Sweeping lives, memories, and necessities.

By Ruth Talbot

News App Developer

ProPublica

By Nicole Santa Cruz

Reporter

ProPublica

By Maya Miller

Engagement Reporter

ProPublica

Introduction

As homelessness has surged to record levels in the U.S., cities are increasingly removing or “sweeping” tents or entire encampments of people living outdoors.

Cities say they carry out these clearings humanely with the goal of getting people off the street. But they often result in people’s belongings being thrown away. ProPublica found — through reviewing records from 16 cities, reporting in 11 cities and speaking with people across the country — that these actions create a cycle of hardship.

Elijah Harris, 38, was living in a tent near Hollywood in January when Los Angeles sanitation workers showed up late one morning. Harris said he left to warn others nearby that the city was clearing the area. He came back to find his tent and its contents gone. He lost everything he needed for his job with DoorDash: his electric bike, ID and iPhone.

Losing his phone meant he had to regain access to his DoorDash account. Without his passport and Social Security card, which he said were also taken, that process proved difficult.

“They ask you to take a picture of the front and back of your ID and then take a selfie to verify it’s you, but I couldn’t do that,” Harris said. “It was a disaster.”

He said he couldn’t do his delivery job for months and then had to ride a nonelectric bike, which limited the area he could deliver to and the amount he earned.

Los Angeles officials did not comment on Harris’ case but said in a statement that the city “works to not unnecessarily remove anyone’s belongings” and that unattended items are stored or thrown away.

“I was trying to get off the streets, but they set me back. It’s not easy getting services, and trying to find work, and trying to save.” – Harris, who lives in Los Angeles, said the loss of items he needed to work was a “disaster.”

Harris is one of thousands of people living on the streets in the United States who have been subject to sweeps, the term often used to describe how cities dismantle homeless encampments or clear areas where people are living outside.

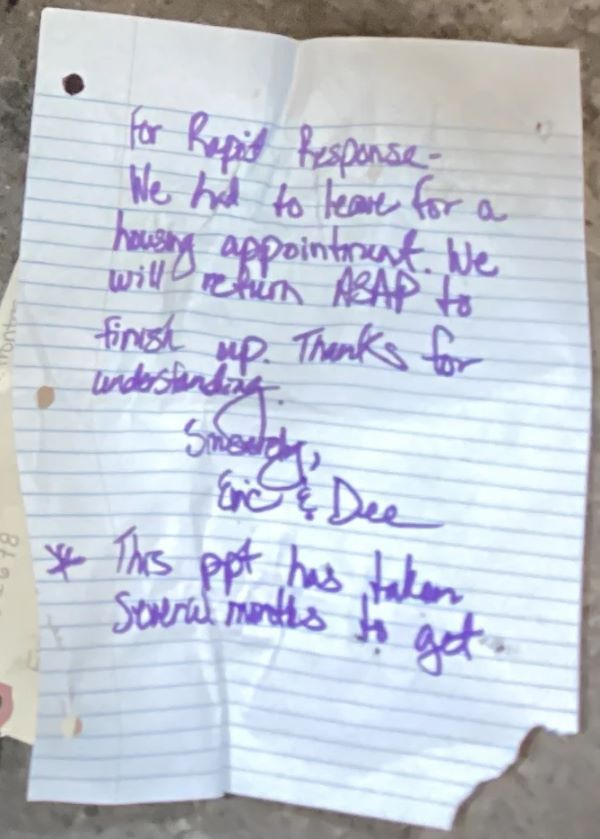

Cities, including Los Angeles, have policies to alert people before a sweep. In an ideal scenario, city officials said, people would be packed before crews arrive. But advance notice is not always required. Many people told ProPublica they didn’t know workers were coming or had stepped away for work, appointments or to find water when workers came. Some were in the process of moving their items but couldn’t do so quickly enough. Workers sorted through what’s left, sometimes storing items and throwing others into garbage bags or trucks.

Encampment removals have become more common as local governments try to reduce the number of people living on sidewalks and in other public spaces. They are likely to escalate further after a U.S. Supreme Court decision in June allowed municipalities to arrest or cite people for sleeping on public property even if there’s no available shelter.

Municipalities are often under pressure from business owners and residents to remove encampments, which officials said can obstruct sidewalks and pose public health, safety or environmental hazards.

Many cities told ProPublica that letting people live outside is not compassionate. “We cannot allow unsheltered residents to live in conditions that are below what we would accept for ourselves,” a Minneapolis spokesperson said in a statement to ProPublica.

Some cities, including San Francisco, characterized encampment removals as a first step toward shelter and housing.

“We are going to make them so uncomfortable on the streets of San Francisco that they have to take our offer” of shelter or housing, San Francisco Mayor London Breed said in July after announcing more aggressive sweeps would take place.

Advocates and people living on the streets say encampment clearings perpetuate homelessness.

“Every time someone gets swept, it just sets us back like 10 steps,” said Duke Reiss, a peer support specialist at Blanchet House in Portland, which provides meals and services to those experiencing homelessness. “It makes it almost impossible to get people help because everything requires documentation.”

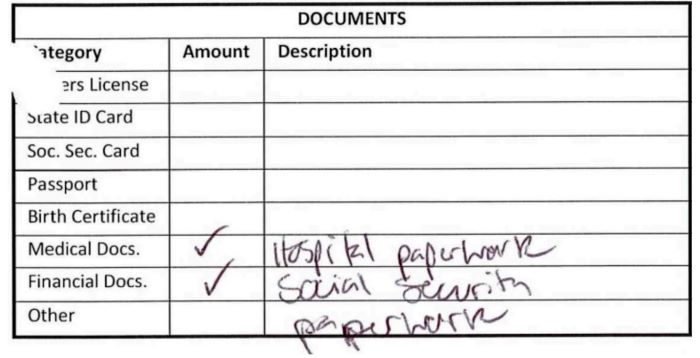

While many cities instruct workers to store identification, service providers told ProPublica about people they were working with who struggled to access Medicaid, disability benefits, food stamps, sobriety programs and housing after their documents were confiscated in encampment removals.

Courts have ruled that the destruction of property during sweeps violates the Fourth and 14th amendments, which prohibit unreasonable seizures and guarantee due process and equal protection under the law.

Some U.S. cities have established programs to store belongings — sometimes in response to those lawsuits. But they still have broad discretion over what ends up in the trash. ProPublica found that even when objects taken from encampments are stored, people are rarely reunited with their belongings.

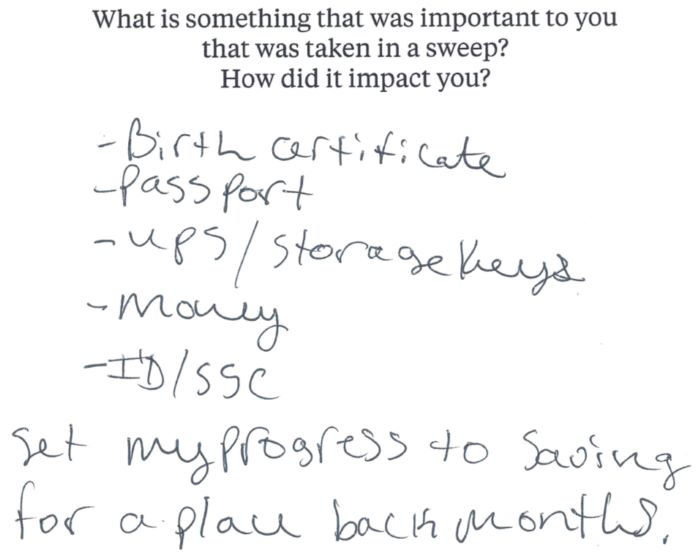

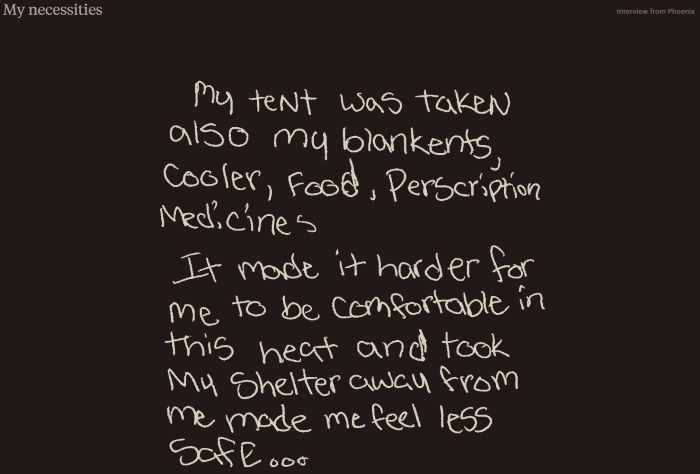

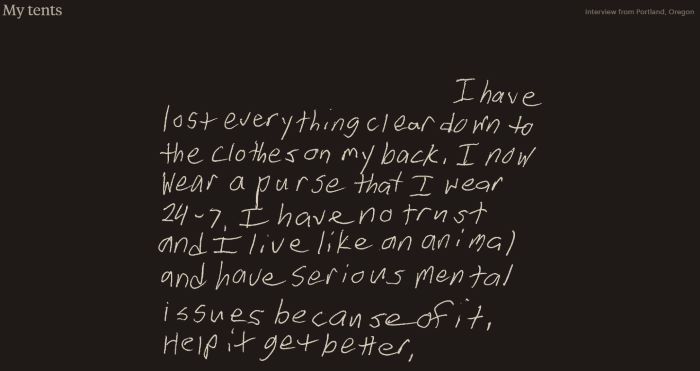

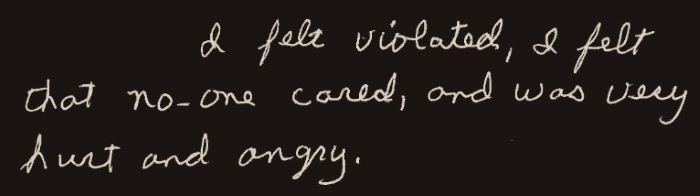

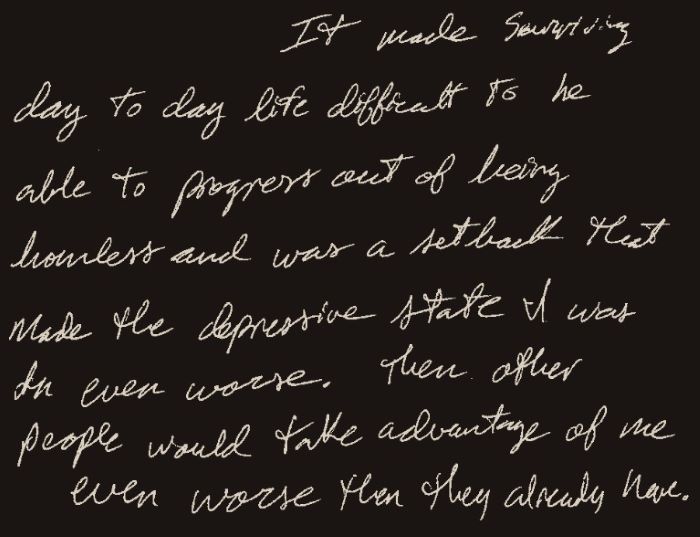

To understand what governments confiscate and how it impacts people living on the street, we received storage records from 14 cities with large homeless populations and reported on the ground in 11 cities. We spoke to 135 people who had experienced sweeps, and we gave many notecards to write about the consequences in their own words.

Over and over, they told ProPublica that having possessions taken traumatizes them, exacerbates health issues and undermines efforts to find housing and get or keep a job. More than 200 additional people who went through sweeps, outreach workers and others who have worked with unhoused people wrote to us echoing these sentiments.

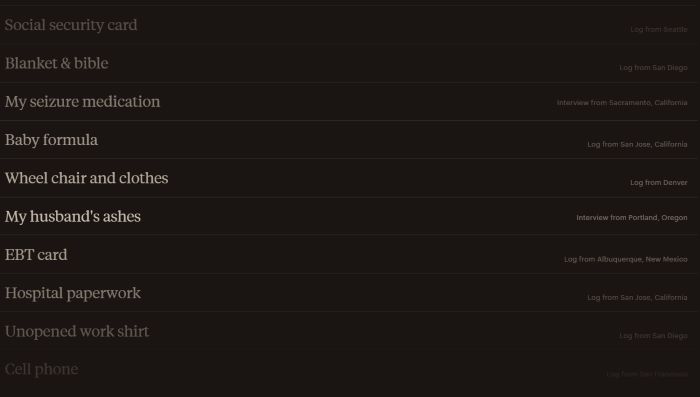

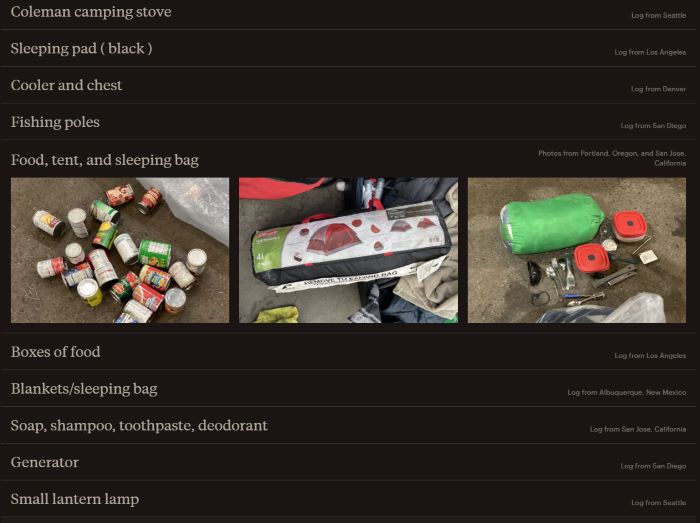

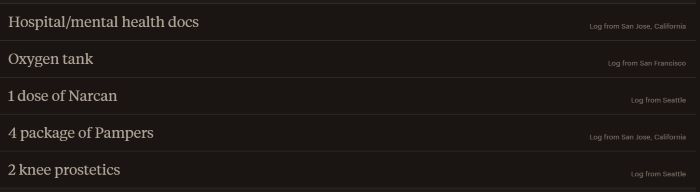

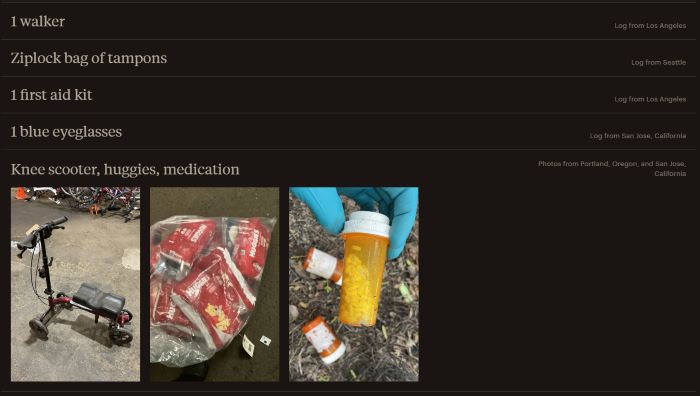

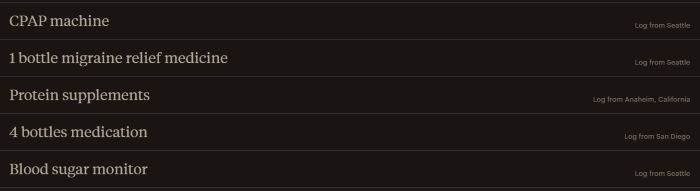

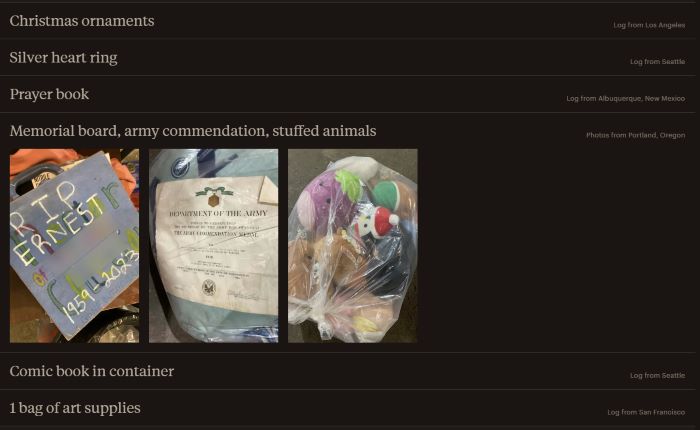

The storage records included images and written descriptions of the items cities had collected. Some records described the brand or color of belongings. Others had little detail, referring to most belongings as a “personal item” or providing no description at all.

Here are just some of the items that were taken.

Survival Gear

In the three years Steven lived outside around Little Rock, Arkansas, he said he got frostbite leading to the amputation of his feet.

“I would almost say it’s borderline harassment, but there’s nothing borderline about it.” – Steven got frostbite after two encampment removals where his belongings were taken.

City workers cleared his camp in February after a snowstorm. Steven, 39, who uses a wheelchair, remembers asking for more time to pack. He said he was told no and was only able to gather a pillow, a backpack with some clothing and a Bible. Workers bulldozed everything else, including the tent and bedding that kept him warm.

City workers came to his new camp and took everything else. He got frostbite again.

ProPublica saw more than 400 references to tents and over 400 references to sleeping bags or blankets in the logs.

Rebecca Huggins, 33, broke her foot this year and needed surgery. While she was recovering, she slept in a dry riverbed in a Phoenix park. City workers confiscated her tent, umbrella, ice chest, sunscreen and pain medication as temperatures rose to 100 degrees, Huggins said.

“It was really hard for me,” she said. “They took everything, my sunscreen, everything, like all my necessities to be almost comfortable.”

Violette Loftis, a 42-year-old in Portland, said she’s lost tents to sweeps and theft.

“I’ve had many tents, and I never had one for more than like a week, if that,” Loftis said. “I’ve started over so many times it’s like nothing now, but like the first few times I was just like lost.”

To avoid sweeps, Loftis now sleeps in doorways without a tent.

Sometimes the belongings that were taken included supplies purchased using government funding. Portland officials say they regularly dispose of tents; the county has handed out thousands of tents in recent years. In San Francisco, an organizer told us the Department of Public Health hands out hygiene kits that are confiscated in encampment removals. Outreach workers said it can be challenging to get people government-subsidized service again when their phones are taken.

“We’re actually getting money from the city or the county to purchase these things for individuals, and then they’re just turning around and throwing them all away the next day,” John Rios, a case manager for people experiencing homelessness in Seattle, told ProPublica.

A Seattle spokesperson said tents and other gear are stored unless they are wet or hazardous.

Work Items

People experiencing homelessness told us that the confiscation of belongings – such as tools, phones, and modes of transportation – limited their ability to work.

In Los Angeles, Mario Van Rossen said he lost tools he used to do gardening, landscaping, and handyman jobs this year. He had moved his belongings to a nearby street that he thought was outside the sweep zone, but city workers still took the tools while he watched.

“You guys stripped me of my living. I use those tools to make money to hopefully get off the streets.” – Mario Van Rossen, 49, said he lost tools he needs to do gardening and other jobs.

He said he lost more items in another sweep after speaking to ProPublica in June.

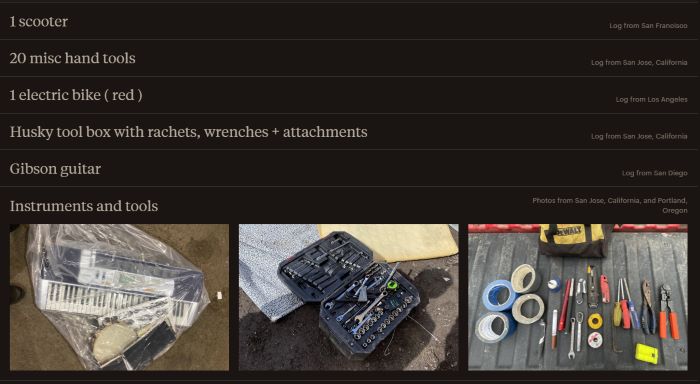

ProPublica saw over 150 references to tools and toolboxes.

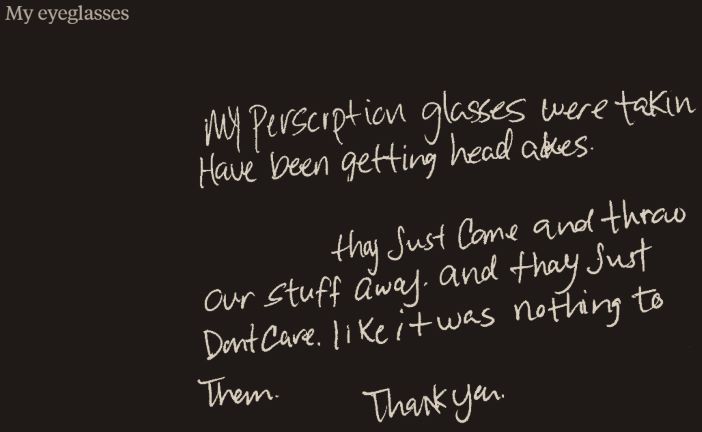

My work clothes and ID: In early June, as temperatures creeped above 100 in Las Vegas, Dorothy said she ran to grab water. When she returned, her wagon — stuffed with her work clothes, blankets, four tents and eyeglasses — was gone.

Dorothy, a security guard, said it would take months to replace what she needed for work.

“They threw away me and my son’s badges,” she said. “So therefore, we can’t go to work.”

My instruments: Ronald Brown, 61, was working as a street musician in Portland when he said his tent and the guitars inside were taken.

City contractors left cards with their number, but when he called, they said they didn’t have the instruments. Brown said he has no idea if they lost or stole them or if someone else took them in the chaos of the sweep.

Portland officials said they didn’t see instruments in the photos crews took of a sweep in the area.

Medical Supplies

Outreach workers and people who’ve experienced removals told us of the loss of CPAP machines; antibiotics; Narcan to reverse drug overdoses; medications for blood pressure, diabetes, and seizures; wound care items; mood stabilizers; nebulizers; inhalers, insulin; and prenatal items.

When medications or medical devices are taken, health conditions can worsen and visits to emergency medical services can increase. Replacing medication and devices can also be expensive.

Barbara DiPietro, senior director of policy at the National Health Care for the Homeless Council, a nonprofit research and advocacy group, said when medications are taken from people it’s “significantly destabilizing.”

“What would happen if you just suddenly went off all of your medications?” she said. “How would that throw your entire body off, but then also your ability to work, your ability to take care of your daily functions?”

ProPublica saw over 80 references to wheelchairs or walkers.

In the fall of 2023, Greg Adams was sleeping near the Sacramento River when a crew arrived. He said he lost his hiking backpack because he couldn’t carry it up an embankment. Inside the backpack, Adams kept Keppra, a seizure medication. It took months to replace, and in that time he said he experienced a seizure, causing him to fall and injure his head.

Sacramento officials said that multiple agencies have jurisdiction over the area.

My Hepatitis C medication: Helen’s Hepatitis C medication has been taken multiple times in Portland. For it to be effective, Helen had to finish all of the medication, which can cost tens of thousands of dollars.

“I was flipping out,” she said. “That stuff’s not cheap.”

Helen had to work with a clinic to get a replacement approved. To keep it safe, she stored it at a local nonprofit.

Portland officials say they tell workers to always store prescribed medication.

Adam Mora said he had eyeglasses taken in a sweep in Riverside, California, this year.

His partner said her supply of contacts was also taken.

Riverside officials did not comment on specific cases but said they do their work with the “utmost professionalism and respect.”

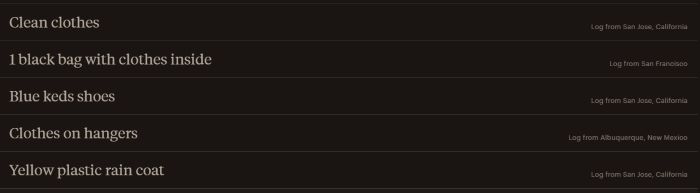

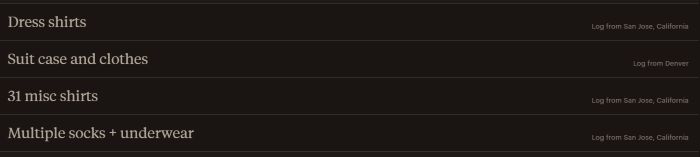

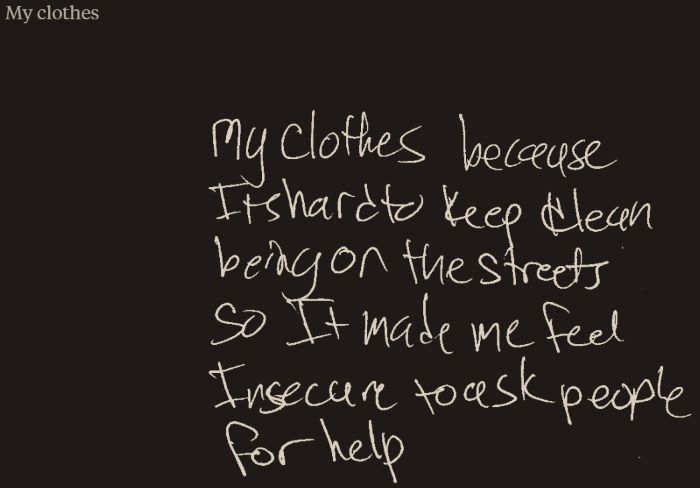

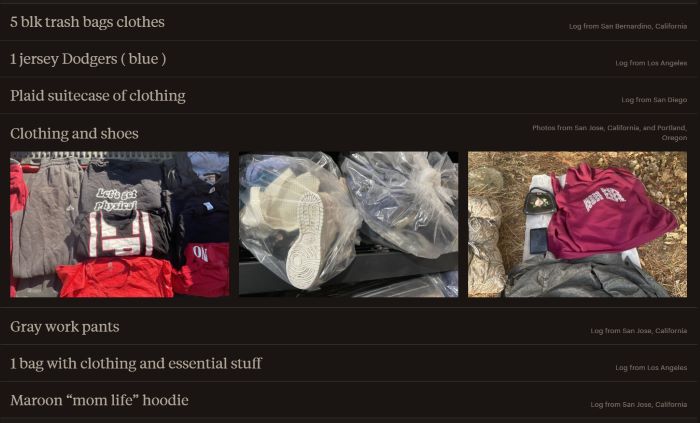

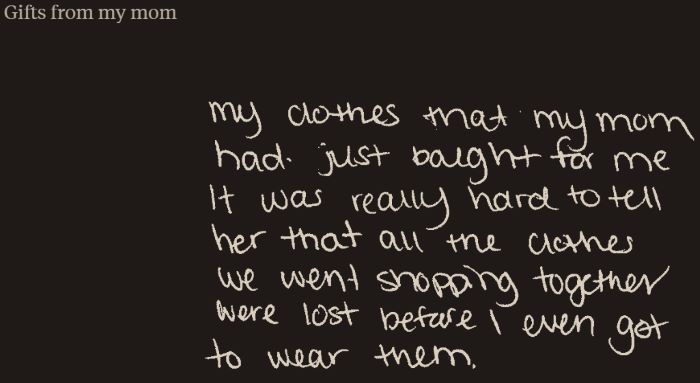

Clothing

People told ProPublica that an entry in the logs as mundate as clothes could represent the loss of a memento from a loved one or the ability to stay clean and safe.

ProPublica saw over 1,300 references to clothes, clothing or shoes.

My boyfriend’s shirt: Candince Swarm’s boyfriend, Armando, died in July 2021. Swarm, who is 38 and lives in Austin, Texas, kept the shirt he was wearing that day in a Ziploc bag. She described taking it out once: “It still smelled like him, you know, and I just missed him so much in that moment and I just hugged the shirt and I cried.”

In November 2023, city workers told her she had 72 hours to move her belongings. She said workers returned about 48 hours later and crushed her van and everything inside, including Armando’s shirt.

Jeffery Stafford, in Riverside, said he watched a city crew dispose of his tent, shoes and clothes. “They came in with the Bobcat and just picked up whatever they could, threw it in the truck and took it,” the 32-year-old said. Afterward, he said, he “started wandering the streets,” trying to replace his survival gear.

Kayla said she lost all of her clothes when workers removed her encampment in San Francisco in 2020. Kayla’s mother had taken her shopping recently.

“I came back and everything was gone,” she said.

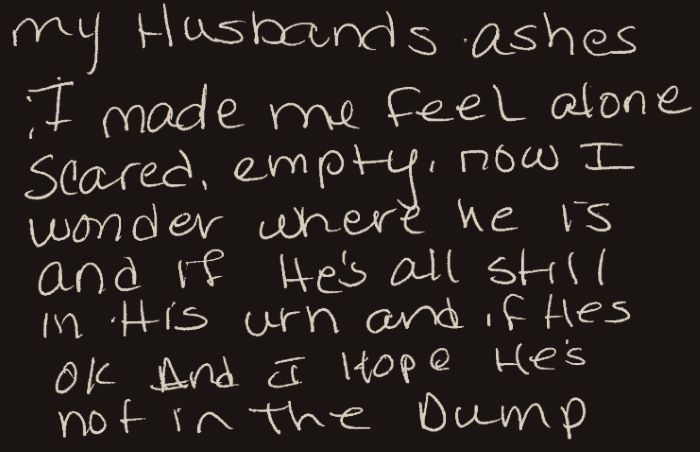

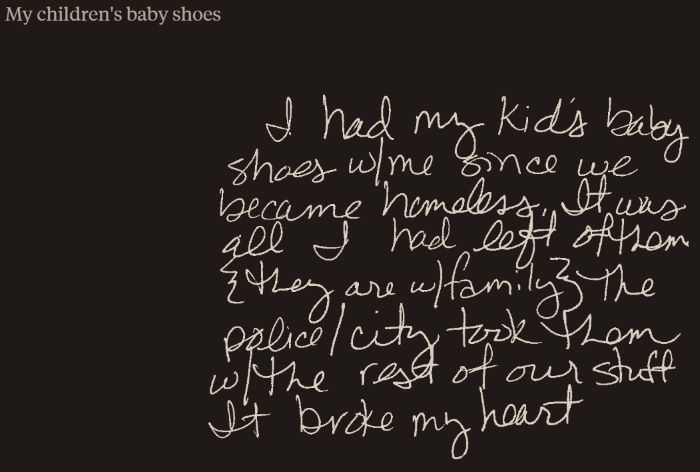

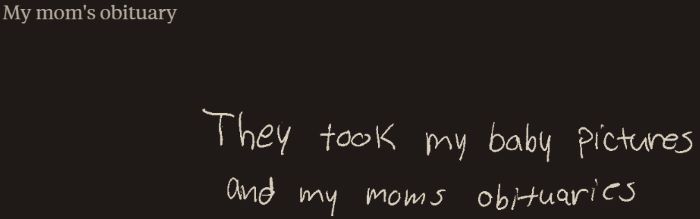

Sentimental Items

Since Teresa Stratton, 61, became homeless with her daughter over a year ago, she’d kept her husband’s ashes in an urn made of Himalayan sea salt. Ray, the “love of hef life,” died in 2020.

“You could see it in his eyes every time he looked at me, how much he loved me.” – Teresa Stratton said her husband’s ashes were taken in a sweep in Portland.

In April, when city contractors came through Delta Park in North Portland, she said Ray’s ashes were taken.

Portland officials said they didn’t see an urn in photos taken by workers. They said depending on how the ashes were stored, they could have been thrown away.

Advocates and people experiencing homelessness repeatedly mentioned having ashes taken during sweeps.

Many cities only store items that cleanup crews deem valuable and in good condition, meaning things like letters and photos can be discarded. In interview after interview, people said the loss of these belongings stuck with them the most.

ProPublica saw over 125 references to belongings described as “personal.”

Over six years, Mary and Jeff Yahner said crews in the Phoenix area took their belongings at least a dozen times. They’ve lost and replaced documentation and clothing. But Mary, 59, gets emotional when she thinks about the loss of blue baby shoes that her son and daughter wore.

Photos of my mother and sister: Harold Odom, 64, has been housed for about seven years. But he still thinks about the family photos, including of his late mother and sister, that he said were taken from him in a sweep in Seattle.

“It’s a sense of loss that doesn’t go away,” he said. “Knowing that my belongings are likely gone for good — trashed or lost forever — fills me with a sadness that’s hard to bear.”

Brandon Lyons, 28, had his belongings taken by Riverside’s code enforcement unit last year. Lyons said he and his friends moved their belongings out of the area, but the city still took them when they were briefly left unattended.

My crown: Crystal was most devastated to lose a rhinestone crown during a Portland sweep.

“It was just the feeling when I wore it,” she said. “Like I was somebody.”

There were sweeps in the area around this time, but city officials said they didn’t find a record of her items.

Repeated Loss

ProPublica spoke to many people who lost nearly everything they owned repeatedly. They told us how this extreme loss disoriented and demoralized them.

After two sweeps in the span of a few months, Jerry Vermillion, 60, said he stopped trying to rebuild and spent most of the past two years in Portland “wandering around sleeping in a doorway here, a doorway there, not settled.”

“You better get used to starting over. If you get attached to anything, you’ll get devastated,” he told ProPublica.

Vermillion is in temporary housing now, as he secured one of 20 spots offered by a local nonprofit. But he said the sweeps did not motivate him to find housing.

Even when someone gets off the streets, the loss of what was taken stays with them. Deonna Everett, 68, said the city of Santa Cruz, California, threw away many of her belongings, including furniture she’d saved from when she was housed in early 2024. When she moved into new housing in June, she had only clothes and a few other items.

“I don’t know if anything will ever seem quite right after what happened,” Everett said. “But I have to keep in mind that there’s got to be a light at the end of this tunnel. And so I’m just going to keep a close eye on that light. I hope it’ll shine.”

One person, who asked not to be named because of safety concerns, offered a description for people on the streets: “I call us the missing-stuff folks,” she said. “We’re missing our families, we’re missing our homes, we’re missing our stuff.”

Reporting the Story

ProPublica received records of personal property collected during homeless encampment removals in 14 cities. Out of thousands of items in those responses, ProPublica chose a small selection to display here, prioritizing notable entries and items representative of those commonly seen.

Some records clearly indicated whether an item had been disposed of by the city. Other records did not explicitly list a status for items. When possible, via reaching out to cities or cross-checking against property retrieval logs, ProPublica confirmed that the items displayed were disposed of. When we could not confirm whether an item was disposed of, ProPublica only used items that were not listed as claimed.

We verified that sweeps occurred in the geographic area and around the time that our sources described using additional interviews, city data, sweeps schedules or media reports. We also gave cities the opportunity to respond to what would be included in this story, and we noted throughout when they provided relevant context or disagreed with specific details. We verified each person’s identity through public records. In one case, due to a common name and difficulty reconnecting with the source, we confirmed the name matched what was given to service providers. We used only first names when people said the publication of their full names would pose safety risks.

Originally published by ProPublica, 10.29.2024, under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 United States license.