending his own narrative and his intertextuality with the Aeneid further. The various endings of the Thebaid, both before line 781 and the narrative beyond, are informed by death ritual: as a comment/appendix to the death of Turnus in the Aeneid; intertextuality, however abbreviated, with the epic trope of funerals and cremations negates the conceit of Statius’ sphragis that he is not up to the challenge of describing funerals or engaging previous texts. The sphragis itself connects both poet and poem to Vergil as poet and funereal symbol, thus further extending intertextuality with Vergil and literary allusions to death ritual. Statius, therefore, goes beyond his Vergilian intertext; but his professed inability to engage further the epic trope of funerals and cremation points to a narrative in which the trope, reduced to brief allusions and finally abandoned by the poet, is actually in search of a narrative.